Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Qualitative Phytochemical Analysis

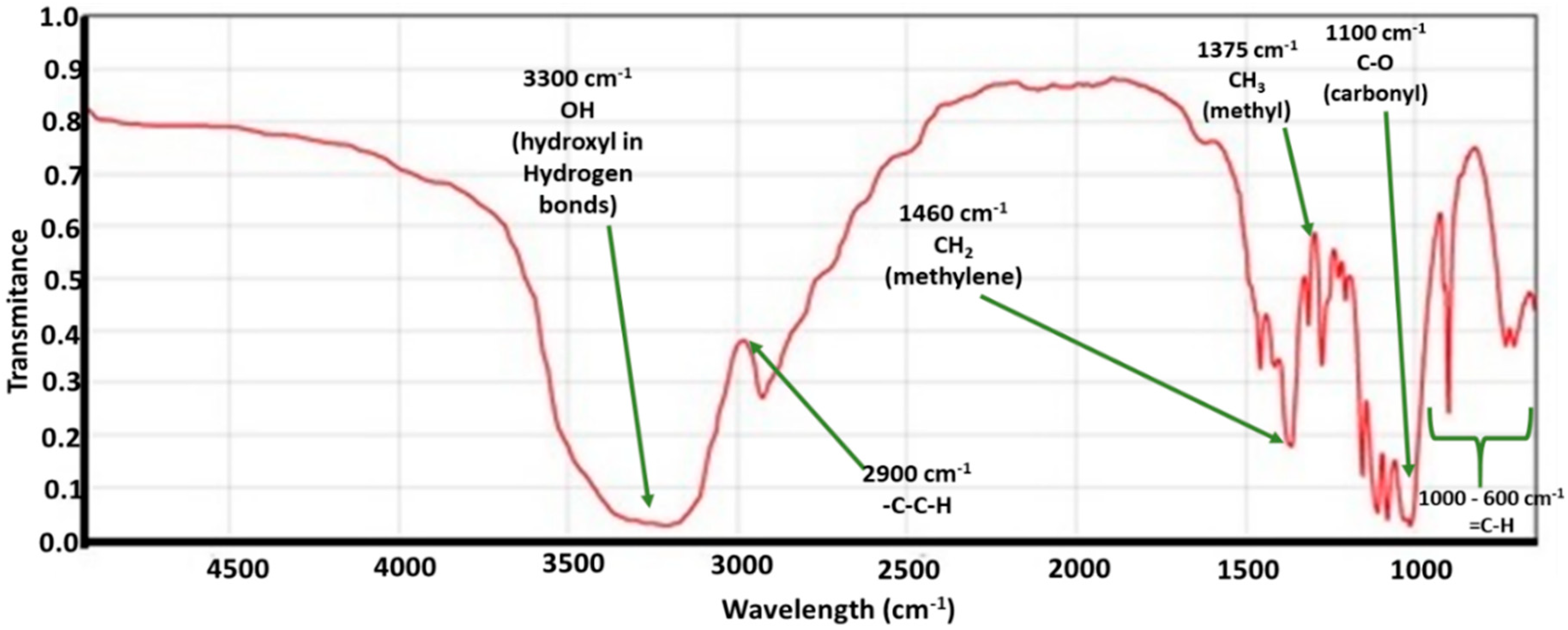

2.2. Spectroscopic Analysis

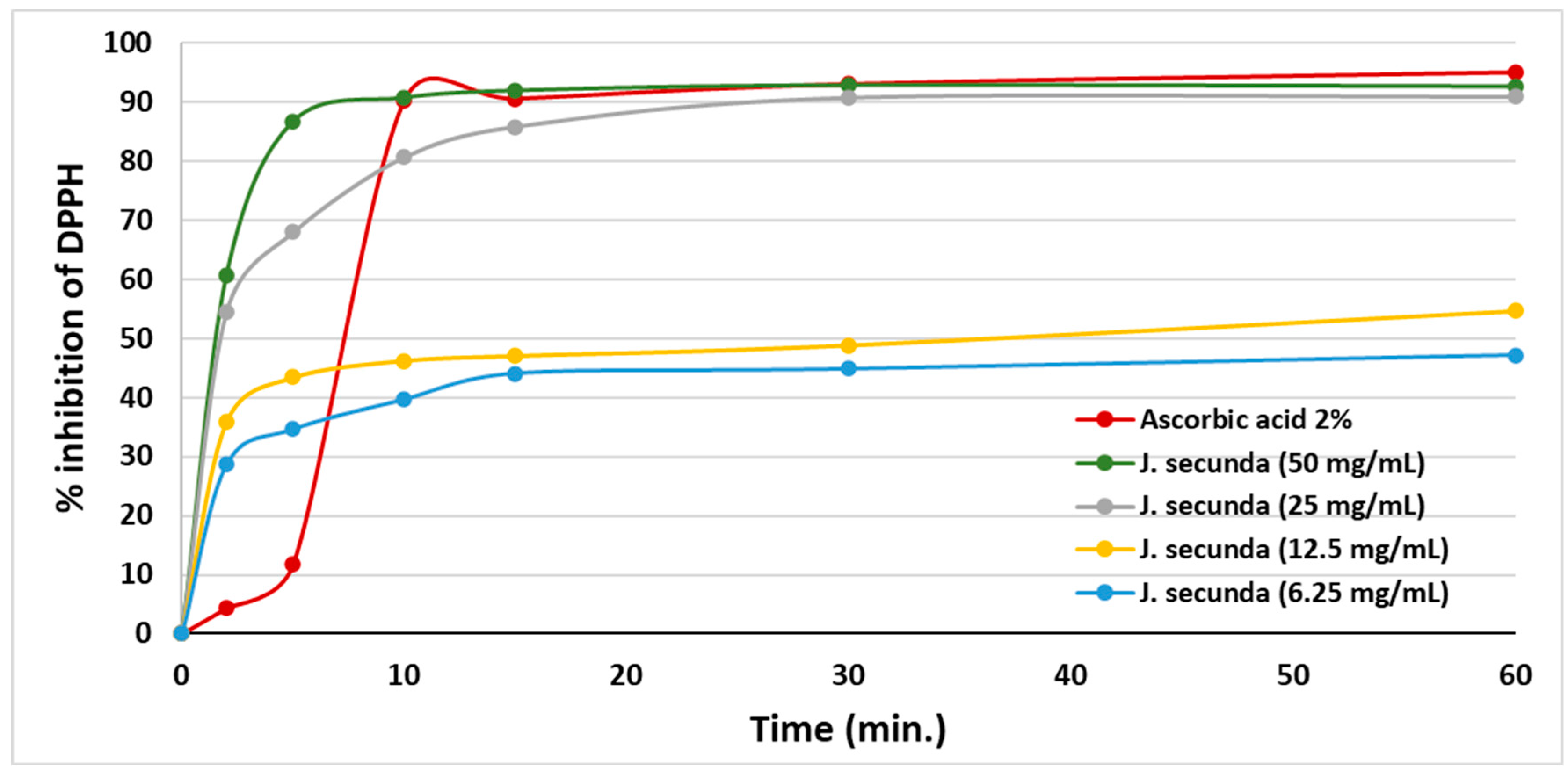

2.3. Evaluation of In-Vitro Antioxidant Activity

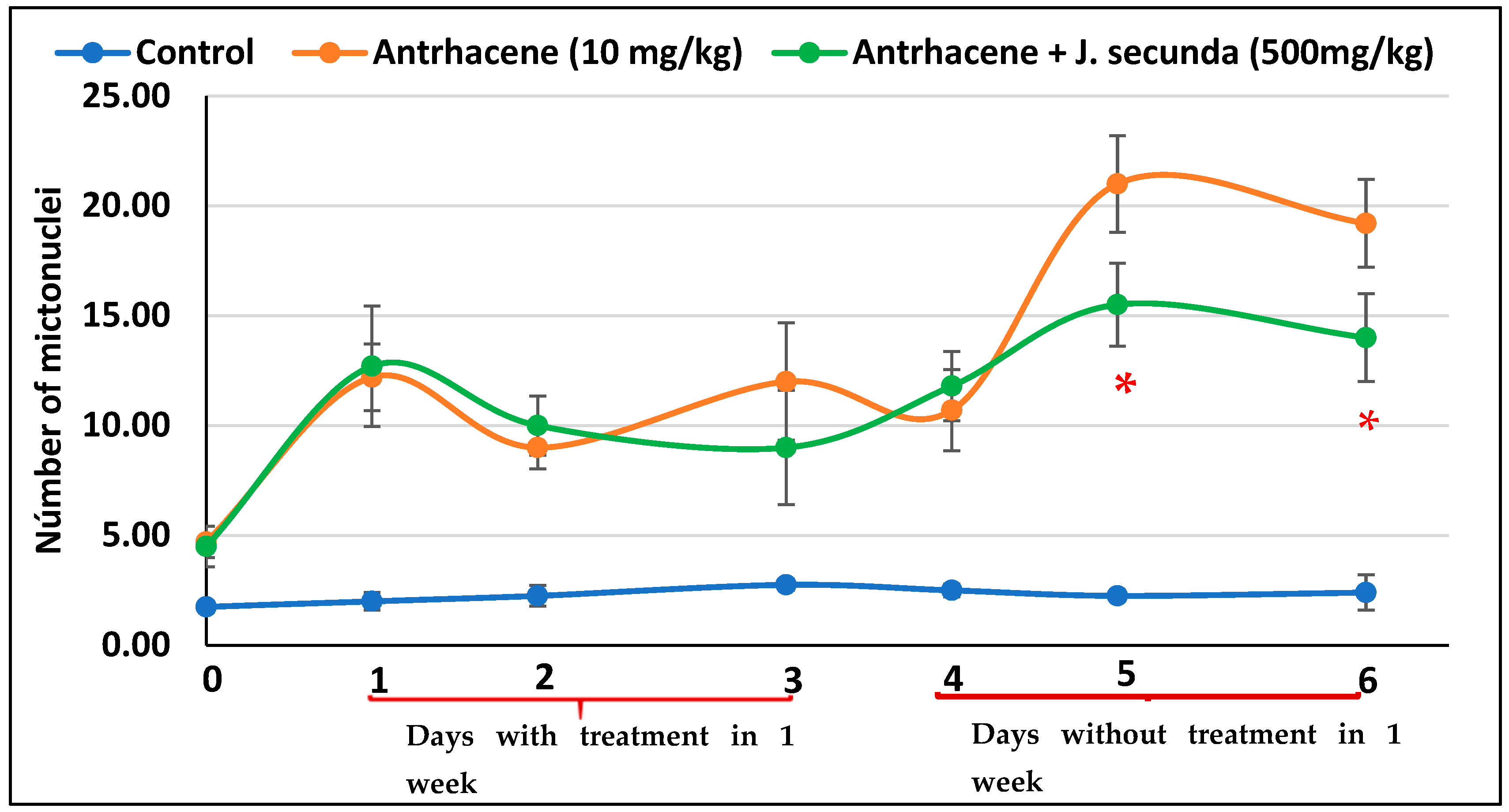

2.4. Assessment of Genoprotective Activity

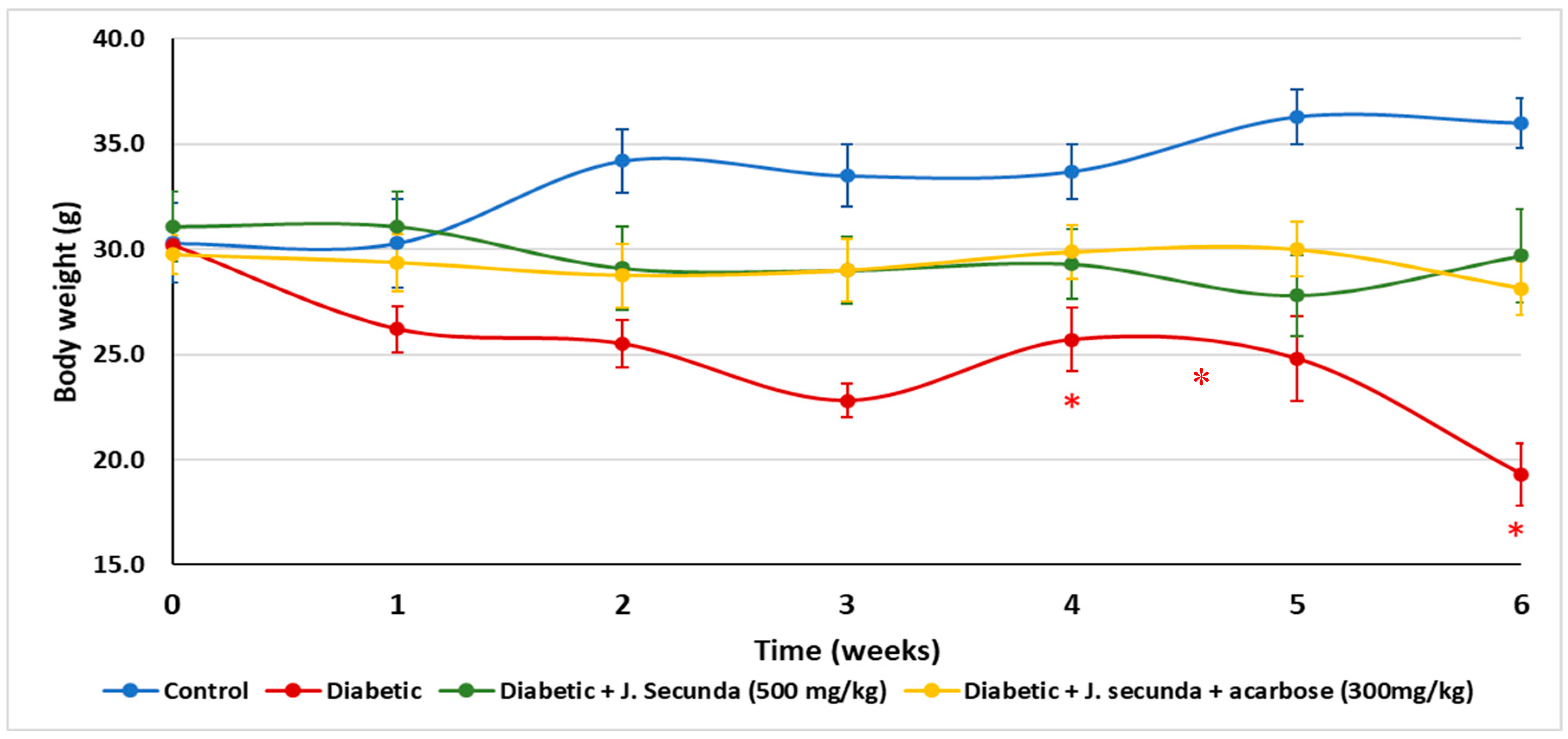

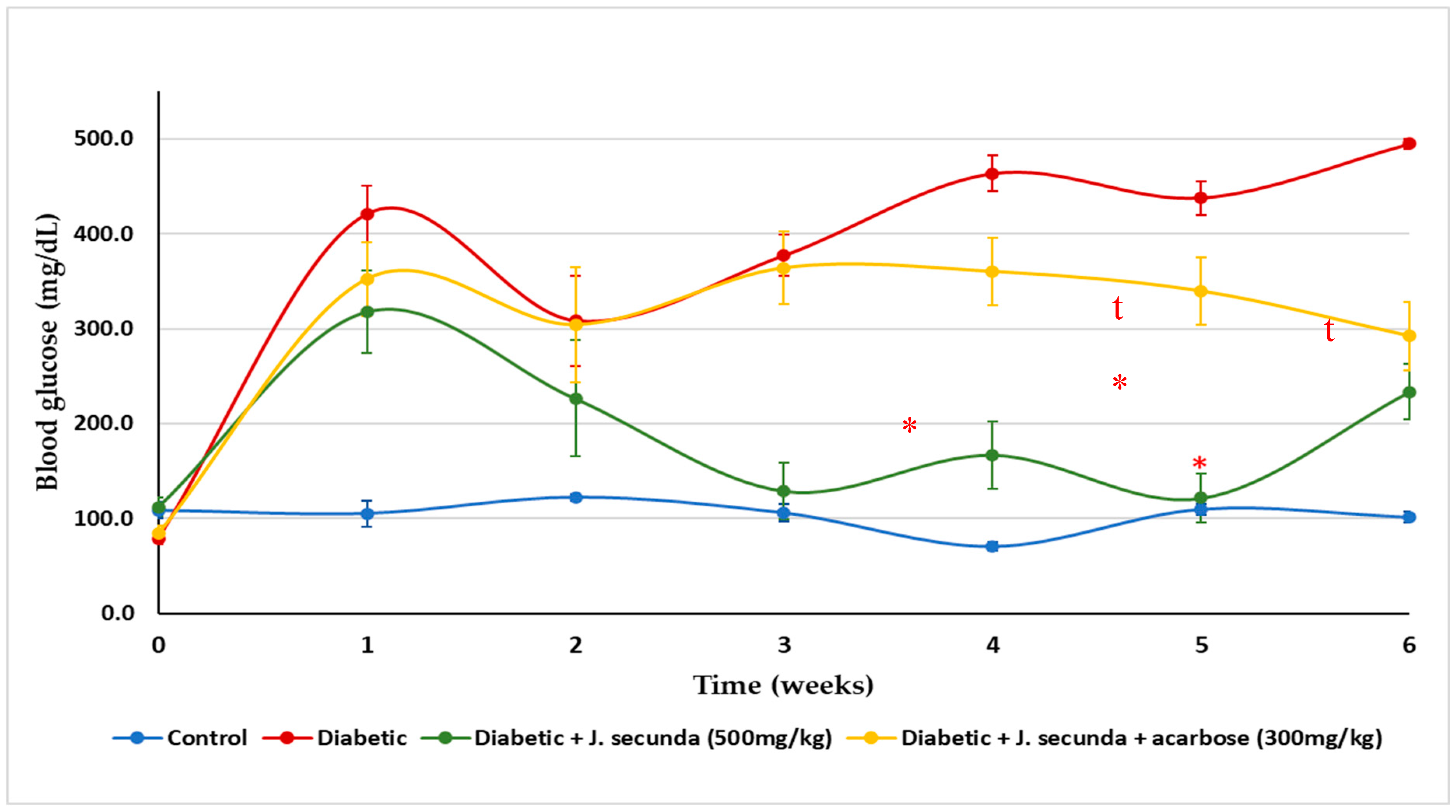

2.5. Assessment of Hypoglycemic Activity

2.6. Evaluation of Effect on Blood Triglycerides

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Acquisition of the Plant Species and Processing in the Laboratory

4.2. Chemicals Used in the Experiments

4.3. Animals in Laboratory Settings

4.4. Qualitative Phytochemical Analysis

4.5. Spectroscopic Analysis

4.6. Evaluation of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

4.7. Assessment of Genoprotective Activity

4.8. Assessment of Hypoglycemic Activity

4.9. Statistical Analyisis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez, M. Las plantas medicinales de México. 3rd edition. Botas, México, 1944, 630 pages.

- Hersch, P. De hierbas y herbolarios en el México actual. Antropol. Méx. 1999, 7, 60-65.

