The sculpture of the Buddha, the Stonehenge circle and the Moai alignment. The methodology will consist in a thorough and systematic analysis of the origin, implications and interplay of these three elements in order to improve the archeological complex and be able to assess the new realizations that have taken place at Takino, especially since 2017.

2.1. The Giant Buddha Statue

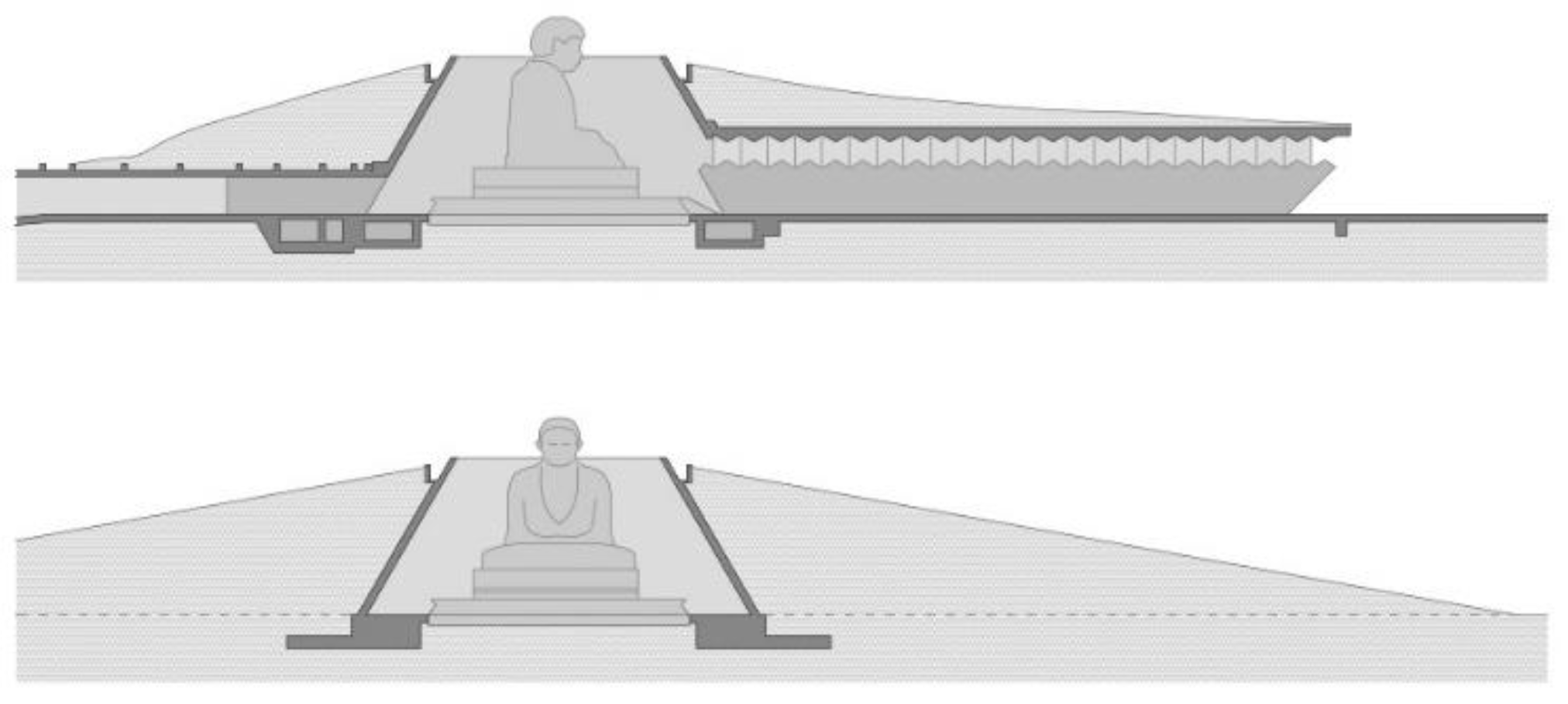

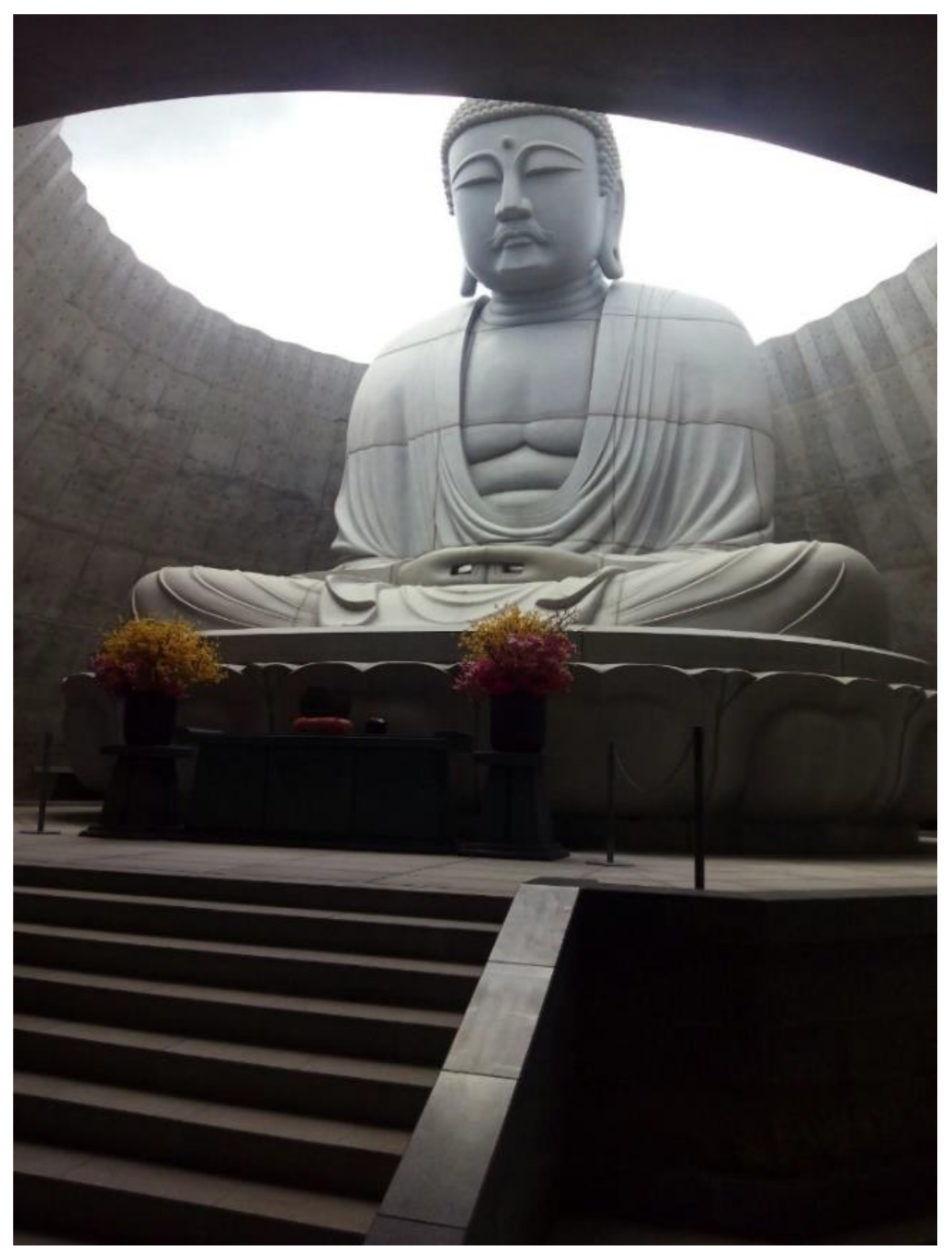

As explained previously, the Daibutsu is situated in the first place. This Buddha modelled after the Kamakura statue, is completely central to the precinct of the cemetery (

