Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

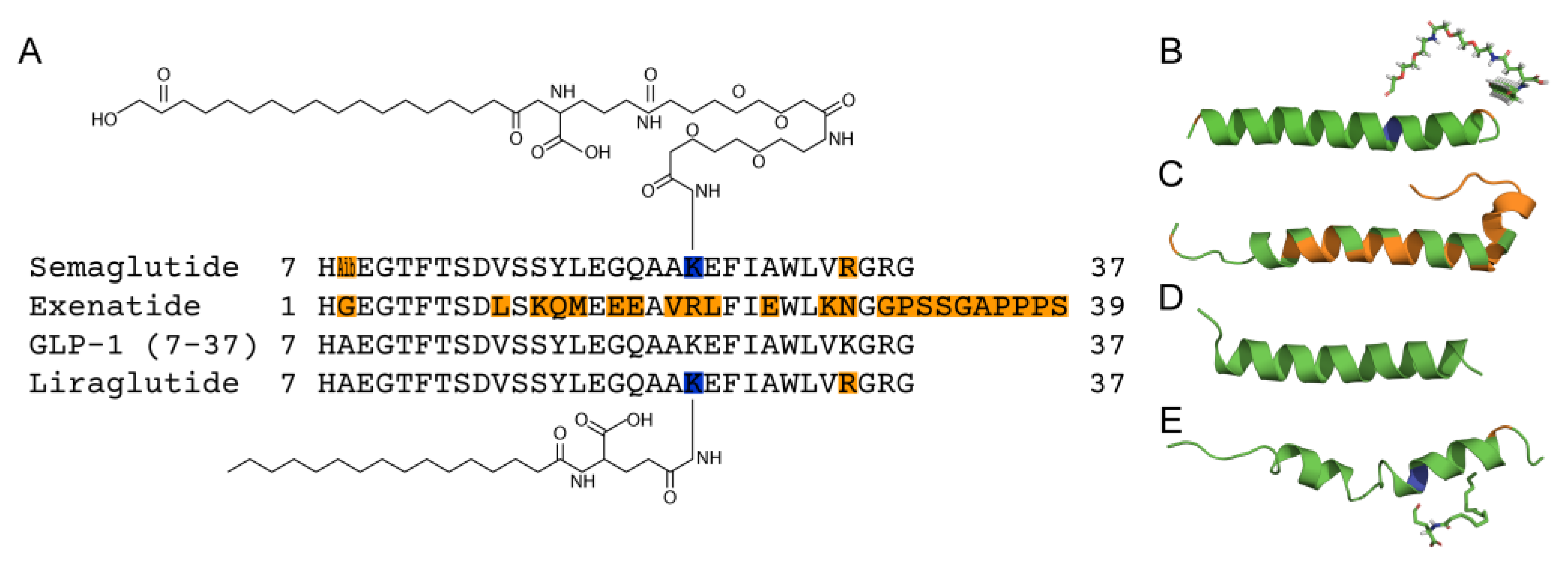

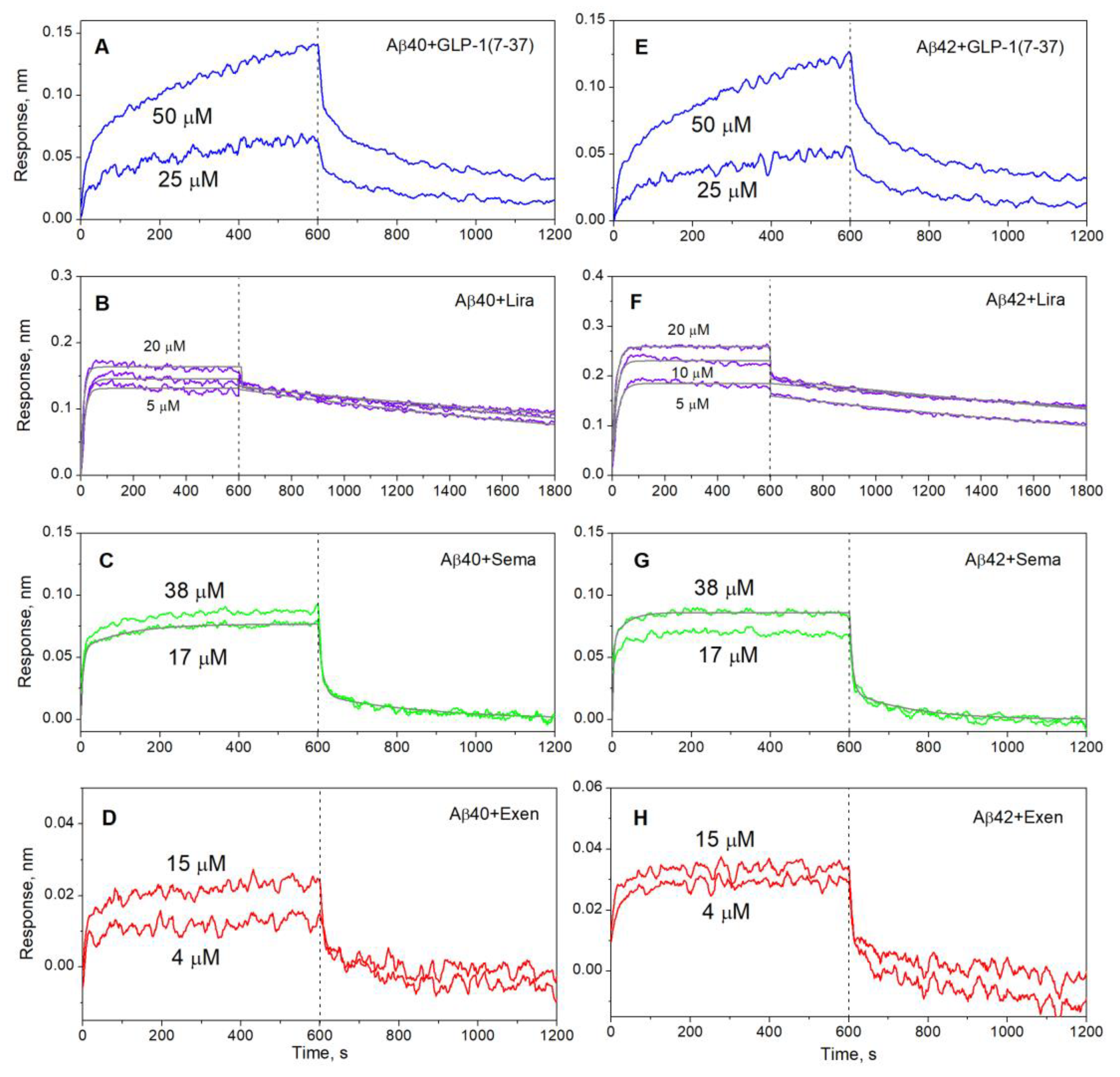

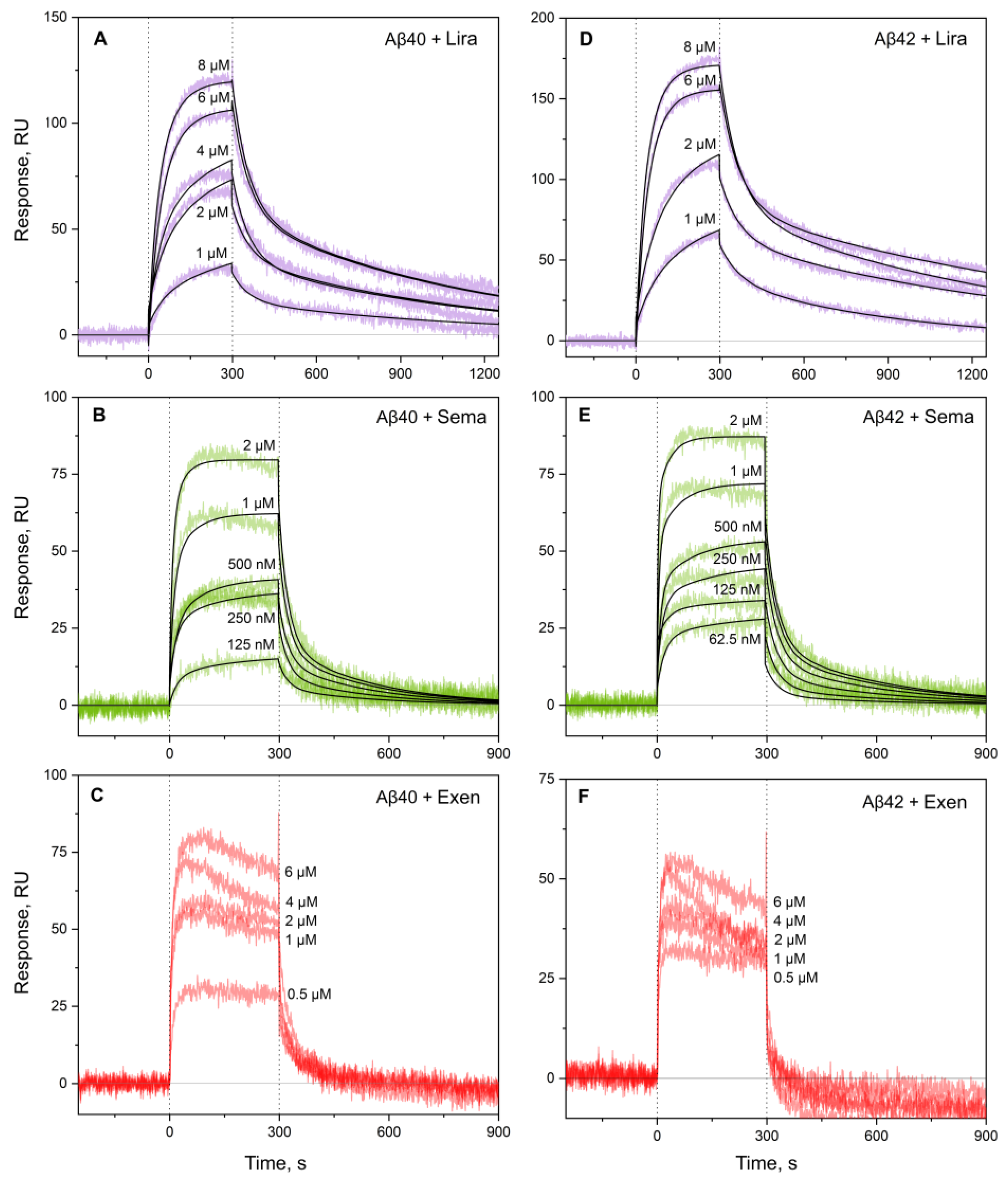

2.1. Interaction of GLP-1RAs with Monomeric Aβ

2.2. Concentration-Dependent Changes in Quaternary Structure of the GLP-1RAs

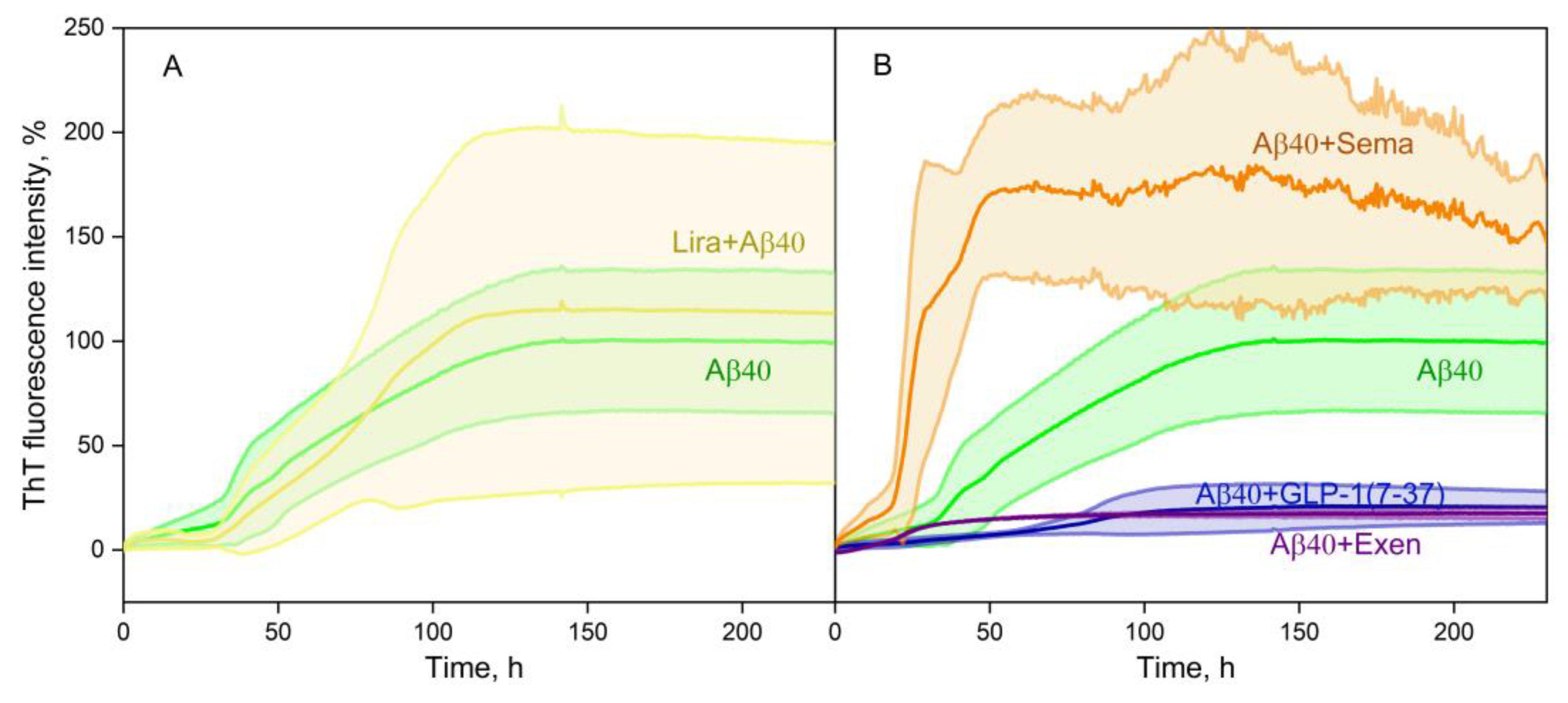

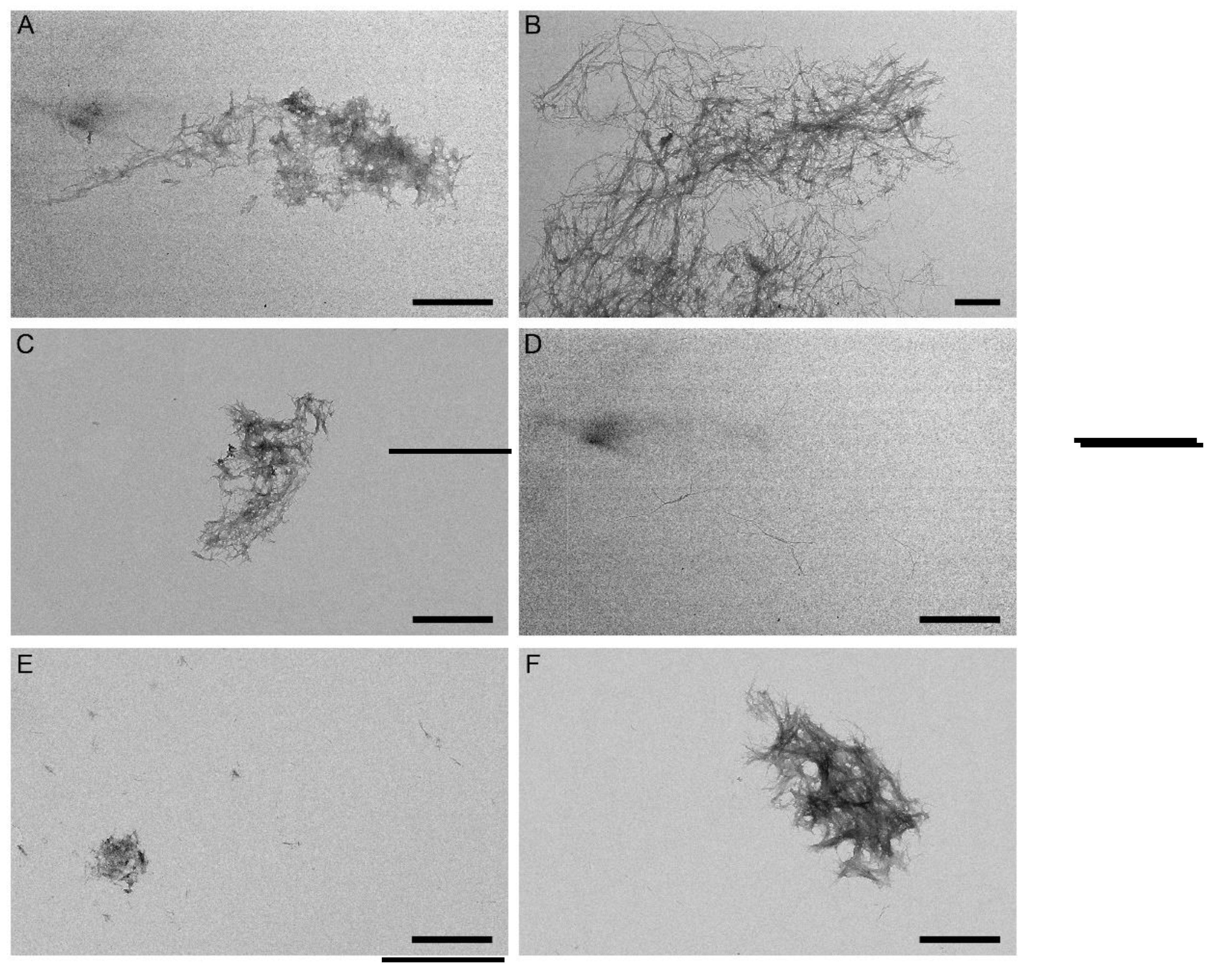

2.3. Effect of the GLP-1RAs on Aβ fibrillation

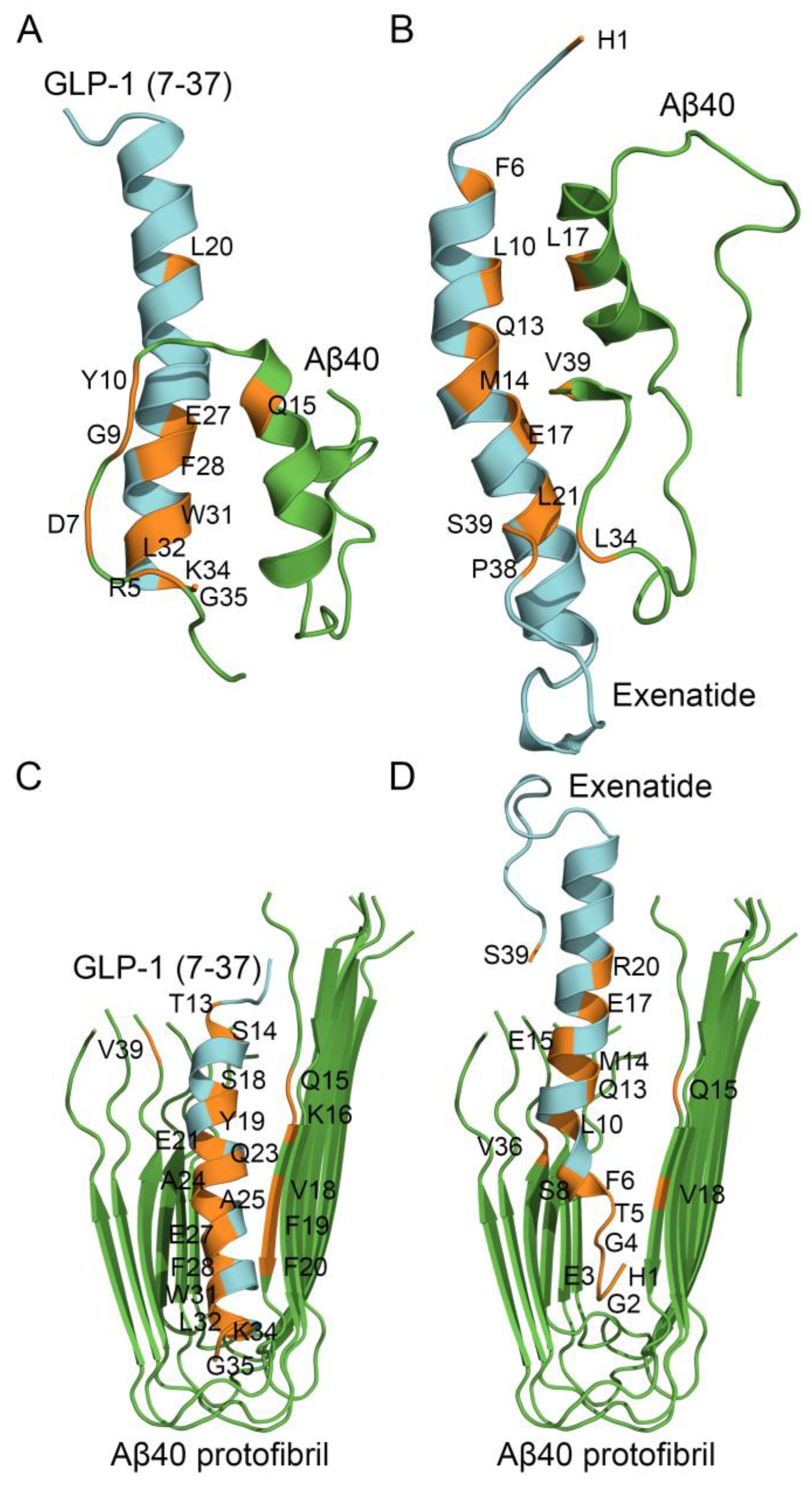

2.4. Structural Modeling of the Complexes Between Aβ40 or Its Protofibril and GLP-1(7-37)/Exen

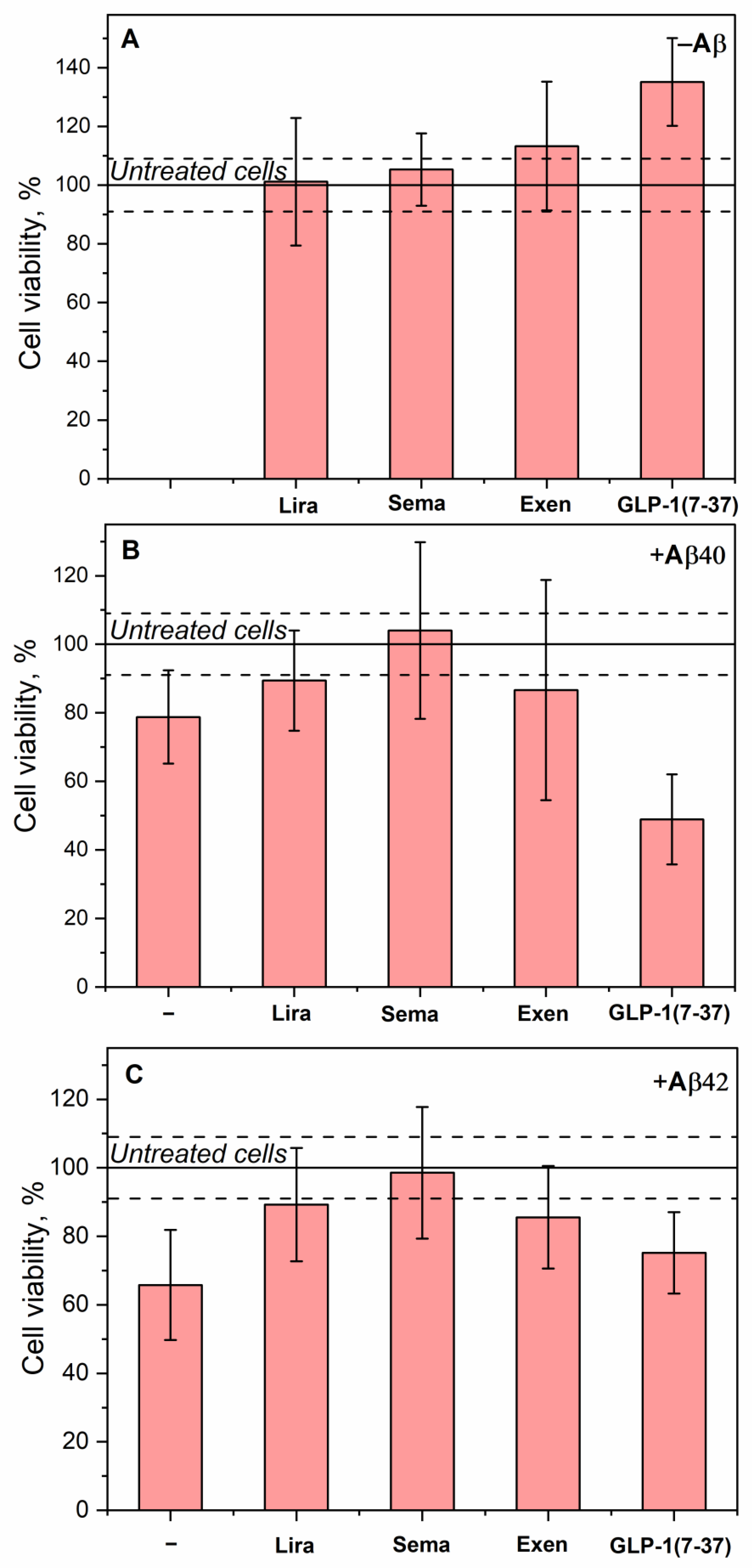

2.5. Effect of the GLP-1RAs on Aβ Cytotoxicity to Human Neuroblastoma Cells

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. BLI Measurements

| A + L |

