Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

23 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Participants

2.3. Sociodemographic, Cognitive and Clinical Features Characteristics

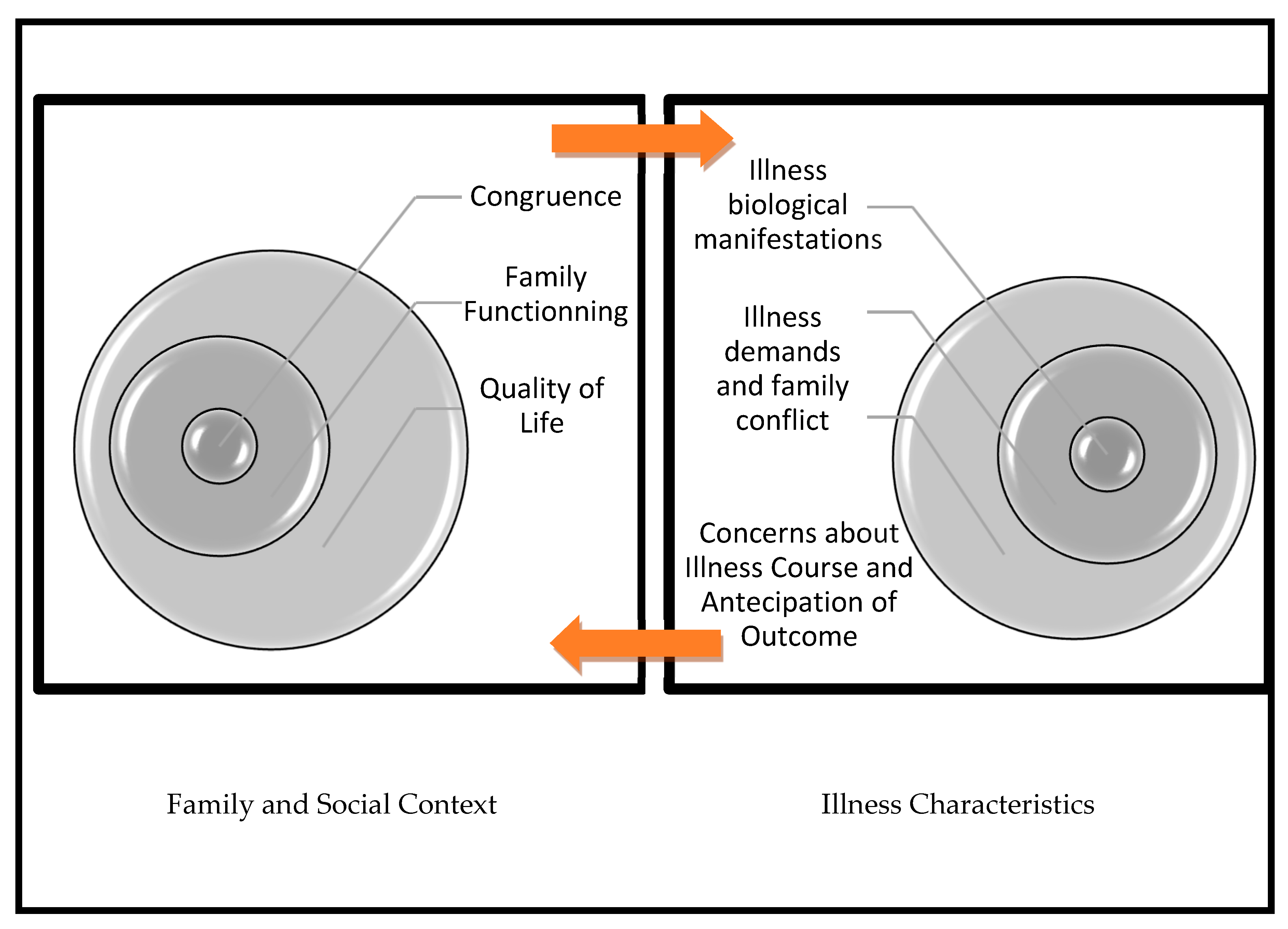

2.4. From Family to Diabetes Management

2.4.1. Individual Level as a Whole

