1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the primary cause of mortality and morbidity for individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD). In addition to common risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD), such as diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension, CKD patients are also exposed to cardiovascular risks associated with uremia, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and abnormal calcium-phosphorus metabolism (1). The risk of cardiovascular complications increases as renal function declines. For instance, individuals with CKD and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 45 ml/min/M2 are three times more likely to experience acute myocardial infarction as their first indication of CAD compared to those with normal kidney function (2). Furthermore, CKD patients in stages G3a to G4 (eGFR of 15-60 ml/min/1.73 m2) face approximately twice and three times the risk of cardiovascular mortality, respectively, in comparison to those without CKD. It is worth noting that CKD patients are at a higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease than progressing to end-stage renal disease (ESRD)(3).

Chronic kidney disease is defined by kidney damage and function levels, regardless of the underlying cause. It is classified into five stages, from Stage 1 with normal estimated glomerular filtration rate, to Stage 5 with estimated glomerular filtration rate <15ml/min/1.73m2 or hemodialysis(4,5). Hemodialysis patients with end-stage renal disease are susceptible to coronary artery disease, with prevalence from 30% to 60% (5). A study showed even asymptomatic individuals with ESRD had 41% prevalence of obstructive coronary artery disease. Hemodialysis patients face a ≥4-fold higher risk of thrombotic cardiovascular events, like acute myocardial infarction, compared to the general population(1,4).

Although significant advances have been made in treating acute coronary syndromes (ACS), patients with ESRD still experience a higher incidence of recurrent ischemic events and cardiovascular mortality(6). Unfortunately, clinical trials investigating the safety and effectiveness of anti-thrombotic agents in ACS or post percutaneous coronary intervention often exclude individuals with chronic kidney disease, especially those with ESRD and undergoing hemodialysis(7). As a result, there is limited evidence supporting the safe and effective use of advanced cardiovascular therapies in these patients, leading to fewer evidence-based treatments being prescribed after an ACS(8).

Dual antiplatelet therapy, comprising Aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors, is crucial in managing ACS, as it reduces platelet aggregation-associated risks (9). However, this therapy carries an increased risk of bleeding, necessitating a personalized approach to determine the appropriate duration of therapy. Patients with end-stage renal disease have a higher bleeding risk, irrespective of therapy use, and are identified as a risk factor for bleeding after PCI in the ESC guidelines (9). The Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk has also identified ESRD and dialysis as significant factors contributing to bleeding (10). Consequently, achieving an optimal antiplatelet regimen for patients with ESRD remains challenging.

This review article aims to critically examine the current evidence, guidelines, and controversies surrounding the use of dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT) in ACS patients with ESRD. We will explore the delicate balance between reducing thrombotic events and minimizing bleeding complications in this vulnerable population. Furthermore, we will analyse available data from observational studies, subgroup analyses, and limited randomized controlled trials to elucidate the efficacy and safety profiles of various DAPT regimens in ESRD patients with ACS.

2. High Thrombotic Risk in ESRD

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing haemodialysis face a significantly elevated risk of thrombosis and hypercoagulable states. This heightened susceptibility stems from multiple mechanisms, including increased platelet aggregation, elevated levels of coagulation factors such as Fibrinogen and factor VIII:C, reduced anticoagulant activity of proteins C and S, and impaired fibrinolytic function. Additionally, elevated plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations, high homocysteine levels, and the presence of lupus anticoagulant further contribute to this risk(11,13).

The dialysis process itself exacerbates the thrombotic risk by inducing platelet degranulation and activation. Studies have demonstrated increased levels of P-selectin and fibrinogen receptor PAC-1 in platelets of dialysis patients(12,13). Furthermore, endothelial injury and inflammation in ESRD compromise vascular integrity and antithrombotic properties, accelerating atherosclerosis and increasing plaque instability(6,14). The damaged endothelium loses its ability to produce natural anticoagulants and becomes more prone to attracting platelets and inflammatory cells. This endothelial dysfunction, coupled with the accelerated atherosclerosis observed in ESRD patients, creates an environment highly conducive to thrombus formation, particularly in areas of plaque rupture, plaque erosion or newly implanted stent.

Another critical factor in the hypercoagulable state of ESRD patients is the interaction of blood with external surfaces during hemodialysis. This interaction leads to alterations in extrinsic coagulation factors and tissue factor pathway inhibitors, resulting in the activation of the coagulation cascade(14). These multifaceted factors collectively contribute to the high thrombotic risk observed in ESRD patients, necessitating careful management and monitoring.

