1. Introduction

Underwater acoustic propagation research essentially involves solving wave equations in heterogeneous marine media, with its core focus on revealing how spatiotemporal variations of environmental parameters modulate acoustic fields[

1]. Mesoscale processes including eddies, oceanic fronts, and internal waves alter sound speed profile structures through thermohaline redistribution [

2,

3], leading to acoustic path refraction and modal energy redistribution [

4]. Baroclinic instability-generated mesoscale eddies induce potential vorticity anomalies that deform isopycnal surfaces, modifying vertical sound speed gradients. Such perturbations affect convergence zone distributions within the theoretical framework of waveguide invariants [

5,

6]. Studies have shown that the presence of mesoscale eddies significantly alters the primary characteristics of the acoustic field compared to fields without eddies. These changes include the shift of convergence zones, changes in the order of multipath arrivals, and horizontal refraction issues [

7]. Additionally, mesoscale eddies can lead to modifications in the structural characteristics of convergence zones and the emergence or disappearance of surface duct effects[

8]. Research on theoretical models for acoustic field calculation under rough sea surfaces has led to the development of many mature theories and methods. Commonly used approaches include the Kirchhoff approximation, the small-slope approximation [

9,

10], and the RAM (Range-dependent Acoustic Model) based on parabolic equations [

11,

12]. Scholars have conducted extensive research on the characteristics of acoustic fields under rough sea surfaces, primarily focusing on the effects of acoustic attenuation, spatiotemporal correlations, and the time-of-arrival of signals.

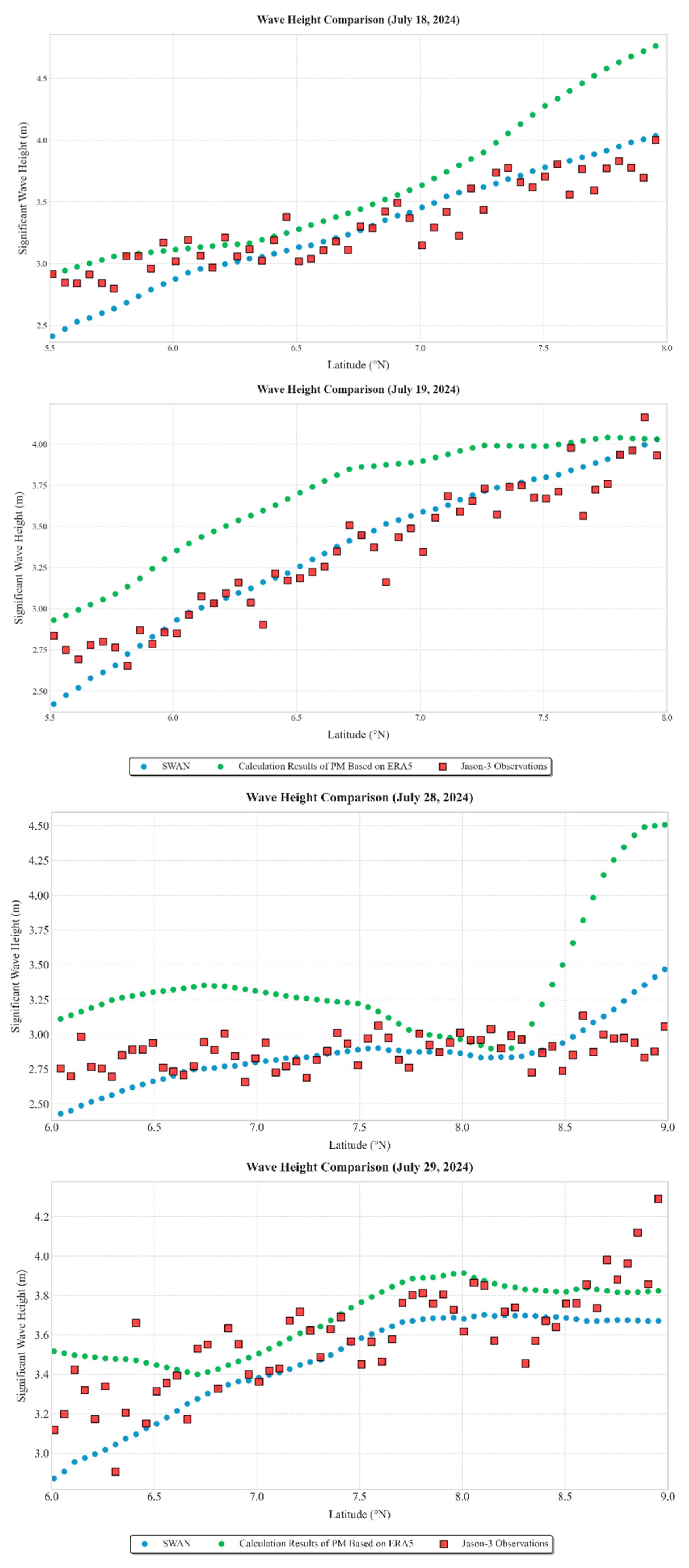

In the Gulf of Aden, acoustic propagation characteristics are controlled by monsoon-driven multiscale processes. The summer southwest monsoon (June-September mean wind speed >12 m/s) activates the Somali Current (surface velocity >1.5 m/s) [

13], generating the Great Whirl eddy through barotropic instability. Argo float observations indicate that this eddy modifies thermohaline structures via vertical mixing, producing mixed layer depth anomalies up to 26.7 m in its core region [

1]. Enhanced sea surface roughness under monsoon conditions (significant wave height reaching 4 m [

14]) creates coupled perturbations through air-sea interactions, establishing compound modulation sources for acoustic propagation [

15].

The coupled effects of mesoscale eddies and sea surface roughness on acoustic propagation have gained increasing attention [

16,

17]. Early theoretical models quantified eddy-induced sound speed variations using quasi-geostrophic potential vorticity equations [

5], while contemporary studies employ three-dimensional ocean-acoustic coupled frameworks. Regarding the influence of eddies on sound propagation, [

18] utilized the FOR3D model to investigate the impact of a cold eddy in the Luzon Strait on the convergence zone of the sound field based on the 3-D temperature and salinity fields output from the HYCOM model .[

19] demonstrated through MITgcm-BELLHOP integration that interactions between Luzon cold eddies and tidal currents shift convergence zones forward by 5 km with 0.1-s arrival delays. Regarding rough surface impacts, [

20] compared the acoustic pressure fields generated by broadband sound sources under different wind speed conditions and concluded that sea surface roughness is the primary factor causing acoustic signal attenuation, while bubble scattering and Doppler shifts are secondary factors. [

21]applied Ramsurf modeling with PM spectra and Monte Carlo simulations, revealing 4-6 dB increases in transmission loss under realistic sea states compared to smooth surface conditions.

Current research limitations persist in two aspects:

1) Most eddy-acoustic studies assume idealized smooth surfaces, overlooking coupled effects between vortical flows and wind-driven roughness[

22];

2) Traditional PM spectra fail to accurately represent sea states in topographically complex regions like the Gulf of Aden, where monsoon-regulated fetch limitations reduce spectral fidelity.

This study develops a coupled model integrating three-dimensional eddy-resolving sound speed fields and sea surface spectra simulated by SWAN (Simulating WAves Nearshore). Through BELLHOP ray tracing simulations, we quantify the synergistic interaction between mesoscale eddies and sea surface roughness on acoustic propagation, providing theoretical support for optimizing underwater detection systems in monsoon-affected seas.

2. Methodology

To accurately characterize sea surface roughness in the target maritime area, the SWAN wave model was implemented to replace the conventional PM spectrum [

23]. This approach was combined with the Monte Carlo method (also termed linear filtering technique) to establish a one-dimensional dynamic sea surface roughness model. The study area exceeds 3000 m in depth, satisfying deep-water waveguide assumptions. Furthermore, BELLHOP's multi-patch configuration efficiently incorporates rough sea surface boundaries, making it the ideal choice for acoustic propagation simulations. By parameterizing the upper boundary conditions, this framework systematically integrates sea surface perturbation effects. At the same time, it ensures computational stability in deep-water scenarios.

2.1. Wave Model

The SWAN (Simulating WAves Nearshore) model, developed at Delft University of Technology, represents a third-generation spectral wave model that has reached operational maturity through decades of refinement. Its theoretical foundation is established through the action balance equation derived from energy conservation principles, incorporating the core features of third-generation wave models while specifically addressing shallow-water hydrodynamic requirements[

24]. The governing equations are solved using a fully implicit finite-difference scheme, ensuring unconditional numerical stability that eliminates spatial grid and temporal step constraints. The source terms encompass conventional energy components including wind input, nonlinear wave-wave interactions, whitecap dissipation, and bottom friction, with additional incorporation of depth-induced wave breaking mechanisms to enhance simulation fidelity across coastal-offshore transition zones.[

25,

26]

The SWAN model solves the spectral action balance equation. While spectral energy density becomes non-conservative in ambient currents due to Doppler-shifting and energy transfer, the wave action

N(

σ,

θ) remains a conserved quantity that advects with the sum of group velocity and ambient current velocity. In a Cartesian coordinate system, the wave action balance equation can be expressed as:

In the governing equation, the first term on the left-hand side (LHS) represents the temporal variation rate of wave action density. The second and third terms denote the propagation of wave action in the x- and y-directions of the geographical space, respectively. The fourth term accounts for the advection of wave action in the σ-space (relative frequency domain) induced by ambient currents and varying water depths. The fifth term describes the refraction-induced redistribution of wave action in the θ-space (directional domain), which arises from depth- and current-driven modifications to wave phase speed. The right-hand side (RHS) S/σ encapsulates the source/sink terms, where S aggregates energy inputs and outputs from Wind energy transfer (Sin); Nonlinear wave-wave interactions(Snl); Bottom friction dissipation(Sbot); Whitecap dissipation(Swc); Depth-induced wave breaking(Sds)

The governing velocity components in the wave action balance equation are defined as:

The propagation velocities in the wave action balance equation encapsulate distinct physical mechanisms governing spectral evolution. In geographical space, and Cy represent the total advection velocities in the x- and y-directions, respectively, combining the wave group velocity components (Cg cos θ and Cg sin θ) with ambient current velocities (U and V) to resolve wave-energy transport under coexisting wave-current dynamics. In spectral space, Cσ quantifies the frequency shifting rate in the relative frequency (σ) domain, driven by temporal variations () and spatial gradients of currents or depths (), which collectively induce Doppler-like spectral compression/expansion. Meanwhile, Cθ governs refraction in the directional (θ) domain, where depth- or current-induced gradients (,) redirect wave energy through phase-speed modifications, with the 1/k term (k: wavenumber) ensuring kinematic consistency with the linear dispersion relation .

