1. Introduction

Soil serves as a cornerstone for terrestrial life and underpins multiple ecosystem services, ranging from food production and water filtration to carbon sequestration and biodiversity conservation [

1]. Despite its fundamental importance, recent assessments indicate that a significant proportion of soils globally, including those within Europe, are experiencing substantial degradation due to land-use changes, intensive agriculture, urban expansion, and industrial pollution [

2,

3]. Such deterioration has raised a growing concern among policymakers, scientists, and the public regarding soil’s ability to support long-term ecosystem functions and human well-being.

Citizen science has emerged as a practical approach to address such challenges by involving non-specialist volunteers in research initiatives, thereby amplifying the reach and depth of soil monitoring data collection [

4,

5,

6]. Historically, citizen involvement in scientific exploration is well documented, extending back to early phenological observations in ancient China and Japan [

7]. In its modern form, citizen science leverages digital platforms, smartphone applications, and remote sensing technologies to gather large volumes of data, often at finer spatial and temporal resolutions than traditional methods can achieve [

8]. These participatory approaches have shown particular potential for monitoring indicators critical to soil health, including soil moisture, biodiversity, organic carbon content, and nutrient profiles [

9,

10]. Not only does this expand the pool of observational data, but it also strengthens public engagement and fosters science literacy [

11,

12].

Several investigations underscore the value of citizen-contributed data for soil assessments. Studies have demonstrated that when combined with Earth observation technologies, volunteer-collected data can refine soil characterization, enhance the accuracy of land-use maps, and identify localized degradation phenomena such as erosion or salinization [

13,

14]. Additionally, emerging work indicates that citizen science has the potential to address critical gaps in existing soil monitoring networks by incorporating data from underrepresented land types, such as urban, forested, and industrial areas, which are often overlooked in formal surveillance programs [

10]. However, significant challenges remain, including the need for rigorous data validation, standardization of protocols, and sustained volunteer motivation over extended monitoring periods [

15].

Despite these hurdles, the potential for harnessing public participation to protect and restore soil health is considerable. A growing body of literature highlights the role of citizen science in facilitating evidence-based policymaking, improving educational outcomes, and encouraging participatory community action. At the same time, recent projects funded under European research frameworks have begun to integrate volunteer-collected data into decision-making processes, further demonstrating the advantages and feasibility of collaborative soil monitoring initiatives [

4,

9,

16]. These developments present an opportunity to explore how citizen science can complement established methodologies in soil analysis, bridging knowledge gaps across diverse land uses and geographical regions.

The purpose of this review is, therefore, threefold: (1) to examine the current scientific understanding of how citizen science contributes to soil monitoring and protection; (2) to evaluate diverse initiatives and methods already in practice across different ecosystems; and (3) to outline ongoing challenges and potential solutions for harmonizing citizen-generated data with more conventional soil surveillance frameworks. Ultimately, the conclusions drawn aim to inform researchers, land managers, and policymakers about effective strategies for deploying citizen science to preserve and enhance soil quality. By synthesizing key findings and highlighting promising technological and institutional approaches, this paper seeks to contribute to both the scientific discourse and the practical, on-the-ground application of citizen-led research in soil stewardship.

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodological framework employed in this study, ensuring transparency and reproducibility. All procedures were conducted according to relevant guidelines, and any data or code essential for replication are available upon request. Large datasets generated or analyzed during this study have been deposited in publicly accessible repositories, as indicated in the respective subchapters. Ethical considerations are documented where applicable.

2.1. Literature Review

A systematic literature review was carried out to evaluate the role of citizen science in soil monitoring and protection. Both peer-reviewed articles and selected grey literature sources were covered. The following steps were taken:

Search Strategy: Databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and the ELICIT platform were queried using standardized keywords (e.g., “citizen science,” “soil monitoring,” “soil health,” “soil biodiversity”). Relevant publications and conference proceedings identified through snowball sampling were also included [

17,

18].

Selection Criteria: Articles were screened for relevance based on their focus on soil monitoring, land-use management, and public participation. Papers addressing environmental sensor data, digital soil mapping, and policy-related aspects of soil conservation were also reviewed to ensure methodological comprehensiveness [

19].

Data Extraction and Synthesis: For each selected source, the research objectives, study design, and reported outcomes were recorded. Emphasis was placed on identifying common indicators assessed in citizen science projects (e.g., soil organic carbon, pH, structure) and the technologies used (e.g., smartphone apps, web-based portals). A qualitative thematic analysis was performed to synthesize best practices and persisting gaps in the existing literature [

20,

21].

2.2. Assessment of European Initiatives

To examine how citizen science is implemented in European contexts, we investigated projects aligned with soil and land-use monitoring in-depth. Several EU-funded programs, national projects, and relevant consortia were surveyed:

Project identification: The European Commission’s Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS) database and pertinent project websites (e.g., LandSense, LUCAS, ECHO) were examined to identify ongoing or recently concluded initiatives [

22,

23,

24].

Data collection: Publicly available documents, such as final project reports, academic articles, and technical deliverables, were compiled. Where possible, supplementary materials (e.g., protocols and datasets) were retrieved from project repositories. Data extraction focused on objectives, methodological approaches (e.g., satellite-based Earth observation, in situ sampling), and stakeholder engagement strategies [

20].

Comparative analysis: Each initiative was evaluated on parameters such as geographic range, data collection type, validation procedures, and integration with policy or regulatory frameworks. Findings were consolidated to highlight patterns and to pinpoint methodological advances or efforts at standardization [

15,

25].

2.3. Inventory of Citizen Science Applications

A detailed survey of existing mobile and web-based applications supporting citizen science was undertaken. This included platforms explicitly designed for soil monitoring, biodiversity mapping, and environmental data collection (e.g., FotoQuest Go, iNaturalist, Pl@ntNet) [

26,

27,

28]. Key parameters were recorded, including user interface design, data collection workflow, data availability policies, and compliance with geospatial standards. Special attention was given to quality assurance mechanisms (e.g., expert review of user-submitted records and automated data validation process) [

15].

