1. Introduction

Sepsis and resulting septic shock are the leading causes of intensive care unit admission and mortality among critically ill patients. Up to 25% of annual hospitalizations are due to sepsis [

1] with mortality rates ranging from 15 to 56%. If adequate treatment is not administered in time, mortality can reach 70-90% [

2,

3].

Sepsis is a dysregulated immune response to infection, which leads to systemic inflammation and organ dysfunction. Cytokines are small proteins released primarily by immune cells. Cytokines mediate immune responses and play a major role in the pathophysiology of sepsis and inflammation. During the early stages of sepsis pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) are released, starting the inflammatory cascade [

4]. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1) is secreted by monocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells in response to inflammatory stimuli and recruits monocytes, macrophages, and T cells to inflammation sites. MCP-1 contributes to the cytokine storm in sepsis, leading to immune dysregulation and organ damage [

5]. Elevated IL-8 levels correlate with worse outcomes in septic patients, as excessive neutrophil activation contributes to organ damage [

6].

Conversely, anti-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-10 (IL-10) act to counterbalance excessive inflammation but may also lead to immune suppression, increasing susceptibility to secondary infections and poor outcomes [

7]. Interleukin-17 (IL-17) has a dual role some studies suggest a pro-inflammatory function, others highlight its protective effects [

8]. Recent studies have highlighted the role of cytokine networks in sepsis progression. Other cytokines further exacerbate the inflammatory response in sepsis [

9]. Murine sepsis models are used to investigate both the changes in cytokine levels that occur during sepsis and the effects of various drugs on different cytokines [

10,

11]. These models allow for the simulation of the cytokine storm observed in humans, while also enabling the study of treatments that specifically target cytokines [

12].

Levosimendan is a Ca

++ sensitizing inotropic drug that enhances myocardial contractility and is primarily used to manage acute decompensated heart failure. Some studies indicate that levosimendan has anti-apoptotic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, which may contribute to preserving renal and cardiac functions in heart failure [

13,

14]. In the treatment of septic shock, both myocardial support with inotropic drugs and the preservation of myocardial cell viability are crucial. Given its anti-inflammatory effects, levosimendan may provide an additional therapeutic advantage in sepsis and septic shock.

Levosimendan has been shown to modulate systemic inflammatory responses, potentially mitigating the progression of organ failure and reducing mortality [

15]. This study was designed to investigate the effects of levosimendan on the clinical course of sepsis and cytokine production within the first 10 hours in a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced sepsis model in rats.

2. Materials and Methods

All animal procedures adhered to the European Community guidelines (2010/63/EU) (15), and the ARRIVE guidelines for animal experiments [

16]. The Institutional Animal Experiments Ethics Committee approved the study. Thirty-two male Wistar Albino rats (3–6 months old, 450–550 g) were housed under standard laboratory conditions: 12-hour light/dark cycle, room temperature, with free access to dry food pellets and water.

Rats were randomly assigned to four groups (n=8 per group): Sham Group (A): No interventions; baseline cytokine levels were assessed in healthy animals. Sepsis Control Group (B): Received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 5 mg/kg to induce sepsis; no subsequent treatment. Low-Dose Levosimendan Group (C): Sepsis induced with LPS (5 mg/kg i.p.), followed by levosimendan administration (1 mg/kg i.p.) two hours later. High-Dose Levosimendan Group (D): Sepsis induced with LPS (5 mg/kg i.p.), followed by levosimendan administration (2 mg/kg i.p.) two hours later.

Two hours post-LPS administration, groups B, C, and D were assessed using the Murine Sepsis Score (MSS). Group A was evaluated prior to blood sampling. MSS evaluates multiple physiological and behavioral parameters such as general appearance, activity level, respiratory distress, eye and skin changes and body temperature. Each parameter is scored numerically from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicating more severe sepsis progression [

17].

Blood collection and euthanasia were conducted under general anesthesia. Anesthesia was induced with xylazine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (50 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally.

Sham Group (A): Intracardiac blood samples were collected once, followed by euthanasia via cervical dislocation. Sepsis Groups (B, C, D): Tail vein blood samples (1 mL) were collected five hours post-LPS administration. Intracardiac blood samples were obtained ten hours post-LPS, followed by euthanasia. Samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes, and sera were stored at -80 °C until analysis.

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17 and MCP-1 were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, following the manufacturer’s protocols. Chemicals and Reagents: LPS (055:B5): Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA., Levosimendan (3001077): Abbott Laboratories, Green Oaks, IL, USA., ELISA Kits: BT LAB, Shanghai, China.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as Mean ± standard deviation. Mixed-effects models with random intercepts analyzed differences between groups, considering effects of group, time, and their interaction. Pairwise comparisons utilized least squares means. Analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2), with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

3. Results

Murine Sepsis Score (MSS)

