Introduction

COVID-19 is a respiratory infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 that led to an unprecedented global pandemic between 2020 and 2022 and thereafter has been endemic up to the present time (December 2024). In Pakistan, approximately 1.6 million COVID-19 cases and 30,700 deaths were reported to WHO from March 2020 to April 2023 (1).

SARS-CoV-2 mutated from the original Wuhan strain to a range of variants. Emergence of variants that posed an increased risk to global public health prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to classify the variants for better global monitoring and research, and to inform and adjust COVID-19 responses (2). The classification includes variant under monitoring (VUM), variant of interest (VOI), and variants of concern (VOC) (3). VOC have genetic changes that (i) are known to affect virus characteristics such as transmissibility; (ii) have a growth advantage over other circulating variants; (iii) result in detrimental change in clinical disease severity; or, change in COVID-19 epidemiology causing substantial impact on health systems; or, significant decrease in the effectiveness of available vaccines (3). From May 2021 onwards, WHO began to assign Greek alphabets for key variants, that is VOI and VOC (4). VOCs include Alpha, Beta, Delta and Omicron with mutations linked to vaccine breakthrough infections in the case of delta and omicron variants (5).

Genomic divergence results from mutations, recombination, and genetic drifts (6). Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 genomes from all over the world has enabled unprecedented tracking of COVID-19 for public health measures. In addition, studying of SARS-CoV-2 genome substitution rate and entropy has shown genome stabilization after vaccination (7).

Vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 have been critical in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been reported that vaccinations prevented 19.8 million deaths globally (63% reduction in global deaths) in the first year (December 8, 2020 to December 8, 2021) of COVID-19 vaccination programs (8). In the WHO European region, 1.4 million lives were saved (57% reduction of deaths) by the COVID-19 vaccines since their introduction in December 2020 to March 2023 (9). In Pakistan, vaccines were rolled out in 2021 with the elderly and healthcare workers given the priority. Vaccine types distributed in Pakistan include mRNA, inactivated and viral vector vaccines. Studies of vaccine effectiveness (VE) have been conducted (10, 11). Nisar et al. reported 67.4% VE for mRNA vaccines, 58.6% for sputnik V, 49.3% for Sinovac. 47.9% for CanSino Bio, 47.4% for AstraZeneca, and 33.8 for Sinopharm. The VE was evaluated during Delta variant was in circulation (12). Khan et al. showed 33% VE for inactivated vaccines in the setting of emerging VOC(13). In general, all COVID-19 vaccines approved by WHO are protective against severe disease and death from COVID-19 infection (14).While we know that vaccines prevented death and hospitalizations(15) (16), it is not clear whether the spectrum of infecting variants differed between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

Furthermore, there is a paucity of COVID-19 data and information regarding children in Pakistan. A multi multicenter longitudinal study (March 2020–December 2021) from Pakistan reported high mortality rate (18.6%) among hospitalized pediatric population (17). While this study reported the largest spike in cases and mortality was when the Delta variant first emerged in July to September 2021, it is not known whether children were predisposed to a particular variant of SARS-CoV-2.

The present study examined sequenced genomes from Pakistan and analyzed them for VOC genomic epidemiology whilst, comparing phylogenetic variations and genomic divergence during the 2021 and 2022 period. Further, we focused on local data from Karachi, comparing strains transmitted in children as compared with adults.

Methods

Study Description

The ethical clearance was obtained from Aga Khan University’s Ethics Review Committee. This was a retrospective analysis of SARS-CoV-2 strains identified in patients from Pakistan during the period May 2021-October 2022.

We downloaded all the available Pakistan SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences (FASTA) and their corresponding metadata deposited to GISAID (a global data sharing platform of priority pathogens, gisaid.org). For quality control, we applied f “high coverage” and “complete collection date” filters before downloading the data. Further, we only included the 569 samples where the vaccination status of the COVID-19 study subject was available.

Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, SARS-CoV-2 positive laboratory records were used for analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes in younger aged individuals aged below years (n=143). Sample selection was as described by Nasir et al. (18). Briefly, SARS-CoV-2 samples were selected by identifying the first 10 specimens reported positive on each previous day. Inclusion criteria for samples was a CT (cycle threshold) value ≤ 35 as measured by the Cobas SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic assay. Exclusion criteria were specimens that had a CT value >35, or were duplicate specimens for the same individual (18).

Classification of vaccinated versus unvaccinated cases was done as per the study period whereby 2021 COVID-19 cases were classified as vaccinated whilst 2022 comprised mostly vaccinated cases. Of note, vaccination for children aged < 18 year were not available in Pakistan until later in 2021 (19). Hence, it was assumed that the cohort aged under 18 years was unvaccinated.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed on IBM SPSS v24 and GraphPad prism v8.0.1. Normality test for the genomic divergence values of the samples in the dataset was conducted using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Chi-square, unpaired samples t-test, Mann Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis statistical tests were used to analyze for significant differences. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Cohort Description

We wanted to understand the effect of COVID-19 vaccination on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Pakistan by examining the genomic epidemiology of strains circulating in 2021 and 2022. The 569 SARS-CoV-2 genomes we analyzed were those available in GISAID for samples collected between May 2021 and October 2022 and which had metadata available (

Supplementary Table S1). Overall, Omicron and Delta variants were dominant at 45.87% and 45.17% respectively (

Table 1). 54.1% of the strains had been collected in 2021 of which the dominant variant was Delta (82.8%). The remaining (45.9%) strains were from 2022 when Omicron was dominant (92%). 47.1% genomes were collected from females. The greatest number of sequences (71%) were from strains collected from children (<18 years, p<0.001).

Of the SARS-CoV-2 genomes analyzed, vaccination data was available for 569 strains. These were 29.3% (n=167) from vaccinated individuals and 70.7% (n=402) from unvaccinated individuals (

Table 2). Most unvaccinated individuals were children aged <18 years. Most (69.5%) of the vaccinated persons were in the 18-50 years old category (p<0.001).

