1. Introduction

Many derivatives of 4-aminoquinoline are well known antiparasitic medicines used in the treatment and prophylaxis of malaria. The same structural fragment has been used as building block to designed and synthesized drug highly effective in treating many types of disease including viral diseases and different types of cancer [

1].

Pharmaceutical drugs typically can exist in different crystal or solid-state forms like polymorphs, solvates/hydrates and amorphous that can differ widely in their physical properties such as encompass solubility, dissolution rate, melting point, tablet formation capabilities. These differences can significantly impact the performance and bioavailability of pharmaceutical products [

2]. A thorough structural characterization is essential for understanding the relative stability of polymorphic and solvate forms and plays a critical role in the development of new drugs as well as the optimization of crystallization processes and formulation strategies [

3].

Similarly, to ensure the reliability of activity studies for a drug or its analogous derivatives used for comparison, it is crucial to confirm the nature of the products in their solid state, also through straightforward analytical methods [

4]. However, this can only be achieved if the required experimental data are readily available. In industrial drug production, structural identification is an essential part of a rigorous quality control ensuring that products meet expected specifications and maintain high standards of efficacy and consistency across batches.

In this article, it is reported the crystal structure of a monohydrate adduct of 7-Chloro-4-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)quinoline (

BPIP∙H2O), a truncated analogue of the piperazinyl-quinoline class of active antimalarial compounds.

BPIP corresponds to half a molecule of piperaquine (PQ), a compound widely used in the past for the treatment of chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria and recently rediscovered as a promising partner in combination therapies, including artemisinin-based strategies [

5]. Therefore, the title compound can serve as a simplified molecular entity of some antimalarials, making it an effective model system to study drug action [

6,

7] and the interactions with biologically relevant metal ions. Consequently, its solid-state characterization holds significant importance.

