1. Introduction

Floods are said to occur when flows occur on an otherwise dry land or when the flow in a water body is well above normal values. There are many types of flood defined as per when and where they occur. Fluvial floods are known to occur when water levels in the channel flow over the banks and spill into the floodplain. Pluvial floods are caused by water directly accumulating on land surface that are not necessarily near a river. Coastal floods are caused when seawater is pushed onto land by high tides, storm surges and tsunamis. Urban floods are a type of pluvial flooding where flooding occurs in urban areas mainly due to excessive amount of impervious surfaces and insufficient drainage systems. Flash floods occur when a large amount of rain falls over a short-period of time. The high intensity of rainfall reduces the amount of infiltration and quickly leads to runoff. While not very common, the rise of groundwater levels in low-lying areas can also lead to flooding and is referred to as groundwater floods [

1].

Flooding is a common natural disaster that affects every part of the Earth and causes billions of dollars of damage and even loss of life in many parts of the world. The US Department of Homeland Security states that 90% of the natural disasters in the US involve flooding [

2]. Climate change models indicate that floods will become more intense and also increase in frequency in many parts of the world [

3,

4]. Increased urbanization to accommodate growing global population and heterogeneous economic growth is also diminishing natural infiltration capacity and increasing runoff and flooding in many areas [

5]. In addition, improper construction of flood mitigation structures, dam breaks and other engineering failures can also lead to flooding [

6]. Given the large-scale economic, environmental damages and health and loss of life hazards to humans, the deleterious impacts of floods must be prevented when possible or at least minimized to reduce damages.

It is important to ensure that flooding impacts on humans are either fully eliminated or controlled to the extent possible. Developing such strategies to combat flooding is not easy as the main drivers of flooding - 1) Weather and climate and 2) land use alterations cannot be predicted with a high degree of certainty and are prone to change. The impacts of floods must be managed so that the community can rebound back to normalcy as soon as possible. As societies continue to learn from flooding diasters - How have flood management paradigms changed over time? and what are the current approaches with regards to managing flooding risks?

Flood management requires decision-makers to have reliable data on various aspects. These data include, flooding characteristics such as peak flows, flood duration, flood volume, flood inundation depths. Factors causing flooding such as precipitation and land use alterations must be known as well. In addition, information on population distribution, social chracteristics, economic assets that are directly in the line of flooding hazards must also be mapped. Such data are not only useful for immediate flooding emergency response operations, but also to guide the development of new flooding infrastructure to absorb the shocks of flooding or at least mitigate their impacts to acceptable tolerances. In case of riverine flooding, the impacts on aquatic and riparian habitats and ecosystems are also of concern. Much of these data are hard to obtain and are not deterministic in nature. Therefore, decisions regarding flooding have to be made under considerable uncertainty.

Mathematical models have been used to support flood decision making. Models can be used to translate rainfall into runoff (for a given set of land use) and estimate the dimensions of flood such as peak flows in rivers, the area likely to be inundated, the depth of water on urban transportation infrastructure. These models are used not only for quantifying flooding related hazards, but also used to design flood control and flood mitigation structures, assess risks to humans and the environment due to flooding and develop new policies and guidelines that help in proactively combating the effects of flooding.

A wide range of tools and techniques have been proposed using a variety of different mathematical strategies. Mathematical models built using conservation principles of physics and at varying levels of spatial and temporal complexity have been available for some time now and continue to be widely used [

7]. In a similar manner, a broad range of statistical tools have been used for flood estimation and forecasting [

8,

9], multivariate flood risk assessment frameworks [

10,

11]. In recent times, the use of machine learning (ML) methods is gaining ground [

12]. ML methods are universal approximators that can capture highly nonlinear relationships. As such, their utility for flood forecasting has garnered much interest in recent times. The literature identified using a simple search “Flood and Machine Learning” has more than doubled from 19000 documents retrieved in 2015 to over 40,000 documents in 2024 by Google Scholar [

13]. This change is indicative of the growing interest in using ML for flood forecasting and management studies.

The proliferation of machine learning methods in flood prediction applications has also led to several review papers in recent years [

14,

15]. However the emphasis of these reviews have largely been on prediction aspects. While predicting floods is indeed an important task, flood management also entails many other tasks such as ranking and prioritization of sites and susceptibility mapping. A review of machine learning usage in the context of flood management practices has not been undertaken to the best of the authors’ knowledge. The main goal of this paper is to fill this important gap that currently exists in the literature.

The lack of a suitable review of machine learning methods for flood management also suggests that there are likely several unexplored directions of research. Identifying these unexplored directions will stimulate new avenues of research and address those aspects where machine learning methods can offer benefits that have not yet been brought to fruition. In a similar vein, newer studies will also make machine learning models more congruent with the needs of flood risk management.

To achieve the above-mentioned goals, the rest of the paper is organized as follows - 1) The methodologies adopted in this review are presented; 2) A brief review of flood management paradigms is undertaken to help readers understand how flood management has shifted from a more command-control approach to a more holistic resiliency paradigm that not only seeks to mitigate flooding hazards but also help bounce back to the original (or a better) state upon the cessation of flooding. To properly evaluate the benefits of machine learning it is also important to assess the strengths and limitations of physics-based models which have been used in flood studies over a longer period of time. The main physics-based modeling tools available today are briefly reviewed along with their strengths and limitations next. This evaluation seeks to set the stage of evaluating machine learning models. For sake of completeness, machine learning models are briefly described and their role in flood management is explored in greater detail.

2. Methodology

While the primary focus was on machine learning applications over the entire gamut of flood management, presenting a brief evolution of risk management frameworks from command-control type approaches to a community-focused resiliency approach was deemed necessary to place the review in proper context. Physics-based models provide a theoretically rigorous approach to flood modeling and continue to be used today.

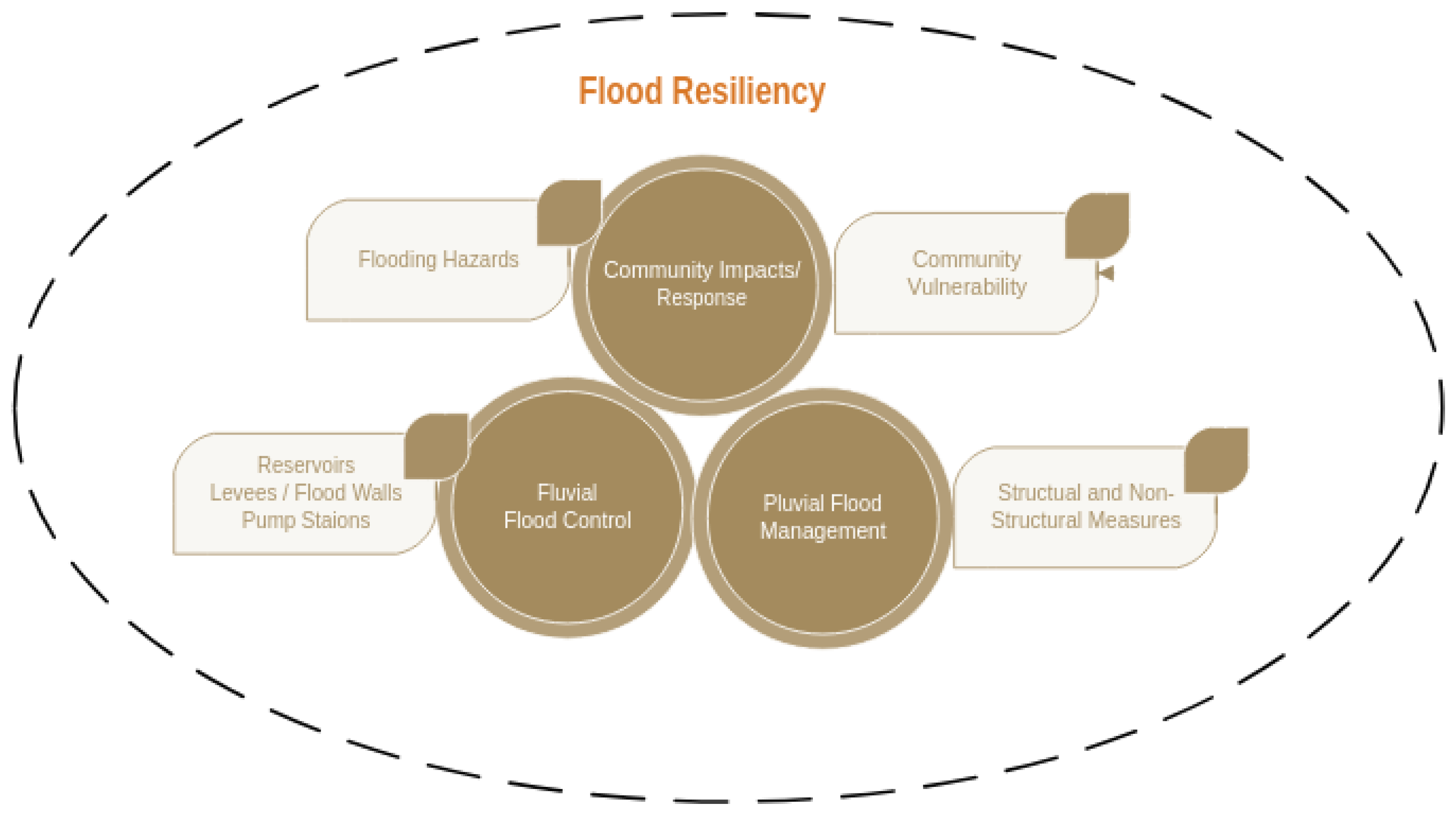

Figure 1, depicts the resiliency paradigm adopted in this study. Resiliency here is viewed as an umbrella of tools, technologies and policies that contribute towards a common goal of withstanding flooding threats or improving the ability of communities to quickly bounce back to normalcy or better after the flood.

