1. Introduction

The Prostate cancer (PC) is the second most commonly diagnosed solid tumor and the fifth leading cause of mortality in men worldwide [

1]. While treatment options for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) have expanded and combination therapies have been shown to prolong survival [

2], it is of interest to identify patients who could benefit from less intensive treatment regimen to avoid unnecessary toxicity.

Current clinical parameters for predicting progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in mHSPC are inadequate to fully capture the multifaceted and heterogeneous nature of the disease. The STOPCAP meta-analysis incorporating CHAARTED volume criteria with type of disease presentation (de novo or metachronous) showed that patients with metachronous and low-volume disease experience long survival and do not benefit from the addition of docetaxel. However, in patients with high volume diseases, 5-year PFS and OS rates were similar regardless of disease presentation indicating a lack of effective long-term prognosis discrimination in this group [

3].

Genomic profiling has underscored the significance of tumor suppressor gene (TSG) alterations in PC biology, which has led to the definition of aggressive variant PC (AVPC) a particular form of metastatic castration-resistant PC (mCRPC). AVPC is molecularly defined by combined defects in TP53, RB1 and PTEN (AVPC-TSG), and this genetic signature may predict a favorable response to platinum-based therapies [

4].

On the other hand, AVPC-TSG alterations have also been associated with poor prognosis and androgen insensitivity [

5]. The loss of TP53, RB1, and PTEN drives rapid disease progression and hormonal therapy resistance, a phenomenon well-established in preclinical studies [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] with supporting clinical evidence primarily derived from the mCRPC setting [

12,

13,

14].

While the acquisition of AVPC-TSG alterations has been linked to previous hormonal therapy exposure, these alterations are frequently found in hormone naïve samples as well [

15]. Their predictive and prognostic impact may therefore vary depending on the stage of PC, the timing of their assessment, previous treatment exposure and the presence of isolated or combined defects. This results in a lack of treatment recommendations in clinical PC guidelines based on the presence or absence of these alterations.

In patients with mHSPC treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and androgen receptor pathway inhibitors (ARPI), ancillary studies from the STAMPEDE platform utilizing transcriptome-wide analysis identified PTEN and TP53 loss as negative prognostic factors [

16]. Additionally, a single-institution retrospective study demonstrated that AVPC-TSG altered status (AVPC-TSGalt), defined as the presence of any alteration in one or more AVPC-TSG detected through genomic tumor sequencing, was associated with significantly shorter PFS in patients receiving ADT plus abiraterone compared to those with AVPC-TSG wild-type (AVPC-TSGwt) mHSPC (8.0 months vs. 23.2 months, respectively) [

17].

However, these studies did not evaluate the impact of AVPC-TSG alterations on risk stratification when integrated with clinical variables and did not compare treatment outcomes across different regimens (e.g., ADT monotherapy, ADT + docetaxel, or ADT + ARPI) and other molecular subgroups.

As a result, it remains unclear whether all patients with AVPC-TSGalt mHSPC derive meaningful PFS or OS benefits from ARPI or triplet therapy. Furthermore, the interaction between AVPC-TSG status and established clinical prognostic variables has not been fully explored, leaving their role in refining prognosis and guiding treatment decisions in mHSPC unclear.

Our study aims to address this knowledge gap by evaluating the prognostic value of AVPC-TSG status in a treatment-naïve setting and its predictive role in determining the benefit of ARPI in patients with mHSPC. These findings aim to enhance personalized clinical decision-making, particularly in identifying patients who may benefit from treatment de-escalation or escalation strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

The analysis of this real-world evidence study has been reported in accordance to ESMO Guidance for Reporting Oncology real-World Evidence (ESMO-GROW) recommendations [

18].

This is a single-center retrospective study analyzing data extracted from electronic medical records of patients who consecutively presented with mHSPC and initiated systemic therapy at the Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland between the years 2013 and 2023 with either ADT alone or in association with docetaxel and/or ARPI, who also had tumor tissue genomic testing performed on specimens collected prior to ADT initiation or had archival treatment-naïve tissue available for retrospective analysis. Every patient either signed an informed consent for data collection or was deceased at the time of data analysis. The study was in the scope of a retrospective data collection protocol approved by the local ethical committee and was in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Details on inclusion, exclusion criteria and genomic sequencing analysis can be found in Methods S1–S3.

PFS and OS definitions [

19,

20] are detailed in Method S4. Several demographic and clinical parameters were gathered with genomic data as shown in Methods S4 and S5. Our primary and secondary objectives are described in Method S6 together with exploratory analysis.

Pearson’s chi-square test was employed to examine the association between categorical variables and the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test for continuous measures. AVPC-TSGalt status was defined as the presence of one or more alterations in the TP53 gene, RB1 gene, or genes involved in the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway, as detected by genomic tumor sequencing. Conversely, AVPC-TSGwt status was characterized by the absence of any such alterations. We conducted comparative analysis between patients with AVPC-TSGalt and AVPC-TSGwt mHSPC. PFS and OS were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method, and group comparisons were made using the log-rank test. All statistical comparisons were made with two-tailed tests. Multivariable Cox regression analysis for PFS and OS and test of interaction were performed to assess the independent prognostic value of AVPC-TSG status alongside demographic and clinical variables (CHAARTED volume criteria, de novo/metachronous presentation, ISUP Grade Group) [

21]. AVPC-TSG status was incorporated into relevant clinical variables as detailed in Method S7 and Holm’s correction method was used to compare subgroups [

22]. The results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). All statistical analyses were carried out using R statistical software version 4.4.2 and Jamovi statistical software version 2.5.6. A more detailed explanation of the conducted statistical analysis, including exploratory and sensitivity analysis, can be found in Methods S8 and S9.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

The ESMO-GROW flowchart for real-world evidence studies in oncology is presented in Results S1. During the inclusion period (January 2013–December 2023), 158 mHSPC patients met the inclusion criteria.