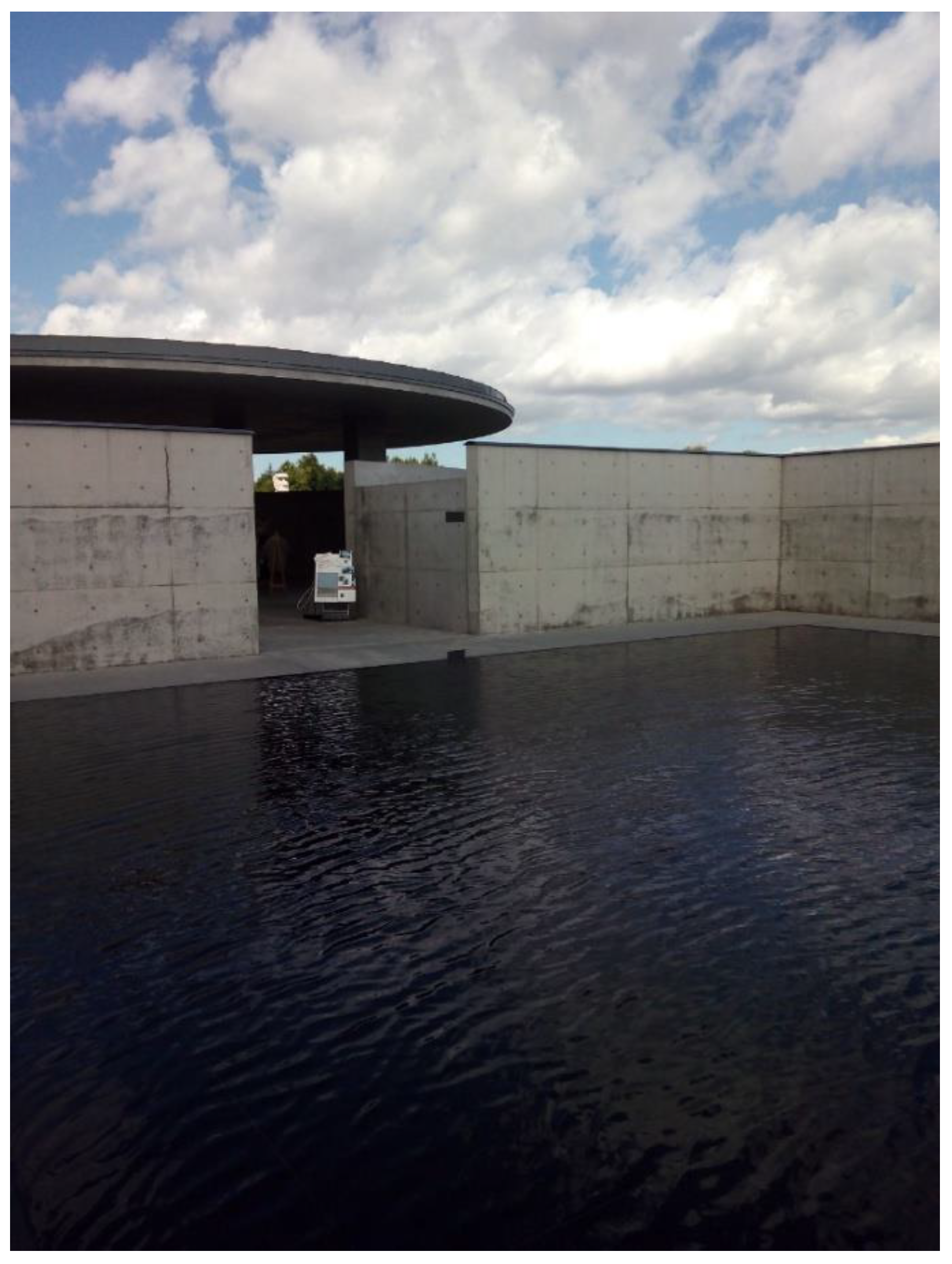

Figure 8), secluded by a hill and from 2017 onwards, it is preceded by a sizeable rectangular pond that impedes direct entrance trough the passageway and towards the massive sculpture weighting 1.500 tons and rising to a height of 13.5 meters [

29].

The imposing figure is flanked by two symmetrical mounds which, in this way, define an important avenue leading directly to the giant statue.

We must hereby stress that the sculpture is not directly perceptible from the entrance gates to the Funereal Park.

We need to outline that, in Japan, traditionally the Buddha image is not exposed to the outside, but rather accommodated in a grand temple of timber frame as in Todai-ji at Nara. The only exception is the Kamakara Daibutsu and this is likely due to the arson that once occurred in the hosting precinct; it was of such magnitude that the high priests of the time decided to leave the bronze statue alone without reconstructing the precedent temple [

30].

Besides, stone is not the preferred material for statures of the Buddha, instead we find mostly wood or gilded bronze in some special cases. This fact builds on the scarcity of permanent remnants in Japanese archaeology already stated. In the case of Takino, to settle these problems of conservation, it was planned that the sculpture would be composed of resistant granite stone and after careful polishing, left open to the visitors among the gentle slopes of the selected area of 800 hectares (See

Figure 8, above).

However, soon enough the towering image exerted an equal spiritual burden on the believers and by-passers. The stone Buddha was considered too solemn, imposing or even melancholic. The gloomy and cold weather of this area might have played a role for such ominous perception [

31].

In this respect, we can find an important transition case of an adumbrated but not really visible Buddha at the Byodoin (Temple of Peace) of the town called Uji. The whole precinct is an example of Amitabha Buddhism in which the pilgrimage destination to be reached was the paradise of the West. The travelers were forced to accede to the complex by the river Uji and not by the current entrance from the narrow streets inside the town. It is remarkable that the name Uji in Japanese 宇治means the Kingdom of Heaven or the Heavenly Paradise [

32].

The central hall is called Hôôden 鳳凰殿, the Palace of the Emperor Phoenix. It is in fact crowned by two symmetric phoenixes which, when nested over a temple, auspicated the flow of spiritual and material perfection for the entire realm. Their mere presence suggested a breeze of harmonious sounds echoed by the peculiar wind instrument called Shô. The Hôôden was considered an emblem of Japan to the point of being reproduced life-size as Japanese Pavilion for the Chicago World-Fair of 1893 (

Figure 9). The person in charge of that pavilion was the celebrated artist and writer Okakura Kakuzo, the author of The Book of Tea, written solely in English in 1906 [

30].

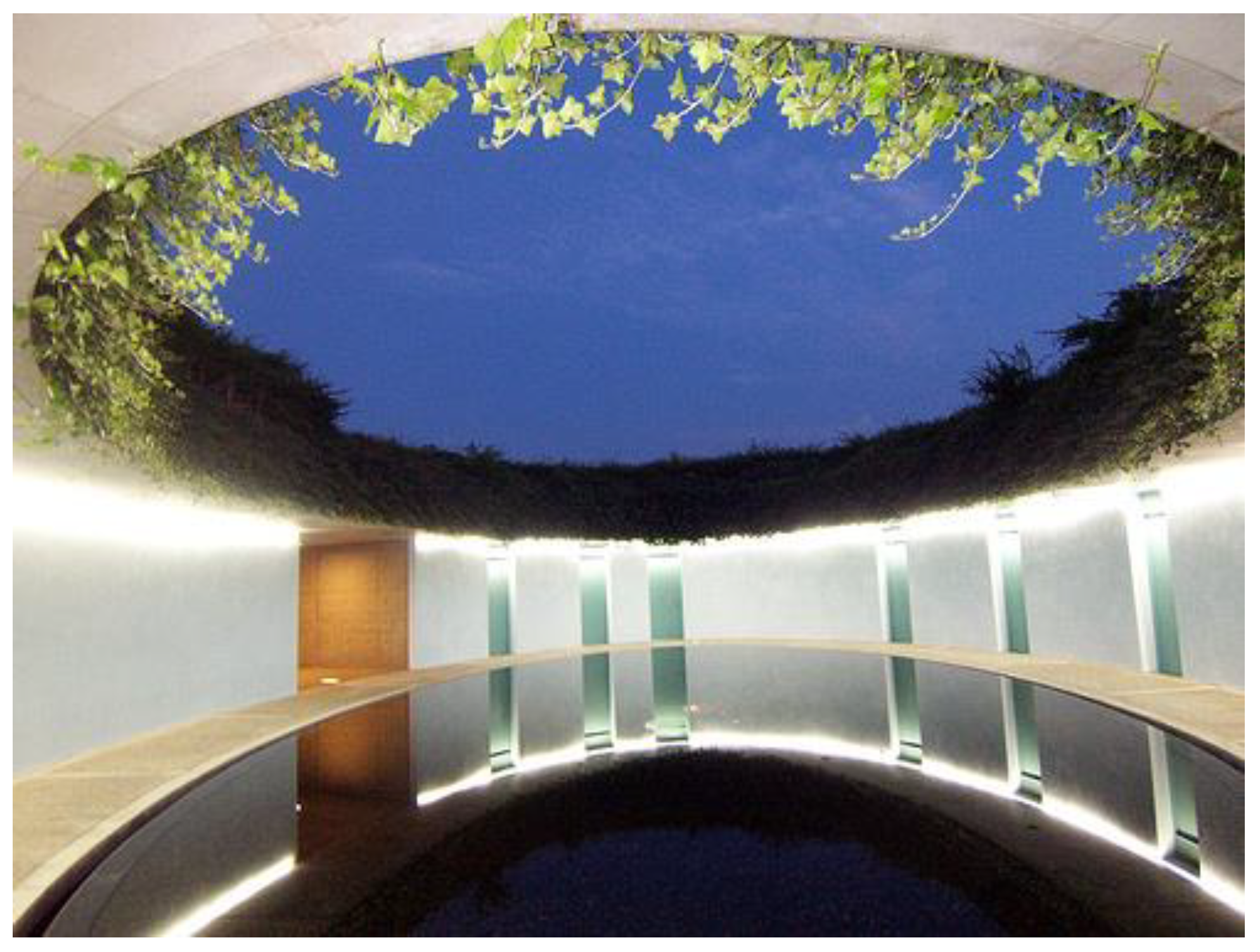

The relevant feature of this temple for the case of Takino is that the lattice work and oval opening of the main gates allowed to contemplate from the outside the countenance of the Buddha without need to penetrate inside the temple (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). These elaborate process of visualization of a deity or religious image is called darshan in sanskrit दर्शन.