Physics-based methods and machine learning methods are not competitors and can be used in a synergistic manner. Therefore, a brief overview of some commonly used machine learning codes were briefly reviewed here. While machine learning methods have gained popularity and wide-spread usage, these tools and methods are not routinely taught in water related curricula. Many decision-makers may be unaware of different types of learning algorithms that Machine learning offers. Therefore a brief overview of machine learning methods are also reviewed for the sake of completeness. A narrative review approach was adopted for these topics as the goal was to summarize key concepts and provide context and structure for a more comprehensive machine learning models across the flooding life-cycle [

16].

Having presented the conceptual life-cycle of flooding, a detailed systematic review of literature pertaining to each topic was undertaken [

17]. Major bibliographic databases - 1) Web of Science – Core Collecton 2) Scopus and 3) Google Scholar were utilized to identify over 5,000 references using a suite of key words such as - ‘flood reservoir inflows+ Machine learning”’ “Flood reservoir outlfows + Machine Learning”; “Flood Resiliency - Machine learning”. The search was constrained to a custom range of 2019 - 2025 (both inclusive) as the number of publications focused on machine learning have increased exponentially over this period, with many new advancements. The literature was trimmed down to those presented mostly in Q1, Q2 journals or in respectable conference proceedings such as IEEE conferences which undergo peer-review. The inclusion of conference proceedings were deemed necessary as some newer innovations particularly using sensors and ML appeared in such publications. Other journals were utilized when the paper had something unique to offer. The focus largely was on those publications that provided methodological advancements, rather than those which simply presented newer case-studies without any significant methodological contributions.

Given the vast and growing literature in this area, no claims of completeness are being made here. However, the review comprehensively captures major strands of research inquiry. The primary focus of this systematic review was to identify common themes and patterns in literature.

Figure 1 presents the definition of resiliency and major themes around which the review is organized. Drawing insights with regards to ML algorithms used and factors influencing their performance. As performance metrics tend to be site specific and affected by the quality of data, the focus was not on quantitative evaluations but on how the models performed overall, what challenges were faced across different aspects of the flood management life cycle and what the unexplored directions were. The focus was on identifying themes and creating generalization framework that will enable decision-makers, researchers and practitioners evaluate future studies using the frameworks and insights presented here.

3. Evolution of Flood Management Practices

3.1. Fluvial Flood Control

Early flood mitigation efforts were largely focused on controlling the harmful effects of flooding to humans and was based on the notion that flooding, while inevitable, could be fully controlled. Flood control projects were largely structural in nature and involved building large-scale facilities to store flood waters and both delay and attenuate the flood wave to protect downstream communities. Even today, riverine flood control structures provide the first line of defense against flooding waters arising from upstream areas. These structures include reservoirs, levees, flood walls and pump stations.

Reservoirs are constructed across a river and usually have extra free-board and sluice-and-gate mechanisms to control flooding. Levees are earthern embankments built alongside the river to prevent water from overflowing. River walls serve the same function as levees but are often built with concrete. Pump stations are used to pump excess water that is flowing out of the levees or flood walls and pump that water back into the river.

Despite several flood control projects being undertaken, flooding continues to be a problem in many parts of the world [

18]. Building new or scaling up existing flood control infrastructure is cost prohibitive and highly dependent upon the quality of hydrologic information that is available at the site [

19,

20]. The increased climate variability also adds uncertainty with regards to hydrological information and makes scale up of existing projects challenging [

21].

3.2. Pluvial Flood Management

With increased urbanization, the impacts of pluvial flooding became significant. The growing recognition that controlling fluvial flooding was alone insufficient and humans and the environment must be protected from pluvial flooding. Flood management now sought to create an environment where humans can learn to live with floods. Retention and detention basins, culverts and green infrastructure such as rain gardens, bioswales, blue roofs and enhanced infiltration systems (e.g., permeable pavement) prevent flood water from accumulating in residential areas [

22,

23]. In a similar vein, non-structural measures such as zoning laws that restrict development in flood prone areas, increase public awareness and employ early-warning systems to evacuate people to safer areas are also utilized [

24,

25,

26]. Rather than keeping the flood waters away from humans (as is the case with flood control), flood management also sought to keep humans away from flooding hazards. This approach of flood management was largely based on the notion of identifying the susceptibility of a land parcel to flooding (e.g., 100 year floodplain) and using that information to keep people away from flooding impacts through structural and non-structural measures[

27].

While coastal and riparian areas are prone to flooding, they also offer several other significant opportunities such as access to water-based trade routes, fishing and aquaculture operations and enhanced recreation activities. The number of people living in coastal areas have increased substantially over the last few decades with nearly 40% of the world’s population residing within 100 km of the coast [

28] and over 50% of the population within a few kilometers of a water body [

29]. Flood insurance programs provide safety net for people susceptible to flooding damages. These programs rely on risk assessments to evaluate the probability of a flood hazard that a person and/or infrastructure is exposed to in developing insurance policies and setting premiums.

While flood risks have been defined in multiple ways, using both qualitative and quantitative measures, widely used definition views flooding as a product of hazard, value and vulnerability [

30]. Hazard characterizes the threatening event including its probability of occurrence, the values or (values at risk) denote humans, infrastructure and other assets that present at a location and vulnerability is the lack of resistance to withstand the damaging forces of the hazard causing event. Flood risk management uses the risks of flooding hazards as the basis for management and seeks to develop structural and non-structural measures that mitigate the effects of hazards to acceptable levels of risks [

25].

3.3. Resiliency-Based Flood Management

While floods do cause damages to both humans and the environment, they are important for sustaining river and floodplain ecosystems. Floods transport fine sediments and energy required for riverine flora and fauna. In addition, the disturbances created by flood and droughts are essential for fostering ecological biodiversity [

31,

32]. The ecological importance of floods is no longer a theoretical construct but has been integrated with reservoir operations for flood control [

33]. Flood management is transitioning from human-centric approaches towards more holistic frameworks [

34].

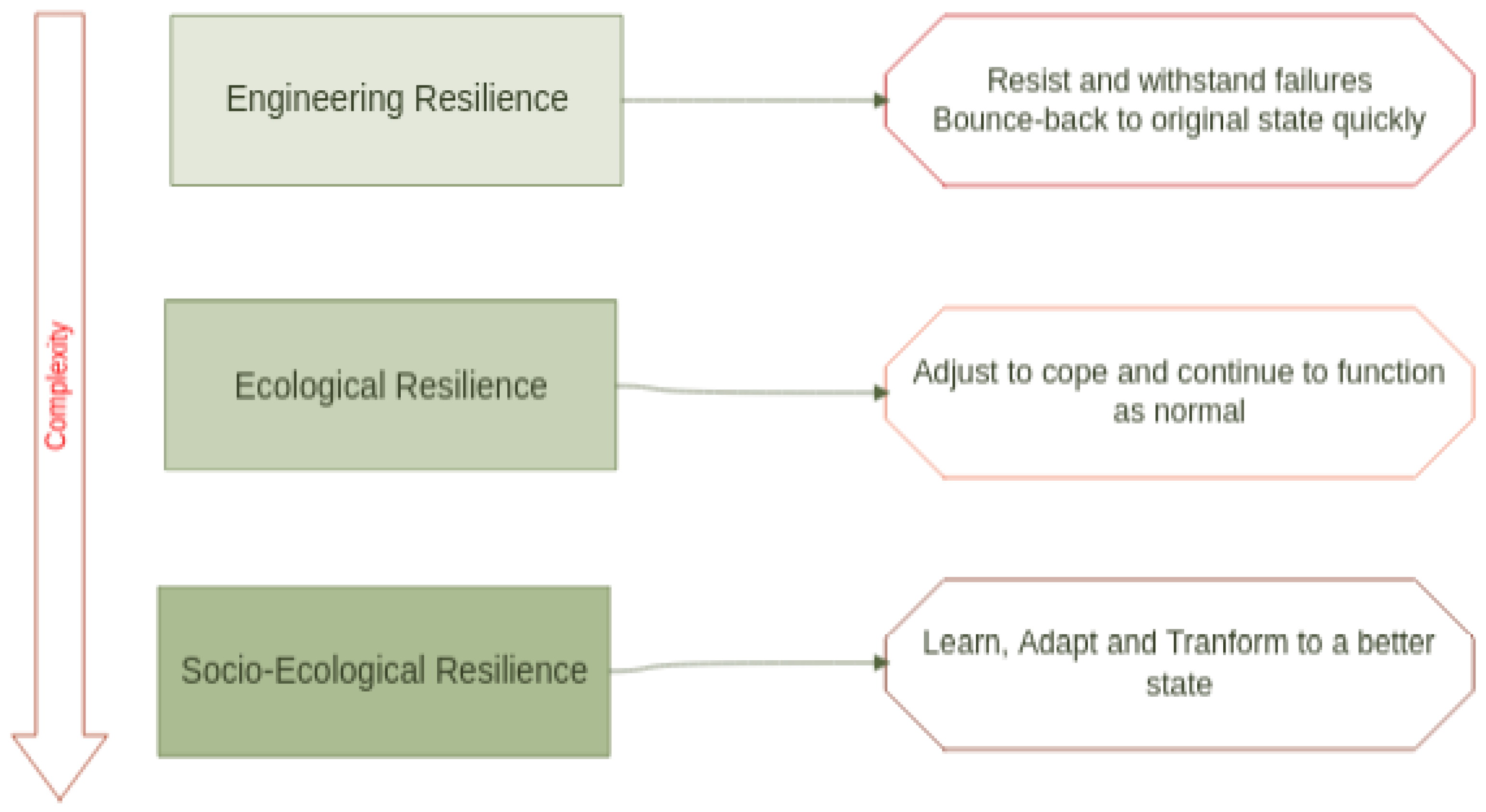

The recognition of the importance of flooding for the functioning and sustainability of vibrant riparian ecosystems coupled with the inadequacy of flood control strategies, the movement of flood mitigation from being a command-control type engineering endeavor to a more stakeholder-driven, participatory community-based effort has brought to light the concept of flood resiliency. While the definitions of flood resiliency continue to evolve [

35], the synthesis of resiliency definitions from a wide range of disciplines provided by [

36] has seen widespread usage in resiliency-based flood management studies [

37,

38]. In this approach, flood resiliency approaches are categorized into three types - 1) Engineering resiliency; 2) Ecological resiliency and 3) Socio-ecological resiliency (see

Figure 2). While the words engineering, ecological and socio-ecological are used in this approach, they are not domain-specific and have been used in diverse systems and applications [

37].

