1. Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), combination anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 antagonist, is the cornerstone of management in patients having acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and has proven benefit in reducing recurrent ischemic events and stent related thrombotic complications [

1]. DAPT is recommended for at least 6-12 months duration in patients undergoing PCI, irrespective of revascularization strategy, though aspirin therapy alone is almost always indicated indefinitely in such patients [

2]. Both clopidogrel and prasugrel are non-competitive thienopyridine P2Y12 adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists, which mainly act by inhibiting platelet aggregation [

1,

3]. For the specific choice of P2Y12 antagonist, prasugrel is preferred over clopidogrel for maintenance therapy in ACS patients after coronary stenting who are not at high risk for bleeding complications and have no history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke. Clopidogrel is usually recommended in cases where prasugrel is contraindicated (history of TIA/ stroke or high bleeding risk), not tolerated, or not available [

2,

4].

Inflammation and oxidative stress are major hallmarks in ACS progression, with inflammation being a known predictor of adverse cardiovascular events and oxidative stress playing a crucial role in endothelial dysfunction and atherothrombosis [

5,

6]. Inflammatory processes play a central role in the pathogenesis of ACS, with elevated levels of cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) contributing to endothelial dysfunction and plaque instability. Inflammation not only exacerbates atherosclerotic progression but also elevates the risk of adverse cardiovascular events [

7]. The presence of elevated inflammatory markers, such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), has been strongly associated with worse outcomes in ACS patients underscoring the importance of targeting inflammation as part of therapeutic strategies [

8]. Oxidative stress is another critical factor contributing to endothelial dysfunction and the progression of atherosclerosis in ACS. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) promote lipid oxidation and vascular inflammation, further destabilizing atherosclerotic plaques [

9]. Antioxidant mechanisms, including the body's ability to neutralize ROS, play a crucial role in mitigating oxidative damage. Total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) serves as a valuable measure of the cumulative antioxidative potential in individuals and has been linked to cardiovascular health. Lower TAOC levels have been associated with higher cardiovascular risk and worse outcomes in ACS patients [

10].

The majority of the clinical research on antiplatelet agents has primarily focused on thrombotic and hemorrhagic outcomes, with limited attention to their potential pleotropic (anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative) effects [

11]. Given the increasing burden of ACS and the critical role of DAPT in secondary prevention, it is imperative to understand the differential effects of these agents on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, which could provide insights into their broader impact beyond platelet inhibition. The present study was planned to address this existing knowledge gap by comparing the effects of clopidogrel and prasugrel on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers when given as DAPT with aspirin in ACS patients undergoing PCI.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

The CLAP-INOX (pleotropic effects of CLopidogrel And Prasugrel on INflammatory and OXidative stress markers in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention) was an investigator initiated, randomized, open-label, parallel-group study, conducted by the department of Pharmacology in collaboration with the departments of Cardiology, Biochemistry, and Microbiology at Pt. B.D. Sharma PGIMS, Rohtak, from July 2023 to August 2024 (CTRI Number CTRI/2023/07/055349).

2.2. Study Participants

Patients admitted to the cardiac catheterization laboratory and cardiac care unit (CCU) under the Department of Cardiology at our tertiary care hospital were assessed for potential eligibility in the study. Inclusion criteria were patients aged 18–65 years of either gender; diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) by a cardiologist; underwent coronary artery stenting; were the candidates for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines [

2]; and were willing to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included patients already on anti-platelet drugs; any contraindication to the use of study drugs; present or past history of active bleeding; any inflammatory or infective disease; patients with severe extra cardiac disease; pregnant or lactating females; and renal or hepatic dysfunction.

2.3. Study Interventions

Eligible subjects were randomized using a computer-generated random number list in a 1:1 ratio to two treatment groups (i) Group A: Aspirin (150–300 mg loading dose, 75 mg maintenance) + clopidogrel (300–600 mg loading dose, 75 mg maintenance) (AC group); and (ii) Group B: Aspirin (150–300 mg loading dose, 75 mg maintenance) + prasugrel (60 mg loading dose, 10 mg maintenance) (AP group) for 4 weeks. Commercially available drugs available in the hospital pharmacy were used with no subsequent change in any of the drugs or dosages throughout the study. Adherence to study interventions was enquired telephonically every week through active patient query; at least 80 percent adherence was considered adequate.