Table 1 presents the baseline demographics and clinical variables of the overall population at the time of treatment initiation, distinguishing between those presenting AVPC-TSGalt and those with AVPC-TSGwt mHSPC.

Within the study population, 100 (63.3%) of patients presented with de novo mHSPC, 88 (55.7%) had high volume disease (accordingly to CHAARTED criteria) and 80 (50.4%) had ISUP Grade Group 5 disease. Notably, 7 (4.4%) presented with liver metastasis and 18 (11.4%) with lung metastasis. The overall median PFS was 28.2 months (95%CI: 23.8-39.6; range: 1-129 months), and the median OS was 87.5 months (95%CI: 68.2-NR; range: 1-129 months).

The analyzed tissue samples were derived from radical prostatectomies, prostate biopsies, or transurethral resection of the prostate specimens in 74% of cases, and biopsy of a local or distant metastatic site (lymph nodes, liver, peritoneum, bone, lung, soft tissue) in the remaining cases (

Table S1).

In the overall population, 63 (39.9%) patients presented at least one altered AVPC-TSG (TP53 in 29.7%, RB1 in 1.9%, and PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway in 12.7%), with 7 (4.4%) patients presenting combined AVPC-TSG alterations. Type and frequency of detected alterations are described in

Table S2.

When comparing patients with AVPC-TSGalt versus AVPC-TSGwt tumors, no differences were observed in median age, median PSA at mHSPC diagnosis, or traditional clinical prognostic variables (CHAARTED volume criteria, ISUP Grade Group, disease presentation). Conversely, lung metastases were more common in AVPC-TSGalt tumors (19.9% vs. 6.3%). Notably, the type of mHSPC treatment did not significantly differ between AVPC-TSGalt and AVPC-TSGwt tumors (p=0.64). Among the 58 patients with metachronous mHSPC, 28 (48.3%) received pelvic radiotherapy and 22 (37.9%) ADT in the localized setting.

3.2. Impact of AVPC-TSG Alteration on Survival Outcomes

The effects of AVPC-TSG status on PFS and OS from univariate and multivariate Cox analysis including traditional clinical variables (CHAARTED volume criteria, ISUP Grade Group, type of disease presentation) are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Forest plot for PFS and OS MV Cox analysis are shown in

Figure S1.

