1. Introduction

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions are under intense pressure to adapt their educational methods due to Industry 4.0 advancements. This industrial revolution, marked by automation, connectivity, machine learning, and real-time data analysis, has significantly changed workforce demands across various sectors (UNESCO, 2023). Although TVET has traditionally focused on practical skills, the current labor markets require graduates to possess superior digital skills and adaptability to technology (ILO, 2024). Integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into TVET programs has become a key focus to bridge this skills gap, creating valuable opportunities to improve practice-based learning while equipping students for AI-driven careers (McKinsey, 2023). The incorporation of AI technologies into Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is a powerful catalyst, transforming skills development, student engagement with educational resources, and enhancing employability.

AI-enabled educational tools—ranging from sensor-equipped simulators that deliver instant feedback on hands-on activities to adaptable learning systems and generative AI helpers—provide unmatched opportunities for customization, prompt support, and interaction in vocational skill training (World Economic Forum, 2024). These tools mark a notable improvement over conventional training methods, especially for technical skills that demand considerable practice, accuracy, and flexibility across different scenarios.

1.1. Background

The digital transformation of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) has gained global traction via policy initiatives and reforms within institutions. Reports from UNESCO and ILO highlight the "successful implementation of various forms of digital technology" in TVET institutions worldwide, with significant adoption even in settings with limited resources (UNESCO-UNEVOC, 2023). Nonetheless, there are still significant hurdles regarding technological infrastructure, faculty readiness, and curriculum integration. In the context of this broader digital transformation, AI holds a unique role, serving both as an instructional resource that enriches learning experiences and as an essential vocational skill that students must acquire for their future careers (OECD, 2024).

Even with increasing investment and interest in AI applications for TVET, the research field remains fragmented and less developed than AI studies in higher education and corporate training contexts (Holmes et al., 2022; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2023). Existing literature consists of disconnected technological pilot projects, perception studies, and theoretical frameworks, but it lacks a thorough synthesis of empirical results across vocational areas. This knowledge gap hinders evidence-based policymaking and strategic implementation at a time when TVET systems are under increasing pressure to incorporate AI-related competencies.

Although AI research in education has progressed significantly by creating theoretical frameworks (Luckin et al., 2022) and adoption models (TPACK, UTAUT), these methods need substantial modification to cater to the distinct aspects of vocational education effectively. This includes emphasizing practical skills, alignment with industry needs, and diverse learning settings encompassing classrooms, workshops, and simulated workplaces. The specific nature of vocational education presents unique challenges for AI deployment that are not thoroughly examined in the wider literature on educational technology (Suarta et al., 2023).

1.2. Research Aim and Questions

This systematic review identifies significant gaps in our knowledge about AI in TVET by consolidating empirical evidence from various contexts, technologies, and methods. It transcends theoretical discussions to explore actual implementations and quantifiable outcomes, thereby establishing a foundation for institutional decision-making and guiding future research. Our analysis specifically tackles four interconnected questions:

What types of AI technologies and pedagogical applications have been implemented in TVET settings, and what empirical outcomes (e.g., skill gains, engagement, employability indicators) have been reported?

How do findings compare across countries, vocational domains, and outcome measures (quantitative skill assessments versus perceptions)?

What barriers, teacher or student perceptions, and contextual factors influence the success of AI in TVET programs?

What gaps exist in the evidence, and what research directions are recommended for advancing AI in vocational training?

This review systematically explores these questions, offering the first comprehensive overview of the empirical landscape of AI in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET). It identifies promising applications, effective implementation strategies, methodological limitations, and research priorities. This contribution is especially relevant as TVET institutions globally confront technological transformations amid resource constraints and swiftly changing industry demands.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A structured literature search was conducted in 2025. We utilized conventional academic databases (IEEE Xplore, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis, ERIC, Google Scholar) and relevant grey literature sources (UNESCO-UNEVOC reports, conference proceedings, industry white papers). Search queries combined terms such as "artificial intelligence," "machine learning," and "robotics" with "vocational education," "technical training," "skills," and domain-specific keywords (e.g., "welding," "simulator," "ChatGPT," "LMS"). We included studies published in English from 2018 onward to capture recent developments.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We searched for sources that provided empirical evidence regarding AI in legitimate TVET settings. This included studies on AI-driven tools or curricula within vocational schools, training institutes, apprenticeships, or technical colleges, focusing on outcomes like skill performance, learning efficiency, or career preparedness. The study designs varied from controlled experiments to mixed-method evaluations. We excluded research outside of TVET, such as general K-12 education, purely theoretical AI papers without practical application, and studies that did not assess learning or employability outcomes, such as technology descriptions without evaluations or surveys assessing attitudes only. Additionally, we omitted "AI" interventions that were merely static, rule-based e-learning systems, devoid of adaptive algorithms or data-driven features.

