4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Surface Color in the No Artificial Lighting Scene (S0) on Emotional Well-Being

The no artificial lighting scene (S0) had a significant effect on enhancing relaxation, indicating that even under dim evening light conditions, the natural color tones of the snowy landscape still contributed positively to Emotional Well-being. Numerous studies suggest that natural landscapes possess a "restorative" quality, promoting psychological relaxation and attentional recovery [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In winter environments, particularly in snow-covered landscapes, the diffuse reflection of light from snow-covered vegetation and ground surfaces creates a sense of tranquility and purity. This is often associated with reduced noise interference and minimal visual distractions, which can have a positive impact on specific dimensions of positive emotions, such as relaxation and comfort. Even in low-illuminance evening or nighttime conditions, the "brightness" and "purity" of snow-covered landscapes may still visually construct a unique atmospheric environment, allowing participants to experience a "beauty of silence" and achieve partial physiological and psychological relief. The minimalist visual environment helps reduce excess visual information, creating an effect similar to "subtractive design", which facilitates relaxation and contemplation. The snow-covered surface in S0, influenced by reflected light from the deep blue evening sky, appeared deep blue in color. The enhanced relaxation effect observed in S0 aligns with prior research findings that blue tones tend to increase relaxation in Emotional Well-being studies [

18,

20]. This suggests that blue may be one of the key factors contributing to the positive impact of snowy landscapes on Emotional Well-being.

However, this "deep blue" or "dim" natural snowy landscape scene also has its limitations. Due to the low solar altitude during the evening period, the sky appears more blue or grayish-blue, casting large shadow areas on the snow-covered surface. This results in an overall visual environment that may be perceived as "slightly dim and cold". On the one hand, for individuals with rich winter life experience, such a snowy landscape might evoke a "familiar and slightly relaxing" state. On the other hand, for those unfamiliar with cold climates or lacking outdoor winter experience, the dim environment could trigger a certain degree of safety concerns or feelings of loneliness. As a result, in this study, blue emotions such as worry and nervous in S0 were not entirely absent, but instead remained at a relatively mild level compared to other lighting conditions. This indicates that the "deep blue" atmosphere of the natural environment alone cannot completely eliminate the psychological unease that humans may experience during winter nights.

At the design and planning level, this finding suggests that urban winter outdoor spaces do not necessarily require large-scale artificial lighting coverage for snowy landscapes. Instead, it may be beneficial to retain some of the original shadows or dim environments, allowing people to experience the pure natural beauty of snow and thereby achieve a certain level of relaxation and enjoyment. However, to balance safety and comfort, moderate lighting supplementation should be considered for high-footfall areas or key transportation nodes, ensuring that pedestrians can appreciate the beauty of snow without artificial lighting while avoiding the fear or anxiety that deep darkness might induce at night. In other words, combining a naturally dim environment with a few warm-colored point light sources or using localized artistic light projections could enhance positive emotions while effectively mitigating blue emotions.

4.2. The Impact of Light Color on Positive Emotions in Emotional Well-being

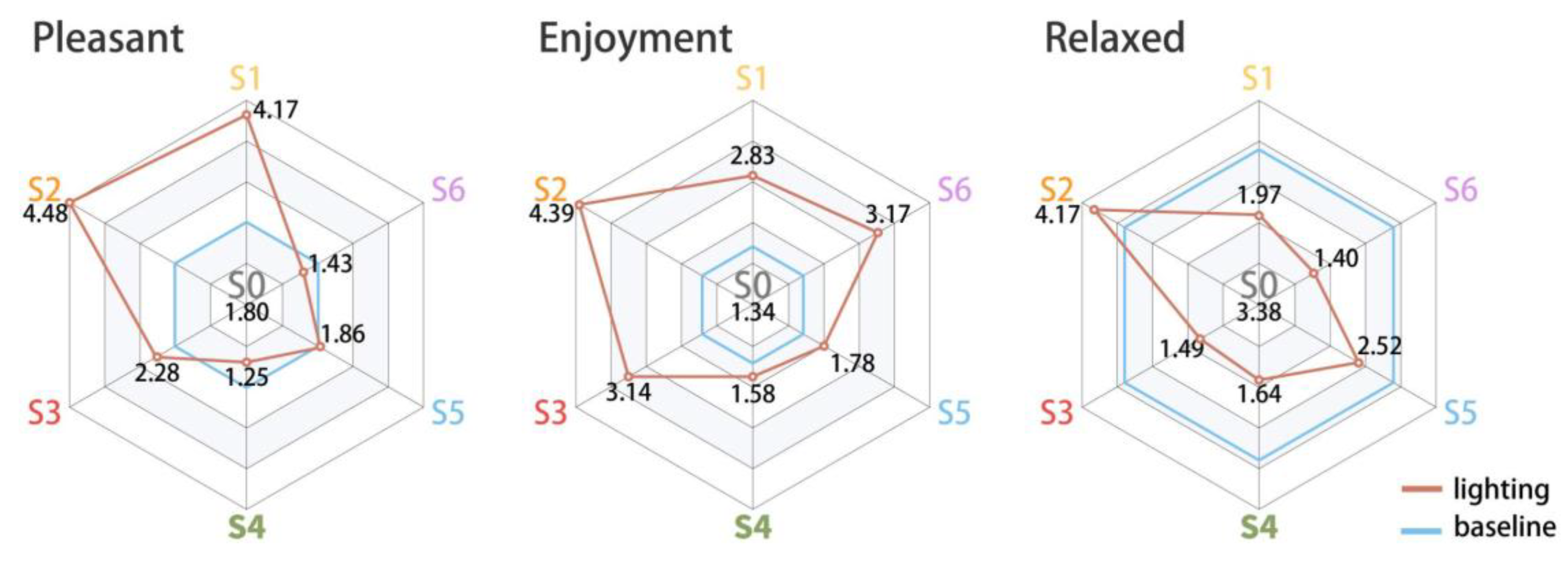

Compared to S0, yellow (S1) and orange (S2) lighting conditions significantly enhanced positive emotions, particularly in terms of pleasantness and enjoyment. This finding aligns with the first part of Hypothesis H1, but contradicts the hypothesis that blue lighting (S5) would have the most significant positive impact on emotions (

Figure 18). Among all lighting conditions, orange light (S2) exhibited the most prominent effect in enhancing pleasantness and enjoyment, emphasizing the role of warm-colored lighting in promoting positive emotions in snowy landscapes [

29]. However, this result differs from H. Lee’s study [

28], which found blue light to be the most pleasant. This difference may stem from two factors: H. Lee’s experiment involved a pure light color environment, whereas in this study, S0 (the snow surface reflecting the sky color) combined with the lighting colors to form the experimental scenes. In this case, the snow surface in S0 reflected the blue sky, making the S0 scene appear deep blue, while S1-S6 were created by overlaying the lighting colors onto the blue-tinted snow surface of S0, making them different from H. Lee’s single-color experimental conditions.The snowy landscape itself has a naturally blue undertone, so when blue light is added, the cool color tones are further intensified, which in turn reduces positive emotions. Additionally, cultural differences and long-term environmental adaptation may also contribute to this difference. In northeastern regions, winters are harsh and prolonged, and blue lighting may have a stronger psychological association with "coldness" and "gloominess". As a result, it fails to induce the same relaxation or enjoyment effects as it might in purely indoor environments.