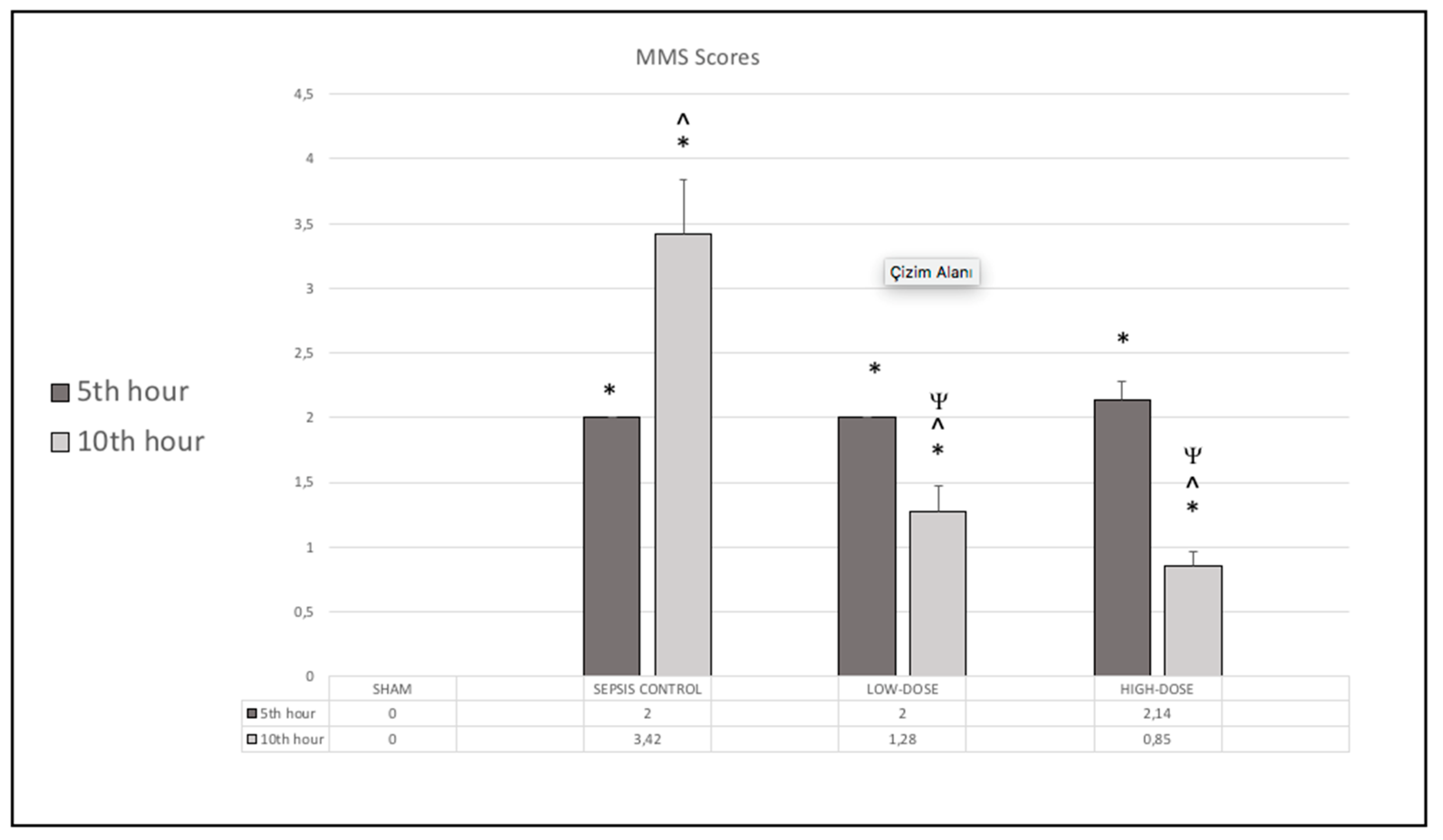

All LPS-injected rats exhibited clinical signs of sepsis by the 5

th hour. MSS scores were significantly higher in all LPS-injected groups at this time point compared to the sham group (p < 0.05), confirming systemic inflammation. By the 10

th hour, the MSS score had further increased in the sepsis control group. However, both levosimendan-treated groups showed a significant reduction in MSS scores at the 10

th hour, with the high-dose group demonstrating the most pronounced improvement in MSS scores (

Figure 1).

Cytokine Levels

Cytokine concentrations were measured at the 5th and 10th hours post-LPS administration.

Table 1 presents the serum cytokine concentrations of all study groups.

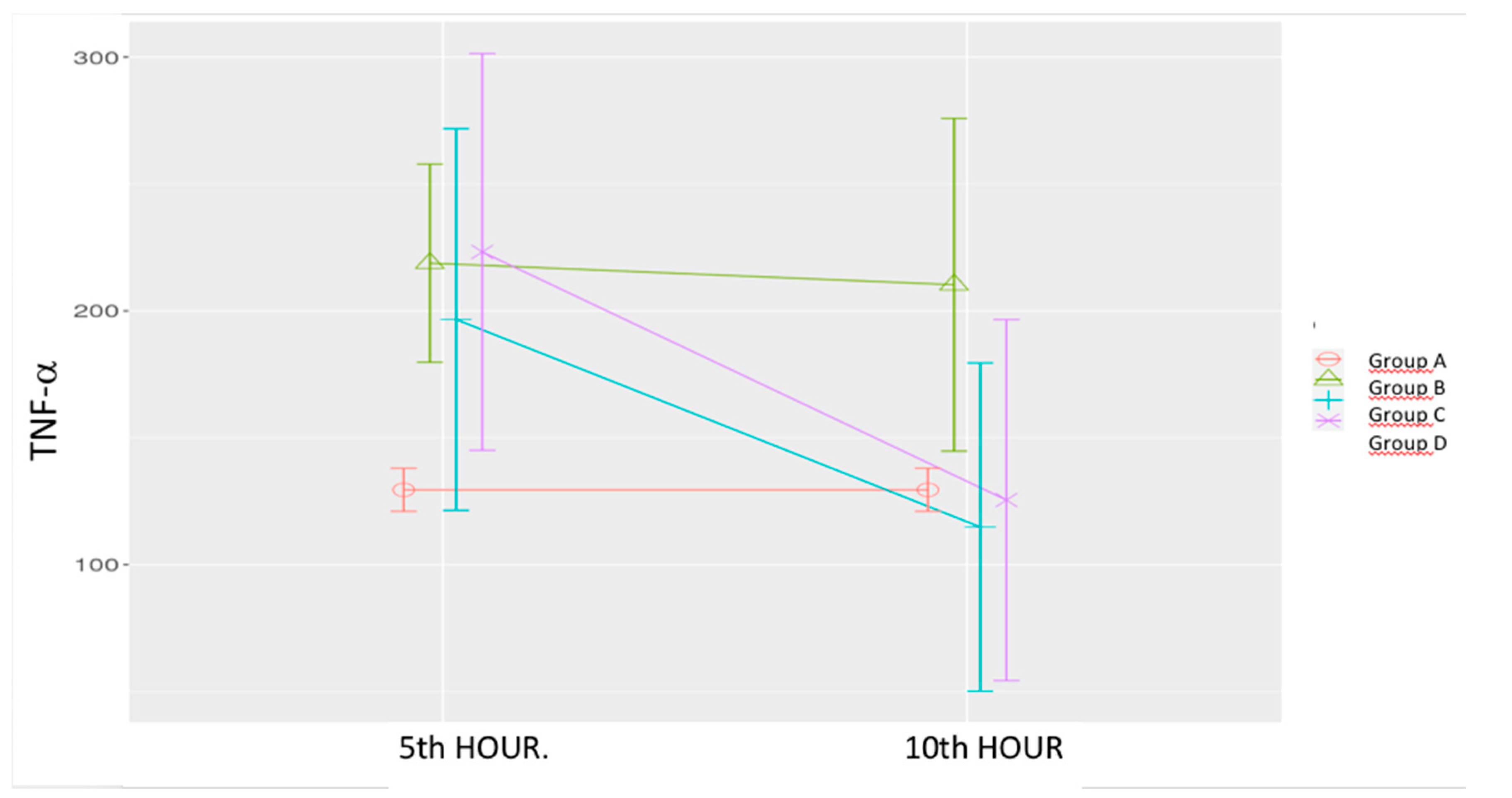

Sepsis Control Group (B): TNF-α levels were significantly elevated at both the 5th and 10th hours compared to the Sham group.