2. Results

2.1. Solid-State Structure

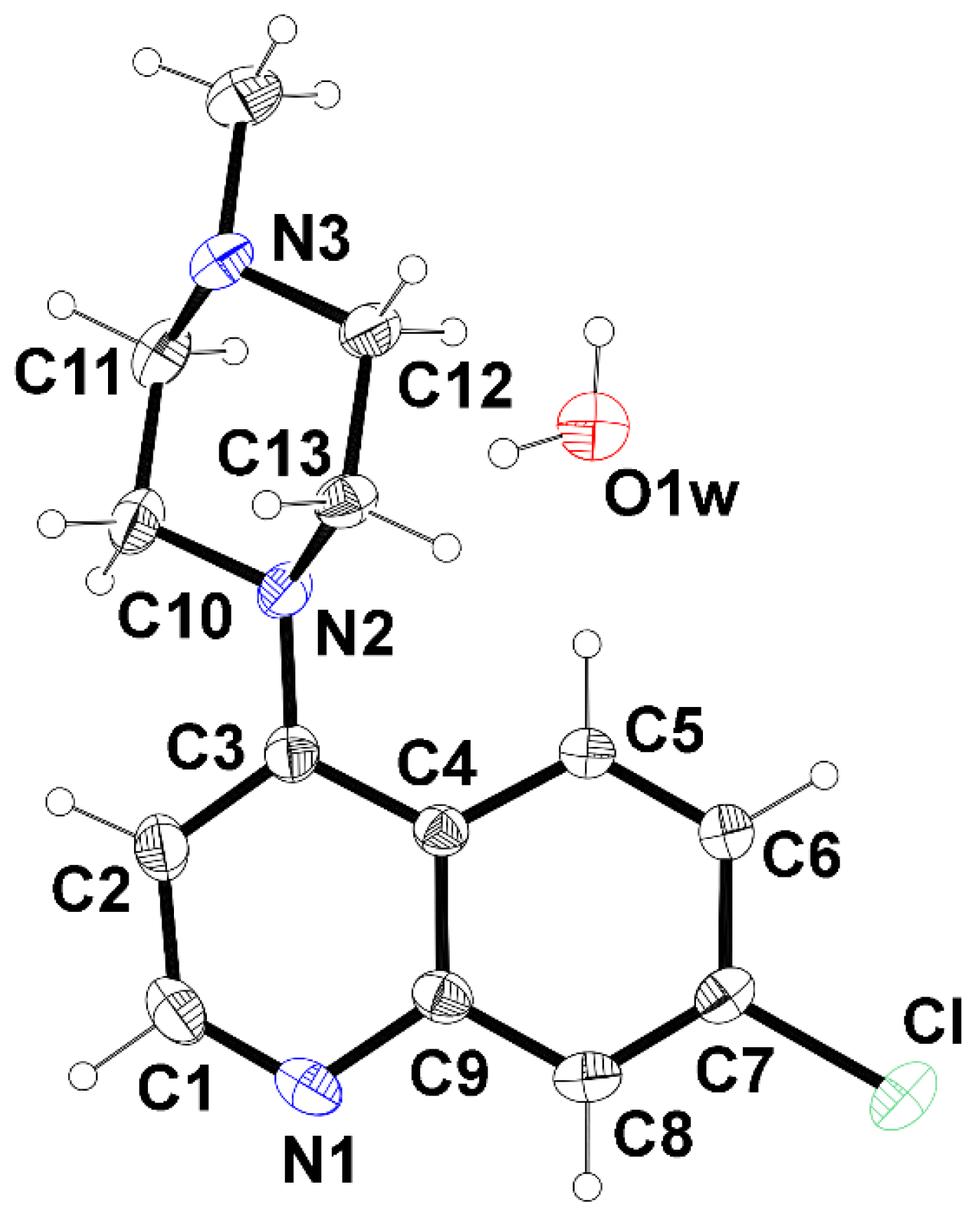

Single crystal data revealed that the

BPIP∙H2O structure crystallizes in the monoclinic system with the space group

P2₁/

c. The asymmetric unit comprises one independent quinoline derivative and one water molecule (

Figure 1).

The quinoline double-ring shows a distortion from the planarity (rms deviation from the best fit plane 0.0567 Å) with the benzene and pyridine inclined at a dihedral angle of 5.828(27)° with respect to each other. The piperazinyl ring adopts a chair conformation with puckering parameters of Q = 0.5886(16) Å and θ = 178.43(16)° [

8] and is oriented at a dihedral angle of about 39.1° with respect to the quinoline moiety.

