1. Introduction

1.1. The Global and European Context of Population Ageing

The global population is ageing at an unprecedented rate, creating major social and economic challenges. Population ageing is expected to become a global trend with significant implications for urbanization and the environment. International organizations such as the United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have drawn attention to this demographic transition. For example, the WHO has promoted the concept of active ageing since the early 2000s, emphasizing the importance of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security to improve the quality of life of older people (WHO, 2002). At the global level, the UN has proclaimed 2021-2030 as the ‘Decade of Healthy Ageing’, highlighting the need for concerted action to support the older population (WHO, 2020). At the same time, the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) emphasize that demographic ageing will influence urban and economic development, requiring adaptation of public policies and urban infrastructure (OECD, 2015; World Bank, 2016). These global initiatives reflect the recognition that demographic change requires rethinking sustainable and inclusive development strategies.

Europe is facing a marked ageing process, being the continent with the highest proportion of older people. The European Union (EU) has initiated numerous policy initiatives in response to this demographic reality. TheGreen Paper on Ageing (European Commission, 2021) emphasizes the need for intergenerational solidarity and the mainstreaming of ageing in all policy areas, from the labour market to long-term care services. Also, the EU in cooperation with the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) has developed the Active Ageing Index (AAI), a composite index that measures the participation and potential of older people in society, highlighting both their contributions and areas where potential is untapped (European Commission & UNECE, 2019). These initiatives show Europe’s strong motivation to turn population ageing from a challenge into an opportunity by focusing on active ageing - a concept that promotes the idea that older people can remain healthy, active and engaged in the community for longer. In addition, European programs have designated 2012 as the “European Year for Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations”, marking the political commitment to this topic. Thus, the global and European context of an ageing population justifies the need for in-depth research: as the share of older people increases, cities and societies need to adapt to ensure the inclusion and well-being of all citizens, regardless of age.

1.2. Convergence Between Active Ageing and Inclusive Urban Social Innovation Ecosystems

In this demographic context, the concept of active ageing has become a central framework for policies for older people. Active ageing refers to maximizing opportunities for social participation, health maintenance and personal security as people age so that they can continue to contribute to economic and community life (WHO, 2002). At the same time, contemporary cities are moving towards smart and inclusive development models, increasingly seen as social innovation ecosystems in which diverse actors (local authorities, non-governmental organizations, communities, academia and the private sector) work together to generate solutions to complex societal challenges. The convergence of these two perspectives - active ageing and inclusive urban social innovation ecosystems - represents an innovative contextual approach to the present research.

On the one hand, active ageing has a strong urban dimension. Most older people live in cities and the urban environment directly influences their quality of life. The literature shows that the urban environment can create both stressors and opportunities for older people. For example, crowded cities can present challenges related to mobility, access to public spaces and health services, but cities also offer opportunities for social participation, access to culture and community support networks (Phillipson & Ray, 2016). The age-friendly city concept promoted by the WHO emphasizes the need to adapt urban spaces to the needs of older people, involving transformations in urban planning, transportation, housing and social services (Chapon, 2011; Zur & Rudman, 2013). In Europe, the Age-Friendly Cities and Communities initiative has been adopted by many municipalities, illustrating the convergence between active ageing policies and inclusive urban planning (Plouffe & Kalache, 2011). Such efforts demonstrate that active ageing strategies cannot be conceived in isolation, but require a supportive urban ecosystem that includes adapted physical infrastructure, community services, social support networks and opportunities for civic participation.

Inclusive Urban Social Innovation Ecosystems (IUSIEs ), on the other hand, provide a collaborative framework for action to address societal challenges, including those related to ageing. An urban social innovation ecosystem brings together different local actors to co-create solutions, often through participatory methodologies such as living labs or co-design. In the case of an ageing population, the convergence of these ecosystems with active ageing objectives is manifested in projects and initiatives aimed at the inclusion of older people in the life of the urban community. Recent studies show that cities promoting age-friendly environments are in fact addressing key aspects of sustainable urban development. For example, the creation of age-friendly and accessible age-friendly neighborhoods contributes not only to the well-being of the elderly, but also to social cohesion and the sustainability of the urban environment (Qian et al., 2019). Moreover, the concept of active longevity is gaining ground in current research, suggesting a positive approach to ageing that integrates social innovation into urban strategies (Kalachikova et al., 2023). An example of concrete convergence is the regional Healthy Aging model implemented in Styria, Austria, where an ecosystem of regional actors has been mobilized to create an integrated environment conducive to healthy and active ageing (Borrmann et al., 2020). These efforts show how social innovation in urban settings can support active ageing through policies and projects that facilitate older people’s engagement, independence and well-being. Cities thus become living laboratories, where solutions such as intergenerational cohousing, mobile community services or volunteering programs for the elderly are successfully co-created and implemented (McNeil-Gauthier et al., 2024; Cortés-Topete & Tavares-Martínez, 2022).

1.3. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Supporting Active Ageing

Digital technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) play an increasingly important role in supporting active ageing processes, especially in the context of smart cities. Modern urban ecosystems have technological infrastructures that can be harnessed to meet the needs of the ageing population. In the vision of smart cities described as innovation ecosystems underpinned by the Internet of the Future, opportunities are emerging for the development of inclusive digital services (Schaffers et al., 2012). AI can facilitate monitoring the health status of the elderly at home through smart devices and sensors, enabling early detection of medical problems and prompt interventions. Smart home solutions can also improve the safety and autonomy of older people - for example, home automation systems that automatically adjust lighting and temperature or remind daily medication. At the community level, AI applications can optimize public transport to be more accessible to the elderly, with tailored routes and autonomous vehicles serving neighborhoods with aging populations. Another emerging area is that of assistive robots and intelligent virtual assistants, which can provide companionship, help with online shopping or scheduling needed services, reducing feelings of social isolation. Studies show that integrating technology in urban environments helps to promote healthy and active ageing, from age-appropriate mobile exercise apps to online platforms for volunteering and civic participation for older people (Revellini, 2022). The concept of smart aging highlighted in the literature points to the potential of combining smart technologies with age-friendly urban design to create neighborhoods that support an active senior lifestyle (Revellini, 2022). At the same time, participatory approaches such as citizen science capitalize on new technologies to involve older people in data collection and co-creation of knowledge about the city, which enhances their sense of belonging and usefulness (Wood et al., 2022). Thus, AI and technological innovation act as enablers in urban ecosystems of social innovation, expanding the capacity of cities to provide personalized and effective solutions for active ageing. However, it is essential that technological development is complementary to social and community approaches to ensure that no older person is left behind in the digitization process.

1.4. The Relevance of the Theme for Public Policy and Contemporary Urban Planning

The theme of active ageing in inclusive urban ecosystems is of strategic importance for contemporary public policy and modern urban planning practice. As cities develop, planners and policy makers need to take into account the changing age structure of the population and integrate the principles of universal design and age-sensitive planning into their strategies. Current urbanism emphasizes the creation of built environments that promote health and participation for all age groups. Thus, public policies play a crucial role: collaborative and cross-cutting governance is needed to address the multidimensional needs of older people, from adequate housing and accessible transportation to health services and opportunities for social participation (Barrios et al., 2018; Plouffe & Kalache, 2011). The integration of these policies across sectors - health, mobility, housing, spatial planning - is essential for their effectiveness. For example, urban transport policies need to be linked with public spatial planning policies to ensure physical accessibility (Alidoust & Bosman, 2015), while housing policies should encourage innovative solutions such as intergenerational co-housing or adapted housing for the elderly (Font, 2024).

At international level, the relevance of this theme is reflected in major strategic frameworks. The UN’s New Urban Agenda (United Nations, 2017) emphasizes the commitment of states to make cities inclusive, safe and resilient for all, explicitly mentioning the need to include older people in the vision of sustainable urban development. Similarly, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (2030 Agenda) promote sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), emphasizing that they must meet the needs of all age groups. The OECD and the World Bank have produced reports arguing that cities of the future must be prepared for ageing populations, recommending investment in age-friendly infrastructure, long-term care systems and programs for the economic participation of older people (OECD, 2015; World Bank, 2016). Such recommendations also resonate with national and local policies. For example, many European cities have developed local ageing-friendly strategies , and the WHO-initiated Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities (Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities) includes more than 1400 communities in 51 countries (WHO, 2021). Contemporary urbanism is broadening its horizon to encompass these concerns: the concept of ‘longevity-ready cities ‘ has emerged to describe cities prepared for increasingly longer lives, moving from an age-friendly model to a proactive model of planning for longevity (Wang et al., 2021). This concept involves not only infrastructure adaptation, but also cultural and institutional changes that value the contributions of older people and encourage their continued participation in social and economic life.