Additionally, to make the light colors more pronounced, this experiment selected an evening outdoor snowy landscape as the baseline scene (S0). The purpose of this was to enhance the visibility of the light colors, but it also resulted in a darker background, which induced certain blue emotions in participants. For example, a dimly lit environment can evoke feelings of worry, as reflected in

Figure 11, where S0 showed a notable level of "Worry" emotion. When warm-colored lighting was added to the cool and dim evening snow scene, it created a strong contrast and visual impact, leading to a psychological perception of warmth and comfort. Among warm colors, orange is widely recognized in color psychology as the warmest color [

40], often associated with high-arousal imagery such as sunlight and fire. Additionally, as the complementary color of blue, orange may have helped reduce the fear-inducing effects of the dark blue background in S0, making it the most effective color in enhancing positive emotions in this study. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that warm colors, compared to cool colors, significantly enhance positive emotions in certain environmental contexts [

29,

31]. Similarly, yellow (S1), as the second warmest color after orange, significantly enhanced positive emotions compared to S0 (no artificial lighting), but its effect was slightly lower than that of S2 (orange light), reinforcing this possibility. It is important to note that cultural differences influence the interpretation of yellow. For instance, in East Asian cultures, yellow is often associated with "nobility" and "warmth", whereas in some Western contexts, it can symbolize "caution" or "danger". However, based on the quantitative results of this study, yellow lighting in a winter snow landscape still tended to evoke positive emotions.

This finding has important implications for urban lighting design practices, highlighting the significance of the interaction between background color and lighting color. In winter urban environments, well-planned lighting design can play a crucial role in enhancing citizens' Emotional Well-being. For example, if the goal is to enhance positive emotions in cold outdoor environments, warm-colored lighting is generally more effective than cool-colored lighting. However, this does not mean that cool-colored lighting is ineffective in all contexts. For instance, blue or green lighting in summer nights or water landscapes may evoke positive perceptions of coolness and tranquility. Therefore, lighting design should take into account spatial environments, seasonal characteristics, and the psychological expectations of the target audience, allowing for flexible selection and combination of lighting colors to create an optimal emotional impact.

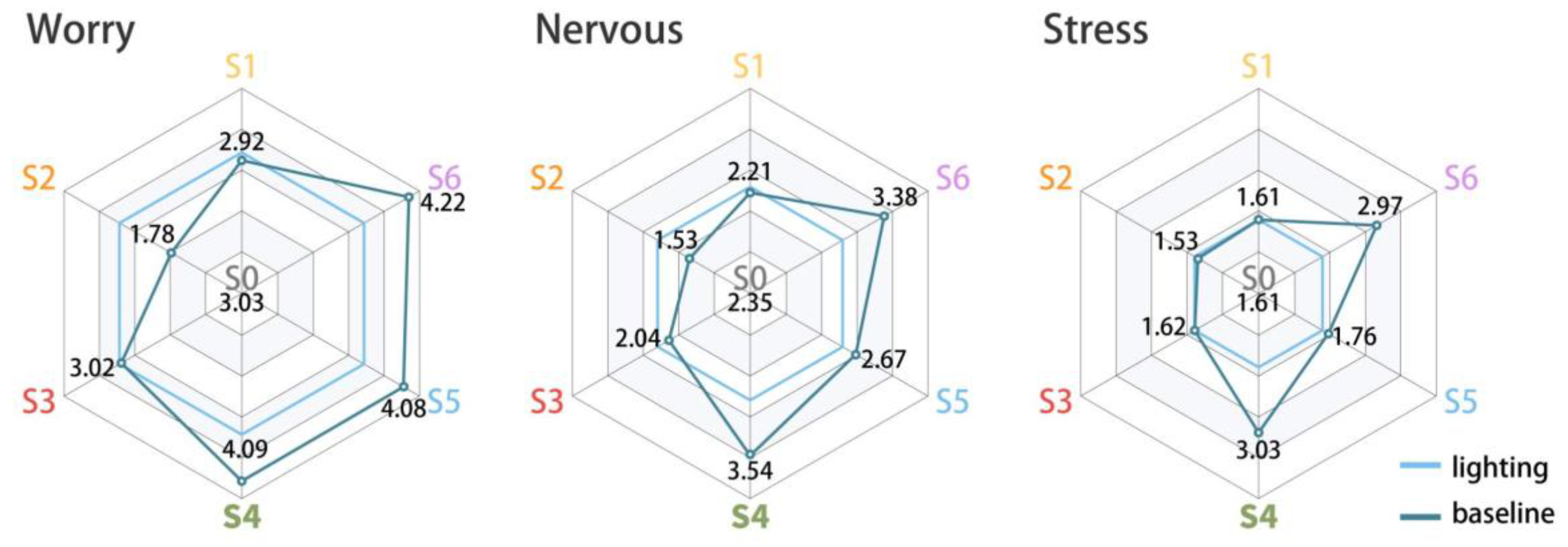

4.3. The Impact of Light Color on Blue Emotions in Emotional Well-being

Compared to the baseline scene (S0), green light (S4) and blue light (S5) significantly increased worry, nervousness, and stress, which aligns with H2 but contradicts the hypothesis that red light (S3) would have the most significant impact on blue emotions (

Figure 19). Among them, green light (S4) had the most pronounced effect on worry (Worry) and nervousness (Nervous). This finding contradicts H. Lee's study [

28], which suggested that cool-colored lighting, such as green and blue, has a lesser impact on blue emotions. While previous research has indicated that green light in indoor settings or natural vegetation backgrounds can induce relaxation and a sense of security, in the deep blue snowy landscape simulated in this study, the overlay of green light onto the background color may have resulted in an overall perception of "gloominess," "coldness," or "dullness," thereby amplifying blue emotions. This phenomenon also suggests that the emotional impact of color is highly context-dependent, influenced by background, brightness, cultural expectations, and personal experiences. Therefore, it is inappropriate to make absolute statements about a particular color being inherently positive or blue.

S4 and S5 were created by combining the deep blue surface color of S0 (which reflects the evening sky) with green and blue lighting, respectively, as shown in

Figures 1, 7, and 8. As explained earlier in

Section 4.2, S0, representing an evening scene, had a dark background (deep blue), which induced some level of worry in participants due to its dim atmosphere. When S4 (green light) and S5 (blue light) were applied to S0, the cold color tones became even more pronounced, potentially amplifying blue emotions. When blue light is used in outdoor nighttime environments, especially against a deep blue winter snow background, it may further trigger associations with "coldness," "emptiness," and "distance." This association could have an exacerbating effect for individuals at risk of seasonal affective disorder or those under high psychological stress. Research by Warakul Tantanatewin et al. [

31] on retail spaces also suggests that cool-colored lighting enhances negative environmental perceptions, creating a sense of "alienation", which aligns with the findings of this study. However, for specific events aiming to highlight the "coolness" or "technological aesthetics" of ice and snow, such as ice sculpture exhibitions or festive celebrations, this effect may not be problematic and could even be seen as a stimulating and creative expression.