ka ↔ |

AL | (1) |

|

kd KD |

| A + L1 |

ka1 ↔ |

AL1 | A + L2 |

ka2 ↔ |

AL2 | (2) | |

|

kd1 KD1 |

kd2 KD2 |

3.3. SPR Measurements

3.4. Dynamic Light Scattering Measurements

3.5. Structural Modeling

3.6. ThT Fluorescence Assay

3.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy

3.8. Cell Viability Assay

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-ME | 2-mercaptoethanol |

| Aβ | amyloid-β peptide |

| Aβ40/Aβ42 | amyloid-β peptide, residues 1-40/42 |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| DM2 | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DPP-4 | dipeptidyl peptidase-4 |

| EDAC/sulfo-NHS | 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide hydrochloride/N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide |

| EDTA EM |

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid Electron microscope |

| Exen | Exendin-4/Exenatide |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| GLP-1(7-36), GLP-1(7-37) | N-terminally truncated forms of glucagon-like peptide 1, residues 7-36 or 7-37 |

| GLP-1R | glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor |

| GLP-1RA | glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist |

| HSA | human serum albumin |

| Lira | Liraglutide |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| MWm | molecular mass calculated from the amino acid sequence |

| MWRh | molecular mass calculated from the hydrodynamic radius |

| NMR | nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PA | palmitic acid |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| Sema | Semaglutide |

| SDS | sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| TFA | trifluoroacetic acid |

| ThT | Thioflavin T |

| Tris | tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane |

| TWEEN | polyethylene glycol sorbitan monolaurate |

References

- Gustavsson, A.; Norton, N.; Fast, T.; Frölich, L.; Georges, J.; Holzapfel, D.; Kirabali, T.; Krolak-Salmon, P.; Rossini, P.M.; Ferretti, M.T.; et al. Global estimates on the number of persons across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2023, 19, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E. FDA Green-Lights Second Alzheimer Drug, Donanemab. JAMA 2024, 332, 524–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [CrossRef]

