1. Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of disability, major neurocognitive disorder, and death worldwide. Post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) affects up to 50% of stroke survivors, according to studies conducted in high-income countries.(Barbay et al., 2018; Pendlebury & Rothwell, 2019) Notably, PSCI is partly independent of the modified Rankin Scale used to assess functional outcomes,(Schwamm, 2022) yet it significantly impacts patients’ daily lives.(Rohde et al., 2019) Furthermore, PSCI limits independence, social participation,(Stolwyk et al., 2021) and is associated with increased rates of mortality, institutionalization, and depression.(Obaid et al., 2020)

Guidelines recommend routine cognitive screening for all stroke survivors,(Quinn et al., 2021) but this is rarely implemented, especially in low-resource settings. Limited awareness of PSCI's long-term impact,(Stolwyk et al., 2021) combined with a lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate screening tools, contributes to low screening rates.(Quinn et al., 2021) Emerging data suggest that PSCI may pose an even greater public health burden in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Stroke incidence in SSA is estimated to be two- to threefold higher than in Western Europe and North America,(Akinyemi et al., 2021) and often affects individuals in their most productive decades of life. Cognitive sequelae following stroke therefore have substantial implications not only for individual patients, but also for families and national productivity. Despite this, the epidemiology of PSCI in SSA remains poorly documented. Recent large-scale SSA studies support the urgency of addressing PSCI. A 2024 meta-analysis by Aytenew et al. pooled data from 1,566 stroke survivors and reported a PSCI prevalence of 59.6%, with significant associations with age, education level, functional status, and stroke laterality.(Aytenew et al., 2024) Similarly, the CogFAST Nigeria study by Akinyemi et al.(Akinyemi et al., 2014)found that nearly half of stroke survivors developed vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) within three months of stroke, with strong links to vascular risk factors, medial temporal atrophy, and lower education. Some studies have reported prevalence rates comparable to those in high-income countries,(Akinyemi et al., 2014) but the lack of validated cognitive screening tools adapted to low-literacy contexts hampers reliable measurement, screening and follow-up. Interestingly, the Identification of Dementia in Elderly Africans (IDEA) cognitive screen was developed in rural Tanzania specifically taylored for SSA populations, and has shown validity in detecting major neurocognitive disorders in both community and hospital settings in Tanzania and Nigeria.(Gray et al., 2014a; Paddick et al., 2015).

Building on this context, we aimed to assess the performance of the IDEA screen in detecting PSCI among stroke survivors in Guinea and Cameroon, and to evaluate its applicability in two Western African populations. Our goal was to determine whether IDEA is a feasible, effective, and culturally relevant tool for routine cognitive screening in SSA stroke care.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Participants were recruited from two urban neurology departments: Ignace Deen Hospital in Conakry, Guinea, and Bafoussam Regional Hospital in Bafoussam, Cameroon. The stroke group included adult patients (≥ 40 years) with a clinical diagnosis of stroke according to WHO criteria, confirmed by CT imaging. Inclusion criteria for stroke patients were: (1) first-ever or recurrent ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke; (2) ability to undergo cognitive screening within 30 days post-stroke; and (3) consent by the participant or caregiver. Exclusion criteria were: history of pre-stroke dementia, severe aphasia or delirium precluding testing, or major psychiatric illness. The control group consisted of healthy older adults recruited from hospital visitors, community health workers, and relatives of patients. These individuals were age-matched as closely as feasible and screened to exclude any history of stroke, neurological or psychiatric conditions, or current cognitive complaints. Equal proportions were recruited from Guinea and Cameroon. The study was approved by institutional Ethics Committees. Each participant was given verbal information about the study and allowed to ask questions. Written informed consent was obtained by signature. An assent was sought from a close relative if the participant was unable to give consent, due to cognitive impairment.

2.2. Methods

Demographic variables (age, sex, literacy), vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes), and clinical information (stroke subtype, NIHSS score at admission) were collected from medical records and structured interviews. Stroke subtypes were categorized as ischemic or hemorrhagic.

