1. Introduction

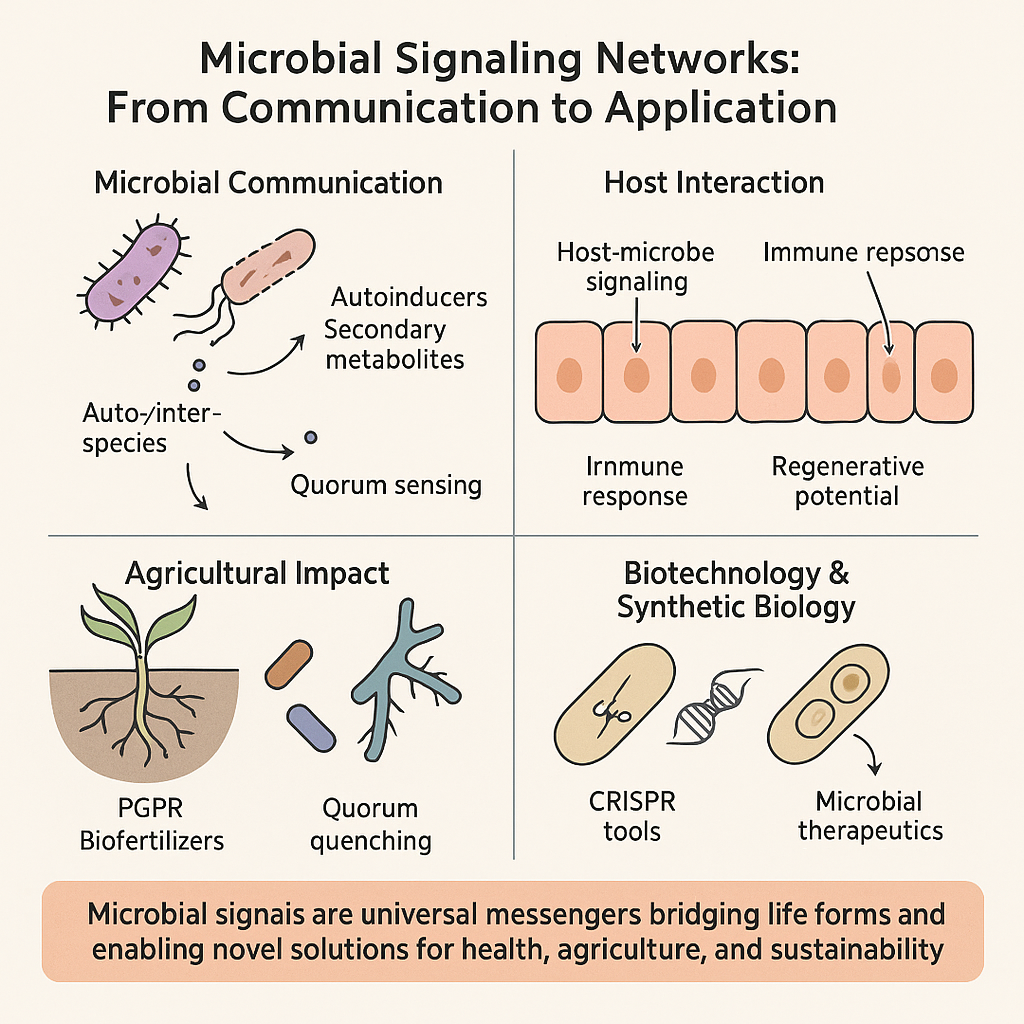

Microorganisms possess sophisticated systems for cell-to-cell communication, primarily through the production and detection of small signaling molecules that orchestrate population-wide behaviors (Yajima, 2016). One of the most studied communication mechanisms is quorum sensing, which allows microbial communities to coordinate physiological processes based on population density. Importantly, quorum sensing is not limited to microbial communities alone; recent research demonstrates that microorganisms can communicate with their hosts through these signaling networks (Abebe, 2021; Hughes & Sperandio, 2008). These communication systems rely on diverse chemical signals, including autoinducers (AIs) and secondary metabolites, which facilitate intra-species, inter-species, and even inter-kingdom interactions (Yajima, 2016). Autoinducers such as acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) in Gram-negative bacteria or oligopeptides in Gram-positive bacteria have been shown to mediate critical behaviors such as motility, virulence, biofilm formation, and antibiotic production (Balan et al., 2021; Camilli & Bassler, 2006; Huang et al., 2022).

