Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

27 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

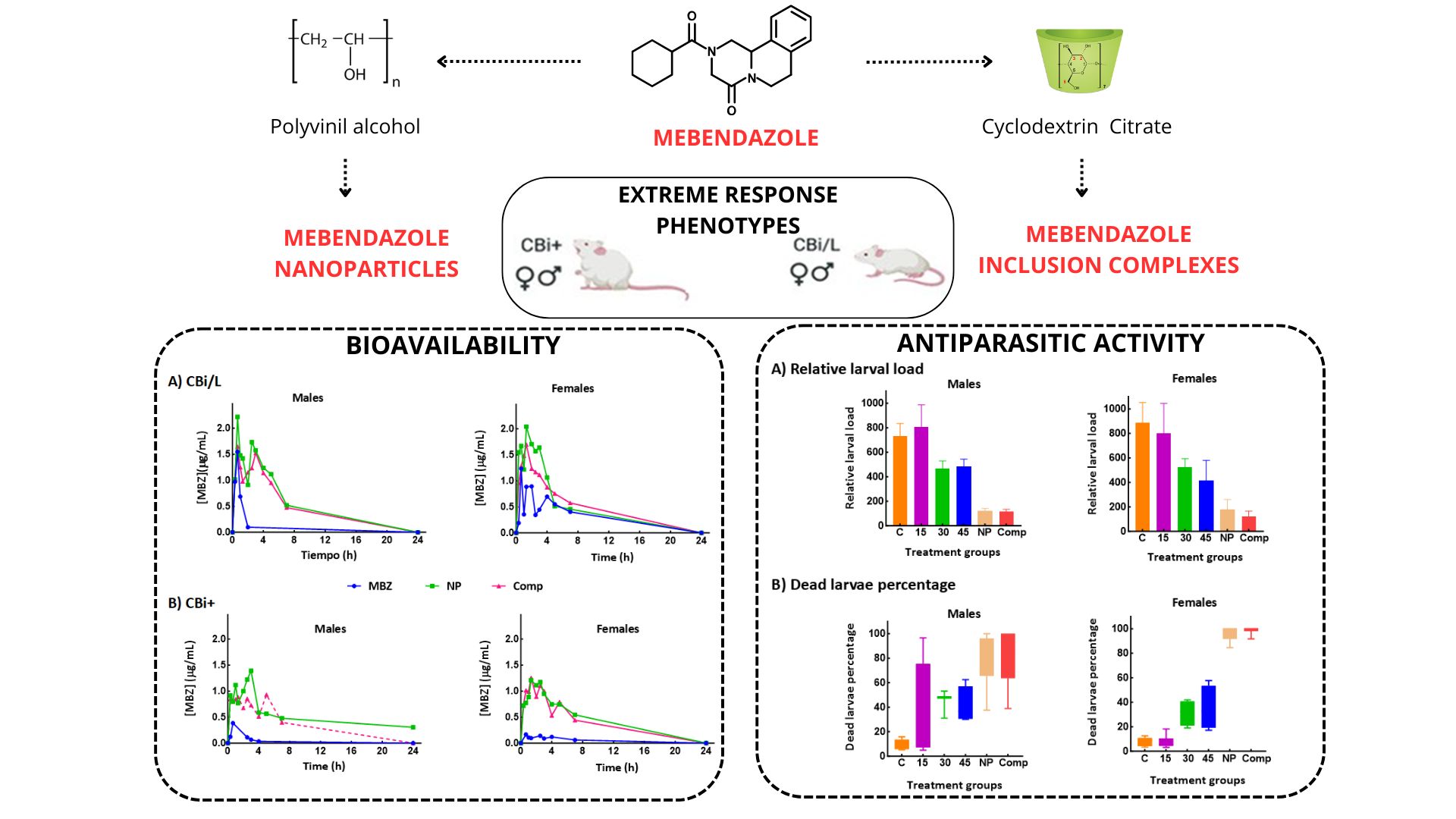

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Nanoparticle synthesis

2.3. β-cyclodextrin citrate and inclusion complexes synthesis

2.4. Particle Size Determination

2.5. Solubility and Dissolution Studies

2.6. Animal model

2.7. Parasite

2.8. In vitro analysis of the anthelmintic activity of the MBZ formulations

2.5.1. Preparation of T. spiralis female worms

2.8.2. Preparation of the antiparasitic solutions

2.8.3. In vitro assay

2.9. Pharmacokinetic analysis

2.9.1. HPLC analysis

2.9.2. Pharmacokinetic parameters

2.10. In vivo analysis of the anthelmintic activity of pure MBZ and its formulations

2.10.1. Infection

2.10.2. Assessment of the new formulations’ therapeutic efficacy

2.10.3. Assessment of increasing doses of pure MBZ on its therapeutic efficacy

2.11. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Particle Size, Solubility, and Dissolution Studies