The Byôdôin scenography and iconography are so meaningful that they have been reconstructed in places far away from Japan as in Oahu, Hawaii (US). In this careful reproduction the access and view from a body of water are duly respected; it was dedicated in 1968 in memory of the Japanese Immigration (

Figure 12). Besides the Buddha, historic characters like George Washington are revered in the surroundings under the category of kami.

For esoteric theology matters, the hidden Buddha or Hibutsu 秘仏 is an invariant of East Asian religions. Since the historical Buddha Shakyamuni ascended to Heavens after entering paranirvana 涅槃 (nehan in Japanese), it cannot be manifest or appear frequently in the earthen world. Those who could possibly be summoned are the bosatsu, impersonations of the Buddha who voluntarily elected to remain in this world in order to help human beings attain nirvana in their turn [

31]. For that reason, it is rare in Japan to find a statue of the Buddha exposed to the outdoors and some of the images in the temples can be regarded only on special occasions, every fifty or even one hundred years. Even the shadow of the Buddha is considered a good omen and this belief has been incorporated into a common expression of everyday Japanese language [

33].

A somewhat extreme case of the former attitude is to be found at the previously referred temple of Borobudur in the outskirts of Yogyakarta Indonesia [

19], in the third level of the pyramid we would find a retinue of curious bell-shaped stupas, providing some spiritual ring to believers (

Figure 13). The stupas are hollow and just through rhomboid apertures we can surmise a finely carved Buddha statue kept within. It is somewhat astounding that the original builders had to take such effort to create the sculptures (

Figure 14) only to subtract them later from open view as they are perpetually put to rest behind heavy stone blocks.