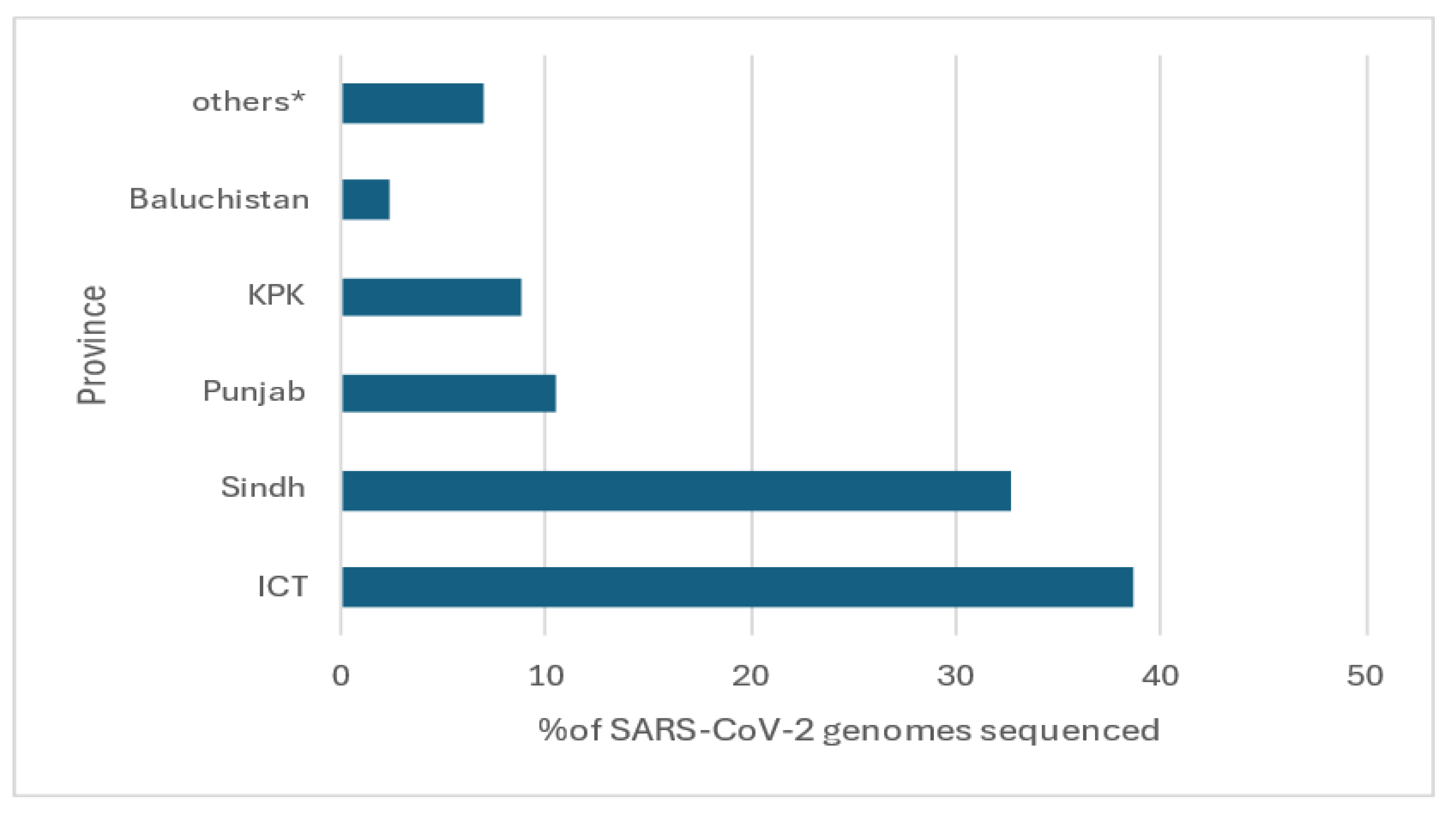

The SARS-CoV-2 genome submission were from across Pakistan. Of the 569 samples, most (38.7%) were from Islamabad (Islamabad Capital Territory, ICT), followed by Sindh (32.7%), Punjab (10.5%), Kyber Pakhtunkhwa (8.8%), Baluchistan (2.3%) and the rest from Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Jammu and Kashmir (

Figure 1).

