1. Introduction

In May 2022, an outbreak of mpox caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV) clade IIb spread globally to non-endemic countries. This outbreak primarily affected primarily gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men due to transmission dynamics involving close physical contact and sexual practices in contexts such as social gatherings or sexual networks [

1,

2].

In response, different health authorities of the affected regions of the world rapidly approved the Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) for mpox prevention, branded as Jynneos, Imvanex or Imvamune. Initially developed for smallpox [

3], this vaccine received emergency use authorization to provide prophylaxis against MPXV infection [

4]. Based on epidemiological data, regulatory agencies recommended the MVA-BN vaccine for both post-exposure and pre-exposure prophylaxis in key populations at increased risk of mpox acquisition. Intradermal administration was prioritized to reach a higher number of individuals vaccinated in a moment of vaccine shortage [

5,

6]. However, no formal clinical trials specifically assessed the vaccine's efficacy against mpox.

In this context, analyses of health records became key sources of information. According to a meta-analysis of ten observational studies conducted early during the 2022 outbreak, a single-dose of the MVA-BN vaccine had 75% efficacy in preventing mpox [

7]. Further analyses of health records supported the vaccine's effectiveness among individuals with different risk factors for mpox acquisition [

8,

9,

10]. However, retrospective studies based on routine healthcare data are potentially associated with multiple biases, including unbalanced risk factors between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals [

11].

The design of observational studies that mirror the conditions of randomized controlled trials has been proposed to minimize biases associated with the secondary use of routine healthcare data, particularly unbalanced prevalence of risk factors between groups. This strategy, referred to as target trial emulation, has been extensively used to control for confounders in scenarios in which randomized-controlled trials are unfeasible [

12,

13,

14]. Studies conducted following this approach have found high efficacy of MVA-BN vaccination in individuals on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (HIV-PrEP) [

15] and moderate in individuals with additional risk factors, such as a recent history of sexually transmitted infections (STI)s [

16]. However, target emulation trials conducted to date were based on retrospective data extracted from administrative records, thus limiting the availability of information not routinely collected in health practice, such as detailed sexual behavior, or vaccine adverse reactions that did not trigger visits to the hospital or emergency room. To address these limitations, which restrict the range of variables available for analysis, we conducted a target trial emulation to assess the efficacy of the MVA-BN vaccine as pre-exposure to prevent symptomatic mpox, based on data prospectively collected using dedicated surveys for gathering information on sexual and social behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Outcomes

This was a multi-country, observational, prospective, target trial emulation study to assess the efficacy of the MVA-BN vaccine as pre-exposure to prevent symptomatic mpox. The study was conducted in Spain, Peru, Panama, and Chile.

Table S1 (Supplementary File 1) provides detailed information on the participating sites.

Between September 1, 2022 and June 15, 2023 individuals were invited to participate either by health staff in participating sites, or through posters and flyers in social venues, publications in social networks, and advertisements in dating apps.

The primary endpoint was reporting of symptomatic mpox at least 14 days after vaccine administration. Secondary endpoints included a sensitivity analysis on PCR or clinically confirmed mpox, as well as vaccine safety endpoints, such as hospitalization, sequelae, scarring, and other reactions at the injection site.

2.2. Participants and Matching for Trial Emulation

Individuals self-assessed the inclusion criteria, which were aligned with MVA-BN vaccination guidelines in the participating countries (Supplementary file 1). They included ≥18 years old, reporting at least one risk factor for MPXV infection: HIV-PrEP use, chemsex practices in the past 6 months, multiple sexual partners in the past year, history of STI in the past year, and living with HIV. Individuals meeting the inclusion criteria provided informed consent to participate. Individuals with past MPXV infection and those entering the study more than 42 days after the first vaccine dose were excluded.

The study was conceived as a target trial emulation in which vaccinated participants were paired on a 1:1 ratio with an unvaccinated individual with similar risk factors for MPXV infection from the same cohort (controls). Matching variables included demographic characteristics (age ±10 years, and country of recruitment), index date (i.e., date of baseline survey or vaccination, as defined below) ±28 days, and risk factors, including current HIV-PrEP use, HIV status, and at least two of the following conditions: history of STIs within the last 12 months, number of sexual partners in the past 12 months (1; 2-9; >9), engagement in chemsex practices in the past 6 months, and attendance to sex on premises venues in the past 6 months.

