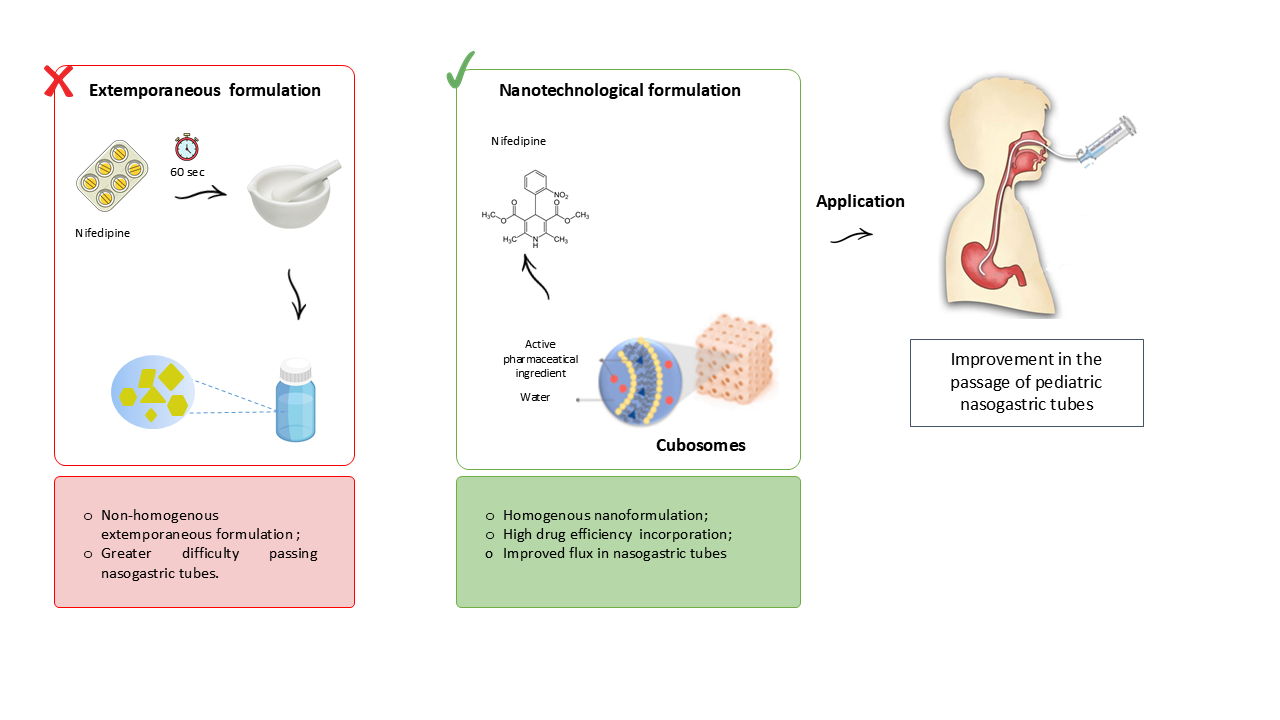

1. Introduction

Nifedipine (NIF) is a potent calcium channel antagonist that falls under the dihydropyridine group. It is extensively used in clinical practice to treat angina pectoris and hypertension [

1]. NIF is frequently administered to hospitalized pediatric patients, but it lacks availability in liquid pharmaceutical forms due to its extremely poor water-solubility [

2,

3].

Hospitalized patients often require the use of nasogastric tubes (NGT) for the administration of nutrients and medications. However, the administration of drugs through pediatric NGT can be challenging, especially for drugs that lack liquid pharmaceutical formulations. In such cases, solid dosage forms are used and can be manipulated into suspensions by crushing tablets [

4]. This tablet-crushing process can result in drug loss and the prepared suspension may not freely pass through the NGT, leading to potential tube blockage [

5].

A promising alternative to develop a liquid pharmaceutical formulation of NIF and enhance the flow through the NGT is incorporating drugs into nanosystems specifically designed for oral administration. Other hydrophobic drugs, such as spironolactone, have been successfully integrated into nanosystems to create liquid formulations, showing neither blockage nor adsorption when administered through NGT [

6].