This finding offers important implications for urban lighting design practice, particularly in winter urban environments, where appropriate lighting strategies can help prevent the deterioration of citizens' Emotional Well-being. In spaces that require a sense of comfort and safety—such as residential neighborhoods, primary pedestrian commuting routes, and elderly communities—the extensive use of cool-colored lighting should be approached with caution. Such lighting may inadvertently heighten residents’ feelings of tension and worry, even if not immediately apparent. For nighttime economic activities or cultural events, blue-green tones are sometimes viewed as symbols of elegance or calmness, and are often applied in museums or artistic corridors using low-intensity lighting to create a mysterious atmosphere. However, in the absence of clear safety indicators or adequate visual supplementation from the surrounding environment, such lighting conditions may induce excessive blue emotional responses. When cool-colored lighting is necessary for specific design goals (e.g., emphasizing an artistic ambiance or brand identity), it is advisable to incorporate supportive elements such as localized warm-colored fill lighting, moderate increases in ambient brightness, or the addition of vegetation and decorative objects. These strategies can help alleviate perceptions of excessive coldness or darkness, and thereby reduce the risk of inducing blue emotions in public users.

4.4. The Dual Emotional Effect of Lighting

The purple lighting condition (S6) in this study exhibited a dual effect: on the one hand, it significantly increased enjoyment, while on the other, it notably heightened worry, nervousness, and stress, demonstrating a clear "simultaneous enhancement of both positive and blue emotions" effect, as shown in

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17. This finding supports Hypothesis H3, which suggests that certain lighting colors may enhance positive emotions while also amplifying blue emotions. In color psychology, purple is often considered a color of duality, associated with "romance, mystery, and nobility" as well as "gloominess and nervousness." Its wavelength spectrum lies between the red and blue ends of the visible light spectrum, potentially combining the arousing qualities of red with the cool, detached qualities of blue, leading to differentiated emotional arousal responses. In an evening snow landscape with a bluish background, purple light overlays onto the deep blue environment, creating a "hazy and profound" visual effect. This combination may draw attention while also making the environment more difficult to perceive, increasing the sense of ambiguity and spatial uncertainty. If an individual experiences reduced control over their surroundings, they may be more prone to feelings of nervousness and worry.

Some lighting colors, such as orange (S2), significantly enhanced positive emotions while having little impact on blue emotions, whereas others, like purple (S6), exhibited a dual effect—increasing both positive and blue emotions. This dual effect suggests that lighting color is not merely a catalyst for emotions, but that its impact is influenced by multiple factors, including individual psychological associations with colors and the environmental background. From a neurophysiological perspective, purple is considered a high-arousal color in certain cultural contexts, potentially triggering physiological responses such as increased heart rate or greater changes in skin conductance. Some researchers classify purple as a color that easily induces emotional fluctuations. Regarding its effect on amplifying blue emotions, the participants in this study were all Chinese, aligning with H. Lee's study [

28], which found that Asians tend to have a lower acceptance of purple for positive emotions compared to Caucasians. In contrast, European populations are more likely to associate purple with "mystery" or "romance."

For lighting design, this suggests that purple light has high "stylization" potential in winter outdoor environments, but also carries a greater risk of emotional fluctuation. In contexts such as festivals, artistic installations, or commercial performances, purple light can create a "dazzling" and "distinctive" experience, evoking positive emotions and enhancing the attraction of an event. However, in urban public spaces, residential areas, or transportation hubs that require a sense of security, widespread use of purple lighting may make some individuals feel uneasy or uncomfortable. Balancing "artistic atmosphere" and "universal comfort" in design requires precise spatial planning and strategic light distribution. For example: Purple lighting can be concentrated in stage areas, art exhibition zones, or interactive installations, allowing people to choose whether to enter the immersive space. However, in main pedestrian routes or public relaxation areas, warm or neutral lighting should be used to maintain a baseline environment of safety and relaxation.

4.5. Research Limitations and Future Directions

This study provides insights into the effects of lighting colors in snowy landscapes on Emotional Well-being, yet certain limitations should be considered. The sample for this study was drawn from a single cultural background, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Cultural differences influence color perception and emotional responses, as prior studies have suggested that certain populations associate specific colors with distinct emotional meanings. Future research should incorporate participants from a wider range of cultural and regional backgrounds to examine the cross-cultural characteristics of lighting color effects on Emotional Well-being. The assessment of Emotional Well-being relied on self-report questionnaires, which, while widely used, may be influenced by individual biases and subjective interpretations. Incorporating physiological measures, such as heart rate variability (HRV) and skin conductance response (SCR), could enhance the reliability of emotional assessments by providing objective indicators of affective states. A multimodal approach integrating both self-reports and physiological data would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how lighting colors impact emotions. The study focused exclusively on six lighting colors, without considering brightness (luminance) and saturation (purity) as independent variables. In real-world environments, lighting perception is shaped by complex interactions between hue, luminance, and saturation, which could lead to varying emotional effects. Further investigations should examine the combined influence of multiple lighting attributes to establish a more ecologically valid framework for assessing emotional responses to artificial lighting. Additionally, temporal variations in natural light were not accounted for in this study. Given that light conditions fluctuate throughout the day, changes in natural illumination may interact with artificial lighting to shape emotional responses. Future research should explore the time-dependent effects of lighting on emotions, particularly in dynamic outdoor environments, to capture the interplay between circadian rhythms, environmental lighting, and psychological well-being. Despite these limitations, the findings contribute to the growing body of research on the psychological impact of lighting in outdoor winter settings. Addressing these limitations in future studies would facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of how lighting design can be optimized to enhance Emotional Well-being in urban environments.

4.6. Research Limitations and Future Directions

This study reveals the differentiated emotional effects of various lighting colors in winter outdoor environments and snowy landscapes, offering valuable references for urban lighting planning and design. Warm-colored light sources (such as orange and yellow) effectively enhance pleasantness and enjoyment in cold and dim environments, demonstrating a strong positive impact on Emotional Well-being. These light sources not only provide "visual warmth" at the physiological level but may also evoke positive psychological associations with sunlight and fire, thereby increasing the attractiveness and comfort of public spaces. This characteristic makes warm lighting particularly suitable for high-traffic nighttime areas, commercial districts, and social outdoor spaces, such as city plazas, shopping streets, and public gathering spots, where creating a welcoming and inviting atmosphere is essential. In contrast, cool-colored lighting (such as green and blue) in dark or bluish-toned snowy landscapes may intensify blue emotions, leading to increased worry, nervousness, and stress. Since cold-toned lighting can be further amplified in low-temperature environments, it is more appropriate for artistic or festive events that seek to create a specific aesthetic or experiential atmosphere. However, in public transit pathways, low-traffic nighttime areas, or spaces with high security demands, excessive use of cold lighting should be carefully considered, as it may heighten psychological discomfort and unease among nighttime pedestrians.

The "dual effect" of purple lighting was particularly evident in this study. On one hand, it elicited high levels of enjoyment and novelty, while on the other, it intensified feelings of worry and nervousness. This emotionally complex stimulation may enhance the attractiveness of ice and snow-themed tourism and cultural events, as it can create a distinctive visual experience and a sense of "mystery" for visitors. However, in residential areas or public spaces where psychological stability is a priority, the extensive use of purple lighting may pose potential psychological risks. To mitigate these concerns, lighting design should consider localized and artistic applications, aligning with pedestrian flow characteristics and functional contexts. This approach ensures that individuals encounter high-arousal visual stimuli, such as purple lighting, voluntarily and consciously, rather than being passively immersed in large-scale purple-lit environments.