Pairs were censored during follow-up for the survival analysis at the time one of the individuals reported mpox or the unvaccinated individual reported being vaccinated. Individuals vaccinated during the follow-up (hereinafter, newly-vaccinated individuals) became candidates for the vaccinated group and were paired with a new unvaccinated individual meeting the matching if available.

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. The study protocol was approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRBs) or Independent Ethics Committee (IECs) in each participating country (

Table S2).

2.3. Study Procedures and Definitions

Within the recruitment period, consecutive individuals at the participating countries were offered to enroll the study. Study participants were asked to fill a baseline questionnaire, which gathered demographic, clinical, and sexual behavioral characteristics related to mpox risk factors, including HIV status, HIV-PrEP use, number of sexual partners, engagement in chemsex, history of STIs, and sexual activities at public or private venues. Participants received email alerts (monthly during the first 6 months and once every two months thereafter) with a link to the follow-up survey, aimed at updating information on vaccination status, any mpox diagnoses, changes in sexual health and practices, and occurrences of adverse reactions following vaccination. Since a considerable number of participants reported the onset of a long-lasting erythema at the injection site (i.e., initially reported as a persistent mark), an item regarding the duration of this event was added to the follow-up surveys. Full content of the baseline and follow-up surveys is provided in the Supplementary file 2.

All surveys were administered online using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Fight Infections Foundation. The surveys were designed to be self-administered, user-friendly, with questions appearing progressively. They could be filled with either a computer or a smartphone/tablet. The estimated time for answering the baseline and follow-up surveys were 5 minutes and 2 minutes, respectively. All data were stored in a secured repository associated with the REDCap platform, accessible only by designated members of the research team.

Participants who reported mpox onset during follow-up were contacted by a physician with expertise in mpox who interviewed them to collect data and images related to the clinical presentation of the disease and confirm the diagnosis (clinically confirmed mpox), gathering results of PCR test if available (PCR-confirmed mpox). Clinical presentation data included general, cutaneous, and mucosal symptoms, treatment received, hospitalization events, and outcomes such as resolution, sequelae, and scarring.

Vaccines were delivered according to the participating country’s local guidelines. For reference, participating countries recommended the administration of 2 doses given ≥28 days apart intradermally (0.1 mL). In some exceptional cases (pregnancy and immunosupression in Spain; risk of keloid formation in Peru) vaccine was administered subcutaneously (0.5 mL). For the study purpose, participants were considered vaccinated if they received at least one intradermal or subcutaneous dose of the MVA-BN vaccine during the study period.

The index date was set at the time participants answered the baseline survey, except for newly-vaccinated participants, for whom the index date was the first vaccination dose. Follow-up time spanned from the index date until mpox diagnosis, end of the follow-up period (i.e., March 31, 2024), or censoring due to a matching pair censored or being vaccinated during the follow-up.

The efficacy population consisted of all matched participants (i.e., vaccinated individuals and their matched controls that could be paired for the preselected matching variables) with at least one follow-up survey after the matching date.

The safety population consisted of all participants who reported vaccination with MVA-BN at baseline or during follow-up and who had responded to at least one follow-up survey for safety.

2.4. Statistical Methods

Preliminary data collected during Summer 2022 in Spain suggested that the incidence of mpox among population with risk factors could amount to 2% and that the vaccine could reduce the risk to approximately 50% when administered as pre-exposure strategy. Considering these preliminary figures and an anticipated 10% loss to follow-up, we estimated that a sample of 2,319 vaccinated and 2,319 unvaccinated matched individuals would provide 80% statistical power.

Categorical variables were described as frequency and percentage, whereas continuous variables were described as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the median and interquartile range (IQR, defined by the 25th and 75th percentiles) as appropriate. Covariate balance between groups was assessed based on the standardized mean difference (SMD), with a SMD difference higher than 0.25 considered relevant.

