1. Introduction

Heavy metal contamination in aquatic environments poses a significant threat to biodiversity and ecosystem health, resulting from both anthropogenic activities and natural processes. Prominent heavy metals found in water include cadmium, chromium, lead, mercury, and zinc, which can enter water bodies through industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, and urban waste. These contaminants are particularly concerning due to their persistent nature and ability to bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms, leading to detrimental effects on individual species and the broader ecological community [

1]. For instance, these metals bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms, causing reproductive failure, growth inhibition, and increased mortality rates, which ultimately destabilize food chains and reduce species diversity [

2]. Furthermore, the contamination of aquatic systems poses significant risks to human health, as heavy metals enter the food chain and drinking water supplies. Chronic exposure to lead is associated with neurological disorders and kidney damage, while cadmium can cause respiratory and gastrointestinal complications [

3]. Copper, though essential in trace amounts, becomes toxic at higher concentrations, leading to liver damage and anemia. The severity of these health effects depends on the type of metal, the level of exposure, and individual susceptibility. Therefore, addressing heavy metal pollution is essential to safeguard both ecological integrity and public health [

4].

Various industries, such as petrochemical, paint, tanning, textile manufacturing, healthcare, and fertilizer production, are significant contributors to heavy metal pollution [

5] In the oil extraction sector, wastewater is particularly concerning, as it contains elevated concentrations of heavy metals like lead, cadmium, chromium, and nickel, alongside organic and inorganic pollutants [

6]. These contaminants are present in concentrations ranging from micrograms per liter (µg/L) to milligrams per liter (mg/L), depending on the source and processing methods, posing substantial risks to both environmental and human health [

6,

7]. Consequently, the oil industry, a major contributor to soil, water, and air pollution, necessitates effective wastewater treatment solutions. Conventional methods such as physical filtration, adsorption, chemical precipitation, oxidation, and coagulation have been widely employed [

7]. However, biological techniques, including biosorption and bio-removal, are gaining attention due to their environmental safety, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility for treating wastewater from municipal, agricultural, industrial, and petroleum sources [

8].

In recent years, biosorption and adsorption methods have emerged as promising solutions for removing heavy metal ions from industrial wastewater [

9,

10]. Plant waste materials, such as fruit peels and ground plant residues, are particularly advantageous due to their abundance, low cost, and high adsorption capacities [

9,

10]. For instance, dried lemon peels effectively adsorb lead and cadmium owing to their high cellulose and pectin content, while orange peels remove copper and zinc through ion exchange mechanisms [

11]. Banana peels, rich in carboxyl and hydroxyl functional groups, exhibit high adsorption capacities for chromium and nickel [

12], and pomegranate peels, with their porous structure and active binding sites, are effective in removing arsenic and mercury [

13]. These plant wastes, often unsuitable for animal feed and typically discarded through burning [

14], represent a sustainable resource for wastewater treatment. Recent studies have emphasized the potential of

Phragmites australis, commonly known as common reed, in the biosorption of heavy metals from wastewater. The plant's cellular structure and biochemical properties help it to effectively absorb contaminants such as lead, cadmium, and chromium, significantly reducing their concentrations in polluted water bodies. Its high phenotypic plasticity allows it to thrive in environments with fluctuating nutrient levels, a critical feature for maintaining its biosorption capacity across different conditions, making it a promising candidate for phytoremediation applications [

15,

16].

This study aims to optimize the use of Phragmites australis for the biosorption of heavy metal-contaminated wastewater. Key parameters such as temperature, pH, contact time, and biomass characteristics will be investigated to enhance biosorption efficiency and elucidate the underlying mechanisms. The ultimate goal is to develop a scalable and sustainable phytoremediation strategy for the treatment of industrial wastewater.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Plant Biosorbents

Phragmites australis (Common Reed) was collected from agricultural areas along the banks of the Euphrates Rivers (latitude 33.4292807″ N; longitude 43.2750694″ E). The collected biomass was meticulously cleaned, first with tap water to remove surface impurities, followed by rinsing with double-distilled water (DDW) to ensure purity. The cleaned biomass was then prepared for two distinct experimental setups. In the first one, the biomass was air-dried and cut into dried pieces of varying sizes. In the second, the biomass was dried, ground into powder, and sieved using stainless steel sieves to achieve particle sizes ranging from 0.106 mm to 2 mm. All prepared samples were stored in a dry environment to maintain their integrity for subsequent biosorption experiments.

2.2. Characterization of P. australis

The potentiometric titration technique was employed to determine the point of zero charge (pHpzc) of P. australis. To achieve this, a set of 0.1 M NaCl solutions was prepared in 100 mL flasks. The initial pH (pHᵢ) of each solution was adjusted between 1 and 11 using 0.1 M NaOH or 0.1 M HCl. The final volume in each flask was precisely set to 25 mL. Subsequently, 0.5 g of P. australis was introduced into each solution, followed by agitation at 150 rpm for 48 hours. After this period, the final pH (pHf) was recorded. The difference between initial and final pH values (ΔpH = pHᵢ – pHf) was plotted against pHᵢ, and the pHpzc was identified as the point where ΔpH = 0 on the x-axis. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Inspect S50, FEI Company, Netherlands) was used to investigate the surface morphology of both raw and metal-treated biomass. A mixed solution containing heavy metals (zinc, iron, manganese, lead, cadmium, and copper) at 100 ppm each was prepared and combined with 1 g of P. australis plant powder. The mixture was allowed to settle for two hours and then analyzed. Additionally, the functional groups responsible for metal uptake in untreated and treated biosorbents were examined using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. For this analysis, samples were dried, mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) at a 1:10 ratio, finely ground, and pressed into pellets. The KBr background was subtracted, and all spectra were plotted on the same absorbance scale.

2.3. Batch Biosorption Experiments

The biosorption process was studied using various analytical methods with a 100 mL working volume of metal solutions, each at a concentration of 100 mg L⁻¹ of Zinc (Zn²⁺), Cadmium (Cd²⁺), Iron (Fe²⁺), Lead (Pb²⁺), Copper (Cu²⁺), and Manganese (Mn²⁺). These solutions were placed in 250 mL volumetric flasks. To optimize the experimental conditions, the first step was to assess the impact of the biosorbent form of

P. australis by comparing powdered and whole-piece dried biomass. 1 g of biosorbent was added to each flask (100 mL), and the mixtures were incubated for 60 minutes at 30°C and pH 7, with a constant agitation speed of 150 rpm. The pH solution pH was carefully adjusted and maintained using 0.1 M NaOH or 0.1 M HCl. To further refine the biosorption process, the effects of key operational parameters were examined, including pH (3–8), temperature (30°C) for control conditions, and 20–60°C for experimental variations, contact time (5–120 min), controlled biomass particle sizes (0.106, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 mm) to systematically evaluate the impact of particle size on adsorption efficiency, and biosorbent weight (1–20 g/L). The initial adsorbate concentration was fixed at 10 g/L. The most favorable pH condition was then applied for further biosorption capacity study. Control solutions of Zn, Cd, Fe, Pb, Cu, and Mn (without

P. australis) were prepared under identical conditions to serve as reference samples. After biosorption, all samples underwent centrifugation at 5500 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by filtration through 0.45 µm filter paper, and metal concentrations were determined using Flame Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (FAAS). This procedure was consistently applied in subsequent experiments to identify the most effective biosorbent form for further applications. The biosorption efficiency of metal ions was calculated using Equation (1):

where C

i and C

f are the initial and final (or equilibrium) metal concentrations, respectively. To ensure the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of the results, all measurements were conducted in duplicate, and the average values were reported.

2.4. Adsorption Isotherm Models

To evaluate the adsorption behavior of heavy metal ions onto the biosorbent, the experimental data were fitted using the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models [

17]. These models provide insights into the adsorption capacity, surface characteristics, and adsorption mechanisms. The Langmuir model was employed to assess the adsorption capacity and evaluate the affinity of the adsorbent for metal ions. The nonlinear form of the Langmuir equation is given by:

where

KL and

qmax represent the Langmuir constants for adsorption energy and maximum adsorption capacity, respectively.

Ce is the equilibrium concentration of the metal ions in solution (mg/L), and

qe is the amount of metal ions adsorbed at equilibrium in (mg g

-1). The Langmuir parameters

qmax and

KL, were determined using Origin Software to assess adsorption quantitatively behavior [

17].

The Freundlich isotherm model, on the other hand, describes adsorption on a heterogeneous surface with multilayer adsorption, where adsorption sites have varying affinities for the adsorbate. The non-linear form of the Freundlich equation is expressed as:

where

Kf and

n are Freundlich constants, with

Kf representing the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent, and

n indicating the adsorption intensity. These constants were determined by fitting the experimental data to the non-linear form of the Freundlich isotherm equation using non-linear regression in Origin software. The data were plotted as

qe versus

Ce and the best-fit values for

Kf and

n were obtained. The strength of the fit was evaluated based on the R² value.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA statistical tests. Additionally, all experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure reliability and reproducibility and presented as mean ± standard error (S.E).