2.4. Study Objectives

The primary objective comprised of change in hs-CRP and TAOC levels at 4 weeks compared to baseline between AP and AC groups. Secondary objectives included (i) change in hemoglobin and hematocrit (packed cell volume; PCV) values at 4 weeks from baseline; (ii) incidence and severity of bleeding events categorized according to Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) classification [

12]; and (iii) other treatment related adverse events or study drug withdrawal/ discontinuations. Patients were instructed to report to the site on occurrence of any bleeding episode or other adverse events.

2.5. Estimation of Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Markers

Approximately 4-5 mL venous blood samples were collected from all the included patients at baselinei.e. before undergoing coronary stenting and after 4 weeks. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 20,000 rotations per minute (rpm) for 5 minutes and stored at -20 degrees Celsius for further analysis.

The levels of hs-CRP were measured using enzyme linked immunoassay (ELISA) method as per the instructions provided with the manufacturer’s kit (ichroma™).The principle of the hs-CRP assay is based on a fluorescence immunoassay using a sandwich detection method. Briefly, CRP (C-reactive protein) present in the sample binds to a detector antibody conjugated with a fluorescent label in the detection buffer. This antigen-antibody complex then migrates along a nitrocellulose membrane, where it is captured by an immobilized antibody on the test strip. The amount of fluorescent signal generated is proportional to the CRP concentration in the sample, which is then measured by a cartridge reader. Results are categorized as low (<1.0 mg/L), average (1.0–3.0 mg/L), or high (>3.0 mg/L) risk for cardiovascular disease. The test is precise, specific, and intended for in vitro diagnostic use.

The TAOC was determined using a colorimetric assay based on ferric reduction, adapted to a 96-well microplate format. This method relies on the principle that antioxidants present in the sample can reduce ferric ions (Fe³⁺) to ferrous ions (Fe²⁺), which subsequently form a coloured complex with a chromogenic agent. The intensity of the resulting colour, measured spectrophotometrically at 520 nm, is directly proportional to the antioxidant capacity of the sample.The assay was performed using reagents supplied in a commercially available TAOC kit (Biochain Incorporated). Absorbance values were used to calculate the antioxidant capacity, expressed relative to a standard or reference, as per the kit guidelines. All assays were performed in duplicate or triplicate to ensure reproducibility, and proper laboratory safety protocols were followed throughout the procedure.

2.6. Sample Size Calculation

The primary end point for sample size calculation was taken as the change in hs-CRP levels. The sample size was calculated on the basis of the observed difference in hs-CRP levels between clopidogrel and prasugrel groups in a previous study [

13]. Assuming a mean (SD) change in hs-CRP levels in clopidogrel group as 7.8 (10.67) mg/dL versus 13.67 (5.96) in prasugrel group, using a two-tailed test with α=0.05 and β=0.2, the sample size was calculated as 35 patients in each group. Assuming 20 percent lost to follow-up, a minimum of total 88 patients needed to be enrolled in both groups.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data was entered in Microsoft Excel and subjected to statistical analyses. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (inter-quartile range; IQR), and categorical variables as numbers (percentages). For continuous variables, within and inter-group comparisons were performed using paired t-test/ Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Student’s t-test/ Mann-Whitney U test, respectively, depending upon the distribution of data. Categorical variables were analysed by chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, whichever appropriate. All the analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) statistics version 30.0. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.8. Ethical Statement

The study was conducted after approval from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of our institute (BREC/23/TH-Pharma/07 dated 24.06.2023). A written informed consent was taken from all the participants, and adequate measures to ensure data privacy and subject confidentiality were taken.

