In the final step of the statistical analysis, we analyze the variables through DiD regression models. The section will be subdivided into two sections: the first section analyzes the overall score that represents the general severity and frequency of injuries and complaints. The second section includes regression model with the perceived training intensity as the dependent variable. In both parts we tested the independent variables of the correlation analysis, even though they did not show statistically significant correlations in the bivariate correlation matrix. This approach, as we argue, is justified because a lack of significant bivariate correlation does not necessarily imply a lack of predictive value when other variables are controlled for. Moreover, we applied a stepwise regression analysis, starting with a simple DiD regression model without covariates and continuing with multivariate regression models that also include additional controlled variables. We published the best models and excluded those models and variables that decreased the accuracy and robustness of the model.

5.5.1. Overall Injury Score as Dependent Variable

As we already specified in

Section 3, the analysis of the overall injury score consists of four parts. For the first two parts we focus on the individual time periods, of which the first one starts with the baseline test and ends with first post-test and the second one starts with the first post-test and ends with the second post-test. In the third part we analyze the entire time period from the beginning to the end of the trial, before in the fourth part we test a dynamic DiD regression model that incorporates both time periods with individual treatment effects.

The first regression model in

Table 6 is a difference-in-differences (DiD) regression model that evaluates the effect of the intervention on the overall level of injury and complaints between the baseline test and the first post-test. The model consists of three main predictors: (1) the time variable, which compares the baseline test and first post-test, (2) the group assignment, which compares the intervention group with the control group (the intervention group serves as reference group) and (3) the interaction term. This is the basic structure of all static regression models. The interaction term between time and group is the most crucial variable in the model because it estimates the differential change in the outcome between the two groups over time.

Looking at the coefficient of the time variable regression model 1 we can observe that the overall injury score decreases on average by 5.83 score points. However, the coefficient has a p-value of 0.12, which means that the change in the overall score from the baseline test to the first post-test is not statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Moreover, the interaction term suggests that the changes from the baseline test to the first post-test in the intervention group does not significantly differ from the control group with a coefficient of 1.25 and a p-value of 0.82. Overall, the model suggests that neither the intervention nor the time-period starting with the baseline test and ending with the first post-test had a strong effect on the overall score.

Regression model 2 in

Table 7 analyzes not only the effect of the intervention between the baseline test and the first post-test, but also incorporates additional covariates such as BMI, age and the relative usage of mountain bikes. As can be seen in the individual coefficients, it aligns with model 1 regarding the time effect and the group variable. The interaction term, which represents the difference-in-differences effect, has a coefficient of 1.23, indicating that the change in the overall score from the baseline test to the first post-test was on average 1.23 points greater (lower injury scores) than in the control group. However, this difference is not statistically significant with a p-value of 0.82. In other words, the model could not confirm our original assumption stating that the application of the Blackroll

® results in less severe and frequent health complaints and injuries after three months.

Among the covariates only the variable bicycle type mountain bike seems to have an impact on the overall injury level. For the other covariates we could not observe any statistically significant effect on the overall injury score. For the usage of mountain bikes, we can see a coefficient of -0.22 with a p-value of 0.02, which means that participants, who used mountain bikes (measured in percent of their overall bicycle exercise time), had slightly lower injury scores than the control group. In sum, although the direction of the time effect and the group differences are in line with our basic assumptions, none of the central variables associated with the intervention reach statistical significance. The only noteworthy predictor is the type of bicycle, which appears to be linked to lower injury scores.

In

Table 8 and

Table 9 we analyzed the same structure of the model, but for the period from the first post-test to the second post-test. Model 3 in

Table 8 explains almost none of the variance in the outcome, as indicated by an R-squared value of 0.001 and an adjusted R-squared of -0.044. The interaction term, which would indicate whether the change in injury scores between the first and second post-test differed significantly between the intervention and control groups over time, is essentially zero (0.03) with a p-value of 0.994. This means there is no evidence that the intervention had a different effect over this time- period compared to the control group.