- Ameen, T.B.; Kashif, S.N.; Abbas, S.M.I.; Babar, K.; Ali, S.M.S.; Raheem, A. Unraveling Alzheimer’s: the promise of aducanumab, lecanemab, and donanemab. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery 2024, 60, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Sabermarouf, B.; Majdi, A.; Talebi, M.; Farhoudi, M.; Mahmoudi, J. Amyloid-beta: a crucial factor in Alzheimer’s disease. Med Princ Pract 2015, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.J.; Wong, P.C. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Neurosci 2011, 34, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenner, G.G.; Wong, C.W. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1984, 120, 885-890, doi:S0006-291X(84)80190-4 [pii]10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [CrossRef]

- 8. Chen, G.F.; Xu, T.H.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Y.R.; Jiang, Y.; Melcher, K.; Xu, H.E. Amyloid beta: structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2017, 38, 1205-1235, doi:aps201728 [pii]10.1038/aps.2017.28. [CrossRef]

- Vander Zanden, C.M.; Wampler, L.; Bowers, I.; Watkins, E.B.; Majewski, J.; Chi, E.Y. Fibrillar and Nonfibrillar Amyloid Beta Structures Drive Two Modes of Membrane-Mediated Toxicity. Langmuir 2019, 35, 16024–16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, Z.; Wilson, R.S.; Bienias, J.L.; Evans, D.A.; Bennett, D.A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer disease and decline in cognitive function. Archives of neurology 2004, 61, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, A.; Stolk, R.P.; Hofman, A.; van Harskamp, F.; Grobbee, D.E.; Breteler, M.M. Association of diabetes mellitus and dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Diabetologia 1996, 39, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.J.; Han, W.N.; Chai, S.F.; Li, Y.; Fu, C.J.; Wang, C.F.; Cai, H.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Wang, X.; Hölscher, C.; et al. Semaglutide promotes the transition of microglia from M1 to M2 type to reduce brain inflammation in APP/PS1/tau mice. Neuroscience 2024, 563, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overview: Type 2 diabetes. In InformedHealth.org [Internet]. ; Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG): Cologne, Germany, 2006.

- Michailidis, M.; Moraitou, D.; Tata, D.A.; Kalinderi, K.; Papamitsou, T.; Papaliagkas, V. Alzheimer’s Disease as Type 3 Diabetes: Common Pathophysiological Mechanisms between Alzheimer’s Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, doi:ijms23052687 [pii]ijms-23-02687 [pii]10.3390/ijms23052687. [CrossRef]

- Kandimalla, R.; Thirumala, V.; Reddy, P.H. Is Alzheimer’s disease a Type 3 Diabetes? A critical appraisal. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1863, 1078-1089, doi:S0925-4439(16)30215-0 [pii]10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.08.018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michailidis M; Tata DA; Moraitou D; Kavvadas D; Karachrysafi S; Papamitsou T; Vareltzis P; V., P. Antidiabetic Drugs in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23.

- Mudaliar, S.; Henry, R.R. The incretin hormones: from scientific discovery to practical therapeutics. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 1865–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobble, M. Differentiating among incretin-based therapies in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 2012, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J. The role of incretin-based therapies in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: perspectives on the past, present and future; 2019; Volume 22.

- Lim, G.E.; Brubaker, P.L. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Secretion by the L-Cell: The View From Within. Diabetes 2006, 55, S70–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Application of Glucagon-like Peptide-1. Cell Metab 2018, 27, 740-756, doi:S1550-4131(18)30179-7 [pii]10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001. [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.D.; Finan, B.; Bloom, S.R.; D’Alessio, D.; Drucker, D.J.; Flatt, P.R.; Fritsche, A.; Gribble, F.; Grill, H.J.; Habener, J.F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Molecular metabolism 2019, 30, 72–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, M.K.; Richards, J.E.; Cook, D.R.; Brierley, D.I.; Williams, D.L.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M.; Trapp, S. Preproglucagon Neurons in the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract Are the Main Source of Brain GLP-1, Mediate Stress-Induced Hypophagia, and Limit Unusually Large Intakes of Food. Diabetes 2019, 68, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastin, A.J.; Akerstrom, V.; Pan, W. Interactions of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) with the blood-brain barrier. J Mol Neurosci 2002, 18, 7-14, doi:JMN:18:1-2:07 [pii]10.1385/JMN:18:1-2:07. [CrossRef]

- Muscogiuri, G.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Gastaldelli, A.; Holst, J.J. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 and the Central/Peripheral Nervous System: Crosstalk in Diabetes. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2017, 28, 88-103, doi:S1043-2760(16)30126-6 [pii]10.1016/j.tem.2016.10.001. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monney, M.; Jornayvaz, F.R.; Gariani, K. GLP-1 receptor agonists effect on cognitive function in patients with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2023, 49, 101470, doi:S1262-3636(23)00052-6 [pii]10.1016/j.diabet.2023.101470. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holscher, C. Novel dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists show neuroprotective effects in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease models. Neuropharmacology 2018, 136, 251-259, doi:S0028-3908(18)30040-6 [pii]10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, T.; Faivre, E.; Holscher, C. Impairment of synaptic plasticity and memory formation in GLP-1 receptor KO mice: Interaction between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res 2009, 205, 265-271, doi:S0166-4328(09)00397-0 [pii]10.1016/j.bbr.2009.06.035. [CrossRef]

- During, M.J.; Cao, L.; Zuzga, D.S.; Francis, J.S.; Fitzsimons, H.L.; Jiao, X.; Bland, R.J.; Klugmann, M.; Banks, W.A.; Drucker, D.J.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor is involved in learning and neuroprotection. Nat Med 2003, 9, 1173-1179, doi:nm919 [pii]10.1038/nm919. [CrossRef]