Numerous studies have reported the incorporation of NIF into various types of nanosystems such as nanoemulsions [

7], polymeric nanoparticles [

8,

9], polymeric micelles [

10], and proliposomes [

11,

12]. All nanoparticles presented enhanced stability compared to pure NIF and promising targeted drug delivery systems, protecting the drug from the harsh acid medium in the stomach for later adsorption in the intestines.

In recent years, cubosomes have been explored as nanocarriers due to their potential as an efficient drug delivery system. Cubosomes are nanoparticles of bicontinuous cubic lyotropic liquid crystals composed of curved lipid bilayers containing two internal aqueous channels. Due to their structure, they can carry lipophilic, hydrophilic, and amphiphilic drugs [

13]. Cubosomes also have a high surface area, which makes them capable of incorporating high rates of drugs [

14]. Among the amphiphilic lipids used in the preparation of cubosomes, phytantriol has shown to be a promising option for oral formulations, as it is less susceptible to degradation by the gastrointestinal tract [

15].

Although many authors have described the advantages of incorporating NIF into nanosystems, no literature is currently available on applying nanosystems for nifedipine administration through nasogastric tubes. Furthermore, many of the techniques from previous studies relied on organic solvents to produce their nanosystems, such as chloroform [

12] and ethanol [

7], raising concerns regarding the presence of toxic residues. Therefore, this study aims to develop and characterize an organic solvent-free formulation containing phytantriol-based cubosomes for the incorporation of nifedipine, to evaluate its flow properties in pediatric nasogastric tubes, and to assess its safety through preliminary toxicity tests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Nifedipine was obtained by Fagron (Anápolis-GO, Brazil). The PHY (3, 7, 11, 15-tetramethyl-1, 2, 3-hexadecanetriol, 96.9%) and the P407 (PEO98-PPO67-PEO98, MW 12500 g mol-1) were purchased from Alianza (São Paulo, Brazil) and Via Farma (São Paulo, Brazil), respectively. Nifedipine tablets (10 mg) were obtained from Neo química, batch B21H2472. Pediatric nasogastric tubes (size 4, 6, and 8 FR 100 cm long; polyurethane) were purchased from Mark Med ® Santa Apolônia Hospitalar (Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil) All reagents were used without any purification process.

2.2. Preparation of NIF-Loaded Nanocarrier

The nanocarriers were prepared as described before [

16] with some modifications. PHY (600 mg) and NIF (2.5 mg) were melted at 40°C to obtain the oil phase. The aqueous phase (25 ml) containing P407 (300 mg) was heated to the equivalent temperature. The solution was homogenized for 25 min using a 350 W ultrasonic processor (QR350W, Ecosonics, São Paulo, Brazil) at 99% amplitude and with a 13 mm diameter probe. Finally, the final volume was corrected to 25 mL with deionized water. The nanocarrier-drug suspension contained 0.1 mg.mL

-1 of NIF and it was coded as CN. A NIF-free nanocarrier suspension was also similarly prepared, omitting the drug, and it was coded as CB.

2.3. Nanocarrier Physicochemical Characterization

2.3.1. Particle Size and Distribution

The diameter and size distribution of the particles were evaluated using the laser diffraction technique (Malvern® 2000 Mastersizer, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, United Kingdom). The sample was inserted into the distilled water container, without previous dilution, until reaching the desired obscurity. Mean particle size (Z-average) and polydispersion index (PDI) were characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zetamaster (ZEN 3600 Zetasizer® Nano Series, Malvern Instruments, UK) at an angle of 173° at 25ºC. The CB and CN formulations were previously diluted in water (1:100, w/w). A refractive index of 1.34 was used in both techniques.

2.3.2. Zeta Potential

The particle surface charge (ZP) was determined by electrophoretic mobility using a ZetaSizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). The measurements were taken after the samples were diluted in deionized water (1:100 w/w), previously filtered (0.45 µm, Miliipore). The ZP is expressed in millivolts (mV).