2.3. Screening and Selection

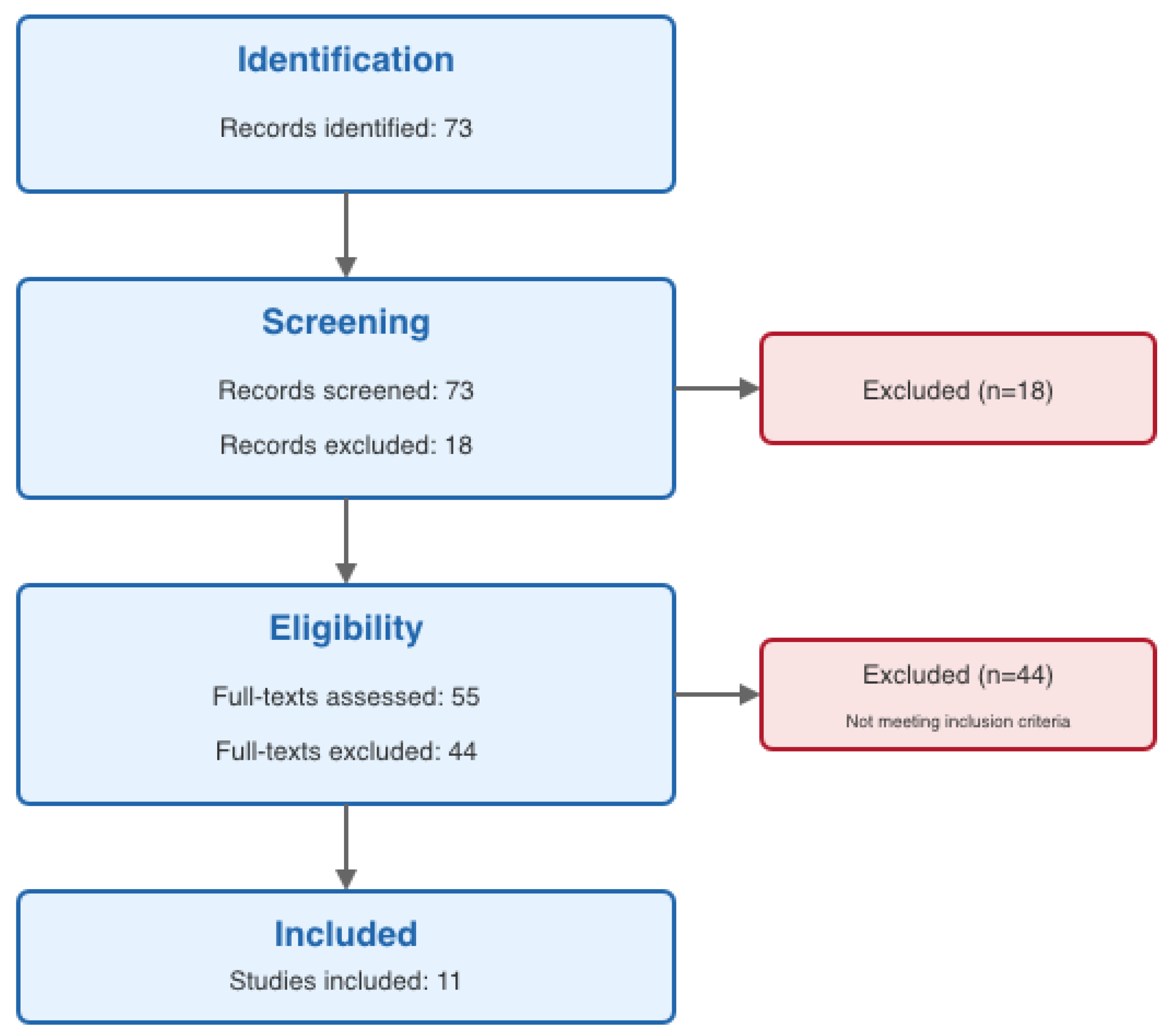

The initial search yielded over a hundred records. After removing duplicates, we screened titles and abstracts for relevance. The authors evaluated each citation against the set criteria independently. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. We then assessed the full texts of potentially relevant studies to verify eligibility: the studies needed to explicitly involve AI or machine learning and report at least one quantitative or mixed-method outcome within a vocational training context. In the end, 11 primary references (2021-2025) satisfied all criteria.

Figure 1 shows our PRISMA-compliant screening and selection process.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

We extracted bibliographic information from each study and coded various aspects, including country/context, vocational domain (such as welding, robotics, automotive), AI technology type (like XR simulator, adaptive learning system, generative AI tool), research design, sample, and reported outcomes (skill measures, survey scales, etc.). The studies were thematically grouped for synthesis into categories, including controlled skill assessments, perception/engagement surveys, curriculum employability analyses, and implementation case studies. These categories were developed iteratively from the literature. Although our search wasn't formally registered as a systematic review, the approach aligns with best practices for systematic literature reviews.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

The eleven studies encompassed diverse geographic contexts, methodological approaches, and vocational fields. Geographically, research clusters were found in Malaysia (5 studies), Germany (2 studies), Indonesia (1 study), and China (3 studies).

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of all included studies.

