1. Introduction

Lumpy skin disease (LSD) is a contagious disease of cattle and water buffaloes. The disease is caused by the lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV), which belongs to the family

Poxviridae under the genus

Capripoxvirus [

1]. The first case of LSD was reported in 1929 in Zambia [

2]. LSD outbreaks have been recognized in various areas of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Lebanon, Israel, Iran, and Turkey. Outbreaks of LSD have been reported in Armenia, Greece, Russia, Azerbaijan, Albania, Serbia, Bulgaria, Kosovo, and Montenegro since 2015 [3, 4]. In 2016, LSD outbreaks were reported in many Southeastern regions of Europe [

5]. The disease has also been reported in many Asian countries, e.g., Vietnam, Thailand, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. In India, the disease caused the death of more than 155,000 cattle. In Pakistan, the first outbreak of LSD was confirmed in a cattle farm located in Karachi (Sindh Province of Pakistan) in 2022 [

6]. It is believed that the disease came from India because of the shared borders. The LSD outbreaks occur in other neighboring countries, including Malaysia and Thailand. There is a serious concern about the transboundary transmission of LSD due to the movement of livestock from these countries to Pakistan [

7].

The LSD causes huge economic losses worldwide. After an incubation period of 4 to 12 days, there is the onset of fever (40-41.5˚C), which lasts for one to three days. Other signs include increased salivation, nasal discharge, lacrimation, inflamed lymph nodes, depression, restricted movement, emaciation, and anorexia. Skin nodules appear within 1-2 days and progressively become hard-textured and necrotic. After two to three weeks, necrotic nodules slough off, leaving a hole in the skin, which may attract flies, leading to myiasis and bacterial infections. Bulls excrete the virus through their semen for a long time and become infertile temporarily or permanently. Normally, the mortality rate is low (1-5%) [

8]. Due to its economic importance, the World Organization for Animal Health has listed LSD as a notifiable illness.

The production of cattle and buffalo in Pakistan plays a pivotal role in the lives of people and the national economy. According to the Economic Survey of Pakistan, 2023-2024, more than eight million people are involved in rearing dairy animals (primarily buffaloes and cattle). They earn 35-40% of their income from livestock and contribute meaningfully to their livelihoods. Pakistan is the third leading milk producer in the world with 57.5 million and 46.3 million cattle and buffaloes, respectively. The gross milk production in Pakistan is 70 million tons, comprising 26 million tons of cow milk and 42 million tons of buffalo milk [

9].

Lumpy skin disease (LSD) is primarily transmitted through direct contact with infected animals, while insect vectors such as mosquitoes and flies further facilitate its spread. The movement of infected livestock, along with environmental factors like high humidity and rainfall, also contributes to outbreaks. A lack of vaccination remains a significant risk factor. Immunization against LSD remains the actual mode to reduce disease outbreaks.. Many countries have successfully used vaccines to prevent LSDV infection [

10]. Restricted animal movement and quarantine, along with ring vaccination, are recommended as control measures [

3]. Modified live vaccines are commercially available [

11], which were obtained by blind passages in embryonated chicken eggs via the chorioallantoic membrane route or in cell cultures. In some countries, heterologous vaccination using goat pox virus (GTPV) or sheep pox virus (SPPV) is also practiced. Unfortunately, side effects of live attenuated vaccines include severe swelling at the site of inoculation, high rise in temperature, loss of hide, and a drop in milk production [

12]. Often, live vaccines produce generalized LSD in a mild form known as the Neethling Disease.

Because of the rapid spread of LSD across borders, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) advocates the use of an effective and harmless inactivated vaccine to control LSD outbreaks in disease-free countries. Inactivated vaccines against LSD have many advantages over live vaccines, including safety, no ill effect on milk production, and non-transfer of virus to healthy unvaccinated animals on the same farm [

13]. In addition, the virus in an inactivated vaccine does not replicate, thereby losing its ability to revert to virulence. Thus, inactivated vaccines against LSD appear to be a viable option to provide adequate immunity and avoid severe swelling, high temperature, and loss of hide and milk production. A disadvantage of inactivated vaccines is that an adjuvant is required to enhance their efficacy. The objectives of the study were to isolate a local strain of LSDV, develop an inactivated oil-adjuvanted vaccine, and test the immune response and protective efficacy of this experimental vaccine in rabbits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection:

A total of 60 scab samples were collected from suspected cases in Sahiwal cows (Bos indicus) in 20 different dairy farms located in two cattle colonies (217/RB and 225/RB) in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Scabs were collected from cows showing high fever, excessive salivation, bilateral epiphora, skin edema, and enlarged lymph nodules. Before sample collection, the area was cleaned, and the hair was clipped. The scabs were labeled and placed in a sterile jar containing a virus transport medium. All samples were transported to the Cell Culture Laboratory (CCL), Institute of Microbiology (IOM), University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