3. Results and Discussion

This study explored the influence of key variables, pH, temperature, retention time, controlled powder sizes and weight ratio, on the biosorption capacity of P. australis for the removal of heavy metals at a fixed initial concentration of 100 mg/L. Understanding the influence of these variables on the biosorption capacity of Common Reed is crucial for optimizing the maximum removal of heavy metals.

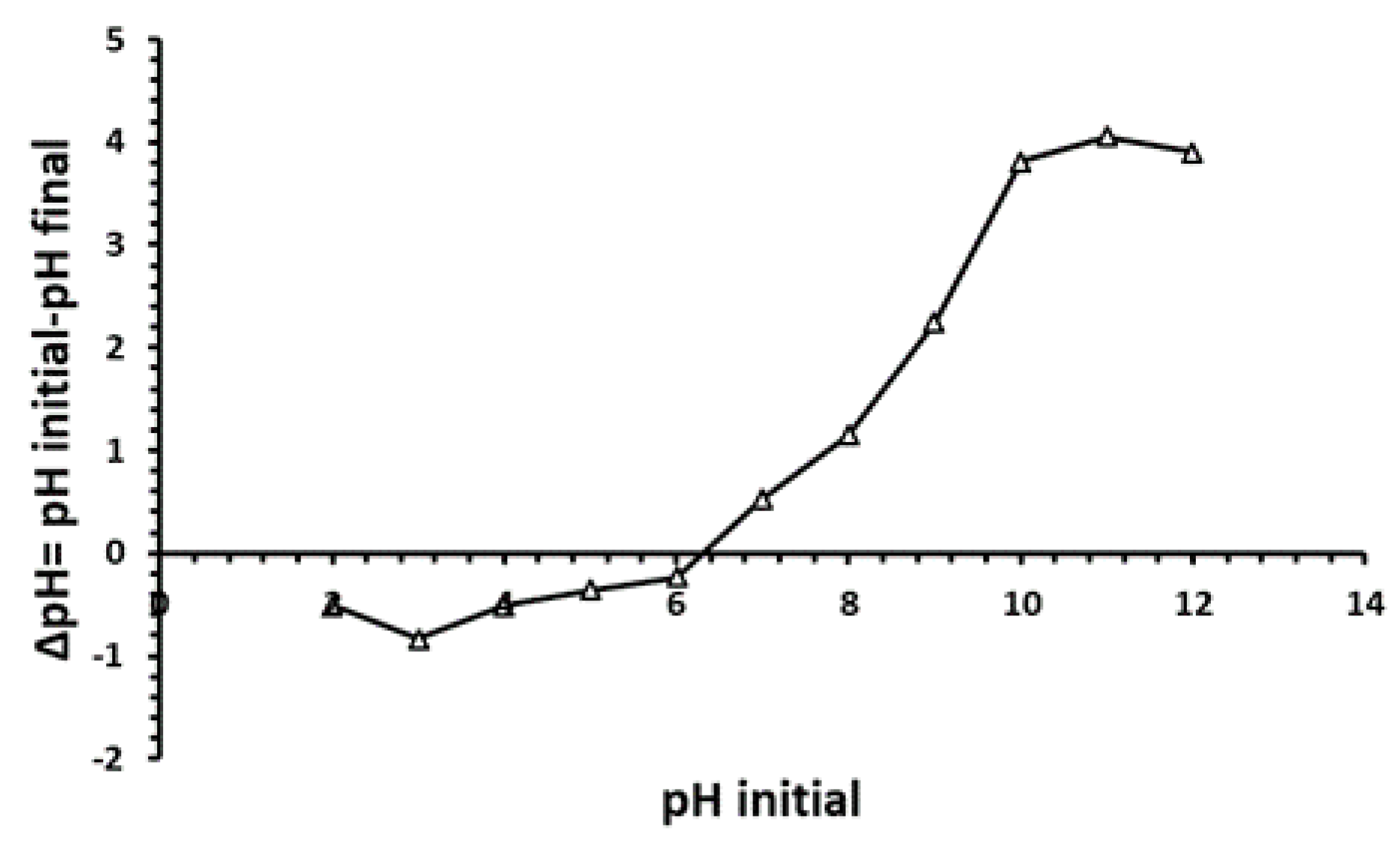

3.1. Determination of Point Zero Charge (pHpzc)

The point of zero charge (pHpzc) is a key parameter in biosorption studies, providing insights into the surface charge characteristics of a material and its adsorption behavior. In this study, the pHpzc of

P. australis biomass was determined to be 6.2 (

Figure 1), indicating a negatively charged surface at pH levels above 6.2 and a positive charge below this point. This finding is crucial, as it identifies the optimal pH range for heavy metal adsorption, which dependent on surface charge. Compared to other plant-based biosorbents,

P. australis exhibits a pHpzc similar to

Moringa oleifera bark reported as 6.0 [

18], while Yohimbe bark shows a slightly higher pHpzc of 7.1 [

19]. These findings underscore the importance of pHpzc as a key parameter in evaluating and optimizing biosorbent performance.

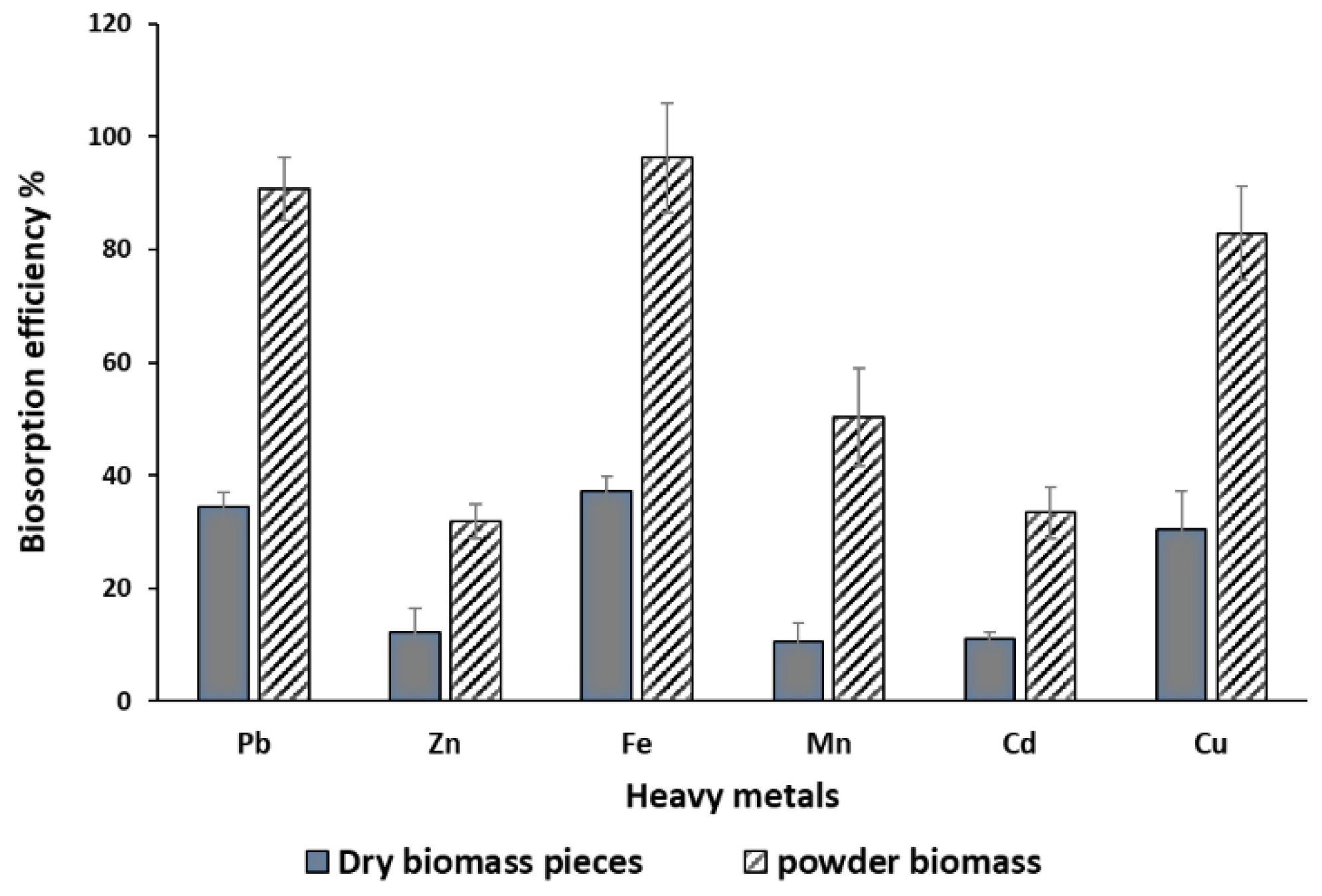

3.2. Effect of Biomass Physical Form

This study explores the influence of the physical form of

P. australis biomass, powdered versus non-powdered (dry pieces), on its efficacy in heavy metal biosorption. The experiment was conducted under controlled conditions, including a temperature of 30°C, pH 7, a retention time of 60 minutes, and a bio-sorbent weight of 10 g/L. The selection of pH 7 was chosen to ensure a net negative charge on the surface, thus enhancing its affinity for cationic heavy metal ions through electrostatic interactions. Initial findings highlight a marked increase in biosorption efficiency for powdered biomass compared to dry pieces (

Figure 2). Statistical analysis using ANOVA revealed highly significant differences (P < 0.0001) in biosorption capacity between the two biomass forms and across the examined heavy metals. Additionally, the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at P > 0.05 further validated these distinctions, with an LSD value of 2.678, underscoring the superior performance of powdered biomass in heavy metal removal. It was found that plant powder biomass had much better mean values than those recorded for dry biomass pieces as presented in

Figure 2. The biosorption efficiency of the powdered form followed the order: Fe > Pb > Cu > Mn > Cd > Zn, indicating distinct variations in binding affinity for different heavy metals. These findings suggest that the increased surface area and enhanced accessibility of active sites in the powdered form, combined with the favorable electrostatic interactions at pH 7, contribute to its improved biosorption performance.