Low-Dose Levosimendan (C): TNF-α levels did not significantly differ from the sham or sepsis control groups at the 5th hour. However, a significant reduction was observed at the 10th hour compared to both the 5th hour of the same group and the 10th hour of the sepsis control group.

High-Dose Levosimendan (D): A significant increase in TNF-α was observed at the 5

th hour compared to the sham group. However, a significant reduction was noted at the 10

th hour compared to the 5

th-hour measurement which was similar to the sham group. (

Table 1,

Figure 2).

Mixed model analysis demonstrated significant effects of time (p = 0.003), group (p = 0.035), and time-group interaction (p = 0.051).

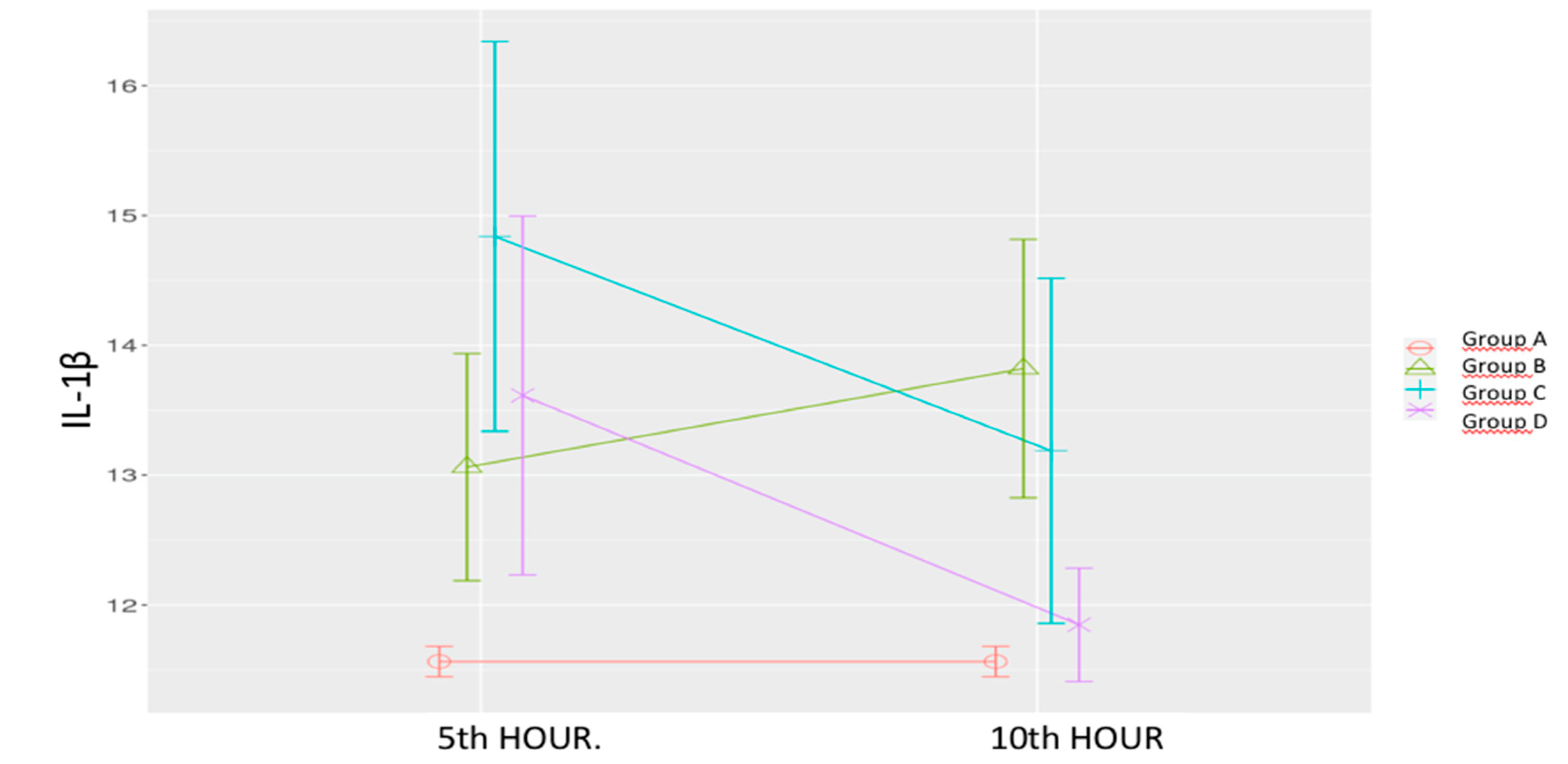

Sepsis Control Group (B): IL-1β levels increased at both time points, with a statistically significant rise at the 10th hour compared to the Sham group.

Low-Dose Levosimendan (C): IL-1β levels were significantly elevated at the 5th hour compared to both the sham and sepsis control groups. A significant decrease was observed at the 10th hour; however, levels remained significantly higher than those of the sham group.

High-Dose Levosimendan (D): IL-1β levels at the 5

th hour were significantly higher than the sham group but showed a significant reduction at the 10

th hour compared to both the sepsis control group and the 5

th-hour measurement. (

Table 1,

Figure 3).

Mixed model analysis revealed significant effects of time (p = 0.032), group (p < 0.001), and time-group interaction (p = 0.011).