The primary analysis was conducted on the efficacy population. The primary endpoint was analyzed using exact confidence intervals for incidence risks, calculated according to Ulm et al.[

17] Cumulative incidence curves were adjusted for individual cluster effects and stratified by pairs. Differences between incidence curves at the end of follow-up were calculated, along with their 95% confidence intervals, using robust standard errors. Additionally, hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated by fitting a proportional hazards regression model, stratified by matched pairs and adjusted for individual cluster effects. Individuals censored for the primary endpoint (i.e., mpox onset) were described as counts and percentage by reason. A sensitivity analysis of efficacy was conducted by restricting the primary endpoint to mpox cases confirmed either clinically or by PCR. Vaccine safety was analyzed based on the frequency of adverse events on the safety population.

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants and Follow-Up

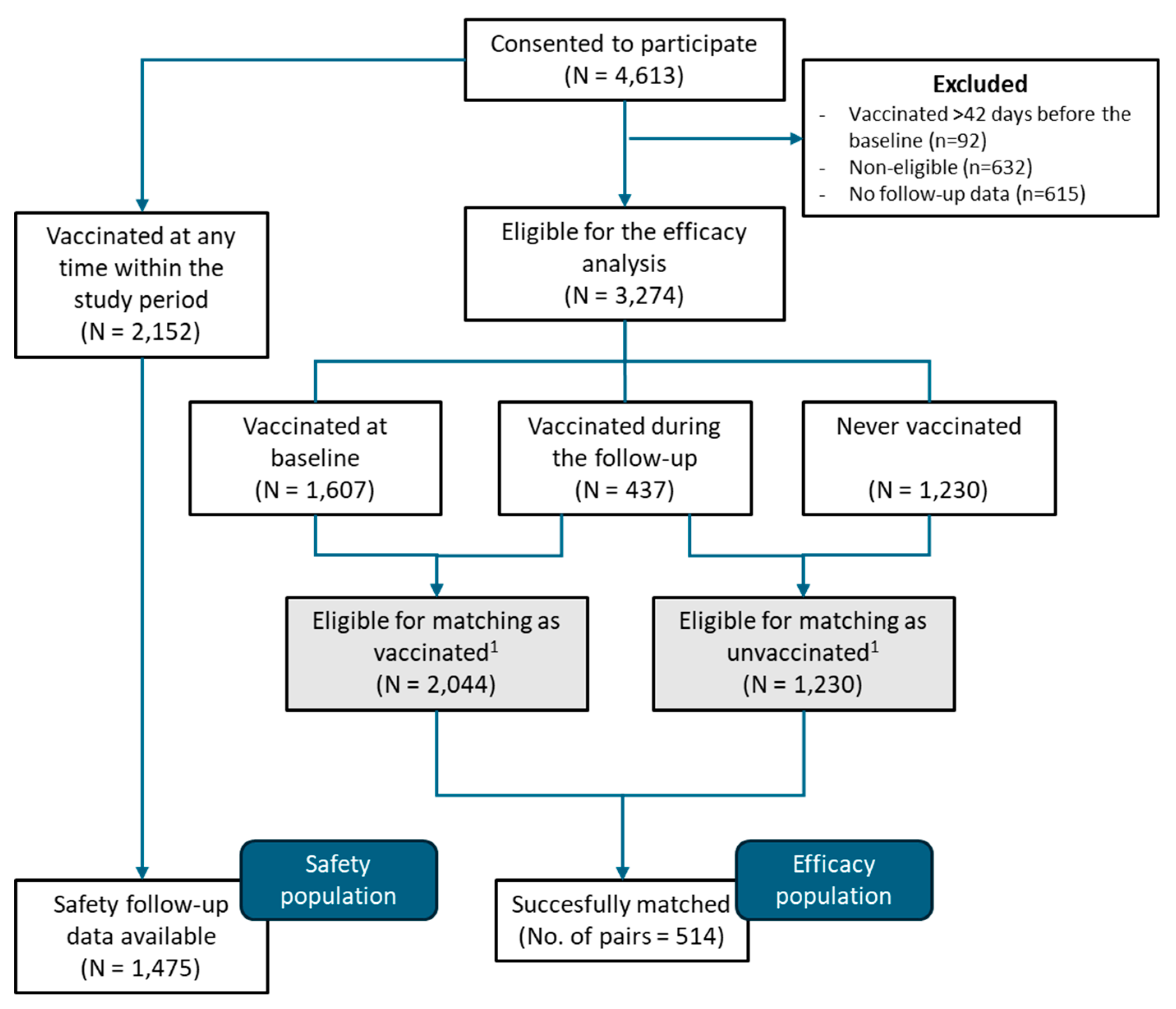

Between September 1, 2022, and June 15, 2023, a total of 4,613 individuals consented to participate in the REMAIN study. The efficacy population accounted for 1,028 (514 vaccinated and 514 unvaccinated) who completed the baseline and follow-up surveys and were matched pairwise for vaccinated-unvaccinated groups. The safety population accounted for 1,475 individuals who received the MVA-BN vaccine and completed at least one follow-up survey for safety (

Figure 1). The study was interrupted before reaching the planed sample size due to the global drop in mpox incidence.