3. Results

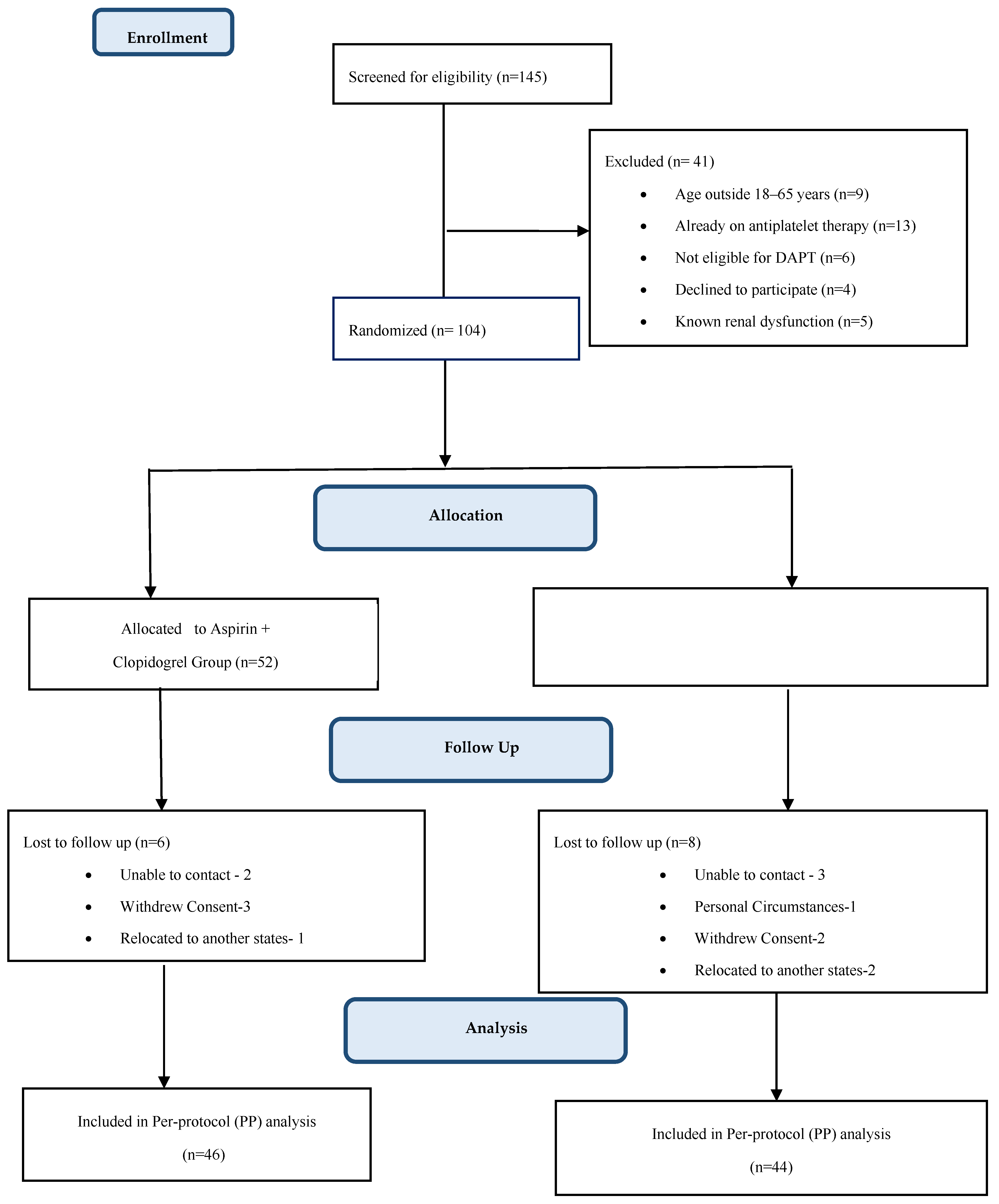

Out of 145 patients screened, 104 met the study inclusion criteria; of these, 52 were assigned to each of the two study groups. 6 patients in AC group and 8 patients in AP group were lost during follow-up. Analysis was done using the per protocol (PP) principle (

Figure 1).

At baseline, both the groups were comparable with respect to demographic profile, clinical and biochemical characteristics (

Table 1).

