1. Introduction

The issue of using concrete with lightweight sintered aggregate (LSA) for prestressed concrete structures has been the subject of the works by many authors in recent years. Basically, lightweight concretes constitute a group of materials with different properties. Thanks to the use of light concrete with sintered aggregate as a material that guarantees the reduction of the dead weight of the structure while maintaining the required strength properties of concrete, it turns out that in prestressed structures, an additional capacity and deflection reserve is obtained. Due to its properties, lightweight aggregate concrete (LWAC) has been widely applied in the construction industry, including high-rise buildings, prefabricated structures, bridges and oil platforms.

However, lightweight aggregate concrete is still a problematic material for use in construction. Currently, there are not many standards for testing lightweight concrete. There is little knowledge about such materials, and the lack of research discourages designers from using them in projects. Therefore, reliable testing of the rheological properties of the concrete under consideration is a prerequisite for these new applications.

The main raw material for aggregate production is the ash from the combustion of hard coal in fine coal boilers [

1] in power plants. As a result, the final product comes from recycling ashes, which provides a granulate from which the aggregate is produced after processing. As a recycled product, it can be considered environmentally friendly. In addition, the sintering process makes the aggregate less absorbent and frost-resistant. Lightweight aggregate with high strength is manufactured according to domestic technology. It is created as a result of high-temperature sintering (1000–1200 °C) of properly prepared anthropogenic minerals under controlled conditions, followed by fractionation and possibly crushing. The sintered aggregate and the fresh concrete mix with this aggregate are shown in

Figure 1. Since lightweight concretes are a group of materials with various properties, their mechanical behavior requires careful verification. Lightweight concretes are characterized by greater structural homogeneity than plain concretes, resulting from the tight construction of the contact zone between the grout and aggregate. This ensures, among others, the regular grain shape of artificial aggregates.

Due to the different structures, lightweight concretes usually behave differently under the load and show a different failure mechanism compared to plain concretes. The tests [

2] showed that for concretes with aggregate made of ashes, the straight-line course of the

σ −

ε relationship reaches up to 90 % of the ultimate stress. In concretes with lightweight aggregate, the high elastic energy stored by them during the loading causes rapid propagation of cracks, which irreversibly leads to sudden destruction of the material. However, the first load cracks appear only when the load-bearing capacity is exhausted about 85 −90 %. In the case of plain concretes, the destruction usually occurs in the contact zone of the aggregate with the grout. In lightweight concretes, the failure crack usually runs through the aggregate because in these concretes, the aggregate is the weakest element of the composite structure. Therefore, lightweight concretes are more brittle. With the same proportions of the components of the mix of plain and lightweight concrete, in the case of lightweight concrete, an increased cement class is required to obtain the same strength class. In the case of lightweight concrete, the strength is influenced by the same properties as in the case of plain concrete, i.e. W/C ratio, cement content and age of the concrete. Nevertheless, due to the high absorption of mixing water by the aggregate, it is difficult to estimate the total effect of the W/C ratio on the value of concrete compressive strength. The Young's modulus of concrete, which is a two-component composite, depends on the parameters of both the aggregate and the grout, their volumetric shares and mutual adhesion. Due to the lower density compared to plain concrete, lightweight concrete is also characterized by a lower secant modulus of elasticity.

Significant publications and monographs on the properties of concrete with lightweight sintered aggregate of the considered type, resulting from research conducted, among others, by the IMiKB laboratory of the Cracow University of Technology, have been published since 2016 [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The purpose of these tests has been to determine the mechanical properties of concrete, i.e. the compressive strength, tensile strength and modulus of elasticity, as well as to determine the development of the shrinkage and creep of concrete. The results of these tests show that relatively high compressive strength of concrete can be obtained without much difficulty, so it can be used in prestressed structures. The results of these tests also indicate a low creep coefficient of lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate. The works by Szydłowski et al. [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] are an important contribution to the basics of designing prestressed concrete structures made with the use of lightweight sintered aggregate. The monograph [

2] presents the state-of-the-art for structural lightweight concretes. The main part of this monograph is a description of structural lightweight concrete properties with respect to their complex modelling. The work also discusses the possibility of modification of lightweight concrete properties with admixtures, additives, polymers, and fibers. The article by Małaszkiewicz and Jastrzębski [

17] presents the research results assessing the possibility of making lightweight self-compacting concrete from local sintered fly-ash aggregate. Previously, Kaszyńska and Zieliński [

18] studied the effect of lightweight aggregate on minimizing autogenous shrinkage of self-consolidating concrete.

The influence of various properties of lightweight aggregates (physical, chemical, etc.) on the mechanical properties of concrete made using these aggregates has been described based on extensive experimental studies, among others, in the works [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Shrinkage phenomena of LWAC concrete, including shrinkage cracks, were analyzed in a number of papers, including [

24,

25], and [

26], and the phenomenon of early thermal-shrinkage stresses resulting from the release of hydration heat during the setting process of LWAC concretes was analyzed in the works [

27,

28,

29]. The simultaneous creep and shrinkage action on LWAC concrete has also been the subject of several works, including [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. A number of physicochemical analyses of LWAC concrete with aggregate produced according to the LSA technology, along with comparisons in the scope of applications of other lightweight artificial aggregates, were conducted by researchers from the Białystok University of Technology (cf. works [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]), the Wrocław University of Sci. and Technology and Warsaw University of Technology in Płock (cf. [

44]) and also LSA (cf. works [

45,

46,

47]). Extensive studies of floor elements made using LWAC concretes with the discussed aggregate were conducted by scientists from the Łódź University of Technology under the supervision of Urban (cf. works [48−53]). Experimental investigations conducted at the Łódź University of Technology cover a wide range of issues regarding the punching shear of flat slabs made of concrete with sintered aggregate [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

The ITB Laboratory conducted research on various mechanical properties of lightweight concretes with sintered aggregate [

54,

55], which concerned two kinds of concrete mixtures, due to equipment limitations. There are many extensive publications on concretes with lightweight aggregates, including a monograph [

56]. This monograph presents in detail the properties of aggregates and concretes based on ash aggregates and lightweight concretes. Around the world, these materials are appreciated by both scientists and designers.

For this purpose, in the ITB Laboratory of Building Structures, Geotechnics and Concrete, regardless of the conducted research on the short-term strength properties of the considered lightweight concrete, the tests were carried out to determine the rheological properties of long-term shrinkage and creep of concrete. A program was developed to test the strength parameters and mechanical properties of lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate at appropriately selected parameters of the concrete mix. The tests were planned for two types of concrete, assuming mixtures analogous to those used in the works cited above [

9,

13]. Such robust experimental results are very important for structural design. Knowledge of the discussed parameters is essential for the design of complex engineering structures in accordance with current standards and, in particular, for the adoption of proven values for the static calculation of prestressed lightweight concrete elements.

2. Materials and Methods—Research Program

2.1. Materials for Concrete Mixes

The scope of work covers the determination of long-term mechanical properties of 2 lightweight concrete mixtures with a special ceramic, sintered aggregate. Two concrete mixes with a water-cement ratio (W/C) of 0.4 and 0.5, respectively, were made, using the components adopted in accordance with

Table 1 (see below). The mixes were prepared in the same way as in the work [

9]. As a result of the tests, the compressive and tensile strength of the concrete, the secant modulus of elasticity as well as the creep and shrinkage strains were determined.

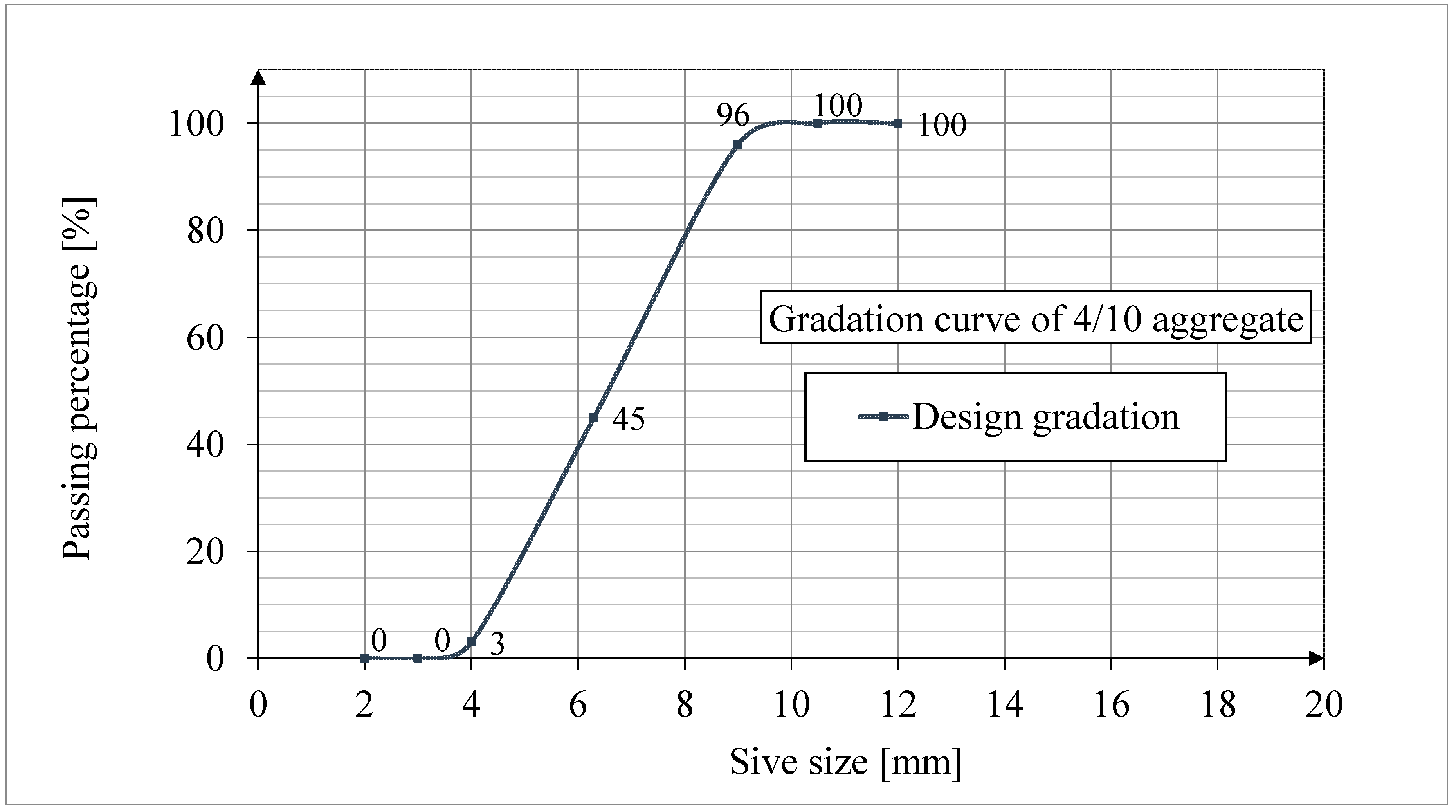

2.2. Characteristics of the Aggregate Used for Lightweight Concrete

The aggregate used is a type of crushed aggregate with a fraction of 4/10. The manufacturer determined the percentage composition of the aggregate fraction by the screening method before it was allowed for testing. 96% was a fraction less than 9 mm, 45% was less than 6.3 mm, and the fraction less than 4 mm was 3%. The dust content was 0.6%. In addition, the manufacturer provided the following information on the aggregate prepared for testing: bulk density: 654.9 kg/m3, crushing value: 6.5 MPa, water absorption: 18.4% after 24 hours, grain density: 1417 kg/m3. The design gradation curve of the 4/10 aggregate is shown in

Figure 2.

2.3. Concrete Mixes

Two concrete mixes, LC1 and LC2, were prepared in the same way as in the paper [

9].

Table 1 (given above) shows the recipe for the two types of concrete mixes used. The characteristics of fresh mixes are presented in

Table 2.

After 28 days of curing, the concrete density was determined to be 1766 kg/m3 for dried concrete marked LC1 and 1777 kg/m3 for concrete marked LC2 according to [

61].

2.4. Methods of Tests and Corresponding Samples

The tests of tensile strength and secant modulus of elasticity of concrete (due to the lack of standards or difficulties in their implementation) are rarely performed, and so far, there are no reliable test results in this area, but the assumption of proven values is essential for design. For this reason, the ITB Instruction № 194/98, among others, was used [

62]. The concrete was produced in a concrete plant using a specialist mixer to ensure the homogeneity of the mix. After pouring the prepared molds and appropriate care in laboratory conditions, the tests were carried out in accordance with the following procedures:

- secant modulus of elasticity of concrete in accordance with [

63],

- compressive strength according to [

64],

- axial tensile strength according to [

62],

- tensile splitting strength according to [

65],

- flexural strength according to [

66],

- shrinkage according to [

67,

68] (for the determination of creep strains),

- creep strains according to [

62].

For the tests of the secant modulus of elasticity [

63], axial tensile strength [

62], shrinkage according to [

68] and creep according to [

62], cylindrical samples from boreholes with a nominal diameter of 94 mm were used.

For the remaining tests, the samples were prepared in accordance with the relevant standards as described above.

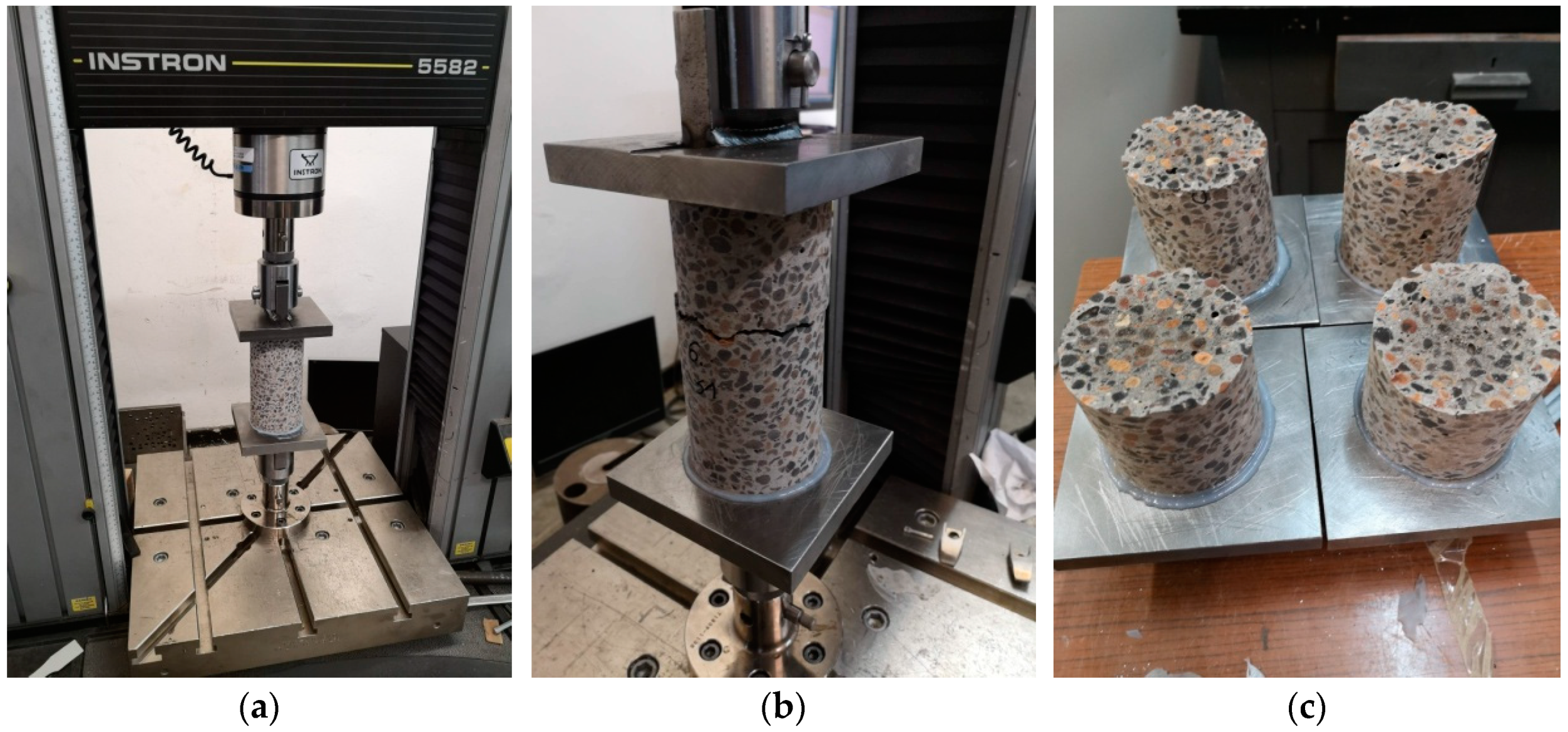

2.5. Types of Testing Machines

The basic devices used to test the mechanical properties of the considered lightweight concrete are presented below. The device used for the axial tensile strength tests, the sample after the test and the fracture forms of the samples are shown in

Figure 3a–c, respectively.

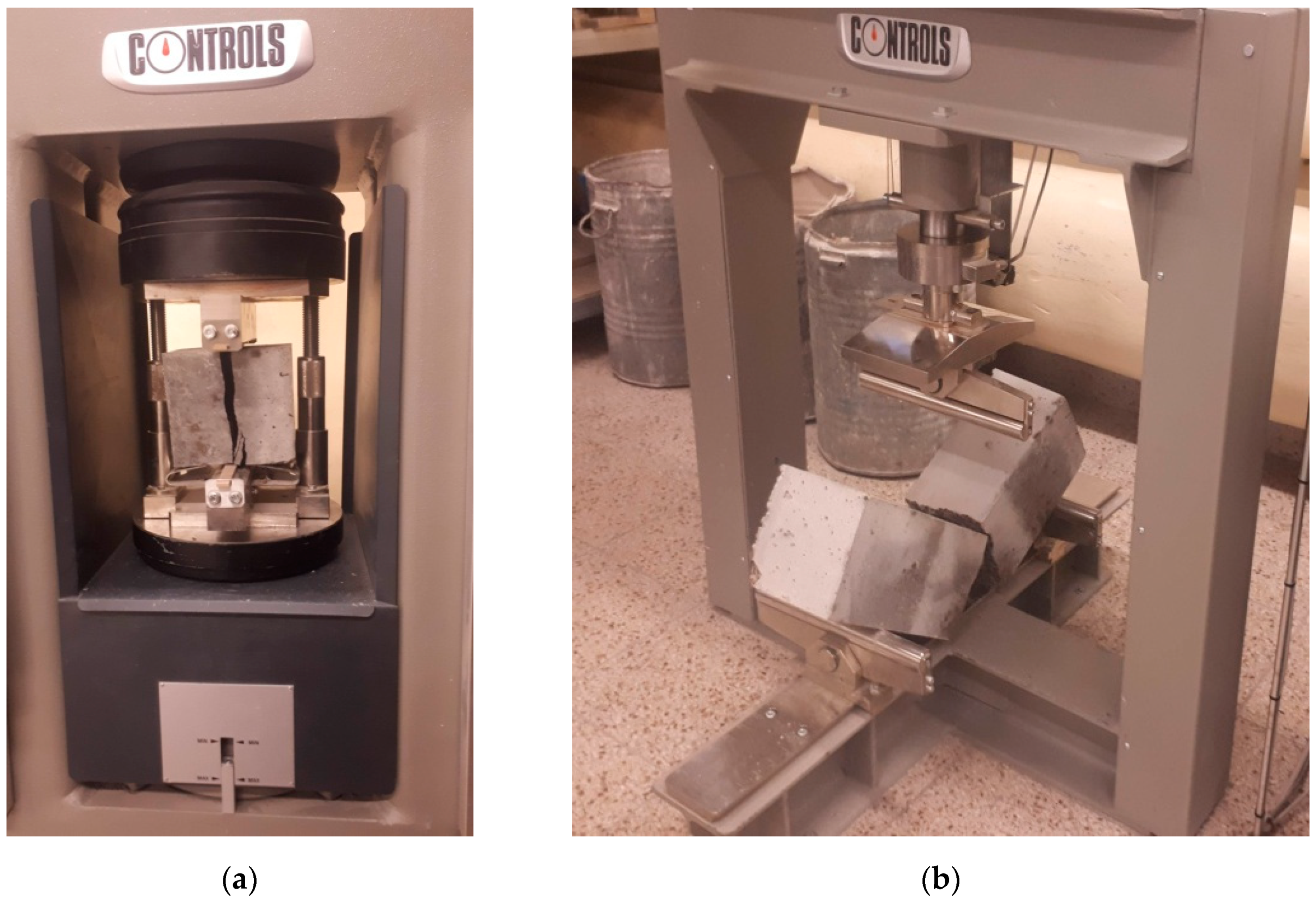

Figure 4a shows the apparatus for testing the tensile strength at splitting and the sample split as a result of the test. The bending strength testing equipment and the sample broken as a result of the test is presented in

Figure 4b). The device for testing the modulus of elasticity is shown in

Figure 5. The last one is the creep-testing machine shown in

Figure 6. The tests were carried out in accordance with the requirements of the relevant standards [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68] and ITB Instruction № 194/88 [

62]. The testing equipment is in the first class of accuracy.