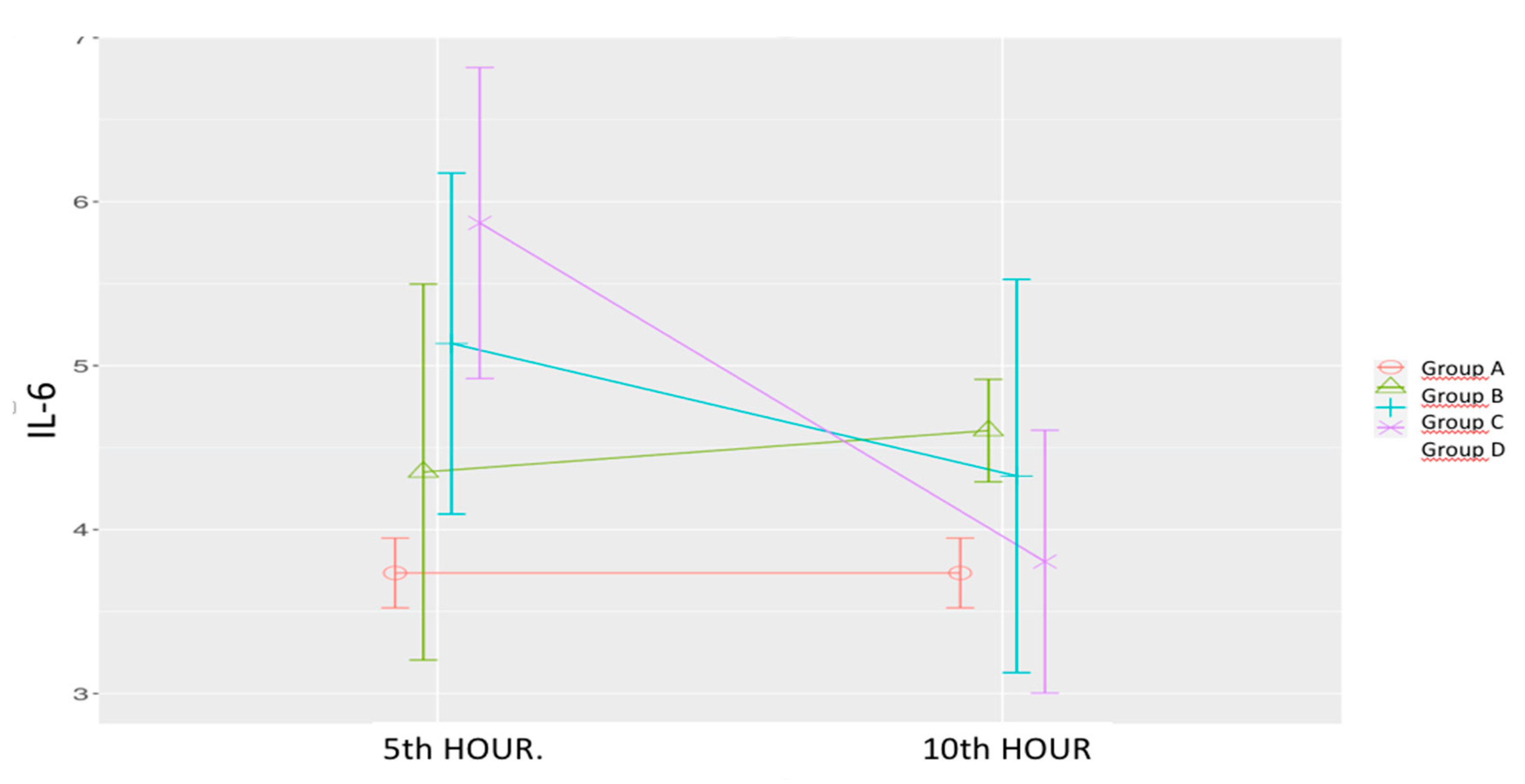

Sepsis Control Group (B): IL-6 levels increased at both the 5th and 10th hours, with a statistically significant increase at the 10th hour.

Low-Dose Levosimendan (C): IL-6 levels at the 5th hour were significantly higher than those in the sham group. A non-significant decrease was observed at the 10th hour compared to the 5th which was non-significant to the sham group.

High-Dose Levosimendan (D): IL-6 levels were significantly higher at the 5

th hour compared to both the sham and sepsis control groups. However, a significant reduction was observed at the 10

th hour, aligning levels with those of the sham group. (

Table 1,

Figure 4)

Statistical Analysis: Significant effects were observed for time (p = 0.008), group (p = 0.031), and time-group interaction (p = 0.005)

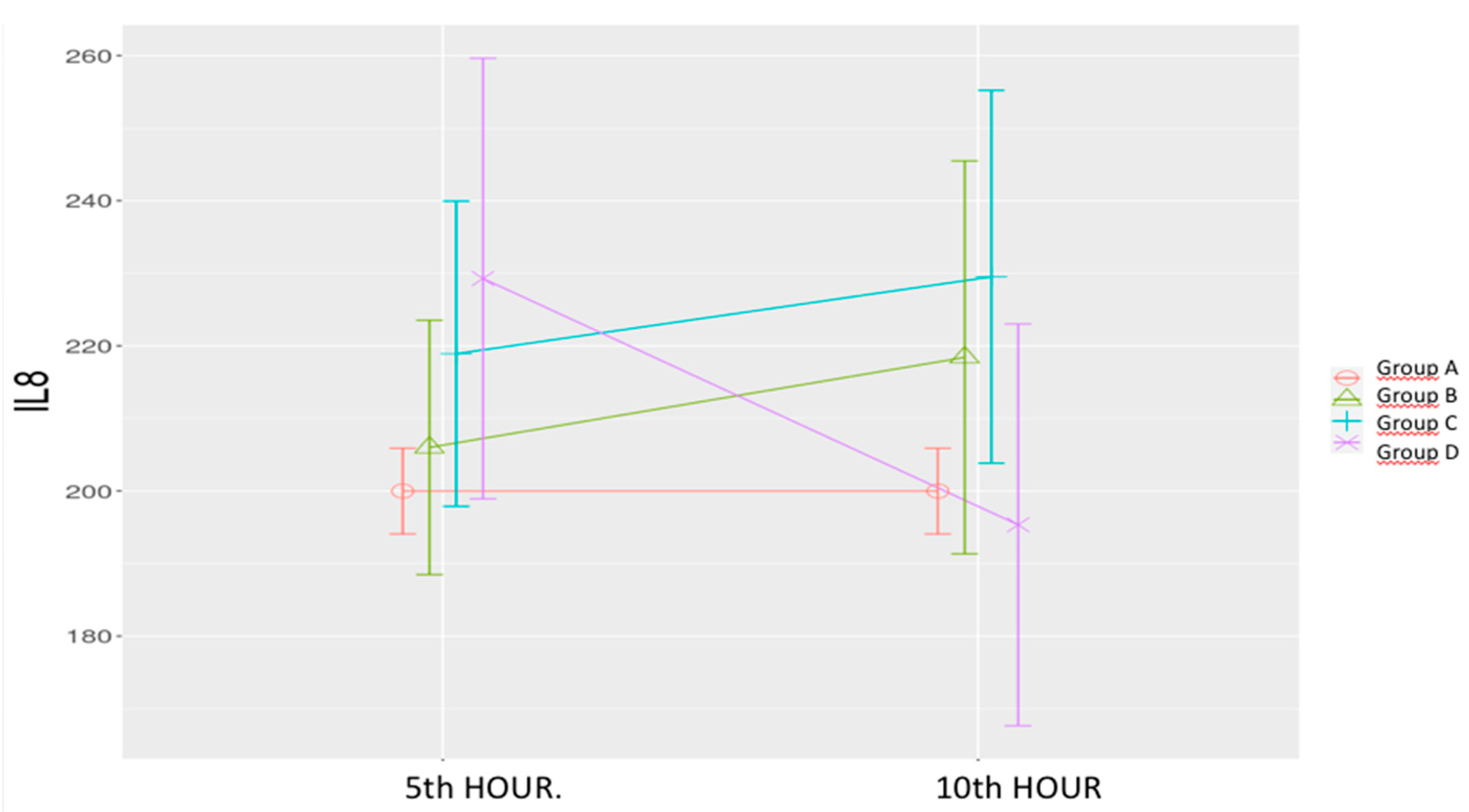

Sepsis Control Group (B): IL-8 levels showed a non-significant increase.