The adaptability of lighting colors across different times of the day and weather conditions also warrants further attention. During evening and late-night hours, when temperatures drop further and individuals' alertness levels decrease, there is a greater preference and need for warm-colored lighting to counteract the psychological effects of coldness and spatial emptiness. In contrast, during daytime or periods with ample natural light, cool-colored lighting can be more flexibly integrated into urban landscapes to create a refreshing or high-tech ambiance. Intelligent lighting systems offer a viable technological solution by enabling automatic sensing and pre-programmed adjustments of light color, brightness, and projection direction. This allows different urban areas and time periods to dynamically adapt lighting configurations based on factors such as temperature, pedestrian flow, and activity type. Such a user-centered dynamic lighting system has the potential to balance energy efficiency and aesthetic appeal, while simultaneously protecting and enhancing Emotional Well-being.

Considering cultural and environmental differences, interdisciplinary and cross-regional field studies could further improve the rationality and feasibility of lighting strategies. By integrating methodologies from environmental psychology, architecture, urban planning, and public health, a deeper understanding of the comprehensive impact of lighting and snowy landscapes on emotions and well-being could be achieved. If such an approach is adopted, it may lead to the development of refined urban lighting guidelines, providing scientifically grounded and human-centered solutions for improving nighttime spaces in cold-climate cities or regions with long winters. This would help achieve the goal of "human-centered" winter lighting and urban health management, offering a more people-oriented and scientifically informed approach to enhancing urban environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L. and H.Z.; methodology, H.Z.; software, H.Z. and N.L.; validation, H.Z., N.L. and Z.F.; formal analysis, H.Z. and N.L.; investigation, H.Z. and N.L.; resources, P.L.; data curation, H.Z.; writing---original draft preparation, H.Z. and G.L.; writing---review and editing, H.Z.; visualization, H.Z. and P.L.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, P.L.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

No artificial lighting scene (S0) and lighting color scenes (S1-S6).

Figure 1.

No artificial lighting scene (S0) and lighting color scenes (S1-S6).

Figure 2.

Experimental environment plan.

Figure 2.

Experimental environment plan.

Figure 3.

Experimental site photos.

Figure 3.

Experimental site photos.

Figure 4.

Creation of the non-artificial light scene (S0). (a) shows the original snowy landscape image, source: StockCake (Public Domain); (b) shows the S0 scene, which was adjusted using Photoshop to simulate a no lighting condition with reduced brightness.

Figure 4.

Creation of the non-artificial light scene (S0). (a) shows the original snowy landscape image, source: StockCake (Public Domain); (b) shows the S0 scene, which was adjusted using Photoshop to simulate a no lighting condition with reduced brightness.

Figure 5.

Import scene 0 (S0) into the 3D software Maya for modeling.

Figure 5.

Import scene 0 (S0) into the 3D software Maya for modeling.

Figure 6.

CIE Standard Colorimetric Observers. (a) color space of different color modes. (b) sRGB color space.

Figure 6.

CIE Standard Colorimetric Observers. (a) color space of different color modes. (b) sRGB color space.

Figure 7.

Six lighting color layers rendered through 3D software.

Figure 7.

Six lighting color layers rendered through 3D software.

Figure 8.

The 3D-rendered lighting color layers are composited with the scene S0 that has no artificial lighting, resulting in snowscape scenes (S1-S6) with lighting colors.

Figure 8.

The 3D-rendered lighting color layers are composited with the scene S0 that has no artificial lighting, resulting in snowscape scenes (S1-S6) with lighting colors.

Figure 9.

Flowchart of SAM scale analysis.

Figure 9.

Flowchart of SAM scale analysis.

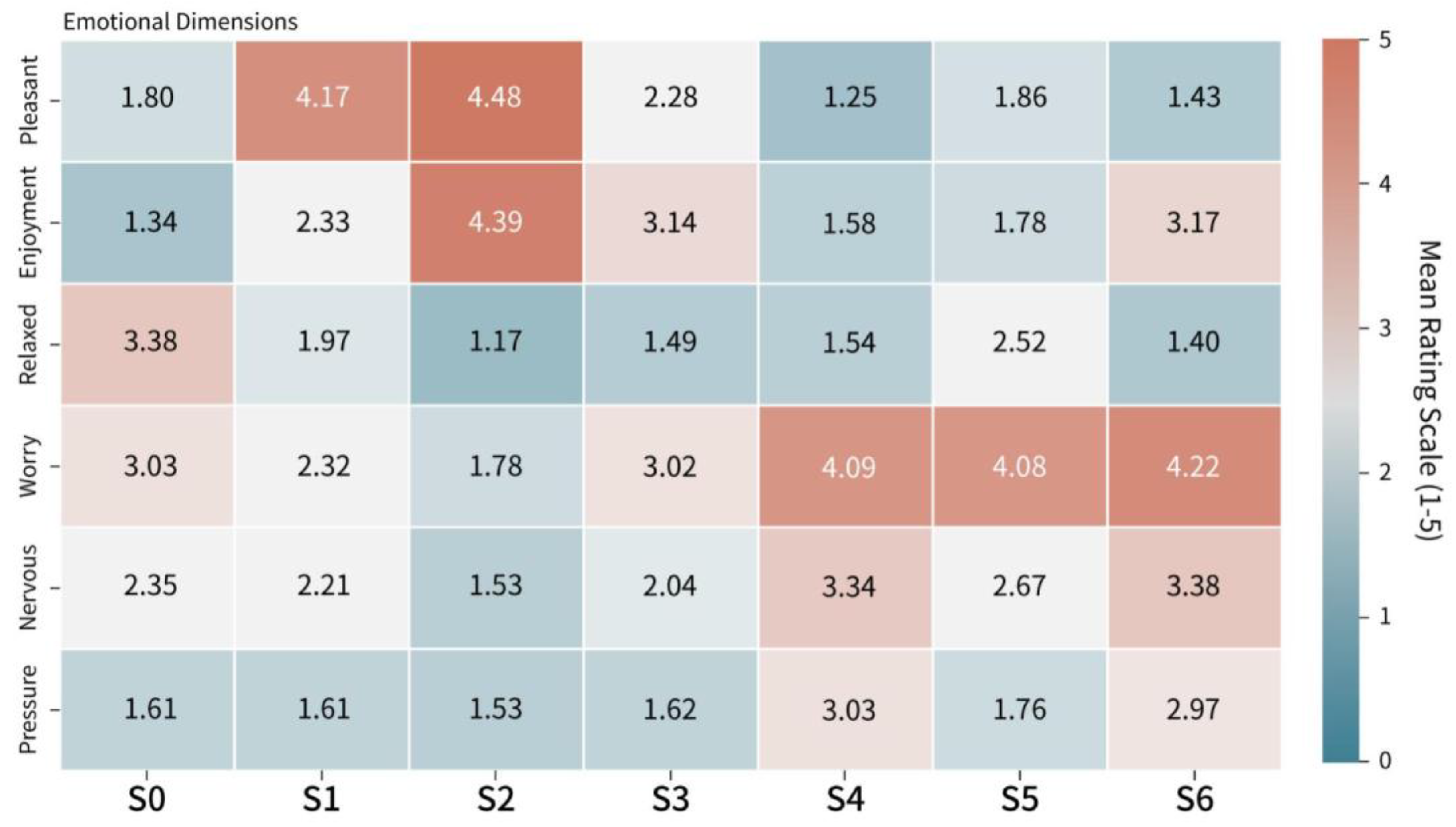

Figure 10.