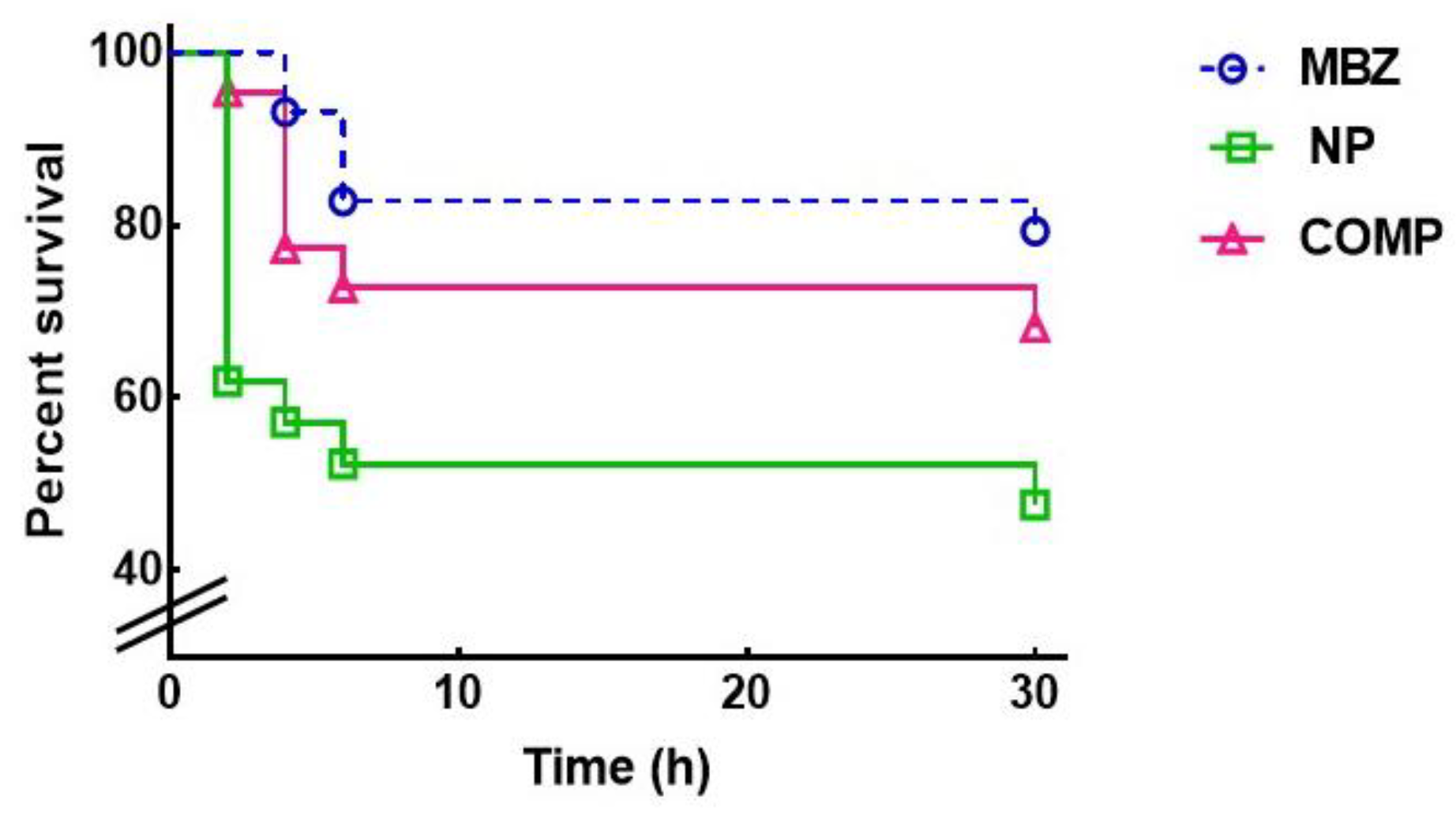

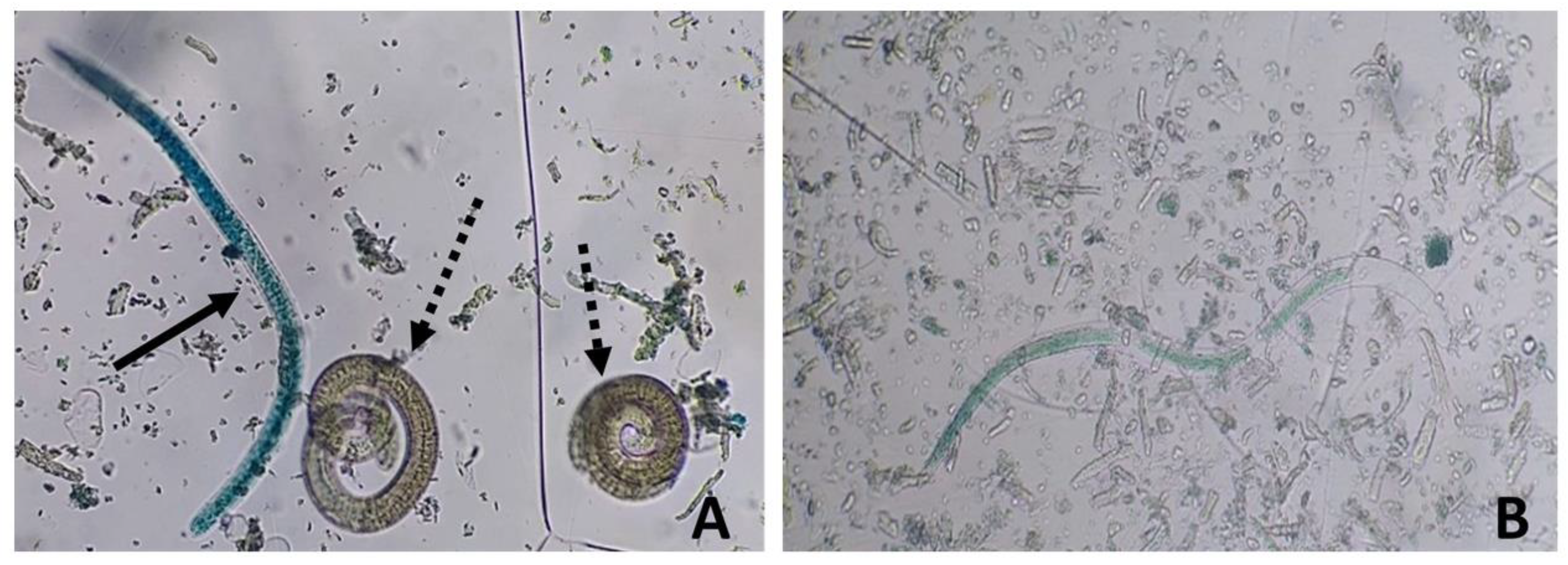

3.2. In vitro assay

3.3. Pharmacokinetic analysis

