Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

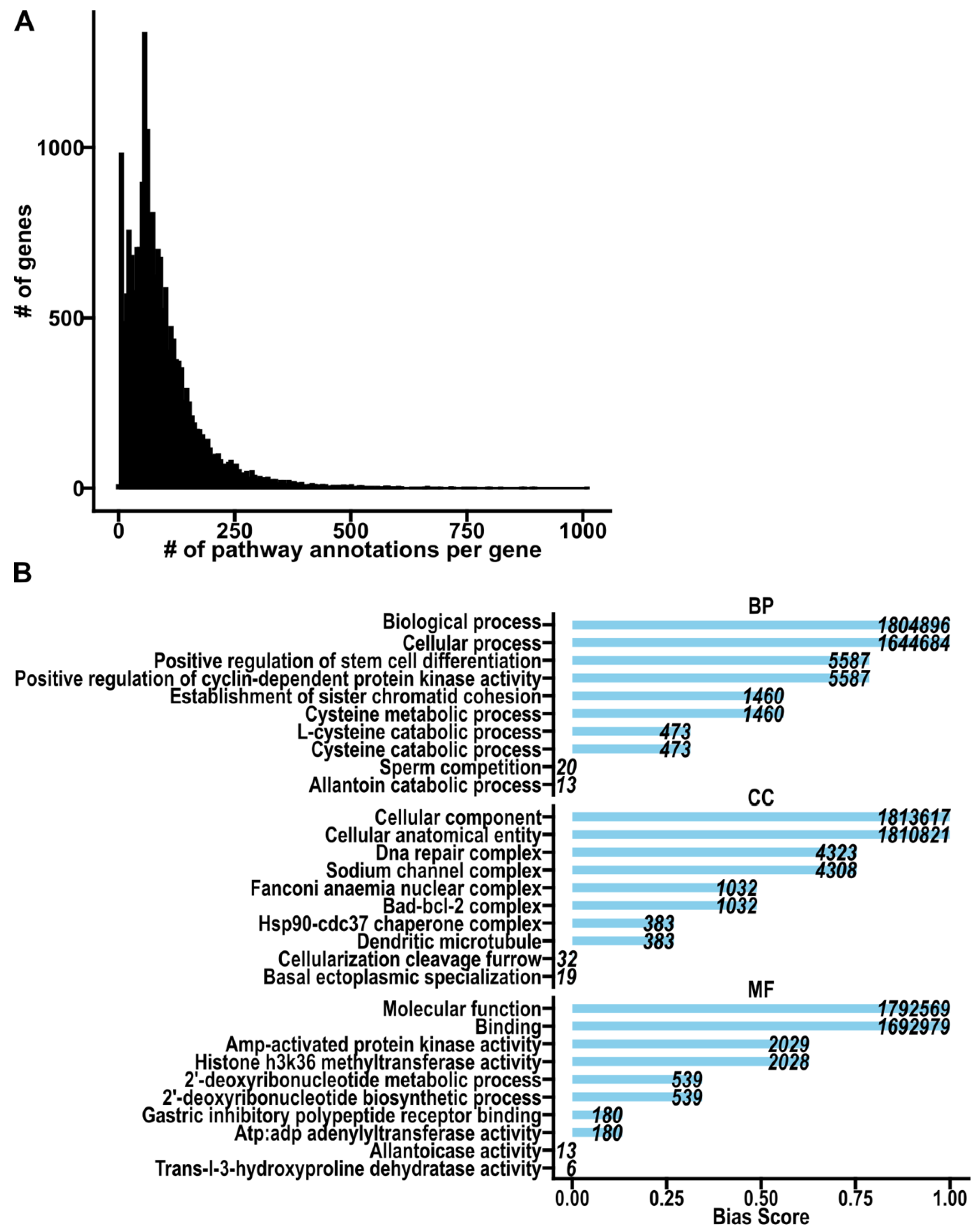

Key Challenges to Pathway Analysis

Pathway Annotation

| Gene | # of Pathways |

|---|---|

| TGFB1 transforming growth factor beta 1 | 1010 |

| CTNNB1 catenin beta 1 | 894 |

| ACADL acyl-CoA dehydrogenase long chain | 120 |

| ACTBL2 actin beta like 2 | 120 |

| ABCA6 ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 6 | 72 |

| ACKR1 atypical chemokine receptor 1 (Duffy blood group) | 72 |

| ABCF3 ATP binding cassette subfamily F member 3 | 44 |

| ADISSP adipose secreted signaling protein | 44 |

| C6orf62 chromosome 6 open reading frame 62 | 2 |

| CTAGE3P CTAGE family member 3, pseudogene | 2 |

| Locus Type | Count |

|---|---|

| pseudogene | 13940 |

| RNA, long non-coding | 5640 |

| RNA, micro | 1912 |

| gene with protein product | 611 |

| RNA, transfer | 591 |

| RNA, small nucleolar | 568 |

| immunoglobulin pseudogene | 202 |

| readthrough | 143 |

| RNA, cluster | 119 |

| fragile site | 116 |

| endogenous retrovirus | 92 |

| T cell receptor gene | 67 |

| RNA, ribosomal | 58 |

| immunoglobulin gene | 55 |

| RNA, small nuclear | 51 |

| region | 46 |

| unknown | 46 |

| T cell receptor pseudogene | 38 |

| RNA, misc | 29 |

| virus integration site | 8 |

| complex locus constituent | 6 |

| RNA, vault | 4 |

| RNA, Y | 4 |

| Tool | Year | Method | Access | Database | Visualization | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REVIGO [91] | 2011 | Semantic | Web | GO | Scatterplots, interactive graph, tree maps | Summarizes GO term lists using semantic similarity and clustering |

| clusterProfiler [94] | 2013 | Semantic | R package | GO, KEGG, DO | Dot plot | Enrichment analysis for GO/KEGG terms and visualization |

| ReCiPa [58] | 2018 | Semantic | R package | KEGG, Reactome | Data tables | Controls redundancy in pathway databases |