The importance of the theme for public policy is also reflected in the need to avoid inequality and exclusion. If active ageing policies were to be implemented in a top-down manner without consulting older people, there is a risk that certain groups would be marginalized. Research emphasizes the need to involve all stakeholders - including older people themselves - in a participatory policy-making process to ensure the relevance and equity of proposed measures (Barrios et al., 2018). This approach also corresponds to the principles of inclusive social innovation, which emphasize co-creation and empowerment. For urban planning, this means participatory planning, consultation of older people in the design of public spaces and continuous feedback mechanisms on the functioning of the city for older people.

Last but not least, active ageing in urban environments also has an equity and social justice dimension. Cities include diverse categories of older people - some active and healthy, others frail or isolated - and policies need to address this diversity. The 5P ecological approach proposed by Lak et al. (2020) - person, process, place, prime (primary factors), policy - provides a holistic framework for understanding the interaction between the older individual and their environment. Subsequently, the same collective of authors developed an Active Aging Measure for Urban areas (AAMU) based on five domains (individual, spatial, socio-economic, governance and health) with 15 criteria and 99 indicators (Lak et al., 2021). These methodological developments underline the complexity of the phenomenon and the need for urban policies to be grounded on specific data and indicators in order to be able to assess the progress and impact of interventions.

In conclusion, active ageing in inclusive social innovation urban ecosystems is at the confluence of major contemporary concerns: demographic change, social innovation and sustainable urban development. The theme has particular relevance for integrated public policy making and for reshaping urban planning practices to make cities more inclusive, age-friendly and resilient to future transformations.

1.5. Research Objective

The main objective of this research is to develop a conceptual and analytical framework that explores how active ageing can be supported through Inclusive Urban Social Innovation Ecosystems (IUSIE), particularly in the context of smart cities. The study aims to examine the intrinsic link between inclusive social innovation and the evolving processes of active ageing, while emphasizing the role of artificial intelligence (AI) as an enabling and structural component. Through a systemic and interdisciplinary approach, the research will analyze how IUSIE—viewed as adaptive and collaborative ecosystems—can act as integrative environments that generate inclusive, sustainable, and longevity-ready urban models. The study also seeks to validate three hypotheses concerning the ecosystemic support for ageing, the operational mediation of AI through social innovation, and the systemic adaptability of smart cities expressed through inclusiveness.

2. Research Methodology and Hypotheses

This chapter presents the theoretical framework for research on active ageing in the context of inclusive urban social innovation ecosystem, while describing the methodological approach based on systemic modeling of smart cities as complex adaptive systems. Based on an extensive literature search (mainly papers from the period 2010-2025 indexed in Scopus and WoS), key concepts such as active ageing, smart cities, inclusive social innovation and the role of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in this field are integrated. The chapter also traces the evolution of conceptual approaches - from the 5P ecological model (Lak et al., 2020) to the new concepts of smartaging and longevity-ready cities (Wang et al., 2021) - highlighting relevant contributions to the transition towards age-friendly cities. Finally, an analysis from a systemic perspective of international examples of inclusive smart cities (such as Styria, Vienna, Singapore or Barcelona) is carried out, followed by the formulation and argumentation of the three research hypotheses of the paper.

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Active Ageing, Smart Cities and Inclusive Social Innovation

The concept of active ageing in urban settings. Active ageing is a multidimensional concept promoted by the World Health Organization, which aims to optimize health, participation and security opportunities for older people so that they maintain their quality of life as they age. In the urban environment, the application of active ageing principles is materialized through age-friendly cities and age-friendly communities initiatives that provide accessibility, support services and opportunities for older people to engage. Recent literature confirms the importance of the environment in promoting active ageing: for example, a study in Quebec shows how features of the built and social environment can stimulate older people’s participation and improve their health. Urban communities that provide accessible public spaces, adapted public transportation, adequate housing and social support networks contribute significantly to the well-being of the older population (McNeil-Gauthier et al., 2024; Qian et al., 2019; Levasseur et al., 2017). In addition, social participation and civic engagement of older people are essential factors of active ageing, possible only in an environment that facilitates their involvement. Studies highlight that cities that adopt age-friendly policies not only improve seniors’ health and social participation, but also contribute to health equity and social cohesion. For instance, a European study shows that facilitating older people’s access to the city and their involvement in community life is a recognition of the right to the city for this demographic group (Menezes et al., 2023). At the same time, active ageing policies in urban settings need to address multiple areas in an integrated way - from physical spatial planning (e.g., adapting infrastructure for reduced mobility, creating accessible green spaces), to health and care services, lifelong learning opportunities, and to the participation of older people in the economy and civic life. This ecological and integrative approach is captured by the 5P theoretical model proposed by Lak et al. (2020), which identifies five major interacting dimensions in active ageing: person (individual characteristics), processes (the ageing process and social interactions),place (physical and community environment), prime (primary support factors, e.g., family, support networks) and public policy (policymaking). This 5P framework emphasizes the complex and interconnected nature of active ageing, the relationships between the individual and the environment at personal, interpersonal and societal levels, and the need for a multi-sectoral approach to create healthy urban environments for older people.

Smart cities as complex adaptive systems. The smart city concept refers to the extensive use of digital technologies and data to improve urban quality of life, service efficiency and sustainable development. However, beyond the technological dimension, smart cities are increasingly recognized as complex adaptive systems in which numerous actors (government, citizens, private sector, civic organizations) interact dynamically, adapting to changing conditions (economic, demographic, technological). The characteristics of a smart city - interconnectivity, rapid information flows, interdependent subsystems (transport, energy, health, environment, etc.) - correspond to the description of a complex adaptive system, where emergent behaviors emerge and adaptive governance is required. Such systems cannot be planned only linearly, but require a systemic, integrative approach that takes into account emerging feedbacks and developments. Systemic smart city modeling involves representing the city as a set of interlinked components (infrastructure, communities, institutions, technologies) and studying how changes in one component (e.g., ageing population) have effects throughout the system. This approach is argued in recent literature: smart cities are seen as innovation ecosystems that are self-sustaining and evolve by continuously adapting to new technologies and social needs (Schaffers et al., 2012). In the context of demographic ageing, the adaptive nature of smart cities is put to the test - the city has to adapt its infrastructure and services to meet the needs of an increasing number of elderly people. According to complex systems theory, the degree of inclusion of vulnerable groups (such as the elderly) becomes an indicator of the adaptive capacity of the urban system. A truly resilient and sustainable smart city will integrate innovation mechanisms that actively include older people, capitalizing on their knowledge and ensuring their access to the benefits of technology (van Hoof et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2022). In this sense, the concept of the Inclusive Urban Social Innovation Ecosystem (IUSIE) describes how the city can function as an ecosystem oriented towards social innovation - i.e., generating new solutions to social problems with direct community involvement - aiming to include all population groups in the life of the city. Such an ecosystem includes networks of public, private and civic actors working together on innovation projects (e.g., community hubs, urban innovation labs, partnerships between municipality, universities and NGOs) to tackle problems such as access to services for the elderly, loneliness in old age or adap adaptive housing. Successful smart cities are developing such collaborative ecosystems, recognizing that technology alone is not enough - social innovation is needed to fold technology to people’s real needs and ensure inclusion (Borrmann et al., 2020; Patil et al., 2022). The methodological approach of this research is precisely based on the analysis of the city as a complex ecosystem, using systemic modeling to identify causal links and feedback loops between the process of active ageing and the IUSIE.