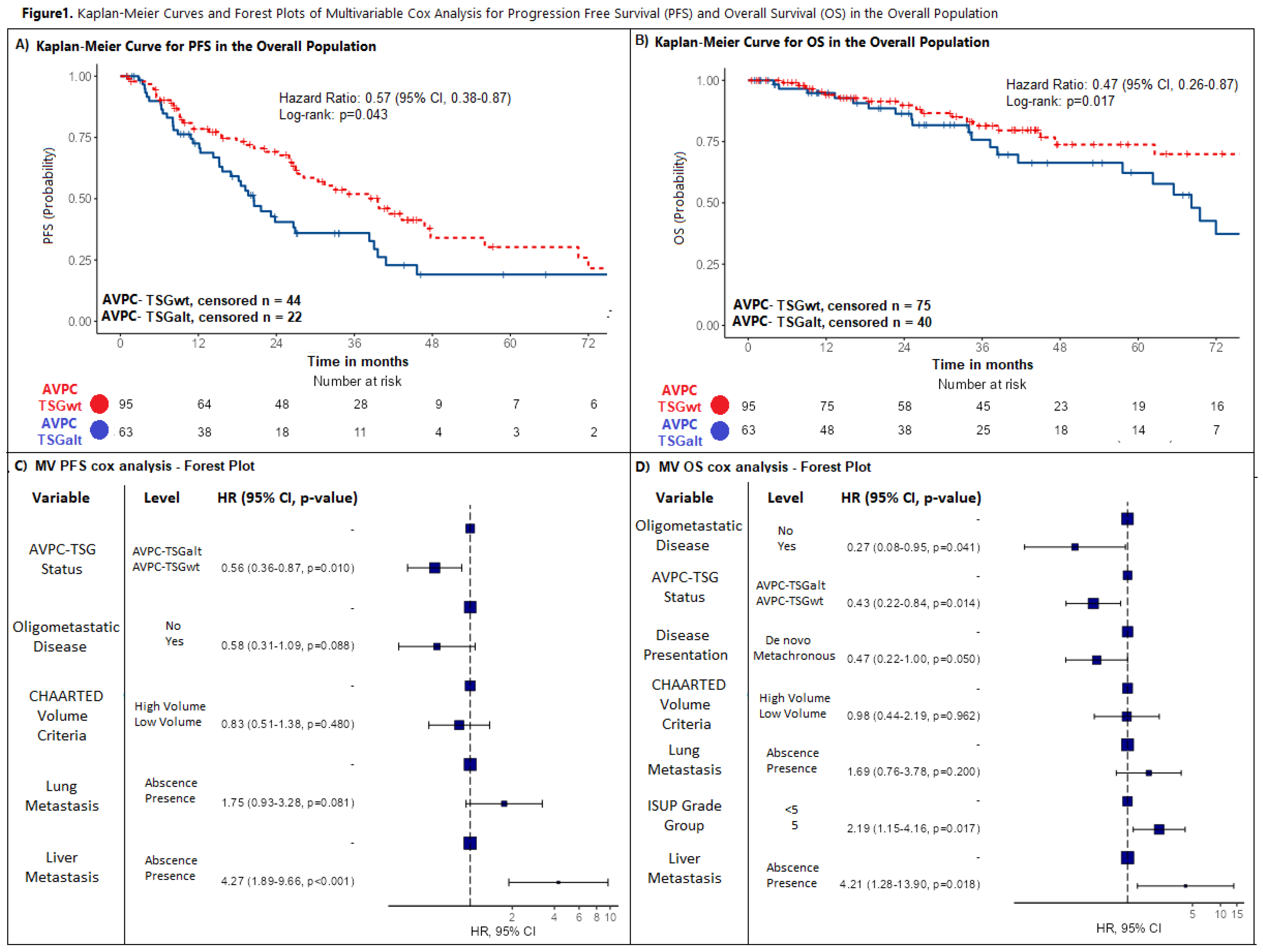

In the overall population, we found AVPC-TSGalt status (defined as the presence of at least one AVPC-TSG alteration) to be an independent negative prognostic factor in both univariate and multivariate Cox analysis for PFS (AVPC-TSGwt versus AVPC-TSGalt: HR:0,51, 95%CI:0.29–0.92, p=0.025; HR:0,58, 95%CI:0.38-0.89, p=0.012, respectively) and OS (AVPC-TSGwt versus AVPC-TSGalt: HR:0,47, 95%CI0.26–0.87, p=0,017; HR:0.48, 95%CI:0.26- 0.91, p=0.015). Median PFS and OS were significantly shorter in AVPC-TSGalt mHSPC population compared to AVPC-TSGwt (PFS: 20.5 versus 39.6 months; OS: 68.2 months versus not reached with a lower 95%CI of 94.6 months) as depicted by the Kaplan Mayer curves in

Figure 1A,B. Tests for interaction between AVPC-TSG status and clinical variables yielded negative results (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

We conducted further MV Cox analysis for PFS and OS including number and site of metastasis (lung or liver metastasis) (

Tables S3 and S4). AVPC-TSG status remained significantly associated with PFS and OS (AVPC-TSGwt versus AVPC-TSGalt: HR:0.56, 95%CI:0.36-0.87, p=0.010; HR:0.43, 95%CI:0.22-0.84, p=0.014, respectively). Liver metastasis was negatively associated with PFS and OS (HR:4.27, p<0.001; HR:4.21, p=0.018), while a positive association was found for oligometastatic disease presentation (HR:0.58, p=0.088; HR:0.27, p=0.041). ISUP Grade Group and type of disease presentation were significantly associated with OS at MV Cox analysis (p=0.017, p=0.050). Conversely, CHAARTED volume criteria was not associated with PFS and OS in MV Cox analysis (p=0.480; p=0.962). Tests for interaction between AVPC-TSG status and clinical variables were all negative (

Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 1C,D shows the forest plots for PFS and OS MV Cox analysis.Importantly, when sensitivity analysis (MV Cox analysis performed with AVPC-TSGalt status and each clinical variable singularly) were performed, AVPC-TSGalt status retained prognostic significance across all models (

Tables S5 and S6).

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier Curves and Forest Plots for Progression Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS) in the Overall Population.

The effect of AVPC-TSGwt status on patient survival outcomes was similar in de novo and metachronous mHSPC, both in terms of PFS and OS, though not always reaching statistical significance (de novo mHSPC PFS: HR:0.53 p=0.020; de novo mHSPC OS HR:0.53 p=0.096; metachronous mHSPC PFS: HR:0.61, p=0.169; metachronous mHSPC OS: HR:0.47, p=0.185) (

Table S7). Patients whose tumors presented with two or more concomitant AVPC-TSG alterations (n=7) showed a trend towards a higher risk of progression and death compared to those with only one alteration (n=56) as shown in

Table S8. However, the small sample size limits definitive conclusions.