Heatmap of interaction effects between lighting conditions and emotional scores.

Figure 10.

Heatmap of interaction effects between lighting conditions and emotional scores.

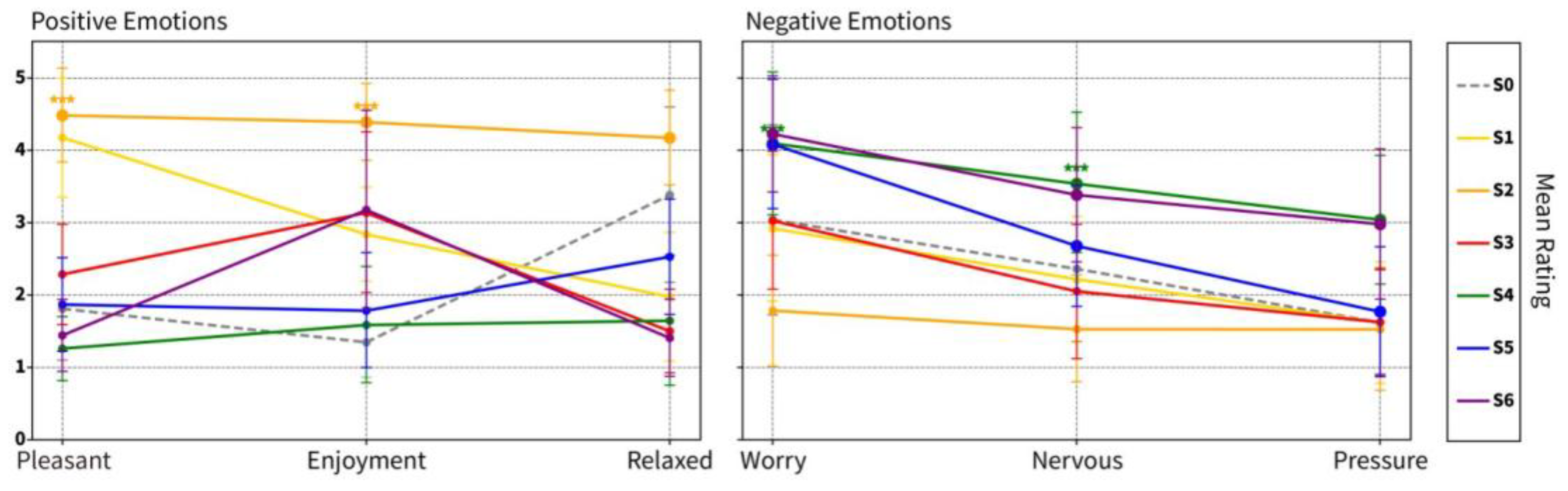

Figure 11.

Interaction trend chart of emotional scores across different lighting conditions.

Figure 11.

Interaction trend chart of emotional scores across different lighting conditions.

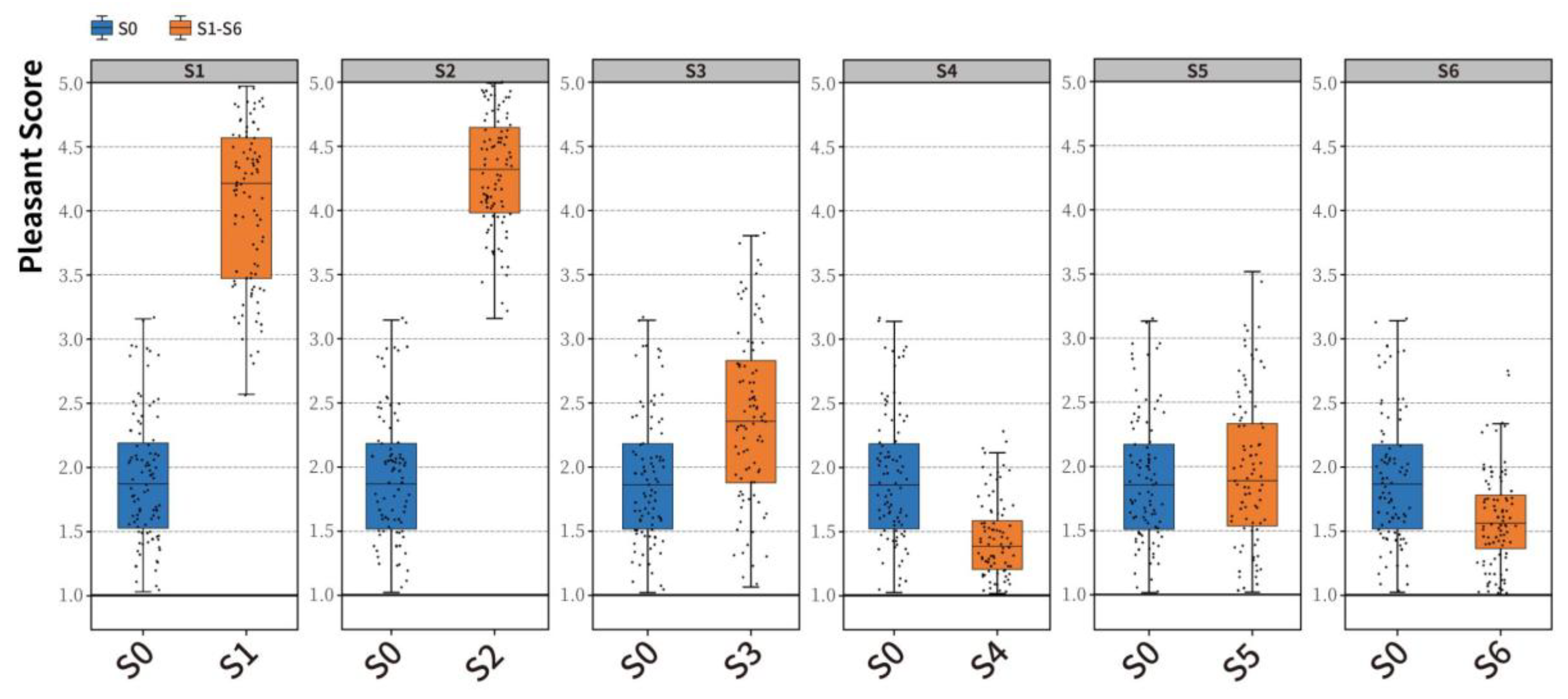

Figure 12.

Compare the positive (Pleasant Scores) affects of t-test (S1-S6) between S0 and paired samples in front of each lighting scene.

Figure 12.

Compare the positive (Pleasant Scores) affects of t-test (S1-S6) between S0 and paired samples in front of each lighting scene.