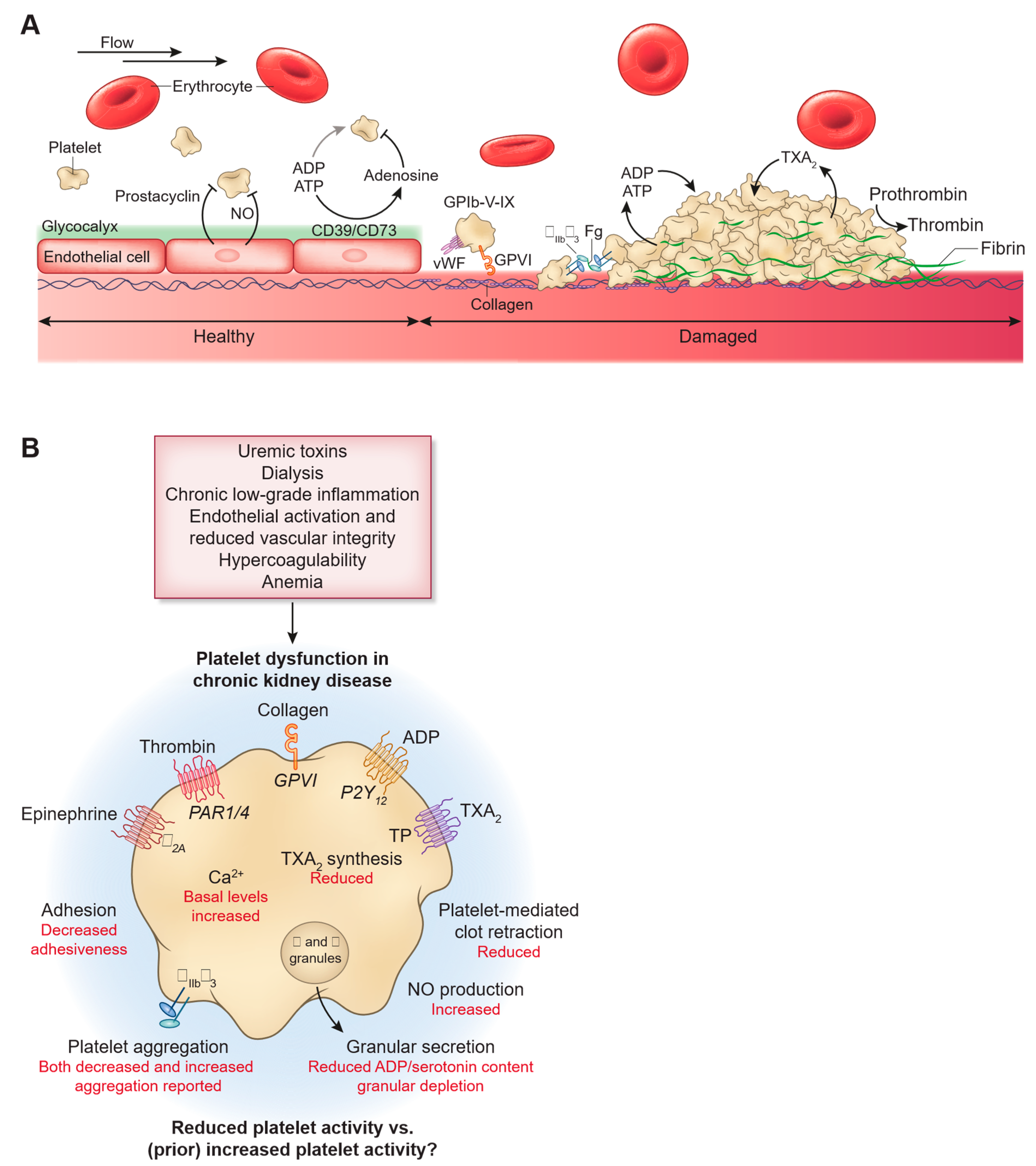

Figure 1.

Impact of CKD and uremia on platelet dysfunction. Published with permission from CJASN.(12).

Figure 1.

Impact of CKD and uremia on platelet dysfunction. Published with permission from CJASN.(12).