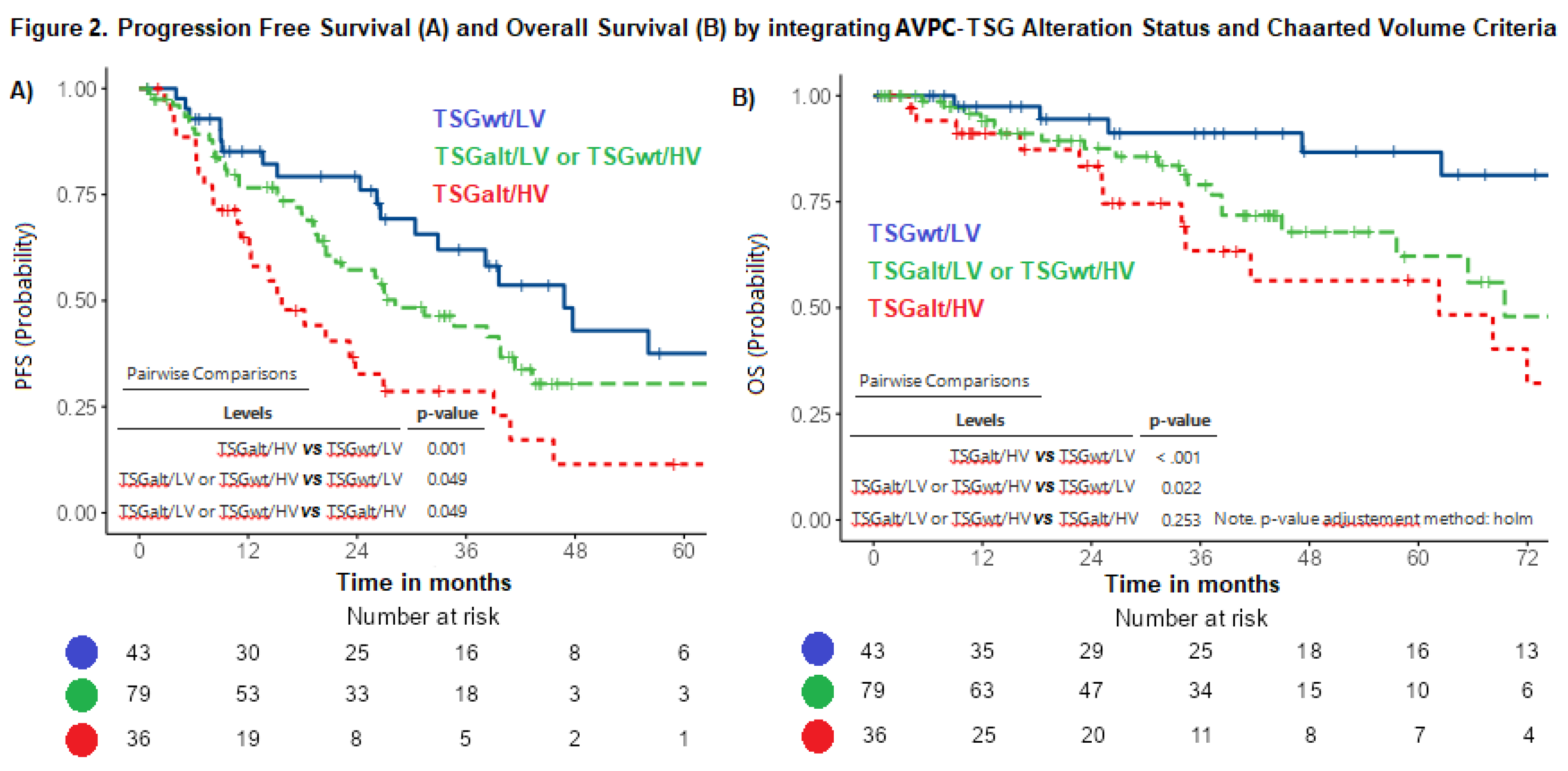

3.3. Refining CHAARTED Criteria Including AVPC-TSG Status

AVPC-TSG status was integrated with CHAARTED clinical criteria to create a new variable with three levels:

- -

“AVPC-TSGwt/LV” (absence of AVPC-TSG alterations and presence of low volume disease)

- -

“AVPC-TSGalt/HV” (presence of both AVPC-TSG alterations and high volume disease)

- -

“AVPC-TSGalt/LV or AVPC-TSGwt/HV” (presence of either AVPC-TSG alteration or high volume disease).

Cox analysis for PFS and OS were conducted together with pairwise comparisons. Subgroup comparison through Holm’s method found statistically significant differences between all the 3 subgroups in terms of PFS (p<0.05) with a similar trend in terms of OS (

Table S9).

We identified a “good risk subgroup” (“AVPC-TSGwt/LV”) with patients having exceptional PFS and OS, a “poor risk subgroup” with poor survival outcomes (“AVPC-TSGalt/HV”) (median PFS: 46,8 versus 15,7 months; median OS: not reached versus 62.3) and an “intermediate risk subgroup”, as depicted by the Kaplan-Meier curves in

Figure 2. Notably, type of mHSPC treatment did not significantly differ across the three subgroups (

Table S10). No PFS differences were noted when comparing patients with “AVPC-TSGalt/LV” to those with “AVPC-TSGwt/HV” mHSPC

(sTable11).

Similarly, we integrated AVPC-TSG status with type of disease presentation and ISUP Grade Group. Cox analyses for PFS and OS, along with pairwise comparisons, are presented in

Tables S12 and S13. Corresponding Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in

Figure S2. Conversely, the integration of clinical variables alone (disease volume, ISUP Grade Groups, and disease presentation) failed to effectively discriminate PFS outcomes when AVPC-TSG alterations were not considered (

Table S14).

Figure 2: Progression Free Survival (A) and Overall survival (B) by integrating AVPC-TSG alteration status and CHAARTED Volume Criteria.