Creep and shrinkage strain tests were carried out in a special cabin while maintaining constant temperature and humidity.

2.6. General Schedule for Long-Term Studies

According to the experimental program, strength tests were performed after 7 and 14 days, then after 28, 60 and 120 days, and finally after 300 days. The shrinkage tests were carried out by the Amsler method at intervals consistent with the reference document [

67], until the results stabilized (see

Figure 12). Only the secant modulus of elasticity and shrinkage development in accordance with the new standard [

68] were studied for a longer period - for the purpose of creep strains testing. The entire creep deformation tests were carried out on six stands in creep-testing machines for 1050 days for LC1 concrete and 1044 days for LC2 concrete; however, in the present work, only the first loading and unloading are described. In addition, the shrinkage was tested according to EN 12390-16 [

68] in the same period of time. The conducted tests allowed us to determine the above-mentioned short-term (see p. 2.4) and long-term parameters of concrete samples with lightweight sintered aggregate.

3. Results

3.1. Test Results for Strength Properties

3.1.1. Test Results for Compressive Strength

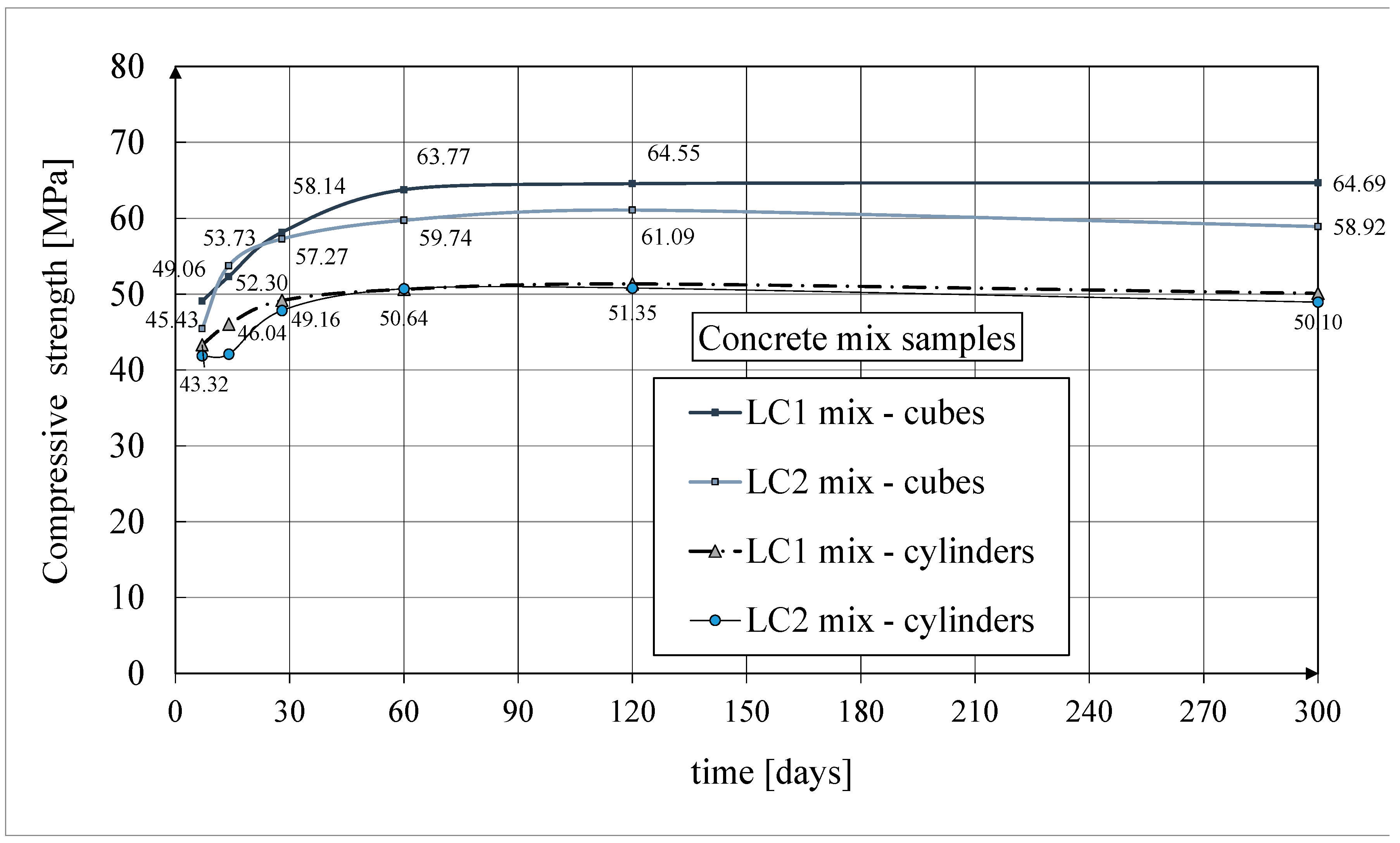

The test results for compressive strength of cubical and cylindrical samples are shown in

Figure 7. After 7 days from the preparation of the samples, the concrete mixes LC1 and LC2 obtained the LC 35/38 class according to [

69] (see

Figure 7). The numerical labels in the graphs refer to the cube strength and, in addition, in the case of the cylindrical strength, only to the results obtained from concrete samples for the LC1 mix due to overlapping graphs.

At 28 days, these mixes achieved two following classes, finally reaching the LC 45/50 class according to [

69] with the D1.8 density class. The results of these tests up to 60 days of concrete age were previously published in the works of Rogowska and Lewiński [

54,

55]. Tests of concrete cube compressive strength were carried out for typical samples with dimensions of 150×150×150 mm in accordance with the standard [

64]. Samples (drilled from a lightweight concrete block) with a nominal diameter of 94 mm and a height of 190 mm were used to test the concrete cylindrical compressive strength.

3.1.2. Test Results for Axial Tensile Strength

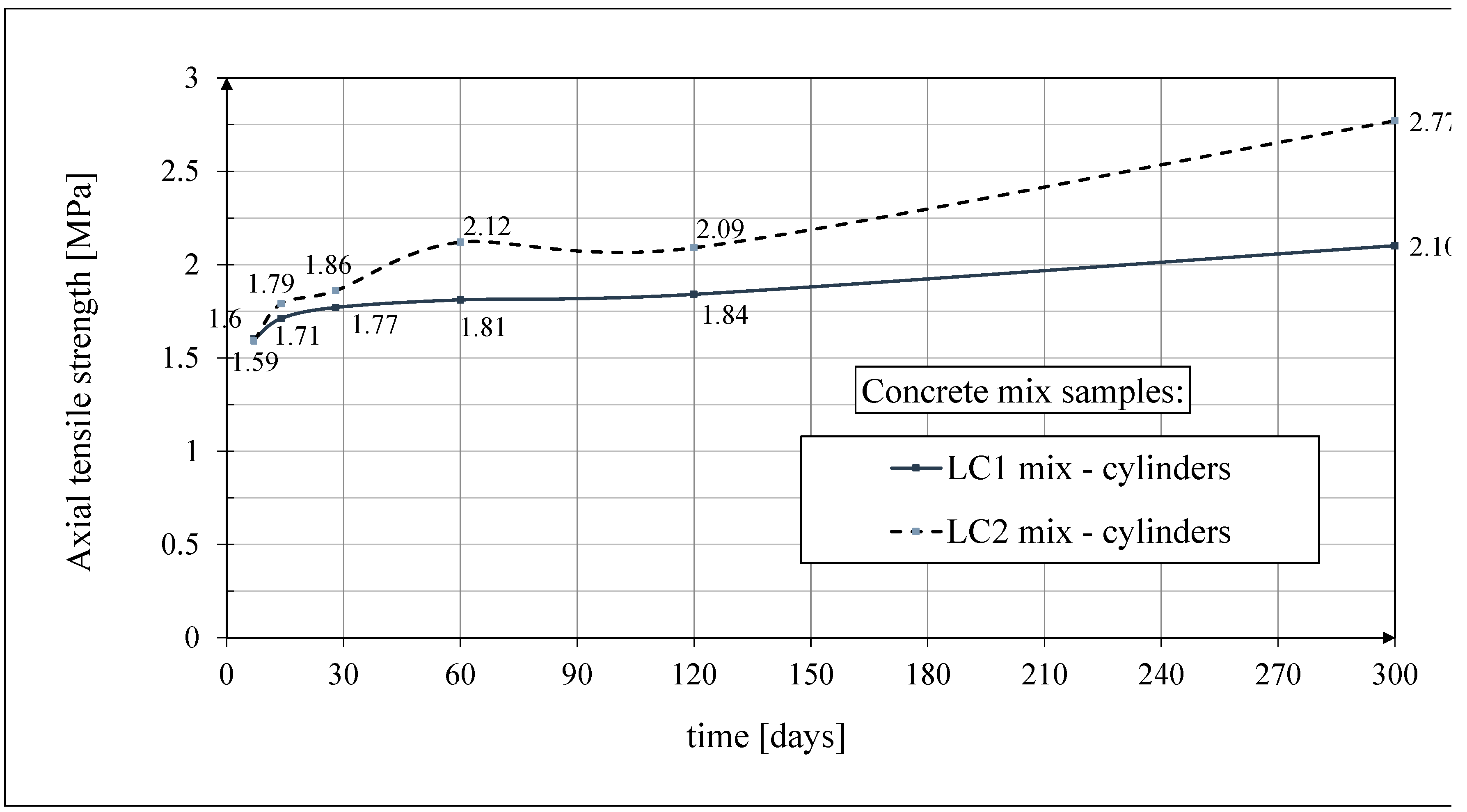

The test results for the tests of the development of the axial tensile strength of concrete LC1 and LC2 according to ITB Instruction No. 194 [

62] after 14, 28, 60, 120 and 300 days from the sample production are given in

Figure 8. The tests of axial tensile strength were carried out for cylindrical samples with the diameter

d = 94 mm and height

h = 190 mm, selecting the same cross-section of samples for testing as those intended for creep tests (and accompanying shrinkage tests). Seven days after the samples’ preparation, the LC1 and LC2 mixes achieved the axial tensile strength of 1.6 MPa (see

Figure 8). After 28 days, the strength increased by more than 10%. The results of these tests up to 60 days of concrete age were published in the works [

54,

55].

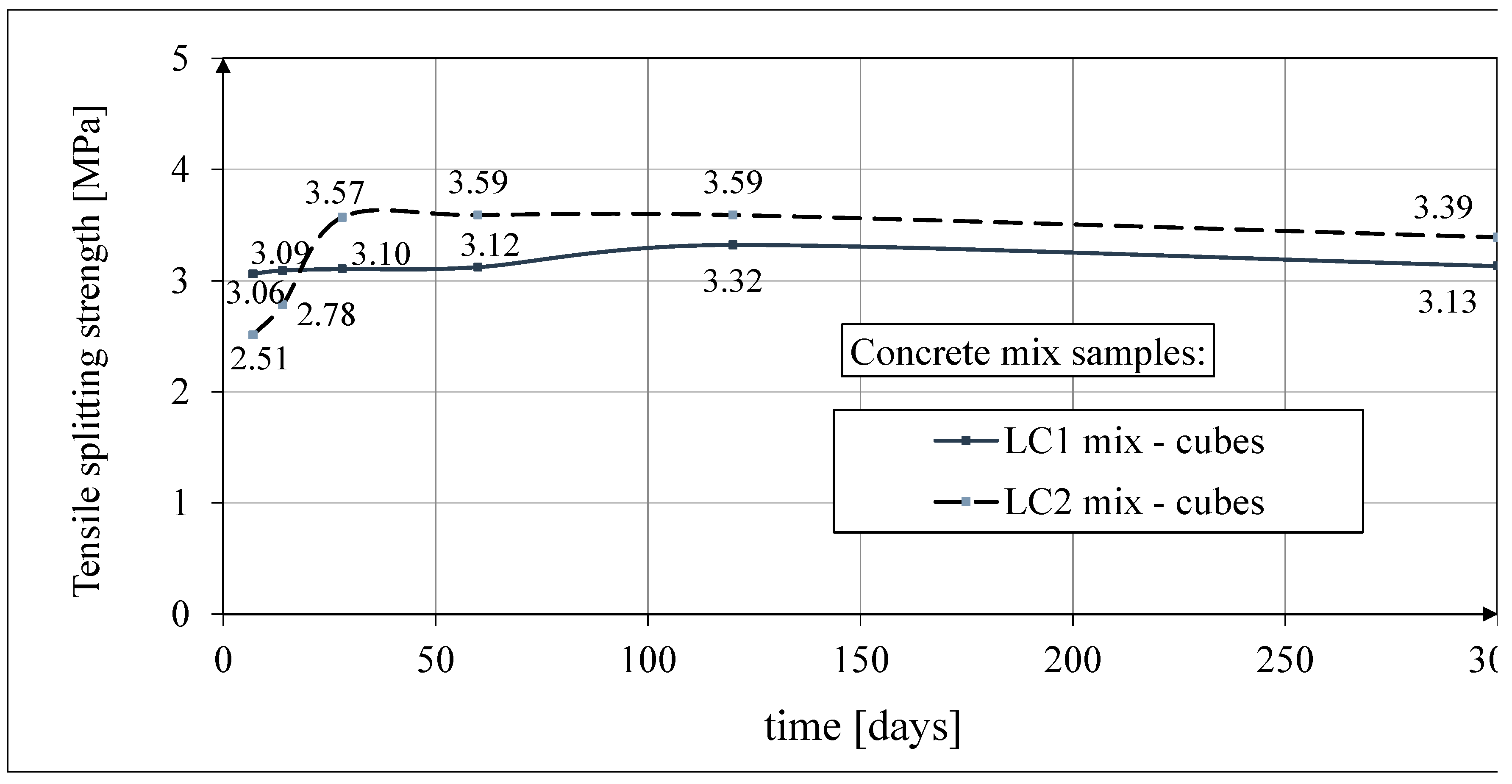

3.1.3. Test Results for Tensile Splitting Strength

The test results for the tensile splitting strength of test specimens are given in

Figure 9.

The splitting strength results for the LC1 mix over 60 days were fairly constant and these results for the LC2 mix increased by more than 40% between days 7 and 28. Tests of concrete tensile splitting strength were carried out for typical cubic samples with dimensions of 150×150×150 mm in accordance with the standard [

65]. The results of these tests up to 60 days of concrete age were previously published in the paper [

54].

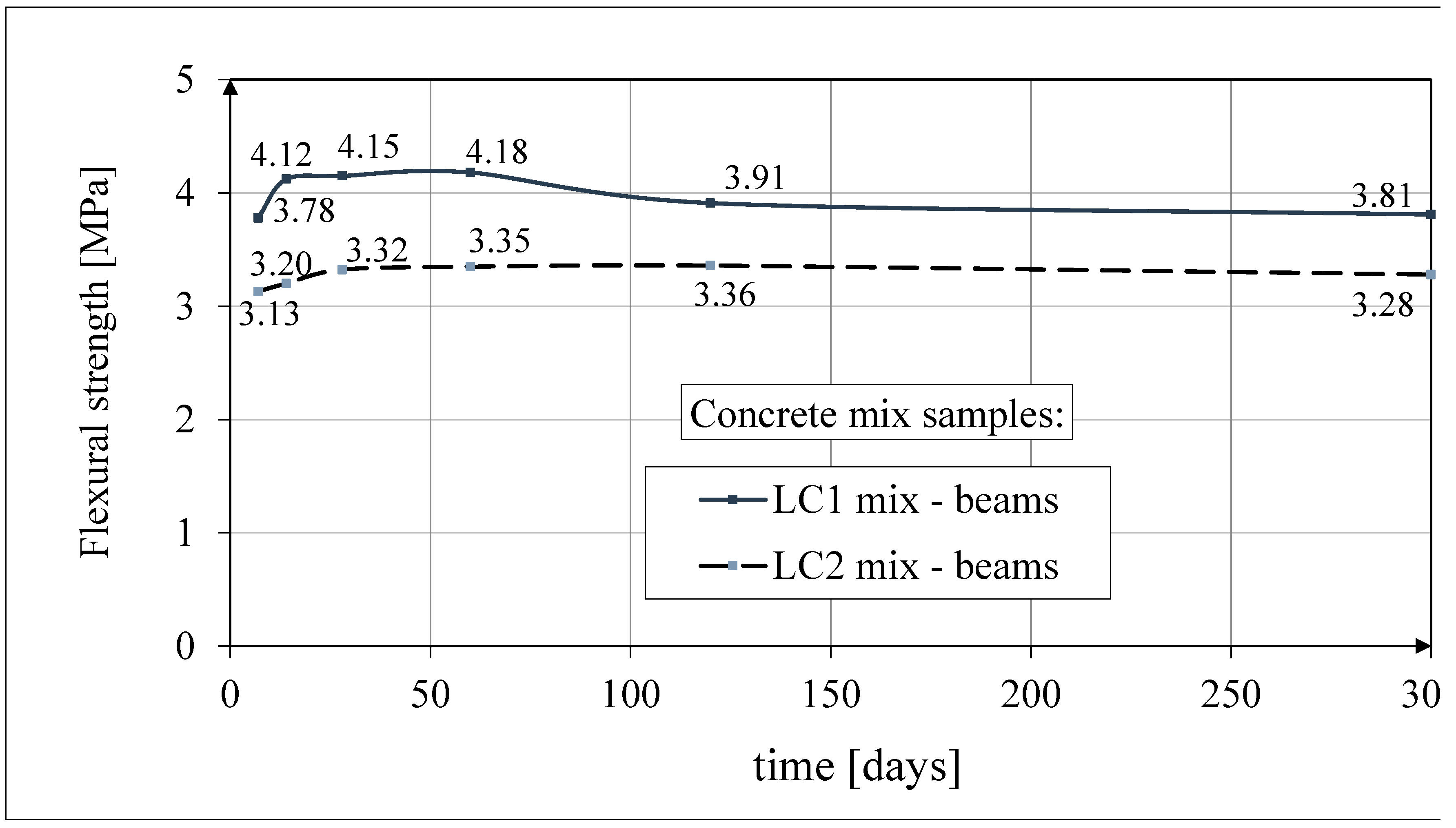

3.1.4. Test Results for Flexural Strength

The results of the concrete flexural strength test are shown in

Figure 10. Tests of flexural strength were carried out for both concrete mixes on three prismatic samples with dimensions 550×150×150 mm in accordance with the standard [

66], and the spacing of the support rollers was 450 mm.

The flexural strength results for the LC2 mix over 60 days were fairly constant and these results for the LC1 mix increased by over 10% between 7 and 28 days. The results of these tests up to 60 days of concrete age were published earlier in the paper [

54].

3.1.5. Statistical Evaluation of Test Results and Estimation of Measurement Uncertainty

The graphs given in the above figures show the average strength test results obtained from 3 samples, except for the concrete tests after 28 days from casting, which show the average results from 10 samples. In the case of the cube compressive strength of LC1 and LC2 concrete samples after 28 days from their production, the values of their strength were 58.3 MPa and 57.6 MPa, respectively, the standard deviations were 0.48 MPa and 0.87 MPa, respectively, and the coefficients of variation were 0.81 % and 1.50 %, respectively, which indicates very good homogeneity of both LC1 and LC2 concrete. In the case of the cylindrical compressive strength of LC1 and LC2 concrete samples 28 days after their production, the strength values were 49.2 MPa and 47.8 MPa, respectively, the standard deviations were 2.49 MPa and 1.21 MPa, respectively, and the coefficients of variation were 5.07% and 2.53%, respectively, which also indicates very good homogeneity of both LC1 and LC2 concrete.

The average values of the tensile strength of LC1 and LC2 concrete cube samples in splitting test 28 days after making the samples were 3.10 MPa and 3.57 MPa, respectively, with standard deviations of 0.18 MPa and 0.21 MPa, respectively, and coefficients of variation of 5.84% and 5.78%, respectively, while the average values of the tensile strength of LC1 and LC2 concrete samples in bending test 28 days after making the samples were 4.15 MPa and 3.32 MPa, respectively, with standard deviations of 0.21 MPa in both cases, and coefficients of variation of 5.01% and 6.28%, respectively, which means that from the point of view of the tensile strength of this concrete in splitting and in bending, the homogeneity of this feature of both LC1 and LC2 concrete is very good.