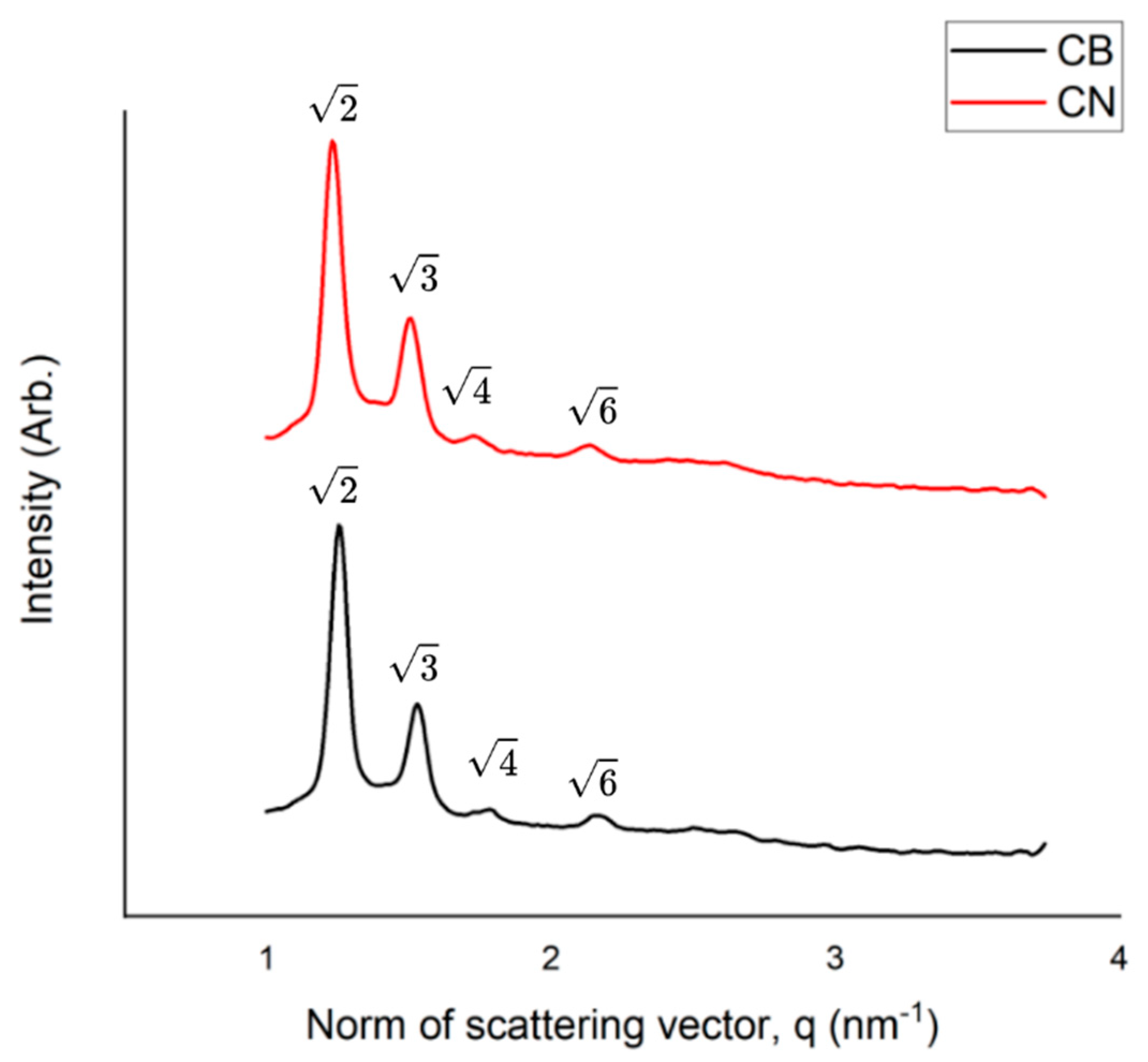

2.3.3. Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Measurements

The Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) measurements were performed to confirm the structure of the nanoparticles, using the Nano-inXider (XENOCS) at CNANO-UFRGS, which operates with Dectris® Pilatus3 detector and CuKα X-ray source (λ = 0.154 nm), being calibrated with silver behenate standard. The CB and CN formulations were placed into thin-walled Boron-Rich capillary tubes with 2.0mm O.D (Charles Supper®, Natick, MA, US). Consecutive 1 min measurements were obtained over 3 h for each sample in the medium resolution mode, at room temperature. The 1D curves were obtained from the 2D SAXS images using Origin® 2019.