Inclusive social innovation and the role of technology (AI). Inclusive social innovation refers to the development of innovative solutions to social problems by actively involving the target groups and ensuring that the benefits of innovation reach everyone, including marginalized groups (in our case, older people). In the urban context, inclusive social innovation can take various forms: participatory co-design of public spaces, community platforms for mutual aid, intergenerational programs, innovative home health services, etc. An increasingly important element in such innovations is digital technology and artificial intelligence (AI), which can leverage social solutions. For example, inclusive smart cities use sensors, mobile apps, assistive robots or smart health platforms to support the elderly to maintain their independence. The key, however, is how these technologies are integrated: studies show that without an inclusive approach, technologies can fail to serve the elderly population, either due to lack of accessibility (design not suited to the needs of seniors) or lack of acceptance (resistance from users if they are not involved in the design of solutions)file-upetketkzrzzqnqnbzbf6mhgunqb. Inclusive social innovation acts as a bridge between technology and older users, ensuring that the development and implementation of AI solutions take into account the social context and diversity of needs. One example is the participatory co-design approach: Cinderby et al. (2018) show that involving older people in co-creating urban mobility solutions (such as street design or transportation apps) leads to more appropriate solutions and increased technology adoption. Similarly, Wood et al. (2022) emphasize the role of citizen science- the participation of senior citizens as research partners - in identifying ways in which the urban environment can be improved to promote healthy ageing. These examples illustrate how inclusive social innovation builds bridges between AI (seen as a technological tool) and active ageing processes (seen as a social phenomenon), through structural (networks, participatory institutions) and operational (projects, concrete services) mechanisms. In the literature, the term “smart-aging” has even emerged , denoting the merging of smart city and ageing-friendly concepts. Revellini (2022), for example, proposes the concept of smartaging in his study on the city of Venice, defining an age-friendly neighborhood augmented by smart technologies - an urban environment in which digital solutions (sensors, communication platforms, etc.) are used to enhance the autonomy and social participation of the elderly. Through such initiatives, technology becomes an enabler of social innovation: digital community support networks (e.g., social connection apps between seniors and volunteers) combat social isolation, telemedicine and home monitoring systems increase safety and health, and the city as a whole becomes more friendly and inclusive. In conclusion, a robust theoretical framework for this research merges the social ecology of active ageing (the 5P model and its subsequent variants) with the theory of the smart city as an adaptive ecosystem, emphasizing inclusive social innovation as a cross-cutting element connecting the social and technological dimensions in urban policies for older people.

2.2. Methodological Approach: Systemic Modeling of Inclusive Smart Cities

In order to investigate the relationship between smart cities, inclusive social innovation and active ageing, this paper adopts a systemic methodological approach. As already shown ,systemic modeling involves conceptualizing the city as a set of interrelated components and analyzing how these components evolve and influence each other. Smart cities are thus viewed as complex adaptive systems, and methodologically we draw inspiration from systems theory and urban ecology. The complex character derives from the multitude of actors and variables involved: the ageing population (with diverse health, mobility, socialization needs), the network of services (health systems, social care, public transport, housing), the built environment (urban infrastructure, public spaces), smart technologies (digital platforms, IoT, artificial intelligence) and the policy and governance framework. All these form an urban ecosystem. Adaptive character refers to the city’s ability to respond to change (e.g., rapid demographic ageing) through adjustment and learning mechanisms - e.g., adapting public policies based on feedback from citizens, changing behaviors as new technologies emerge, etc.

Why systemic modeling? The literature argues the need for a systemic perspective in the study of cities and active ageing policies, as the phenomena analyzed are interrelated and multi-level. For example, Lak et al. (2021) have developed an Active Aging Measure in Urban areas (AAMU) that includes five domains: individual, spatial, socio-economic, governance and health. These domains reflect different levels (micro, meso, macro) and factors ranging from individual characteristics (education, health) to community characteristics and local policies. Such a tool, based on the ecological approach, illustrates the usefulness of an integrated city perspective. Similarly, Barrios et al. (2018) proposed a Model of Local Ageing Policy Analysis (MALPA) to assess local active ageing policies, identifying priorities for intervention such as collaborative governance, involvement of older people in policy making, lifelong learning or reducing economic inequalities. This model emphasizes that, methodologically, the analysis of ageing policies needs to include structural factors (governance arrangements, level of public participation) in addition to concrete measures. In line with these approaches, the present research uses systemic modelling both conceptually (to build an integrated conceptual framework of the inclusive urban ecosystem) and analytically (to organize data and empirical evidence from examples of inclusive smart cities). Specifically, we will consider the city as an Inclusive Urban Social innovation Ecosystem (IUSIE). i.e., a system in which social innovation (new initiatives, projects, policies) is generated through the collaboration of urban actors and has as its guiding principle the inclusion of all citizens, including the elderly, in urban development processes. We analyze the city in terms of its components (sub-systems) relevant to active ageing: from the institutional network (public administration, research centers, NGOs, volunteer networks, private sector) that constitutes the social innovation infrastructure, to the technological resources (data, AI platforms, smart infrastructure) and to the target population (elderly, but also other community groups interacting with them). The relationships between these components are analyzed to understand the mechanisms through which support for active ageing is created and maintained in smart cities. One working hypothesis (supported by the literature on complex adaptive systems) is that inclusion and collaboration (e.g., involving older people in co-creation of services) act as positive feedback loops that strengthen the capacity of the urban system to adapt to ageing - in other words, cities that integrate feedback from the older population and socially innovate become more resilient and effective in meeting the needs of this population (Plouffe & Kalache, 2011; Zur & Rudman, 2013). Conversely, cities that fail to adapt can exhibit negative feedback - for example, exclusion of the elderly leads to social problems (isolation, burdens on the health care system) that, over time, affect the entire urban system. Therefore, systemic modeling allows us to argue, on theoretical grounds, the central role of the inclusive social innovation ecosystem in supporting active ageing processes in a smart city.

The research methodology is mainly qualitative and conceptual, based on literature review and international case studies. We will use the literature review to build the conceptual framework (as detailed above) and to identify indicators and good practices, while the case studies will serve to illustrate and test the hypotheses in a real context. Some examples of cities/initiatives (presented in the next section) that have addressed the challenge of an ageing population through smart and inclusive strategies will be examined from a systemic perspective. Thus, methodologically, we combine a systematic literature review with a comparative case analysis under the theoretical umbrella of systemic modeling.

2.3. Evolution of Conceptual Approaches: From the 5P Model to Smartaging and Longevity-Ready Cities

The field of active ageing in cities has evolved significantly over the last decades, passing through several conceptual paradigms. In this section, we integrate the recent literature in an evolutionary manner, highlighting how key concepts have progressed from the 5P ecological framework to new concepts of longevity-ready smart cities.

The 5P ecological model (Lak et al., 2020). A turning point in the literature is the emergence of the 5P model, proposed by Lak et al. as the result of an extensive systematic review of the determinants of active ageing. This model, already briefly described above, has had the merit of synthesizing into a coherent framework the multiple factors involved in active ageing. In contrast to previous approaches (such as the 2007 WHO guide on age-friendly cities, which identified 8 areas of intervention without highlighting the systemic relationships between them), the 5P model emphasizes the interplay between the individual, interpersonal and societal levels. Through elements such as processes (which include the social dynamics of ageing) and policymaking, the 5P framework suggests that active ageing is not just the responsibility of the individual or the health care system, but results from a complex ecology involving community and policy. In addition, Lak et al. (2021) extended this framework by developing a practical measurement tool (AAMU) based on 5 corresponding 5P domains valid in urban settings. This transition from concept to operationalization (through indicators and criteria) highlights an important contribution: it allows benchmarking a city’s ‘friendliness ‘ towards older people and identifying specific gaps (e.g., a city might be doing well in physical environment - infrastructure, but poor in governance - older people’s involvement in decision-making). The 5P model has paved the way for even more comprehensive approaches, while also opening up the discussion about integrating new technologies into the equation (in 2020, aut.ro mentions the need to adapt the tool to different urban contexts, leaving room for the integration of the digital dimension in the future).