2.2. Isolation of LSDV in Embryonated Chicken Eggs:

The scabs were cut into small pieces using sterile scissors and blades. Using a pestle and mortar, the scabs were homogenized in 10 mL of sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS) containing streptomycin sulfate (1mg/mL), benzyl penicillin (1000 IU/mL), and amphotericin B (100 μL/mL). The suspension was centrifuged at 4200

×g for 30 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected in sterile vials, followed by filtration with a 45mM filter. The filtrate was inoculated into embryonated chicken eggs via the chorioallantoic (CAM) route [

14]. After incubation at 37 °C, the CAM from all eggs was checked for pock lesions (dark opaque necropsied large areas about 3- 5 mm in diameter). The CAM was homogenized in PBS, followed by centrifugation at 4200

×g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Aliquots of supernatant, containing the isolated virus from field samples, were stored at -80

oC until further use.

2.3. DNA extraction and PCR:

The DNA was extracted from CAM supernatant by using the Gene Jet Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, Lithuania) at the Research and Development Division (R&D), Veterinary Research Institute (VRI), Lahore, Government of Punjab, Pakistan. The primers used to amplify targeted gene segments of LSDV (P32 and GPCR genes); P32 is an envelope protein gene, while the GPCR (G-protein coupled receptors) gene plays a significant part in host interaction and facilitating immune invasion.

This was followed by PCR to confirm the presence of the virus. Thermal conditions for amplification of the P32 gene included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds. Annealing was then performed at 58°C for 30 seconds, and the extension step took place at 72°C for 45 seconds. The final elongation occurred at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR thermal conditions for amplification of the GPCR gene were initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute. Annealing was carried out at 48°C for 1 minute, and the extension step occurred at 72°C for 1 minute. The final elongation was done at 72°C for 10 minutes. The PCR products obtained were separated based on their size and charge using a 1.2% agarose gel and a DNA ladder of 100 base pairs (bp). Electric current was provided to the DNA loaded in the gel. The negatively charged DNA fragments traveled through the gel towards the positive side of the gel electrophoresis apparatus.

Table 1.

Primers used to amplify targeted gene segments of LSDV.

Table 1.

Primers used to amplify targeted gene segments of LSDV.

| Target Gene |

Primer Sequence (5′ - 3′) |

Amplicon Size (bp) |

Reference |

| P32-F |

TTTCCTGATTTTTCTTACTAT |

192 |

[15, 16] |

| P32-R |

AAATTATATACGTAAATAAC |

| GPCR-F |

TGAAAAATTAATCCATTCTTCTAAACA |

684 |

[17] |

| GPCR-R |

TCATGTATTTTATAACGATAATGCAAA |

2.4. Adaptation of LSDV Isolates in Cell Cultures:

Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells were used to propagate and titrate the LSDV grown in embryonated chicken eggs. The cells were grown at 37°C with 5% CO

2 in Glasgow Minimum Essential Medium (GMEM) enriched with 5% (v/v) Tryptose Phosphate Broth (TPB) and 10% (v/v) Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS). The cultures were kept under these conditions until they reached approximately 90% confluency, at which point they were used for LSDV propagation. The cell monolayer was infected with LSDV and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO

2. The monolayers were examined daily for the appearance of virus-induced cytopathic effects (CPE). The CPE appeared on the 5

th day post-infection and peaked at 09-10 days. Three blind passages were given, and the 4

th passage material was used for vaccine production. The confirmed LSDV was typically isolated and quantified (TCID

50; tissue culture infective dose) by using primary culture. LSDV infects Madin-Darby bovine Kidney (MDBK) cells and forms multifocal areas of hyperplastic cells [

8]. The confirmed LSDV was adapted in Madin-Darby Bovine Kidney (MDBK) cell lines for the purpose of vaccination preparation. The virus titer was calculated by using the Median Tissue Culture Infectious Dose assay [

18].

2.5. Vaccine Preparation:

The virus at passage level 4 was inactivated by using 0.03/mL of Binary Ethyleneimine (BEI) [13, 19]. After incubating for 24 hours at 37

0C, sodium thiosulfate was added @ 10 mL/100 mL. This was followed by re-incubation for 24 hours at 37

0C. To this inactivated virus, Montanide ISA-50 V2 adjuvant (

SEPPIC,

France) @ 50%, thiomersal 0.003%, and Penicillin 4000000IU @ 0.1 mL/100mL were added. The sterility of the vaccine was checked by inoculation in thioglycolate broth followed by incubation at 35

0C for 14 days. Sabouraud dextrose agar was used to check for the growth of fungi. Nutrient agar, nutrient broth, and MacConkey’s agar were also used to check for bacterial growth [

20].