2.3.4. NIF Content

The NIF content in the nanocarrier suspension was quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection (HPLC-UV; Perkin). The detection wavelength was 236 nm, the Chromatographic column was a C18 (Phenosphere®, 150 mm x 4.6 mm x 5 μm), the mobile phase consisted of methanol: water (70:30, w/w) pH 5 (phosphoric acid), the column temperature was 40°C, the flow rate was 1.0 mL.min-1, and the injection volume was 20 μL. The method was validated for specificity, linearity, precision, and accuracy.

2.3.5. Drug Incorporation Efficiency

The NIF incorporation efficiency was evaluated by the ultrafiltration-centrifugation method. An aliquot of 400 µL of each formulation was added into filter devices (Microcon 10,000 Da, Millipore, USA) and centrifuged at 6,000 RPM for 30 min. The drug content in the ultrafiltrate was directly analyzed, without prior dilution. The drug incorporation efficiency (IE) was expressed as a percentage and it was calculated as described in Eq. (1):

where C

T is the total drug content and C

I is the drug content in the ultrafiltrate.

2.3.6. Determination of pH and Density

The pH value was determined by measuring the suspension using a calibrated pH meter (Model DM-22, Digimed, Brazil), using the potentiometric method at room temperature. Density was determined using a glass pycnometer