3.3. Optimization of the Biosorption Parameters

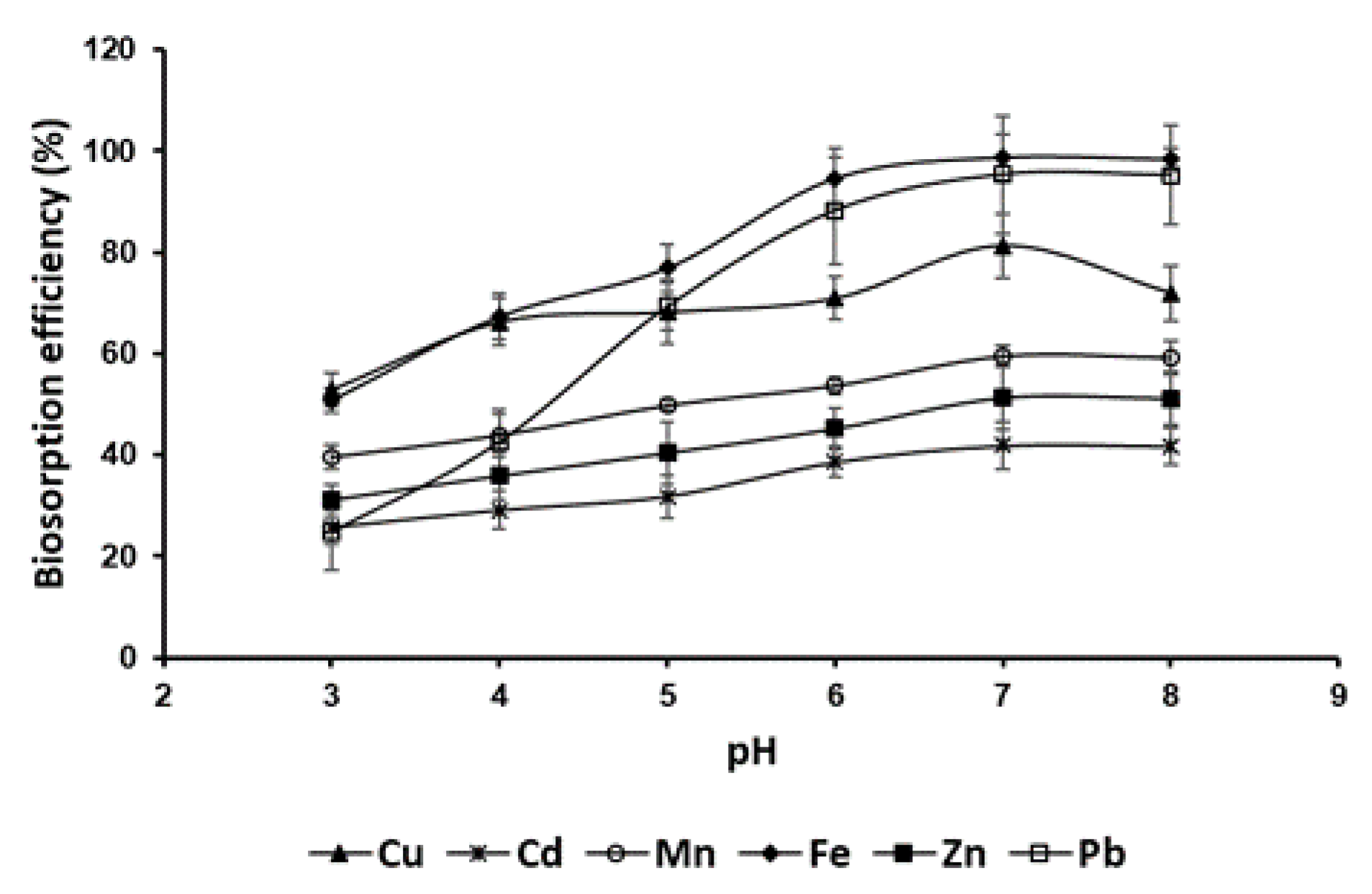

3.3.1. Effect of pH

The biosorption efficiency of

P. australis biomass for heavy metals (Cu, Cd, Mn, Fe, Zn, Pb) was strongly influenced by pH (

Figure 3) , with optimal performance observed at pH 7–8, just above the point of zero charge (pHpzc = 6.2). Statistical analysis (

P < 0.0001) confirmed significant differences in metal uptake based on pH. At pH values below the pHpzc (3–6), the biomass surface, which carries a positive charge, repelled metal cations, leading to reduced biosorption efficiency. As pH increased beyond the pHpzc (6–8), the biomass surface became negatively charged, enhancing electrostatic attraction and promoting greater metal ion uptake. Among the metals tested, Fe and Pb showed the highest biosorption efficiencies (over 95% at pH 7), likely due to their strong affinity for functional groups such as carboxyl and hydroxyl on the biomass surface. The observed decrease in biosorption efficiency at pH 8 for most metals may be attributed to minor precipitation effects. In contrast, Cd and Zn showed comparatively lower efficiencies, reaching about 42% and 51%, respectively, at pH 7, likely due to intrinsic differences in their binding affinities for the biomass. Interestingly, at pH 8, a slight decrease in biosorption efficiency was observed for most metals, possibly due to minor precipitation effects. These findings underscore the critical role of pH in modulating the surface charge of

P. australis biomass and its subsequent impact on biosorption efficiency, with pH 7 identified as the optimal condition for maximizing the removal of heavy metals. This is consistent with previous studies, such as Lesage et al. [

20], who reported that

P. australis achieves maximum biosorption of heavy metals at neutral to slightly alkaline pH, with minimal contribution from precipitation. Similarly, Bonanno and Lo Giudice [

21] demonstrated that

P. australis effectively accumulates heavy metals from water and sediments at pH 7–8, attributing the removal to biosorption rather than precipitation. These findings align with our results, confirming that the observed metal removal at pH 7–8 is primarily due to biosorption by

P. australis biomass. Cellulose contains a high percentage of hydroxyl (-OH) functional groups, which can participate in metal ion binding. As pH increases, these functional groups can deprotonate, enhancing their ability to interact with metal cations through electrostatic attraction and complexation. The overall ability of a biosorbent to bind cations can be quantified by its cation exchange capacity (CEC) at a given pH; however, biosorption is a complex process that also involves mechanisms such as complexation, precipitation, and physical adsorption.

P. australis has a high cellulose content, but lignin and hemicellulose also contribute to its biosorption capacity by providing additional functional groups such as carboxyl and phenolic groups. Polysaccharides like cellulose, along with structurally related biopolymers such as chitin and chitosan, are widely used in water treatment due to their ability to adsorb a variety of contaminants, including heavy metals, dyes, phenols, pesticides, and detergents. The pH of the solution strongly influences the biosorption process, as it affects the charge of functional groups on the biomass surface. Torres [

22] reported that pH plays a key role in determining metal uptake, as a more negatively charged biosorbent surface generally enhances the adsorption of positively charged metal cations. For many heavy metals, biosorption efficiency increases at neutral to slightly alkaline pH (typically between 6.5 and 8.0) due to reduced competition with hydrogen ions (H⁺) and increased electrostatic attraction between the metal cations and the biosorbent. However, the optimal pH range varies depending on the specific metal and biosorbent, as some metals exhibit different binding affinities and solubility characteristics at different pH levels. The optimum pH was selected as 7 for further biosorption experiments.

