Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Use of Antibiotics in the Veterinary Sector and in the Livestock Industry

3. The Key Reasons for Using Antibiotics in the Field of Animal Husbandry

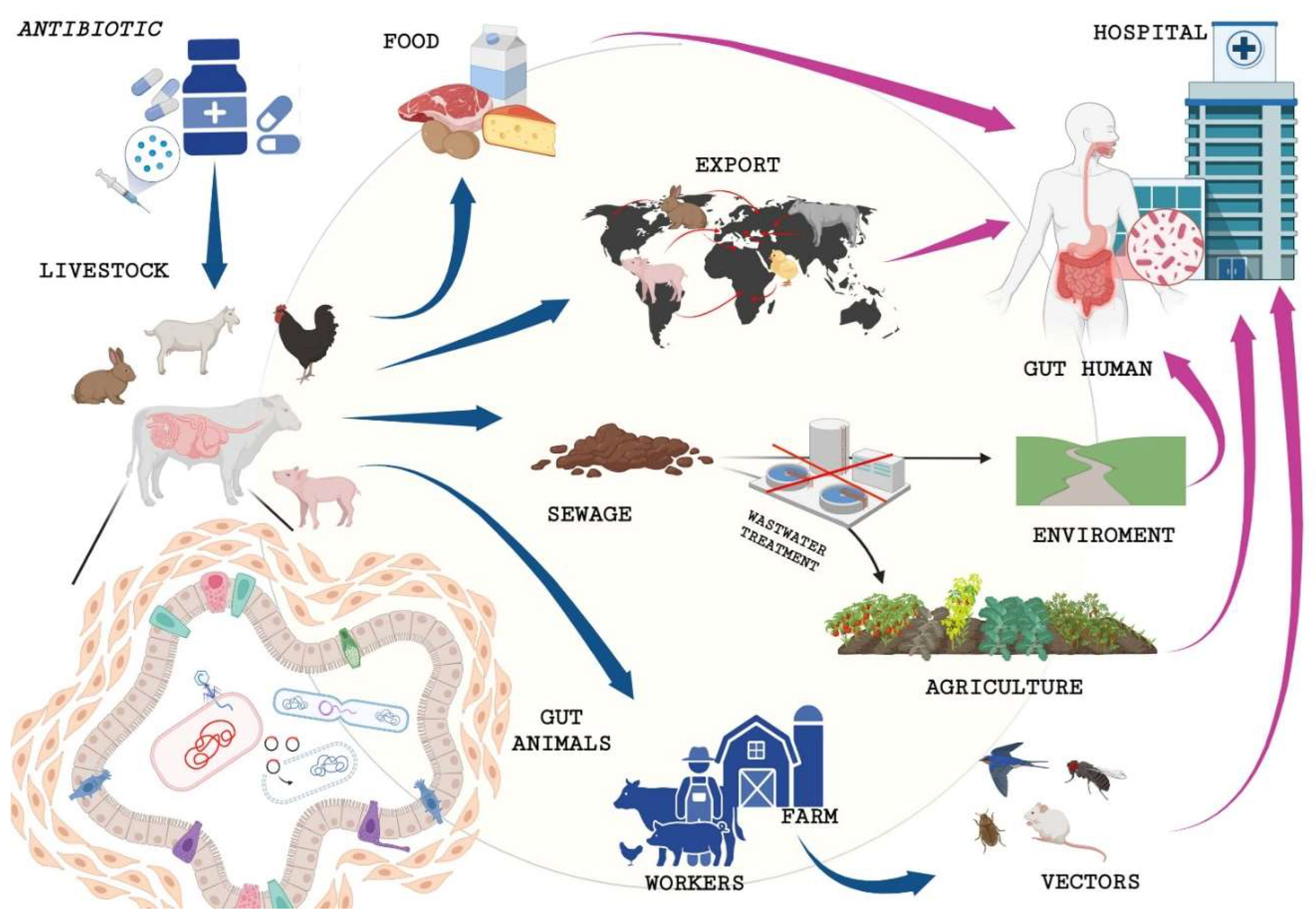

4. How Do Antibiotics in Livestock Impact Antibiotic-Resistant Human Infections?

5. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance

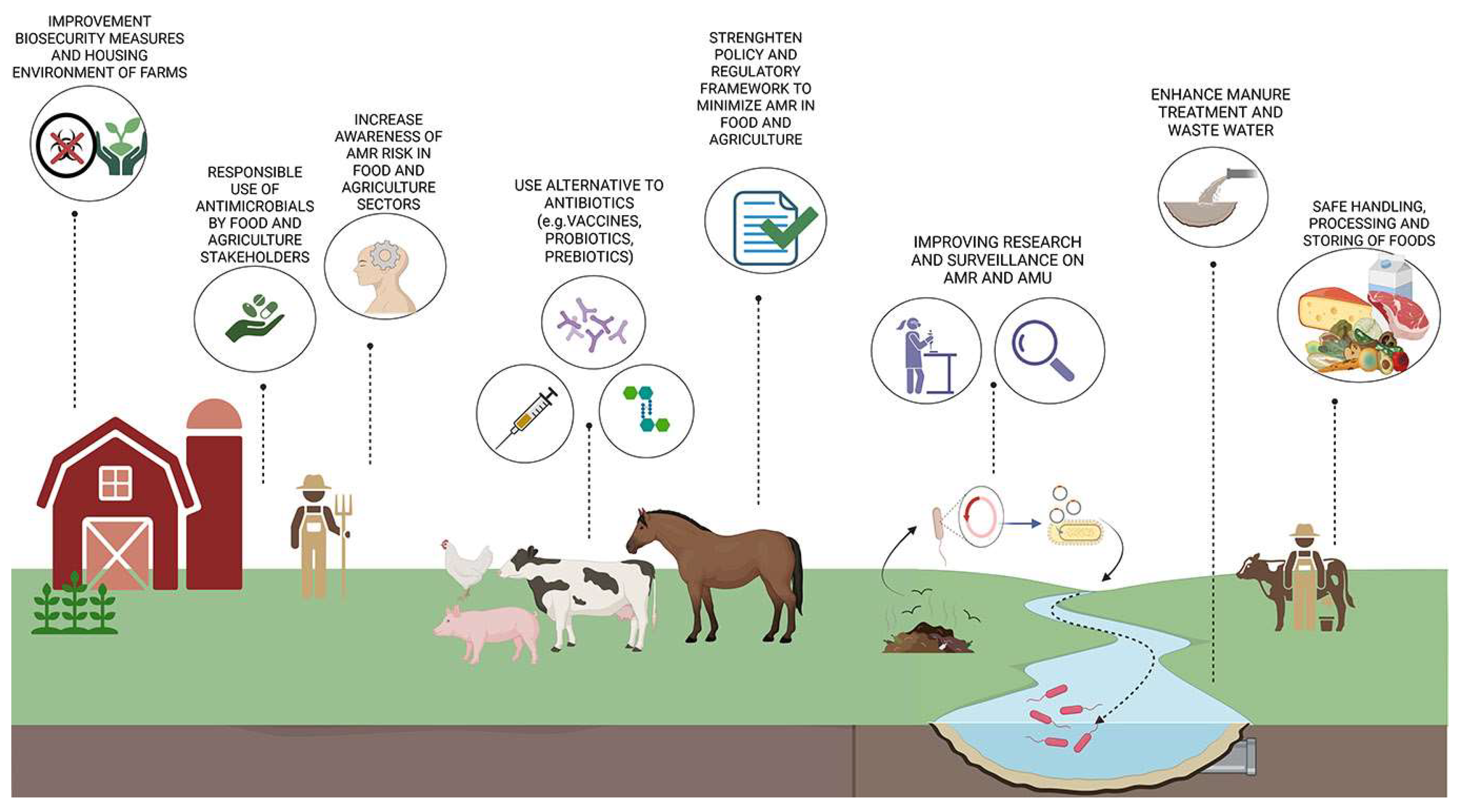

6. Policies and Strategies for Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance from Livestock to Humans

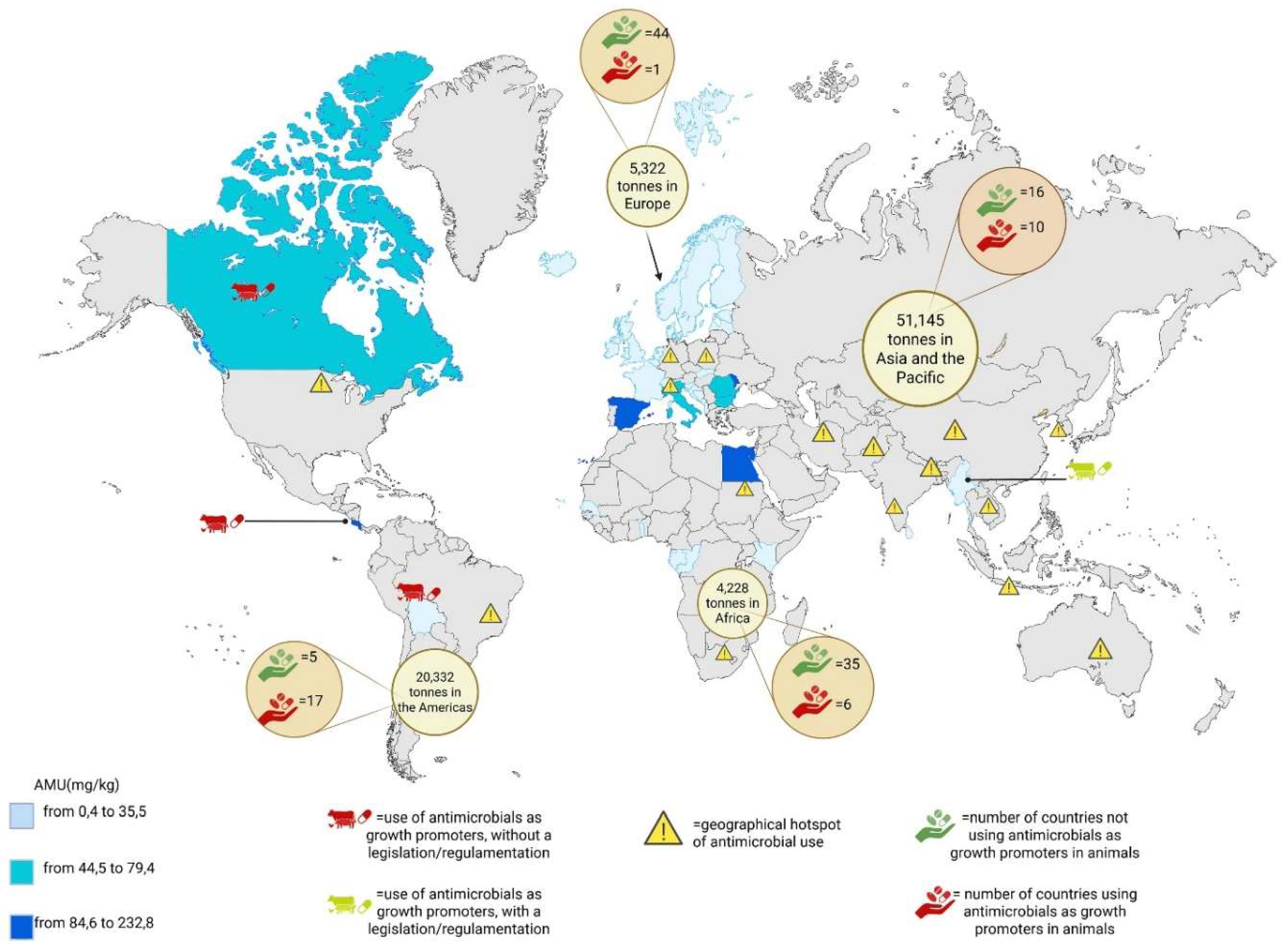

- -

- Asia: eastern China, southern India, Indonesia, central Thailand, the eastern coastline of Vietnam, western South Korea, eastern India and Bangladesh, Pakistan and north-west Iran

- -

- Europe: northern Italy, northern Germany and central Poland

- -

- The Americas: south of Brazil and the Midwest of the USA

- -

- Africa: Nile delta and peri-urban areas of Johannesburg

6.1. Alternative Strategies to Tackle Antimicrobial Resistance

7. Conclusion And Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mancuso, G.; De Gaetano, S.; Midiri, A.; Zummo, S.; Biondo, C. The Challenge of Overcoming Antibiotic Resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: "Attack on Titan". Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedeji, W.A. The Treasure Called Antibiotics. Annals of Ibadan postgraduate medicine 2016, 14, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muteeb, G.; Rehman, M.T.; Shahwan, M.; Aatif, M. Origin of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance, and Their Impacts on Drug Development: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvarajan, R.; Obize, C.; Sibanda, T.; Abia, A.L.K.; Long, H. Evolution and Emergence of Antibiotic Resistance in Given Ecosystems: Possible Strategies for Addressing the Challenge of Antibiotic Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; Flach, C.F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2022, 20, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, P.; Trymers, M.; Chajecka-Wierzchowska, W.; Tkacz, K.; Zadernowska, A.; Modzelewska-Kapitula, M. Antimicrobial Resistance in the Context of Animal Production and Meat Products in Poland-A Critical Review and Future Perspective. Pathogens 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Antunes, W.; Mota, S.; Madureira-Carvalho, A.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Dias da Silva, D. An Overview of the Recent Advances in Antimicrobial Resistance. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance, C. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzo, E.D.G., S.; Midiri, A.; Mancuso, G.; Giovanna, P.; Giuliana, D.; Zummo, S.; Biondo, C. The Antimicrobial Resistance Pandemic Is Here: Implementation Challenges and the Need for the One Health Approach. Hygiene 2024, 297–316. [CrossRef]