The main idea of engineering resilience is to create systems that can withstand hazards and not fail. If and when failure does occur, these systems need to bounce back to their original (pre-flooding) stage quickly. The traditional design of hydraulic infrastructure is based on the idea of engineering resiliency. The concept of return period (or the average time of recurrence of a flooding event of a certain magnitude or higher) is used for design of structures that aim to control floods (dams and levees), mitigate their effects (detention and retention basins) or otherwise interact with floods (e.g., bridges) and suitable for use in single systems [

39].

The ecological resilience typically is applied to a system with multiple interconnecting parts. This allows the system to adjust and cope with flooding hazards. For example, early warning systems allow people to procure supplies in advance, take other precautionary measures (e.g., evacuate to a higher elevation) to cope with short-term floods. The socio-ecological resilience focuses on complex-adaptive systems (or a system of systems). Here the system may not come back to its original state but adapts and transforms to a better state. For example, relocation of people out of the floodplains to areas with lesser inundation risks are undertaken after many devastating hurricanes [

40].

It is important to recognize that flood resiliency is not independent of flood control and flood risk management approaches. Rather, the resiliency paradigm subsumes both flood control and flood risk management concepts. From this viewpoint, the resiliency provided by flood control and risk-based structural and non-structural alternatives is evaluated and improved upon in most flood resiliency endeavors so as to benefit from past investments in flood planning and course correct in light of new information [

38]. While the goal of any flood planning endeavor is to minimize the risks of flooding to humans and the environment, socio-ecological resiliency based planning and management challenges to think outside the box and evaluate if converging to a new equilibrium is better (or worse) than trying to get back to the original state.

Regardless of the methodology adopted, flood management is a costly endeavor that requires considerable investments in infrastructure and a time-consuming process where diverse and often conflicting views and values have to be reconciled effectively.

4. Physics-Based Models for Flood Management

Quantitative information is paramount to flood management. Estimates of runoff, streamflows, the nature and extent of inundation, the frequency and magnitudes of extreme rainfall are therefore a major component of flood management endeavors. It is not only important to analyze historical floods but also develop robust estimates for future conditions, especially given the recognition that past climate is not necessarily a good indicator of future flooding events [

41]

Mathematical models used for flooding can be categorized as - 1) White-box models, 2) Grey-box models and 3) Black-box models. White-box models are most rigorous and employ mass, energy and momentum conservation principles. Grey-box models are based on the conservation of mass principle, along with empirical laws to describe flooding. 3) Black-box models are completely empirical and built on site-specific data.

Both white-box and grey-box models are referred to physics-based models as they are based on physical principles. The development and application of these models dates back to at least 100 years [

42]. Physics-based models can be developed for a wide range of systems such as, streams and rivers, watersheds, reservoirs and wetlands. In addition, they can be developed to study combined interactions like - climate-hydrology dynamics [

43], human-water linkages [

44] and food-energy-water nexus [

45].

Flood planning studies often employ more than one model. For example, a conceptual hydrological model can be used to model fluvial flood discharges into a stream, while a hydraulic routing model can be used to study fluvial flooding. When multiple models are used, they can be loosely-coupled (meaning the two models are separtely run) or tightly-coupled (one software allows running of all the models with seamless data transfer between them). The application of physics-based models entail many aspects. Salient modeling considerations are presented in

Table 1

Several software simulators have been developed by various agencies to support flood management. Widely used software simulators are presented in

Table 2. A wide range of engineered and natural systems pertaining to flood control can be modeled using these software at varying levels of complexity.

4.1. Shortcomings of Physics-based Models

While physics-based models offer great theoretical rigor, their implementation is challengng on several fronts. Physics-based models contain model inputs that cannot be directly measured. These parameters have to be estimated indirectly from available observations. The process of obtaining unknown model inputs using observed outputs is called the inverse-problem in mathematics or calibration in hydrologic literature. The inverse problem is mathematically ill-posed and therefore does not yield unique solutions. In other words, different subsets of model inputs can result in similar output predictions [

46]. Typically available hydrologic records at most sites only allow reliable estimation of a few parameters [

47]. Efforts to improve model calibration has focused on using expert knowledge to guide calibration [

48] and/or regularization schemes that seek to restrict the number of calibration parameters during calibration [

49,

50], using other surrogate information [

50] to guide calibration, using ensemble methods [

51] to construct confidence bounds by employing parallel computing approaches [

52]. However, these improvements still largely remain in the theoretical regime and not widely used in routine flood management studies. Sensitivity and uncertainty in model outputs due to uncertainty and variability of inputs is recommended to understand limitations of estimates like inundation obtained from physics-based models [

53].

As physics-based models require calibration, their usage in ungaged basins becomes even more challenging due to lack of long-term output data [

54]. Regionalization approaches are often employed to overcome this limitation. Calibrated data from nearby, and/or, similar systems are scaled for use in the ungaged basin [

55,

56]. Scaling of hydrological phenomena is however non-trival and the success of regionalization depends upon the amount of informative content that is present to facilitate scaling [

57]. Nesting ungaged watersheds within gaged watersheds is beneficial if the gaging density of the larger watershed is sufficiently high [

58].

The ability of physics-based models to capture flood peaks is also of concern. This limitation stems from several factors - 1) Most flood models operate on a time-step of days and months due to availability of rainfall records at those scales. However, flooding is a much more dynamic phenomenon that causes changes in flows in the order of minutes to hours. The coarse temporal discretization limits the ability of the model to capture fine-scale changes [

59]. Models make several other approximations to simulate various hydrological processes, these simplifiations do well in capturing general trends, but cannot adopt to sudden changes in flow regimes [

60]. 2) The Root mean square error (RMSE) or its variant, the Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) are widely used for model calibration. Minimization of this metric entails a trade-off in capturing a large number of low-flow events and relatively few high-flow events which often leads to over-estimation of low flows and under-estimation of peak flows. The use of newer error metrics like the Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) [

61] can ameliorate this impact [

62]. 3) The amount of data available also impacts the abiliy capture peak flows [

63]. Clearly, errors in flood forecasts induces uncertainty in flood planning and management.

5. Machine Learning Modeling - Background

The limitations associated with physics-based formulations coupled with recent and rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has increased the exploration of machine learning methods in applications focused on flood management. Machine learning models are not new, the term was coined by Arthur Samuel back in the year 1959 [

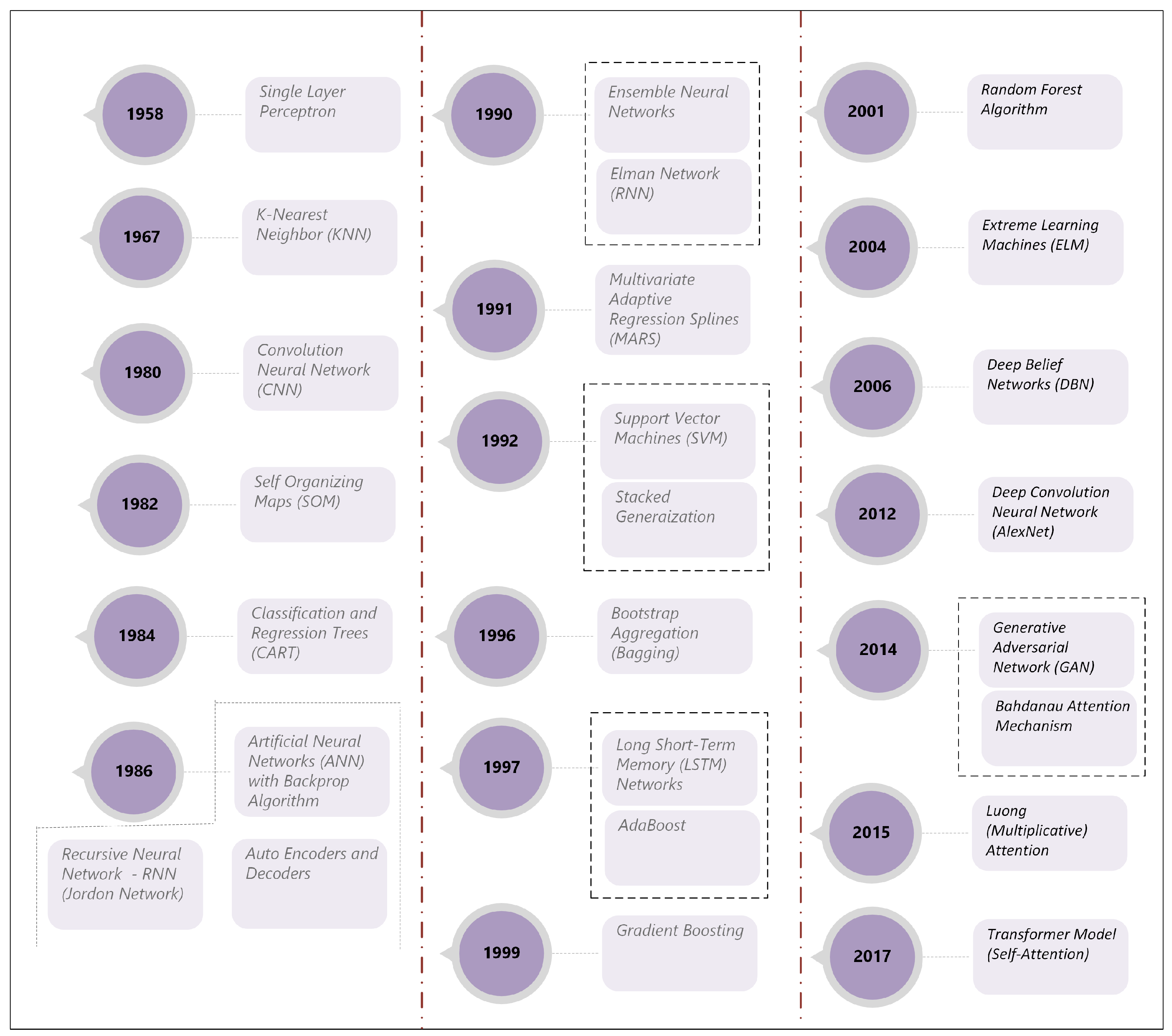

64]. A timeline of major advancements in machine learning is presented in

Figure 3. Algorithms developed in the 1960s such as K-nearest neighbors (KNN) are in use even today [

65].