Microbial communication with eukaryotic hosts is complex and can be either symbiotic or pathogenic (Groult et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). For instance, the human gut microbiota maintains a mutualistic relationship with its host, aiding in nutrient absorption and immune system development (Hughes & Sperandio, 2008). This beneficial interaction is largely mediated by chemical signals, hormones, peptides, and metabolites, that facilitate bidirectional communication between the host and microbial cells (Chamkhi et al., 2020; Combarnous & Nguyen, 2020; Rosset et al., 2021). These signaling mechanisms are central not only to microbial ecology but also to host development and health. By understanding how microbes use signaling molecules to influence cellular fate and behavior, researchers can harness these interactions to develop genetically engineered microorganisms capable of modulating host cells. This includes gene expression editing, protein production, suppression of harmful genes, and even inducing or inhibiting cellular differentiation (Chamkhi et al., 2020; Combarnous & Nguyen, 2020; Rosset et al., 2021). Cell signaling is essential for regulating critical cellular functions such as growth, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis (Patrad et al., 2022; Tyson et al., 2020). Disruptions in signaling pathways are implicated in many diseases, including cancer and autoimmune disorders (AlMusawi et al., 2021; Shin et al., 2021; Wolf, 2022). Thus, decoding microbial signaling provides not only fundamental insights into biology but also novel strategies for disease treatment and regenerative engineering.

This review highlights the mechanisms and significance of microbial signaling systems, especially quorum sensing, in shaping cellular environments and enabling host-microbe interactions. It also explores potential biotechnological applications such as bioengineering, microbial therapy, and agricultural enhancement, focusing on how signaling pathways can be manipulated to convert non-functional cells into functional ones.

2. Quorum Sensing and Autoinducers

2.1. Overview of Quorum Sensing

Quorum sensing is a density-dependent regulatory system that enables bacteria to communicate and coordinate group behaviors through the production and detection of extracellular signaling molecules known as autoinducers (Davares et al., 2022). As the population of bacteria increases, the concentration of these molecules rises, eventually triggering changes in gene expression once a threshold is surpassed (Duddy & Bassler, 2021). This system allows bacteria to synchronize behaviors that are inefficient or ineffective at the individual level but highly advantageous when performed collectively. These include biofilm formation, bioluminescence, sporulation, virulence factor production, and antibiotic synthesis (Jin et al., 2021). Quorum sensing operates through the synthesis, release, and detection of Autoinducers. Upon reaching a critical concentration, these molecules bind to specific receptors, initiating intracellular signaling cascades that alter gene transcription (Brindhadevi et al., 2020). Bacteria often live in heterogeneous populations, where quorum sensing also enables them to detect and respond to signals produced by other species or genera, thereby facilitating interspecies and interkingdom interactions (Zhou et al., 2020).

2.2. Diversity and Function of Autoinducers

Autoinducers are chemically diverse molecules whose production is tightly linked to cell population density. In Gram-negative bacteria, AHLs are the predominant signaling molecules, while Gram-positive bacteria utilize oligopeptides (Davies et al., 1998; Hu et al., 2022). A third type, autoinducer-2 (AI-2), is considered a universal signal employed in interspecies communication across both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The biological effects of Autoinducers vary depending on species and environmental context (

Table 1), but common functions include the regulation of virulence, motility, secondary metabolite production, and biofilm architecture (Wiesmann et al., 2022). The discovery that Vibrio fischeri produces light only when a certain population density is achieved led to the coining of the term “autoinduction” (Nealson et al., 1970). Quorum sensing not only governs microbial population dynamics but also influences host-microbe interactions. For example, some bacterial Autoinducers can modulate host immune responses or disrupt host cellular signaling, underlining the importance of quorum sensing in both symbiosis and pathogenesis (Pan et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020; Wu & Luo, 2021).