Low-Dose Levosimendan (C) & High-Dose Levosimendan (D): Non-significant increases were observed at both time points. However, a significant decrease was noted between the 5

th and 10

th hours in the high-dose group. (

Table 1,

Figure 5)

The time-group interaction was significant (p = 0.025).

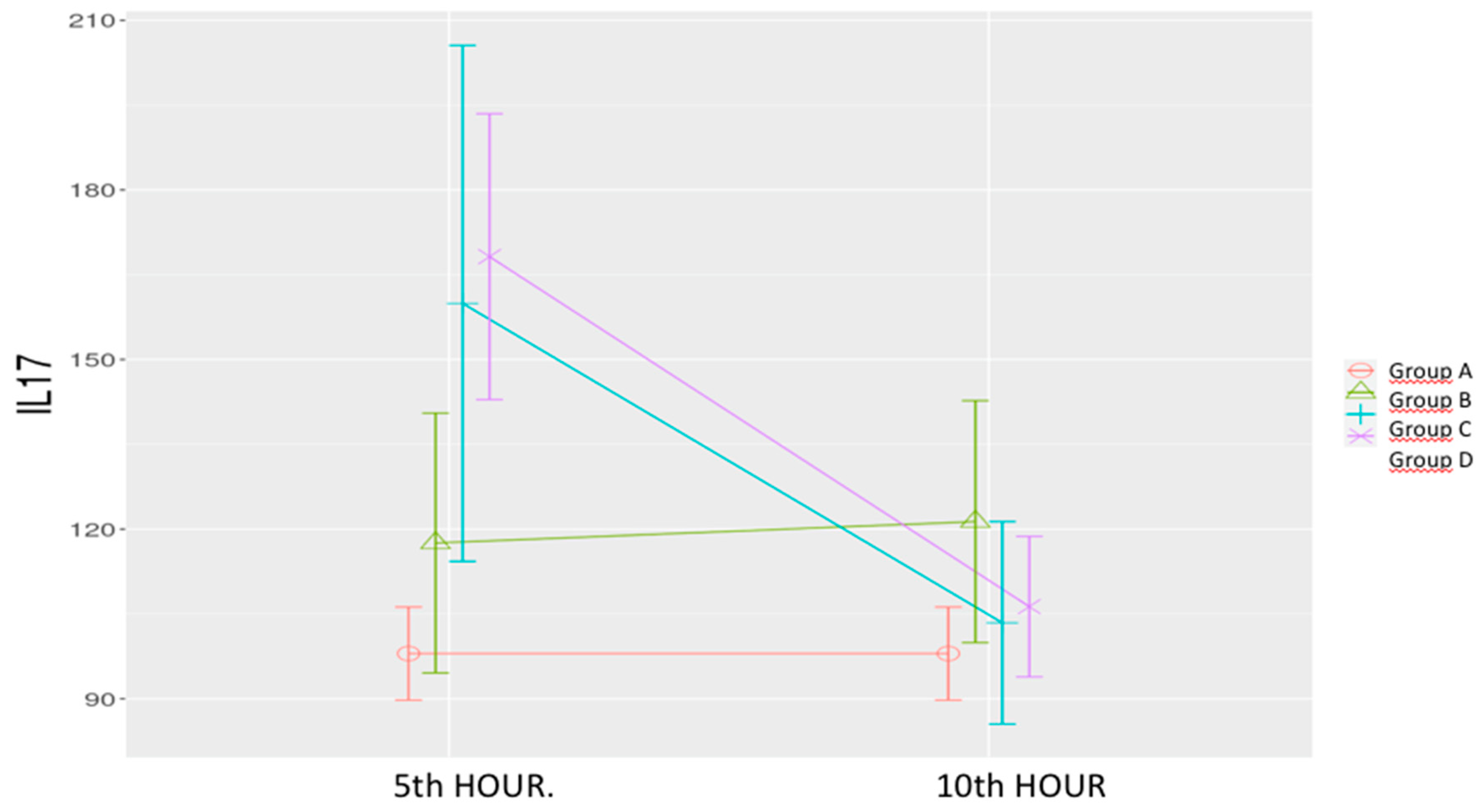

Sepsis Control Group (B): IL-17 levels increased non-significantly at both time points.

Low-Dose & High-Dose Levosimendan (C & D): A significant increase was noted at the 5

th hour compared to both the sham and sepsis control groups. By the 10

th hour, levels significantly decreased, aligning with those of the sham group. (

Table 1,

Figure 6)

Statistical Analysis: Significant effects were observed for time (p < 0.001), group (p = 0.006), and time-group interaction (p < 0.001).

