1. Introduction

Heart rate is a fundamental physiological parameter that reflects the autonomic regulation of the cardiovascular system and serves as a crucial indicator of an organism’s health and metabolic state. In aquatic biology, especially in developmental and environmental physiology, monitoring the heart rate of fish—particularly at early life stages—has emerged as a valuable non-invasive approach to assess stress responses, detect environmental perturbations, and investigate ontogenetic changes [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Transparent fish species, such as Danionella, offer an exceptional opportunity for such research due to their optical transparency, which allows direct visualization of internal organs, including the beating heart, without the need for surgical intervention or complex imaging techniques [

5,

6,

7,

8].

In recent years, the ability to continuously and accurately monitor heart rate in larval fish has become increasingly important for several reasons. First, the larval stage is a critical period in the life cycle of fish, during which rapid morphological and physiological changes occur. Subtle shifts in environmental conditions—such as temperature, pH, or exposure to pollutants—can significantly affect cardiac performance during this stage, potentially leading to developmental abnormalities or increased mortality [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. As such, heart rate measurements serve as an early and sensitive biomarker for detecting physiological stress and sublethal toxicological effects [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Second, in the context of comparative physiology and developmental biology, heart rate data provide key insights into the evolution and function of the vertebrate cardiovascular system. Transparent fish models, like Danionella or zebrafish, are widely used in genetics, neurobiology, and pharmacological research. These species allow researchers to correlate physiological readouts such as heart rate with molecular or genetic manipulations, enhancing our understanding of gene function and cardiac regulation. Furthermore, developmental studies often require high-throughput screening methods, and heart rate monitoring is an effective metric for evaluating the impact of genetic mutations, drugs, or environmental exposures.

Traditionally, heart rate in larval fish is monitored using video imaging methods. These techniques involve recording high-frame-rate video of the fish and analyzing changes in pixel intensity within the heart region to detect rhythmic movements associated with cardiac contractions. While this approach is non-invasive and provides accurate results, it typically requires manual pre-processing steps, including the selection and definition of the heart region (the arena of interest) in each video. This manual annotation is time-consuming, subjective, and limits scalability, especially in high-throughput experiments. Moreover, many of the existing software solutions for video-based heart rate analysis are commercially available and expensive. Their high cost and complexity can be barriers for small laboratories or educational institutions, and their lack of adaptability may hinder their application across different species or experimental settings.

To overcome these limitations, this study introduces a novel heart rate monitoring system based on the analysis of interframe luminance differences. By measuring frame-to-frame changes in brightness within video sequences of Danionella larvae, our system detects the rhythmic movements of the beating heart without the need for manual selection of the region of interest. This approach enables fully automated, low-cost, and accessible heart rate monitoring suitable for a wide range of applications in developmental biology, ecophysiology, and toxicology research.

The aim of this study is to develop and evaluate the feasibility and accuracy of this interframe luminance difference-based method for heart rate monitoring in fish larvae. We test our system using transparent Danionella larvae and compare the heart rate measurements obtained through our method with values reported in previous studies. By validating our system, we demonstrate its potential as a reliable and efficient tool for non-invasive physiological monitoring in aquatic research. The ability to monitor heart rate accurately and continuously at early developmental stages holds significant implications for understanding larval development, environmental adaptation, and stress physiology in fish.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish and Ethical Considerations

Danionella translucida (National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Osaka, Japan) were raised and maintained as previously described (PMID: 30323353) at the Mie University Zebrafish Research Center. Although this study was purely observational and did not involve any toxicological procedures, it was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for zebrafish toxicological studies established by Mie University. In addition, since fish are explicitly included among the target species in Japan’s national guidelines for animal experimentation, the present study was carried out within the scope of the National Institute for Environmental Studies guidelines.