However, the axial tensile strength of cylindrical LC1 and LC2 concrete samples after 28 days from the sample production was determined in both cases and the average values of this strength were 1.77 MPa and 1.86 MPa, respectively, the standard deviations were 0.57 MPa and 0.34 MPa, respectively, and the coefficients of variation were 31.94% and 18.21%, respectively, which means that, in contrast to the tensile strength in splitting and in bending of the concrete under consideration, the inhomogeneity of this feature of concrete, both LC1 and LC2, is very high, and the tensile strength is a weak point of this concrete, so it is quite brittle.

This differentiation of the tensile strength of samples depending on the method of testing the samples requires some comment. The axial tensile strength test seems to be the most objective, but it has a significant drawback. While the method of testing the tensile strength in splitting and in bending does not change its essence during loading, in the case of the axial tensile strength test, an unintended eccentricity may occur due to the inhomogeneity of the concrete in the cross-section, which in turn means that the sample, assumed to be under the axial tension, is in fact subjected to a tensile force and a bending moment of unknown value, which in turn leads to a series of results with a fairly large and varied standard deviation.

This does not mean that there is only one correct way to test tensile strength, because different mechanisms of failure in tension occur in different stress states. For example, axial tension may occur when a wall made of the concrete under consideration connects two similarly constructed floors, the lower one of which is more heavily loaded than the upper one, and then the crack will be horizontal. Tension, such as in splitting, may occur below the edge of the beam where it rests on the lightweight concrete wall, and tension in bending - e.g. in a floor slab made of tested concrete. In all three cases, cracks will appear at different stress levels, and this is because the appearance of these cracks is not actually determined by stresses, but by deformations exceeding a certain permissible limit.

The uncertainty of measurement results is closely related to any test results. Although error analysis has long been a part of metrology, the concept of uncertainty as a feature expressed numerically is relatively new. The results of strength tests of concrete samples LC1 and LC2 on lightweight sintered aggregate for concrete ages t = 7, 14, 28, 60, 120 and 300 days were developed together with the expanded measurement uncertainty (U). The calculation of this uncertainty was based on the normal distribution, the expansion probability of about 95 % and the coverage factor k = 2. The standard uncertainties were determined using corrections related only to the accuracy of the measuring devices used.

The determined expanded uncertainty of the measurement (U) in percentage terms did not exceed the following values:

As can be easily seen, the uncertainties obtained in the strength test results for both compressive strength and axial tensile strength are very small and smaller than the coefficients of variation of the particular strength properties.

3.2. Test Results for Long-Term Properties

3.2.1. Test Results for Secant Modulus of Elasticity

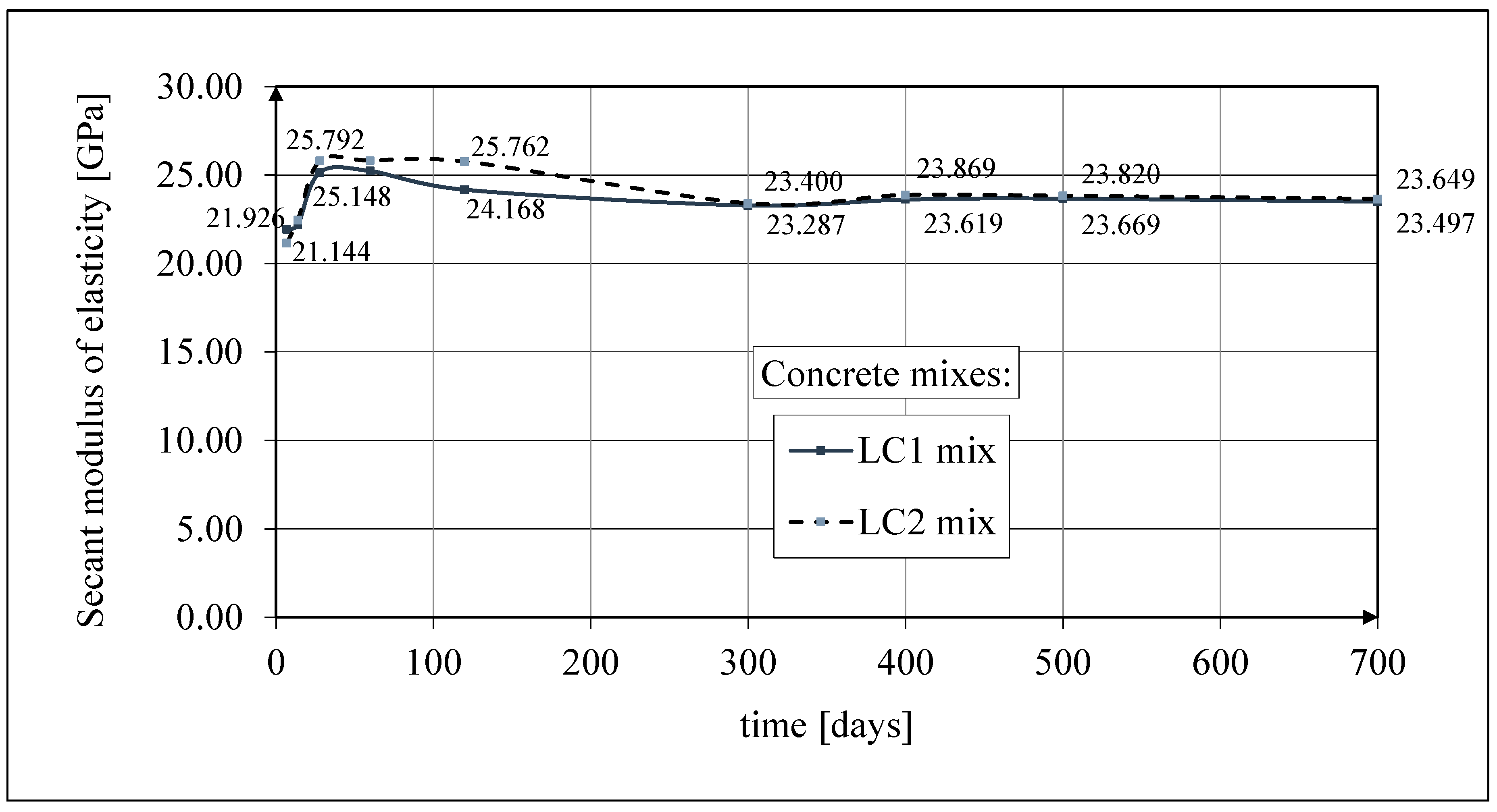

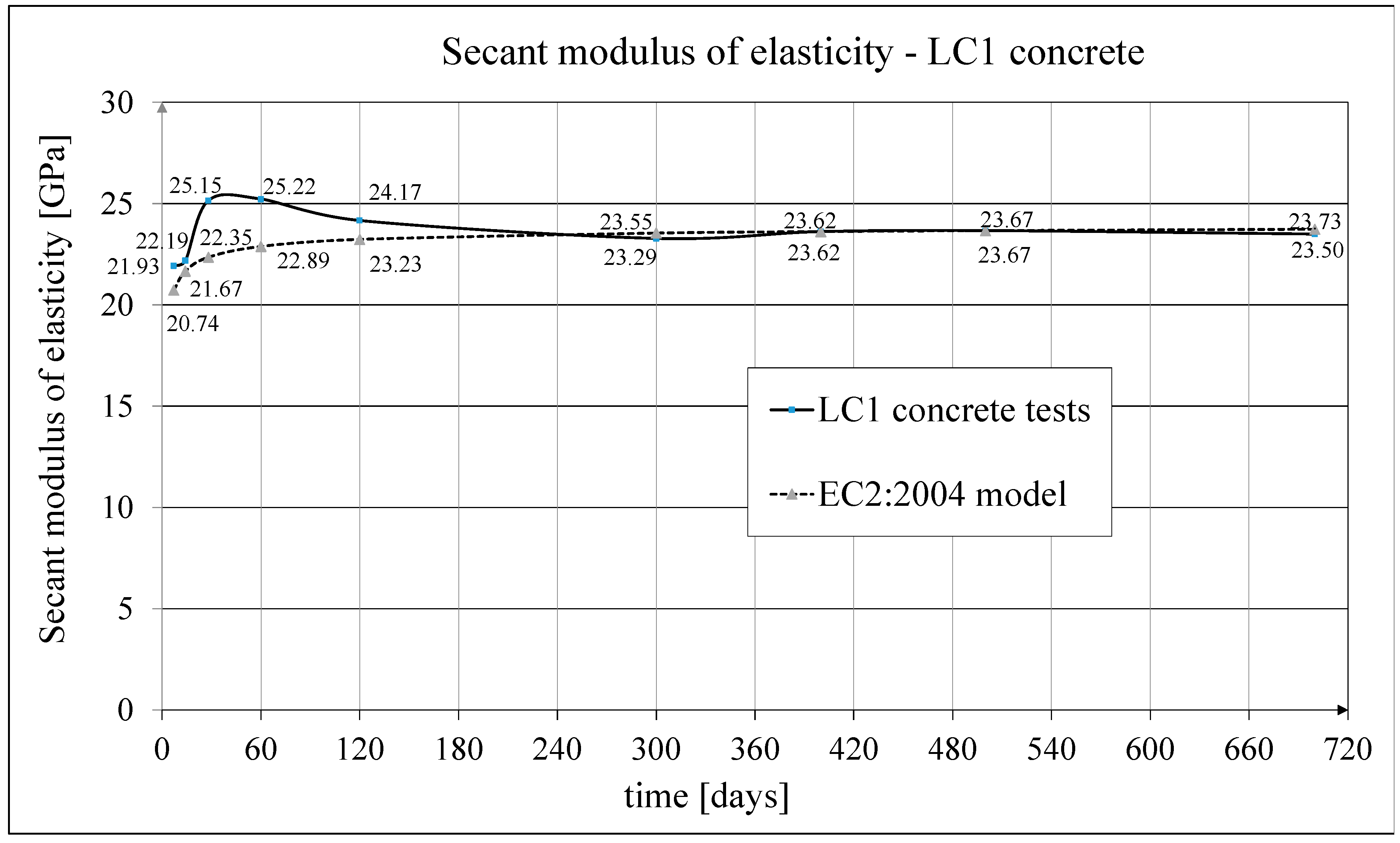

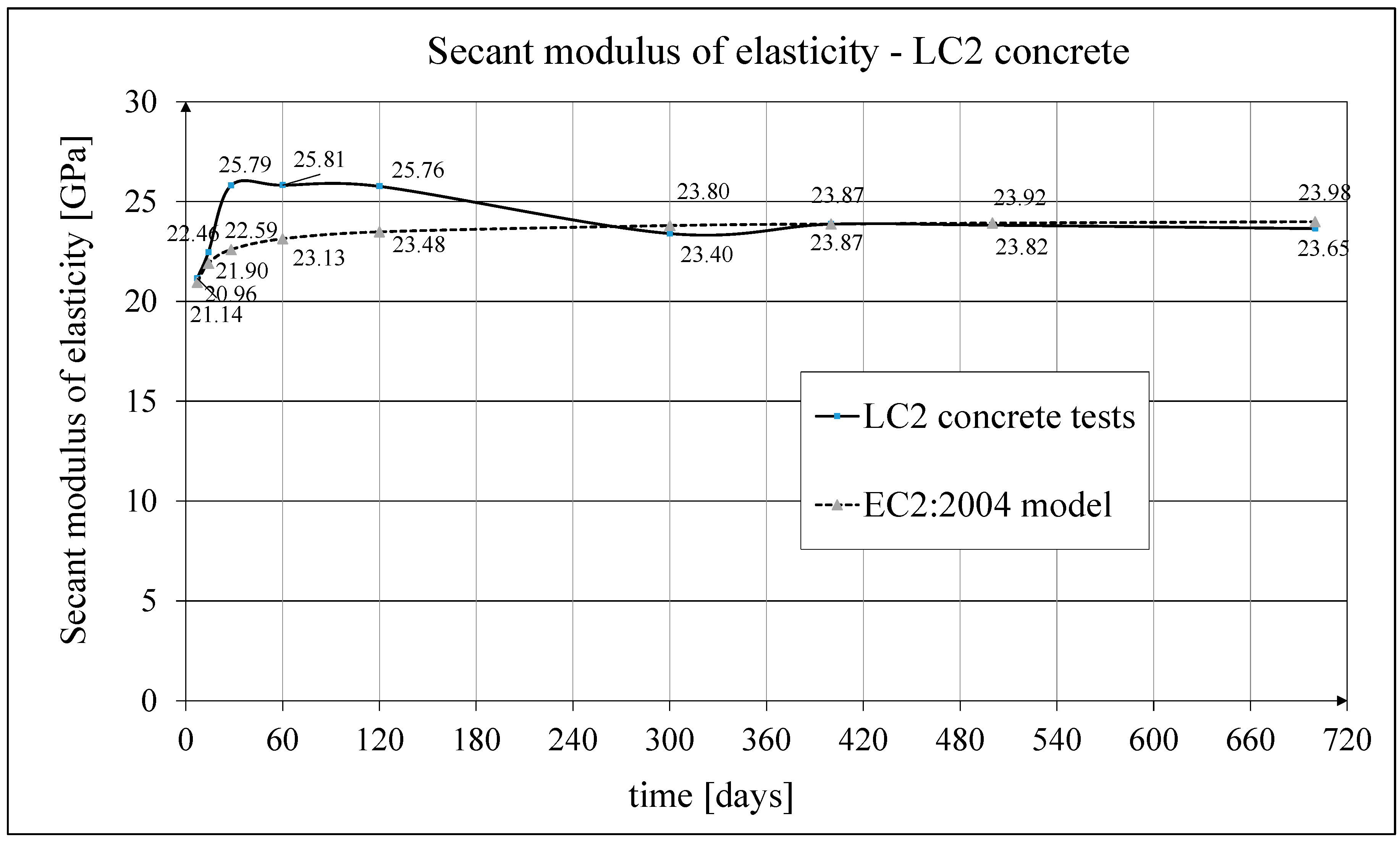

The results of the tests of the secant modulus of elasticity of concrete are shown in

Figure 11. The results of the tests up to 60 days of concrete age were published in the works [

54,

55]. The tests of the secant modulus of elasticity of concrete in compression were carried out according to the standard [

63] for the samples with the diameter

d = 94 mm and height

h = 190 mm, selecting the same cross-section of samples for testing as those intended for creep tests (and accompanying shrinkage tests).

The test results for two concrete mixes, LC1 and LC2, showed a similar increase over 60 days. The secant modulus of elasticity increased approximately 13% between 7 and 28 days. The course of changes in the modulus of elasticity of the tested concrete on lightweight sintered aggregate, illustrated in

Figure 11, is not obvious. From the previously cited literature sources it results that the values of the secant modulus of elasticity of concrete are inversely proportional to the value of drying shrinkage. The curing of concrete was completed after 28 days. The purpose of curing concrete is, among others, to reduce the amount of drying shrinkage. However, the drying shrinkage is different in the case of concrete with porous aggregate than in plain concrete.

Figure 12 shows that after 28 days the shrinkage strains have not yet reached half their final value. Completing the curing process may coincide with water drying in aggregate pores due to the moisture migration in the concrete. In this case, there will be an increase in drying shrinkage in the entire volume of concrete after the end of the curing process. Increased shrinkage stresses (in contrast to plain concrete) are not compensated by the increase in the strength of the cement matrix due to its accelerated drying in the zones of contact with the porous aggregate. This may initiate the formation of micro-cracks, which do not significantly impact the compressive strength of lightweight concrete, but after the curing is completed, they may reduce the tensile strength and the value of the elasticity modulus of the concrete under consideration. The effect of initial wetting of lightweight aggregate on the tensile strength of concrete and its rheological properties in tension was the subject of tests in many papers, e.g. in [

28,

70,

71], and the effect of concrete curing time, e.g. in [

72], and the effect of lightweight aggregate impregnation was analyzed in [

3].

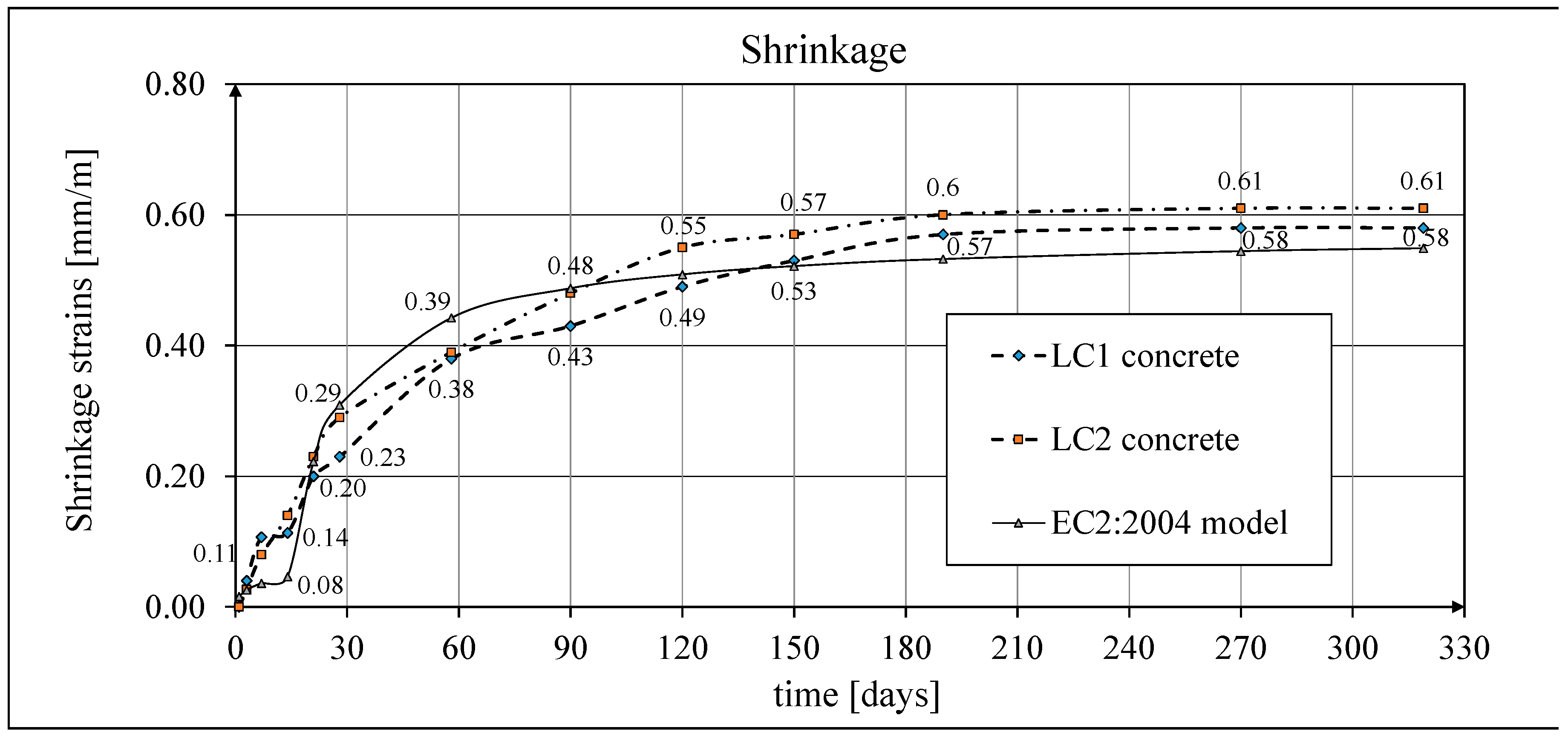

Figure 12.

The development of the shrinkage according to the Amsler tests and EC2:2004 model.

Figure 12.

The development of the shrinkage according to the Amsler tests and EC2:2004 model.

3.2.2. Statistical Evaluation and Measurement Uncertainty of the Modulus of Elasticity

The values of the secant modulus of elasticity of the LC1 and LC2 concrete samples 28 days after their production were determined in both cases based on testing 10 cylindrical samples, with the average values of these moduli being 25,150 MPa and 25,790 MPa, respectively, the standard deviations being 1,135 MPa and 601 MPa, respectively, and the coefficients of variation of the modulus of elasticity being 4.51 % and 2.33 %, respectively, which indicates very good homogeneity of the concrete in this range, both for LC1 and LC2 concrete samples. The determined expanded uncertainty of the measurement (U) of the secant modulus of elasticity given in percentage terms did not exceed the values: 2.03 % for LC1 concrete and 1.92 % for LC2 concrete. As can be easily seen, the obtained measurement uncertainty of the modulus of elasticity test results are very small and smaller than the coefficients of variation of the particular modules.