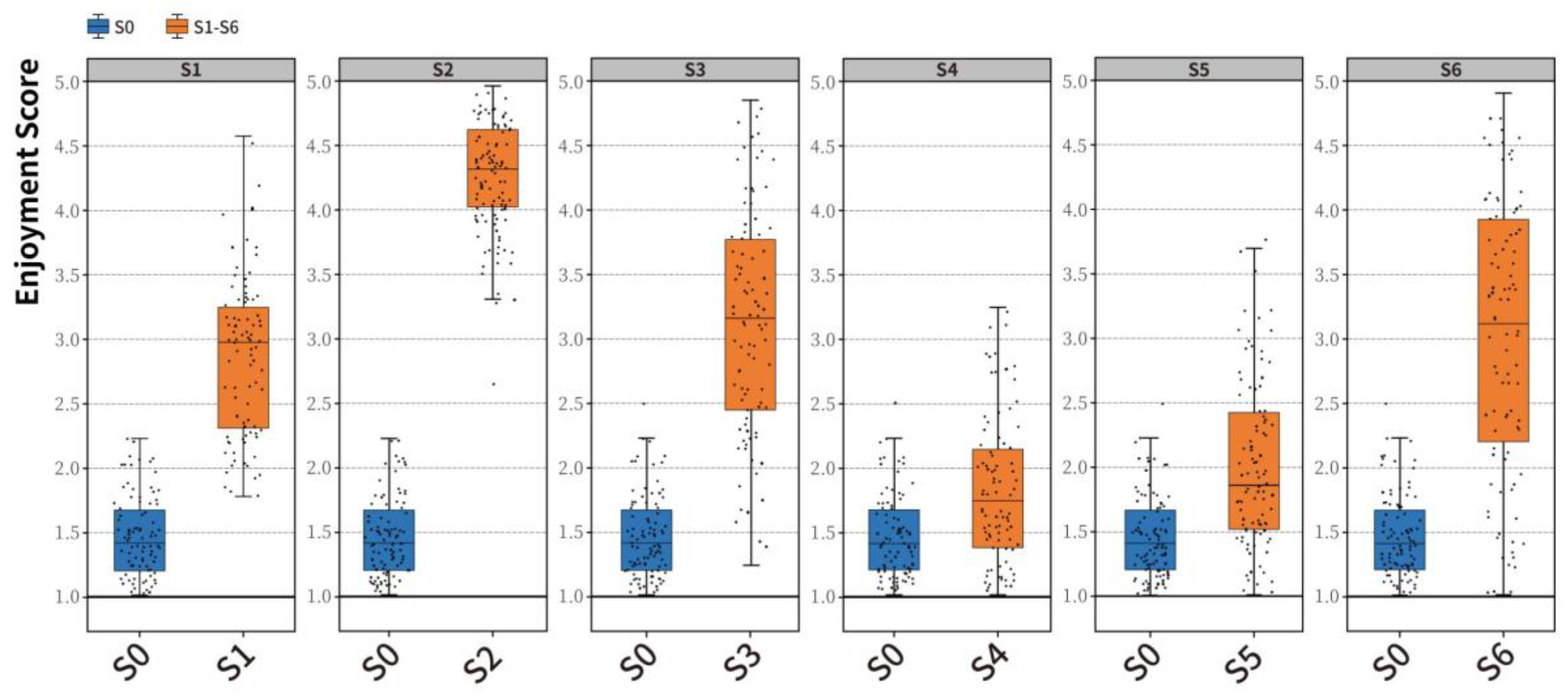

Figure 13.

Compare the positive (Enjoyment Scores) affects of t-test (S1-S6) between S0 and paired samples in front of each lighting scene.

Figure 13.

Compare the positive (Enjoyment Scores) affects of t-test (S1-S6) between S0 and paired samples in front of each lighting scene.

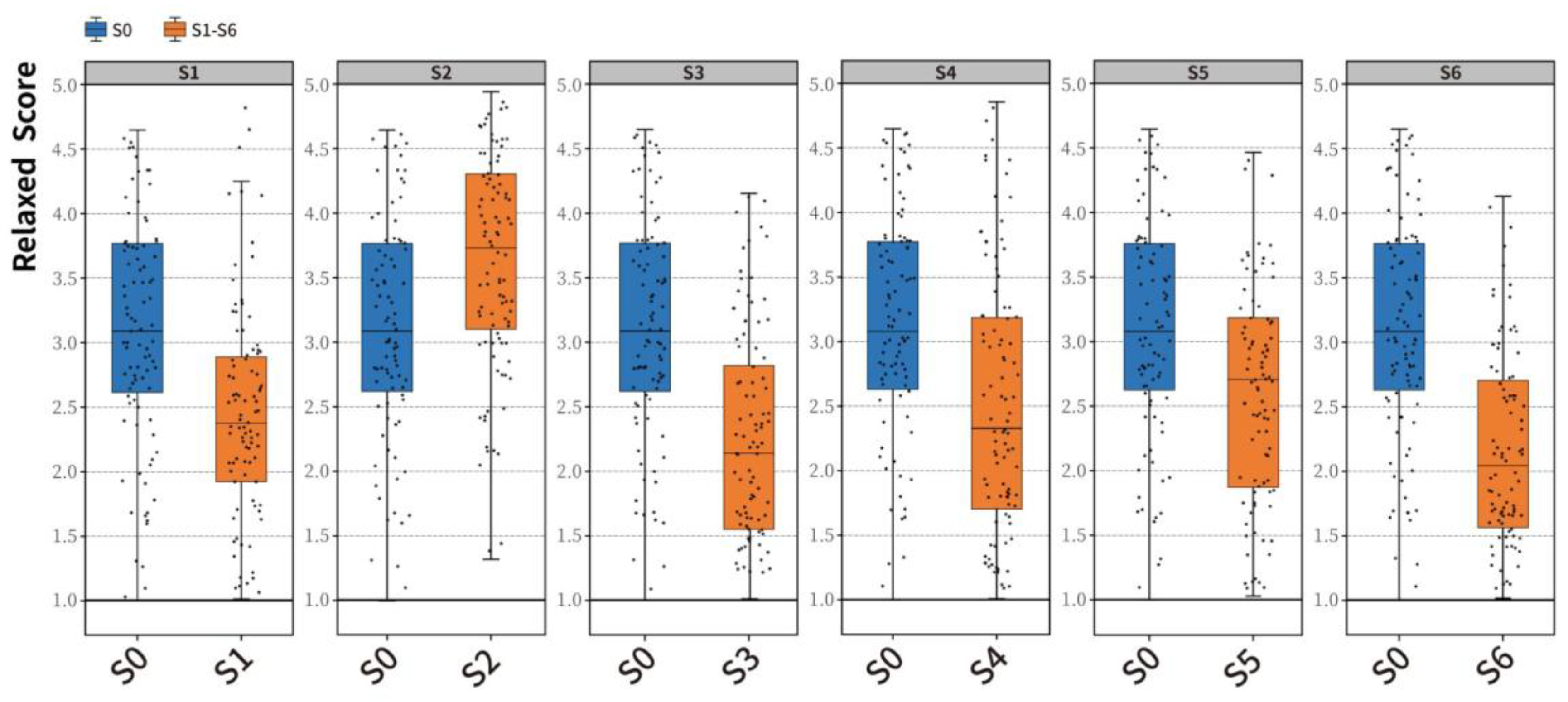

Figure 14.

Compare the positive (Relaxed Scores) affects of t-test (S1-S6) between S0 and paired samples in front of each lighting scene.

Figure 14.

Compare the positive (Relaxed Scores) affects of t-test (S1-S6) between S0 and paired samples in front of each lighting scene.

