1. Introduction

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) have been the first-line antimalarial treatment for uncomplicated falciparum malaria since 2005 in Nigeria due to emergence of chloroquine (CQ) resistance and increased failure rate of treatment with CQ [

1]. The

Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) is largely responsible for this treatment failure and also contributes substantially to multidrug resistance. The substitution of lysine by threonine at codon 76 (K76T) in the

pfcrt gene is the most important molecular marker to monitor CQ resistance in the field [

2,

3]. CQ belongs to the 4-aminoquinoline group of antimalarials.

ACTs are a combination of one rapidly acting artemisinin derivative that is readily eliminated and a long-acting partner drug. One of the partner drugs used in ACTs is piperaquine (PPQ), a 4-aminoquinoline, partnered with dihydroartemisinin (DHA)). PPQ, like other quinoline-based antimalarials, accumulates in the parasite’s digestive vacuole, where it binds to ferriprotoporphyrin IX (free hematin) and inhibits its detoxification into hemozoin. This leads to the accumulation of toxic free hematin, which disrupts parasite metabolism and ultimately results in parasite death. [

4].

However, the increasing resistance against both artemisinin and PPQ in Southeast Asia is leading to a significant increase in therapeutic failure in patients receiving DHA-PPQ treatment in this area [

5]. Genome wide association studies have shown that PPQ resistance is strongly associated with the amplification of the aspartic proteinase genes plasmepsin 2 (

pfpm2) and plasmepsin 3 (

pfpm3) on chromosome 14 and with novel mutations in the

pfcrt gene [

6,

7]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in

pfcrt at positions downstream of the CQ resistance locus K76T, namely amino acids 72–76, T93S, H97Y, F145I, I218F, M343L, and G353V together with an amplified

pfpm2/3 majorly mediate PPQ resistance as demonstrated in recent studies [

6,

8].

Here, we assess whether these molecular markers associated with PPQ resistance—specifically, the SNPs T93S, H97Y, and F145I mutations in exons 2 and 3 of pfcrt and the increased copy number of the aspartic proteinase genes pfpm2 and pfpm3—are circulating in Nnewi Town, Southeast Nigeria, as these mutations have shown strong associations with PPQ resistance in previous studies (7). Even though the first line therapy for uncomplicated malaria in Nigeria is artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-amodiaquine, the combination of DHA-PPQ is available on the market. The addition of PPQ to combination therapy is currently being considered in Nigeria, emphasizing the need to monitor resistance markers (9). Early detection of drug-resistant parasites is crucial for timely intervention. Notably, no studies in Nigeria have investigated these specific PPQ resistance markers, making this the first effort to assess their presence in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

Study area and design

This is a cross-sectional, hospital-based study that was performed on samples collected in specific areas from Nigeria (Onitsha, Nnewi and Awka). The study design has been previously described [

10]. Whole blood was sampled from 2018 to 2019 from individuals in hospital settings located in semi-urban areas in Anambra, the state of southeastern Nigeria.

Parasite strains and clinical samples

P. falciparum 3D7 (CQ-sensitive, obtained from BEI Resources; reference number MRA-102) and RF7 (provided by Dr. David Fidock, Columbia University, NY) were used in this study. RF7 is PPQ- and DHA-resistant Cambodian clinical isolate that naturally expresses either the K13 C580Y mutation or the PfCRT Dd2 + M343L isoform [

11] with

pm2/3 multicopies (7). The parasites were maintained in O+ erythrocytes at 2.5% haematocrit in RPMI 1640 medium containing 50 µg/ml gentamicin (Gibco), 25 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.1 mM l-Glutamine (Gibco), and 0.5% (wt/vol) AlbuMAX II (Life technologies) containing 73 µM hypoxanthine and 1.9 mM sodium bicarbonate [

12].