2.2. Video Acquisition

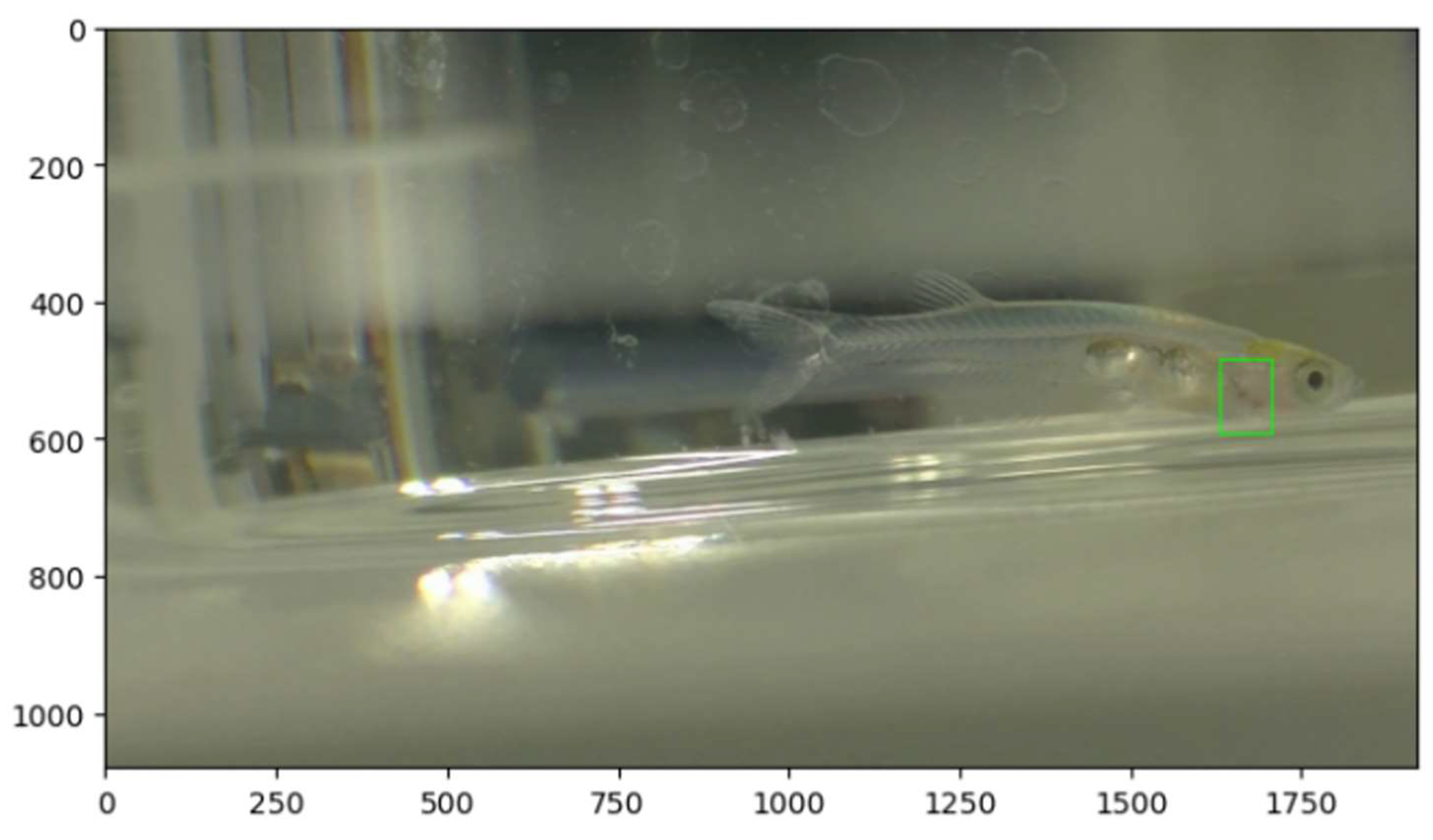

To monitor heart rate activity, individual Danionella larvae were placed in a beaker filled with aquarium water. A waterproof, dustproof, shockproof, and cold-resistant digital video camera (Everio R, JVC, Japan) was positioned beside the beaker (as shown in

Figure 1) to record the larvae through the glass wall of the beaker. The camera captured footage at a resolution of 1920×1080 pixels using an interlaced scan (60i) with a variable bit rate (VBR) averaging approximately 24 Mbps. The device supports continuous recording for approximately 4 hours and 40 minutes and measures 60×59.5×128 mm (

Figure 1).

Due to the optical transparency of Danionella larvae, internal organs including the heart are clearly visible. The heart appears reddish under standard lighting conditions owing to circulating blood, which facilitates visual identification and motion-based heartbeat detection. Figure (a) shows the state of a Danionella being filmed with a video camera. Depending on the time of day, there is little movement, so the heart rate can be measured visually using a multi-counter. Photo (b) shows a Danionella filmed in video mode. Due to the extreme optical transparency of Danionella larvae, not only the heart but also skeletal structures such as the vertebral column are clearly visible without dissection or staining. This characteristic facilitates non-invasive observation of physiological and anatomical features.

2.3. ROI Selection and Heart Rate Detection

Heart rate estimation was performed by analyzing motion within the heart region of the larvae using a frame-difference-based algorithm. Each recorded video was processed frame-by-frame to extract a fixed Region of Interest (ROI) around the visible cardiac area, where blood flow could be observed. The ROI was defined based on the stationary positioning of the larvae during filming, and care was taken to ensure consistent placement across frames.

The ROI from each frame was converted to grayscale, and its luminance change was calculated by subtracting the corresponding grayscale values from the preceding frame. To emphasize blood movement, a thresholding process was applied to the resulting difference image: pixels with a luminance change above a predefined threshold were assigned a value of 255 (white), and those below were set to 0 (black), resulting in a binary image. The sum of white pixels was then calculated for each frame, representing the extent of motion in the cardiac region.

When the white pixel count exceeded a certain threshold, it was interpreted as one cardiac contraction. This process was repeated for each frame over the entire video sequence. For final heart rate estimation, the number of beats detected within each 10-second segment was multiplied by six to yield beats per minute (bpm).