2.2. Acoustic Ray Model

Selecting an appropriate sound field model is essential for accurately investigating the principles of sound propagation in the ocean. Such a model must be capable of capturing the complexities of the horizontally varying ocean environment. In the 1980s, Porter and Bucker [

27] introduced the Gaussian beam approximation, initially used in geoacoustics, into underwater acoustic computations. The model is available through the Acoustics Toolbox, a widely used software suite for underwater acoustic simulations. This innovation led to the development of the BELLHOP ray model, which calculates the sound field based on a given sound speed profile—an essential factor in underwater acoustic propagation. Notably, it can simulate the sound field in acoustic shadow zones and focal dispersion regions, areas where traditional ray acoustics often fail. Additionally, the model addresses challenges associated with low-frequency sound propagation, further enhancing accuracy in such scenarios. Due to its clear physical interpretation and computational efficiency, the BELLHOP ray model has been widely adopted in range-dependent hydroacoustic propagation studies[

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

The BELLHOP model employs the Gaussian beam method as its primary approach. The Gaussian beam method models sound propagation using beams of specific width, characterized by two parameters: curvature and width. The intensity distribution of the sound beam is described by a Gaussian function. This approach represents the sound field generated by the source as the superposition of energy contributions from multiple sound beams.[

36]

The Gaussian beam model simplifies the vector equation that describes sound propagation into the ray equation and its accompanying equation:

where

c is the sound speed;

r(

s),

z(

s) indicate the coordinates of the ray in the column coordinate system; s represents the arc length in the direction of the ray. Here, the auxiliary variables ξ(

s), ξ(

s) are introduced to write the equation in first-order form. A set of concomitant components

p(

s) and

q(

s) are used to describe the curvature and width of the ray, and they form the accompanying equation for ray tracing:

where

is the sound speed curvature in the normal direction of the ray path. To derive

, first note that the derivative of c in the normal direction can be presented as:

where

n = (

n(r),

n(z)) is the normal of the ray and then the derivative is repeated in the normal direction, yielding:

Combining the auxiliary variables in Eq. (6)-(9), finally yielding:

This curvature formula utilizes only the second-order derivative of the sound speed concerning the coordinate r and z. In order to determine the trajectory of each beam and the accompanying parameters, the above equations should be discretized, initial conditions set, and then recurse. By summing the contribution of each beam, the distribution of the sound field can be obtained.

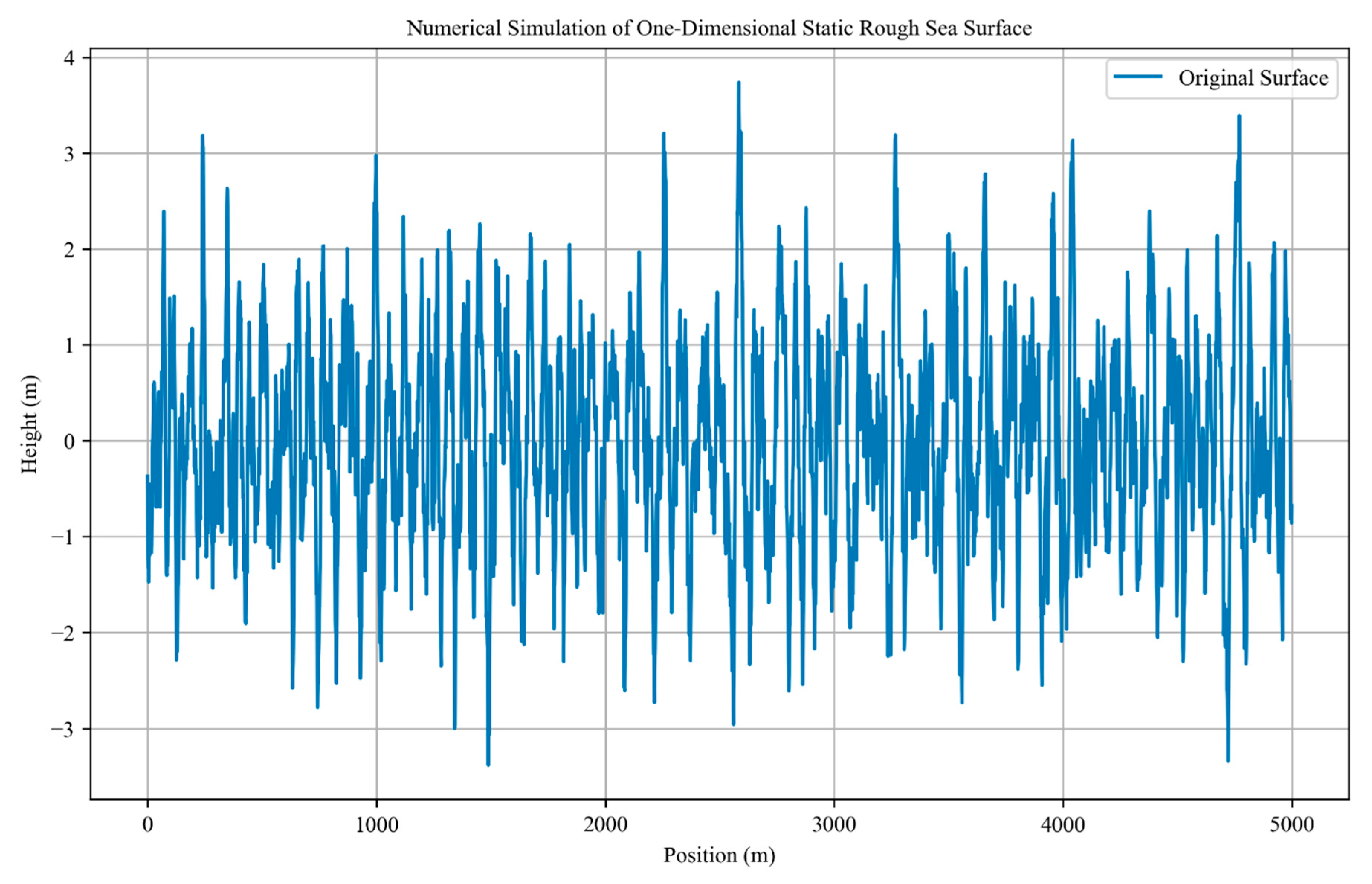

2.3. One-Dimensional Rough Sea Surface Model

Rough sea surfaces critically influence acoustic fields through repeated interactions in surface ducts, necessitating physically consistent sea surface modeling. Current methodologies are divided into two primary categories. Physics-based approaches employ linear/nonlinear wave theories to solve hydrodynamic equations, achieving high fidelity at the cost of computational complexity. Stochastic spectral methods utilize wave spectrum analysis to derive statistical wave characteristics. The sea surface elevation spectrum, defined as the Fourier transform of sea surface height correlation functions, provides measurable harmonic component distributions across wavenumbers. This capability enables efficient surface reconstruction via the Monte Carlo (linear filtering) method.

The ocean wave spectrum is defined as the Fourier transform of the spatial correlation function of sea surface height fluctuations. It quantitatively characterizes the energy distribution of harmonic wave components across the wavenumber domain. This parameter is experimentally measurable and can be obtained through field measurement techniques to capture wave spectral characteristics in specific marine regions.

Based on measured ocean wave spectra, a Monte Carlo method can be employed to reconstruct randomly rough sea surfaces. The technical workflow comprises three key steps. First, discrete spatial sampling of Gaussian white noise is performed. Second, spectral amplitude modulation is applied in the wavenumber domain. Finally, inverse Fourier transformation generates sea surface elevation profiles that satisfy the prescribed spectral properties.

The methodology offers two principal advantages. First, it ensures statistical consistency between reconstructed surfaces and real marine environments by incorporating empirical spectral constraints. Second, its numerical implementation via fast Fourier transforms (FFT) drastically reduces computational complexity, enabling real-time processing capabilities suitable for engineering applications. As a result, this approach has become a standard for sea surface modeling in both research and engineering applications.

The specific Monte Carlo formulation for 1D stochastic rough sea surface modeling is as follows[

37]:

This formulation describes a Monte Carlo-based reconstruction of 1D rough sea surfaces using discrete Fourier transforms. The surface elevation at discrete spatial points (where ) is synthesized through an inverse Fourier series summation , with representing discrete wavenumbers. The complex Fourier coefficients are generated by combining the ocean wave spectrum with Gaussian random phases: , where ϕ follows distinct statistical rules for different wavenumber indices. For non-symmetric modes (), ϕ is constructed using complex normal variables, ensuring Hermitian symmetry in the spatial domain. At symmetric wavenumbers (), real-valued Gaussian variables N(0, 1) are used instead to maintain physical consistency. This dual treatment preserves both the spectral energy distribution (via ) and the stochastic nature of sea surface fluctuations.