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) have been around at least since mid 1980s and some of the early application of this technique for streamflow forecasting dates back to early 1990s [

66,

67]. In a similar vein, an early application of tree-based learners for flood studies can be traced all the way back to 1992 [

68]. The number of applications of machine learning models has shown steady increasing pace through 1990s - 2010s congruent with algorithmic developments in this period.

In recent years, the number of papers has grown exponentially given the large-scale availability of data, general purpose libraries such as Scikit Learn [

69] and Tensorflow [

70]. Computational power has also increased significantly in the last decade with the availability of graphical processing units (GPU) and Tensor Processing Units (TPU) on some platforms. Unlike conventional central processing units (CPU), GPU support parallel floating point operations (FLOPs) that speeds up large-scale computations. TPUs utilize a grid of parallel processing elements through which computations are processed in a synchronous manner.

Prior to reviewing the use of machine learning for flood management, a brief overview of major learning strategies employed is presented to contextualize their utility in flood management studies.

5.1. Machine Learning Strategies

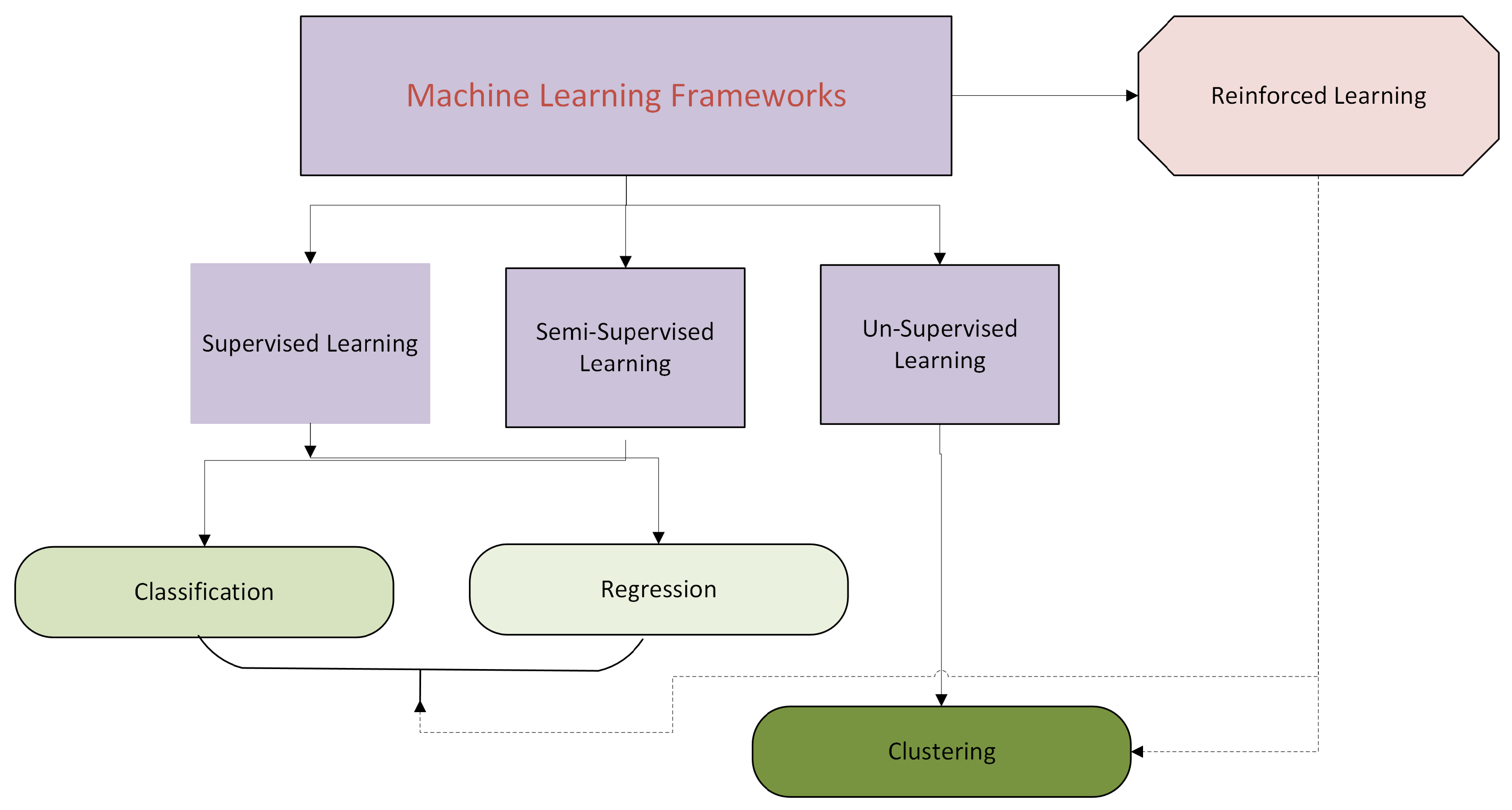

As shown in

Figure 4, the four main types of ML are – supervised learning, semi-supervised learning, unsupervised learning and reinforcement learning. In supervised learning, a ML model is trained using a datasets that has both the inputs (features) and the output (labels). Outputs can be continuous or discrete. Supervised learning methods that employ discrete labels are referred to as classifiers, while those mapping continuous labels are called regressors. Unsupervised learning on the other hand is trained on a dataset that has no labels and is often used to cluster data. Semi-supervised learning uses a dataset where there are some data with labels and others without labels. This approach can be used for both classification and regression tasks. Reinforcement learning (RL) focuses on developing a long-term (operating) policy that maximizes long-term reward , while RL algorithms can in theory be used for classification, regression and clustering tasks, they are not specifically designed with these applications in mind, but are better suited for decision making and control [

71].

Humans use different approaches to learn information. Cognitive approaches focus on using past experiences and knowledge for making decisions and solving new problems. These strategies can range from simple memorization of facts, forming rules of thumb to guide decisions. In a similar vein, humans also decide when to learn what information, evaluate and discern among competing pieces of information to make a decision based on the weight of the evidence provided by them. Human decision making is not always individualistic but involves collaboration (bagging) with peers and partners. Humans also exhibit the ability to build and improve on their previous experiences (boosting). Machine learning models that try and mimic the cognitive capabilities of humans can be categorized as cognitive-inspired machine learning (CIML) approaches.

Biological adaptations modify how stimuli (data) are sent to the brain (central processing unit) and how they are processed to create new information. Evolutionary changes happen over longer time-scale and change the biological makeup to improve survival. On shorter timescales, humans (living beings) also exhibit the ability to change their physical and neurological conditions to adapt to new conditions, learn new skills or adapt to a new environment. In particular, the brain can reorganize and form new neural connections – this phenomenon is referred to as neuroplasticity and a key mechanism by which the brain adapts to new information and environments.

Neuroplasticity plays a key role in memory, mortar learning and helps recover from brain injuries and is controlled by the nature of the stimuli [

72] Machine learning models that mimic evolution and/or the structure of the nervous system and the functioning of the brain can be categorized as biologically-inspired machine learning models (BIML).

A variety of machine learning models have been developed over the last seven decades (see

Figure 4). Learning strategies provide a quick way to understand the broader ideas related to machine learning algorithms.

Table 3 provides a grouping of machine learning algorithms based on their learning styles.

More than one learning strategy presented in

Table 3 can be adopted for a given task such as mapping nonlinear input-output relationships.

5.2. Calibration of Machine Learing Models

Machine learning models are empirical in nature, therefore the model parameters are unknown and have to be determined via calibration, particularly in the case of supervised learning. In unsupervised learning, there is no calibration per se, but distance between points within a cluster are minimized while the distance between two independent clusters are simultaneously optimized. While physics-based models are often calibrated using both automatic (optimization-based) and manual methods, machine learning models are calibrated almost exclusively using automatic optimization based methods. In case of supervised classification, an error metric, such as the root-mean square error (RMSE) is minimized. The objective function that is minimized is commonly referred to as the loss function in machine learning literature. Similarly, the calibration of the supervised learning model is referred to as training the model.

Typically, the calibration of a supervised ML is carried out by splitting the available dataset into two parts. The first part is called the training dataset which is used to train the model and the second part the testing dataset. The training dataset is used to obtain unknown model parameters (e.g., weights of neural network) by minimizing a loss function. The performance of a model is then assessed by comparing the model predictions against the testing dataset that contains data that the model has not seen before. ML model algorithms also have a set of parameters that are necessary to define the structure of the model or to implement the optimization routines necessary for model calibration. These parameters are called ‘hyper-parameters’.

Hyper-parameters are either set based on previous studies, but most often are estimated (optimized) during the calibration process. When hyper-parameters are optimized as part of the training process, the training dataset is further divided into two parts – Training Data and Validation dataset. The training dataset is used to train the model, the validation data is initially used to test the performance of the training under a given set of hyper-parameters and select their optimal values. Once the hyper-parameter values are identified, the validation dataset is subsumed into training dataset and a final training is performed on the model. Validation datasets are also useful for early stopping (i.e., when the validation error increases even when the training error is decreasing as training progresses. Similarly, the validation dataset can be used to select the best model for a subset of models or use the validation error metrics to weigh different models within an ensemble.