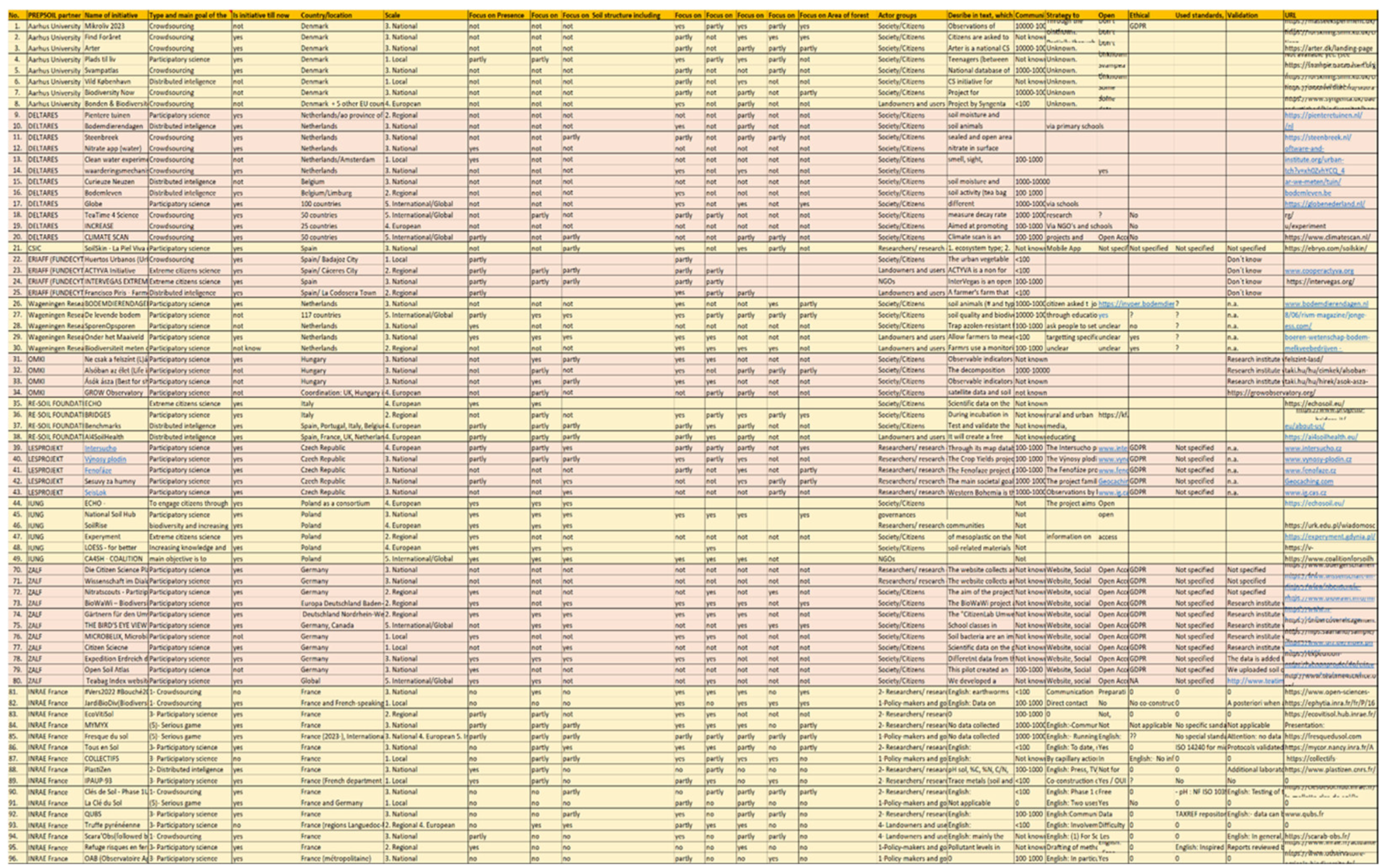

2.4. Collection and Analysis of Existing Citizen Science Initiatives

Prepsoil partners across various European countries compiled a citizen science (CS) initiative database. This database, provided in the Annex to this manuscript, contains 96 initiatives focusing on soil and land-use monitoring. The following steps summarize the process:

Figure 1.

Collected Citizens Science Database.

Figure 1.

Collected Citizens Science Database.

Data gathering by Prepsoil partners: Each partner contributed information from their respective regions using a standardized questionnaire developed by the Prepsoil team (Annex). The questionnaire covered key aspects such as project status, geographic extent, soil parameters monitored, stakeholder engagement, data validation protocols, and open-access policies.

Quantitative analysis: Numerical data on variables including project scale (local, regional, national), community size, and monitored soil parameters (e.g., soil organic carbon, nutrient levels, pollutants) were compiled and analysed using descriptive statistical methods. Frequency tables and cross-tabulations were generated to reveal trends and recurring patterns [

29].