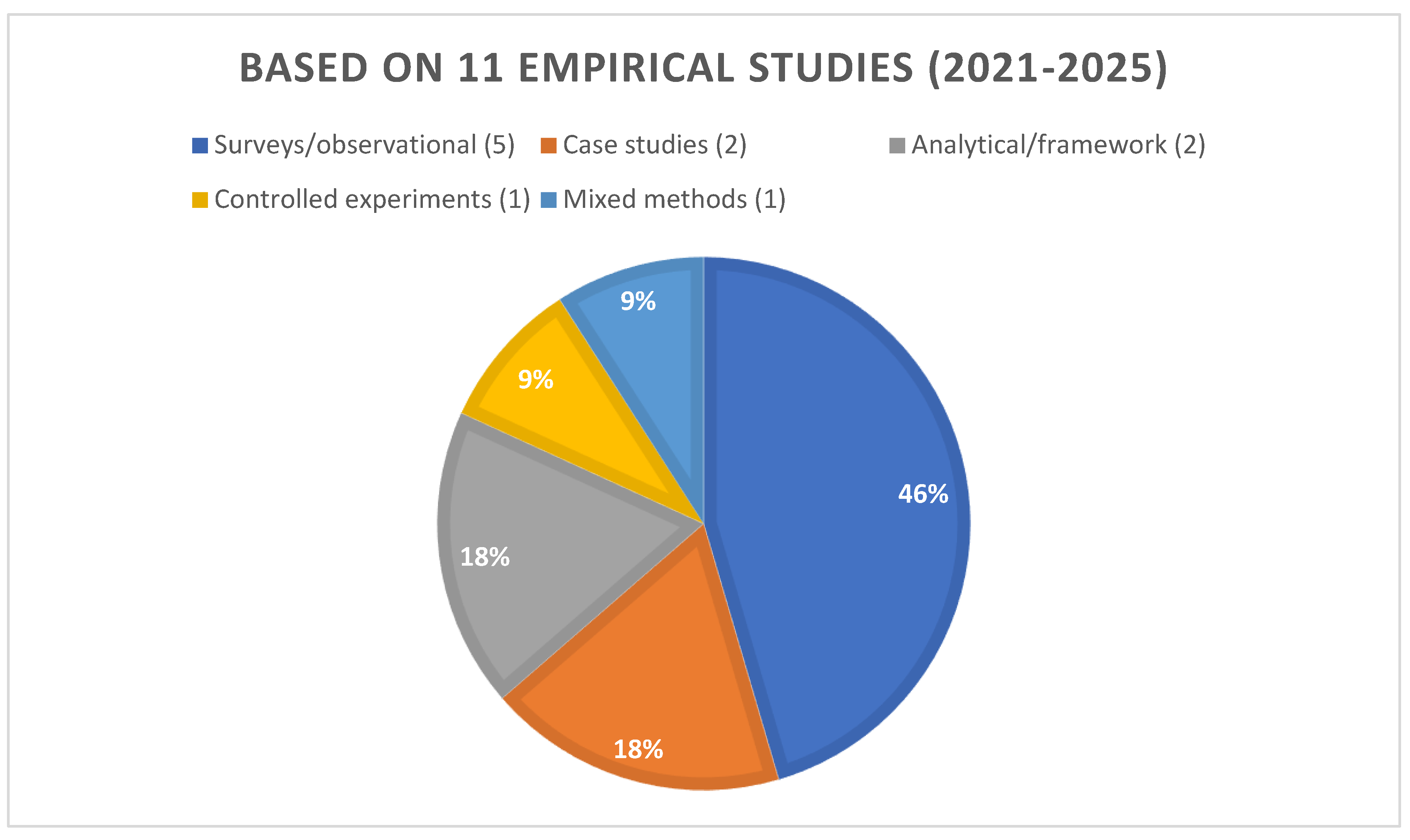

Various methodologies were utilized in the studies, categorized as follows: controlled experiments (1), surveys/observational studies (5), mixed-methods (1), case studies (2), and analytical/decision framework studies (2). This distribution is depicted in

Figure 2.

3.2. AI Technologies and Empirical Outcomes in TVET

Our initial research question focused on the various AI technologies used in TVET environments and their measurable results. We found five primary categories of AI applications within the studies we reviewed.

The strongest empirical evidence arises from research on AI-augmented simulators and Extended Reality (XR) systems equipped with sensor-rich elements that deliver real-time feedback on practical abilities. Lee et al. (2021) examined a multisensor AI-assisted welding trainer that integrated HD cameras, RGB-D sensors, and machine learning to evaluate welding techniques. In a controlled trial, trainees using this system demonstrated notably improved welding accuracy and accelerated learning curves compared to those receiving traditional instruction or participating in non-AI VR training. This research is particularly notable for its rigorous design and quantitative methodology in skill assessment.

AI Teaching Factories and Production Environments represent a notable application domain. Wahjusaputri et al. (2024) explored an AI-driven "teaching factory" within Indonesian vocational schools, where students developed trade skills through a simulated production line with AI assistance. This mixed-methods research revealed significant gains in students' technical skills and efficiency, as well as an increased perception of their readiness for the industry. The teaching factory model illustrates the potential of integrating AI into genuine vocational learning settings to improve technical skills and employability outcomes.

Research, including Zhao et al. (2024), explored adaptive learning systems specifically tailored for Chinese vocational education. This system utilized machine learning to customize learning pathways based on the performance data of students. By offering flexible and personalized educational experiences, it significantly enhanced both academic achievement and engagement. However, the results lacked the quantifiable precision seen in the simulator studies.

Two Malaysian studies concentrated on Generative AI Applications. Ab Hamid et al. (2023) conducted a survey of 173 students utilizing ChatGPT as a learning aid, discovering that most participants experienced positive effects on their comprehension of technical concepts and their overall learning engagement. Baharin et al. (2025) employed a UTAUT framework to investigate the factors influencing generative AI adoption among TVET students from various disciplines, pinpointing performance expectancy as a significant motivating factor. Both studies depended on self-reported results rather than objective skill assessments.

Mohd Fahimey et al. (2024) assessed AI-Enhanced Learning Management Systems (LMS) and analyzed the impact of AI features on the delivery of vocational education in Malaysia. Their case study indicated enhancements in user engagement, satisfaction, and administrative efficiency; however, these results were more descriptive than quantitative, highlighting the need for further longitudinal research.

In addition to these five main categories, the application of AI in TVET is constantly evolving with new uses. Learning Analytics is an expanding field where AI tools monitor student progression, highlight areas that need more attention, and forecast potential dropouts, allowing educators to intervene early (Thakur et al., 2024; Çela et al., 2024). Moreover, the role of Generative AI in Instructional Design is rising, as it facilitates the automated creation of educational materials, leading to the swift development of tailored resources that meet various learner needs (Ranuharja et al., 2025; Egloffstein et al., 2024). These new applications further enhance the prospective benefits of AI throughout the TVET ecosystem.