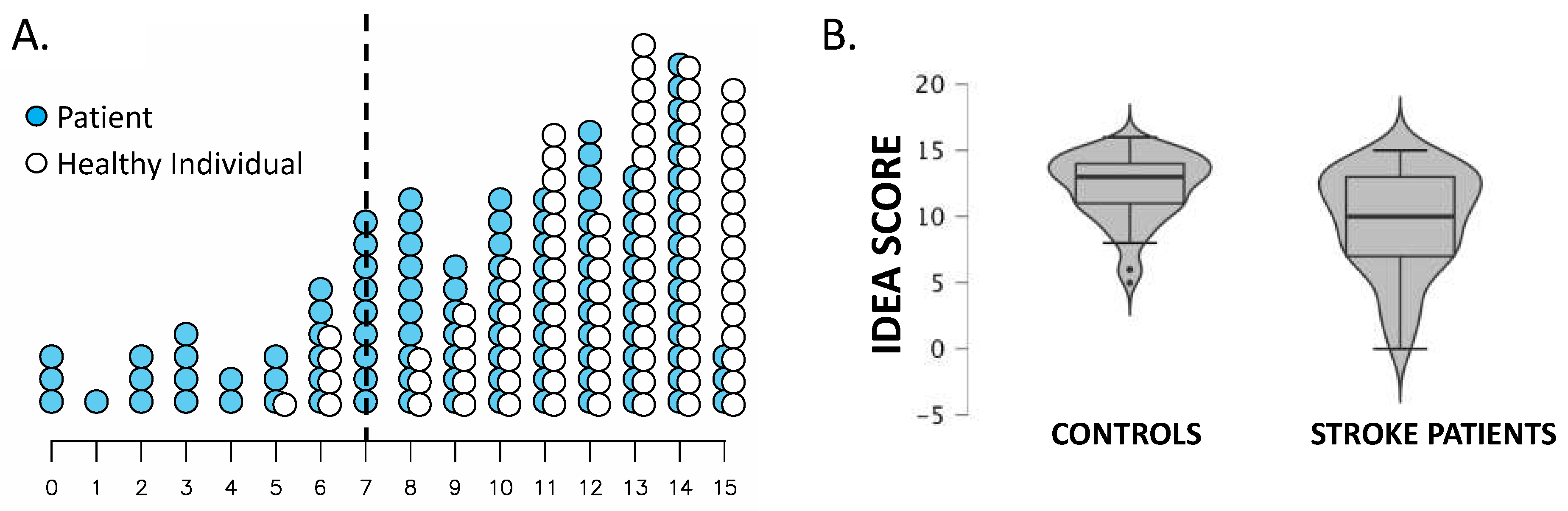

The IDEA cognitive screen includes six domains: abstraction, orientation, long-term memory, categorical verbal fluency, delayed recall, and visuospatial construction. It is scored from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating better cognition. Items were administered in the local language by trained clinicians. A cut-off score for abnormal performance was derived from the control population: cognitive impairment was defined as a score ≤ 7, corresponding to more than 2 standard deviations below the control mean. This threshold reflects approximately the 2.5th percentile, a standard convention in screening. IDEA testing in stroke patients was conducted within one month post-stroke. All assessments were completed in a quiet clinical setting and supervised by neurologists.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS v26. Continuous variables were reported as means ± standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Welch’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables between groups due to unequal variances and sample sizes. Chi-square tests were used for categorical comparisons. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied. Subgroup analysis (e.g., by age, sex, or comorbidities) was not performed due to sample size constraints.

3. Results

A total of 91 neurologically healthy individuals were included as controls. The mean age was 61 ± 12 years, with 52% male participants. Literacy rate was 79%, while hypertension and diabetes were present in 22% and 9.7% of subjects, respectively. The mean IDEA score in this group was 12 ± 2.4. Based on this distribution, a cut-off score of ≤7 (two standard deviations below the mean) was established to define probable cognitive impairment.