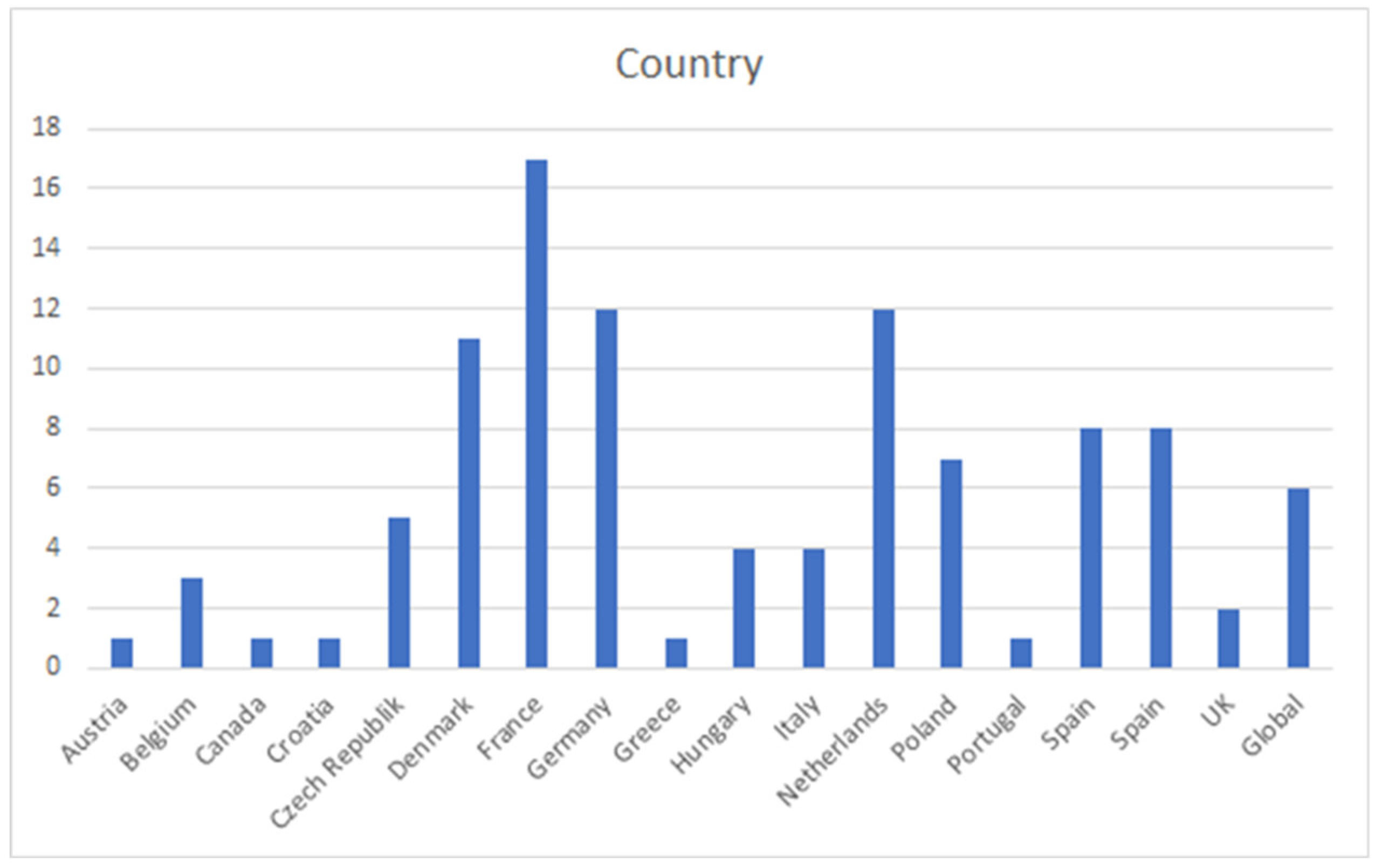

Figure 2.

Distribution of Citizen Science (CS) initiatives geographically.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Citizen Science (CS) initiatives geographically.

Figure 3.

Graph with the scale of Citizen Science initiatives.

Figure 3.

Graph with the scale of Citizen Science initiatives.

Qualitative analysis: Accompanying methodological descriptions and project narratives were analyzed using thematic coding to identify best practices, challenges, and potential biases. Follow-up inquiries clarified ambiguous entries. Initiatives demonstrating innovative methods - such as remote sensing integration or AI-based validation - were highlighted [

30].

2.5. Questionnaire Surveys and Living Lab Workshops

To complement the database compilation, questionnaire surveys, and workshops were conducted with five Living Labs (LLs):

Participant recruitment: LLs were selected based on thematic relevance (soil health, land use) and proven engagement in citizen science, aiming for broad geographical coverage. Workshop participants included scientists, farmers, extension officers, and municipal representatives [

31].

Questionnaire design: The survey instruments collected participants’ views on diverse soil monitoring methods, data quality considerations, and issues regarding technology uptake. Open-ended questions solicited feedback on desired improvements, such as advanced sensor integration or coupling in situ measurements with remote sensing data.

Workshop format and data collection: Workshops took place in person or via online platforms (Zoom, Teams), depending on LL preferences. Discussions were transcribed and subjected to qualitative coding to extract key thematic elements, including participant motivation, perceived limitations of existing monitoring programs, and ethical implications. Data handling procedures ensured the anonymity of respondents.

Ethical approval: As workshops did not gather sensitive personal information, no specific ethics committee approval was required beyond standard institutional protocols. Participants provided informed consent, and all data were anonymized in compliance with institutional and European data protection rules.

2.6. Data Management and Accessibility

All datasets, including the curated database of citizen science initiatives and questionnaire results, have been archived in a Prepsoil consortium repository. Publicly accessible files are provided under an open license, supporting reuse by researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders. Any sensitive or confidential data (as indicated by participants) remains password-protected and available upon request. Analytical scripts and codebases are version-controlled using Git-based repositories (e.g., GitLab), facilitating reproducibility.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive statistics (mean, median, frequencies) were used to describe project attributes and respondent viewpoints. Where pertinent, categorical data were compared using chi-square tests to assess associations between variables such as participant engagement and data reliability. Additionally, multivariate procedures, including principal component analysis, were employed to examine relationships in complex datasets, such as correlations between soil indicators and land-use factors. All statistical operations were performed using R software (version 4.2.0), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

This study did not involve any interventional or biomedical research on human or animal subjects. The questionnaire surveys and Living Lab workshops were designed to collect anonymous feedback related to soil monitoring practices and stakeholder perspectives. No personally identifiable or sensitive data were collected.

All participants were clearly informed of the voluntary nature of the study, their right to withdraw at any time without explanation, and the purpose for which their responses would be used. Informed consent was obtained verbally, and all data were anonymized prior to analysis.

As a result, the study did not require formal approval from an ethics committee, in line with European and institutional research ethics guidelines. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union [

32], and confidentiality was strictly maintained. Any data usage restrictions are detailed in the Data Management Plan.

3. Results

This section consolidates the findings derived from the methodological steps outlined in Materials and Methods. It integrates insights from the literature review, the assessment of European initiatives, an inventory of citizen science applications, a database of 96 documented projects compiled by Prepsoil partners, and questionnaire surveys and workshops conducted with Living Labs. Each subsection presents empirical observations, key patterns, and preliminary conclusions regarding the role of citizen science in soil monitoring and protection.