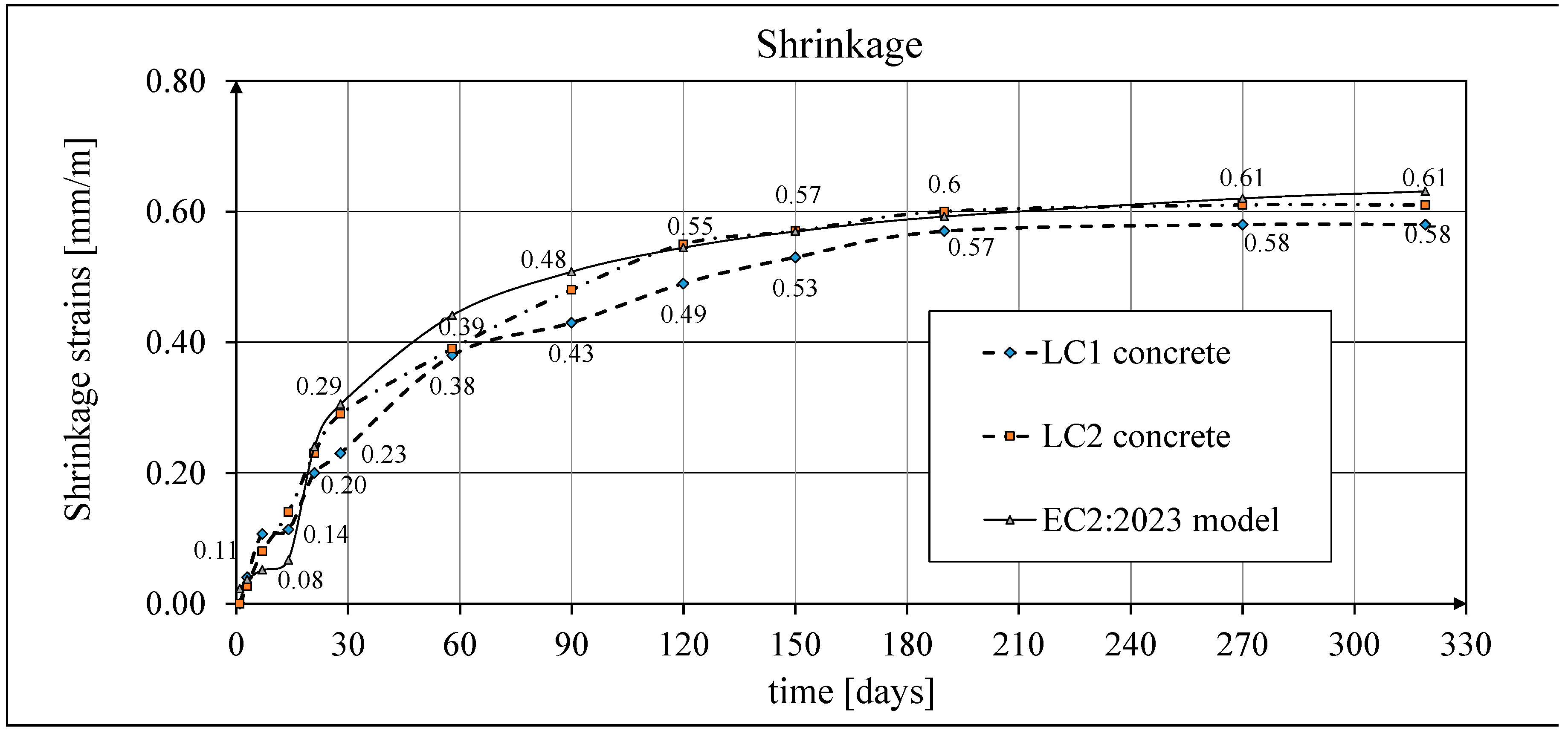

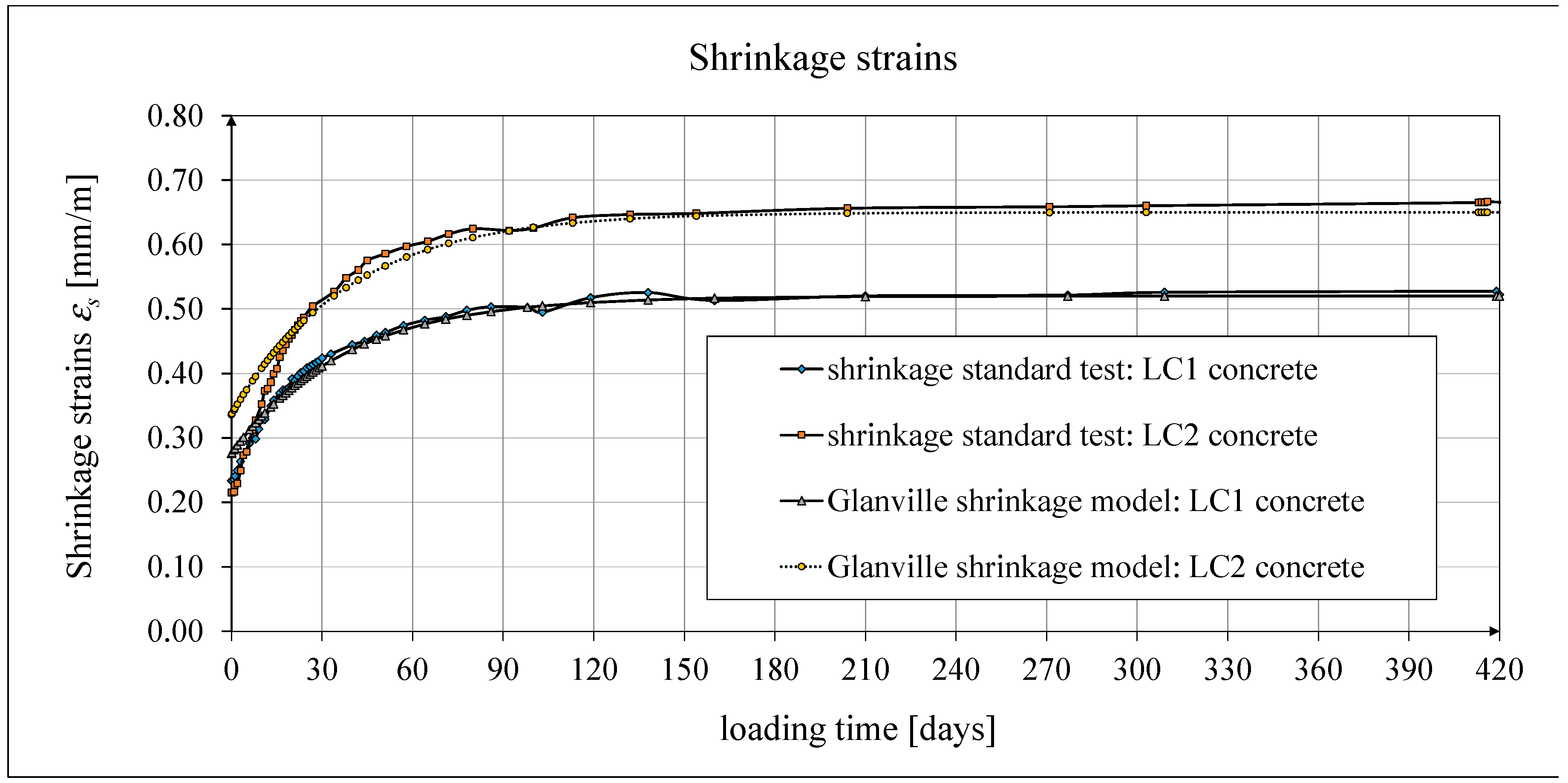

3.2.3. Test Results for Shrinkage Strains

Two methods of measuring shrinkage strains were adopted: tests using the standard Amsler method [

67], which were carried out on three prismatic samples with dimensions of 100×100×500 mm, and tests conducted in accordance with the current EN 12390-16 standard [

68] on cylindrical samples with dimensions: diameter

d = 94 mm, height

h = 3

d = 282 mm, selecting the same geometry of the samples as those intended for creep tests, in accordance with ITB Instruction No. 194/98 [

62]. The strains were measured for samples made of both LC1 and LC2 concrete mixtures. The results of the tests conducted using the Amsler method [

67] included readings initially taken at intervals of several days, then weekly, monthly and longer. The entire research process lasted 325 days from the time the samples were made. The results of the shrinkage development tests of LC1 and LC2 concrete samples, conducted using the Amsler method [

67] are shown in

Figure 12. Creep and shrinkage measurements were carried out on samples stored in a special laboratory cabin, where temperature and humidity were monitored and kept constant. Concrete samples marked LC1 and LC2 showed similar increases in shrinkage. However, the LC1 mix showed very little shrinkage between days 7 and 14. Consistent results were obtained for both lightweight concretes at 58 days, while the shrinkage of the LC1 concrete was ultimately found to be slightly lower. The test results up to day 58 of concrete age have been previously published in [

54,

55].

The results of shrinkage strain tests can be approximated using the Glanville model [

73], in which the theoretical curves were adopted according to the following relationship:

A comparison of the concrete shrinkage development as a result of tests made according to EN 12390-16 standard [

68] and based on the Glanville model [

73] (see equation (1)) during creep strain tests is shown in

Figure 13, where

s = 0.027 and

ε 0 = 0.00052 for LC1 concrete and

s = 0.026 and

ε 0 = 0.00065 for LC2 concrete to determine the additional shrinkage (

εas) after 28 days of concrete binding.