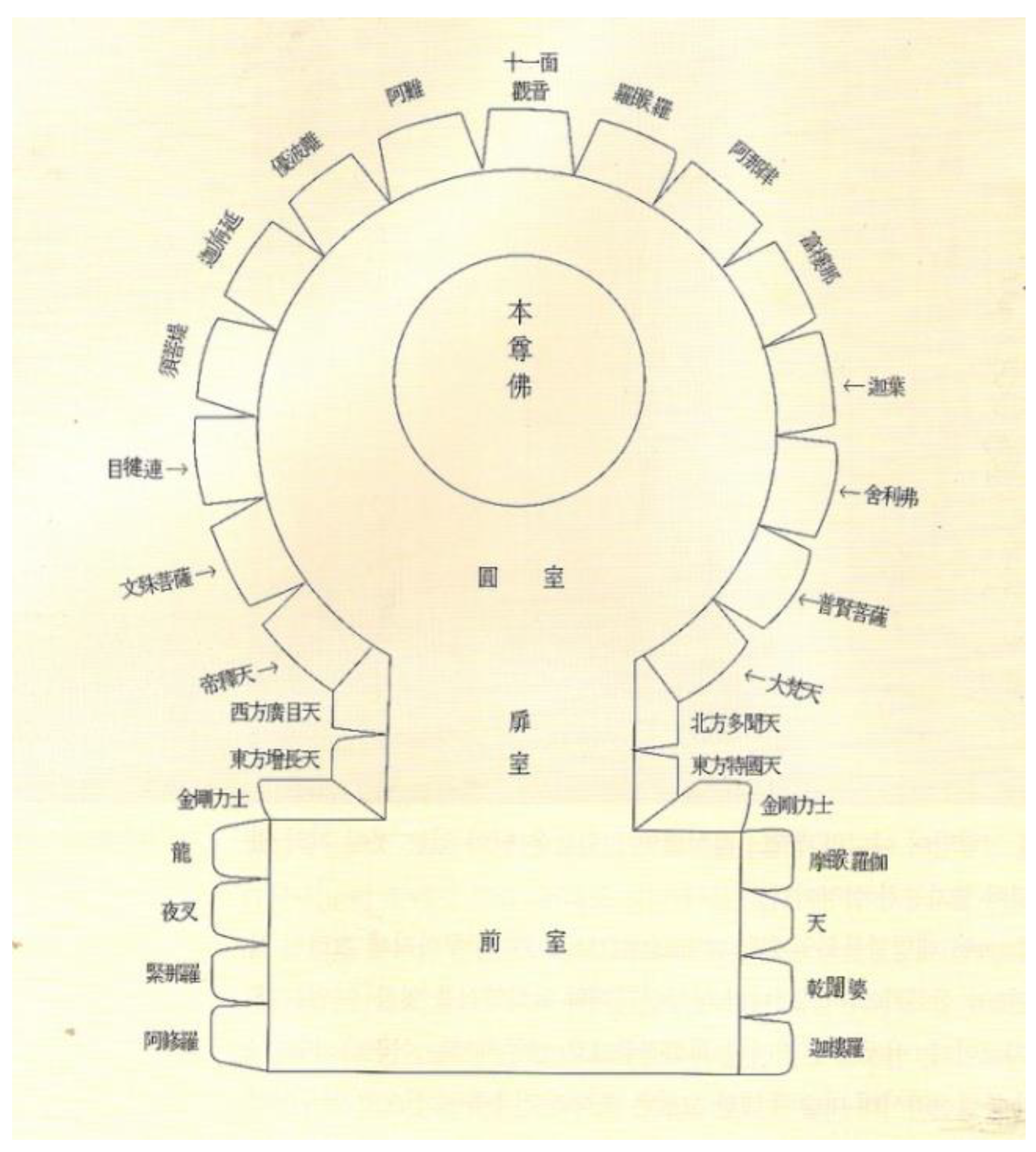

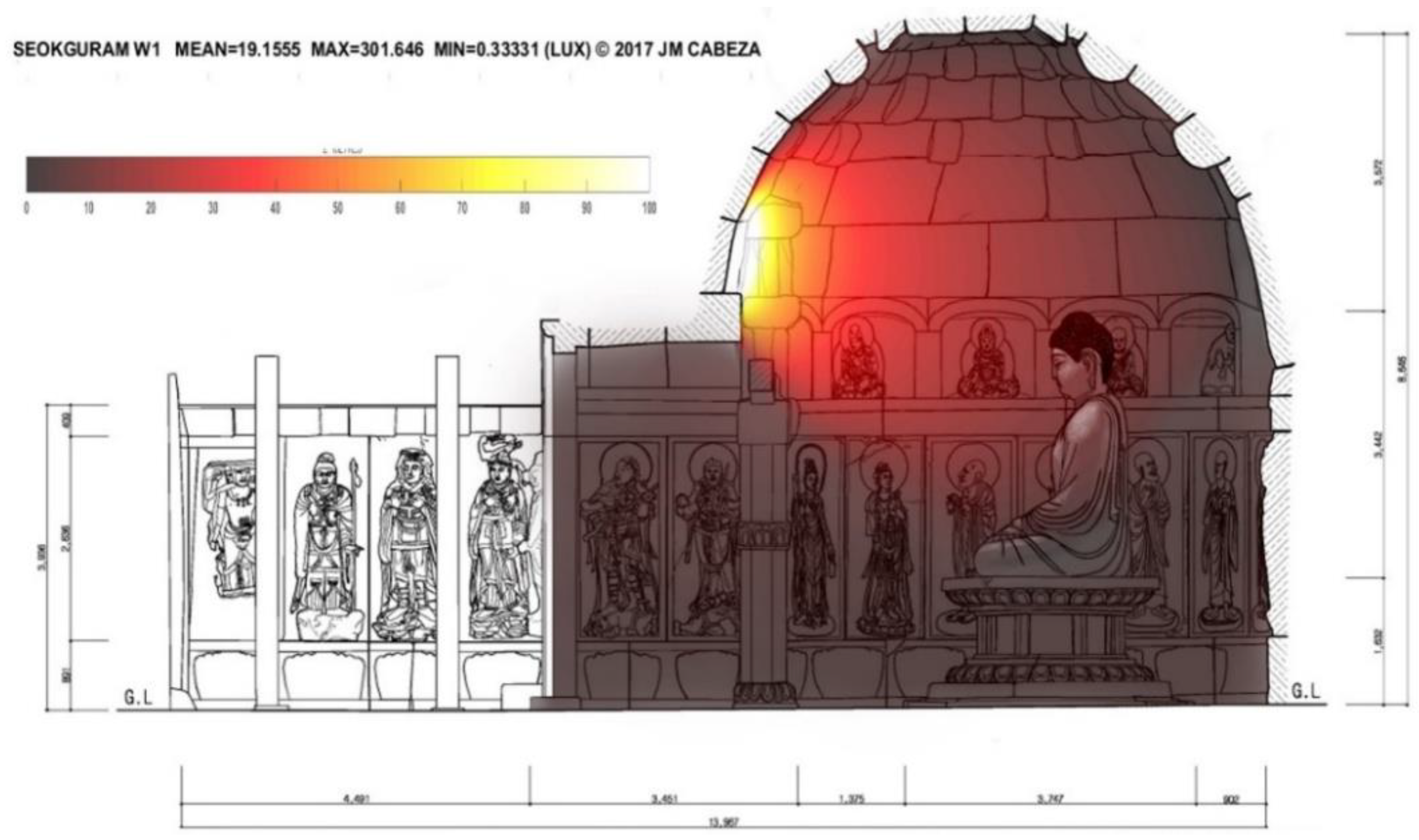

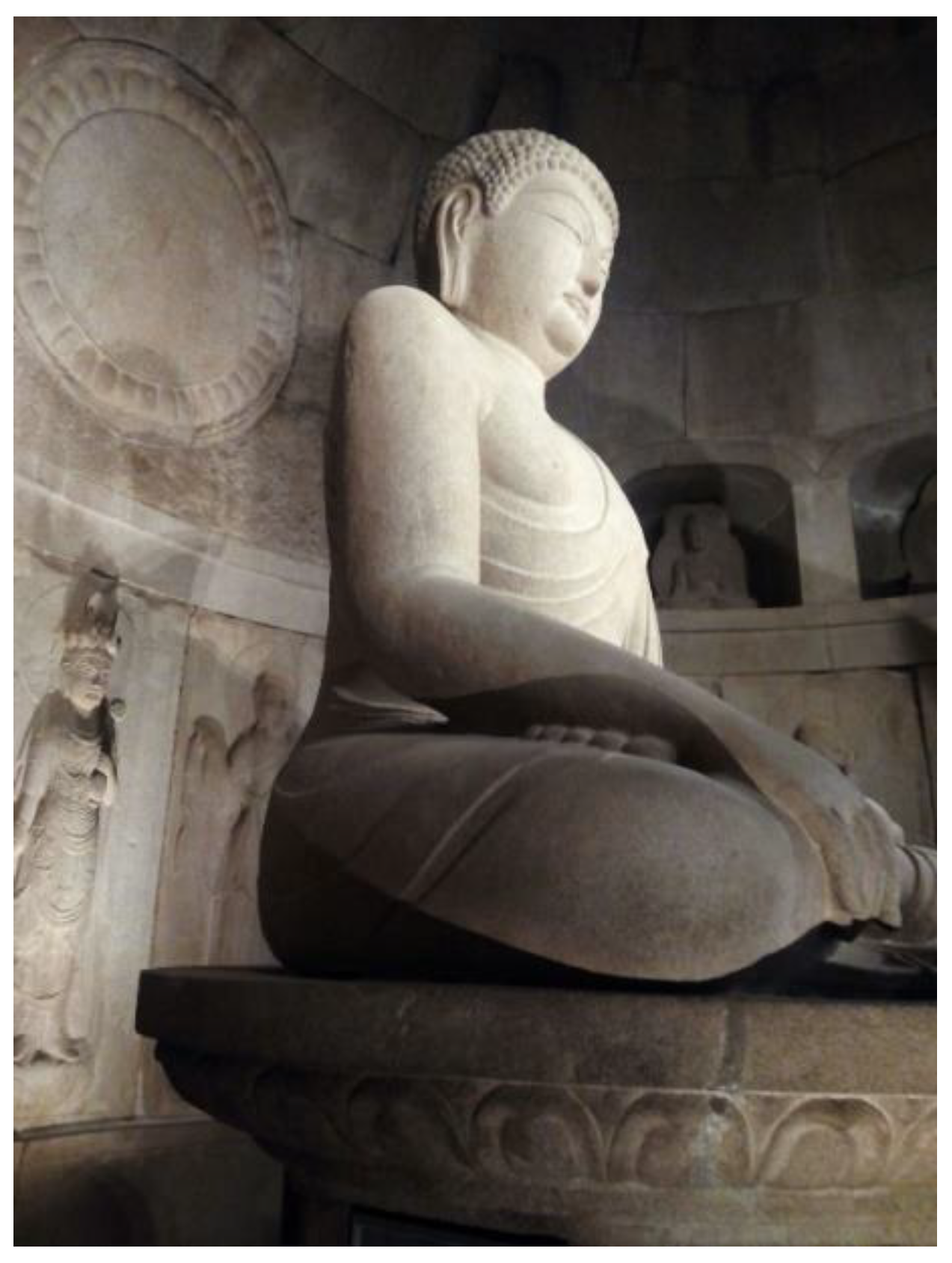

A less remote example of a covered Buddha is located at Gyeongju in Korea. The hill of Seokguram where it was erected, has been a consistent source of attraction for the local people and foreign travelers as well. The seemingly nondescript artificial cave indicated a novel concept of space [

34] for Asia that was subsequently forsaken for centuries, until incidentally rediscovered by the Japanese because it was mainly built in stone and since then is experiencing a revival to the point of having been declared as a Human Heritage site (

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17).

Its main features are as described in the manuscript of Ko Yusoep [

33]

This great statue, beginning as a bloodless, passionless lump of granite, has been endowed with a strong pulse, breath, divinity, gentleness and dignity. When unveiled, the joy was surely not limited to the sculptor, but extended throughout Silla and echoed towards the cosmos

And in the book of Joon- Sik Choi [

34] we can read these impressions:

You cannot help but wonder how on earth it was possible to carve such a soft and flowing appearance out of granite, a rock that is so hard that it is considered the most difficult stone to sculpt… Isn’t it enough for the best works of art simply to exist?

The Seokguram enclave links with a cherished Buddhist tradition of hypogeal compounds [

35,

36] that goes back in time to thousands of years and originated mainly in India [

17] in coenobiums known as chaitya. The climate of the Indian plateau and the geologic characteristics of its soil favored the introduction of this peculiar system of construction [

8] intended for religious or spiritual communities.

The tumuli that formed the stupa [

15] began by nominal diggings on the surface of the rock cliffs to serve as mere storage and shelter, until gradually becoming sumptuous hypogeal temples devoted to the Buddha and its grand ceremonies. The main reasons for such a procedure were both climatic and spiritual: the imperious necessity of building a covered space to conduct religious ceremonies or to offer prayers when the storms of monsoon weather prevented holy mission or any kind of outdoor activities for monks and disciples alike [

5]. Such spaces also reduced the probabilities of incidental stamping or crashing onto swarms of insects that thrived in the damp of the stormy season. However, in Korea, the Seokguram cave, a celebrated Buddhist space, emerged from the antecedent of ritual tumuli [

7].