- Sirota, M. Should we stop referring to the pandemic of antimicrobial resistance as silent? JAC-antimicrobial resistance 2024, 6, dlae018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porse, A.; Jahn, L.J.; Ellabaan, M.M.H.; Sommer, M.O.A. Dominant resistance and negative epistasis can limit the co-selection of de novo resistance mutations and antibiotic resistance genes. Nature communications 2020, 11, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirwan Khalid Ahmed, S.H., Karzan Qurbani, Radhwan Hussein Ibrahim, Abdulmalik Fareeq, Kochr Ali Mahmood, Mona Gamal Mohamed,. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Kristiansson, E.; Larsson, D.G.J. Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS microbiology reviews 2018, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu, C.D.; Korsten, L.; Okoh, A.I. The incidence of antibiotic resistance within and beyond the agricultural ecosystem: A concern for public health. MicrobiologyOpen 2020, 9, e1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Khurshid, M.; Arshad, M.I.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.; Yasmeen, N.; Shah, T.; Chaudhry, T.H.; Rasool, M.H.; Shahid, A.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance: One Health One World Outlook. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2021, 11, 771510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramod Barathe, K.K., Sagar Reddy, Varsha Shriram, Vinay Kumar. Antibiotic pollution and associated antimicrobial resistance in the environment. Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Sambaza, S.S.; Naicker, N. Contribution of wastewater to antimicrobial resistance: A review article. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance 2023, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, M.C.; Maugeri, A.; Favara, G.; La Mastra, C.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Barchitta, M.; Agodi, A. The Impact of Wastewater on Antimicrobial Resistance: A Scoping Review of Transmission Pathways and Contributing Factors. Antibiotics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Gari, S.R.; Goodson, M.L.; Walsh, C.L.; Dessie, B.K.; Ambelu, A. Fecal Contamination in the Wastewater Irrigation System and its Health Threat to Wastewater-Based Farming Households in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Environmental health insights 2023, 17, 11786302231181307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Nickerson, R.; Zhang, W.; Peng, X.; Shang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Q.; Wen, G.; Cheng, Z. The impacts of animal agriculture on One Health-Bacterial zoonosis, antimicrobial resistance, and beyond. One health 2024, 18, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercelli, C.; Gambino, G.; Amadori, M.; Re, G. Implications of Veterinary Medicine in the comprehension and stewardship of antimicrobial resistance phenomenon. From the origin till nowadays. Veterinary and animal science 2022, 16, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caneschi, A.; Bardhi, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Zaghini, A. The Use of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in Veterinary Medicine, a Complex Phenomenon: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuber, M. Veterinary use and antibiotic resistance. Current opinion in microbiology 2001, 4, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, S.W.; Cha, S.Y.; Jang, H.K.; Wei, B.; Kang, M. Comparative Studies of Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Campylobacter Isolates from Broiler Chickens with and without Use of Enrofloxacin. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verraes, C.; Van Boxstael, S.; Van Meervenne, E.; Van Coillie, E.; Butaye, P.; Catry, B.; de Schaetzen, M.A.; Van Huffel, X.; Imberechts, H.; Dierick, K.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance in the food chain: A review. International journal of environmental research and public health 2013, 10, 2643–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Dien, A.; Le Hello, S.; Bouchier, C.; Weill, F.X. Early transmissible ampicillin resistance in zoonotic Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium in the late 1950s: A retrospective, whole-genome sequencing study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2018, 18, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmerold, I.; van Geijlswijk, I.; Gehring, R. European regulations on the use of antibiotics in veterinary medicine. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences: Official journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 189, 106473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, G.; Cavalie, P.; Pellanne, I.; Chevance, A.; Laval, A.; Millemann, Y.; Colin, P.; Chauvin, C.; Antimicrobial Resistance ad hoc Group of the French Food Safety, A. A comparison of antimicrobial usage in human and veterinary medicine in France from 1999 to 2005. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2008, 62, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granados-Chinchilla, F.; Rodriguez, C. Tetracyclines in Food and Feedingstuffs: From Regulation to Analytical Methods, Bacterial Resistance, and Environmental and Health Implications. Journal of analytical methods in chemistry 2017, 2017, 1315497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butaye, P.; Devriese, L.A.; Haesebrouck, F. Antimicrobial growth promoters used in animal feed: Effects of less well known antibiotics on gram-positive bacteria. Clinical microbiology reviews 2003, 16, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simjee, S.; Ippolito, G. European regulations on prevention use of antimicrobials from january 2022. Brazilian journal of veterinary medicine 2022, 44, e000822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardakani, Z.; Canali, M.; Aragrande, M.; Tomassone, L.; Simoes, M.; Balzani, A.; Beber, C.L. Evaluating the contribution of antimicrobial use in farmed animals to global antimicrobial resistance in humans. One health 2023, 17, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.K.; Levine, U.Y.; Looft, T.; Bandrick, M.; Casey, T.A. Treatment, promotion, commotion: Antibiotic alternatives in food-producing animals. Trends in microbiology 2013, 21, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulchandani, R.; Wang, Y.; Gilbert, M.; Van Boeckel, T.P. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food-producing animals: 2020 to 2030. PLOS global public health 2023, 3, e0001305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarek, A.M.; Dunston, S.; Enahoro, D.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Herrero, M.; Mason-D'Croz, D.; Rich, K.M.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Sulser, T.B.; et al. Income, consumer preferences, and the future of livestock-derived food demand. Global environmental change: Human and policy dimensions 2021, 70, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, E.; Gugsa, G.; Ahmed, M. Review on Major Food-Borne Zoonotic Bacterial Pathogens. Journal of tropical medicine 2020, 2020, 4674235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, P.; Pelligand, L.; Giraud, E.; Toutain, P.L. A history of antimicrobial drugs in animals: Evolution and revolution. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2021, 44, 137–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosain, M.Z.; Kabir, S.M.L.; Kamal, M.M. Antimicrobial uses for livestock production in developing countries. Veterinary world 2021, 14, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.J.; Wellington, M.; Shah, R.M.; Ferreira, M.J. Antibiotic Stewardship in Food-producing Animals: Challenges, Progress, and Opportunities. Clinical therapeutics 2020, 42, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, J.L.; Sweeney, M.T.; Lubbers, B.V. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Bacteria of Veterinary Origin. Microbiology spectrum 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gens, K.D.; Singer, R.S.; Dilworth, T.J.; Heil, E.L.; Beaudoin, A.L. Antimicrobials in Animal Agriculture in the United States: A Multidisciplinary Overview of Regulation and Utilization to Foster Collaboration: On Behalf Of the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Open forum infectious diseases 2022, 9, ofac542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenu, K.; McIntyre, K.M.; Moje, N.; Knight-Jones, T.; Rushton, J.; Grace, D. Approaches for disease prioritization and decision-making in animal health, 2000-2021: A structured scoping review. Frontiers in veterinary science 2023, 10, 1231711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odey, T.O.J.; Tanimowo, W.O.; Afolabi, K.O.; Jahid, I.K.; Reuben, R.C. Antimicrobial use and resistance in food animal production: Food safety and associated concerns in Sub-Saharan Africa. International microbiology: The official journal of the Spanish Society for Microbiology 2024, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, S.; Shrestha, P.; Adhikari, B. Antimicrobial use in food animals and human health: Time to implement 'One Health' approach. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control 2020, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridou Oxinou, D.; Lamnisos, D.; Filippou, C.; Spernovasilis, N.; Tsioutis, C. Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in Food-Producing Animals: Cross-Sectional Study on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Veterinarians and Operators of Establishments in the Republic of Cyprus. Antibiotics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimera, Z.I.; Mshana, S.E.; Rweyemamu, M.M.; Mboera, L.E.G.; Matee, M.I.N. Antimicrobial use and resistance in food-producing animals and the environment: An African perspective. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control 2020, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.W.; Bergeron, G.; Bourassa, M.W.; Dickson, J.; Gomes, F.; Howe, A.; Kahn, L.H.; Morley, P.S.; Scott, H.M.; Simjee, S.; et al. Complexities in understanding antimicrobial resistance across domesticated animal, human, and environmental systems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2019, 1441, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argudin, M.A.; Deplano, A.; Meghraoui, A.; Dodemont, M.; Heinrichs, A.; Denis, O.; Nonhoff, C.; Roisin, S. Bacteria from Animals as a Pool of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. Antibiotics 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marimon, J.M.; Gomariz, M.; Zigorraga, C.; Cilla, G.; Perez-Trallero, E. Increasing prevalence of quinolone resistance in human nontyphoid Salmonella enterica isolates obtained in Spain from 1981 to 2003. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2004, 48, 3789–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandujano-Hernandez, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, A.V.; Paz-Gonzalez, A.D.; Herrera-Mayorga, V.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.; Lara-Ramirez, E.E.; Vazquez, K.; de Jesus de Luna-Santillana, E.; Bocanegra-Garcia, V.; Rivera, G. The Global Rise of ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli in the Livestock Sector: A Five-Year Overview. Animals: An open access journal from MDPI 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorum, M.; Holstad, G.; Lillehaug, A.; Kruse, H. Prevalence of vancomycin resistant enterococci on poultry farms established after the ban of avoparcin. Avian diseases 2004, 48, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simm, R.; Slettemeas, J.S.; Norstrom, M.; Dean, K.R.; Kaldhusdal, M.; Urdahl, A.M. Significant reduction of vancomycin resistant E. faecium in the Norwegian broiler population coincided with measures taken by the broiler industry to reduce antimicrobial resistant bacteria. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernli, D.; Harbarth, S.; Levrat, N.; Pittet, D. A 'whole of United Nations approach' to tackle antimicrobial resistance? A mapping of the mandate and activities of international organisations. BMJ global health 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.A.A.; Rahman, S.; Cohall, D.; Bharatha, A.; Singh, K.; Haque, M.; Gittens-St Hilaire, M. Antimicrobial Stewardship: Fighting Antimicrobial Resistance and Protecting Global Public Health. Infection and drug resistance 2020, 13, 4713–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Alam Tumpa, M.A.; Zehravi, M.; Sarker, M.T.; Yamin, M.; Islam, M.R.; Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Ahmed, M.; Ramproshad, S.; Mondal, B.; et al. An Overview of Antimicrobial Stewardship Optimization: The Use of Antibiotics in Humans and Animals to Prevent Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, R.; Saavedra, M.J.; Almeida, G. A Decade of Antimicrobial Resistance in Human and Animal Campylobacter spp. Isolates. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.; Silva, V.; Dapkevicius, M.L.E.; Canica, M.; Tejedor-Junco, M.T.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Escherichia coli as Commensal and Pathogenic Bacteria Among Food-Producing Animals: Health Implications of Extended Spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) Production. Animals: An open access journal from MDPI 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelaar, A.H.; Kirk, M.D.; Torgerson, P.R.; Gibb, H.J.; Hald, T.; Lake, R.J.; Praet, N.; Bellinger, D.C.; de Silva, N.R.; Gargouri, N.; et al. World Health Organization Global Estimates and Regional Comparisons of the Burden of Foodborne Disease in 2010. PLoS medicine 2015, 12, e1001923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbehiry, A.; Abalkhail, A.; Marzouk, E.; Elmanssury, A.E.; Almuzaini, A.M.; Alfheeaid, H.; Alshahrani, M.T.; Huraysh, N.; Ibrahem, M.; Alzaben, F.; et al. An Overview of the Public Health Challenges in Diagnosing and Controlling Human Foodborne Pathogens. Vaccines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van, T.T.H.; Yidana, Z.; Smooker, P.M.; Coloe, P.J. Antibiotic use in food animals worldwide, with a focus on Africa: Pluses and minuses. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance 2020, 20, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyi-Loh, C.; Mamphweli, S.; Meyer, E.; Okoh, A. Antibiotic Use in Agriculture and Its Consequential Resistance in Environmental Sources: Potential Public Health Implications. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Doo, H.; Keum, G.B.; Kim, E.S.; Kwak, J.; Ryu, S.; Choi, Y.; Kang, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, N.R.; et al. Antibiotic resistance in livestock, environment and humans: One Health perspective. Journal of animal science and technology 2024, 66, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bava, R.; Castagna, F.; Lupia, C.; Poerio, G.; Liguori, G.; Lombardi, R.; Naturale, M.D.; Mercuri, C.; Bulotta, R.M.; Britti, D.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock: A Serious Threat to Public Health. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidara-Kane, A.; Angulo, F.J.; Conly, J.M.; Minato, Y.; Silbergeld, E.K.; McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J.; Group, W.H.O.G.D. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food-producing animals. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control 2018, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, T.S.; Barnett-Itzhaki, Z.; Berman, T.; Marom, E. Antimicrobial resistance in food-producing animals: Towards implementing a one health based national action plan in Israel. Israel journal of health policy research 2023, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.M.; Acuff, G.; Bergeron, G.; Bourassa, M.W.; Gill, J.; Graham, D.W.; Kahn, L.H.; Morley, P.S.; Salois, M.J.; Simjee, S.; et al. Critically important antibiotics: Criteria and approaches for measuring and reducing their use in food animal agriculture. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2019, 1441, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, C.; Grohmann, E. Horizontal Gene Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Biofilms. Antibiotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgano, M.; Pellegrini, F.; Catalano, E.; Capozzi, L.; Del Sambro, L.; Sposato, A.; Lucente, M.S.; Vasinioti, V.I.; Catella, C.; Odigie, A.E.; et al. Acquired Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics and Resistance Genes: From Past to Future. Antibiotics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, A.; Matthias, T.; Aminov, R. Potential Effects of Horizontal Gene Exchange in the Human Gut. Frontiers in immunology 2017, 8, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimpeteanu, O.M.; Pogurschi, E.N.; Popa, D.C.; Dragomir, N.; Dragotoiu, T.; Mihai, O.D.; Petcu, C.D. Antibiotic Use in Livestock and Residues in Food-A Public Health Threat: A Review. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, H. The microbiota: A crucial mediator in gut homeostasis and colonization resistance. Frontiers in microbiology 2024, 15, 1417864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, B.J.; Wegh, R.S.; Memelink, J.; Zuidema, T.; Stolker, L.A. The analysis of animal faeces as a tool to monitor antibiotic usage. Talanta 2015, 132, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Jaiswal, A.; Kumar, D.; Pandit, R.; Blake, D.; Tomley, F.; Joshi, M.; Joshi, C.G.; Dubey, S.K. Whole genome sequencing revealed high occurrence of antimicrobial resistance genes in bacteria isolated from poultry manure. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2025, 65, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, P.; Pokrant, E.; Yevenes, K.; Maddaleno, A.; Flores, A.; Vargas, M.B.; Trincado, L.; Maturana, M.; Lapierre, L.; Cornejo, J. Antimicrobial Residues in Poultry Litter: Assessing the Association of Antimicrobial Persistence with Resistant Escherichia coli Strains. Antibiotics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yevenes, K.; Pokrant, E.; Trincado, L.; Lapierre, L.; Galarce, N.; Martin, B.S.; Maddaleno, A.; Hidalgo, H.; Cornejo, J. Detection of Antimicrobial Residues in Poultry Litter: Monitoring a Risk through a Selective and Sensitive HPLC-MS/MS Method. Animals: An open access journal from MDPI 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazards, E.P.o.B.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordonez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; et al. Role played by the environment in the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) through the food chain. EFSA journal. European Food Safety Authority 2021, 19, e06651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W.; Chaukura, N.; Muisa-Zikali, N.; Teta, C.; Musvuugwa, T.; Rzymski, P.; Abia, A.L.K. Insects, Rodents, and Pets as Reservoirs, Vectors, and Sentinels of Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouz, N.; Pangesti, K.N.A.; Yasir, M.; Al-Malki, A.L.; Azhar, E.I.; Hill-Cawthorne, G.A.; Abd El Ghany, M. The Contribution of Wastewater to the Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance in the Environment: Implications of Mass Gathering Settings. Tropical medicine and infectious disease 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, K.E.; Laing, G.; McMahon, B.J.; Fanning, S.; Stekel, D.J.; Pahl, O.; Coyne, L.; Latham, S.M.; McIntyre, K.M. The need for One Health systems-thinking approaches to understand multiscale dissemination of antimicrobial resistance. The Lancet. Planetary health 2024, 8, e124–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Kong, L.; Gao, H.; Cheng, X.; Wang, X. A Review of Current Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics in Food Animals. Frontiers in microbiology 2022, 13, 822689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, M.; Birk, T.; Hansen, L.T. Prevalence and Transmission of Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporin (ESC) Resistance Genes in Escherichia coli Isolated from Poultry Production Systems and Slaughterhouses in Denmark. Antibiotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety, A.; European Centre for Disease, P.; Control. The European Union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2021-2022. EFSA journal. European Food Safety Authority 2024, 22, e8583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J. Antimicrobial Resistance: A One Health Perspective. Microbiology spectrum 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklemariam, A.D.; Al-Hindi, R.R.; Albiheyri, R.S.; Alharbi, M.G.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Filimban, A.A.R.; Al Mutiri, A.S.; Al-Alyani, A.M.; Alseghayer, M.S.; Almaneea, A.M.; et al. Human Salmonellosis: A Continuous Global Threat in the Farm-to-Fork Food Safety Continuum. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahoy, M.J.; Shah, H.J.; Weller, D.L.; Ray, L.C.; Smith, K.; McGuire, S.; Trevejo, R.T.; Scallan Walter, E.; Wymore, K.; Rissman, T.; et al. Preliminary Incidence and Trends of Infections Caused by Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food - Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2022. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2023, 72, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzand, F.; Kim, A.H.M.; Chambers, T.; Grout, L.; Baker, M.G.; Hales, S. Examining campylobacteriosis disease notification rates: Association with water supply characteristics. Environmental research 2025, 271, 121064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, M.; Simon, S.; Meinen, A.; Trost, E.; Banerji, S.; Pfeifer, Y.; Flieger, A. Third generation cephalosporin resistance in clinical non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica in Germany and emergence of bla(CTX-M)-harbouring pESI plasmids. Microbial genomics 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, M.; Murray, G.G.R.; Ba, X.; Wood, R.; Holmes, M.A.; Weinert, L.A. Stable antibiotic resistance and rapid human adaptation in livestock-associated MRSA. eLife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuny, C.; Wieler, L.H.; Witte, W. Livestock-Associated MRSA: The Impact on Humans. Antibiotics 2015, 4, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.; Harant, A.; Fernandes, G.; Mwamelo, A.J.; Hein, W.; Dekker, D.; Sridhar, D. Measuring the global response to antimicrobial resistance, 2020–2021: A systematic governance analysis of 114 countries. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2023, 23, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerum, A.M.; Heuer, O.E.; Emborg, H.D.; Bagger-Skjot, L.; Jensen, V.F.; Rogues, A.M.; Skov, R.L.; Agerso, Y.; Brandt, C.T.; Seyfarth, A.M.; et al. Danish integrated antimicrobial resistance monitoring and research program. Emerging infectious diseases 2007, 13, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Feye, K.M.; Shi, Z.; Pavlidis, H.O.; Kogut, M.; A, J.A.; Ricke, S.C. A Historical Review on Antibiotic Resistance of Foodborne Campylobacter. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10, 1509. [CrossRef]