2.6. Challenge Study:

To evaluate the protective efficacy of the inactivated oil adjuvanted LSD vaccine, 24 rabbits of mixed gender (12-14 weeks of age, weighing 2.7-3.0 Kg) were randomly allocated to three different groups (groups A, B, and C; eight rabbits per group). Upon arrival, the rabbits underwent a seven-day acclimation period, during which their general health was monitored daily before the trial commenced. Throughout the study, the rabbits were fed Epol’s rabbit chow and had unlimited access to clean water. Rabbits in group A were inoculated intramuscularly with the vaccine. Rabbits in group B were vaccinated subcutaneously with a commercially available live attenuated vaccine. Group C served as the negative control group. All animals were monitored daily for 21 days for the appearance of any clinical signs. The booster dose of the vaccine was administered on day 22, and the trial ended on day 42.

2.7. Serological Testing by ELISA:

An indirect ELISA test was performed to detect antibodies in sera against LSDV induced by vaccination against LSD in rabbits [13, 18].

Serum samples were analyzed for LSDV antibodies using the ID Screen® Capripox Double Antigen ELISA (ID.vet, Grabels, France), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm. The sample-to-positive (S/P) ratio was calculated as:S/P% = [(OD_sample – OD_negative) / (OD_positive – OD_negative)] × 100Samples with S/P% < 30% were classified as negative, while those ≥ 30% were considered positive [

21]

.

The differences between antibody titers obtained after vaccination were analyzed statistically by using a complete randomized design (CRD), and means of antibody titers were compared by using a post hoc technique, i.e., Dunnett’s test.

3. Results

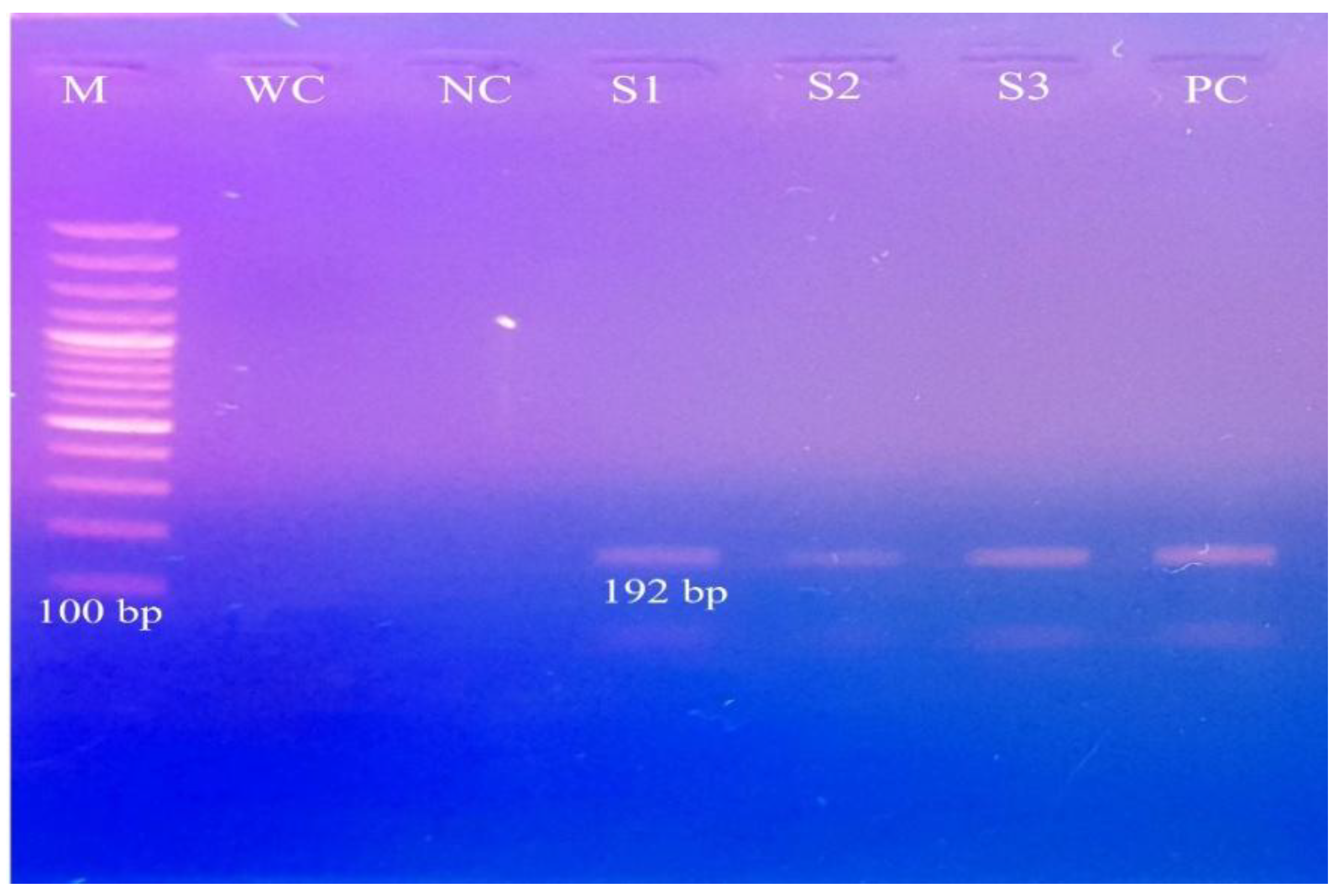

3.1. Isolation and Molecular Confirmation of LSDV:

The LSDV isolated in this study was confirmed by conventional PCR using P32 and GPCR genes (