2.4.2. Intrafamily Level

2.4.3. Extrafamily Level

2.5. From Diabetes Demands to Family Conflict

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

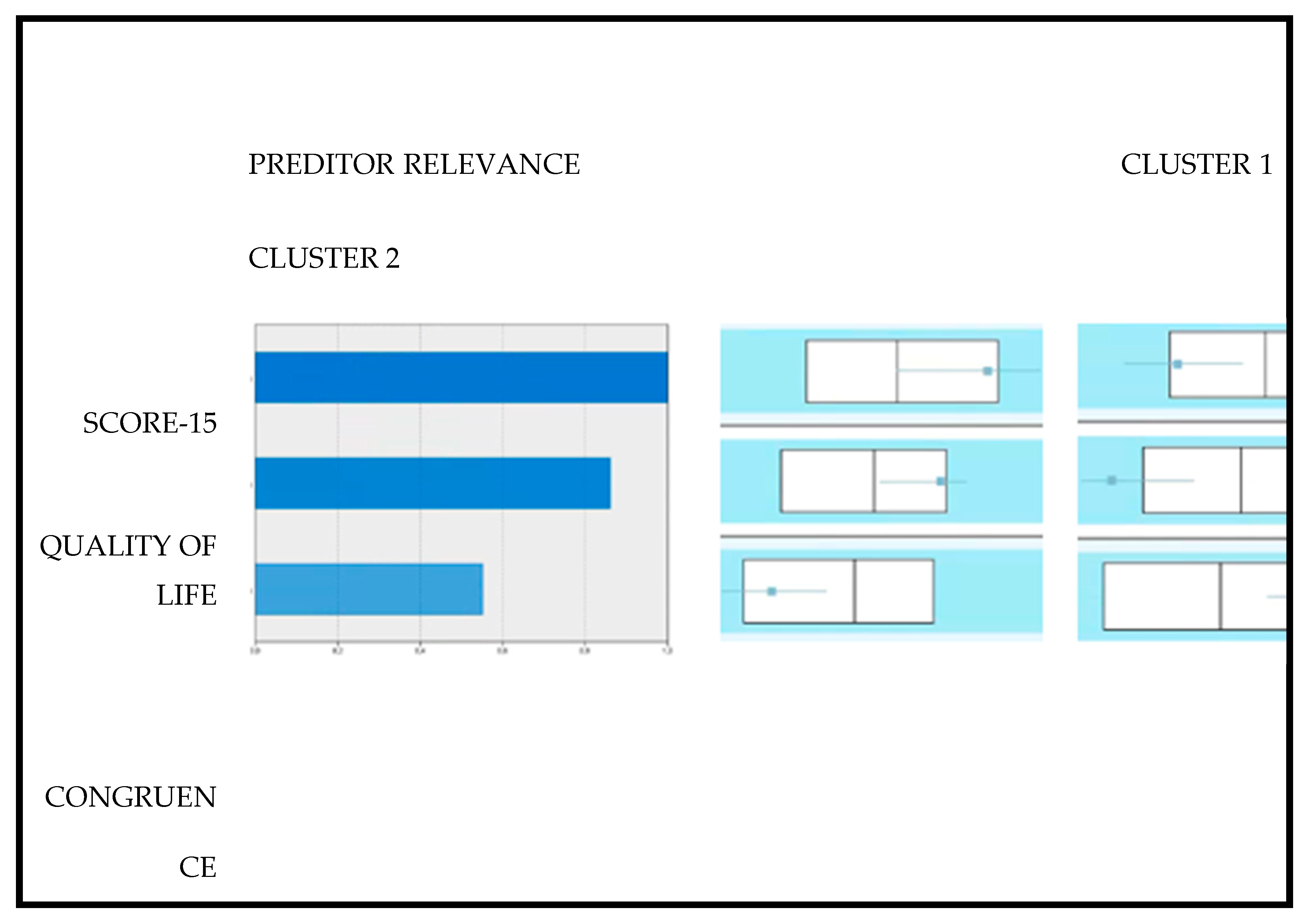

- 1.

- Two cluster solution and metabolic control bipartition

- 2.

- From Family to Diabetes Management

- 3.