3.1. Literature Review Findings

A broad range of scientific studies underscores the growing relevance of citizen science in addressing priority soil issues such as erosion, pollution (e.g., heavy metals, pesticides, microplastics), depletion of organic matter, salinization, nutrient imbalances, and declining soil biodiversity [

1,

2]. Multiple authors confirm that volunteer-based monitoring significantly expands traditional surveillance systems’ spatial reach and temporal coverage, thereby strengthening efforts to identify and remediate these soil threats [

9,

29].

Among the widely cited initiatives are LandSense, which leverages remote sensing and volunteer inputs to track land-use changes across Europe [

23], and LUCAS, an EU-wide framework that integrates citizen-collected photographs with professional field measurements for surveying soil properties such as sealing and nutrient levels. [

24]. Platforms like Geo-Wiki facilitate crowd-validated land-cover classifications, enhancing the accuracy of digital soil maps and enabling the early detection of emergent problems, including deforestation and overgrazing [

13,

33,

34]. The FotoQuest Go project employs gamification to gather georeferenced soil and land-use observations. It renders it accessible to non-experts while supplying in situ ground-truth data to refine agricultural land-cover products [

26,

35]. Applications like iNaturalist provide ecological context (e.g., vegetation cover, habitat type) that can indirectly inform soil health assessments by understanding local biodiversity patterns [

27,

36,

37]. Additionally, the ECHO project merges crowdsourced soil data with sensor networks, demonstrating how citizen-science-driven insights can complement automated monitoring infrastructures to support real-time decision-making [

38,

39].

Key observations and challenges

Erosion and pollution: Citizen observations of gullies, soil colour changes, or pollutant indicators help identify hotspots for immediate intervention. Low-cost test kits used by volunteers can reveal nitrate exceedances, heavy metal deposits, or salinity spikes, insights that might otherwise remain undetected [

9,

35].

Organic matter depletion: Projects focusing on soil organic carbon, such as Geo-Wiki expansions and FotoQuest Go modules, supply crucial data in regions where soil fertility is threatened by overuse or climate change [

10,

13,

26].

Soil biodiversity: Although fewer in number, biodiversity-oriented initiatives like iNaturalist’s “soil organisms” category and specialized fungal or invertebrate mapping apps address the critical ecological dimension of soil health [

27,

37]. Research increasingly ties species richness below ground to improved nutrient cycling and carbon storage [

36,

40].

Data quality and validation: Disparities in volunteer skill sets and sampling procedures remain a significant challenge. However, structured guidelines and feedback loops - often aided by remote sensing cross-checks - have effectively reduced observer bias and ensured data reliability [

9,

15,

29].

Stakeholder engagement and policy uptake: Studies highlight greater volunteer participation in programs that provide tangible benefits, such as local training, social recognition, or direct policy influence (e.g., adjusting fertilizer regulations, designating conservation zones) [

35,

41]. Collaborative governance models, including Living Labs, further increase impact by embedding citizen science data within institutional decision-making processes [

31,

42].

The literature affirms that citizen science significantly expands soil monitoring across diverse land uses, engages the public in scientific discovery, and can steer policymaking toward more holistic resource management. Nevertheless, establishing consistent methodological frameworks, providing robust training, and developing clear standards for data integration - particularly with remote sensing outputs - are essential to ensure that volunteer-collected data effectively address priority soil concerns. By heeding these insights, future initiatives can bolster data completeness, enrich volunteer experiences, and enhance the long-term viability of community-driven soil monitoring.

3.2. Analysis of European Initiatives

Examining selected EU-funded and national-level projects demonstrates that citizen-driven soil monitoring is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of integrated environmental management. LandSense, LUCAS, and ECHO - frequently cited in academic and policy documents - illustrate how volunteer-based approaches can operate alongside institutional programs to expand data collection and encourage local engagement [

23,

24,

38]. These efforts extend well beyond data gathering, as many integrate educational or community-building objectives that strengthen social cohesion and facilitate sustainable land-use strategies.

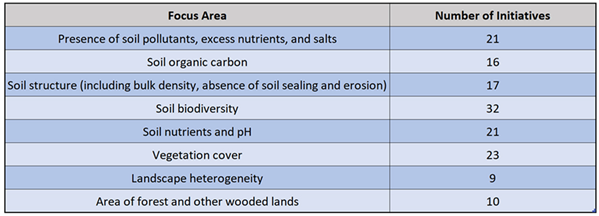

Table 1 presents an overview of the core attributes of these prominent initiatives, including their geographic coverage, monitored soil parameters, and methodological approaches or protocols they employ. While each project adopts different data-collection techniques - ranging from sensor networks to photo-based field surveys - community participation remains a shared priority. Notable benefits include real-time detection of soil-related threats, evidence-based influence on policy decisions, and enhanced stewardship among participants. However, a recurrent challenge lies in the absence of standardized guidelines for volunteer training and data validation across Europe. Findings suggest that efforts to harmonize such protocols at an EU level could substantially improve data interoperability among diverse soil datasets.

Table 1.

Focus areas of the Citizen Science initiatives.

Table 1.

Focus areas of the Citizen Science initiatives.

Broader studies further underscore the importance of these models, indicating that when local authorities, research institutes, and citizen groups collaborate, they can detect environmental hazards more efficiently and implement corrective measures [

29,

31,

35,

42]. Nonetheless, as indicated in published literature and stakeholder feedback, the lack of harmonized volunteer training guidelines and robust validation frameworks remains a pressing concern. Addressing these shortcomings through unified EU-level standards and transparent data governance could strengthen citizen-generated soil data’s reliability and policy utility, ultimately advancing holistic environmental management across Europe.