| GOGO [93] | 2018 | Semantic | Web, Perl | GO | Data tables | Calculates semantic similarity of GO terms using improved algorithms |

| FunSet [129] | 2019 | Semantic | Web, Standalone | GO | 2D plots | Performs GO enrichment analysis with interactive visualizations |

| GeneSetCluster [130] | 2020 | Semantic | R package | Any | Network graph, dendogram, heatmap | Groups gene-sets post-analysis based on shared genes |

| GOMCL [131] | 2020 | Semantic | Python | GO | Heatmap, Network graph | Clusters GO terms using Markov clustering algorithm |

| GoSemSim [132] | 2020 | Semantic | R package | GO | Data tables | Computes semantic similarity among GO terms for comparison |

| GO-FIGURE! [15] | 2021 | Semantic | Python | GO | Scatterplot | Visualizes GO term similarity with custom scatterplots |

| SimplifyEnrichment [133] | 2022 | Semantic | R package | GO | Heatmap | Clusters with a unique binary cut algorithm. |

| RICHNET [98] | 2019 | Network | R protocol | MSigDB | Network graph | Automated gene-set network creation |

| EnrichmentMap [66] | 2019 | Network | Cytoscape | Any | Interactive network | Detailed enrichment mapping |

| Gscluster [99] | 2019 | Network | Web, R Package | MSigDB | Interactive network | Network-weighted gene-set clustering integrating PPI data |

| aPEAR [101] | 2019 | Network | R package | Any | Network graph | Clustering with automated naming |

| GeneFEAST [100] | 2023 | Network | Web, Python | Any | Heatmap, Dot plot, Upset plot | Highlights multi-enrichment genes |

| vissE [102,103] | 2023 | Network | R package | MSigDB, Any | Network graph | Visualizes higher-order interactions |

| pathlinkR [97] | 2024 | Network | R package | Reactome, MSigDB, InnateDB | Network graph, Volcano plot, Dot plot | Integrated PPI network construction |