Table 1 summarizes the main demographic characteristics and risk factors of the efficacy population at baseline. Vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals were well balanced regarding the main matching variables (i.e., age, HIV-PrEP use, and HIV status) and additional matching conditions: history of STIs within the last 12 months, number of sexual partners in the past 12 months, engagement in chemsex practices in the past 6 months, and attendance to sex on premises venues in the past 6 months. Other characteristics, such as ethnicity, gender of sexual partners, immunosuppressive disorder or treatment, and CD4 count were also similar in the two groups (

Table 1). On the other hand, while the country of recruitment was well balanced, relevant differences were observed regarding the city and site of recruitment (

Table S1). Vaccinated individuals were more frequently recruited in health centers compared to other recruitment sites or methods (i.e., hospitals, community-based centers for HIV and STIs, and vaccination centers).

Overall, participant pairs were followed up for a median of 9.3 months (IQR 4.7 – 13.7). We found no relevant differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated regarding the total number of answers (3,537 vs. 3,142, respectively; SMD 0.206) and the median surveys answered per participant (7 [IQR 4-10] vs. 6 [IQR 3-9]; SMD 0.206).

Table S3 summarizes the number of answers and follow-up data according to countries. The clinical characteristics, including onset of STIs, immunosuppression-related treatments, and sexual behaviors remained similar between vaccinated and unvaccinated during the follow-up (

Table 2).