In the stroke group, 111 patients were included. Their mean age was 65 ± 9 years, and 50% were male. Literacy rate was 70%, and hypertension and diabetes were present in 70% and 49% of patients, respectively. Ischemic strokes accounted for 78% of cases. The mean NIHSS score at admission was 9.9 ± 5.8.

Mean IDEA scores were significantly lower in stroke patients (9.6 ± 3.2) than in healthy controls (12 ± 2.4; Welch’s t-test, t = 6.32, p < 0.001). Additionally, 31 stroke patients (28%) and 5 healthy controls (5.5%) scored ≤7, indicating probable cognitive impairment (χ² = 20.5, p < 0.001).

Group comparisons revealed no significant difference in sex distribution (χ² = 0.08, p = 0.78) or literacy rates (χ² = 2.45, p = 0.12) between groups. However, hypertension (χ² = 46.6, p < 0.001) and diabetes (χ² = 32.1, p < 0.001) were significantly more prevalent in the stroke group.

Participant characteristics and statistical comparisons are presented in

Table 1.

The

Figure 1. Illustrates IDEA score distribution.

4. Discussion

Main findings from our study are that (i) IDEA is adapted and effective to screen for cognitive disorders in Guinea and Cameroon and that (ii) Using IDEA cut-off, PSCI may affect up to 30% of post-stroke patients.

Those results from Guinean and Cameronian cohorts are likely to be generalizable in similar settings in SSA. Our cohort of stroke patients that was included in this project matches the characteristics from prior large stroke cohorts from Guinea,(Cisse et al., 2022) Cameroon,(Nkoke et al., 2015) South-Africa,(Connor et al., 2009) or the stroke Investigative Research & Educational Network (SIREN) collaboration(Sarfo et al., 2023) in terms of age, sex, ischemic stroke proportion and NIHSS severity. So, while limited by the sample sizes of our cohorts, the results from this report are likely to be generalizable to SSA healthy individuals as well as in SSA stroke patients in general. Similarly, our healthy cohort scored strickingly close performances compared to healthy individuals from Nigeria and Tanzania in whom IDEA was validated.(Gray et al., 2014b, 2021; Paddick et al., 2015) Our control cohort, comprising literate and low-literate older adults from Guinea and Cameroon, achieved a mean IDEA score of 12 ± 2.4, highly comparable to normative values reported in Tanzania and Nigeria by Gray et al. (2021), who found median scores ranging from 10–13 depending on age, education, and sex. This similarity suggests that our control population is representative of wider SSA contexts and supports the use of a ≤7 cut-off for identifying cognitive impairment, as validated in previous IDEA studies. The IDEA tool thus shows promise as a generalizable screening instrument across SSA.

The 28% prevalence of PSCI detected using IDEA is strikingly close to what has been reported in stroke survivors assessed with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in high-income settings. (Pendlebury & Rothwell, 2019b; Weaver et al., 2021) However, tools like the MoCA often perform poorly in low-literacy SSA populations, with studies such as Masika et al. (2021) in rural Tanzania showing education-dependent floor effects. By contrast, IDEA showed less cultural bias and comparable diagnostic accuracy, even when evaluated alongside MoCA.

Our results on PSCI prevalence are on the lower edge of those reported align on recent Sub-Saharan African (SSA) meta-analysis on post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI). Aytenew et al. (2024) reported a pooled PSCI prevalence of 59.6% across SSA. This relatively lower rate of PSCI in Guinea may be attributed to the fact that many severe stroke cases likely failed to reach the hospital, due to limited accessibility. Barriers such as distance, transportation costs, and the lack of organized medical transport hinder timely admission. A 2014 survey conducted at the Neurology Ward of Ignace Deen Hospital revealed that only 2% of stroke patients arrived by ambulance, 46% used public transportation, 27% arrived by personal car, and the remainder relied on alternative or informal means.(Cisse et al., 2019) While vascular risk factors like hypertension and diabetes can modestly affect cognitive performance in their own right, Higher rates of diabetes and HBP in our stroke patients could have biased negatively the results of IDEA screening independently of the stroke event. Diabetic and HBP patients tend to perform poorer than matched-controls on neuropsychological testing.(Gupta et al., 2024; Iadecola et al., 2016; Kinattingal et al., 2023) However, those lower performances are subtle, inconsistent across studies and do not significantly impact cognitive screening,(Gupta et al., 2024; Iadecola et al., 2016; Kinattingal et al., 2023) suggesting that the bulk of PSCI detected by IDEA are related to the stroke event.