The concept of Smart Ageing (Revellini, 2022). With the accelerated development of smart cities, researchers and practitioners have started to explicitly integrate the technological perspective into the age-friendly cities approach. The term smart aging (or smartageing) has emerged to describe the confluence between active ageing strategies and smart city solutions. Revellini (2022) proposes this concept in the context of neighborhood planning in Venice, arguing that an age-friendly neighborhood can be empowered by technology to become more efficient and accessible to the elderly. In practical terms, smartaging means that inclusive and accessible design principles (e.g., barrier-free sidewalks, ergonomic benches, local services for seniors) are combined with smart innovations (from smart street lighting and traffic sensors to wayfinding assistance apps or panic buttons connected to volunteer networks). This moves from the idea of the age-friendly city to the idea of the age-friendly smart city. The conceptual contribution of Revellini and other authors in this stream (e.g., Righi & Sayago, 2020 - oriented on participatory design of technology with the elderly) consists in defining the criteria of a “smartaging neighborhood”: e.g., accessible digitalization (technology with simple interface, adapted for seniors), online-offline connected communities (platforms that strengthen local social ties), augmented built environment (real-time information about the accessibility of routes, on-demand transportation, etc.). These ideas extended the ecological model by adding a digital dimension to each element: the elderly person becomes a technology user, social networks include online interactions, the physical place is augmented by IoT, processes include digital literacy, and public policies include e-inclusion strategies. With all the opportunities identified, the concept of smartaging also highlights the need for technological innovations to be inclusive. Revellini (2022) emphasizes that the classic WHO principles of universal design and elder participation remain fundamental in the digital age - if technology is not governed by these principles, we risk accentuating exclusion. In conclusion, the concept of smartaging marks an intermediate step in the paradigm shift: it recognizes the potential of AI and smart solutions in active ageing, but maintains the focus on social innovation and human-technology fit, not the other way around.

Longevity-ready cities (Wang et al., 2021). The latest conceptual horizon, in the context of a world where life expectancy is approaching 100 years in many metropolises, is the shift from simple age-friendly cities to longevity-ready cities. Wang et al. (2021), in an article published in Nature Aging, argue that a profound rethinking of the urban physical environment is needed to accommodate centenarian lives. They emphasize that while the first initiatives (2010s) focused on incremental adjustments (e.g., more benches, bus ramp), the longevity-ready concept implies structural transformations of the city. Key conceptual contributions include: (a) Long-term forward planning - cities need to be designed , now, for the populations of 2050 or 2100, when the proportion of 80+ year olds will be much higher; (b) Cross-cutting policy integration - ageing can no longer be a sub-field of social policy, but becomes a lens through which to view the whole of urbanism (from transportation and housing to environment and economy); (c) Adaptability and resilience - longevity-ready cities will be those capable of reinventing themselves according to the needs of new generations of older people (which may differ from those of the current generation). An example of longevity-ready thinking is the adaptation of housing infrastructure: technical solutions for assistive technology (sensors, smart faucets and doors, etc.), common spaces that encourage intergenerational interaction, and even functional flexibility (modular housing that can be reconfigured as residents age) should be integrated into new housing from the design phase. Wang et al. (2021) note that longevity-ready cities are not just about the elderly, but about an environment that actively supports longevity for all - i.e., promotes health and activity throughout life, preventing disability and isolation in old age. The contribution of this concept to the evolution of the field is paradigmatic: if the 5P model was focused on metrics and smartaging on technology integration, longevity-ready shifts the focus to designing for the future. This concept forces researchers and decision-makers to think systemically and prospectively: how do we combine urban development policies, social innovation and emerging technologies (AI, robotics, big data) to create cities where people can live to be 100 years old with a good quality of life? Essentially, longevity-ready is the natural extension of smartaging, in an extended time horizon and with a more long-term sustainability-oriented vision. The important implication here is also the link with sustainable development: a longevity-ready city also tends to be a more environmentally and economically sustainable city. Previous research indicates a positive relationship between age-friendly adaptations and indicators of sustainability - for example, a study in Hong Kong found that age-friendly initiatives (open spaces, accessible public transportation) also contribute to the sustainability of the overall urban environment (Qian et al., 2019). This suggests that adapting to ageing is not a parallel endeavor, but integrated into the overall quality of a sustainable smart city. The concept of longevity-ready formalizes this idea, showing that systemic adaptability to ageing is a new frontier of urban innovation.

In conclusion, the evolution of the literature from the 5P ecological model to smartaging and longevity-ready highlights the shift from descriptive theoretical frameworks to transformative paradigms: if 5P helped us to understand what factors matter for active ageing, smartaging and longevity-ready challenge us to imagine how cities can be reconfigured to cope with the longevity revolution, using social and technological innovation. These conceptual developments underpin our research hypotheses, suggesting that an inclusive and adaptive smart city could represent the optimal vision for the future of active ageing.

2.4. Inclusive Smart Cities - International Perspectives and Systemic Analysis

In order to anchor the theoretical discussion in reality, we will briefly analyze some notable examples of cities or regions that have implemented innovative strategies at the intersection of smart city and age-friendly city. The aim is to illustrate the concept of an IUSIE and to observe the manifestation of systemic adaptability in real contexts.

Styria model (Austria): regional ecosystem for healthy ageing. Styria, a region in Austria, has been recognized as an example of best practice in Europe by developing an integrated regional ecosystem for healthy ageing. The strategy called the “Styria Model “ has been documented by Borrmann et al. (2020), who describe the implementation of an integrated ecosystem-based healthy ageing region. This model is based on the creation of an extensive network of partners - regional authorities, universities and gerontological research centers, health care providers, medical technology companies, NGOs and local communities - working together to develop and test innovative solutions in support of older people. For example, rural telemedicine projects have been piloted in Styria (to connect elderly people in remote villages to doctors in cities via digital platforms), smart assisted housing (apartments equipped with sensors and voice assistants for the safety of seniors), and intergenerational school programs where young people train the elderly in digital skills. All these initiatives are strategically coordinated, based on collected data and scientific evidence, to ensure their regional scalability. From a systemic perspective, Styria is an example of a complex adaptive system in which inclusive social innovation is institutionalized: the network of actors continuously learns from project implementation, adapting regional policies. The Styria model shows that adequate support of active ageing processes can be realized at the regional scale through a well-articulated innovation ecosystem - thus confirming the hypothesis that an adaptive complex system,IUSIE, provides the necessary infrastructure for active ageing (H1, detailed in the next section).

Vienna (Austria): smart and age-friendly city. Vienna, the capital of Austria, is often cited as one of the most liveable cities in the world and has a long tradition in both inclusive social policies and smart planning. Vienna joined the WHO network of age-friendly cities early on, developing municipal plans dedicated to the elderly (e.g., ensuring accessibility to public transport, senior community centers in every neighborhood). In parallel, the city also has an ambitious smart city strategy (Smart City Wien Strategy), which includes sustainability, digitalization and innovation goals. The intersection of these two directions can be seen in projects such as CASE - Care Showroom Vienna, where different vendors showcase smart home technologies and robotic assistance for home care for the elderly, or the municipal Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) Care program which funds start-ups and tech solutions for the elderly. Another example is the integration of social housing for the elderly with technology: Vienna has modernized many social housing buildings by installing smart access control systems and environmental sensors, while making it easy for residents to connect to a social call-center in case of need. The Viennese approach is a classic example of IUSIE: the municipality (public sector) works closely with the academic sector (Vienna University of Technology has an institute dedicated to environmental assistance), private firms (medical equipment manufacturers, local IT companies) and seniors’ organizations to implement solutions. From a systemic perspective, inclusion is a fundamental principle of Vienna’s adaptability - from the design of shared space streets (shared pedestrian-vehicle spaces that also favor slow pedestrians such as some elderly people), to the participatory local budgeting process where senior citizens’ associations have a say. The result of these integrated efforts is reflected not only in the well-being of the elderly, but also in the sustainability of the city: an age-friendly city also tends to be a greener, calmer, better city for all ages (e.g., wide sidewalks, efficient public transport and accessible parks are appreciated by all citizens, not just the elderly). Thus, the case of Vienna supports the idea that the smart city’s inclusivity is a manifestation of its systemic adaptability (H3).