SARS-CoV-2 Phylogenetic Diversity

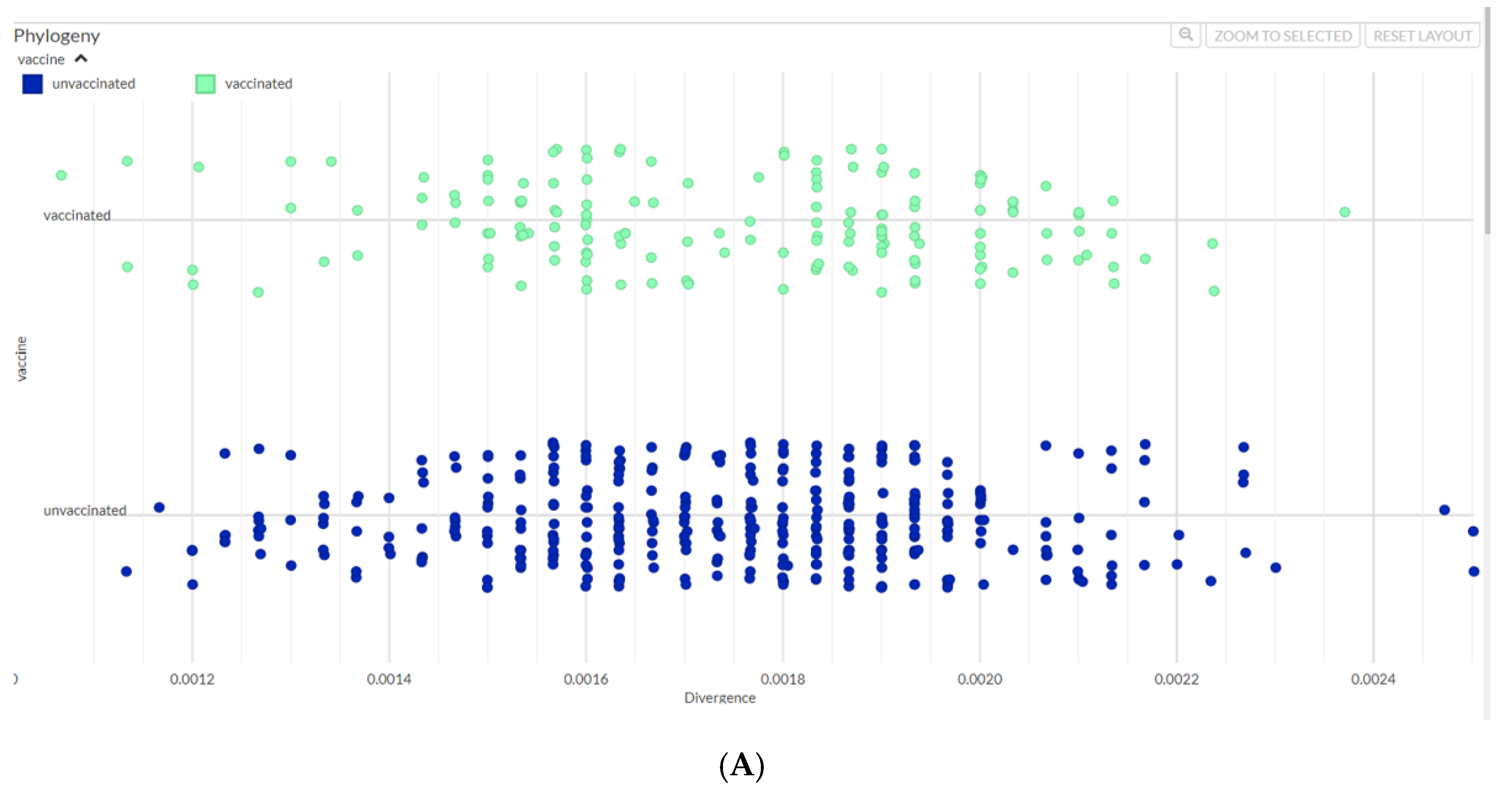

The phylogenetic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 genomes sequences during this period were studied and the divergence between the Delta variants in 2021 and Omicron variants in 2022 was evident (

Figure 2A). The most common Delta lineage was B.1.167.2 (53.7%; n=137) followed by AY.108 (24%; n=60 (Supplementary

Table 2). In 2021 there were 1.3% wildtype, 3.9% Alpha and 3.2 % Beta strains. In 2022, within the Omicron lineage BA.5.2 was prevalent (34.5%, n=87). Importantly, isolates from both unvaccinated and vaccinated groups were found amongst the SARS-CoV-2 lineages identified. We further compared the occurrence of variants between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. Strain divergence is visualized through a scatterplot and a similar pattern was observed in both vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts (

Figure 2B). Genetic differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals did not show any statistically significant difference (p=0.75, unpaired samples t-test), (

Supplementary Table S3).