Despite being field-friendly, screening tools cannot replace full length neuropsychological test batteries that have higher sensitivities to detect and characterize cognitive impairments, as shown by the rates of PSCI amounting to 50% when more comprehensive evaluation are used.(Barbay et al., 2018; Lo et al., 2019) Still, dedicated bedside assessment tests for PSCI such as the Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS) have gained acceptance for the assessment of cognitive impairments with robust validity and reliability.(Demeyere et al., 2015) The OCS is a neurobehavioral battery, like IDEA, that allows a rapid assessment of several cognitive domains (i.e., language, memory, attention, calculation and praxis) and showed high predictive abilities for longterm stroke functional outcome.(Bisogno et al., 2023) This shows that adapted bedside cognitive tests can help predict stroke functional outcome and orient patient care and rehabilitation. In the SSA context where full neuropsychological test batteries and neuropsychologists are scarce and/or inaccessible, the IDEA could stand as a pragmatic screening test to identify individuals who may be cognitively impacted by a stroke in SSA and help design both public health and rehabilitation strategies as well as attract attention to a relevant and under-recognized consequence of stroke in Africa.

5. Conclusions

Ultimately, our findings underscore the relevance and feasibility of implementing routine cognitive screening for stroke patients in SSA using the IDEA tool. Doing so would not only support early intervention and rehabilitation but also bring attention to a major yet underrecognized consequence of stroke in Africa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ACF, FY, GN; methodology, ACF, FY, GN; formal analysis, GN.; data curation, MD.; writing—original draft preparation, ACF, FY, GN; writing—review and editing, ACF, FY, MD, GN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and, approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Each participant was given verbal information about the study and allowed to ask questions. Written informed consent was obtained by signature. An assent was sought from a close relative if the participant was unable to give consent, due to cognitive impairment.

Data Availability Statement

anonymized data can be shared upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akinyemi, R. O., Allan, L., Owolabi, M. O., Akinyemi, J. O., Ogbole, G., Ajani, A., Firbank, M., Ogunniyi, A., & Kalaria, R. N. (2014). Profile and determinants of vascular cognitive impairment in African stroke survivors: the CogFAST Nigeria Study. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 346(1–2), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNS.2014.08.042. [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, R. O., Ovbiagele, B., Adeniji, O. A., Sarfo, F. S., Abd-Allah, F., Adoukonou, T., Ogah, O. S., Naidoo, P., Damasceno, A., Walker, R. W., Ogunniyi, A., Kalaria, R. N., & Owolabi, M. O. (2021). Stroke in Africa: profile, progress, prospects and priorities. Nature Reviews Neurology 2021 17:10, 17(10), 634–656. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00542-4. [CrossRef]

- Aytenew, T. M., Kefale, D., Birhane, B. M., Kebede, S. D., Asferie, W. N., Kassaw, A., Tiruneh, Y. M., Legas, G., Getie, A., Bantie, B., & Asnakew, S. (2024). Poststroke cognitive impairment among stroke survivors in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-024-19684-3/FIGURES/8. [CrossRef]

- Barbay, M., Taillia, H., Nédélec-Ciceri, C., Bompaire, F., Bonnin, C., Varvat, J., Grangette, F., Diouf, M., Wiener, E., Mas, J. L., Roussel, M., & Godefroy, O. (2018). Prevalence of Poststroke Neurocognitive Disorders Using National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network, VASCOG Criteria (Vascular Behavioral and Cognitive Disorders), and Optimized Criteria of Cognitive Deficit. Stroke, 49(5), 1141–1147. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018889. [CrossRef]