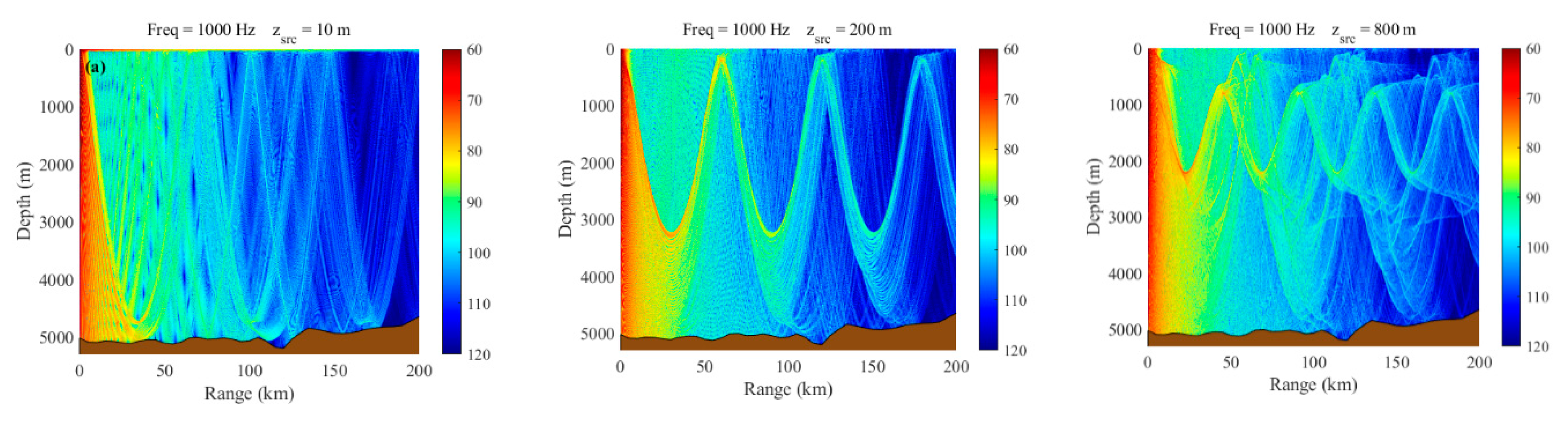

4. Sound Propagation

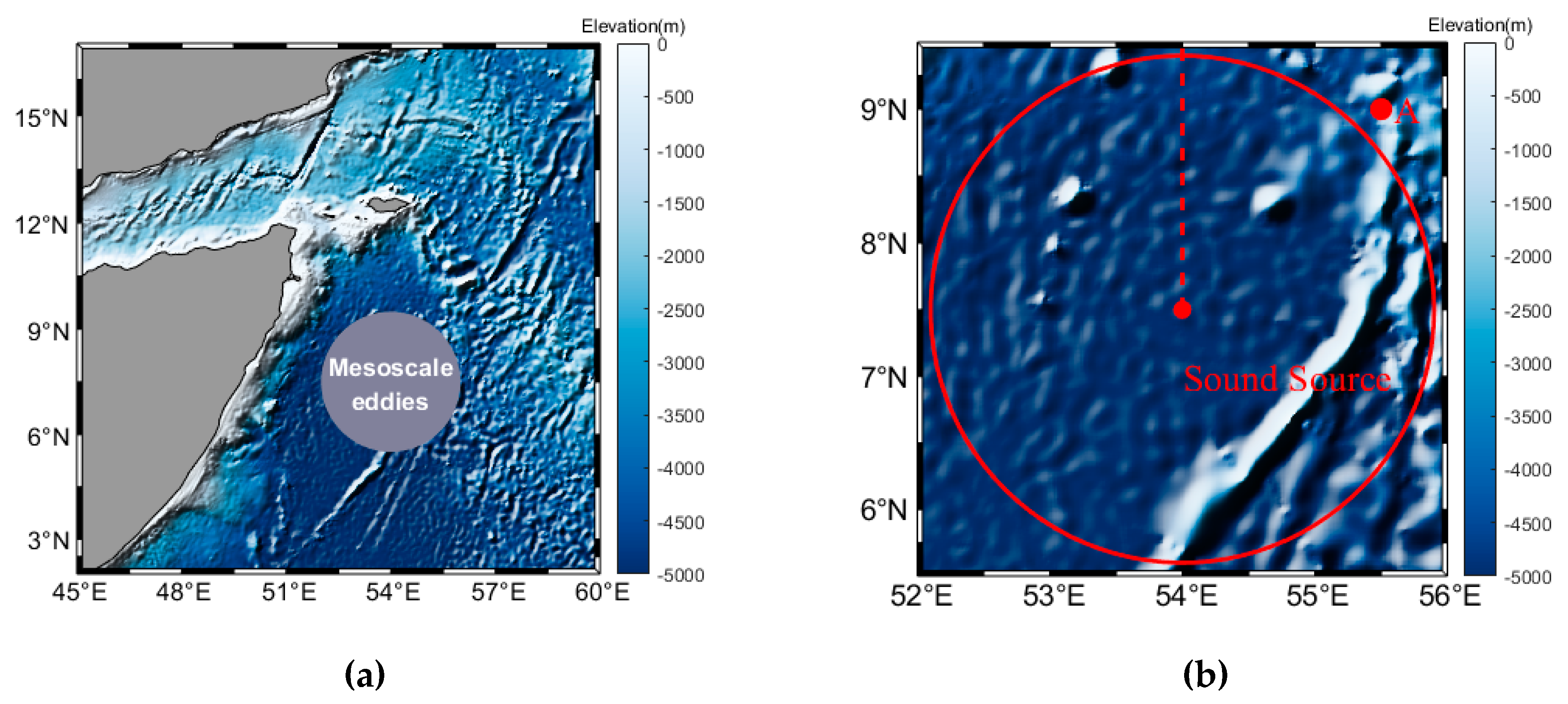

This study employs the BELLHOP acoustic model to systematically analyze the mechanisms of acoustic propagation variability under the multiphysical coupling of mesoscale eddies and rough sea surfaces, aiming to understand their combined effects on underwater sound propagation. The experimental region is centered at the core of a mesoscale eddy (7.5°N, 54°E). A circular computational domain with a radius of 200 km is constructed around it (

Figure 2a).

The seafloor topography in this region is flat, with a water depth of approximately 5303 m. This effectively reduces the impact of topographic scattering on acoustic propagation. Detailed parameter settings for the model are provided in

Table 1.

In this study, the 54°E meridian (dashed line in

Figure 2b) is selected as the cross-section for analyzing acoustic propagation characteristics due to its alignment with the mesoscale eddy core. A three-layer sound source deployment scheme is implemented to investigate the response mechanisms at different depths: 10 m depth to represent surface duct propagation, 200 m depth to examine the formation mechanisms of convergence zones, and 800 m depth to analyze the propagation patterns of the deep sound channel [

40].

The experimental design includes four comparative scenarios (

Table 2):

1.Baseline scenario: A static sea surface and homogeneous water body.

2.Pure eddy scenario: Retains only the mesoscale eddy's temperature and salinity structures.

3.Pure roughness scenario: Combines a wind-wave field described by the PM spectrum with a flat-bottom topography.

4.Fully coupled scenario: Joint effects of mesoscale eddies and rough sea surfaces.

Using stratified comparisons, this study quantitatively examines three mechanisms:

1.How mesoscale eddy-induced sound speed anomalies affect the reconstruction of convergence zones.

2.How rough sea surfaces influence near-field scattering losses.

3.The nonlinear coupling effects of multi-scale marine environmental factors.

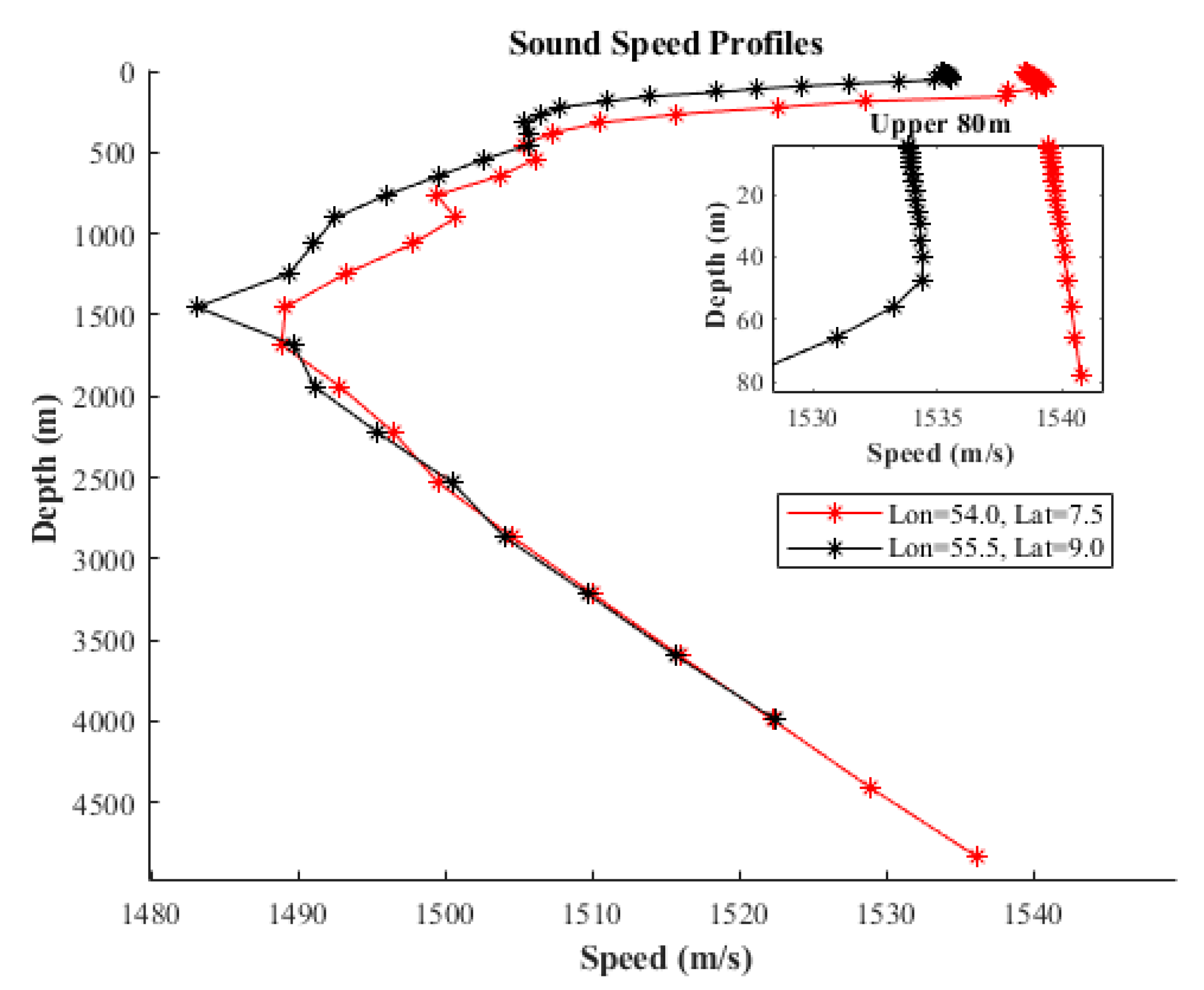

4.1. Experiment 1: Baseline Scenario

The first sub-experiment serves as the baseline scenario for comparative analysis with the other three cases, providing a reference to isolate the effects of mesoscale eddies and sea surface roughness on acoustic propagation. This sub-experiment excludes the influence of mesoscale eddies and sea surface roughness on acoustic propagation. The temperature and salinity data from point A (55.5°E, 9°N) in

Figure 2b is used as representative values for the experimental region. Additionally, the sea surface is set to a flat, calm condition to eliminate roughness effects. These conditions are then implemented in the BELLHOP model to simulate acoustic propagation in a simplified environment. A comparison of sound speed profiles between point A and the eddy center is presented in

Figure 8.

