Introduction

Solid-liquid interfaces play a pivotal role in a variety of natural and industrial processes, governing phenomena such as adhesion, capillarity, wetting, self-assembly, and phase change heat transfer 1-5. These interactions are fundamental to the behavior of liquids on solid surfaces, influencing processes ranging from biological adhesion to fluid transport in engineered systems 6-11. Understanding these dynamics is critical for applications in fields such as microfluidics, advanced material deposition, and energy storage. Particularly, structured surfaces with micro- or nanoscale patterns, including grooves, have emerged as a focus of research due to their ability to direct fluid motion, manipulate wetting behavior, and enhance interfacial phenomena 12,13. Grooved surfaces, in particular, provide a simple yet powerful platform for controlling liquid spreading and capillary-driven flow. These surfaces enable precise manipulation of fluids, which is essential for applications requiring high spatial control, such as diagnostics, drug delivery, lab-on-a-chip devices, DNA manipulation, and microreactor operations 14-18. The study of liquid spreading on grooved substrates provides insights into the mechanisms underlying interfacial dynamics, including the effects of capillary forces, viscous resistance, and gravitational influences 12,19. Despite their practical significance, the detailed understanding of liquid behavior on grooved surfaces, particularly the formation and propagation of liquid filaments, remains incomplete. The unique combination of capillary confinement and gravitational effects on these structured surfaces warrants further investigation to uncover the underlying physical mechanisms.

The study of liquid filament formation and spreading on structured surfaces, including grooved substrates, has a rich and evolving history. Early foundational work centered on understanding capillarity-driven flows in simple geometries such as porous media and capillary tubes. Washburn’s classical equation 20, formulated in the early 20th century, laid the groundwork by describing the time-dependent imbibition of liquids into porous substrates. Subsequent studies extended these principles to microfluidic channels, thin films, and open channels 1,2,13,21. Over time, researchers recognized that introducing surface patterns—such as grooves or posts—could tailor liquid flow, fostering more complex phenomena including the formation of elongated liquid threads or filaments 22,23. During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, advances in microfabrication techniques enabled the systematic investigation of liquid spreading on micro- and nanostructured substrates. Early efforts focused on the role of surface topography in modifying wetting hysteresis and equilibrium contact angles 24,25. With the advent of soft lithography and improved photolithographic methods, grooved substrates with well-defined geometries became accessible, allowing detailed experiments on the behavior of droplets and menisci confined within periodic structures 26. These works demonstrated that groove depth, width, and spacing strongly affect the capillary forces acting on confined liquids, significantly influencing spreading speed and filament stability.

The concept of liquid filaments—thin, elongated fluid bodies extending within grooves—emerged as a focal point of research approximately two decades ago. Darhuber and Troian 27 highlighted how capillary forces guide fluid along grooves and channels, while subsequent studies by Bico and Quéré 28 underscored the interplay between roughness-induced capillarity and viscous dissipation. Early experiments showed that liquid filaments could act as transport conduits, facilitating directional fluid motion without external pumps or fields, a concept soon exploited for microfluidic applications 29,30. In these initial explorations, the fluids were typically low-viscosity and Newtonian, and the emphasis lay on understanding fundamental scaling laws and identifying conditions under which filaments remain stable or break into droplets 31,32. As the field matured, researchers began to consider more complex fluids and conditions. Studies by Herminghaus et al. 33,34 revealed that non-Newtonian fluids, surfactant-laden solutions, and liquids with varying viscosities and surface tensions can exhibit markedly different filament morphologies and spreading dynamics. Similarly, investigations into the influence of external fields—such as electrowetting 35,36 or thermal gradients 37—demonstrated that liquid filaments can be actively controlled, opening pathways for reconfigurable and adaptive microfluidic devices. More recently, attention has shifted towards understanding the fundamental mechanisms governing filament propagation when both capillarity and gravity are significant. Studies by Weislogel et al. 38,39 examined gravitational effects in open microchannels, while Ledesma-Aguilar et al. 40 investigated how gravitational leveling and hydrostatic pressure gradients modify filament shape and speed. These studies uncovered new regimes where gravitational and capillary forces jointly determine a non-trivial scaling law, differing from the canonical t1/2 or t1/3 relationships often found in low-viscosity or inertia-dominated systems.

Complementing experimental work, computational modeling and theoretical analyses have advanced our understanding of filament spreading. Lubrication theory, widely employed since the mid-20th century 41,42, has been adapted to patterned substrates, enabling analytical or semi-analytical predictions of filament shape and propagation rates 43. Numerical simulations using volume-of-fluid or level-set methods capture intricate interface dynamics, complex contact line motion, and the formation of multiple filaments within a single substrate 44,45. Such tools have shed light on how subtle changes in geometry or fluid properties can shift the balance of forces and alter the spreading kinetics. Despite these advances, the dynamic wetting process of high-surface-tension liquids with varying viscosities on grooved substrates remains incompletely understood.

To systematically and deeply understand this issue, this study systematically investigates the dynamics of liquid filament formation and propagation on grooved substrates with varying geometries. Using glycerol-water mixtures with controlled viscosities and surface tensions, we explore the interplay of viscosity, capillary forces, and groove geometry in determining filament behavior. The experiments focus on substrates with grooves of varying widths, examining the spreading of three glycerol-water solutions. This composition range enables a detailed analysis of how high-viscosity liquids with near-constant surface tensions respond to capillary confinement. The experimental findings are complemented by finite element simulations to model filament propagation under controlled conditions and theoretical analysis based on the lubrication equation. The combined approach reveals a consistent t4/5 scaling law for filament length versus time, reflecting the balance of capillary and gravitational forces in the long-time regime. The theoretical framework provides a robust explanation for the observed dynamics, linking the spreading rate to fundamental physical properties such as viscosity, surface tension, and groove geometry. This research contributes to the broader field of interfacial fluid dynamics by providing new insights into liquid filament behavior on structured surfaces. The findings have significant implications for designing grooved substrates for applications in microfluidics, material deposition, and surface engineering. By bridging experimental, computational, and theoretical approaches, this work advances our understanding of capillary-driven spreading and sets the stage for further exploration of more complex systems, including non-Newtonian fluids and hierarchical surface patterns.

