1. Introduction

Sepsis is a clinical condition resulting in organ failure and tissue damage stemming from an exaggerated inflammatory response of the immune system to any infection in the body[

1]. Sepsis is a serious condition that can lead to multi-organ failure and even death[

2]. There are approximately 50 million sepsis cases and 10 million sepsis-related deaths in the world each year[

1]. The main cause of death from sepsis is the result of organ failure. The most important organ failure caused by sepsis and the most common cause of mortality is the result of inflammation and tissue damage in the lungs[

3]. The cytokine storm resulting from sepsis and disruption of the lung microvascular barrier lead to inflammation and oxidative stress in the lungs, resulting in acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)[

4]. Mortality due to ALI or ARDS is very high, constituting one-third of sepsis-related deaths[

1]. Mortality of ALI and ARDS due to sepsis is higher than that of other causes[

3]. Despite all the advances in diagnosis and treatment, there is no effective and specific treatment method developed for ALI and ARDS. The treatments currently used in ALI and ARDS include respiratory and fluid support, mechanical ventilation in the supine position, and treatment of the infection[

5]. An important way to reduce mortality and morbidity due to sepsis is to treat or prevent lung damage caused by sepsis. Therefore, it is of great importance to develop preventive and therapeutic agents against sepsis-related lung injury. There are studies in this respect in the literature. However, an effective preventive and therapeutic agent that can be used in clinical practice has not been discovered yet.

Punica granatum L. (pomegranate, PG) is a fruit that is well known for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-cancer, anti-microbial, and anti-parasitic properties due to its high polyphenolic content. It is frequently consumed as a fruit, fruit juice, and wine[

6]. Studies are showing that PG exerts anti-inflammatory effects in asthma and various respiratory diseases as well as lipopolysaccharide-induced ALI and peritonitis[

7,

8,

9]. The ratio of polyphenols and flavonoids in the content of PG differs in the fruit parts. Studies have shown that PG peel, which constitutes approximately 60% of the total fruit weight, is richer in polyphenols and flavonoids compared to fruit grains[

10]. At the same time, literature studies show that bark extract has the highest anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity [

11]. In addition, punicalagin and ellagic acid, the main components of PG peel, have been shown to have strong anti-proliferative activities[

6]. In a study comparing the antioxidant contents of the peels of PG, grape, apple, and mocha fruits, the highest antioxidant activity and phenolic content were found in the PG peel [

12]. Literature studies with various parts of PG fruit show that PG peel has richer polyphenolic content and higher antioxidant capacity than fruit grains [

13].

Amifostine (S-2-3 amino-propyl-amino-ethyl-phosphoro-thioic acid; WR-2721) is an inactive phosphorothioate that is phosphorylated to the active thiol metabolite WR-1065 in tissues [

14]. Amifostine scavenges free oxygen radicals (ROS), accelerates DNA repair, and suppresses inflammation through NF-kB modulation, making it important as a cytoprotective agent [

15]. It is known that amifostine has a protective effect by reducing the accumulation of proteins and cells in the alveoli and ROS production in ventilator-induced lung injury[

16]. There are also studies in the literature in which amifostine exhibits protective effects in acute kidney injury caused by sepsis [

17].

The lung is one of the first tissues affected by organ failure in sepsis [

18]. Although the underlying mechanism has not been fully elucidated, pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, increased free oxygen radicals and lipid peroxidation rate, depletion of antioxidants, and disruption of energy and oxidative balance as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction cause damage to lung tissue[

19]. During lung damage, the coagulation system is activated and contributes to inflammation[

1]. The activities of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which degrade extracellular matrix proteins, have been associated with the cytokine storm in sepsis and tissue damage by increasing the infiltration of monocytes into the tissue [

20]. In addition, it has been suggested that increased MMP levels in the early period in response to inflammation impair blood circulation in tissue[

5]. This study aimed to investigate the effects of two different doses of PG peel extract, and amifostine in CLP-induced sepsis-related acute lung injury in rats.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

The study utilized a cohort of 50 male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, each with an average weight of 350±25 grams. The animals received treatment by the guidelines specified in the National Research Council's Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The animals were housed in conventional plastic enclosures with a floor covered with sawdust, maintained at a temperature of 21-22ºC and a humidity level of 55±10%. The lighting conditions were carefully regulated, with a 12-hour cycle of alternating darkness and light, maintained consistently throughout the study. The provision of unrestricted access to standard feed and tap water was permitted. The experimental protocol received approval from the Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University Experimental Animals Local Ethics Committee (2020/31).