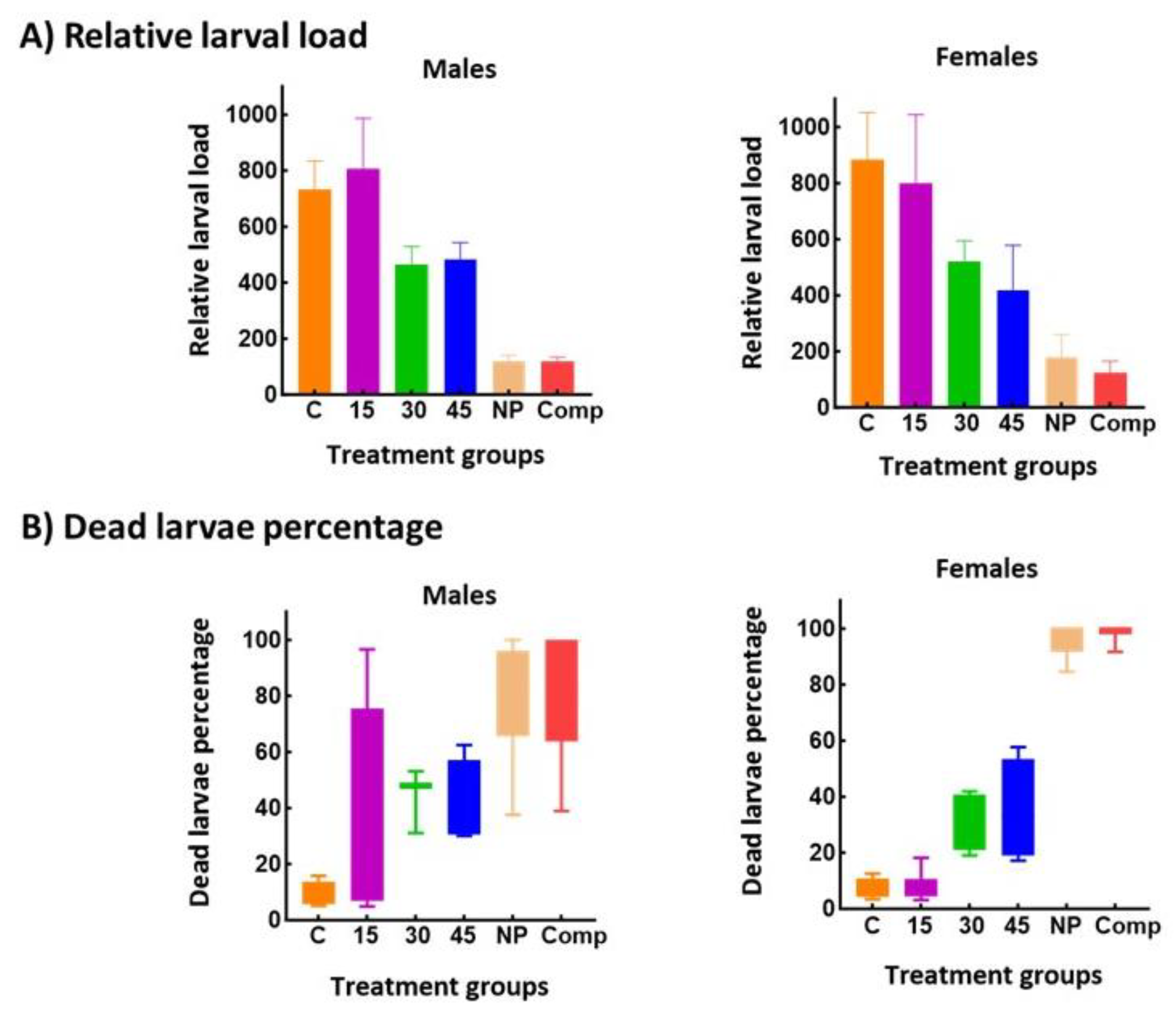

3.4. In vivo anthelmintic activity of MBZ formulations