P. falciparum positive samples from the Anambra State, Southeast Nigeria were obtained from participating patients at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (Nnewi, Nigeria) as described in a previous publication [

10]. Briefly, patients presenting with at least one of the following symptoms: fever (≥ 37.5°C), headache, vomiting, or malaise between February 2018 and January 2019 at Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital in Nnewi, Anambra State, southeastern Nigeria, were invited to be included in the study. A total of 268 patients with an average age of 16 years were included, comprising 113 males and 155 females.

DNA Extraction and Amplification of exon 2 and 3 of pfcrt

DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (250) (Qiagen). DNA yield was quantified using a Nanospec 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific USA). Amplification of exon 2 of

pfcrt, containing T93S and H97Y loci, and exon 3 of

pfcrt, containing F145I locus, was carried out by PCR in a Master Cycler Nexus Gradient (Eppendorf, US) in 25 μl reaction mixture containing 2.5 μl of 10x Coral Load PCR buffer, 0.8 μl of 25 mM MgCl

2, 0.5 μl of each of the 10 mM forward and reverse primer, 0.5 μl of 10 mM dNTPs, 0.2 μl Taq DNA Polymerase (5 units/μL) and 19 μl of nuclease free water. The primers used were published in a previous study [

13] (Supplementary file 1). Cycling conditions were initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 53°C for 45 s and elongation at 60°C for 45 s. A final elongation was done at 60°C for 10 min.

Amplicon detection

PCR products were separated directly on a 1.5% unstained agarose gel (SeaKem L). 2.5 µL of each DNA sample were mixed with 2.5 µL of SYBR Green loading buffer (to produce 150 µL SYBR loading buffer: 100 µL H2O was combined with 50 µL SYBR Green) and then loaded onto wells of the gel. The gel was run at 120 V for 60 mins and PCR products were visualized by UV illumination and photographed using INTAS GelStick IMAGER UV-Transilluminator.

Sequencing and alignment of the exons 2 and 3 of pfcrt gene

All PCR products to be sequenced were purified using Exo-SAP-IT (USB, Affymetrix, USA). Subsequently, 1 µl of the purified product was used as a template for direct sequencing with forward and reverse primers using the Big Dye terminator v. 2.0 cycle sequencer, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequence reads were 150 bp for exon 2 and 110bp for exon 3 for all the samples. The sequencing reads were then analysed, interpreted, and aligned to the exons 2 and 3 of pfcrt from P. falciparum 3D7 reference genome (PF3D7_0709000) using Geneious Sequence Alignment Editor 7.7.1.0.

Copy number variation analysis for plasmepsin 2 and 3

For all 268 samples, copy number variation of

pfpm2 (PF3D7_1408000) and

pfpm3 (PF3D7_1408100) was measured by duplex qPCR assays targeting either

pfpm2 or

pfpm3 and

pfβ-tubulin in the Light Cycler 480 II/1 (Roche) using SensiFAST™ Probe No-ROX (Meridian Biosciences), 2 µl of DNA sample, 300 nM primers and 100 nM probes in a 10 µl reaction volume. Cycling conditions were initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing and elongation at 58°C for 60 s. The single copy

β-tubulin (PF3D7_1008700) gene was used as a reference gene. The primers to the target genes, probes, protocols, were used as published [

14]. All primers were manufactured, and HPSF/Salt®-purified by Integrated DNA Technologies ®.

The relative copy number (RCN) of each target gene in each sample was calculated based on the 2−ΔΔCt method for relative quantification. ΔΔCt was calculated as (Ct

pfpm2/3(sample) − Ct

β-tubulin (sample)) − (Ct

pfpm2/3 cal − Ct

β-tubulin cal), where cal is the calibration control of genomic 3D7 DNA with one copy of both

β-tubulin and

pfpm2 and

pfpm3 [

14]. Standard curves using 3D7 strain were used to check the amplification efficiency and it ranged from 98% - 100%. DNA from the RF7

P. falciparum strain with two copies of

pfpm2/3 was used as positive control. Ct values were calculated with the second derivative maximum method using the Light Cycler 480 software (v. 5.1.1). The qPCR analysis of the samples was done in duplicates. A

pfpm2 or

pfpm3 RCN >1.5 was defined as an amplification of the gene. The mean RCN for all samples presented in the copy number graphs are derived from raw data.