- Bisogno, A. L., Franco Novelletto, L., Zangrossi, A., De Pellegrin, S., Facchini, S., Basile, A. M., Baracchini, C., & Corbetta, M. (2023). The Oxford cognitive screen (OCS) as an acute predictor of long-term functional outcome in a prospective sample of stroke patients. Cortex, 166, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CORTEX.2023.04.015. [CrossRef]

- Cisse, F. A., Damien, C., Bah, A. K., Touré, M. L., Barry, M., Djibo Hamani, A. B., Haba, M., Soumah, F. M., & Naeije, G. (2019). Minimal Setting Stroke Unit in a Sub-Saharan African Public Hospital. Frontiers in Neurology, 10(JUL). https://doi.org/10.3389/FNEUR.2019.00856. [CrossRef]

- Cisse, F. A., Ligot, N., Conde, K., Barry, D. S., Toure, L. M., Konate, M., Soumah, M. F., Diawara, K., Traore, M., & Naeije, G. (2022). Predictors of stroke favorable functional outcome in Guinea, results from the Conakry stroke registry. Scientific Reports, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-022-05057-6. [CrossRef]

- Connor, M. D., Modi, G., & Warlow, C. P. (2009). Differences in the nature of stroke in a multiethnic urban South African population: the Johannesburg hospital stroke register. Stroke, 40(2), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521609. [CrossRef]

- Demeyere, N., Riddoch, M. J., Slavkova, E. D., Bickerton, W. L., & Humphreys, G. W. (2015). The Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS): validation of a stroke-specific short cognitive screening tool. Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 883–894. https://doi.org/10.1037/PAS0000082. [CrossRef]

- Gray, W. K., Paddick, S. M., Kisoli, A., Dotchin, C. L., Longdon, A. R., Chaote, P., Samuel, M., Jusabani, A. M., & Walker, R. W. (2014a). Development and Validation of the Identification and Intervention for Dementia in Elderly Africans (IDEA) Study Dementia Screening Instrument. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 27(2), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988714522695. [CrossRef]

- Gray, W. K., Paddick, S. M., Kisoli, A., Dotchin, C. L., Longdon, A. R., Chaote, P., Samuel, M., Jusabani, A. M., & Walker, R. W. (2014b). Development and Validation of the Identification and Intervention for Dementia in Elderly Africans (IDEA) Study Dementia Screening Instrument. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 27(2), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988714522695. [CrossRef]

- Gray, W. K., Paddick, S. M., Ogunniyi, A., Olakehinde, O., Dotchin, C., Kissima, J., Urasa, S., Kisoli, A., Rogathi, J., Mushi, D., Adebiyi, A., Haule, I., Robinson, L., & Walker, R. (2021). Population normative data for three cognitive screening tools for older adults in sub-Saharan Africa. Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 15(3), 339. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642021DN15-030005. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., Goyal, A., Rajan, R., Vishnu, V. Y., Kalaivani, M., Tandon, N., Srivastava, M. V. P., & Gupta, Y. (2024). Validity of Montreal Cognitive Assessment to Detect Cognitive Impairment in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Therapy, 15(5), 1155–1168. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13300-024-01549-Y/TABLES/6. [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C., Yaffe, K., Biller, J., Bratzke, L. C., Faraci, F. M., Gorelick, P. B., Gulati, M., Kamel, H., Knopman, D. S., Launer, L. J., Saczynski, J. S., Seshadri, S., & Al Hazzouri, A. Z. (2016). Impact of Hypertension on Cognitive Function: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension, 68(6), e67–e94. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000053. [CrossRef]

- Kinattingal, N., Mehdi, S., Undela, K., Wani, S. U. D., Almuqbil, M., Alshehri, S., Shakeel, F., Imam, M. T., & Manjula, S. N. (2023). Prevalence of Cognitive Decline in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Real-World Cross-Sectional Study in Mysuru, India. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(3), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/JPM13030524. [CrossRef]