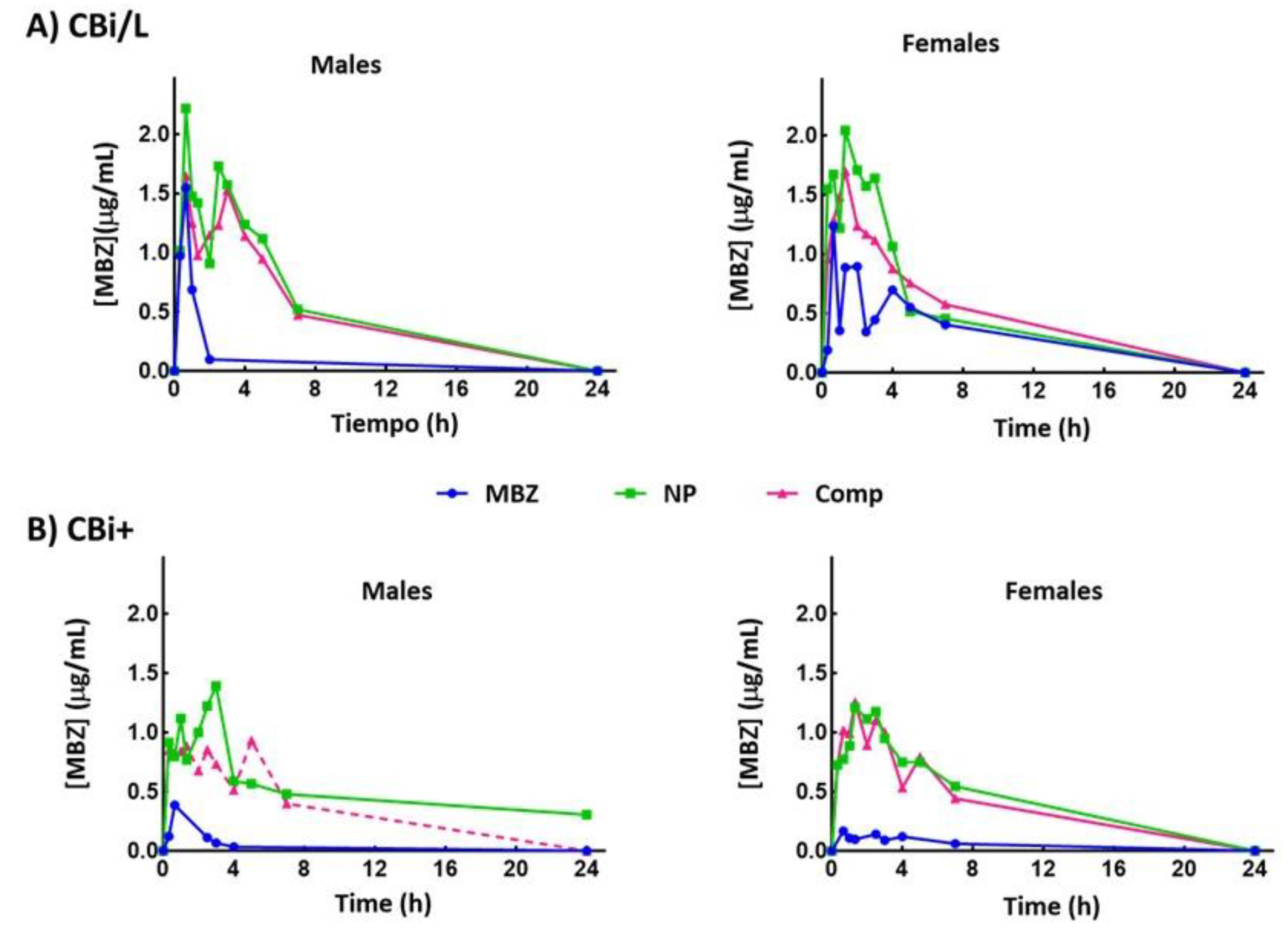

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Declaration of competing interest