Materials and Methods

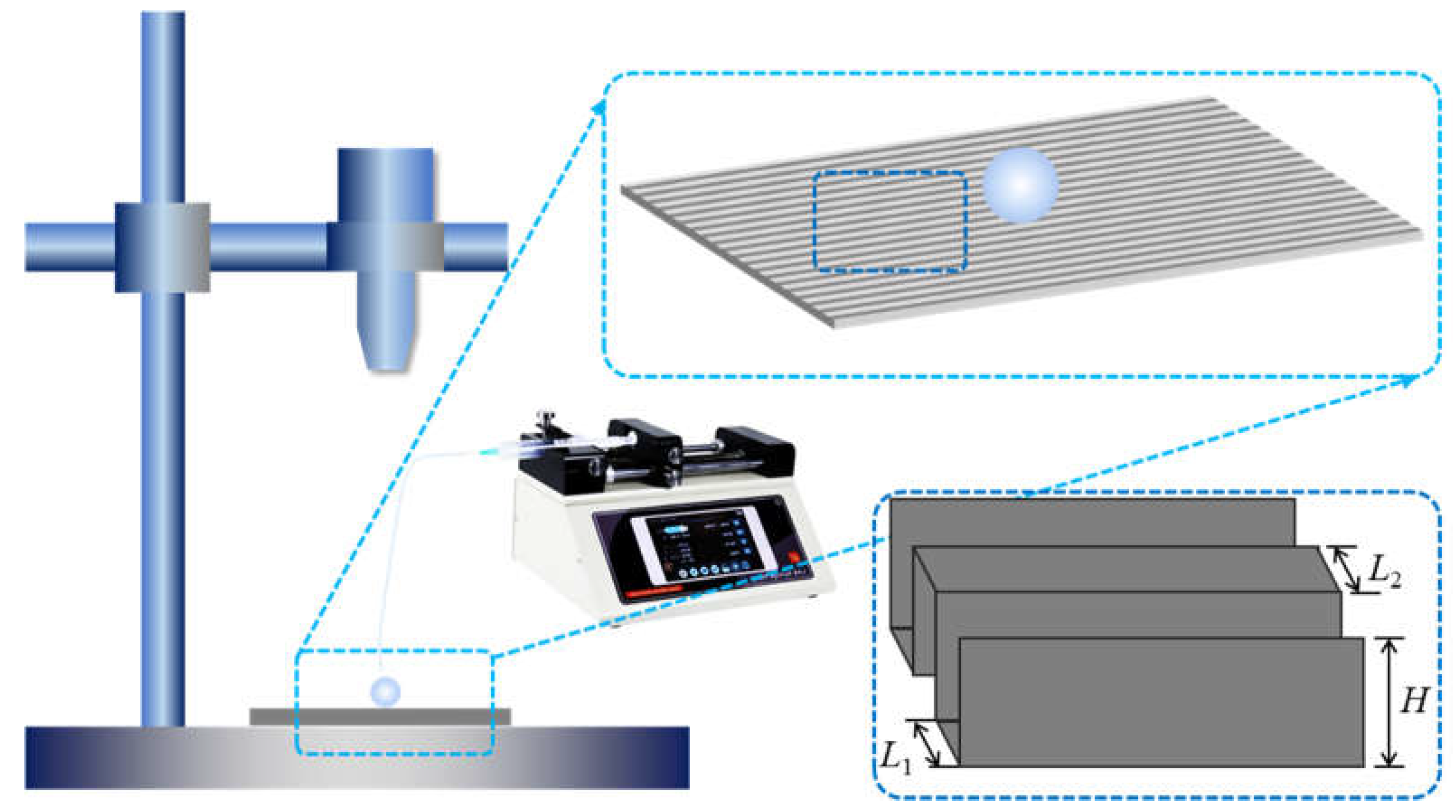

The patterned rectangular groove structures were fabricated on silicon wafers using a photolithographic process, a precise and widely adopted technique for microstructure fabrication. Preparation began by cleaning the silicon wafers using a standard RCA cleaning process to remove organic residues and particulate contaminants, ensuring a pristine surface for subsequent steps. The cleaned wafers were then dehydrated at 120°C on a hot plate for 10 minutes to eliminate moisture and improve photoresist adhesion. Next, a layer of SU-8 3025 photoresist was spin-coated onto the silicon wafers. The spin-coating process was performed in two stages: an initial spreading stage at 500 rpm for 10 seconds, followed by a high-speed stage at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds, achieving a uniform thickness corresponding to the desired groove depth of 15 µm. The coated wafers were then subjected to a soft bake on a hot plate at 65°C for 2 minutes, followed by 95°C for 5 minutes, to partially cure the photoresist and remove any residual solvents. The groove patterns were defined using a photomask and ultraviolet (UV) exposure. A photomask with designed groove patterns, including equal-width grooves (8 µm, 16 µm, and 32 µm) and variable-width grooves (ranging from 8 µm to 24 µm, with 2 µm intervals), was aligned with the photoresist-coated wafer. The UV exposure was carried out using a mask aligner, with an exposure dose of 70 mJ/cm² to ensure complete polymerization of the exposed regions. After exposure, the wafers underwent a post-exposure bake (PEB) at 65°C for 1 minute and 95°C for 3 minutes to enhance cross-linking in the exposed areas. The unexposed photoresist was then removed by developing the wafers in SU-8 developer for 3-5 minutes, followed by thorough rinsing with isopropanol to stop the development process. The wafers were dried using a nitrogen gun.