Figure 1 and Figure 2). The gene sequence data were permanently archived in the NCBI GenBank database under accession number

PQ720422 for the P32 gene. The nucleotide sequence of the partial coding sequence of the P32 gene is as follows:

>PQ720422.1 Lumpy skin disease virus isolate CFSD1047 envelope protein (P32) gene, partial cds

GGTTTCATTTTTTGGTATATTTGATATTAGTATAATAGGAGCACTTATTATTTTATTTATTATAATAATGATAATTTTTGATTTGAATTCTAAATTACTATGGTTTTTAGCAGGTATGTTATTTACGTATATAATTTA

The gene sequencing analysis to confirm the GPCR gene was performed at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul), USA. The sequence data were permanently archived in the NCBI GenBank database under Accession numbers: PV288761- PV288762 and BankIt ID: 2901800. The nucleotide sequence of the partial coding sequence of the GPCR gene is as follows:

>PV288761.1 Lumpy skin disease virus strain Neethling CFSD 1047 G protein-coupled chemokine receptor gene, partial cds

TTGAAAAATTAATCCATTCTTCTAAACAGTTTTTATGAACTATCTTAAATTCATTCTTGCAATTACAAAAGTTTGTACTTACATTATATTCATCTTTACAAATCCAACAATGAGTGTTGGTATTATCACTCCCTTCCATTTTTATAAAATATCATTATTTGTTGTTATTATTTTTTTATTTTTTATCCAATGCTAATACTACCAGCACTACTAGTGCTACGCAATCGTAAAAGCTTTTTAGTAAATTCTCTACTACAAAACGCATAAATTAGTGGATTAATAAAACAATGACATAGAGACACAATTTCAGCTACATGAACTGCAAGGTTGACAAATCGTAATGCCGTACATCCACTAAAAACATTTAACAAATACAACGATGAAACAAATACAGTTACACTAAATGGGAGTAAAAACAATACTGAACAGATAACAATCAAAAACACCATCTTTATGGCTTTCTTATTCTTTGTTTGCGAGGTTTTTAAAGTATTTAAGATTTTATAGTAACAATATAGCAAAATAATTAGCGGTATAATCATTCCAAATATGTTTATTTCAAAATTTATAAATAATTTCCAAATTTTTGCATTATCGTTATAAAATACATGAAA

>PV288762.1 Lumpy skin disease virus strain Neethling CFSD 1047 G protein-coupled chemokine receptor gene, partial cds

TTGAAAAATTAATCCATTCTTCTAAACAGTTTTTATGAACTATCTTAAATTCATTCTTGCAATTACAAAAGTTTGTACTTACATTATATTCATCTTTACAAATCCAACAATGAGTGTTGGTATTATCACTCCCTTCCATTTTTATAAAATATCATTATTTGTTGTTATTATTTTTTTATTTTTTATCCAATGCTAATACTACCAGCACTACTAGTGCTACGCAATCGTAAAAGCTTTTTAGTAAATTCTCTACTACAAAACGCATAAATTAGTGGATTAATAAAACAATGACATAGAGACACAATTTCAGCTACATGAACTGCAAGGTTGACAAATCGTAATGCCGTACATCCACTAAAAACATTTAACAAATACAACGATGAAACAAATACAGTTACACTAAATGGGAGTAAAAACAATACTGAACAGATAACAATCAAAAACACCATCTTTATGGCTTTCTTATTCTTTGTTTGCGAGGTTTTTAAAGTATTTAAGATTTTATAGTAACAATATAGCAAAATAATTAGCGGTATAATCATTCCAAATATGTTTATTTCAAAATTTATAAATAATTTCCAAATTTTTGCATTATCGTTATAAAATACATGAAA

Figure 2: Lumpy skin disease virus was confirmed by GPCR gene by using PCR assay (M: 100bp Marker, WC: Water Control, S1: Sample1, S2: Sample2, S3: Sample3, S4: Sample4, NC: Negative Control, PC: Positive Control)