- From the Demands of Diabetes to Family Conflict

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maturana, H, Varela, F. A árvore do conhecimento: [The tree of knowledge] (trad.) Jonas Pereira dos Santos. Workshopsy.2015; São Paulo. https://pt.scribd.com/document/56555504/Arvore-Do-Conhecimento-Maturana-e Varela.

- Young-Hyman, D, De Groot, M, Hill-Brigg, F, Gonzalez, J, Hood, K, Peyrot, M. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: A position statement of American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39: 2126-2140. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Lifestyle management: Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019; 42: 46-60. [CrossRef]

- Latham, K. Chronic illness and families. Encyclopedia of Family Studies. 2016; 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E, Carr, A. Systematic review of self-report family assessment measures. Family Process. 2016; 55: 16-30. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D, Donnelly, P, Howe, J, Mumford, T, Campbell, A, Ruddock, A, Wearden, A. A qualitative interview study of people living with well-controlled type 1 diabetes. Psychology & Health. 2018; 33: 872–887. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M, Grey, M. Type 1 diabetes self-management from emerging adulthood through older adulthood. Diabetes Care. 2018; 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Lister, Z, Fox, C, Wilson, C. Couples and diabetes: A 30-year narrative review of dyadic relation research. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2013; 35: 613-638. [CrossRef]

- Steinglass, P, Horan, M. Families and chronic medical illness. In F. Walsh, & C. Anderson. Chronic disorders and the families. New York: The Hayworth Press. 1988; 127-142.

- Melo, A, Alarcão, M. Beyond the family cycle: Understanding family development in the twenty-first century through complexity theories. Family Science. 2014, 5: 55-59. [CrossRef]

- Relvas, A, Major, S. (Coord.). Instrumentos de Avaliação Familiar – Funcionamento e Intervenção (Vol.I) [Family Assessment Instruments–Functioning and Intervention (Vol.I)]. Coimbra, Portugal: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. 2014. https://estudogeral.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/41517/1/Avalia%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20Familiar.pdf.

- Walsh, F. Applying a family resilience framework in training, practice, and research: Mastering the art of the possible. Family Process. 2016; 55: 616-632. [CrossRef]

- Franks, M, Sahin, Z, Seidel, A, Shields, C, Oates, S, Boushey, C. Table for two: Diabetes distress and diet-related interactions of married patients with diabetes and their spouses. Families, Systems, & Health. 2012; 30: 154– 165. [CrossRef]

- Ritholz, M, Beste, M, Edwards, S, Beverly, E, Atakov-Castillo, A, Wolpert, H. Impact of continuous glucose monitoring on diabetes management and marital relationships of adults with type 1 diabetes and their spouses: a qualitative study. Diabetic Medicine. 2014; 31: 47–54. [CrossRef]

- Lister, Z, Wilson, C, Fox, C, Herring, R, Simpson, C, Smith, L. Partner expressed emotion and diabetes management among spouses living with Type 2 diabetes. Families, Systems, & Health. 2016; 34: 424– 428. [CrossRef]

- Litchman, M, Wawrzynski, S, Allen, N, Tracy, E, Kelly, C, Helgeson, et al. Yours, mine, and ours: A qualitative analysis of the impact of type 1 diabetes management in older adult married couples Diabetes Spectrum. 2019; 32: 239-248. [CrossRef]

- Due-Christensen, M, Willaing, I, Ismail, K, Forbes, A. Learning about type 1 diabetes and learning to live with it when diagnoses in adulthood: Two distinct but interrelated psychological processes of adaptation: a qualitative longitudinal study. Diabetic Medicine. 2018 ; 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Metsch, J, Tillil, H, Köbberling, J, Sartory, G. On the relation among psychological distress, diabetes-related health behavior, and level of glycosylated hemoglobin in type 1 diabetes. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1995; 2:104-117. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M, Frier, B, Gold, A, Deary, I. Psychosocial factors and diabetes-related outcomes following diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in adults: The Edinburgh prospective diabetes study. Diabetic Medicine. 2003; 20: 135-146. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S, Epel, E, Sachon, C, Vaillant, G, Hartemann-Heurtier, A. A longitudinal study of coping, anxiety and glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes. Psychology & Health. 2008; 23: 73–89. [CrossRef]