2.3. Evolutionary Perspectives on Cell-Cell Signaling

Recent studies suggest that microbial signaling mechanisms may have influenced the evolution of complex communication systems in higher organisms. Tang et al. (2022) proposed that many first-messenger biosynthetic pathways, such as those for dopamine, serotonin, and melatonin, share conserved genetic origins across bacteria and mammals. Horizontal gene transfer appears to have played a significant role, allowing bacterial enzymes to evolve functions related to mammalian signaling molecules (Hwang & Back, 2022). The 17 known enzymes involved in signal metabolism, 16 are present in both bacteria and vertebrates, indicating extensive genetic overlap (Tang et al., 2022). For example, both groups possess the enzyme hydroxy-indole O-methyltransferase, essential for melatonin synthesis. These findings support the notion that certain bacteria are naturally capable of producing signaling molecules traditionally associated with mammalian systems, reinforcing the hypothesis that inter-kingdom communication evolved from these shared molecular tools (Cui et al., 2020; Hughes & Sperandio, 2008). Together, these insights demonstrate that quorum sensing is not merely a microbial phenomenon but a deeply conserved communication strategy that underpins a broad array of biological interactions and evolutionary processes.

3. The Cellular Micro-environment and Host Modulation

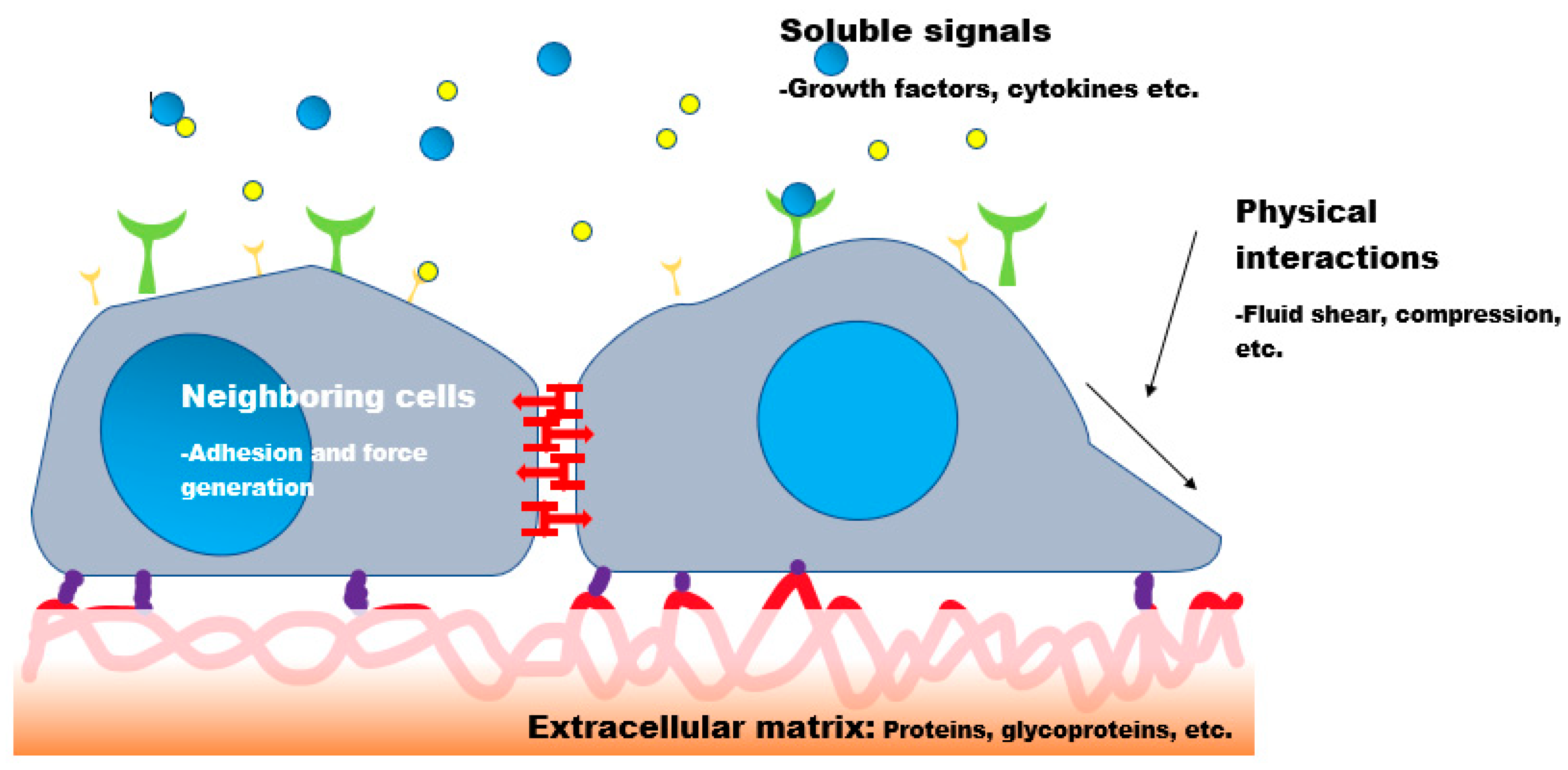

3.1. Definition and Components of the Micro-Environment

The cellular microenvironment encompasses the local conditions and components surrounding a cell, including the extracellular matrix (ECM), adjacent cells, and soluble or insoluble signaling molecules. These microenvironmental cues regulate essential cellular processes such as differentiation, proliferation, adhesion, and migration (Huang et al., 2021). The ECM, in particular, provides not only structural support but also mechanical and biochemical signals that influence cell behavior (Wan et al., 2021). Biochemical cues such as hormones, cytokines, and growth factors (GF) serve as primary regulators of cellular behavior. Likewise, biophysical stimuli, topographical features, stiffness, and molecular alignments of ECM proteins, are also critical in dictating cellular responses (Xiao et al., 2023). It is essential to recognize that cells sense their surroundings at the micron and nanometer scale through protein receptors, and hence, traditional bulk measurements may not capture the microenvironment experienced at the cellular level (Hellmund & Koksch, 2019; Im, 2020; Tanaka et al., 2020).

3.2. Receptor-Mediated Signal Recognition