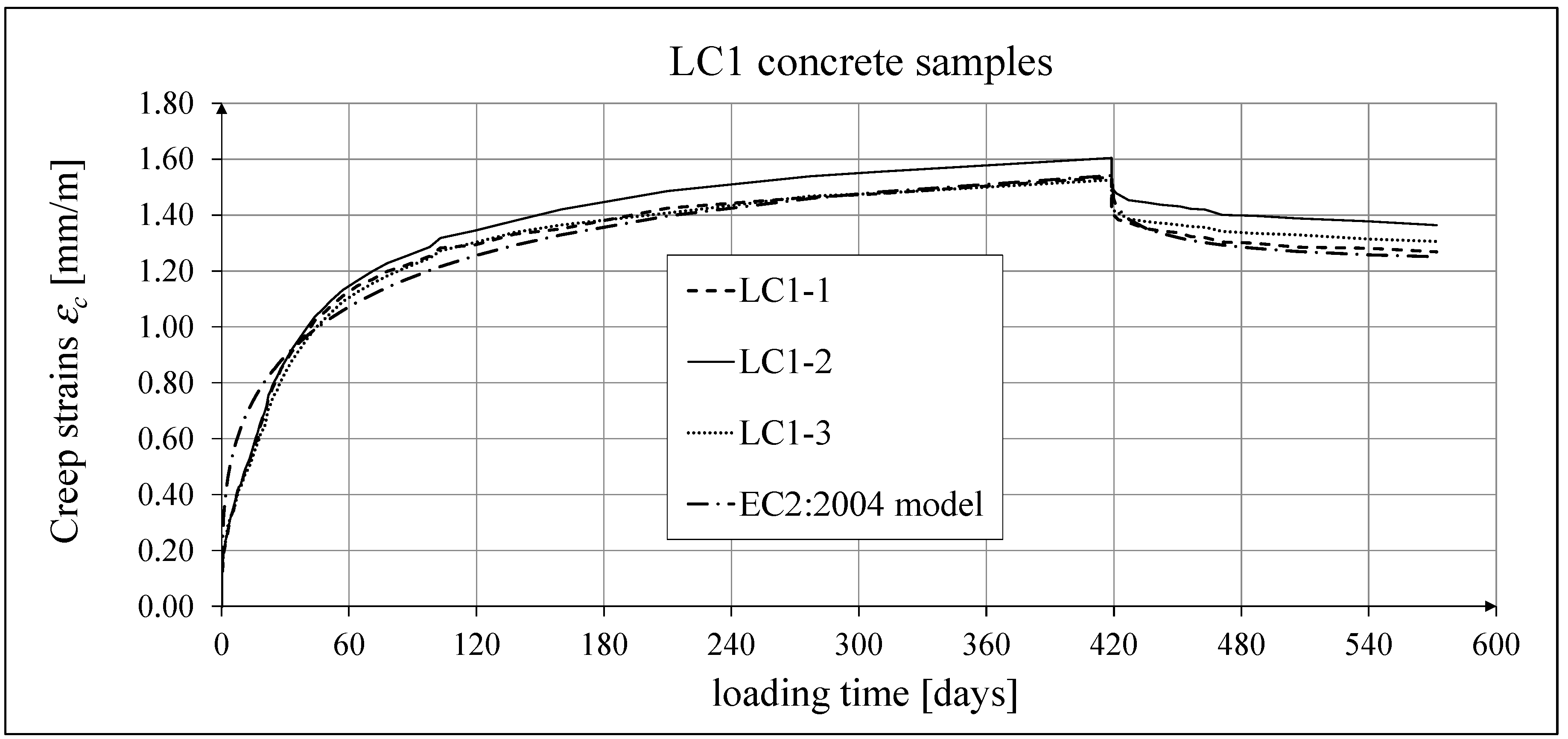

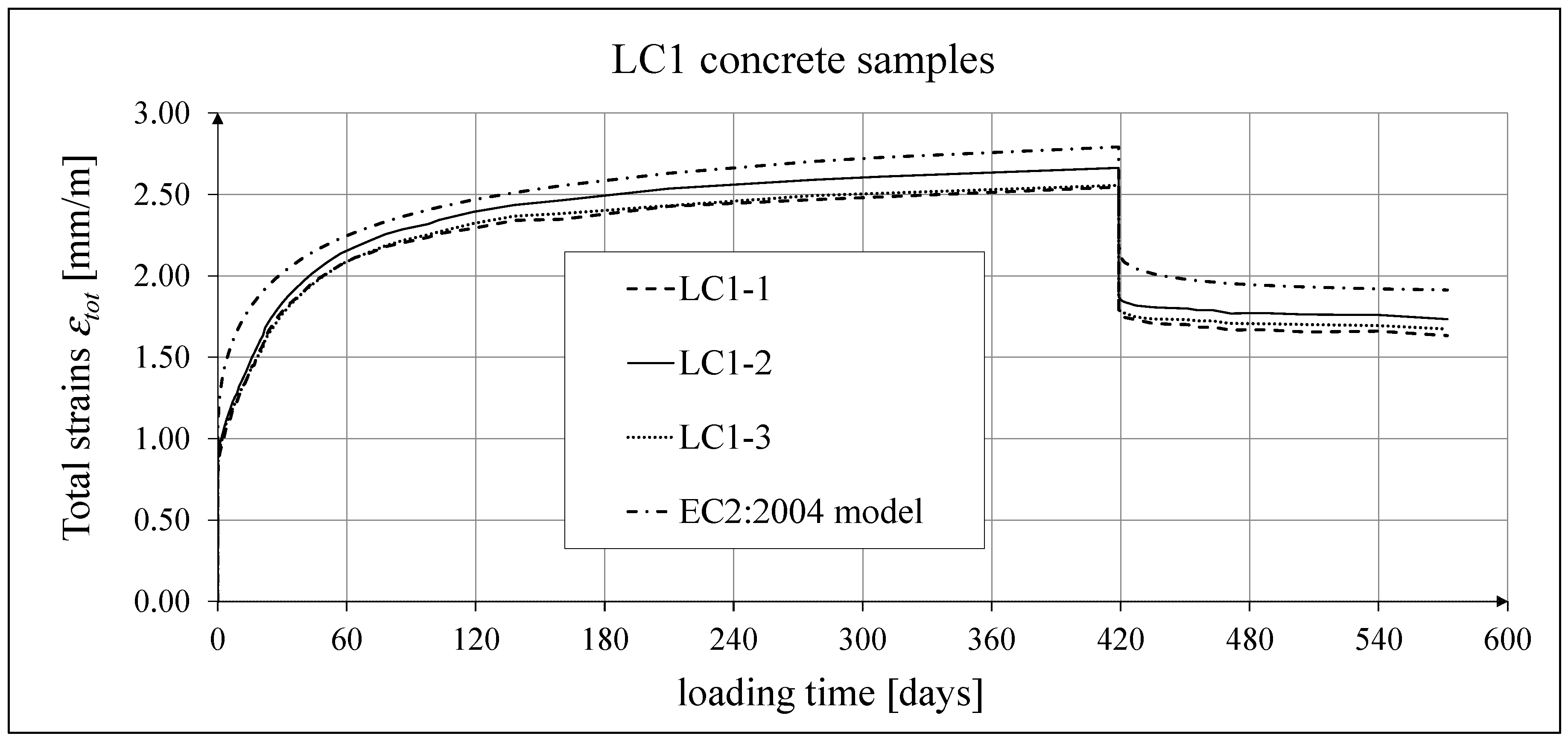

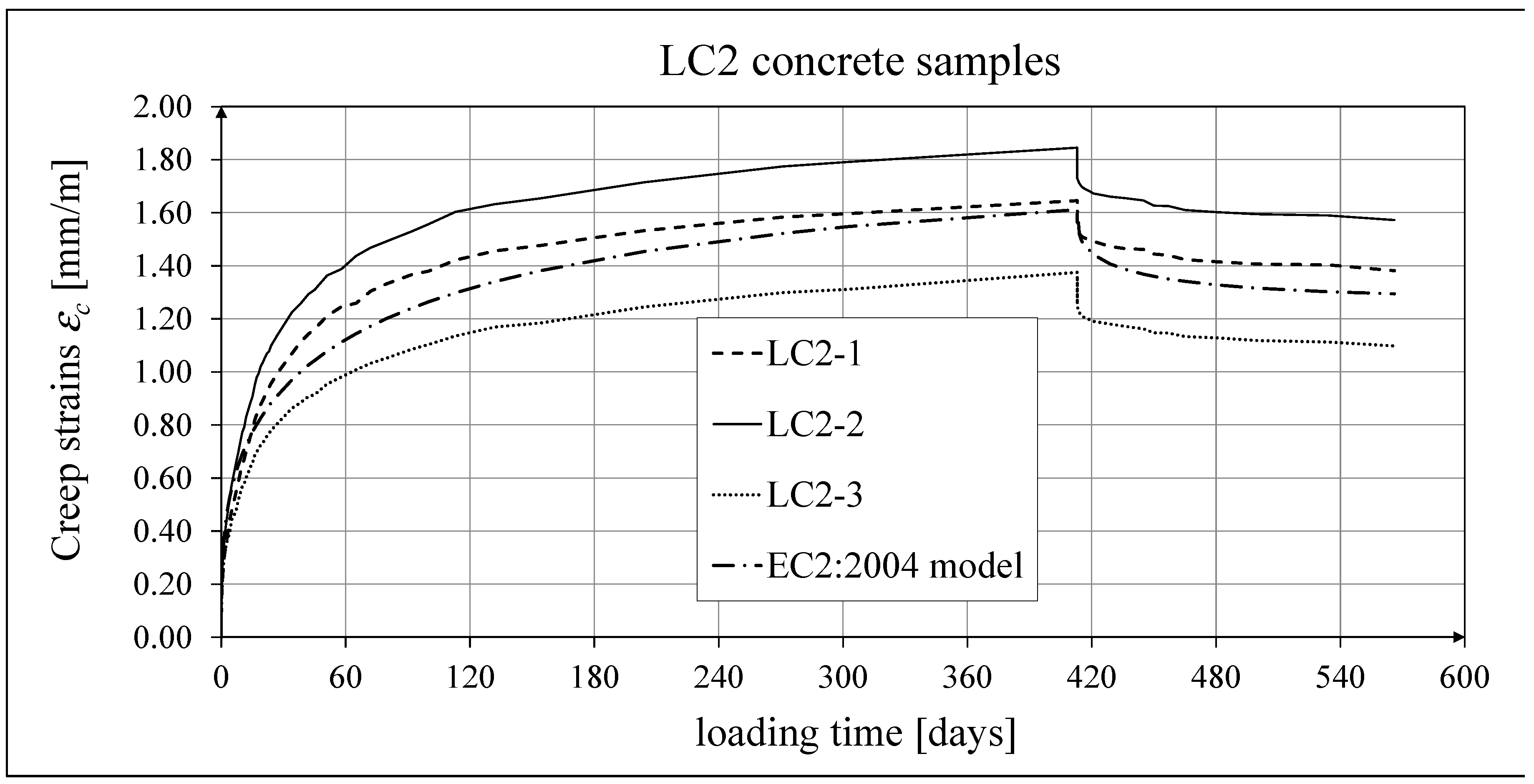

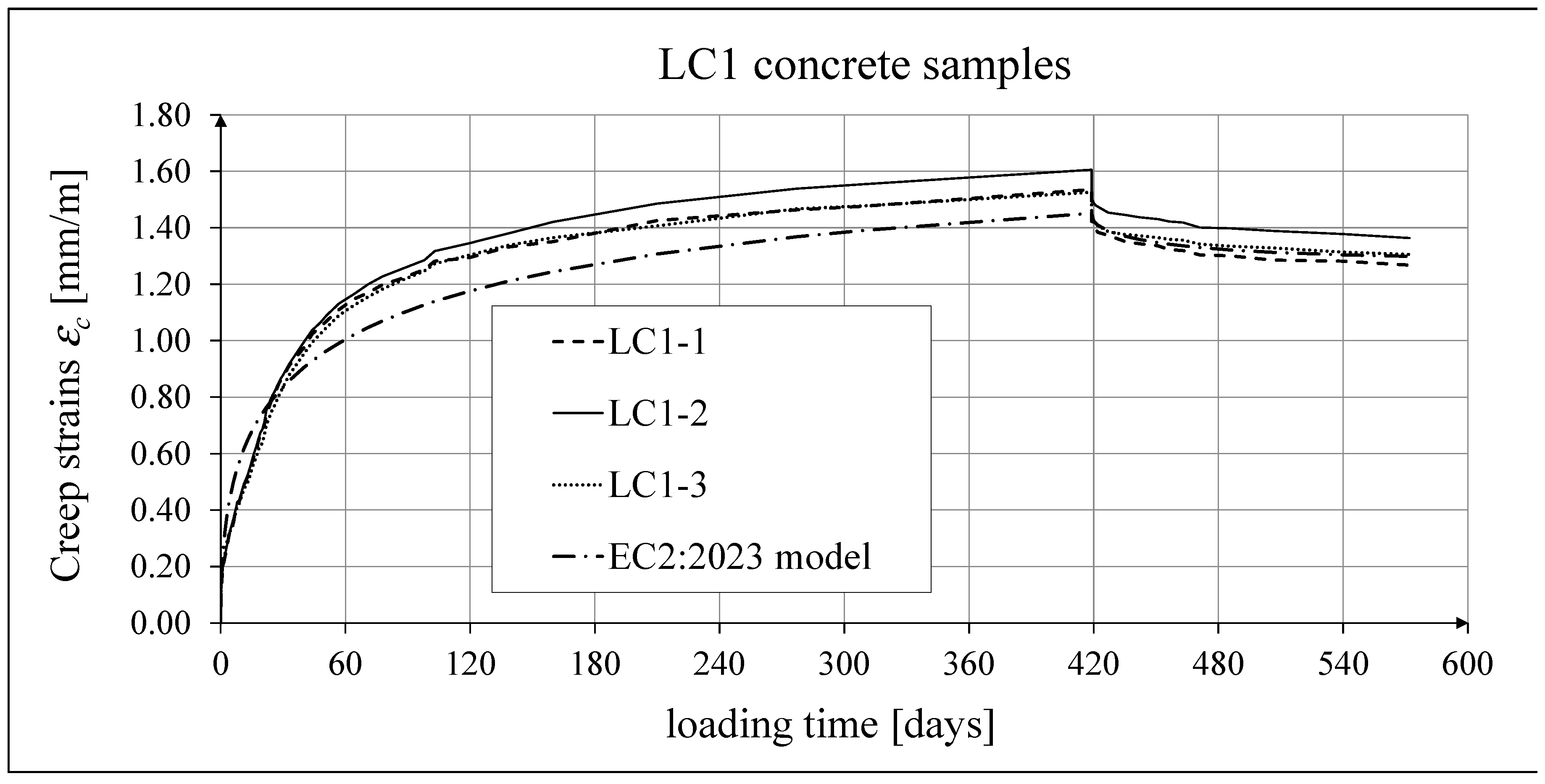

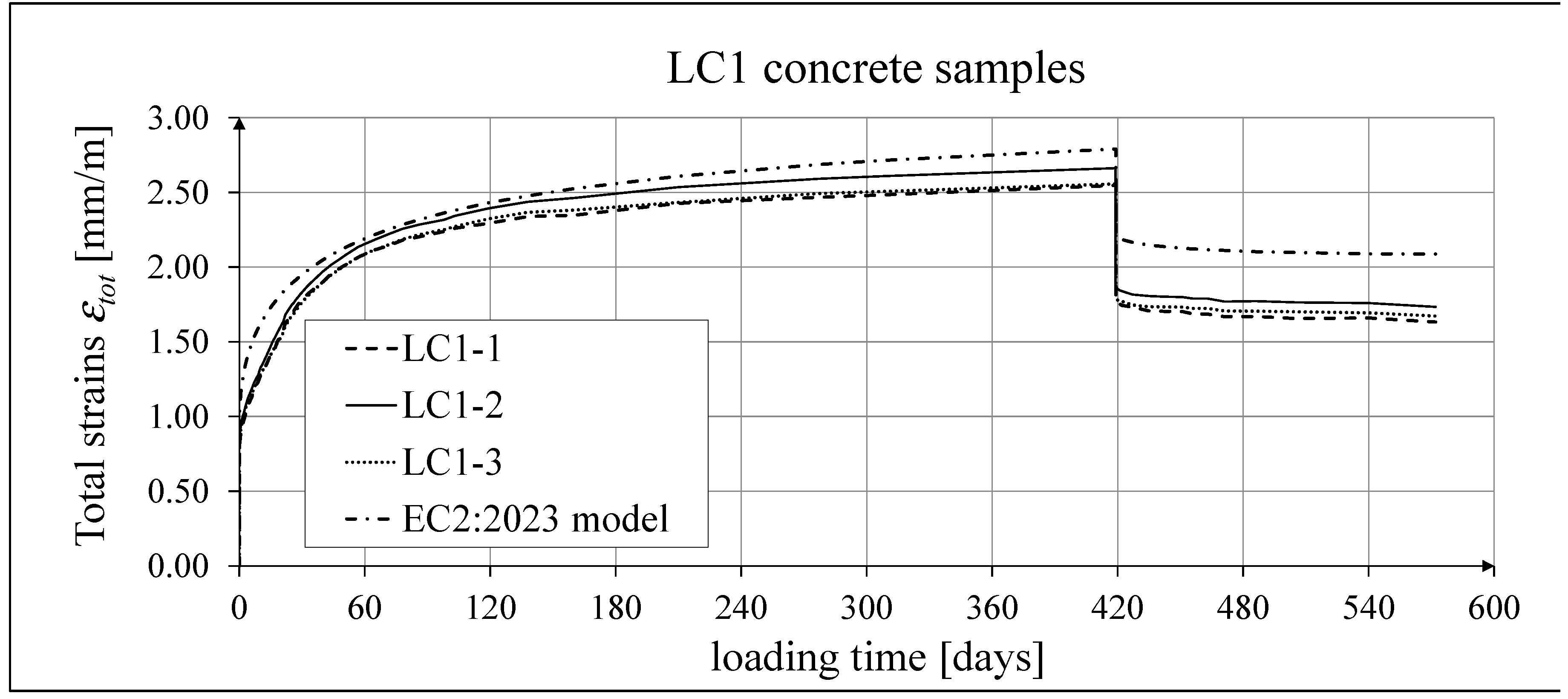

3.2.4. Test Results for Creep Strains

Creep measurements for the samples taken from two concrete mixes LC1 and LC2 were carried out in both cases for the samples with dimensions: diameter

d = 94 mm, height

h = 3

d = 282 mm in accordance with ITB Instruction № 194/98 [

62] (the same type of samples as used for shrinkage tests according to the standard method [

68]). The lightweight concrete samples were 28 days old at the first loading. The strains were measured for both LC1 and LC2 concretes (see

Figure 6) assuming the long-term loading program, however, in the present work only the first loading and unloading are described in detail.

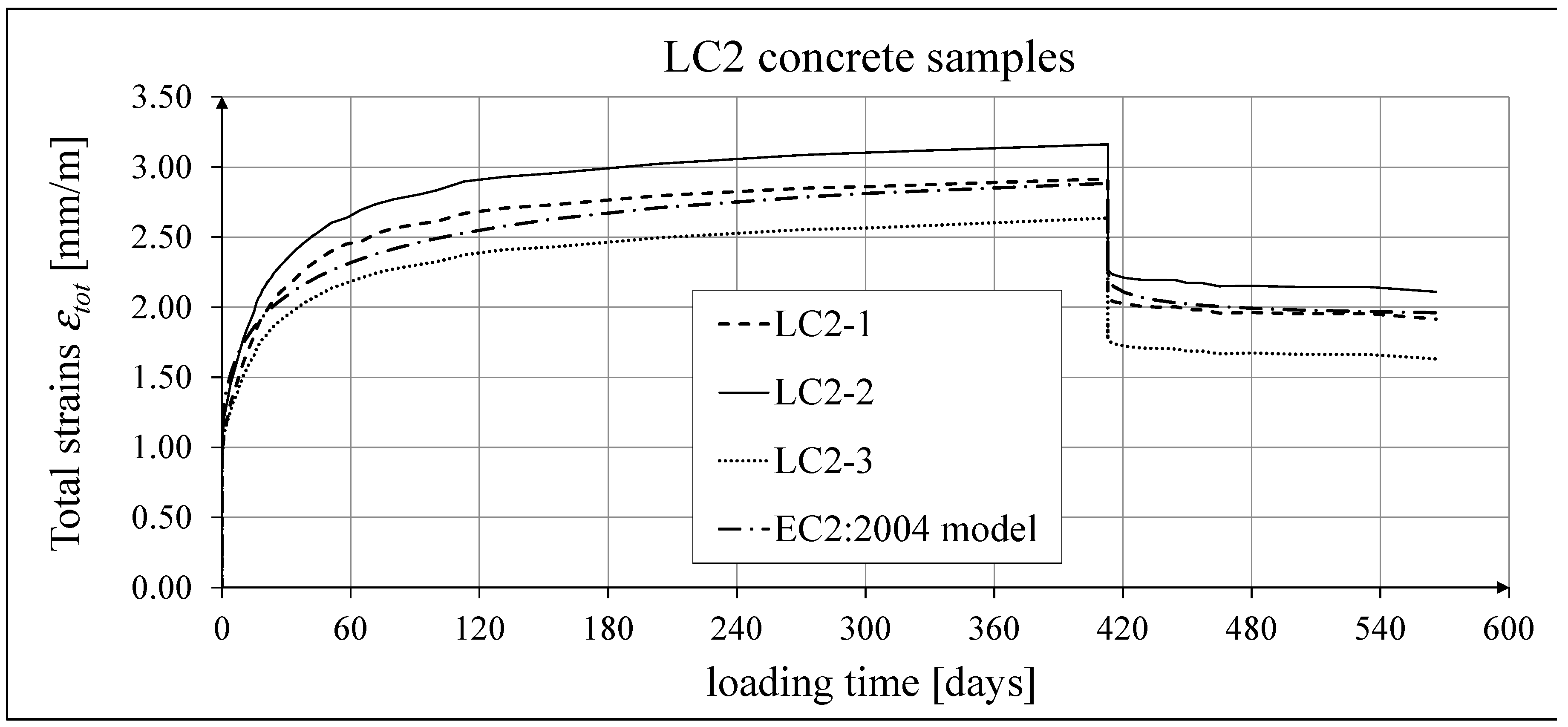

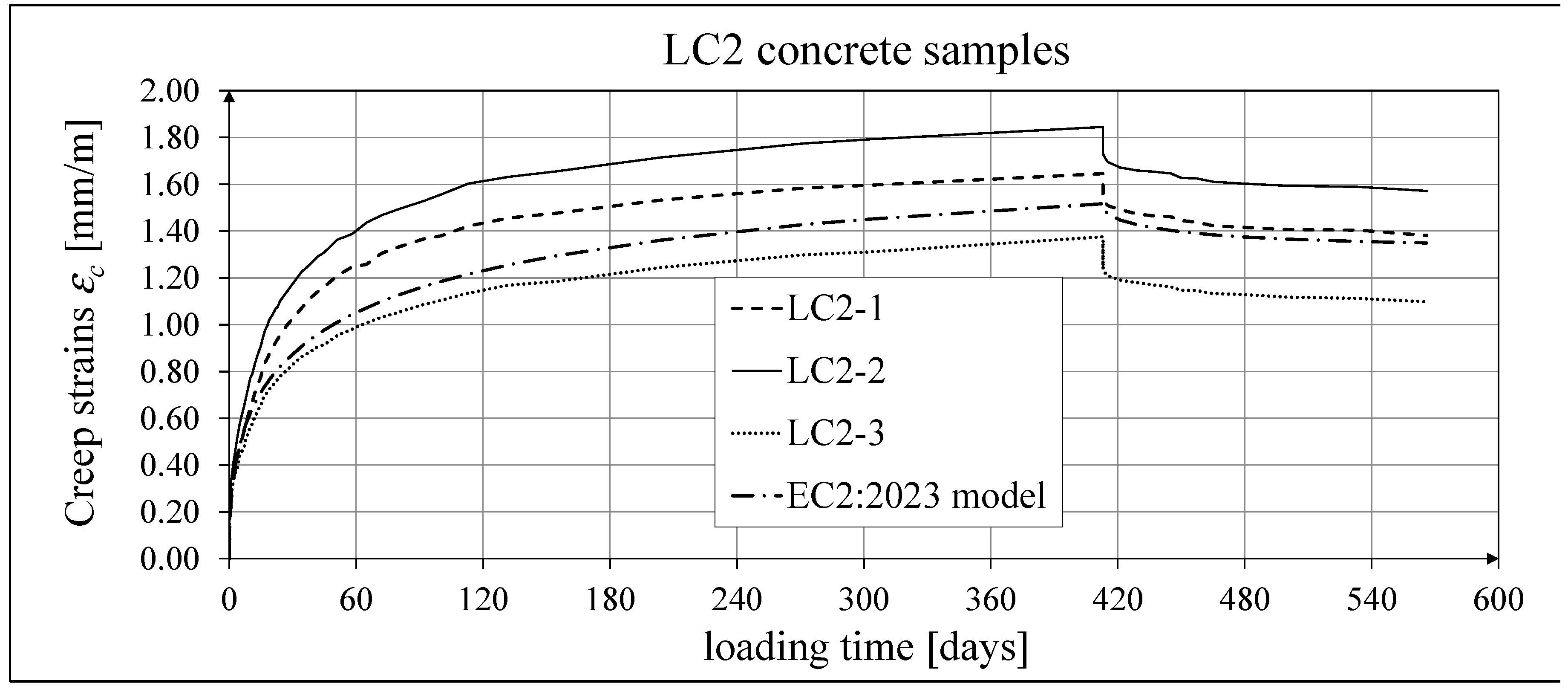

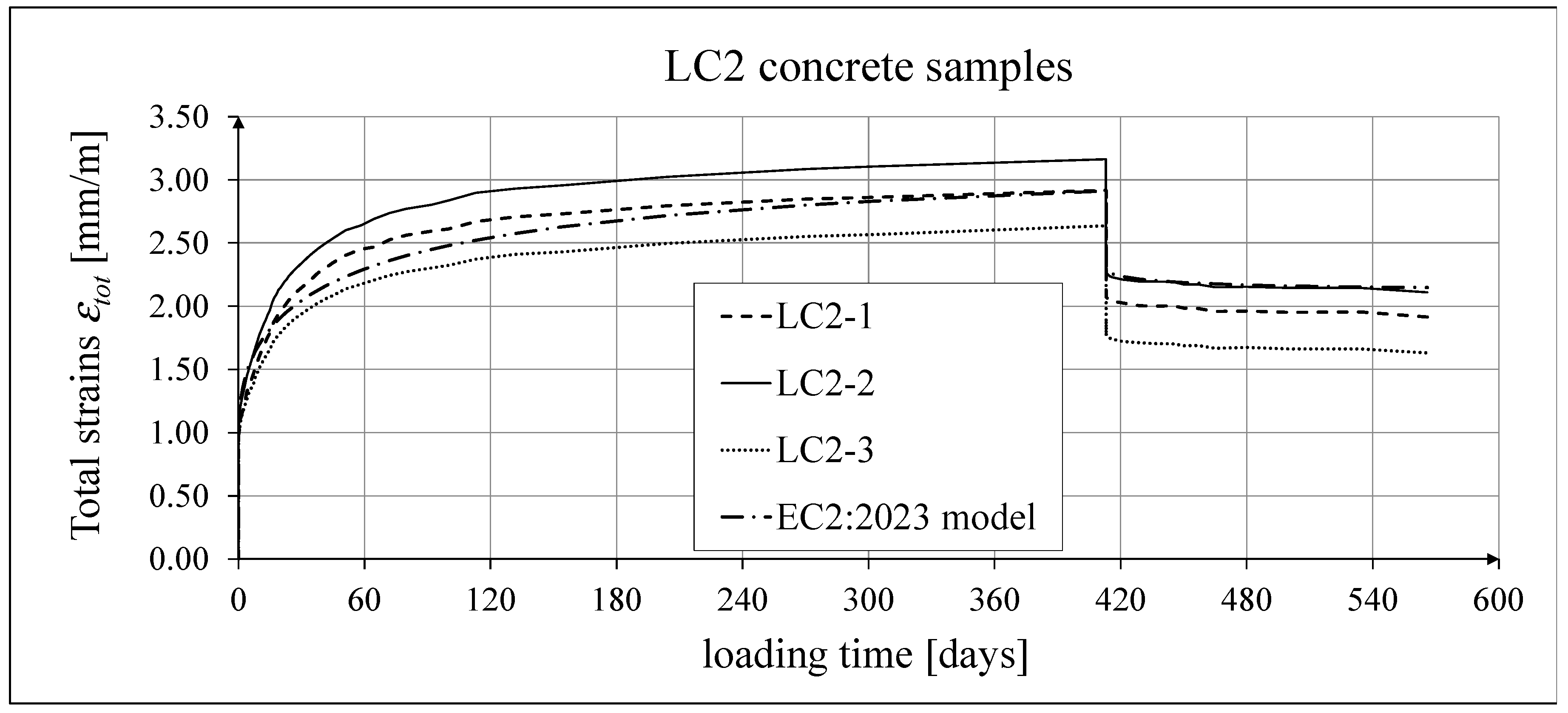

For concrete from the LC1 mix, there were three loading phases, which translated into stress values of 15.55 MPa and two unloading phases, which translated into stress values of 1.56 MPa. The first loading phase lasted for the first 419 days, the first unloading phase lasted until day 572 after the first load application, and the loading-unloading process lasted until 1050 days;

For concrete from the LC2 mix, there were three loading phases, which translated into stress values of 16.96 MPa and two unloading phases, which translated into stress values of 1.70 MPa. The first loading phase lasted for the first 413 days, the first unloading phase lasted until day 566 after the first load application, and the loading-unloading process lasted until 1044 days.

The results of creep strains for LC1 concrete are shown in

Table 3 for the loading time

t = 419 days, and the results of creep strains for LC2 concrete are shown in

Table 4 for the loading time

t = 413 days. Creep tests were performed on 3 samples of LC1 concrete and 3 samples of LC2 concrete, which was due to equipment limitations in the laboratory. For this reason, the deformations of each sample were monitored individually, and the average values were determined only to determine the average creep coefficient obtained from three samples for both of the above concretes. The results concerning the creep strains and total strains of the LC1 concrete samples are shown in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, respectively, where the first loading phase lasted for 419 days and the first unloading phase lasted until 572 days after the first load application. The results concerning the analogous strains of the LC2 concrete samples for the first loading phase lasting for 413 days and the first unloading phase lasting until 566 days after the first load application are shown in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17, respectively.

Theoretically, the creep coefficient, which is calculated as the ratio of creep strains to elastic strains:

ϕ =

ε c /

ε e, is determined for

t = ∞, but practically after a period of not less than 1 year [

62]. The average creep coefficient obtained from three samples of concrete LC1 was about 2.10 for the loading time

t = 419 days (which is consistent with the data given in

Table 3), and in the case of concrete LC2 it was about 1.90 for the loading time

t = 413 days (which is consistent with the data given in

Table 4). The average creep coefficient obtained in the work [

13] for both concretes was from about 0.59 to 0.60, which differs from both the results of these tests and the predictions of the code models [69,74−76]. The results for LC2 concrete are characterized by a certain scatter, which is due to the unintentional inhomogeneity of the LC2 mix, which in turn results from the conditions of aggregate preparation before the concrete mix was made (outside the ITB laboratory).