Typically, the dataset is randomly split into training and testing subsets. In case of sequential data (e.g., time-series) the first part of the data is used for training while the latter part of the data is kept aside for testing. Train-testing splits of 70%-30% or 80% - 20% are common. Typically, 10% - 20% of the training data is used for validation.

Overfitting occurs when a model is able to predict the training data very well, but demonstrates a rather poor performance on the testing (independent) dataset. Overfitting generally implies the model has too many degrees of freedom(parameters) than necessary. Thus the model is able to learn the noise in the data, rather than focus on generalization. Overfitting can also occur with hyper-parameters. The validation dataset is used to avoid overfitting of hyperparameters. Regularization methods are widely used to prevent over-fitting, a regularization function adds a penalty with increasing weights, which causes the model to effectively drop some weights during the calibration to reduce the penalty on model performance. Overfitting is more likely in deep neural network models due to their complexity and more aggressive approaches such as dropout (where certain nodes are dropped from training with a certain probability) are used to prevent over-fitting.

Training of supervised learning models typically occur by sending small batches of data through the model to adjust weights. Each run with a model is called a training epoch. The stochastic gradient descent algorithm (SGD) is commonly used for model calibration [

73]. Automatic or Algorithmic differentiation (AD) is widely used to compute gradients without significant numerical errors [

74]. These gradients are used to identify newer estimates of parameters which reduce the loss function to the lowest possible value. However, in deep neural networks, the gradients of weights of early layers practically become zero (i.e., vanish) making the training using conventional gradient descent ineffective. Greedy learning uses layer-by-layer training to eliminate the effects of vanishing gradients and effectively training deep networks. Greedy learning approaches are also used in other ML models such as random forests and gradient boosting methods [

75].

5.3. Explainable Machine Learning

While machine learning models can provide accurate predictions and map highly nonlinear input-output relationships, interpretability of the model is a major limitation. In this regard, physics-based models and statistical models (e.g., linear regression) perform much better as the model equations and parameters can be readily interpreted.

Explainable machine learning (XAI) is a rapidly emerging field of ML that seeks to improve the understanding of the inner workings of ML models. XAI provides several benefits, most important of which is the increased trust in using this models in mission critical applications such as flood forecasting. XAI also helps evaluate if the model is based on biased data and help debug the models and improve their work.

Some AI techniques such as CART, MARS and Genetic Programming (GP) encode information in the data as rules and equations and therefore are readily interpretable. As boosting and bagging methods create multiple models with the same dataset, the relative importance of different parameters can be ascertained even if the model equations are not explictly known per se. Tree-based algorithms are also used to explain other hard to interpret models [

76]

Neural network models (particularly deep learners) encode the information in terms of weights that are hard to interpret. In such cases, the outputs obtained from the model are explained by fitting local (explanable) models around the predictions – The Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) that uses game theoretic measures to explain the importance of different features on the output and the Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) based on linear regression around the predictions are commonly used to explain which inputs are important and how they affect a particular model output [

77].

Having presented a broad overview of machine learning methods, the application of these techniques in flood risk management are explored next.

6. Machine Learning for Flood Resiliency

6.1. Machine Learning for Fluvial Flood Control

6.1.1. Machine Learning for Reservoir Operations

Reservoirs store excess water during high flow events and release them during periods of high demands. The controlled release of flow out of the reservoir is to ensure there is minimal downstream hazards, but also is constrained by the capacity of the reservoir and associated infrastructure. Therefore, the outflow of the reservoir is a function of the water height in it. Reservoir operation rules (ROR) are used to define outflows. Operation rules tend to be complex, especially when there are multiple interconnected reservoirs, and they are only known to a few practitioners.

Machine learning models have been used to infer reservoir operating rules and predict outflows. A wide range of machine learning approaches including artificial neural networks (ANN), Support vector machines (SVM), random forest (RF), deep neural networks (DNN) and recurrent networks, especially the long short-term memory (LSTM) network have been adopted for this purpose [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85].

The main synthesis of these studies is that machine learning learning models provide better predictions than conventional tools (e.g., statistical models such as ARIMA or water balance formulations). Deep learners, especially LSTM and GRU (gated recurrent units) provide better predictions than other techniques in most, if not all, cases. However, there is no universal consensus on which model always provides the best results. Different models may perform well at different sites within a river basin. Therefore, assessment must always include multiple models to select the most optimal of those tested.

Reservoir inflows are key input to these models and the quality of the output depends upon the quality of the inflow data. Note reservoir inputs can be natural streamflows or controlled releases from an upstream reservoir (these reservoirs may or may not be explicitly modeled). While treating upstream reservoir releases as inputs simplifies the outflow predictions at downstream reservoir, explicitly modeling the releases of these upstream reservoirs is shown to improve model predictions due to better accounting of lag-times of flows [

86].

Most studies focus on modeling monthly or daily outflows although efforts are beginning to be made to develop sub-daily streamflow time-series to improve streamflow forecasts [

87]. Most models provide 1-step ahead forecasting with many providing 2-, 3- and multi-step ahead forecasts. Real-time forecasting is also being attempted using machine learning [

88].

Statistical metrics such as the root mean square error (RMSE) are used as the objective (loss) function to minimize the errors between observed and modeled outflows. However, recent efforts have focused on including other information to help guide the calibration process. A mass conserving LSTM (mc-LSTM) model has been presented as well [

89]. Loss functions have been modified to include conservation relationships as well as other information such as reservoir operation rules [

85,

90]

While recurrent and non-recurrent neural networks (e.g., LSTM, GRU and ANN) appear to provide better forecasts than most other models, the derived operational rules are abstracted as weights and thus not readily interpretable. This issue if not of concern if forecasting is the only goal of the model. However, interpreting the model results and which inputs have bigger impact on the output are useful to evaluate the performance of ML models (esp. those that behave like black boxes).

Scenario-based sensitivity analysis, and XAI methods like the Shapely Additive Explanations (SHAP) are being employed to understand how ML model inputs affect reservoir outflows[

90,

91]. Results from these studies suggest that while XAI results make hydrological sense in most situations, there is no guarantee of this over the entire range of outputs [

91]. An evaluation of whether ML models trained with physics-based or operation-based loss functions explain the results better is an interesting, but unexplored direction of research.

Reservoir inflows are critical to properly predict outflows. In forecasting applications, reservoir inflows have to be estimated to make future predictive runs.

Therefore, considerable interest also exists in using machine learning for modeling reservoir inflows [

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108]. These models mainly focus on daily time-step, but both monthly and sub-daily time-steps are also predicted depending upon the needs of the problem.

The synthesis of reservoir inflows using machine learing bring about several distinct insights - 1) These models use meteorological variables such as precipitation, temperature, wind speed and their lags. 2) Atmospheric teleconnections such as El-Nino-Southern Oscillations (ENSO); Noth Atlantic Oscillations (NAO), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and Arctic Oscillation (AO) are also being employed. These teleconnections correlate with several reservoir inflow processes such as rainfall, evapotranspiration, and snowmelt. 3) There is a greater propensity to combine multiple models, rather than rely on a single algorithm such as LSTM. 4) Rather than utilize an ensemble mean (EM) most studies utilize stacking ensemble (SE) wherein different parts of the dataset are predicted by different model subsets. This occurs because, some models provide very high extreme values which bias the overall ensemble mean. 5) It is more common to see fused traditional and deep machine learning algorithms as well as statistical models such as ARIMA for reservoir inflow forecasts.

Reservoir inflow estimation is often fraught with uncertainty. These uncertainties can be random due to changing weather pattern, land use alterations as well as climate change. The ability of the model to capture extremely high inflows is critical in flood management applications. While ML models may perform better than traditional physics-based models for forecasting streamflows, they are not perfect nor without limitations. Model stacking and ensemble approaches may help with predictions, but also can potentially average down extreme forecasts. Explicitly capturing this uncertainty alongside point estimates adds value to the estimation process as it informs the decision maker of what is more likely estiamates and what are all plausible values. Therefore, many studies are exploring the use of uncertainty quantification methods such as Bayesian Deep learning, Bayesian networks, fuzzy logic and other heuristic models [

48,

92,

106,

107,

109,

110].

Despite growing number of publications in this area, propagating uncertainties in reservoir inflows through single and multi-reservoir operations is clearly a largely unexplored direction and of considerable practical significance.

6.1.2. Levees and Floodwalls

Levees and flood walls are structures built along the river to keep flood waters from flowing into the adjoining floodplain. While levees and flood walls serve similar purposes, the former is built using earthen materials, while the latter is built using concrete.

While applications of machine learning algorithms to study levees have been limited (see

Table 4, they have tackled most challenging problems related to the resiliency of levees to withstand failure. Machine learning has been used to evaluate failure risk due to overtopping, compaction and liquifaction and piping. Cracks and other early warning signals such as the formation of sand boils which indicate piping due to liquifaction have also been studied. Manual inspection and ground penetrating radar (GPR) are two common approaches to evaluate hazards in these systems. Both of them are expensive and time-consuming, therefore automated detection using drones and use of transfer learning algorithms to enhance the value of limited GPR based surveys have also been explored using machine learning methods. Deep neural networks such as Convolution Neural Networks (CNN) and Viola-Jones object detection method which is based on the boosting technique have shown promise for evaluating drone-based surveys. Conventional neural networks such as ANN, SVM, Naive Bayes and others have been useful to predict risk of failures.

The United States alone has over 24,000 miles of Levees and the average age of these levees is 51 years [

117]. As such, many of the levees are in need of rehabilitation and most levees were not designed for modern climatic conditions. The review of literature indicates that while attempts have been made to evaluate levee failure risks using machine learning, this is another largely unexplored area as far as flood resiliency is concerned.

The National Levee Database (NLD, 2025) [

117] provides the best publicly available information to understand levee performance. Efforts to compile a larger dataset of images pertaining to levee failures, along with hydraulic, geotechnical and geophysical characteristics would be a useful addition to facilitate further research in this area.