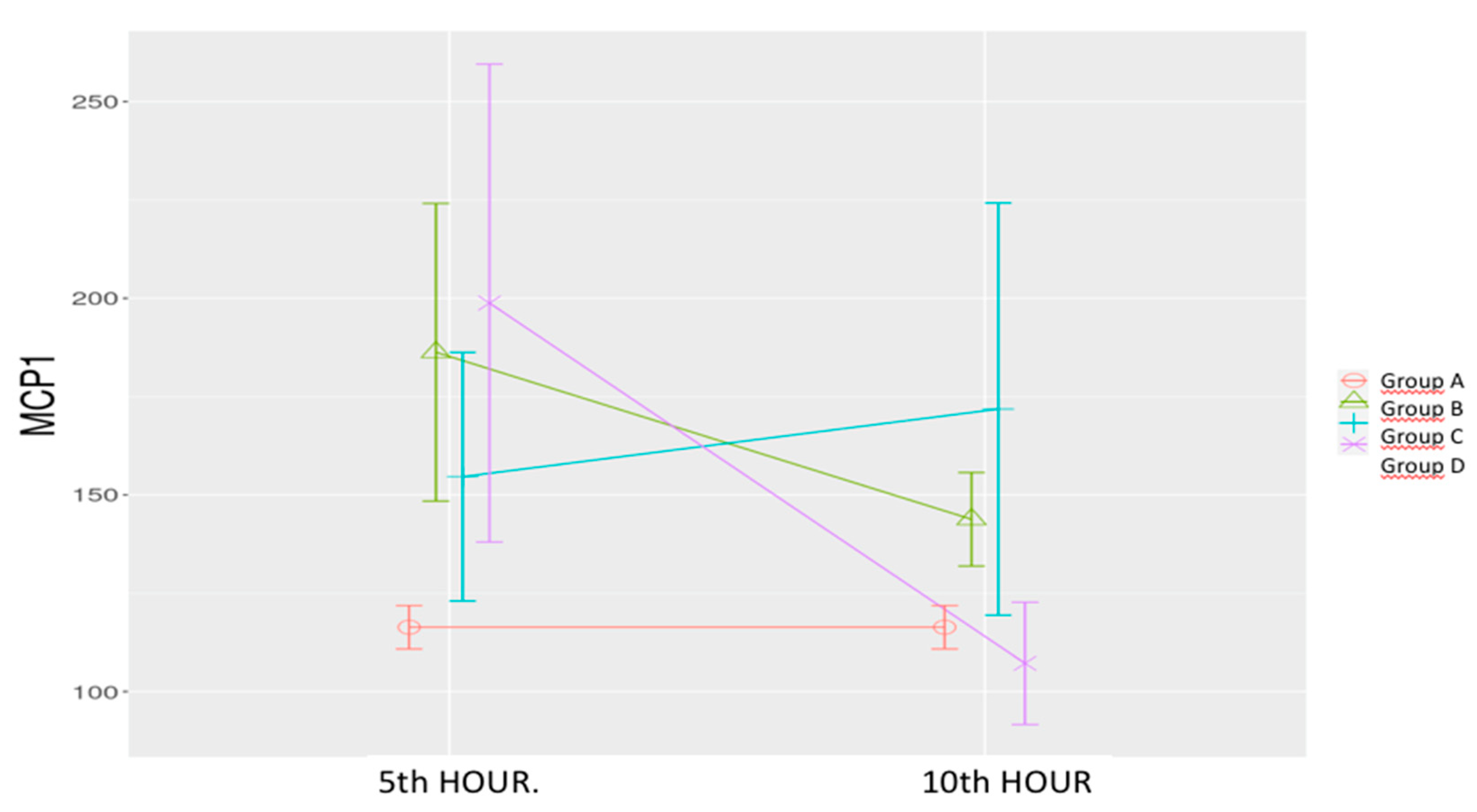

Sepsis Control Group (B): MCP-1 levels increased significantly at the 5th hour compared to the sham group, followed by a nonsignificant increase at the 10th hour.

Low-Dose Levosimendan (C): MCP-1 levels were significantly higher at the 5th and 10th hours compared to the sham group.

High-Dose Levosimendan (D): A significant increase was observed at the 5

th hour compared to the sham group, followed by a significant reduction at the 10

th hour lower than the sham group. (

Table 1,

Figure 7). Significant effects were observed for time (p = 0.006), group (p = 0.004), and time-group interaction (p = 0.002).

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates that levosimendan exerts a time- and dose-dependent modulatory effect on cytokine responses in experimental sepsis, with higher doses effectively suppressing the inflammatory response. The most substantial improvements observed in the high-dose levosimendan group, supports the hypothesis of a dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effect.

The results also demonstrate that, levosimendan treatment resulted in cytokine responses which differed according to the dose of levosimendan as well as the properties of each cytokine. Despite an early-phase increase in certain cytokine levels such as IL-17 and IL-6, a higher dose of levosimendan is more effective in reducing cytokine levels, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP-1. These findings highlight the potential need for optimized dosing strategies in clinical settings.

The LPS model of sepsis is widely used in research to simulate the inflammatory response seen in human sepsis. LPS, a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, triggers a systemic inflammatory response by activating immune cells, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This immune cascade closely resembles the cytokine storm and organ damage observed in sepsis. the LPS model remains highly relevant in experimental sepsis research for studying inflammation-focused treatments and cytokine modulation, providing critical insights that can guide therapeutic strategies [

18].

In experimental sepsis, each cytokine follows a distinct timeline in blood circulation, typically peaking and declining at different points after sepsis induction. In this study each cytokine showed a unique response timeline, reflecting the sequential nature of immune signaling in sepsis [

10]. TNF-α peaked early, aligning with its known role as an initial inflammatory mediator. TNF-α is one of the earliest cytokines to rise, usually peaking within 1-2 hours after sepsis onset often returning to baseline within 4-6 hours post-induction [

4]. IL-6, associated with sustaining inflammation, responded in the later phase well to high-dose levosimendan. IL-6 generally peaks around 4-6 hours after sepsis induction, and may remain elevated longer than TNF-α, sometimes up to 12-24 hours or even days in severe cases [

19].

MCP-1 chemotactic effects contribute to prolonged immune cell recruitment, maintaining inflammation in later stages of sepsis., decreased significantly with treatment, suggesting a reduction in inflammatory cell infiltration [

5,

20]. MCP-1 levels often increase moderately in the early phase but peak slightly later, around 6-12 hours which can remain elevated for an extended period, particularly if inflammation persists, sometimes up to 24 hours or more. IL-17A tends to peak later than the other cytokines, generally around 12-24 hours after sepsis initiation. As a late-phase cytokine, IL-17 amplifies inflammatory signaling, contributing to tissue damage and sustained immune activation in prolonged sepsis [

8].

Our findings are in agreement with multiple studies investigating the anti-inflammatory effects of levosimendan in various models of sepsis and systemic inflammation. Wang et al. [

21] demonstrated that levosimendan reduced TNF-α and IL-6 levels in septic mice, mitigating acute lung injury—a major complication of sepsis. Levosimendan demonstrated a strong ability to mitigate the inflammatory cascade associated with acute lung injury by reducing cytokine levels, which are primary markers of the immune response in sepsis. This study aligns with the present studies’ findings, particularly in the observed reductions in TNF-α and IL-6. The consistency across different animal models (mice and rats) suggests that levosimendan’s anti-inflammatory effects may be generalizable in sepsis-induced inflammation. Zager et al. [

22] reported a significant decrease in TNF-α and MCP-1, two cytokines involved in the inflammatory and chemotactic response of immune cells levels following levosimendan administration in a rat sepsis model, reinforcing its potential role in reducing systemic inflammation. The study highlighted levosimendan’s potential as a modulator of sepsis-induced inflammation, focusing on MCP-1’s role in recruiting immune cells to the site of infection, thus reducing inflammatory burden. Their findings closely support the present study’s results, where levosimendan administration, in higher doses, significantly lowered the MCP-1 to be similar to the sham levels. This suggests that levosimendan might help in reducing immune cell recruitment, thereby limiting tissue damage in sepsis. In another rat study, Sakaguchi et al. [