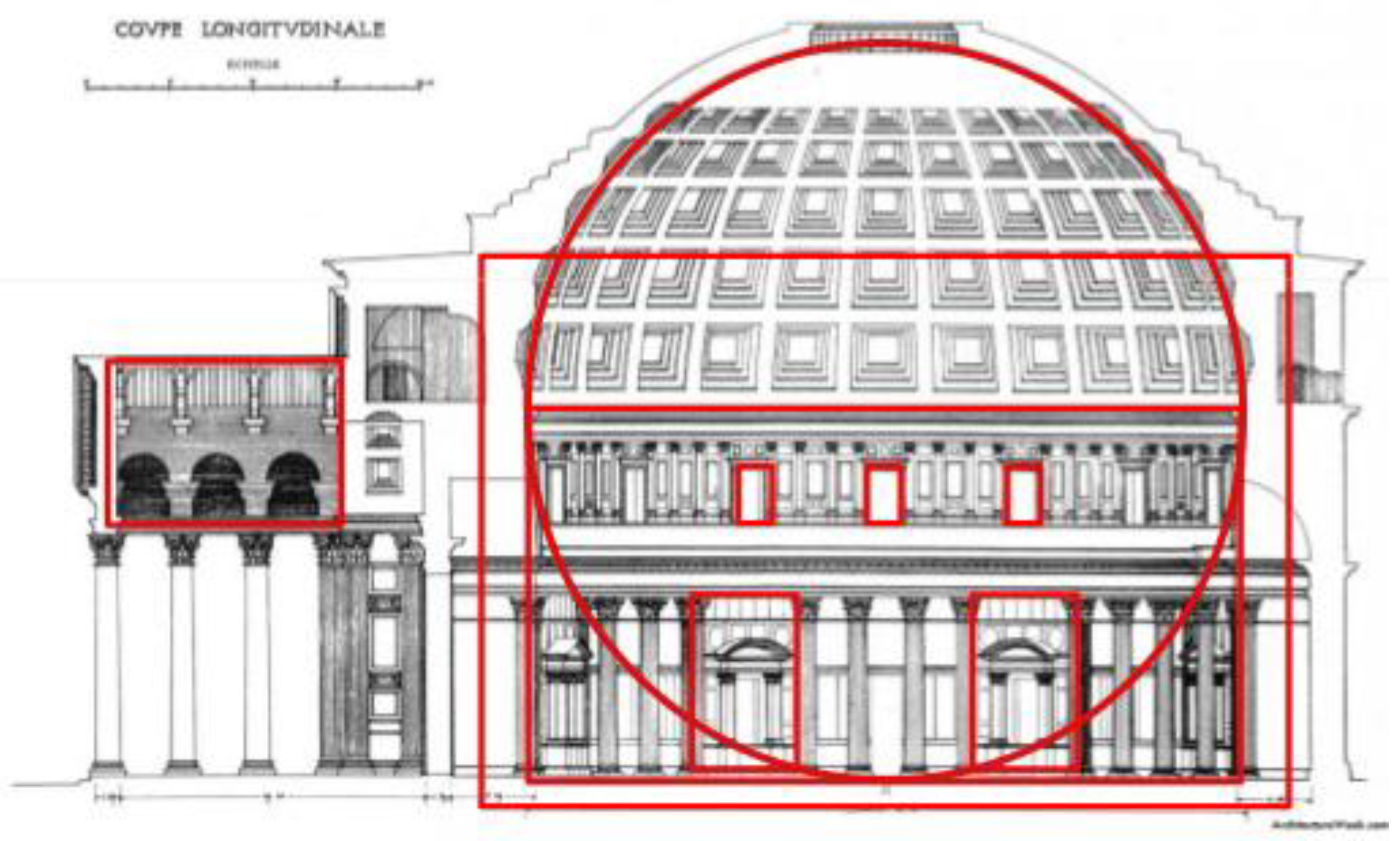

Being a form of revolution, the tumulus or the stupa beckon a cosmic order that is revealed through its external features, aspects that were taken as a prototype in Japan, Korea and China [

15,

16].

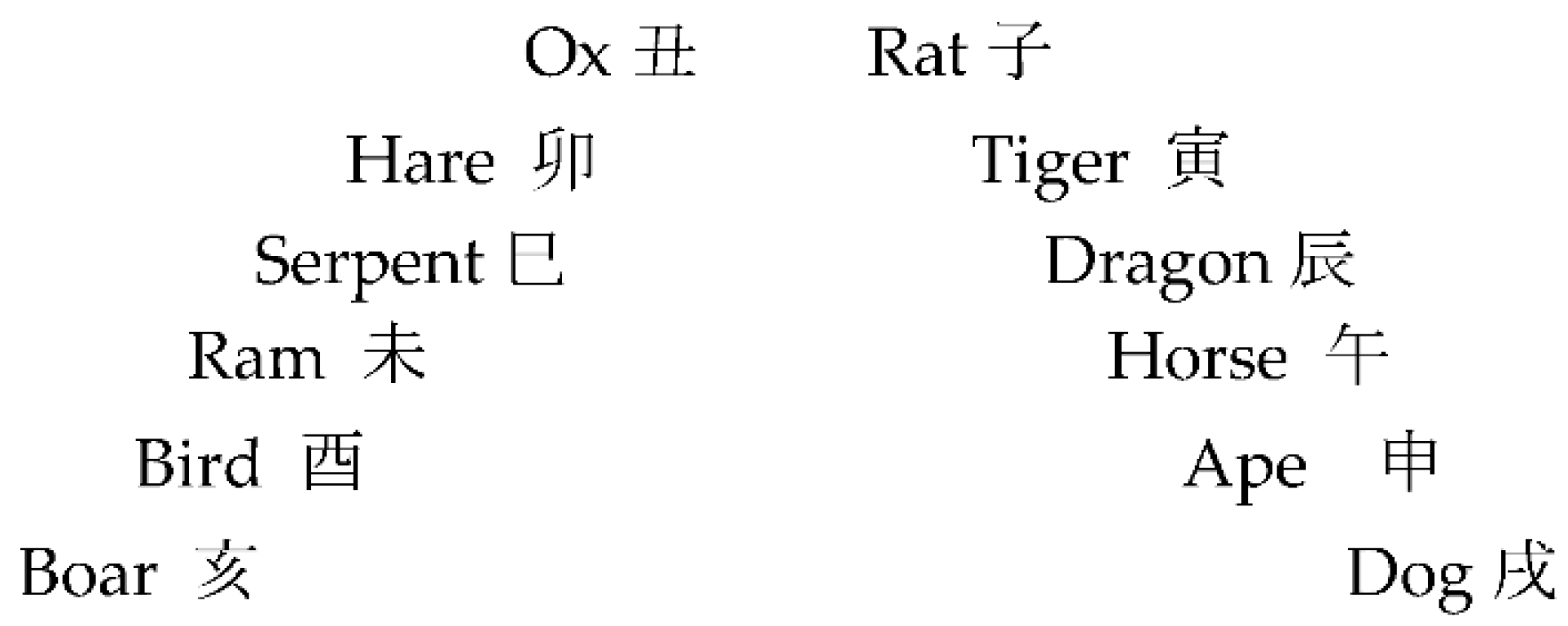

Domes consisting of masses of stones have been used in Korea since ancient times to create a sort of ceremonial mound. Often they are covered with vegetation, mosses and grass. The first tumuli had no inner space, but they implied a geomantic meaning as a sort of altars that required to be encircled for rituals [

9]. At a later stage, such Feng Shui of the land was made explicit by the designated sequence of images of the twelve astral beings which compose the Eastern Zodiac. These entities regulated the seasons and the time within the day. (

Figure 18 and

Figure 19).

The said astral creatures, provided with common animal heads on a human-like torso, appeared on the base of the tumuli at regular intervals from the solar directions [

9], starting with the horse 午 (

Wu in Chinese), which roughly translates as Meridian or Noon. This astral horse is aligned with due South as it signals midday (

Figure 19). The normal sequence of the beings, clarified by the authors is: Rodent (24 h), Ox (2 h), Tiger (4 h), Hare (6 h), Dragon (8 h) Serpent (10 h), Horse (12 h), Ram (14 h), Ape (16 h), Bird (18 h), Dog (20 h) and Boar (22 h). It is interesting to remark that unlike Japan or China, in Korea the entrance to the tumuli has a deviation of five to ten degree from the solar south-north axis.

In Japan the twelve beings are frequently presided by four major entities, that is: the dusk war of turtle and serpent, to the north, the turquoise dragon to the east, the vermillion phoenix to the south and the white tiger facing west. Mostly the four Guardian Kings as they are called, appear on the inside of the tumulus or statue concerned and sometimes they are formed outside of the building as in the famous temple of Shitenno-ji in Osaka [

37].

So far, we have roughly described the design intentions for the section of the Buddha statue at Takino. Surprisingly, this sculpture was completed with the alignments of Stonehenge and similarly at the main side of the complex by a lengthy retinue of 42 Moai statues similar to those erected on Easter Island. Let us present both archaeological milestones in the following lines.

2.2. The Stonehenge Ring

Although much older in historical apparition, henges are similar to the tumuli described beforehand in the sense that they are both megalithic rings that suggest rituals of circumambulation usually following the solar cycles.