6.1.3. Pumping Stations for Flood Control

Pumping stations offer the third line of defense in flood control. Pumps are used to remove any excessive water and pump it back into the river. Machine learning has been utilized to model this system. Lee and Lee (2022) utilized multi-layer perceptrons (ANN) to simulate the discharge from pumping stations using previous rainfall and discharges [

118]. They conclude that while the method was useful, the study could have benefited from having inflow data into the pump stations as one of the inputs. Wang et al.,(2023) applied ANN, SVM with different evolutionary optimization techniques to study inflows into a pumping station along different time periods. They made use of water levels at other pumping stations, rainfall and human factors to develop different models that showed a high degree of accuracy in their study area [

119]. Kow et al., (2024) [

120] utilized transformer based LSTM (T-LSTM) to abstract pump station operating rules using rainfall and flows from upstream stations. The use of transformers assisted in capturing the seasonality in the operations and provided excellent results both for typhoon and convective storm events. Joo et al., (2024) [

121] combine gated recurrent units (GRU) with deep-Q reinforcement learning to simultaneously minimize water levels in the retention basin and the number of pump switches over the entire storm duration. Their results indicate that this combination is useful to improve operations of pump networks used in flood control.

While traditional methods for operating pump stations using physics-informed models and traditional optimization routines continue to be in use [

122], efforts have started on exploring the use of machine learning models for predicting inflows, outflows and operation of these pumping stations. Pump stations help reduce flooding risks to humans and the environment but can also cause changes to local hydrology as well as affect riparian and riverine habitats due to changes in dissolved oxygen [

123]. Therefore proper operations of these systems is critical. While the use of machine learning shows great promise, the lack of open-source datasets, limits the number of researchers who have access to such data, which in turn hinders a deeper exploration of this topic.

6.2. Maching Learning for Pluvial Flood Management

6.2.1. Pluvial Flood Estimation

Machine learning methods have been widely used in pluvial flooding studies [

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143,

144,

145].

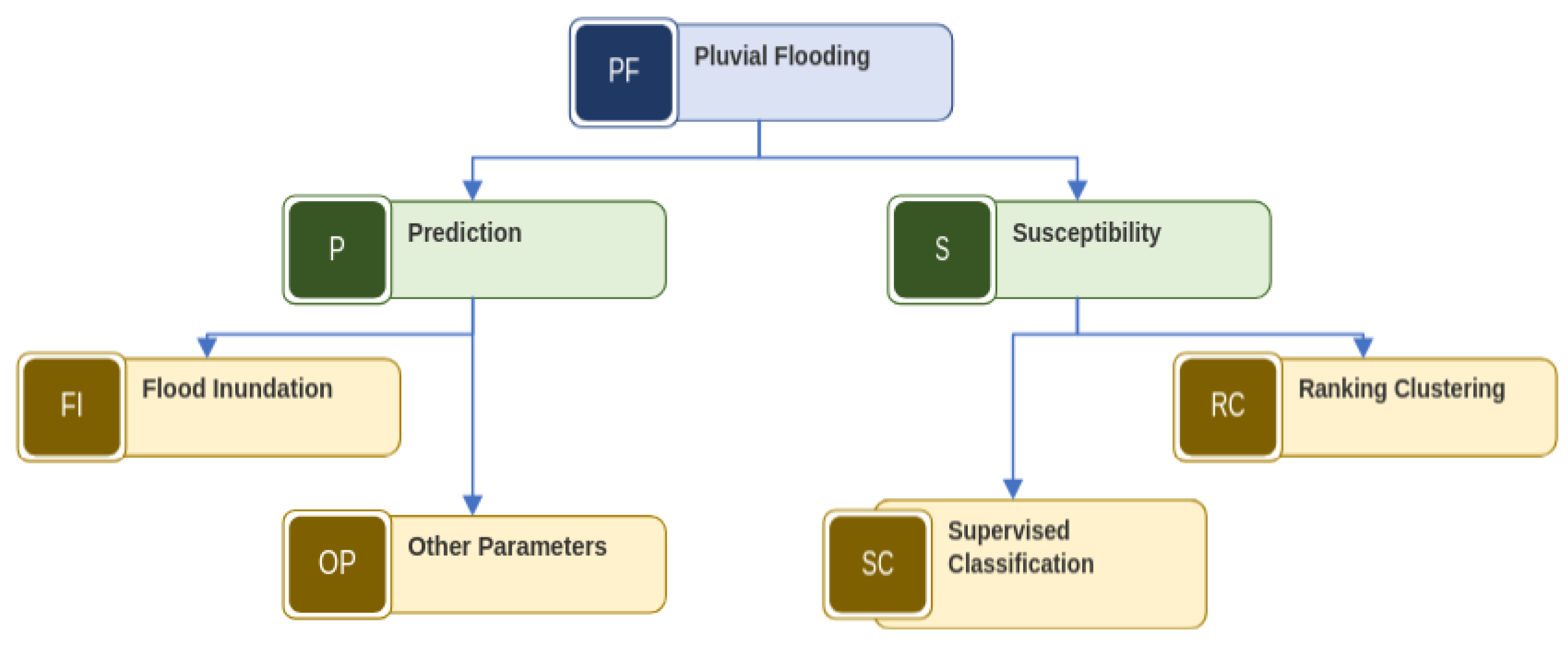

Figure 5 explains the primary goals of these machine learning models in pluvial flooding studies. These studies either focus on predictions of flood characteristics or susceptibility mapping of flood prone areas, mostly in urban environments.

The analysis of the literature pertaining to the use of machine learning for pluvial flooding demonstrates that a wide range of machine learning methods have been used in various applications. Among the traditional machine learning methods logistic regression (LR), artificial neural networks (ANN), support vector machines (SVM) and k-nearest neighbor (KNN) algorithms show greater use. Ensemble methods such as random forest (RF) and XGBoost have also been used extensively. Among the deep learning algorithms, convolution neural networks (CNN) stands out prominently. While all these models provide good results, there is no clear identification of which one is best.

The use of supervised ML methods in pluvial flood forecasting can be broadly categorized into two groups - 1) Classification methods are used to predict flood/no-flood zones using a suite of inputs such as precipitation, land use type, elevation and others. The labels (output) is obtained either from observed data within an urban area that is either collected by municipalities and/or those reported by citizens through navigation apps such as WAZE. The latter is useful for understanding flood prone roads and other transportation infrastructure.

Unsupervised methods, such as fuzzy clustering, have been used to categorize an area’s susceptibility to flooding. Such classifications can help data collection activities to develop supervised classifiers in the future. The depth of the water level in urban areas following a rainfall event as well as the extent of inundation in floodplains are also important aspects of pluvial flooding. As urban areas are typically ungaged, this information has to be obtained via simulation or using satellite remote sensing [

146,

147,

148].

Machine learning methods have been widely used to abstract the results from physics-based models (i.e., flooding depth, inundation extent) using surrogate measures such as rainfall intensity, land elevation and other characteristics. Again, a suite of conventional and deep learners have been employed for this purpose that have yielded good results. Once trained, machine learning models are easier to run and different scenarios can be evaluated to guide flooding planning and emergency management efforts. However, as ML models depend upon data from physics-based models, their accuracy cannot be greater than those obtained via physics-based simulators. Therefore, integrating physics-based simulations with satellite data can improve prediction methods, especially using interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) and other remote-sensing products. A case-study of such integration is presented in [

148].

One important aspect of pluvial flooding is the heterogeneity of datasets. For example, rainfall hyetographs are 1D temporal data, while digital elevation models are 2D (raster data), high water marks are points in 2D space (vector data). Simulation models can produce data in 1D or 2D in space and over time. Transportation infrastructure is usually multi-line data (line vectors). Assimilation of such data from diverse sources is an important ancillary topic that is beginning to be explored [

149,

150].

Estimation of pluvial flooding characteristics, particularly inundation depth and extent using physically-based tools is rather difficult to paucity of data for model validation. While several studies have demonstrated that the output of such models can be captured using machine learning methods, the ability to transfer such learning to other sites via transfer learning approaches is another interesting area that has received little attention [

151] and offers significant opportunities to improve flood risk management in other areas. In a similar vein, while the use of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) methods such as SHAP have been demonstrated in the literature [

134], their usage is still limited and offers a significant potential to eludicate factors affecting pluvial flood risks.

6.2.2. Machine Learning Approaches for Low Impact Development

Low impact development (LID) aims to develop stormwater infrastructure within urban areas that largely mimic natural hydrology by enhancing infiltration, supporting vegetation and enhancing water quality. In many US cities, they are part of the Municipal Separate Storm Water Systems (MS4) and permitted to discharge water from urban areas to natural water bodies. Environmental permits not only emphasize the rate and volume of discharges but also place restrictions on the quality of the discharging water. Therefore, contaminants of concern (CoC) often control their design and operation even if their primary goal is to remove flood waters from roads, residential neighborhoods and other business districts and keep pluvial flood waters away from humans.

Machine learning models are being used to design and operate many LID features and understand their functioning. Complex physics-based formulation can be approximated using machine learning and used with multi-objective optimization for sizing LID practices[

152]. This approach greatly reduces the computational time to obtain good optimal solutions.

Deep reinforcement learning are widely being used to operate (control) stormwater treatment systems to mitigate flood flowrates and associated contaminant movement. Reinforcement learning is noted to help achieve real-time control under uncertainty [

153,

154,

155].

Integration of machine learning with other ancillary technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), physical-model simulations and remotely-sensed datasets open new avenues to model the performance of stormwater systems, develop better designs and monitor LID systems [

156,

157]. Emerging studies indicate the promise of such integrations and this is another fertile area for further exploring the role of machine learning.