Let

It(

x,

y) be the grayscale intensity of the pixel at location (

x,

y) in the Region of Interest (ROI) at frame t. The frame difference image

Dt(

x,

y) is computed as (1)-(6),

A binary motion mask

Mt(

x,

y) is then computed by applying a threshold

θ to

Dt(x,y)

The motion magnitude

St for flame

t, representing the total number of pixels above the threshold, is then:

Let

Ts be the threshold for detecting a heartbeat (i.e., a sudden increase in

St). Then a heartbeat is detected at frame

t if:

The total number of beats

B in a time window of

N flame is:

If the video frame rate is

f, frames per second (fps), and

T is the total duration in seconds (i.e.,

N=

f⋅

T), then the heart rate in beats per minute (bpm) is:

For example, if f is 30 fps, T is 10 seconds, and B is 12 beats detected, the result will be 72 bpm.

To evaluate heart rate estimation in Danionella translucida larvae, we utilized video recordings (resolution: 640×480, MP4 format) where blood flow in the cardiac region was clearly visible. A fixed Region of Interest (ROI) was defined manually around the heart area, ensuring it included the main visible vessel and pulsatile blood flow. The ROI size was set to 500×500 pixels, adjusted based on the size of the fish, and positioned using fixed screen coordinates to maintain consistency throughout the video.

The larvae remained stationary during the recordings, providing stable conditions for motion detection. The frame rate of the video was 30 frames per second (fps), allowing sufficient temporal resolution to capture cardiac activity.

A custom frame-differencing algorithm was implemented using Python (v3.12.7) in the Spyder IDE (v5.5.1) on the Anaconda open data science platform. The algorithm processed the extracted ROI frame-by-frame using the following steps:

Grayscale Conversion: Each ROI frame was converted to grayscale to simplify intensity analysis.

Frame Differencing: The absolute difference between each grayscale frame and its preceding frame was computed using OpenCV’s cv2.absdiff() function, which calculates pixel-wise intensity differences.

Thresholding: A binary threshold was applied to the difference image. Pixels with an intensity difference greater than a defined diff_threshold were assigned a value of 255 (white), while all others were set to 0 (black). This emphasized areas of significant motion, typically corresponding to blood flow during a heartbeat.

White Pixel Summation: The total number of white pixels in the thresholded image was calculated for each frame.

Beat Detection: If the white pixel count exceeded a predefined movement_count threshold, the frame was considered to reflect a cardiac contraction.

This process was repeated for every frame in the video. The number of beats detected in each 10-second interval was multiplied by six to estimate the heart rate in beats per minute (bpm).

To assess algorithm performance under varying sensitivity levels, we tested combinations of the following parameters in a matrix format:

This sensitivity analysis enabled us to identify optimal thresholds for reliable detection of heartbeat-induced motion while minimizing noise from minor movements or camera artifacts.

To evaluate the validity of the algorithm, manual heartbeat measurements were conducted using a digital tally counter (validation using manual counting). Observers visually inspected the same video and counted heartbeats based on observable blood flow pulses corresponding to ventricular contractions. This manual counting served as the gold standard against which algorithm-derived heart rate estimates were compared. The video was replayed multiple times to ensure consistent visual detection, and each heartbeat was defined as a single pulse of blood movement caused by cardiac contraction. The comparison with algorithmic estimates was conducted over identical 10-second time segments.

2.4. Manual Validation

To validate the detection results, a handheld tally counter was used to manually count visible heartbeats from the video footage. This manual count was used for comparison with the algorithmic estimation to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the heart rate detection system.

3. Results

Heart rate estimation was performed by calculating the number of detected peaks in each 10-second window and multiplying by six to yield beats per minute (bpm).

These values demonstrated consistency with the expected physiological range for Danionella larvae (the ground truth values obtained from manual counting using a handheld digital tally counter.). Visual inspection of the video confirmed that the detected rhythmic motion corresponded closely to cardiac contractions (

Table 1).

Average heart rate (HR) and standard deviation (SD) (Measured five times per animal)

Heart rate estimation using OpenCV. The green frame indicates the ROI.