Regression model 4 analyzes in addition to the intervention also the impact of additional covariates from the first post-test to the second post-test. The R-squared value of 0.092 indicates that the model slightly improved compared to the simple regression model, but the value is still very low with only about 9.2%. The adjusted R-squared drops to just 0.5%, suggesting that the explanatory power of the model is quite weak, even after adjusting for additional covariates.

Looking at the individual variables, the coefficient for the time variable is -0.40, with a p-value of 0.88, which tells us that no significant change in injury scores occurred in the intervention group between the two post-tests. The control group coefficient is also not significant (p = 0.591) and neither is the interaction term (p = 0.977), which indicates that the change in injury scores over time does not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups. Overall, the model finds no statistically significant differences in injury scores between groups or over time from the first post-test to the second post-test and there is no evidence that the intervention had a measurable impact during this period, even after accounting for individual characteristics such as BMI, age or bicycle type.

In the next step we analyze the impact of the intervention over the entire period, beginning with the baseline test and ending with the second post-test. As the summary of the model in

Table 10 shows, the interaction term has a coefficient of 1.27. Unfortunately, this coefficient is small and far from significant with a p-value of 0.81, which means that we are not able to confirm our basic assumption that the intervention has an impact on the overall level of injury within a period of six months. Furthermore, the model’s explanatory power is quite limited with an R-squared of 0.07, which means that only 7% of the variance in the overall score variable can be explained by the model.

The model in

Table 11 goes one step further and includes several more explanatory variables. In addition to the time variable, group variable and the interaction term, the model also accounts for the additional covariates BMI, age and bicycle type mountain bike. Regarding our main dependent variable

overall injury score, the conclusions, which can be derived from the multivariate model, do not differ significantly from the simple regression model in

Table 10. The interaction term has a coefficient of 1.34 with a p-value of 0.79, indicating that the change in the intervention group’s score from baseline to the second post-test is on average 1.34 points greater than the change in the control group’s score. However, the p-value of 0.79 suggests that this difference is not statistically significant. In other words, the model could not confirm our assumption that the application of the Blackroll

® has an impact on the overall level of injury and complaints.

Looking at the covariates in the model, we can conclude that neither the BMI nor the age had a statistical impact on the overall injury score, although the age variable shows a higher significance with a p-value of 0.1. The only variable that shows a statistically significant impact on the overall injury level is the usage of a mountain bike, which has regression coefficient of 0.22 and which is statistically significant at the 0.05 level with a p-value of 0.018. This suggests that participants, who use a mountain bike more frequently compared to other bicycle types, are likely to have a lower overall injury score compared to those who do not. When we compare the multivariate model in

Table 11 with the simple model in

Table 10, we can observe that the multivariate model implies a higher R-squared value of 0.156, which suggests that the 15.6% of the variability in the overall injury score can be explained by the model.

To summarize these findings, it is concluded that the overall injury level decreased from the baseline test to the second post-test, but the differences between the intervention and control group are minor and not statistically significant. An R-squared value of 0.156 means that the overall model and its predictors do not show strong statistical significance and that there might be additional factors which explain the variability in the overall score. One interesting insight, however, is the impact of the usage of mountain bikes on the overall injury level, indicating that mountain bikes involve less severe and frequent injuries than other types of bicycles.

Finally, we investigate the dynamic DiD regression model, which incorporates both time periods and accounts a separate treatment effect for each time-period. The first dynamic model without covariates examines the effects of the intervention on the overall score over time, using only the group assignment (intervention or control) and time indicators. The model explains 6.7% of the variance in the overall score, with an adjusted R-squared of 2.0%, suggesting a very low explanatory power.

The time indicators for the first (P1) and second (P2) post-tests show negative coefficients of -4.59 and -5.12, indicating lower overall scores at these time points compared to the baseline test. However, these results are not statistically significant (p = 0.188 and p = 0.142), which suggests that the overall scores did not change significantly between the baseline test and the first or second post-test. The treatment effect for the intervention group at the first and second post-tests is represented by the coefficients of 1.25 and 1.27, both of which are not statistically significant (p = 0.797 and p = 0.793). Similar to the previous model, the intervention did not result in a significant change in the overall score at both of the post-test periods compared to the control group.