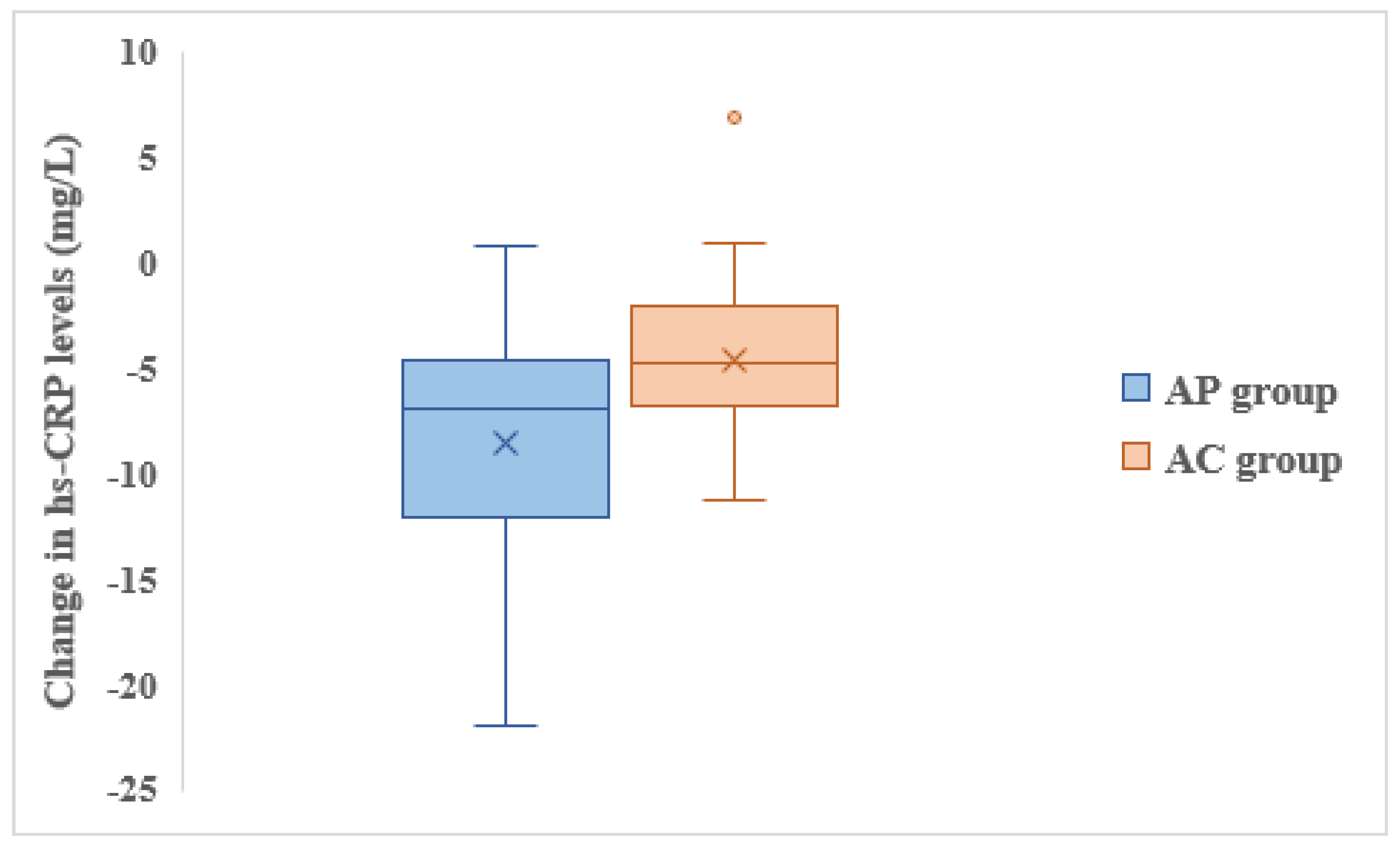

Both groups showed reduction in hs-CRP levels from baseline to 4 weeks, however, the reduction in AP group was significantly greater compared to the AC group (

Figure 2).