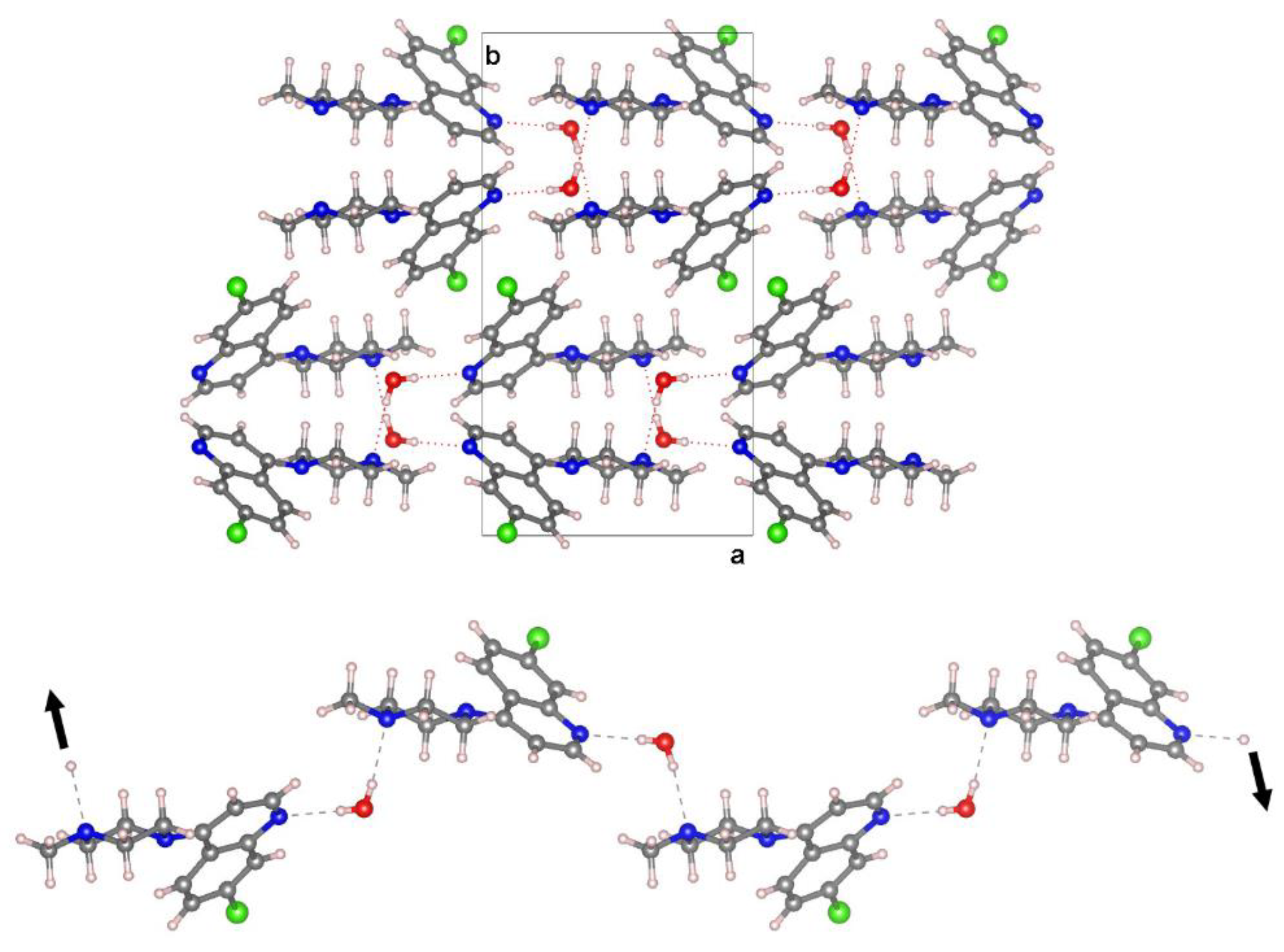

In the crystal structure

BPIP and water molecules are alternatively linked via hydrogen-bonding interactions into chains running along the [20-1] direction generated by the glide plane

c (

Figure 2). The water molecule acts as a double donor to the pyridinic nitrogen and the terminal N atom of the piperazinyl group generating quasi-linear hydrogen bonds (O⋯N distance (Å), OHN angle (°): 2.9194(19), 175(3); 2.9417(19),166(2)) (

Table 1S).

Volumetric analysis indicates that water molecules occupy 3.2% of the unit cell volume (probe radius of 1.0 Å) and reside within discrete, isolated pockets of the crystal framework without discernible pathways to egress.

2.2. Intermolecular Interaction Analysis

The “

Aromatics Analyser” functionality in the CSD-Materials [

9] was employed to identify and quantify aromatic interactions within the crystal lattice. The analysis shows that the crystal structure is stabilized by a strong π–π interaction involving the chloro-benzene rings of the quinoline unit (score 9.5). Aromatic stacking dimers are formed in which molecules are related by inversion symmetry. The dimers exhibit a parallel displaced arrangement with a centroid–centroid distance of 3.96 Å and a relative orientation angle of 0° (

Table 2S).