In conclusion, the empirical results of AI in TVET can be categorized into three key areas. Skill development outcomes are particularly highlighted by controlled studies involving simulators and teaching factories, which demonstrate significant improvements in technical skills, precision, and learning efficiency. Additional quantitative evidence from studies not included in our systematic review reinforces these results. For instance, Riski & Nuryanto (2024) revealed that students engaged in AI-based learning for machining achieved a notably higher average post-test score (81.18) compared to those undergoing traditional learning (76.26). Similarly, Ali et al. (2024) showed that learner-paced digital video courseware, when combined with computational thinking strategies, markedly boosted motivation levels among TVET students. Engagement and perceptual outcomes were generally positive in survey-based research, with students expressing enhanced motivation, confidence, and satisfaction, although these were self-reported rather than independently assessed. Employability indicators were mainly examined in analytical studies employing approaches like AHP, which prioritize the integration of AI tools into the curriculum and the establishment of industry partnerships to improve graduate readiness.

3.3. Comparative Analysis Across Contexts

Our second research question explored the comparisons of findings across different countries, vocational domains, and outcome measures.

3.3.1. Geographic Comparisons

Research is concentrated in specific geographic areas, each with unique focuses. With five studies, Malaysia predominantly examines student perceptions, technology adoption, and employability across various sectors. It often utilizes survey-based approaches and analytical frameworks like UTAUT and AHP. Germany, represented by two studies, addresses teacher readiness and professional development, noting a lack of deep AI understanding among TVET educators and the necessity for basic training. Indonesia contributes 1 study that details a comprehensive teaching factory model targeting skill outcomes and system integration. China’s three studies focus on adaptive learning technologies and curriculum reform efforts, highlighting the importance of personalization and student success. The notable absence of research from Africa, Latin America, and much of North America reveals considerable geographic gaps in the literature.

3.3.2. Vocational Domain Comparisons

AI applications and their results differ across various vocational fields. In manufacturing trades such as welding and automotive, evidence indicates significant positive effects of AI-driven simulators on practical technical skills backed by measurable metrics. Conversely, the ICT, robotics, and design sectors showcased studies concentrating on generative AI and conceptual comprehension, primarily evaluated through self-reported understanding. Research in general vocational education surveyed more extensive platforms like LMS and adaptive systems, focusing less on domain-specific skill evaluation. Fields involving physical, hands-on activities experience the most notable advantages from AI integration, especially when utilizing sensor-rich, real-time feedback mechanisms.

The effectiveness of various AI technologies differs across vocational fields.

Table 2 summarizes comparative results among different types of AI technologies, derived from our review and additional evidence.

3.3.3. Outcome Measure Comparisons

The significant methodological differences hinder the comparability of findings across studies. Only two studies (Lee et al., 2021; Wahjusaputri et al., 2024) utilized quantitative skill assessments, which evaluated tangible skill enhancements through controlled comparisons or objective metrics. In contrast, perception measures dominated the literature, with most studies relying on surveys that frequently employed Likert scales to evaluate satisfaction, perceived understanding, or usability (Idris et al., 2025; Ab Hamid et al., 2023; Baharin et al., 2025). Several studies also implemented analytical frameworks such as AHP or qualitative analysis to set priorities instead of measuring direct outcomes (Mohamad et al., 2024). This diverse range of methodologies restricts direct comparisons among studies and emphasizes the necessity for standardized outcome measures in future research.

3.4. Barriers and Contextual Factors

Our third research question explored the barriers, perceptions, and contextual factors that affect the success of AI in TVET programs.