In sum, the dynamic DiD model without covariates provides no evidence of a significant impact of the intervention on the overall score in both time periods. The results are consistent with our earlier findings, which did not detect a statistically significant effect of the intervention on the outcome.

Table 12.

Regression model 7 shows a dynamic regression model and estimates the impact of the intervention and additional covariates from the baseline test to the first post-test and from the first post-test to the second post-test on the overall score (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 12.

Regression model 7 shows a dynamic regression model and estimates the impact of the intervention and additional covariates from the baseline test to the first post-test and from the first post-test to the second post-test on the overall score (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

12.39 |

2.38 |

5.21 |

0.00 |

[7.67, 17.11] |

| Time (P1) |

-4.59 |

3.46 |

-1.33 |

0.19 |

[-11.46, 2.28] |

| Time (P2) |

-5.12 |

3.46 |

-1.48 |

0.14 |

[-11.99, 1.75] |

| Group (control group) |

-1.39 |

3.41 |

-0.41 |

0.69 |

[-8.16, 5.38] |

| Interaction term (P1) |

1.25 |

4.83 |

-0.26 |

0.80 |

[-10.82, 8.33] |

| Interaction term (P2) |

1.27 |

4.83 |

-0.26 |

0.79 |

[-10.85, 8.31] |

Table 13.

Regression model 8 shows a dynamic regression model and estimates the impact of the intervention and additional covariates from the baseline test to the first post-test and from the first post-test to the second post-test on the overall score (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 13.

Regression model 8 shows a dynamic regression model and estimates the impact of the intervention and additional covariates from the baseline test to the first post-test and from the first post-test to the second post-test on the overall score (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

6.88 |

12.42 |

0.55 |

0.58 |

[-17.78, 31.53] |

| Time (P1) |

-4.58 |

3.36 |

-1.36 |

0.18 |

[-11.26, 2.09] |

| Time (P2) |

-5.12 |

3.36 |

-1.52 |

0.13 |

[-11.79, 1.56] |

| Group (control group) |

-3.73 |

3.45 |

-1.08 |

0.28 |

[-10.57, 3.12] |

| Interaction term (P1) |

-1.24 |

4.69 |

-0.27 |

0.79 |

[-10.55, 8.07] |

| Interaction term (P2) |

-1.29 |

4.69 |

-0.27 |

0.78 |

[-10.60, 8.02] |

| BMI |

-0.06 |

0.51 |

-0.12 |

0.91 |

[-1.07, 0.95] |

| Age |

0.28 |

0.14 |

1.97 |

0.05 |

[-0.00, 0.57] |

| Type mountain bike |

-0.18 |

0.07 |

-2.73 |

0.01 |

[-0.32, -0.05] |

Model 8 examines how the overall score evolved over time between the intervention and control groups, while also accounting for individual characteristics such as BMI, age, and bike type. The model explains approximately 14.7% of the variance in the outcome, with an adjusted R-squared of 7.5%. The coefficients of the time indicators show that overall scores at the first (P1) and second (P2) post-tests were lower than the baseline with decreases of about 4.58 and 5.12 score points. However, these changes over time are not statistically significant. The dynamic treatment effects are captured by the interaction terms P1 and P2, which estimate the additional impact of being in the intervention group at each post-test relative to the control group. Both coefficients are small (1.24 and 1.29) and clearly non-significant with p-values greater than 0.7. Just as we established with our previous models, the dynamic multivariate model suggests that the intervention had no significant effect on the outcome during both time periods when compared to the control group. Among the control variables the variable age shows a marginally significant positive effect (p = 0.051), indicating that older participants may tend to score slightly higher. The only statistically significant predictor in the model is the use of mountain bikes. Participants, who use a mountain bike, scored on average 0.18 points lower than others, who predominantly use other bicycle types, a result that is statistically significant at the 1% level.