Age Wise Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 Variants

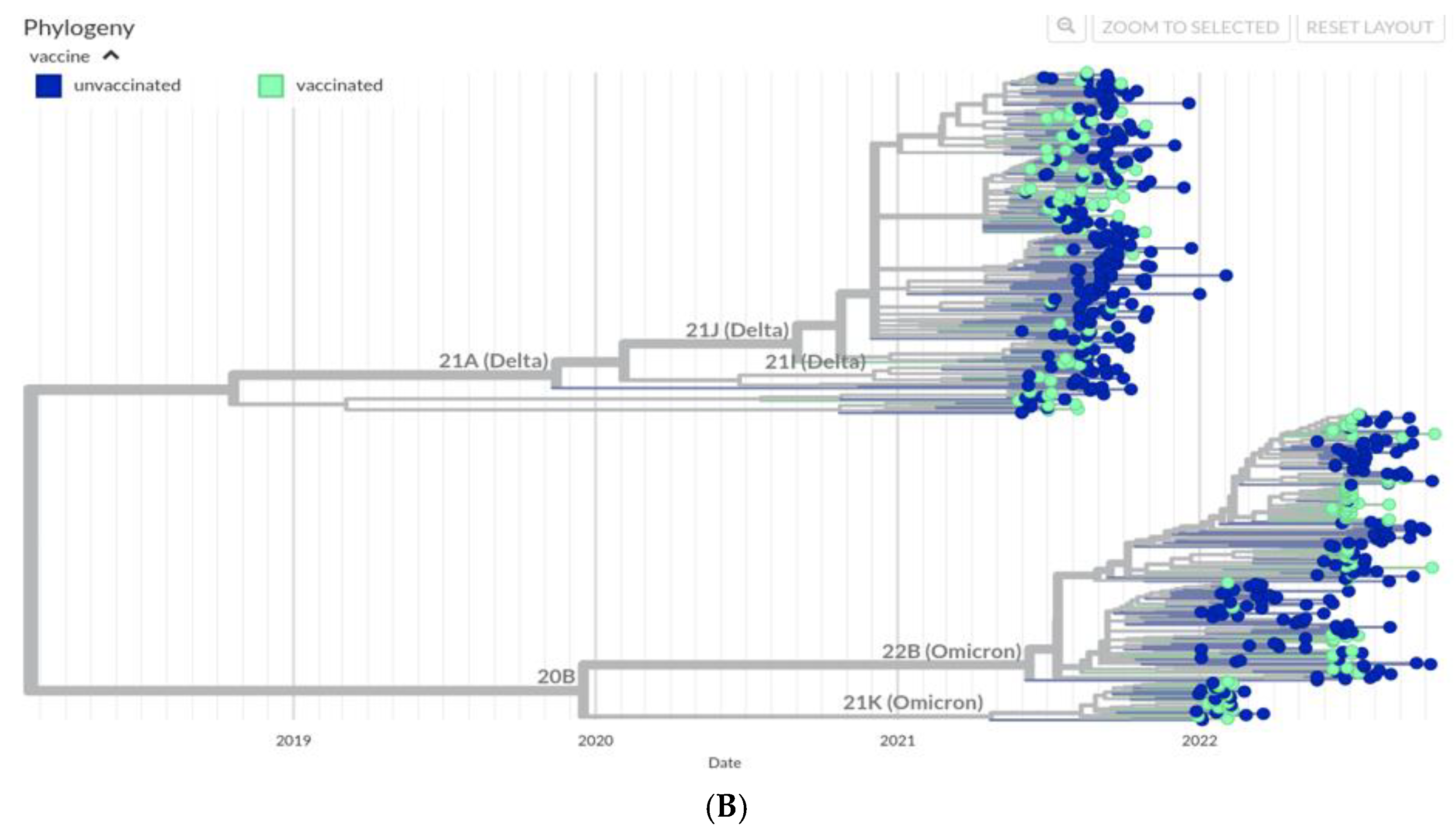

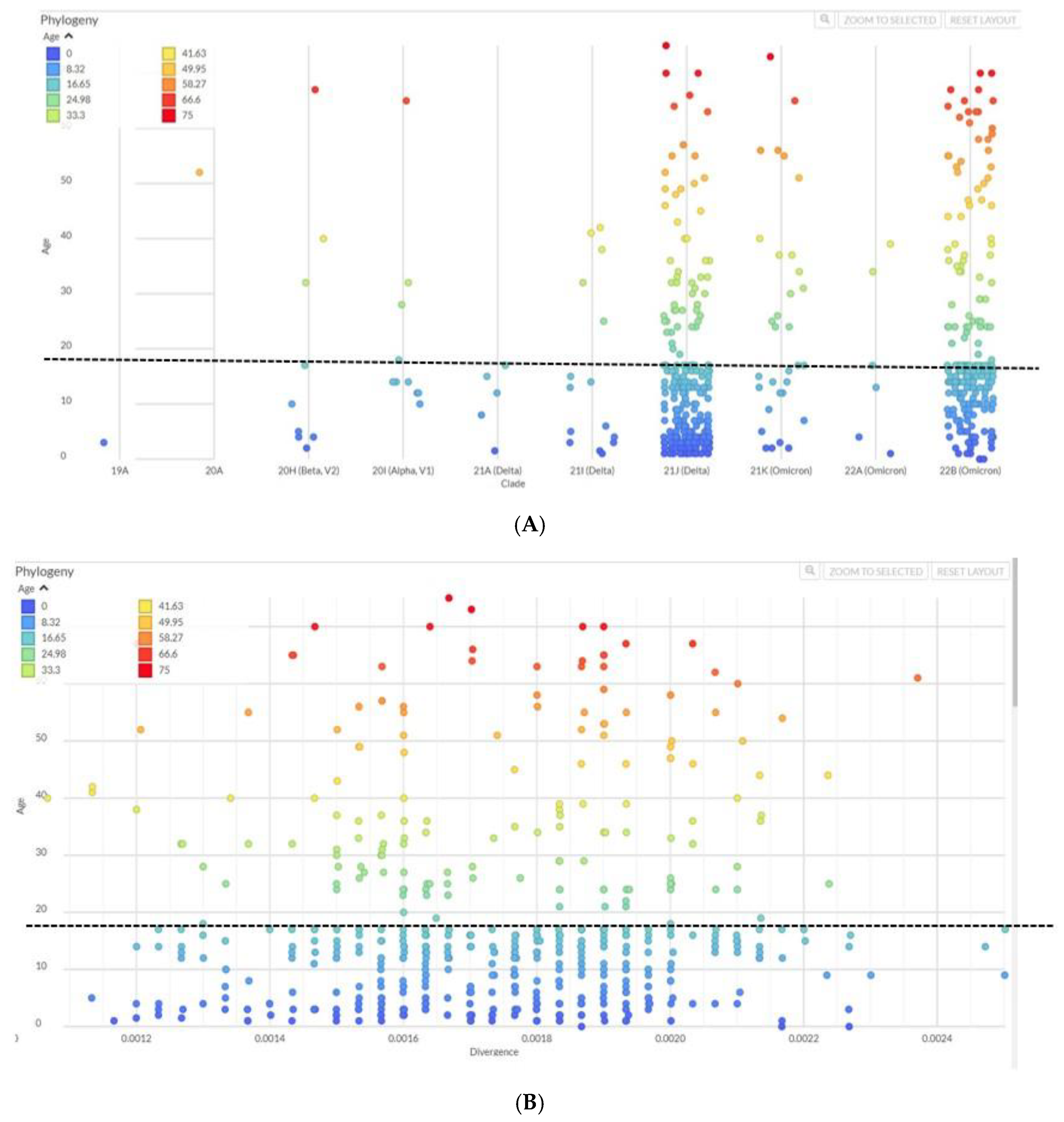

Next we compared the occurrence of variants across different age groups. Delta and Omicron were the most abundant variants across all age groups (

Figure 3A) and age-wise comparison of the strains showed a distribution of the prevalent SARS-CoV-2 variants (Beta, Alpha, Delta and Omicron) across older and younger age groups, as divided between those below 18 years and those aged 18 years and above (

Figure 3B,

Supplementary Table S3). We divided the dataset for cases less than 18 years and more than 18 years. The statistical test between the two age categories did not give a significant difference in terms of divergence. Genomic divergence analysis of variants with age also displayed the spread of those <18 years and >18 years old cases to be similar (

Figure 3B). Also, unpaired samples T-test on the genomic divergence values did not give a significant statistical difference between the two groups (p-value= 0.6038,

Supplementary Table S3).

Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Children from Karachi

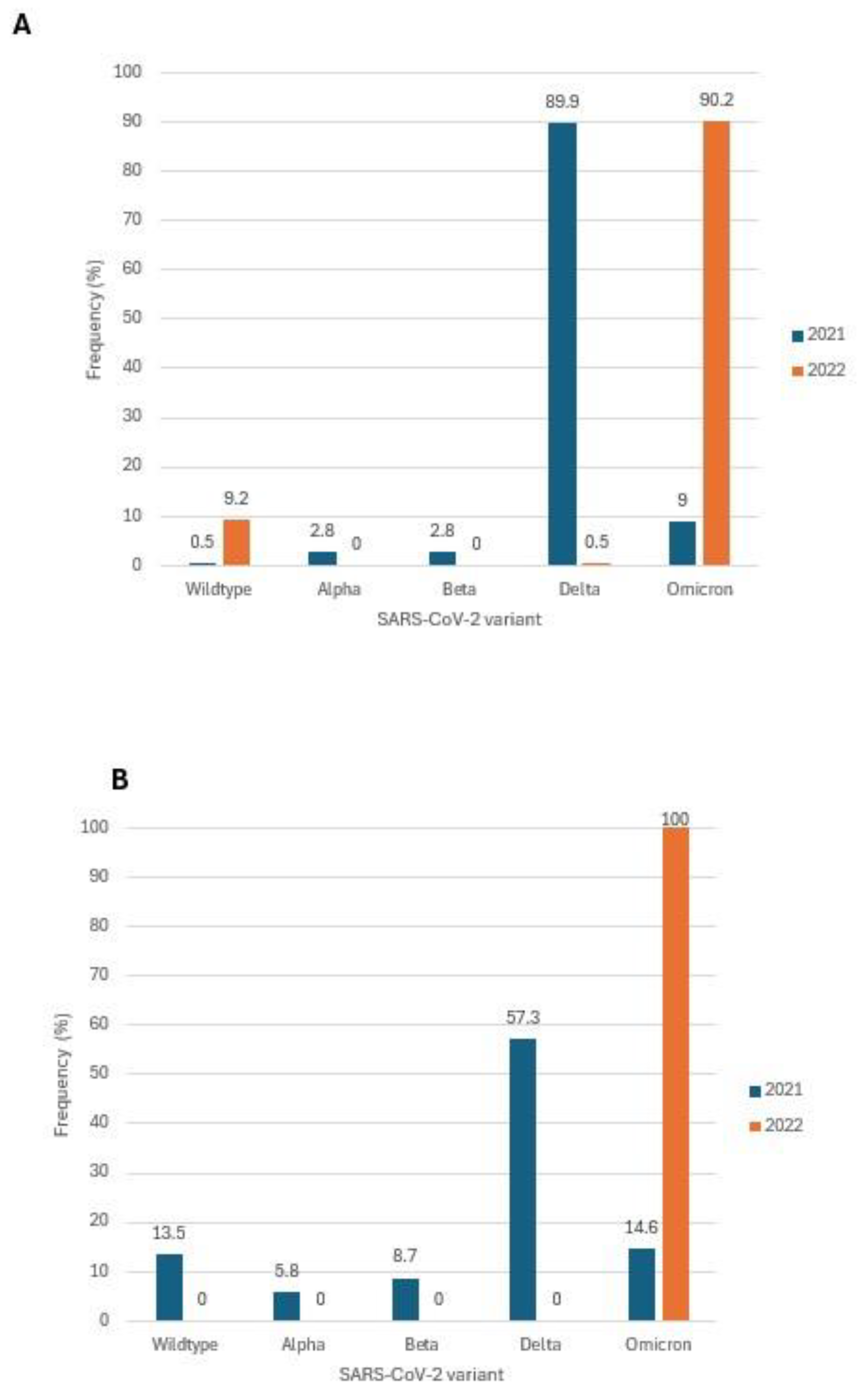

There has been limited information on COVID-19 in children aged <18 years and we now focused on this age group by comparing trends based on genomic sequences available countrywide and compared with those from our facility-based testing in Karachi. Of the SARS-CoV-2 genomes analyzed from across Pakistan, 402 were from those aged < 18 years with 218 isolated in 2021 and 184 from 2022. In 2021, 89.9% of these belonged to the Delta variant, and in 2022, Omicron was the most variant (90.2%),

Figure 4A. We also studied SARS-CoV-2 isolates received at the Aga Khan University Hospital (18) . We focused on 143 isolates collected in Karachi, of which 103 were from 2021 and 40 from 2022. Of the SARS-CoV-2 strains tested at AKUH, 70% were outpatient cases and 30% were from inpatients COVID-19 patients. Unfortunately, data on clinical disease severity of all individuals was not available. We observed the dominant variants to be Delta in 2021 (57.3%) and Omicron in 2022 (100%),

Figure 4B.