3.2. Vaccine Efficacy

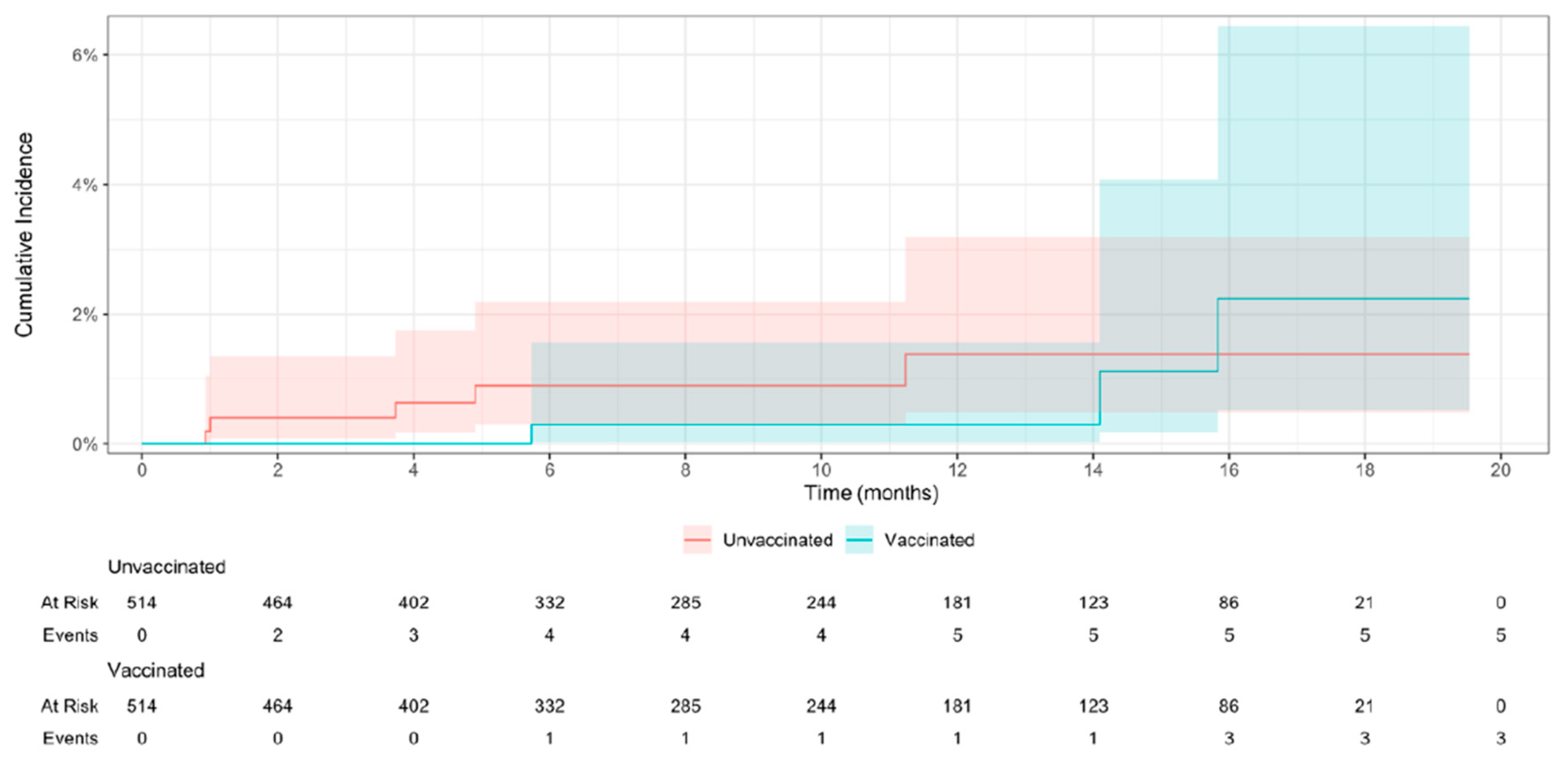

At the end of the follow-up period, 80 (15.6%) pairs of the efficacy population were censored, 72 (14.0%) due to unvaccinated participants who received the vaccine, and 8 (0.8%) due to the onset of mpox: 3 (0.6%) were reported in vaccinated individuals and 5 (1.0%) in unvaccinated. The resulting incidence (primary endpoint) rate was 0.63 (95% CI 0.0 – 1.46) cases per 1,000 person-months among vaccinated individuals and 1.05 (0.21 – 2.09) among unvaccinated. The survival analysis for efficacy, conducted on 9,570 person-months, showed no statistically significant differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated regarding the incidence of mpox (HR 0.6; 95% CI 0.21 – 1.70) (

Figure 2).

The sensitivity analysis was conducted considering only the three mpox cases with PCR or clinical confirmation: 1 (0.2%) among vaccinated individuals and 2 (0.4%) among unvaccinated. The corresponding incidence rate was 0.21 (0.0 – 0.63) per 1,000 person-months and 0.42 (0.0 – 1.05), respectively (HR 0.5; 95% CI 0.08 – 2.99). A full description of clinical presentation of mpox cases reported is provided in Supplementary file 1.

3.3. Vaccine Safety

Overall, 731 (49.6%) individuals reported at least one adverse reaction, being skin adverse reactions more common than systemic: 703/1,475 (47.7%) vs. 107/1,475 (7.3%). The most frequent skin reactions were injection site erythema (541/703; 36.7%), swelling (463/703; 31.4%), and itching (455/703; 30.8%). Long-lasting erythema at the injection site was reported by 1,058 (71.7%) individuals, and persisted more than six months in 17% (107/1,058) of them (

Table 3).