In summary, the dynamic DiD model provides no evidence that the intervention produced significant changes in overall scores at neither of the post-tests compared to the control group. The findings confirm the static DiD models and allow us to conclude that no measurable treatment effect could be observed.

5.5.2. Perceived Intensity as Dependent Variable

In the second part of the DiD regression analysis we investigate the impact of the intervention on the perceived training intensity. The training intensity represents a scale between 0 and 10 with higher values standing for a more intense training. To analyze the variable intensity, we conduct the same steps as in the previous section. First, the analysis focuses on the impact of the intervention in the individual time periods: on the one hand, from the baseline test to the first post-test, and on the other hand, from the first post-test to the second post-test. In the next step, we run a DiD regression on the entire trial. Finally, we test a dynamic DiD regression model that accounts for both time periods in one model and individual treatment effects for each time period. Similar to the analysis of the injury score, we show two models for each step, of which the first one will be a simple regression model with the time variable, the group variable and the interaction term. The second model will include additional variables as covariates.

As the results in regression model 8 shows, the model fits the data quite well as the adjusted R-squared value of 0.710 suggests. First, the intercept is at 3.964, which in a DiD regression model represents the perceived training intensity at the baseline test when all the independent variables are at their baseline level. The time variable shows that the intensity in both groups increased over time, with a coefficient of 2.145 and high statistical significance (p < 0.01), which means that the dependent variable training intensity is on average 2.15 units higher compared to the baseline test. Most importantly, the interaction term shows a coefficient of 0.802 and a high statistical significance (p < 0.05), which means the changes from the baseline test to the first post-test were 0.8 greater in the control group than in the intervention group. In other words, intensity increased in both groups over time, but the change in intensity of the intervention group was lower than in the control group. The control group tends to have a lower intensity, but this gap widens at the first post-test, as shown by the interaction term.