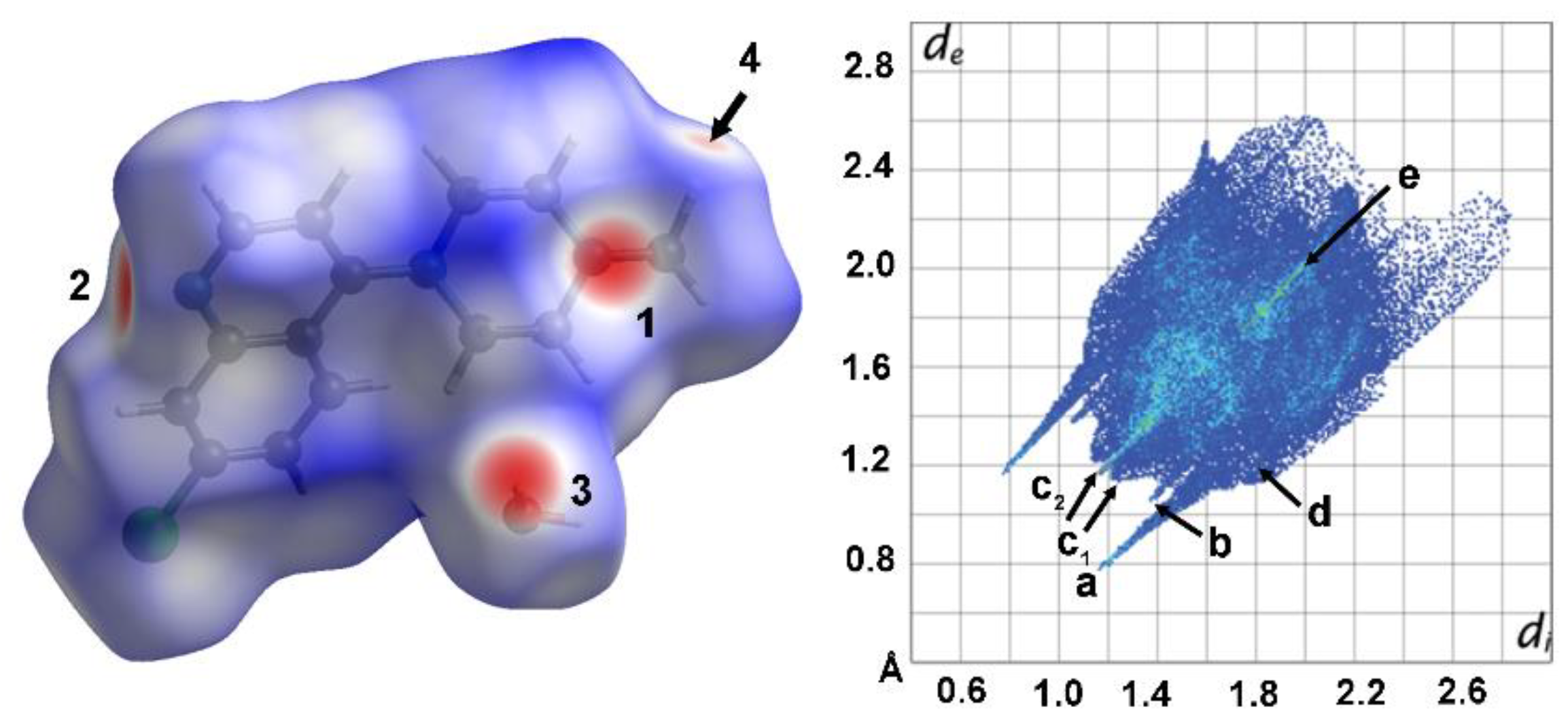

Hirshfeld surface (HS) and 2D fingerprint (FP) analysis were further performed by using

CrystalExplorer [

10] to investigate, visualize and quantitatively evaluate the intermolecular interactions within the crystal packing of the title compound (

Figure 3,

1S and 2S). The greatest contribution to the HS comes from the H⋯H contacts (51.3%), due to the large hydrogen content of the molecule, responsible for the widespread, high-density blue point distribution in the FP with two beak-shaped tips at d

e + d

i ≈ 2.5 Å (c

1 in

Figure 3). The light blue stripe roughly along the diagonal reflects the fraction of points on the Hirshfeld surfaces that involve nearly head-to-head H∙∙∙H contacts with an almost linear orientation between two couples of axial hydrogens of neighboring piperazinyl ring (c

2 in

Figure 3).

