Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

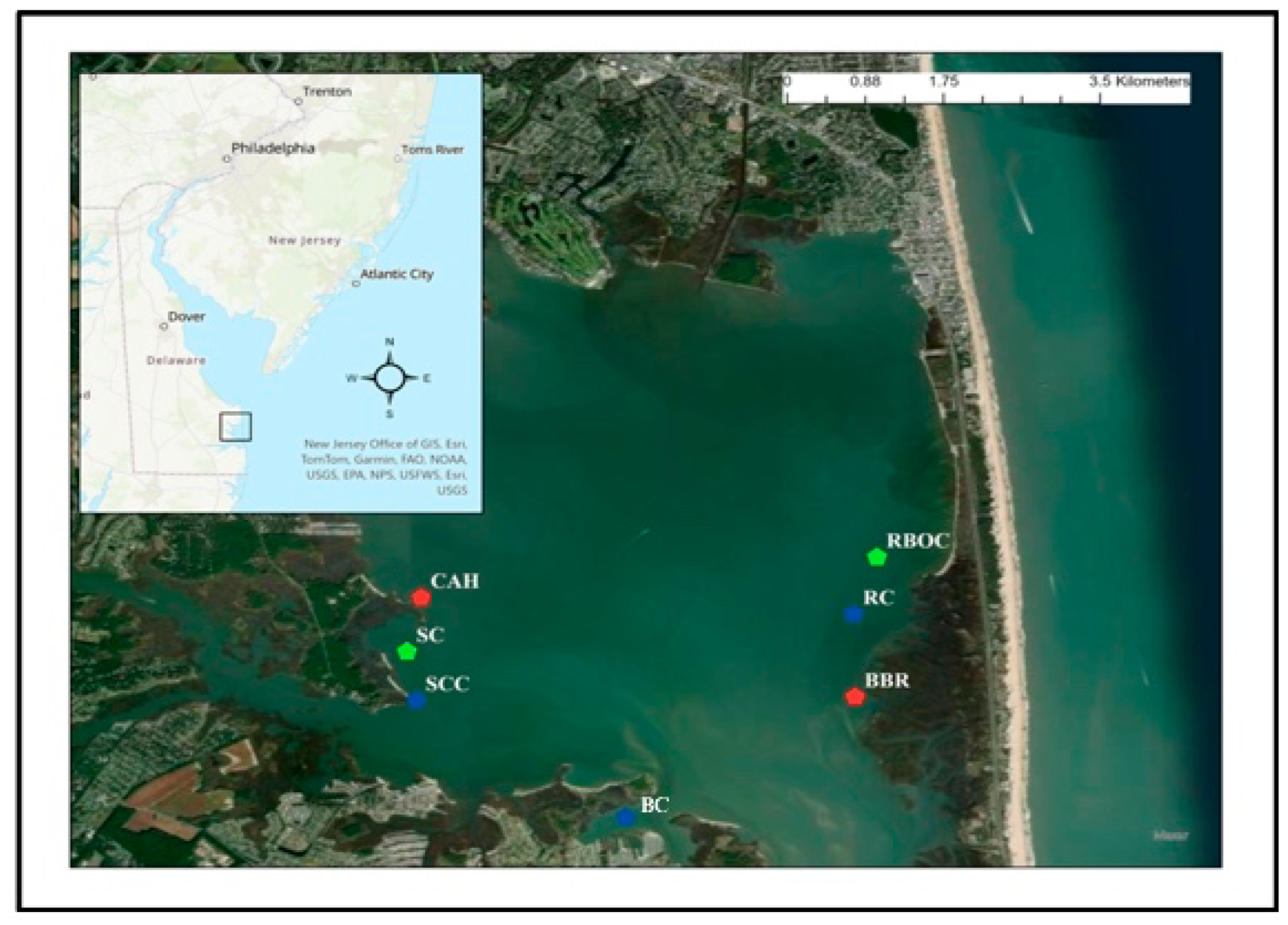

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Water Quality Monitoring

2.3. Calculation of Aragonite Saturation State

3. Results

3.1. Physiochemical Water Quality Monitoring

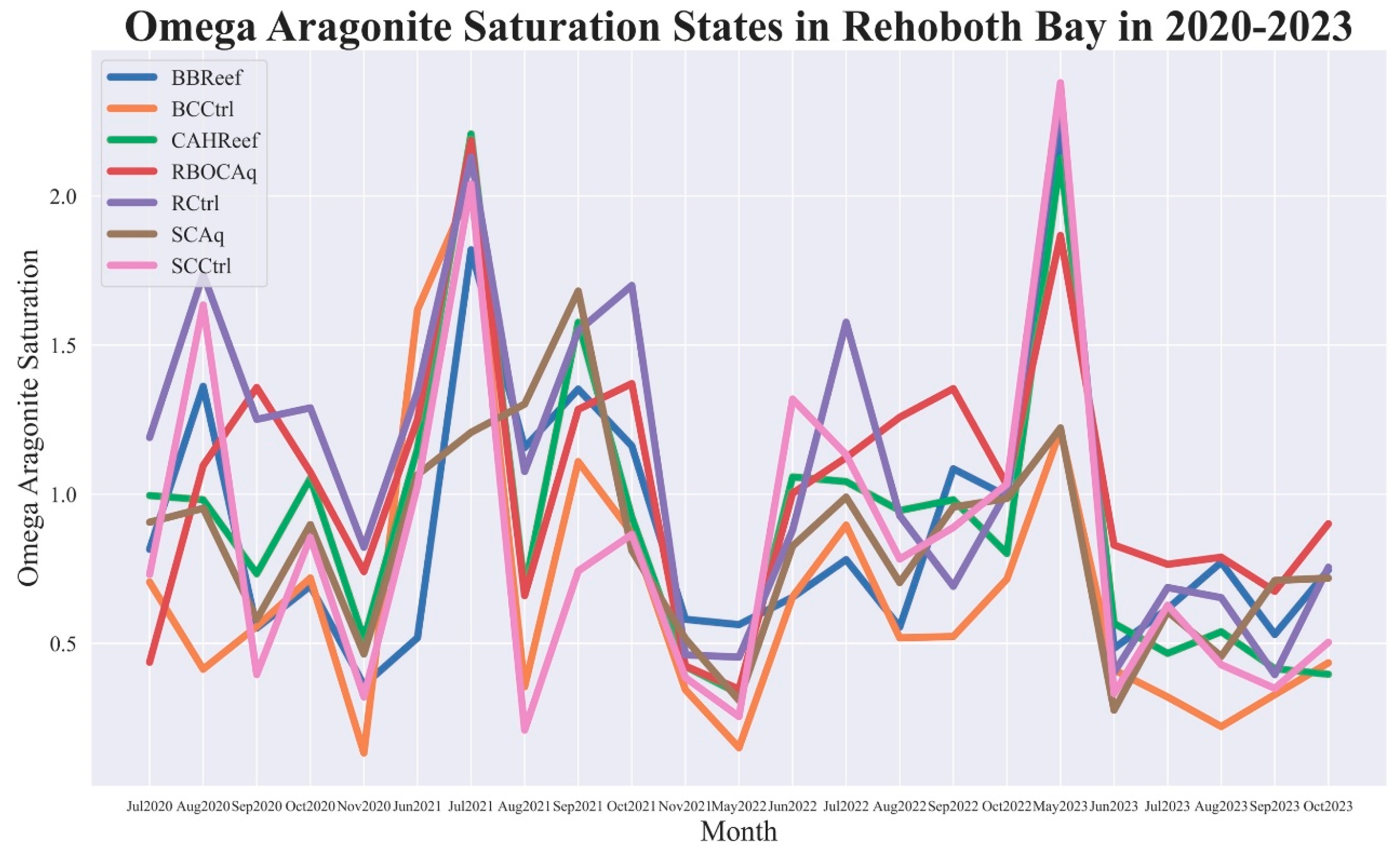

3.2. Calculated Aragonite-Calcite Saturation States

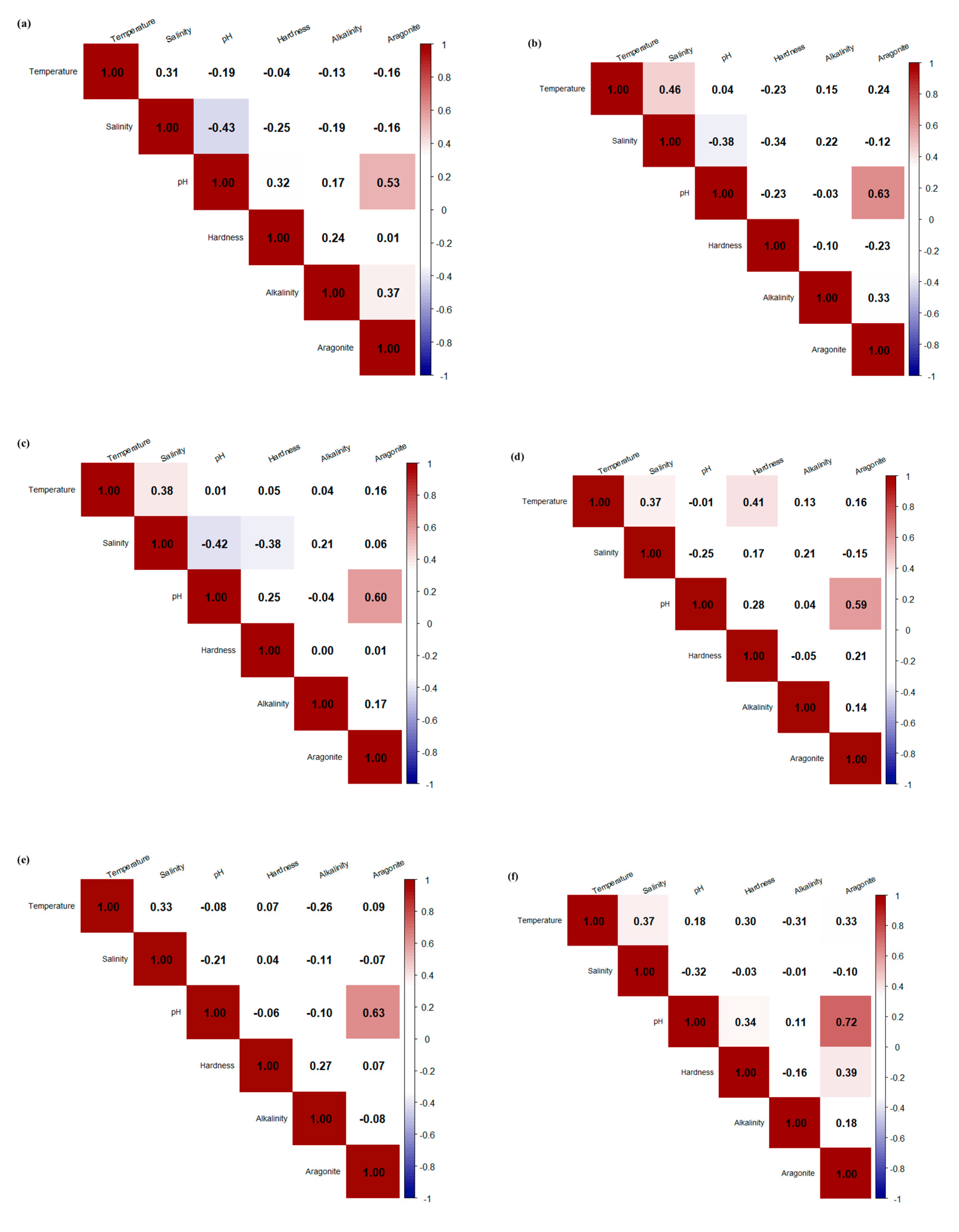

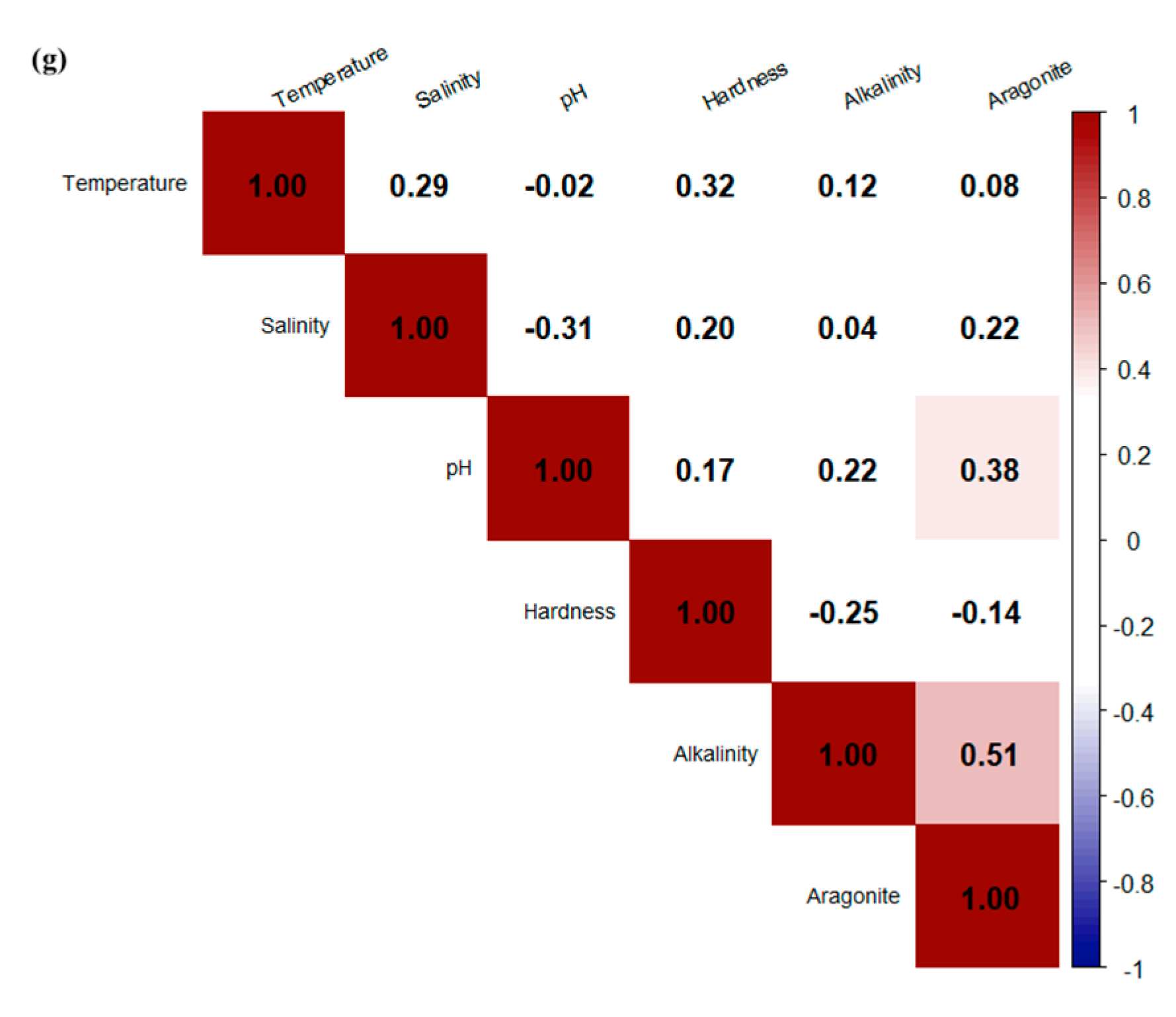

3.3. Correlations Between Water Quality and Saturation States

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waldbusser, G.G., Voigt, E.P., Bergschneider, H. et al. Biocalcification