3.3. Inventory of Citizen Science Applications

A review of citizen science tools reveals a growing ecosystem of mobile and web-based applications pertinent to soil monitoring and land-use mapping. While platforms like

iNaturalist and

Pl@ntNet emphasize biodiversity data, they also contribute contextual information (e.g., vegetation cover and habitat type) that indirectly supports soil assessments by clarifying ecological conditions [

27,

28]. Other applications

- FotoQuest Go,

Geo-Wiki, and region-specific tools such as

Curieuze Neuzen (Flanders) or

Maaiveld (Netherlands) - demonstrate that user-friendly interfaces, gamification, and incentive mechanisms can boost volunteer engagement. However, datasets often vary widely in quality due to differences in participant skill levels and data validation procedures [

15,

26,

34,

43].

Key Observations from the App Inventory

Open Data principles: Most leading applications, including FotoQuest Go and iNaturalist, adhere to open data policies, which facilitate collaboration with scientific and policy stakeholders [

26,

27]. This openness allows researchers to merge citizen-collected observations with official datasets or Earth observation outputs, creating more comprehensive and timely depictions of soil and land-use conditions.

Real-Time Feedback: Many platforms provide immediate or near-immediate feedback to volunteers through automated classification algorithms (e.g., AI-based species identification in iNaturalist or Pl@ntNet) or peer-review systems [

27,

28]. While this rapid feedback can sustain volunteer motivation, robust backend validation frameworks are necessary to ensure data accuracy.

The balance between accessibility and rigour: Applications like

Geo-Wiki and

Curieuze Neuzen exemplify how easy data submission processes can encourage broader participation, yet they also illustrate the complexity of ensuring high data standards [

43,

44]. Some tools integrate advanced quality-assurance measures, such as cross-checking user entries with sensor data or established land-cover databases. In contrast, others rely on manual reviews by subject-matter experts or community members, which can be labour-intensive.

Regional specialization: Certain apps, such as Maaiveld in the Netherlands, specifically cater to local environmental conditions, policies, and data-sharing networks [

45]. This regional focus can generate highly detailed datasets but may limit interoperability if metadata standards are not aligned with broader European or global frameworks.

Overall, these findings highlight the diverse technological landscape supporting citizen-driven soil and land monitoring. The prevalence of open data principles underscores a shift toward collaborative research, yet the variety in verification approaches indicates that data quality remains a critical concern. Future innovations - such as further integration of AI verification, expanded user training modules, and standardized metadata protocols - could help achieve an effective balance between ease of participation and scientific rigor [

46,

47,

48].

3.4. Analysis of Existing Citizen Science Initiatives Database

Prepsoil partners assembled a database of 96 citizen science projects focused on soil health, spanning multiple European countries. These initiatives range from local efforts, such as community-led soil restoration campaigns in peri-urban zones, to transnational platforms coordinating data on soil organic carbon, nutrient levels, and erosion risk [

9,

26]. Many emphasize specific concerns - from industrial pollutants to agricultural intensification - yet collectively address various soil health parameters that align with evolving sustainability and climate objectives [

13,

48].

The database’s analysis suggests that

organic carbon,

pH, and

soil structure remain the most frequently monitored indicators, reflecting a widespread interest in carbon sequestration and overall soil fertility [

10,

15]. A smaller but growing subset of projects focuses on

soil biodiversity,

pollutant levels (e.g., heavy metals, microplastics), and

forest soil conditions, underscoring a recognition of soil’s multifaceted ecological significance. Projects implementing structured data validation - whether through

sensor cross-checking or

remote sensing integration - tend to report higher levels of stakeholder confidence, reinforcing the importance of methodological rigor [

9,

48]. Additionally,

feedback loops, in which volunteers receive consistent updates on how their contributions inform research or policy, have been strongly correlated with sustained participant engagement and data consistency [

13,

34].

3.5. Questionnaire Surveys and Living Lab Workshops

Questionnaire data and discussions from five Living Labs provide both quantitative snapshots and qualitative nuances regarding stakeholder perspectives on soil monitoring [

30,

31,

35]. In particular:

Quantitative trends: Approximately 70–80% of participants view

in situ measurements as a “gold standard,” but many express optimism about merging conventional practices with citizen science to close spatial or temporal gaps [

10,

15]. Nonetheless, around 45% express concerns about volunteer reliability, pointing to a need for clear guidelines in areas like

sampling consistency and

metadata documentation [

13,

48].

Qualitative insights:

Privacy,

data governance, and

volunteer motivation are central themes in workshop dialogues. Participants frequently stressed that high-performing projects adopt systematic validation steps - such as side-by-side comparisons with expert measurements - and immediate channels for acknowledging or correcting inaccuracies in volunteer submissions [

9,

30]. Ethical considerations, including

respect for landowner rights and

transparent data use, were highlighted as critical for fostering long-term, trust-based collaborations [

32,

35].

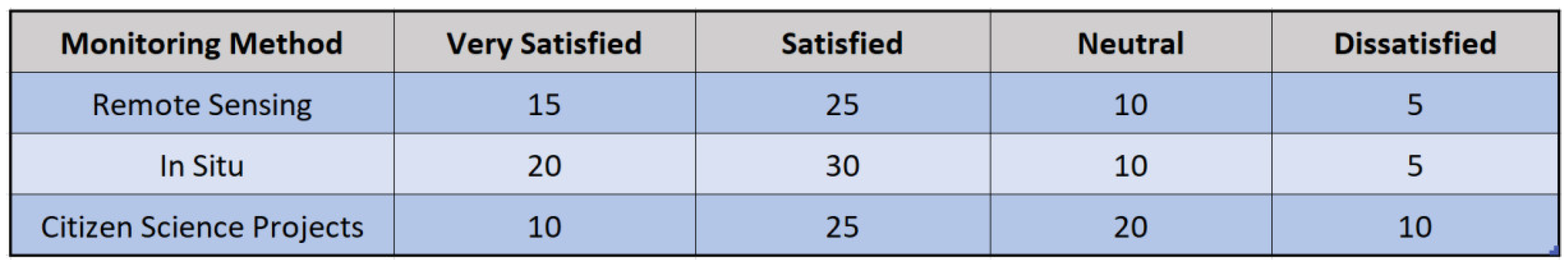

Table 2 synthesizes indicators collected from these workshops, emphasizing the strong demand for validated data and an increasing reliance on

remote sensing to supplement community-driven field observations. This aligns with broader trends in citizen science, where technology-enabled cross-checking can raise confidence in volunteer-contributed datasets and enhance their applicability to policy and management decisions [

39,

48].