To finalize the fabrication, the wafers were subjected to hard baking at 150°C for 10 minutes, stabilizing the SU-8 structures and ensuring mechanical robustness. This process resulted in highly uniform and reproducible rectangular groove patterns with sharp edges and consistent depths. Two types of structures were prepared: equal-width grooves with widths of 8 µm, 16 µm, and 32 µm, and variable-width grooves ranging from 8 µm to 24 µm, as illustrated in

Figure 1, where

L1 represents the groove width,

L2 the groove interval, and

H the groove depth.

Table 1 and

Table 2 provide detailed summaries of the groove dimensions, including width, interval, depth, and surface roughness. The surface roughness,

RA, which was defined as the ratio of the apparent surface area to the actual surface area, calculated as

RA =

L1/(2

H+

L1). This parameter characterizes the extent of surface structuring and its impact on interfacial phenomena, enabling precise investigation of liquid filament dynamics on the fabricated surfaces.

The liquid mixtures used in the experiments were prepared by mixing glycerol (G) and deionized water (W) in different volume ratios to achieve a range of viscosities and surface tensions. Three compositions were selected: pure glycerol (G

100W

0), glycerol-water mixtures with ratios of 70:30 (G

70W

30), and 50:50 (G

50W

50), representing high, medium, and low viscosities, respectively. The physical properties of these mixtures, including density, viscosity, surface tension, and static contact angles on the SU-8 photoresist substrate, are detailed in

Table 3. The contact angle measurements were performed using a contact angle goniometer to ensure accuracy and reliability. These properties provide critical insights into the behavior of the liquid filaments during the spreading process. Droplets were dispensed using a precision syringe pump (produced by Baoding Dirui Company), which allowed precise control over the volume of liquid deposited onto the structured SU-8 substrates. The droplets were dispensed through a fine-tipped needle to minimize initial impact and ensure consistent deposition. The spreading behavior of the droplets was recorded using an industrial-grade camera operating at a frame rate of 60 frames per second. The high frame rate enabled the detailed capture of the dynamic spreading process, including the formation and propagation of liquid filaments within the microgroove structures.

All experiments were conducted at a controlled room temperature of 25°C to minimize environmental variations that might affect the spreading behavior. The structured substrates were placed on a horizontal platform to ensure uniform conditions for liquid spreading. The liquid filament length and its progression over time were analyzed using motion detection software (VL 3.0). Each video was processed frame by frame, and the filament length was measured manually or using edge-detection algorithms within the software to ensure consistent and accurate data collection. The chosen glycerol-water mixtures represent a range of fluid viscosities, enabling a comprehensive investigation into how viscosity and surface tension influence the dynamics of liquid filament propagation. High-viscosity fluids (G100W0) provided insights into cases dominated by viscous forces, while lower viscosity mixtures (G50W50) allowed exploration of capillary-dominated regimes. By systematically varying the liquid composition and monitoring the spreading process, this study aimed to elucidate the interplay of viscosity, surface tension, and microstructure geometry in governing the dynamics of liquid filaments on patterned surfaces.

G: glycerol; W: DI water; G100W0 represents 100% glycerol and 0% DI water.