3.4.1. Implementation Barriers

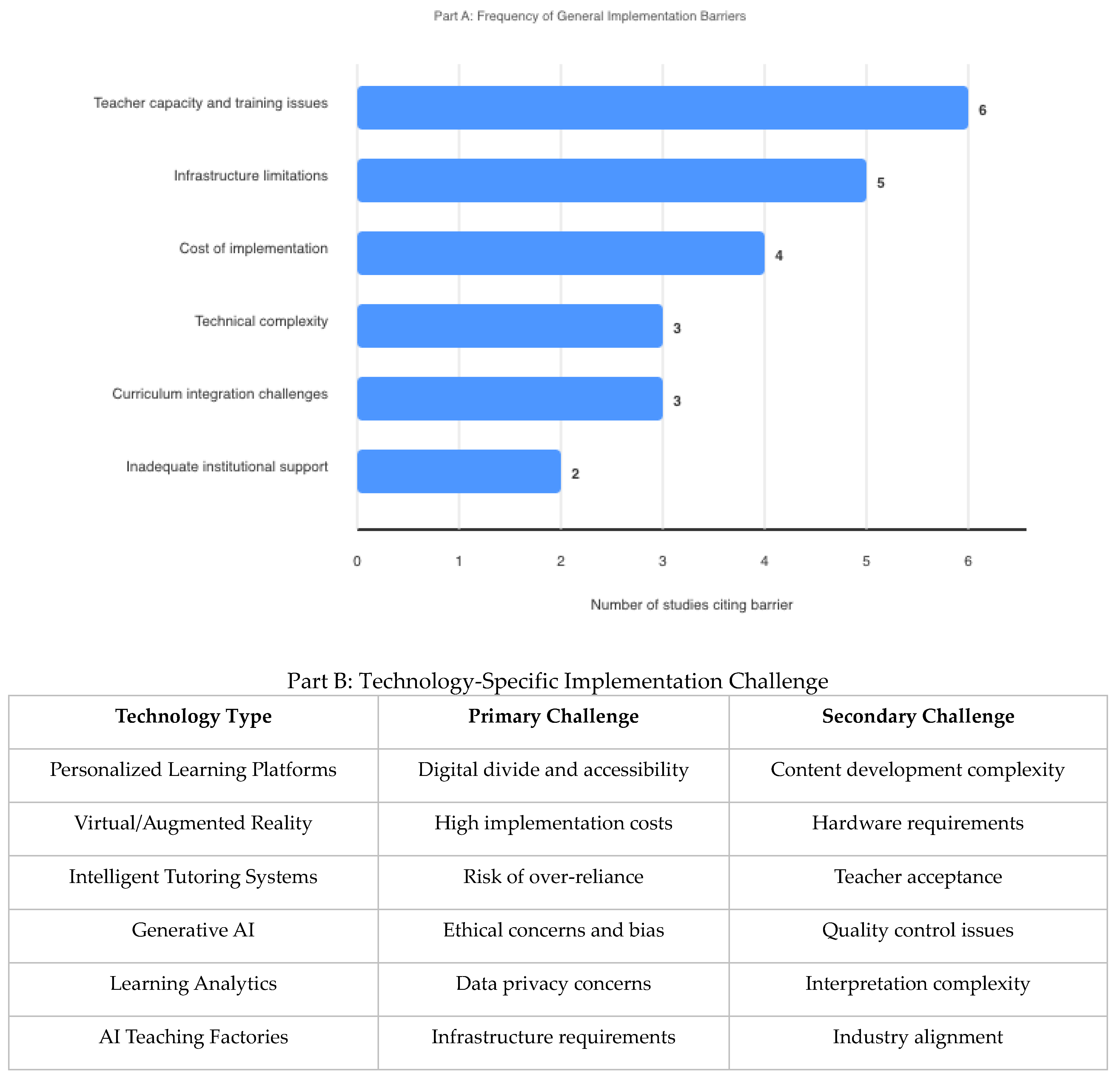

Research consistently identifies several key barriers to effective AI adoption, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

Six studies noted that training and capacity issues among teachers were the most common obstacles. Research from Indonesia and Germany highlighted the lack of essential AI literacy and technical abilities among TVET educators, which is crucial for effective implementation. According to Egloffstein et al. (2024), German VET stakeholders showed only an "ambiguous and superficial understanding of AI," whereas Wahjusaputri et al. (2024) indicated that Indonesian SMK teachers needed substantial upskilling.

Infrastructure limitations ranked as the second most common barrier across five studies, especially in settings that demand advanced technical setups. Research revealed ongoing issues with internet connectivity, outdated equipment, and a lack of adequate computing resources, particularly for resource-heavy applications such as AI simulators and XR environments. Additionally, four studies emphasized the cost of implementation as a significant constraint, particularly affecting smaller institutions and those in developing economies. The substantial initial investment required for advanced AI tools, including sensor-rich simulators, was noted as a barrier to broader adoption.

Additional obstacles consisted of the technical intricacies of AI systems (3 studies), difficulties in incorporating AI into current curricula (3 studies), and insufficient institutional support structures (2 studies).

3.4.2. Student and Teacher Perceptions

Overall, student attitudes towards AI in TVET were mainly favorable in various studies. Research conducted by Idris et al. (2025), Ab Hamid et al. (2023), and Baharin et al. (2025) indicated strong student approval and perceived benefits from AI-driven educational tools. The UTAUT analysis identified performance expectancy, or the belief that AI could enhance their learning results, as a primary factor driving adoption.

Conversely, teacher perceptions indicated a greater complexity. Although instructors acknowledged possible benefits, they voiced concerns regarding their level of preparedness. Deitmer et al. (2024) discovered that teachers exhibited a limited grasp of AI's practical uses in education, even within technology-centric vocational schools in Germany. These results highlight the urgent requirement for professional development aimed at teachers before the extensive implementation of AI.

3.4.3. Contextual Success Factors

Various contextual factors were identified as crucial for successful AI integration. Mohamad et al. (2024) and Wahjusaputri et al. (2024) emphasized the need for industry partnerships, underscoring the role of collaboration with employers in crafting relevant AI-enhanced curriculum elements. Ning and Suqin (2024) suggested a phased approach to implementation, enabling institutions to introduce AI technologies and gradually build capacity over time. According to Egloffstein et al. (2024), involving teachers in resource development through participatory design methods enhanced acceptance and practical application. Furthermore, several studies highlighted that strong institutional leadership, encompassing administrative backing and a clear strategic vision, contributed to more effective AI adoption in diverse contexts.

3.5. Evidence Gaps and Research Directions

Our fourth research question identified gaps in the current evidence base. Analysis of the reviewed literature reveals several significant limitations.

3.5.1. Methodological Limitations

Most perception-driven studies (45% of the literature reviewed), compared to controlled experiments (9%), highlight a notable methodological gap. Most studies depend on self-reported results instead of objective skill evaluations. Several authors have observed that "much of the AI-in-TVET literature is focused on perceptions, adoption barriers, or pilot implementations, with limited longitudinal or employability outcome data."

3.5.2. Temporal and Contextual Gaps

Almost all studies conducted are short-term evaluations or cross-sectional analyses, and none follow outcomes past the initial post-intervention periods. Multiple papers explicitly recognize this limitation, including Mohd Fahimey et al. (2024), who advocate for longitudinal studies to evaluate lasting effects.