Analysis

GraphPad Prism 8 was used to create all the figures associated with the analysis of the results.

3. Results

3.1. pfcrt T93S, H97Y, F145I SNPs are Absent in Clinical Isolates from Anambra State

268 patient samples were successfully amplified and sequenced. None of these samples had any of the three different SNPs, T93S and H97Y in exon 2, and F145I in exon 3, that have been associated with PPQ resistance. Other non-synonymous and synonymous mutations present in exon 2 were found in 2 of the 268 patient samples. These mutations were confirmed by a second independent PCR and sequencing run and are shown in

Table 1.

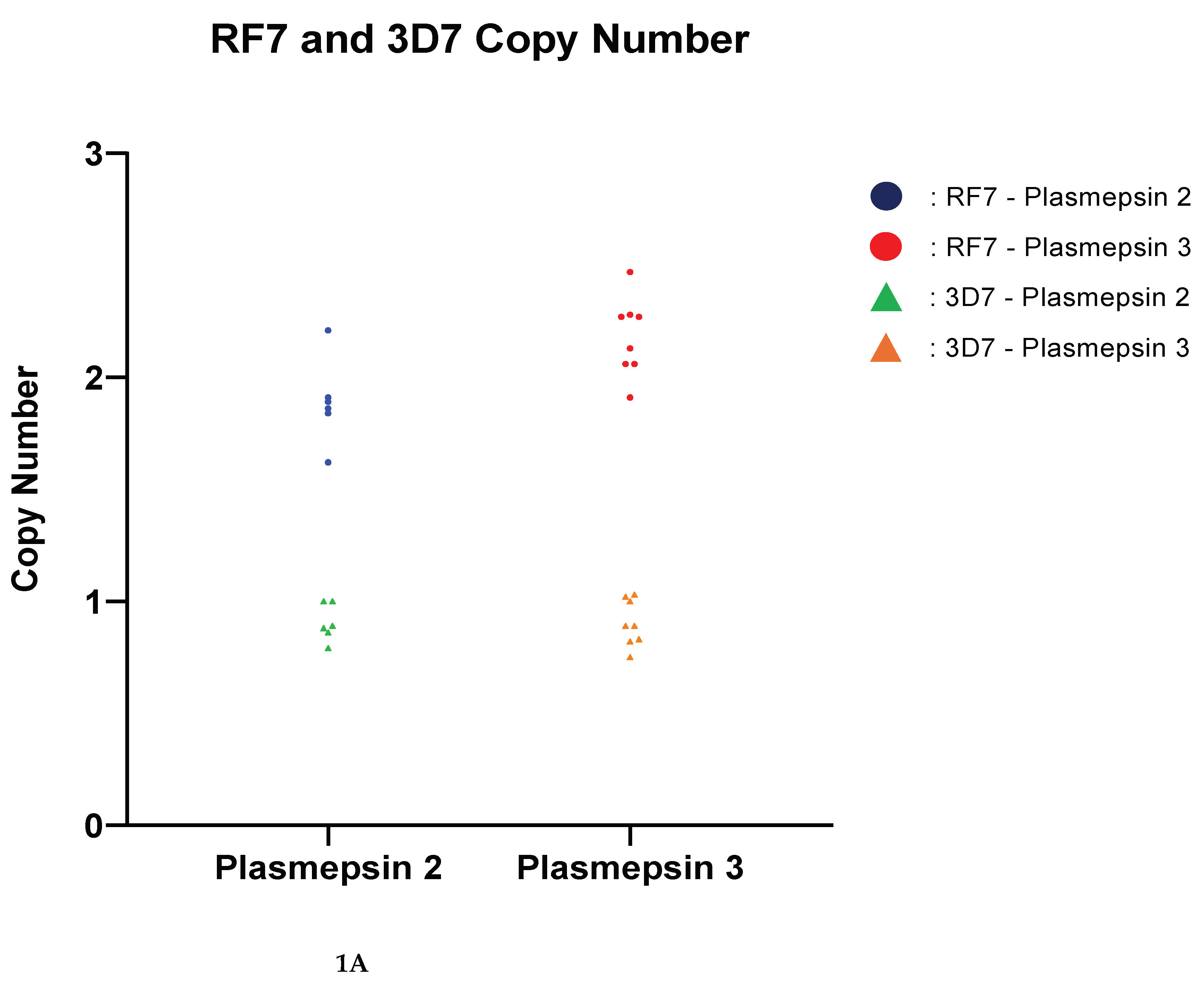

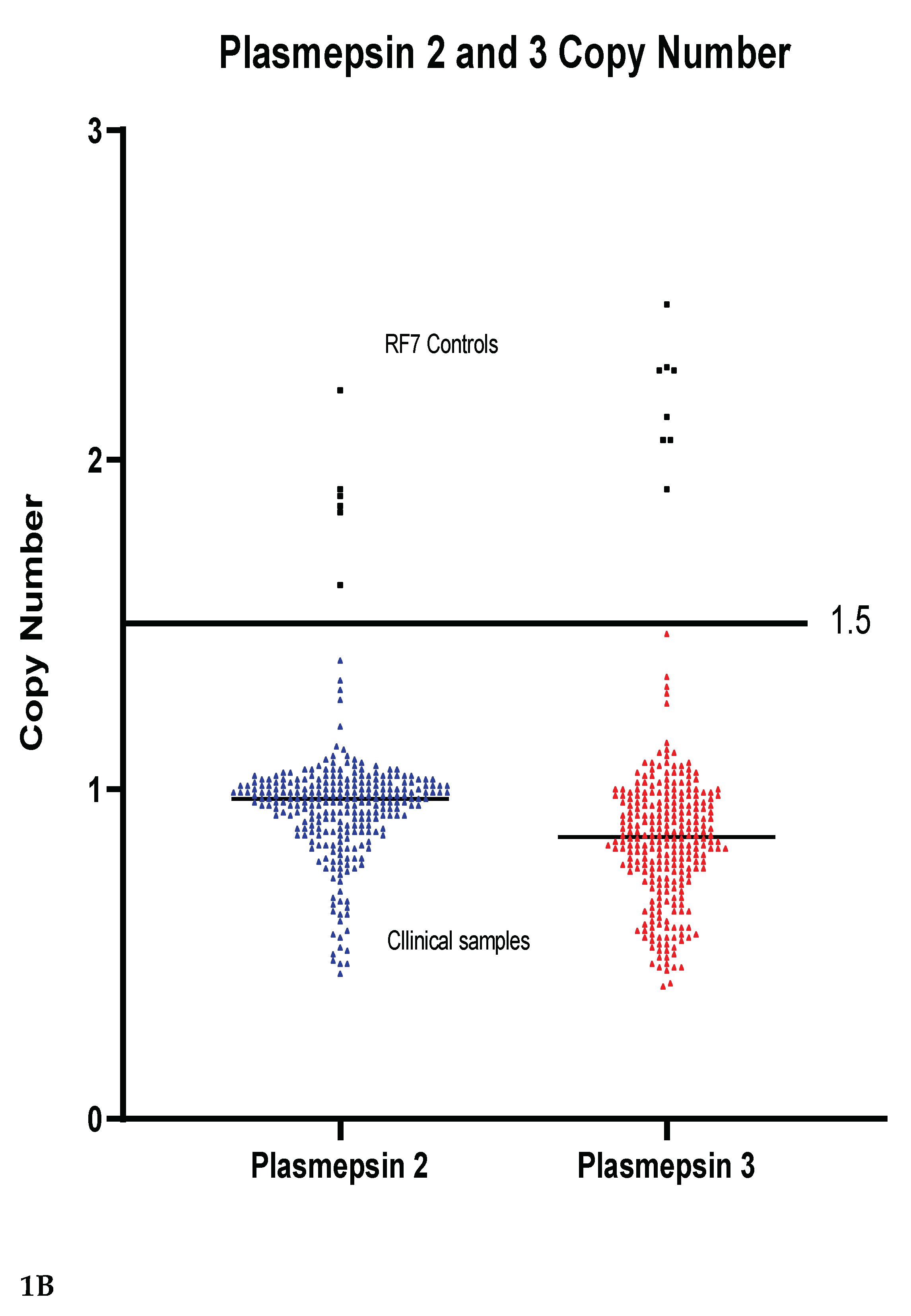

3.2. Copy Number Variation of pfpm2 and pfpm 3

Copy numbers of pfpm2 and pfpm3 were analysed as potential markers of PPQ resistance. For validation of amplification the P. falciparum RF7 strain was used and the amplification is shown in

Figure 1A. None of the clinical samples had a multicopy of either the pfpm2 or pfpm3 gene,

Figure 1B. The copy number of pfpm2 and pfpm3 in all tested clinical samples was below 1.5 copies. The median copy number of pfpm2 was 0.94 while that of pfpm3 was 0.84.

4. Discussion

The burden of malaria in Africa, and especially in Nigeria remains high. In 2023, the death toll of malaria worldwide was 597,000 with 73.7 % being children [

15]. Nigeria accounted for 26% of cases on the African continent [