Singapore: smart nation and active ageing. Singapore, a city-state known for its smart nation policy, is facing one of the most rapid demographic transitions towards an ageing population in Southeast Asia. Its response has been the development of a national Action Plan for Successful Ageing (Action Plan for Successful Ageing, launched in 2015) comprising more than 70 initiatives, many integrating technology and social innovation. Singapore provides an outstanding example of integrating AI and smart infrastructure to support older people in a systemic and inclusive manner. For example, the Kampung Admiralty Neighborhood is an international award-winning project: it is a vertical complex that combines public housing for the elderly, a polyclinic, shopping and dining spaces, and a community center with a rooftop park - all in an integrated, longevity-friendly design. In this complex, technology plays a key role (smart elevators, home health monitoring systems, delivery apps for the mobility-impaired), but the whole concept is one of social innovation - bringing essential services together and facilitating social interaction between seniors and the rest of the community (through the community market and community garden). Citywide, Singapore has implemented sensor networks at home (to automatically detect if a senior living alone has a problem, triggering an alert to social services) and pilot projects with autonomous vehicles to transport seniors to dedicated campuses. The success of these initiatives is ensured by joined-up governance: the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of National Development and other agencies collaborate through an Active Ageing Council, ensuring cross-sectoral coordination - a crucial element of the innovation ecosystem. The city’s adaptive city system is also evident in the way the community is engaged: there are networks of digital volunteers teaching seniors how to use smartphones (the Seniors Go Digital program), incubators for silver tech start-ups and even a regularly monitored Age-Friendly City Index that guides urban policies. The Singapore case demonstrates the role of inclusive social innovation as a bridge between technology and people (supporting hypothesis H2): none of the tech achievements would have been widely adopted without digital inclusion campaigns and co-creation of services with the elderly community. At the same time, the city’s adaptability shows in the results: although very dense and high-tech oriented, Singapore has managed to create a support network for the elderly that has led to decreased social isolation and improved health indicators in old age (according to ministry reports, over 90% of the elderly are independent in their daily activities and feel secure in their community).

Barcelona (Spain): urban social innovation and civic engagement. Barcelona is recognized both as a hub of social innovation and as a pioneer of the smart city concept in Europe. Over the last decade, the city has initiated a number of projects that combine citizen participation with technology to address social challenges, including ageing. One flagship project is Vincles BCN, a mobile app developed by the city in collaboration with the non-profit sector to combat loneliness among the elderly. Vincles creates a virtual network around the elderly person, connecting them with family, friends, neighbors and volunteers, facilitating group video calls, photo sharing and group messaging in a very streamlined way. Although it is a digital solution (AI being used, for example, to suggest connection when someone has not been active for a long time), Vincles’ success is due to its inclusive approach: the development directly involved the elderly from the prototype phase (testing and feedback sessions), and the implementation was accompanied by human support (trainers helping beneficiaries to use the tablets and the app). This project won the EU Horizon Award for Social Innovation, demonstrating how inclusive social innovation acts as a link between technology and social need - validating the H2 hypothesis. Barcelona has also experimented with Civic Labs (Barcelona Laboratori, at Fab Lab Barcelona) where intergenerational workshops were held to prototype more age-friendly urban furniture, using 3D printers and ideas from citizens. Also in Barcelona’s urban planning, the concept of superblocks (super-ille) - reconfiguring traffic to create pedestrian neighborhoods - has greatly benefited the elderly by providing safe spaces for walking and socializing close to home. The fact that seniors were involved in the consultations on the superblocks ensured that these mini-neighborhoods included the benches, rest areas and greenery they needed. Barcelona exemplifies how a city can learn and adapt through participatory experimentation: the local government has created platforms (both physical and online) through which citizens - including seniors - can propose and vote on ideas, collaborate with experts on prototypes, then scale effective solutions citywide. This is the behavior of an adaptive urban system: through constant feedback and learning loops, the city becomes more inclusive. It is no coincidence that Barcelona is also an active member of global networks such as the AGE-Friendly Cities Network and the Open Government Partnership, promoting precisely these values of inclusiveness and adaptability. The example of Barcelona particularly supports hypothesis H3 - that inclusiveness (ensuring that all citizens, regardless of age, can contribute and benefit) is a manifestation of systemic adaptability: the city has adapted to new realities (more single elderly, for example) by innovating ways of engaging and providing community support.

Through these brief case studies (Styria, Vienna, Singapore, Barcelona) we observe a common thread: cities/regions that are successful in supporting active ageing are those that have adopted an ecosystemic vision, integrating technology, public policies and community initiatives in an adaptive and inclusive way. These examples provide valuable empirical support for our research hypotheses, showing that the theories discussed above (the adaptive complexity of cities, the role of inclusive innovation, etc.) are also found in practice.

2.5. Research Hypotheses

In the light of the theoretical framework and evidence from literature and practice, we formulate the following research hypotheses, which will guide our scientific endeavor:

H1: In smart cities, adequate support for the evolution of active ageing processes is provided by a complex adaptive system – the Inclusive Urban Social Innovation Ecosystem (IUSIE). This hypothesis assumes that, for a smart city to successfully facilitate active ageing of its population, a well-developed ecosystem of actors and processes of inclusive social innovation is necessary. In other words, a set of disparate policies or isolated technologies is not enough; what makes the difference is the systemic interconnectedness and adaptability of these initiatives. Arguments from the literature support this view: Lak et al. (2020) showed that only ecological, multi-dimensional approaches capture the complexity of active ageing. Borrmann et al. (2020) provided a practical example (Styria) where a regional ecosystem led to notable results, suggesting that a city/region functioning as a complex system provides more coherent support for older people. Also, fragmented or strictly top-down approaches have proven insufficient or even counterproductive - for example, the implementation of age-friendly city programmes without local consultation and adaptation has been criticized as being productivist and risking exclusion of the vulnerable. On the contrary, involving all relevant stakeholders in a participatory manner (e.g., collaborative governance with the inclusion of the elderly, as emphasized by Barrios et al., 2018) is the factor that transforms a set of interventions into a genuine adaptive ecosystem. H1 thus anticipates that smart cities that excel in supporting active ageing are precisely those that function as innovation ecosystems: flexible, participatory, with feedback loops that allow for continuous learning and adjustment of policies and solutions. We will test this hypothesis by examining the degree of development of innovation ecosystems in the cases studied and the correlation with indicators of success in active ageing (e.g., elderly quality of life, level of social participation, perceived health, etc.).

H2: Inclusive social innovation constitutes the structural and operational link between AI (artificial intelligence) and active ageing processes. With this hypothesis we argue that technology (especially AI and digitization-based solutions, characteristic of smart cities) and the social process of active ageing cannot harmoniously merge without appropriate mediators, and the main mediator is inclusive social innovation. In other words, AI can empower active ageing only if it is implemented in inclusive and socially innovative ways. The literature provides multiple clues in this regard: Revellini (2022) showed that the introduction of smart technologies in an elderly neighborhood requires the adoption of WHO inclusive design principles, otherwise the technology remains underutilized. Examples such as the co-design of mobility solutions (Cinderby et al., 2018) demonstrate that participatory methods are essential to connect the needs of the elderly with technology design. Wood et al. (2022) suggest that the direct involvement of seniors through citizen science has generated data and insights that were otherwise missing from urban planning, leading to more appropriate solutions. Without such social innovation processes, AI technologies risk ignoring the particularities of the elderly - for example, smart city algorithms that do not account for reduced mobility may optimize traffic for the working population, but create difficulties for seniors. Inclusive social innovation therefore acts both structurally (by creating networks, institutions and policies that integrate the social and technological dimensions - e.g., a national program for digital inclusion of the elderly, or a senior advisory council to the city hall that guides the implementation of smart solutions) and operationally (through concrete projects, prototypes, social experiments that align technology with the human context). Hypothesis H2 will be investigated by analyzing how the cities studied have implemented technology for the elderly: where they have been successful (e.g., Singapore, Barcelona), we expect to find strong elements of social innovation (campaigns, co-creation, participatory structures); conversely, if we identify failures or obstacles, we anticipate that these will be related to the absence of the inclusive component (e.g., Support for the hypothesis will result from linking these findings with positive outcomes on active ageing, clearly suggesting that inclusive social innovation is the indispensable linking factor.