3.2.5. Measurement Uncertainty of Strains

Measurement uncertainty of total (

ε tot), elastic (

ε e) and creep strains (

ε c) of LC1 lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate after the loading time

t = 419 days is given in

Table 3, where

U – expanded measurement uncertainty, stated as the combined standard measurement uncertainty multiplied by the coverage factor

k = 2 such that the coverage probability corresponds to approximately 95%.

Measurement uncertainty of total, elastic and creep strains of LC2 lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate after the loading time

t = 413 days is given in

Table 4, where

U and

k – as above.

The determined expanded uncertainty of the measurement (U) in percentage terms did not exceed the following values:

2.75% for total strains (ε tot) of LC1 lightweight concrete and 2.65% for LC2 concrete;

5.56% for elastic strains (ε e) of LC1 lightweight concrete and 4.94% for LC2 concrete;

4.58% for creep strains (ε c) of LC1 lightweight concrete and 5.07% for LC2 concrete.

The expanded measurement uncertainty

U (defined as above) of shrinkage strains determined by the Amsler method (

ε sA) for lightweight concrete LC1 at the age of 270 and 325 days (

ε sA = 0.58 mm/m) and the shrinkage of lightweight concrete LC2 at the age of 270 and 319 days (

ε sA = 0.61 mm/m - see

Figure 12) is

U = 0.03 mm/m. The expanded measurement uncertainties U of shrinkage strains determined in this way in percentage terms were: 5.2% for lightweight concrete LC1 at the age of 270 and 325 days and 4.9% for lightweight concrete LC2 at the age of 270 and 319 days.

As can be seen, the measurement uncertainties obtained for the rheological strain test results are slightly higher than those obtained for the strength test results – due to the type of sensors used for long-term strain measurements, but nevertheless they are quite small compared to the dispersion of the rheological strain measurement results.

3.3. Analytical Results for Standard Rheological Models

3.3.1. Analytical Results for Secant Modulus of Elasticity Models

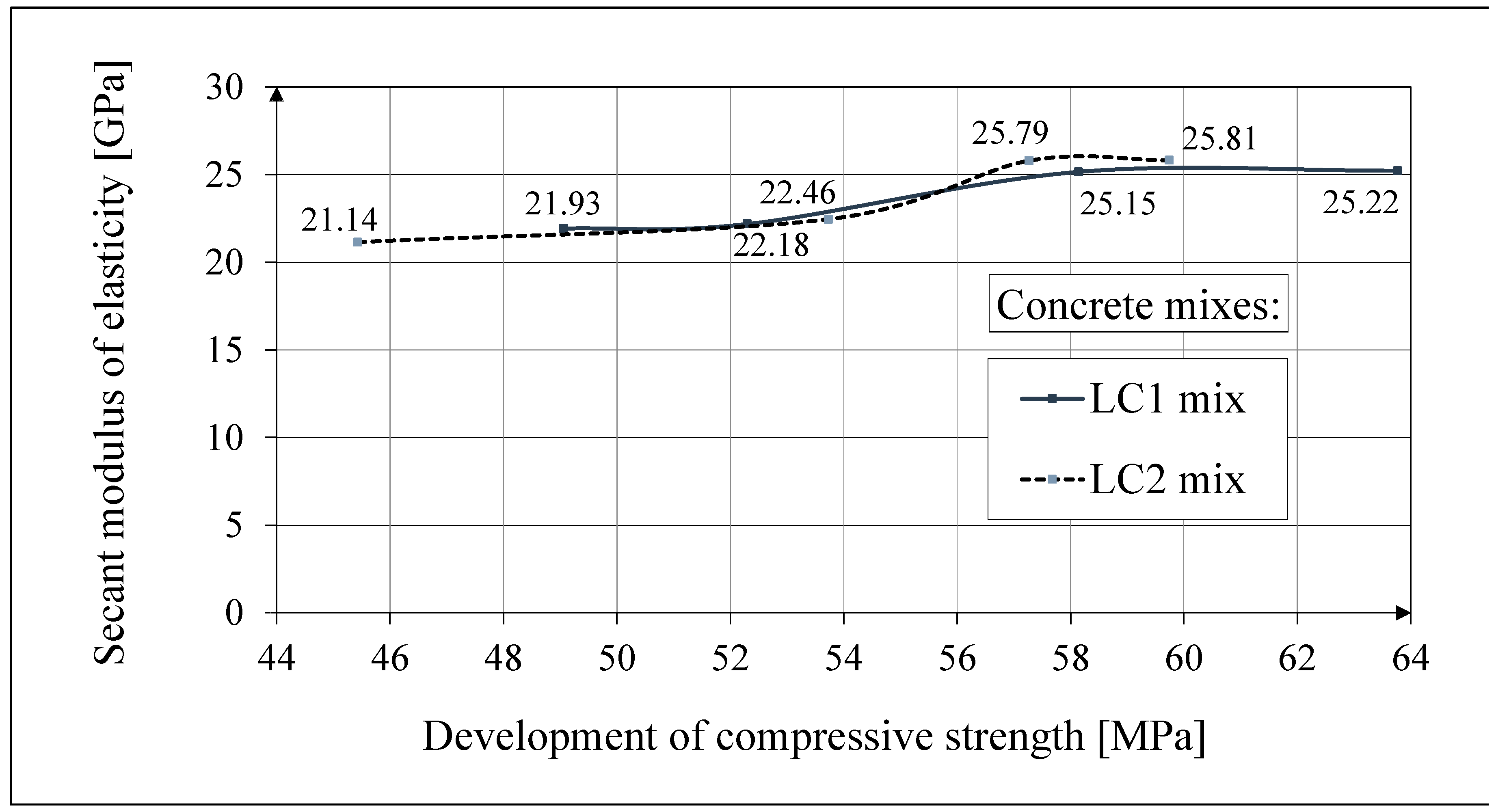

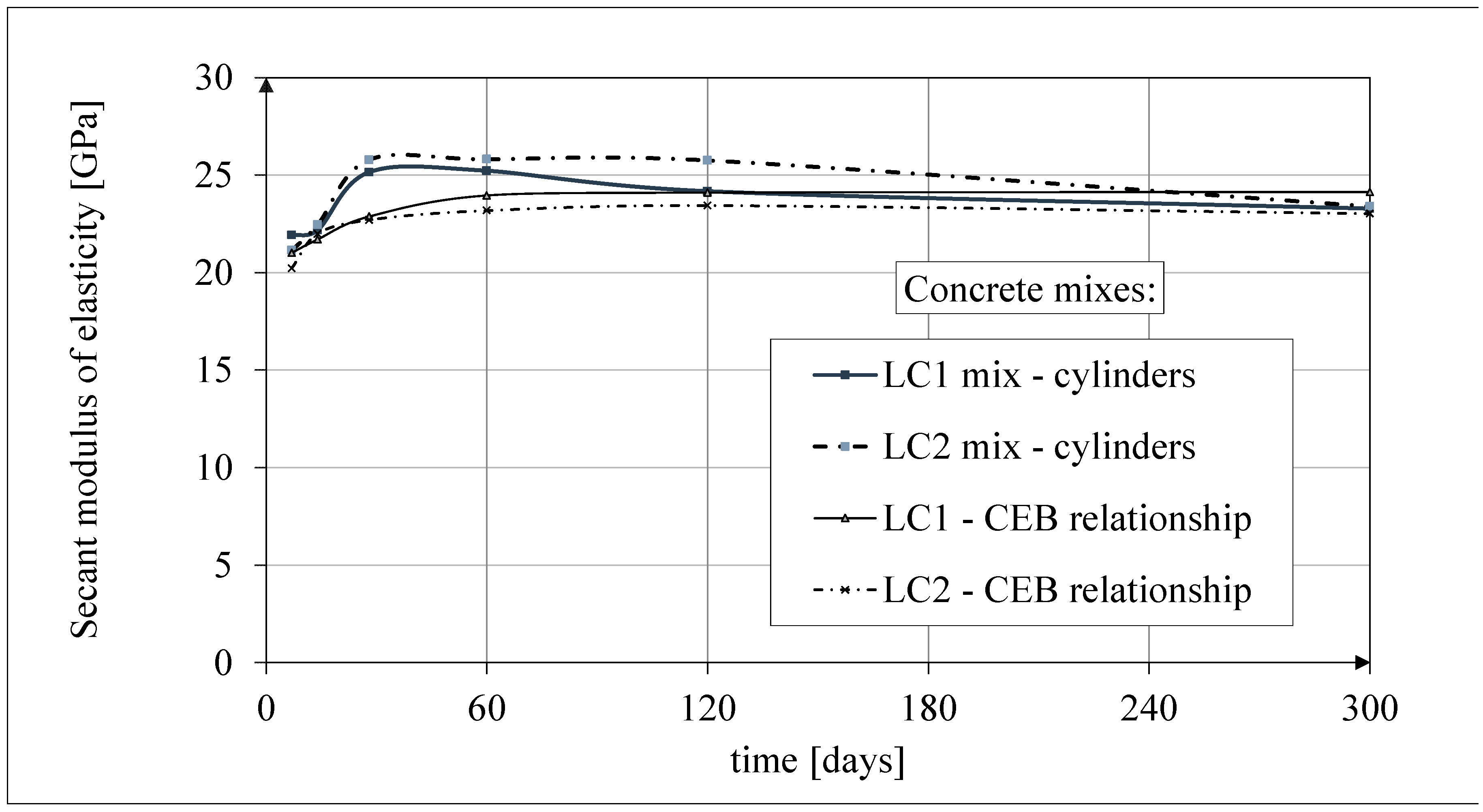

The secant modulus of elasticity can be represented in relation to the compressive strength of concrete by the formula following the

CEB-FIP Recommendations [

77], and in relation to time as by the formula given in Eurocode 2 [

69]. The mutual empirical relation of the secant modulus of elasticity of concrete in relation to the compressive strength is proposed herein by analogy with the

CEB-FIP Recommendations [

77] by means of the following empirical relationship:

Based on the research, the following experimental constant was determined: β = 3.0, where fc is expressed in MPa, while Ec is expressed in GPa.

The comparison of the test results of the secant modulus of elasticity of concrete in relation to the compressive strength of concrete samples made of two concrete mixes LC1 and LC2 is shown in

Figure 18. The results of this comparison were published earlier in the paper [

54]. Comparisons of the test results of the secant modulus of elasticity of concrete as a function of time [in days] and the analytical results according to the

CEB-FIP Recommendations [

77] for the concrete samples made of two concrete mixtures, LC1 and LC2, and their mutual relationship are presented in

Figure 19. The results of these comparisons up to 60 days of concrete age were published earlier in the article [

54].

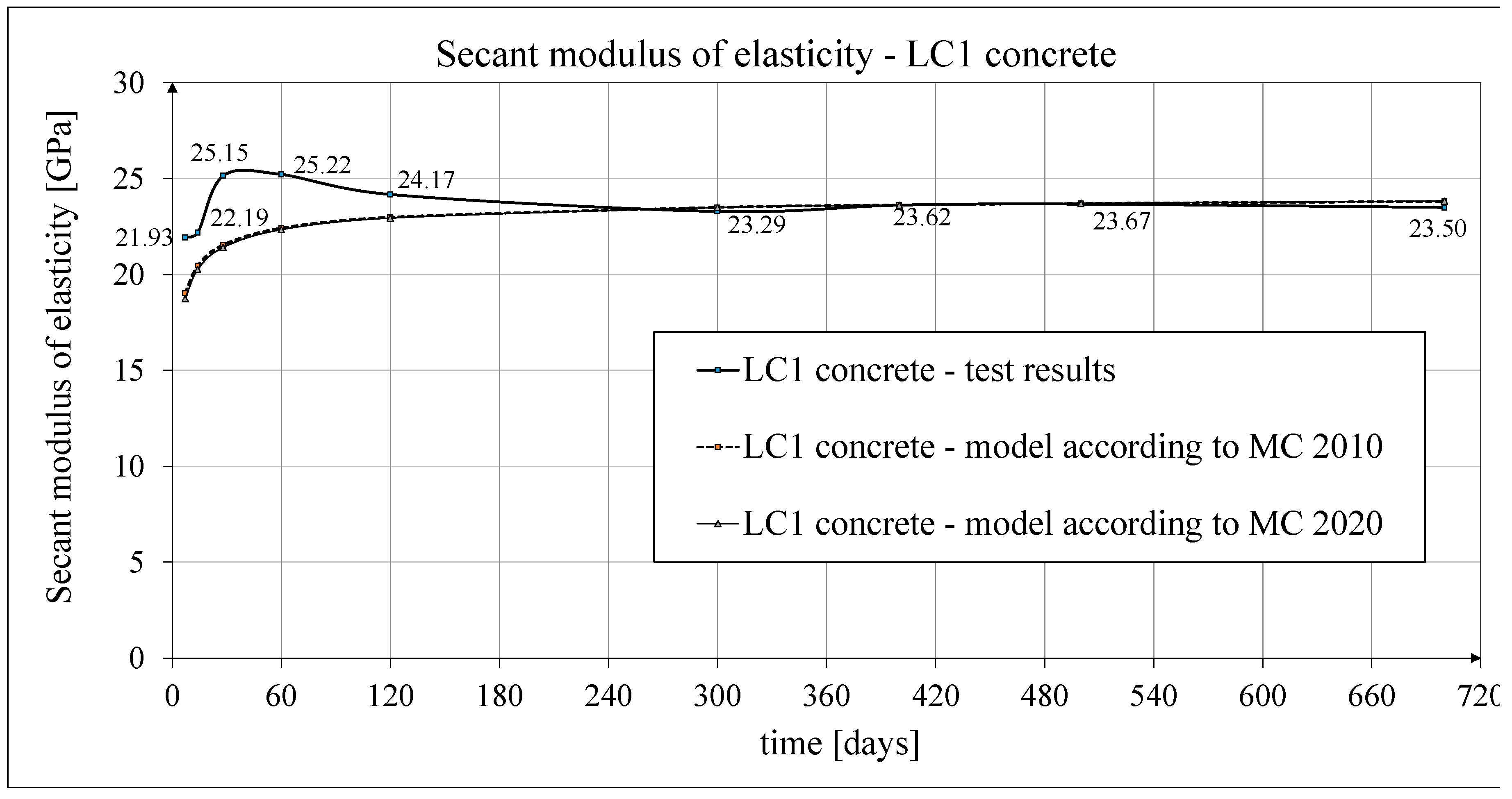

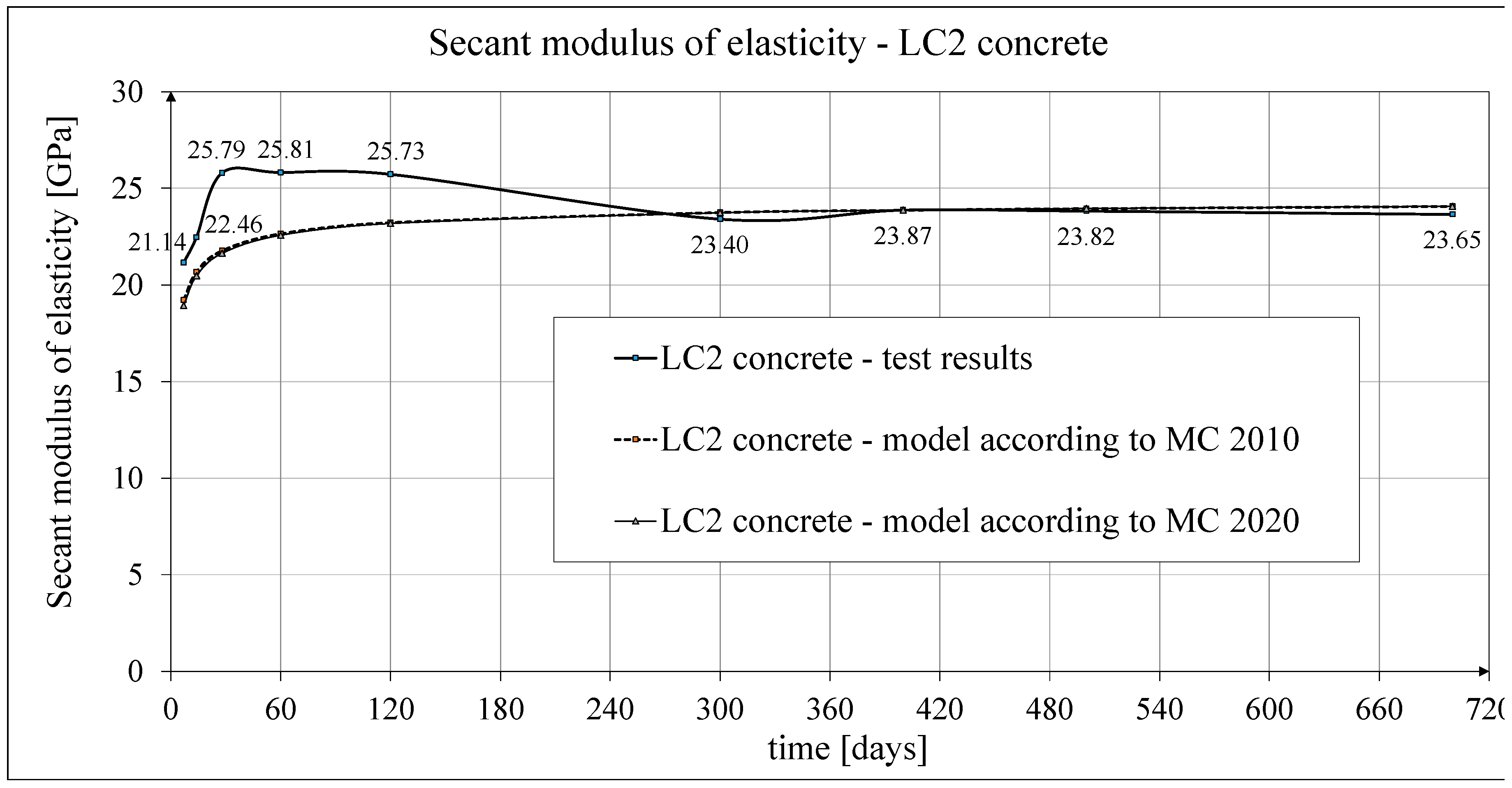

The development of the secant elasticity modulus of concrete in time for the samples made of two concrete mixtures, LC1 and LC2, as well as analytical results for this parameter obtained by the formula contained in EC2:2004 [

69], are shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21, respectively. Comparison of the secant modulus of elasticity for LC1 and LC2 concrete samples according to tests and models of the pre-standards: MC 2010 [

75] and MC 2020 [

76] (the same model as in EC2:2023 [

74]), is presented in

Figure 22 and

Figure 23, respectively.