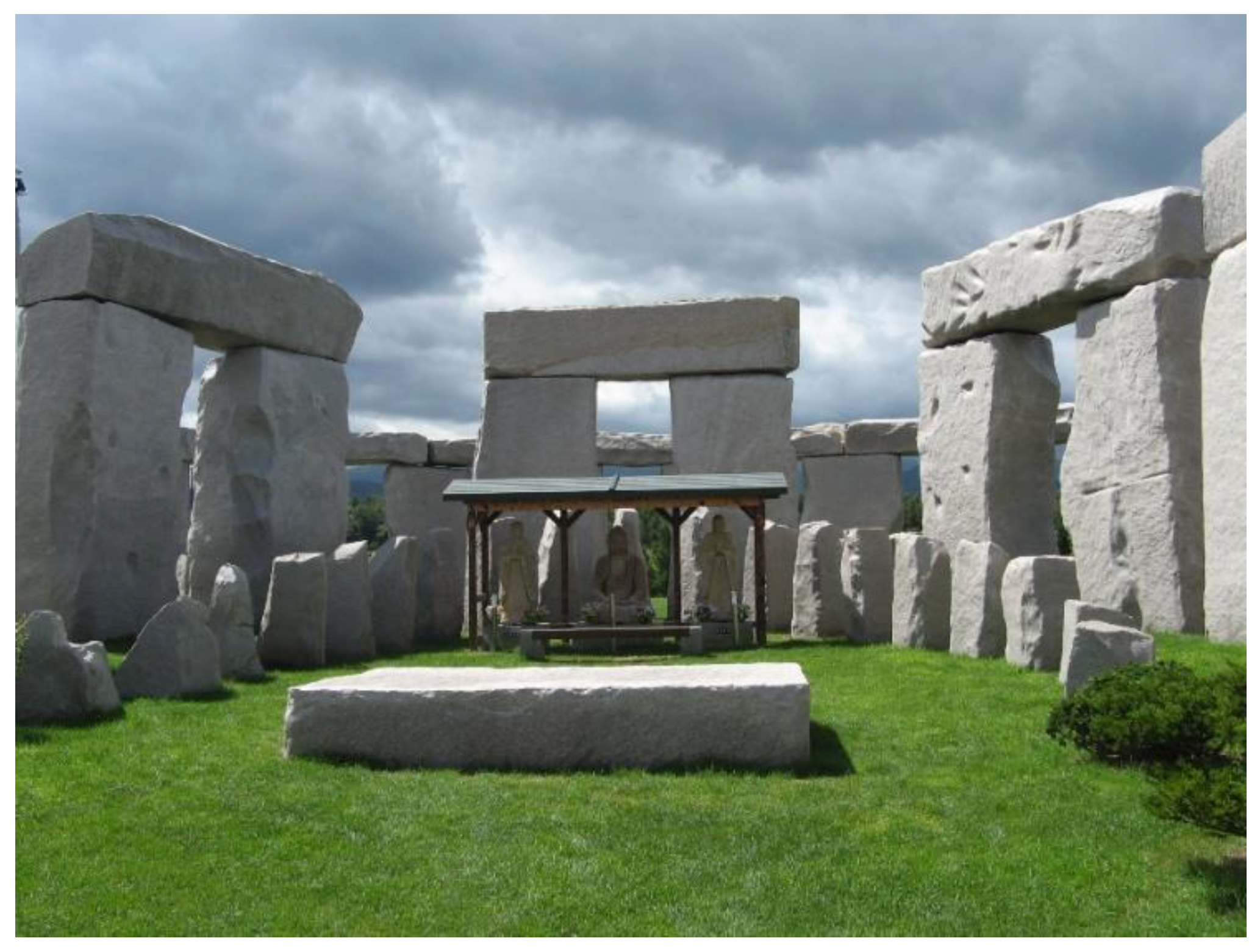

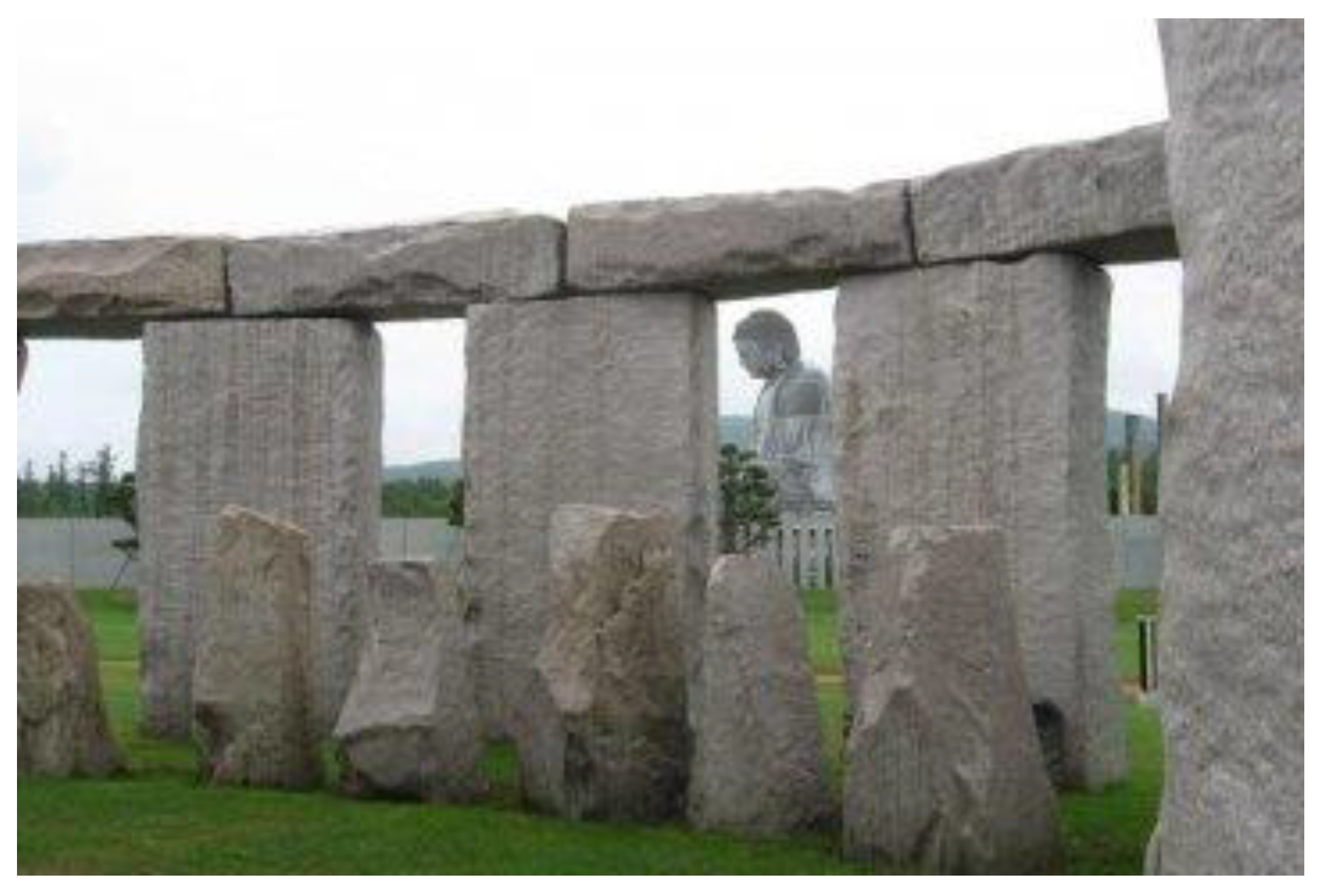

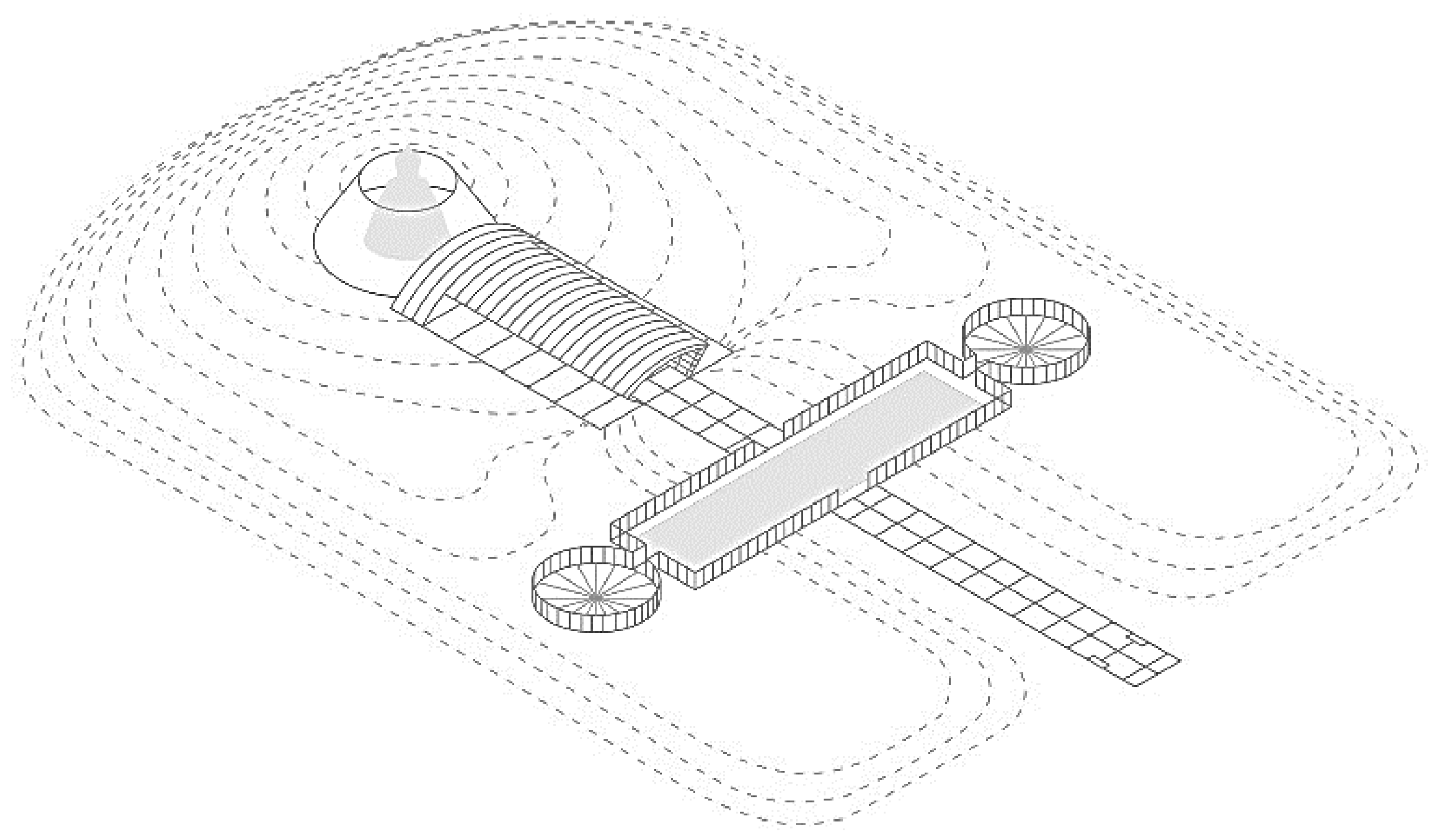

It might seem contradictory to display a reproduction of an ancient British stone circle in the design of the park, in coexistence with the Great Buddha, the reasons for that are variegated (

Figure 20).

Customarily, in Japan a Buddhist temple is completed or connected by syncretism with a Shinto sanctuary. This also happens in China and Korea with the singularity that instead of Shinto we might have a Daoist precinct or a Muist element. Some argue that the Shinto religion is a unique Nipponese evolution of Daoism [

38].

Nevertheless, at a funeral necropolis it is inauspicious to bring in or invoke the kami or spirits of the Shinto, which eventually represent the everlasting life-forces of Nature and favor transmigration or transformation in perennial conflict with death conceived as cessation.

Shintoism is the traditional religion of Japan and the only one endorsed by the Imperial Household after the Meiji Restoration. One of its main postulates is remote antiquity (real or feigned) and in an island recently inhabited by the Japanese as Hokkaido it has often been controversial to enforce the “Way of the Gods” [

35].

The most representative element of Shinto shrines is the Torii 鳥居. Such element can be defined as an elaborate wooden lintel painted in vermillion (

Figure 21). The Torii exerts the complex function of beckoning and attracting the Sun, which is the paramount deity of the Shinto’s numerous pantheon (Amaterasu 天) and therefore an adequate symbol of Japan. This is reinforced by the ever-present sacred rope called shimenawa しめ縄, with its zigzag paper fleece, representing sunrays, which decorates and blesses [

39] the Torii or its annexed structures as the case may be [

40]. Even the character of the word is formed with “bird” in the sense of the vermillion phoenix. The underlying metaphor is that the sun would perch on the Torii much in the fashion the birds do.

The insular nature of Japan as opposed to the great continent of China, has suffered on occasion the comparison with the British Isles. After all, both island nations retain the system of a religious ruler unlike France and China in which the celestial-line of predestined monarchs was abruptly ended after violent revolutions [