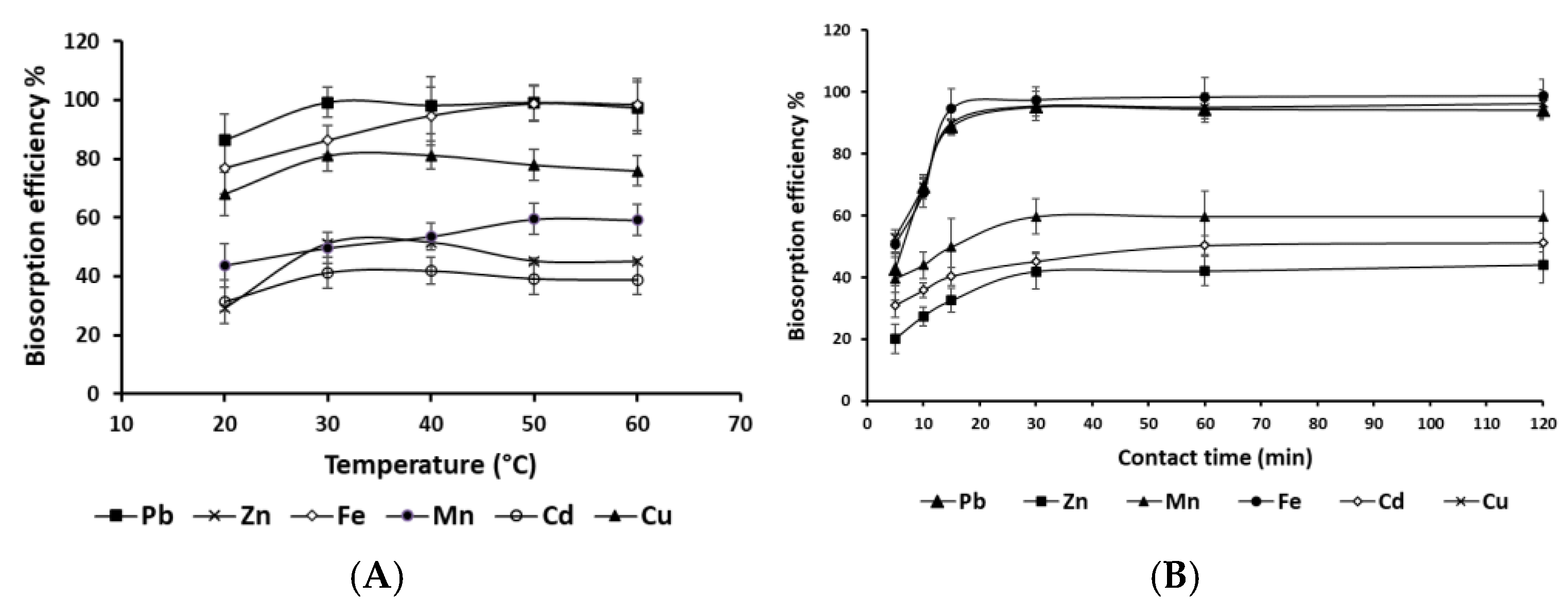

3.3.2. Effect of Temperature and Biosorption Time

To investigate the influence of temperature on the biosorption efficiency of heavy metals, the biosorption performance of Pb, Zn, Fe, Mn, Cd, and Cu was evaluated across a range of temperatures (20–60°C). The results revealed a clear temperature-dependent relationship, with significant increases in efficiency observed up to an optimal temperature range of 30–50°C, followed by a decline at 60°C, as illustrated in

Figure 4A. At a low temperature of 20°C, the biosorption efficiency was notably low for all tested metals. Among the metals, Pb demonstrated the highest biosorption efficiency, peaking between 30–50°C before slightly decreasing at 60°C. Zn, Cu, and Cd showed optimal biosorption at 30–40°C, with a decline beyond this range, while Fe and Mn reached their maximum efficiency at 50°C. The observed trends suggest that temperature significantly influences biosorption thermodynamics, with positive enthalpy changes (ΔH°) indicating an energy-driven process. The initial increase in efficiency is likely due to enhanced metal ion kinetics and improved biomass-metal interactions, while the decline at higher temperatures may result from biomass degradation, binding site saturation, or changes in metal oxidation states. These findings are consistent with previous studies, underscoring the importance of temperature optimization in biosorption processes for effective heavy metal removal [

22]. A key advantage of our results is the ability to achieve high biosorption efficiency at 30°C, making it a cost-effective and practical option compared to other plant biomasses such as

Eichhornia crassipes and

Saccharum officinarum which require temperatures above 50°C for optimal adsorption efficiency [

23]. This reduces energy costs and operational limitations, enhancing the feasibility of large-scale applications. To further optimize the biosorption process, the effect of reaction time on metal removal efficiency was investigated (

Figure 4B). The study revealed a progressive increase in metal uptake over time, with the highest removal rates observed between 30 and 120 minutes. Initially, at 5 minutes, the removal efficiencies were relatively low across all metals (Cu = 52.85%, Cd = 31.03%, Pb = 42.69%). However, as the reaction time increased, significant improvements in metal removal were observed, reaching optimal levels by 30 minutes. Beyond this point, removal efficiencies plateaued, with only minor variations at 60 and 120 minutes, indicating that equilibrium was achieved within 30–60 minutes. This study demonstrates that a retention time of 30 minutes and a temperature of 30°C are sufficient to achieve optimal removal for most metals, minimizing energy consumption and processing costs while ensuring effective heavy metal removal.

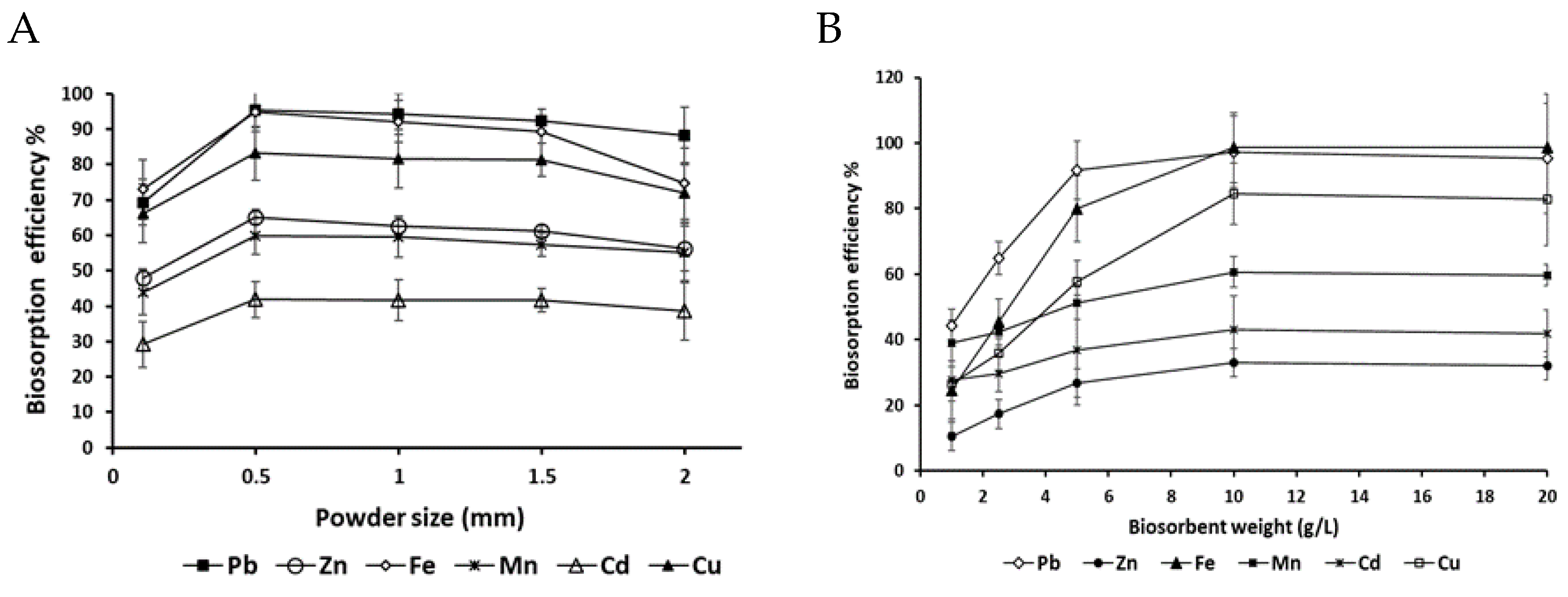

3.3.3. Effect of Powder Sizes and Weight Ratio on Biosorption

Understanding the effect of powder size and weight ratio on biosorption is crucial for optimizing heavy metal removal efficiency, as these parameters directly influence the availability of binding sites and the overall performance of biosorbents. As shown in

Figure 5, this study demonstrates that the biosorption efficiency of heavy metals (Pb, Zn, Fe, Mn, Cd, Cu) using

P. australis biomass is highly dependent on biosorbent weight ratio, with an optimal concentration of 10 g/L for most metals. Beyond this concentration, efficiency plateaus or decreases due to the saturation of active binding sites. This saturation effect was also observed in a study using

Citrus sinensis peel [

9]. Notably, Pb (97.31%) and Fe (98.59%) exhibited high biosorption efficiencies, consistent with their strong affinity for functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amine groups present in the biomass [

24]. In contrast, Zn (33.06%) and Cd (43.17%) showed lower efficiencies due to weaker binding affinity, while Mn (60.6%) displayed intermediate behavior. These results underscore the potential of plant biomass as a low-cost and sustainable biosorbent for heavy metal removal, while highlighting the importance of optimizing biosorbent weight to avoid inefficiencies caused by saturation. Regarding the effect of

P. australis powder size on biosorption, the study reveals that biosorption efficiency varies significantly with particle size. Smaller powder sizes (e.g., 0.106 mm) generally yield lower efficiencies, while optimal performance is achieved at intermediate sizes (0.5 to 1 mm). However, efficiency declines at larger sizes (e.g., 2 mm), likely due to reduced surface area and limited accessibility of binding sites. These findings align with previous studies on plant-based biosorbents. For instance, Sharma and Devi [

25] demonstrated that optimizing particle size in snail shell dust enhances heavy metal ion removal, emphasizing the importance of surface area and binding site availability. Similarly, research on

Opuntia fuliginosa and

Agave angustifolia showed that a particle size of 572 µm achieved 93% removal efficiency for Pb²⁺ [

24,

25,

26]. Overall, the study highlights that increasing biosorbent weight enhances biosorption efficiency by providing more binding sites for heavy metal ions, thereby increasing biosorption capacity. However, careful optimization of both weight and particle size is essential to maximize efficiency and avoid saturation or surface area limitations.