23] found that high-dose levosimendan had the most pronounced effects on lowering TNF-α and IL-1β levels in sepsis, further confirming our dose-dependent observations. They administered levosimendan at various dosages and found that high doses of the drug effectively lowered TNF-α levels at early time points. The study showed a dose-dependent response in which higher doses of levosimendan had more pronounced effects on lowering early cytokine levels, especially TNF-α. On the other hand in our study, our results showed that TNF-α decreased significantly with low dose levosimendan as well as the high dose. The anti-inflammatory action was most evident within the first few hours, which they hypothesized could be due to levosimendan’s rapid vasodilatory and cellular protective effect. This study’s dose-dependent results are consistent with the current findings, where a higher dose of Levosimendan led to significant reductions in TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels. Higher dosing may be crucial to achieving optimal anti-inflammatory effects in early sepsis treatment. Krychtiuk et al. [

24] provided evidence that levosimendan sustains reductions in IL-6 and IL-8 beyond the acute phase, suggesting potential long-term benefits in inflammatory conditions. They found that levosimendan could sustainably reduce IL-6 and IL-8 over extended periods, which has implications for chronic inflammation in severe conditions like sepsis. The study demonstrated a long-term anti-inflammatory effect of levosimendan, reducing IL-6 and IL-8 levels beyond the immediate administration phase. This suggests that levosimendan may have lasting benefits in suppressing inflammation, even in ongoing conditions. Our findings show that, compared to the sham group, non-significant increases in IL-8 levels were observed in both levosimendan groups at both time points, similar to the sepsis control group. However, a significant decrease was noted between the 5th and 10th hours in the high-dose group. It should be noted that the study duration may have been limited in fully assessing the effects of levosimendan on IL-8 levels.

Meng et al. [

25] highlighted the importance of IL-17 in sepsis progression and showed that IL-17 blockade improved survival outcomes. By neutralizing IL-17, they observed enhanced barrier integrity in tissues and a decrease in mortality. They also found that reducing IL-17 helped maintain tissue integrity and reduced harmful immune responses. Both low-dose and high-dose levosimendan led to a significant increase in IL-17 levels at the 5

th hour compared to both the sham and sepsis control groups. By the 10

th hour, levels significantly decreased, aligning with those of the sham group. The early-phase increase in IL-17 levels induced by levosimendan may be attributed to its dual effect, as suggested in some studies [

8].

Ateş et al. [

26] observed that levosimendan effectively reduced IL-1 and IL-6 levels in a blunt chest trauma model, further supporting its anti-inflammatory properties in conditions beyond sepsis. They administered both low and high doses of levosimendan and found that IL-1 and IL-6 levels were significantly reduced, particularly at higher doses. The results indicated that levosimendan’s anti-inflammatory effects extend beyond sepsis to trauma-induced inflammation. Higher doses of levosimendan were more effective in reducing cytokines associated with injury responses. This study supports the present research, where higher doses of levosimendan effectively reduced IL-1 and IL-6 in septic rats. The results suggest that levosimendan’s anti-inflammatory action may be applicable across various conditions, making it a versatile option for controlling cytokine storms in different inflammatory states. Together with the previous information, our results support the anti-inflammatory effects of levosimendan, particularly in its ability to reduce distinct pro-inflammatory cytokines. The consistency in findings across different models and inflammatory conditions emphasizes the drug’s therapeutic potential in managing sepsis and other cytokine-mediated inflammatory diseases.

Despite the promising findings, several limitations must be acknowledged. First the study assessed cytokine levels and clinical outcomes within the first 10 hours of sepsis induction. A longer observation period would be necessary to evaluate the sustained effects of levosimendan and its impact on long-term survival. Second, while we demonstrated systemic anti-inflammatory effects, we did not include histopathological examinations to assess organ protection, particularly in the lungs, kidneys, and liver. Third, although widely used, the LPS model does not fully mimic the complexity of human sepsis, which involves both pathogen-driven and host-mediated immune dysregulation. Finally, the study only evaluated the effects of a single dose of levosimendan. Investigating repeated or continuous dosing regimens may provide additional insights into its therapeutic potential.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion levosimendan demonstrates anti-inflammatory effects in a rat model of sepsis, with higher doses yielding greater reductions in especially early acting pro-inflammatory cytokines. Moreover, the levosimendan-treated groups exhibited a clinically significant reduction in MSS scores at the 10th hour, with the high-dose group showing the most substantial improvement. Our findings suggest that levosimendan may serve as a potential adjunct therapy for sepsis by modulating the immune response and mitigating systemic inflammation. However, despite promising experimental results, translating cytokine-targeting therapies from murine models to clinical settings remains a significant challenge due to the complexity of immune interactions in human sepsis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.D.E., A.D. and I.D.; methodology, E.D.E., A.U and I.D.; software, M.E.; validation, A.D., E.D.E. and M.E.; investigation, E.D.E., A.U., D.O.E and I.D.; resources, A.U. and A.D; data curation, I.D and D.O.E.; writing—original draft preparation, E.D.E; writing—review and editing, E.D.E., A.D., D.O.E. and I.D.; supervision, A.D. and M.E; funding acquisition, A.D. and M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Scientific Research Projects Directorate (BAP) of Selcuk University, grant number 221-220-30.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Experiments Ethics Committee of Selcuk University (36-30.09.2022)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated as part of this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin-1-beta |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| L-8 |