- Watts, S, O’Hara, L, Trigg, R, Living with type 1 diabetes: A by-person qualitative exploration. Psychology & Health. 2010; 25: 491–506. [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, R, Graue, M, Wentzel-Larsen, T, Peyrot, M, Thordarson, H, Rokne, B. Longitudinal relationship between diabetes-specific emotional distress and follow-up HbA1c in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 2015; 32: 1304–1310. [CrossRef]

- De Groot, M, Gold, S, Wagner, S. Psychological conditions in adults with diabetes. American Psychologist. 2016; 71: 552-562. [CrossRef]

- Hessler, D, Fisher, L, Polonsky, W, Strycker, L, Perters, A et al. Diabetes distress is linked with worsening diabetes management over time in adults with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Medicine. 2017. 34: 1228-1234. [CrossRef]

- Anderbro, T, Amsberg, S, Moberg, E, Gonder-Frederick, L, Adamson, U, Lins, E, et al. A longitudinal study of fear of hypoglycaemia in adults with type 1 diabetes. Endocrinology, Diabetes & Metabolism. 2018; 1: 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Dunicheva, M, Zagorovskaya, T., Patrakeeva, E. The role of psychological features in management of patients with type 1 diabetes (case report). Georgian Medicine News. 2018; 67-70. PMID:29745918.

- Rancourt, D, Foster, N, Bollepalli, B, Fitterman, H, Powers, M, Clements, M, Smith, L. Test of the modified dual pathway model of eating disorders in individuals with type 1 diabetes. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2019; 52: 630–642. [CrossRef]

- Trief, P, Sandberg, J, Greenberg, R, Graff, K, Castronova, N, Yoon, M, et al. Describing support: A qualitative study of couples living with diabetes. Families, Systems, & Health. 2003; 21: 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, V, Berg, C, Kelly, C, Van Vleet, M, Zajdel, M, Tracy, E, et al. Patient and partner illness appraisals and health among adults with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2019; 42: 480–492. [CrossRef]

- Hill, K, Ward, P, Gleadle, J. "I kind of gave up on it after a while, became too hard, closed my eyes, didn't want to know about it"-adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus describe defeat in the context of low social support. Health Expectations. 2018; 22: 254-261. [CrossRef]

- Roberson, P, Fincham, F. Is relationship quality linked to diabetes risk and management? It depends on what you look at. Families, Systems, & Health. 2018; 36: 315-326.

- Karlsen, B, Bru, E. Coping styles among adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2002; 7: 245–259. [CrossRef]

- Wearden, A, Ward, J, Barrowclough, C, Tarrier, N. Attributions for negative events in the partners of adults with type 1 diabetes: Associations with partners’ expressed emotion and marital adjustment. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2006, 11: 1– 21. [CrossRef]

- Schokker, M, Links, T, Bouma, J, Keers, J, Sanderman, R, Wolffenbuttel, B. The role of overprotection by the partner in coping with diabetes: A moderated mediation model. Psychology & Health. 2011; 26: 95– 111. [CrossRef]

- Peyrot, M, Rubin, R, Lauritzen, T, Snoek, F, Matthews, D, Skovlund, S. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: results of the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabetic Medicine: a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2005; 22: 1379–1385. [CrossRef]

- Ridge, K, Treasure, J, Forbes, A, Thomas, S, Ismail, K. Themes elicited during motivational interviewing to improve glycaemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus, Diabetic Medicine. 2011; 29: 148-152. [CrossRef]

- Spek, V, Nefs, G, Mommersteeg, P, Speight, J, Pouwer, F, Denollet, J. Type D personality and social relations in adults with diabetes: results from diabetes MILES - The Netherlands. Psychology & Health. 2018; 33: 1456–1471. [CrossRef]

- White, P, Smith, S, O’Dowd, T. The role of the family in adult chronic Illness: A review of the literature on type 2 diabetes. The Irish Journal of Psychology. 2005; 26: 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Rintala, T, Paavilainen, P, Åstedt-Kurki, D. Everyday life of a family with diabetes as described by adults with type 1 diabetes. European Diabetes Nursing. 2013; 10: 86-90. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A, Hauser, S, Cole, C, Willett, J, Wolfsdorf, J, Dvorak, R, et al. Social relationships among young adults with Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Ten-year follow-up of an onset cohort. Diabetic Medicine. 1997; 14: 73-79. [CrossRef]