ANOVA revealed significant differences (P < 0.0001) in biosorption between heavy metals and powder sizes. Powder size significantly affected the biosorption of all metals, as confirmed by the LSD test (value = 0.9004 at P < 0.05). Similarly, biosorbent weight also had a significant impact on metal biosorption (P < 0.0001), with the LSD test supporting these differences (value = 2.102 at P < 0.05).

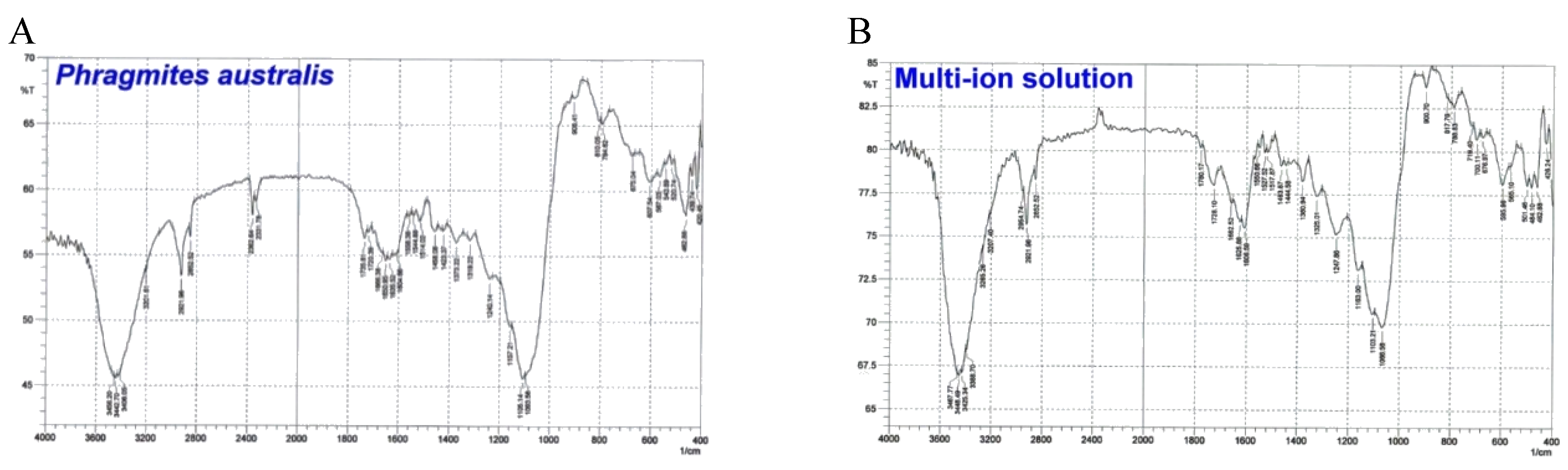

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis of

P. australis biosorbents, before and after exposure to a multi-ion solution containing various heavy metals, highlights key functional groups involved in biosorption (

Figure 6). For instance, a study on the adsorption of heavy metals by

P. australis demonstrated that the biomass exhibits a high capacity for metal uptake, with the adsorption process being strongly influenced by the initial metal concentration, pH levels, and specific plant tissues used [

27]. Peaks at 3365–3423 cm⁻¹, attributed to -OH and -NH stretching, confirm the role of hydroxyl and amine groups in metal binding. Carboxyl (-COOH) groups also played a crucial role, as evidenced by peaks at 1660–1734 cm⁻¹ (-COO⁻) and 1640–1653 cm⁻¹ (-COOH). These shifts indicate ion exchange, where hydrogen ions are replaced by metal cations, forming stable complexes. The Pb(II) exhibited stronger interactions with carboxyl groups than Cd(II), aligning with previous studies on fungal biomass. Additionally, carbonyl (-C=O) and ether (-C-O) groups contributed to biosorption, with -C=O stretching at 1226–1400 cm⁻¹ and -C-O stretching at 1049–1200 cm⁻¹. Metal adsorption led to peak shifts, confirming surface modifications. Unlike

A. rubescens,

P. australis showed peaks at 850–894 cm⁻¹ (-C-N bonding in amines), suggesting protein-based interactions in biosorption. The decrease in peak intensities in metal-loaded samples compared to the control suggests reduced bond stretching due to hydrogen ion exchange with heavy metals.. The results of this study are confirmed by Li et al. [

28] in their comparative study on the potentiality of phosphorus-accumulating organism biomasses in biosorption of Cd(II), Pb(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) from aqueous solutions, which reported that the -COO and -C=O groups are responsible for the uptake of Zn ions. Furthermore, the results of this study also agreed with Akar et al. [

29] in their study on the removal of Pb from an aqueous solution using Cucumis melo, which found that hydroxyl and carboxyl groups were responsible for the uptake of lead ions. Overall, FTIR data confirm that biosorption in

P. australis occurs via ion exchange, complexation, and electrostatic interactions involving hydroxyl, carboxyl, amine, carbonyl, and ether groups. Peak shifts indicate chemical modifications upon metal binding, with variations between species reflecting differences in biochemical composition and metal affinity. These findings reinforce the role of key functional groups in determining biosorption efficiency.

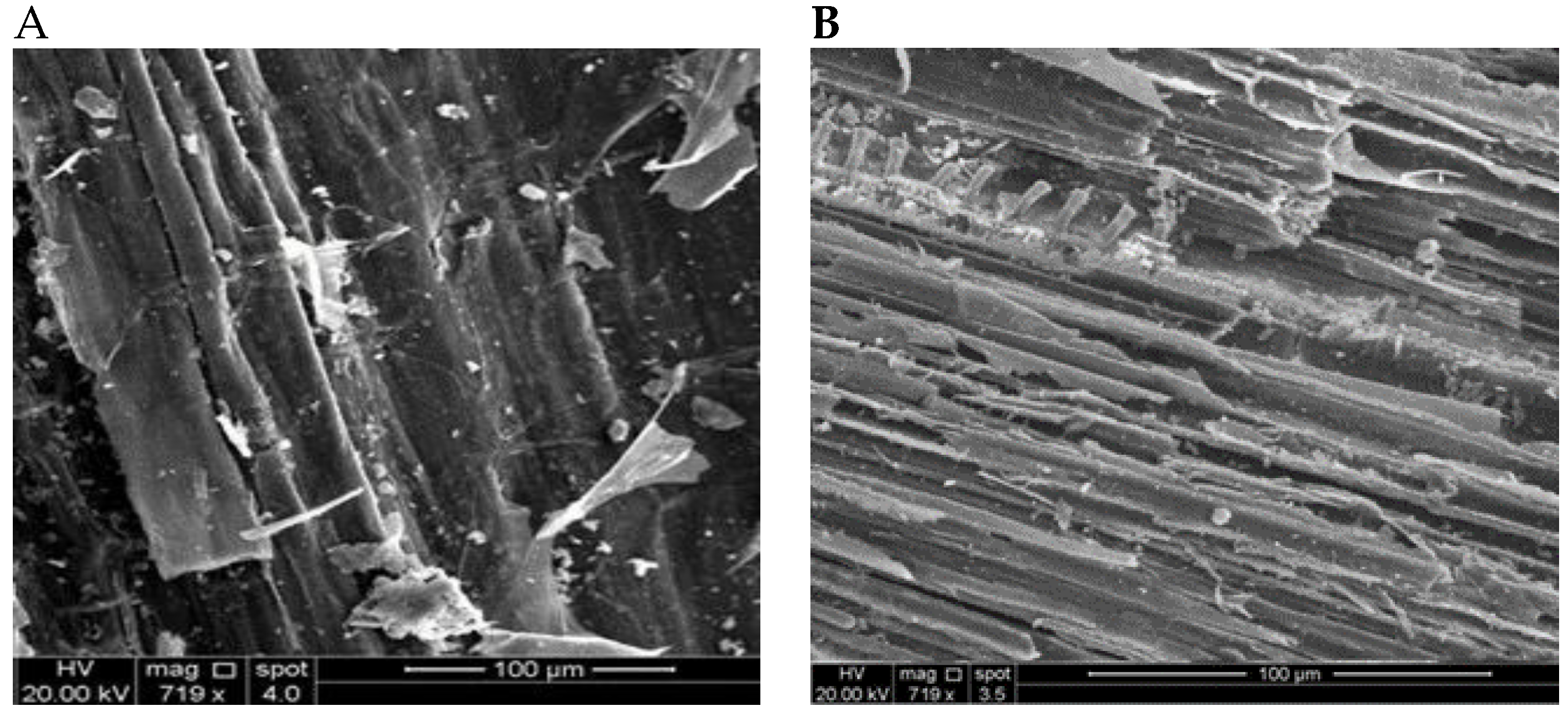

3.5. SEM Biomass Investigation

The morphology of the raw and metal-treated biomass was investigated using SEM (Inspect S50, FEI company, Netherlands). The SEM analysis of