2.2. Experimental Study Design

The participants were randomly allocated into five groups, each consisting of 10 rats. Group 1 was designated as the healthy control group (C) and was administered a 0.9% NaCl (saline) solution via oral gavage for ten days. The remaining three groups were subjected to the Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP) procedure. Group 2 administered the positive control (sepsis) without the administration of any medication [

21]. Group 3 was administered amifostin at a dosage of 200mg/kg intraperitoneally 15 minutes before the development of sepsis using the cecal ligation and puncture method (CLP) [

17]. Groups 4 and 5 were subjected to oral administration of PG bark extract at dosages of 250 and 500 mg/kg/day, respectively. This administration was carried out for a total of ten doses, once daily for nine days, with a time interval of 30 minutes before the induction of sepsis [

22].

2.3. Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP)-Induced Sepsis Model

The method of inducing sepsis in rats utilized in this study was the CLP (cecal ligation and puncture) technique, as previously outlined by Rittirsch D. et al. [

21]. All surgical procedures were conducted in a sterile environment. The rats were administered anesthesia with the injection of ketamine HCL at a dosage of 100 mg/kg and xylazine HCL at a dosage of 10 mg/kg. A surgical procedure involved creating an incision measuring around 2.5-3 cm in length along the midline of the abdomen. The internal organs and cecum were dissected from the tiny incision, and subsequently, the cecum was ligated using a 3/0 silk suture positioned distal to the ileocecal valve. Consistent with prior research, a pair of perforations were made at a location further away from the cecum, and the contents of the cecum were then exposed to the peritoneum [

17]. Following the administration of 1% lidocaine for analgesic purposes, the lesion was then treated by employing two layers of sterile silk 4/0 sutures for closure. The termination of the experiment occurred 16 hours after the completion of the pertinent processes [

23]. Upon the conclusion of the experiment, the rats were subjected to euthanasia through the administration of a high-dose anesthetic. A fraction of the pulmonary tissue was preserved at a temperature of -80ºC to be utilized for biochemical investigations. The remaining portion was immersed in a solution of neutral formalin with a concentration of 10% for subsequent histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations.

2.4. Production of Pomegranate Peel Extract

The PG peel samples were subjected to air drying at an ambient temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and thereafter transported to the laboratory to analyze polar constituents by the utilization of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

2.4. HPLC Analyses and Quantification

The plant material was subjected to mechanical grinding using a laboratory mill to create a uniform powder. Samples weighing approximately 0.1 g, with an accuracy of 0.0001 g, were subjected to extraction in 10 mL of methanol solutions with concentrations of 50%, 80%, and 100%. The extraction process was carried out using ultrasonication at a temperature of 40°C for 60 minutes in an ultrasonic bath. The extracts underwent filtration using a membrane filter with a pore size of 0.22 mm (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). They were subsequently stored in a refrigerator at a temperature of 4°C until the analysis was conducted. The drying and extraction procedures were conducted under conditions of reduced light exposure. The separation of phenolic acids was conducted using a reversed-phase C18 (5 mm, 250 mm X 4.0 mm) column in a Shimadzu LC-2030C-3D high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) instrument equipped with a photodiode array (PDA) detector. The binary gradient elution technique was employed to identify the respective substances.

The dual gradient elution technique was employed for the identification of the respective substances. The mobile phase A was prepared by acidifying water with 0.2% phosphoric acid to serve as eluent A, while water containing 0.3% acetonitrile was used as eluent B. The mobile phase C used for ursolic acid, comprises 100% methanol, whereas mobile phase D is composed of 100% acetonitrile. The elution profile was employed in the following manner: a 10% B composition was used for the duration of 0-10 minutes, followed by a transition to 25% B from 10-30 minutes, subsequently increasing to 60% B from 30-38 minutes, maintaining 60% B from 38-45 minutes, and finally returning to 10% B from 45-45.01 minutes. The column was operated at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min under a temperature of 25°C. The volume of the injected extract was 10 ml. The calibration of components was conducted by measuring their response at specific wavelengths of 203 nm, 280 nm, 320 nm, and 360 nm. This measurement was performed using standard solutions with concentrations of 5 ppm, 10 ppm, 20 ppm, 50 ppm, 100 ppm, and 200 ppm.

Table 1 presents the results of the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) examination conducted on the peel extract of PG. The obtained data exhibited a profile that closely resembled the information reported in the existing literature [

13].

2.5. Drugs & Chemicals

Before the sacrification and CLP procedure, animals were anesthetized by administering Ketamine HCL ((Ketalar®, Pfizer İlaçları Ltd. Şti, Istanbul, Turkey) and Xylazine HCL ((Rompun®, Bayer, USA). Amifostine (Ethyol 500 mg vial, Medimmun Pharma BV, Nijmegen, Nederland).