3.2. Cell Culture Adaptation and Calculation of Virus Titers:

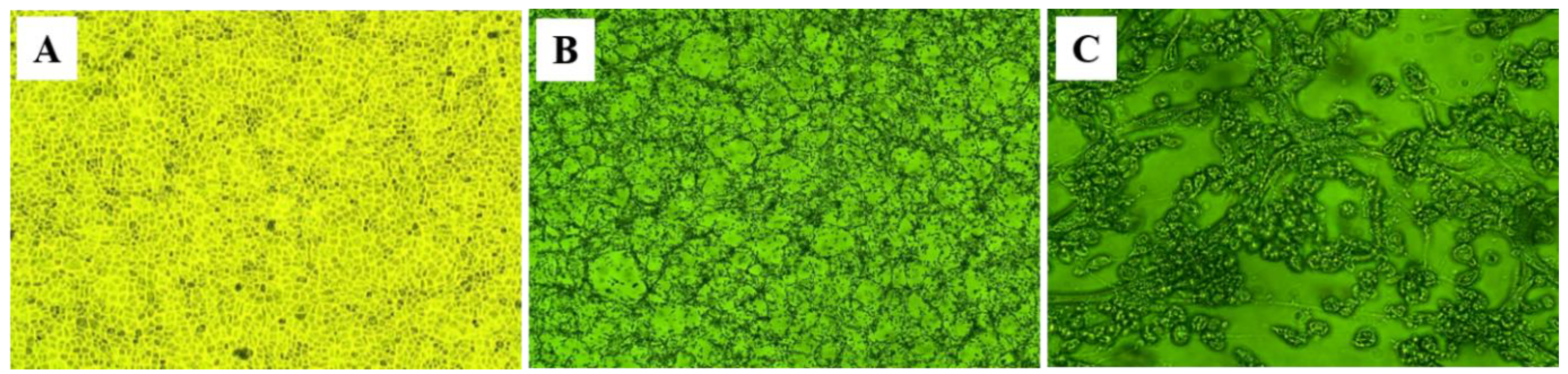

Molecularly confirmed LSDV was adapted to MDBK cells over four passages. Cells were cultured in GMEM with 5% TPB and 10% FBS at 37°C with 5% CO₂. At ~90% confluency, monolayers were infected with LSDV for propagation and titer assessment. At each passage, the virus was confirmed by PCR using P32 and GPCR genes. The virus titer were recorded as 107.0 TCID50 /mL.

Figure 3.

MDBK cells (A) Controlled, (B) Cytopathic effect (CPE) of LSDV on MDBK cells at 100X, (C) Cytopathic effect (CPE) of LSDV on MDBK cells at 400X.

Figure 3.

MDBK cells (A) Controlled, (B) Cytopathic effect (CPE) of LSDV on MDBK cells at 100X, (C) Cytopathic effect (CPE) of LSDV on MDBK cells at 400X.

3.3. Inactivation of Virus and Addition of Adjuvant:

The virus was inactivated by using Binary Ethyleneimine (BEI) [

13] followed by the addition of Montanide ISA-50 V2 adjuvant (

SEPPIC,

France). Sterility test was performed by using direct inoculation technique. Thiglycolate medium was used to check aerobic and anaerobic bacterial growth after incubating at 35

0C for 14 days, and Sabouraud dextrose agar was used to check the growth of fungus, Nutrient agar and Nutrient broth were used to check the different bacterial growth and MacConkey agar was used to check Gram negative bacterial growth [

20]. The vaccine was found to be free of bacterial and fungal contamination.

3.4. Challenge Study in Rabbits:

Vaccine efficacy (VE) was determined by the formula,

VE = 1- Relative Risk. The developed inactivated experimental oil adjuvanted vaccine demonstrated a VE of 86%.

3.5. Evaluation of Antibody Titers and Immune Response:

ELISA results were interpreted by using the formula: (OD sample – OD negative control) / (OD positive control – OD negative control) *100 = S/P ratio. Here, S is the difference between the sample and negative control ODs, and P is the difference between the positive and negative control ODs. A ratio less than 30% indicates a negative result, while a ratio of 30% or greater indicates a positive result. The antibody titers were assessed in three distinct groups: Group A (experimental inactivated oil-adjuvanted LSD vaccine), Group B (commercially available vaccine), and Group C (control group) at three different time points: day 0, day 22, and day 42.

In Group A, which received the experimental inactivated oil-adjuvanted LSD vaccine, the average antibody titers (S/P %) at day 0, day 22, and day 42 were 4.3, 71.5, and 166.6, respectively. These results indicate a clear increase in the immune response over time, with a significant rise in antibody levels between day 0 and day 42. The total mean antibody titers across all time points for Group A were 1333. In Group B, which was administered the commercially available vaccine, the S/P (%) values at day 0, day 22, and day 42 were 5.9, 93.8, and 210.1, respectively. Similarly, the antibody titers increased steadily over the study period, with a marked increase between day 22 and day 42. The overall mean antibody titers for Group B was 1681, indicating a strong immune response to the commercially available vaccine. In contrast, Group C, the control group that did not receive any vaccine, had consistently low antibody titers at day 0, day 22, and day 42, with S/P (%) values of 5.8, 6.3, and 6.0, respectively. These low values reflect a minimal immune response, consistent with the lack of vaccination. The total mean antibody titers for Group C was 48.