- Lo, J. W., Crawford, J. D., Desmond, D. W., Godefroy, O., Jokinen, H., Mahinrad, S., Bae, H. J., Lim, J. S., Köhler, S., Douven, E., Staals, J., Chen, C., Xu, X., Chong, E. J., Akinyemi, R. O., Kalaria, R. N., Ogunniyi, A., Barbay, M., Roussel, M., … Sachdev, P. S. (2019). Profile of and risk factors for poststroke cognitive impairment in diverse ethnoregional groups. Neurology, 93(24), E2257–E2271. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008612. [CrossRef]

- Nkoke, C., Lekoubou, A., Balti, E., & Kengne, A. P. (2015). Stroke mortality and its determinants in a resource-limited setting: A prospective cohort study in Yaounde, Cameroon. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 358(1–2), 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2015.08.033. [CrossRef]

- Obaid, M., Flach, C., Marshall, I., Wolfe, C. D. A., & Douiri, A. (2020). Long-Term Outcomes in Stroke Patients with Cognitive Impairment: A Population-Based Study. Geriatrics 2020, Vol. 5, Page 32, 5(2), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/GERIATRICS5020032. [CrossRef]

- Paddick, S. M., Gray, W. K., Ogunjimi, L., Lwezuala, B., Olakehinde, O., Kisoli, A., Kissima, J., Mbowe, G., Mkenda, S., Dotchin, C. L., Walker, R. W., Mushi, D., Collingwood, C., & Ogunniyi, A. (2015). Validation of the Identification and Intervention for Dementia in Elderly Africans (IDEA) cognitive screen in Nigeria and Tanzania. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12877-015-0040-1. [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, S. T., & Rothwell, P. M. (2019). Incidence and prevalence of dementia associated with transient ischaemic attack and stroke: analysis of the population-based Oxford Vascular Study. 18(3), 248–258. http://www.thelancet.com/article/S1474442218304423/fulltext.

- Quinn, T. J., Richard, E., Teuschl, Y., Gattringer, T., Hafdi, M., O’Brien, J. T., Merriman, N., Gillebert, C., Huyglier, H., Verdelho, A., Schmidt, R., Ghaziani, E., Forchammer, H., Pendlebury, S. T., Bruffaerts, R., Mijajlovic, M., Drozdowska, B. A., Ball, E., & Markus, H. S. (2021). European Stroke Organisation and European Academy of Neurology joint guidelines on post-stroke cognitive impairment. European Stroke Journal, 6(3), I–XXXVIII. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969873211042192. [CrossRef]

- Rohde, D., Gaynor, E., Large, M., Mellon, L., Hall, P., Brewer, L., Bennett, K., Williams, D., Dolan, E., Callaly, E., & Hickey, A. (2019). The Impact of Cognitive Impairment on Poststroke Outcomes: A 5-Year Follow-Up. Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/0891988719853044, 32(5), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988719853044. [CrossRef]

- Sarfo, F. S., Singh, A., Adusei, N., Owusu, D., Akpa, O. M., Okekunle, A. P., Asowata, O. J., Akinyemi, J. O., Tagge MPH, R., Sarfo, F. S., Akpa, O. M., Ovbiagele, B., Akpalu, A., Wahab, K., Obiako, R., Komolafe, M., Owolabi, L., Ogbole, G., Fakunle, A., … Akpalu, J. (2023). Patient-level and system-level determinants of stroke fatality across 16 large hospitals in Ghana and Nigeria: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Global Health, 11, e575–e585. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00038-4. [CrossRef]

- Schwamm, L. H. (2022). In Stroke, When Is a Good Outcome Good Enough? New England Journal of Medicine, 386(14), 1359–1361. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJME2201330/SUPPL_FILE/NEJME2201330_DISCLOSURES.PDF. [CrossRef]

- Stolwyk, R. J., Mihaljcic, T., Wong, D. K., Chapman, J. E., & Rogers, J. M. (2021). Poststroke Cognitive Impairment Negatively Impacts Activity and Participation Outcomes. Stroke, 52(2), 748–760. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032215. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).