The most common systemic adverse reactions were fatigue (60/107; 4.1%), muscle pain (47/107; 3.2%), and headache (41/107; 2.8%). Two serious adverse events were reported: one participant required hospitalization aimed at managing and monitoring fever and fatigue, and one participant, vaccinated with an unnoticed pregnancy, reported a neonatal death. Serious adverse events were notified to Bavarian Nordic, marketing authorization holder of the MVA-BN vaccine, for pharmacovigilance assessment. Narrative descriptions of the serious adverse events are provided in the Supplementary File 1. No deaths were reported among study participants.

4. Discussion

In this target trial emulation, with well-balanced groups in terms of mpox risk factors and extended follow-up, we observed a lower incidence rate of mpox among individuals vaccinated with MVA-BN; however, the limited number of events associated with the global decrease in mpox incidence during the study period prevented us from drawing definitive conclusions about the vaccine efficacy. Our exhaustive analysis of the vaccine safety confirmed the good safety profile of the MVA-BN vaccine when administered intradermally. Notably, long-lasting erythema at the injection site (referred by participants to as “persistent mark”), not commonly reported in other studies, was observed in approximately 70% of our cohort.

Our study is strengthened by the prospective design, with remarkably lengthy follow-up period, which has not been used among other target trial emulation studies investigating the efficacy of the MVA-BN vaccine [

15,

16,

18,

19,

20]. This feature has several implications. First, unlike target trial emulations relying on administrative data, which used mpox risk proxies such as STIs or HIV-PrEP use [

15,

16], we could define exhaustive eligibility and matching criteria based on known risk factors for mpox, such as chemsex practices or multiple sexual partners. Second, the collection of follow-up information on sexual behaviors for a remarkably long period showed that the prevalence of these risk factors remained balanced between groups throughout the study period. This finding suggests that, in our study cohort, vaccination did not prompt a relevant shift in risk behaviors following vaccination, a question that has remained open despite the cumulative evidence on mpox vaccine at the population level [

20]. Third, the prospective approach allowed us to recruit participants outside of healthcare centers, capturing more accurately the real-world scenario of vaccination campaigns. Notably, we observed significant differences between recruitment settings —for instance, a markedly higher proportion of unvaccinated individuals among those recruited via social media. This finding underscores the need to intensify efforts to reach the entire key population and achieve higher levels of vaccine coverage. Finally, the comprehensive data collection regarding vaccine safety allowed us to characterize the safety profile of the vaccine at a higher level than studies relying on administrative data, which are likely to collect only adverse events triggering a medical visit or intervention.

One of the distinctive features of the MVA-BN vaccination in the context of the 2022 outbreak was the administration route, which switched from subcutaneous to intradermal. Although intradermal administration has been associated with a higher rate of local and systemic adverse reactions than subcutaneous administration, these are usually mild and do not outweigh the benefits of vaccinating four times more population than would be achieved with subcutaneous vaccination [

7]. Our results confirmed the overall good safety profile of the MVA-BN vaccine (including the intradermal route) reported elsewhere [

21,

22]. Nevertheless, follow-up surveys for safety revealed the occurrence of a vaccination mark (erythema) in the administration area (i.e., typically the forearm) in more than half (70%) of the vaccinated participants. The erythema disappeared in less than 15 days in most of the cases, but persisted for more than 6 months in almost a third of them. This adverse reaction, barely reported in previous studies, could be associated with the administration route, as suggested by Frey et al.[

5]. In the context of a stigmatized infection like mpox, which primarily affects individuals facing social discrimination, an erythema perceived as a “persistent mark” might be a barrier for vaccine uptake. Therefore, administration in body locations less visible than the forearm, should be considered.