Results and Discussions

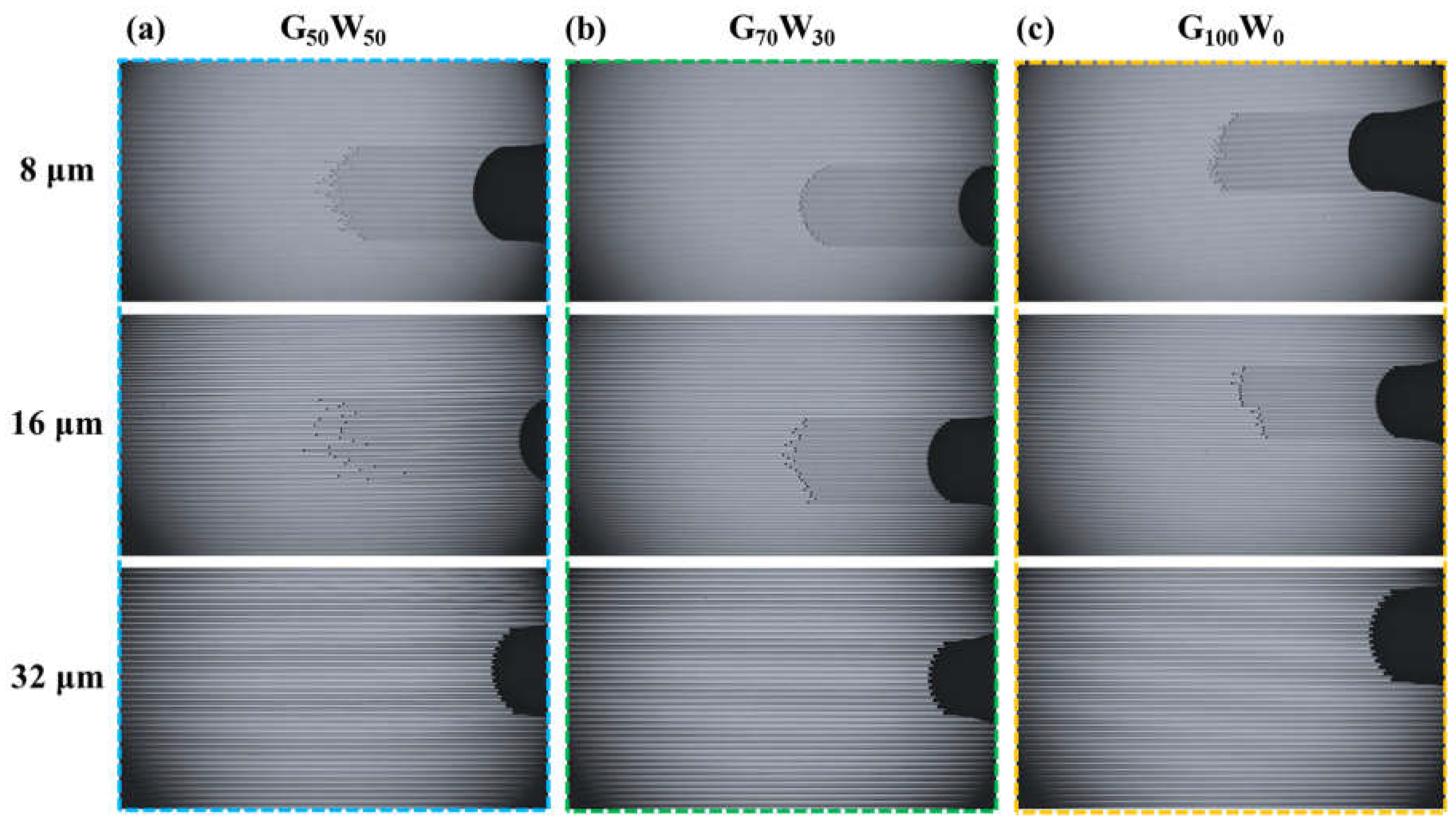

Figure 2 presents the experimental observations and analyses of wetting and spreading behaviors of three glycerol-water mixtures (G

50W

50, G

70W

30, and G

100W

0) on SU-8 photoresist substrates with varying groove widths. The three liquids represent different viscosities while maintaining similar surface tensions, allowing for a focused investigation of viscosity's role in the propagation of liquid filaments under comparable capillary conditions. The static contact angles of the three liquids on the SU-8 surface are depicted. DI water (surface tension 72 mN/m) exhibits a contact angle of 82°, while the contact angles for G

50W

50, G

70W

30, and G

100W

0 are 76°, 73°, and 57°, respectively. This slight decrease in contact angle correlates with the increase in glycerol content, as the surface tension of glycerol (64 mN/m) is lower than that of water. Despite these small differences in contact angle and surface tension, the viscosities of the three mixtures vary significantly, from 6 mPa·s for G

50W

50 to 1410 mPa·s for G

100W

0. This viscosity range enables a systematic comparison of spreading dynamics on grooved substrates, especially under high surface tension and similar capillary driving forces.

Figure 2 illustrates the spreading behavior of the three liquids (G50W50 (

Figure 2a), G70W30 (

Figure 2b) and G100W0 (

Figure 2c)) within grooves of varying widths (8 µm, 16 µm, and 32 µm). Each row corresponds to a specific groove width, with the first row representing 8 µm grooves, the second row 16 µm grooves, and the third row 32 µm grooves. At the narrowest groove width of 8 µm, all three liquids exhibit liquid filament formation and propagation, irrespective of viscosity. This observation indicates that the narrow grooves provide sufficient capillary confinement to sustain liquid filament formation.

For grooves with a width of 16 µm, liquid filaments are still observed for all three liquids, albeit with slight differences in filament stability and propagation dynamics. The increased groove width reduces the degree of confinement, but the capillary forces remain sufficient to sustain filament formation. At the widest groove width of 32 µm, liquid filaments no longer form for any of the three liquids. Instead, the liquids spread along the groove base without the distinct filament morphology observed at narrower groove widths. This transition suggests that as the groove width increases, the capillary confinement diminishes, and the balance between capillary forces and gravitational forces shifts, ultimately inhibiting liquid filament formation. The roughness coefficients (RA) of the three groove widths are 1.358, 1.215, and 1.028, respectively. According to classical wetting theory, the equilibrium contact angle’s cosine value is proportional to the roughness coefficient. According to the theory of energy minimization, for a liquid progression in the groove by a quantity dx, the surface energies change by an amount (ignoring gravity effects) dE = (γsl-γsv)(2H+L1)dx+γlvL1dx. Using the Young equation, the liquid progression is favorable when θ < θc, with cosθc = L1/(2H+L1). For the three surfaces, the equilibrium contact angles were calculated as 77.8°, 69.6°, and 58.9°, respectively. The experimental static contact angles of the droplets (76.2°, 68.3°, and 57.5°) are consistently larger than the calculated equilibrium angles, indicating that the spreading and filament formation process involves an additional driving force beyond the capillary forces predicted by classical theory. This additional traction likely results from the hemi-capillary force at the groove edges, which enhances filament propagation even at higher contact angles. These results demonstrate that groove width and liquid viscosity play critical roles in liquid filament formation and propagation. While narrow grooves consistently facilitate filament formation, wider grooves fail to sustain capillary-driven confinement, especially for high-viscosity liquids. This study highlights the intricate interplay of capillary forces, groove geometry, and liquid properties in determining the dynamics of liquid filament propagation on structured surfaces.