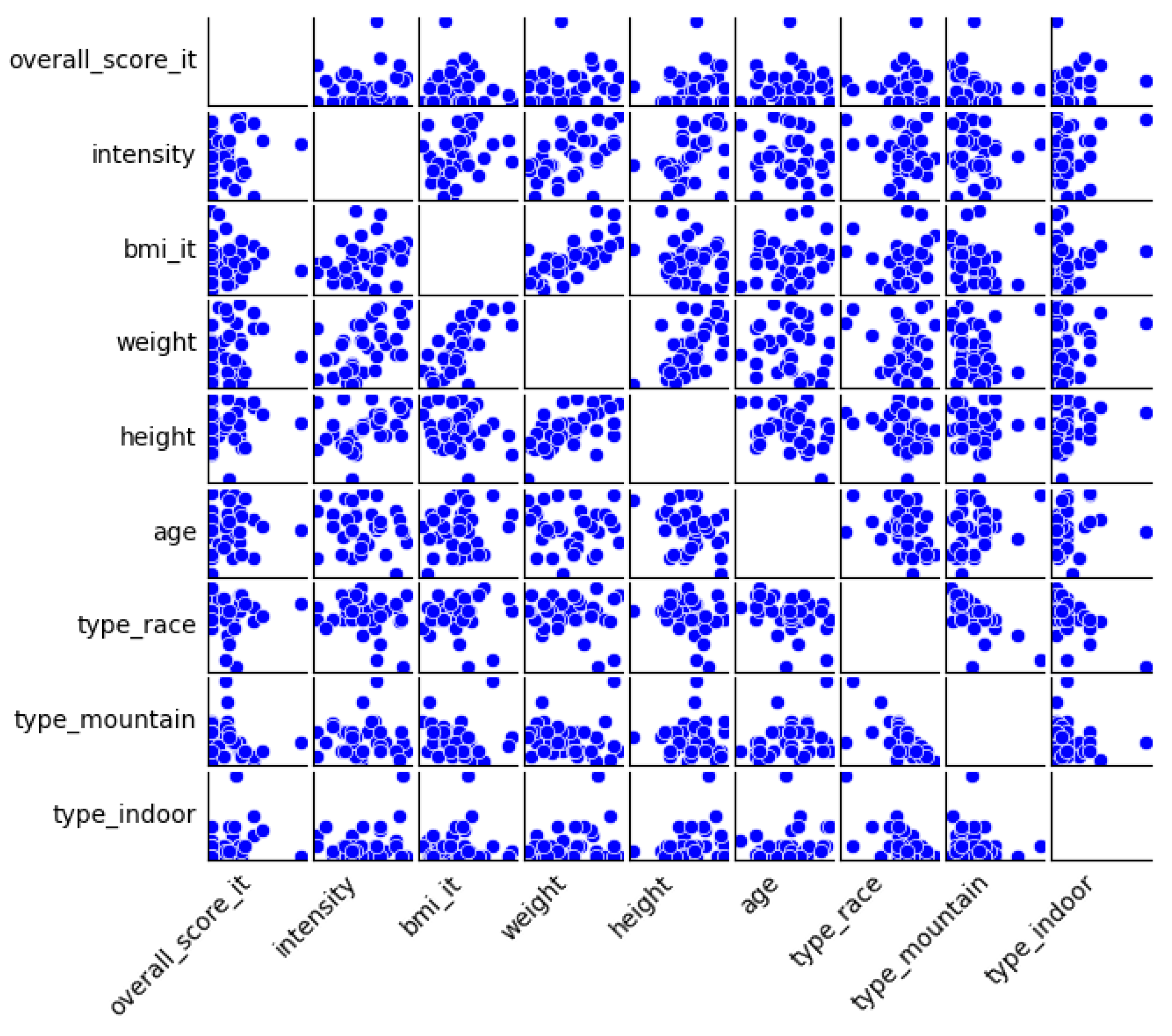

In addition to the simple DiD regression model, we now conduct a multivariate DiD regression model, which includes additional covariates. We decided to prioritize the variable weight as covariate because the variable had the highest correlation with the intensity, as in section 3.4 was shown. Furthermore, the variables age and bicycle type mountain bike were excluded from the model because of a variety of reasons. First, none of those two variables showed any sign of association with the perceived training intensity in the correlation analysis, even though we expected a correlation, at least between age and training intensity. Second, the inclusion of the two variables significantly reduces the accuracy and fitness of the regression model. Other variables, which we excluded from the model, were the variables BMI and height, even though we found a moderate positive statistically significant correlation between these two variables and the perceived training intensity. The reason for this is that the independent variables in a regression model should not correlate with each other due to the problem of multicollinearity.

As can be derived from the results in

Table 14, the multivariate DiD model has an adjusted R-squared of 0.734, which means that 73.4 % of the variability in the dependent variable can be explained by the model. Compared to the simple regression in our first model, R-squared improved, but only slighty by one percentage point.

The multivariate model reveals results for the coefficient and p-value of the time variable (2.145, p=0.000), which are like the previous model. Both groups experienced an increase in intensity over time. Looking at the treatment effect variable allows us to conclude that the impact of the intervention on the perceived training intensity remains strong and statistically significant (0.80, p = 0.039), even after accounting for weight. This term tells us that the change in intensity from the baseline test to the first post-test was 0.80 units higher in the control group than the change observed in the intervention group. In other words, while both groups experienced an increase in intensity over time, the increase was significantly greater in the control group. The rejection of the null hypothesis for the interaction term implies a statistically meaningful difference in how intensity changed over time between the two groups.

The coefficient for body weight is positive and statistically significant (0.0326, p = 0.011), indicating that for each additional kilogram of body weight, the intensity increases by about 0.033 units, while the variable remains constant. This suggests that heavier individuals tend to report a slightly higher training intensity. This effect is relatively small in absolute terms, but it is statistically significant (p = 0.011), which means we can reject the null hypothesis that weight has no impact on intensity. Individuals with higher body weight tend to perceive their training as more intense, which could reflect differences in physical exertion or perceived effort due to body composition. This relationship holds regardless of time point or group, since the model assumes the effect of weight is constant across both groups and time.