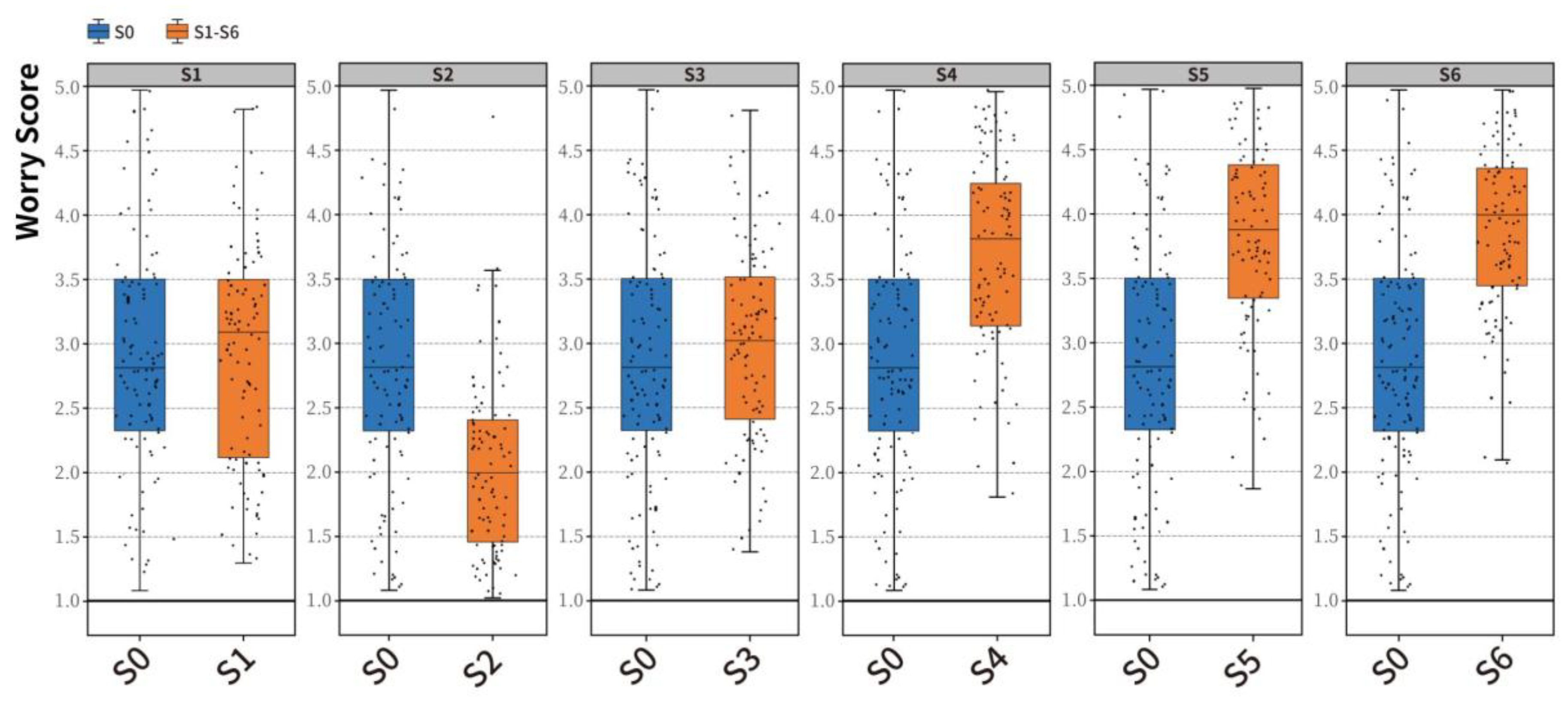

Figure 15.

Paired sample t-test control of blue affects (Worry Scores) between S0 and various lighting scenes (S1-S6).

Figure 15.

Paired sample t-test control of blue affects (Worry Scores) between S0 and various lighting scenes (S1-S6).

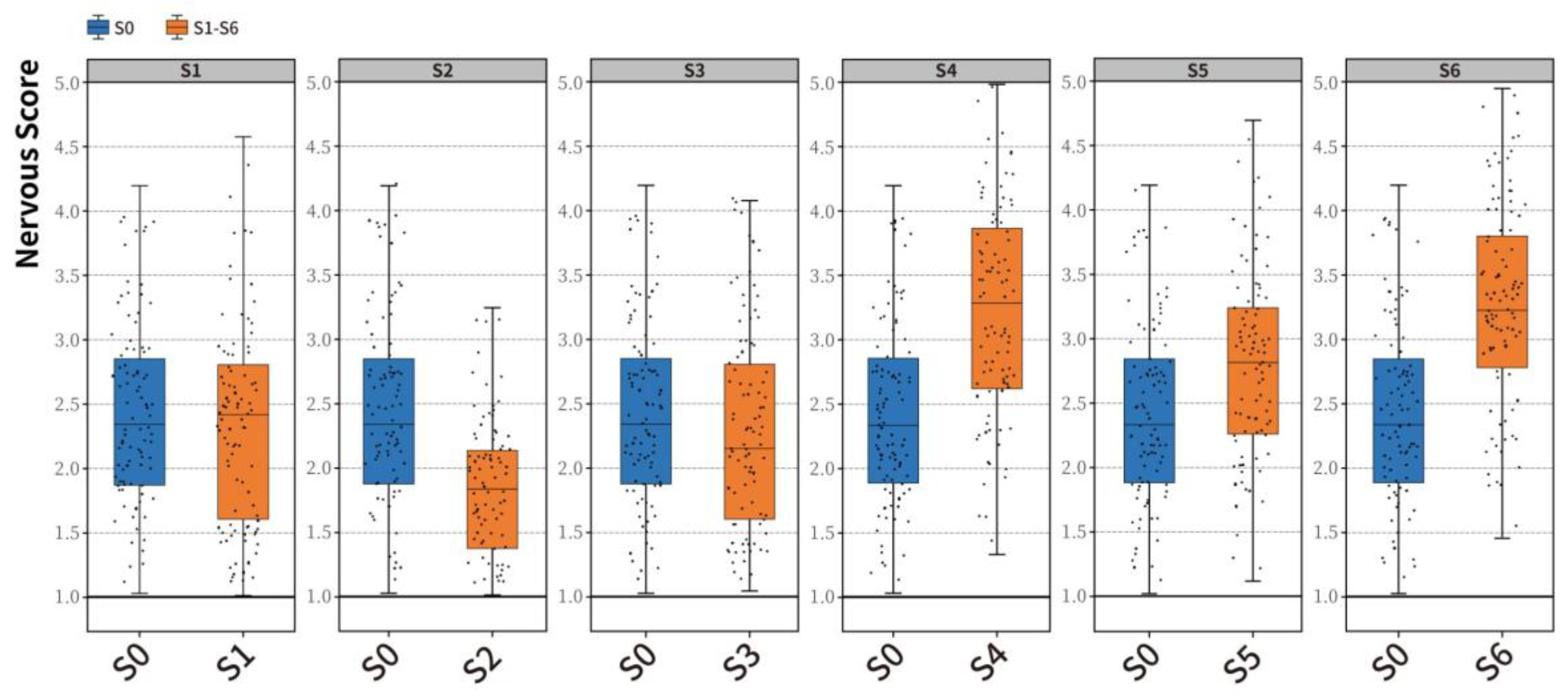

Figure 16.