15]. The progress with high impact strategies especially in Nigeria remains barely visible and the development of resistance to the currently available antimalarials remains a threat to public health. PPQ was initially utilized as an alternative to CQ, as the first-line therapy for CQ-resistant

P. falciparum in the 1970s, due to the fact it was considered at least as effective and better tolerated [

16] and has been used for a long time in China [

17]. Due to the development of PPQ-resistant strains of

P. falciparum and the appearance of the artemisinin derivatives, the use of PPQ as monotherapy diminished in the 80s [

18]. PPQ resurfaced in the 90s as a partner drug for ACT [

19]. In this current study, there was no evidence that PPQ resistant markers are present in parasites circulating in the country, as none of the investigated parasites in the 268 samples had multiple copies of

pfpm2 and/or

pfpm3

The investigated mutations in

pfcrt, T93S, H97Y, and F145I, which have been associated with treatment failures with PPQ, were also not found in the present study. Such mutations are frequently detected in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), but less prevalent or almost non-existent in Thai-Myanmar border region [

20] and northwestern Thailand [

13]. We did not sequence the exo-E415G mutation, linked to PPQ resistance in Cambodia [

21], but future research should include it in broader molecular surveillance efforts due to its relevance in parts of Southeast Asia

It has been demonstrated that amplification of

pfpm2 is not restricted to the eastern GMS [

22]. Hence, amplification of

pfmp2 has also been reported in some parts of Africa including Tanzania (10%) [

23], Mali (11%) [

24], Uganda (33.9 %) [

25], Mozambique (12.5 %) [

25], Burkina Faso (30.5 %) [

25], Gabon (11.3 %) [

25], and also in one case in two investigated samples from the Democratic Republic of Congo (50 %) [

25]. Nevertheless, DHA+PPQ remains effective in African countries and

pfpm2 amplification was not associated with DHA+PPQ treatment failure in patients from Ethiopia [

26] and Cameroon [

27]. These reports raise the question whether other mutations could be involved in PPQ resistance in African strains, differing from the main pattern observed in Southeast Asia. In this way, research on molecular markers associated with antimalarial resistance in the African parasite population could be expanded [254 28]. Although amplification of

pfpm2 has been shown not to be relevant to the development of PPQ resistance [

7], recent studies have shown that epistasis between the amplified

pfpm2/3 and certain mutations downstream of the 72-76

pfcrt 4-aminoquinoline resistance locus in

Plasmodium might enhance the generation of high-level PPQ resistance, although this synergy decreases the ability of such mutants to survive [

29]. One of the limitations of the current study is that the molecular markers were not assessed along with treatment outcomes, which would provide a more comprehensive understanding.

This study did not detect any copy number increase in the markers related to PPQ resistance in samples from southeastern Nigeria. In general, there are no indications that current ACTs have lost efficacy in Nigeria, and drug resistance is not the major driver of the country`s high malaria burden. However, the absence of PPQ resistance markers does not eliminate the risk of emerging resistance. Continuous monitoring and surveillance remain essential to detect resistance early and ensure the long-term effectiveness of malaria treatments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I. and J.H.; methodology, V.T.; validation, J.I, L.A, L.C .; formal analysis, V.T.; investigation, M.I.; resources, M.I, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing, M.I, L.A, J.I, M.R.; visualization, V.T; supervision, M.I; project administration, M.I; funding acquisition, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding and the publication costs were supported by open access funding of the University of Tübingen, Germany.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH, Nnewi Town, Nigeria) (NAUTH/CS/66/Vol.11/185/2018/118).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”

Data Availability Statement

Other supporting data like agarose gels images, sequence alignments and raw Ct values can be provided by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Federal Republic of Nigeria: National Antimalarial Treatment Policy, FMOH, National malaria and Vector Control Division, Abuja, Nigeria, 2005. National Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Malaria – 3rd Edition. (National Antimalarial Treatment Guideline (who.int).

- Summers, R.L., Dave, A., Dolstra, T.J., Bellanca, S., Marchetti, R.V., Nash, M.N., Richards, S.N., Goh, V., Schenk, R.L., Stein, W.D., Kirk, K., Sanchez, C.P., Lanzer, M., Martin, R.E., 2014. Diverse mutational pathways converge on saturable chloroquine transport via the malaria parasite’s chloroquine resistance transporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, E1759–E1767. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W., Song, X., Tan, H., Wu, K., Li, J., 2021. Molecular surveillance of anti-malarial resistance pfcrt, pfmdr1, and pfk13 polymorphisms in African Plasmodium falciparum imported parasites to Wuhan, China. Malaria Journal 20. [CrossRef]

- Eastman, R.T., Fidock, D.A., 2009. Artemisinin-based combination therapies: a vital tool in efforts to eliminate malaria. Nature Reviews Microbiology 7, 864–874. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2020). Report on antimalarial drug efficacy, resistance, and response: 10 years of surveillance (2010-2019). World Health Organization.

- Amato R., Lim P., Miotto O., Amaratunga C., Dek D., Pearson RD., Almagro-Garcia J., Neal AT., Sreng S., Suon S., Drury E., Jyothi D., Stalker J., Kwiatkowski DP., Fairhurst RM.. Genetic markers associated with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a genotype-phenotype association study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Feb;17(2):164-173. [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.S., Dhingra, S.K., Mok, S., Yeo, T., Wicht, K.J., Kümpornsin, K., Takala-Harrison, S., Witkowski, B., Fairhurst, R.M., Ariey, F., Menard, D., Fidock, D.A., 2018. Emerging Southeast Asian PfCRT mutations confer Plasmodium falciparum resistance to the first-line antimalarial piperaquine. Nature Communications 9. [CrossRef]

- Boonyalai, N., Vesely, BA., Thamnurak, C., Praditpol, C., Fagnark, W., Kirativanich, K., Saingam, P., Chaisatit, C., Lertsethtakarn, P., Gosi, P., Kuntawunginn, W., Vanachayangkul, P., Spring, MD., Fukuda, MM., Lon, C., Smith, PL., Waters, NC., Saunders, DL., Wojnarski, M. Piperaquine resistant Cambodian Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates: in vitro genotypic and phenotypic characterization. Malar J. 2020 Jul 25;19(1):269. [CrossRef]

- Olukosi, A. Y., Musa, A. Z., Ogbulafor, N., Aina, O., Mokuolu, O., Oguche, S., Wammanda, R., Okafor, H., Ekama, S. O., David, A. N., Happi, C. T., Ozor, L., Babatunde, S., Ijezie, S. N., Uhomoibhi, P. E., Awolola, S. T., Mohammed, A. B., and Salako, B. L.,2023. Design, Implementation, and Coordination of Malaria Therapeutic Efficacy Studies in Nigeria in 2018. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 108, 6, 1115-1121. [CrossRef]

- Ikegbunam, M., Maurer, M., Abone, H., Ezeagwuna, D., Sandri, TL, Esimone, C., Ojurongbe, O., Woldearegai, TG., Kreidenweiss, A., Held, J., Fendel, R. Evaluating Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests and Microscopy for Detecting Plasmodium Infection and Status of Plasmodium falciparum Histidine-Rich Protein 2/3 Gene Deletions in Southeastern Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2024 Mar 26;110(5):902-909. [CrossRef]

- Mok, S., Yeo, T., Hong, D., Shears, M.J., Ross, L.S., Ward, K.E., Dhingra, S.K., Kanai, M., Bridgford, J.L., Tripathi, A.K., Mlambo, G., Burkhard, A.Y., Ansbro, M.R., Fairhurst, K.J., Gil-Iturbe, E., Park, H., Rozenberg, F.D., Kim, J., Mancia, F., Fairhurst, R.M., Quick, M., Uhlemann, A.-C., Sinnis, P., Fidock, D.A., 2023. Mapping the genomic landscape of multidrug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and its impact on parasite fitness. Science Advances 9. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Malaria Methods & Protocols. Second Edi. London: Humana Press; 2013.

- Win, K.N., Manopwisedjaroen, K., Phumchuea, K., Suansomjit, C., Chotivanich, K., Lawpoolsri, S., Cui, L., Sattabongkot, J., Nguitragool, W., 2022. Molecular markers of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine resistance in northwestern Thailand. Malaria Journal 21. [CrossRef]

- Ansbro, MR., Jacob, CG., Amato, R., Kekre, M., Amaratunga, C., Sreng, S., Suon, S., Miotto, O., Fairhurst, RM., Wellems, TE,, Kwiatkowski, DP. Development of copy number assays for detection and surveillance of piperaquine resistance associated plasmepsin 2/3 copy number variation in Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 2020 May 13;19(1):181. [CrossRef]

- World Malaria Report. WHO. 2024.

- Briolant, S., Henry, M., Oeuvray, C., Amalvict, R., Baret, E., Didillon, E., Rogier, C., & Pradines, B. (2010). Absence of association between piperaquine in vitro responses and polymorphisms in the pfcrt, pfmdr1, pfmrp, and pfnhe genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 54(9), 3537–3544. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, Guillermo M., Giulia D’Arrigo, Cecilia P. Sánchez, Franklin G. Berger, Rebecca C. Wade, and Michael Lanzer, 2023. “Pfcrt mutations conferring piperaquine resistance in falciparum malaria shape the kinetics of quinoline drug binding and transport”, PLOS Pathogens(6), 19:e1011436. [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.M.E., Hung, TY., Sim, IK. Karunajeewa, HA., Ilett KF. Piperaquine. Drugs 65, 75–87 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Eastman, R., Fidock, D. Artemisinin-based combination therapies: a vital tool in efforts to eliminate malaria. Nat Rev Microbiol 7, 864–874 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Ye, R., Zhang, Y., Zhang, D., 2022. Evaluations of candidate markers of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the China–Myanmar, Thailand–Myanmar, and Thailand–Cambodia borders. Parasites & Vectors 15. [CrossRef]

- Amato, R., Lim, P., Miotto, O., Amaratunga, C., Dek, D., Pearson, R. D., Almagro-Garcia, J., Neal, A. T., Sreng, S., Suon, S., Drury, E., Jyothi, D., Stalker, J., Kwiatkowski, D. P., & Fairhurst, R. M. (2017). Genetic markers associated with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a genotype-phenotype association study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 17(2), 164–173. [CrossRef]

- Imwong, M., Suwannasin, K., Srisutham, S., Vongpromek, R., Promnarate, C., Saejeng, A., Phyo, A.P., Proux, S., Pongvongsa, T., Chea, N., Miotto, O., Tripura, R., Nguyen Hoang, C., Dysoley, L., Ho Dang Trung, N., Peto, T.J., Callery, J.J., Van Der Pluijm, R.W., Amaratunga, C., Mukaka, M., Von Seidlein, L., Mayxay, M., Thuy-Nhien, N.T., Newton, P.N., Day, N.P.J., Ashley, E.A., Nosten, F.H., Smithuis, F.M., Dhorda, M., White, N.J., Dondorp, A.M., 2021. Evolution of Multidrug Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: a Longitudinal Study of Genetic Resistance Markers in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 65. [CrossRef]

- Kakolwa, M.A., Mahende, M.K., Ishengoma, D.S., Mandara, C.I., Ngasala, B., Kamugisha, E., Kataraihya, J.B., Mandike, R., Mkude, S., Chacky, F., Njau, R., Premji, Z., Lemnge, M.M., Warsame, M., Menard, D., Kabanywanyi, A.M., 2018. Efficacy and safety of artemisinin-based combination therapy, and molecular markers for artemisinin and piperaquine resistance in Mainland Tanzania. Malaria Journal 17. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, J., Silva, M., Fofana, B., Sanogo, K., Mårtensson, A., Sagara, I., Björkman, A., Veiga, M.I., Ferreira, P.E., Djimde, A., Gil, J.P., 2018. Plasmodium falciparum Plasmepsin 2 Duplications, West Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases 24, 1591–1593. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, D., Macintyre, F., Adoke, Y., Ouoba, S., Barry, A., Mombo-Ngoma, G., Ndong Ngomo, J.M., Varo, R., Dossou, Y., Tshefu, A.K., Duong, T.T., Phuc, B.Q., Laurijssens, B., Klopper, R., Khim, N., Legrand, E., Ménard, D., 2019. African isolates show a high proportion of multiple copies of the Plasmodium falciparum plasmepsin-2 gene, a piperaquine resistance marker. Malaria Journal 18. [CrossRef]

- Russo, G., L’Episcopia, M., Menegon, M., Souza, S.S., Dongho, B.G.D., Vullo, V., Lucchi, N.W., Severini, C., 2018. Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine treatment failure in uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria case imported from Ethiopia. Infection 46, 867–870. [CrossRef]

- Malvy, D., Torrentino-Madamet, M., L’Ollivier, C., Receveur, M.-C., Jeddi, F., Delhaes, L., Piarroux, R., Millet, P., Pradines, B., 2018. Plasmodium falciparum Recrudescence Two Years after Treatment of an Uncomplicated Infection without Return to an Area Where Malaria Is Endemic. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 62, AAC.01892–17. [CrossRef]

- Foguim Tsombeng, F., Gendrot, M., Robert, M. G., Madamet, M., & Pradines, B. (2019). Are k13 and plasmepsin II genes, involved in Plasmodium falciparum resistance to artemisinin derivatives and piperaquine in Southeast Asia, reliable to monitor resistance surveillance in Africa?. Malaria journal, 18(1), 285. [CrossRef]

- Mok S, Fidock DA. Determinants of piperaquine-resistant malaria in South America. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024 Feb;24(2):114-116. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).