- Perry, T.; Lahiri, D.K.; Sambamurti, K.; Chen, D.; Mattson, M.P.; Egan, J.M.; Greig, N.H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 decreases endogenous amyloid-beta peptide (Abeta) levels and protects hippocampal neurons from death induced by Abeta and iron. Journal of neuroscience research 2003, 72, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Sun, Z.; Huang, J.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Mei, B. Mutated recombinant human glucagon-like peptide-1 protects SH-SY5Y cells from apoptosis induced by amyloid-beta peptide (1-42). Neurosci Lett 2008, 444, 217-221, doi:S0304-3940(08)01164-6 [pii]10.1016/j.neulet.2008.08.047. [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.R.; Drucker, D.J. Cardiovascular biology of the incretin system. Endocr Rev 2012, 33, 187-215, doi:er.2011-1052 [pii]10.1210/er.2011-1052. [CrossRef]

- Hui, H.; Farilla, L.; Merkel, P.; Perfetti, R. The short half-life of glucagon-like peptide-1 in plasma does not reflect its long-lasting beneficial effects. European journal of endocrinology 2002, 146, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamboeck, A.; Holst, J.J.; Carr, R.D.; Deacon, C.F. Neutral Endopeptidase 24.11 and Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV are Both Involved in Regulating the Metabolic Stability of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 in vivo. In Dipeptidyl Aminopeptidases in Health and Disease, Back, N., Cohen, I.R., Kritchevsky, D., Lajtha, A., Paoletti, R., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2003; pp. 303-312.

- Collins L, C.R. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. In StatPearls [Internet]; 2025.

- Gupta, V. Glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues: An overview. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2013, 17, 413-421, doi:IJEM-17-413 [pii]10.4103/2230-8210.111625. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duffy, K.B.; Ottinger, M.A.; Ray, B.; Bailey, J.A.; Holloway, H.W.; Tweedie, D.; Perry, T.; Mattson, M.P.; Kapogiannis, D.; et al. GLP-1 receptor stimulation reduces amyloid-beta peptide accumulation and cytotoxicity in cellular and animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2010, 19, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Jiang, R.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y. Exendin-4 antagonizes Aβ1-42-induced attenuation of spatial learning and memory ability. Exp Ther Med 2016, 12, 2885–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabadu, D.; Verma, J. Exendin-4 attenuates brain mitochondrial toxicity through PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway in amyloid beta (1–42)-induced cognitive deficit rats. Neurochemistry International 2019, 128, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, Z.; Chen, S.; Yao, W.; Gao, X. GLP-1 receptor agonists downregulate aberrant GnT-III expression in Alzheimer’s disease models through the Akt/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling. Neuropharmacology 2018, 131, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Exendin-4 alleviates β-Amyloid peptide toxicity via DAF-16 in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviles-Olmos, I.; Dickson, J.; Kefalopoulou, Z.; Djamshidian, A.; Kahan, J.; Ell, P.; Whitton, P.; Wyse, R.; Isaacs, T.; Lees, A.; et al. Motor and cognitive advantages persist 12 months after exenatide exposure in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2014, 4, 337-344, doi:H26015442R458926 [pii]10.3233/JPD-140364. [CrossRef]

- Mullins, R.J.; Mustapic, M.; Chia, C.W.; Carlson, O.; Gulyani, S.; Tran, J.; Li, Y.; Mattson, M.P.; Resnick, S.; Egan, J.M.; et al. A Pilot Study of Exenatide Actions in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2019, 16, 741-752, doi:CAR-EPUB-100792 [pii]10.2174/1567205016666190913155950. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Xin, X.; Ma, J.; Tan, C.; Osna, N.; Mahato, R.I. Therapeutic targets, novel drugs, and delivery systems for diabetes associated NAFLD and liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 176, 113888, doi:S0169-409X(21)00280-5 [pii]10.1016/j.addr.2021.113888. [CrossRef]

- Meece, J. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Liraglutide, a Long-Acting, Potent Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Analog. Pharmacotherapy 2009, 29, 33S–42S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantrapirom, S.; Nimlamool, W.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.; Temviriyanukul, P.; Inthachat, W.; Govitrapong, P.; Potikanond, S. Liraglutide Suppresses Tau Hyperphosphorylation, Amyloid Beta Accumulation through Regulating Neuronal Insulin Signaling and BACE-1 Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, doi:ijms21051725 [pii]ijms-21-01725 [pii]10.3390/ijms21051725. [CrossRef]

- McClean, P.L.; Parthsarathy, V.; Faivre, E.; Hölscher, C. The diabetes drug liraglutide prevents degenerative processes in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2011, 31, 6587–6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, P.L.; Hölscher, C. Liraglutide can reverse memory impairment, synaptic loss and reduce plaque load in aged APP/PS1 mice, a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2014, 76 Pt A, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, P.L.; Jalewa, J.; Hölscher, C. Prophylactic liraglutide treatment prevents amyloid plaque deposition, chronic inflammation and memory impairment in APP/PS1 mice. Behav Brain Res 2015, 293, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gejl, M.; Gjedde, A.; Egefjord, L.; Moller, A.; Hansen, S.B.; Vang, K.; Rodell, A.; Braendgaard, H.; Gottrup, H.; Schacht, A.; et al. In Alzheimer’s Disease, 6-Month Treatment with GLP-1 Analog Prevents Decline of Brain Glucose Metabolism: Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Front Aging Neurosci 2016, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.T.; Wroolie, T.E.; Tong, G.; Foland-Ross, L.C.; Frangou, S.; Singh, M.; McIntyre, R.S.; Roat-Shumway, S.; Myoraku, A.; Reiss, A.L.; et al. Neural correlates of liraglutide effects in persons at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res 2019, 356, 271-278, doi:S0166-4328(18)30643-0 [pii]10.1016/j.bbr.2018.08.006. [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Bloch, P.; Schaffer, L.; Pettersson, I.; Spetzler, J.; Kofoed, J.; Madsen, K.; Knudsen, L.B.; McGuire, J.; Steensgaard, D.B.; et al. Discovery of the Once-Weekly Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Analogue Semaglutide. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 7370–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.F.; Zhang, D.; Hu, W.M.; Liu, D.X.; Li, L. Semaglutide-mediated protection against Abeta correlated with enhancement of autophagy and inhibition of apotosis. J Clin Neurosci 2020, 81, 234-239, doi:S0967-5868(20)31533-2 [pii]10.1016/j.jocn.2020.09.054. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Feng, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Wang, R.; Ji, C.; Li, G.; Holscher, C. The diabetes drug semaglutide reduces infarct size, inflammation, and apoptosis, and normalizes neurogenesis in a rat model of stroke. Neuropharmacology 2019, 158, 107748, doi:S0028-3908(19)30307-7 [pii]10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107748. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, C.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, B.; Tong, A.; Zhong, Q.; Zhong, Z. Semaglutide ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease and restores oxytocin in APP/PS1 mice and human brain organoid models. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2024, 180, 117540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Research Study Investigating Semaglutide in People With Early Alzheimer’s Disease (EVOKE Plus). 2024.