The characteristic pair of long outer spikes with their tips at d

e + d

i ∼1.8 Å (a in

Figure 3) are due to the presence of the O

water—H⋯N

pyridinic hydrogen bond, that covers 9.6% of the overall crystal packing. The O⋯H contacts make a 5.9% contribution to the HS and are represented by a second shorter pair of spikes in the region d

e + d

i ≃ 2.2 Å (b in

Figure 3). This feature underscores the role of water oxygen atom as an acceptor in a weak intermolecular C—H⋯O hydrogen bond, with the terminal methyl group of the piperazinyl ring (2.567 Å). The short interatomic C···H/H···C and Cl⋯H/H⋯Cl contacts are overlapped in the FP and appear as a forceps-like distribution with parabolic tips at d

e + d

i ∼2.8 Å (C⋯H) and 3.0 Å (Cl⋯H) respectively (d in

Figure 3). Their overall contributions are: 14.4% for C···H/H···C and 10.7% for Cl⋯H/H⋯Cl. The contribution of C···H/H···C contacts largely correspond to the aromatic interactions described above. The decomposition of fingerprint plots into individual atom–atom interactions are depicted in

Figure 1S and 2S.

Comparison of these results with the Hirshfeld surface analyses conducted separately on BPIP and water molecule, reveals that hydrogen bonding dominates the water-BPIP interactions, while the supramolecular assembly primarily arises from other intermolecular contacts, predominantly involving the primary molecule.

3. Discussion

Knowledge of the solid-state structure of a molecule is crucial for evaluating its properties and reactivity, by using both experimental and computational methods. However, till now crystallographic data are available for some compounds analogous to

BPIP such as 7-Chloro-4-(piperazin-1-yl)quinoline [

11] but not for

BPIP system. Thus, to determine the crystal structure and the packing architecture of the title compound a single-crystal X-ray diffraction study has been performed. The structure determination revealed that the solid phase is the monohydrate form of the substance showing an extended hydrogen-bonding network involving water-

BPIP interactions.