In regression model 10 in

Table 15 the goal was to estimate the effect of the predictors time, group and the interaction term on the perceived training intensity for the second time-period, which started with the first post-test and ended with the second post-test. As can be seen in the R-squared value, the model explains about 38% of the variation in the perceived training intensity, which means that the model has a moderate explanatory power. For the time variable the model estimated a coefficient of 0.81, which indicates that the intensity increased in both groups – a result that is highly significant with p = 0.002. Regarding the group variable, we did not find a statistically significant difference between the groups at the first post-test (-0.089, p = 0.726). The interaction effect indicates that the change in the control group is slightly greater than in the intervention group. However, the p-value for the interaction term is 0.130, which means that it is not statistically significant at conventional threshold. In other words, there is no strong statistical evidence suggesting that the intervention group changed differently over time compared to the control group, nor that the two groups differed significantly at any specific time point.

In

Table 16 we updated the model by including the variable weight as covariate in addition to the time variable, group variable and the interaction term. Compared to the previous model without the covariate, the R-squared has increased slightly from 0.376 to 0.393, indicating a marginal improvement in the model’s explanatory power. However, this increase is modest and given that body weight is not a statistically significant predictor, the added complexity does not lead a substantial gain in the accuracy of the model. The interaction term, which is our most crucial variable, has a positive coefficient of 0.548, which suggests that the control group may have experience a slightly greater increase in intensity over time compared to the intervention group, but this effect is not statistically significant at the p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 level (p-value = 0.127). The new covariate weight has a coefficient of 0.015, suggesting that for each additional kilogram of body weight, training intensity increases by approximately 0.015 units.

Table 13.

Regression model 9 estimates the impact of the intervention from the baseline test to the first post-test on the perceived training intensity (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 13.

Regression model 9 estimates the impact of the intervention from the baseline test to the first post-test on the perceived training intensity (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

3.964 |

0.161 |

25.571 |

0.000 |

[3.642, 4.287] |

| Time |

2.954 |

0.228 |

12.948 |

0.000 |

[2.499, 3.410] |

| Group (control group) |

-0.892 |

0.232 |

-3.851 |

0.000 |

[-1.354, -0.429] |

| Interaction term |

1.350 |

0.327 |

4.124 |

0.000 |

[0.697, 2.004] |

Table 14.

Regression model 10 estimates the impact of the intervention from the baseline test to the first post-test on the perceived training intensity with additional covariates (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 14.

Regression model 10 estimates the impact of the intervention from the baseline test to the first post-test on the perceived training intensity with additional covariates (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

1.378 |

1.008 |

1.367 |

0.176 |

[-0.636, 3.392] |

| Time |

2.145 |

0.266 |

8.059 |

0.000 |

[1.613, 2.677] |

| Group (control group) |

-0.708 |

0.279 |

-2.537 |

0.014 |

[-1.265, -0.151] |

| Interaction term |

0.803 |

0.382 |

2.015 |

0.039 |

[0.040, 1.565] |

| Weight |

0.033 |

0.012 |

2.611 |

0.011 |

[0.008, 0.057] |

Table 15.

Regression model 11 estimates the impact of the intervention from the first post-test to the second post-test on the perceived training intensity (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 15.

Regression model 11 estimates the impact of the intervention from the first post-test to the second post-test on the perceived training intensity (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

6.109 |

0.176 |

34.76 |

0.000 |

[5.758, 6.460] |

| Time |

0.809 |

0.249 |

3.256 |

0.002 |

[0.313, 1.306] |

| Group (control group) |

-0.089 |

0.252 |

-0.352 |

0.726 |

[-0.592, -0.415] |

| Interaction term |

0.548 |

0.357 |

1.535 |

0.130 |

[-0.165, 1.260] |

Table 16.