| PAVER [110] | 2024 | Embedding | Web, R package | Any | UMAP, Heatmap, Dot plot | Embedding-based clustering with UMAP for clear pathway visualization |

| Mondrian-Map [113] | 2024 | Embedding | Python | WikiPathways | Mondrian Map | Embedding visualizations highlighting pathway interactions and crosstalk |

| GOsummaries [134] | 2015 | Word Cloud | R package | GO | PCA, Boxplot | Visualizes GO analyses as word clouds and overlays results |

| genesetSV [135] | 2023 | Game Theory | Python | KEGG, MSigDB | Scatterplot | Uses Shapley values for ranking and reducing pathway sets |

| Archetype-Discovery [136] | 2024 |

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) |

MATLAB | MSigDB, Any | Radar, scatter & boxplot, Heatmap | Uses NMF to derive compact archetypal gene-set patterns and their pathway associations |

Visualizing Pathway Findings

Limitations to Pathway Analysis Utility

Discrepancies in Molecular Biology Mislead Validation

Methods for Pathway Analysis Interpretation

Semantic Similarity Based Methods

Network Based Methods

Embedding Based Methods

Applications of Tools for Pathway Interpretation

Choosing the Right Tool for Your Research

Conclusions & Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Glossary

References

- Manzoni, C., et al., Genome, transcriptome and proteome: the rise of omics data and their integration in biomedical sciences. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 2016. 19(2): p. 286-302. [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, T.D., Omics in Systems Biology: Current Progress and Future Outlook. Proteomics, 2021. 21(3-4): p. e2000235. [CrossRef]

- Herr, T.M., et al., A conceptual model for translating omic data into clinical action. Journal of Pathology Informatics, 2015. 6(1): p. 46. [CrossRef]

- García-Campos, M.A., J. Espinal-Enríquez, and E. Hernández-Lemus, Pathway Analysis: State of the Art. Front Physiol, 2015. 6: p. 383. [CrossRef]

- Wegman-Points, L., et al., Subcellular partitioning of protein kinase activity revealed by functional kinome profiling. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12(1): p. 17300. [CrossRef]

- Ramanan, V.K., et al., Pathway analysis of genomic data: concepts, methods, and prospects for future development. Trends Genet, 2012. 28(7): p. 323-32. [CrossRef]

- Krassowski, M., et al., State of the Field in Multi-Omics Research: From Computational Needs to Data Mining and Sharing. Front Genet, 2020. 11(610798): p. 610798. [CrossRef]

- Sboner, A., et al., The real cost of sequencing: higher than you think! Genome Biol, 2011. 12(8): p. 125. [CrossRef]

- D'Adamo, G.L., J.T. Widdop, and E.M. Giles, The future is now? Clinical and translational aspects of "Omics" technologies. Immunol Cell Biol, 2021. 99(2): p. 168-176. [CrossRef]

- Denecker, T. and G. Lelandais, Omics Analyses: How to Navigate Through a Constant DataData Deluge, in Yeast Functional Genomics: Methods and Protocols, F. Devaux, Editor. 2022, Springer US: New York, NY. p. 457-471.

- Bell, G., T. Hey, and A. Szalay, Computer science. Beyond the data deluge. Science, 2009. 323(5919): p. 1297-8. [CrossRef]

- Stead, W.W., et al., Biomedical informatics: changing what physicians need to know and how they learn. Acad Med, 2011. 86(4): p. 429-34. [CrossRef]

- Pita-Juárez, Y., et al., The Pathway Coexpression Network: Revealing pathway relationships. PLOS Computational Biology, 2018. 14(3): p. e1006042. [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D. and G. Agapito, Nine quick tips for pathway enrichment analysis. PLoS Comput Biol, 2022. 18(8): p. e1010348. [CrossRef]

- Reijnders, M.J. and R.M. Waterhouse, Summary visualizations of gene ontology terms with GO-Figure! Frontiers in Bioinformatics, 2021. 1: p. 6. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C., et al., A strategy for evaluating pathway analysis methods. BMC Bioinformatics, 2017. 18(1): p. 453. [CrossRef]