Research is heavily concentrated in certain areas, especially Malaysia and parts of Europe. This results in significant gaps in our knowledge of AI application performance across various economic and educational contexts, particularly in resource-limited settings.

3.5.3. Technology Classification and Transparency

Several studies reference "AI" but do not clarify the nature or extent of machine learning components, algorithmic frameworks, or adaptation strategies. This lack of technical clarity makes it difficult to assess which specific AI attributes impact the observed results.

3.5.4. Emerging Research Priorities

The literature identifies several key areas for future research based on existing gaps. Conducting longitudinal studies that monitor skill retention and employment outcomes beyond immediate post-training periods would help overcome current temporal limitations. The field would also gain from standardized assessment frameworks that allow for cross-study comparisons of vocational competencies and support more comprehensive meta-analyses. Replicating effective interventions in various geographic and economic contexts would enhance our understanding of generalizability as well as context-specific factors. Testing different approaches to teacher professional development would tackle the significant issue of educator preparedness. Lastly, comparative studies on AI deployment across various vocational domains and skill types would clarify where AI interventions yield the greatest advantages. The Discussion section provides further details on these research priorities.

4. Discussion

We discuss our findings in relation to our research questions, highlighting key insights and situating them within the wider context of educational technology literature.

4.1. AI Technologies and Their Outcomes in TVET

Our review presents evidence that tools enhanced by AI can boost vocational training results, especially in hands-on, simulated environments. The most robust empirical backing arises from controlled trials of XR and robotic simulators, which reveal statistically significant improvements in skill proficiency. The multi-sensor AI welding simulator (Lee et al., 2021) illustrates AI's capability to deliver immediate, tailored feedback during technical skill training—a vital aspect of practical vocational education. Likewise, the AI teaching factory model (Wahjusaputri et al., 2024) demonstrates how AI can be integrated into real-world learning settings to improve practical skills.

These results are consistent with wider educational studies on AI-enhanced learning, indicating that adaptive technologies can tailor instruction and hasten skill development (Holmes et al., 2022). However, the TVET environment especially gains from AI implementations that merge physical and digital components—referred to as "embodied AI learning"—where sensor data enables immediate feedback on motor skills and technical processes. This provides a clear advantage compared to purely cognitive AI applications in general education settings.

The effectiveness of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT in TVET environments is still not well-supported by empirical evidence. Although surveys suggest favorable opinions, the absence of objective skill assessments complicates the evaluation of their influence on vocational skills. This shortcoming illustrates a wider trend in educational technology studies, where excitement for innovative tools frequently arises before thorough assessments are conducted (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2023).

The outcome patterns among different technology types indicate that AI's most notable current benefit in TVET lies in its capacity to deliver personalized and instantaneous feedback on intricate physical tasks that would normally necessitate extensive instructor oversight. This aligns with cognitive apprenticeship models in vocational education (Collins et al., 1991), where AI acts as a relentless expert mentor, guiding practice with precision and reliability beyond human capabilities. Future implementations should prioritize this unique advantage instead of imitating instructional elements where human teachers shine.

4.2. Contexts and Comparative Findings

The geographic concentration of research in certain areas highlights key contextual trends in the integration of AI into TVET systems. Malaysia's focus on perception studies and adoption frameworks indicates its national commitment to digital transformation in technical education (UNESCO, 2023). Germany's emphasis on enhancing teacher capacity corresponds with its historical focus on educator-centered vocational reform. These trends imply that cultural and policy environments significantly influence research priorities, a conclusion that aligns with comparative education literature on the adoption of educational technology (Selwyn, 2020).

Our review's limited geographic coverage signals a need for caution in making global generalizations. Additional evidence points to unique methods of AI integration in regions not included in our systematic review. For example, research from North America focuses on industry-driven applications and work-integrated learning models (Sun & Pratt, 2024), whereas emerging studies from Africa showcase mobile-first AI solutions aimed at addressing infrastructure challenges (not included in our systematic review, but present in the broader literature). These regional differences illustrate varying resource conditions, specific policy priorities, and educational traditions that influence strategies for AI implementation.

Compared to general vocational fields, the more robust empirical results in manufacturing and physical trades reveal an important insight: AI's value may vary across different vocational sectors. The varying impact seems associated with the types of skills being cultivated, showing the greatest advantages in areas that demand precise physical actions or procedural skills that are amenable to algorithmic evaluation. This observation questions the frequently universal perspective on AI in education and emphasizes the necessity for tailored implementation theories specific to different domains.

Our examination of methodological discrepancies among studies highlights a troubling imbalance. The prevalence of perception metrics compared to skill evaluations restricts the field's capacity to make definitive conclusions regarding AI's effect on vocational competence. This reflects broader issues in educational technology research concerning the dependence on self-reported results rather than performance evaluations (Kirkwood & Price, 2014). Future research must rectify this imbalance to establish a more dependable evidence base.

The TPACK framework (Mishra & Koehler, 2006) provides an insightful perspective on these contextual differences. Our review of successful AI implementations reveals a robust combination of technological knowledge (AI capabilities), pedagogical methods (suitable feedback mechanisms), and content knowledge (specific skill requirements for the domain). When any of these components is absent, outcomes tend to be less favorable, particularly when teachers lack AI literacy or where technology is deployed without appropriate adaptations to the domain.

4.3. Implementation Barriers and Success Factors

Our review highlights systemic challenges in AI adoption, revealing significant barriers related to teacher capacity and infrastructure that go beyond specific technologies. The observation that TVET educators frequently lack basic AI literacy corresponds with recent research on vocational teachers' digital readiness, underscoring a vital gap in professional development.