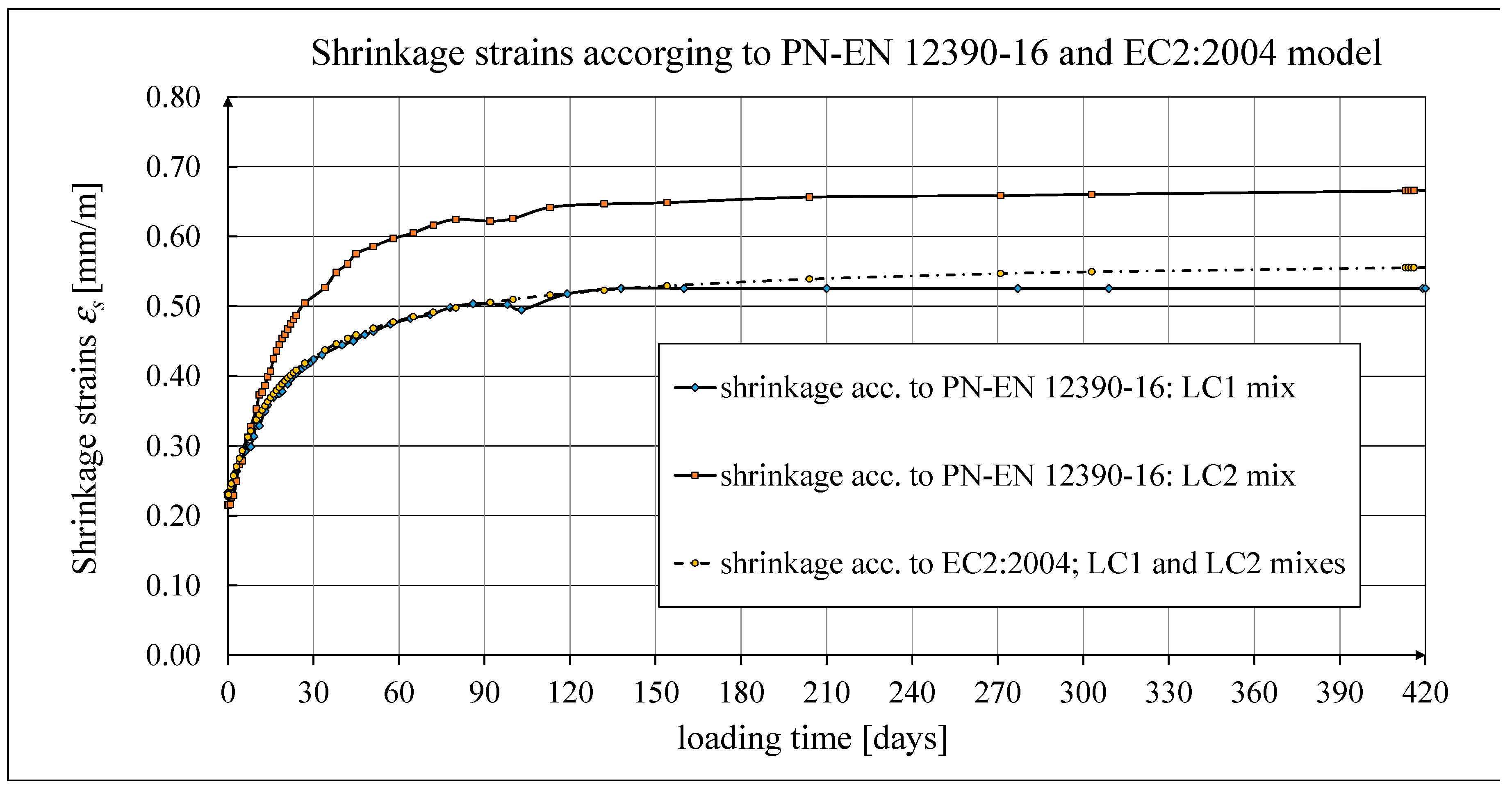

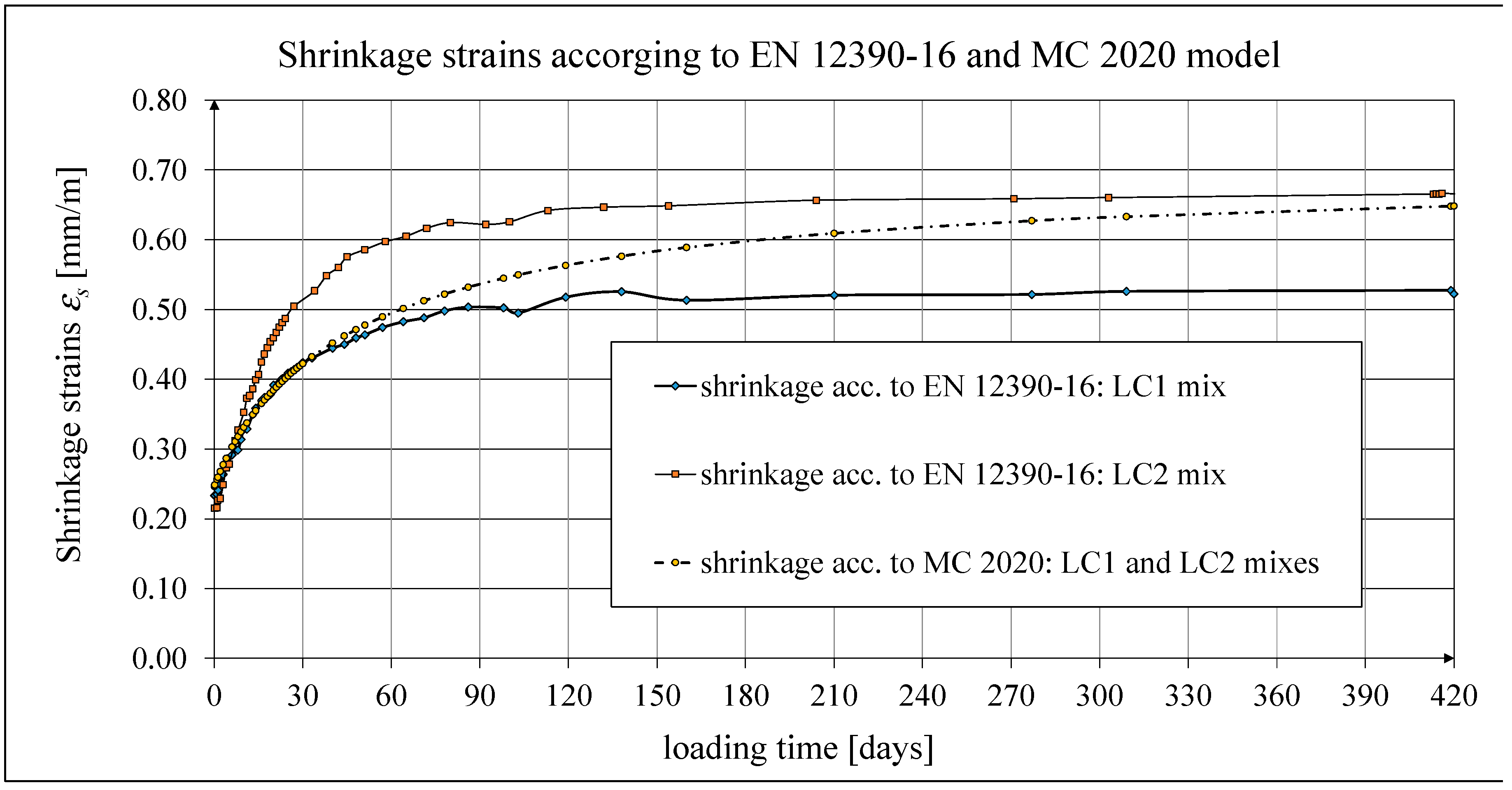

3.3.2. Analytical Results for Shrinkage Models

The description of shrinkage development was adopted according to the EC2:2004 model [

69] and, for comparison, according to the EC2:2004 model [

69]. The results of the shrinkage development tests of LC1 and LC2 concrete samples, conducted using the Amsler method [

67] and the shrinkage values determined for comparison according to the EC2:2004 model [

69], are presented in

Figure 12. The obtained results in terms of shrinkage strains are much higher than in the cited paper [

9]. Shrinkage strains of concrete samples LC1 and LC2 tested using the Amsler method [

67] and strains determined for comparison applying the EC2:2023 model [

74] are shown in

Figure 24.

The test results were compared with the calculation results based on the models according to the EC2:2004 standard [

69] and to the EC2:2023 standard [

74] taking into account the characteristics of lightweight concrete class LC 45/50 according to [

69], the concrete age at the beginning of drying

ts = 14 days and the drying shrinkage factor

η = 1.2 in both models. The test results for two concrete mixtures: LC1 and LC2, conducted according to the EN 12390-16 standard [

68], were compared to the shrinkage values determined according to the EC2:2004 model [

69] (

Figure 25) and the standard EC2:2023 model [

74], and thus the MC 2010 [

75] and MC 2020 [

76] models (

Figure 26), assuming in both models the concrete age at the beginning of drying

ts = 21 days and the drying shrinkage factor

η = 1.2. In the case of tests using the Amsler method, the samples were stored in constant temperature and humidity conditions, but without humidification. In the case of tests according to the EN 12390-16 standard [

68], the concrete blocks from the LC1 and LC2 mixtures were stored in the same conditions, except that the samples were taken only after 28 days from the production of these concrete blocks, which was less conducive to drying of the samples. Therefore, in the tests conducted in accordance with EN 12390-16 [

68], a later age of concrete at the beginning of drying was assumed. All shrinkage deformation tests using the standard method [

68] were carried out in a special creep test cabin for 1050 days for LC1 concrete and 1044 days for LC2 concrete, however, after a period of approximately half a year from the commencement of loading of the samples, the shrinkage stabilized and further results after a period of 420 days are not presented in this paper.

3.3.3. Analytical Results for Creep Models

Creep measurements were carried out on samples taken from two concrete mixes: LC1 and LC2 (see

Figure 6). Creep tests were carried out on three samples of LC1 concrete and three samples of LC2 concrete. The charts included in the text show the results of measurements of the creep strains only and the total strains of the samples. The values of creep strains are defined as the difference between total strains and elastic and shrinkage strains (measured on cylindrical specimens using the standard method [

68]). Creep deformation analysis was also carried out on the basis of seven rheological models. However, the presented charts show the results obtained using the models given in the standards EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] and EN 1992-1-1:2023 [

74], assuming LC 45/50 concrete class,

RH = 50 %,

h0 = 47 mm, but with appropriate correction factors according to standards (

ηE,

ξc). The correction factors (

ξc) were determined in accordance with the standard EN 1992-1-1:2023 [

74] by minimizing the sum of squares of the differences between the model estimation and the experimental results. When comparing the results of the tests of creep strains of LC1 concrete with the results of calculations according to EC2:2004 standard [

69] (at

ηE = 0.67 as above), the resulting correction factor was applied to the creep curve for the initial load, determined by the least square error method, amounting to

ηE ξc = 1.28, and in the case of LC2 concrete, the resulting factor

ηE ξc = 1.24 determined in the same way was applied. This ensured the consistency of the results for the EC2:2004 model and for LC1 concrete with the test results for the loading period from 0 to 419 days and for LC2 concrete with the test results from 0 to 413 days. However, in the case of creep deformations due to unloading occurring after a period of 419 and 413 days, for both concretes, respectively, only a correction factor

ηE was applied, because in the pre-standard MC 2020 [

76] and in the standard EN 1992-1-1:2023 [

74] no other factors are specified for unloading phase. A comparison of the creep strains of concrete samples LC1 and LC2 according to the tests and the model of the EC2:2004 standard [

69] is shown in

Figure 14 and

Figure 16, respectively, and the comparison of the total strains of both concrete samples according to the tests and the considered model is shown in

Figure 15 and

Figure 17, respectively.

Similarly in the case of comparing the results of creep deformation tests of LC1 concrete with the results for MC 2020 [

76] model in the case of the creep curve for the initial load, the resulting correction factor determined by the method of least square errors

ηE ξc = 1.28 was used, and in the case of LC2 concrete - the correction factor determined in the same way

ηE ξc = 1.24, which ensured compliance of the results for MC 2020 model with the test results for the load period from 0 to 419 days (LC1 concrete) or 413 days (LC2 concrete). In case of unloading occurring after a period of 419 and 413 days for both concretes, respectively, only correction factor

ηE was applied, because the pre-standard MC 2020 [

76] does not specify other factors for unloading phase. The comparison of the creep strains of concrete samples LC1 and LC2 according to the tests and the model of the standard EN 1992-1-1:2023 [

74] is presented in

Figure 27 and

Figure 29, respectively, and the comparison of the total strains of the samples of both concretes according to the tests and EC2:2023 model is presented, respectively, in

Figure 28 and

Figure 30.

The results in the case of LC2 concrete are characterized by a certain dispersion, which resulted from a certain heterogeneity of the LC2 mix, which in turn resulted from the conditions of preparation of the aggregate before making the concrete mixture (outside the ITB laboratory). Further research is planned in this regard.

4. Discussion

The performed tests allowed us to determine the presented above strength and long-term parameters of concretes with lightweight aggregate derived from ashes. The entire research process includes readings taken over a period of approximately three years from the time the mixtures were prepared, although the current paper describes the results obtained over a period of just over a year and a half. The empirical mutual relations between the secant modulus of elasticity of concrete and the compressive strength as well as the development of these parameters over time were also determined.

The latest research carried out at the ITB Laboratory of Building Structures, Geotechnics and Concrete confirmed the expediency of using lightweight concrete with a special ceramic, sintered aggregate derived from ashes for prestressed structures. Two types of lightweight concrete were tested, with the W/C ratio for the LC1 mix equal to 0.4 and for the LC2 mix equal to 0.5, respectively, obtained by slightly modifying the mixture compositions. These tests allowed us to determine the strength parameters of this concrete after 7, 14, 28, 60, 120 and 300 days. The compressive strength of the discussed lightweight concrete after 28 days was 57–58 MPa, according to the tests. As expected, the LC1 concrete mix obtained slightly higher strength and lower shrinkage than the LC2 concrete mix. The obtained concrete secant modulus of elasticity, amounting to approx. 25 GPa after 28 days is slightly lower than in the case of an analogous plain concrete, but the influence of this parameter is compensated by the lower volume weight of the lightweight concrete in a finished structure. The results obtained in terms of short-term features do not differ significantly from the results presented in [

13], which was confirmed in previous works of the authors ([

54,

55]).

Significant differences, however, concern the rheological characteristics. In terms of shrinkage tests, the values obtained for the concrete age of about 116 days for both LC1 and LC2 concretes are almost twice as high as in the cited works [9−15] and they are higher than the values appropriate for plain concrete which, on the other hand, complies with the standards [

69,

74]. In terms of concrete creep strains, it was found that the average final creep coefficient for LC1 concrete samples was about 2.1 for the loading time

t = 419 days, and for the LC2 concrete samples it was about 1.9 for the loading time

t = 413 days. It can be remarked that for the concrete age of about 116 days, the values of the creep coefficient for both LC1 and LC2 concretes were approximately three times higher than in the cited works [9−15], but they do not differ from the values specific to plain concrete, which complies with the standard [

69]. These differences result from several reasons, including different research methodologies. The course of creep deformations is correctly modelled by code methods ([

69,

74,

75,

76]), albeit with appropriate correction factors that should be determined in order to minimize the sum of the squares of differences between the model estimation and the experimental results [

76].

However, when comparing the results of the analyses of total deformations and creep deformations obtained on the basis of the standard model according to EC2:2004 [

69] with the results obtained on the basis of models according to the pre-standards MC 2010 [

74] and MC 2020 [

76] (cf. graphs in

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 with graphs in

Figure 27,

Figure 28,

Figure 29 and

Figure 30) it can be concluded that the modifications introduced to EC2:2004 model do not improve the approximation of the test results in the case of the type of concrete under consideration, which is also visible in relation to the comparison of the test results and shrinkage deformation analyses.

In general, it is necessary to remark that the results presented in this article were obtained under the constant laboratory conditions. Built-in concrete exposed to various external factors may change its strength and mechanical properties depending on how it was made. When using these results in practice, the method of concrete production and the actual conditions in which the concrete was laid should be taken into account because the behavior of the lightweight concrete in question is influenced by technological factors.

5. Conclusions

Summing up, the current research results give a broader view of the possibilities of using lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate in modern construction and the development of their strength parameters over time. The presented results will be helpful in the design of lightweight concrete structures and components, including prestressed structures, where the knowledge of these data is necessary for the correct structural design.

Moreover, reusing waste materials is now an environmental priority. As a result, the reuse of ashes for the production of concrete aggregate may in the future reduce the mining of raw materials and the use of natural aggregates in construction. The preservation of natural deposits also contributes to the protection of the environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M. Lewiński, P. Więch and Z. Fedorczyk; methodology, P.M. Lewiński, Z. Fedorczyk, P. Więch and Ł. Zacharski; software, P.M. Lewiński and Z. Fedorczyk; validation, Z. Fedorczyk, P. Więch and Ł. Zacharski; formal analysis, P. Więch; investigation, Z. Fedorczyk, P. Więch and Ł. Zacharski; resources, P.M. Lewiński and P. Więch; data curation, P.M. Lewiński, Z. Fedorczyk, P. Więch and Ł. Zacharski; writing—original draft preparation, P.M. Lewiński; writing—review and editing, P.M. Lewiński; visualization, P.M. Lewiński, Z. Fedorczyk, P. Więch and Ł. Zacharski; supervision, P.M. Lewiński; project administration, P.M. Lewiński; funding acquisition, P.M. Lewiński. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by the Building Research Institute (ITB), grant number NZK-100.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate described in the article is currently used in prestressed concrete bridge structures. Information on these structures is subject to NATO restrictions due to their dual use (civil and military), and detailed source data for the construction of these bridge structures is not publicly available. For this reason, it is not possible to provide detailed source data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Building Research Institute (ITB) for financial support in implementing ITB research project No. NZK-100. Moreover, the authors would like to thank Mrs. Anna Rogowska for her help in preparing the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ITB |

Instytut Techniki Budowlanej (Building Research Institute) |

| LSA |

Lightweight Sintered Aggregate |

| LWAC |

Lightweight Aggregate Concrete |

| IMiKB |

Instytut Materiałów i Konstrukcji Budowlanych (Inst. of Building Mater. & Struct.) |

| W/C |

Water/Cement Ratio |

| LC |

Lightweight Concrete |

| CEM |

Cement Class |

| CEB-FIP |

the merger of CEB and FIP |

| CEB |

Euro-International Committee for Concrete |

| FIP |

International Federation for Prestressing |

| fib |

International Federation for Concrete (the merger of CEB and FIP) |

| MC 2010 |

Model Code 2010 |

| MC 2020 |

Model Code 2020 |

| EC2 |

Eurocode 2 |

| EC2:2004 |

EN 1992-1-1:2004 Eurocode 2 |

| EC2:2023 |

EN 1992-1-1:2023 Eurocode 2 |

References

- Łuczaj, K.; Urbańska, P. Certyd – new lightweight high-strength sintered aggregate (in Polish). Mat. Bud. 2015, 12, 42–4. [CrossRef]

- Domagała, L. Structural Lightweight Aggregate Concrete (in Polish), Monografia 462, 1st ed.; Cracow Univ. of Techn. Publ. House: Cracow, Poland, 2014. https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/resources/25702.

- Domagała, L.; Podolska, A. Effect of Lightweight Aggregate Impregnation on Selected Concrete Properties. Materials 2022, 15, 1, 19. [CrossRef]

- Domagała, L. A Study on the Influence of Concrete Type and Strength on the Relationship between Initial and Stabilized Secant Moduli of Elasticity. Solid State Phenom. 2017, 258, 566–56. [CrossRef]

- Domagała, L. The influence of the type of coarse aggregate on the mechanical properties of structural concrete (in Polish). Zeszyty Nauk. Polit. Rzesz., Bud. i Inż. Środ. 2011, 58, 3/III, 299–306.

- Domagała, L. Size Effect in compressive strength tests of cored specimens of lightweight aggregate concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 5, 118. [CrossRef]

- Mieszczak, M. Application of lightweight concrete to construction, especially for prestressed floor slabs (in Polish). Techn. Issues. 2016, 4, 55–61. file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/full_055-061zastsowanie.pdf.

- Mieszczak, M.; Domagała, L. Lightweight Aggregate Concrete as an Alternative for Dense Concrete in Post-Tensioned Concrete Slab. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2018, 926, 140–14. [CrossRef]

- Mieszczak, M.; Szydłowski R. Light aggregate concrete research for the construction of large span slab (in Polish). In Konf. Nauk.-Techn. Konstrukcje Sprężone, Kraków, 18–20 Kwietnia 2018, 1st ed.; Derkowski, W., Gwoździewicz, P., Pańtak, M., Politalski, W., Seruga, A., Zych, M., Eds.; Cracow Univ. of Techn. Publ. House: Cracow, Poland, 2018, pp. 147 – 150 & pdf (11 pp.).

- Szydłowski R.; Mieszczak, M. Analysis of application of lightweight aggregate concrete to construct post-tensioned long-span slabs (in Polish). Inż. i Bud. 2018, 74, 2, 68–72.

- Mieszczak, M.; Szydłowski R. (academic supervisor). Lightweight concrete in prestressed structures (in Polish), Builder 2017, 240, 7, 90 – 93. file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/943435%20(1).pdf.

- Seruga A.; Szydłowski, R. Bond Strength of Lightweight Aggregate Concrete to the Plain Seven-Wire Non-pretensioned Steel Strand. In Building for the Future: Durable, Sustainable, Resilient. Proc. fib Symposium 2023, 1st ed.; Ilki, A., Çavunt, D., Çavunt, Y.S., Eds.; Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, 2023, Volume 1, pp. 1742–175. [CrossRef]

- Szydłowski, R.S.; Łabuzek, B. Experimental Evaluation of Shrinkage, Creep and Prestress Losses in Lightweight Aggregate Concrete with Sintered Fly Ash. Materials 2021, 14, 389. [CrossRef]

- Szydłowski, R.; Kurzyniec, K. Influence of bulk density of lightweight aggregate concrete on strength and performance parameters of a slab-and-beam floor (in Polish). Inż. i Bud. 2018, 74, 3, 162–164.