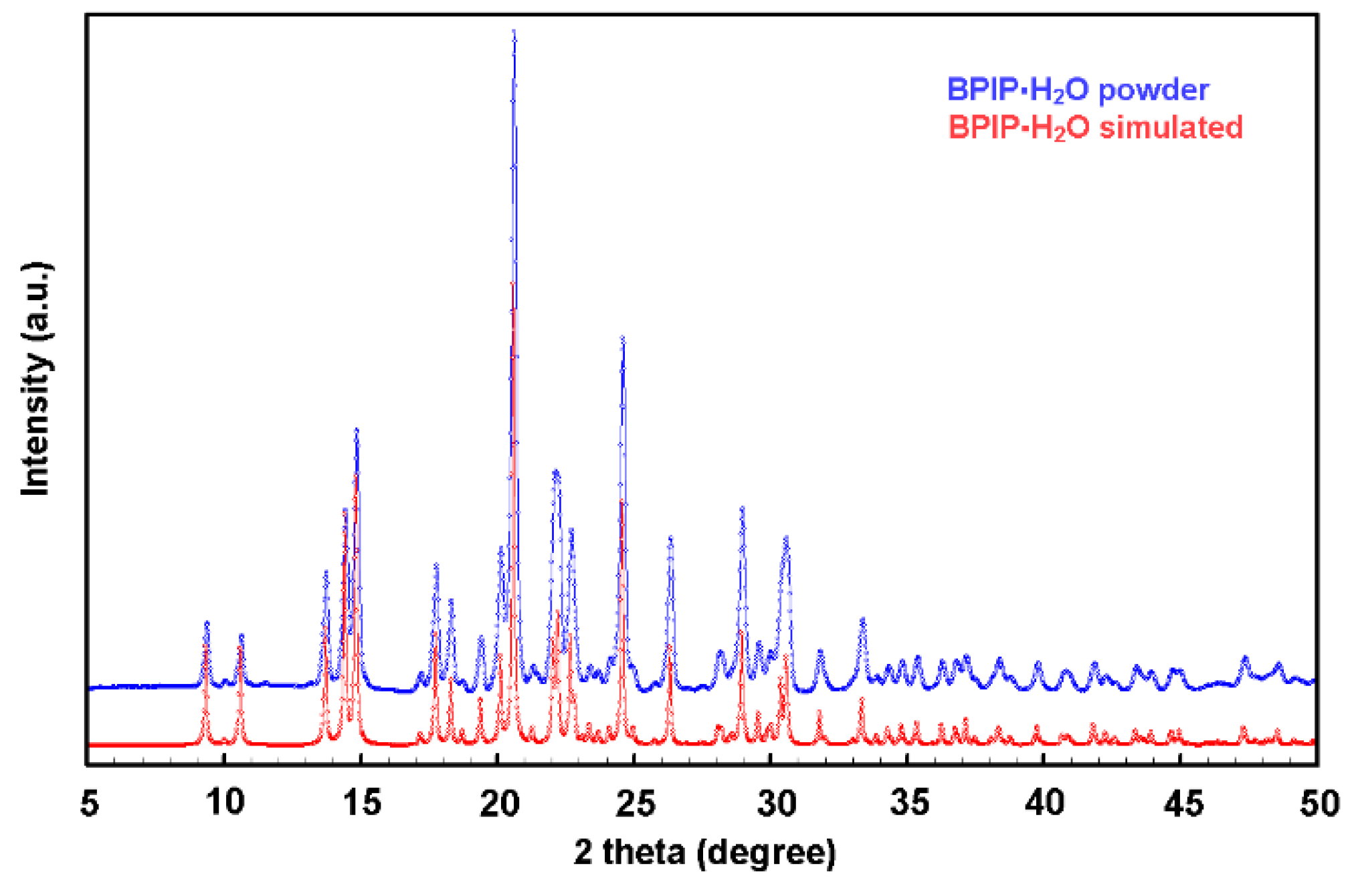

To understand if the hydration water was already present in the source material or was incorporated during the crystallization process a powder diffraction experiment was carried out on the starting bulk material. The nature of the reactive was assessed by taking and testing the whole content of a freshly opened 100 mg -vial of the reactive as supplied by the manufacturer.

The experimentally observed PXRD pattern shown in

Figure 4 was found to be in agreement with the simulated pattern obtained from the single-crystal data, confirming the hydration state of the commercial product and the bulk homogeneity of the samples. The melting point of the compound was measured and compared with literature data to establish a reliable, easily obtainable, and cost-effective reference value for assessing the substance's identity and purity. The measurement, conducted using a standard melting point apparatus, yielded a range of 82.8–83.5 °C. This result shows a reasonable consistency with the findings reported in Reference [

12] (86°C), where isopropanol was used as recrystallization solvent. Other available melting point data report relatively different values, i.e. 80°C [

13] for a pale-brown solid precipitated from an aqueous solution and subsequently dried, and 88-89°C [

14] for white crystals obtained from methanol with a mass corresponding to the anhydrous form measured by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS).

The identification of anhydrous and hydrated forms of a drug substance is of great importance to ensure that products meet expected specifications in terms of bioavailability [

15]. Hydrate form with a well-defined stoichiometric water content exhibits a unique molecular arrangement in the solid state generated by a complex and extended hydrogen bond network, that is responsible for the characteristic physical and chemical properties of the compound.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The 7-Chloro-4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)quinoline (BPIP) (CAS number: 84594-63-8) was purchased from Merk Life Science S.r.l., Italy. The reactive is a Sigma-Aldrich product sold without any assurance as to the identity and purity of the product. 2-propanol was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich and was ACS reagent grade. The materials were used as received, without any further purification.