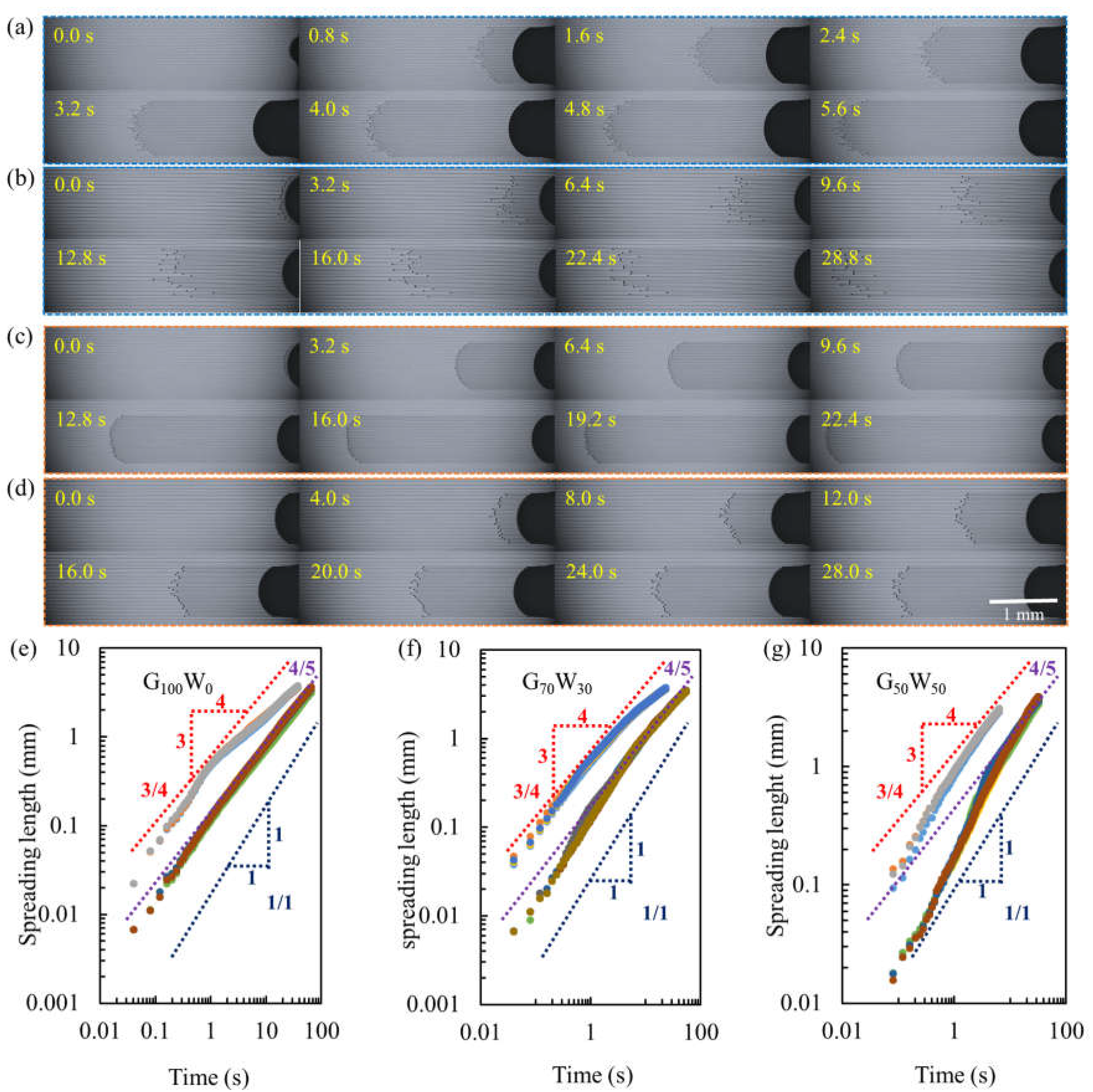

Figure 3 illustrates the dynamic wetting and spreading behavior of three glycerol-water mixtures (G

50W

50, G

70W

30, and G

100W

0) within grooved substrates of varying widths (8 µm and 16 µm). The experiments capture the progression of liquid filament propagation, highlighting the effects of groove width and liquid viscosity on the spreading dynamics.

Figure 3a,b depict the spreading process of G

50W

50 in grooves with widths of 8 µm and 16 µm, respectively. In the 8 µm-wide grooves (

Figure 3a), the liquid filament propagates approximately 3 mm in length within 5.6 seconds, indicating a rapid spreading process facilitated by the narrow groove's strong capillary confinement. In contrast, for the 16 µm-wide grooves (

Figure 3b), the same 3 mm propagation length is achieved in 28.8 seconds, nearly five times slower than in the narrower grooves. This stark difference underscores the critical role of groove width in influencing the spreading speed, as wider grooves reduce capillary confinement and thereby decrease the driving force for filament propagation. The same trend is observed for G

70W

30, as shown in Figures 3c and 3d. In the 8 µm-wide grooves (

Figure 3c), the filament propagates approximately 3 mm within 22.4 seconds, whereas in the 16 µm-wide grooves (

Figure 3d), the filament length is less than 2 mm even after 28 seconds. These results further confirm that increased groove width slows filament propagation, likely due to diminished hemi-capillary forces and the greater dominance of viscous resistance in wider grooves. Additionally, the comparisons between G

50W

50 and G

70W

30 demonstrate that higher viscosity results in slower filament propagation, as viscosity inversely correlates with velocity under a constant driving force.

Figure 3e,f,g present the relationships between filament length and time for G

100W

0, G

70W

30, and G

50W

50, respectively, using logarithmic coordinates. For the high-viscosity G

100W

0 solution (

Figure 3e), the spreading follows a

l~t4/5 scaling law after an initial phase of rapid spreading. The early-stage faster propagation suggests that gravitational forces play a significant role initially, accelerating the liquid flow. This observation is consistent across all three solutions, as seen in Figs. 3f and 3g, where initial spreading speeds are higher before stabilizing into the 4/5-power scaling relationship.

The decreasing viscosity of the solutions (from G100W0 to G50W50) amplifies the influence of gravity during the initial spreading phase, extending the duration of rapid propagation. However, as the spreading stabilizes, the scaling law converges to the 4/5-power relationship for all solutions. This consistent scaling behavior suggests that the interplay of capillary and viscous forces governs the long-term propagation of liquid filaments, while gravitational effects primarily influence the initial stages. These results highlight the complex dynamics of liquid filament spreading in grooved substrates. Narrower grooves enhance capillary confinement, facilitating faster filament propagation, while higher viscosities dampen spreading speed by increasing viscous resistance. The consistent 4/5-power scaling observed in the stabilized phase underscores the dominance of capillary-driven dynamics under these conditions, providing a robust framework for understanding liquid filament propagation in structured microenvironments.