- Szydłowski, R.; Mieszczak, M. Study of application of lightweight aggregate concrete to construct post-tensioned long-span slabs. Proc. Engr. 2017, 172, 1077–108. [CrossRef]

- Szydłowski, R. Concrete properties for long-span post-tensioned slabs. Mater. Sci. Forum 2018, 296, 122–12. [CrossRef]

- Małaszkiewicz D.; Jastrzębski D. Lightweight self-compacting concrete with sintered fly ash aggregate. Przegl. Nauk.. Inż. i Kształt. Środow. 2018, 27, 3/81, 328–33. [CrossRef]

- Kaszynska M.; Zielinski A. Effect of Lightweight Aggregate on Minimizing Autogenous Shrinkage in Self-consolidating Concrete. Proc. Engr. 2015, 108, 608–61. [CrossRef]

- Fořt J.; Afolayan A.; Medveď I.; Scheinherrová L.; Černý R., A review of the role of lightweight aggregates in the development of mechanical strength of concrete. J. Build. Engr. 2024, 89, 10931. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Ara, G.; Akhtar, U.S.; Mostafa, M.G.; Haque, I.; Shuva, Z.M.; Samad, A. Development of Lightweight structural concrete with artificial aggregate manufactured from local clay and solid waste materials. Heliyon 2024, 10, 15, E3488. [CrossRef]

- Nukah, P.D.; Abbey, S.J.; Booth, C.A.; Oti, J. Evaluation of the structural performance of low carbon concrete. Sustainability 2022, 14, 24, 1676. [CrossRef]

- Nukah, P.D.; Abbey, S.J.; Booth, C.A.; Oti, J. Development of low carbon concrete and prospective of geopolymer concrete using lightweight coarse aggregate and cement replacement materials. Constr. & Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 13629. [CrossRef]

- Sifan, M.; Nagaratnam, B.; Thamboo, J.; Poologanathan, K.; Corradi, M. Development and prospectives of lightweight high strength concrete using lightweight aggregates. Constr. & Build. Mater. 2023, 362, 12962. [CrossRef]

- Babu, D.S. Mechanical and deformational properties, and shrinkage cracking behaviour of lightweight concretes. PhD Thesis, Nation. Univ. of Singapore, Singapore, 2008.

- Bažant, Z.P.; Murphy, W.P. Creep and shrinkage prediction model for analysis and design of concrete structures - model B3, Mater. & Struct. 1995, 28, 180, 357–36. [CrossRef]

- Daneti, S.B.; Tam, C.T.; Tamilselvan, T.; Kannan, V.; Kong, K.H.; Islam, M.R. Shrinkage Cracking Potential of Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. J. of Phys.: Conf. Series 2024, 2779, 012067, IOP Publishin. [CrossRef]

- Montazerian, A.; Nili, M.; Haghighat, N.; Loghmani, N. Experimental and simplified visual study to clarify the role of aggregate-paste interface on the early age shrinkage and creep of high-performance concrete. Asian J. of Civ. Engr. 2021, 22, 1461–148. [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Jiang, J.; Jiao, Y.; Shen, J.; Jiang, G. Early-age tensile creep and cracking potential of concrete internally cured with pre-wetted lightweight aggregate. Constr. & Build. Mater. 2017, 135, 420–42. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Fang, C.; Kuang, W.Q.; Li, D.W.; Han, N.X.; Xing, F. Experimental study on early cracking sensitivity of lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. & Build. Mater. 2017, 136, 173–18. [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Cabo, A.; Lázaro, C.; López-Gayarre, F.; Serrano-López, M.A.; Serna, P.; Castaño-Tabares, J.O. Creep and shrinkage of recycled aggregate concrete, Constr. & Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 7, 2545–255. [CrossRef]

- Domingo, A.; Lázaro, C.; Gayarre, F.L.; Serrano, M.A.; López-Colina, C. Long term deformations by creep and shrinkage in recycled aggregate concrete, Mater. & Struct. 2010, 43, 1147–116. [CrossRef]

- Haghighat, N.; Nili, M.; Montazerian, A.; Yousef, R. Proposing an Image Analysis to Study the Effect of Lightweight Aggregate on Shrinkage and Creep of Concrete, Adv. in Civ. Engr. Mater. 2020, 9, 1, 22–3. [CrossRef]

- Havlásek, P. Creep and Shrinkage of Concrete Subjected to Variable Environmental Conditions. Doctoral Thesis, Czech Techn. Univ. in Prague, Prague, 2014.

- Nukah, P.D.; Abbey, S.J.; Booth, C.A.; Oti, J. Evaluation of the structural performance of low carbon concrete. Sustainability 2022, 14, 24, 1676. [CrossRef]

- Nukah, P.D.; Abbey, S.J.; Booth, C.A.; Oti, J. Development of low carbon concrete and prospective of geopolymer concrete using lightweight coarse aggregate and cement replacement materials. Constr. & Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 13629. [CrossRef]

- Wendling, A.; Sadhasivam, K.; Floyd, R.W. Creep and shrinkage of lightweight self-consolidating concrete for prestressed members. Constr. & Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 205–21. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.Z.; Chen, C.Y.; Ji, T. Effect of shale ceramsite type on the tensile creep of lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. & Build. Mater. 2013, 46, 13–1. [CrossRef]

- Bujnarowski, K.; Grygo, R. Properties of lightweight aggregates for use in construction (in Polish). Instal 2022, 7-8, 71–7. [CrossRef]

- Grygo, R.; Pranevich, V. Lightweight sintered aggregate as construction,n material in concrete structures. MATEC Web of Conf. 2018, 174 () 0200. [CrossRef]

- Grygo, R.; Bujnarowski, K.; Prusiel, J.A. Analysis of the possibility of using plastic post-production waste in construction, Econ. & Environ. 2022, 81, 2 () 241 – 25. [CrossRef]

- Grygo, R.; Bujnarowski, K.; Prusiel, J.A. Using plastic waste to produce lightweight aggregate for RC structures. Econ. & Environ., 2024, 89, 2 () 1 – 1. [CrossRef]

- Prusiel, J.A.; Bujnarowski, K. Ecological aggregate from plastic waste as an alternative to natural aggregate for lightweight concrete (in Polish), Przegl. Bud. 2023, 94, 11-12 () 144 – 14. [CrossRef]

- Przychodzień, P.; Katzer, J. Properties of Structural Lightweight Aggregate Concrete based on Sintered Fly Ash and Modified with Exfoliated Vermiculite, Materials. 2021, 14, 20 () 592. [CrossRef]

- Jaskulski, R.; Dolny, P.; Yakymechko, Y. Thermal and mechanical properties of lightweight concrete with waste copper slag as fine aggregate, Arch. of Civ. Engr. 2021, 67, 3 () 299 – 31. [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, K.; Ryżyński, W. Lightweight aggregate concrete - certyd. Principles of calculation and application in construction (in Polish), 1st ed.; LSA, Białystok, Poland, 2016.

- Łuczaj, K.; Urbańska, P. Certyd - new, lightweight, high-strength sintered aggregate (in Polish), Mater. Bud. 2015, 12, 250 () 42 – 45. https://www.materialybudowlane.info.pl/images/stories/12_2015/42-45.pdf.

- Olszak, P. Certyd lightweight aggregates - a unique construction product (in Polish), Kruszywa: prod. – transp. – zastos. 2016, 4 () 38 – 42. https://www.infona.pl/resource/bwmeta1.element.baztech-cf4822d7-4c8a-4760-aa8b-b0d0036e1649.

- Gołdyn, M.; Krawczyk, Ł.; Ryżyński, W.; Urban, T. Experimental investigations on punching shear of flat slabs made from lightweight aggregate concrete. Arch. of Civ. Engr. 2018, 64, 4, 293 – 30. [CrossRef]

- Gołdyn, M.; Urban, T. Punching Shear Capacity Related to Load Level of the Corner Columns. In Building for the Future: Durable, Sustainable, Resilient. Proc. fib Symposium 2023, 1st ed.; Ilki, A., Çavunt, D., Çavunt, Y.S., Eds.; Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, 2023, Volume 2, pp. 655–666. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-32511-3_68.

- Gołdyn, M.; Urban, T. Hidden capital as an alternative method for increasing punching shear resistance of LWCA flat slabs. Arch. of Civ. Engr. 65, 4 (2019) 309 – 32. [CrossRef]

- Gołdyn, M.; Urban, T. UHPFRC hidden capitals as an alternative method for increasing punching shear resistance of LWAC flat slabs, Engr. Struct. 2022, 271, 11490. [CrossRef]

- Sowa, Ł.; Gołdyn, M.; Krawczyk, Ł.; Urban, T. The concept for determining punching shear capacity of LWAC slabs without shear reinforcement. In Concrete - Innovations in Mater., Design & Struct., Proc. of the fib Symposium 2019, 1st ed.; Derkowski, W. et al. Eds.; Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, 2019, pp. 1692–1699.

- Urban, T.; Gołdyn, M.; Krawczyk, Ł.; Sowa, Ł. Experimental investigations on punching shear of lightweight aggregate concrete flat slabs. Engr. Struct. 2019, 197, 10937. [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.M.; Lewiński, P.M. Mechanical properties of lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate. AMCM 2020, MATEC Web of Conf. 2020, 323, 0100. [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.; Lewiński, P. Structural lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate as a material for strengthening constructions (in Polish). In XVI Konf. Nauk.-Techn.: Warsztat Pracy Rzeczoznawcy Budowlanego, Kielce-Cedzyna, 26-28 Oct. 2020, 1st ed.; Runkiewicz, L., Goszczyńska, B., Eds.; Zarząd Gł. Pol. Zw. Inż. i Techn. Bud.: Warszawa, Poland, 2020, pp. 483–491.

- Chandra, S.; Berntsson, L. Lightweight aggregate concrete. Science, Technology, and Applications, 1st ed.; Noyes Publications / William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, USA, 2002.

- EN 12350-2:2019-07 Testing fresh concrete - Part 2: Making and curing specimens for strength tests, CEN, Brussels 2019.

- EN 206:2013 Concrete - Specification, performance, production and conformity, CEN, Brussels 2019.

- EN 12350-7:2019/AC:2022 Testing fresh concrete - Part 7: Air content - Pressure methods, CEN, Brussels 2019.

- EN 12390-6 Testing fresh concrete - Part 6: Density, CEN, Brussels 2019.

- EN 12390-7:2019 Testing hardened concrete - Part 7: Density of hardened concrete, CEN, Brussels 201.

- Brunarski, L. Testing of mechanical properties of concrete on samples made in moulds (in Polish), Instrukcja 194/98, ITB, Warszawa, 1998.

- EN 12390-13:2013 Testing hardened concrete - Part 13: Determination of secant modulus of elasticity in compression, CEN, Brussels 2013.

- EN 12390-3:2019 Testing hardened concrete - Part 3: Compressive strength of test specimens, CEN, Brussels 2019.

- EN 12390-6:2009 Testing hardened concrete - Part 6: Tensile splitting strength of test specimens, CEN, Brussels 2009.

- EN 12390-5:2019 Testing hardened concrete - Part 5: Flexural strength of test specimens, CEN, Brussels 2019.

- PN-B-06714-23:1984 Mineral aggregates - Testing - Determination of volume changes by Amsler method (in Polish), PKN, Warszawa, 1984.

- EN 12390-16:2019 Testing hardened concrete - Part 16: Determination of the shrinkage of concrete, CEN, Brussels 2019.

- EN 1992-1-1:2004 Eurocode 2: Design of concrete structures - Part 1-1: General rules and rules for buildings, CEN, Brussels 2004.

- Lopez, M.; Kahn, L.F.; Kurtis, K.E. Effect of internally stored water on creep of high-performance concrete. ACI Mater. J. 2008, 105, 3, 265–273. https://www.proquest.com/openview/ 16621cd596d75686c8a8f2c68a242613/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=37076.

- Shen, D.; Jiang, J.; Shen, J.; Yao, P.; Jiang, G. Influence of prewetted lightweight aggregates on the behavior and cracking potential of internally cured concrete at an early age, Constr. & Build. Mater. 2015, 99, 260–27. [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Yang, H.; Xu, X.; Lin, Z.; Lo, T.Y. Effect of cured time on creep of lightweight aggregate concrete. In 5th Int. Conf. on Durabil. of Concr. Struct., June 30-July 1, 2016, 1st ed.; Shenzhen University: Shenzhen, P. R. China, 2016, pp. 134–14. [CrossRef]

- Glanville, W.H. Studies in reinforced concrete. Part II Shrinkage stresses, 1st ed.; Dep. of Sci. & Ind. Res., Build. Res. Tech. Paper 11: London, UK, 1930.

- EN 1992-1-1:2023 Eurocode 2 - Design of Concrete Structures - Part 1-1: General rules and rules for buildings, bridges and civil engineering structures, CEN, Brussels, 2023.

- Model Code 2010, First complete draft, fib Bulletin 55, DCC Siegmar Kästl e. K., Germany, March, 2010.

-

fib Model Code for Concrete Structures (2020), CEB-FIP, Wiley, Lausanne, 2020.

- CEB-FIP International Recommendations for the Design and Construction of Concrete Structures: Vol. 1 - Principles and Recommendations, Bulletin D'Information № 72, 1970.

Figure 1.

Lightweight sintered aggregate: (a) The aggregate; (b) Concrete mix with this aggregate.

Figure 1.

Lightweight sintered aggregate: (a) The aggregate; (b) Concrete mix with this aggregate.

Figure 2.

Gradation curve of 4/10 aggregate.

Figure 2.

Gradation curve of 4/10 aggregate.

Figure 3.

The axial tensile strength test: (a) The device used to test the axial tensile strength; (b) The broken sample after the test; (c) The forms of fracture of the samples.

Figure 3.

The axial tensile strength test: (a) The device used to test the axial tensile strength; (b) The broken sample after the test; (c) The forms of fracture of the samples.

Figure 4.

The tensile strength tests: (a) The device for testing tensile strength at splitting with the broken test specimen; (b) The device for testing bending strength with the broken test specimen.

Figure 4.

The tensile strength tests: (a) The device for testing tensile strength at splitting with the broken test specimen; (b) The device for testing bending strength with the broken test specimen.

Figure 5.

The device used for testing the modulus of elasticity.

Figure 5.

The device used for testing the modulus of elasticity.

Figure 6.

The creep-testing machine.

Figure 6.

The creep-testing machine.

Figure 7.

The compressive strength test results for cubical and cylindrical samples.

Figure 7.

The compressive strength test results for cubical and cylindrical samples.

Figure 8.

The test results of the axial tensile strength.

Figure 8.

The test results of the axial tensile strength.

Figure 9.

The tensile splitting strength results.

Figure 9.

The tensile splitting strength results.

Figure 10.

The comparison of test results for the flexural strength.

Figure 10.

The comparison of test results for the flexural strength.

Figure 11.

The test results for the secant modulus of elasticity.

Figure 11.

The test results for the secant modulus of elasticity.

Figure 13.

The development of shrinkage according to standard tests [

68] and Glanville model [

73].

Figure 13.

The development of shrinkage according to standard tests [

68] and Glanville model [

73].

Figure 14.

Creep strains of LC1 concrete for the first 572 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] model predictions.

Figure 14.

Creep strains of LC1 concrete for the first 572 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] model predictions.

Figure 15.

Total strains of LC1 concrete for the first 572 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] model predictions.

Figure 15.

Total strains of LC1 concrete for the first 572 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] model predictions.

Figure 16.

Creep strains of LC2 concrete for the first 566 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] model predictions.

Figure 16.

Creep strains of LC2 concrete for the first 566 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] model predictions.

Figure 17.

Total strains of LC2 concrete for the first 566 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] model predictions.

Figure 17.

Total strains of LC2 concrete for the first 566 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2004 [

69] model predictions.

Figure 18.

The test results for the secant modulus of elasticity in relation to compressive strength.

Figure 18.

The test results for the secant modulus of elasticity in relation to compressive strength.

Figure 19.

The comparison of test results for secant elasticity modulus with analytical results.

Figure 19.

The comparison of test results for secant elasticity modulus with analytical results.

Figure 20.

The comparison of test results of secant elasticity modulus with EC2:2004 model for LC1 concrete.

Figure 20.

The comparison of test results of secant elasticity modulus with EC2:2004 model for LC1 concrete.

Figure 21.

The comparison of test results of secant elasticity modulus with EC2:2004 model for LC2 concrete.

Figure 21.

The comparison of test results of secant elasticity modulus with EC2:2004 model for LC2 concrete.

Figure 22.

Development of the secant modulus of elasticity of LC1 concrete according to the tests and according to the MC 2010 and MC 2020 models.

Figure 22.

Development of the secant modulus of elasticity of LC1 concrete according to the tests and according to the MC 2010 and MC 2020 models.

Figure 23.

Development of the secant modulus of elasticity of LC2 concrete according to the tests and according to the MC 2010 and MC 2020 models.

Figure 23.

Development of the secant modulus of elasticity of LC2 concrete according to the tests and according to the MC 2010 and MC 2020 models.

Figure 24.

The development of the shrinkage according to the Amsler tests and EC2:2023 model.

Figure 24.

The development of the shrinkage according to the Amsler tests and EC2:2023 model.

Figure 25.

The development of the shrinkage according to EN 12390-16 standard tests [

68] and the EC2:2004 standard model [

69].

Figure 25.

The development of the shrinkage according to EN 12390-16 standard tests [

68] and the EC2:2004 standard model [

69].

Figure 26.

The development of the shrinkage according to EN 12390-16 standard tests [

68] and the EC2:2023 standard model [

74], as well as MC 2010 [

75] and MC 2020 [

76] models.

Figure 26.

The development of the shrinkage according to EN 12390-16 standard tests [

68] and the EC2:2023 standard model [

74], as well as MC 2010 [

75] and MC 2020 [

76] models.

Figure 27.

Creep strains of LC1 concrete for the first 572 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2023 model predictions.

Figure 27.

Creep strains of LC1 concrete for the first 572 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2023 model predictions.

Figure 28.

Total strains of LC1concrete for the first 572 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2023 model predictions.

Figure 28.

Total strains of LC1concrete for the first 572 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2023 model predictions.

Figure 29.

Creep strains of LC2 concrete for the first 566 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2023 model results.

Figure 29.

Creep strains of LC2 concrete for the first 566 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2023 model results.

Figure 30.

Total strains of LC2 concrete for the first 566 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2023 model results.

Figure 30.

Total strains of LC2 concrete for the first 566 days of loading and EN 1992-1-1:2023 model results.

Table 1.

Concrete mixes analogous to the one in the paper [

9].

Table 1.

Concrete mixes analogous to the one in the paper [

9].

| Component |

LC1 Mix |

LC2 Mix |

| |

Volume [kg/m3] |

| CEM I 42,5 N |

409 |

419 |

| Lightweight sintered aggregate Certyd

|

775 |

802 |

| Sand |

682 |

703 |

| Water |

164 |

209 |

| Admixture BV 18

|

3.7 |

3.8 |

| (plasticizer) |

|

|

Admixture SKY 686

(superplasticizer) |

3.7 |

3.8 |

Table 2.

Features of fresh mixes.

Table 2.

Features of fresh mixes.

| Tested feature |

LC1 mix |

LC2 mix |

| Average consistency by cone fall method (slump test) acc. to EN 12350-2 [57] |

145 mm |

105 mm |

| Consistency class |

S3 class |

S3 class |

| acc. to EN 206 [58] |

|

|

| Average air content |

4.35 % |

4.20 % |

| acc. to EN 12350-7 [59] |

|

|

| Fresh concrete mix density acc. to EN 12390-6 [60] |

1960 kg/m3

|

1980 kg/m3

|

Table 3.

Summary of LC1 test results with measurement uncertainty U for t = 419 days.

Table 3.

Summary of LC1 test results with measurement uncertainty U for t = 419 days.

| Sample No. |

ε tot± U

|

ε e± U

|

ε c± U

|

| |

[mm/m] |

[mm/m] |

[mm/m] |

| LC1-1 |

2.55 ±0.07 |

0.72 ±0.04 |

1.54 ±0.07 |

| LC1-2 |

2.66 ±0.07 |

0.76 ±0.04 |

1.61 ±0.07 |

| LC1-3 |

2.56 ±0.07 |

0.74 ±0.04 |

1.53 ±0.07 |

Table 4.

Summary of LC2 test results with measurement uncertainty U for t = 413 days.

Table 4.

Summary of LC2 test results with measurement uncertainty U for t = 413 days.

| Sample No. |

ε tot± U

|

ε e± U

|

ε c± U

|

| |

[mm/m] |

[mm/m] |

[mm/m] |

| LC2-1 |

2.92 ±0.07 |

0.82 ±0.04 |

1.65 ±0.07 |

| LC2-2 |

3.16 ±0.08 |

0.87 ±0.04 |

1.84 ±0.07 |

| LC2-3 |

2.64 ±0.07 |

0.81 ±0.04 |

1.38 ±0.07 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).