- Mader, R.; Jarrige, N.; Haenni, M.; Bourely, C.; Madec, J.Y.; Amat, J.P.; Eu, J. OASIS evaluation of the French surveillance network for antimicrobial resistance in diseased animals (RESAPATH): Success factors underpinning a well-performing voluntary system. Epidemiology and infection 2021, 149, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutil, L.; Irwin, R.; Finley, R.; Ng, L.K.; Avery, B.; Boerlin, P.; Bourgault, A.M.; Cole, L.; Daignault, D.; Desruisseau, A.; et al. Ceftiofur resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg from chicken meat and humans, Canada. Emerging infectious diseases 2010, 16, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Paruch, L.; Chen, X.; van Eerde, A.; Skomedal, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu Clarke, J. Antibiotic Application and Resistance in Swine Production in China: Current Situation and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in veterinary science 2019, 6, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Li, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, H.; Tang, Y. Withdrawal of antibiotic growth promoters in China and its impact on the foodborne pathogen Campylobacter coli of swine origin. Frontiers in microbiology 2022, 13, 1004725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Han, Z.; Song, K.; Zhen, T. Antibiotic Consumption Trends in China: Evidence From Six-Year Surveillance Sales Records in Shandong Province. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiseo, K.; Huber, L.; Gilbert, M.; Robinson, T.P.; Van Boeckel, T.P. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food Animals from 2017 to 2030. Antibiotics 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grave, K.; Torren-Edo, J.; Muller, A.; Greko, C.; Moulin, G.; Mackay, D.; Group, E. Variations in the sales and sales patterns of veterinary antimicrobial agents in 25 European countries. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2014, 69, 2284–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idoko-Akoh, A.; Goldhill, D.H.; Sheppard, C.M.; Bialy, D.; Quantrill, J.L.; Sukhova, K.; Brown, J.C.; Richardson, S.; Campbell, C.; Taylor, L.; et al. Creating resistance to avian influenza infection through genome editing of the ANP32 gene family. Nature communications 2023, 14, 6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, V.; Roviello, G.N. The Potential Role of Vaccines in Preventing Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR): An Update and Future Perspectives. Vaccines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, T.R.; Lillehoj, H.; Chuanchuen, R.; Gay, C.G. Alternatives to Antibiotics: A Symposium on the Challenges and Solutions for Animal Health and Production. Antibiotics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, A.; Gilbert, M.; Corsaut, L.; Gaudreau, A.; Obradovic, M.R.; Cloutier, S.; Frenette, M.C.; Surprenant, C.; Lacouture, S.; Arnal, J.L.; et al. Immune response induced by a Streptococcus suis multi-serotype autogenous vaccine used in sows to protect post-weaned piglets. Veterinary research 2024, 55, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Hao, Y.; Feng, H.; Shu, J.; He, Y. Research progress on Haemophilus parasuis vaccines. Frontiers in veterinary science 2025, 12, 1492144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.P.; Vrba, V.; Xia, D.; Jatau, I.D.; Spiro, S.; Nolan, M.J.; Underwood, G.; Tomley, F.M. Genetic and biological characterisation of three cryptic Eimeria operational taxonomic units that infect chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus). International journal for parasitology 2021, 51, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petro-Turnquist, E.; Pekarek, M.J.; Weaver, E.A. Swine influenza A virus: Challenges and novel vaccine strategies. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2024, 14, 1336013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelzer, K.; Bielke, L.; Blake, D.P.; Cox, E.; Cutting, S.M.; Devriendt, B.; Erlacher-Vindel, E.; Goossens, E.; Karaca, K.; Lemiere, S.; et al. Vaccines as alternatives to antibiotics for food producing animals. Part 2: New approaches and potential solutions. Veterinary research 2018, 49, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Yu, B.; Degroote, J.; Spranghers, T.; Van Noten, N.; Majdeddin, M.; Van Poucke, M.; Peelman, L.; De Vrieze, J.; Boon, N.; et al. Antibiotic affects the gut microbiota composition and expression of genes related to lipid metabolism and myofiber types in skeletal muscle of piglets. BMC veterinary research 2020, 16, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, B.P.; Lisboa, J.A.N.; Bessegatto, J.A.; Montemor, C.H.; Paulino, L.R.; Alfieri, A.A.; Weese, J.S.; Costa, M.C. Impact of virginiamycin on the ruminal microbiota of feedlot cattle. Canadian journal of veterinary research = Revue canadienne de recherche veterinaire 2024, 88, 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- El-Fateh, M.; Bilal, M.; Zhao, X. Effect of antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) on feed conversion ratio (FCR) of broiler chickens: A meta-analysis. Poultry science 2024, 103, 104472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Ghanbari, M.; May, A.; Abeel, T. Effects of antibiotic growth promoter and its natural alternative on poultry cecum ecosystem: An integrated analysis of gut microbiota and host expression. Frontiers in microbiology 2024, 15, 1492270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, A.E.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. The microbial food revolution. Nature communications 2023, 14, 2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhi, K.S.; Arif, M.; Rehman, A.U.; Faizan, M.; Almohmadi, N.H.; Youssef, I.M.; Swelum, A.A.; Suliman, G.M.; Tharwat, M.; Ebrahim, A.; et al. Growth performance of broiler chickens fed diets supplemented with amylase and protease enzymes individually or combined. Open veterinary journal 2023, 13, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Shehzad, A.; Niazi, S.; Zahid, A.; Ashraf, W.; Iqbal, M.W.; Rehman, A.; Riaz, T.; Aadil, R.M.; Khan, I.M.; et al. Probiotics: Mechanism of action, health benefits and their application in food industries. Frontiers in microbiology 2023, 14, 1216674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazziotta, C.; Tognon, M.; Martini, F.; Torreggiani, E.; Rotondo, J.C. Probiotics Mechanism of Action on Immune Cells and Beneficial Effects on Human Health. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davani-Davari, D.; Negahdaripour, M.; Karimzadeh, I.; Seifan, M.; Mohkam, M.; Masoumi, S.J.; Berenjian, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Sharma, S. Role of alternatives to antibiotics in mitigating the antimicrobial resistance crisis. The Indian journal of medical research 2022, 156, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klous, G.; Huss, A.; Heederik, D.J.J.; Coutinho, R.A. Human-livestock contacts and their relationship to transmission of zoonotic pathogens, a systematic review of literature. One health 2016, 2, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makovska, I.; Chantziaras, I.; Caekebeke, N.; Dhaka, P.; Dewulf, J. Assessment of Cleaning and Disinfection Practices on Pig Farms across Ten European Countries. Animals: An open access journal from MDPI 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiche, T.; Hageskal, G.; Mares, M.; Hoel, S.; Tondervik, A.; Heggeset, T.M.B.; Haugen, T.; Sperstad, S.B.; Troen, H.H.; Bjorkoy, S.; et al. Shifts in surface microbiota after cleaning and disinfection in broiler processing plants: Incomplete biofilm eradication revealed by robotic high-throughput screening. Applied and environmental microbiology 2025, 91, e0240124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawa, B.; Singh, S.; Chakma, S.; Kishor, R.; Stalsby Lundborg, C.; Diwan, V. Development of novel biochar adsorbent using agricultural waste biomass for enhanced removal of ciprofloxacin from water: Insights into the isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamic analysis. Chemosphere 2025, 375, 144252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadeer, A.; Khan, A.; Khan, N.M.; Wajid, A.; Ullah, K.; Skalickova, S.; Chilala, P.; Slama, P.; Horky, P.; Alqahtani, M.S.; et al. Use of nanotechnology-based nanomaterial as a substitute for antibiotics in monogastric animals. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.; Semedo-Lemsaddek, T.; Cunha, E.; Tavares, L.; Oliveira, M. Antimicrobial Drug Resistance in Poultry Production: Current Status and Innovative Strategies for Bacterial Control. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, J.T.; Waddad, A.Y.; Albericio, F.; de la Torre, B.G. Antimicrobial Peptide Synergies for Fighting Infectious Diseases. Advanced science 2023, 10, e2300472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Song, Q.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, S.; Yu, H.; Ding, X.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, J. Effect of Antimicrobial Peptide Microcin J25 on Growth Performance, Immune Regulation, and Intestinal Microbiota in Broiler Chickens Challenged with Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Animals: An open access journal from MDPI 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Trinchera, M.; Midiri, A.; Zummo, S.; Vitale, G.; Biondo, C. Novel Antimicrobial Approaches to Combat Bacterial Biofilms Associated with Urinary Tract Infections. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlec, A.F.; Corciova, A.; Boev, M.; Batir-Marin, D.; Mircea, C.; Cioanca, O.; Danila, G.; Danila, M.; Bucur, A.F.; Hancianu, M. Current Overview of Metal Nanoparticles' Synthesis, Characterization, and Biomedical Applications, with a Focus on Silver and Gold Nanoparticles. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, F.; Ghaedi, A.; Fooladfar, Z.; Bazrgar, A. Recent advance on nanoparticles or nanomaterials with anti-multidrug resistant bacteria and anti-bacterial biofilm properties: A systematic review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchuk, O.; Levchenko, A.; da Silva Mesquita, R.; Danchuk, V.; Cengiz, S.; Cengiz, M.; Grafov, A. Meeting Contemporary Challenges: Development of Nanomaterials for Veterinary Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS | SPECIES | USE | MODE OF ACTION | BACTERIAL RESISTANCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AMINOCOUMARIN Novobiocin |

Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Ovine, Fish |

Novobiocin is for treating mastitis. It is currently only used on animals. |

Novobiocin is a narrow-spectrum antimicrobial. It is bacteriostatic, but may be bactericidal at higher concentrations. It is active mostly against gram-positive bacteria, but also against a few gram-negative bacteria. Can be used on association, for synergistic effect, with tetracyclines. |

Many species of bacteria can develop resistance to novobiocin. |

|

AMINOCYCLITOL Spectinomycin |

Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine |

Used for respiratory infections in cattle and enteric infections in multiple species. |

Spectinomycin belongs to the class of aminocyclic antibiotics. It has been demonstrated to inhibit bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 30S subunit of the ribosome, thereby causing incorrect reading of the genetic code by tRNA. Spectinomycin exerts bacteriostatic activity. | The resistance of the antibiotic spectinomycin has been linked to the aadA gene, and this association was found to be plasmid-mediated. Its precise location was determined to be within a variant of the integrative and conjugative element ICE Mh1, which encodes an enzyme termed aminoglycoside 3'-adenylate transferase. |

|

AMINOGLYCOSIDES Dihydrostreptomycin Streptomycin |

Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Bee, Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine |

The broad spectrum of applications renders aminoglycosides a pivotal component of veterinary medicine. Aminoglycosides have a broad spectrum of applications in veterinary medicine, including the treatment of: -septicaemias -digestive infections -respiratory infections -urinary diseases Gentamicin is indicated for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections, with few alternatives. Apramycin and Fortimycin are currently only used in animals. |

Aminoglycosides have been demonstrated to be effective against rapidly multiplying organisms. The amino groups contribute to the cationic nature of this class of antimicrobials, which is important in mediating the transport across the cytoplasmic membrane and binding with specific anionic sites on LPS. The internalization process is followed by irreversible binding to multiple sites of the 30S ribosomal subunit, as well as the 50S ribosomal subunit, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis. Nevertheless, at low concentrations, all aminoglycosides may be bacteriostatic activity. |

The mechanisms of resistance encompass the process of enzymatic modification of aminoglycosides, which may be either plasmid-encoded or chromosomally mediated. Enzymes have been observed in both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. To date, 50 enzymes have been identified, which can be categorized into three major classes: • Acetyltransferases • Nucleotidyltransferases • Phosphotransferases Chemical modification stabilizes the drug, decreasing susceptibility to enzymatic destruction. For instance, amikacin is produced through the chemical modification of kanamycin, which exhibits enhanced resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis. Other resistance mechanisms include higher levels of calcium and magnesium ions, which stop cationic drugs from binding to bacteria. |

|

AMINOGLYCOSIDES + 2 DEOXYSTREPTAMINE Amikacin Apramycin Fortimycin *Framycetin Gentamicin Kanamycin *Neomycin Paromomycin Tobramycin |

Equine Avian, Bovine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Bovine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Bovine, Caprine, Ovine Avian, Bovine, Camel, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Equine, Fish, Swine Bee, Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Ovine, Rabbit, Swine Equine |

|||

|

AMPHENICOLS Florfenicol Thiamphenicol |

Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Ovine, Fish, Swine |

Phenicol drugs have a wide range of uses, making them very important in veterinary medicine, especially for treating fish diseases. They are also used to treat respiratory infections in cattle, pigs and poultry, with florfenicol used to treat pasteurellosis in these animals. |

This antibiotic is bacteriostatic. It binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit, stopping protein production in bacteria, and may be bactericidal against S. pseudopneumoniae |

Research has identified florfenicol resistance on mobile genetic elements. Florfenicol, a derivative of chloramphenicol, has been found to be resistant to certain chloramphenicol resistance genes. The primary mechanism of resistance to chloramphenicol is enzymatic inactivation. |

|

ANSAMYCIN – RIFAMYCINS Rifampicin Rifaximin |

Equine Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine |

This antimicrobial class is authorized in a limited number of countries and for a restricted number of indications (mastitis), and there are few alternatives. Rifampicin is employed in the treatment of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. |

The antibiotic is classed as an extended-spectrum antibiotic. Rifamycins inhibit the synthesis of RNA in microrganisms by binding to DNA-dependent RNA polymerase subunits. They effectively penetrate tissues and cells, making them particularly efficacious in the treatment of intracellular organisms. |

The development of antimicrobial resistance, even when administered in combination with other antimicrobials, is a key concern. |

|

BICYCLOMYCIN Bicozamycin |

Bovine, Fish, Swine |

Bicyclomycin has been included in the list of pharmaceuticals used in the treatment of digestive and respiratory diseases in cattle. | NA | NA |

|

CEPHALOSPORINS FIRST GENERATION Cefacetrile Cefalexin Cefalonium Cefalotin Cefapyrin Cefazolin |

Bovine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Ovine, Swine Bovine, Caprine, Ovine Equine Bovine Bovine, Caprine, Ovine |

Cephalosporins are employed in the treatment of the following conditions: • Septicemia • Respiratory infections • Mastitis |

Cephalosporins are categorized within the class of beta-lactam antibiotics. These antibiotics disrupt the process of bacterial cell wall formation by interacting with a group of proteins known as the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). These transpeptidase enzymes are responsible for the formation of cross-links between peptidoglycan strands. It is noteworthy that the antibiotic activity of beta-lactams is confined to organisms in the log phase of growth or during active multiplication. Consequently, static bacteria are unaffected and may persist. However, at appropriate concentrations, they are bactericidal to most bacteria. Cephalosporins are weak acids that are derived from 7-minocephalosporanic acid. Modifications at this nucleus, in addition to substitutions on the side chains, result in differences among cephalosporins with respect to their antibacterial spectra, beta-lactamase sensitivities and pharmacokinetics. |

The mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance are multifactorial and common to all beta-lactam antibiotics. These mechanisms may comprise one or more combinations of different types of resistance, including: • modification of the drug target, via alterations to the PBPs (of which there are at least nine different types on the cell wall, with differences in PBP targets); • downregulation of porins, with reduction in cell permeability; • increased expression of efflux pumps; • production of degrading enzymes (cephalosporinase). The beta-lactam nucleus of the cephalosporins is susceptible to hydrolysis by beta-lactamase enzymes. This reaction, in turn, is known to result in the cleavage of the beta-lactam nucleus. This, in turn, leads to the inactivation of the beta-lactam, which, ultimately, results in the failure of the drug to bind to their target PBPs. It is estimated that more than 800 beta-lactamases have been documented, a figure which reflects the mounting pressure resulting from the increased use of beta-lactam. Inhibitors of beta-lactamases, such as clavulanic acid and sulbactam, have been introduced to inhibit beta-lactam degradation. |

|

CEPHALOSPORINS SECOND GENERATION Cefuroxime |

Bovine |

|||

|

CEPHALOSPORINS THIRD GENERATION Cefoperazone Ceftiofur Ceftriaxone |

Bovine, Caprine, Ovine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Bovine, Ovine, Swine |

The wide range of applications make cephalosporin third and fourth generation extremely important for veterinary medicine. These cephalosporins are employed in the management of: -septicaemias -respiratory infections -mastitis Alternatives are characterized by limited efficacy, either due to inadequate spectrum or the presence of antimicrobial resistance. |

||

|

CEPHALOSPORINS FOURTH GENERATION Cefquinome |

Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine |

|||

|

FUSIDANE Fusidic acid |

Bovine, Equine |

Fusidic acid is employed in the treatment of ophthalmic diseases in cattle and horses. |

Fusidic acid has been demonstrated to interfere with the function of elongation factor and to inhibit protein synthesis at the 50S subunit of the ribosome. It is noteworthy that the action of fusidic acid is bacteriostatic against gram-positive organisms, and bactericidal against Staphylococcus aureus. |

Fusidic acid resistance can develop quickly. |

|

IONOPHORES Lasalocid Maduramycin Monensin Narasin Salinomycin Semduramicin |

Avian, Bovine, Rabbit, Ovine Avian Bee, Avian, Bovine, Caprine Avian, Bovine Avian, Rabbit, Bovine, Swine Avian |

Ionophores are of critical importance to the health of animals, particularly in the context of controlling intestinal parasitic coccidiosis (Eimeria spp.), a condition for which there are limited treatment options when alternative remedies are unavailable. In the context of poultry, ionophores play a pivotal role. It is important to note that the use of ionophores is currently limited to animal husbandry. |

Ionophores are lipid-soluble molecules that can bind and transport ions across cell membranes. Inside the cell, ionophores change the concentration of different types of ions, including calcium, potassium, hydrogen and sodium. This can block protein transport, reduce metabolic activity and kill the organism. |

Resistance to ionophores is probably adaptive, not due to mutation or gene acquisition. |

|

LINCOSAMIDES Lincomycin Pirlimycin |

Bee, Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Ovine, Fish, Swine Bovine, Swine |

In the context of treating swine, lincosamides have been found to be essential for treating the following conditions: • Mycoplasmal pneumonia • infectious arthritis • haemorrhagic enteritis |

Lincosamides are antibiotics that exclusively bind to the 50S subunit of bacterial ribosomes, suppressing protein synthesis via inhibition of peptidyl transferases. The antibacterial potency of lincosamides varies by concentration, being bacteriostatic at lower concentrations and bactericidal at higher concentrations. Lincosamides are also contingent upon bacterial load and species. |