This pattern indicates that AI's technical promise in TVET is likely limited more by the ecosystems where it is applied than by the technologies themselves. For successful implementation, a supportive infrastructure, including technical resources as well as human and organizational capabilities, is essential. The gap between generally positive student perceptions and more cautious teacher attitudes highlights this tension between technology's potential and practical realities.

The identified success factors—industry partnerships, phased implementation, participatory design, and institutional leadership—suggest an ecological model for AI adoption in TVET. This model acknowledges that integrating technology goes beyond just obtaining new tools; it involves fostering supportive environments that enable practical use. This viewpoint corresponds with socio-technical systems theory (Davis et al., 2014), highlighting the interplay between social and technical elements in educational innovation.

A significant highlight is the focus on industry collaborations in various studies. The strong link between TVET and employment settings enables more genuine and pertinent AI applications, particularly when employers participate actively in the design and execution processes. This insight expands upon previous research regarding industry-education partnerships in vocational training (Billett, 2014), specifically regarding AI integration.

Cost considerations, although important, are influenced by perceived value and strategic alignment. When AI applications effectively meet specific instructional needs or employment demands, institutions tend to be more inclined to make investments despite limited resources. This indicates that promoting AI in TVET should emphasize not only technological capabilities but also clear connections to appreciated results in particular vocational settings.

4.4. Ethical and Privacy Considerations

In addition to the previously identified implementation obstacles and success factors, the growing integration of AI in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) brings forth significant ethical issues that need careful consideration. Recent research points to apprehensions regarding data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the risk of excessive dependence on AI technologies (Mundo et al., 2024; Çela et al., 2024). As TVET institutions increasingly gather student data to enhance adaptive learning systems and create personalized pathways, establishing clear policies on data ownership, consent, and usage is crucial. Likewise, addressing algorithmic bias—where AI systems might unintentionally reinforce or exacerbate existing inequalities—demands proactive oversight and strategies for mitigation.

The risk of becoming overly dependent on AI tools prompts a need to balance technological support with human insight and mentorship. This is especially crucial in vocational education, where hands-on knowledge and contextual learning play a key role. Consequently, effective AI integration should encompass ethical guidelines and governance frameworks that tackle these issues while enhancing positive effects on learning and employability results.

4.5. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Our systematic review highlights significant methodological and contextual limitations within the current evidence base, suggesting the need for a targeted research agenda to enhance our understanding of AI in TVET. The prevalence of perception-based and short-term studies identified in our review poses a considerable limitation, reflecting broader issues in educational technology research (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2023). The field's dependence on self-reported outcomes instead of objective skill assessments restricts our capacity to reach meaningful conclusions regarding AI's influence on the development of vocational competence and its application in workplace environments.

We suggest five key research directions that tackle these limitations and could greatly advance the field:

To grasp AI's long-term effects on vocational training, it's crucial to conduct longitudinal research that examines employment outcomes. Upcoming studies should track TVET graduates as they enter the workforce, exploring questions like: How effectively do skills gained through AI-enhanced training apply in workplace settings? What is the relationship between AI-driven learning experiences and career progression? How long-lasting are the technical skills acquired through AI-based instruction compared to traditional teaching methods? Ideally, these studies will use mixed-methods approaches, integrating quantitative performance data with qualitative insights into how skills are utilized in genuine work situations.

Secondly, creating and validating standardized assessment frameworks would allow for more significant comparisons across studies and meta-analyses. Researchers ought to collaborate to create tailored instruments that assess both technical proficiency and wider competencies. Important research questions are: What defines meaningful skill enhancement in various vocational domains, and what are the reliable methods of measurement? How can we standardize AI-related learning outcomes while honoring the diversity of vocational settings? Which assessment strategies most effectively capture procedural skill mastery and advanced competencies pertinent to Industry 4.0 environments?

Third, it is essential to conduct multi-context replication studies to confirm the generalizability of effective AI interventions across various settings. This research avenue should explore: How do specific AI applications function in different resource environments, cultural contexts, and institutional frameworks? What modifications are needed to ensure effectiveness when moving AI solutions between different contexts? Which contextual factors most notably influence the relationship between AI implementation and learning outcomes? This research is crucial, especially considering the current concentration of studies in a limited number of countries.

Fourth, evaluating teacher professional development strategies through experiments would tackle the recurring issue of educator readiness. Key research questions in this area are: Which professional development models best equip TVET instructors to incorporate AI tools? In what ways does teachers' AI literacy affect student learning outcomes? What is the best sequence and intensity of professional development for fostering sustainable AI adoption? These studies should focus on quantifiable changes in instructional practices and student learning, rather than relying solely on self-reported satisfaction.

Fifth, analyzing AI applications in various vocational fields will shed light on areas where these technologies provide the greatest advantages. This research should explore: How does AI's effectiveness differ among various skill types (e.g., procedural, conceptual, interpersonal)? Which vocational sectors display the strongest evidence of improved results from AI integration? What unique traits of vocational skills benefit the most from AI-enhanced teaching? Such efforts would enable institutions to allocate limited resources more effectively towards impactful implementations.

Our findings indicate that we need frameworks tailored for AI integration in TVET that consider the unique aspects of vocational education. Although existing models like TPACK are helpful as a starting point, they must be expanded to better capture the hands-on nature of many vocational skills, their close ties to industry demands, and the varied infrastructure of TVET institutions globally. Theoretical research should aim to create models that clearly outline how AI technologies interact with the specialized teaching methods used in vocational education, especially in linking theory to practice.