P. australis before and after exposure to a heavy metal mixture, as shown in

Figure 7, reveals significant morphological transformations, highlighting the impact of metal adsorption on the biosorbent's surface structure. In the untreated sample (

Figure 7A), the surface appears relatively smooth, with well-defined fibrous structures characteristic of plant cell walls. This observation aligns with previous studies [

30], which reported similar structural integrity in unmodified plant biomass. However, after treatment with heavy metals, the surface of

P. australis exhibits increased roughness and porosity, accompanied by visible cracks and flaking (

Figure 7B). These alterations suggest significant structural modifications, likely due to metal ion interactions through mechanisms such as ion exchange and complexation. Furthermore, the presence of small deposits on the biosorbent surface indicates successful metal adsorption, consistent with the findings of Kaleem et al. [

31]. Similar morphological changes have been reported in other plant-based biosorbents, reinforcing the efficiency of

P. australis in heavy metal removal [

32]. These results support the potential application of this biomass as an effective biosorbent for heavy metal remediation, providing insights into its suitability for wastewater treatment and environmental detoxification.

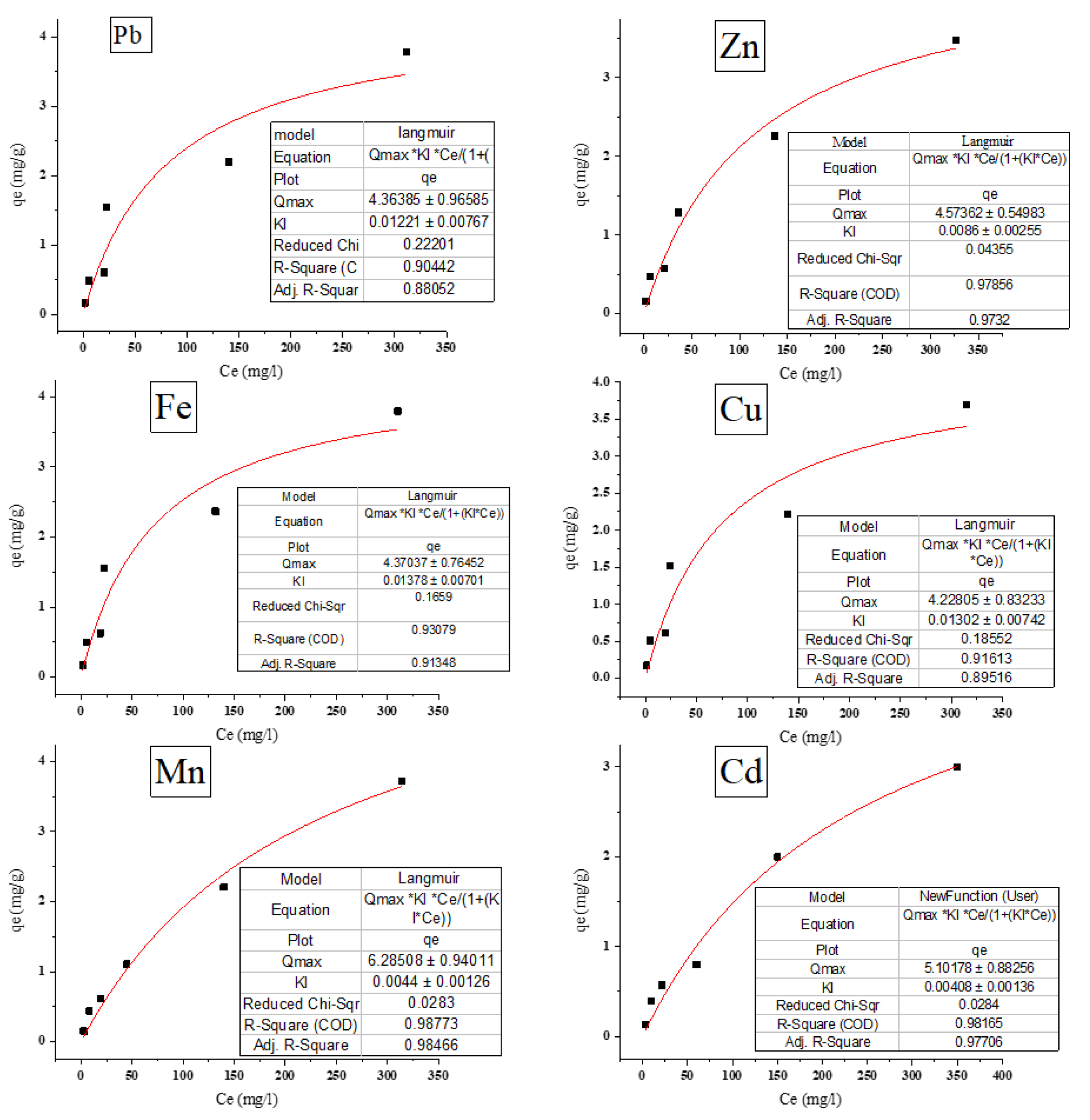

3.6. Isotherm Studies

3.6.1. Langmuir Isotherm

Figure 8 presents the correlation coefficients (R

2) for the adsorption of various metal ions, demonstrating values greater than 0.90 for all cases. This indicates a good fit of the experimental data to the Langmuir adsorption isotherm model. Similar high (R

2) values have been reported in recent studies, such as those by Liu et al. [

33], confirming the robustness of the Langmuir model in modeling metal ion adsorption onto various waste biosorbents.

The maximum adsorption capacities qmax and Langmuir constants KL were calculated using Origin software, as shown in

Table 1. The adsorption capacities ranged from 4.228 ± 0.832 mg g⁻¹ for Cu²⁺ to 6.285 ± 0.94 mg g⁻¹ for Mn²⁺, suggesting varying affinities for different metal ions. These results are consistent with previous studies [

31,

32,

33,

34], which also observed such variations. The Langmuir separation factor (RL) was calculated for all metal ions and concentrations, with values between 0 and 1, indicating favorable adsorption. At lower concentrations, RL values were closer to 1, while at higher concentrations, they approached 0, suggesting that adsorption is more favorable at lower metal ion concentrations. These trends are similar to those observed by Kumar et al. [35], who reported higher adsorption efficiency at lower concentrations.

The equilibrium parameter,

RL, a dimensionless constant separation factor, can also be used to represent the Langmuir adsorption isotherm as appeared in equation 3 below:

Where

Ci is the starting concentration in mg L

-1 and

KL is the Langmuir constant. The values of

RL were calculated for all concentrations and all the metal ions as shown in

Table 2.

The interpretation of

RL values confirms that all values fall within the favorable range (0 < RL < 1), supporting the monolayer adsorption model of the Langmuir isotherm. The correlation coefficients exceeding 0.95 further validate the model's applicability to the experimental data. These findings align with previous research [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], which also reported good fits to the Langmuir isotherm for various metal ions. In conclusion, the

P. australis demonstrated effective removal of metal ions, particularly Pb²⁺, Zn²⁺, and Mn²⁺, with the highest efficiency observed at lower concentrations. The Langmuir isotherm model adequately described the adsorption behavior, indicating the potential of the biosorbent for wastewater treatment.