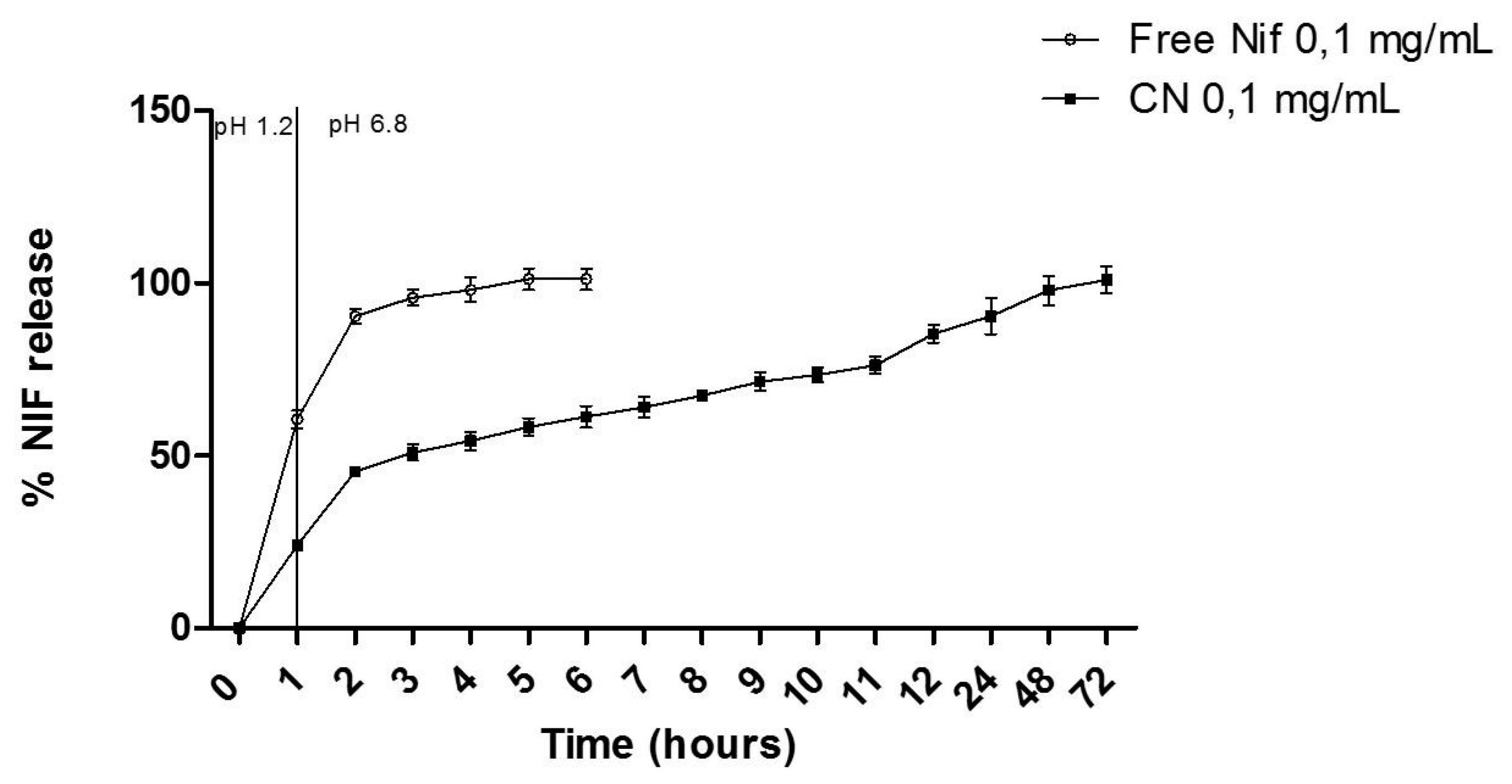

2.4. In Vitro Release Profile in Simulated Gastric Fluid

The in vitro release was performed using an adapted dialysis method (25 mm, MWCO 12 kDa, Sigma–Aldrich, USA). Initially, a dialysis bag containing 2 mL of formulation was immersed into glass flasks containing simulated gastric fluid (40 mL; pH 1.2), maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C under magnetic stirring. After 60 min, the dialysis bag was immediately placed into another glass flask with a simulated intestinal fluid pH 6.8 (potassium monobasic phosphate mixture and 0.2 M sodium hydroxide; 40 mL) maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C. At predetermined time intervals, aliquots (1 mL) of release medium were removed, filtered on a 0.45 μm membrane, and analyzed by HPLC-UV method. The removed aliquot volume was replaced by the same volume of fresh-release medium. For the NIF, the diffusion was tested following the same procedure performed for the CN. The concentration of NIF was quantified by HPLC-UV, as previously described in section 2.4. Three replicates of each experiment were carried out and the cumulative percentage of drug release was calculated.