- Guzmán-Maldonado, S.H.; Díaz-Huacuz, R.S.; González-Chavira, M.M. Plantas medicinales: la realidad de una tradición ancestral. INIFAP, 2017, 1, 1-36.

- WHO. Traditional medicine strategy 2014 – 2023. World Health Organization, 2013, Geneva. 78 pages.

- WHO. Global strategies and plants of action that are scheduled to expire within one year. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014–2023. Executive Board, 2022, 6 pages.

- Lange, D. International trade in medicinal and aromatic planst. Actors, volumes and commodities. In: Bogers, R.J.; Craker, L.E.; Lange, D. (eds.), Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Frontis, 2006, 11: 155-170.

- Cruz-Pérez, A.L.; Barrera-Ramos, J.; Bernal-Ramírez, L.A.; Bravo-Avilez, D. Rendón-Aguilar, D. Actualized inventory of medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in Oaxaca, México. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17 (7): 1-15.

- INIFAP. México, segundo lugar mundial en registro de plantas medicinales. www.gob.mx/agricultura/prensa/mexico-segundo-lugar-mundial-en-registro-de-plantas-medicinales (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- García de Alba-García, J.E.; Ramírez-Hernández, B.C.; Robles-Arellano, G.; Zañudo.Hernández, J.; Salcedo-Rocha, A.L.; García de Alba-Verduzco, J.E. Conocimiento y uso de las plantas medicinales en la zona metropolitana de Guadalajara. Desacatos, 2012, 39: 29-44. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.C. Medicinal plants, conservation and livelihoods. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13: 1477-1517.

- He, J.; Yang, B.; Dong, M.; Wang, Y. Crossing the roof of the world: Trade in medicinal plants from Nepal to China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 224: 100-110. [CrossRef]

- Eshete, M.A.; Molla, E.L. Cultural significance of medicinal plants in healing human ailments among Guji semi-pastoralist people, Suro Barguda District, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17: 61 doi.org/10.1186/s13002-021-00487-4. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Recalde, P.; Lugo; G.; Vera, Z.; Morinigo, M.; Maidana, G.M.; Samaniego, L. Uso de plantas medicinales y fitoterápicos en pacientes con Diabetes Mellitus tipo 2. Mem. Inst. Investig. Cienc. Salud. 2018, 16(2): 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Geck, M.S.; Reyes-García, A.J.; Casu, L.; Leonti, M. Acculturation and ethnomedicine: a regional comparison of medicinal plant knowledge among the zoque of southern México. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 187: 146-159. [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Cetto, A.; Heinrich, M. Mexican plants with hypoglycaemic effect used in the treatment of diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 99, 325–348. [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Bustos, E.A.; Morales-González, A.M.; Liliana Anguiano-Robledo, L.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.O.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Lugo-Magaña, O.; Mendoza-Pérez, J.A.; Fregoso-Aguilar, T.A. Bauhinia forficata Link, Antioxidant, genoprotective, and hypoglycemic activity in a murine model. Plants. 2022, 11(22): 3052. [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Hernández, I.; Aguilar, C.N.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.; Torres-León, C.; Ilina, A.; Flores-Gallegos; A.A.; Verma, D.K.; Chávez-González, M.L. Mexican Oregano (Lippia graveolens Kunth) as Source of Bioactive Compounds: A Review. Molecules, 2021, 26: 5156. doi.org/10.3390/molecules26175156.