Paired sample t-test control of blue affects (Nervous Scores) between S0 and various lighting scenes (S1-S6).

Figure 16.

Paired sample t-test control of blue affects (Nervous Scores) between S0 and various lighting scenes (S1-S6).

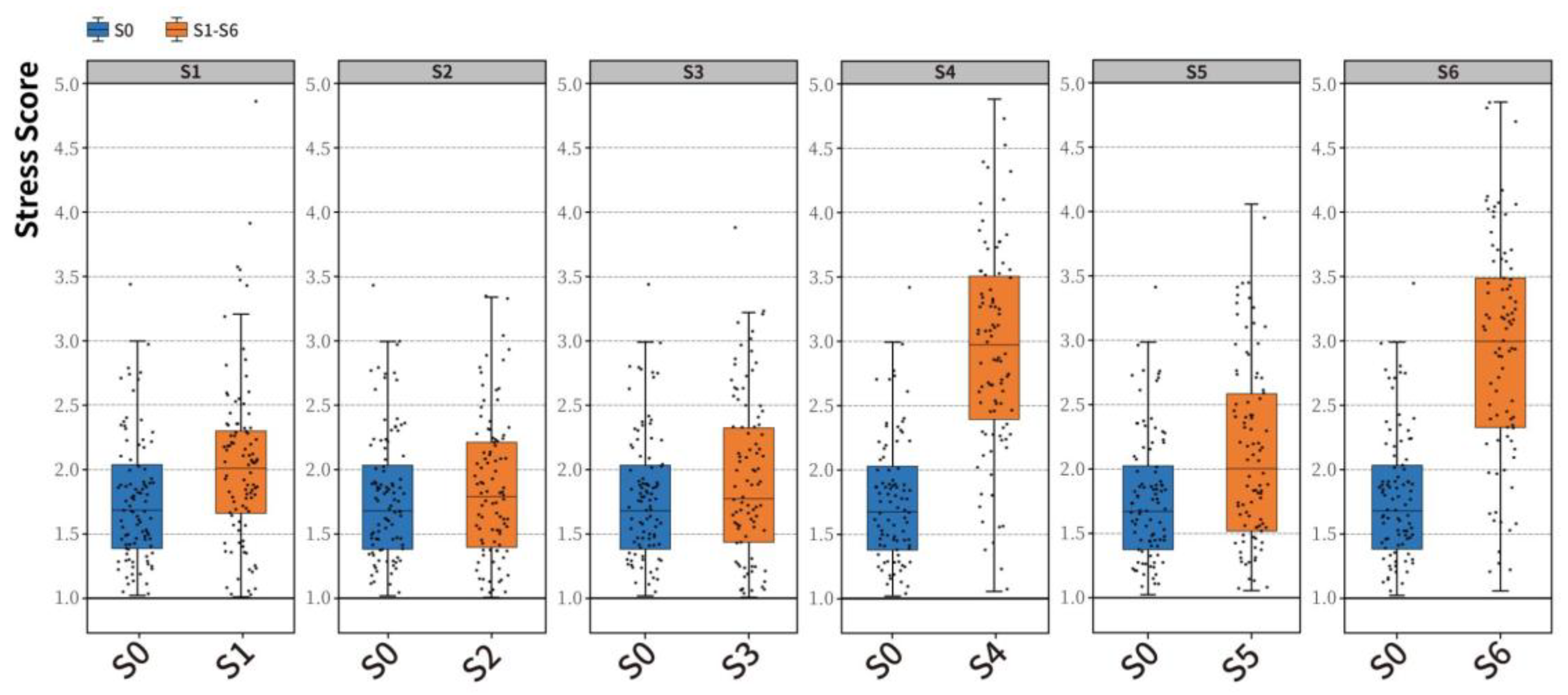

Figure 17.

Paired sample t-test control of blue affects (Stress Scores) between S0 and various lighting scenes (S1-S6).

Figure 17.

Paired sample t-test control of blue affects (Stress Scores) between S0 and various lighting scenes (S1-S6).

Figure 18.

The impact of light color on positive emotions in Emotional Well-being.

Figure 18.

The impact of light color on positive emotions in Emotional Well-being.

Figure 19.

The impact of light color on blue emotions in Emotional Well-being.

Figure 19.

The impact of light color on blue emotions in Emotional Well-being.

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Participants.

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Participants.

| Age |

Province |

Count |

Characteristi |

Category |

Count |

| 18-55 |

Guangdong |

3 |

Gender |

Male |

41 |

| |

Hebei |

8 |

|

Female |

54 |

| |

Heilongjiang |

39 |

Marriage |

Married |

69 |

| |

Hubei |

3 |

|

Unmarried |

26 |

| |

Hunan |

2 |

Education |

Below high school |

19 |

| |

Jilin |

15 |

|

junior college |

31 |

| |

Jiangxi |

2 |

|

undergraduate |

34 |

| |

Liaoning |

15 |

|

Master's degree or above |

11 |

| |

Shandong |

8 |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Demographic information of participants.

Table 2.

Demographic information of participants.

| Emotion |

S0 |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

S4 |

S5 |

S6 |

| Pleasant |

1.80 ± 0.71 |

4.17 ± 0.83 |

4.48 ± 0.65 |

2.28 ± 0.69 |

1.25 ± 0.44 |

1.86 ± 0.65 |

1.43 ± 0.50 |

| Enjoyment |

1.34 ± 0.48 |

2.83 ± 0.65 |

4.39 ± 0.53 |

3.14 ± 1.11 |

1.58 ± 0.81 |

1.78 ± 0.79 |

3.17 ± 1.38 |

| Relaxed |

3.38 ± 1.21 |

1.97 ± 0.89 |

4.17 ± 0.66 |

1.49 ± 0.58 |

1.64 ± 0.90 |

2.52 ± 0.80 |

1.40 ± 0.53 |

| Worry |

3.03 ± 1.32 |

2.92 ± 1.01 |

1.78 ± 0.77 |

3.02 ± 0.96 |

4.09 ± 0.99 |

4.08 ± 0.90 |

4.22 ± 0.80 |

| Nervous |

2.35 ± 1.00 |

2.21 ± 0.87 |

1.53 ± 0.74 |

2.04 ± 0.93 |

3.54 ± 0.97 |

2.67 ± 0.83 |

3.38 ± 0.93 |

| Pressure |

1.61 ± 0.73 |

1.61 ± 0.84 |

1.53 ± 0.85 |

1.62 ± 0.73 |

3.03 ± 0.89 |

1.76 ± 0.90 |

2.97 ± 1.04 |

Table 3.

Main effects and interaction effects (Scene × Emotional Dimension) analysis results.

Table 3.

Main effects and interaction effects (Scene × Emotional Dimension) analysis results.

| Effect Source |

F-value |

p-value |

)

|

Effect Size Interpretation |

| Main Effect: Scene (S1-S6) |

54.478 |

<0.001 |

0.077 |

Moderate Effect |

| Main Effect: Emotional Dimension |

165.348 |

<0.001 |

0.173 |

Large Effect |

| Interaction: Scene × Emotional Dimension |

141.411 |

<0.001 |

0.518 |

Large Effect |