Predictions of water quality outflows from LID stormwater systems is of interest to decision makers to ensure they are within compliance. Machine learning models have found uses in capturing and correlating highly complex water quality transformations occurring within LID to easily measured surrogate data such as rainfall, temperature, sunlight and others. A variety of modeling algorithms have been evaluated and demonstrated to provide good results. Algorithms tested include, but are not limited to, ANN, SVM, KNN, Random Forest, Generalized linear models (GLM), Partial least squares (PLS) and deep learners [

158,

159,

160,

161,

162]

While ML models show high potential to predict water quantity and quality parameters in stormwater control and treatment systems, there is no single approach that stands out. The quality of predictions varies among models so experimentation with a candidate set of models is often required. Conventional machine learning models (ANN, SVM) do better than deep learners in some cases, especially when the amount of data available for calibration and testing is small. In addition to variability across models, a particular algorithm my be better suited for one water quality parameter but not another. This result indicates that some ML schemes are able to better assimilate certain fate processes than others that affect the quality of stormwater. However, the success of ML models to predict emerging contaminants such as microplastics, indicates their high potential to predict contaminant concentrations whose mechanisms of biochemical transformations are not completely known [

162].

While ML algorithms show promise for modeling urban stormwater infrastructure, there are many unexplored research directions. The use of explainable machine learning (XAI) to understand the predictions of ML models, especially to understand fate and transport of emerging contaminants has potential to develop fundamental insights on pollutant behavior using machine learning. Evaluating the use of stacked and ensemble learning methods, and integrating physics-informed loss functions are some easier implementations that have not been undertaken to-date to the best of the authors knowledge and offer some useful avenues to explore.

6.3. Machine Learning and Flood Resiliency

A significant amount of research focused on the resiliency of communities to flooding risks is beginning to emerge in the last few years and a large sampling of such studies, particularly those using machine learning approaches are summarized in

Table 5. A synthesis of these studies depicts a common theme which is presented in

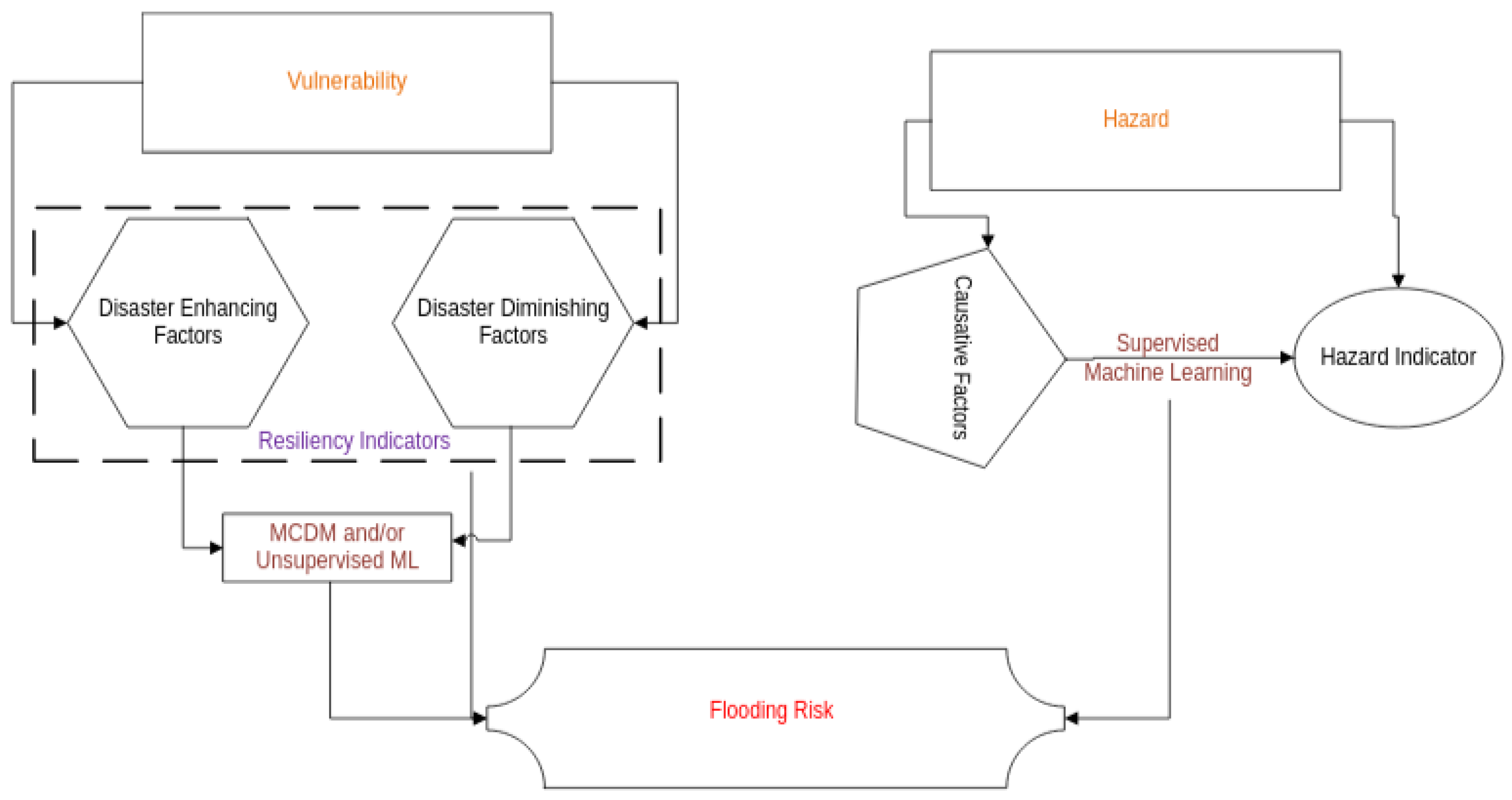

Figure 6.

Resiliency is measured as the extent of vulnerability of the community to withstand flooding hazard. Higher the vulnerability, the lower the resiliency of the community. Vulnerability captures the demographic, economic, geographic and engineering factors such as the population density, the nature and extent of economic activity, land elevation and distance from flooding features such as streams and engineering measures such as distance to pumping stations and other stormwater conveyance features.

Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) approaches are used to aggregate such factors into a composite index. A suite of MCDM approaches such as the Simple Additive Weighting (SAW), Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), VIKOR, ELECTRE and others have been utilized for this purpose (see [

182,

183] for an overview of these techniques). Briefly, MCDM, aggregates ratings which describe an alternative’s concordance with a criterion and criteria weights which denote the relative importance of the criterion and aggegates the scores over all selected criteria to rank and prioritize alternatives. Uncertainty is an integral component of such analysis and therefore some studies have attempted to use fuzzy set theory to capture differences among decision-makers with regards to different criteria and ratings of alternatives.

Note that MCDM is an unsupervised approach where in each alternative is ranked (so the number of initial clusters equals the number of alternatives. Once ranked, the grouping of these alternatives can be carried out subjectively or using unsupervised classification methods such as clustering and self-organizing maps (SOM).

While vulnerability captures the likely impact (or lack thereof) of floods at a given location. The hazard posed by the flood also varies geographically. This risk arises because of hydrologic conditions such as rainfall intensity and also land use land cover (LULC) conditions that lead to runoff (flood) generation. Risk of flooding of a land parcel depends upon several factors including but not limited to rainfall intensity, duration, LULC, soil types, antecedent moisture conditions and topographic slopes. Supervised machine learning models are used to develop relationships between flooded areas and other surrogate measures to model flooding hazard. A variety of approaches have been used to obtain flooded areas including but not limited to, use of satellite-imagery, household surveys, topography based wetness indices, and subjective or anecdotal information of decision makers. Clearly, the more direct the measurement, the more reliable is the result. A suite of machine learning modeling including but not limited to ANN, SVM, CART, MARS, Random Forest, Boosting Methods (GBT, XGBoost, AdaBoost) and deep learning have been employed for this purposes and demonstrated to model flood hazards with a high degree of accuracy.

The data volume available for modeling is often limited, which in turn favors conventional ML methods over deep learning paradigms. Some researchers have also utilized ensemble and stacking of algorithms with varying degree of success. The suitability of ensemble methods are hampered by the large predictive variability across different models. While most of the explanations of the ML modeling results is provided using tree-based approaches, the Shapely Additive Explanatins (SHAP) has also been used with deep learning models. While most models have focused on binary (Flood/No Flood) classification, multinomial models to capture varying levels of hazard have been explored to a limited extent.

Copula based approaches are widely used to estimate joint and conditional risks of flood intensity, volume and duration [

184,

185]. However, the integration of these approaches with machine learning is another poorly explored area of research. The coupling of ML and copula approaches to study droughts is demonstrated in [

186], indicating the possibility of such an effort for flooding as well. Unlike droughts which depend upon atmospheric variables (rainfall and temperature), estimation of flood duration, volume and intensity is only possible in gaged catchments and the flood indicators also depend on soil type, antecedent moisture, land use and other factors whose temporal variability is not known in many locations.

Flood hazard assessment in many areas is hampered by paucity of data. This is particularly true not only in developing countries but also in rural and peri-urban areas of developed nations. Transfer learning provides one way to overcome this limitation where a model trained over a larger dataset in a similar region is used to make predictions in another. In addition, several other emerging technologies provide useful information to understand flooding hazards and vulnerability. The Internet of Things (IoT) is bringing about new, low-cost technologies for monitoring both fluvial and pluvial floods [

187,

188,

189]. Low-cost sensors have the potential to significantly increase that data that are available for flood mapping. While such sensors also increase the data availability, they generally have poorer data quality and prone to giving erratic results. Therefore, data cleaning becomes necessary and machine learning algorithms for detecting and removing outliers can be useful [

190]. In addition, several machine learning models both conventional and deep, can be used to make real-time forecasting and enhance the early flood warning capabilities of downstream communities. While the integration of IoT and machine learning or early warning systems has been demonstrated in some areas [

191], there is still considerable opportunity to explore this area particularly in terms of data retrieval (using drones) when internet infrastructure may become non-functional due to floods.