H3: The inclusiveness of smart cities is a manifestation of their systemic adaptability. This hypothesis derives from the perspective of cities as complex adaptive systems and postulates that an adaptive smart city will be characterized by inclusiveness, especially towards growing demographic groups such as the elderly. In other words, how well a smart city manages to include older people in the life of the community (both physically and digitally) is an indicator of its ability to adapt to major social changes. The arguments supporting this claim are both theoretical and empirical. Theoretically, the adaptability of a system translates into the ability to adjust its structures and functions to maintain performance under new conditions. Population ageing is just such a shock or pressure on the urban system - cities that adapt will change the spatial structure (e.g., by rethinking transportation, housing, services), the results of which we will see as more age-friendly and accessible cities. Empirically, comparative studies show a link between inclusive policies and indicators of urban sustainability: Qian et al. (2019) provided evidence that, in Hong Kong, districts with high age-friendliness scores were also those that performed better on sustainability indicators. Another global study (Wang et al., 2022) suggested that population ageing can reduce certain environmental pressures associated with urbanization, conditional on the existence of adaptive policies The interpretation would be that cities that integrate ageing (e.g., by promoting alternative mobility, local care economy, etc.) achieve offsetting effects such as reduced emissions or traffic (given that an older population has different consumption and travel patterns). Cities that learn to be inclusive of older people also develop capabilities that make them more resilient to other challenges - for example, volunteer networks set up to help seniors during hot summers (an initiative in several European cities) can also be activated for other crisis situations (such as helping vulnerable people in pandemics or natural disasters). Conversely, lack of inclusion may signal systemic rigidity: cities that fail to provide access to the urban environment for the elderly probably indicate more general deficiencies in participatory planning processes and adaptation to citizens’ needs. H3 will be tested by assessing the degree of inclusion of the cities analyzed and correlating it with how they have managed change (not only demographic, but also technological or environmental). We expect to find that inclusive smart cities (such as those discussed above) are exactly those that have demonstrated their adaptability over time - which would confirm that inclusiveness is a visible manifestation of a deep-seated adaptive mechanism.

Finally, the above three hypotheses will be subject to analysis throughout the research. They are not independent, but interconnected: H1 sets the general framework (the need for a complex adaptive ecosystem for active ageing), H2 focuses on a specific element of that ecosystem (the role of inclusive innovation in linking technology and ageing), and H3 refers to the final outcome or indicator of the success of the ecosystem, namely the degree of inclusiveness achieved, seen as evidence of adaptation. Proving (or disproving) these hypotheses will contribute to scientific knowledge in the field, while providing practical guidelines for urban policies to ensure that the smart cities of the future will be truly age-friendly and prepared for the longevity society

3. Inclusive Social Innovation Ecosystem for Active Ageing in Smart Cities

3.1. Introduction and Context

Urban populations globally are undergoing a rapid process of demographic ageing, which requires rethinking how cities support older people. Active ageing is a concept promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO) which aims to optimize opportunities for health, social participation and security as people age so that they maintain their quality of life

In the urban context, this means creating inclusive and age-friendly environments that enable older people to be physically, economically and socially active for as long as possible. Initiatives such as the Age-Friendly Cities program launched by the WHO in 2007 have highlighted the need for cities to adapt to ageing, underlining the importance of strategic planning and local policy coordination to make urban communities age-friendly. Recent studies confirm that built and social environmental factors can significantly promote active ageing - for example, adapting public spaces and housing, as well as providing opportunities for community participation, have led to improved health status and engagement of older people in two municipalities studied in Quebec, Canada. Without appropriate interventions, however, there is a risk that older people will become isolated or marginalized in technologized cities; the phrase “you become invisible” captures the feeling of some older people in large cities when the urban environment no longer reflects their needs.

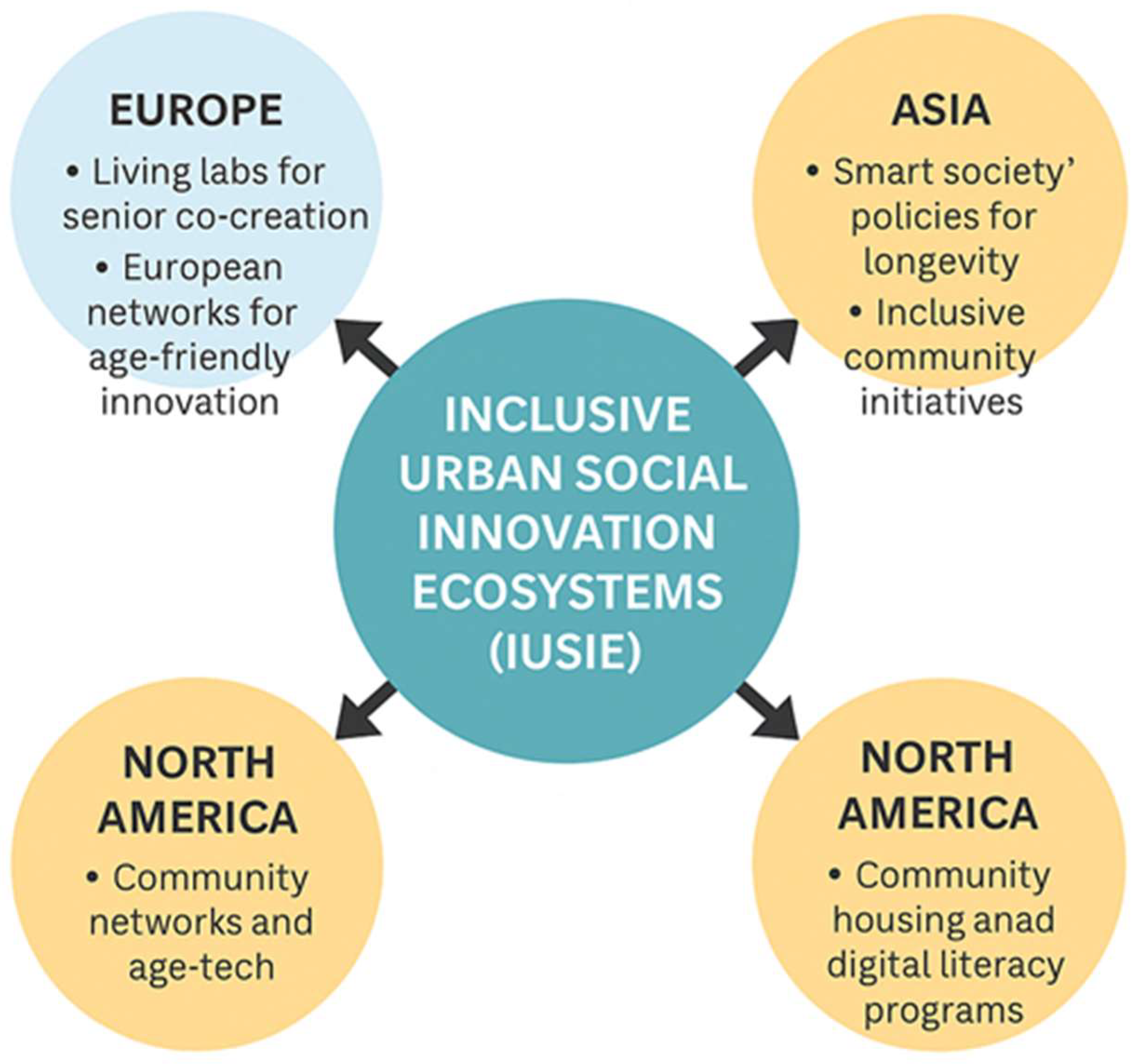

Against this background, the smart city concept - originally defined by integrating information technologies to optimize urban services - is evolving to include the social and age dimensions. A genuine smart city is not limited to smart infrastructure, but is also becoming inclusive, harnessing innovation to respond to social challenges such as an ageing population. Thus, the need emerges for an inclusive urban social innovation ecosystem (IUSIE ) geared towards active ageing, where technology, public policy and community initiatives converge. Europe, Asia and North America have started to systematically address this challenge. Cities in Europe, for example, are developing “urban longevity” strategies, moving from the concept of the “age-friendly city” to the “longevity-ready city”, which involves radically adapting the physical and social environment for populations that can reach 100 years. In North America, the network of age-friendly communities (e.g., initiatives supported by AARP in the USA and by local governments in Canada) demonstrates the benefits of participatory urban planning, directly involving older people in shaping local policies (Plouffe & Kalache, 2011). In Asia, cities such as Hong Kong and Taipei are experimenting with innovative solutions - from redesigning neighborhoods to be age-friendly and sustainable, to urban community gardening programs involving older people (the case of Taipei’s Garden City ) as a way to increase well-being and social inclusion.