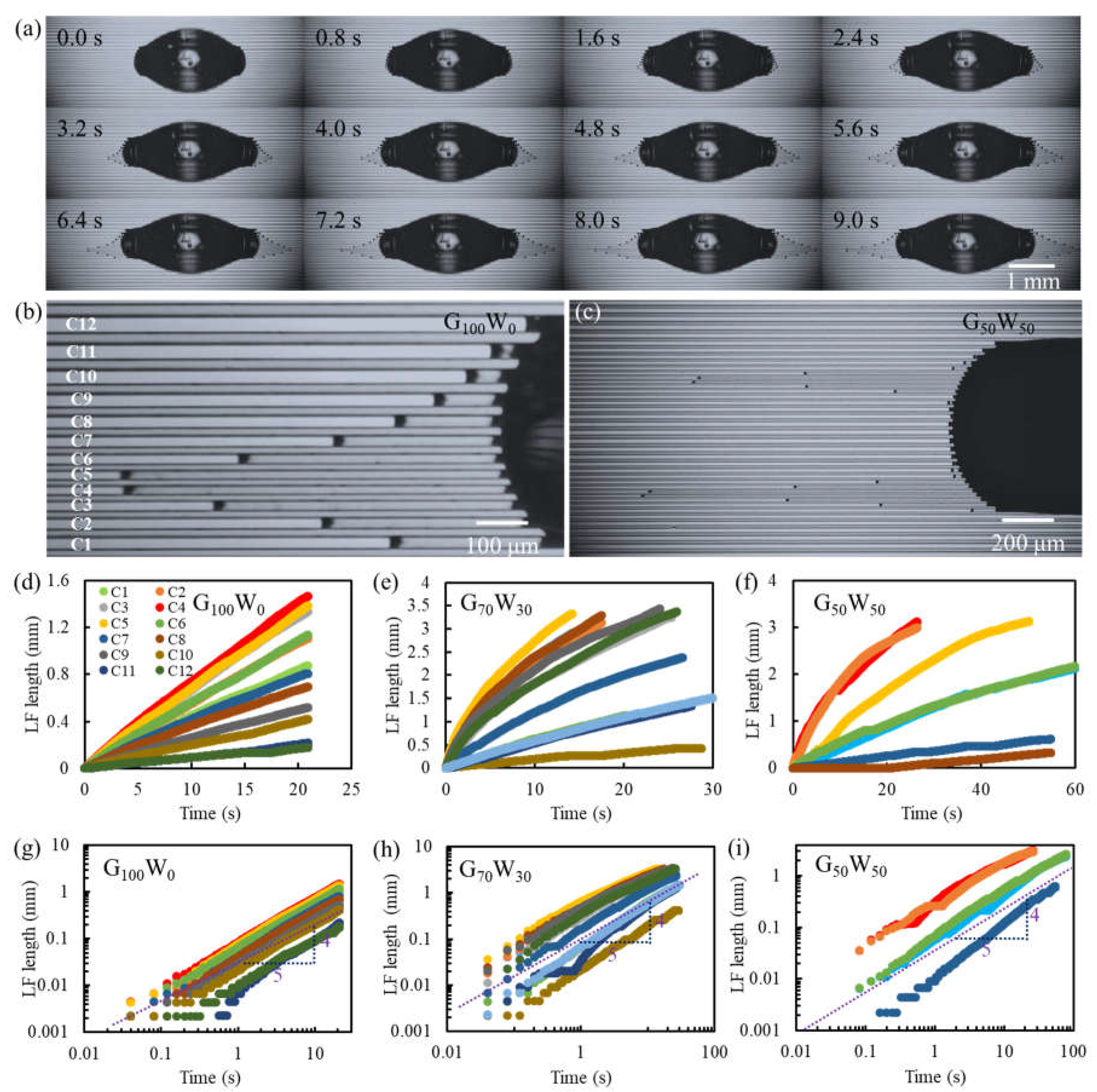

The dynamic wetting and spreading behavior of three glycerol-water mixtures (G

100W

0, G

70W

30, and G

50W

50) on substrates with gradient groove width structures were explored in

Figure 4. The grooves have widths ranging from 8 µm to 24 µm, increasing in 2 µm increments, with a constant depth of 15 µm. The groove parameters are detailed in

Table 2. These gradient substrates facilitate a systematic investigation of how varying groove widths influence liquid filament formation and propagation.

Figure 4a depicts the spreading progression of a 5 µL G

100W

0 droplet from 0 to 9 seconds. In the initial 0.8 seconds, no liquid filament is observed; however, by 1.6 seconds, a filament begins to form at the droplet's leading edge. Over time, the filament propagates farther, reaching a maximum length of approximately 1 mm within 9 seconds. This result highlights the delayed onset of filament formation due to the high viscosity of G

100W

0, which slows the initial capillary-driven motion. The gradient grooves significantly affect filament length. Narrower grooves produce longer filaments, while filaments in wider grooves exhibit reduced propagation lengths. This gradient effect becomes increasingly pronounced over time, demonstrating a clear relationship between groove width and filament spreading dynamics.

Figure 4b provides a magnified view of the filament formation for G

100W

0, with 12 grooves labeled C1 to C12, corresponding to widths ranging from 8 µm to 24 µm. The differences in filament length across the grooves are apparent, with the longest filaments observed in the narrowest grooves (C1 and C2).

Figure 4c,b compare the filament formation for G

50W

50 and G

100W

0. The G

50W

50 droplet exhibits more pronounced variations in filament length across grooves. The reduced viscosity of G

50W

50 enhances the influence of groove width on filament propagation, leading to a sharper gradient effect. The narrower grooves produce significantly longer filaments than the wider grooves, underscoring the interplay between viscosity and capillary confinement in determining filament length.

Figure 4d–f show the filament length as a function of time for the three solutions (G

100W

0, G

70W

30, and G

50W

50) across the 12 gradient grooves. In

Figure 4d, the G

100W

0 filament length increases approximately linearly with time during the first 20 seconds. The fastest spreading is observed in C4 and C5, corresponding to the narrowest grooves. This linear spreading behavior reflects the dominant role of viscous forces in high-viscosity fluids, where capillary forces are modulated by the groove geometry.