3.6. Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analysis was performed using Dunnett’s post-hoc test to compare mean antibody titers. The D-value calculation showed significant differences between the groups. The recorded differences between means were 1285 and 1633 in groups A and B, respectively, both were greater than the D-value (77.78), confirming that the vaccines induced a significant immune response compared to the control group. The standard deviations for Group A (40.30%) and Group B (47.55%) reflected moderate variability in immune responses, while Group C had a standard deviation of 0%, indicating no variability. These results clearly demonstrate the significant immune responses triggered by the vaccines, with no immune activity in the control group.

4. Discussion

Recent LSD outbreaks that occurred in Europe, the Middle East, and in Asia's central parts [

13] pose a serious threat to livestock farming, especially to cattle farming in Pakistan. Pakistan ranks as the third-largest milk producer globally. The cattle and buffalo farming sector in Pakistan is crucial for both the livelihoods of its people and the national economy. In fiscal year 2024, livestock contributed 60.84% to the agricultural sector and 14.63% to the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP). While LSD was once confined primarily to Africa, its recent spread to neighboring countries such as India, China, and Iran poses a serious threat to Pakistan's livestock sector. Given that Pakistan has the second-largest livestock population globally and an economy heavily reliant on agriculture, an LSD outbreak would have dire implications. The potential for LSD to cross borders from neighboring countries increases the risk to Pakistan's livestock industry.

The primary risks for LSD entering Pakistan include the uncontrolled movement of livestock across borders and insufficient measures to control the disease vectors. Effective management strategies are essential to mitigate these risks, including implementing strict quarantine protocols, controlling vector populations, and ensuring vaccination coverage for at-risk livestock. Currently, LSD has not been confirmed within Pakistan, but the country's geographic position makes it vulnerable. Government institutions are prepared to handle infectious diseases and support vaccination programs, but the financial strain of large-scale vaccination and control measures presents a challenge. The Livestock Department of Pakistan generally covers the cost of vaccines, but the economic situation may limit the extent of these measures. In light of Pakistan's border dynamics and its substantial livestock population, complete eradication of LSD may be difficult. Therefore, controlling the spread of the disease through vector management, regulating animal movements, and vaccinating livestock remains crucial. Addressing these challenges effectively is essential for safeguarding Pakistan's vital livestock sector while navigating the constraints imposed by a weakened economy [

22]. Veterinary vaccines are essential to safeguarding animal health, enhancing livestock productivity, and ensuring food safety and public health [

23].

Farmers are reluctant to purchase and inoculate these live attenuated vaccines to their animals. Inactivated vaccines are recognized for their safety, stability in tropical environments, and ability to be combined with other antigens to create polyvalent vaccines. They can also be used in disease-free regions without compromising their status. Additionally, these vaccines do not present the risk of the virus reverting to virulence or being transmitted between vaccinated individuals and others. The benefits of these vaccines are significant in countries at high risk of introducing LSD, particularly where there is a large cattle population plays a crucial role in the disease eradication [

13].

Until now, there has been no development or testing of an inactivated vaccine for LSD. However, recent research successfully tested an inactivated vaccine against sheep pox virus, which belongs to the same genus as the LSDV. The study found that the oil-adjuvanted vaccine provided complete protection against a virulent strain. Additionally, the antibody response was also found to be robust and enduring [

24].

Several molecular techniques are employed to detect LSDV, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), real-time PCR, and high-resolution melting (HRM) assays. These methods target various genomic regions to ensure precise identification and characterization of the virus. Notable genomic targets in molecular epidemiological studies of LSDV include genes encoding glycoproteins such as GPCR, RPO30, P32, and EEV. Analyzing these regions offers crucial insights into the virus's genetic evolution and dissemination [

25]. Top of FormBottom of Form

The effective control of LSD relies on accurate and timely diagnostic tools to confirm clinical cases. Various serological techniques have been used to detect LSDV, including the virus neutralization test (VNT), indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT), and ELISA. While these assays are generally reliable and suitable for large-scale screening, they often cannot distinguish between

Parapoxvirus and

Capripoxvirus. However, the commercially available ID Screen® Capripox double antigen ELISA kit can detect antibodies against

Capripoxviruses in serum without cross-reacting with

Parapoxviruses [

21]. To evaluate the antibody response during the field trial, the IDScreen® Capripox Double Antigen ELISA kit was employed. Serum samples were dispensed into 96-well plates pre-coated with purified Capripoxvirus antigen and incubated for 90 minutes at 21°C. After incubation, the wells were rinsed with a wash solution, and 100 μl of conjugate was added to each well. Following a 30-minute incubation at 21°C, the wells were washed again, and 100μL of Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate solution was applied. The plates were then incubated in the dark at 21°C for 15 minutes before stopping the reaction with a stop solution. Optical density readings were taken at 450 nm. Samples were classified as negative if the S/P ratio was less than 30% and as positive if the S/P ratio was 30% or greater [

13]. The rP32-based indirect ELISA effectively detected antibodies in vaccinated animals. Given the high risk of LSD in Kazakhstan and its economic impact, a reliable ELISA test is essential for animal health [

26].