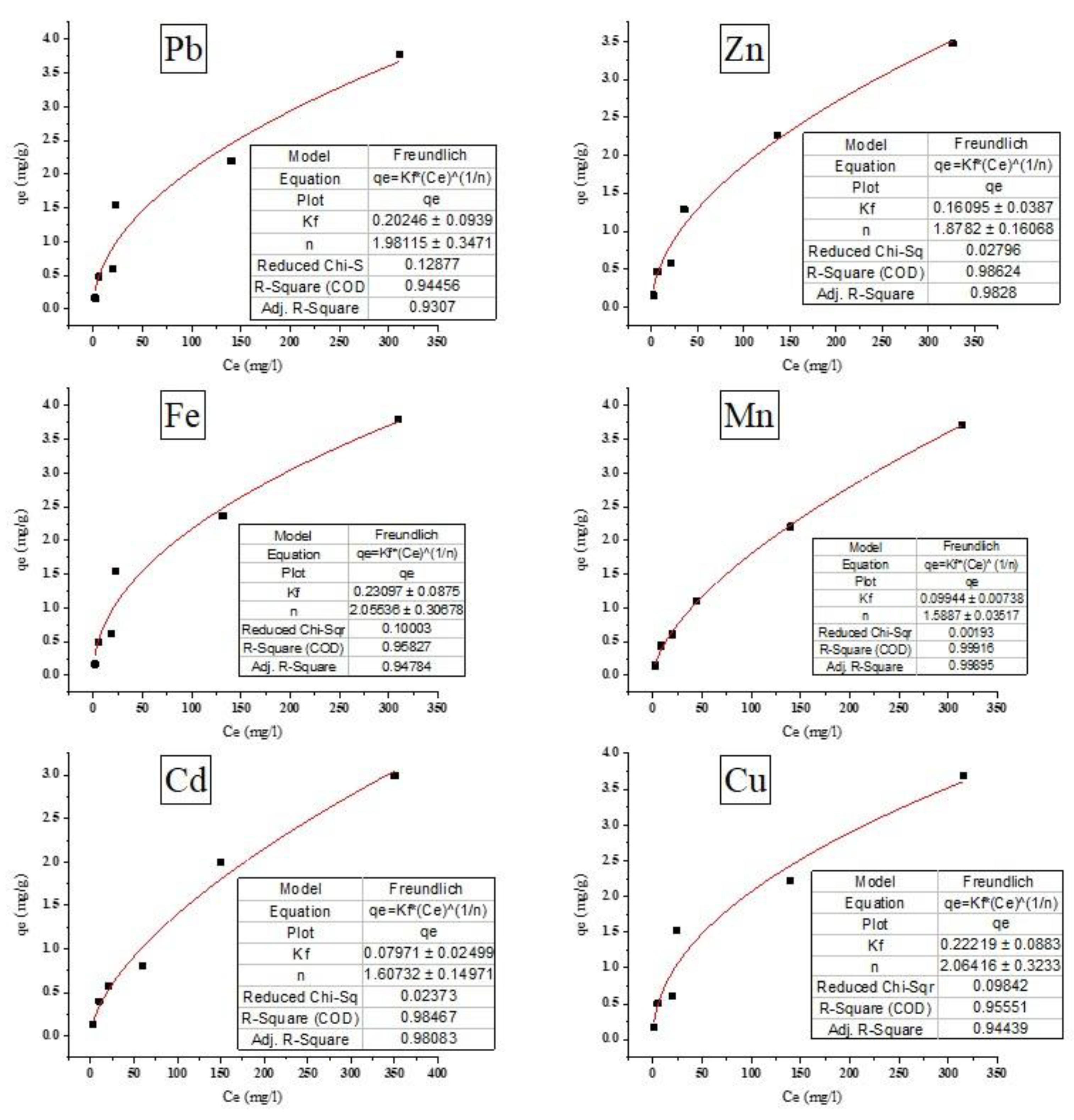

3.6.2. Freundlich Isotherm

The relationship between qe and Ce presented in

Figure 9 was shown to be significantly correlated with R

2 more than 0.90. The evaluated constants are shown in

Table 3, which reveals the fact that the n values for all metal ions adsorption were more than one indicating that the adsorption process is physical and has a high degree of heterogeneity. A strong affinity (high n value) was not equivalent to a large adsorption capacity (high K

f value). The K

f was determined by particle parameters such as size distribution, specific surface area, and surface functional groups. The adsorption isotherm for all the metal ions was fitted to Freundlich n a correlation coefficient of more than 0.9 as shown in

Figure 9 and the n values of more than 1.

The data compiled in Tables 2, 3, and 4 indicate that the adsorbent was fitted to Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms.

Kf represents the adsorption capacity, with higher values indicating stronger affinity for metal ions.

P. australis showed the highest adsorption for Fe²⁺ (0.231), Cu²⁺ (0.222), and Pb²⁺ (0.202), suggesting strong interactions with its functional groups. In contrast, Zn²⁺ (0.161), Mn²⁺ (0.099), and Cd²⁺ (0.080) had lower adsorption, likely due to differences in ionic properties. The adsorption intensity (n > 1) confirmed favorable adsorption, with Cu²⁺ (2.06), Fe²⁺ (2.06), and Pb²⁺ (1.98) exhibiting the strongest affinity. The lower

n values for Mn²⁺ (1.59) and Cd²⁺ (1.61) indicates weaker interactions. These results suggest

P. australis is highly effective for Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Pb²⁺ removal, making it a promising biosorbent for wastewater treatment. However, optimizing surface modifications may enhance its efficiency for lower-affinity metals like Cd²⁺ and Mn²⁺. The results of this study align with previous research demonstrating the effectiveness of plant-derived materials for heavy metal removal, where adsorption capacity is influenced by factors such as charge, size, and affinity for functional groups on the biosorbent surface. For example, it was reported that

P. australis had high adsorption capacities for Pb²⁺ and Cu²⁺, similar to our findings, where these metals exhibited the highest

Kf values. This suggests that

P. australis is particularly effective at removing metals with high charge densities. It was reported previously that the higher biosorption capacity for Pb²⁺ and Cu²⁺ compared to Zn²⁺, consistent with our results [

27]. In contrast, the lower adsorption capacities for Zn²⁺, Mn²⁺, and Cd²⁺ in our study align with Torres [

22], who reported lower biosorption efficiencies for these metals, likely due to their smaller ionic radii and weaker complexation. The higher n values for Cu²⁺, Fe²⁺, and Pb²⁺ in our study suggest favorable adsorption, Overall, our results reinforce

P. australis potential as an effective biosorbent, particularly for Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Fe²⁺. Optimizing the biomass, such as chemical modification, may enhance efficiency for metals like Zn²⁺, Mn²⁺, and Cd²⁺.