2.6. Histopathological Analysis

Lung tissue obtained from rats was reduced to a volume of 1.5 cm and samples were prepared for subsequent histological analysis. Lung tissue samples were immersed in a 10% phosphate-neutral-buffered formalin solution (Sigma Aldrich, Germany) for 36 hours. After the fixation process, standard histological follow-up procedures were conducted, which included dehydration using a series of increasing ethanol concentrations (Merck KGAa, Darmstadt, Germany), mordanting with xylol (Merck KGAa, Darmstadt, Germany), embedding in soft paraffin (Merck KGAa, Darmstadt, Germany), and finally applying hard paraffin blocking step (Merck KGAa, Darmstadt, Germany). The lung tissue slides of 4-5µm in thickness were obtained from the paraffin blocks using a rotary microtome. These slides were subsequently stained with Harris hematoxylin and Eosin G (H&E, Merck KGAa, Darmstadt, Germany).

2.7. Immunohistochemical (IHC) Analysis

To determine the fibrosis in the interstitial areas and the increase in the extracellular matrix in the rat lung tissue, MMP-2 (rabbit polyclonal, ab86607, Abcam, UK) and MMP-9 primary antibodies and MMP-9 (rabbit polyclonal, ab76003, Abcam, UK) together with secondary antibodies (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (HRP), ab205718, Abcam, UK) kits were used. Preparate of the lung tissue was waiting with primary antibody for 60 minutes. Next step lung tissue slides were waiting for secondary antibody for 60 minutes and eventually, the antigen retrieval procedure using the Leica IHC/ISH (Leica Biosystems, Leica, Germany) device. Sections were stained with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (LeicaltraviewDAB, Leica Biosystems, Germany) and Harris hematoxylin (Merck, Germany).

2.8. Semi-Quantitative Analysis

The lung tissue damage score (LDS) developed by Matute-Bello et al. was utilized to quantify alveolar and interstitial neutrophil deposition, hyaline membranes, alveolar debris deposition, and alveolar septal wall thickness in the lung (

Table 2), [

27]. Two histopathologists who were unaware of the research groups examined 35 distinct locations in each piece of lung tissue. The analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9 positive (as shown in

Table 3) was conducted by two histopathologists who were blinded to the study. A total of 35 distinct locations were randomly chosen within each section, and the immunohistochemical (IHC) positivity was assessed in a cumulative total of 210 distinct places within each group.

2.9. Statistically Analysis

The statistical tool used for calculating all data in the analysis was SPSS 18.0 (IBM, Armonk, NJ, USA). The normal distribution was established by the utilization of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The One-Way ANOVA and Bonferroni test were employed as post hoc tests to ascertain differences, given that the test results conform to the normal distribution. The values were represented by the mean and interquartile ranges spanning from the 25th to the 75th percentile. Given that the data obtained from the test did not adhere to a normal distribution, statistical analyses were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni adjustments to ascertain any significant differences. The values were represented in terms of the mean and standard deviation. A significance level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance, and p-values below this threshold were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Histopathological Findings

Types 1 and 2 of pneumocytes in the alveolar sac were normal in the lung tissue of the control group (

Figure 1a,b,

Table 4, LHDS: 1 (1-1). Sections of the CLP group showed diffuse inflammation in the alveolar and interstitial areas and alveolar septal wall along with an increase in thickness of the structures. In addition, hyaline membrane structures were present (

Figure 1c,d;

Table 4, LHDS: 8(8-9). We observed a decrease in alveolar and interstitial inflammation and alveolar-septal wall thickness in the sections belonging to the CLP+Amf group (

Figure 1e,f;

Table 4, LHDS: 3(2-4). We found that alveolar and interstitial inflammation and alveolar-septal wall thickness decreased in sections belonging to CLP+PG250 and CLP+PG500 groups. In addition, normal type 1 and type 2 pneumocytes were seen in alveolar sacs in respiratory bronchioles in both groups (

Figure 1g,h;

Table 4, LHDS: 2(1-2),

Figure 1i-j;

Table 4, LHDS: 1(1-2) ), respectively).