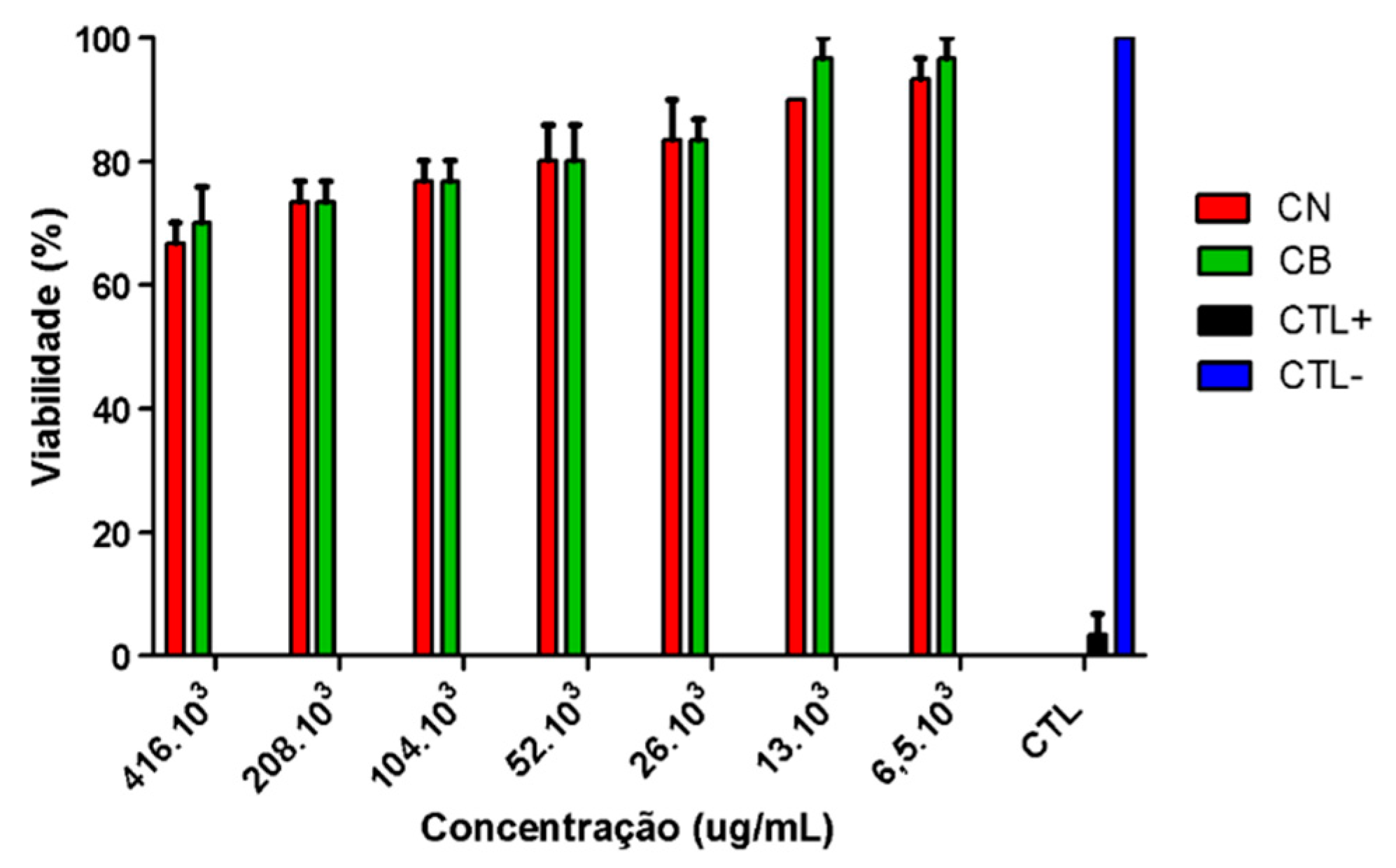

2.5. Preliminary Toxicity Assay

Brine Shrimp Lethality Assay

Toxicity was determined using the brine shrimp (

Artemia salina) lethality bioassay with CB and CN samples [

17]. Initially,

Artemia salina cysts were placed in a vial containing artificial seawater (NaCl 77.23%, MgSO

4 9.62%, CaCl

2 3.32%, KCl 2.11%, and NaHCO

3 0.59%) with a salinity of 38 g/L. After an incubation period of 24 hours, the nauplii were separated from the cysts and used for the lethality test [

18]. The concentrations for testing the CB and CN samples (w/v) were adjusted based on the concentrations of phytantriol and poloxamer 407 used for the formulation preparation. The following concentrations of the samples were obtained after dilution in artificial seawater: 416. 10

3, 208. 10

3, 104. 10

3, 52. 10

3, 26. 10

3, 13. 10

3, 6.5. 10

3 µg mL−1. Ten nauplii were added to each test tube and incubated, with the CB tubes exposed to continuous light and the CN tubes protected to prevent degradation of the active ingredient. After 24 hours, the surviving nauplii were counted using a magnifying glass and recorded. Positive control (CTL+) (potassium dichromate) and negative control (CTL-) (artificial seawater) treatments were also performed in parallel to compare the toxicity. The toxicity of the formulations was assessed based on the toxicity scales of McLaughlin and Rogers [

19]. According to the scale, concentration lethal (CL)50 values of 1000 µg/mL are considered non-toxic; values between 500 and 1000 µg/mL are considered low toxicity; values between 100 to 500 µg/mL are considered moderate toxicity, and finally, very toxic when the CL50 was below 100 µg/mL.

2.6. Preparation of Extemporaneous Nifedipine Suspensions

Extemporaneous nifedipine suspensions (FE-NIF) were prepared to simulate the procedure commonly performed in hospitals with the solid form NIF [

4]. The suspension was prepared by crushing 10 mg nifedipine tablets in a mortar and pestle for 60 seconds. The theoretical concentration of nifedipine for the suspension was 0.1 mg/mL, the same observed for the concentration of nifedipine in the cubosome suspension.