4.2. X-ray Single-Crystal Diffraction

Materials X-ray-quality crystals were obtained by slow evaporation of an isopropanol solution of BPIP at room temperature.

The single-crystal X-ray data collection for

BPIP-H2O was performed on air-stable single crystal mounted on a glass fiber at a random orientation on a Bruker SMART-APEX II diffractometer[

16] equipped with a graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). The data were collected by ω-scan method (width of 0.5° frame

-1, exposure time of 20 sec. per frame) within the limits 2.2°< θ < 31.7°.

Cell parameters were retrieved and refined using the SAINT software [

17] on 1624 reflections (19 % of the observed reflections). Data processing and space group determination were performed with SAINT and XPREP program [

17]. The structures were solved by direct methods (SIR2019) and refined by full-matrix least squares on

F2 (SHELX 2018) [

18] with the WINGX interface [

19]. The collected intensities were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects and for absorption effects by applying a multi-scan method by using the SADABS program [

17]. The structure pictures were generated using the ORTEPIII [

19] and VESTA programs [

20].

All non-H atoms were refined with full occupancies and anisotropic displacement parameters. No disorder was observed. All hydrogen atoms were located from the difference-Fourier map and were refined using a riding model

Uiso = 1.5

Ueq (parent atom) for H-methyl group and -OH and

Uiso = 1.2

Ueq (parent atom) for -CH- and -CH

2-. Bond lengths and angles are summarized in

Tables 3S.

Crystal data and refinement details for BPIP∙H2O: C14H16ClN3·H2O, Mr = 279.76, T = 296(2) K, λ = 0.71073 Å, monoclinic, space group P21/c, a = 9.4737 (11), b = 17.650 (2), c = 8.5451 (10) Å, β = 90.156 (2)◦ , V = 1428.9 (3) Å3 , Z = 4, ρcalc = 1.300 g cm−3 , µcalc = 0.264 mm−1 , F(000) = 592, crystal size 0.42 × 0.30 × 0.04 mm, θ range = 2.2–31.7°, 22429 reflections collected, 4534 reflections unique, Rint = 0.0287, observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)] 2831, 0 restraints, 226 parameters, R1 (all data) = 0.0857, wR2 (all data) = 0.1247, R1 (observed) = 0.0434, wR2 (observed ) = 0. 0.1052, ∆ρmax = 0.25 eÅ−3 , and ∆ρmin = −0.21 eÅ−3 .

4.3. X-ray Powder Diffraction

Ambient X-ray powder diffraction measurements were performed using a Miniflex-600 diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) with Cu Kα (

λ = 1.540598 Å) radiation over the angular range of 5°-60° (2

θ), with an incremental step size of 0.02° (2θ) and a counting time of 2 sec∙step

-1. Phase identification was performed by comparing the experimental powder pattern with that simulated from single-crystal data. Analysis of PXRD data was done by using

FullProf suite software [

21].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure 1S, Figure 2S, Table 1S, Table 2S, Table 3S.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; methodology; validation; formal analysis, S.R.; investigation, S.R. and F.M.; resources, S.R.; data curation, S.R. and F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.; writing—review and editing, S.R. and F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Università degli Studi di Milano is acknowledged for funding this work through the Research Support Plan 2024 (Piano di Sostegno alla Ricerca 2024), grant number PSR2023_DIP_005_PI_FTESS.