Figure 9 illustrates the transmission loss for three distinct acoustic propagation modes—surface duct propagation, convergence zone propagation, and deep sound channel propagation—along the northward direction (red dashed line) from the sound source in

Figure 2b.

When the sound source is placed at a depth of 10 m, a distinct surface duct is observed, characterized by low transmission loss due to the trapping of sound energy near the sea surface. With the sound source positioned at 200 m depth, three convergence zones appear within the 200 km propagation range, reflecting the focusing of sound energy at specific intervals due to the interaction with the mesoscale eddy's sound speed structure. When the sound source is set at 800 m depth, four convergence zones emerge within the same propagation range, demonstrating the influence of the deep sound channel on long-range acoustic propagation.

As shown in

Figure 9, the sound rays are distributed throughout the propagation region, closely interacting with the sea surface and the mesoscale eddy's thermohaline structure. These interactions highlight the complex modulation effects of the marine environment on acoustic propagation, providing a foundation for subsequent analysis of multiphysical coupling mechanisms.

4.2. Experiment 2: Pure Eddy Scenario

In this sub-experiment, the impact of mesoscale eddies on the sound speed field is exclusively investigated. The distribution of sound speed anomalies in the vertical cross-section corresponds to the spatial pattern shown in

Figure 8. To more intuitively observe the variation of acoustic transmission loss with propagation distance, one-dimensional transmission loss curves are provided for each sound source depth (

Figure 10). These curves highlight the modulation effects of mesoscale eddy-induced sound speed anomalies on acoustic propagation, providing insights into the interaction between ocean dynamics and underwater acoustics. Sz denotes the source depth, and Rz denotes the receiver depth.

Figure 10a compares the transmission loss characteristics under the influence of a mesoscale eddy with those in the baseline environment. When both the sound source and receiver are positioned at a depth of 10 m, the transmission loss curve exhibits periodic fluctuations (red curve) due to perturbations in the sound speed profile caused by the warm eddy. The fluctuation amplitude increases by approximately 5 dB compared to the baseline environment (black curve). This oscillatory behavior arises from the phase interference of sound wave propagation paths altered by the sound speed anomaly induced by the mesoscale eddy. Notably, when the propagation distance exceeds 150 km, the transmission loss under eddy influence decreases by about 3-5 dB compared to the baseline, suggesting a potential waveguide enhancement effect at this distance scale.

When the sound source and receiver are both at a depth of 200 m, the first, second, and third convergence zones shift forward by 4 km, 10 km, and 17 km, respectively, under the influence of the mesoscale eddy. The peak energy in the first and second convergence zones decreases by approximately 6 dB compared to the baseline. However, in non-convergence regions, the transmission loss under eddy influence is slightly lower than that in the baseline scenario. To investigate this phenomenon, the sound ray diagram is plotted in

Figure 11. Compared to the baseline, the sound speed gradient under the warm eddy is steeper, resulting in a smaller curvature radius of the limiting rays. This causes the convergence positions to shift forward and the turning depth to increase, reducing the number of red rays that retain most of the acoustic energy. Consequently, the transmission loss in the convergence zones increases. Some rays, after reflecting without touching the seafloor, reverse again and reach the sea surface, leaking into the shadow zone. This leads to slightly lower transmission loss in the shadow zone compared to the baseline scenario.

When both the sound source and receiver are positioned at a depth of 800 m, the convergence zones still exhibit a forward shift under the influence of the mesoscale eddy. Additionally, the number of convergence zones increases, while their characteristic features become less pronounced. This phenomenon can be attributed to the same mechanisms described earlier, where the altered sound speed gradient and reduced curvature radius of the limiting rays lead to changes in the convergence patterns and energy distribution. These observations highlight the complex interplay between mesoscale eddies and deep-sea acoustic propagation, particularly in the context of the deep sound channel.

4.3. Experiment 3: Pure Rough Sea Surface Scenario

In this experiment, the hydrological environment is maintained consistent with the baseline scenario to ensure an identical sound speed field, focusing solely on analyzing the impact of rough sea surfaces on acoustic propagation. A schematic of the rough sea surface (part) is illustrated in

Figure 6. In the BELLHOP model, the sea surface height is updated every 0.25 km. The simulation results for Experiment 1 (baseline) and Experiment 3 (rough sea surface) are presented in

Figure 12.

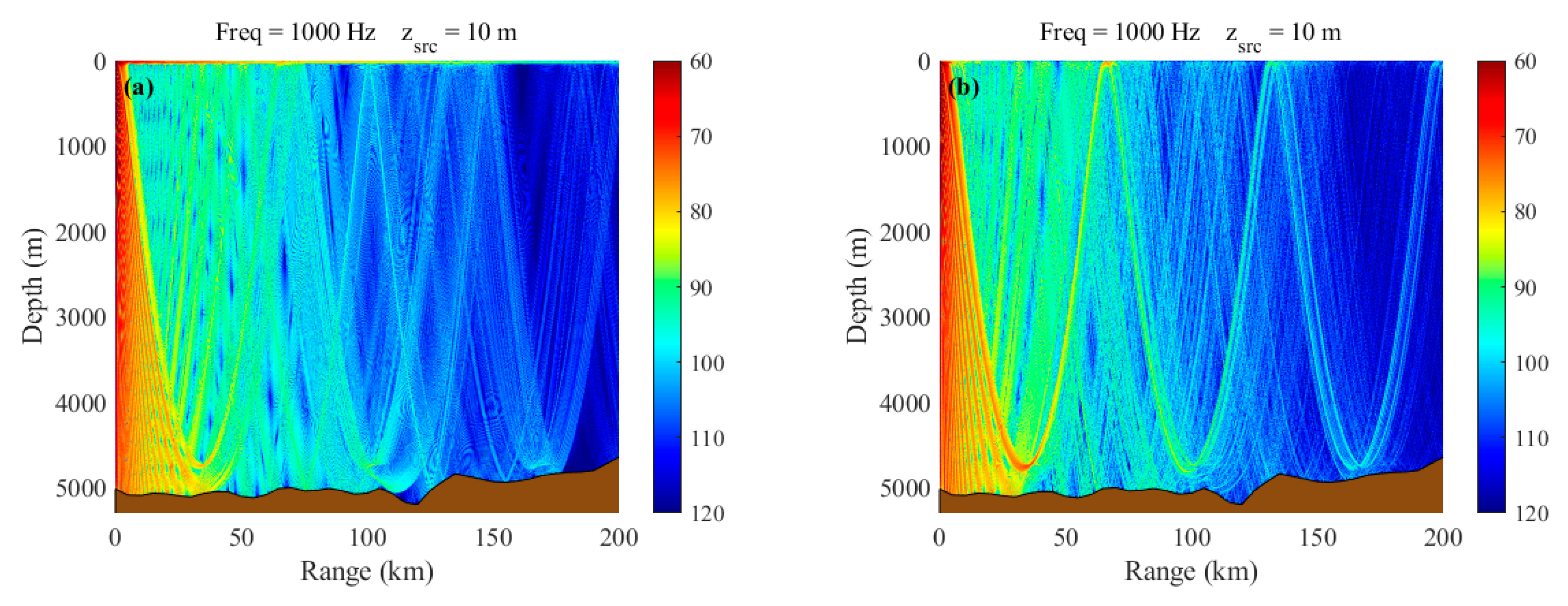

Figure 12a shows the transmission loss when the sound source is at a depth of 10 m, without considering eddies or rough sea surfaces.

Figure 12b depicts the transmission loss when only the influence of rough sea surfaces is considered. To more intuitively observe the variation of acoustic transmission loss with distance, one-dimensional transmission loss curves for the 10 m sound source depth are provided in

Figure 13.