This study was focused on developing and evaluating an experimental inactivated oil-adjuvanted vaccine for Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD) using locally isolated LSDV. A challenge study in rabbits assessed the vaccine’s protective efficacy and immune response through antibody titers. Three groups were involved: the experimental vaccine group, a commercially available vaccine group, and a control group.

The results demonstrated that both the experimental and commercial vaccines induced a strong immune response, with significant differences observed compared to the control group. Statistical analysis confirmed the significance of the results, highlighting the effectiveness of both vaccines in stimulating immune protection against LSD. The variability in immune responses was noted between the two vaccine groups, with the commercial vaccine showing more diverse responses compared to the experimental one. The control group exhibited no immune response, confirming that the observed effects were due to vaccination. Overall, the study supports the efficacy of the inactivated oil-adjuvanted vaccine in providing protection against LSD.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the experimental inactivated oil-adjuvanted vaccine for Lumpy skin disease (LSD) proved effective, showing good immune responses similar to the commercially available vaccine. Inactivated vaccines offer a harmless and reliable choice for large-scale vaccination, avoiding the hazards associated with live attenuated LSD vaccines. This makes the inactivated vaccine a promising solution to control LSD and diminish its economic influence.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: A.S. and M.S.M.; Experiments and procedures: A.S. and W.S.; Data collation, analysis, and interpretation: A.S., W.S., M.I.A., R.Z.A. and M.S.M.; Article writing: A.S.; Study supervision: M.S.M. and S.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Higher Education Commission of Pakistan supported this study through a research fellowship award (No. 1-8/HEC/HRD/2024/20622), enabling part of the research to be conducted at the University of Minnesota's College of Veterinary Medicine in the USA.

Data Availability Statement

Although data are not publicly available due to ethical considerations, they can be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota (USA), the Veterinary Research Institute, Lahore (Pakistan), and the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan for their generous support and contributions, which were instrumental in the successful execution of this research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Issimov, A.; Taylor, D.; Shalmenov, M.; Nurgaliyev, B.; Zhubantayev, I.; Abekeshev, N.; Kushaliyev, K.; Kereyev, A.; Kutumbetov, L.; Zhanabayev, A.; Zhakiyanova, Y.; White. P. Retention of lumpy skin disease virus in Stomoxys spp (Stomoxys calcitrans, Stomoxys sitiens, Stomoxys indica) following intrathoracic inoculation, Diptera: Muscidae. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0238210.

- Wainwright, S.; El-Idrissi, A.; Mattioli, R.; Tibbo, M.; Njeumi, F.; Raizman, F. Emergence of lumpy skin disease in the Eastern Mediterranean Basin countries. The FAO Emergency Prevention System (EMPRES) Watch 2013, 29, 1-6.

- Beard, P.M. Lumpy skin disease: A direct threat to Europe. Vet Rec. 2016, 178, 557–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasioudi, K.E.; Antoniou, S.E.; lliadou, P.; Sachpatzidis, A.; Plevraki, E.; Agianniotaki, E.I.; Fouki, C.; Mangana-Vougiouka, O.; Chondrokouki, E.; Dile, C. Emergence of lumpy skin disease in Greece, 2015. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2016, 63, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojkic, I.; Simic, I.; Kresic, N. Complete Genome Sequence of a Lumpy Skin Disease Virus Strain Isolated from the Skin of a Vaccinated Animal. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e00482–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rida, A.; Hafsa; Riaz, Z. Evaluation of antiviral potential of ivermectin against lumpy skin disease virus challenge in rabbits. CVJ. 2024, 4, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, S.; Sharma, B.; Shabir, S.; Akbar, H.; Venter, E. Lumpy skin disease is expanding its geographic range: A challenge for Asian livestock management and food security. Vet J. 2022, 279, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Chander, Y.; Kumar, R.; Khandelwal, N.; Riyesh, T.; Chaudhary, K. Isolation and characterization of lumpy skin disease virus from cattle in India. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0241022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anonymous. Pakistan Economic Survey 2023-24. Finance and Economic Affairs Division, Ministry of Finance, Goverenment of Pakistan, Islamabad, Pakistan.