In this global context, the need for a clear conceptual and operational framework for EISI dedicated to active ageing in smart cities is emerging. The following sections address this framework, defining the concept and its ecosystemic characteristics, detailing the operational component (actors, collaborative relationships and tools used) and drawing conclusions on how such an ecosystem can be successfully implemented in different regions of the world.

3.2. Inclusive Social Innovation - Concept and Ecosystem Characteristics

Social innovation refers to the development of new ideas, services or models that aim to address social needs while bringing value to the community and generating positive social change. Unlike pure technological innovation, social innovation emphasizes collective benefit and participation. The concept of inclusive social innovation particularly emphasizes the involvement of vulnerable or marginalized groups in the innovation process - both as beneficiaries and as co-creators of solutions. In this case, this group is the urban elderly, who are often not sufficiently consulted in the development of smart city solutions. A social innovation becomes inclusive when older people are actively involved in defining problems and co-creating solutions to improve their lives, thus ensuring that the results reflect the diversity of their needs and capabilities.

Seen through an ecosystemic lens, inclusive social innovation for active ageing is not a singular or isolated endeavor, but part of an interconnected system of actors, factors and resources that interact dynamically. An innovation ecosystem encompasses all the conditions and participants that enable the emergence and diffusion of innovation - from legislative and policy frameworks, to institutions, communities and markets. The essential characteristic of such an ecosystem is the holistic approach: the recognition that the challenge of active ageing has multiple dimensions (health, mobility, housing, socialization, etc.) and requires interventions at different levels (personal, community, urban, national). Recent literature proposes ecological/ecosystemic models that incorporate this multidimensionality. For example, Lak et al. (2020) developed a framework called the 5P model - person, processes, place, levers (prime) and policies - to conceptualize the interrelated factors of active ageing in an urban environment. This model highlights that, in addition to the individual characteristics of the older person, social and care processes, the physical spaces of the city, key levers or initiatives that stimulate change (e.g., innovative technologies or programs), and public policies that create the enabling context matter.

In an inclusive social innovation ecosystem, cross-sectoral collaboration is a defining feature. Many actors - public administrations, NGOs, the academic community, the private sector and citizens - join forces in a quadruple helix configuration (government - industry - academia - civil society) to co-create solutions. For example, at EU level, the European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP on AHA) was launched in 2013 as an open innovation network aimed at connecting relevant actors from different sectors and countries and stimulating the exchange of best practices. A study conducted in the Styria region of Austria (Borrmann et al., 2020) describes the development of an integrated regional ecosystem for active and healthy ageing, using a stepwise co-creation process that involved actors from macro (authorities and policies at provincial level), meso (local organizations, service providers) and micro (local communities, senior citizens) levels. The results highlighted a number of key ecosystemic characteristics: the need for visibility and accessibility of services and products for the elderly (as key factors for successful innovation), the central role of actors such as health professionals (identified as ‘drivers’ of innovation in Styria) and the importance of effective communication between all levels of the system (from the local community to the market and the health system). These observations confirm that an effective ecosystem cannot function without the alignment of goals and efforts among multiple stakeholders and mechanisms to facilitate the flow of information and resources throughout the system.

The inclusiveness of the ecosystem also implies a culture of intergenerational participation and empathy. Inclusive social innovation thrives in environments where older people are seen as a resource and active partners, not just passive beneficiaries. Cities that have adopted such perspectives have set up senior advisory councils, age-sensitive participatory budgets or social innovation living labs where young and old design solutions together. An outstanding example at the community level is the Taipei urban garden program mentioned above, where the direct involvement of older people in urban agriculture activities has led to increased social inclusion and well-being, demonstrating the potential of such collaborative interventions. Similarly, citizen science projects in Europe and the USA have mobilized older citizens in collecting data about the urban environment (e.g., mapping the accessibility of sidewalks or assessing the quality of parks), thus providing not only valuable information for authorities, but also opportunities for participation and valuing the local knowledge of seniors. All these initiatives reflect the ecosystemic characteristics of inclusive social innovation: broad collaboration, multidimensionality, focus on real needs and adaptability to context.

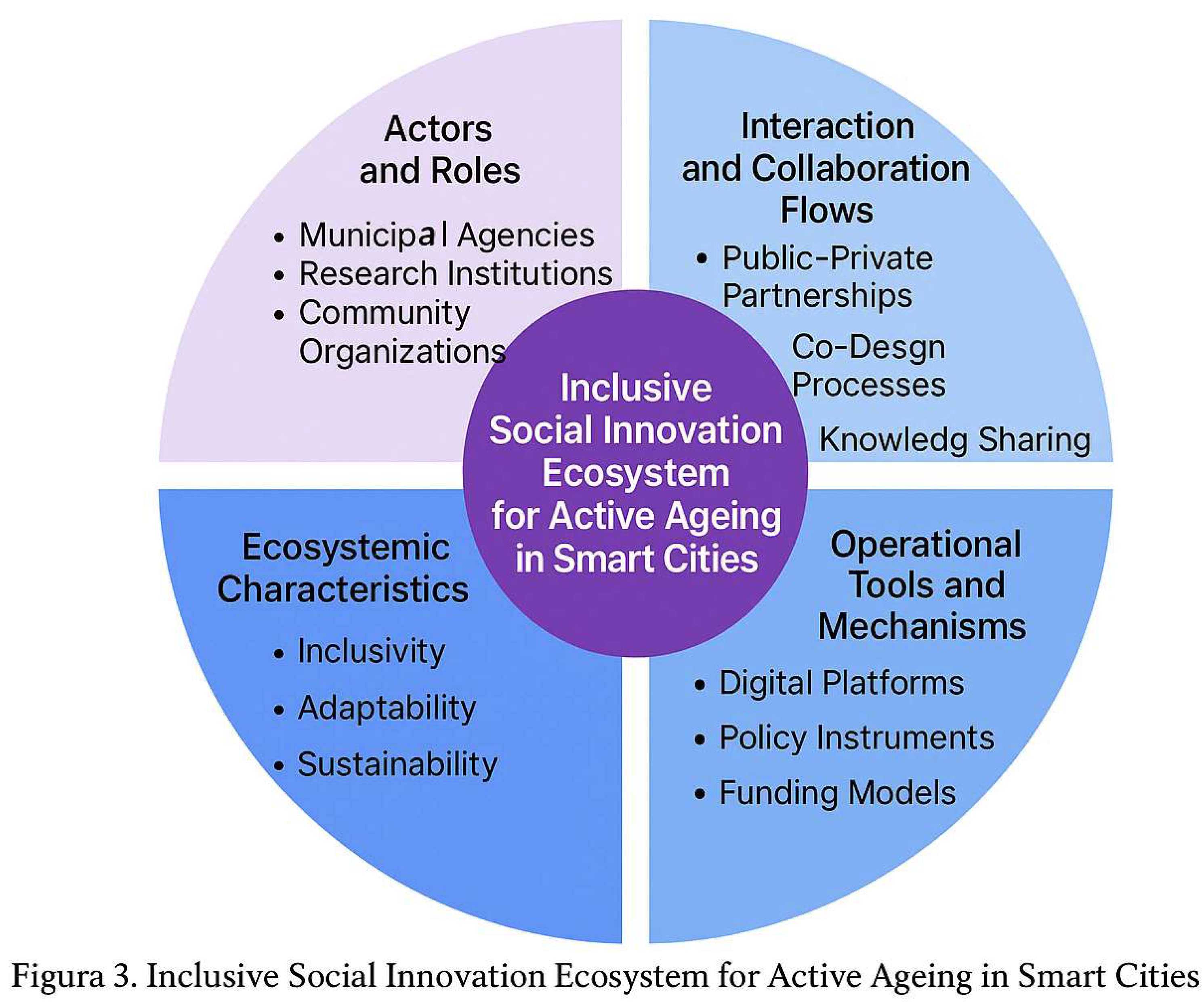

3.3. The Operational Component of IUSIE

For the theoretical principles of inclusive social innovation to materialize into concrete outcomes, a robust operational component of the ecosystem is needed - starting from identifying key actors and their roles, continuing with establishing the flows of interaction and collaboration, and defining the tools and mechanisms through which the ecosystem achieves its objectives. In the following sections (2.3.1 - 2.3.3) we detail these operational elements, illustrating them with practical examples from different regions (Europe, Asia, North America) where relevant.