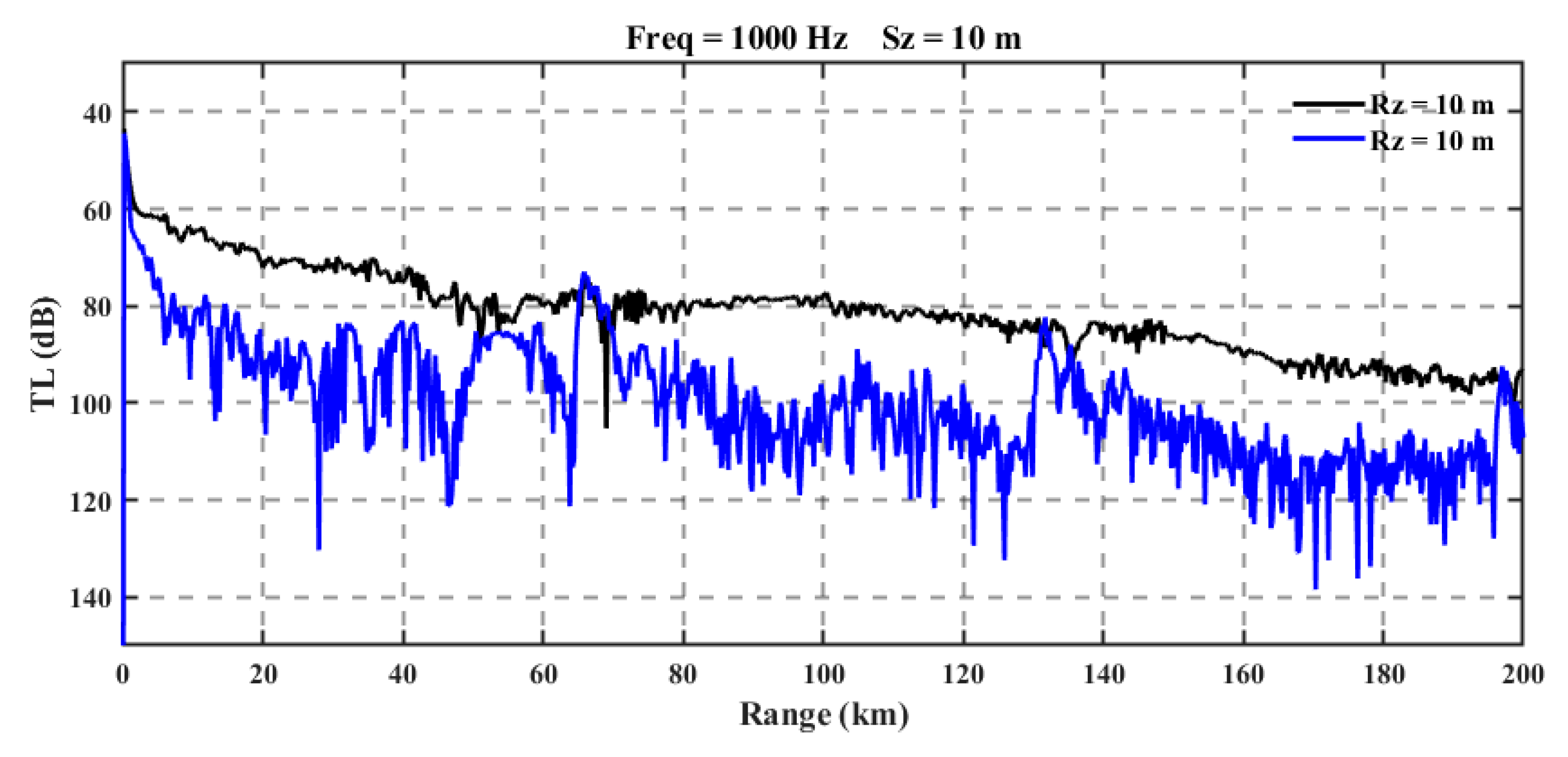

When sound waves interact with the sea surface, they follow Snell's law of refraction. Within the surface duct, the sound rays undergo continuous refraction due to the sound speed gradient, effectively confining energy within the duct and leading to significant energy accumulation in convergence zones. However, when the sea surface is rough, the interaction between sound waves and the irregular surface alters the incident angles of the rays. According to Snell's law, minor changes in the incident angle result in significant adjustments to the refraction angle. Consequently, some rays escape the surface duct due to increased refraction angles, highlighting the modulation effects of sea surface roughness on acoustic propagation.

Assuming the ray's launch angle is , the sound speed at the source location is , and the ray's turning angle at the lower boundary of the surface duct is =0° with the sound speed at the lower boundary being , Snell's law of refraction = yields = , which defines the critical angle at which the ray turns. Therefore, rays with launch angles within interact only with the sea surface and propagate within the surface duct. As the grazing angle increases, the rays no longer turn upward but instead turn downward, becoming rays that no longer interact with the sea surface. When the grazing angle continues to increase, the rays escape the surface duct and follow the convergence zone propagation pattern.

This process reduces the energy density within the surface duct and weakens the sound intensity distribution in the far-field convergence zones. The 'escaped' rays enhance the convergence zone characteristics, resulting in nearly identical peak energy levels as in Experiment 1. However, in the shadow zone, the energy difference caused by the rough sea surface is approximately 20 dB. These findings underscore the significant impact of sea surface roughness on acoustic propagation, particularly in altering energy distribution between the surface duct, convergence zones, and shadow zones.

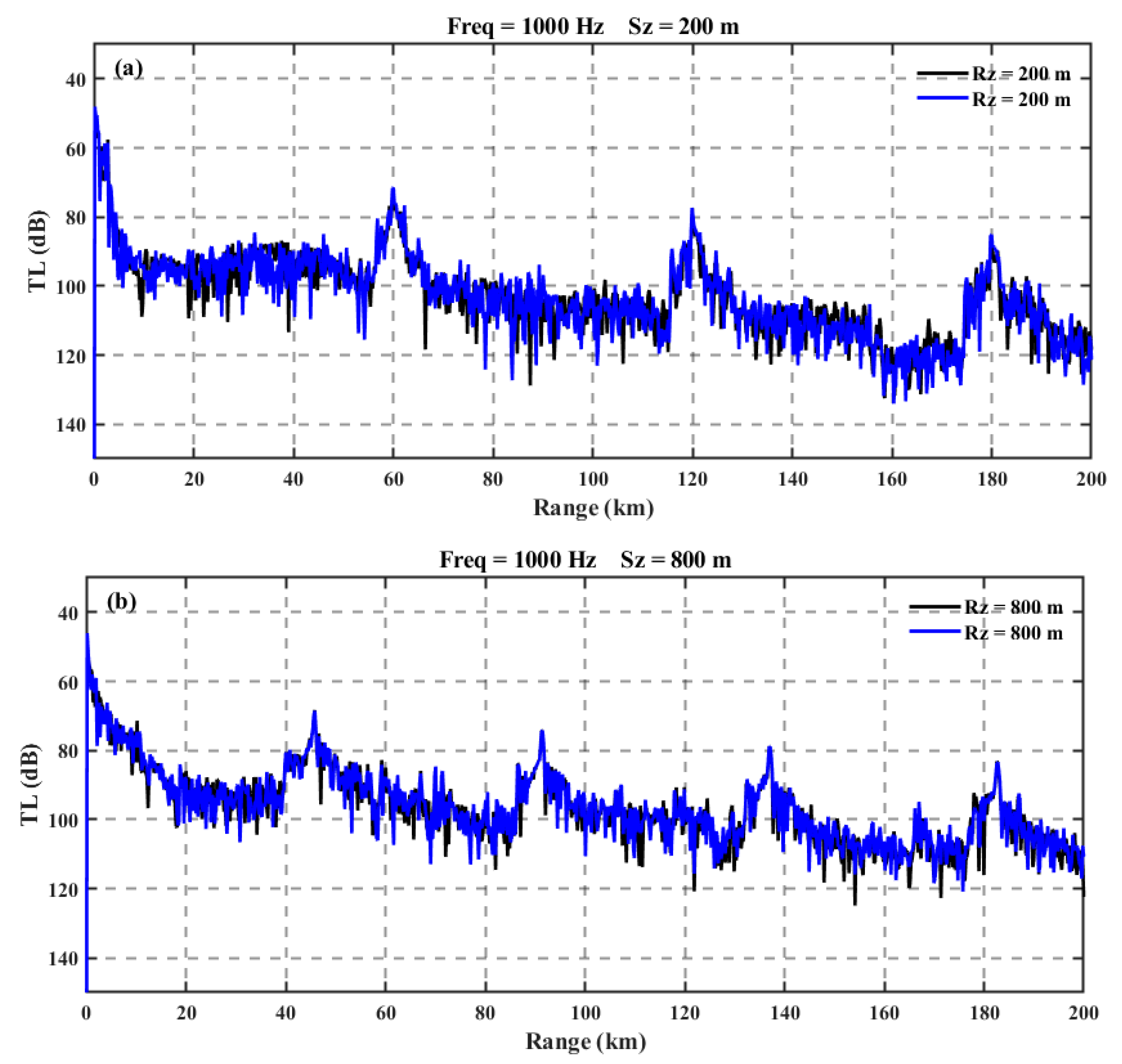

When the sound source is positioned at depths of 200 m and 800 m, and only the influence of rough sea surfaces is considered, the relationship between distance and propagation loss is illustrated in

Figure 14. The results show good agreement in both scenarios, indicating that the impact of rough sea surfaces on convergence zone propagation and deep sound channel propagation is relatively minor. This suggests that the primary effects of sea surface roughness are confined to near-surface acoustic propagation, while deeper propagation modes remain largely unaffected.