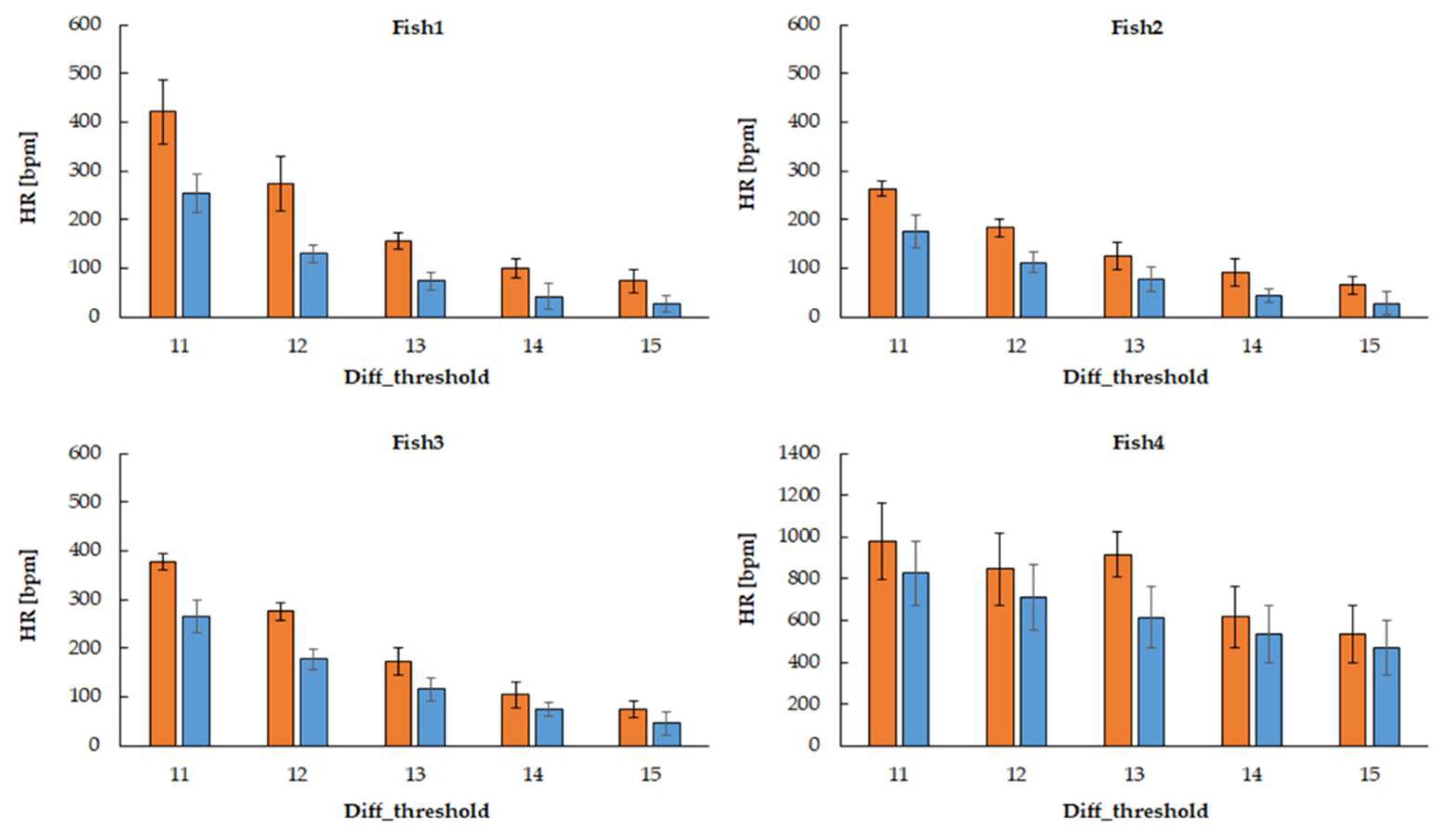

Expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Fish1 estimated five heart rates in a 50-second video. Fish2, 3, and 4 estimated six heart rates in a 60-second video. (Orange: movement_count≧1px, Blue: movement_count≧2px)

The higher the brightness threshold, the lower the estimated heart rate. Also, the higher the threshold for the sum of white pixels, the lower the estimated heart rate. Fish4 had drastic changes in body movement, causing a significant increase in the estimated heart rate.