References

- Sun, Z.S.; Wan, E.Y.; Agbana, Y.L.; Zhao, H.Q.; Yin, J.X.; Jiang, T.G.; Li, Q.; Fei, S.W.; Wu, L.B.; Li, X.C.; et al. Global One Health Index for Zoonoses: A Performance Assessment in 160 Countries and Territories. iScience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos, L.M.; Farina, J.; Liendro, M.C.; Saldarriaga, C.; Liprandi, A.S.; Wyss, F.; Mendoza, I.; Baranchuk, A. Neglected Tropical Diseases and Other Infectious Diseases Affecting the Heart. The NET-Heart Project: Rationale and Design. Glob Heart 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilska-Zając, E.; Thompson, P.; Rosenthal, B.; Różycki, M.; Cencek, T. Infection, Genetics, and Evolution of Trichinella: Historical Insights and Applications to Molecular Epidemiology. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2021, 95, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, L.; Biswas, N. Host Immune Responses against Parasitic Infection. Viral, Parasitic, Bacterial, and Fungal Infections: Antimicrobial, Host Defense, and Therapeutic Strategies. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A.; Gamble, H.R.; Dupouy-Camet, J.; Khazan, H.; Bruschi, F. Meat Sources of Infection for Outbreaks of Human Trichinellosis. Food Microbiol 2017, 64, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, F.; Murrell, K.D. Trichinellosis. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases. [CrossRef]

- Calcagno, M.A.; Bourlot, I.; Taus, R.; Saracino, M.P.; Venturiello, S.M. Description of an Outbreak of Human Trichinellosis in an Area of Argentina Historically Regarded as Trichinella-Free: The Importance of Surveillance Studies. Vet Parasitol 2014, 200, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis Muñoz-Carrillo, J.; Maldonado-Tapia, C.; López- Luna, A.; Jesús Muñoz-Escobedo, J.; Armando Flores-De La Torre, J.; Moreno-García, A. Current Aspects in Trichinellosis. Parasites and Parasitic Diseases 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, L.J. Parasites in Food: From a Neglected Position to an Emerging Issue. Adv Food Nutr Res 2018, 86, 71–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, C.M. Treatment. Trichinella and Trichinellosis 2021, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Priotti, J.; Codina, A.V.; Vasconi, M.D.; Quiroga, A.D.; Hinrichsen, L.I.; Leonardi, D.; Lamas, M.C. Synthesis and Characterization of a New Cyclodextrin Derivative with Improved Properties to Design Oral Dosage Forms. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2019, 9, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priotti, J.; Codina, A. V.; Leonardi, D.; Vasconi, M.D.; Hinrichsen, L.I.; Lamas, M.C. Albendazole Microcrystal Formulations Based on Chitosan and Cellulose Derivatives: Physicochemical Characterization and In Vitro Parasiticidal Activity in Trichinella Spiralis Adult Worms. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, F.O.; Ghanem, R.; Al-Sou’od, K.A.; Alsarhan, A.; Abuflaha, R.K.; Bodoor, K.; Assaf, K.I.; El-Barghouthi, M.I. Investigation of Spectroscopic Properties and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Interaction of Mebendazole with β-Cyclodextrin. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 2021, 18, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, K.M.; Good, B.; Hanrahan, J.P.; McCabe, M.S.; Cormican, P.; Sweeney, T.; O’Connell, M.J.; Keane, O.M. Transcriptional Profiling of the Ovine Abomasal Lymph Node Reveals a Role for Timing of the Immune Response in Gastrointestinal Nematode Resistance. Vet Parasitol 2016, 224, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRae, K.M.; Good, B.; Hanrahan, J.P.; Glynn, A.; O’Connell, M.J.; Keane, O.M. Response to Teladorsagia Circumcincta Infection in Scottish Blackface Lambs with Divergent Phenotypes for Nematode Resistance. Vet Parasitol 2014, 206, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRae, K.M.; McEwan, J.C.; Dodds, K.G.; Gemmell, N.J. Signatures of Selection in Sheep Bred for Resistance or Susceptibility to Gastrointestinal Nematodes. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Silva, J.R.; Neves, R.H.; Da Silva, L.O.; De Oliveira, R.M.F.; Da Silva, A.C. Do Mice Genetically Selected for Resistance to Oral Tolerance Provide Selective Advantage for Schistosoma Mansoni Infection? Exp Parasitol 2005, 111, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurwitz, D.; McLeod, H.L. Genome-Wide Studies in Pharmacogenomics: Harnessing the Power of Extreme Phenotypes. Pharmacogenomics 2013, 14, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchter, V.; Priotti, J.; Leonardi, D.; Lamas, M.C.; Keiser, J. Preparation, Physicochemical Characterization and In Vitro and In Vivo Activity Against Heligmosomoides Polygyrus of Novel Oral Formulations of Albendazole and Mebendazole. J Pharm Sci 2020, 109, 1819–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Leonardi, D.; Salazar, M.O.; Lamas, M.C. Modified β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex to Improve the Physicochemical Properties of Albendazole. Complete in Vitro Evaluation and Characterization. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.S.; Lee, S.E.; Ng, C.L.; Kim, J.K.; Park, J.S. Exploring the Preparation of Albendazole-Loaded Chitosan-Tripolyphosphate Nanoparticles. Materials 2015, Vol. 8, Pages 486-498 2015, 8, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Pharmacopeia (USP) Available online:. Available online: https://www.usp.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Di Masso, R. Empleo de Un Modelo Murino Original de Argentina En La Caracterización de Fenotipos Complejos. Journal of Basic and Applied Genetics 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconi, M.D.; Bertorini, G.; Codina, A. V.; Indelman, P.; Masso, R.J. Di; Hinrichsen, L.I. Phenotypic Characterization of the Response to Infection with Trichinella Spiralis in Genetically Defined Mouse Lines of the CBi-IGE Stock. Open J Vet Med 2015, 05, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, A. V.; Priotti, J.; Leonardi, D.; Vasconi, M.D.; Lamas, M.C.; Hinrichsen, L.I. Effect of Sex and Genotype of the Host on the Anthelmintic Efficacy of Albendazole Microcrystals, in the CBi-IGE Trichinella Infection Murine Model. Parasitology 2021, 148, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codina, A. V.; García, A.; Leonardi, D.; Vasconi, M.D.; Di Masso, R.J.; Lamas, M.C.; Hinrichsen, L.I. Efficacy of Albendazole:β-Cyclodextrin Citrate in the Parenteral Stage of Trichinella Spiralis Infection. Int J Biol Macromol 2015, 77, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ruyck, H.; Daeseleire, E.; De Ridder, H.; Van Renterghem, R. Liquid Chromatographic-Electrospray Tandem Mass Spectrometric Method for the Determination of Mebendazole and Its Hydrolysed and Reduced Metabolites in Sheep Muscle. Anal Chim Acta 2003, 483, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Tran, P.; Choi, Y.E.; Park, J.S. Solid Dispersion of Mebendazole via Surfactant Carrier to Improve Oral Bioavailability and in Vitro Anticancer Efficacy. J Pharm Investig 2023, 53, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Leonardi, D.; Vasconi, M.D.; Hinrichsen, L.I.; Lamas, M.C. Characterization of Albendazole-Randomly Methylated-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex and in Vivo Evaluation of Its Antihelmitic Activity in a Murine Model of Trichinellosis. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randazzo, V.R.; Costamagna, S.R. [Methylene Blue Test for the Determination of Viability of Free Larvae of Trichinella Spiralis]. Rev Argent Microbiol 2010, 42, 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sheskin, D.J.; (2011) Handbook of Parametric and Non-Parametric Statistical Procedures. 5th Edition, Chapman & Hall/CRC, London. - Search Results - PubMed Available online:. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Sheskin%2C+D.J.+%282011%29+Handbook+of+Parametric+and+Non-Parametric+Statistical+Procedures.+5th+Edition%2C+Chapman+%26+Hall%2FCRC%2C+London. (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Zheng, A. Progress in the Development of Stabilization Strategies for Nanocrystal Preparations. Drug Deliv 2021, 28, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamba, I.; Sombié, C.B.; Yabré, M.; Zimé-Diawara, H.; Yaméogo, J.; Ouédraogo, S.; Lechanteur, A.; Semdé, R.; Evrard, B. Pharmaceutical Approaches for Enhancing Solubility and Oral Bioavailability of Poorly Soluble Drugs. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2024, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Omar, T.; Zhou, Q.; Scicolone, J.; Callegari, G.; Dubey, A.; Muzzio, F. High-Dose Modified-Release Formulation of a Poorly Soluble Drug via Twin-Screw Melt Coating and Granulation. Int J Pharm 2025, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Guo, T.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liao, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, X. A Micrometer Sized Porous β-Cyclodextrin Polymer for Improving Bioavailability of Poorly Soluble Drug. Carbohydr Polym 2025, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brough, C.; Williams, R.O. Amorphous Solid Dispersions and Nano-Crystal Technologies for Poorly Water-Soluble Drug Delivery. Int J Pharm 2013, 453, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki, T.; Kusuhara, H. Progress in the Quantitative Assessment of Transporter-Mediated Drug-Drug Interactions Using Endogenous Substrates in Clinical Studies. Drug Metab Dispos 2023, 51, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Variability: A Daunting Challenge in Drug Therapy. Curr Drug Metab 2007, 8, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, L.; Qiao, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Cyclodextrin-Based Delivery Systems for Chemical and Genetic Drugs: Current Status and Future. Carbohydr Polym 2025, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Leonardi, D.; Vasconi, M.D.; Hinrichsen, L.I.; Lamas, M.C. Characterization of Albendazole-Randomly Methylated-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex and in Vivo Evaluation of Its Antihelmitic Activity in a Murine Model of Trichinellosis. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahousse, J.; Wagner, A.D.; Borchmann, S.; Adjei, A.A.; Haanen, J.; Burgers, F.; Letsch, A.; Quaas, A.; Oertelt-Prigione, S.; Oezdemir, B.C.; et al. Sex Differences in the Pharmacokinetics of Anticancer Drugs: A Systematic Review. ESMO Open 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Berthold, H.K.; Campesi, I.; Carrero, J.J.; Dakal, S.; Franconi, F.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Heiman, M.L.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Klein, S.L.; et al. Sex- and Gender-Based Pharmacological Response to Drugs. Pharmacol Rev 2021, 73, 730–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldin, O.P.; Chung, S.H.; Mattison, D.R. Sex Differences in Drug Disposition. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, E.P.; Morse, B.A.; Savk, A.; Malik, K.; Peppas, N.A.; Lanier, O.L. The Role of Patient-Specific Variables in Protein Corona Formation and Therapeutic Efficacy in Nanomedicine. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, S.; Caracciolo, G.; Pozzi, D.; Digiacomo, L.; Swann, J.; Daldrup-Link, H.E.; Mahmoudi, M. The Role of Sex as a Biological Variable in the Efficacy and Toxicity of Therapeutic Nanomedicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 174, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Lu, Y.F.; Corton, J.C.; Klaassen, C.D. Expression of Cytochrome P450 Isozyme Transcripts and Activities in Human Livers. Xenobiotica 2021, 51, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerges, S.H.; El-Kadi, A.O.S. Sexual Dimorphism in the Expression of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Rat Heart, Liver, Kidney, Lung, Brain, and Small Intestine. Drug Metab Dispos 2023, 51, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, R.; Kamataki, T. Cytochrome P-450 as a Determinant of Sex Difference of Drug Metabolism in the Rat. Xenobiotica 1982, 12, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.B. The Influence of Sex on Pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003, 42, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, T.M.; Baranek, M.; Kaka, M.; Shwani, S. Natural Drugs: Trends, Properties, and Decline in FDA Approvals. J Pharm Sci 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolsey, S.J.; Mansell, S.E.; Kim, R.B.; Tirona, R.G.; Beaton, M.D. CYP3A Activity and Expression in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2015, 43, 1484–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, J.; Hill, D.E.; Zarlenga, D.S.; Fournet, V.M.; Hawkins-Cooper, D.S.; Urban, J.F.; Kramer, M. *Inactivation of Encysted Muscle Larvae of Trichinella Spiralis in Pigs Using Mebendazole. Vet Parasitol 2024, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.A.; Chandrasekar, P.H.; Mortiere, M.; Molinari, J.A. Comparative Efficacy of Ketoconazole and Mebendazole in Experimental Trichinosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1986, 30, 953–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccracken, R.O.; Taylor, D.D. Mebendazole Therapy of Parenteral Trichinellosis. Science 1980, 207, 1220–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesołowska, A. Sex-the Most Underappreciated Variable in Research: Insights from Helminth-Infected Hosts. Vet Res 2022, 53, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredericks, J.; Hill, D.E.; Zarlenga, D.S.; Fournet, V.M.; Hawkins-Cooper, D.S.; Urban, J.F.; Kramer, M. *Inactivation of Encysted Muscle Larvae of Trichinella Spiralis in Pigs Using Mebendazole. Vet Parasitol 2024, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Rayia, D.M.; Saad, A.E.; Ashour, D.S.; Oreiby, R.M. Implication of Artemisinin Nematocidal Activity on Experimental Trichinellosis: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Parasitol Int 2017, 66, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Torre-Iglesias, P.M.; García-Rodriguez, J.J.; Torrado, G.; Torrado, S.; Torrado-Santiago, S.; Bolás-Fernández, F. Enhanced Bioavailability and Anthelmintic Efficacy of Mebendazole in Redispersible Microparticles with Low-Substituted Hydroxypropylcellulose. Drug Des Devel Ther 2014, 8, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, J.; Yanagisawa, T. Comparative Efficacy of Flubendazole and Mebendazole on Encysted Larvae of Trichinella Spiralis (USA Strain) in the Diaphragm of Mice and Rats. J Helminthol 1988, 62, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornelio, A.C.; Caabeiro, F.R.; Gonzalez, A.J. The Mode of Action of Some Benzimidazole Drugs on Trichinella Spiralis. Parasitology 1987, 95 ( Pt 1) Pt 1, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiting, D.P.; Bliss, S.K.; Schlafer, D.H.; Roberts, V.L.; Appleton, J.A. Interleukin-10 Limits Local and Body Cavity Inflammation during Infection with Muscle-Stage Trichinella Spiralis. Infect Immun 2004, 72, 3129–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozio, E.; Sacchini, D.; Sacchi, L.; Tamburrini, A.; Alberici, F. Failure of Mebendazole in the Treatment of Humans with Trichinella Spiralis Infection at the Stage of Encapsulating Larvae. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 32, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, F. Trichinella and Trichinellosis. 2021.