3. Mechanisms of Higher Bleeding Risk in ESRD Patients

Despite increased thrombotic risk, individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) exhibit higher bleeding tendencies, both spontaneously and under antiplatelet therapy. Patients with advanced kidney dysfunction have nearly doubled bleeding risk. Clinically, increased susceptibility to bleeding in these patients may present as symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding, subdural hematoma, epistaxis, retinal hemorrhage, hematuria, ecchymosis, purpura, bleeding from the gums, gingival bleeding, genital bleeding, hemoptysis, telangiectasia, hemarthrosis, and petechiae(12,16,).

Platelet dysfunction in patients with severe renal impairment is a recognized issue. The disturbance of platelet α-granules, which exhibit an increased ATP/ADP ratio and reduced serotonin content, is a significant abnormality contributing to bleeding problems in these individuals(17,18). Additionally, the release of ATP triggered by thrombin, along with elevated calcium levels and disrupted intracellular calcium flux in response to various stimuli, has been linked to platelet dysfunction and bleeding. Furthermore, deregulation of arachidonic acid and disturbed prostaglandin metabolism in platelets of uraemic patients impairs synthesis and/or release of thromboxane A2, which reduces platelet adhesion and aggregation, leading to a higher risk of bleeding. Moreover, fibrinogen fragments interfere with haemostasis by competitively binding to the glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa receptors on platelets, decreasing platelet adhesion and aggregation potential. Additionally, plasma of uremic patients contains higher levels of vasoactive substances, such as Nitric Oxide, which can affect platelet aggregation function(17,18,19).

Additionally, Anaemia of chronic renal disease plays a crucial role in increasing both bleeding and thrombotic risk. Erythrothyte number declines as CKD progresses (Approximately 13% reduction in CKD4 and 28% in CKD5) secondary to reduced erythropoietin in diseased kidneys. This reduction in red blood cells reduces the displacement of platelets off the axial flow towards the vessel wall impairing its function in hemostasis (40,41).

Dialysis has been shown to improve platelet function and reduce the risk of bleeding, although it does not eliminate it entirely. The interaction between blood and artificial surfaces during dialysis may cause chronic platelet activation, leading to platelet exhaustion and dysfunction. Additionally, research has found that plasma levels of NO inducers, such as tumor necrosis factor-a and interleukin-lb, increase during the dialysis process(19,20).

4. Balancing the Thrombotic and Bleeding Risks,Navigating the Challenges

The primary antiplatelet therapies used in patients with ACS are acetylsalicylic acid and P2Y12 inhibitors(9). However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the most effective antiplatelet strategy for individuals with ESRD due to their limited representation or exclusion from major trials assessing such therapies(7). As a result, the current knowledge about antiplatelet therapy in ESRD patients is primarily derived from underpowered post hoc subgroup analyses or large registries (12). Moreover, the distinctive biological characteristics of these patients, which make them susceptible to both thrombosis and bleeding, further complicate the selection of the optimal antiplatelet therapy strategy (16,17). According to the current ESC ACS guidelines, patients with ACS are recommended to receive aspirin in addition to potent P2Y12 inhibitors like ticagrelor and prasugrel (9). In the absence of specific data, ESRD patients are typically treated with the same antiplatelet therapy as those with normal renal function (21).

4.1. Acetylsalicylic Acid

Aspirin functions by irreversibly inhibiting cyclooxygenase, thereby inhibiting thromboxane production. Its elimination mainly occurs through hepatic metabolism, but it is also excreted unchanged in urine, the extent of which depends on dosage and urinary pH (37). The efficacy of aspirin for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including end stage renal disease (ESRD), presenting with ACS, is well established (

Table 1). Studies such as the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project and McCullough et al. (42) have demonstrated that aspirin reduced in-hospital mortality by 64.3% to 80% across all quartiles of creatinine clearance (CrCl), including ESRD and dialysis patients. However, it was observed that patients with ESRD were less likely to receive aspirin compared to those without ESRD (67.0% vs. 82.4%, p < 0.001) . Additionally, patients who did not receive aspirin upon admission had a higher likelihood of developing heart failure or cardiogenic shock (42,43,44). Regarding the safety of low-dose aspirin in secondary prevention for coronary artery disease, two studies indicated no increased risk of major bleeding. In the First United Kingdom Heart and Renal Protection (UK-HARP) trial, an RCT involving CKD patients, chronic hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis patients, and previous kidney transplant recipients, no increased risk of major bleeding (defined as fatal or requiring hospitalization) was observed on 100 mg aspirin in CKD patients (relative risk, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.19–2.31). However, there was a three-fold increase in the risk of minor bleeding (defined as epistaxis, ecchymosis, or bruising) (RR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.5–5.3) (45). Moreover, the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) showed no increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (RR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.88–1.17) in individuals taking 100 mg/d of aspirin compared to those not taking aspirin (44, 46).