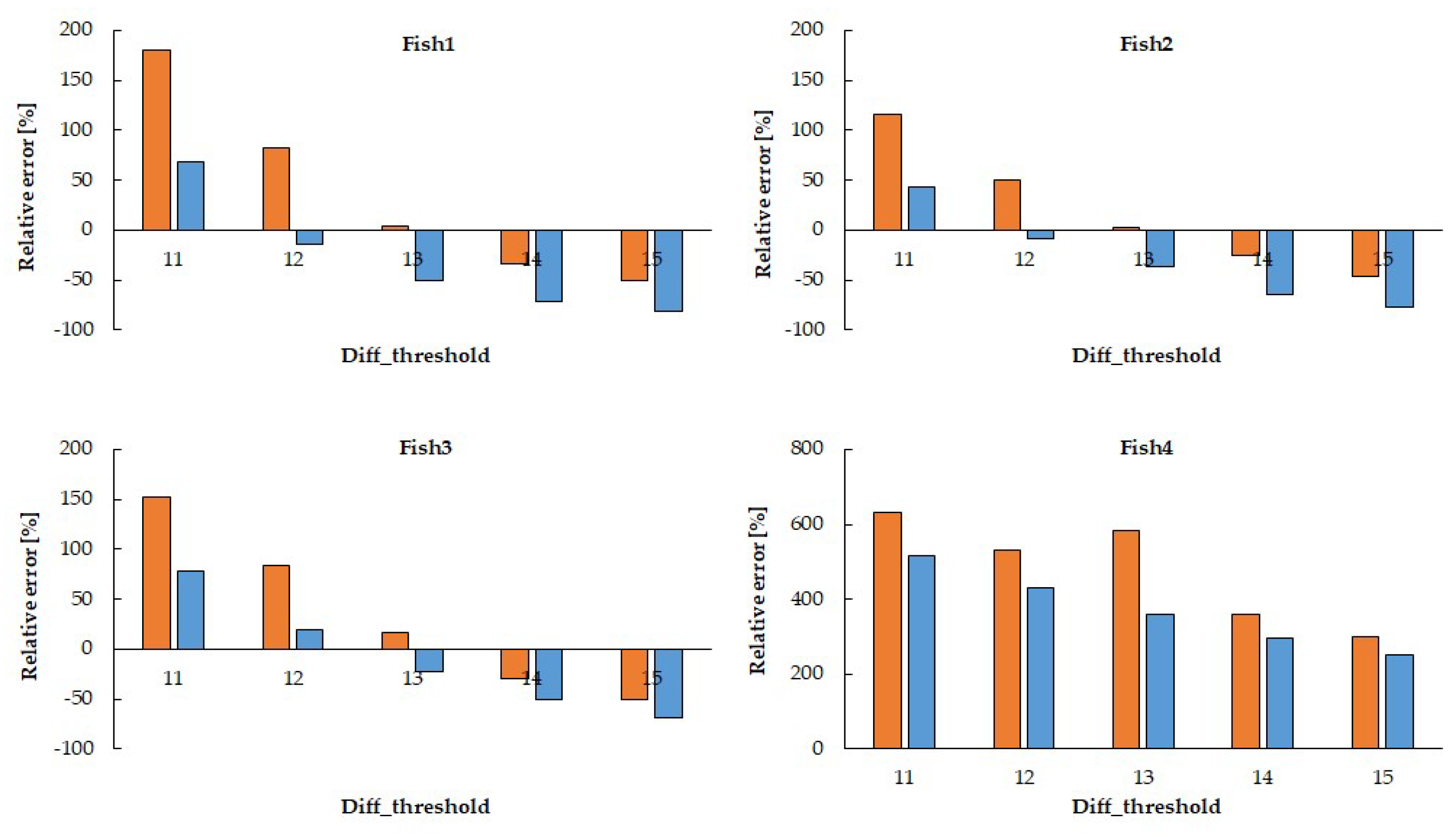

Orange: movement_count≧1px, Blue: movement_count≧2px

The parameters with the smallest relative error for each fish are

Fish1: diff_threshold=13, movement_count≧1px, relative error 3.72%

Fish2: diff_threshold=13, movement_count≧1px, relative error 2.94%

Fish3: diff_threshold=13, movement_count≧1px, relative error 16.31%

Fish4: diff_threshold=15, movement_count≧2px, relative error 25.97%

Results of object detection using Python OpenCV are shown in

Figure 2. The green frames indicate the ROIs. The estimated heart rate values (in

Figure 2) indicate the heart rate with the smallest relative error compared to the true value. Fish1-3 represents the heart rate when diff_threshold=13 and movemen_count≧1px, while Fish4 represents the heart rate when diff_threshold=15 and movemen_count≧2px. The heart rates at this time are Fish1: 156 ± 16 [bpm], Fish2: 126 ± 27 [bpm], Fish3: 174 ± 25 [bpm], and Fish4: 471 ± 131 [bpm] (final estimated values).

Figure 3 shows the average estimated heart rate when varying the brightness threshold and the total threshold of white pixels. In this ex-periment, five heart rates were estimated in 50 seconds (Fish1 video). Fish2, 3, and 4 are 60-second videos, and six heart rates were estimated. The results show that as the brightness threshold increases, the estimated heart rate decreases, and as the total white pixel threshold increases, the estimated heart rate also decreases. Fish 4 showed a significant increase in estimated heart rate due to intense body movement.

Figure 4 shows the relative error of the estimated heart rate compared to the manually counted (visual estimation) heart rate when varying the brightness threshold and the threshold for the total number of white pixels. The parameters yielding the smallest relative er-ror for each fish varied depending on the individual fish.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated a novel yet straightforward approach to estimating heart rate in Danionella larvae using a frame-differencing algorithm applied to video recordings. By extracting a fixed Region of Interest (ROI) around the visible cardiac area and analyzing luminance fluctuations between consecutive frames, we were able to detect periodic motion patterns corresponding to cardiac contractions. This technique, when paired with binary thresholding, effectively transformed subtle movements of blood flow into quantifiable image features.