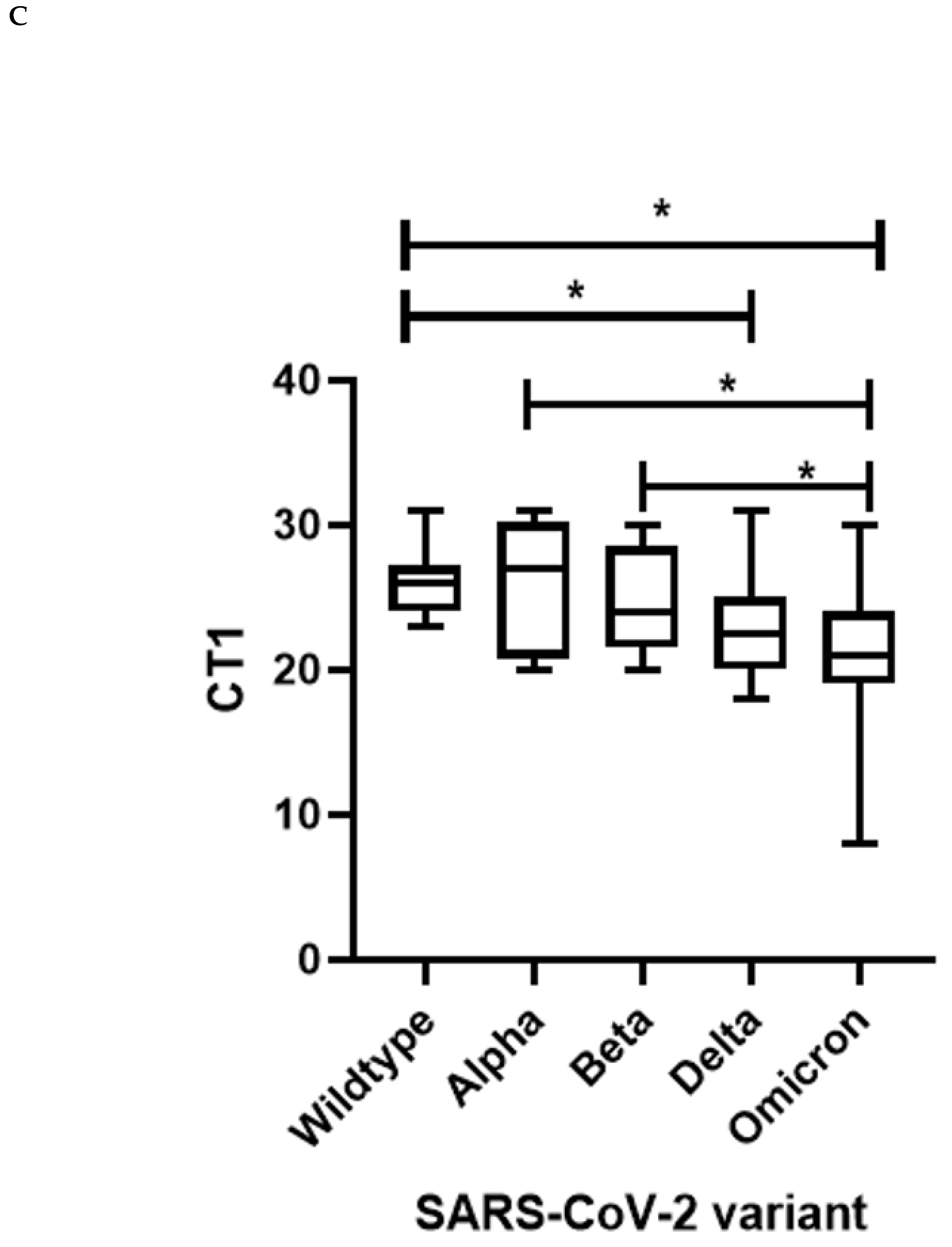

Further, we examined the SARS-CoV-2 viral loads of 143 AKUH specimens from those aged < 18 years and found SARS-CoV-2 viral loads, as determined by Ct values, to differ significantly between variants (Kruskal Wallis p value=0.0002). There was a higher Ct in wild type compared with VOC Delta (p=0.0007) and Omicron (p=0.0001),

Figure 4C. This indicated higher viral loads in cases involving VOCs as compared with wildtype strains. There was no significant difference between Wildtype and Alpha, p=0.6653; Wildtype and Beta, p=0.3239; Alpha and Beta, p=0.6238; Alpha and Delta p=0.0957; Beta and Delta, p=0.1350; Delta and Omicron, p=0.2408. Alpha variant viral loads (median CT=27) were lower than in the case of Omicron (median CT=21) (p=0.0449) infections; and the same trend was observed for Beta variants (p=0.0249). Of note, samples containing Omicron variants had the lowest median Ct value (higher viral load) in children.

Discussion

COVID-19 vaccinations were essential for reducing the morbidity and mortality during the pandemic. The public health impact of COVID-19 was variable across the globe, differentially impacting countries from high and low resource settings. Pakistan reported about 31,000 COVID-19 related deaths up to 10 March 2023, when global COVID-19 tracking was stopped. Factors associated with the impact of COVID-19 include, the age of populations, pre-existing immunity due to exposure to viral pathogens such as endemic coronaviruses (20), routine vaccinations (BCG, influenza) (21, 22), and COVID-19 vaccinations (14). Whilst, there is variation between protective efficacy afforded by different COVID-19 vaccinations all of them have been shown to reduce severe disease (14). Here, we investigated whether there were differences in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 VOC during the early pandemic period when a sub-set of the population received vaccinations. Further, we also focused on the younger population, studying children which, in the 240 million populous country of Pakistan, comprise 47% of the population according to the 2023 Census report by Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (23).

This study investigates the impact of vaccines and age in the context of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Overall results show that the spectrum of infecting variants did not differ between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. Similarly, <18 years pediatric population was not predisposed to any variant(s) when compared to adults.

The years 2021 and 2022 are important to study as this is when SARS-CoV-2 VOCs emerged causing significant global health crises (24). COVID-19 vaccines were first administered in Pakistan in 2021 based on their availability, with primary usage of inactivated virus vaccine followed by single dose vaccine formulations providing a unique situation of a mixed-vaccination status population (25, 26). By 2022, the majority of the population was vaccinated and therefore we were able to compare SARS-CoV-2 epidemiological trends comparing these time periods.

Most of the SARS-CoV-2 cases were from Islamabad (ICT) and Karachi (Sindh province) (

Figure 1 and

Supplementary Figure S1) as reported by Aziz et al. as well (27). These are the main cities in Pakistan and were hotspots for virus introductions into the country during the pandemic (28, 29). In addition, Karachi is the most populous city of Pakistan and has been the site for new variant introductions through the pandemic (29, 30).

The dataset analyzed was extracted from GISAID and most of the SARS-CoV-2 genomes collected during the study period were mostly from the pediatric population. This resulted from exclusion of samples from adult age groups where vaccination status was not available.

Vaccinations have been shown to reduce SARS-CoV-2 viral transmission, disease severity and mortality (8, 16, 31). A study by Umair et al. looked at COVID-19 variants including in individuals who had received vaccinations but the data was limited and not sufficient to study the impact of vaccination on circulating variants (32). We hypothesized that vaccination may have had an impact on the type of infecting SARS-CoV-2 variant to vaccinated persons. Visual inspection of the phylogenetic tree and scatterplot comparing both groups showed similar dispersion within the clades. Statistical analysis of genomic divergence values of the samples in the two cohorts also gave no statistically significant differences. This is the first study to investigate SARS-CoV-2 diversity based on vaccination status using genomic divergence values in Pakistan. In this case, our study fits with reports which show high rates of asymptomatic COVID-19 transmission in the Pakistani rural and urban population likely attributable to subclinical infections (33).