2.7. Evaluation of the Passage of Formulations Through Pediatric Enteral Nutrition Tubes

To simulate the administration of the formulations (CN and FE-NIF) through pediatric enteral nutritional tubes, previous reported methodologies were adapted [

5,

20].

Various 100 cm long pediatric enteral feeding tubes (calibers 4, 6, and 8 FR) were tested. The tubes were positioned at a 45

o angle and kept stationary during administration [

21]. All tubes were washed with 20 mL of water before the formulations were administered.

The syringes containing the formulations were attached to the ends of the tubes, and the administration was performed slowly to prevent any loss of content during the process. For each formulation (CN and FE-NIF), the experiment was conducted in batch triplicate and the samples were collected in a beaker placed at the end of the tube. The syringe containing FE-NIF was constantly stirred by small rotations during the administration to avoid accumulation of granules on the inner walls of the syringe barrel.

Due to the limited gastric capacity in infants and newborns [

22], the administration volumes for the CN and FE-NIF formulations were defined as 20 mL for the 6 and 8 FR caliber. For the 4 FR probes, the volume was 5 mL, since probes of this caliber are intended for newborns.

Between samples, the 6 and 8 FR caliber tubes were rinsed with 2, 5, or 10 mL of purified water to remove the residue that occasionally adhered to their walls and to determine the best rinse volume after drug administration. As for the 4 FR caliber probe, 1 and 2 mL were used in the rinsing step, considering its smaller administration volume.

After passing through the probes, the suspensions (CN and FE-NIF) and the rinsing water were collected and analyzed in UV-vis. In short, 800 uL of the suspensions and the rinsing water were diluted in methanol to obtain a theoretical concentration of 8 ug/mL and subsequently analyzed in UV-vis to quantify the content. The amount of NIF that successfully reached the end of the tube (the amount that would be ingested by the patient) was calculated for all formulations and the rinsing water.

The administration time for all formulations was registered and expressed in mL.seconds-1.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's test was used to compare experimental data with a significance level of 0.05 using GraphPad Prism version 5.0.

4. Discussion

The results of the physicochemical characterization demonstrate that the nifedipine-containing cubosomes formulation (CN) exhibited appropriate physicochemical properties, with nanometric particle size, low polydispersity, and negative zeta potential, suggesting good colloidal stability. Furthermore, it showed high drug incorporation efficiency without significant changes in the physical parameters compared to the control formulation (CB), implying that the presence of nifedipine did not compromise the system structure.

Similar high IE values (93%) were reported with the incorporation of NIF into monoolein cubosomes [

12]. In contrast, lower incorporation efficiencies were observed for NIF in polymeric micelles (34.1 ± 1.1%) [

10] and poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (61.81 ± 3.41%) [

25]. The high NIF incorporation efficiency into the cubosomes could be explained by the high lipophilicity of the drug, promoting the complete NIF solubilization by the oil phase.

The incorporation of the drug NIF into monolein-based cubosomes was investigated previously, aiming to improve its oral bioavailability [

12]. The particle size obtained was 91.3 nm, the PDI was 0.168, and the ZP was −12.8 mV. However, this cubosomes production process involved the use of organic solvent chloroform, raising concerns regarding the presence of toxic residues. Additionally, the processing time required for sample production was long, exceeding 24 hours.

In contrast, in the present study, the cubosomes were developed using a solvent-free production approach, with a significantly reduced processing time of only 25 minutes. This approach mitigates the risks associated with organic solvent residues presence in the samples and enhances the safety of the final product.

The three possible structures of the cubic phase are Pn3m, Im3m, Ia3d [

15]. The peaks in the SAXS pattern for CB and CN can be respectively indexed according to the Miller indices hkl= 110, 111, 200, 211, which is an indicative of the cubic phase Pn3m [

26,

27].