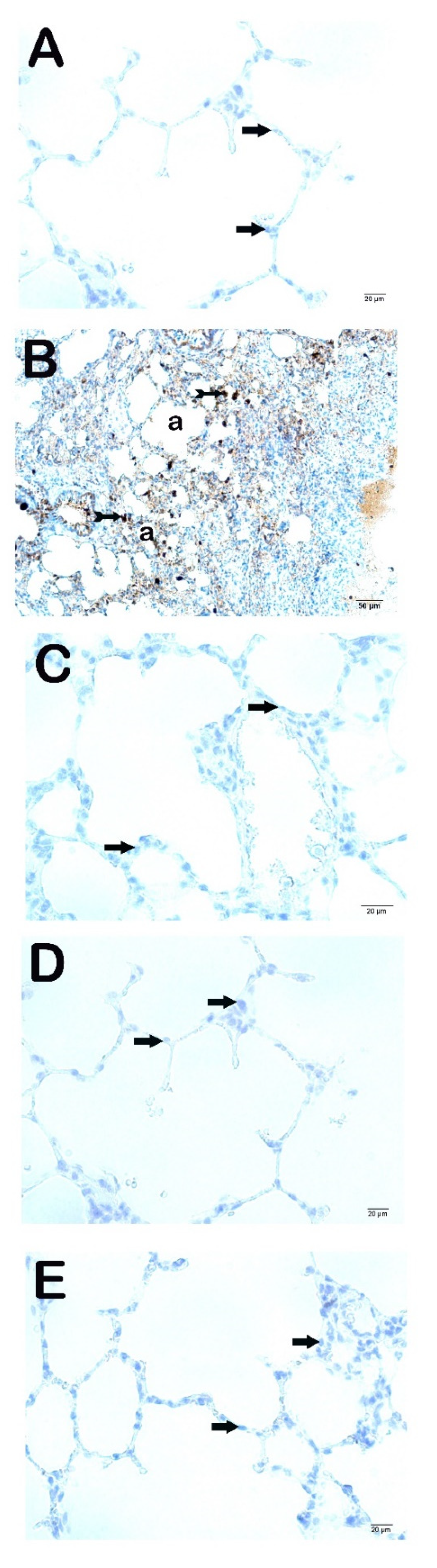

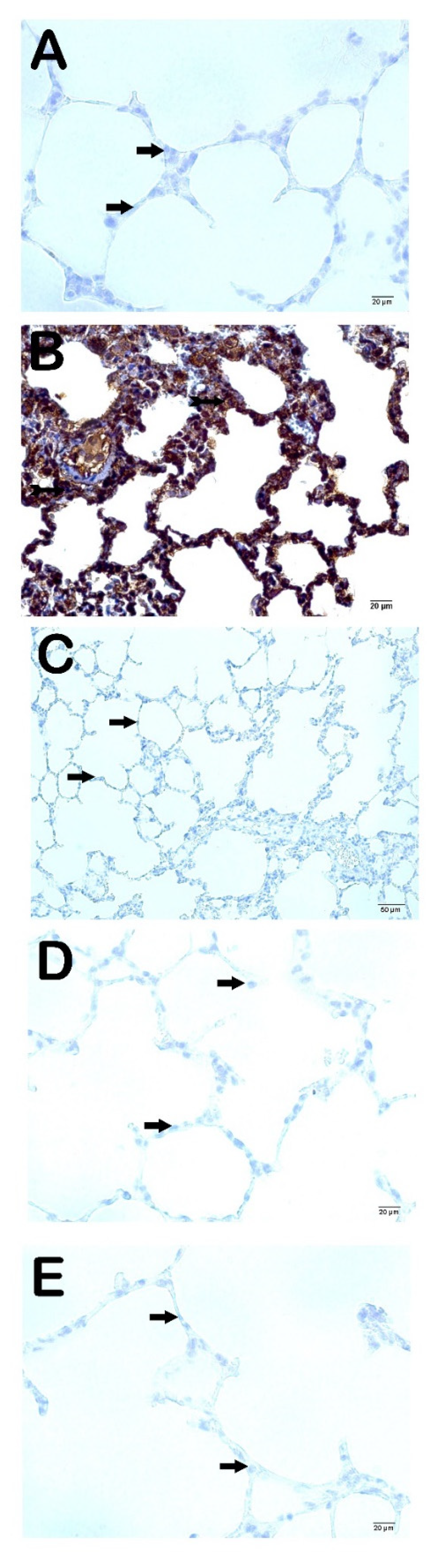

3.2. Immuno-Histochemical Findings

When we analyzed the fibrosis in the interstitial areas and the increase in the extracellular matrix using the IHC method; we observed that the cells showing MMP-2 and MMP-9 positivity in the CLP group were significantly higher compared to the control group (

Figure 2a and Figure 3a;

Table 5; p=0.001; p=0.001; respectively) in contrast to the CLP+Amf group (

Figure 2b and Figure 3b;

Table 5; p=0.001; p=0.001; respectively). Similarly, MMP2- and MMP-9 positivity significantly decreased in the CLP-PG250 and CLP+PG500 groups compared to the CLP group ((

Figure 2c and Figure 3c;

Table 5; p=0.001; p=0.001; respectively), (

Figure 2d and Figure 3d;

Table 5; p=0.001; p=0.001; respectively)).