We found in relation to age there was similarity between COVID-19 divergence of genomes. There is paucity of information on COVID-19 in children in Pakistan. A study on hospitalized pediatric patients (≤18 years) by Abbas et al. conducted in five tertiary care hospitals across three major cities in two provinces of Pakistan, noted that Alpha was the dominant variant from January to April 2021, followed by mixed variants of Alpha, Beta and Delta from May-July 2021. Delta became dominant from July to November 2021, before it was replaced the Omicron variant in December 2021(17). Less COVID-19 diagnostic testing was conducted in children therefore there is limited information (34).

To further investigate how COVID-19 affected children nationally and locally in Karachi, we analyzed national data downloaded from GISAID and compared it with data collected from AKUH clinical laboratory. Both datasets showed similar VOC trends. In the year 2021, Delta was the main SARS-COV-2 variant affecting the pediatric population while in the year 2022, Omicron was the main SARS-COV-2 variant. Similar trends have been reported for the general population in Pakistan (7, 18) and globally (35, 36). Among the infecting variants in the pediatric population, Omicron variant had the highest viral load which may be linked to higher transmission (37). Similar findings in the general population have been reported by Nasir et al.(18).

There were limitations in this study. Firstly, vaccination details were not available for all SARS-CoV-2 genomes submitted in GISAID and therefore these data were excluded from the study. Secondly, clinical information such as reasons for testing and hospital admission, and disease severity were not available therefore we could not conclude on the impact of different VOCs in the study in the context of vaccinations.

Protection against SARS-CoV-2 is provided by humoral and cellular immunity which is driven by both natural infection and vaccinations. Earlier, we showed that population seroprevalence had reached 81% by November 2021 (38). We also showed the importance of studying immunity in the local context, as seen in the context of endemic coronaviruses which also contribute to boosting of COVID-19 vaccine immunity (39). These suggest host protection due to high seroprevalence in the population.

In conclusion, we found similar occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 strains between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in our population. Further, the strain divergence was similar between adults and children. These data shed important insights into the COVID-19 pandemic in the country, which was largely asymptomatic disease. This supports the importance of understanding factors driving protective immunity in this high infectious disease burden largely young population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Supplementary figure. Map of Pakistan and surrounding countries, and a pie chart representing samples as per location of sample collection. Supplementary table 1. Data downloaded from GISAID for samples collected May 2021 to October 2022. Supplementary table 2. Breakdown of Next clade and Pangolin lineage of the samples collected during the study period, May 2021 to October 2022. Supplementary table 3. Genomic divergence data.

Funding

Research support was provided by Higher Education Commission; Pakistan Grand Challenges Fund grant no 913 and a Health Security Partners, USA grant. Training and support for genomic epidemiology and bioinformatics was provided by a FIC JHU-APL, NIH grant.

Authors Contributions

Conceptualization, Fridah Mwendwa and Zahra Hasan; Data curation, Akbar Kanji; Formal analysis, Fridah Mwendwa, Javaria Ashraf and Ali Raza Bukhari; Funding acquisition, Rumina Hasan and Zahra Hasan; Investigation, Fridah Mwendwa; Methodology, Fridah Mwendwa and Javaria Ashraf; Supervision, Zahra Hasan; Visualization, Fridah Mwendwa; Writing – original draft, Fridah Mwendwa; Writing – review & editing, Fridah Mwendwa, Javaria Ashraf, Akbar Kanji, Ali Raza Bukhari, Rumina Hasan and Zahra Hasan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Aga Khan University (ERC Approval # : 2022-6871-22433).

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the GISAID database,

www.gisaid.org. In addition, data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary tables that lists all the sequence ID of samples used in the study.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Spiro and Zeba Rasmussen for their guidance and advice during the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Number of COVID-19 cases reported to WHO (cumulative total) Pakistan 2024 [Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?m49=586&n=c.

- WHO. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants WHO: World Health Organisation; 2023 [updated 24 February 2023; cited 2023 3/5/2023]. Previously circulating VOCs]. Available from: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants.

- WHO. Updated working definitions and primary actions for SARS-CoV-2 variants 2023 [updated 4 October 2023; cited 2023 22 November 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/updated-working-definitions-and-primary-actions-for--sars-cov-2-variants.

- WHO. WHO announces simple, easy-to-say labels for SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Interest and Concern 2021 [11/2/2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/31-05-2021-who-announces-simple-easy-to-say-labels-for-sars-cov-2-variants-of-interest-and-concern.

- Jamal Z, Haider M, Ikram A, Salman M, Rana MS, Rehman Z, et al. Breakthrough cases of Omicron and Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2 during the fifth wave in Pakistan. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 987452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvořák P, Jahodářová E, Stanojković A, Skoupý S, Casamatta DA. Population genomics meets the taxonomy of cyanobacteria. Algal Research 2023, 72, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf J, Bukhari SARS, Kanji A, Iqbal T, Yameen M, Nisar MI, et al. Substitution spectra of SARS-CoV-2 genome from Pakistan reveals insights into the evolution of variants across the pandemic. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 20955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, Hogan AB, Winskill P, Ghani AC. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet infectious diseases 2022, 22, 1293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. COVID-19 vaccinations have saved more than 1.4 million lives in the WHO European Region, a new study finds Copenhagen2024 [cited 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/16-01-2024-covid-19-vaccinations-have-saved-more-than-1.4-million-lives-in-the-who-european-region--a-new-study-finds.

- Firouzabadi N, Ghasemiyeh P, Moradishooli F, Mohammadi-Samani S. Update on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines on different variants of SARS-CoV-2. International immunopharmacology 2023, 117, 109968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Moll ME, Mata-Tijerina VL, Gutiérrez-Salazar CC, Silva-Ramírez B, Peñuelas-Urquides K, González-Escalante L, et al. The impact of comorbidity status in COVID-19 vaccines effectiveness before and after SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in northeastern Mexico: a retrospective multi-hospital study. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12, 1402527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar MI, Ansari N, Malik AA, Shahid S, Lalani KRA, Chandna MA, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in Pakistan: a test-negative case-control study. J Infect. 2023.

- Khan UI, Niaz M, Azam I, Hasan Z, Hassan I, Mahmood SF, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infections among healthcare personnel in Pakistan: a test-negative case-control study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(6):e071789.

- WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Vaccines and vaccine safety 2024 [cited 2024 10/8/2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-vaccines#:~:text=Yes%2C%20all%20WHO%20emergency%2Duse,the%20initial%20series%20or%20revaccination.

- Wang C, Liu B, Zhang S, Huang N, Zhao T, Lu QB, et al. Differences in incidence and fatality of COVID-19 by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant versus Delta variant in relation to vaccine coverage: a world-wide review. Journal of Medical Virology. 2023;95(1):e28118.

- Mwendwa F, Kanji A, Bukhari AR, Khan U, Sadiqa A, Mushtaq Z, et al. Shift in SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern from Delta to Omicron was associated with reduced hospitalizations, increased risk of breakthrough infections but lesser disease severity. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2024;17(6):1100-7.

- Abbas Q, Khalid F, Shahbaz FF, Khan J, Mohsin S, Gowa MA, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of pediatric population hospitalized with COVID-19: a multicenter longitudinal study (March 2020–December 2021) from Pakistan. The Lancet Regional Health-Southeast Asia. 2023;11.

- Nasir A, Aamir UB, Kanji A, Bukhari AR, Ansar Z, Ghanchi NK, et al. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants through pandemic waves using RT-PCR testing in low-resource settings. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(6):e0001896.

- GoP. COVID-19 vaccination PREP-gender, social risks and impact assessment. Ministry of National Health Services Regulation and Coordination, Government of Pakistan; 2021 4/4/2021.

- Shrwani K, Sharma R, Krishnan M, Jones T, Mayora-Neto M, Cantoni D, et al. Detection of Serum Cross-Reactive Antibodies and Memory Response to SARS-CoV-2 in Prepandemic and Post-COVID-19 Convalescent Samples. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(8):1305-15.

- Sarfraz A, Hasan Siddiqui S, Iqbal J, Ali SA, Hasan Z, Sarfraz Z, et al. COVID-19 age-dependent immunology and clinical outcomes: implications for vaccines. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2021:1-7.

- Cocco P, Meloni F, Coratza A, Schirru D, Campagna M, De Matteis S. Vaccination against seasonal influenza and socio-economic and environmental factors as determinants of the geographic variation of COVID-19 incidence and mortality in the Italian elderly. Prev Med. 2021;143:106351.

- GOP. 7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics; 2024 [cited 2023. Available from: https://www.pbs.gov.pk/digital-census/detailed-results.

- Gao L, Zheng C, Shi Q, Xiao K, Wang L, Liu Z, et al. Evolving trend change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in public health. 2022;10:957265.

- WHO. Pakistan Receives First Consignment of COVID-19 Vaccines via.

- COVAX Facility 2021 [Available from: https://www.emro.who.int/media/news/pakistan-receives-first-consignment-of-covid-19-vaccines-via-covax-facility.html.

- Ahmad T, Abdullah M, Mueed A, Sultan F, Khan A, Khan AA. COVID-19 in Pakistan: A national analysis of five pandemic waves. Plos one. 2023;18(12):e0281326.

- Aziz MW, Mukhtar N, Anjum AA, Mushtaq MH, Ashraf MA, Nasir A, et al. Genomic diversity and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 lineages in Pakistan. Viruses. 2023;15(7):1450.

- Ali I, Shah SA, Siddiqui N. Pakistan confirms first two cases of coronavirus, govt says “no need to panic”. DAWN COM, February. 2020;26.

- Bukhari AR, Ashraf J, Kanji A, Rahman YA, Trovão NS, Thielen PM, et al. Sequential viral introductions and spread of BA. 1 across Pakistan provinces during the Omicron wave. BMC genomics. 2023;24(1):432.

- Nasir A, Bukhari AR, Trovão NS, Thielen PM, Kanji A, Mahmood SF, et al. Evolutionary history and introduction of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha VOC/B.1.1.7 in Pakistan through international travelers. Virus Evolution. 2022;8(1).

- Mushtaq MZ, Nasir N, Mahmood SF, Khan S, Kanji A, Nasir A, et al. Exploring the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 variants, illness severity at presentation, in-hospital mortality and COVID-19 vaccination in a low middle-income country: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Health Science Reports 2023, 6, e1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair M, Ikram A, Rehman Z, Haider SA, Ammar M, Badar N, et al. Genomic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in Pakistan during the fourth wave of pandemic. Journal of Medical Virology. 2022;94(10):4869-77.

- Iqbal J, Hasan Z, Habib MA, Malik AA, Muhammad S, Begum K, et al. Evidence of rapid rise in population immunity from SARS-CoV-2 subclinical infections through pre-vaccination serial serosurveys in Pakistan. Journal of Global Health. 2025;15:04078.

- Ghanchi NK, Masood KI, Qazi MF, Shahid S, Nasir A, Mahmood SF, et al. Disparities in age and gender-specific SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic testing trends: a retrospective study from Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2629.

- Campbell F, Archer B, Laurenson-Schafer H, Jinnai Y, Konings F, Batra N, et al. Increased transmissibility and global spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as at June 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100509. [Google Scholar]

- Kung Y-A, Chuang C-H, Chen Y-C, Yang H-P, Li H-C, Chen C-L, et al. Worldwide SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant infection: Emerging sub-variants and future vaccination perspectives. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2024.

- Puhach O, Meyer B, Eckerle I. SARS-CoV-2 viral load and shedding kinetics. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2023;21(3):147-61.

- Soofi SB, Hasan Z, Iqbal J, Habib MA, Malik AA, Muhammad S, et al. Evidence of rapid rise in population immunity from SARS-CoV-2 subclinical infections through pre-vaccination serial serosurveys in Pakistan J Global Health. 2025;In Press.

- Hasan Z, Masood KI, Veldhoen M, Qaiser S, Alenquer M, Akhtar M, et al. Pre-existing IgG antibodies to Spike of hCoVs OC43 and NL63 likely enhanced protection against to SARS-CoV-2 and after COVID-19 vaccinations Heliyon. 2025;11:e42171.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).