In previous studies, the release profile of NIF when incorporated into proliposomes exhibited a lower release rate compared to free NIF, similar to cubosomes. However, the cumulative release of NIF from proliposomes reached 88.7% in artificial intestinal fluid [

11], whereas in the present study, after 10 hours, the cumulative release of NIF from cubosomes was 73.47 ± 2.17%, indicating that incorporating NIF into cubosomes resulted in a slower release rate compared to its incorporation into proliposomes. When incorporated into monoolein cubosomes, the release rate of NIF was approximately 5% for both simulated gastric fluid and simulated intestinal fluid over a period of 24 hours [

12].

Another advantage of the present system is the use of phytantriol as the structural component of the cubosomes, instead of monoolein. While monoolein exhibits gastric instability, phytantriol has demonstrated resistance to the gastric environment, making it more suitable for oral administration of the drug. This characteristic is of great importance in ensuring the efficacy of NIF when it is orally administered [

15,

28].

In summary, the present study overcomes previous limitations by offering a more efficient and safe approach to cubosomes production, free from organic solvents, and using phytantriol as a gastric-resistant structural component. These improvements contribute to the potential clinical application of these nanosystems as promising vehicles for oral drug delivery.

The impact of rinse volume on the total recovery of proton pump inhibitors in pediatric tubes was studied before [

5]. Similarly to the presented results, the authors found that higher rinse volumes led to greater recovery percentages. In the present study, the CN sample showed a 100% recovery rate on all probes, with no losses during administration. This can be attributed to the high incorporation efficiency of nifedipine into the cubosomes. Administering medications through feeding tubes poses challenges in the hospital setting, emphasizing the importance of considering formulation characteristics. Significant losses were observed during the administration of extemporaneous formulations, and tube rinsing protocols are commonly used to minimize losses. Grinding methods, such as mortar and pestle, have shown losses during the crushing process of paracetamol.

Other report in the literature showed thar the process of crushing a sotalol tablet in a mortar and transferring it to another container was found to result in a loss of 5.5 - 13% of the tablet weight [

30]. This finding, along with our results, suggests that the losses during the preparation process of the extemporaneous formulation can vary and have a significant impact on the total percentage of NIF recovered at the end of the administration through the FE-NIF formulation.

One consequence of losses in the total percentage of FE-NIF is the administration of inconsistent doses. Additionally, drug residues in nasogastric tubes can interact with food, leading to the formation of bezoars that can cause tube blockage [

31]. To date, there have been no studies reporting the oral bioavailability of crushed NIF tablets administered via nasogastric tubes. The lack of information combined with the high percentage of NIF lost during the administration process further increases the uncertainty surrounding this practice.

In contrast, the CN nanotechnology formulation shows promise in overcoming these limitations. The total recovery rate for the CN sample was 100%, regardless of the probe size and rinse volume. The total percentage of NIF recovery for the FE-NIF formulation was influenced by the probe caliber and rinse volume.

Different from what was observed for other nanoparticles, the CN sample showed a safe profile in the

Artemia salina assay. Studies using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO₂NPs) demonstrated the broad sensitivity of

Artemia salina at different developmental stages, depending on the type of nanoparticle used [

32]. Exposure to concentrations of 10⁻¹, 10⁻² and 10⁻³ μg/mL of the different nanoparticles revealed that TiO₂NPs were non-toxic, AuNPs exerted toxic effects on cyst hatching but not on nauplii development, and AgNPs were toxic to both hatching nauplii and adults.

5. Conclusions

A new phytantriol-based cubosomes formulation containing nifedipine has been developed without the use of organic solvents, making it suitable for pediatric use. The formulation exhibited physicochemical parameters compatible with cubossomes.

The CN formulation proved to be highly applicable for use in enteral nutrition, with a total recovery rate of 100% for all tested probe sizes (4, 6, and 8 FR). Furthermore, it was observed that the rinsing volume did not affect the recovery rate of NIF for the CN sample, indicating that a minimal rinsing volume could be used during probe flushing.

These results indicate that the CN formulation has the potential to overcome common issues encountered in hospitals during the administration of crushed nifedipine tablets via enteral feeding tubes, such as tube blockage. The implementation of the CN formulation could lead to significant benefits, including increased safety in dose administration and prevention of active ingredient losses during the preparation and administration of extemporaneous formulations, particularly in pediatric cases.