4.4. Experiment 4: Coupled Rough Sea Surface and Eddy Scenario

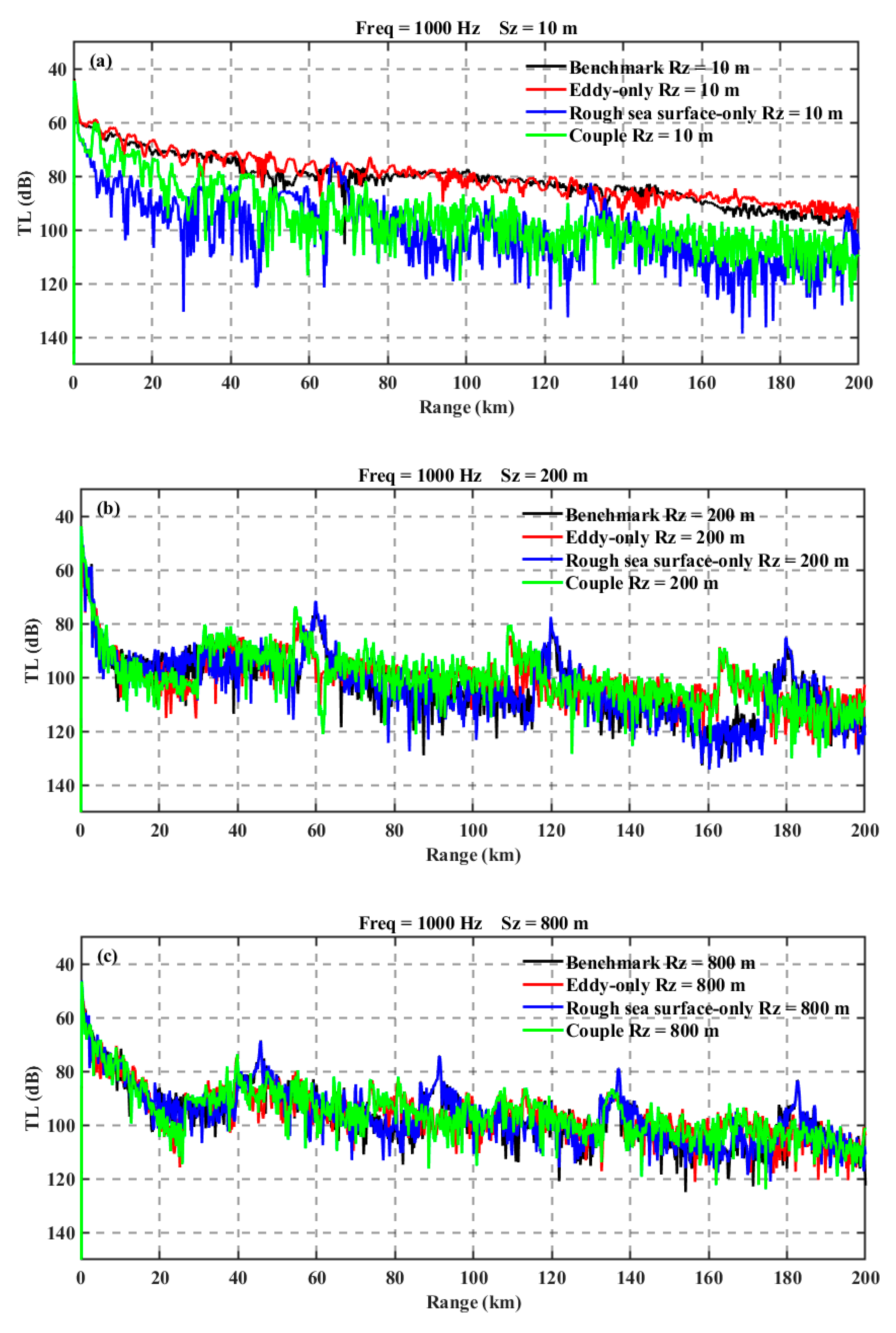

In this experiment, the sound speed field is derived from CMEMS hydrological data combined with empirical formulas, while the upper boundary for acoustic propagation is obtained using the SWAN wave model to generate the wave spectrum of the target area, combined with the Monte Carlo method, representing a realistic and complex marine environment. Acoustic propagation analysis is conducted using the sound speed field and rough sea surface conditions at 00:00 on July 31. For comparative analysis, transmission loss curves at different depths are provided (

Figure 15). The black curve represents Experiment 1 (baseline), the red curve represents Experiment 2 (pure eddy), the blue curve represents Experiment 3 (pure rough sea surface), and the green curve represents Experiment 4 (coupled rough sea surface and eddy).

As shown in the figures, when the sound source is positioned at a depth of 10 m, the acoustic energy is primarily confined within the surface duct. The propagation loss is mainly influenced by the rough sea surface, while the presence of the eddy slightly reduces the propagation loss and weakens the convergence zone characteristics. This is likely because the eddy expands the depth of the surface duct, reducing the escape of sound rays and thereby increasing the acoustic energy compared to the scenario with only rough sea surfaces.

When the sound source is set at depths of 200 m and 800 m, the blue and black curves show good agreement, indicating that the rough sea surface has a minimal impact on acoustic propagation at these depths. The presence of the eddy causes the convergence zones to shift forward and reduces their peak energy, consistent with the findings in Experiment 2. When both rough sea surfaces and eddies are considered, the green and red curves exhibit good agreement, suggesting that the eddy dominates the propagation loss. Additionally, the rough sea surface stabilizes the acoustic energy, reducing fluctuations in propagation loss.

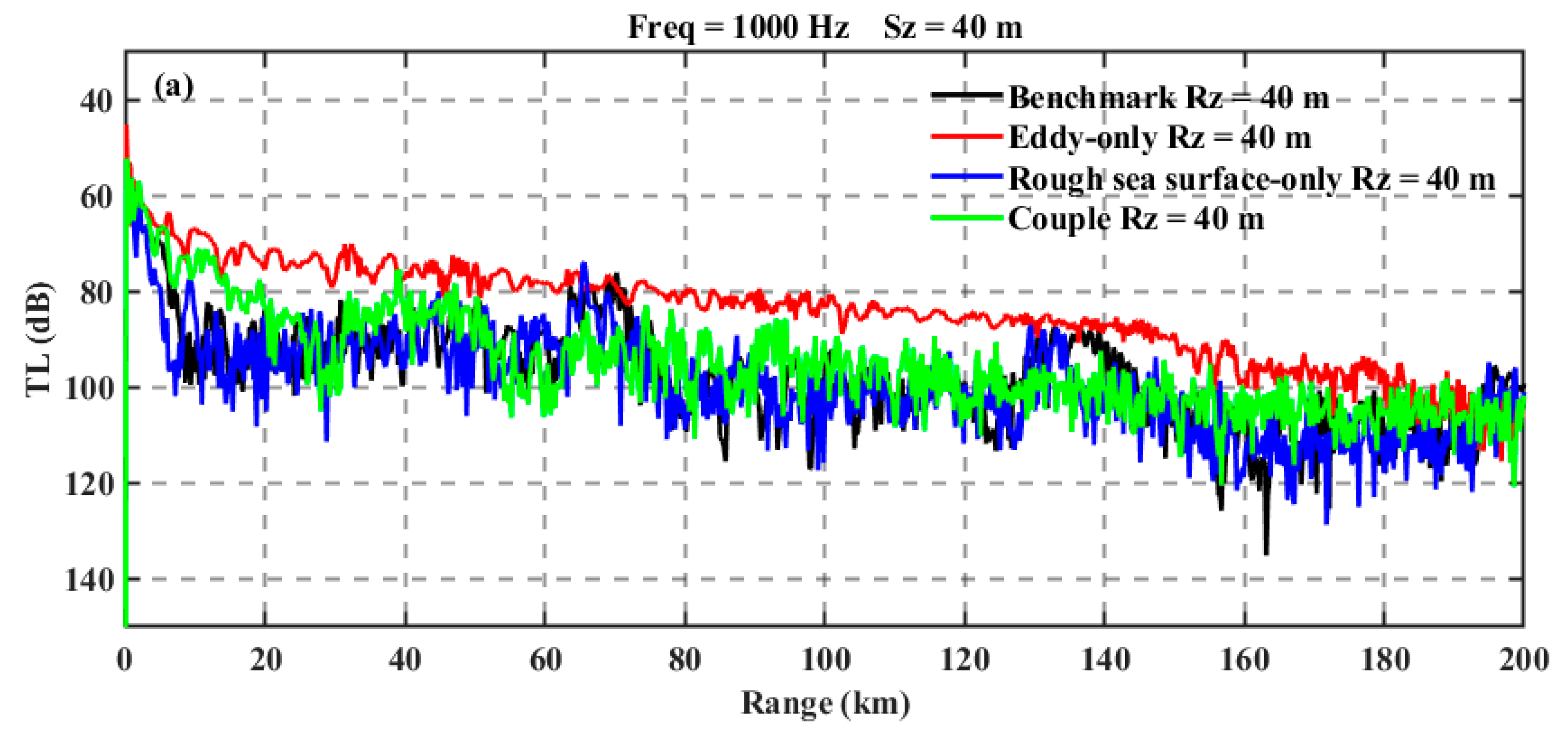

The conclusions drawn from these three scenarios are relatively general and do not clearly distinguish the boundary depth at which rough sea surfaces or eddies play a dominant role. Therefore, a supplementary experiment is designed. Considering that the influence of rough sea surfaces is closely related to the surface duct,

Figure 8 shows that the sound speed in Experiment 1 exhibits a positive gradient above 40 m and a negative gradient below 40 m. Under eddy influence, the sound speed profile maintains a positive gradient up to 80 m. Thus, the sound source in the supplementary experiment is set at a depth of 40 m. In Experiment 1, the sound rays follow the convergence zone propagation pattern, while in Experiment 2, they still adhere to the surface duct propagation rules. The resulting one-dimensional propagation loss plot is shown in

Figure 16.

In Experiment 1 (baseline), represented by the black curve, the sound rays are not confined to the surface duct, resulting in distinct convergence zones and shadow zones.

In Experiment 2 (pure eddy), represented by the red curve, the higher sea surface temperature expands the range of the surface duct, confining most of the acoustic energy within it. As a result, the sound ray fluctuations are relatively smooth, with a gradual decrease in propagation loss over distance. Compared to the baseline, the propagation loss shows significant differences.

In Experiment 3 (pure rough sea surface), represented by the blue curve, prominent convergence zones and shadow zones still exist. However, the convergence zones shift forward by approximately 5 km compared to Experiment 1, while the peak energy remains unchanged. This phenomenon may be related to the excessive refraction of sound rays caused by the rough sea surface. It indicates that rough sea surfaces not only affect the propagation mechanisms within the surface duct but also influence sound rays in shallow water that follow the convergence zone propagation pattern.

When both rough sea surfaces and eddies are considered (Experiment 4), represented by the green curve, the overall acoustic energy increases compared to Experiment 3, and the convergence zone characteristics are weakened. This is consistent with the earlier explanation that the warm eddy expands the surface duct, concentrating the acoustic energy. The significant difference between the red and green curves is due to the destruction of the surface duct by the rough sea surface, causing sound rays to 'escape' and reducing the energy in the green curve. Compared to the black curve, the blue curve shows a partial forward shift, indicating that when the sound source is in shallow water and follows the convergence zone propagation pattern, rough sea surfaces still have an impact, albeit much smaller than their effect on the surface duct.