- Pinhas-Hamiel, O, Tish, E, Levek, N, Bem-David, R, Graf-Bar-El, C, Yaron, M, et al. Sexual lifestyle among young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metabolism Research and Review. 2010; 33: 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Palladino, D, Helgeson, V, Reynolds, K, Becker, D, Siminerio, L, Escobar, O. Emerging adults with type 1 diabetes: A comparison to peers without diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2013; 38: 506-517. [CrossRef]

- Schabert, J, Browne, J, Mosely, K, Speight, J. Social stigma in diabetes. The Patient-Patient Centered Outcomes Research. 2013; 6: 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, V, Mascatelli, K, Reynolds, K, Becker, D, Escobar, O, Siminerio, L. Friendship and romantic relationships among emerging adults with and without type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015; 40: 359–372. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J, Maryniuk, M. Building therapeutic relationships: Choosing words that put people first. Clinical Diabetes Journals. 2017 ; 35: 51-54. [CrossRef]

- López-Larrosa, S. Quality of life, treatment adherence, and locus of control: Multiple family groups for chronic medical illness. Family Process. 2013; 52:, 685-696. [CrossRef]

- Baig, A, Benitez, A, Quinn, M, Burnet, D. Family interventions to improve diabetes outcomes for adults. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2015; 1353: 89-112. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. Families living well with chronic illness: The healing process of moving on. Chronicity, 2017; 27: 447-461. [CrossRef]

- Martire, L, Helgeson, V. Close relationships and management of chronic illness: Associations and interventions. American Psychologist. 2017; 72: 601-612. [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. The Biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1978; 310: 169–181. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Health and behavior: The interplay of biological, behavioral, and societal influences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Morin, E. Introdução ao pensamento complexo. (4th ed.). Epistemologia e Sociedade: Instituto Piaget. 2003.

- Rolland, J. Chronic illness and the life cycle: A conceptual framework. Family Process. 1987; 26: 203-221. [CrossRef]

- Rolland, J. Families, illness, and disability: An integrative treatment model. New York, Basic Books.1994.

- Rolland, J. Mastering family challenges in serious illness and disability. In F. Walsh. (4th ed.). Normal Family Process. 2012; 452-482. New-York, N.Y.: Guildford Press.

- White, M, Epston, D. Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: W. W. Norton. 1990.

- Rolland, J. A family psychosocial map with chronic conditions. In J. Rolland. Helping couples and families navigate illness and disability: An integrated approach. 2018; 3-18. New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

- Anderson, R, Freelan, K, Clouse, R, & Lustman, P (2001). The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care; 2001. 24: 1069-1078. [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. Escala de inteligência de Wechsler para adultos-Terceira Edição (WAIS-III [WAIS- Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (3rd. Ed.)]. Adaption, validation and normative study for Portuguese population by C. Ferreira, M. Machado, & A. Rocha. Lisbon: Cegoc. 2008.

- Raven, J, Raven, J, Court, J. Matrizes Progressivas Coloridas de Raven, CPM-P. Lisboa: Cegoc. 2009.

- Freitas, S, Simões, M, Alves, L, Santana, I. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): Normative study for the portuguese population. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011; 33: 989-996. [CrossRef]

- Narciso, I, Costa, M. Amores Satisfeitos, mas não perfeitos [Pleased but not perfect loves]. Cadernos de Consulta Psicológica. 1996; 12: 115-130. https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/15550.

- Lee, B. Development of a congruence scale based on the Satir model. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2002; 24: 217-239. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D, Silva, J, Relvas, A. Congruence scale (CS). In A.P. Relvas & S. Major (Coord.), Instrumentos de Avaliação Familiar – Funcionamento e Intervenção (Vol. I) [Family Assessment Instruments – Functioning and Intervention (Vol. I)] (pp. 23–41). Coimbra, Portugal: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.2014 https://estudogeral.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/41517/1/Avalia%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20Familiar.pdf.