Table 2.

Key European initiatives.

Table 2.

Key European initiatives.

| Initiative |

Geographic scope |

Main soil parameters |

Key methods and protocols |

References |

| LandSense |

Pan-European |

Land cover/use, soil organic carbon, sealing, etc. |

Integration of remote sensing with volunteer-based inputs; community outreach and education. |

[5,17] |

| LUCAS |

EU-wide |

Soil sealing, nutrients, structure, biodiversity |

Field surveys, photo quests, and satellite validation to refine existing soil databases. |

[6,18] |

| ECHO |

Multi-country (EU) |

Organic carbon, pH, soil moisture, etc. |

Sensor networks, crowdsourcing, synergy with remote sensing technologies, real-time feedback. |

[12,22] |

Figure 6.

Respondents’ satisfaction with existing methods of soil monitoring.

Figure 6.

Respondents’ satisfaction with existing methods of soil monitoring.

3.6. Additional Observations

Several overarching themes emerged from the database review and Living Lab discussions. The first is the call for

standardizing metadata, ensuring that heterogeneous data sources - spanning smartphone applications, remote sensing outputs, and sensor arrays - can be harmonized effectively for comparative analysis [

31,

39,

48]. The second theme is the recognized importance of

long-term engagement strategies, including volunteer training sessions, gamification features, and social recognition, all of which help maintain data quality over time [

13,

30,

35]. Lastly,

multi-stakeholder collaboration—involving NGOs, municipal authorities, research institutions, and citizen groups—consistently emerges as vital for building trust, aligning project objectives, and integrating results into policy frameworks [

9,

10].

These observations align with broader findings in the literature, highlighting how citizen-driven approaches can generate essential soil data while simultaneously fostering environmental awareness, public accountability, and community empowerment [

31,

39]. They also indicate a suite of best practices - such as open data principles, iterative volunteer training, and technology-based validation - that collectively enhance both scientific robustness and societal engagement [

26,

48].

3.7. Preliminary Conclusions from Results

Taken together, these findings underscore the

substantial potential of citizen science to enhance soil monitoring efforts, particularly by extending spatial and temporal coverage, while also boosting community engagement in environmental stewardship [

10,

13,

31]. Integrating volunteer observations with established scientific methods, such as

remote sensing,

sensor arrays, and

expert validation, can mitigate common data quality concerns and elevate the overall reliability of collected information [

9,

48]. Nevertheless, the results reveal persistent challenges, including the lack of

harmonized protocols, the risk of

volunteer attrition, and

uneven digital literacy across different regions [

26,

30].

The subsequent sections delve into these barriers in greater detail, framing the study’s observations within established soil-monitoring frameworks and proposing pragmatic recommendations for

policymakers,

practitioners, and

community leaders seeking to expand or refine citizen science initiatives in soil health [

1,

39]. By addressing these constraints systematically, stakeholders can further harness the strengths of citizen-driven data collection, ultimately contributing to more robust, inclusive, and actionable soil-monitoring practices.

4. Discussion

The findings presented in this study highlight both the opportunities and complexities of using citizen science for soil monitoring. They build on a growing body of literature demonstrating that volunteer-based data collection can significantly augment spatial and temporal coverage, enhance public engagement, and inform policy decisions at multiple governance levels [

13,

31,

48]. The diversity of soil health indicators - ranging from organic carbon and nutrient levels to biodiversity and pollutant concentrations - emphasizes the multifaceted nature of soil management and underscores the need for adaptable yet robust monitoring frameworks [

9,

26].

4.1. Interpretation of Findings in the Context of Prior Research

Many of our observations echo earlier studies showing that

in situ measurements, combined with remote sensing outputs and sensor networks, can create powerful synergies, mainly when volunteers receive structured training and rapid feedback on data quality [

10,

30]. This integration is crucial for addressing persistent data gaps in under-monitored regions - such as peri-urban or high-biodiversity areas - where official surveillance alone may be logistically challenging or cost-intensive [

27,

35]. Moreover, evidence from the Living Lab workshops aligns with existing scholarship, suggesting that long-term volunteer retention is tied to transparent communication, social recognition, and perceived impact on policy or management outcomes [

13,

15,

31].

While most citizen science initiatives in the compiled database demonstrate open data sharing - often supported by user-friendly digital platforms - significant variability remains in validation processes [

9,

48]. Some rely on manual cross-checking by domain experts, whereas others employ more advanced, AI-driven error detection or sensor-based verification. This variance can lead to inconsistencies in data reliability, underscoring the need for harmonized protocols, shared metadata standards, and iterative training programs [

26,

39]. These findings reinforce existing calls in the literature for more uniform quality-control frameworks to ensure that citizen-collected observations meet scientific and policymaking requirements [

36,

39].

4.2. Implications for Soil Monitoring Frameworks and Policy

Aligned with the Mission “A Soil Deal for Europe” and other EU-level environmental strategies, our results are timely, reaffirming the potential of

community-driven observation to fill critical knowledge gaps and accelerate the shift toward sustainable land use. Projects such as LandSense and LUCAS illustrate how remote sensing, user-friendly mobile apps, and professional field surveys can be integrated to generate comprehensive datasets that support targeted interventions - like erosion control and nutrient management [

23,

24]. Moreover, the involvement of diverse stakeholders (researchers, local landowners, farmers, and NGOs) fosters a shared sense of ownership, which is crucial for translating data-driven insights into meaningful changes on the ground [

13,

35].

However, our analysis also spotlights critical bottlenecks. Uneven digital literacy, volunteer attrition, and insufficient documentation of stakeholder engagement mechanisms may hinder the scalability of specific initiatives [

26,

31]. The broader policy landscape could benefit from guidelines that incentivize open data practices, facilitate capacity-building (e.g., training modules for volunteers and local coordinators), and offer financial or institutional support for long-term project maintenance [

30,

48]. By aligning these strategies with the broader goals of the European Soil Observatory (EUSO) and national-level soil missions, citizen science can serve not only as a data-gathering tool but also as a catalyst for societal commitment to soil health [

1,

49].