- Cummings, J.L.; Atri, A.; Feldman, H.H.; Hansson, O.; Sano, M.; Knop, F.K.; Johannsen, P.; León, T.; Scheltens, P. evoke and evoke+: design of two large-scale, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies evaluating efficacy, safety, and tolerability of semaglutide in early-stage symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s research & therapy 2025, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryusheva, E.I.; Shevelyova, M.P.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Nemashkalova, E.L.; Vologzhannikova, A.A.; Machulin, A.V.; Nazipova, A.A.; Permyakova, M.E.; Permyakov, S.E.; Litus, E.A. In Search for Low-Molecular-Weight Ligands of Human Serum Albumin That Affect Its Affinity for Monomeric Amyloid beta Peptide. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, doi:ijms25094975 [pii]ijms-25-04975 [pii]10.3390/ijms25094975. [CrossRef]

- Kamynina, A.V.; Esteras, N.; Koroev, D.O.; Bobkova, N.V.; Balasanyants, S.M.; Simonyan, R.A.; Avetisyan, A.V.; Abramov, A.Y.; Volpina, O.M. Synthetic Fragments of Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products Bind Beta-Amyloid 1–40 and Protect Primary Brain Cells From Beta-Amyloid Toxicity. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, D.; Liu, S.; Shi, H.; Zhang, Y. The Imaging of Insulinomas Using a Radionuclide-Labelled Molecule of the GLP-1 Analogue Liraglutide: A New Application of Liraglutide. PloS one 2014, 9, e96833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, L.V.; Flint, A.; Olsen, A.K.; Ingwersen, S.H. Liraglutide in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2016, 55, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.D.; Yang, Y.Y. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Semaglutide: A Systematic Review. Drug design, development and therapy 2024, 18, 2555–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.D.; Pirttila, T.; Mehta, S.P.; Sersen, E.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Wisniewski, H.M. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta proteins 1-40 and 1-42 in Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology 2000, 57, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapadka, K.L.; Becher, F.J.; Uddin, S.; Varley, P.G.; Bishop, S.; Gomes Dos Santos, A.L.; Jackson, S.E. A pH-Induced Switch in Human Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Aggregation Kinetics. J Am Chem Soc 2016, 138, 16259–16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada Brichtova, E.; Krupova, M.; Bour, P.; Lindo, V.; Gomes Dos Santos, A.; Jackson, S.E. Glucagon-like peptide 1 aggregates into low-molecular-weight oligomers off-pathway to fibrillation. Biophys J 2023, 122, 2475-2488, doi:S0006-3495(23)00298-9 [pii]10.1016/j.bpj.2023.04.027. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, K. Direct Assessment of Oligomerization of Chemically Modified Peptides and Proteins in Formulations using DLS and DOSY-NMR. Pharm Res 2023, 40, 1329-1339, doi:10.1007/s11095-022-03468-8 [pii]10.1007/s11095-022-03468-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venanzi, M.; Savioli, M.; Cimino, R.; Gatto, E.; Palleschi, A.; Ripani, G.; Cicero, D.; Placidi, E.; Orvieto, F.; Bianchi, E. A spectroscopic and molecular dynamics study on the aggregation process of a long-acting lipidated therapeutic peptide: the case of semaglutide. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 10122–10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lomakin, A.; Kanai, S.; Alex, R.; Benedek, G.B. Transformation of oligomers of lipidated peptide induced by change in pH. Mol Pharm 2015, 12, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, M.; Gast, K.; Evers, A.; Kurz, M.; Pfeiffer-Marek, S.; Schuler, A.; Seckler, R.; Thalhammer, A. A Conserved Hydrophobic Moiety and Helix-Helix Interactions Drive the Self-Assembly of the Incretin Analog Exendin-4. Biomolecules 2021, 11, doi:biom11091305 [pii]biomolecules-11-01305 [pii]10.3390/biom11091305. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calanna, S.; Christensen, M.; Holst, J.; Laferrère, B.; Gluud, L.; Vilsbøll, T.; Knop, F. Secretion of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies. Diabetologia 2013, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balks, H.J.; Holst, J.J.; von zur Mühlen, A.; Brabant, G. Rapid Oscillations in Plasma Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) in Humans: Cholinergic Control of GLP-1 Secretion via Muscarinic Receptors1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 1997, 82, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineman, M.; Flanagan, S.; Taylor, K.; Aisporna, M.; Shen, L.Z.; Mace, K.F.; Walsh, B.; Diamant, M.; Cirincione, B.; Kothare, P.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Exenatide Extended-Release After Single and Multiple Dosing. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2011, 50, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastin, A.J.; Akerstrom, V. Entry of exendin-4 into brain is rapid but may be limited at high doses. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 2003, 27, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabery, S.; Salinas, C.G.; Paulsen, S.J.; Ahnfelt-Rønne, J.; Alanentalo, T.; Baquero, A.F.; Buckley, S.T.; Farkas, E.; Fekete, C.; Frederiksen, K.S.; et al. Semaglutide lowers body weight in rodents via distributed neural pathways. JCI insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovshin, J.A.; Drucker, D.J. Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2009, 5, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejgaard, T.; Frandsen, C.; Kielgast, U.; Størling, J.; Overgaard, A.; Svane, M.; Olsen, M.H.; Thorsteinsson, B.; Andersen, H.; Krarup, T.; et al. Liraglutide enhances insulin secretion and prolongs the remission period in adults with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes (the NewLira study): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, I.T.; Porter, K.A.; Xia, B.; Kozakov, D.; Vajda, S. Performance and Its Limits in Rigid Body Protein-Protein Docking. Structure 2020, 28, 1071-1081 e1073, doi:S0969-2126(20)30209-4 [pii]10.1016/j.str.2020.06.006. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarero-Basulto, J.J.; Gasca-Martínez, Y.; Rivera-Cervantes, M.C.; Gasca-Martínez, D.; Carrillo-González, N.J.; Beas-Zárate, C.; Gudiño-Cabrera, G. Cytotoxic Effect of Amyloid-β1-42 Oligomers on Endoplasmic Reticulum and Golgi Apparatus Arrangement in SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells. NeuroSci 2024, 5, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Zanden, C.M.; Chi, E.Y. Passive Immunotherapies Targeting Amyloid Beta and Tau Oligomers in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2020, 109, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.F.; Zhang, D.; Hu, W.M.; Liu, D.X.; Li, L. Semaglutide-mediated protection against Aβ correlated with enhancement of autophagy and inhibition of apotosis. J Clin Neurosci 2020, 81, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Wang, L.X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, L.B. Liraglutide prevents beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells via a PI3K-dependent signaling pathway. Neurological research 2016, 38, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litus, E.A.; Kazakov, A.S.; Deryusheva, E.I.; Nemashkalova, E.L.; Shevelyova, M.P.; Machulin, A.V.; Nazipova, A.A.; Permyakova, M.E.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, S.E. Ibuprofen Favors Binding of Amyloid-beta Peptide to Its Depot, Serum Albumin. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, doi:ijms23116168 [pii]ijms-23-06168 [pii]10.3390/ijms23116168. [CrossRef]