4.2. Potent P2Y12 Inhibitors vs Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel and Prasugrel are both P2Y12 receptor inhibitors, serving as prodrugs that selectively and irreversibly inhibit the P2Y12 receptor (22,23). The blockade of the P2Y12 receptor occurs early in the platelet aggregation cascade, a crucial signaling pathway for platelet activation. Unlike Clopidogrel and Prasugrel, Ticagrelor is not a prodrug and does not necessitate metabolic conversion to an active form; it acts directly on P2Y12 receptors, and its effects are reversible(24). Clopidogrel, on the other hand, becomes active through multiple activation steps by the cytochrome P450 system. As a result, Ticagrelor and Prasugrel exhibit more potent antiplatelet effects compared to Clopidogrel (25). This superiority over Clopidogrel has been demonstrated in patients with ACS who also have chronic kidney disease(CKD)(6).

Clopidogrel remains the most frequently utilized P2Y12 inhibitor in patients with advanced renal disease and undergoing dialysis (6,26). However, it has several drawbacks, including a delayed onset of action, modest and variable platelet inhibition, and a high level of on-treatment platelet reactivity (HPR) observed in a significant proportion of patients (27). Previous research has shown that patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and those on hemodialysis (HD) therapy display higher platelet reactivity when treated with clopidogrel compared to individuals with normal kidney function, significantly reducing its effectiveness in these patients (28,29). Moreover, a notable percentage of HD patients demonstrated nonresponsiveness (resistance) to clopidogrel in another study (30). Accumulating evidence has established that high on-treatment platelet reactivity (HPR) is linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular death and recurrent ischemic events, including myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis (29,30,31,32).

Several dedicated studies have investigated the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of potent oral P2Y12-ADP receptor antagonists in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (

Table 1). Many of these studies involved comparisons with clopidogrel. Geong et al. demonstrated that ticagrelor exhibited a more rapid and substantial platelet inhibition compared to clopidogrel, effectively overcoming high on-treatment platelet reactivity (HPR) in patients resistant to clopidogrel and undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (30). Moreover, the rates of offset of the antiplatelet effect, as assessed by IPA (5 and 20 mmol/L of ADP stimuli), were higher for ticagrelor than for clopidogrel in the 1 to 48 hours after the last dose .Alexopoulos et al. showed that the maintenance dose of ticagrelor effectively reduced platelet reactivity in hemodialysis (HD) patients who had a poor response to clopidogrel. These patients had received regular hemodialysis for over six months and had ongoing clopidogrel treatment (75 mg/d). Platelet reactivity assessment was performed, and patients with ≥235 PRU (platelet reactivity unit) were considered to have high on-treatment platelet reactivity. Subsequently, these patients were administered ticagrelor alone for 15 days, and platelet reactivity was measured again. The baseline platelet reactivity for these patients was 310.4±52.9 PRU and decreased significantly to 137.7±77.9 PRU after ticagrelor treatment (P<0.001)(33).

The potent P2Y12 inhibitors mentioned earlier demonstrated biological superiority over clopidogrel , leading to positive clinical outcomes in various trials. For instance, in the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial, a multicenter randomized double-blind study, ticagrelor, when compared to clopidogrel, resulted in a decrease in the combined occurrence of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or stroke. However, it was also associated with an increased incidence of bleeding not related to procedures (34). In a subset analysis of the PLATO trial, the benefits of ticagrelor were even more pronounced in patients with all degrees of chronic kidney disease (CKD), including advanced stages, showing a relative reduction of 23% in the primary ischemic end point (34).

Furthermore, in the United States Renal Data System registry of Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), registry data highlighted the effectiveness and safety of clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor. The study included individuals who received new prescriptions for P2Y12 inhibitors and were tracked until death or censoring. The primary focus was on P2Y12 inhibitor assignment as the exposure variable and death as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes encompassed cardiovascular (CV) death, coronary revascularization, and gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage.The results revealed that prasugrel demonstrated superiority over both clopidogrel and ticagrelor by showing a reduced risk of death. Furthermore, compared to clopidogrel, prasugrel also reduced the risk of coronary (35).