Figure 4e illustrates the spreading dynamics for G

70W

30. The filament initially propagates rapidly but slows down as it elongates, reaching a length of approximately 3 mm within 20 seconds in the narrowest grooves. This deceleration is consistent with the increasing viscous resistance as the filament grows longer, and the dynamics indicate a shift from gravity-influenced motion in the initial phase to capillary-dominated spreading over time.

Figure 4f shows the spreading behavior of G

50W

50. Similar to G70W30, the filament propagation initially exhibits rapid motion, followed by a gradual deceleration. The reduced viscosity of G

50W

50 amplifies the influence of capillary forces, resulting in longer filaments compared to G

100W

0 and G

70W

30 for the same groove width.

Figure 4g–i present the filament length versus time in logarithmic coordinates for G

100W

0, G

70W

30, and G

50W

50, respectively. Across all three solutions, the filament length scales with time as

l ~ t4/5. This scaling behavior is consistent for all groove widths, indicating that the capillary forces, modulated by viscosity and groove geometry, dominate the spreading dynamics in the stabilized phase. For the higher-viscosity G

100W

0, the initial gravitational influence is minimal, resulting in a nearly uniform 4/5-power scaling across the grooves. In contrast, for G

70W

30 and G

50W

50, gravitational effects are more pronounced in the early stages, accelerating filament formation before transitioning to the 4/5-power scaling as viscous and capillary forces balance. These results reveal the complex interplay of groove geometry, viscosity, and capillary forces in liquid filament formation and propagation. Narrow grooves and lower viscosity enhance filament propagation, while wider grooves and higher viscosity limit the filament length. The 4/5-power scaling provides a robust framework for predicting filament dynamics across various groove and liquid parameters, offering valuable insights for applications requiring precise fluid manipulation in structured surfaces.

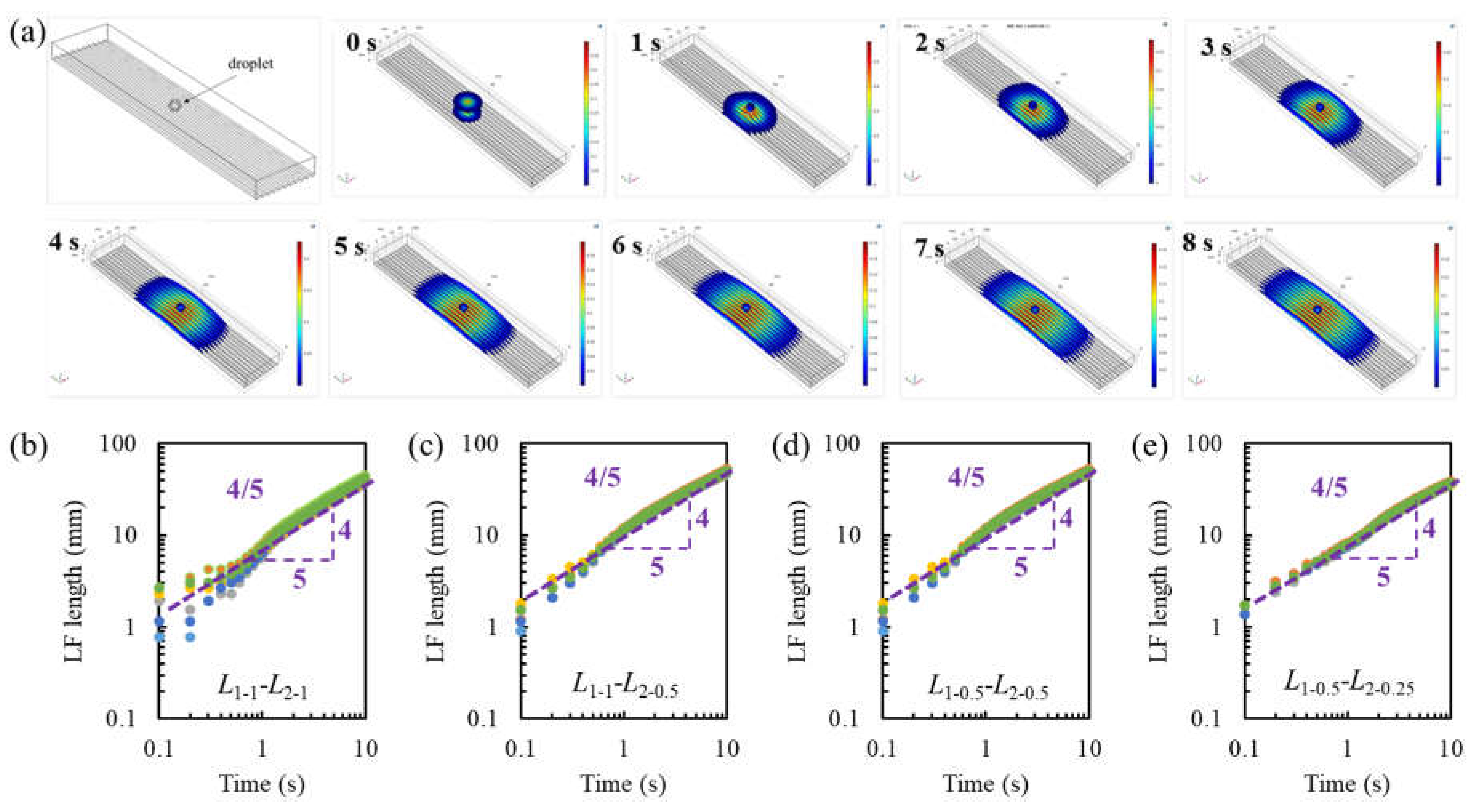

To complement the experimental observations, finite element method (FEM) simulations were conducted to analyze the dynamics of liquid filament spreading on grooved substrates. The simulation model is illustrated in