Regression model 12 estimates the impact of the intervention from the first post-test to the second post-test on the perceived training intensity with additional covariates (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 16.

Regression model 12 estimates the impact of the intervention from the first post-test to the second post-test on the perceived training intensity with additional covariates (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

4.891 |

0.936 |

5.223 |

0.000 |

[3.021, 6.761] |

| Time |

0.809 |

0.247 |

3.275 |

0.002 |

[0.316, 1.303] |

| Group (control group) |

-0.002 |

0.259 |

-0.009 |

0.993 |

[-0.520, 0.515] |

| Interaction term |

0.548 |

0.355 |

1.544 |

0.127 |

[-0.161, 1.256] |

| Weight |

0.015 |

0.012 |

1.324 |

0.190 |

[0.008, 0.038] |

The regression model 12 in

Table 17 provides an analysis of the relationship between the training intensity, on the one hand, and group membership and the interaction between time and group, on the other, starting with the baseline test and ending with the second post-test. In other words, this DiD regression model estimates the impact of the intervention over the entire trial. Overall, the model has a relatively high R-squared value of 0.885, which means that 88.5% of the variance in the training intensity can be explained by the independent variables included in the model. The adjusted R-squared value is 0.879, which adjusts for the number of predictors in the model and is still quite high, indicating a good fit.

Looking at the individual variables, we can conclude that the intensity of the training increased from the baseline test to the second post-test independent from group affiliation. With a coefficient of 2.954 and a p-value of 0.000 we can conclude with a relatively high certainty that on average the training intensity increased by 2.954 units from the baseline test to the second post-test. The interaction term between time and group is 1.3503, which means that the difference in training intensity between the intervention and control group is greater at the second post-test compared to the baseline test. To be more specific, the difference in training intensity between the intervention and control group at the second post-test is 1.35 units greater than at the baseline test. With a p-value of 0.000 this effect shows a high statistical significance. The interaction between time and group further strengthens the assumption, that the effect of time on training intensity is greater for the control group than for the intervention group.

In regression model 13 we extend the previous model with the covariate weight. As the summary statistics of the regression model shows, R-squared slightly increases with the additional covariate, but only by 0.7 percentage points. The model confirms most of the findings in the previous model, indicating a strong and statistically significant impact of the intervention on the perceived training intensity. All variables show a high level of statistical significance, the effect of the intervention expressed in the interaction term remains strong and statistically significant, even after controlling for weight.

Table 18.

Regression model 14 estimates the impact of the intervention from the baseline test to the second post-test on the perceived training intensity with additional covariates (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 18.

Regression model 14 estimates the impact of the intervention from the baseline test to the second post-test on the perceived training intensity with additional covariates (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

2.158 |

0.841 |

2.567 |

0.013 |

[0.479, 3.836] |

| Time |

2.954 |

0.222 |

13.314 |

0.000 |

[2.511, 3.398] |

| Group (control group) |

-0.763 |

0.233 |

-3.281 |

0.002 |

[-1.228, -0.299] |

| Interaction term |

1.350 |

0.318 |

4.241 |

0.000 |

[0.714, 1.986] |

| Weight |

0.023 |

0.010 |

2.188 |

0.032 |

[0.002, 0.044] |

Whereas the previous models estimated the effects of the intervention and additional covariates on the intensity from one point in time to another point in time, the last two DiD regression models analyzed in the following paragraphs represent dynamic models that provide a more nuanced picture of how training intensity evolved over time by incorporating treatment effects for each time period.