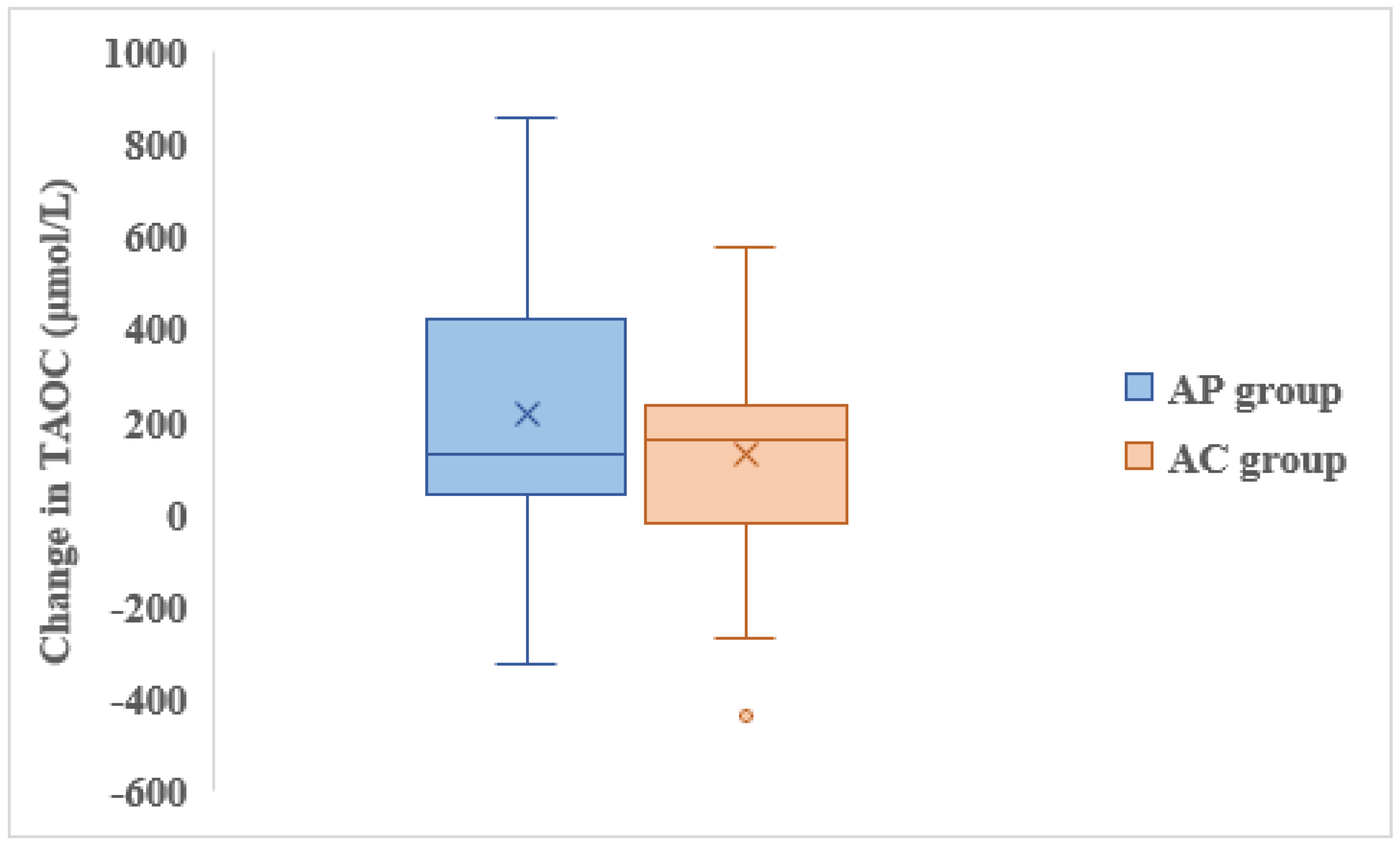

There was improvement in TAOC levels at 4 weeks compared to baseline in both groups; AP group showed greater increase in TAOC levels than AC group though this difference was not statistically significant (

Figure 3).