The study conducted by Edfors et al., based on the SWEDEHEART Registry data (36), aimed to compare the efficacy of ticagrelor and clopidogrel in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for ACS. The total patient cohort consisted of 45,206 individuals, with 1,735 of them having an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 30. The primary outcome measured was a composite of death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke, while the secondary outcome focused on rehospitalization due to bleeding. The unadjusted 1-year event rate for the composite endpoint of death, MI, or stroke in patients with eGFR less than 30 was 48.0% for those treated with ticagrelor and 64.0% for those treated with clopidogrel.After adjustment, ticagrelor was found to be associated with a lower 1-year risk of the composite outcome when compared with clopidogrel for all patients. For those with an eGFR less than 30, the hazard ratio was 0.95 (95% confidence interval: 0.69 to 1.29), and the P-value for interaction was 0.55. However, it is important to note that patients treated with ticagrelor had a higher risk of bleeding compared to those treated with clopidogrel, and the hazard ratio for the eGFR less than 30 group was 1.79 (95% confidence interval: 1.00 to 3.21)

Interestingly, in medically managed ACS patients with CKD, including those with severe CKD, prasugrel did not demonstrate any advantages when compared to clopidogrel combined with aspirin. The TRILOGY ACS trial (Targeted Platelet Inhibition to Clarify the Optimal Strategy to Medically managed ACS involved a randomized comparison of prasugrel and clopidogrel therapy in conjunction with aspirin among medically-managed ACS patients. The main study assessed the primary endpoint, which was a combination of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke, and found no significant difference between prasugrel and clopidogrel (13.9% versus 16.0%; P=0.20).Moreover, the rates of severe and intracranial bleeding were comparable in both treatment groups (TIMI major 2.1% versus 1.5%; P=0.27). A subgroup analysis was conducted, revealing that patients with moderate or severe CKD faced an elevated risk of both ischemic and bleeding events. However, when comparing outcomes between prasugrel and clopidogrel in these subgroups, no discernible differences were observed (37)

A recent meta-analysis (38) investigated the clinical effectiveness and safety of various antiplatelet therapy regimens that exhibit potent platelet-inhibition activity compared to a standard dose of clopidogrel-based dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in individuals with CKD, including those with ESRD and undergoing dialysis. The study compared the outcomes of doubled loading dose (LD) clopidogrel-based DAPT, doubled maintenance dose (MD) clopidogrel-based DAPT, prasugrel-based DAPT, and ticagrelor-based DAPT.The findings revealed that antiplatelet therapy regimens with enhanced platelet inhibition beyond the standard clopidogrel-based DAPT significantly improved clinical outcomes in patients with ACS and CKD, including ESRD and dialysis patients. These improvements included reduced all-cause mortality (relative risk [RR] 0.67, p=0.003), major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (RR 0.79, p<0.00001), and myocardial infarction (MI) (RR 0.28, p=0.0007) without an increase in major bleeding (RR 1.14, p=0.33).However, a subgroup analysis demonstrated that the intervention led to a substantial increase in both major and minor bleeding in patients with severe CKD (eGFR < 30 mL/min) or those on hemodialysis (RR 1.30; 95% CI 1.09, 1.55; p=0.002).

4.3. The Duration of DAPT After PCI

Determining the optimal duration of DAPT following coronary revascularization through percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) poses a challenge for clinicians dealing with patients having ESRD. According to current ESC guidelines, the recommended DAPT duration for ACS patients who received drug-eluting stents (DES) is typically 12 months (9). Park et al. (39) conducted a population-based trial to investigate the ischemic and bleeding outcomes of prolonged DAPT in over 5000 dialysis patients who underwent DES implantation, with most of them having the DES placed after an ACS episode.The study compared continued DAPT with discontinued DAPT using landmark analyses, evaluating outcomes at 12, 15, and 18 months after DES implantation. The primary outcome measured was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), defined as a composite of mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, and stroke. A longer DAPT duration was associated with a significant reduction in MACEs, suggesting its benefit in preventing adverse cardiovascular events. However, it’s important to note that longer DAPT was also correlated with a higher incidence of bleeding events at all landmark points, although these differences were not statistically significant. Safety outcome was primarily focused on major bleeding events.