3.3. Semi-Quantitative Results

We observed that the alveolar-septal wall thickness, which was 10.14±2.14 µm in the control group, increased by 28.41±7.88 µm in the CLP group (

Figure 1a–d;

Table 6; p=0.001). This decreased to 15.04±6.12 µm in the CLP+Amf group (

Figure 1e,f;

Table 6; p=0.001). The alveolar-septal wall thicknesses decreased to 12.47±2.85µm in the CLP+PG250 group (

Figure 1g,h;

Table 6; p=0.001) and to 11.89±3.87µm in the CLP+PG500 group (

Figure 1i,j;

Table 6; p=0.001). Alveolar-septal wall thicknesses in all groups treated with amifostine and PG peel extract were significantly reduced compared to the CLP group and were similar to the control group.

4. Discussion

In this study, the effects of two different doses of pomegranate peel extract on lung tissue in a rat model of sepsis induced by the cecal-ligation puncture were examined immunohistochemically. This was compared to amifostine, a thiol compound. The increase in alveolar septum thickness and hyaline membranes accompanying the inflammation in the alveolar and interstitial areas, observed in the lung tissue of the sepsis group, supports the functioning of our model. The lungs are the first organs to be affected and most vulnerable to sepsis [

7,

9,

19]. Sepsis-related acute lung injury is characterized by tissue damage resulting from intense neutrophil infiltration into the epithelium, accumulation of exudate in the alveoli, and hyaline membranes, and loss of alveolar-capillary membrane integrity[

1]. Acute lung injury due to sepsis is more severe and fatal than acute lung injury due to pneumonia[

12]. In addition, inflammation is more difficult to resolve in sepsis-related lung injury[

3]. This is probably due to the complex and multifactorial biological mechanism of sepsis. Although the underlying mechanism of acute lung injury due to sepsis is not fully understood, severe inflammation and oxidative stress resulting from the increase of cytokines such as TNF-a, IL-1β, and IL-6 and deterioration of the microvascular structure of the lung are the main causes[

4]. Therefore, suppression of inflammation and reduction of oxidative stress should be the primary goals to prevent sepsis-related lung injury [

6,

29].

PG is a fruit that has come to the forefront with its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties throughout history and has been studied extensively[

10,

30]. Literature studies with various parts of PG fruit show that PG peel has richer polyphenolic content and higher antioxidant capacity than fruit grains[

13]. This is one of the main reasons why we preferred PG peel extract as a preventive and therapeutic agent in our study. In addition, the peel constitutes about half of the total fruit volume, and the evaluation of the skin as an antioxidant and cytoprotective agent may have important economic relevance[

12].

The decreased inflammation in the lung alveoli of the groups in which PG peel extract was applied in our histopathological examination can be explained by the suppression of cytokine levels by the PG peel extract. Although there is no statistically significant difference, the protective effect seems to increase as the dose of PG peel extract increases. In our histopathological analysis, alveolar and interstitial inflammations were not significantly reduced in the group treated with PG peel at 500 mg/kg compared to the PG peel at 250 mg/kg application group; alveolar septum thickness was found to be similar to the control group; and hyaline membranes were not observed. These findings are consistent with the results of studies in which PG peel was used as a therapeutic agent in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced sepsis-related lung injury and LPS-induced lung injury in diabetic rats [

9,

22]. In the literature, there are studies in which PG is used as a therapeutic agent in respiratory diseases such as asthma, lung cancer, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[

11]. There are numerous studies in the literature showing that the PG peel extract has an antimicrobial effect [

12]. It has been reported that especially the methanolic extract of PG peel shows antimicrobial properties and provides a great reduction in bacterial biofilm formation [

12,

29]. Our study is also a model of CLP-sepsis, and there is infection with polymicrobial agents. PG peel may also have protection with its antimicrobial properties. However, since we did not perform microbiological analyses in this study, we cannot comment on this issue. Literature data show that the methanolic extract of the bark has the most antioxidant and antimicrobial effects [

12].

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are enzymes that degrade extracellular matrix proteins and play an important role in lung diseases[

20]. A few studies in the literature suggest that MMP-2 is derived from bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells and fibroblasts. MMP-9 is released from lymphocytes, neutrophils, and alveolar macrophages [

31]. The extracellular matrix-degrading effects of MMPs suggest that they play an important role in lung regeneration and fibrosis as an early response to injury[

5]. High levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in lung fibrosis and progression of fibrosis in mice with MMP-2 deficiency have been documented[

31]. MMPs also play an important role in sepsis by regulating the release and activity of cytokines, initiating the inflammatory response of leukocytes. It has also been shown that MMP-9 activates TNF-α[

20]. It is known that MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels increase in sepsis and show a positive correlation with the severity of the disease [

32,

33]. It has been found that MMP-9 levels are associated with disease activity and mortality in patients with COVID-19 disease hospitalized in the intensive care unit[

34]. Zheng et al. They observed that MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity increased in acute lung injury in mice administered LPS[