41].

The designers of the Takino park, dared to imagine that lintels of recycled stone from the sculpture of the Buddha could be converted into a Stonehenge-like profile, as it would serve their purposes of attracting the public less prone to the Buddhist faith and evocate at the same time primitive beliefs of cosmic and archaeological resonance in an intriguing location (

Figure 22) [

42].

By invoking an improbable proto-historic past, perhaps inadvertently, the promoters of Takino, created a unique opportunity of beholding an extraordinary landmark as pristine as in the same day of its erection, with no foreseeable problems of preservation unlike its Britannic counterpart. To the minds of the authors, the debate on authenticity and originality is somehow skipped since the original monument had no inscriptions, art or reliefs of any sort. As we know, granite is an igneous rock as abundant in Japan as it is in England [

19,

43].

In this manner, intellectual curiosity for ancient monuments is completely satisfied in an idyllic surrounding and is hardly perturbed by the discrete interments of funeral ashes enshrined under the henge.

The orientation of the stone-blocks was somewhat altered (

Figure 23 and

Figure 24), as in the replica, shattered fragments of the lintels were not left to scatter on the ground. This has shifted the possible original solar or cosmic alignments although this extreme has not been fully demonstrated.

It is interesting to notice that Stonehenge’s replica does not face the central axis formed by the Buddha statue but ends in a parallel path to that axis (See

Figure 7)

At a given moment, the stone circle incorporated a sheltered altar (

Figure 25) with three Buddha figures. This element was later removed. Under the circle there is a glazed locked chamber accessible through stairs and which contains the ashes of the departed in metal niches. Also the sculpture of the Buddha was in direct visual connection with the stone circle. In the new configuration after 2017 this is no longer possible (

Figure 8 and

Figure 26), with which the importance of the Stonehenge circle is strengthened in the whole picture.