- Rehman, S.; Abuzahra, M.; Wibisono, F.J.; Effendi, M. H.; Khan, M.H.; Ullah, S.; Abubakar, A.A.; Zaman, A.; Shah, M.K.; Malik, M.I.; Rahman, A.; Abbas, A.; Nadeem, M. Identification of Risk Factors and Vaccine Efficacy for Lumpy Skin Disease in Sidoarjo and Blitar Districts of East Java, Indonesia. IJVS. 2024, 13, 574–579. [Google Scholar]

- Tuppurainen, E.; Dietze, K.; Wolff, J.; Bergmann, H.; Beltran-Alcrudo, D.; Fahrion, A.; Lamien, C.E.; Busch, F.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Conraths, F.J.; De Clercq, K.; Hoffmann, B.; Knauf, S. Vaccines and vaccination against lumpy skin disease. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedekovic, T.; Simic, I.; Kresic, N.; Lojkic, I. Detection of lumpy skin disease virus in skin lesions, blood, nasal swabs, and milk following preventive vaccination. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 65, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, J.; Boumart, Z.; Daouam, S.; El-Arkam, A.; Bamouh, Z.; Jazouli, M.; Tadlaoui, K.O.; Fihri, O.F.; Gavrilov, B.; Harrak, M. Development and Evaluation of an Inactivated Lumpy Skin Disease Vaccine for Cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 245, 108689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, D.M.; Shehab, G.; Emran, R.; Hassanien, R.T.; Alagmy, G.N.; Hagag, N.M.; Abd-El-Moniem, M.I.I.; Habashi, A.R.; Ibraheem, E.M.; Shahein, M.A. Diagnosis of naturally occurring lumpy skin disease virus infection in cattle using virological, molecular, and immunohistopathological assays. Vet. World. 2021, 14, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.; Manaa, E.; Khater, H. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of lumpy skin disease in Egypt. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 79, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geletu, U.S.; Musa, A.A.; Usmael, M.A.; Keno, M.S. Molecular Detection and Isolation of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus during an Outbreak in West Hararghe Zone, Eastern Ethiopia. Vet. Med. Int. 2024, 2024, 9487970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, P.; Meki, I.K.; Maharjan, M.; Settypalli, B.K.; Manandhar, S.; Yadav, S.K.; Cattoli, G.; Lamien, C.E. Molecular Characterization of the 2020 Outbreak of Lumpy Skin Disease in Nepal. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsiela, M.S.; Naicker, L.; Dibakwane, V.S.; Ntombela, N.; Khoza, T.; Mokoena, N. Improved safety profile of inactivated Neethling strain of Lumpy Skin Disease Vaccine. Vaccines 2022, X 12, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; Michael, A.; Soliman, S.M.; Samir, S.S.; Daoud, A.M. Trials for preparation of inactivated sheep pox vaccine using binary ethyleneimine. EJI. 2003, 10, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Parveen, S.; Kaur, S.; David, S.A.W.; Kenney, J.L.; McCormick, W.M.; Gupta, R.K. Evaluation of growth based rapid microbiological methods for sterility testing of vaccines and other biological products. Vaccines 2011, 29, 8012–8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.; Din, M.B.; Rahman, M.M; Roy, M.; Rahman, A.; Rafe-Ush-Shan, S.M.; Chowdhury, M.S.R.; Hossain, H.; Alam, J.; Cho, H.S.; Hossain, M.M. Lumpy Skin Disease in Bangladesh: Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of LSD in Cattle. Int. J. Vet. Sci, 2024, 13, 896–902. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Y.R.; Ali, A.; Hussain, K.; Ijaz, M.; Rabbani, A.H.; Khan, R.L.; Abbas, S.N.; Aziz, M.U.; Ghaffar, A.; Sajid, H.A. A review: Surveillance of lumpy skin disease (LSD) a growing problem in Asia. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 158, 105050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Zulqarnain, A.; Aman, S.; Ullah, A.; Junaid, M.; Khalid, M.H.; Ali, Z.; Hussain, I.; Chishti, M.A.A. Innovation in vaccines for infectious diseases in pets and livestocks. USJAS. 2024, 8, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumart, Z.; Daouam, S.; Belkourati, I.; Rafi, L.; Tuppurainen, E.; Omari, K.; Tadlaoui; El Harrak, M. Comparative innocuity and efficacy of live and inactivated sheeppox vaccines. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badhy, S.C.; Chowdhury, M.G.A.; Settypalli, T.B.K.; Cattoli, G.; Lamien, C.E.; Fakir, M.A.U.; Akter, S.; Osmani, M.G.; Talukdar, F.; Begum, N.; Khan, I.A.; Rashid, M.B.; Sadekuzzaman, M. Molecular characterization of lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV) emerged in Bangladesh reveals unique genetic features compared to contemporary field strains. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tursunov, K.; Tokhtarova, L.; Kanayev, D.; Mustafina, R.; Tarlykov, P.; Mukantayev, K. Evaluation of an In-House ELISA for Detection of Antibodies Against the Lumpy Skin Disease Virus in Vaccinated Cattle. Int. J. Vet. Sci. 2024, 13, 248–253. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).