Interleukin-8 |

| IL-17 |

Interleukin-17 |

| MCP-1 |

Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

References

- Vincent, J.L.; Marshall, J.C.; Namendys-Silva, S.A.; François, B.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Lipman, J.; et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: The Intensive Care Over Nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.; Gerlach, H.; Vogelmann, T.; Preissing, F.; Stiefel, J.; Adam, D. Mortality in sepsis and septic shock in Europe, North America and Australia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dugar, S.; Choudhary, C.; Duggal, A. Sepsis and septic shock: Guideline-based management. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2020, 87, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaillon, J.M.; Adib-Conquy, M.; Fitting, C.; Adrie, C.; Payen, D. Cytokine cascades in sepsis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 35, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock, H.W.; Wedel, A.; Schraut, W.; Strobel, M.; Schlüter, C.; Wendelgass, P.; et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP-1) in the cytokine network of sepsis: A mediator of chemotaxis and activation of immune cells. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 25, 856–862. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima, K.; Yang, D.; Oppenheim, J.J. Interleukin-8: An evolving chemokine. Cytokine 2022, 153, 155828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; et al. IL-27 aggravates acute hepatic injury by promoting macrophage M1 polarization to induce Caspase-11 mediated pyroptosis in vitro and in vivo. Cytokine 2025, 188, 156881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cua, D.J.; Tato, C.M. Innate IL-17-producing cells: The sentinels of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, E.K.; et al. Fucosylated haptoglobin promotes inflammation via Mincle in sepsis: An observational study. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.J.; Seymour, C.W.; Rosengart, M.R. Current murine models of sepsis. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) 2016, 17, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Nicolás, M.Á.; Lázaro, A. Induction of sepsis in a rat model by the cecal ligation and puncture technique: Application for the study of experimental acute renal failure. Methods Cell Biol. 2025, 192, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotchkiss, R.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of IL-7 in critically ill COVID-19 patients. JCI Insight 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lannemyr, L.; Ricksten, S.E.; Rundqvist, B.; Andersson, B.; Bartfay, S.E.; Bragadottir, G. Levosimendan reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines and improves renal perfusion in patients with acute heart failure after cardiac surgery. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 308. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, J.; Bouzada, M.; Fernandez, A.L.; Caruezo, V.; Taboada, M.; Rodriguez, J.; et al. Hemodynamic and anti-inflammatory effects of levosimendan in patients with advanced heart failure. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2006, 59, 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/63/oj (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. Available online: https://arriveguidelines.org/arrive–guidelines (accessed on 20 April 2025). Available online: https://arriveguidelines.org/arrive-guidelines (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Sulzbacher, M.M.; Sulzbacher, L.M.; Passos, F.R.; et al. Adapted Murine Sepsis Score: Improving the research in experimental sepsis mouse model. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5700853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rittirsch, D.; Hoesel, L.M.; Ward, P.A. The disconnect between animal models of sepsis and human sepsis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 112, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, R.C.; Grodzin, C.J.; Balk, R.A. Sepsis: A new hypothesis for pathogenesis of the disease process. Chest 1997, 112, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Anshita, D.; Ravichandiran, V. MCP-1: Function, regulation, and involvement in disease. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 101 (Pt B), 107598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, S.; Fan, C.; Ge, D.; Yao, X.; et al. Levosimendan mitigates acute lung injury in sepsis through inhibition of NF-κB pathway in rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 7, 847–852. [Google Scholar]

- Zager, R.A.; Johnson, A.C.; Hanson, S.Y.; Lund, S. Levosimendan suppresses cytokine levels and protects against acute kidney injury in a rodent sepsis model. J. Crit. Care 2015, 30, 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi, T.; Sumiyama, F.; Kotsuka, M.; Hatta, M.; Yoshida, T.; Hayashi, M.; Kaibori, M.; Sekimoto, M. Levosimendan increases survival in a D-galactosamine and lipopolysaccharide rat model. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krychtiuk, K.A.; Kazemzadeh-Narbat, M.; Haider, T.; Lichtenauer, M.; Nickl, S.; Lenz, M.; et al. Sustained inflammation reduction with levosimendan in inflammatory conditions. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 278, 276–283. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M.; Hu, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. The protective effect of IL-17A neutralization on sepsis-induced lung injury in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 59, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ateş, İ.; Bulut, M.; Kılıç, F.; Gökmen, Z. Extended inflammation control in trauma models using levosimendan. Turk. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2019, 25, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Murine Sepsis Scores (MSS) of Sham, Sepsis Control, Low-dose Levosimendan and High-dose Levosimendan groups. *p<0.05 compared to Sham, ^p<0.05 compared to 5th hour. Ψp<0.05 compared to Sepsis Control.

Figure 1.

Murine Sepsis Scores (MSS) of Sham, Sepsis Control, Low-dose Levosimendan and High-dose Levosimendan groups. *p<0.05 compared to Sham, ^p<0.05 compared to 5th hour. Ψp<0.05 compared to Sepsis Control.

Figure 2.

Effects of levosimendan on TNF-α Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 2.

Effects of levosimendan on TNF-α Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 3.

Effects of levosimendan on IL-1β. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 3.

Effects of levosimendan on IL-1β. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 4.

Effects of levosimendan on IL-6. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 4.

Effects of levosimendan on IL-6. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 5.

Effects of levosimendan on IL-8. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 5.

Effects of levosimendan on IL-8. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 6.

Effects of levosimendan on IL-17. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 6.

Effects of levosimendan on IL-17. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 7.

Effects of levosimendan on MCP-1. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Figure 7.

Effects of levosimendan on MCP-1. Values are mean ± SD (ng/mL). Each group (n=8). Red: Sham (group A), Green: Sepsis (group B), Blue: low-dose levosimendan (group C), Purple: high-dose levosimendan (group D).

Table 1.

Cytokine levels of each group.

Table 1.

Cytokine levels of each group.

Cytokine

[ng/mL] |

Sham

A |

Sepsis

Control

5th hour

B |

Sepsis

Control

10th hour

B |

Low-Dose

Levosimendan

5th hour

C |

Low-Dose

Levosimendan

10th hour

C |

High-Dose

Levosimendan

5th hour

D |

High-Dose

Levosimendan

10th hour

D |

| TNF-α |

129.46 ± 10.14 |

212.53 ± 54.28* |

210.27 ± 78.44* |

196.58 ± 19.0 |

114.78 ± 63.75^Ψ

|

223.20 ± 43.28*

|

125.42 ± 20.98Ψ

|

| IL-1β |

11.56 ± 0.32 |

13.06 ± 0.97 |

13.82 ± 1.19*

|

14.83 ± 1.79*^

|

13.18 ± 1.58*Ψ

|

13.61 ± 1.65*

|

11.84 ± 0.52^Ψ

|

| IL-6 |

3.71 ± 0.21 |

4.29 ± 1.24 |

4.60 ±0.22* |

5.13± 1.11*

|

4.32 ±1.21 |

5.87 ± 1.13^*

|

3.78 ± 0.81Ψ

|

| IL-8 |

200.37 ± 7.22 |

205.99 ± 20.95 |

218.40 ± 32.37 |

218.90 ± 25.15 |

229.50 ± 24.34 |

229.27 ± 36.31 |

195.32±33.10Ψ

|

| IL-17 |

97.99 ± 9.83 |

117.55 ± 27.47 |

121.33 ± 25.59 |

159.93 ± 28.64*^

|

103.43 ± 21.39Ψ

|

168.19 ± 30.22*^

|

106.30±14.86Ψ

|

| MCP-1 |

116.34 ± 6.17 |

186.26 ± 45.25*

|

143.79 ± 14.21Ψ

|

154.63 ± 37.8* |

171.82 ± 20.51*

|

198.77 ± 72.66*

|

107.16 ± 18.57Ψ

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).