in the Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) in Relation to Long-term Trends in Chesapeake Bay pH. Estuaries and Coasts 34, 221–231 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Walch, M.A. McGowan, L. Swanger, C. Chaney, and M. Goss. (2023). State of the Delaware Inland Bays, 2021. Delaware Center for the Inland Bays, March 2023, 104 pp. inlandbays.org.

- Babb, R. (2018). Eastern Oysters of the Delaware Bay. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Marine Issue. https://dep.nj.gov/wp-content/uploads/njfw/digest-marine-2018-eastern-oysters-of-the-delaware-bay-russ-babb.pdf.

- Raj, Sanjeeva P.J. (2008). Oysters in a new classification of keystone species. Reson 13, 648–654. [CrossRef]

- Coen, L. D., Brumbaugh, R. D., Bushek, D., Grizzle, R., Luckenbach, M. W., Posey, M. H., Powers, S. P., & Tolley, S. G. (2007). Ecosystem Services related to oyster restoration. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 341, 303–307. [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, J.H., Brumbaugh, R.D., Conrad, R.F., Keeler, A.G., Opaluch, J.J., Peterson, C.H., Piehler, M.F., Powers, S.P., Smyth, A.R. (2012). Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services Provided by Oyster Reefs, BioScience, Volume 62, Issue 10, Pages 900–909. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, C. A., & Bason, C. W. (2020). The Economic Value of the Delaware Inland Bays. DE Center for the Inland Bays. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://www.inlandbays.org/about-the-bays/economic-value-of-the-inland-bays/.

- Ewart, W. J. (2013). Shellfish Aquaculture in Delaware’s Inland Bays: Status Opportunities, and Constraints. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/38095.

- Callier MD, Byron CJ, Bengtson DA, Cranford PJ, and others. (2018). Attraction and repulsion of mobile wild organisms to finfish and shellfish aquaculture: a review. Rev Aquacult 10:924−949.