3.4. Predictive Value of AVPC-TSG Alteration Status

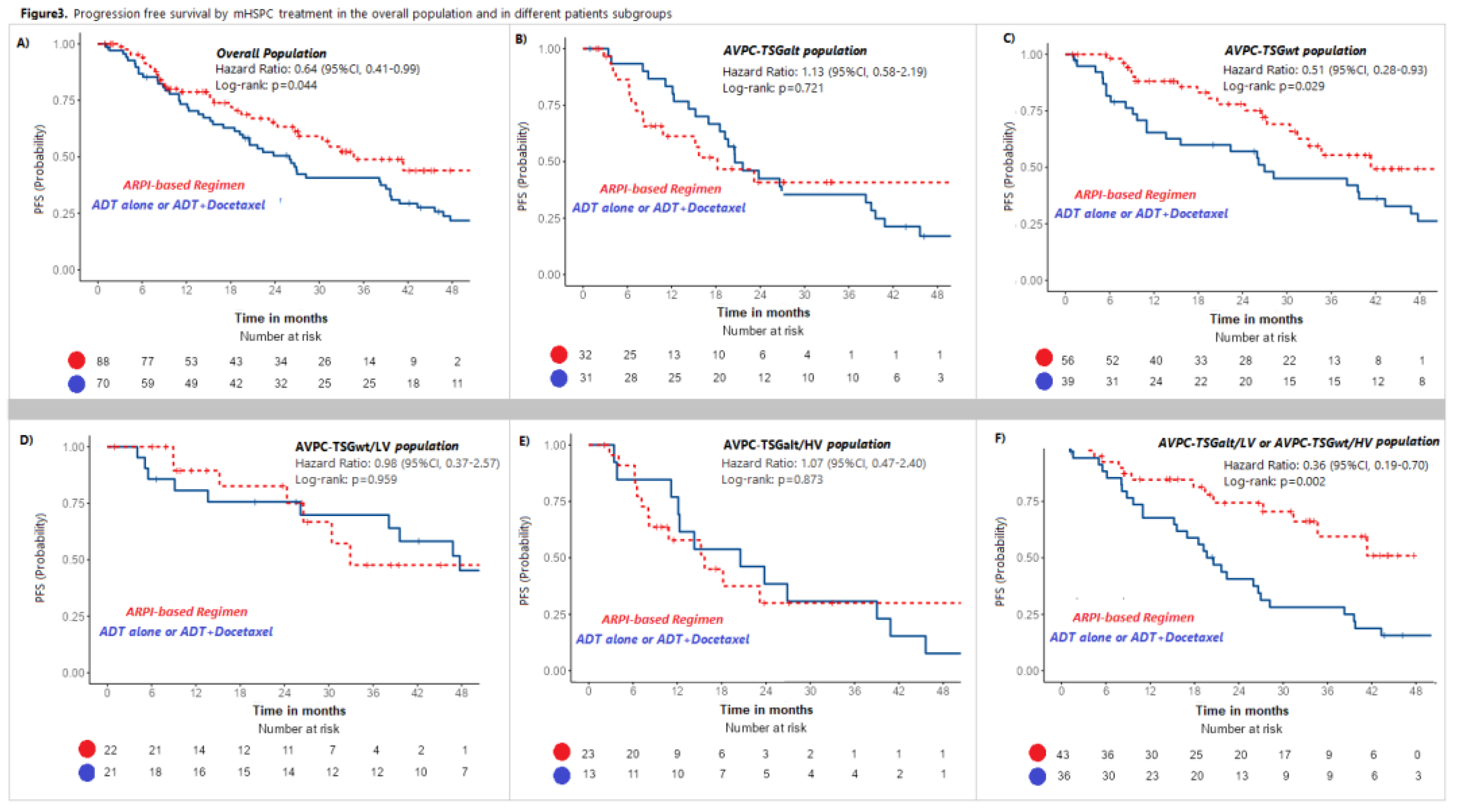

Univariate Cox analysis for PFS based on the use of ARPI-based regimen (ADT+ARPI or ADT+ARPI+docetaxel) in the overall population and in AVPC-TSGalt and AVPC-TSGwt subgroups are shown in

Table S15. Kaplan-Meier PFS curves are depicted in

Figure 3. Only the AVPC-TSGwt subgroup derived a PFS benefit from the addition of an ARPI to mHSPC treatment (HR:0.51, 95%CI:0.28-0.93, p=0.029). No PFS difference was observed for patients with AVPC-TSGalt mHSPC treated with ARPI-based regimes compared to ADT±docetaxel (HR:1.13, p=0.072)

Exploratory univariate Cox analysis for PFS based on the use of ARPI-based regimens in mHSPC patients, stratified by the newly established prognostic risk groups is detailed in

Table S16. Kaplan-Meier PFS curves are illustrated in

Figure 3. Only the intermediate risk subgroup (“AVPC-TSGalt/LV or AVPC-TSGwt/HV”) showed a statistically significant PFS benefit from ARPI-based regimens (HR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.19-0.70, p=0.002), particularly evident in the “AVPC-TSGwt/HV” subgroup (

Table S17).

Figure 3. Progression Free Survival by mHSPC Treatment in the Overall Population and in different patients subgroups.

3.5. Quality Assessment

The quality and completeness of the real-world data analysis was evaluated considering the ESMO-GROW guidance and self-reported Informative Score (

Table S18).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of AVPC-TSGalt status (assessed through commercially available next-generation sequencing platform) on refining the prognostic value of renowned clinical variables for the risk of progression and death in patients with mHSPC. It is also the largest study exploring the role of AVPC-TSGalt status in predicting PFS benefits from ARPI-based treatment regimens (ADT+ARPI or ADT+ARPI+docetaxel).

We found that the presence of at least one AVPC-TSG alteration predicted shorter PFS and was an independent prognostic factor for OS, with significant and clinically relevant effect sizes in both univariate and multivariate analyses. Patient groups (AVPC-TSGalt vs. AVPC-TSGwt) were well balanced in terms of clinical prognostic factors and treatments received. Despite the limited sample size, sensitivity analyses corroborated our findings, with AVPC-TSG status maintaining statistical significance in all multivariable Cox regression models. Additionally, no interaction was found between AVPC-TSG status and clinical variables, further supporting its independent prognostic role.

We developed a new prognostic stratification of mHSPC patients by integrating AVPC-TSG status with CHAARTED volume criteria, resulting in three distinct risk groups with significantly different PFS estimates. The “poor risk group”, characterized by high volume disease and AVPC-TSG alterations had the worst prognosis (median PFS:15.7 months). Conversely, nearly 50% of the “good risk group”, with low volume disease and no AVPC-TSG alterations, were free from progression or death at 4 years (median PFS:46.8 months), with over 70% surviving at 5 years. Notably, patients with either a genomic poor-risk feature or a clinical risk feature (AVPC-TSGwt/HV or AVPC-TSGalt/LV) showed similar PFS and OS and represented the “intermediate risk group”. Treatment type in mHSPC, particularly ARPI-based regimen, was evenly distributed across subgroups. In addition, the integration of clinical variables among them (disease volume, ISUP Grade Groups, and disease presentation) failed to effectively discriminate PFS outcomes when AVPC-TSG alterations were not taken into account. Our findings highlight the prognostic value of AVPC-TSG status in mHSPC, enhancing risk stratification and survival predictions.