4.3. Methodological Considerations and Challenges

From a methodological perspective, the diversity of soil parameters, participant backgrounds, and data-collection protocols presents a challenge to cross-initiative comparisons and meta-analyses [

9,

10]. Projects implementing standardized quality checks - such as side-by-side expert measurements, sensor cross-referencing, or remote sensing overlays - tend to earn higher stakeholder trust and produce more consistent outputs [

26,

27,

48]. Consequently, adopting unified metadata structures, interoperable data formats, and open-source geospatial tools can enhance interoperability, reduce duplication, and promote broader data reuse [

36,

39].

Ethical and privacy concerns were frequently emphasized in workshops, echoing current discussions around General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliance and landowner consent [

15,

35]. As citizen science platforms increasingly integrate AI-driven validation methods, ensuring transparency and fairness in algorithmic decision-making becomes equally critical. This underscores the growing need for ethicists and legal experts to play an active role in project design and oversight [

30,

31].

4.4. Future Research Directions

Longitudinal studies: Long-term tracking of volunteer motivations, retention rates, and data quality trends could yield more profound insights into sustaining citizen science initiatives over multiple growing seasons or across varied climatic zones [

13,

39].

AI and sensor fusion: Further exploration of how machine learning algorithms can intelligently filter or cross-check volunteer submissions would sharpen data reliability. Integrating UAV-based spectral imagery with ground observations could reveal novel indicators, such as linking soil biodiversity to aboveground vegetation indices [

26,

36].

Socioeconomic impact: Expanding beyond ecological metrics, future work could investigate how citizen-collected soil data influences local economies and land management decisions, evaluating metrics such as farm profitability, ecosystem services valuation, and rural community development [

13,

31].

Comparative policy analysis: A systematic review of how different EU member states incorporate citizen science data into legislative or regulatory frameworks would help identify best practices, highlight regulatory gaps, and guide further policy harmonization [

9,

48].

In sum, this study not only reaffirms that citizen science can enrich and democratize soil monitoring efforts but also underscores the ongoing need for robust validation, participant support, and policy-level integration to realize its full potential. By leveraging open data principles, advanced remote sensing technologies, and collaborative governance models, future research and practice can better align volunteer-driven data collection with the overarching mission of preserving and restoring Europe’s soil health.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that citizen science can serve as a valuable asset for expanding the spatial and temporal scale of soil monitoring, enhancing data richness, and fostering community engagement in environmental stewardship. By integrating volunteer observations with established scientific tools - such as remote sensing, sensor arrays, and expert validation - citizen-collected data can generate policy-relevant insights into soil health indicators, including organic carbon content, pollutant levels, biodiversity, and nutrient balance. This integrative approach aligns with broader environmental directives, such as the EU’s Soil Mission, which emphasizes restoring and protecting soils as a critical resource for climate resilience, food security, and biodiversity conservation.

While the potential of citizen-led soil monitoring is considerable, our findings emphasize several enduring challenges. Projects vary in data validation rigor and stakeholder engagement, with some relying on comprehensive training, iterative feedback loops, and advanced technologies (e.g., AI-based verification), while others rely on ad hoc methodologies that may produce inconsistent or difficult-to-compare datasets. Furthermore, workshop participants and database analyses point to issues like volunteer attrition, privacy concerns, and uneven digital literacy, which can limit scalability. Addressing these gaps requires standardized protocols, sustained capacity-building efforts, transparent data governance, and strong partnerships between governmental bodies, academic institutions, and local communities.

In conclusion, well-structured citizen science initiatives can enhance soil health monitoring, not only by generating complementary data but also by cultivating public awareness and accountability. Future efforts should focus on harmonizing protocols, ensuring long-term volunteer support, and leveraging advancements in remote sensing and AI technologies to enhance data quality and applicability further. By integrating these elements in a participatory and ethically sound manner, citizen science can contribute to a more inclusive and scientifically rigorous foundation for sustainable soil management across diverse landscapes.

Author Contributions

The research was designed by Karel Charvát, Jaroslav Šmejkal and Pierre Renault; Karel Charvát, Jaroslav Šmejkal and Petr Horák performed the research; Data analysis was performed by Karel Charvát, Jaroslav Šmejkal, Petr Horák and Pierre Renault; Text writing, editing and translation was carried out by Karel Charvát, Jaroslav Šmejkal, Pierre Renault, Markéta Kollerová and Šárka Horáková. All authors have read and agreed on the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Work is also contributed with support from the EU projects: - PREPSOIL – Preparing the European Mission towards healthy soils (Grant agreement ID: 101070045);’ - PoliRuralPlus – Fostering Sustainable, Balanced, Equitable, Place-based and Inclusive Development of Rural-Urban Communities’ Using Specific Spatial Enhanced Attractiveness Mapping ToolBox (Grant agreement ID: 101136910);’ Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in the section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given that is not covered by the author’s contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open-access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| CCSS |

Czech Center for Science and Society |

| CORDIS |

Community Research and Development Information Service |

| CS |

Citizen Science |

| DOAJ |

Directory of Open Access Journals |

| EU |

European Union |

| EUSO |

European Soil Observatory |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| INRAE |

French National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment |

| LESP |

Lesprojekt - služby s.r.o. |

| LL |

Living Lab |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

References

- Lal, R. (2004). Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science, 304, 1623–1627. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2015). Status of the World’s Soil Resources. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy. https://www.fao.org/3/i5199e/i5199e.pdf.

- European Environment Agency. (2016). Soil Degradation in Europe. EEA Report: Copenhagen, Denmark. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/soil-degradation-in-europe.