- Marshall, D.A., Coxe, N.C., La Peyre, M.K., Walton, W.C., Rikard, S.F., Pollack, J.B., Kelly, M.W., La Peyre, J.F. (2021). Tolerance of northern Gulf of Mexico eastern oysters to chronic warming at extreme salinities. Journal of Thermal Biology, vol.100, 2021, 0306-4565. [CrossRef]

- Hijuelos, A. C., Sable, S. E., O’Connell, A. M., and Geaghan, J. P. (2017). 2017 Coastal Master Plan: Attachment C3-12: Eastern Oyster, Crassostrea virginica, Habitat Suitability Index Model. Version Final. (pp. 1-23). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

- Barnes, T. & Volety, Aswani & Chartier, K & Mazzotti, F. & Pearlstine, Leonard. (2007). A habitat suitability index model for the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), a tool for restoration of the Caloosahatchee Estuary, Florida. Journal of Shellfish Research - J SHELLFISH RES. 26. 10.2983/0730-8000(2007)26[949:AHSIMF]2.0.CO;2.

- EOBRT (Eastern Oyster Biological Review Team). 2007. Status review of the Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), p. 7. Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service, Northeast Regional Office. Memo.NMFS F/SPO-88.

- Patterson HK, Boettcher A, Carmichael RH. Biomarkers of dissolved oxygen stress in oysters: a tool for restoration and management efforts. PLoS One. 2014 Aug 12;9(8):e104440. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaines, E., Sturmer, L., Anderson, N., Laramore, S., and Baker, S. (n.d.). The Role of pH, Alkalinity, and Calcium Carbonate in Shellfish Hatcheries. University of Florida. https://shellfish.ifas.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/pH-and-Alkalinity-Fact-Sheet-for-Hatcheries-Final-Draft.pdf.

- Turley, C.M., Roberts, J.M. & Guinotte, J.M. (2007). Corals in deep water: will the unseen hand of ocean acidification destroy cold-water ecosystems? Coral Reefs 26, 445–448. [CrossRef]

- Newton, Jan & Klinger, Terrie. (2015). Ocean Acidification in Pacific Northwest Coastal Waters: What Do We Know? College of the Environment.

- Miller, A. W., Reynolds, A. C., Sobrino, C., & Riedel, G. F. (2009). Shellfish face uncertain future in high CO2 World: Influence of acidification on oyster larvae calcification and growth in estuaries. PLoS ONE, 4(5). [CrossRef]

- Shen, C., Testa, J. M., Li, M., & Cai, W.-J. (2020). Understanding anthropogenic impacts on pH and aragonite saturation state in Chesapeake Bay: Insights from a 30-year model study. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 125, e2019JG005620. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L. J. R. (2023). The Rising Threat of Atmospheric CO2: A Review on the Causes, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies. Environments, 10(4), 66. [CrossRef]

- Freely, R.A., S.C. Doney, and S.R. Cooley. 2009. Ocean acidification: Present conditions and future changes in a high-CO2 world. Oceanography 22(4):36–47, . [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.-Q., R. A. Feely, B. R. Carter, D. J. Greeley, D. K. Gledhill, and K. M. Arzayus (2015), Climatological distribution of aragonite saturation state in the global oceans, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 29, 1656–1673, doi:10.1002/2015GB005198.

- Talmage S.C. , & Gobler C.J. (2010). Effects of past, present, and future ocean carbon dioxide concentrations on the growth and survival of larval shellfish, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (40) 17246-17251, . [CrossRef]

- Xue, L., Yang, X., Li, Y., Li, L., Jiang, L.-Q., Xin, M., et al. (2020). Processes controlling sea surface pH and aragonite saturation state in a large northern temperate bay: Contrasting temperature effects. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 125, e2020JG005805. [CrossRef]

- Lemasson, A.J., Fletcher, S., Hall-Spencer, J.M., Knights, A.M. (2017). Linking the biological impacts of ocean acidification on oysters to changes in ecosystem services: A review. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, vol.492, pp. 49-62, 2017, 0022-0981. [CrossRef]

- NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association). (2023). Eastern Oyster. NOAA Fisheries.https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/eastern-oyster#oyster-management-and-restoration.

- Xu, X., Hu, Y., He, Z., Wang, X., Chen, H., and Han, J. (2023). Processes controlling the aragonite saturation state in the North Yellow Sea near the Yalu River estuary: contrasting river input effects. Frontiers in Marine Science, vol. 10: 2296-7745. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marinescience/articles/10.3389/fmars.2023.1158896.

- Liberti, C.M., Gray, M.W., Mayer, L.M., Testa, J.M., Liu, W., Brady, D.C. (2022). The impact of oyster aquaculture on the estuarine carbonate system. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene; 10 (1): 00057. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).