- Wretman, C. Saving Satir: Contemporary perspectives on the change process model. Social Work. 2015; 61: 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. Spiritual diversity: Multifaith perspectives in family therapy. Family Process. 2010. 49: 330-348. [CrossRef]

- Stratton, P, Bland, J, Janes, E, Lask, J. (2010). Developing an indicator of family function and a practicable outcome measure for systemic family and couple therapy: The SCORE. Journal of Family Therapy. 2010; 32: 232–258. [CrossRef]

- Vilaça, M, Silva, J, Relvas, A. Systemic clinical outcome routine evaluation (SCORE-15). In A. P. Relvas & S. Major (Coord.), Instrumentos de Avaliação Familiar – Funcionamento e Intervenção (Vol. I) [Family Assessment Instruments – Functioning and Intervention (Vol. I)] (pp. 23–41). Coimbra, Portugal: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. 2014. https://estudogeral.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/41517/1/Avalia%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20Familiar.pdf.

- Simões, J. Qualidade de vida. Estudo de validação para a população portuguesa. [Quality of life: Validation study for Portuguese population] (No published thesis master). Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences: University of Coimbra. 2008 https://estudogeral.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/17369/3/Joana%20Sim%c3%b5es.pdf.

- Paddison, C. Family support and conflict among adults with type 2 diabetes. European Diabetes Nursing. 2010; 7: 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Lewin, A., Geffken, G., Heidgerken, A., Duke, D. , Novoa, W., Williams, L., Storch, E. The diabetes family behavior checklist: A psychometric evaluation. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2005; 12: 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T, Frijters, J , Bergers, G, Defares, P. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1986; 5: 295–315. [CrossRef]

- Viana, V, Sinde, S. Estilo alimentar: adaptação e validação do questionário holandês do comportamento alimentar [Eating style: adaptation and validation of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire]. Psicologia: Teoria, Investigação e Prática. 2003. 8: 59-71. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236649218_ESTILO_ALIMENTAR_Adaptacao_e_validacao_do_Questionario_Holandes_do_Comportamento_Alimentar.

- Ghasemi, A, Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. International Journal of Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2012; 10: 486-489.

- Kos, A, Psenicka, C. Measuring cluster similarity across methods. Psychological Reports. 2000; 86: 858-862. [CrossRef]

- Maroco, J. Análise estatística com utilização do SPSS [Statistical analysis using SPSS] (3rd ed.). Lisboa: Edições Sílabo. 2007.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992; 1: 98–101. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L. Research on the family and chronic disease among adults: Major trends and directions. Families, Systems & Health. 2006; 24: 373– 380. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, G, Cunha, D, Crespo, C, Relvas, A. Families in the context of macroeconomic crises: A systematic review. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016; 30: 687-697. [CrossRef]

- Broadley, M, Bishop, T, M, Andrew, B. The relationship between attentional bias to food and disordered eating in females with type 1 diabetes. Appetite. 2019; 140: 269-276. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, L, McCaul, K, Glasgow, R. (1986). Supportive and nonsupportive family behaviors: relationships to adherence and metabolic Control in persons with type I diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1986. 9: 179–185. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A, Samson, J, Weinger, K, Ryan, C. Diabetes, the brain, and behavior: Is there a biological mechanism underlying the association between diabetes and depression? Glucose Metabolism in the Brain. 2002; 455–479. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M, Pedras, S, Machado, J. Family variables as moderators between beliefs towards medicines and adherence to self-care behaviors and medication in type 2 diabetes. Families, Systems, & Health. 2014; 32: 198-206. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Understanding diabetes and the role of psychology in its prevention and treatment. American Psychologist. 2016; 71: 515-525. [CrossRef]

- Jonhson, S. Increasing psychology`s role in health research and health care. American Psychologist. 2013; 311-321. [CrossRef]