5. Conclusions

while advancements have been made in the management of ACS, there are unique challenges when it comes to treating ACS patients with ESRD. The use of potent P2Y12 inhibitors has shown promise in reducing ischemic risk but comes with an increased bleeding risk. Long-term DAPT also offers benefits, but further research and patient involvement in trials are necessary to establish solid evidence for tailoring anti-thrombotic therapy in this high-risk population. Embracing innovative approaches, such as platelet function testing-guided therapy, will aid in achieving improved care and outcomes for ACS patients with ESRD. By continually seeking new insights and individualized strategies, we can strive to bridge the existing gaps and provide better care for this vulnerable patient population.

References

- Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Wang AY, Kalyesubula R, Schaeffner E, Agarwal R. Epidemiology and risk of cardiovascular disease in populations with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022, 18, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go AS, Bansal N, Chandra M, et al. Chronic kidney disease and risk for presenting with acute myocardial infarction versus stable exertional angina in adults with coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Gao L. Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease Associated With Hemodialysis for End-Stage Renal Disease. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 800950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echefu G, Stowe I, Burka S, Basu-Ray I, Kumbala D. Pathophysiological concepts and screening of cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Front Nephrol. 2023, 3, 1198560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charytan D, Kuntz RE, Mauri L, DeFilippi C. Distribution of coronary artery disease and relation to mortality in asymptomatic hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007, 49, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonello L, Angiolillo DJ, Aradi D, Sibbing D. P2Y12-ADP Receptor Blockade in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circulation. 2018, 138, 1582–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charytan D, Kuntz RE. The exclusion of patients with chronic kidney disease from clinical trials in coronary artery disease. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 2021–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox CS, Muntner P, Chen AY, et al. Use of evidence-based therapies in short-term outcomes of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in patients with chronic kidney disease: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network registry. Circulation. 2010, 121, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R. , Asteggiano, R., Marjeh, M. Y. B., Rocca, B., Zeppenfeld, K., Geisler, T., Dan, G.-A., Ryödi, E., Coughlan, J. J., Wiseth, R., Koskinas, K., Galbraith, M., Sakhov, O., Neubeck, L., Falk, V., Cassese, S., Jüni, P., Lancellotti, P., Bouzid, M., … Giménez, M. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. European Heart Journal 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban P, Mehran R, Colleran R, et al. Defining High Bleeding Risk in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circulation 2019, 140, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo T, Koide M, Kario K, Suzuki S, Matsuo M. Extrinsic coagulation factors and tissue factor pathway inhibitor in end-stage chronic renal failure. Haemostasis 1997, 27, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaten CCFMJ, Schröer JR, Floege J, et al. Platelet Abnormalities in CKD and Their Implications for Antiplatelet Therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022, 17, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz PDMJ, Jurk PDRNK. Platelets in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease: Two Sides of the Coin. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2020, 46, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz J, Menke J, Sollinger D, Schinzel H, Thürmel K. Haemostasis in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014, 29, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kario K, Matsuo T, Yamada T, Nakao K, Shimano C, Matsuo M. Factor VII hyperactivity in chronic dialysis patients. Thromb Res. 1992, 67, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlacu A, Genovesi S, Ortiz A, et al. The quest for equilibrium: exploring the thin red line between bleeding and ischaemic risks in the management of acute coronary syndromes in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017, 32, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu Z, Pang X, Xiang Q, Cui Y. The Crosstalk between Nephropathy and Coagulation Disorder: Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Dilemmas. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023, 34, 1793–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbusera M, Remuzzi G, Boccardo P. Treatment of bleeding in dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2009, 22, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardo P, Remuzzi G, Galbusera M. Platelet dysfunction in renal failure. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2004, 30, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gäckler A, Rohn H, Lisman T, et al. Evaluation of hemostasis in patients with end-stage renal disease. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0212237 Published 2019 Feb 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szummer K, Lundman P, Jacobson SH, et al. Relation between renal function, presentation, use of therapies and in-hospital complications in acute coronary syndrome: data from the SWEDEHEART register. J Intern Med. 2010, 268, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullangi R, Srinivas NR. Clopidogrel: review of bioanalytical methods, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, and update on recent trends in drug-drug interaction studies [published correction appears in Biomed Chromatogr. 2009 Mar;23(3):334]. Biomed Chromatogr. 