- Martinez-Fernandez, A.R.; Samartin-Duran, M.L.; Toro Rojas, M.; Ubeira, F.M.; Rodriguez Cabeiro, F. Histopathological Modifications Induced Ny Mebendazole and Niridazole on Encysted Larvae of Trichinella Spiralis in CD-1 Mice. Wiad Parazytol 1987, 33. [Google Scholar]

| Drug | Solubility in HCl 0.1 N (mg/ml) | Solubility increase (fold) | Dissolution Efficiency (%) | Dissolution Efficiency Increase (fold) |

Particle size# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBZ | 0.025 ± 0.003 | - | 20.6 ± 0.1 | - | --- |

| MBZ-NP | 0.53 ± 0.040 | 21 | 74.2 ± 0.5 | 7 | 500 nm |

| MBZ-Comp | 2.015 ± 0.009 | 81 | 87.4 ± 0.3 | 8 | 5 µm |

| Formulations | Median survival (hours) |

Survival proportion after 30 h (%) |

|---|---|---|

| MBZ a | Undefined | 79.3 |

| NP b | 30 | 47.6 |

| Comp a | Undefined | 68.2 |

| Parameter | Sex | Formulations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBZ | NP | Comp | ||

| Cmax (µg/mL) # | ♂ | 1.3 ± 0.31 a | 2.3 ± 0.28 b | 1.7 ± 0.42 a, b |

| ♀ | 1.3± 0.26 a | 2.2 ± 0.08 b | 1.7 ± 0.20 a, b | |

| Tmax (h) | ♂ | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| ♀ | 0.66 | 1.33 | 1.33 | |

| AUC0-7 h (µg.h/mL) # | ♂ | 2.7 ± 0.82 a | 8.2 ± 0.34 b | 5.1 ± 1.00 a, b |

| ♀ | 3.9 ± 0.63 a | 7.4 ± 1.16 a | 6.4 ± 1.24 a | |

| AUC0-24 h (µg.h/mL) # | ♂ | 8.4 ± 3.37 a | 12.6 ± 0.69 a | 14.1 ±2.30 a |

| ♀ | 7.2 ± 1.53 a | 11.3 ± 2.29 a | 11.1 ± 1.10 a | |

| AUCr0-7 h (%) | ♂ | --- | 204 | 88 |

| ♀ | --- | 90 | 64 | |

| AUCr0-24 h (%) | ♂ | --- | 50 | 67 |

| ♀ | --- | 57 | 54 | |

| Parameter | Sex | Formulations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBZ | NP | Comp | ||

| Cmax (µg/mL) # | ♂ | 0.3 ± 0.11 a | 1.5 ± 0.08 b | 1.1 ± 0.04 c |

| ♀ | 0.2± 0.02 a | 1.3 ± 0.09 b | 1.4 ± 0.08 b | |

| Tmax (h) | ♂ | 0.66 | 3 | 5 |

| ♀ | 0.66 | 1.33 | 1.33 | |

| AUC0-7 h (µg.h/mL) # | ♂ | 0.4 ± 0.20 a | 5.4 ± 0.18 b | 4.7 ± 0.50 b |

| ♀ | 0.6 ± 0.08 a | 5.7 ± 0.35 b | 5.3 ± 0.63 b | |

| AUC0-24 h (µg.h/mL) # | ♂ | 0.7 ± 0.33 a | 9.8 ± 2.54 b | 8.1 ± 1.13 b |

| ♀ | 1.8 ± 0.40 a | 10.1 ± 0.62 b | 9.0 ± 1.98 b | |

| AUCr0-7 h (%) | ♂ | --- | 1250 | 1175 |

| ♀ | --- | 850 | 783 | |

| AUCr0-24 h (%) | ♂ | --- | 1300 | 1057 |

| ♀ | --- | 461 | 400 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).