- Jonhson, S, Marrero, D. Innovations in healthcare delivery and policy: Implications for the role of the psychologist in preventing and treating diabetes. American Psychologist. 2016; 71: 628-637. [CrossRef]

| Variables |

MC (N=49) |

NoMC (N=42) | X2 | t | U | gl | p | d |

| Gender (males/females) | 31/18 | 25/17 | 0.134 | ----- | ----- | ----- | 0.824 | 0.07 |

| Age (in years) | 37.20 (9.47) | 36.19 (8.67) | ----- | 0.529 | ----- | 89 | 0.59 | -0.11 |

| Marital Status (Single/Couple) | 22/27 | 24/18 | 1.367 | ----- | ----- | 1 | 0.244 | 0.07 |

| Members of the Household (1/2/3)** | 17/28/3 | 16/21/5 | 1.695 | ----- | ----- | 1 | 0.428 | 0.08 |

| Household income B (1/2) | 33/15 | 16/26 | 8.94 | ----- | ----- | 1 | 0.003 | 0.66 |

| Residence (1/2/3) | 20/12/16 | 16/17/9 | 2.97 | ----- | ----- | 2 | 0.226 | 0.36 |

| Area of Residence (1/2/3) | 38/8/3 | 28/8/6 | 1.98 | ----- | ----- | 2 | 0.372 | 0.06 |

| Educational level* (1/2) | 17/32 | 27/15 | 7.93 | ----- | ----- | 1 | 0.005 | 0.61 |

| Vocabulary | 32.33 (3.47) | 33.60 (2.81) | ----- | ----- | 807 | ----- | 0.075 | 0.034 |

| Digit Memory | 14.73(2.08) | 14.10 (1.92) | ----- | ----- | 1273 | ----- | 0.05 | 0.416 |

| RPMT | 8.04(0.90) | 8.05 (1.01) | ----- | ----- | 981 | ----- | 0.688 | 0.08 |

| Disease onset (<18;>18 years) | 24/25 | 24/18 | 0.605 | ------- | ------ | 1 | 0.382 | 0.16 |

| Dealing Time with Disease | 17.56 (10.38) | 17.21 (9.58) | ------- | -0.161 | ------ | 89 | 0.870 | -0.034 |

| HbA1c | 7.19 (0.65) | 8.52 (1.22) | ------- | 6.329 | ---------- | 89 | <0.001*** | 0.07 |

| BMI | 24.95 (3.31) | 25.20 (3.81) | ------ | ------- | 989 | ---- | 0.750 | 0.067 |

| Complications (Yes/No) | 21/28 | 30/12 | 7.94 | ------ | ------- | 1 | 0.006** | 0.62 |

| Smoking status (Yes/No) | 11/38 | 7/35 | 0.48 | ------ | ------- | 1 | 0.49 | 0.14 |

| Variables | Participants with MC (n=49) | Participants with NoMC (n=42) | U | t | gl | p | d | ||||||||

| M | SD | 1stQ | 2ndQ | 3rdQ | M | SD | 1stQ | 2ndQ | 3rdQ | ||||||

| SCORE-15 | |||||||||||||||

| Family Strengths | 1.65 | 0.64 | 1.40 | 1.80 | 2.13 | 1.86 | 0.65 | 1.20 | 1.40 | 2.00 | 1141.5 | --- | -- | 0.002 | 0.33 |

| Family Difficulties | 1.63 | 0.60 | 1.80 | 2.60 | 2.85 | 2.43 | 0.71 | 1.20 | 1.60 | 2.00 | 411 | --- | -- | <0.001 | 1.22 |

| Family Communication | 1.87 | 0.65 | 2.20 | 2.80 | 3.20 | 2.68 | 0.74 | 1.40 | 1.80 | 2.15 | 423 | --- | -- | <0.001 | 1.16 |

| CONGRUENCE SCALE | |||||||||||||||

| Intra/Interpersonal | 48.57 | 7.37 | 45.50 | 50.00 | 53.50 | 42.81 | 8.33 | 37.75 | 42.00 | 48.00 | 1495.5 | --- | -- | <0.001 | -0.73 |

| Universal Congruence | 33.76 | 10.78 | 28.50 | 35.00 | 42.00 | 25.45 | 9.25 | 17.00 | 25.00 | 32.00 | 1504 | --- | -- | <0.001 | -0.83 |

| QUALITY OF LIFE Scale | |||||||||||||||

| Financial | 22.37 | 4.81 | 19.00 | 22.00 | 27.00 | 19.07 | 4.34 | 16.00 | 19.00 | 22.00 | 1430.5 | --- | -- | <0.001 | -0.72 |

| Time | 12.43 | 2.98 | 11.00 | 13.00 | 15.00 | 11.57 | 2.08 | 10.00 | 11.50 | 13.00 | --- | -1.56 | 89 | 0.120 | -0.33 |