While ARPI-based regimens (ADT+ARPI or ADT+ARPI+docetaxel) outperform ADT monotherapy or ADT+docetaxel in randomized clinical trials [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], treatment decisions in the mHSPC setting rely solely on clinical variables, with triplet therapy to be preferred in patients with high-volume de novo disease [

24,

25]. However, ARPI toxicities including financial burden [

26] warrant consideration. The impact of AVPC-TSG status on treatment outcomes remains unclear and is not factored into treatment decision-making in this setting.

As expected, in our study, ARPI-based regimens improved PFS overall (HR=0.64, p=0.044). However, only AVPC-TSGwt patients benefited significantly (HR=0.51, P=0.029), while AVPC-TSGalt tumors showed no advantage (HR=1.13, p=0.721).

The intermediate-risk subgroup showed the greatest benefit from ARPI-based strategies (HR=0.36, p=0.002), even exceeding the overall AVPC-TSGwt population. Detailed analysis, though limited by the small sample size, revealed that the PFS benefit was primarily driven by patients with high-volume/AVPC-TSGwt disease, reinforcing AVPC-TSG alterations as negative predictors of ARPI response. In contrast, neither the good-risk (HR=0.98, p=0.959) nor poor-risk (HR=1.07, p=0.873) subgroups showed significant benefit from ARPI-based treatment.

Preclinical studies and mCRPC data suggest that AVPC-TSG alterations may mediate resistance to hormonal treatments and docetaxel, with TP53, RB1, and PTEN loss driving prostate cancer progression and ARPI resistance.

Mutant p53 compromises docetaxel response [

27] and fails to downregulate AR, promoting resistance [

6,

7,

8]. RB1 loss enables castration-resistant tumor growth [

9,

10,

11] and resistance to abiraterone/enzalutamide [

28,

29,

30,

31], while TP53/PTEN co-loss is linked to abiraterone resistance [

32]. However, clinical evidence in mHSPC remains inconclusive.

Clinically, TP53 alterations predict poorer response [

12] and shorter PFS and OS [

13] to abiraterone and enzalutamide in mCRPC. Similarly, PTEN loss is associated with shortened response to abiraterone [

14]. STAMPEDE transcriptomic analysis, identified TP53/PTEN loss as negative prognostic factors in mHSPC patients treated with ARPI [

16], confirmed by a retrospective study linking AVPC-TSGalt status to inferior PFS with ADT plus abiraterone [

17]. A multicenter retrospective analysis further showed that the survival benefit from ADT plus docetaxel was limited to the TSGwt group, with no significant differences in the TSGlow counterpart [

33].

Our analysis, supported by the aforementioned pre-clinical and clinical research, suggests that patients in the “AVPC-TSGwt/LV” subgroup (61.4% of the low-volume population) might be ideal candidates for de-escalation strategies, as their long survival estimates are likely due to high sensitivity to prostate cancer treatments, a favorable intrinsic phenotype, or both. Additionally, specific genomic alterations in AVPC-TSGwt tumors (such as SPOP mutations) may further enhance their sensitivity to hormonal treatments [

34]. Patients in the intermediate-risk group (50% of the study population), may benefit from ARPI-based regimens and standard treatment intensification. Conversely, patients with both high-volume and AVPC-TSG altered mHSPC (40.9% of the high-volume population) have a very poor prognosis and should be considered for clinical trials exploring alternative treatments, as they may not benefit from current standard approaches.

Triplet therapy (ADT + ARPI + docetaxel) is mostly considered for high-volume mHSPC, but AVPC-TSG alterations may confer resistance to both docetaxel and ARPI. Thus, assessing its efficacy in relation to the AVPC-TSG mutational status will be crucial to avoid overtreatment, unnecessary toxicities, and increased mortality.

Notably, a study employing whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-transcriptome sequencing (WTS) of biopsies from ARPI-treated mCRPC patients found that TP53, PTEN, and RB1 abberations did not correlate with treatment response, suggesting that prior treatments may affect the molecular marker reliability [

35]. Conversely, our study using treatment-naïve biopsies, eliminates such confounders, ensuring a more unbiased evaluation of AVPC-TSG alterations .

Additionally, AVPC-TSG status varies depending on testing timing and site due to spatial and temporal heterogeneity [

36]. Hamid et al. reported TSG variants in 39% of localized prostate cancer cases, rising to 63% in mHSPC and 92% in mCRPC [

37]. In our cohort, considering PI3K/AKT pathway-associated genes, 39.9% had at least one altered AVPC-TSG, likely due to 74% of NGS analyses having been conducted on primary prostate specimens. This highlight the prognostic significance of AVPC-TSG alterations before treatment and metastasis.

Given the limited surgical options and tissue availability in these patients, NGS analysis on primary tumors offers a practical alternative for real-world clinical applications. Our study utilized commercially available platforms, proving that routine genomic analyses can provide valuable prognostic and predictive insights. Furthermore, our study included a real-world patient cohort treated at a tertiary referral center according to standard treatment and staging protocols, enhancing the applicability of our findings to routine oncology practices.

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

The main limitations of our study include its retrospective single-centre nature, with a limited sample size, and treatment heterogeneity, which prevented us from testing the effect of individual treatment strategies across subgroups. These are common limitations when assessing retrospectively data from real-world practice. To mitigate these issues, patients included were derived from a consecutive series, we conducted multivariable analysis considering all relevant clinical variables, and performed sensitivity analyses. Notably, our genomic analyses were performed on a single mHSPC sample per patient, overlooking potential intratumoral heterogeneity. Moreover, our NGS panel did not assess gene deletions, a frequent TSG alteration. Notably, these are typical limitations of clinical-grade NGS panels, which we employed in line with our goal to make our findings reproducible and cost-effective in most clinical settings. We finally underscore the need for larger datasets to validate and extend the insights gained from our study.