Despite the multiple advantages associated with the prospective approach, the use of patient-reported surveys for collecting health data can introduce biases in the study results [

23]. Among them, recall bias could have affected responses related to sexual behaviors within the past year and, most particularly, past smallpox vaccination. Likewise, social desirability bias (i.e., the tendency of respondents to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others) could have affected responses to questions related to sexual relationships with a person with mpox, engagement in chemsex or attendance to sex on premises venues. . Finally, the methodology used for survey delivery (i.e., based on internet and electronic devices) could have favored some population profiles.

In summary, while not conclusive, our study adds to the overall support to vaccination with MVA-BN as a preventive strategy for mpox in key populations. Vaccination with the intradermal route was overall safe, though social stigma potentially associated with a long-lasting erythema encourages exploring administration sites alternative to the forearm. In our cohort, vaccinated individuals did not exhibit a remarkable shift in sexual behaviors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Vaccination criteria in the participating countries, Table S1: List of participating sites, Table S2: List of independent Ethics Committees approving the study protocol, Table S3: Follow-up response according to sites, Narrative description of Serious Adverse Events, Composition of the REMAIN Study Group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S., R.E-S., C.G-C., M.M., and O.M.; methodology, C.S., R.E-S., C.G-C., D.O., A.A., C.C., M.M., and O.M.; software, R.E-S., and D.O.; formal analysis, D.O. and M.M.; investigation, C.G-C., E.M., A.G., M.W., A.A., H.S., S.H., D.B., L.C-E., C.S-F., J.C., A.M., A.R., V.D., E.O., H.M-R., L.M-B., C.C., A.A-A., and the REMAIN Study Group; data curation, C.S., R.E-S., D.O., M.M., O.M., writing resources and funding acquisition, O.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S., R.E-S., and O.M.; writing—review and editing, C.S., R.E-S., C.G-C., E.M., A.G., M.W., A.A., H.S., S.H., D.B., L.C-E., C.S-F., J.C., A.M., A.R., V.D., E.O., H.M-R., L.M-B., C.C., A.A-A., M.M., O.M., and the REMAIN Study Group.; Supervision and project administration, C.S., R.E-S., C.G-C., and O.M.; resources and funding acquisition, O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Bavarian Nordic, which provided general funding for overall study conduct. OM is supported by the European Research Council grant agreement number 850450 (European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, ERC-2019-STG funding scheme).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board or Independent Ethics Committee (IECs) in each participating country (

Table S2). In Spain the protocol was approved by the IEC of the Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital (code PI-22-228, approval 9th September 2020), in Panama by tue National Bioethics Research Committee (code EC-CNBI-2023-03-178, 25th April2023), in Peru by the IEC of the Arzobispo Loayza National Hospital (code 049-2022, 29th November 2022) and in Chile by the IEC of the Central Metropolitan Health Service (code 048975, 4th May 2023)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their dedication to the study. We also thank Gerard Carot-Sans for providing medical writing support, and Laia Bertran, Sergi Gavilan, and Miquel Angel Rodríguez for the operational and financial management of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

All authors attest that they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| EMA |

European Medicines Agency |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| HIV-PrEP |

HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| MPXV |

Monkeypox Virus |

| MVA-BN |

Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic |

| mpox |

Monkeypox |

| REDcap |

Research Electronic Data Capture |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SMD |

Standardized Mean Difference |

| STI |

Sexually Transmitted Infection |

References

- Mitjà O, Ogoina D, Titanji BK, Galvan C, Muyembe JJ, Marks M, et al. Monkeypox. The Lancet. Elsevier B.V.; 2023. p. 60–74.

- Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, Ubals M, Suñer C, Antón A, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2022;400:661–9. [CrossRef]

- Pittman PR, Hahn M, Lee HS, Koca C, Samy N, Schmidt D, et al. Phase 3 Efficacy Trial of Modified Vaccinia Ankara as a Vaccine against Smallpox. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381:1897–908. [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Emergency Task Force. Possible use of the vaccine Jynneos against infection by monkeypox virus [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/public-statement/possible-use-vaccine-jynneos-against-infection-monkeypox-virus_en.pdf.