One of the major strengths of this method lies in its simplicity and accessibility. The experimental setup utilized a consumer-grade waterproof video camera (JVC EverioR), and image analysis was performed with basic computer vision operations that require minimal computational power. As a result, the methodology is not only cost-effective but also portable and scalable for various laboratory settings. This makes it particularly attractive for researchers working in resource-limited environments or seeking non-invasive physiological assessment tools for aquatic model organisms.

The rhythmic increase in white pixel count—indicating heartbeat—was reliably detected across different time segments in the video. Heart rates estimated at 162, 138, 168, and 210 bpm over four 10-second intervals demonstrated that the system could capture physiological variability. These estimates were validated against manual counting using a handheld digital tally counter, which served as the gold standard in this study. The high degree of visual and quantitative agreement between the two methods supports the validity of our algorithm.

Heart rate monitoring in the zebrafish cardiovascular system has traditionally been performed manually (using a stopwatch) to count heartbeats. However, these methods are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and require specific training to execute. As a result, several automated measurement techniques have been developed [

24,

25,

26]. Many of these methods detect changes in active pixels between frames, defining the heart region as an arena and detecting heartbeats within the frame. However, these detection software tools are commercially available and some are difficult to implement [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

Compared to these methods, our approach is notably more accessible. By leveraging standard video resolution (1920×1080, 60i) and frame-difference analysis, we demonstrated that reliable heart rate estimation is possible without the need for advanced imaging systems. This positions our method as a valuable alternative for laboratories focusing on fundamental biological questions, especially where high-end instrumentation is unavailable. Moreover, Danionella species are increasingly recognized for their transparency and neurophysiological accessibility, making them ideal candidates for in vivo imaging. While previous studies have focused largely on zebrafish, the adaptation of similar techniques to Danionella is novel and contributes to the growing toolbox available for this emerging model organism.

Despite its advantages, the proposed method has several limitations. First, the system relies on the subject remaining stationary within the ROI. Any significant movement of the larva, such as swimming or body rotation, can shift the heart outside the fixed ROI, leading to inaccurate measurements or signal loss. While this was minimized in our current study by selecting periods of immobility, a robust implementation for live monitoring would require an automatic tracking system capable of dynamically adjusting the ROI.

Second, the threshold value for binary segmentation was determined heuristically. While effective in this experiment, this parameter may need tuning under different lighting conditions, fish orientations, or developmental stages. Future studies should investigate adaptive thresholding techniques or incorporate machine learning algorithms to improve generalizability.

Third, the frame rate (interlaced 60i) of the recording may introduce temporal artifacts that could influence the accuracy of motion estimation. Although we achieved meaningful results with this setup, higher frame rate recordings may enhance temporal resolution and allow for more precise heartbeat detection, especially in faster-beating or smaller hearts.

Additionally, validation against more precise physiological measurement systems—such as electrocardiography (ECG) or laser Doppler flowmetry—was not conducted in this study. While the digital tally counter served as a practical reference, it does not provide temporal precision at the millisecond level. Incorporating such gold-standard measurements in future work would offer a more rigorous evaluation of our algorithm’s accuracy.

As future perspectives, automating the ROI selection using object tracking techniques, such as centroid-based tracking (YOLO, You Only Look Once)[

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37], would increase robustness and applicability for longer recording durations or more active larvae. Furthermore, the integration of more sophisticated image processing techniques, including optical flow or frequency-domain analysis, could improve detection sensitivity and robustness in noisier conditions. These enhancements would extend the utility of our system not only for cardiac monitoring but also for analyzing other physiological parameters such as respiration or vascular dynamics.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a simple and accessible method for estimating heart rate in Danionella larvae using a frame-differencing algorithm applied to standard video recordings. By extracting a fixed Region of Interest (ROI) and analyzing luminance fluctuations between consecutive frames, we successfully detected cardiac motion patterns without the need for specialized imaging equipment. The heart rates estimated by this method showed good agreement with manual counting, validating its effectiveness. Compared to traditional manual techniques and commercially available software, our approach offers a cost-effective and easily implementable alternative, particularly suitable for laboratories with limited resources. Moreover, applying this method to Danionella expands available tools for studying this emerging model organism. Despite its advantages, limitations such as dependency on subject immobility, manually set thresholding, and frame rate constraints remain. Future work will focus on automating ROI tracking and enhancing image analysis to improve robustness and precision. Overall, our method provides a promising platform for non-invasive cardiac monitoring in small aquatic models, potentially contributing to broader physiological and developmental research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. One videos of the data used in this study are attached. If you would like to analyze other data for research purposes, please contact the authors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Y., methodology, E.Y. and Y.Y.; software, Y.Y.; validation, E.Y. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, E.Y. and Y.Y; investigation, E.Y.; resources, E.Y. and Y.S.; data curation, N.M and Y.Y; writing—original draft preparation, E.Y.; writing—review and editing, E.Y.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, E.Y.; project administration, E.Y.; funding acquisition, E.Y. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for animal experimentation in Japan and under the oversight of the Mie University Medical Zebrafish Research Center (MZRC,

https://zqsp-mie-u.org/mzrc/). The experimental protocol did not involve any toxicological testing or pharmacological interventions and was limited to non-invasive observational imaging of Danionella larvae using video. According to the Japanese national guidelines for animal experimentation, all vertebrate animals, including fish species, fall under the scope of ethical review. In compliance with these guidelines, we ensured that the experimental procedures minimized stress and avoided any unnecessary harm to the animals. The entire study was performed under ambient laboratory conditions without the use of anesthesia or surgical manipulation. No mortality or adverse effects were observed during or after the observation sessions.