2009, 23, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbel M, Qaderdan K, Willemsen L, et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): the randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020, 395, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah RP, Shafiq A, Hamza M, et al. Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Cardiol. 2023, 207, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran H, Jneid H, Kayani WT, et al. Oral Antiplatelet Therapy After Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Review [published correction appears in JAMA. 2021 Jul 13;326(2):190]. JAMA 2021, 325, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippo O, D’Ascenzo F, Raposeiras-Roubin S, et al. P2Y12 inhibitors in acute coronary syndrome patients with renal dysfunction: an analysis from the RENAMI and BleeMACS projects. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020, 6, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller I, Besta F, Schulz C, Massberg S, Schönig A, Gawaz M. Prevalence of clopidogrel non-responders among patients with stable angina pectoris scheduled for elective coronary stent placement. Thromb Haemost. 2003, 89, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo JS, Kim W, Lee SR, et al. Platelet reactivity in patients with chronic kidney disease receiving adjunctive cilostazol compared with a high-maintenance dose of clopidogrel: results of the effect of platelet inhibition according to clopidogrel dose in patients with chronic kidney disease (PIANO-2 CKD) randomized study. Am Heart J. 2011, 162, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye Z, Wang Q, Ullah I, et al. Impact of hemodialysis on efficacies of the antiplatelet agents in coronary artery disease patients complicated with end-stage renal disease. J Thromb Thrombolysis, 23 February 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jeong KH, Cho JH, Woo JS, et al. Platelet reactivity after receiving clopidogrel compared with ticagrelor in patients with kidney failure treated with hemodialysis: a randomized crossover study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015, 65, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel O, El Ghannudi S, Jesel L, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention is mainly related to impaired P2Y12 inhibition by clopidogrel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011, 57, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin GA, Kirtane AJ, Chen S, et al. Impact of high on-treatment platelet reactivity on outcomes following PCI in patients on hemodialysis: An ADAPT-DES substudy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020, 96, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos D, Xanthopoulou I, Plakomyti TE, Goudas P, Koutroulia E, Goumenos D. Ticagrelor in clopidogrel-resistant patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012, 60, 332–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James S, Budaj A, Aylward P, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in acute coronary syndromes in relation to renal function: results from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circulation 2010, 122, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain N, Phadnis MA, Hunt SL, et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Oral P2Y12 Inhibitors in Patients on Chronic Dialysis [published correction appears in Kidney Int Rep. 2022 Aug 05;7(10):2321]. Kidney Int Rep. 2021, 6, 2381–2391 Published 2021 Jul 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edfors R, Sahlén A, Szummer K, et al. Outcomes in patients treated with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel after acute myocardial infarction stratified by renal function. Heart 2018, 104, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloni C, Cornel JH, Hafley G, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on long-term ischemic and bleeding outcomes in medically managed patients with acute coronary syndromes: Insights from the TRILOGY ACS Trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016, 5, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park S, Choi YJ, Kang JE, et al. P2Y12 Antiplatelet Choice for Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pers Med. 2021, 11, 222 Published 2021 Mar 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park S, Kim Y, Jo HA, et al. Clinical outcomes of prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary drug-eluting stent implantation in dialysis patients. Clin Kidney J. 2020, 13, 803–812 Published 2020 May 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GAARDER A, JONSEN J, LALAND S, HELLEM A, OWREN PA. Adenosine diphosphate in red cells as a factor in the adhesiveness of human blood platelets. Nature. 1961, 192, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livio, M. , Marchesi, D., Remuzzi, G., Gotti, E., Mecca, G., & De Gaetano, G. URAEMIC BLEEDING: ROLE OF ANAEMIA AND BENEFICIAL EFFECT OF RED CELL TRANSFUSIONS. The Lancet 1982, 320, 1013–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough PA, Sandberg KR, Borzak S, Hudson MP, Garg M, Manley HJ. Benefits of aspirin and beta-blockade after myocardial infarction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Heart J. 2002, 144, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain N, Hedayati SS, Sarode R, Banerjee S, Reilly RF. Antiplatelet therapy in the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with CKD: what is the evidence? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013, 8, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger AK, Duval S, Krumholz HM. Aspirin, beta-blocker, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with end-stage renal disease and an acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003, 42, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baigent C, Landray M, Leaper C, et al. First United Kingdom Heart and Renal Protection (UK-HARP-I) study: biochemical efficacy and safety of simvastatin and safety of low-dose aspirin in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005, 45, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrono C, García Rodríguez LA, Landolfi R, Baigent C. Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2005, 353, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).