- Searson, P.C., The Cancer Moonshot, the role of in vitro models, model accuracy, and the need for validation. Nature Nanotechnology, 2023. 18(10): p. 1121-1123. [CrossRef]

- Durinikova, E., K. Buzo, and S. Arena, Preclinical models as patients’ avatars for precision medicine in colorectal cancer: past and future challenges. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 2021. 40(1): p. 185. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Uriarte, R., et al., Ten quick tips for biomarker discovery and validation analyses using machine learning. PLOS Computational Biology, 2022. 18(8): p. e1010357. [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, T., et al. Between Biological Relevancy and Statistical Significance - Step for Assessment Harmonization. 2021.

- Committee, E.S., et al., Guidance on the assessment of the biological relevance of data in scientific assessments. EFSA Journal, 2017. 15(8): p. e04970. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y., et al., Quantifying the impact of public omics data. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1): p. 3512. [CrossRef]

- Misra, B.B., et al., Integrated omics: tools, advances and future approaches. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology, 2019. 62(1): p. R21-R45. [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Fernández, D., et al., PathMe: merging and exploring mechanistic pathway knowledge. BMC Bioinformatics, 2019. 20(1): p. 243. [CrossRef]

- Wieder, C., et al., PathIntegrate: Multivariate modelling approaches for pathway-based multi-omics data integration. PLOS Computational Biology, 2024. 20(3): p. e1011814. [CrossRef]

- Canzler, S. and J. Hackermüller, multiGSEA: a GSEA-based pathway enrichment analysis for multi-omics data. BMC Bioinformatics, 2020. 21(1): p. 561. [CrossRef]

- Ivanisevic, T. and R.N. Sewduth, Multi-Omics Integration for the Design of Novel Therapies and the Identification of Novel Biomarkers. Proteomes, 2023. 11(4): p. 34. [CrossRef]

- Mohr, A.E., et al., Navigating Challenges and Opportunities in Multi-Omics Integration for Personalized Healthcare. Biomedicines, 2024. 12(7): p. 1496. [CrossRef]

- Conroy, G., Retractions caused by honest mistakes are extremely stressful, say researchers. Nature, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M., et al., Opening the black box of article retractions: exploring the causes and consequences of data management errors. R Soc Open Sci, 2024. 11(12): p. 240844. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D., et al., The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data, 2016. 3: p. 160018. [CrossRef]

- Doniparthi, G., T. Mühlhaus, and S. Deßloch, Integrating FAIR Experimental Metadata for Multi-omics Data Analysis. Datenbank-Spektrum, 2024. 24(2): p. 107-115. [CrossRef]

- Jan, M., et al., A multi-omics digital research object for the genetics of sleep regulation. Scientific Data, 2019. 6(1): p. 258. [CrossRef]

- Khatri, P., M. Sirota, and A.J. Butte, Ten years of pathway analysis: current approaches and outstanding challenges. PLoS Comput Biol, 2012. 8(2): p. e1002375. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-M., et al., Identifying significantly impacted pathways: a comprehensive review and assessment. Genome Biology, 2019. 20(1): p. 203. [CrossRef]

- Nam, D. and S.Y. Kim, Gene-set approach for expression pattern analysis. Brief Bioinform, 2008. 9(3): p. 189-97. [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, Z., et al., A comprehensive survey of the approaches for pathway analysis using multi-omics data integration. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 2022. 23(6). [CrossRef]

- García-Campos, M.A., J. Espinal-Enríquez, and E. Hernández-Lemus, Pathway Analysis: State of the Art. Frontiers in Physiology, 2015. 6. [CrossRef]

- Winston, J.E., Twenty-First Century Biological Nomenclature—The Enduring Power of Names. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 2018. 58(6): p. 1122-1131. [CrossRef]

- Vassalli, P., The pathophysiology of tumor necrosis factors. Annu Rev Immunol, 1992. 10: p. 411-52. [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.D. and D. Vucic, The Balance of TNF Mediated Pathways Regulates Inflammatory Cell Death Signaling in Healthy and Diseased Tissues. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020. 8: p. 365. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., et al., Designing Theory-Driven User-Centric Explainable AI, in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2019, Association for Computing Machinery: Glasgow, Scotland Uk. p. Paper 601.