Resistance to lincosamides develops gradually, due to plasmid or chromosomal methylation of the ribosomal subunit. Other mechanisms include increased efflux pump activation and drug destruction. |

|

MACROLIDES 14- MEMBERED RING Erythromycin Oleandomycin |

Bee, Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Bovine |

The extensive range of applications of macrolides renders them of significant importance in the domain of veterinary medicine. The following conditions are treated with macrolides: -Mycoplasma infections in pigs and poultry; -haemorrhagic digestive disease in pigs (Lawsonia intracellularis); -liver abscesses (Fusobacterium necrophorum) in cattle. In all these conditions, macrolides represent the only effective treatment available. This class of antibiotics is also used for respiratory infections in cattle. |

There are various classes of macrolides distinguished by the size of their ring. All classes of macrolides share a common mechanism that inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit, which is similar to how phenicol antibiotics work. These antibiotics block the translocation process that helps the peptide chain grow, which is essential for life. Macrolides are classified as bacteriostatic drugs, but at high concentrations they can be bactericidal. | Macrolide resistance falls into three main categories: intrinsic, acquired, or constitutive/inducible. Intrinsic resistance is linked to the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria, which is impermeable to water. Gram-positive bacteria can demonstrate resistance through alterations in ribosomal structure (e.g. through target site methylation or mutation). Post-translational methylation can result in cross-resistance to lincosamides and streptogramins (macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B, or MLSB, resistance). A further mechanism of resistance is efflux from cells. Finally, although rare, the inactivation of the drug itself can be a factor. The development of resistance may be rapid or gradual and resistance may also be cross-resistant between macrolides. |

|

MACROLIDES 15- MEMBERED RING Gamithromycin Tulathromycin |

Bovine Bovine, Swine |

|||

|

MACROLIDES 16- MEMBERED RING Carbomycin Josamycin Kitasamycin Mirosamycin Spiramycin Terdecamycin Tildipirosin Tilmicosin Tylosin Tylvalosin |

Avian Fish, Swine Avian, Swine, Fish Bee, Avian, Swine, Fish Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Swine Bovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Bee, Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Avian, Swine |

|||

|

MACROLIDES C17 Sedecamycin |

Swine |

|||

|

ORTHOSOMYCINS Avilamycin |

Avian, Rabbit, Swine |

Avilamycin is employed in the treatment of enteric diseases affecting poultry, swine and rabbits. Presently, this class of compounds is exclusively employed in veterinary medicine. |

Avilamycin is an antibiotic that stops proteins being built by blocking the A-tRNA site of ribosomal RNA 50S. It works against gram-positive bacteria but not gram-negative ones. This is probably because gram-negative bacteria have different ways of defending themselves. |

The molecular mechanisms underlying the resistance of avilamycin appear to be associated with mutations in single nucleotides at positions H89 and H91 of the ribosomal RNA 50S helices. |

|

NATURAL PENICILLINS (including esters and salts) Benethamine penicillin Benzylpenicillin Benzylpenicillin procaine / Benzathine penicillin Penethamate (hydroiodide) |

Bovine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Camel, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Camel, Caprine, Equine, Ovine, Swine Bovine |

Penicillins are of significant importance in the field of veterinary medicine due to their wide range of applications. Penethamate (hydroiodide) is currently only used in vet medicine. This group of antibiotics has been proven effective in treating sepsis, respiratory infections, and urinary tract infections. Few economical alternatives are available. |

Penicillins of this class have been demonstrated to be effective against a broad spectrum of microorganisms. These include many types of gram-positive and aerobic bacteria, as well as a limited number of gram-negative bacteria, such as Haemophilus and Neisseria species, and certain strains of Bacteroides, with the exception of B. fragilis. Broad-spectrum penicillins are derived semisynthetically and demonstrate efficacy against a wide range of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Semisynthetic penicillins with extended spectra have been demonstrated to be efficacious against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, some Proteus spp and, in a limited number of cases, even strains of Klebsiella, Shigella and Enterobacter spp.. |

Organisms devoid of a cell wall, such as Mycoplasma, possess an inherent resistance to beta-lactam antimicrobials. Penicillins are susceptible to hydrolysis by beta-lactamases, also known as penicillinases. Broad-spectrum penicillins are classified as sensitive beta-lactamases. The combination of broad-spectrum penicillins and beta-lactamase inhibitors has been demonstrated to enhance the efficacy of treatment against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. For instance, the combination of clavulanate-associated amoxicillin has been shown to enhance its efficacy. Semisynthetic penicillins with extended spectra are frequently characterised by a certain degree of beta-lactamase resistance and are typically effective against one or more characteristic penicillin-resistant organisms. |

|

AMDINOPENICILLINS Mecillinam |

Bovine, Swine |

|||

|

AMINOPENICILLINS Amoxicillin Ampicillin Hetacillin |

Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Ovine, Fish, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Ovine, Fish, Swine Bovine |

|||

|

AMINOPENICILLIN + BETALACTAMASE INHIBITOR Amoxicillin + Clavulanic Acid Ampicillin + Sulbactam |

Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Ovine, Swine Bovine, Swine |

|||

|

CARBOXYPENICILLINS Ticarcillin Tobicillin |

Equine Fish |

|||

|

UREIDOPENICILLIN Aspoxicillin |

Bovine, Swine |

|||

|

PHENOXYPENICILLINS Phenethicillin Phenoxymethylpenicillin |

Equine Avian, Swine |

|||

|

ANTISTAPHYLOCOCCAL PENICILLINS Cloxacillin Dicloxacillin Nafcillin Oxacillin |

Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Ovine, Swine Bovine, Caprine, Ovine, Avian, Swine Bovine, Caprine, Ovine Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Ovine, Swine |

|||

|

PHOSPHONIC ACID DERIVATIVES Fosfomycin |

Avian, Bovine, Fish, Swine |

Fosfomycin is a medication that plays a crucial role in the treatment of some fish infections. However, the limited availability of this pharmaceutical product in numerous countries leads to its classification as a Very Hard to Import (VHIA) medication. | Fosfomycin functions as a competitive inhibitor of the substrate phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) binding to the enzyme UDP-GlcNAc enolpyruvyl transferase (MurA). MurA catalyses the first committed step in bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis, which is thereby inhibited by the binding of fosfomycin via an irreversible covalent bond. | The following mechanisms are representative of resistance: • Drug inactivating enzymes. Several enzymes have been detected capable of modifying fosfomycin, including FosA, FosB, FosC and FosX. Of these, FosA has been found to be the most prevalent. • Reduced absorption, associated with mutation in genes involved in the GlpT and UhpT transport systems. In contrast, mutations in chromosomal genes or the over-expression of the target protein manifest less frequently. |

|

PLEUROMUTILINS Tiamulin Valnemulin |

Avian, Caprine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Swine |

The class of pleuromutilins is imperative in combating respiratory infections in both pigs and poultry. Moreover, this class of compounds has been demonstrated to be efficacious in the treatment of swine dysentery. However, the limited availability of these medications in certain countries has led to their classification as VHIA. |

The pleuromutilin antibiotics tiamulin and valnemulin target the bacterial cell wall. These antibiotics are active against gram-positive bacteria, mycoplasmas and anaerobes. They inhibit protein synthesis at the bacterial ribosome, preventing the polypeptide chain from growing. In therapeutic concentrations, pleuromutilin exerts a bacteriostatic effect. |

The development of resistance to pleuromutilins occurs through mutations to chromosomal targets. These occur in the 23S rRNA and rplC genes linked to bacterial ribosomes. Mutations are not transferred horizontally and take time to appear. |

|

POLYPEPTIDES Bacitracin Enramycin Gramicidin |

Avian, Bovine, Rabbit, Swine, Ovine Avian, Swine Equine |

Bacitracin is employed in the treatment of necrotic enteritis in poultry. The following diseases and conditions are treated with this class of antibiotics: -septicaemias -colibacillosis -salmonellosis -urinary infections |

The mechanism of action of this antibiotic involves interference with cell membrane function, suppression of cell wall formation via prevention of peptidoglycan strand formation, and inhibition of protein synthesis. It has been demonstrated to possess bactericidal activity, and the presence of divalent cations, such as zinc, is a prerequisite for its activity. |

Rare resistance cases reported. |

|

POLYMYXINS Polymixin B *Polymixin E (colistin) |

Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine |

Polymyxin E (colistin) is employed in the treatment of Gram-negative enteric infections. |

Polymyxins are a group of antibiotics that have bactericidal properties. Their efficacy is attributable to their capacity to disrupt the phospholipid composition of bacterial cell membranes, thereby markedly compromising their permeability and functionality. The polymyxins have been shown to be more effective against gram-negative bacteria than gram-positive bacteria. |