3.3.1. Actors and Roles

An inclusive social innovation ecosystem for active ageing brings together a variety of actors. Each actor brings specific resources, perspectives and competences and plays a distinct role within the ecosystem. The main actors and their roles can be described as follows:

Public authorities (local and central government) - They have the role of strategic coordination and ensuring favorable public policies. Mayors, local councils and ministries develop inclusive smart city strategies and active ageing policies, allocate funding and create the legislative framework that enables social innovation to flourish. For example, the integration of older people’s issues into urban and transport plans (e.g., ensuring accessibility of public transport) is often initiated or regulated by authorities. Collaborative governance is essential: effective authorities create platforms for dialog with other stakeholders and encourage the direct participation of older people in decision-making.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community-based organizations - These act as intermediaries and advocates for the older community. NGOs often provide social services, organize activities for older people and may initiate pilot innovation projects (e.g., intergenerational mentoring programmes, digital literacy workshops for seniors, etc.). Their role is to connect older people with each other and with the rest of society, to identify needs on the grass-roots level and to exert constructive pressure on authorities for change. Many social innovations in support of the elderly - from time banks where seniors can offer and receive services, to networks for visiting isolated people - are initiated by such community-based organizations.

Academic and research institutions - Universities, research institutes and even living labs affiliated to them contribute scientific expertise and data. They assess the needs (e.g., through studies on the quality of life of older people in urban environments, develop and test innovative solutions (assistive technologies, mobile health apps, collaborative living models, etc.) and analyze the impact of interventions. The role of academics is also to facilitate co-creation processes - for example, researchers modeling workshops where the elderly, young people and designers design prototypes of adapted urban furniture together. Research is also providing measurements and indicators to monitor the progress of the ecosystem: one example is the development of the Active Aging Measurement in Urban Areas (AAMU) which uses multiple indicators to assess cities’ performance in this regard.

The private sector and social entrepreneurs - Technology companies, healthcare firms, real estate developers, and local small businesses play the role of practical innovators and solution providers. They can develop products and services dedicated to the elderly (from telemedicine apps and smart home systems for home health monitoring to age-friendly commercial spaces). In an inclusive ecosystem, the private sector works with other parties to ensure that innovations are appropriate and accessible to older people. For example, transport firms can collaborate with seniors’ organizations to create ridesharing services adapted to reduced mobility; real estate developers can work with authorities on intergenerational co-housing projects , integrating housing for young and old in the same complexes, facilitating mutual aid. Social entrepreneurs can experiment with inclusive business models, such as employing seniors as mentors for younger employees or producing goods and services by elderly communities, combining social impact with financial sustainability.

Older people and their social network (family, neighbors) - At the heart of the ecosystem are the active beneficiaries themselves, i.e., senior citizens. They have a dual role: on the one hand, they are the experts by experience who know their own needs best and can provide valuable feedback on what works and what does not; on the other hand, they can be co-creators of solutions, partners in pilot projects and promoters of change among their age group. Involving older people directly - through public consultations, senior citizens’ councils, participatory workshops - ensures the relevance of social innovation. Successful examples include groups of seniors who have contributed to the design of more accessible parks or the definition of preferential public transport routes, demonstrating that their voice can shape urban interventions (Cinderby et al., 2018). Family and neighbors also play a supportive role in helping seniors adopt solutions (e.g., by helping them use a new digital app) and creating a safety net around people with frailties.

In summary, the diversity of actors is the strength of the inclusive social innovation ecosystem. Each actor contributes to the social capital of the ecosystem - be it knowledge, trust, funding or implementation power. The key to success lies in the clarity of roles and the commitment of everyone to work with others towards the common goal: an age-friendly smart city.

3.3.2. Flows of Interaction and Collaboration

A complex web of interactions is created between the actors described above. Collaborative flows within the ecosystem are the channels through which information, resources (financial, human, technological) and decisions flow. Effective design of these flows is essential for the ecosystem to generate innovation and not become fragmented.

A first dimension of collaboration is institutional and intersectoral. This includes formal and informal partnerships between public institutions, firms, NGOs and universities. For example, the municipality of a smart city may partner with a university and a business incubator to launch an urban innovation lab focused on solutions for the elderly. In this lab, students, researchers, NGO representatives and seniors work side by side to prototype ideas (such as a visually impaired-accessible urban navigation app) - exemplifying the multi-stakeholder co-creation model. Such cooperation flows can be facilitated by the existence of communication platforms and networks. At European level, the aforementioned EIP on AHA has functioned as a hub-and-spoke network, connecting cities and regions, enabling them to exchange data, research results and best practices in the field of active ageing. At the local level, community councils for older people or interdepartmental committees (health, transport, housing) within city halls create bridges between sectors, ensuring policy integration and avoiding silo working. The literature emphasizes the importance of integrating policies across multiple sectors - health, transport, housing, technology - to address the complex needs of older people.

A second dimension is horizontal collaboration at community level, where the emphasis is on solidarity and self-organization of citizens. In an inclusive innovation ecosystem, older people interact not only with institutions, but also with each other and with other generations. Informalsocial flows - e.g., meetings in community centers, online discussion groups between seniors, intergenerational volunteering networks - allow knowledge transfer (such as health or technology advice) and early identification of problems. An example of successful collaboration is the SeniorNet initiative (present in some North American cities), where more internet-savvy retirees teach others how to use digital tools, creating a peer-to-peer flow of information that complements formal digital inclusion programs. Another example, from rural Europe, is time banks or intergenerational exchanges of services (a young person helps an elderly person to go shopping and the elderly person helps him or her with professional guidance or other support), which illustrate flows of reciprocity that strengthen social cohesion. These horizontal interactions, although perhaps less visible, fuel the ecosystem with trust and empathy, intangible but crucial factors for the sustainability of social innovation.

A third key dimension is knowledge and data flows. In smart cities, data about older people’s needs and behaviors become a resource for innovation. Collaboration between the public and private sector can lead to data sharing (while of course respecting confidentiality): for example, hospitals and clinics can provide (anonymized) data about the main health problems of seniors in a neighbourhood, and this information can guide a tech company to develop a targeted home telecare solution. Digital platforms such as urban open data can include datasets on infrastructure accessibility, the geographical distribution of the elderly population, satisfaction survey results - all of which can be used by social innovators to inform projects. A notable example is the European Crosswalk project: in several cities, authorities worked with senior volunteers equipped with sensors to collect data on sidewalk conditions and traffic light duration, which was then used to recalibrate crossing times at pedestrian crossings, demonstrating how civic tech and citizen science can create useful data streams and concrete actions.

Last but not least, funding and resource flows determine ecosystem dynamics. Attracting funds (public, private, philanthropic) for social innovation projects is facilitated by collaborations: multi-actor consortia can apply for international grants (e.g., EU Horizon Europe programs for social research and innovation), public-private partnerships can mobilize investments in adapted infrastructures (from housing to care networks), etc. Also, human resources - volunteers, dedicated professionals - circulate in the ecosystem: for example, a volunteer sociology student can be a link between an NGO and the social welfare department of the city hall, facilitating communication and the implementation of a community project. The Styria study mentioned above shows that communication channels between all levels (micro-meso-macro) and between the public health system and the market need to be strengthened, otherwise innovations will not reach the intended target groups. Thus, connectivity - both in a technological (digital infrastructure) and organizational (collaborative networks and platforms) sense - is the lifeblood that irrigates the entire ecosystem of inclusive social innovation. Without well-defined flows, the ecosystem risks becoming fragmented and good intentions of actors remain isolated in pilot projects without systemic impact.

3.3.3. Tools and Operational Mechanisms

For the effective functioning of the ecosystem and the materialization of collaborations into tangible results, a set of tools and operational mechanisms is needed. These can be very varied in nature - from policy frameworks and strategies, to technology platforms, participatory working methodologies and funding instruments. We will detail the most relevant: