1. Introduction

The giant salamander (

Andrias davidianus) is the world's largest extant amphibian endemic to mainland China [

1]. Andrias possess a wrinkled, lax dermal structure for oxygen absorption through the skin, which is essential given their diminished eyesight and reliance on sensory nodes to perceive aquatic vibrations. The skin of

Andrias davidianus not only supports respiration, immune defence, and environmental sensing, but also produces secretions rich in bioactive compounds with physiological and defensive roles, including antimicrobial, toxic, and adhesive properties, as well as wound-healing potential, making it a promising source for medical adhesive applications [

1,

2].

While they were once broadly distributed across central and southwestern regions of China, their current geographic range has become fragmented, primarily attributable to habitat degradation and anthropogenic interference [

2,

3,

4]. As breeding technology advances, the scale of giant salamanders grows, and research on active compounds becomes increasingly commercial importance. Currently, most research on bioactive substances from Giant salamanders are peptides, which exhibit a range of beneficial activities, including antioxidant, antibacterial, immunomodulatory, and gut flora-regulating properties [

5,

6]. Peptides isolated from the European fire salamander (

Salamandra salamandra) Salamandrin-I, demonstrated antioxidant properties by scavenging DPPH and ABTS radicals [

6,

7]. A study by Wang et al. investigated improving the antioxidant activity of giant salamander (

Andrias davidianus) peptides through Maillard reaction products with glucose [

5]. Salamandrin-I was found to have potential anticancer effects on the human leukaemia cell line HL-60. It induced cell cycle arrest, reduced cell proliferation, and increased cell death, possibly through pyroptosis [

6]. Meng et al., 2013 identified and characterize an antimicrobial peptide in salamander skin secretions, specifically from

Cynops fudingensis. Salamander skin peptides have been reported to promote wound healing [

9]. The unique adaptations of salamanders make their skin secretions a promising source for novel bioactive compounds with potential therapeutic applications.

Another less-studied bioactive product from salamander - salamander oil, valued as a functional fat. Salamander oil is mainly obtained from the liver and tail oil with a high content of polyunsaturated fatty acids, and consumption of salamander oil can prevent cardiovascular diseases and lower blood lipids [

10]. Rich in unsaturated fatty acids, antioxidants, and antimicrobial components, salamander oil, salamander oil has demonstrated the potential of multiple medicinal functions, including strong antioxidant and antibacterial activities with the peptide mixed from another component [

11]. It has been formulated into products for various health benefits, such as blended oils rich in omega-3 fatty acids and soft capsules that support cardiovascular health. CGS oil creams have shown promising effects in promoting wound healing and reducing recovery time for burns and frostbite [

10,

11,

12]. Despite its unique qualities, giant salamander oil remains underutilized. Its composition varies significantly depending on the feed, which differs across regions such as Shaanxi, Hunan, and Hubei, indicating that feed control could be an effective approach to influencing its nutritional profile. Conducting in-depth research on the composition and mechanisms of action of salamander oil could support the development of new health supplements and medicinal products, driving innovations in precision nutrition and functional foods. Additionally, studying the lipid composition, metabolic pathways, and bioactive mechanisms of salamander oil presents scientists with valuable research opportunities to deepen our understanding of amphibian metabolism and lipid biology.

In recent years, with the continuous development of systems biology methods for bioinformatics data analysis and other related histology platforms, lipidomics has become an important tool for food science and nutrition research, which focuses on lipid molecules and their functions in biological systems [

13,

14]. The lipid composition of food products can provide real and valuable application information. Lipidomics can also be used to determine the effects of processing and storage on the lipid composition of food products, providing important references for quality control and product development in the food industry [

14,

15]. Animal species, location, sex, and rearing environment all affect the lipid composition of meat products, so lipidomics analysis of meat products provides a new approach to exploring their nutritional properties [

16]. Utilizing advanced techniques like UPLC-HRMS and GC-MS, coupled with powerful statistical tools such as PCA and PLS-DA, lipidomics provides a high-throughput platform for understanding and optimizing meat product quality and health benefits [

16,

17].

In this study, an untargeted lipidomics strategy was applied for the first time to analyze the lipid characteristics of the Chinese giant salamander. We first extracted the refined giant salamander oil and later assessed lipid content, classes, fatty acid composition, and major molecular species in giant salamander oil comparing from three areas in China, refining these insights through advanced lipid profiling techniques. This research offers valuable insights into the bioactive lipid components of the species, enhancing our understanding of its nutritional and medicinal potential.

2. Results

2.1. Lipid Components in Giant Salamander Oil Shows Therapeutic Potential

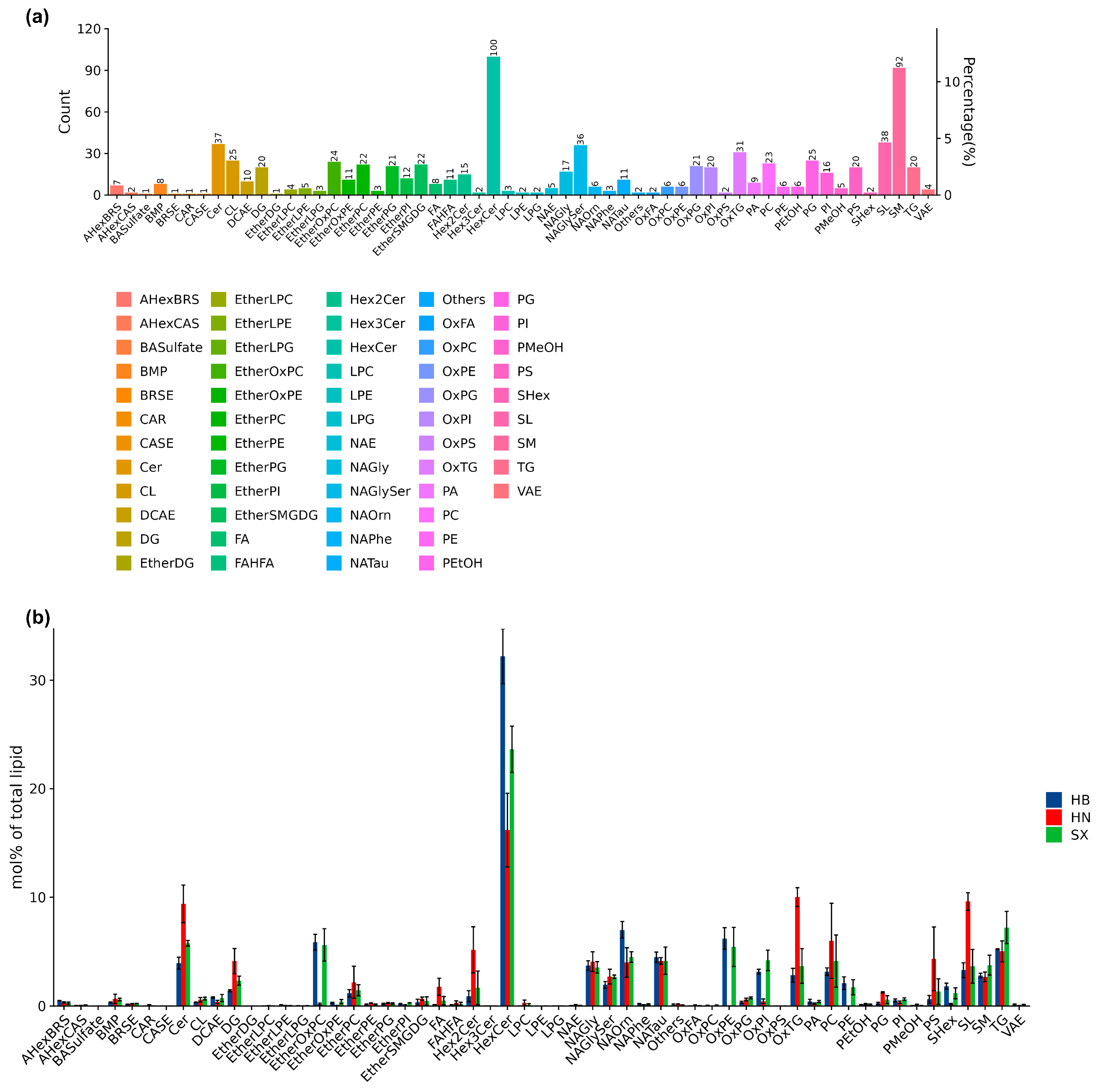

The functional analysis of lipid components in giant salamander oil highlights the diverse bioactive potential of its lipid profile. We identified 818 lipid molecules across 57 subclasses in this study. HexCer (hexosylceramide) is notably abundant within 100 species, accounting for 18.33% of the total lipid content, along with substantial amounts of sphingomyelin (SM, 9.17%) and various ether phospholipids, which underscores its potential bioactivity. Additionally, lipid classes like OxTG and OxPE containing oxidized fatty acid derivatives suggest antioxidant properties, which may offer neuroprotective benefits and potential therapeutic applications [

10,

18,

19]. PCA, PLS-DA, and OPLS-DA were employed to distinguish metabolic differences among the three groups (HN, HB, and SX). Our results demonstrated clear separation in all three analyses, highlighting distinct lipid profiles and regional variations (

Supplement Figure S1).

The second highly enriched lipid is sphingomyelin (SM). Sphingomyelin (SM), one of sphingolipids, plays a crucial role in regulating various cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses [

20], suggesting Giant salamander oil could have promising therapeutic applications. Glycerophospholipids as a fundamental lipid component, including lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), phosphatidylcholines (PC), and phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) were also abundant. They are also essential for brain function, making up 13-15% of the phospholipids in the human cerebral cortex, suggesting giant salamander oil could be an important supplement support in older adults, potentially influencing cognitive function [

21,

22]. In addition, giant salamander oil contains a high level of ether phospholipids, which have potential neuroprotective and antioxidant properties [

23]. Among neutral lipids, giant salamander oil includes diglycerides (DG), ether-linked diglycerides (EtherDG), oxidized triglycerides (OxTG), and triglycerides (TG), mainly with long-chain unsaturated fatty acids. The composition of TGs prioritizes C8:0, C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1 fatty acids. Unlike the oils from other aquatic products, the TG and DG in the surface oil of Andrias skin found in this study accounted for a small proportion of the total lipids. TG made up 5.24-7.37% of the total lipids, and DG accounted for 1.40-4.49%, significantly lower than in oyster lipids [

24]. In general, the potential of giant salamander oil as an intake supplement is significant.

2.2. Region-Specific Lipid Characteristics in Lipid Composition Analysis of Giant Salamander Oil from Different Regions

As shown in

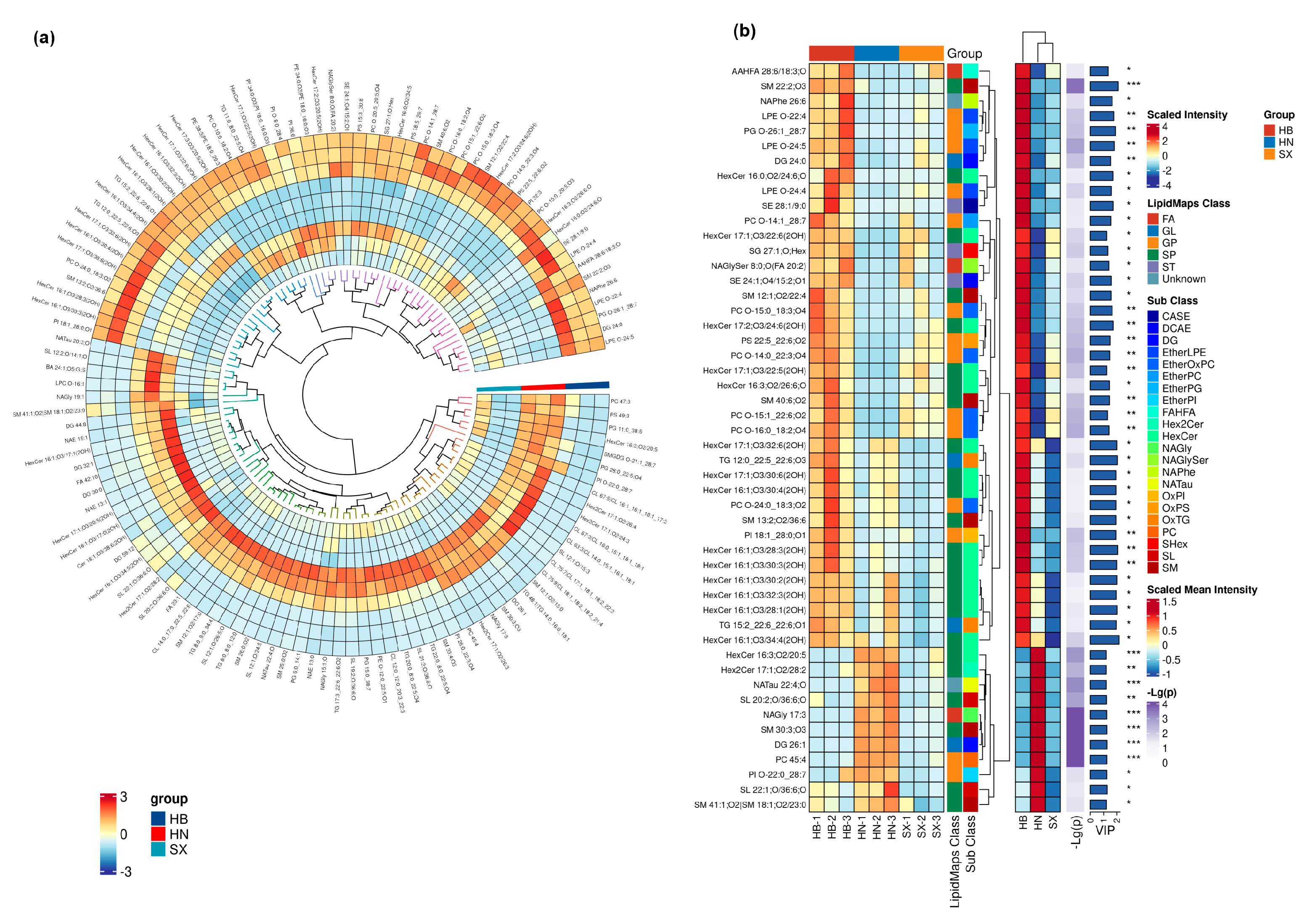

Figure 1b, lipid composition analysis of Giant salamander oil from three regions revealed distinct differences. The heatmap (

Figure 2) illustrates more detailed clustering patterns, indicating significant variations in lipid molecular profiles across the three groups.

In the HB group, HexCer (32.41%) was most abundant, followed by NAOrn (7.01%) and OxPE (6.31%). In HN, HexCer (17.08%) was followed by OxTG (9.95%) and Cer (9.92%), with SL also relatively high (9.53%). In SX, HexCer (24.37%) was followed by TG (7.37%) and EtherOxPC (6.17%). While HB and SX shared similar lipid profiles, HN exhibited lower percentages of EtherOxPC, OxPE, OxPI, PE, and SHex but higher levels of Cer, DG, Hex2Cer, OxTG, PC, PS, and SL. These variations suggest that HB and SX may be more suitable for neuroprotective applications, whereas the HN group's lipid composition may be valuable for studying cellular membrane functions. These results collectively imply that Giant salamander oil contains bioactive lipid species with broad implications for metabolic, immune, and neurological health [

7,

25,

26], positioning it as a promising supplement candidate for functional and therapeutic applications.

Giant salamander oil is rich in phospholipids, with the HB group showing a higher abundance of phospholipids (PC 40:6, PC 40:5, PE 40:4, PS 40:5) and sphingolipids (SM 36:2, HexCer 18:1/18:0, Cer 18:1/18:0), suggesting enhanced membrane fluidity and neurometabolism. The phospholipid composition of HB and SX was similar but significantly different from HN. Specifically, EtherOxPC, OxPE, OxPI, and PE were significantly higher in HB and SX than in HN, whereas LPC, PC, and PG were more abundant in HN. The SX group had the highest percentage of ether phospholipids, making it a potential neuroprotective source. Meanwhile, triglyceride (TG 52:2, TG 50:2) levels were also significantly higher in HB, indicating greater energy reserves. In contrast, SX exhibited generally lower levels of phospholipids, sphingolipids, and triglycerides, reflecting a slower metabolic state. The HN group showed an intermediate lipid composition, with DG (26:1) being more prevalent than in HB and SX, suggesting a transitional metabolic pattern. Additionally, N-acetylglucosamine (NAG 15:0, NAG 14:0), diacylglycerol (DG 30:0, DG 32:0), and free fatty acids (FA 34:1, FA 30:0) were more abundant in HB, reinforcing its higher metabolic activity.

Lipid subgroup analysis further revealed that the HN group had a lower HexCer content (17.08%) but elevated ceramide (9.92%), oxidized triglycerides (OxTG, 9.95%), and saccharolipids (SL, 9.53%). In contrast, HB was characterized by a dominant HexCer proportion (32.41%), along with elevated N-Acyl Ornithine (NAOrn, 7.01%) and oxidized phosphatidylethanolamine (OxPE, 6.31%). SX stood out for its ether phospholipid enrichment, particularly EtherOxPC (6.17%), along with notable levels of HexCer (24.37%) and TG (7.37%). These distinctions highlight the unique lipid profiles across the three groups and their potential functional implications.

Overall, giant salamanders in the HB group showed stronger energy reserves and metabolic activity in lipid metabolism, while the SX group was relatively lower. These results suggest that salamanders from different regions may develop different patterns in lipid metabolism due to differences in environmental adaptations or physiological requirements. These changes in key lipid classes may provide important references for further studies on the adaptation mechanisms of the giant salamander.

2.3. HN Group Is Ideal for Functional Benefits, While the SX Group Oil Is More Suitable for General Dietary Purposes

Key polyunsaturated fatty acids include ω-3 and ω-6, which are conducive to human health [

11]. Given the increasing interest in the nutritional benefits of various dietary fats, it is essential to evaluate the fatty acid composition of the Chinese giant salamander (

Andrias davidianus) from different geographical locations. Previous research reported that high-fat content is concentrated in the tail and subcutaneous abdominal regions of Andrias. Andrias muscle contains 13 fatty acids, with 75.91% being unsaturated, including a high ratio of monounsaturated (46.69%) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (29.22%). The unsaturated-to-saturated fatty acid ratio is notably high at 3.15, surpassing that of common meats and seafood. Variations in environmental conditions, diet, and habitat can influence the lipid profiles of these salamanders, potentially affecting their health benefits and market value. By comparing samples from three distinct regions of China, we can gain insights into how location impacts the nutritional quality of salamander oil and identify which source provides the highest levels of beneficial fatty acids.

Through the analysis of fatty acid composition in the oils of the giant salamander from three different regions, as shown in

Table 1, a total of 19 fatty acids were detected in the HB and SX groups, while the HN group showed 20 fatty acids, with the additional fatty acid being C12:0.

Supplement Figure S13D plot represents a Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) of lipid profiles for three groups: HB (circles), HN (squares), and SX (triangles). The three axes (t1, t2, and t3) represent the primary components extracted by PLS-DA, which explain 38%, 11.1%, and 21.8% of the variation, respectively. From the distribution, we observe that the HN group (red squares) forms a distinct cluster, separated from HB (blue circles) and SX (blue-green triangles), indicating that HN samples have a unique lipid composition. HB and SX show more overlap, suggesting similarities in their lipid profiles. This separation implies that the lipid composition varies significantly between these groups, potentially due to differences in factors such as diet or geographical environment.

For functional benefits, the HN group is the ideal option, while for general dietary purposes, the SX group oil may be the most suitable. From

Table 1, we noticed HN Among the saturated fatty acids, C16:0 had the highest content, with the HB group having the highest content, followed by the SX and HN groups. For monounsaturated fatty acids, C18:1n9c had the highest content. In the case of polyunsaturated fatty acids, C20:4n6 was the most abundant, with a content ranging from 1.4843 to 1.5976 g/100g. Additionally, the contents of C18:0, C16:1, and C18:1n9c exceeded 1 g/100g in all three groups. Consistent with other studies on the fatty acids of the giant salamander, this study shows that the oil contains a rich array of unsaturated fatty acids, with unsaturated fatty acid content ranging from 65.52% to 67.88% [

3,

10]. This is higher than that of grass carp oil (61.08%), sardine oil (60.60%), and tilapia oil (63.31%) [

27,

28,

29]. The HN group had the highest unsaturated fatty acid content (67.88%), followed by the HB group (65.62%) and the SX group (65.52%). Although the fatty acid compositions of the three groups of giant salamander oil were generally similar, the contents of each fatty acid varied. For EPA and DHA, which have clear health benefits, while the EPA content in giant salamander oil is relatively low, the levels of EPA and DHA in the HN group were significantly higher than in the other two groups. Moreover, the contents of C16:1, C18:3n3, and C20:3n6 in the HN group were also significantly higher than those in the other two groups, indicating that the giant salamander oil from the HN group may be an ideal source of functional fatty acids. Regarding the ratio of ω-6 to ω-3 fatty acids, the ratio in the SX group giant salamander oil was 2.4308:1, which is closer to the optimal intake ratio of 2.3:1 recommended by American experts. This suggests that among the three groups of giant salamander oil, the oil from the SX group may be the best choice for daily dietary consumption.

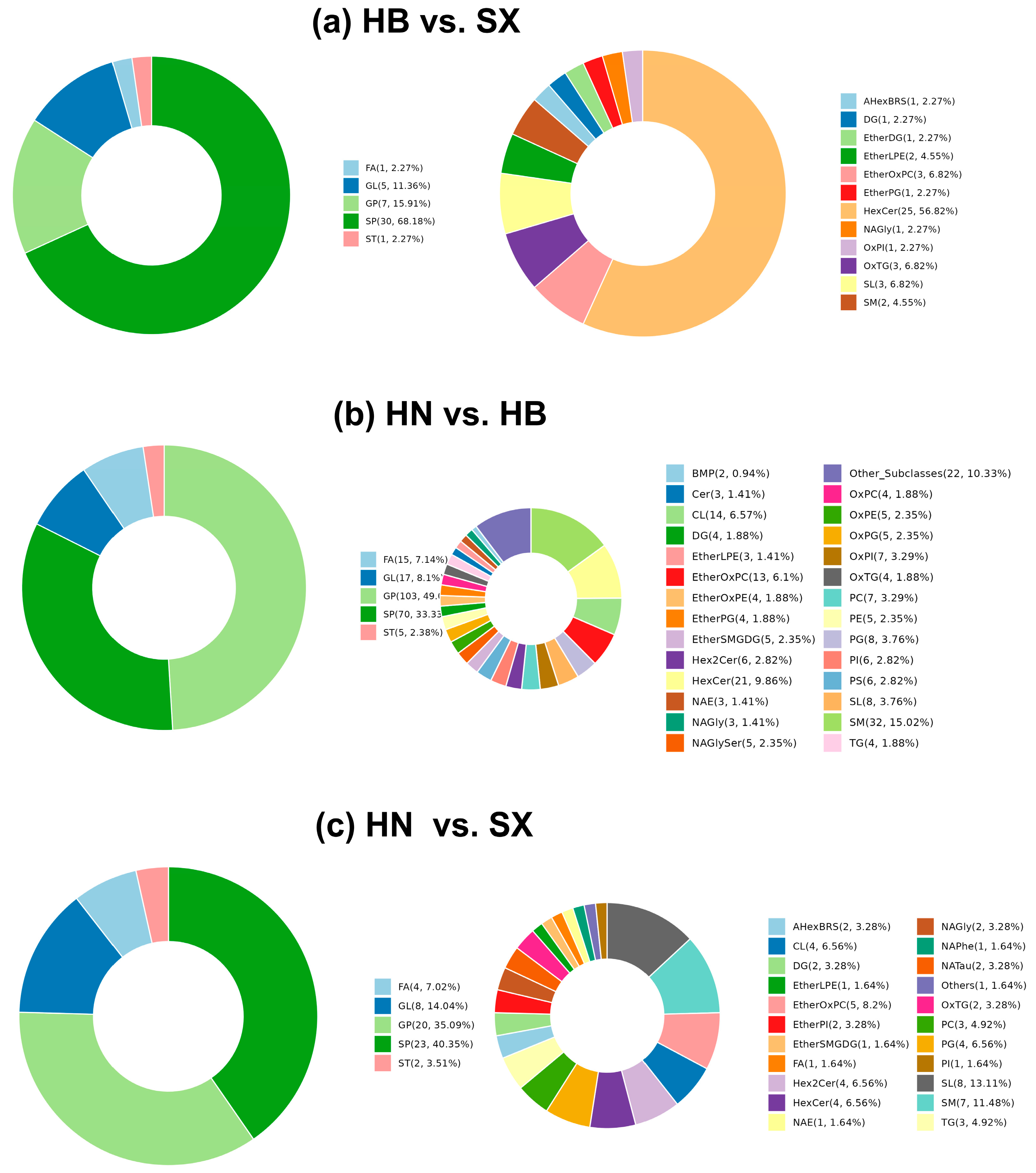

2.4. Lipidomic Analysis Present That Sphingolipids and Glycerophospholipids Were the Main Differential Lipids Distinguishing the Salamanders of HB, HN and SX

In this study, we used hierarchical clustering analysis was conducted to reveal lipid composition differences among oils from the HB, SX, and HN groups of Andrias. HB group showed significantly higher abundance of several lipid metabolites than the SX group, while the HN group showed an intermediate state (

Figure 3).

Lipidomic analysis revealed significant differences in the composition of salamander skin lipids in different regions. Among them, 44 significantly different lipids were detected in the comparison group of HB and SX, all of which were up-regulated, mainly sphingolipids (HexCer), including 25 kinds of HexCer, 3 kinds of SL, and 2 kinds of SM, with TG12:0_22:5_22:6;O3 being the most significant, and SM22:2;O3 the most significant. 215 significantly different lipids were detected in the comparison group of HN and HB, including 32 kinds of SM, 21 kinds of HexCer, 14 kinds of CL, and 13 kinds of EtherOxPC, among which TG12:0_22:5_22:6;O3 was the most significant. In the comparison group of HN and HB, 215 significantly different lipids were detected, including 32 SMs, 21 HexCers, 14 CLs and 13 EtherOxPCs, among which CL67:5|CL16:1_16:1_18:1_17:2 was the most different, and the expression of DG26:1 was the most significantly up-regulated. In the SX vs. HN group, the 61 significantly different lipids were mainly sphingolipids (SL, SM) and glycerophospholipids (EtherOxPC), with PIO-8:0_28:4 being the most different, PCO-14:0_22:3;O4 being the most significantly expressed, and SL12:2;O/14:1;O being the most differently down-regulated lipid. Further clustering and correlation analyses showed that these lipid molecules showed distinct geographical characteristics in the skin oils of salamanders from different regions, with sphingolipids (e.g., HexCer and SM) and glycerophospholipids (e.g., EtherOxPC and CL) being the main differentiating lipids in the oils of salamanders from Hubei, Hunan, and Shaanxi, which have potential significance as landmarks.HB and SX groups share similar profiles for certain oxidized lipids, such as OxPE and OxPI, while the HN group exhibits comparatively lower levels of these lipids, along with a higher percentage of phosphatidylcholines (PC), lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), and phosphatidylglycerols (PG). These lipids play important roles in membrane stability, signal transduction, and metabolic functions [

30,

31,

32]. Therefore, the lipid composition of the HN group may be more beneficial for cell membrane health and functional metabolic processes. Such distinct lipidomic profiles highlight the potential for targeted applications of HB Giant salamander oils based on specific bioactive components.

Moreover, ether phospholipids, which serve as reservoirs for PUFAs and exhibit potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects, are more concentrated in certain groups, enhancing their health benefits. Unlike typical aquatic oils, Giant salamander oil has a higher proportion of sphingolipids, which play vital roles in regulating the cell cycle and immune responses. Consequently, Giant salamander oil from regions like the SX group may provide a promising source of bioactive sphingolipids and ether phospholipids with applications in health and wellness.

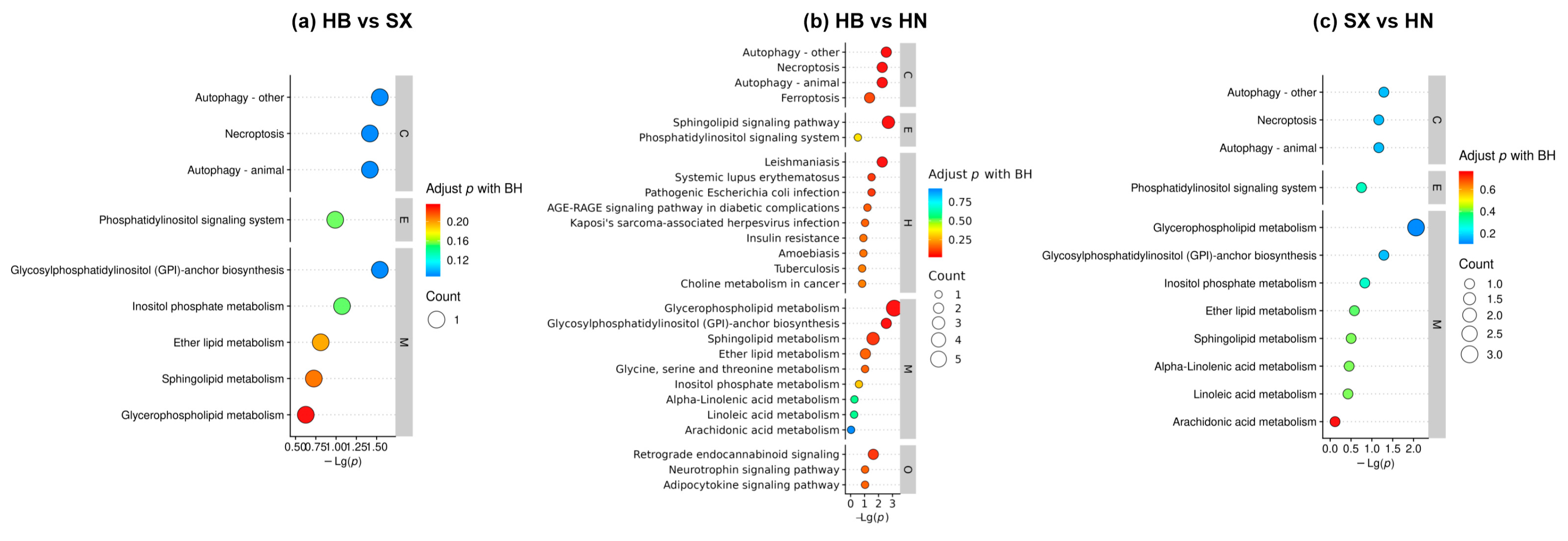

KEGG analysis is used to understand the high-level functions and uses of cells, and organisms, and comprehensively understand the biological process of cells, which will help us to understand the function of metabolites and the relationship between metabolites. Pathway enrichment analysis of differential lipids was performed using the LIPEA tool [

33], and

Figure 4 shows the KEGG enrichment analysis statistics of significantly different lipids. The functions of all lipids encompass several critical processes, including the regulation of cell death through mechanisms such as ferroptosis, necroptosis, and autophagy; the facilitation of cellular stress responses via autophagy and sphingolipid signaling; and the maintenance of cellular homeostasis through the degradation and recycling of cellular components. Additionally, lipids play a vital role in enabling essential signaling pathways through sphingolipid and phosphatidylinositol pathways, contributing to membrane structure and function, and supporting immune responses [

34,

35]. Many of these lipid-related pathways are implicated in various pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and infectious diseases [

22,

26,

36]. In the comparison between the HB and SX groups, 44 lipid molecules were significantly enriched in nine metabolic pathways, with the most significant enrichment observed in glycerophospholipid metabolism, followed by sphingolipid and ether lipid metabolism pathways. All these lipid metabolism pathways play essential roles in maintaining cellular membrane structure, stability, and fluidity. Additionally, ether lipids and certain sphingolipids serve as antioxidants, protecting cells from oxidative stress [

21,

23].

When comparing the HN and HB groups, KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that 215 lipids were enriched across 17 metabolic pathways. The most significant enrichment was found in arachidonic acid metabolism, which was more pronounced than other pathways such as programmed necrosis, autophagy, the phosphatidylinositol signaling system, and sphingolipid metabolism [

37]. In the comparison between the SX and HN groups, 61 significantly different lipids were enriched in 12 metabolic pathways, with arachidonic acid metabolism showing the most significant enrichment, similar to the HN vs. HB comparison. Arachidonic acid metabolism is crucial for inflammation and immune response regulation, cell signalling, cardiovascular function, and brain development [

26]. This collective suggests HN has more significance in drug usage in cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and inflammatory disorders.

3. Discussion

The giant salamander has long held significance in human culture, medicine, and research. Historically, various parts of the giant salamander have been utilized for culinary, medicinal, and even biomedical applications [

11,

38,

39]. From its meat being considered a delicacy to its skin and secretions yielding bioactive compounds, this species has played a versatile role in both traditional and modern contexts. Given its long-standing significance, the giant salamander has been utilized in diverse ways, particularly in culinary traditions and traditional medicine. The giant salamander’s meat is considered a delicacy in Chinese cuisine [

39]. Traditional medicine continues to utilize various parts of the giant salamander. The powdered skin, when combined with tung oil, is believed to have healing properties for burns. The stomach is considered to aid digestion, while the meat is used to treat conditions such as neurasthenia and anemia [

40]. The bones, liver, blood, and tail fat are also incorporated into traditional remedies for their perceived medicinal benefits. [

40].

While traditional medicine has long valued various parts of the giant salamander, modern research has further expanded its potential applications by scientifically validating its bioactive compounds. Bioactive peptides extracted from its skin and secretions yield valuable proteins. They have been found to possess antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticancer, and antidiabetic properties [

5,

6,

8,

41,

42]. As a result, they hold potential applications in both the food and biomedical industries. The mucus from the salamander’s skin glands has also been studied for its notable bioactivity, making it a potential source of functional biological materials[

11]. Additionally, skin waste from the giant salamander serves as an alternative reservoir of collagen[

41,

43]. Among its many uses, giant salamander oil has gained attention for its potential healthcare applications [

12,

44]. As research continues, its promising benefits may lead to further developments in medicine and biotechnology, making it a valuable resource for future innovations.

Beyond its biomedical potential, recent research has also revealed new insights into the taxonomy of the Chinese giant salamander, highlighting the complexity of its genetic diversity across different regions. New research has revealed the complex taxonomy of it. The study shows that the amphibian, once thought to be a single species, may actually contain as many as nine different species, of which at least seven are now recognized as genetically distinct. In the classification of the Chinese giant salamander, scientists have officially named four species, while three to five more species have yet to be officially named and scientifically described. Geographic distribution studies have shown that these different species are distributed in river systems with distinctive characteristics in central and southern China. It is noteworthy that, despite their genetic differences, these giant salamander species are so similar in appearance that they are difficult to distinguish from each other with the naked eye [

45,

46].

Given the genetic diversity and broad geographical distribution of the Chinese giant salamander, it is essential to investigate how environmental factors influence the composition and quality of its oil. This study specifically focuses on the geographical differences in salamander oil to provide insights into optimal cultivation practices and product development. In this paper, we focus on the geographical difference of giant salamander oil in order to provide best cultivation practice information for further products. The giant salamander (Chinese giant salamander) is mainly found in the Yangtze, Yellow and Pearl River Basins and their tributaries, extensively covering many provinces, regions and cities in China. Currently, the distribution of the giant salamander covers 17 provinces including Hunan, Hubei, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Henan, Hebei, Guizhou, Guangxi and Gansu. Some of the typical habitats include Zhangjiajie in Hunan, Shennongjia in Hubei, Hanzhong in Shaanxi, Enshi in Hubei, Liuzhou in Guangxi and Wenxian in Gansu [

47,

48]. These areas have complex terrain and well-developed water systems, providing a suitable environment for the giant salamander to thrive.

Since water quality plays a crucial role in the habitat suitability and nutritional composition of the giant salamander, it is important to analyze regional variations in aquatic conditions across Hunan, Hubei, and Shanxi. The water quality and fish types in the water of these three regions are significantly different. The water quality in the habitat of the giant salamander in all three provinces is likely to be neutral or slightly acidic, for the reason that the giant salamander prefers clear, cold streams. The water quality of Shanxi may be scarce and slightly alkaline because it is located in the Yellow River Basin, where the hydrological condition may be influenced by the Loess Plateau (黄土高原). Hunan and Hubei, as provinces in the Yangtze River basin, they are under pressure from water pollution and are possibly to be less clean.

In addition to water quality, dietary composition is another key environmental factor that influences the lipid profile of giant salamander oil. The primary food sources available in each region vary significantly, shaping the nutritional properties of salamander-derived lipids. Giant salamander in various regions may feed on fish, shrimps, crabs, frogs, snails, mussels, water snakes, small rodents, and aquatic insects, the food resource of these three regions for Andrias may vary. The main diet in Hunan province may consist of juveniles of carp, barbel and bream, Dongting Lake is abundant of lacustrine fishes and crustaceans. The main diet composition in Hubei is dominated by fishes common to the Yangtze River basin, where may have more stream fishes and amphibians. For Andrias in Shanxi Province, carpiformes, hardy fishes and small stream fishes are the main food source [

1,

49,

50,

51].

Among the studied regions, the lipid composition of salamanders from Hunan exhibits unique properties, likely due to its distinctive geographical and climatic conditions. The province’s subtropical monsoon humid climate, abundant rainfall, and karst landscape provide an optimal environment that may influence lipid accumulation in salamanders. The geological and geomorphological types in the Wuling Mountain area are complex, with distinct karst landform characteristics, offering a variety of habitats for Andrias. The typical karst landforms in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, with numerous solution沟, solution槽, and stone shoots, provide abundant hiding and breeding places for Andrias [

52,

53]. Within the Zhangjiajie Andrias National Nature Reserve in Hunan, the water quality is clear, with a high degree of mineralization, rich in calcium, magnesium, and other ions, and the water temperature is suitable, providing an ideal living environment for Andrias. This climatic condition not only benefits the healthy growth of Andrias but also helps to enhance the quality of its oils. Moreover, Hunan's rich water resources, clear water quality, and abundant bait organisms provide superior conditions for the growth and reproduction of Andrias, indicating significant potential for the development of the Andrias industry [

1].

To systematically compare lipid profiles across different geographical regions, this study employed an untargeted lipidomics approach, identifying 818 lipid molecules across 57 subclasses. The results highlight significant differences in lipid composition among salamanders from Hunan, Hubei, and Shanxi, suggesting a strong correlation between environmental factors and lipid metabolism. These findings provide valuable insights into the nutritional potential and geographic traceability of giant salamander oil, laying the groundwork for future applications in health and industry.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Reagents

The materials and reagents used in this study included diethyl ether (National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China), BF₃-methanol (14%, w/w; CNW, China), acetonitrile (Millipore, USA), methanol (Millipore, USA), ammonia solution (Merck, Germany), ammonium acetate (Sigma, USA), formic acid (Millipore, USA), and methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE; Merck, Germany). A mixed standard of 35 fatty acids was sourced from Sigma (USA). For further analyses, giant salamander tail fat was obtained from Zhangjiajie (China) Jinchi Giant Salamander Biotechnology Co., Ltd., while traditional Chinese herbal deodorization sachets were purchased from Nanjing Tongrentang (China). Additional chemicals included papain (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China), vanillin (Macklin, China), petroleum ether (Tianjin Kemio Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China), absolute ethanol and chloroform (Tianjin Fuyu Fine Chemicals Co., Ltd., China), 2-octanol (CATO, China), phosphoric acid (Tianjin Chemical Reagent Third Factory, China), potassium iodide (Tianjin Beichen Fangzheng Reagent Factory, China), sodium thiosulfate (Tianjin Kemio Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China), activated clay (Gongyi Runshen Water Treatment Materials Co., Ltd., China), phenolphthalein (Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory, China), soluble starch (Shandong Siyang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China), and Wijs reagent (National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China).

For instrumentation, the analysis utilized an electronic balance (FA-1004, Shanghai Shunyu Hengping Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., China), several centrifuges including models TGL-16M (Changsha Xiangyi Centrifuge Instrument Co., Ltd., China), 5430R and Centrifuge 5424R (Eppendorf, Germany), and an ultrasonic system (Bioruptor, Diagenode, USA). Concentrations were achieved using a Concentrator plus (Eppendorf, Germany), and UV-Vis spectrophotometric measurements were conducted with the MultiSkan FC (Thermo, USA). Additionally, a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry system (Thermo, USA), ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography (Nexera X2 LC-30AD, Shimadzu, Japan), and mass spectrometer (Q Exactive plus, Thermo Scientific, USA) were employed. For other procedures, a low-temperature freezing centrifuge (GL21M, Changsha Xiangyi Centrifuge Instrument Co., Ltd., China), a rotary evaporator (RE-2000B, Shanghai Yarong Biochemical Instrument Factory, China), a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (370DTGS, Agilent, USA), and a gas chromatography-mass spectrometer (7890B-7000D, Agilent, USA) were used.