- Houllier, F., Joly, P.B., & Merilhou-Goudard, J.B. (2017). Citizen sciences: A dynamics to be encouraged. Natures Sciences Sociétés, 25, 418–423. [CrossRef]

- Odenwald, S.F. (2020). A citation study of earth science projects in citizen science. PLoS One, 15, e0235265. [CrossRef]

- Bedessem, B., Julliard, R., & Montuschi, E. (2021). Measuring epistemic success of a biodiversity citizen science program: A citation study. PLoS One, 16, e0258350. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, M., & Li, X. (2015). Ancient Phenological Observations in East Asia: Early Citizen Science Practices in China and Japan. International Journal of Climatology, 30, 210–225. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.B., Shirk, J., & Zuckerberg, B. (2014). The invisible prevalence of citizen science in global research: migratory birds and climate change. PLoS One, 9, e106508. [CrossRef]

- Head, J.S., Crockatt, M.E., Didarali, Z., Woodward, M.J., & Emmett, B.A. (2020). The role of citizen science in meeting SDG targets around soil health. Sustainability, 12, 10254. [CrossRef]

- Mason, E., Gascuel-Odoux, C., Aldrian, U., Sun, H., Miloczki, J., Götzinger, S., & Sandén, T. (2024). Participatory soil citizen science: An unexploited resource for European soil research. European Journal of Soil Science, 75, e13470. [CrossRef]

- SciStarter. Available online: https://scistarter.org (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Zooniverse. Available online: https://www.zooniverse.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Fritz, S., McCallum, I., Schill, C., Perger, C., Grillmayer, R., Achard, F., & Obersteiner, M. (2009). Geo-Wiki.Org: The use of crowdsourcing to improve global land cover. Remote Sensing, 1, 345–354. [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, D.G., Liu, J., Carlisle, S., & Zhu, A.X. (2015). Can citizen science assist digital soil mapping? Geoderma, 259–260, 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Kosmala, M., Wiggins, A., Swanson, A., & Simmons, B. (2016). Assessing data quality in citizen science. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14, 551–560. [CrossRef]

- Mäkipää, J.P., Dang, D., Mäenpää, T., & Pasanen, T. (2020). Citizen science in information systems research: evidence from a systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Honolulu, HI, USA, 13–16 January 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B., & Charters, S. (2007). Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. Technical Report, EBSE 2007-001. https://www.cs.auckland.ac.nz/~norsaremah/2007%20Guidelines%20for%20performing%20SLR%20in%20SE%20v2.3.pdf.

- Okoli, C. (2015). A guide to conducting a systematic literature review of information systems research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 37, 879–910. [CrossRef]

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review (1st ed.). Sage Publications.

- Pullin, A.S., & Stewart, G.B. (2006). Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology, 20(6), 1647–1656. [CrossRef]

- CORDIS. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- LandSense. Available online: https://landsense.eu (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- European Commission. LUCAS – Land Use/Cover Area Frame Survey. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/lucas (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Wiggins, A., & Crowston, K. (2012). Goals and tasks: Two typologies of citizen science projects. In Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 12–15 January 2012; IEEE, pp. 3426–3435. [CrossRef]

- FotoQuest Go. Available online: https://iiasa.ac.at/models-tools-data/fotoquest-go (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- iNaturalist. Available online: https://www.inaturalist.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Pl@ntNet. Available online: https://identify.plantnet.org/cs (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Dickinson, J.L., Zuckerberg, B., & Bonter, D.N. (2010). Citizen science as an ecological research tool: Challenges and benefits. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 41, 149–172. [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M., & Namey, E.E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis (1st ed.). Sage Publications.

- Makkonen, M. (2014). A Living Lab Approach for User-Driven Innovation: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 1, 13. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, P., & Von dem Bussche, A. (2017). The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): A Practical Guide. Springer: New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, S., McCallum, I., Schill, C., Perger, C., See, L., Schepaschenko, D., & Obersteiner, M. (2012). Geo-Wiki: An online platform for improving global land cover. Environmental Modelling & Software, 31, 110–123. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, S., & Fraisl, D. (2018). Citizen science data in peer-reviewed publications: The Geo-Wiki experience. In Press.

- Bonney, R., Shirk, J.L., Phillips, T.B., Wiggins, A., Ballard, H.L., Miller-Rushing, A.J., & Parrish, J.K. (2014). Next steps for citizen science. Science, 343(6178), 1436–1437. [CrossRef]

- Havens, K., & Henderson, S. (2013). Citizen science takes root. American Scientist, 101(5), 378. [CrossRef]

- Charvát, K., & Kepka, M. (2021). Crowdsourced Data. In Big Data in Bioeconomy: Results from the European DataBio Project (pp. 63–67).

- ECHO Project. Available online: https://echo.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Leibovici, D.G., Santos, R., Hobona, G., Anand, S., Kamau, K., Charvat, K., et al. (2023). Geospatial standards. In The Routledge Handbook of Geospatial Technologies and Society. Routledge: New York, NY, USA.

- van der Heijden, M.G.A., Bardgett, R.D., & van Straalen, N.M. (2008). The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecology Letters, 11(3), 296–310. [CrossRef]

- Haklay, M., & Weber, P. (2008). OpenStreetMap: User-generated street maps. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 7(4), 12–18. [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S., Westerlund, M., & Rose, R. (2012). Living Labs as open innovation networks. Technology Innovation Management Review, 2(9), 6–9. [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, D., & Heylen, K. (2017). Citizen science in Flanders: Curieuze Neuzen as a case study. Journal of Citizen Engagement, 5, 45–60.

- Fritz, S., McCallum, I., Schill, C., Perger, C., Grillmayer, R., Achard, F., et al. (2009). Geo-Wiki.Org: The use of crowdsourcing to improve global land cover. Remote Sensing, 1(3), 345–354. [CrossRef]

- Maaiveld. Available online: https://maaiveld.nl (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Suomela, T., & Johns, E. (2012). Citizen Participation in the Biological Sciences: A Literature Review of Citizen Science; Unpublished.

- Cooper, C.B., Shirk, J., & Zuckerberg, B. (2014). The invisible prevalence of citizen science in global research. PLoS One, 9(9), e106508. [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.M., & Buckles, D.J. (2019). Participatory action research: Theory and methods for engaged inquiry (1st ed.). Routledge: New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- European Soil Observatory (EUSO). Available online: https://www.euso.eu (accessed on 1 January 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).