2.3. The Moai Alignment

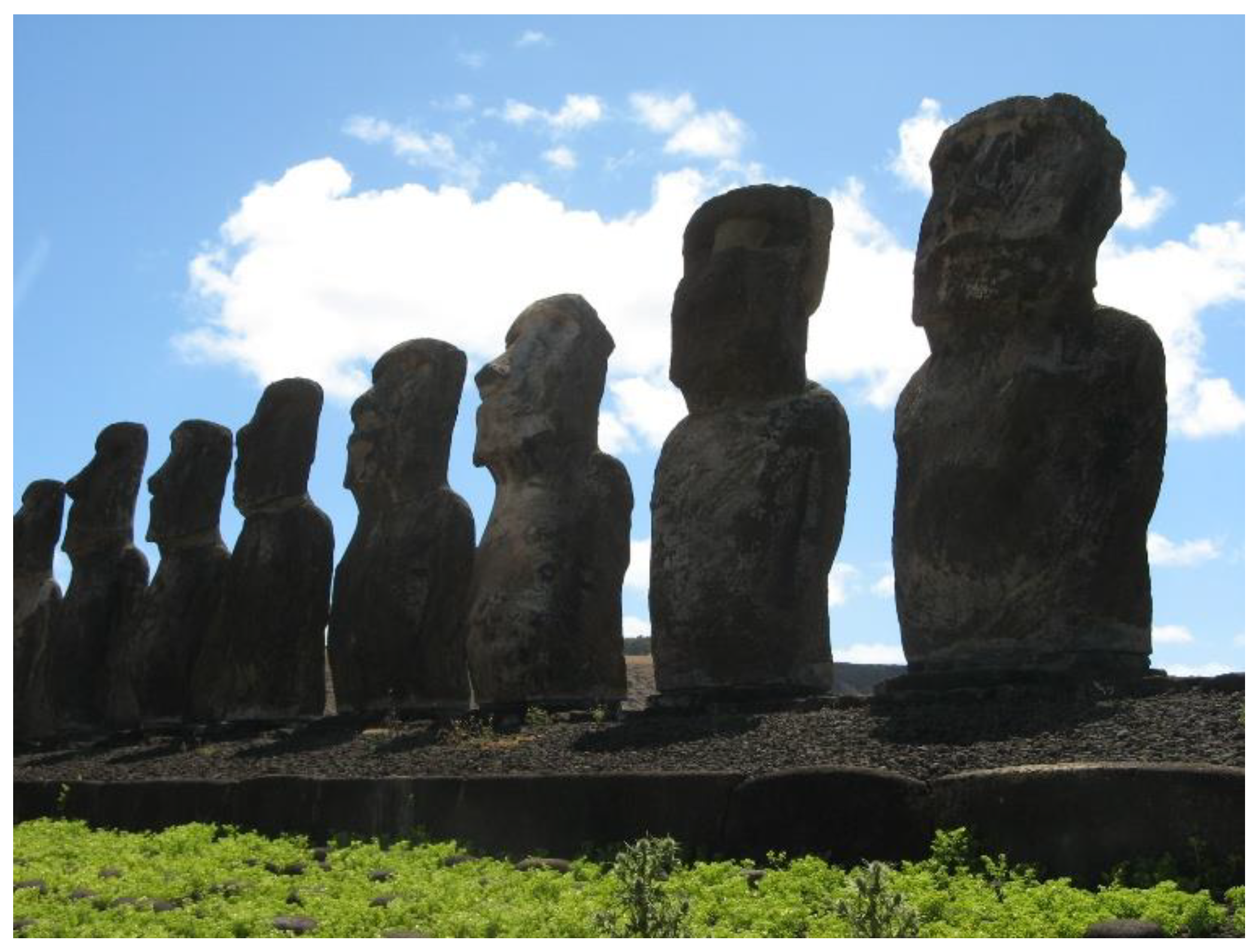

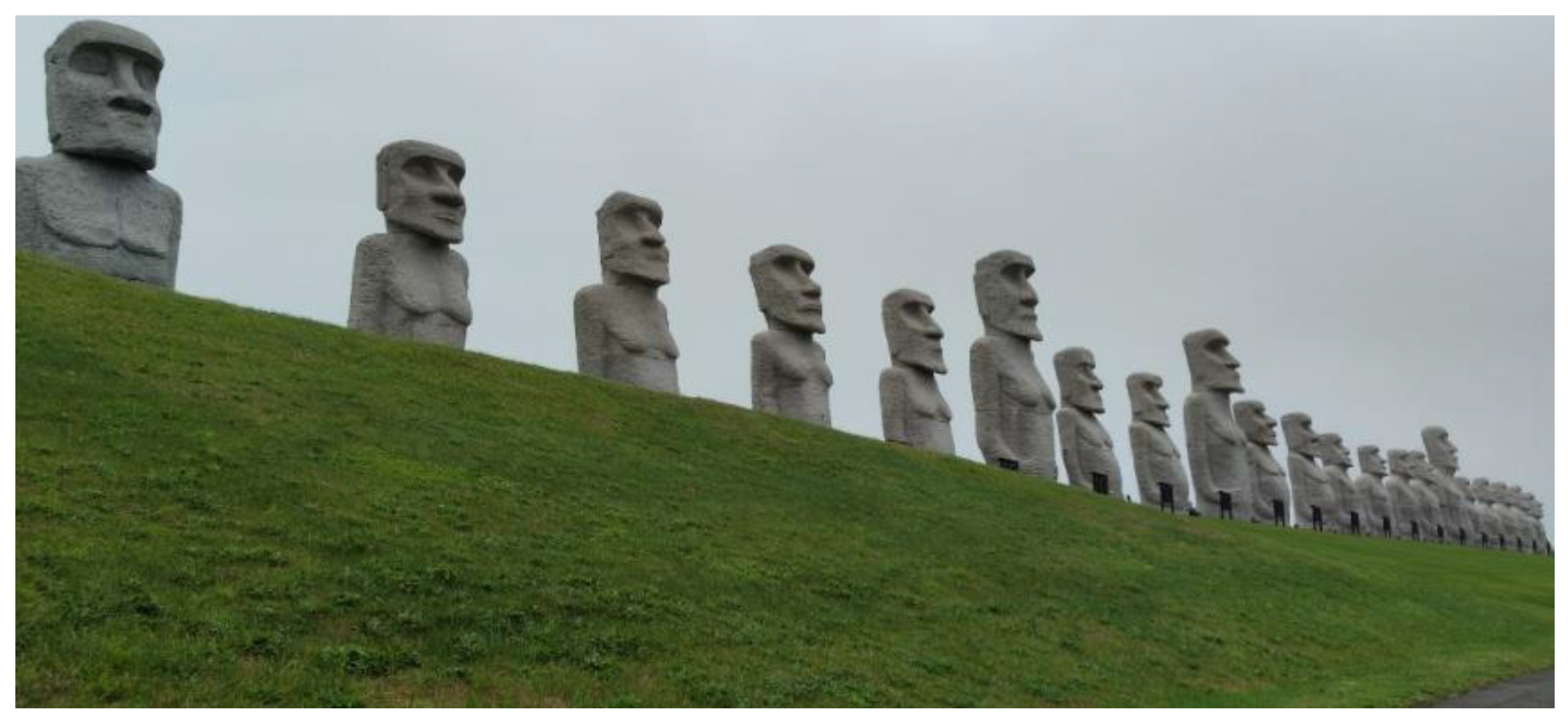

The third important nexus of the Takino complex is the row of 42 Moai. Moai are probably one of the most notorious remnants of the Rapa Nui People as well as the most recognizable icon of Easter Island. The standard Moai can be briefly defined as a colossal humanoid figure carved from the ashes of the Rano Raraku crater or any other volcanic material, with an oversized and elongated head composed of simplified and geometric lines [

44].

Their bodies are minimalist, with arms resting at the sides or on the stomach. The legs are frequently imperceptible, although they suggest a crouched position (

Figure 27). The torso rests on a ceremonial platform called ahu which cannot be trodden under any circumstances, it replaces the lower limbs of the bodies. This sacred platform has not been respected at Takino cemetery, which could then be considered a sort of mockery of the original figures (

Figure 28). The Moai could be detailed at times by a red crown or hat called Pukao and two rounded eyes made of coral or white conch.

Although the true meaning of the Moai is still under discussion, we are certain that they were a central piece of Rapa Nui society and are usually linked to the religious life of the islanders, often being understood as a representation of their deities or ancestors [

45].

The Rapa Nui disappeared into the ashes of time, but their enigmatic giants can be compared to a variety of religious practices that exhibit similarities in numerous locations of Polynesia, the Lapita area of influence and East Asia. We can name in this group the Tiki idols, the Filipino Anitos and the Korean Dol Hareubang from Jeju Island, a territory where shamanism is still practiced today.

Korean shamanism, also known as Musok or Mukyo, has demonstrated unparalleled adaptability and has managed to integrate into contemporary society, crossing boundaries even beyond the Han Republic. The Dol Hareubang (“stone grandfather” in Jeju dialect) became an emblematic figure of the Korean pop culture but is also a valuable part of the Jejuan own identity, a friendly and merry character who can be found on souvenirs shops or bagatelles, but who is also related to ancient beliefs that are still alive [

46].

The Dol Hareubang bear substantial similarities to the Moai, although these are smaller (about the size of an adult or child, but this can vary) and maintain slightly more realistic proportions. The grandfathers are sculpted into the porous basaltic rock of Jeju Island, and their contour and facial features are substantially rounder and caricatured than those of the Moai, with large eyes and a flat, bulbous nose. The headpiece is now integrated into their heads, whose headdress has become a bowler hat, giving them a silhouette oftentimes described as phallic, thus associating the stone idols of Jeju with fertility (

Figure 29).

The arms typically rest on the tummy. Some Koreans identify this gesture with abundance or pregnancy, and it is said that touching the nose of a Dol Hareubang helps women have offspring, being Jeju Island one of the biggest tourist attractions for newlyweds on the peninsula. They feature integrated feet or bases, which were especially useful as they used to rest at thresholds or crossroads as guardian deities, in an analogous manner to which Haechi, protector and mascot of Seoul, did in mainland Korea [

47].

The stone grandparents of Jeju Island are deeply connected with the local shamanism and are also referred as Beoksu Meori, “totem head”. According to the Jeju tradition, the Dol Hareubangs serve as receptacles for the spirits, “grandfather” becoming synonymous with “ancestor.”

Other analogous characteristics can be observed in antique megalithic sculptures of pre-Columbian America, such as the Olmec art or more clearly the Colombian stone idols of San Agustin, the “Andean Easter Island” [

45]. These discoveries seemed to reinforce earlier theories of pre-Columbian transoceanic contact, such as those formulated by anthropologist Paul Rivet or Thor Heyerdahl which were later discarded by evidence based on genetic tests [

44]. Another archaeological site outisde the Pacific where huge stone heads have been identified is the hierothesion of Antiochus I at Nemrut Dağı (Turkey), originally the statues belonged to seated gods but the heads were removed at some point [

48], and now they bear a curious resemblance with Atama Daibutsu of Takino as only the head of the Buddha is visible over the hill. Although other authors may consider these coincidences as superficial or extravagant, the ancestral spirituality of the Pacific seems to permeate and symbolically connect, through archaeological vestiges, places like Jeju, Easter Island and Takino Cemetery, at least for the imagery of the people.

Coming back to the general plan of Takino, the Buddha was situated between two symmetrical mounds which define an important axis leading directly to the giant statue. The Stonehenge compound is at the end of another axis running parallel to the Buddha’s axis. The line of the Moai is segmented and does not follow any of the principal directions related to the Buddha or Stonehenge’s circle. They seem to pass as wraiths encompassing the said landmarks.

Apart from the three main elements analyzed, other milestones were considered for the design of Takino cemetery, among them the archaeological ruins of Tiwanaku (Bolivia) and Machu Picchu (Peru), Angkor Thom (Cambodia) and different kinds of pyramids. However, they were deemed unrecognizable or not sufficiently related with funereal culture and were consequently discarded.