4.2. Sample Preparation

We collected each cell sample according to the requirements and then added 400 μl of ice-cold 75% methanol, followed by ice bath sonication for 15 minutes. Next, we added 1 ml of ice-cold MTBE and fully vortexed to ensure thorough mixing. The samples were then placed in a refrigerator at 4°C for rotary mixing for 1 hour. Afterward, we continued ice bath sonication for another 15 minutes, added 250 μl of water, vortexed for 1 minute, and allowed the mixture to stand at room temperature for 10 minutes. We then centrifuged the samples at 4°C at 14,000g for 15 minutes. The upper layer of liquid, which contained the lipid fraction, was collected. For each sample, we took an equal volume of the lipid fraction containing an equivalent number of cells and used a nitrogen blower to volatilize and dry the extract. The individual samples were then re-dissolved in 60 μl of isopropanol/methanol (1/1, v/v), transferred to injection vials, and stored at low temperatures.

For the preparation of quality control (QC) samples, we mixed aliquots from each group of samples to form a pooled QC sample. These QC samples were used to assess the state of the instrument, ensure equilibrium in the chromatography-mass spectrometry system before sampling, and evaluate system stability throughout the experiment.

4.3. Fatty Acid Composition Sample Preparation and Determination

The procurement of the tail fat of the giant salamander comes from three different regions: Hunan, Hubei, and Shanxi, China, marked as HN, HB, and SX respectively. We weighed an appropriate amount of tail fat into a 100 mL colourimetric tube, added 2 mL of 100% ethanol, then added 4 mL of water, and finally added 10 mL of 8.3 mol/L hydrochloric acid solution and mixed well. This mixture was hydrolyzed in an 80 ℃ water bath for 40 minutes; upon completion of the hydrolysis reaction, it was cooled to room temperature. Then, we added 10 mL of anhydrous ethanol and mixed it well. Using 100 mL of a diethyl ether-petroleum ether mixture from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., we extracted in three portions and combined the extracts into a 100 mL round-bottom flask. We then evaporated the petroleum ether and diethyl ether layers to obtain giant salamander oil, labelling the samples as HN, HB, and SX according to their origins in Hunan, Hubei, and Shanxi, respectively.

We used method GB5009.168-2016 Chinese standard to determine fatty acid composition. The gas chromatography Trace1310 ISQ conditions are a TG-FAME column, with a temperature program of holding at 80°C for 1 min, heating at a rate of 20°C/min to 160°C, holding for 1.5 min, and then heating at a rate of 5°C/min. Then we raised the temperature to 230℃, held for 6 minutes, injector port temperature 260℃, carrier gas flow rate 0.63 mL/min, and split ratio 100:1. The mass spectrometry conditions are as follows: ion source temperature 280°C, transfer line temperature 240°C, solvent delay time 4 min, ion source EI source 70 eV.

4.4. Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS)

We thawed the tail fat of giant salamanders from three different regions at 4°C. A total of 20 mg tail fat from each region was mixed with 3 steel beads and 200 µL of pre-cooled 10 mmol/L ammonium formate/butanol/methanol (1/1, v/v) (Merck Millipore), followed by ultrasonic extraction in an ice bath for 60 minutes. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 20°C, the supernatant was collected for analysis. Equal amounts of three samples were mixed to form QC samples, which were used to assess instrument stability during LC-MS analysis.

Samples were analyzed using a SHIMADZU-LC30 ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system coupled with a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific™). The ACQUITY UPLC® HSS C18 column (2.1×100 mm, 1.9 µm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used for separation at a column temperature of 40°C, with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The mobile phases consisted of A: 0.77 g ammonium formate, acetonitrile:water = 6:4 (v/v); B: acetonitrile:isopropanol = 1:9 (v/v). The gradient elution program was as follows:

The gradient program begins at 30% B, 30% → 32% (0-2 min) → 45% (2-6 min) → 52% (6-8 min) → 58% (8-12 min) → 66% (12-15 min) → 70% (15-18 min) → 97% (18-21 min, held 21-25 min) → 32% (25-26 min, held 26-30 min).

The samples were stored in a 4°C autosampler throughout the analysis. To minimize potential instrumental fluctuations, the injection order was randomized, and QC samples were inserted every 5-7 experimental samples to ensure data reliability.

Mass spectrometric detection was performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative ion modes. The key parameters were set as follows: Heater temperature: 300°C; Sheath gas flow rate: 45 arb; Auxiliary gas flow rate: 15 arb; Sweep gas flow rate: 1 arb; Spray voltage: 3.0 kV (positive mode) / 3.5 kV (negative mode); Capillary temperature: 350°C; S-Lens RF level: 50%; Scan range: 200–1500 m/z.

4.5. Lipid Identification, Quality Control and Statistical Analysis

We applied the software MSDAIL (Version 4.0.9) for lipid identification and quantification processing. The main parameters are as follows: 10 ppm precursor mass tolerance, 10 ppm product mass tolerance; retention time of 0.1 min for ion peak alignment, chromatographic mass spectrometry peak area used to reduce false positive data extraction, and deletion of lipid molecules with ion peak area RSD > 30% in QC samples. The normalized total peak area of the data was obtained from the MSDAIL software, and after UV-scaling preprocessing, multivariate statistical analysis, including unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA), supervised partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). Univariate statistical analysis includes fold change analysis, volcano plot generation, heatmap and clustering, and KEGG analysis using R software [

54,

55].