4. Conclusion

This study evaluated the potential of P. australis biomass as an adsorbent for removing heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions. The choice of P. australis was driven by its high availability, low cost, and proven effectiveness in previous biosorption studies. Additionally, this plant material, often considered waste and unsuitable for animal feed, is typically discarded through burning, contributing to environmental pollution. The experimental conditions, including initial metal ion concentration, temperature, pH, retention time, biomass weight, and the form of the plant residue (dry or powder), were systematically optimized. The optimal adsorption conditions for all studied metals were identified as a temperature range of 30–50°C, pH 7, a retention time of 30 minutes, and an adsorbent dosage of 10 g/L. The powdered form of the plant with a particle size of 0.5 mm demonstrated the best adsorption performance. The FTIR analysis revealed that ion exchange was the primary adsorption mechanism, with interactions between metal ions and active functional groups such as C-H, C=O, and O-H. SEM images further confirmed changes in the biosorbent surface morphology after adsorption, indicating strong surface interactions between the metal ions and the plant material. Adsorption isotherms model, based on non-linear Langmuir and Freundlich models, showed a good fit. The Langmuir model suggested favorable monolayer adsorption, with maximum capacities ranging from 4.22 mg g⁻¹ for copper to 6.29 mg g⁻¹ for manganese. Higher adsorption efficiency was observed at lower concentrations, supported by favorable separation factor values. These results align with previous studies, confirming the reliability of the model. The Freundlich model also provided a good fit, with values greater than 1, indicating physical adsorption and heterogeneity in adsorption sites. Iron, lead and cooper exhibited the highest adsorption capacity, while cadmium and manganese had lower capacities. This selective behavior highlights the potential of P. australis for targeted heavy metal removal. Therefore, P. australis is a highly efficient, eco-friendly, and cost-effective material for the biosorption of heavy metals from wastewater. Future research should focus on the regeneration of P. australis for repeated use and explore its applicability in more complex wastewater matrices and large-scale industrial processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. S.M. and M.T.; methodology, S.M. and M.T.; software, A.H. and S.M.; validation, A.H. S.M. and M.T.; formal analysis, M.T.; investigation, M.T.; resources, A.H. S.M. and M.T.; data curation, S.M. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H. and S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and M.T.; supervision, S.M. and M.T.; project administration, M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for its financial support and are grateful to the specialized scientific staff working in the Research Laboratory of Environmental Sciences and Sustainable Development LASED LR18ES32, Sfax, Preparatory Institute for Engineering Studies, University of Sfax, Tunisia. Additionally, the scientific staff working in the Biology Department, College of Science, University of Anbar – Iraq, for their valuable assistance in completing this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahamad, A.; Alshehrei, F.; Ali, S.A.; Khan, M.S. Impact of heavy metals on aquatic life: Recent scientific progress and future perspectives. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1374835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briffa, J.; Sinagra, E.; Blundell, R. Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzaman, A.T.T.; Koohi, M.K.; Sadeghi, M.; Abedian, Z. Toxic mechanisms of cadmium and its possible risk of male infertility: A systematic review. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2023, 42, 09603271231210262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkiewicz, K.; Gawel, M.; Kałucka, M.; Jabłońska-Trypuć, A. Cadmium toxicity and health effects—A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.G.; da Silva, T.L.; de Souza, A.G. Environmental impacts related to drilling fluid waste disposal. Fuel 2022, 310, 122301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V.; Mandalia, H.C. Petroleum industries: Environmental pollution and its remediation. Int. J. Separ. Environ. Sci. 2012, 1, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Zaimee, A.A.; Jami, M.S.; Alam, L.; Bhawani, S.A. Heavy metals removal from water using natural adsorbents. Water 2021, 13, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beya, S.; Moulay, M.; Ramdhani, A.; Mehellou, M. Modern biotechnological methods for wastewater treatment. Chim. Techno Acta 2022, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwikima, M.J.; Kayombo, S.; Mbuligwe, S.E. Potentials of agricultural wastes in removing heavy metals from contaminated water: A review. Sci. Afr. 2021, 13, e00934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertu, D.I.; Cheregi, M.-C.; Oancea, R.E. Modeling the biosorption process of heavy metals using different techniques. Process 2022, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Naushad, M.; Alqadami, A.A.; ALOthman, Z.A. Orange peel as an effective adsorbent for the removal of Cr(VI) from wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L. Banana peel biochar for the removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8534–8545. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.; Rajendran, S.; Kumar, S. Pomegranate peel as a biosorbent for lead removal from wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitimus, A.D.; Pirvu, M.; Dragomir, R.E. Accumulation of heavy metals in Phragmites australis: A phytoremediation approach. Sustain. 2023, 15, 8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidian, A.H.; Afyuni, M.; Abbaspour, K.C. Phytoremediation of heavy metals in gas refinery wastewater using Phragmites australis. Int. J. Aquat. Biol. 2014, 2, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi, S.; Fazlzadeh, M.; Asgari, G. Potential of Phragmites australis to bioaccumulate heavy metals from landfill leachate. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 64, 105657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, M.E.; Gutiérrez-González, E.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A. Isotherm and kinetic models linearization strategies: An overview. Separ. Purif. Rev. 2022, 51, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.H.K.; Seshaiah, K.; Reddy, A.V.R.; Lee, S.M. Biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solutions using Moringa oleifera bark: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, N.; Villaescusa, I. Determination of sorbent point zero charge: Usefulness in sorption studies. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2009, 7, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, E.; Rousseau, D.P.L.; Meers, E.; Tack, F.M.G.; De Pauw, N. Phytoremediation of heavy metals by Phragmites australis in constructed wetlands. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.; Giudice, R.L. Heavy metal bioaccumulation by Phragmites australis (common reed) in a polluted Mediterranean river: Implications for phytoremediation. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E. Biosorption of heavy metals: Recent advances and future perspectives. Process 2020, 8, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Li, K.; Sun, X. Removal of heavy metals by silica nanotubes functionalized with amine groups. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 286, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyairo, J.; Atieno, F.; Makhanu, S. Adsorption of heavy metals from water using modified food waste-derived adsorbents. Front. Environ. Chem. 2025, 6, 1526366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Devi, R. Removal of heavy metals from aqueous solution using snail shell dust: A biosorption study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 31879–31896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Trujillo, J.; Esparza-García, F.; Cervantes, F.J. Biosorption of heavy metals by native Opuntia and Agave species. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Ríos, C.; Rodríguez-Estrella, T.; Hernández-Rodríguez, M. Mercury biosorption by Phragmites australis in contaminated aquatic systems. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y. Role of phosphorus-solubilizing organisms in biosorption of heavy metals. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, T.; Tosun, I.; Kiran, I.; Gedikbey, T. Biosorption of lead(II) ions onto waste biomass of Cucumis melo. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 185–186, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.R.; Islam, M.A.; Ahmed, M. Fibrous food waste-derived biosorbents for heavy metal removal. Molecules 2023, 28, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, M.; Rehman, R.; Khan, M.N. Cadmium and lead biosorption by Nostoc commune biomass. Molecules 2023, 28, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arief, V.O.; Trilestari, K.; Sunarso, J.; Indraswati, N. Biosorption of heavy metals using low-cost biosorbents: A review, CLEAN–Soil, Air. Water 2008, 36, 937–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Chen, H. Development of rice straw-based bioadsorbents for removal of heavy metals. BioRes. 2023, 18, 3709–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Jaiswal, D.; Singh, N. Adsorption isotherm models and their comparison for heavy metal removal. Chemosphere 2021, 276, 130176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Curve of zero-charge point pHpzc of P. australis (T= 30°C, agitation speed = 150 rpm, dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L, and pH = 2–12).

Figure 1.

Curve of zero-charge point pHpzc of P. australis (T= 30°C, agitation speed = 150 rpm, dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L, and pH = 2–12).

Figure 2.

Influence of different P. australis biomass physical form, powdered versus non-powdered (dry pieces), on the biosorption of heavy metal ions (T= 30°C, agitation speed = 150 rpm, a dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L, and pH = 7).

Figure 2.

Influence of different P. australis biomass physical form, powdered versus non-powdered (dry pieces), on the biosorption of heavy metal ions (T= 30°C, agitation speed = 150 rpm, a dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L, and pH = 7).

Figure 3.

Influence of pH on heavy metal biosorption by P. australis (T= 30°C, agitation speed = 150 rpm and dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L).

Figure 3.

Influence of pH on heavy metal biosorption by P. australis (T= 30°C, agitation speed = 150 rpm and dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L).

Figure 4.

Effect of temperature (A) and contact time (B) on heavy metal biosorption by P. australis under optimized conditions (T = 30°C, agitation speed = 150 rpm, biosorbent dose = 10 g/L, pH = 7).

Figure 4.

Effect of temperature (A) and contact time (B) on heavy metal biosorption by P. australis under optimized conditions (T = 30°C, agitation speed = 150 rpm, biosorbent dose = 10 g/L, pH = 7).

Figure 5.

Effect of plant powder size (A) and biomass weight (B) on the removal efficiency of heavy metal ions by P. australis under optimized conditions (T= 30°c, agitation speed = 150 rpm, pH = 7).

Figure 5.

Effect of plant powder size (A) and biomass weight (B) on the removal efficiency of heavy metal ions by P. australis under optimized conditions (T= 30°c, agitation speed = 150 rpm, pH = 7).

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of P. australis without heavy metals (A) and multi-ion solution (B).

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of P. australis without heavy metals (A) and multi-ion solution (B).

Figure 7.

SEM pictures for Raw biomass before treatment (A) and heavy metals after treatment (B).

Figure 7.

SEM pictures for Raw biomass before treatment (A) and heavy metals after treatment (B).

Figure 8.

Langmuir isotherm for removing metal ions from aqueous solutions by P. australis (T= 30°C, contact time 30 min, agitation speed = 150 rpm, dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L, and pH = 7).

Figure 8.

Langmuir isotherm for removing metal ions from aqueous solutions by P. australis (T= 30°C, contact time 30 min, agitation speed = 150 rpm, dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L, and pH = 7).

Figure 9.

Freundlich isotherm for removing metal ions from aqueous solutions (T= 30°C, contact time 30 min, agitation speed = 150 rpm, dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L, and pH = 7).

Figure 9.

Freundlich isotherm for removing metal ions from aqueous solutions (T= 30°C, contact time 30 min, agitation speed = 150 rpm, dose of biosorbent = 10 g/L, and pH = 7).

Table 1.

Langmuir isotherm parameters (qmax and KL) for the adsorption of metal ions.

Table 1.

Langmuir isotherm parameters (qmax and KL) for the adsorption of metal ions.

| Metal ion |

qmax(mg g-1) |

KL (L mg-1) |

| Pb2+ |

4.363±0.965 |

0.01221±0.0076 |

| Zn2+ |

4.57362±0.549 |

0.0086±0.0025 |

| Fe2+ |

4.37037±0.764 |

0.01378±0.0070 |

| Mn2+ |

6.28508±0.94 |

0.0044±0.0012 |

| Cd2+ |

5.10178±0.882 |

0.00408±0.0013 |

| Cu2+ |

4.22805±0.832 |

0.01302±0.0074 |

Table 2.

The RL values at various concentrations and different metal ions.

Table 2.

The RL values at various concentrations and different metal ions.

| Ci (mg/L) |

Pb2+

|

Zn2+

|

Fe2+

|

Mn2+

|

Cd2+

|

Cu2+

|

| 10 |

0.8912 |

0.9208 |

0.8789 |

0.9579 |

0.9608 |

0.8848 |

| 30 |

0.7319 |

0.7949 |

0.7075 |

0.8834 |

0.8909 |

0.7191 |

| 50 |

0.6209 |

0.6993 |

0.5921 |

0.8197 |

0.8306 |

0.6057 |

| 100 |

0.4502 |

0.5376 |

0.4205 |

0.6944 |

0.7102 |

0.4344 |

| 250 |

0.2468 |

0.3175 |

0.2250 |

0.4762 |

0.4950 |

0.2350 |

| 500 |

0.1407 |

0.1887 |

0.1267 |

0.3125 |

0.3289 |

0.1332 |

Table 3.

The values of n and Kf ±SD for the metal ions with the adsorbent.

Table 3.

The values of n and Kf ±SD for the metal ions with the adsorbent.

| Metal ion |

Kf |

n |

| Pb2+ |

0.20246±0.093 |

1.9811±0.347 |

| Zn2+ |

0.16095±0.038 |

1.8782±0.160 |

| Fe2+ |

0.23097±0.087 |

2.05536±0.306 |

| Mn2+ |

0.09944±0.007 |

1.5887±0.035 |

| Cd2+ |

0.07971±0.024 |

1.60732±0.149 |

| Cu2+ |

0.22219±0.088 |

2.06416±0.323 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).