5]. In our study, immunohistochemical analysis of the lung tissue of rats in the sepsis group showed significantly higher MMP-2 and MMP-9 positivity compared to the other 4 groups. These results were consistent with those reported [

18,

35]. In our study, while MMP-2 positivity was not observed in both doses of PG peel extract and the amifostine group, mild MMP-9 positivity was observed only in the amifostine group. No MMP-9 positivity was observed in the groups treated with PG peel extract. The literature has different implications regarding MMPs whose levels increase in pathological processes[

20,

31,

32]. Data indicating that increased MMP levels exacerbate sepsis and inhibition of its release has a protective effect, as well as data showing that increased MMP is a defense mechanism against sepsis and its destruction exacerbates sepsis and sepsis-related death[

5,

20,

31,

32]. The reason for the decrease in MMP concentration in the groups treated with pomegranate peel and amifostine may be due to the decrease in lung damage.

Amifostine is a free radical scavenger that converts to active thiol compounds in tissue[

36,

37]. Its radio and chemoprotective effects are well known[

38,

39]. Its cytoprotective effect has been attributed to DNA repair, scavenging of free radicals, and modulation of NF-kB[

17]. The demonstration that amifostine reduces intra-alveolar inflammation and free oxygen radicals in ventilator-associated lung injury suggests that it will also protect against sepsis-induced lung injury[

16]. In our study, we think that PG peel extract and amifostine have a protective and curative effect on sepsis-related lung injury by decreasing the levels of MMPs responsible for tissue damage.

There are some limitations of this study. First of all, this study is an animal sepsis model and clinical studies are required to demonstrate relevancy. In addition, sepsis is often unpredictable in its clinical outcome involving or otherwise acute lung injury. Although the lungs are the first organ affected in sepsis, lung injury was evaluated in this study's acute phase of sepsis. It is not known whether the protective effects of PG peel extract and amifostine will continue in chronic processes and whether they can heal chronic damage. In addition, microbiological and molecular analyses could increase our knowledge about the properties of the antimicrobial mechanism of PG peel extract.

5. Conclusion

Pomegranate peel extract offered protection against sepsis-induced acute lung damage comparable to amifostine by inhibiting MMPs. However, considering the possible side effects of amifostine, the economic benefits of pomegranate peel extract, and its easy availability, it can be prioritized in terms of clinical use as a protective agent. Future animal models and clinical studies that evaluate chronic processes, including timing, dose range, and molecular mechanisms, are needed for both agents to be used in sepsis-related lung injury.

Author Contributions

KS, SSA, IB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software FM, TM, LT: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. TM, LT, and AT: Visualization, Investigation. Supervision.: KS, OFD: Software, Validation.: KS, FM, OFD, ZAC: Writing- Reviewing and Editing. All authors take public responsibility for the content of the work submitted for review. The authors contributed to the study design, conduction of the experiments, analyses of the results, and drafting of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the University of Recep Tayyip Erdogan University for the grant Project “Effect of Punica Granatum Pericarp and Amifostine on Cecal-Ligation-Puncture-Induced Sepsis-Associated Acute Lung Injury in Rats” (Approval number: 2022).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. The data will be available upon reasonable request (contact persons: kazim.sahin@erdogan.edu.tr).

Statement of Ethics

This experimental study was performed with approval from the Recep Tayyip Erdogan University Animal Research Ethics Committee (Rize, Turkey) (Approval Number: 2020/31). Informed consent is not necessary because this is an experimental animal study.

Acknowledgments

The Recep Tayyip Erdogan University Development Foundation provided funding for the open-access publishing of this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