- Jara, J.H., et al., Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates NMDA receptor activity in mouse cortical neurons resulting in ERK-dependent death. J Neurochem, 2007. 100(5): p. 1407-20. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian-Leon, P., et al., Understanding disease mechanisms with models of signaling pathway activities. BMC Systems Biology, 2014. 8(1): p. 121. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., et al., Prioritizing biological pathways by recognizing context in time-series gene expression data. BMC Bioinformatics, 2016. 17(17): p. 477. [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, J. and J. Bergh, How apoptosis is regulated, and what goes wrong in cancer. BMJ, 2001. 322(7301): p. 1538-1539. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.M., G. Gillet, and N. Popgeorgiev, Caspases in the Developing Central Nervous System: Apoptosis and Beyond. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2021. 9. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.R., et al., Control of adult neurogenesis by programmed cell death in the mammalian brain. Molecular Brain, 2016. 9(1): p. 43. [CrossRef]

- Anosike, N.L., et al., Necroptosis in the developing brain: role in neurodevelopmental disorders. Metabolic Brain Disease, 2023. 38(3): p. 831-837. [CrossRef]

- Saini, S., P. Kakati, and K. Singh, Role of Inflammation in Tissue Regeneration and Repair, in Inflammation Resolution and Chronic Diseases, A. Tripathi, et al., Editors. 2024, Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore. p. 103-127.

- Choi, B., C. Lee, and J.-W. Yu, Distinctive role of inflammation in tissue repair and regeneration. Archives of Pharmacal Research, 2023. 46(2): p. 78-89. [CrossRef]

- Wyss-Coray, T. and L. Mucke, Inflammation in neurodegenerative disease--a double-edged sword. Neuron, 2002. 35(3): p. 419-32. [CrossRef]

- Gasque, P., et al., Roles of the complement system in human neurodegenerative disorders: pro-inflammatory and tissue remodeling activities. Mol Neurobiol, 2002. 25(1): p. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Shih, R.-H., C.-Y. Wang, and C.-M. Yang, NF-kappaB Signaling Pathways in Neurological Inflammation: A Mini Review. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 2015. 8. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-C., The non-canonical NF-κB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2017. 17(9): p. 545-558. [CrossRef]

- Adriaens, M.E., et al., The public road to high-quality curated biological pathways. Drug Discovery Today, 2008. 13(19): p. 856-862. [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.-G. and A.R. Pico, Using published pathway figures in enrichment analysis and machine learning. BMC Genomics, 2023. 24(1): p. 713. [CrossRef]

- Vivar, J.C., et al., Redundancy control in pathway databases (ReCiPa): an application for improving gene-set enrichment analysis in Omics studies and "Big data" biology. Omics, 2013. 17(8): p. 414-22. [CrossRef]

- Pastrello, C., Y. Niu, and I. Jurisica, Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Microarray Data. Methods Mol Biol, 2022. 2401: p. 147-159.

- Gable, A.L., et al., Systematic assessment of pathway databases, based on a diverse collection of user-submitted experiments. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 2022. 23(5). [CrossRef]

- Maertens, A., et al., Functionally Enigmatic Genes in Cancer: Using TCGA Data to Map the Limitations of Annotations. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 4106. [CrossRef]

- Stoney, R.A., et al., Using set theory to reduce redundancy in pathway sets. BMC Bioinformatics, 2018. 19(1): p. 386. [CrossRef]

- Krassowski, M., et al., State of the Field in Multi-Omics Research: From Computational Needs to Data Mining and Sharing. Front Genet, 2020. 11: p. 610798. [CrossRef]

- Hanspers, K., et al., Ten simple rules for creating reusable pathway models for computational analysis and visualization. PLOS Computational Biology, 2021. 17(8): p. e1009226. [CrossRef]