Figure 5a (first panel), depicting a structured substrate with grooves of varying widths and depths. The simulations employed a two-phase flow model based on the Navier-Stokes equations, incorporating capillary forces, viscous effects, and gravitational forces to replicate the experimental conditions accurately. The simulated liquid was modeled using a Newtonian fluid with properties corresponding to G

100W

0. The density (

ρ) and dynamic viscosity (

η) were set to 1.26 g/cm³ and 1410 mPa·s, respectively, while the surface tension (

γ) was 64 mN/m. The contact angle on the grooved substrate was set to 85°, consistent with experimental measurements for G

100W

0 on SU-8. The grooved substrate's geometries were defined as

L1-

L2-

H structures, where

L1 represents the groove width,

L2 the groove spacing, and H the groove depth. The depth (

H) was fixed at 15 µm, while

L1 and

L2 were varied based on the groove dimensions described in

Table 2. The computational domain was discretized using a structured mesh with finer elements near the liquid-groove interface to capture the details of filament dynamics. Time-dependent simulations were performed using a volume-of-fluid (VOF) method to track the liquid-gas interface, and a no-slip boundary condition was applied to all solid surfaces. The simulations were initialized with a droplet of 5 µL volume placed symmetrically on the substrate, with the spreading process simulated up to 8 seconds at 1-second intervals.

Figure 5a (second to last panels) shows the simulated time sequence of liquid filament spreading on the substrate from 0 s to 8 s. Initially, the droplet spreads radially without filament formation. By 1 s, a filament begins to form at the groove's leading edge, and its length progressively increases over time. At 8 s, the filament achieves a maximum length, closely matching the experimental results. Figs. 5b–5e illustrate the simulated filament front position as a function of time for different substrate geometries, all plotted on logarithmic scales. Each panel corresponds to a specific configuration:

Figure 5b:

L1-1−

L2-1 (16 µm groove width and spacing) shows a smooth progression of filament length with a clear

t4/5 scaling law after the initial transient phase.

Figure 5c:

L1-1−

L2-0.5 (16 µm groove width, 8 µm spacing) exhibits a similar scaling behavior but with a faster spreading rate due to the reduced spacing, which enhances capillary confinement.

Figure 5d:

L1-0.5−

L2-0.5 (8 µm groove width and spacing) demonstrates the fastest spreading dynamics among all configurations, with the narrow grooves providing the strongest capillary driving forces.

Figure 5e:

L1-0.5−

L2-0.25 (8 µm groove width, 4 µm spacing) further enhances confinement, resulting in a slightly faster initial spreading phase before stabilizing to the

t4/5 scaling. Across all geometries, the filament length's scaling behavior adheres to the

t4/5 power law observed experimentally. The initial phase of spreading is influenced by gravity, as indicated by a slightly faster spreading rate, but this effect diminishes over time as capillary and viscous forces dominate. Narrower grooves and smaller spacing enhance capillary confinement, resulting in faster and more uniform filament propagation.

The FEM simulations corroborate the experimental findings, reinforcing the critical role of groove geometry in determining filament propagation dynamics. The consistent t4/5 scaling across all geometries highlights the universal nature of capillary-driven spreading in structured substrates. Additionally, the simulations provide insights into the transient phase dominated by gravitational forces, particularly for high-viscosity fluids like G100W0. The ability to predict filament dynamics through FEM modeling offers valuable opportunities for optimizing grooved substrates in applications requiring precise fluid control, such as microfluidics and surface patterning. These results also emphasize the importance of groove width and spacing as tunable parameters for engineering liquid behavior on structured surfaces.

To analyze the spreading behavior of the droplet under the simultaneous effects of capillarity and gravity at long timescales, the lubrication equation is employed. The governing equation for the film thickness

h(

x,

t) in one dimension, based on the lubrication approximation, is expressed as:

where,

μ is the dynamic viscosity,

γ is the surface tension,

ρ is the density of the liquid, and

g is the gravitational acceleration. The evolution of the spreading length

l(

t) is of interest, and it is hypothesized that a self-similar solution exists in the long-time regime. To explore this possibility, the film thickness

h(

x,

t) is assumed to take the following self-similar form:

where,

. Here,

α and

β are scaling exponents to be determined, and

f(

ξ) is a dimensionless profile function that describes the shape of the spreading liquid. The spreading length is related to

ξf, the front position in the dimensionless coordinates, as

l(

t) =

ξf tβ.

Substituting the self-similar form into the lubrication equation, the time derivative becomes:

while spatial derivatives transform as:

Substituting into

q, the flux becomes:

Taking the divergence of q, we have:

Balancing terms with matching powers of t, the scaling exponents must satisfy: α−1 = 4α−4β (capillarity term balance), α−1 = 4α−2β (gravity term balance).

Additionally, the volume conservation condition requires:

from these conditions, solving the system of equations yields:

β = 4/5,

α = −4/5.

Boundary and Far-Field Conditions:

To ensure a physically consistent solution, boundary and far-field conditions must also be satisfied:

At the spreading front x = l(t), the thickness vanishes, h(l(t), t) = 0. This imposes f(ξf) = 0.

In the far field (x→0), the thickness profile h(x, t) must remain finite or decay appropriately to satisfy volume conservation and ensure no unphysical singularities. This translates to requiring a smooth and finite f(ξ) as ξ→0.

These conditions lead to a unique solution for the self-similar function f(ξ), confirming that the spreading length follows the scaling law: l(t) ∼ t4/5. The 4/5 scaling law reflects the combined influence of capillarity and gravity on the spreading process. At long times, capillarity drives the spreading by pulling the liquid into the surrounding regions, while gravity counteracts this motion by generating a retarding hydrostatic pressure gradient. The balance between these forces determines the rate of spreading, captured by the 4/5 exponent. This result is consistent with observations in systems where spreading is influenced by both surface tension and gravity, such as droplet spreading on structured or inclined surfaces. The derived scaling law is robust and provides a fundamental understanding of the interplay between capillarity and gravity in thin-film flows.