6. Conclusions

Our findings reveal for the first time that AVPC-TSG status provides additional prognostic and predictive information beyond traditional clinical variables in mHSPC. AVPC-TSG status evaluation can reshape mHSPC prognosis and inform treatment selection, identifying a subgroup of patients with exceptional survival outcomes—those with AVPC-TSGwt and low-volume disease—who may be potential candidates for de-escalation strategies. At the same time, patients with AVPC-TSGalt mHSPC should be considered for clinical trials exploring alternative treatments, as they may not benefit from current standard approaches. Accounting for AVPC-TSG mutational status will be important in future mHSPC trials for developing more personalized treatment strategies, including intensification and de-intensification of available modalities and testing innovative treatments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Pedrani, Salfi, Pereira Mestre, methodology, Pedrani, Salfi; formal analysis, Pedrani; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, Pedrani, Salfi, Agrippina Clerici; writing—original draft preparation, Pedrani, Salfi, Pereira Mestre, Merler; Pecoraro writing—review and editing, Pedrani, Salfi, Pereira Mestre, Merler, Zilli, Theurillat, Castelo-Branco, Turco, Vogl, Gillessen, Testi, Pecoraro, Tortola; visualization, Pedrani, Salfi.; supervision, Gillessen, Zilli, Theurillat; project administration, Tortola; funding acquisition, Pereira Mestre, Gillessen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from Fondazione Daccò (Fondo EOC-USI).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was in the scope of a retrospective data collection protocol approved by the local ethical committee (Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale – Bellinzona) and was in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Every patient either signed an informed consent for data collection or was deceased at the time of data analysis. When indicated written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Single patients data are unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Silke Gillessen received personal honoraria for participation in advisory boards for Sanofi, Orion, Roche, Amgen, MSD; other honoraria from RSI (Televisione Svizzera Italiana); invited speaker for ESMO, Swiss group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), Swiss Academy of Multidisciplinary oncology (SAMO), Orikata academy research group, China Anti-Cancer Association Genitourinary Oncology Committee (CACA-GU); Speaker’s bureau for Janssen Cilag; travel grant from ProteoMEdiX; institutional honoraria for advisory boards for Bayer, Janssen Cilag, Roche, AAA International including Indipendent Data Monitoring Committee and IDMC and Steering Committee member for Amgen, Menarini Silicon Biosystems, Astellas Pharma, Tolero Pharmaceutcials, MSD, Pfizer, Telixpharma, BMS and Orion; patent royalties and other intellectual property for a research method for biomarker WO2009138392. Ursula Vogl received grant from Fond’Action; received institutional personal honoraria from Pfizer, Astellas, Janssen, Merck, MSD, BMS, Ipsen, Healthbook, Novartis AAA, Bayer, Grasso consulting, Vaccentis; received private personal honoraria from Healthbook, SAMO, Inselspital Bern, Kantonsspital Chur, Kantonsspital Baden, Ipsen; and received travel grant from Astra Zeneca and Janssen. Fabio Turco received travel grant from Bayer. All other authors declare the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wang L, Lu B, He M, Wang Y, Wang Z, Du L. Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality: Global Status and Temporal Trends in 89 Countries From 2000 to 2019. Front Public Heal. 2022, 10. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.811044/full.

- Hamid AA, Sayegh N, Tombal B, Hussain M, Sweeney CJ, Graff JN, et al. Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Toward an Era of Adaptive and Personalized Treatment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B. 2023, 43. Available online: https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_390166.

- Vale CL, Fisher DJ, Godolphin PJ, Rydzewska LH, Boher J-M, Burdett S, et al. Which patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer benefit from docetaxel: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 783–97. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204523002309.

- Corn PG, Heath EI, Zurita A, Ramesh N, Xiao L, Sei E, et al. Cabazitaxel plus carboplatin for the treatment of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancers: a randomised, open-label, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1432–43. Available online: https://linkinghubelseviercom/retrieve/pii/S1470204519304085.

- Mu P, Zhang Z, Benelli M, Karthaus WR, Hoover E, Chen C-C, et al. SOX2 promotes lineage plasticity and antiandrogen resistance in TP53 - and RB1 -deficient prostate cancer. Science (80- ). 2017, 355, 84–8. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aah4307.

- Cronauer M V, Schulz WA, Burchardt T, Ackermann R, Burchardt M. Inhibition of p53 function diminishes androgen receptor-mediated signaling in prostate cancer cell lines. Oncogene 2004, 23, 3541–9. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15077179.

- Shenk JL, Fisher CJ, Chen S-Y, Zhou X-F, Tillman K, Shemshedini L. p53 Represses Androgen-induced Transactivation of Prostate-specific Antigen by Disrupting hAR Amino- to Carboxyl-terminal Interaction. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276, 38472–9. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0021925820740962.

- Gurova K V, Roklin OW, Krivokrysenko VI, Chumakov PM, Cohen MB, Feinstein E, et al. Expression of prostate specific antigen (PSA) is negatively regulated by p53. Oncogene 2002, 21, 153–7. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/1205001.

- Sharma A, Comstock CES, Knudsen ES, Cao KH, Hess-Wilson JK, Morey LM, et al. Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor status is a critical determinant of therapeutic response in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 6192–203. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17616676.

- Sharma A, Yeow W-S, Ertel A, Coleman I, Clegg N, Thangavel C, et al. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor controls androgen signaling and human prostate cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2010, 120, 4478–92. Available online: http://www.jci.org/articles/view/44239.

- Knudsen KE, Arden KC, Cavenee WK. Multiple G1 regulatory elements control the androgen-dependent proliferation of prostatic carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273, 20213–22. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9685369.

- Maughan BL, Guedes LB, Boucher K, Rajoria G, Liu Z, Klimek S, et al. p53 status in the primary tumor predicts efficacy of subsequent abiraterone and enzalutamide in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018, 21, 260–8. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41391-017-0027-4.