Informed Consent Statement

This study does not constitute human subjects’ research.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the analysis of this study will be made available for research purposes with the consent of the dataset provider, but will only be made available to research institutions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Kazu Kikuchi, MD, PhD, Director of the Department of Cardiac Regeneration, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center Research Institute, for generously providing Danionella used in this study. His support and contribution were essential to the successful execution of the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chan, P.K.; Lin, C.C.; Cheng, S.H. Noninvasive technique for measurement of heartbeat regularity in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. BMC Biotechnol. 2009, 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6750-9-11. [CrossRef]

- Denvir, M.A.; Tucker, C.S.; Mullins, J.J. Systolic and diastolic ventricular function in zebrafish embryos: Influence of norepinephrine, MS-222 and temperature. BMC Biotechnol. 2008, 8, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6750-8-21. [CrossRef]

- Fink, M.; Callol-Massot, C.; Chu, A.; Ruiz-Lozano, P.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C.; Giles, W.; Bodmer, R.; Ocorr, K. A new method for detection and quantification of heartbeat parameters in Drosophila, zebrafish, and embryonic mouse hearts. Biotechniques 2009, 46, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.2144/000113078. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, E.; Drexel, M.; Schwerte, T.; Pelster, B. Influence of hypoxia and of hypoxemia on the development of cardiac activity in zebrafish larvae. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002, 283, R911–R917. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00140.2002. [CrossRef]

- Bass, A.H.; Perelmuter, J.T. Danionella fishes. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1767–1769. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02433-0. [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.Y. Longitudinal in vivo imaging of adult Danionella cerebrum using standard confocal microscopy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2022, 15, dmm049753. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.049753. [CrossRef]

- Schulze, L.; Henninger, J.; Kadobianskyi, M.; Chaigne, T.; Faustino, A.I.; Hakiy, N.; Albadri, S.; Schuelke, M.; Maler, L.; Del Bene, F.; Judkewitz, B. Transparent Danionella translucida as a genetically tractable vertebrate brain model. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 977–983. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0144-6. [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, N.; Kalix, L.; Possiel, J.; Stasch, R.; Kusian, T.; Köster, R.W.; von Trotha, J.W. A comparative analysis of Danionella cerebrum and zebrafish (Danio rerio) larval locomotor activity in a light-dark test. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 885775. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.885775. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, Z.; Wu, D.; Dai, Z.; Hughes, D.; Sugahara, T.; Izumi, S.; Yang, Y. Flexible, Non-Invasive, and Wearable Fish Heart Rate Monitoring Tag for Guiding Aquaculture in Marine Ranching. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 1–4.

- Shen, Y.; Arablouei, R.; de Hoog, F.; Xing, H.; Malan, J.; Sharp, J.; Shouri, S.; Clark, T.D.; Lefevre, C.; Kroon, F.; Severati, A.; Kusy, B. In-Situ Fish Heart-Rate Estimation and Feeding Event Detection Using an Implantable Biologger. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 22, 968–982.

- Shen, Y.; Arablouei, R.; de Hoog, F.; Malan, J.; Sharp, J.; Shouri, S.; Clark, T.D.; Lefevre, C.; Kroon, F.; Severati, A.; Kusy, B. Estimating Heart Rate and Detecting Feeding Events of Fish Using an Implantable Biologger. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN), Sydney, Australia, 21–24 April 2020; pp. 37–48.

- Puybareau, É.; Talbot, H.; Léonard, M. Automated heart rate estimation in fish embryo. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools and Applications (IPTA), Orleans, France, 10–13 Nov 2015; pp. 379–384.

- Hoover, A.W.; Singh, A.; Fishel-Brown, S.; Muth, E. Real-time detection of workload changes using heart rate variability. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2012, 7, 333–341.

- Eleuteri, A.; Fisher, A.C.; Groves, D.; Dewhurst, C.J. An Efficient Time-Varying Filter for Detrending and Bandwidth Limiting the Heart Rate Variability Tachogram without Resampling: MATLAB Open-Source Code and Internet Web-Based Implementation. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012, 2012, 578785.

- Fisher, A.C.; Eleuteri, A.; Groves, D.; Dewhurst, C.J. The Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Third-Order Gaussian Process (OUGP) Applied Directly to the Un-Resampled Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Tachogram for Detrending and Low-Pass Filtering. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2012, 50, 737–742.