- He, C., et al., Interactive visual facets to support fluid exploratory search. Journal of Visualization, 2023. 26(1): p. 211-230. [CrossRef]

- Reimand, J., et al., Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g:Profiler, GSEA, Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap. Nature Protocols, 2019. 14(2): p. 482-517. [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikova, S. and S. Anders, Exploring dimension-reduced embeddings with Sleepwalk. Genome Res, 2020. 30(5): p. 749-756. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al., Exaggerated false positives by popular differential expression methods when analyzing human population samples. Genome Biology, 2022. 23(1): p. 79. [CrossRef]

- Radulescu, E., et al., Identification and prioritization of gene sets associated with schizophrenia risk by co-expression network analysis in human brain. Mol Psychiatry, 2020. 25(4): p. 791-804. [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, J., et al., Importance of the dysregulation of the kynurenine pathway on cognition in schizophrenia: a systematic review of clinical studies. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2023. 273(6): p. 1317-1328. [CrossRef]

- Rusina, P.V., et al., Genetic support for FDA-approved drugs over the past decade. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2023. 22(11): p. 864. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, D., et al., Human genetics evidence supports two-thirds of the 2021 FDA-approved drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2022. 21(8): p. 551. [CrossRef]

- Diogo, D., et al., TYK2 protein-coding variants protect against rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity, with no evidence of major pleiotropic effects on non-autoimmune complex traits. PLoS One, 2015. 10(4): p. e0122271. [CrossRef]

- MacNamara, A., et al., Network and pathway expansion of genetic disease associations identifies successful drug targets. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 20970. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente van Bentem, S., et al., Towards functional phosphoproteomics by mapping differential phosphorylation events in signaling networks. PROTEOMICS, 2008. 8(21): p. 4453-4465. [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, E.A., et al., Workability of mRNA Sequencing for Predicting Protein Abundance. Genes, 2023. 14(11): p. 2065. [CrossRef]

- Prabahar, A., et al., Unraveling the complex relationship between mRNA and protein abundances: a machine learning-based approach for imputing protein levels from RNA-seq data. NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics, 2024. 6(1). [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Abreu, R., et al., Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Molecular BioSystems, 2009. 5(12): p. 1512-1526. [CrossRef]

- Upadhya, S.R. and C.J. Ryan, Experimental reproducibility limits the correlation between mRNA and protein abundances in tumor proteomic profiles. Cell Rep Methods, 2022. 2(9): p. 100288. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, O.A., et al., An Integrative Analysis of Tumor Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Profiles to Examine the Relationships Between Kinase Activity and Phosphorylation*. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 2019. 18(8, Supplement 1): p. S26-S36. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., A. Beyer, and R. Aebersold, On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell, 2016. 165(3): p. 535-550. [CrossRef]

- Handly, L.N., J. Yao, and R. Wollman, Signal Transduction at the Single-Cell Level: Approaches to Study the Dynamic Nature of Signaling Networks. J Mol Biol, 2016. 428(19): p. 3669-82. [CrossRef]

- Creeden, J.F., et al., Kinome Array Profiling of Patient-Derived Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Identifies Differentially Active Protein Tyrosine Kinases. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(22). [CrossRef]

- Litichevskiy, L., et al., A Library of Phosphoproteomic and Chromatin Signatures for Characterizing Cellular Responses to Drug Perturbations. Cell Syst, 2018. 6(4): p. 424-443.e7. [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, M., et al., Kinobeads: A Chemical Proteomic Approach for Kinase Inhibitor Selectivity Profiling and Target Discovery, in Target Discovery and Validation. 2019. p. 97-130.

- Patricelli, M.P., et al., In situ kinase profiling reveals functionally relevant properties of native kinases. Chem Biol, 2011. 18(6): p. 699-710. [CrossRef]

- Alganem, K., et al., The active kinome: The modern view of how active protein kinase networks fit in biological research. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2022. 62: p. 117-129. [CrossRef]

- Cowen, L., et al., Network propagation: a universal amplifier of genetic associations. Nat Rev Genet, 2017. 18(9): p. 551-562. [CrossRef]

- Supek, F. and N. Skunca, Visualizing GO Annotations. Methods Mol Biol, 2017. 1446: p. 207-220.