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2443163 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. The data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via

www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Pietro Colombo for technical assistance with the single-crystal X-ray experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BPIP |

7-Chloro-4-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)quinoline |

| PQ |

Piperaquine |

| PXRD |

X-ray Powder Diffraction |

References

- Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Zou, C.; Zhang, J. Chloroquine against Malaria, Cancers and Viral Diseases. Drug Discov Today 2020, 25, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espeau, P. Special Issue “Pharmaceutical Solid Forms: From Crystal Structure to Formulation. ” Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurczak, E.; Mazurek, A.H.; Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Pisklak, D.M.; Zielińska-Pisklak, M. Pharmaceutical Hydrates Analysis—Overview of Methods and Recent Advances. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilfiker, R.; Blatter, F.; Raumer, M. von Relevance of Solid-state Properties for Pharmaceutical Products. In Polymorphism; Wiley, 2006; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T.M.E.; Hung, T.-Y.; Sim, I.-K.; Karunajeewa, H.A.; Ilett, K.F. Piperaquine. Drugs 2005, 65, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warhurst, D.C.; Craig, J.C.; Adagu, I.S.; Guy, R.K.; Madrid, P.B.; Fivelman, Q.L. Activity of Piperaquine and Other 4-Aminoquinoline Antiplasmodial Drugs against Chloroquine-Sensitive and Resistant Blood-Stages of Plasmodium Falciparum. Biochem Pharmacol 2007, 73, 1910–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackovic, K.; Parisot, J.P.; Sleebs, N.; Baell, J.B.; Debien, L.; Watson, K.G.; Curtis, J.M.; Handman, E.; Street, I.P.; Kedzierski, L. Inhibitors of Leishmania GDP-Mannose Pyrophosphorylase Identified by High-Throughput Screening of Small-Molecule Chemical Library. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 1712–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, D.; Pople, J.A. General Definition of Ring Puckering Coordinates. J Am Chem Soc 1975, 97, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0 : From Visualization to Analysis, Design and Prediction. J Appl Crystallogr 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spackman, P.R.; Turner, M.J.; McKinnon, J.J.; Wolff, S.K.; Grimwood, D.J.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. CrystalExplorer : A Program for Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, Visualization and Quantitative Analysis of Molecular Crystals. J Appl Crystallogr 2021, 54, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, A.A.; King, C.L.; Fortunak, J.M.D.; Butcher, R.J. 7-Chloro-4-(Piperazin-1-Yl)Quinoline. Acta Crystallogr Sect E Struct Rep Online 2012, 68, o1497–o1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dann, O.; Steuding, W.; Lisson, K.G.; Seidel, H.R.; Fink, E.; Nickel, P. [Antimalarial 6-aminoquinolines XV. 6- and 4-aminoquinolines with a tertiary basic alkylated amino group]. Arzneimittelforschung 1982, 32, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Staderini, M.; Cabezas, N.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Menéndez, J.C. Solvent- and Chromatography-Free Amination of π-Deficient Nitrogen Heterocycles under Microwave Irradiation. A Fast, Efficient and Green Route to 9-Aminoacridines, 4-Aminoquinolines and 4-Aminoquinazolines and Its Application to the Synthesis of the Drugs Amsacrine and Bistacrine. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 1024–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warhurst, D.C.; Craig, J.C.; Adagu, I.S.; Guy, R.K.; Madrid, P.B.; Fivelman, Q.L. Activity of Piperaquine and Other 4-Aminoquinoline Antiplasmodial Drugs against Chloroquine-Sensitive and Resistant Blood-Stages of Plasmodium Falciparum. Biochem Pharmacol 2007, 73, 1910–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khankari, R.K.; Grant, D.J.W. Pharmaceutical Hydrates. Thermochim Acta 1995, 248, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Bruker APEX2 V2014.1-1; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2015.

-

Bruker SAINT v8.34A, XPREP V2013/3, SADABS 2013, Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2013.

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr C Struct Chem 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An Update. J Appl Crystallogr 2012, 45, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. urn:issn:0021-8898 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Carvajal, J. FULLPROF: A Program for Rietveld Refinement and Pattern-Matching Analysis. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the meeting Powder Diffraction; Toulouse, France; 1990; pp. 127–128. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).