Future research should adopt more rigorous designs that integrate quantitative skill development assessments with qualitative insights into implementation practices. Given the complex socio-technical systems in which AI operates in TVET, multi-method approaches are especially suitable. Furthermore, researchers ought to report AI components—such as learning algorithms, adaptation methods, and input features—more transparently to enable replication and enhance the theoretical understanding of the ways in which specific technological elements affect learning outcomes.

Addressing these research priorities would significantly strengthen the evidence base for AI in TVET and provide policymakers and practitioners with more dependable guidance for implementation decisions. The field needs this improved empirical foundation to progress beyond the current state of promising but limited evidence toward a more developed understanding of how AI can effectively transform vocational education and training.

4.6. Practical Implications and Recommendations

Our research indicates several practical considerations for TVET institutions, policymakers, and practitioners aiming to incorporate AI technologies. Firstly, placing emphasis on embodied, hands-on AI applications that significantly improve practical skill development seems the most effective, supported by more robust empirical evidence for simulators and teaching factories than for alternative methods. These technologies utilize AI's ability to deliver personalized, prompt feedback on complex tasks, aligning with TVET's fundamental goal of ensuring occupational competence.

Professional development for teachers must occur before implementing technology. The ongoing recognition of educators' capacity as a key obstacle suggests that effective AI integration demands significant investment in training TVET teachers, not just the purchase of technologies. This training must emphasize basic AI literacy and include relevant examples of practical applications in teachers' specific fields of expertise.

Infrastructure constraints necessitate strategic solutions. Instead of pursuing broad technological changes, institutions should concentrate on particular high-value applications, like simulators for hazardous or resource-heavy tasks, which offer distinct educational benefits. A phased approach enables capacity building and adaptation to local limitations while showcasing value through focused achievements.

Industry partnerships are crucial for successfully integrating AI into TVET. By involving employers in selecting technology, aligning curricula, and designing assessments, we can guarantee that AI-enhanced learning experiences meet workplace demands. Additionally, these partnerships can mitigate resource limitations by leveraging shared investment and expertise.

Standardized assessment methods can enhance evaluation and evidence-based decision-making. Institutions should design unified frameworks for assessing AI's influence on vocational skills, moving beyond mere satisfaction surveys to focus on objective competency metrics. These frameworks must correspond with industry skill standards and encompass both technical and transversal competencies.

Curriculum design methods need to adapt for effective AI integration. An approach focused on competencies ensures that the curriculum addresses specific industry skills, preparing students adequately for the workforce (Vasilev, 2025). A harmonious blend of AI tools and conventional teaching methods enables students to cultivate technical skills alongside essential soft skills, including creativity and problem-solving (Kong & Zhang, 2023). This equilibrium is crucial in vocational education, where practical experience and social learning are still significant, even with technological progress.

Industry partnerships need to move from mere consultation to genuine collaboration in creating curricula. Recent research shows that substantial industry participation in crafting AI-driven learning experiences greatly enhances their relevance and effectiveness (Sun & Pratt, 2024). These collaborations provide access to cutting-edge workplace technologies and guarantee that AI applications in TVET mirror real industry practices instead of merely simplified educational models.

These recommendations correspond with UNESCO-UNEVOC's (2023) framework for digital transformation in TVET, while prioritizing empirically validated elements related to AI adoption. By centering on these evidence-based strategies, institutions can transcend mere technological excitement and foster sustainable approaches to AI integration that truly improve vocational learning and employment results.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review of empirical evidence about artificial intelligence in technical and vocational education and training highlights a promising yet developing field. Our examination of 11 empirical studies that meet the criteria shows that AI technologies can improve vocational learning outcomes, particularly when used in hands-on, immersive applications that offer immediate, personalized feedback on technical tasks. This conclusion aligns with TVET's focus on practical skill development, suggesting a unique advantage for AI applications in vocational settings compared to general education contexts.

The synthesis of research across our four guiding questions reveals several key insights. Firstly, the strongest empirical evidence is from AI-enhanced simulators and teaching factories, which showcase measurable improvements in technical skill acquisition. Meanwhile, other applications exhibit promising but less thoroughly validated outcomes. Secondly, there are considerable contextual differences across geographic areas and vocational fields, with the strongest results seen in manufacturing and physical trades that require precise procedures. Thirdly, the repeated identification of teacher capacity and infrastructure challenges as main barriers to implementation emphasizes the socio-technical aspects of effectively integrating AI in TVET. Lastly, significant methodological shortcomings—especially the prevalence of perception studies and the lack of longitudinal research—limit our understanding of AI's long-term effects on vocational skills and employability.

These findings hold significant implications for various stakeholders. For policymakers, our review indicates that strategic investments should emphasize enhancing technological infrastructure and comprehensive training programs for teachers. For TVET institutions, the evidence suggests that initial AI implementation efforts should target high-value applications in areas with well-defined skill assessment criteria, while simultaneously building the capacity for wider integration in the future. For researchers, the gaps we've identified underscore the necessity for more rigorous, standardized, and longitudinal research designs that accurately measure skill outcomes and employment effects.

The field of AI in TVET is at a crucial juncture, offering substantial potential to reshape vocational education if implementation challenges are effectively tackled. Looking ahead, creating AI integration frameworks tailored for TVET, alongside strategic collaborations with industries and evidence-based methods, could enhance the ability of vocational education to meet the needs of fast-changing workplaces. While the potential of AI to improve vocational learning is considerable, achieving this potential necessitates a shift from mere technological excitement to strategic, evidence-based implementation that recognizes the unique features of vocational education and the varied contexts it functions in globally.