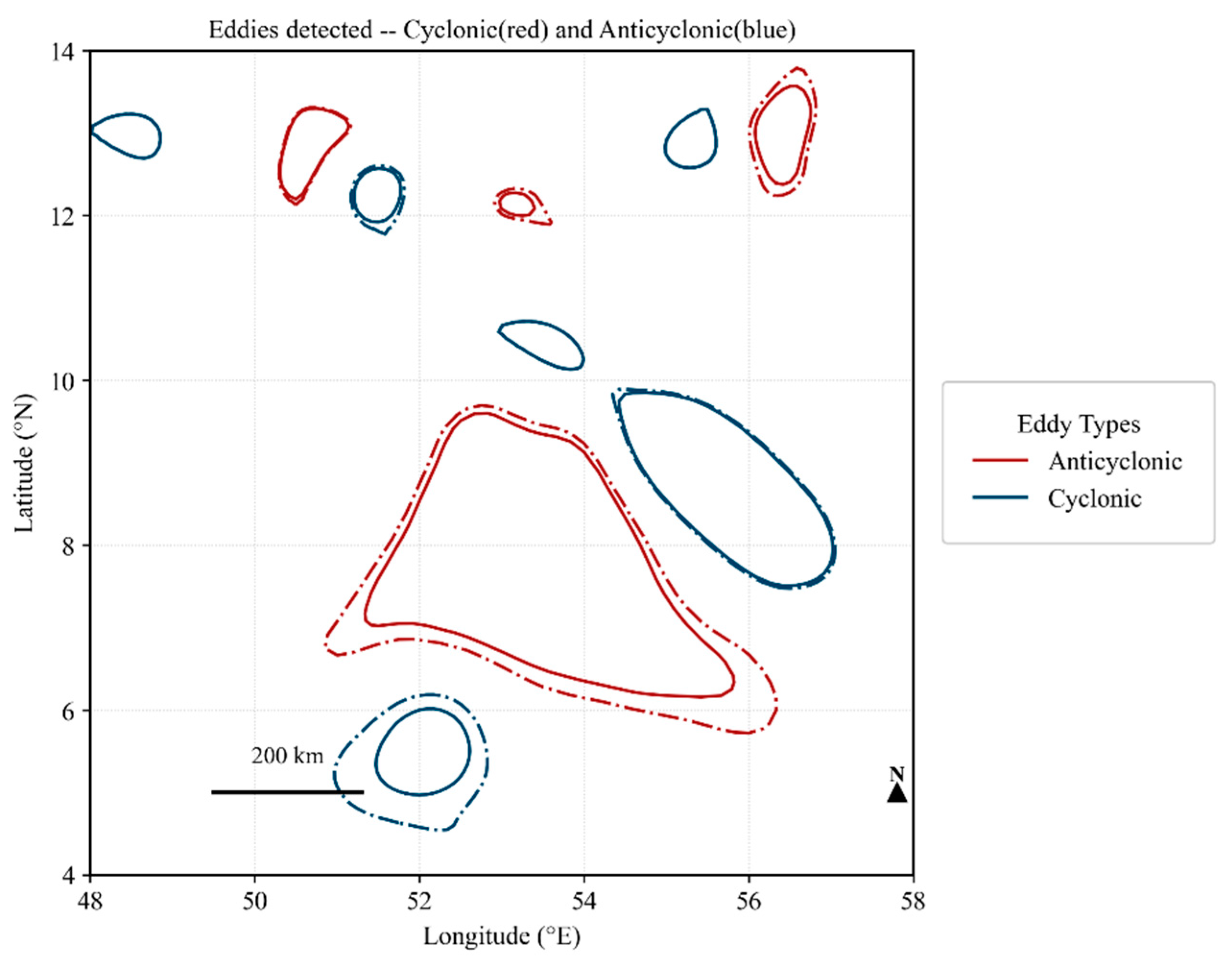

Figure 1.

Eddy Identification.

Figure 1.

Eddy Identification.

Figure 2.

experimental location. (a) is the Arabian Sea east of the Gulf of Aden, while (b) is the experimental Sea area.

Figure 2.

experimental location. (a) is the Arabian Sea east of the Gulf of Aden, while (b) is the experimental Sea area.

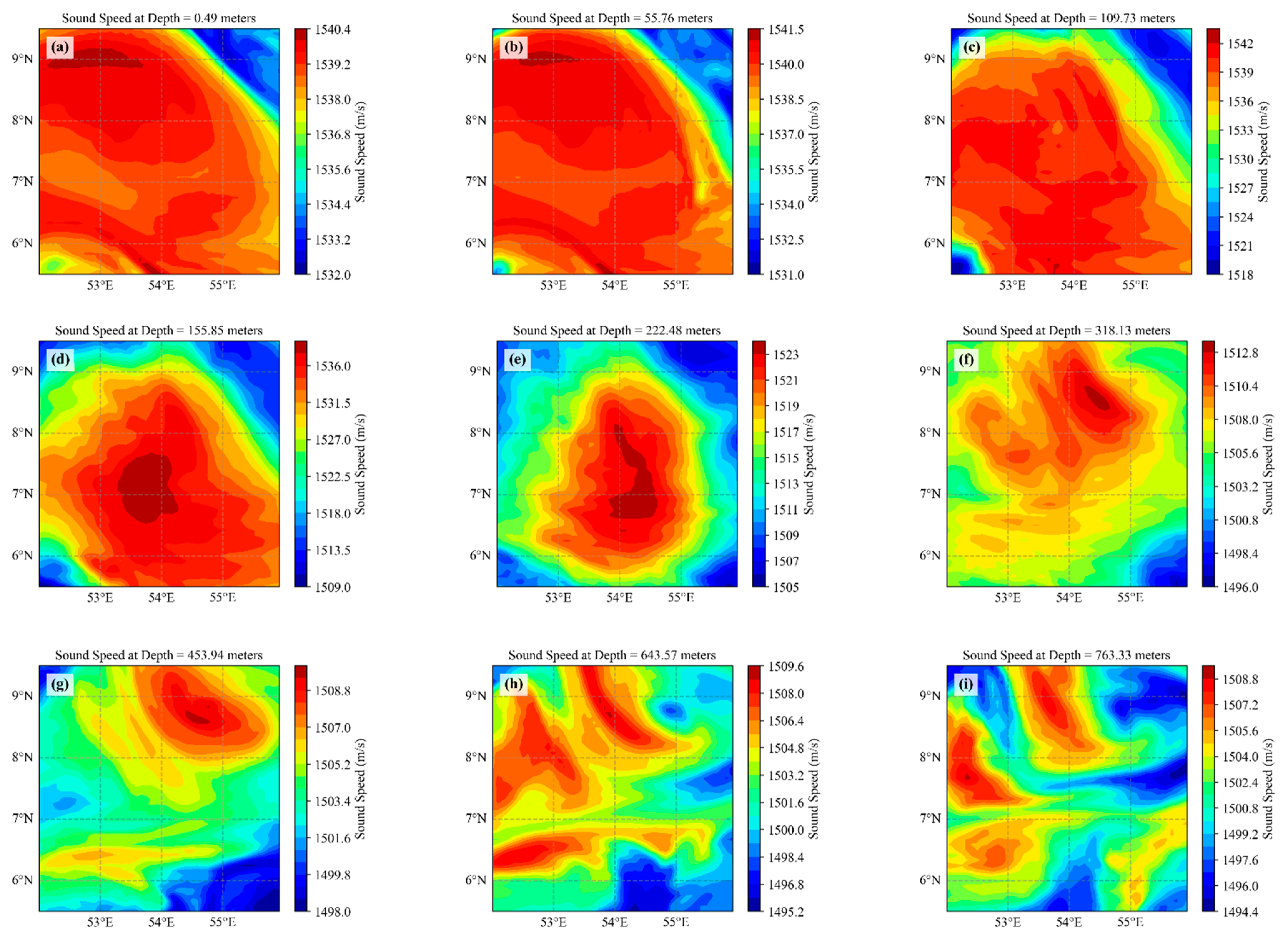

Figure 3.

Eddy Acoustic Velocity Field. (a)-(i) represent the distribution of sound velocity at different depths.

Figure 3.

Eddy Acoustic Velocity Field. (a)-(i) represent the distribution of sound velocity at different depths.