- Frey SE, Goll JB, Beigel JH. Erythema and induration after mpox (JYNNEOS) vaccination revisited. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;388:1432–5. [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. EMA’s Emergency Task Force advises on intradermal use of Imvanex / Jynneos against monkeypox [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Mar 12]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/emas-emergency-task-force-advises-intradermal-use-imvanex-jynneos-against-monkeypox.

- Pang Y, Cao D, Zhu X, Long Q, Tian F, Long X, et al. Safety and Efficacy of the Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavaria Nordic Vaccine Against Mpox in the Real World: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Viral Immunol. 2024;37:216–9. [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh N, Yin S, Moir O, Danza P, Kim M, Finn L, et al. Effectiveness of JYNNEOS vaccine against symptomatic mpox disease in adult men in Los Angeles County, August 29, 2022 to January 1, 2023. Vaccine. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ramchandani MS, Berzkalns A, Cannon CA, Dombrowski JC, Brown E, Chow EJ, et al. Effectiveness of the Modified Vaccinia Ankara Vaccine Against Mpox in Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis, Seattle, Washington. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Brousseau N, Carazo S, Febriani Y, Padet L, Hegg-Deloye S, Cadieux G, et al. Single-dose Effectiveness of Mpox Vaccine in Quebec, Canada: Test-negative Design With and Without Adjustment for Self-reported Exposure Risk. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2024;78:461–9. [CrossRef]

- Sauer CM, Chen LC, Hyland SL, Girbes A, Elbers P, Celi LA. Leveraging electronic health records for data science: common pitfalls and how to avoid them. Lancet Digit Health. Elsevier Ltd; 2022. p. e893–8. [CrossRef]

- Scola G, Chis Ster A, Bean D, Pareek N, Emsley R, Landau S. Implementation of the trial emulation approach in medical research: a scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2023;23. [CrossRef]

- Matthews AA, Danaei G, Islam N, Kurth T. Target trial emulation: Applying principles of randomised trials to observational studies. The BMJ. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hernán MA, Wang W, Leaf DE. Target Trial Emulation: A Framework for Causal Inference from Observational Data. JAMA. 2022;328:2446–7. [CrossRef]

- Fontán-Vela M, Hernando V, Olmedo C, Coma E, Martínez M, Moreno-Perez D, et al. Effectiveness of Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavaria Nordic Vaccination in a Population at High Risk of Mpox: A Spanish Cohort Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2024;78:476–83. [CrossRef]

- Navarro C, Lau C, Buchan SA, Burchell AN, Nasreen S, Friedman L, et al. Effectiveness of modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic vaccine against mpox infection: emulation of a target trial. BMJ [Internet]. 2024;386:e078243. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39260880. [CrossRef]

- Ulm K. Simple method to calculate the confidence interval of a standardized mortality ratio (SMR). Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:373–5. [CrossRef]

- Rosen JB, Arciuolo RJ, Pathela P, Boyer CB, Baumgartner J, Latash J, et al. JYNNEOSTM effectiveness as post-exposure prophylaxis against mpox: Challenges using real-world outbreak data. Vaccine. 2024;42:548–55. [CrossRef]

- Mason LMK, Betancur E, Riera-Montes M, Lienert F, Scheele S. MVA-BN vaccine effectiveness: A systematic review of real-world evidence in outbreak settings. Vaccine [Internet]. 2024;42:126409. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0264410X24010910. [CrossRef]

- Pischel L, Martini BA, Yu N, Cacesse D, Tracy M, Kharbanda K, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of 3rd generation mpox vaccines against mpox and disease severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. Elsevier Ltd; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Deng L, Lopez LK, Glover C, Cashman P, Reynolds R, Macartney K, et al. Short-term Adverse Events Following Immunization With Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) Vaccine for Mpox. JAMA. 2023;329:2091. [CrossRef]

- Montalti M, Di Valerio Z, Angelini R, Bovolenta E, Castellazzi F, Cleva M, et al. Safety of Monkeypox Vaccine Using Active Surveillance, Two-Center Observational Study in Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11:1163. [CrossRef]

- Chang EM, Gillespie EF, Shaverdian N. Truthfulness in patient-reported outcomes: factors affecting patients’ responses and impact on data quality. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;Volume 10:171–86. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).