The occurrence of resistance to antibiotics at the polymyxis is an exceptionally rare phenomenon, and it was hypothesised that this was dependent on chromosome mutations. This would limit the transmission to vertical dissemination. However, subsequent research has invalidated this hypothesis. This is due to the discovery of a novel and highly conjugable plasmid-mediated gene, designated mcr-1, which confers colistin resistance. |

|

QUINOLONES FIRST GENERATION Flumequin Miloxacin Nalidixic acid Oxolinic acid |

Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Fish Bovine Avian, Bovine, Rabbit, Fish, Swine, Ovine |

The following conditions are indicated for treatment with quinolones of the 1st generation: • Septicaemias • Colibacillosis. |

Quinolones are a class of antibiotics that demonstrate bactericidal properties. These antibiotics possess a multitude of structurally analogous ring frameworks and demonstrate several shared characteristics. The quinolones inhibit bacterial enzyme topoisomerases, in particular: - Topoisomerase II, also known as DNA gyrase, which facilitates single-strand nicks in the DNA that underpin coiling and uncoiling - Topoisomerase IV, which plays a role in unravelling DNA as chromosomes separate. Subsequently, the reduction in inhibition results in a reduction of supercoiling. This, in turn, leads to the disruption of the spatial arrangement of DNA molecules and the failure of DNA repair mechanisms. |

The classic chromosomal resistance mechanism exhibited by bacteria involves specific target mutations in GyrA/GyrB (DNA gyrase, characteristic of gram-negative bacteria) and ParC/ParE (topoisomerase IV, characteristic of gram-positive bacteria). An alternative mechanism of resistance is the combined effect of increased expression of efflux pumps and decreased expression of porins (AcrAB and MexAB gene mutations), leading to decreased intracellular concentrations. In addition to these mechanisms, the presence of fluoroquinolone-resistant proteins (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS) encoded by transmissible plasmids has been confirmed. Qnr encodes proteins capable of protecting DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV from these antimicrobials. Other resistance mechanisms have been described, including AAC(6')-Ib-cr, which codes an enzyme (acetylase) capable of inactivating antimicrobials of two classes (aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones). It has been demonstrated that ciprofloxacina e norfloxacina are the only antimicrobials susceptible to inactivation by this enzyme. The qepA gene, located on a plasmid, has been identified as the causative agent of this mechanism and is responsible for the production of an efflux pump capable of only hydrophilic fluoroquinolones, such as norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin. The utilisation of these medications has been demonstrated to foster the emergence of resistance. |

|

QUINOLONES SECOND GENERATION (FLUOROQUINOLONES) Ciprofloxacin Danofloxacin Difloxacin Enrofloxacin Marbofloxacin Norfloxacin Ofloxacin Orbifloxacin Sarafloxacin |

Avian, Bovine, Swine Bovine, Caprine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Rabbit, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Bovine, Equine, Rabbit, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Avian, Swine Bovine, Swine Fish |

The wide range of applications make fluoroquinolones extremely important for veterinary medicine. Fluoroquinolones are critically important in the treatment of: • Septicaemias • Respiratory infection • Enteric diseases |

||

|

QUINOXALINES Carbadox Olaquindox |

Swine Swine |

Quinoxalines (carbadox) is employed in the treatment of digestive diseases affecting swine, including swine dysentery. Presently, this class of compounds is exclusively employed in veterinary medicine. |

NA | NA |

|

SULFONAMIDES Phthalylsulfathiazole Sulfacetamide Sulfachlorpyridazine Sulfadiazine Sulfadimethoxazole Sulfadimethoxine Sulfadimidine (Sulfamethazine, Sulfadimerazine) Sulfadoxine Sulfafurazole Sulfaguanidine Sulfamerazine Sulfamethoxine Sulfamonomethoxine Sulfanilamide Sulfapyridine Sulfaquinoxaline |

Swine Avian, Bovine, Ovine Avian, Bovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Ovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Equine, Ovine, Swine Bovine, Fish Avian, Caprine, Ovine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Avian, Fish, Swine Avian, Fish, Swine Bovine, Caprine, Ovine Bovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Rabbit, Ovine |

Sulfonamides are of significant importance in the field of veterinary medicine due to the wide variety of applications for which they are utilised. These classes alone or in combination are critically important in the treatment of a wide range of infections: • Bacterial • Coccidial • Protozoal |

Sulfonamides are derivatives of sulfanilamide, replacing various functional groups with the amido group. They are structurally similar to PABA (para-aminobenzoic acid). They competitively inhibit dihydropterate synthetase enzyme (DPS), interrupting the synthesis of dihydrofolic acid, precursor of the folic acid. Folic acid is coenzyme implicated in the synthesis of nucleic acids, whose absence leads to blockage of several enzymes present in this metabolic pathway. They have action bacteriostatic, but can be bactericidal at the high concentrations. Diaminopyrimidines, such as trimethoprim, I am able from inhibit dihydrofolate reductase, which is further into the folic acid synthesis pathway. The combination with sulfonamide is synergistic, is enhance the action antibiotic. Diaminopyrimidines are an antibiotics classes able to inhibit dihydrofolate reductase in bacteria and protozoa. However, alone these antibiotics are not effective against bacteria, furthermore can be resistance develops rapidly. For which they are frequently used on combined with sulfonamides, with action bactericidal. |

The phenomenon of resistance to sulphonamides can be categorised into two distinct types: intrinsic, chromosomally mediated, and acquired, plasmid-mediated. The chromosomal mechanism of resistance is attributable to mutations in the genes encoding dihydropterate synthetase. While the resistance plasmid mediated involves mutations in dihydrofolate reductases. The latter causing high-level resistance to trimethoprim. |

|

SULFONAMIDES+ DIAMINOPYRIMIDINES Ormetoprim+ Sulfadimethoxine Sulfamethoxypyridazine Trimethoprim+ Sulfonamide |

Avian, Fish Avian, Bovine, Equine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine |

|||

|

DIAMINOPYRIMIDINES Baquiloprim Ormetoprim Trimethoprim |

Bovine, Swine Avian Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine |

|||

|

STREPTOGRAMINS Virginiamycin |

Avian, Bovine, Ovine, Swine |

Virginiamycin is a significant antimicrobial agent that plays a crucial role in the prevention of necrotic enteritis (Clostridium perfringens). |

These antibiotics bind to the 50S subunit of bacterial ribosomes to stop protein production by blocking peptidyl transferases. |

Cross-resistance with macrolides and lincosamides is classified as macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance due to their similar mechanisms. |

|

TETRACYCLINES Chlortetracycline Doxycycline *Oxytetracycline Tetracycline |

Avian, Bovine, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Swine Avian, Bovine, Camel, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Bee, Avian, Bovine, Camel, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine Bee, Avian, Bovine, Camel, Caprine, Equine, Rabbit, Ovine, Fish, Swine |

The broad spectrum of applications renders tetracyclines of primary importance in veterinary medicine. This class of antibiotics is of particular significance in the treatment of chlamydial infections. Moreover, tetracyclines are of critical importance in the treatment of animals against heartwater (Ehrlichia ruminantium) and anaplasmosis (Anaplasma marginale), due to the absence of antimicrobial alternatives. |

Tetracyclines are a class of antibiotic that have the capacity to bind reversibly to the bacterial 30S ribosomal subunit. It has been demonstrated that these antibiotics are capable of impeding the process of ribosomal translation at the aminoacyl-tRNA acceptor (A) site on the mRNA ribosomal complex. While these antibiotics generally act as bacteriostatic agents, at elevated concentrations, they can attain bactericidal properties. It is also notable that doxycycline and minocycline have the capacity to inhibit metalloproteinases. |

The phenomenon of resistance to antibiotics is associated with two distinct mechanisms. The first of these mechanisms is characterised by the acquisition of efflux pumps, plasmid or transposon-mediated. These mechanisms can be transferred either via conjugation or transduction. The second mechanism is attributed to the synthesis of a protective protein, which functions by either preventing binding at the ribosomal target. |

|

THIOSTREPTON Nosiheptide |

Swine |

This class is currently used in the treatment of some dermatological conditions. |

Nosiheptide, an antibiotic, functions by impeding the formation of the 70S initiation complex. It has been demonstrated that Nosiheptide exerts its inhibitory effect on the following processes: -The initiation G protein IF2 -Elongation, by interfering with the G proteins EF-Tu, which is required for the rapid binding of the aminoacyl-tRNA to the ribosome -EF-G, which catalyzes the translocation of the tRNA-mRNA complex from the A and P sites to the P and E sites. |

The mechanism of resistance exhibited by nosiheptide is attributable to target site modification, a process catalysed by an enzyme action of a methyltransferase (NHR) belonging to the class SpoU. This results in resistance to the antibiotic nosiheptide through 2'O-methylation of the 23S rRNA at the nucleotide A1067, where the elongation (F-G) factor performs its function. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).