- Gan, M., X. Dou, and R. Jiang, From ontology to semantic similarity: calculation of ontology-based semantic similarity. ScientificWorldJournal, 2013. 2013: p. 793091. [CrossRef]

- Supek, F., et al., REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One, 2011. 6(7): p. e21800. [CrossRef]

- Pesquita, C., et al., Semantic similarity in biomedical ontologies. PLoS Comput Biol, 2009. 5(7): p. e1000443. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. and Z. Wang, GOGO: An improved algorithm to measure the semantic similarity between gene ontology terms. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 15107. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G., et al., clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS, 2012. 16(5): p. 284-7. [CrossRef]

- Galeota, E., K. Kishore, and M. Pelizzola, Ontology-driven integrative analysis of omics data through Onassis. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 703. [CrossRef]

- Duong, D., et al., Word and Sentence Embedding Tools to Measure Semantic Similarity of Gene Ontology Terms by Their Definitions. J Comput Biol, 2019. 26(1): p. 38-52. [CrossRef]

- Blimkie, T.M., A. An, and R.E.W. Hancock, Facilitating pathway and network based analysis of RNA-Seq data with pathlinkR. PLOS Computational Biology, 2024. 20(9): p. e1012422. [CrossRef]

- Prummer, M., Enhancing gene set enrichment using networks. F1000Res, 2019. 8: p. 129. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S., et al., GScluster: network-weighted gene-set clustering analysis. BMC Genomics, 2019. 20(1): p. 352. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A., et al., GeneFEAST: the pivotal, gene-centric step in functional enrichment analysis interpretation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.00061, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kerseviciute, I. and J. Gordevicius, aPEAR: an R package for autonomous visualization of pathway enrichment networks. Bioinformatics, 2023. 39(11). [CrossRef]

- Bhuva, D.D., et al., vissE: a versatile tool to identify and visualise higher-order molecular phenotypes from functional enrichment analysis. BMC Bioinformatics, 2024. 25(1): p. 64. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A., et al., vissE.cloud: a webserver to visualise higher order molecular phenotypes from enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res, 2023. 51(W1): p. W593-W600. [CrossRef]

- Major, V., A. Surkis, and Y. Aphinyanaphongs, Utility of General and Specific Word Embeddings for Classifying Translational Stages of Research. AMIA Annu Symp Proc, 2018. 2018: p. 1405-1414.

- Chiu, B., et al. How to train good word embeddings for biomedical NLP. in Proceedings of the 15th workshop on biomedical natural language processing. 2016.

- Mikolov, T., et al., Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ofer, D., N. Brandes, and M. Linial, The language of proteins: NLP, machine learning & protein sequences. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 2021. 19: p. 1750-1758. [CrossRef]

- Xenos, A., et al., Linear functional organization of the omic embedding space. Bioinformatics, 2021. 37(21): p. 3839-3847. [CrossRef]

- Asgari, E. and M.R. Mofrad, Continuous Distributed Representation of Biological Sequences for Deep Proteomics and Genomics. PLoS One, 2015. 10(11): p. e0141287. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, V.W., et al., Interpreting and visualizing pathway analyses using embedding representations with PAVER. Bioinformation, 2024. 20(7): p. 700-704. [CrossRef]

- Kulmanov, M., et al., Semantic similarity and machine learning with ontologies. Brief Bioinform, 2021. 22(4). [CrossRef]

- Lerman, G. and B.E. Shakhnovich, Defining functional distance using manifold embeddings of gene ontology annotations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007. 104(27): p. 11334-9. [CrossRef]

- Al Abir, F. and J.Y. Chen, Mondrian Abstraction and Language Model Embeddings for Differential Pathway Analysis. bioRxiv, 2024.