The dynamic DiD regression model 14 explains a substantial proportion of the variance in intensity with an R-squared of 0.815 and an adjusted R-squared of 0.805, which indicates a strong fit of the model to the data points. The intercept, which represents the mean intensity in the control group at the baseline test, is estimated at 3.96. Compared to this baseline, the training intensity increases significantly over time. At the first post-test, intensity increases by about 2.145 units and at the second post-test, it increases even more by about 2.954 units – both effects are statistically significant with p-values < 0.001. This suggests that the control group experienced substantial increases in intensity over time. Most importantly, the interaction terms, which represent the additional change in the intervention group, are both aligned with our previous models. The coefficient for the first treatment effect is about 0.803 and significant at the 5% level (p = 0.029), while the coefficient for the second treatment effect is even stronger 1.350 and a p-value < 0.001 (p = 0.000). As the results indicate, both groups showed an increase in the perceived training intensity, however, the increases in the intervention group were consistently and significantly lower than the increases in intensity in the control group.

Finally, we added the weight as covariate to the model in addition to the time variable, group affiliation and treatment indicators. Like the previous model, the dynamic model shows a strong overall fit with an R-squared value of 0.826 and an adjusted R-squared value of 0.815, which means that about 81.5-82.6 % of the variance in the intensity can be explained by the model.

The coefficients for the time variables show that the perceived intensity increases significantly in both time periods. To be more specific, the intensity rises by around 2.15 units in the first period and by about 2.95 units at the second post-test. As for our most crucial independent variable, the interaction terms are both positive and statistically significant. This means that the control group experienced a significantly greater increase in intensity at both post-treatment time points compared to the intervention group. The treatment effect at the first post-test is estimated at about 0.80 units and increases further to 1.35 units at the second post-test. Finally, the body weight variable is positively and significantly associated with intensity. The coefficient of 0.024 suggests that for every additional kilogram of body weight, intensity increases by about 0.02 units, holding all other variables constant. This further supports the inclusion of weight as a meaningful covariate in the model. To summarize the model results, the results confirm the earlier findings that the implementation of the intervention resulted in lower increase in the intervention group compared to the control group – a trend that remains after controlling for body weight.

Table 19.

Regression model 15 shows a dynamic regression model and estimates the impact of the intervention on the intensity from the baseline test to the first post-test and from the first post-test to the second post-test (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 19.

Regression model 15 shows a dynamic regression model and estimates the impact of the intervention on the intensity from the baseline test to the first post-test and from the first post-test to the second post-test (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

3.964 |

0.178 |

22.223 |

0.000 |

[3.610, 4.318] |

| Time (P1) |

2.145 |

0.252 |

8.502 |

0.000 |

[1.644, 2.646] |

| Time (P2) |

2.954 |

0.252 |

11.711 |

0.000 |

[2.454, 3.455] |

| Group (control group) |

-0.892 |

0.256 |

-3.483 |

0.001 |

[-1.399, -0.384] |

| Interaction term (P1) |

0.803 |

0.362 |

2.217 |

0.029 |

[0.084, 1.521] |

| Interaction term (P2) |

1.350 |

0.362 |

-3.730 |

0.000 |

[0.632, 2.069] |

Table 20.

Regression model 16 shows a dynamic regression model and estimates the impact of the intervention and additional covariates from the baseline test to the first post-test and from the first post-test to the second post-test on the perceived intensity (Source: own illustration/Python).

Table 20.

Regression model 16 shows a dynamic regression model and estimates the impact of the intervention and additional covariates from the baseline test to the first post-test and from the first post-test to the second post-test on the perceived intensity (Source: own illustration/Python).

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-value |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| Intercept |

2.094 |

0.767 |

2.730 |

0.008 |

[0.572, 3.616] |

| Time (P1) |

2.145 |

0.246 |

8.726 |

0.000 |

[1.657, 2.633] |

| Time (P2) |

2.954 |

0.246 |

12.018 |

0.000 |

[2.467, 3.442] |

| Group (control group) |

-0.759 |

0.255 |

-2.976 |

0.004 |

[-1.265, -0.253] |

| Interaction term (P1) |

0.803 |

0.353 |

2.276 |

0.025 |

[0.103, 1.503] |

| Interaction term (P2) |

1.350 |

0.353 |

-3.828 |

0.000 |

[0.650, 2.050] |

| Weight |

0.024 |

0.009 |

2.504 |

0.014 |

[0.005, 0.042] |