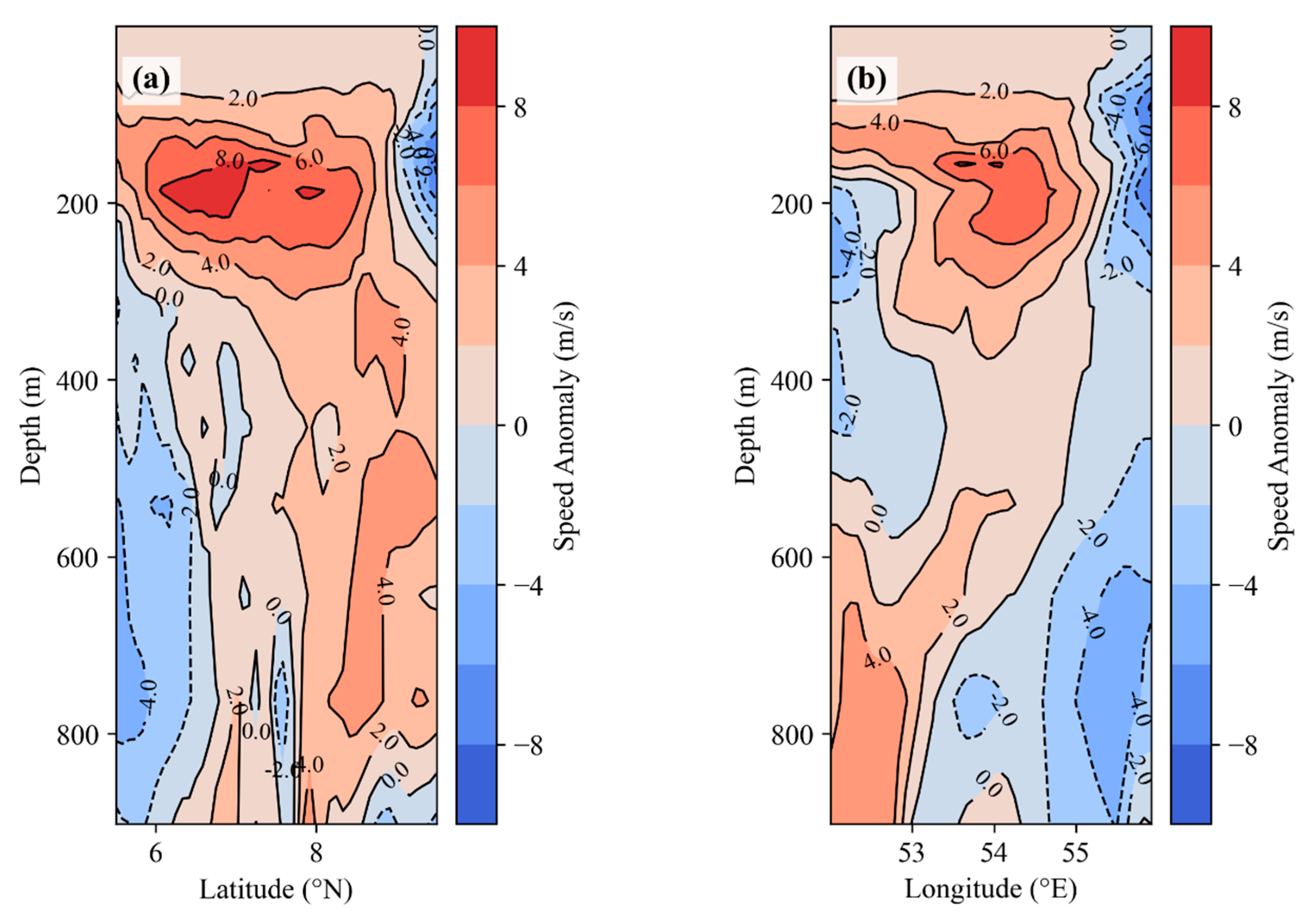

Figure 4.

Figure 4. (a) Abnormal distribution of sound speed along 54° E. (b) Abnormal distribution of sound speed along 7.5° N.

Figure 4.

Figure 4. (a) Abnormal distribution of sound speed along 54° E. (b) Abnormal distribution of sound speed along 7.5° N.

Figure 5.

SWAN-Derived Significant Wave Heights and Strategic Deployment of Directional Wave Spectra Sensors.

Figure 5.

SWAN-Derived Significant Wave Heights and Strategic Deployment of Directional Wave Spectra Sensors.

Figure 6.

Numerical Simulation of One-Dimensional Static Rough Sea Surface.

Figure 6.

Numerical Simulation of One-Dimensional Static Rough Sea Surface.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Jason-3, SWAN, and PM Spectrum Results.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Jason-3, SWAN, and PM Spectrum Results.

Figure 8.

Comparative Analysis of Sound Velocity Profiles Within and Outside the Eddy Core.

Figure 8.

Comparative Analysis of Sound Velocity Profiles Within and Outside the Eddy Core.

Figure 9.

Propagation Loss Profiles at Three Depths Under Baseline Conditions.; (a) Surface duct; (b) Convergence zone; (c) Deep SOFAR.

Figure 9.

Propagation Loss Profiles at Three Depths Under Baseline Conditions.; (a) Surface duct; (b) Convergence zone; (c) Deep SOFAR.

Figure 10.

Depth-Dependent Propagation Loss Analysis in Experiment 2. (a) at 10m south depth; (b) at 200m south depth; (c) at 800m south depth;.

Figure 10.

Depth-Dependent Propagation Loss Analysis in Experiment 2. (a) at 10m south depth; (b) at 200m south depth; (c) at 800m south depth;.

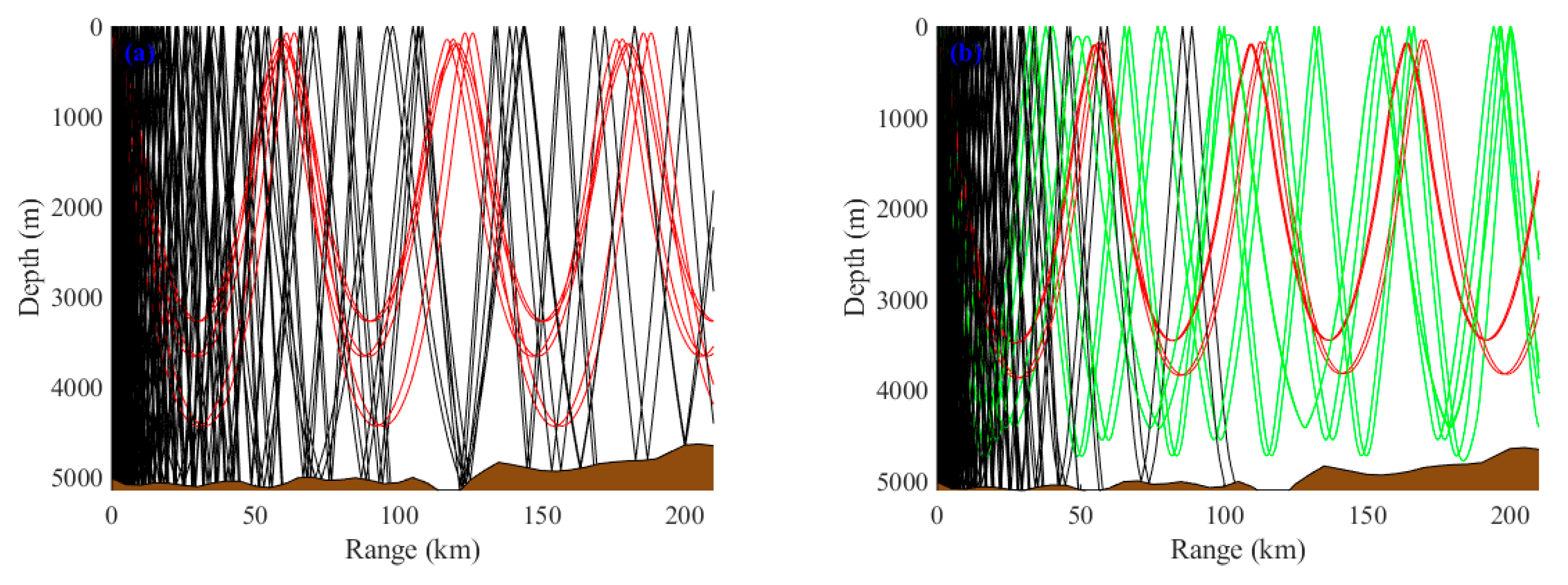

Figure 11.

Ray Path Analysis of Convergence Zone Propagation Mechanisms. (a) Ray Distribution Patterns Under Baseline Condition; (b) Ray Distribution Patterns Modulated by Eddies.

Figure 11.

Ray Path Analysis of Convergence Zone Propagation Mechanisms. (a) Ray Distribution Patterns Under Baseline Condition; (b) Ray Distribution Patterns Modulated by Eddies.

Figure 12.

Experimental Observations of Transmission Loss at 10 Meters Depth. (a) TL under baseline condition; (b) TL under rough sea surface condition.

Figure 12.

Experimental Observations of Transmission Loss at 10 Meters Depth. (a) TL under baseline condition; (b) TL under rough sea surface condition.

Figure 13.

Comparative Analysis of Horizontal Transmission Loss at 10m Source Depth Between Experiment 1 and 3.

Figure 13.

Comparative Analysis of Horizontal Transmission Loss at 10m Source Depth Between Experiment 1 and 3.

Figure 14.

Comparative vertical profiling of transmission loss between Experiment 1 and 3. (a) at 200m south depth; (b) at 800m south depth.

Figure 14.

Comparative vertical profiling of transmission loss between Experiment 1 and 3. (a) at 200m south depth; (b) at 800m south depth.

Figure 15.

Comparison of Underwater Sound Propagation Loss in Four Distinct Experimental Conditions. (a) at10m south depth; (b) at 200m south depth; (c) at 800m south depth.

Figure 15.

Comparison of Underwater Sound Propagation Loss in Four Distinct Experimental Conditions. (a) at10m south depth; (b) at 200m south depth; (c) at 800m south depth.

Figure 16.

Mechanistic Transition at 40m Source Depth: Comparative Analysis of Acoustic Propagation Modes Across Four Experimental Conditions.

Figure 16.

Mechanistic Transition at 40m Source Depth: Comparative Analysis of Acoustic Propagation Modes Across Four Experimental Conditions.

Table 1.

Key Parameter Matrix for Underwater Sound Propagation.

Table 1.

Key Parameter Matrix for Underwater Sound Propagation.

| Parameter |

Value |

Physical Implication |

| Source Frequency |

1 kHz |

high frequency sound wave |

| Source Depths |

10/200/800 m |

Surface duct/Convergence zone/Deep SOFAR |

| Bottom Density |

1.3 g/cm³ |

Sandy sediment characteristics |

| Bottom Sound Speed |

1600 m/s |

Geoacoustic inversion results |

| Attenuation Coefficient |

0.6 dB/λ |

High-frequency scattering loss |

Table 2.

Set-up of the four sound propagation experiments.

Table 2.

Set-up of the four sound propagation experiments.

| Sub-Experiment |

With Eddy |

With Tide |

Purpose |

| Baseline |

F |

F |

Reference for the following experiments |

| Pure eddy |

T |

F |

Study the effect of eddy only without rough sea surface |

| Pure roughness |

F |

T |

Study the effect of rough sea surface only without eddy |

| Couple |

T |

T |

Study the effect of eddy coupled with rough sea surface |