References

- Li, W.; Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Abudou, H.; Wang, H.; Cai, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fan, H. Classic Signaling Pathways in Alveolar Injury and Repair Involved in Sepsis-Induced ALI/ARDS: New Research Progress and Prospect. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Liao, Y. Gut-Lung Crosstalk in Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. Pulmonary Innate Immune Response Determines the Outcome of Inflammation During Pneumonia and Sepsis-Associated Acute Lung Injury. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, Y.; Satoh-Takayama, N.; Kawamoto, E.; Ito, A.; Gaowa, A.; Park, E.J.; Imai, H.; Shimaoka, M. The Role of Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Regulation of Immune Homeostasis in Sepsis-Mediated Lung Inflammation. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, H.; Hu, F.; Li, Q.; Jiang, L.; Su, Y.; Peng, Q.; et al. Lidocaine Alleviates Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury in Mice by Suppressing Tissue Factor and Matrix Metalloproteinase-2/9. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, H.; Ślȩzak, A.; Szyjka, A.; Oszmiański, J.; Gasiorowski, K. Antioxidant and Cancer Chemopreventive Activities of Cistus and Pomegranate Polyphenols. Acta Pol. Pharm. - Drug Res. 2017, 74, 688–698. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, A.J.M.C.R.; Gonçalves, J.S.; Dourado, Á.W.A.; De Sousa, E.M.; Brito, N.M.; Silva, L.K.; Batista, M.C.A.; De Sá, J.C.; Monteiro, C.R.A.V.; Fernandes, E.S.; et al. Punica Granatum L. Leaf Extract Attenuates Lung Inflammation in Mice with Acute Lung Injury. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.F.F.; Garreto, D. V.; Da Silva, M.C.P.; Fortes, T.S.; De Oliveira, R.B.; Nascimento, F.R.F.; Da Costa, F.B.; Grisotto, M.A.G.; Nicolete, R. Therapeutic Potential of Biodegradable Microparticles Containing Punica Granatum L. (Pomegranate) in Murine Model of Asthma. Inflamm. Res. 2013, 62, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.J.M.C.R.; Mendes, A.R.S.; Neves, M.D.F. de J.; Prado, C.M.; Bittencourt-Mernak, M.I.; Santana, F.P.R.; Lago, J.H.G.; de Sá, J.C.; da Rocha, C.Q.; de Sousa, E.M.; et al. Galloyl-Hexahydroxydiphenoyl (HHDP)-Glucose Isolated from Punica Granatum L. Leaves Protects against Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Acute Lung Injury in BALB/c Mice. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, V.; Continella, A.; Drago, C.; Gentile, A.; Malfa, S. La; Leotta, C.G.; Pulvirenti, L.; Ruberto, G.; Pitari, G.M.; Siracusa, L. Secondary Metabolic Profiles and Anticancer Actions from Fruit Extracts of Immature Pomegranates. PLoS One 2021, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.B.; Bhandary, Y.P. Therapeutic Properties of Punica Granatum L (Pomegranate) and Its Applications in Lung-Based Diseases: A Detailed Review. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubhi, N.H.; Al-Quwaie, D.A.; Alrefaei, G.I.; Alharbi, M.; Binothman, N.; Aljadani, M.; Qahl, S.H.; Jaber, F.A.; Huwaikem, M.; Sheikh, H.M.; et al. Pomegranate Pomace Extract with Antioxidant, Anticancer, Antimicrobial, and Antiviral Activity Enhances the Quality of Strawberry-Yogurt Smoothie. Bioengineering 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, J.; Lakshmanapermalsamy, P.; Illuri, R.; Bhosle, D.; Sangli, G.; Mundkinajeddu, D. In Vitro Evaluation of Antioxidant Potential of Isolated Compounds and Various Extracts of Peel of Punica Granatum L. Pharmacognosy Res. 2018, 10, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougioukas, I.; Didilis, V.; Emigholz, J.; Waldmann-Beushausen, R.; Stojanovic, T.; Mühlfeld, C.; Schoendube, F.A.; Danner, B.C. The Effect of Amifostine on Lung Ischaemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 23, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercantepe, F.; Mercantepe, T.; Topcu, A.; Yilmaz, A.; Tumkaya, L. Correction to: Protective Effects of Amifostine, Curcumin and Melatonin against Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury (Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, (2018), 391, 9, (915-931), 10.1007/S00210-018-1514-4). Naunyn. Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 2019, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Murley, J.; Grdina, D.; Birukuva, A.; Birukuv, K. Induction of Cellular Antioxidant Defense by Amifostine Improves Ventilator Induced Lung Injury. Crit Care Med. 2011, 39, 2711–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcik, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Tumkaya, L.; Mercantepe, T.; Atak, M.; Topcu, A.; Uydu, H.A.; Mercantepe, F. The Nephroprotective Effect of Amifostine in a Cecal Ligation-Induced Sepsis Model in Terms of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 9144–9156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, G.; Tamer, S.; Yorulmaz, H.; Mutlu, S.; Olgac, V.; Aksu, A.; Caglar, N.B.; Özkök, E. Melatonin Pretreatment Modulates Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, YKL-40, and Matrix Metalloproteinases in Endotoxemic Rat Lung Tissue. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 247, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaria, J.P.; Moretta, L.; Alves-Filho, J.C.; Hirsch, E. PI3K Signaling in Mechanisms and Treatments of Pulmonary Fibrosis Following Sepsis and Acute Lung Injury. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mao, Y.F.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, D.F.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.F.; Dong, W.W.; Zhu, X.Y.; Ding, N.; Jiang, L.; et al. Upregulation of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Protects against Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury via Promoting the Release of Soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittirsch, D.; Huber-Lang, M.; Flierl, M.; Ward, P. Immunodesign of Experimental Sepsis by Cecal Ligation and Puncture. Nat Protoc 2009, 4, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugan, R.; Un, H.; Yayla, M.; Civelek, M.S.; Kilicle PA Nar Kabuğu Ekstresinin Sıçanlarda Diyabetik Şartlarda Sepsis Ile İndüklenen Akciğer Hasarına Karşı Etkileri The Effects of Pomegranate Peel Extract Against Sepsis Induced Lung Damage Under Diabetic Conditions in Rats. 2020, 47, 678–686. [CrossRef]