| Neighborhood | 20.35 | 3.74 | 18.00 | 20.00 | 23.00 | 18.33 | 3.33 | 16.00 | 18.00 | 21.00 | --- | -2.69 | 89 | 0.009 | -0.57 |

| Home Conditions | 18.22 | 3.32 | 16.00 | 18.00 | 20.00 | 18.33 | 3.06 | 16.00 | 18.50 | 20.25 | --- | 0.16 | 89 | 0.870 | 0.03 |

| Mass Media | 9.22 | 2.18 | 8.00 | 9.00 | 10.00 | 9.24 | 2.58 | 7.00 | 9.00 | 11.00 | --- | 0.027 | 89 | 0.978 | 0.01 |

| Social/Health Relationships | 14.90 | 2.48 | 14.00 | 15.00 | 16.00 | 12.81 | 2.38 | 11.00 | 13.00 | 14.00 | 1553 | --- | -- | <0.001 | -0.86 |

| Job | 9.90 | 2.73 | 8.50 | 10.00 | 11.50 | 8.62 | 2.19 | 7.00 | 8.00 | 10.00 | --- | 2.44 | 89 | 0.017 | -0.51 |

| Religion | 6.39 | 1.90 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | 5.05 | 2.28 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 7.00 | 1365 | --- | -- | 0.006 | -0.64 |

| Family/Marital | 8.24 | 1.70 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 10.00 | 6.95 | 1.89 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 8.00 | 1447.5 | --- | -- | 0.001 | -0.72 |

| Children | 6.94 | 2.18 | 5.00 | 7.00 | 9.00 | 7.00 | 2.07 | 5.00 | 7.50 | 8.25 | 1026 | --- | -- | 0.981 | 0.03 |

| Education | 7.49 | 1.48 | 7.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 6.40 | 1.49 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | 1411.5 | --- | -- | 0.002 | -0.73 |

| Variables | Binary Logistic Regression for NoMC | |||||

| B | Exp(B) | 95%IC | p | |||

| Sociodemographic data | ||||||

| Income | -1.22 | 0.29 | 0.12-0.74 | 0.009 | ||

| Level of education | -1.29 | 0.27 | 0.11-0.68 | 0.005 | ||

| Clinical Features | ||||||

| HbA1c Values | 1.73 | 5.62 | 2.59-12.24 | <0.001 | ||

| Family Systems | ||||||

| SCORE-15 | 1.43 | 4.17 | 1.15-11.27 | 0.005 | ||

| ECongruence | -0,05 | 0.96 | 0.92-0.99 | 0.01 | ||

| Eating Behavior | ||||||

| Emotional Ingestion | 0..69 | 2.27 | 1.24-4.13 | 0.008 | ||

| Variables | Couples with MC (n=27) | Couples NoMC (n=18) | U | p | d | ||||||||

| M | SD | 1stQ | 2ndQ | 3rdQ | M | SD | 1stQ | 2ndQ | 3trQ | ||||

| MARITAL FUNCTIONING | |||||||||||||

| Total | 3.86 | 0.78 | 3.40 | 3.80 | 4.35 | 2.88 | 0.63 | 2.25 | 2.77 | 3.45 | 406 | <0.001 | 1.21 |

| FF | 4.76 | 1.09 | 3.75 | 4.75 | 6.00 | 3.61 | 1.03 | 2.50 | 3.35 | 4.50 | 376.5 | 0.002 | 1.29 |

| FT | 3.97 | 1.16 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 2.94 | 0.92 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.63 | 365.5 | 0.004 | 1.33 |

| AUT | 3.95 | 1.03 | 4.00 | 4.75 | 5.50 | 4.76 | 0.86 | 3.00 | 3.75 | 4.75 | 353 | 0.010 | 1.36 |

| EFR | 3.75 | 0.88 | 4.30 | 4.75 | 6.00 | 4.95 | 0.84 | 3.00 | 3.63 | 4.17 | 408 | <0.001 | 1.21 |

| CC | 3.56 | 1.02 | 4.52 | 5.00 | 5.70 | 4.91 | 1.05 | 3.00 | 3.14 | 4.53 | 400 | <0.001 | 1.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).