- Andrade-Cetto, A.; Wiedenfeld, H. Anti-hyperglycemic effect of Opuntia streptacantha Lem. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 940–943. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Díaz, M.S.; Barba-de la Rosa, A.P.; Héliès-Toussaint, C.; Guéraud, F.; Nègre-Salvayr, A. Opuntia spp.: Characterization and benefits in chronic diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 8634249. [CrossRef]

- Pingali, U.; Abid-Ali, M.; Gundagani, S.; Nutalapati, C. Evaluation of the effect of an aqueous extract of Azadirachta indica (Neem) leaves and twigs on Glycemic control, endothelial dysfunction and systemic inflammation in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 4401–4412. [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.M.; Shirahatti, P.S.; Ramith Ramu, R. Azadirachta indica A. Juss (neem) against diabetes mellitus: A critical review on its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, 74, 681–710.

- IDF Diabetes Atlas. International Diabetes Federatión. 10th Edition 2021. Available online: www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- ENSANUT. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018. Presentación de Resultados (insp.mx). Available online: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2018/doctos/informes/ensanut_2018presentaciónresultados.pdf. (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Avilés-Santa, M.L.; Monroig-Rivera, A.; Soto-Soto, A.; Lindberg, N.M. Current state of diabetes mellitus prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in Latin America: Challenges and innovative solutions to improve health outcomes across the continent. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2020, 20: 62. doi.org/10.1007/s11892-020-01341-9.

- López Sánchez, G.F.; López-Bueno, R.; Villaseñor-Mora, C.; Pardhan, S. Comparison of diabetes mellitus risk factors in México in 2003 and 2014. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 894904. [CrossRef]

- Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; Antonio-Villa, N.E.; Fermín-Martínez, C.A.; Fernández-Chirino, L.; Vargas-Vázquez, A.; Ramírez-García, D.; Basile-Alvarez, M.R.; Hoyos-Lázaro, A.E.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Wexler, D.J.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Seiglie, J.A. Diabetes-related excess mortality in Mexico: A comparative analysis of national death registries between 2017–2019 and 2020. Diab. Care. 2022, 45, 2957–2966. [CrossRef]

- Roman-Ramos, R.; Flores-Saenz, J.L.; Alarcon-Aguilar, F.J. Anti-hyperglycemic effect of some edible plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1995. 48: 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, R.R. A comparative evaluation of some blood sugar lowering agents of plant origin. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 67: 367-372. [CrossRef]

- Ovalle-Magallanes, B.; Déciga-Campos, M.; Mata, R. Antinociceptive and hypoglycaemic evaluation of Conyza filaginoides (D.C.) Hieron Asteraceae. J. Pharmacy Pharmacol. 2015, 67: 1733-1743. [CrossRef]

- Ahangarpour, A.; Heidari, H.; Oroojan, A.A.; Mirzavandi, F.; Esfehani, K.N.; Mohammadi, Z.D. Antidiabetic, hypolipidemic and hepatoprotective effects of Arctium lappa root’s hydro-alcoholic extract on nicotinamide-streptozotocin induced type 2 model of diabetes in male mice. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2017, 7(2): 169-179.

- Valdivia-Correa, B.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, C.; Uribe, M.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. Herbal medicine in Mexico: A cause of hepatotoxicity. A critical review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17: 235. [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Mora, P.; Bustamante-Pesantes, K.E. Caracterización y studio fitoquímico de Justicia secunda Vahl (sanguinaria, chingamochila, insulina). Rev. Cub. Plant. Med. 2017, 22(1): 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, I. Justicia secunda vahl, especie utilizada en ma medicina indígena Colombiana. Universidad de Sevilla. Colombia. 2019, Available online: www.idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/103953/DOMINGUEZ%20ARAGON%20ISABEL.pdf?sequence=l&isAllowed. (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Raz, L.; Agudelo, Justicia secunda Vahl. Catálogo de plantas y líquenes de Colombia. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 2023, Available online: www.gbif.org/es/dataset/5cO61470-8884-4914-ae76-70a7c81d6d08 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Ortíz-Andrade, R.; Cabañas-Wuan, A.; Arana-Argáez, V.E.; Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Zapata-Bustos, R.; Salazar-Olivo, L.A.; Domínguez, F.; Chávez, M.; Carranza-Álvarez, C.; García-Carranca, A. Antidiabetic effects of Justicia spicigera Schltdl (Acanthaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143: 455-462.

- González-Trujano, M.E.; Domínguez, F.; Pérez-Ortega, G.; Aguillón, M.; Martínez-Vargas, D.; Almazán-Alvarado, S.; Martínez, A. Justicia spicigera Schltdl. and kaempferitrin as potential anticonvulsant natural products. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 92: 240-248. [CrossRef]

- Quiñonez-Bastidas, G.N.; Navarrete, A. Mexican plants and derivates compounds as alternative for inflammatory and neuropathic pain treatment. A review. Plants. 2021, 10: 865. doi.org/10.3390/plants10050865.

- Cabada-Aguirre, P.; López-López, A.M.; Ostos-Mendoza, K.C.; Garay-Buenrostro, K.D.; Luna-Vital, D.A.; Mahady, G.B. Mexican traditional medicines for women’s reproductive health. Scientific Rep. 2023, 13: 2807. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Monographs on selected medicinal plants. World Health Organization. Geneva, 2002, 2: 1-358. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Compendium of botanicals reported to contain naturally occurring substances of possible concern for human health when used in food and food supplements. European Food Safety Authority. J. EFSA. Parma, Italy. 2012, 10(5): 2663. [CrossRef]

- Bye, R. La intervención del hombre en la diversificación de las plantas en México. In: Diversidad biológica de Mexico: Orígenes y distribución. Ramamoorthy, T.P.; Bye, R.; Lot, A.; Fa, J. Eds. 1a. ed. Instituto de Biología, UNAM. 1994. pages 689-714.

- Aguilar, A.; Camacho, J.R.; Chino, S.; Jácquez, P.; López, M.E. Herbario Medicinal del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social: Información Etnobotánica. 1ª ed. Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, México. 1994. 253 pages.

- Toledo, V.M.; Ordoñez, M.J. El panorama de la biodiversidad de México: una revision de los hábitats terrestres. In: Diversidad biologica de Mexico: Orígenes y distribución. Ramamoorthy, T.P.; Bye, R.; Lot, A.; Fa, J. Eds 1a. ed. Instituto de Biología, UNAM, México. 1998. pages 739-757.

- Gao, H.; Huang, Y.N.; Gao, B.; Li, P.; Inagaki, C.; Kawabata, J. Inhibitory Effect on α-Glucosidase by Adhatoda Vasica Nees. Food Chem. 2008. 108: 965–972.

- Wang, F.W.; Zhu, N.; Zhou, F.; Lin, D.X. Natural aporphine alkaloids with potential to impact metabolic syndrome. Molecules. 2021. 26: 6117. doi.org/10.3390/molecules26206117.

- Behl, T.; Gupta, A.; Albratty, M.; Najmi, A.; Meraya, A.M.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Anwer, K.; Bhatia, S.; Bungau, S.G. Alkaloidal phytoconstituents for diabetes management: Exploring the unrevealed potential. Molecules. 2022. 27: 5851. doi.org/10.3390/molecules27185851.

- Bhambhani, S.; Kondhare, K.R.; Giri, A.P. Diversity in chemical structures and biological properties of plant alkaloids. Molecules. 2021. 26: 3374. doi.org/10.3390/molecules26113374.

- Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Abotaleb, M.; Kubatka, P.; Kajo, K.; Büsselberg, D. Flavonoids and their anti-diabetic effects: cellular mechanisms and effects to improve blood sugar levels. Biomolecules. 2019. 9: 430; [CrossRef]

- Watrelot, A.A.; Norton, E.L. Chemistry and reactivity of tannins in Vitis spp.: A review. Molecules. 2020. 25: 2110; [CrossRef]

- Hussain, G.; Huang, J.; Rasul, A.; Anwar, H.; Imran, A.; Maqbool, J.; Razzaq, A.; Aziz, N.; Makhdoom, E.uH.; Konuk, M.; Sun, T. Putative roles of plant-derived tannins in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatry disorders: An updated review. Molecules. 2019. 24: 213. [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Brandão, E.; Guerreiro, C.; Soares, S.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Tannins in food: Insights into the molecular perception of astringency and bitter Taste. Molecules. 2020. 25: 2590. [CrossRef]

- Kopylov, A.T.; Malsagova, K.A.; Stepanov, A.A.; Kaysheva, A.L. Diversity of plant sterols metabolism: The impact on human health, sport, and accumulation of contaminating sterols. Nutrients. 2021. 13: 1623. doi.org/10.3390/nu13051623.

- Barrea, L.; Vetrani, C.; Verde, L.; Frias-Toral, E.; Ceriani, F.; Cernea, S.; Docimo, A.; Graziadio; C.; Tripathy, D.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A.; Muscogiuri, G. Comprehensive approach to medical nutrition therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: From diet to bioactive compounds. Antioxidants. 2023. 12: 904. doi.org/10.3390/antiox12040904.

- Pramanik, P.K.; Chakraborti, S.; Bagchi, A.; Chakraborti, T. Bioassay-based Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol exerts antileishmanial effects against Leishmania donovani by targeting trypanothione reductase. Sci. Rep. 2020. 10:20440. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77066-2.

- Sukalingam, K.; Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Protective effect of aqueous extract from the leaves of Justicia tranquebariesis against thioacetamide-induced oxidative stress and hepatic fibrosis in rats. Antioxidants. 2018. 7: 78. [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, P.; Wadhwani, B.D.; Rao, R.S.; Mali, D.; Vyas, P.; Kumar, T.; Nair, R. Exploring the pharmacological and chemical aspects of pyrrolo-quinazoline derivatives in Adhatoda vasica. Heliyon. 2024. 10: e25727. doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25727.

- Mastandrea, C.; Chichizola, C.; Ludueña, B.; Sánchez, S.; Álvarez, H.; Gutiérrez, A. Hidrocarburos aromáticos policíclicos. Riesgos para la salud y marcadores biológicos. Acta Bioquím. Clín. Latinoam. 2005. 39 (1): 27 – 36. [CrossRef]

- Szkudelski, T. The Mechanism of alloxan and streptozotocin action in B cells of the rat pancreas. Physiol. Res. 2001. 50: 536 – 546.

- Lenzen, S. The mechanisms of alloxan- and streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008. 51: 216 – 226. [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Bowe, J. Animal models for diabetes: Understanding the pathogenesis and finding new treatments. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016. 99: 1 – 10. doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2015.08.108.

- Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Fragoso-Antonio, S.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Solano-Solano, G.; Zúñiga-Pérez, C.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.; Izquierdo-Vega, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Salinas, J.; Esquivel-Soto, J.; Esquivel-Chirino, C.; Sumaya-Martínez, T.; Fregoso-Aguilar, T.; Mendoza-Pérez, J.; Morales-González, J.A. Investigation on the protective effects of cranberry against the DNA damage induced by Benzo[a]pyrene. Molecules. 2012. 17: 4435 – 4451. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K.; Siu-wai, C.; Siu, P.M.; Benzie, I.F. Genoprotection and genotoxicity of green tea (Camellia sinensis): Are they two sides of the same redox coin?. Redox Rep. 2013. 18: 4. [CrossRef]

- Adil., M.; Dastagir, G.; Quddoos, A.; Naseer, M.; Filimban, F.Z. HPLC analysis, genotoxic and antioxidant potential of Achillea millefolium L. and Chaerophyllum villosum Wall ex. Dc. BMC Complementary Med.Ther. 2024. 24: 91. doi.org/10.1186/s12906-024-04344-1.

- Uribe-Hernández, R.; Pérez-Zapata, A.J. Inducción de la fragmentación del DNA por Antraceno y Benzo(a)Pireno en leucocitos polimorfonucleares humanos in vitro. INCI. 2005. 30(7): 419 – 423. [CrossRef]

- Komoto, I.; Kokudo, N.; Aoki, T.; Morizane, C.; Ito, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Kimura, W.; Inoue, N.; Hasegawa, K.; Kondo, S.; Ueno, H.; Igarashi, H.; Oono, T.; Makuuchi, M.; Takamoto, T.; Hirai, I.; Takeshita, A.; Imamura, M. Phase I/II study of streptozocin monotherapy in Japanese patients with unresectable or metastatic gastroentero pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Japanese J. Clin. Oncol. 2022. 52(7): 716 – 724. doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyac048.

- Weng, Q.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, J.; Yang, L.; Xu1, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Lu, Q.B.; Ying, M.; He, Q. STAT3 dictates β-cell apoptosis by modulating PTEN in streptozocin-induced hyperglycemia. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2020. 27: 130–145. doi.org/10.1038/s41418-019-0344-3.

- Zafar, M.; Naqvi, N.U.H. Effects of STZ-induced diabetes on the relative weights of kidney, liver and pancreas in albino rats: A comparative study. Int. J. Morphol. 2010. 28(1): 135 – 142. [CrossRef]

- Ameer, M.R.; Khalid, Z.M.; Shinwari, M.I.; Ali, H. Correlation among antidiabetic potential, biochemical parameters and GC-MS analysis of the crude extracts of Justicia adhatoda L. Pak. J. Bot. 2021. 53(6): 2111 – 2125. doi.org/10.30848/PJB2021-6(30).

- Carneiro, M.R.B.; Sallum, L.O.; Martins, J.L.R.; Peixoto, J.d.C.; Napolitano, H.B.; Rosseto, L.P. Overview of the Justicia genus: Insights into its chemical diversity and biological potential. Molecules. 2023. 28: 1190. doi.org/10.3390/molecules28031190.

- Subramanian, N.; Jothimanivannan, C.; Kumar, R.S.; Kameshwaran, S. Evaluation of anti-anxiety activity of Justicia gendarussa Burm. Pharmacoligia. 2013. 4(5): 404 – 407. doi:105567/pharmacologia.2013.404.407.

- García-Ríos, R.I.; Mora-Pérez, A.; González-Torres, D.; Carpio-Reyes, R.J.; Soria-Fregozo, C. Anxiolytic-like effect of the aqueous extract of Justicia spicigera leaves on female rats: A comparison to diazepam. Phytomedicine. 2019. 55: 9 – 13. doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.07.007.

- Sowemimo, A.A.; Adio, O.; Fageyinbo, S. Anticonvulsant activity of the methanolic extract of Justicia extensa T. Anders. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011. 138: 697– 699. [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.K.; Manjula, B.L.; Balaji, M.V.; Marndi, S.; Kumar, S.; Devi, R.S. Antibacterial activity of Justicia betonica Linn. Asian Pac. J. Health Sci. 2022. 9(4): 227 - 230. [CrossRef]

- Basit, A.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, K.U.R.; Naeem, A.; Usman, M.; Ahmed, I.; Shahzad, M.N. Chemical profiling of Justicia vahlii Roth. (Acanthaceae) using UPLC-QTOF-MS and GC-MS analysis and evaluation of acute oral toxicity, antineuropathic and antioxidant activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022. 6(287): 114942. [CrossRef]

- Basit, A.; Shutian, T.; Khan, A.; Khan, S.M.; Shahzad, R.; Khan, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, M. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic potential of leaf extract of Justicia adhatoda L. (Acanthaceae) in Carrageenan and Formalin-induced models by targeting oxidative stress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022. 153: 113322. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Katoch, D.; Singh, B.; Arora, S. Seclusion of vacicine: An quinazoline alkaloid from bioactive fraction of Justicia adhatoda and its antioxidant, antimutagenic and anticancerous activities. J. Global Biosci. 2016. 5(4): 3836 – 3850. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X.; Xia, Z.; Xu, T.Q.; Chen, Y.M.; Zhou, G.X. New compounds from the aerial parts of Justicia gendarussa Burm.f. and their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021. 35(20): 3478 - 3486. [CrossRef]

- Sukalingam, K.; Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Protective effect of aqueous extract from the leaves of Justicia tranquebariesis against thioacetamide-induced oxidative stress and hepatic fibrosis in rats. Antioxidants. 2018. 7(7): 78. [CrossRef]

- Świątek, Ł.; Sieniawska, E.; Sinan, K.I.; Zengin, G.; Boguszewska, A.; Hryć, B.; Bene, K.; Polz-Dacewicz, M.; Dall’Acqua, S. Chemical characterization of different extracts of Justicia secunda Vahl and determination of their anti-oxidant, anti-enzymatic, anti-viral, and cytotoxic properties. Antioxidants. 2023. 12(2): 509. [CrossRef]

- Onochie, A.U.; Oli1, A.H.; Oli, A.N.; Ezeigwe, O.C.; Nwaka, A.C.; Okani, C.O.; Okam, P.C.; Ihekwereme, C.P.; Okoyeh, J.N. The pharmacobiochemical effects of ethanol extract of Justicia secunda. Vahl Leaves in Rattus norvegicus. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2020. 12: 423 - 437. eCollection 2020. [CrossRef]

- Akintimehin, E.S.; Karigidi, K.O.; Omogunwa, T.S.; Adetuyi, F.O. Safety assessment of oral administration of ethanol extract of Justicia carnea leaf in healthy wistar rats: hematology, antioxidative and histology studies. Clin. Phytosci. 2021. 7: 2. doi.org/10.1186/s40816-020-00234-4.

- Abo-Zaid, O.A.R.; Moawed, F.S.M.; Ismail, E.S.; Farrag, M.A. β-sitosterol attenuates high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis in rats by modulating lipid metabolism, inflammation and ER stress pathway. BMC. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2023. 24: 31. doi.org/10.1186/s40360-023-00671-0.

- Feng, S.; Dai1, Z.; Liu, A.B.; Huang, J.; Narsipur, N.; Guo, G.; Kong, B.; Reuhl, K.; Lu, W.; Luo, Z.; Yang, C.S. Intake of stigmasterol and β-sitosterol alters lipid metabolism and alleviates NAFLD in mice fed a high-fat western-style diet. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2018. 1863(10): 1274 – 1284. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Hossain, M.; Rahman, M.A.; Saha, S.; Uddin, N.; Hasan, R.; Kader, A.; Wahed, T.B.; Kundu, S.K.; Islam, M.T.; Mubarak, M.S. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activities of Justicia gendarussa leaf extract in carbofuran-induced hepatic damage in rats. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019. 32(12): 2499 – 2508. doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00345.

- Anyasor, G.N.; Moses, N. Kale, O. Hepatoprotective and hematological effects of Justicia secunda Vahl leaves on carbon tetrachloride induced toxicity in rats. Biotech. Histochem. 2020. 95(5): 349 – 359. doi.org/10.1080/10520295.2019.1700430.

- Theiler, B.A.; Istvanits, S.; Zehl, M.; Marcourt, L.; Urban, E.; Caisad, L.O.E.; Glasl, S. HPTLC bioautography guided isolation of α-Glucosidase inhibiting compounds from Justicia secunda Vahl (Acanthaceae). Phytochem. Anal. 2017. 28: 87 – 92. [CrossRef]

- Escandón-Rivera, S.M.; Mata, R.; Andrade-Cetto, A. Molecules isolated from Mexican hypoglycemic plants: A review. Molecules. 2020. 25: 4145. [CrossRef]

- Arogbodo, J.O. Evaluation of the phytochemical, proximate and elemental constituents of Justicia secunda M. Vahl leaf. Int. J. Innovative Sci. Res. Technol. 2020. 5(5): 1262 – 1268. www.researchgate.net/publication/342525145.

- Ajuru, M.G.; Kpekot, K.A.; Robinson, G.E.; Amutadi, M.C. Proximate and phytochemical analysis of the laeaves of Justicia carnea Lindi. and Justicia secunda Vahl and its taxonomic implications. J. Biomed. Biosensors. 2021. 2(1): 1 – 12.

- Alatorre-Cruz; J.M.; Carreño-López, R.; Alatorre-Cruz, Paredes-Esquivel, L.J.; Santiago-Saenz, Y.O.; Adriana Nieva-Vázquez, A. Traditional Mexican food: Phenolic content and public health relationship. Foods. 2023. 12: 1233. doi.org/10.3390/foods12061233.

- Shafodino, F.S.; Lusilao, J. M.; Mwapagha, L.M. Phytochemical characterization and antimicrobial activity of Nigella sativa seeds. PLoS ONE. 2022. 17 (8): e0272457. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272457.

- Blois, M.S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958, 181: 1199–200.

- Da Silva-Mendoça, J.; Avellaneda-Guimarães, R.D.; Zorgetto-Pinheiro, V.A.; Di Pietro-Fernandes, C.; Marcelino, G.; Bogo, D.; De Cássia-Freitas, K.; Aiko-Hiane, P.; Silva- De-Pádua-Melo, E.; Brandão-Vilela, M.L.; Aragão-Do-Nascimento, V. Natural antioxidant evaluation: A review of detection methods. Molecules. 2022, 27: 3563. doi.org/10.3390/molecules27113563.

|

Secundary Metabolite |

Reaction | Acid extract | Etanolic extract | aqueous extract |

| Alkaloids | Dragendorff Mayer |

+ + |

||

| Flavonoids | Shinoda (flavones) 10% NaOH (flavonols) |

+ + |

||

| Sterols | Liebermann Buchard | + | ||

| Tannins | Gelatin reagent 1% FeCl3 (phenolic compounds) |

+ + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).