- Esteban, M.Á.; Cuesta, A.; Chaves-Pozo, E.; Meseguer, J. Influence of Melatonin on the Immune System of Fish: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7979–7999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047979. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.A.M.; Król, E. Nutrigenomics and Immune Function in Fish: New Insights from Omics Technologies. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 75, 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2017.02.024. [CrossRef]

- Blazer, V.S.; Walsh, H.L.; Braham, R.P.; Smith, C. Necropsy-Based Wild Fish Health Assessment. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 139, 57946. https://doi.org/10.3791/57946. [CrossRef]

- Dimitroglou, A.; Merrifield, D.L.; Carnevali, O.; Picchietti, S.; Avella, M.; Daniels, C.; Güroy, D.; Davies, S.J. Microbial Manipulations to Improve Fish Health and Production—A Mediterranean Perspective. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011, 30, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2010.08.009. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K. Fish Health—Some Concepts, Constraints, and Comparisons. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1975, 245, 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb26826.x. [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Teles, A. Nutrition and Health of Aquaculture Fish. J. Fish Dis. 2012, 35, 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01333.x. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.M.; Waagbø, R.; Espe, M. Functional Amino Acids in Fish Nutrition, Health, and Welfare. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2016, 8, 143–169. https://doi.org/10.2741/757. [CrossRef]

- Segner, H.; Sundh, H.; Buchmann, K.; Douxfils, J.; Sundell, K.S.; Mathieu, C.; Ruane, N.; Jutfelt, F.; Toften, H.; Vaughan, L. Health of Farmed Fish: Its Relation to Fish Welfare and Its Utility as Welfare Indicator. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 38, 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-011-9517-9. [CrossRef]

- Esteban, M.Á.; Cuesta, A.; Chaves-Pozo, E.; Meseguer, J. Influence of Melatonin on the Immune System of Fish: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7979–7999. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14047979. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.A.M.; Król, E. Nutrigenomics and Immune Function in Fish: New Insights from Omics Technologies. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 75, 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2017.02.024. [CrossRef]

- Blazer, V.S.; Walsh, H.L.; Braham, R.P.; Smith, C. Necropsy-Based Wild Fish Health Assessment. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 139, 57946. https://doi.org/10.3791/57946. [CrossRef]

- Dimitroglou, A.; Merrifield, D.L.; Carnevali, O.; Picchietti, S.; Avella, M.; Daniels, C.; Güroy, D.; Davies, S.J. Microbial Manipulations to Improve Fish Health and Production—A Mediterranean Perspective. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011, 30, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2010.08.009. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K. Fish Health—Some Concepts, Constraints, and Comparisons. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1975, 245, 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb26826.x. [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Teles, A. Nutrition and Health of Aquaculture Fish. J. Fish Dis. 2012, 35, 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01333.x. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.M.; Waagbø, R.; Espe, M. Functional Amino Acids in Fish Nutrition, Health, and Welfare. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2016, 8, 143–169. https://doi.org/10.2741/757. [CrossRef]

- Segner, H.; Sundh, H.; Buchmann, K.; Douxfils, J.; Sundell, K.S.; Mathieu, C.; Ruane, N.; Jutfelt, F.; Toften, H.; Vaughan, L. Health of Farmed Fish: Its Relation to Fish Welfare and Its Utility as Welfare Indicator. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 38, 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-011-9517-9. [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, S.; Liang, Z.; Xue, Z.; Antani, S. Ensembled YOLO for Multiorgan Detection in Chest X-Rays. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2025, 13407, 134073I. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3047210. [CrossRef]

- Sobek, J.; Medina Inojosa, J.R.; Medina Inojosa, B.J.; Rassoulinejad-Mousavi, S.M.; Conte, G.M.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Erickson, B.J. MedYOLO: A Medical Image Object Detection Framework. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2024, 37, 3208–3216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-024-01138-2. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Smith, T.G.; Arunachalam, S.P.; Tolkacheva, E.G.; Cheng, C. Image-Decomposition-Enhanced Deep Learning for Detection of Rotor Cores in Cardiac Fibrillation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 71, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2023.3292383. [CrossRef]

- Micheli, M.; Papa, G.; Negri, I.; Lancini, M.; Nuzzi, C.; Pasinetti, S. BEEHIVE: A Dataset of Apis mellifera Images to Empower Honeybee Monitoring Research. Data Brief 2024, 57, 111055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2024.111055. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.H.; Li, J.R.; Shieh, W.Y. The Application of Emotion Valence Ratios in Facial Emotion Recognition for Detecting Depression Among Older Adults in Institutional Settings. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 318, 194–195. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI240924. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.G.; Choi, H.Y.; Lee, D.; Kong, J.W.; Kang, G.H.; Jang, Y.S.; Kim, W.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; et al. Detection of Aortic Dissection and Intramural Hematoma in Non-Contrast Chest Computed Tomography Using a You Only Look Once-Based Deep Learning Model. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6868. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13226868. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).