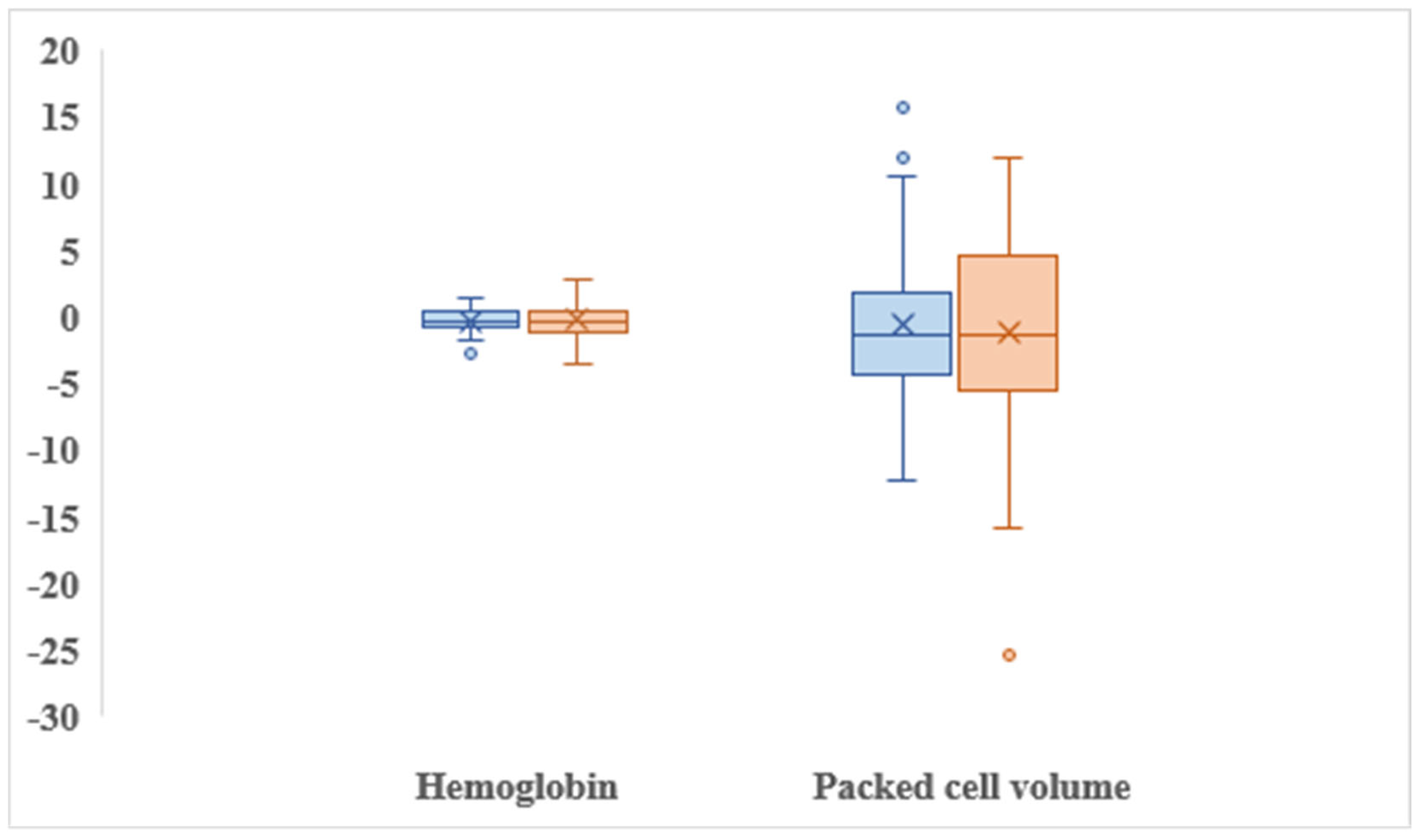

No statistically significant difference in change in hemoglobin levels (p=0.69) and PCV (p=0.65) were observed between two groups (

Figure 4).

A total of 20 and 21 adverse events were reported in AC and AP groups, respectively. 2 (4.3%) patients in AC group and 4 (9%) patients in AP group had bleeding episodes of easy bruising and bleeding from gums; all the events were categorized as type 1 (minimal bleeding, not actionable) according to BARC classification. Other commonly reported adverse events were headache, fatigue, weakness, itching, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting etc. All the adverse events were mild in intensity, transient, and spontaneously resolved without warranting any active intervention or treatment withdrawal/ discontinuation. Adherence to study interventions was more than 80 percent in both groups.

4. Discussion

Given the significant role of inflammation and oxidative stress as major hallmarks in ACS and to add to the existing knowledge base, the current study aimed to thoroughly investigate the comparative effects of clopidogrel versus prasugrel on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers when given as DAPT in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

We used hs-CRP as an inflammatory marker to evaluate the anti-inflammatory effects of DAPT. Both clopidogrel and prasugrel containing DAPT regimens exhibited significant reduction in hs-CRP levels at 4 weeks from baseline, indicating effective inflammation control. However, the reduction was significantly more in the AP compared to the AC group highlighting the greater anti-inflammatory efficacy of prasugrel compared to clopidogrel. Our findings are consistent with a published study [

13], which also reported a significant reduction in hs-CRP levels with prasugrel compared to clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI. Another study by Schnorbus et al [

14], also demonstrated that prasugrel therapy improved inflammatory markers including hs-CRP and endothelial function in patients undergoing PCI compared to clopidogrel and ticagrelor. Hence, it is evident that prasugrel consistently demonstrates higher efficacy in reducing systemic inflammation, offering additional advantage, particularly in patients with heightened inflammatory activity. The anti-inflammatory action of clopidogrel is mainly attributed to drug induced endothelial nitric oxide synthesis causing direct coronary vasodilation; this effect is independent of the drug’s anti-platelet action, indicating the drug’s pleotropic effect [

15]. Ramadan et al [

16], in a randomised placebo controlled study in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD), reported no significant reduction in hs-CRP levels with clopidogrel therapy over six weeks. This discrepancy may arise from differences in patient populations, as our study included patients with ACS undergoing PCI where inflammation plays a more prominent role. Additionally, the absence of use of aspirin in the study by Ramadan et al

16 could have contributed to the observed variability.