- Cinar, I.; Sirin, B.; Aydin, P.; Toktay, E.; Cadirci, E.; Halici, I.; Halici, Z. Ameliorative Effect of Gossypin against Acute Lung Injury in Experimental Sepsis Model of Rats. Life Sci. 2019, 221, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, D.B.; Gemelli, T.; De Andrade, R.B.; Campos, A.G.; Dutra-Filho, C.S.; Wannmacher, C.M.D. Administration of Histidine to Female Rats Induces Changes in Oxidative Status in Cortex and Hippocampus of the Offspring. Neurochem. Res. 2012, 37, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for Lipid Peroxides in Animal Tissues by Thiobarbituric Acid Reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlak, J.; Lindsay, R.H. Estimation of Total, Protein-Bound, and Nonprotein Sulfhydryl Groups in Tissue with Ellman’s Reagent. Anal. Biochem. 1968, 25, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matute-Bello, G.; Downey, G.; Moore, B.B.; Groshong, S.D.; Matthay, M.A.; Slutsky, A.S.; Kuebler, W.M. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report: Features and Measurements of Experimental Acute Lung Injury in Animals. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011, 44, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.R.; Lin, Q.; Liang, F.Q.; Xie, T. Dexmedetomidine Attenuates Lung Injury by Promoting Mitochondrial Fission and Oxygen Consumption. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, S.; Beigoli, S.; Khazdair, M.R.; Amin, F.; Boskabady, M.H. Experimental and Clinical Studies on the Effects of Natural Products on Noxious Agents-Induced Lung Disorders, a Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; McClees, S.F.; Afaq, F. Pomegranate for Prevention and Treatment of Cancer: An Update. Molecules 2017, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, T.; Maus, R.; Stolper, J.; Tort Tarrés, M.; Brandenberger, C.; Wedekind, D.; Jonigk, D.; Welte, T.; Gauldie, J.; Kolb, M.; et al. Role of Matrix Metalloprotease-2 and MMP-9 in Experimental Lung Fibrosis in Mice. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordakieva, G.; Budge-Wolfram, R.M.; Budinsky, A.C.; Nikfardjam, M.; Delle-Karth, G.; Girard, A.; Godnic-Cvar, J.; Crevenna, R.; Heinz, G. Plasma MMP-9 and TIMP-1 Levels on ICU Admission Are Associated with 30-Day Survival. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2021, 133, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirrone, F.; Pastore, C.; Mazzola, S.; Albertini, M. In Vivo Study of the Behaviour of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9) in Mechanical, Hypoxic and Septic-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Vet. Res. Commun. 2009, 33, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila-mesquita, C.D.; Couto, A.E.S.; Campos, L.C.B.; Vasconcelos, T.F.; Sbragia, L.; Joviliano, E.E.; Evora, P.R.; Carvalho, R. De MMP-2 and MMP-9 Levels in Plasma Are Altered and Associated with Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, K.; Kundu, P.; Banerjee, A.; Reiter, R.J.; Swarnakar, S. Hydrogen Peroxide-Mediated Downregulation of Matrix Metalloprotease-2 in Indomethacin-Induced Acute Gastric Ulceration Is Blocked by Melatonin and Other Antioxidants. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.B.; Stockerl-Goldstein, K.E.; Klein, J.; Murphy, J.; Blume, K.G.; Dansey, R.; Martinez, C.; Matthes, S.; Nieto, Y. A Randomized Trial of Amifostine and Carmustine-Containing Chemotherapy to Assess Lung-Protective Effects. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004, 10, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.; Karakoc, Y.; Tumkaya, L.; Mercantepe, T.; Sevinc, H.; Yilmaz, A.; Yılmaz Rakıcı, S. The Protective Effects of Red Ginseng and Amifostine against Renal Damage Caused by Ionizing Radiation. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2022, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercantepe, F.; Mercantepe, T.; Topcu, A.; Yılmaz, A.; Tumkaya, L. Protective Effects of Amifostine, Curcumin, and Melatonin against Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Topcu, A.; Mercantepe, F.; Rakici, S.; Tumkaya, L.; Uydu, H.A.; Mercantepe, T. An Investigation of the Effects of N-Acetylcysteine on Radiotherapy-Induced Testicular Injury in Rats. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 2019, 392, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).