- Chen, D.-Q., et al., Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes and Signaling Pathways in Acute Myocardial Infarction Based on Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis. Cardiovascular Therapeutics, 2019. 2019(1): p. 8490707. [CrossRef]

- Jia, R., et al., Identification of key genes unique to the luminal a and basal-like breast cancer subtypes via bioinformatic analysis. World Journal of Surgical Oncology, 2020. 18(1): p. 268. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y., et al., Bioinformatics to analyze the differentially expressed genes in different degrees of Alzheimer’s disease and their roles in progress of the disease. Journal of Applied Genetics, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gamazon, E.R., et al., Multi-tissue transcriptome analyses identify genetic mechanisms underlying neuropsychiatric traits. Nature Genetics, 2019. 51(6): p. 933-940. [CrossRef]

- Kulasinghe, A., et al., Transcriptomic profiling of cardiac tissues from SARS-CoV-2 patients identifies DNA damage. Immunology, 2023. 168(3): p. 403-419. [CrossRef]

- Dalit, L., et al., Divergent cytokine and transcriptional signatures control functional T follicular helper cell heterogeneity. bioRxiv, 2024: p. 2024.06.12.598622. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y., et al., Inhibition of HTR2B-mediated serotonin signaling in colorectal cancer suppresses tumor growth through ERK signaling. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2024. 179: p. 117428. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.H., et al., Developmental pyrethroid exposure disrupts molecular pathways for MAP kinase and circadian rhythms in mouse brain. bioRxiv, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, M.A., et al., Developmental pyrethroid exposure in mouse leads to disrupted brain metabolism in adulthood. NeuroToxicology, 2024. 103: p. 87-95. [CrossRef]

- O'Donovan, S., et al., Shared and unique transcriptional changes in the orbitofrontal cortex in psychiatric disorders and suicide. Translation: The University of Toledo Journal of Medical Sciences, 2024. 12. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., et al., Probiotic Protects Kidneys Exposed to Microcystin-LR. Translation: The University of Toledo Journal of Medical Sciences, 2024. 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Hodgman, C., A. French, and D. Westhead, BIOS Instant Notes in Bioinformatics. 2009: Taylor & Francis.

- Karp, P.D., et al., Pathway size matters: the influence of pathway granularity on over-representation (enrichment analysis) statistics. BMC Genomics, 2021. 22(1): p. 191. [CrossRef]

- Wijesooriya, K., et al., Urgent need for consistent standards in functional enrichment analysis. PLoS Comput Biol, 2022. 18(3): p. e1009935. [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, M., B. Schroeter, and A. Bora, Two subtle problems with over-representation analysis. Bioinformatics Advances, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hale, M.L., I. Thapa, and D. Ghersi, FunSet: an open-source software and web server for performing and displaying Gene Ontology enrichment analysis. BMC Bioinformatics, 2019. 20(1): p. 359. [CrossRef]

- Ewing, E., et al., GeneSetCluster: a tool for summarizing and integrating gene-set analysis results. BMC Bioinformatics, 2020. 21(1): p. 443. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., D.H. Oh, and M. Dassanayake, GOMCL: a toolkit to cluster, evaluate, and extract non-redundant associations of Gene Ontology-based functions. BMC Bioinformatics, 2020. 21(1): p. 139. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G., Gene Ontology Semantic Similarity Analysis Using GOSemSim. Methods Mol Biol, 2020. 2117: p. 207-215.

- Gu, Z. and D. Hübschmann, SimplifyEnrichment: A Bioconductor Package for Clustering and Visualizing Functional Enrichment Results. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 2022. 21(1): p. 190-202. [CrossRef]

- Kolde, R. and J. Vilo, GOsummaries: an R Package for Visual Functional Annotation of Experimental Data. F1000Res, 2015. 4: p. 574. [CrossRef]

- Balestra, C., et al., Redundancy-aware unsupervised ranking based on game theory: Ranking pathways in collections of gene sets. PLoS One, 2023. 18(3): p. e0282699. [CrossRef]

- Weistuch, C., et al., Normal tissue transcriptional signatures for tumor-type-agnostic phenotype prediction. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 27230. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).