In our study, the effect of DAPT on oxidative stress was assessed using total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) levels. The mean baseline values of TAOC in both the groups were comparable to an earlier published study [

17] which reported a significantly lower TAOC in ACS patients (533.61 ± 232.47 µmol/L) compared to healthy controls (1091.62 ± 267.27 µmol/L, p < 0.001) thereby emphasising on the depletion of antioxidants in ACS and the heightened oxidative stress experienced by these patients. We observed significant improvement in TAOC at 4 weeks from baseline in both AC and AP groups with a relatively greater increase in TAOC in the prasugrel group, though it was not significant statistically. These results are consistent with the study by Schnorbus et al [

14], in which the authors observed a significant reduction in oxidative stress markers with prasugrel compared to clopidogrel in ACS patients undergoing PCI. In contrast, Willoughby et al [

18] reported no significant effect of clopidogrel on oxidative stress markers including asymmetric dimethyl arginine and myeloperoxidase in stable CAD patients; such discordance could be attributed to differences in study design particularly the exclusion of high-risk ACS patients in that study. Furthermore, the concurrent use of aspirin in our study likely potentiated the antioxidative effects of dual therapy, underscoring the importance of combination strategies in addressing oxidative stress in ACS. Nevertheless, these findings collectively suggest enhanced antioxidative properties of prasugrel complementing its potent anti-platelet benefits, which may confer additional clinical benefits in high-risk ACS patients.

We also evaluated the impact of DAPT on key haematological parameters including haemoglobin levels and PCV after 4 weeks of treatment. Both groups showed minimal changes in these parameters, indicating that neither combination significantly affected red blood cell indices during the study period. These findings align with existing literature [13-18] suggesting that dual antiplatelet therapy, particularly within the short-term follow-up period, does not significantly alter haematological parameters unless major bleeding or adverse events occur.

Few limitations in the present study are worth mentioning. The study was conducted at a single centre, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations with different demographic and clinical profiles. A relatively short follow-up period of four weeks limits the ability to assess the long-term effects of dual antiplatelet therapy on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, as well as clinical outcomes such as major adverse cardiovascular events. Variability in patient characteristics, such as genetic factors influencing drug metabolism (e.g., CYP2C19 polymorphisms affecting clopidogrel efficacy) was not assessed, which may have influenced treatment outcomes.

5. Conclusions

AP group exhibited greater reduction in oxidative stress and inflammatory markers compared to AP group with no significant differences in haematological safety or tolerability. These findings suggest that prasugrel based DAPT may provide additional benefits for patients with ACS, particularly in managing inflammation and oxidative stress. Future large-scale, multi-centre studies with longer follow-up durations are warranted to confirm these findings and further explore the long-term pleiotropic effects of these dual antiplatelet therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M., A.K., M.K.; Methodology, S.V., N.M., A.K., M.K., A.P.; Formal analysis, S.V., N.M., V.K., J.J., Investigation, S.V., A.K., M.K., A.P.; Resources, N.M., A.K., M.K., A.P.; Data curation, S.V., V.K., J.J.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.V., N.M.; Writing—review and editing, S.V., N.M., A.K., M.K., A.P., V.K., J.J.; Supervision, N.M., A.K., M.K., A.P.; Project administration, S.V., N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Research and Development Cell, UHSR grant number R&D/UHSR/2024/1701.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of PGIMS/ UHS Rohtak (BREC/23/TH-Pharma/07 dated 24.06.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No data other than the data presented in the paper is available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DAPT |

Dual antiplatelet therapy |

| ACS |

Acute coronary syndromes |

| CAD |

Coronary artery disease |

| PCI |

percutaneous coronary intervention |

| hs-CRP |

high sensitivity C reactive protein |

| TOAC |

total antioxidant capacity |

| PP |

per-protocol |

| ADP |

adenosine diphosphate |

| TIA |

transient ischemic attack |

| IL-6 |

interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α |

tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| CTRI |

Clinical trial registry of India |

| ACC/AHA |

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association |

| PCV |

packed cell volume |

| BARC |

Bleeding Academic Research Consortium

|

References

- Brunton, L., & Knollmann, B. (2023). Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (14th ed.). McGraw Hill Professional.

- Rao, S.V.; O’dOnoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151. [CrossRef]

- Vrints, C., Andreotti, F., Koskinas, K. C., Rossello, X., Adamo, M., Ainslie, J., et al. (2024). 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. European Heart Journal, 45(36), 3415–3537.