7. Summary and Conclusions

Flooding is a complex problem that causes widespread damage across the world. It is now clear that flooding hazards cannot be completely eliminated using engineering measures alone. People have to live with floods. Flood control measures must not only focus on in-stream controls but also utilize structural and non-structural alternatives within an urban area to mitigate pluvial flooding to protect humans and also help mitigate downstream fluvial impacts. Despite keeping humans away from flood waters and managing them as necessary, the threats of flooding continue to grow unabated due to changes in climate, population growth and concomitant urbanization. Therefore, the current thinking goes a step further and evaluates how humans and the environment of a region are at risk of flooding and what are the best strategies to absorb the shocks of flooding and rebound to a better (or at least to the pre-flooding) state. The idea of withstanding the harmful effects of flooding to the best possible extent (robustness) and rebounding back to a better state as quickly as possible (rapidity) is called resiliency based flood management.

Resiliency-based flood management is not independent of flood control measures for minimizing fluvial and pluvial flooding, rather it takes a more holistic point of view to identify the risks that exist within a region and use it to guide future growth that is flood informed and also identify vulnerable targets that need immediate attention to bring the system back to normalcy. Thus, resiliency is not simply an engineering or land-planning and zoning endeavor but involves every one in the community to contribute towards flood-proofing.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in general and machine learning (ML) in particular can assist with resiliency based flood mitigation efforts. Machine learning models are universal approximators capable of capturing highly nonlinear phenomenon like floods. They overcome many deficiencies of physics-based models and are capable of providing better results with more easily available data in many cases. Machine learning is not a single technique but encompasses a wide range of algorithms that can be combined in more than one way to create solutions that are many times better than any individual algorithm that it is based on. These algorithms, especially newer deep learning based methods are quickly being adopted for flood studies. While discipline-specific of machine learning models have been reviewed in many articles on a regular pace, a holistic evaluation of machine learning in the context of flood studies is missing and a prime focus of this study.

The review not only restricts to evaluating machine learning models, but providing a context of flood management from command and control approaches to stakeholder-driven resiliency-risk based methods. The review also provides an overview of physics-based models that continue to be used today. These models often provide critical information such as inundation depth and extent that can be abstracted using machine learning schemes.

A review of literature indicates that many articles focus on a few ML techniques and identify a best predictor or classifier among them. As ML approaches are generally not taught in traditional hydrology classes, a review of various algorithms are presented to help understand their broad functioning. More in-depth reviews of the use of Machine learning for reservoir inflow and reservoir outflow and reservoir abstraction rules are presented. The LSTM model is widely used in both cases, but conventional methods are also in use. Levees and floodwalls are used to protect floodplains from inundation. Cracks in levees, piping and liquefaction are major causes of levee failure along with overtopping and compaction. CNN models and other object detection methods are being used to identify these zones of failures. Pump stations are operated to control flood waters from leaving riparian areas. Machine learning models are being explored to optimize the operation of these pump stations, the relatively small number of studies in this area directly corresponds to lack of suitable datasets.

A wide variety of machine learning models are being used to identify (unmapped) flooded areas based on a few known points (high water marks). In a similar vein, the results of the physics-based models are being abstracted by machine learning models to quickly compute flooding depths and the extent of inundation. Deep neural networks have shown considerable promise in this area. Machine learning models are also used to explain water quality transformations in a flood detention basins. Reinforcement learning in particular has been useful to control the releases from flood detention basins based on both quality and volume constraints. Flood resiliency planning studies often combine multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) modeling approaches to quantify vulnerability. Vulnerability is inversely related to resiliency and is a combination of disaster enhancing and disaster diminishing factors. In addition to MCDM, unsupervised learning approaches such as clustering have also been utilized. The flood hazard denotes the impact of the flood. Supervised learning methods are used to model flooding hazards. While many ML algorithms have been used, traditional approaches like SVM are seen to be better. The use of deep learning methods is constrained by the lack of availability of large volumes of data. In a similar vein, ensemble methods have also had limited success because of extreme variability in predictions.

The review also identified several unexplored or poorly explored directions in flood resiliency studies. In particular, capturing large-scale uncertainty in reservoir inflow predictions due to climate change is one such area. The use of ML for assessing risks to levees and floodwalls by integrating drone-based survey with computer vision and machine learning is another area. Similarly, the paucity of models for modeling pump station operations is limited by lack of suitable datasets. The development of such a dataset and providing in the public-domain will improve the number of applications in this area. In a similar vein, identification of pluvial flooding locations often relies on the use of physics-based model for quantifying the extent and nature of inundation. Therefore, the accuracy of ML models using this data cannot be higher than the physical-models they are based on. Remote-sensing methods particularly using Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) can be valuable along with improved field data collection to better capture inundation risks.

The use of deep learning and ensemble based methods for flood hazard identification has also seen limited success in flood risk assessment studies, especially for capturing fluvial flood risks. This limitation largely occurs due to paucity of data. Deep learning algorithms require considerable amounts of data and when such data are available (e.g., reservoir outflow in a stream) their predictive superiority becomes evident. Coupling of ML models with other statistical risk assessment methods such as copula theory has also been hindered by the lack of suitable data and presents another avenue to explore to move flood risk from a largely binary (flood/no flood) univariate calculation to its assessment over multiple dimensions.

In closing, machine learning models are widely being used in flood studies ranging from flood control to resiliency-based management. The usage is higher in those applications where data are readily available. Advances in remote-sensing, drone based data collection and proliferation of low-cost sensors using the Internet-of-Things (IoT) will further expand its role in many other aspects of floods that are currently hampered by data limitations. While machine learning offers great prediction and forecasting abilities, there is no single universally acceptable method, so empirical experimentation with multiple models becomes necessary. This aspect should not be viewed as a weakness but exploited to learn more about the functioning of the models and what is making them better predictors (or not). Explainable AI (XAI) methods come in handy in this regard and should be adopted to transition ML models for black-box forecasters to better informed and knowledge-based predictors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.U. and EA.H.; methodology, EA.H., V.U.; formal analysis, VU,EAH; investigation, EAH,VU; resources, VU,EAH.; data curation, EA.H; writing—original draft preparation, V.U.; writing—review and editing, EA.H.; visualization, EA.H.,V.U.; supervision, EA.H.; project administration, V.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kreibich, H.; Dimitrova, B. Assessment of damages caused by different flood types. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2010, 133, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- USDHS2025. United States Department of Homeland Security - Natural Disasters, 2025.

- Ruan, X.; Sun, H.; Shou, W.; Wang, J. The impact of climate change and urbanization on compound flood risks in coastal areas: a comprehensive review of methods. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H. Climate change impact on flood and extreme precipitation increases with water availability. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghafian, B.; Farazjoo, H.; Bozorgy, B.; Yazdandoost, F. Flood intensification due to changes in land use. Water resources management 2008, 22, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranzoni, A.; D’Oria, M.; Rizzo, C. Probabilistic mapping of life loss due to dam-break flooding. Natural Hazards 2024, 120, 2433–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, C.; Reyes-Silva, J.; Sañudo, E.; Cea, L.; Puertas, J. Urban pluvial flood modelling in the absence of sewer drainage network data: A physics-based approach. Journal of Hydrology 2024, 634, 131043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, K.; Mazzoleni, M.; Breinl, K.; Di Baldassarre, G. A systematic comparison of statistical and hydrological methods for design flood estimation. Hydrology Research 2019, 50, 1665–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Mu, R.; Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, H. Flood risk analysis of reservoirs based on full-series ARIMA model under climate change. Journal of Hydrology 2022, 610, 127979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Mustafa, F. Copula-based multivariate flood probability construction: a review. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2020, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.; Lee, M.; Azman, A.; Rose, L.; Teknousahawan, F. Development of Short-term Flood Forecast Using ARIMA. International Journal of Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2021, 15, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.A.; Ozelim, L.C.; Bacelar, L.; Ribeiro, D.B.; Stephany, S.; Santos, L.B. ML4FF: A machine-learning framework for flash flood forecasting applied to a Brazilian watershed. Journal of Hydrology 2025, 652, 132674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inc., A. Google Scholar, 2025.

- Ghorpade, P.; Gadge, A.; Lende, A.; Chordiya, H.; Gosavi, G.; Mishra, A.; Hooli, B.; Ingle, Y.; Shaikh, N. Flood forecasting using machine learning: a review. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th international conference on smart computing and communications (ICSCC. IEEE, 2021, pp. 32–36. [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, A.; Ozturk, P.; Chau, K. Flood prediction using machine learning models: Literature review. Water 2018, 10, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Research 2015, 24, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; Berge, E. How to do a Systematic Review. Internationl Journal of Stroke 2018, 13, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundzewicz, Z.; Su, B.; Wang, Y.; Xia, J.; Huang, J.; Jiang, T. Flood risk and its reduction in China. Advances in Water Resources 2019, 130, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.; Adamowicz, W.; Easter, K.; Graham-Tomasi, T. Ex post analysis of flood control: Benefit-cost analysis and the value of information. Water Resources Research 1988, 24, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ledesma, I.; Madrigal, J.; Domínguez-Sánchez, C.; Sánchez-Quispe, S.; Lara-Ledesma, B. Importance of cost-benefit evaluation in the selection of flood control infrastructures. Urban Water Journal 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.; Binh, D.; Tran, T.; Kantoush, S.; Sumi, T. Response of streamflow and sediment variability to cascade dam development and climate change in the Sai Gon Dong Nai River basin. Climate Dynamics 2024, 62, 7997–8017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckart, K.; McPhee, Z.; Bolisetti, T. Performance and implementation of low impact development–A review. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 607, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lawluvy, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yap, P. Low impact development (LID) practices: A review on recent developments, challenges and prospects. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2021, 232, 344. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiri Khiavi, A.; Vafakhah, M.; Sadeghi, S.; Jun, C.; Bateni, S. Comparative effect of traditional and collaborative watershed management approaches on flood components. Journal of Flood Risk Management 2025, 18, 13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, N. Two Decades of Integrated Flood Management: Status, Barriers, and Strategies. Climate 2024, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thampapillai, D.; Musgrave, W. Flood damage mitigation: A review of structural and nonstructural measures and alternative decision frameworks. Water Resources Research 1985, 21, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]