- Catanzariti, A.M.; Soboleva, T.A.; Jans, D.A.; Board, P.G.; Baker, R.T. An efficient system for high-level expression and easy purification of authentic recombinant proteins. Protein Sci 2004, 13, 1331-1339, doi:13/5/1331 [pii]0131331 [pii]10.1110/ps.04618904. [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.N.; Vajdos, F.; Fee, L.; Grimsley, G.; Gray, T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci 1995, 4, 2411–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ferrari, G.V.; Mallender, W.D.; Inestrosa, N.C.; Rosenberry, T.L. Thioflavin T is a fluorescent probe of the acetylcholinesterase peripheral site that reveals conformational interactions between the peripheral and acylation sites. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 23282-23287, doi:S0021-9258(20)78313-4 [pii]10.1074/jbc.M009596200. [CrossRef]

- Deryusheva, E.I.; Shevelyova, M.P.; Rastrygina, V.A.; Nemashkalova, E.L.; Vologzhannikova, A.A.; Machulin, A.V.; Nazipova, A.A.; Permyakova, M.E.; Permyakov, S.E.; Litus, E.A. In Search for Low-Molecular-Weight Ligands of Human Serum Albumin That Affect Its Affinity for Monomeric Amyloid β Peptide. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. Natively unfolded proteins: a point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci 2002, 11, 739-756, doi:0110739 [pii]10.1110/ps.4210102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M.; Burley, S.K. Protein Data Bank (PDB): Fifty-three years young and having a transformative impact on science and society. Quarterly reviews of biophysics 2025, 58, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| [Lira], µM | ka, M-1s-1 | kd, s-1 | KD, M | ka, M-1s-1 | kd, s-1 | KD, M | |

| Lira | Aβ40 | Aβ42 | |||||

| 20 | (8.4±2.8)×103 | (9.0±0.4)×10-4 | (1.1±0.4)×10-7 | (5.7±1.1)×103 | (6.0±0.2)×10-4 | (1.1±0.2)×10-7 | |

| 10 | (7.3±0.4)×103 | (3.46±0.07)×10-4 | (4.8±0.3)×10-8 | (8.0±0.7)×103 | (4.82±0.12)×10-4 | (6.0±0.2)×10-8 | |

| 5 | (1.34±0.09)×104 | (5.56±0.11)×10-4 | (4.2±0.3)×10-8 | (1.21±0.08)×104 | (5.40±0.12)×10-4 | (4.5±0.3)×10-8 | |

| [Sema], µM | ka1, M-1s-1 | kd1, s-1 | KD1, M | ka2, M-1s-1 | kd2, s-1 | KD2, M | |

| Sema | Aβ40 | ||||||

| 17 | 310±52 | (3.7±0.2)×10-3 | (1.2±0.2)×10-5 | (5.7±1.1)×103 | (9.1±0.6)×10-2 | (1.6±0.3)×10-5 | |

| Aβ42 | |||||||

| 38 | 582±104 | (6.4±0.6)×10-3 | (1.1±0.2)×10-5 | (6.1±2.7)×103 | (1.34±0.15)×10-1 | (2.2±1.0)×10-5 | |

| [GLP-1RA], μM | ka1, M-1s-1 | kd1, s-1 | KD1, M | ka2, M-1s-1 | kd2, s-1 | KD2, M | |

| Aβ40 | |||||||

| Sema | 0.06-2 | (9.6±2.4)×103 | (3.2±0.9)×10-3 | (3.4±0.5)×10-7 | (3.90±1.12)×104 | (4.32±0.12)×10-2 | (1.2±0.4)×10-6 |

| Lira | 1-8 | (1.44±0.05)×103 | (1.19±0.13)×10-3 | (9.5±0.7)×10-7 | (1.9±0.3)×103 | (1.70±0.10)×10-2 | (9.1±1.6)×10-6 |

| Aβ42 | |||||||

| Sema | 0.06-2 | (1.26±0.11)×104 | (4.1±1.4)×10-3 | (3.4±1.4)×10-7 | (1.34±0.18)×105 | (3.8±0.7)×10-2 | (3.0±0.9)×10-7 |

| Lira | 1-8 | (2.24±0.18)×103 | (1.14±0.10)×10-3 | (5.2±0.8)×10-7 | (2.9±0.04)×103 | (1.64±0.14)×10-2 | (5.6±0.3)×10-6 |

| GLP-1RA | [GLP-1RA], µM | Rh, nm | MWRh, kDa | MWRh/MWm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1(7-37) | 5-83 | >92 | >7×105 | >210 |

| Lira | 105 | 3.08±0.15 | 54.7±7.8 | 15.6±2.2 |

| 52 | 3.13±0.05 | 57.1±2.6 | 16.3±0.7 | |

| 13 | 2.25±0.12 | 22.7±6.1 | 6.5±1.7 | |

| 6 | 2.45±0.16 | 28.8±3.6 | 8.2±1.0 | |

| Exen | 234 | 2.20±0.01 | 24.58±0.02 | 5.88±0.04 |

| 115 | 2.27±0.16 | 26.7±5.7 | 6.4±1.4 | |

| 29 | 1.53±0.06 | 8.8±0.9 | 2.1±0.2 | |

| 15 | 1.39±0.07 | 6.7±0.9 | 1.6±0.2 | |

| Sema | 47 | 1.22±0.04 | 4.1±0.4 | 1.2±0.1 |

| 12 | 1.42±0.15 | 6.2±2.1 | 1.9±0.6 |

| Minimal KD for Aβ Binding According to BLI | Effect on Aβ40 Fibrillation (Figure 4 and Figure 5) | Effect on Aβ Cytotoxicity to SH-SY5Y Cells (Figure 7) | Ability to Cross the BBB | AD Animal Data | Clinical Data, AD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lira | 4.2×10-8 M | No effect | Protection | + [47] | Prevents memory loss, reduces Aβ amyloid deposits [47,48,49] | No effect [50] |

| Sema | 1.1×10-5 M | Stimulation | Protection | − [74] | Positive effects on cognitive function, reduction of Aβ amyloid deposits [55] | Phase 3 clinical trials (NCT04777396 and NCT04777409) |

| Exen | ~(0.4–1.5)×10-5 M | Inhibition | Protection | + [73] | Positive effects on learning and memory ability, reduces Aβ deposition [38,39,40,41] | No effect [43] |

| GLP-1(7-37) | ~(2.5–5.0)×10-5 M | Inhibition | Increases Aβ40 cytotoxicity | + [24] | Positive effects on learning and memory [29] | No data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).