- Kumbhani, D.J.; Cibotti-Sun, M.; Moore, M.M. 2025 Acute Coronary Syndromes Guideline-at-a-Glance. Circ. 2025, 85, 2128–2134. [CrossRef]

- Marchio, P.; Guerra-Ojeda, S.; Vila, J.M.; Aldasoro, M.; Victor, V.M.; Mauricio, M.D. Targeting Early Atherosclerosis: A Focus on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 8563845. [CrossRef]

- Tsirebolos, G.; Tsoporis, J.N.; Drosatos, I.-A.; Izhar, S.; Gkavogiannakis, N.; Sakadakis, E.; Triantafyllis, A.S.; Parker, T.G.; Rallidis, L.S.; Rizos, I. Emerging markers of inflammation and oxidative stress as potential predictors of coronary artery disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 376, 127–133. [CrossRef]

- Mangiacapra, F.; Di Gioia, G.; Pellicano, M.; Di Serafino, L.; Bressi, E.; Peace, A.J.; Bartunek, J.; Wijns, W.; De Bruyne, B.; Barbato, E. Effects of Prasugrel Versus Clopidogrel on Coronary Microvascular Function in Patients Undergoing Elective PCI. Circ. 2016, 68, 235–237. [CrossRef]

- Oprescu, N.; Micheu, M.M.; Scafa-Udriste, A.; Popa-Fotea, N.-M.; Dorobantu, M. Inflammatory markers in acute myocardial infarction and the correlation with the severity of coronary heart disease. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 1042–1048. [CrossRef]

- Theofilis, P., Sagris, M., Oikonomou, E., Antonopoulos, A. S., Tsioufis, K., &Tousoulis, D. (2022). Factors associated with platelet activation—Recent pharmaceutical approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(6), 3301.

- Silvestrini, A.; Meucci, E.; Ricerca, B.M.; Mancini, A. Total Antioxidant Capacity: Biochemical Aspects and Clinical Significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10978. [CrossRef]

- Eikelboom, J. W., Hirsh, J., Spencer, F. A., Baglin, T. P., & Weitz, J. I. (2012). Antiplatelet drugs. CHEST Journal, 141(2), e89S–e119S.

- Ben-Yehuda O, Redfors B. Validation of the bleeding academic research consortium bleeding definition: towards a standardized bleeding score (2016). J Am Coll Cardiol, 67(18), 2145-2147.

- Hajsadeghi, S.; Chitsazan, M.; Chitsazan, M.; Salehi, N.; Amin, A.; Bidokhti, A.A.; Babaali, N.; Bordbar, A.; Hejrati, M.; Moghadami, S. Prasugrel Results in Higher Decrease in High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Level in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Comparing to Clopidogrel. Clin. Med. Insights: Cardiol. 2016, 10, CMC.S32804–55. [CrossRef]

- Schnorbus, B.; Daiber, A.; Jurk, K.; Warnke, S.; Koenig, J.; Lackner, K.J.; Münzel, T.; Gori, T. Effects of clopidogrel vs. prasugrel vs. ticagrelor on endothelial function, inflammatory parameters, and platelet function in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary artery stenting: a randomized, blinded, parallel study. Eur. Hear. J. 2020, 41, 3144–3152. [CrossRef]

- Antonino, M.J.; Mahla, E.; Bliden, K.P.; Tantry, U.S.; Gurbel, P.A. Effect of Long-Term Clopidogrel Treatment on Platelet Function and Inflammation in Patients Undergoing Coronary Arterial Stenting. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 103, 1546–1550. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R., Dhawan, S. S., Syed, H., Pohlel, F. K., Binongo, J. N., Ghazzal, Z. B., et al. (2014). Effects of clopidogrel therapy on oxidative stress, inflammation, vascular function and progenitor cells in stable coronary artery disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 63(4), 369.

- Haque, R.; Hafiz, F.B.; Habib, A.; Radeen, K.R.; Islam, L.N. Role of complete blood count, antioxidants, and total antioxidant capacity in the pathophysiology of acute coronary syndrome. Afr. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, S.R.; Luu, L.-J.; Cameron, J.D.; Nelson, A.J.; Schultz, C.D.; Worthley, S.G.; Worthley, M.I. Clopidogrel Improves Microvascular Endothelial Function in Subjects with Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Hear. Lung Circ. 2014, 23, 534–541. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).