- De Laere B, Oeyen S, Mayrhofer M, Whitington T, van Dam P-J, Van Oyen P, et al. TP53 Outperforms Other Androgen Receptor Biomarkers to Predict Abiraterone or Enzalutamide Outcome in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1766–73. Available online: https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/25/6/1766/82359/TP53-Outperforms-Other-Androgen-Receptor.

- Ferraldeschi R, Nava Rodrigues D, Riisnaes R, Miranda S, Figueiredo I, Rescigno P, et al. PTEN protein loss and clinical outcome from castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with abiraterone acetate. Eur Urol. 2015, 67, 795–802. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25454616.

- Pedrani M, Barizzi J, Salfi G, Nepote A, Testi I, Merler S, et al. The Emerging Predictive and Prognostic Role of Aggressive-Variant-Associated Tumor Suppressor Genes Across Prostate Cancer Stages. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39796175.

- Attard G, Parry M, Grist E, Mendes L, Dutey-Magni P, Sachdeva A, et al. Clinical testing of transcriptome-wide expression profiles in high-risk localized and metastatic prostate cancer starting androgen deprivation therapy: an ancillary study of the STAMPEDE abiraterone Phase 3 trial. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2488586/v1.

- Velez MG, Kosiorek HE, Egan JB, McNatty AL, Riaz IB, Hwang SR, et al. Differential impact of tumor suppressor gene (TP53, PTEN, RB1) alterations and treatment outcomes in metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022, 25, 479–83. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41391-021-00430-4.

- Castelo-Branco L, Pellat A, Martins-Branco D, Valachis A, Derksen JWG, Suijkerbuijk KPM, et al. ESMO Guidance for Reporting Oncology real-World evidence (GROW). Ann Oncol. 2023, 34, 1097–112. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753423040188.

- Sonpavde G, Pond GR, Armstrong AJ, Galsky MD, Leopold L, Wood BA, et al. Radiographic progression by Prostate Cancer Working Group ( PCWG )-2 criteria as an intermediate endpoint for drug development in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2014, 114. Available online: https://bjui-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bju.12589.

- Tilki D, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Brunckhorst O, Darraugh J, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II—2024 Update: Treatment of Relapsing and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2024. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0302283824023066.

- Cox, DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 1972, 34, 187–202. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jrsssb/article/34/2/187/7027194. [CrossRef]

- Holm, Sture. “A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure.” Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 1979, 6, 65–70.

- Fizazi K, Gillessen S. Updated treatment recommendations for prostate cancer from the ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline considering treatment intensification and use of novel systemic agents. Ann Oncol. 2023, 34, 557–63. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753423001114.

- EAU Guidelines. Edn. Presented at the EAU Annual Congress Paris 2024. ISBN 978-94-92671-23-3.

- Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra N, An Y, Bitting R, Chapin B, et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 3.2024. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 140–50. Available online: https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/22/3/article-p140.xml.

- Gill JK, Sperandio RC, Nguyen TH, Emmenegger U. Toxicity-benefit analysis of advanced prostate cancer trials using weighted toxicity scoring. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42 (4_suppl), 110–110. Available online: https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2024.42.4_suppl.110. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Zhu Y, Lou W, Nadiminty N, Chen X, Zhou Q, et al. Functional p53 determines docetaxel sensitivity in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2013, 73, 418–27. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pros.22583.

- Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu Y-M, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera J-M, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015, 161, 1215–28. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26000489.

- Beltran H, Prandi D, Mosquera JM, Benelli M, Puca L, Cyrta J, et al. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2016, 22, 298–305. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nm.4045.

- Tan H-L, Sood A, Rahimi HA, Wang W, Gupta N, Hicks J, et al. Rb Loss Is Characteristic of Prostatic Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 890–903. Available online: https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/20/4/890/78787/Rb-Loss-Is-Characteristic-of-Prostatic-Small-Cell.

- Aparicio AM, Shen L, Tapia ELN, Lu J-F, Chen H-C, Zhang J, et al. Combined Tumor Suppressor Defects Characterize Clinically Defined Aggressive Variant Prostate Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1520–30. Available online: https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/22/6/1520/120857/Combined-Tumor-Suppressor-Defects-Characterize.

- Zou M, Toivanen R, Mitrofanova A, Floch N, Hayati S, Sun Y, et al. Transdifferentiation as a Mechanism of Treatment Resistance in a Mouse Model of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 736–49. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28411207.

- Jiménez N, Garcia de Herreros M, Reig Ò, Marín-Aguilera M, Aversa C, Ferrer-Mileo L, et al. Development and Independent Validation of a Prognostic Gene Expression Signature Based on RB1, PTEN, and TP53 in Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer Patients. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2588931124000257.

- Pedrani M, Salfi G, Merler S, Testi I, Cani M, Turco F, et al. Prognostic and Predictive Role of SPOP Mutations in Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2588931124001032.

- de Jong AC, Danyi A, van Riet J, de Wit R, Sjöström M, Feng F, et al. Predicting response to enzalutamide and abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer using whole-omics machine learning. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 1968. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-37647-x.

- Nava Rodrigues D, Casiraghi N, Romanel A, Crespo M, Miranda S, Rescigno P, et al. RB1 Heterogeneity in Advanced Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 687–97. Available online: https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/25/2/687/127036/RB1-Heterogeneity-in-Advanced-Metastatic.

- Hamid AA, Gray KP, Shaw G, MacConaill LE, Evan C, Bernard B, et al. Compound Genomic Alterations of TP53, PTEN, and RB1 Tumor Suppressors in Localized and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2019, 76, 89–97. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0302283818309497.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).