Cells utilize two major classes of surface receptors to recognize and respond to environmental signals: those that bind soluble ligands (e.g., hormones and cytokines) and those that interact with insoluble ligands (e.g., ECM fragments or membrane-bound ligands from adjacent cells). These receptors include integrins and cadherins, which mediate cell adhesion and transduce biophysical signals (Gross et al., 2022). An illustrative example is transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), a key regulator of ECM synthesis, inflammation, and cell proliferation. TGF-β is initially secreted in an inactive form bound to the ECM, and its activation is tightly regulated by ECM-associated proteins like fibrillin and fibronectin (Huang et al., 2021; Keller & Peters, 2022). Following mechanical or enzymatic cues, active TGF-β is released and triggers downstream signaling cascades that regulate cellular behavior (Lu et al., 2011; Thomas et al., 2002).

3.3. Cell-Micro-environment Interactions

Cells actively contribute to shaping their microenvironment through secretion of soluble factors, ECM remodeling, and force generation (

Figure 1). Cytoskeletal components and motor proteins, driven by ATP hydrolysis, allow cells to dynamically reshape themselves and exert forces on their surrounding matrix (Lemmon et al., 2009). These forces facilitate local ECM assembly, influence fibril orientation, and affect matrix stiffness, ultimately altering how cells receive and respond to external cues (Legant et al., 2012). Mechanical signals can also be transmitted directly to neighboring cells through adherens junctions and other contact-dependent mechanisms (DeMali et al., 2014). This two-way exchange ensures coordination during essential processes such as tissue morphogenesis, wound healing, and immune responses.

3.4. Soluble Signaling Molecules and Autocrine/Paracrine Loops

Cells release various soluble molecules, cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and hormones, that diffuse through the extracellular space to influence nearby (paracrine signaling) or the same (autocrine signaling) cells (DuFort et al., 2011). These interactions regulate diverse cellular behaviors and are frequently utilized in bioengineering applications to optimize tissue culture systems or scaffold design (Elvevoll et al., 2022).

3.5. Role of Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

The ECM is a fibrous, dynamic scaffold composed of proteins, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans. It dictates tissue architecture and transmits mechanical signals to embedded cells. In tissues like cartilage and tendon, the ECM determines bulk mechanical properties and supports load-bearing functions (Xing et al., 2020). Moreover, it stores and regulates the release of signaling molecules that influence cell fate and function (Dalton & Lemmon, 2021; Miller et al., 2020; Virdi & Pethe, 2021). Despite extensive research, the full impact of ECM’s biochemical, mechanical, and structural properties on cellular responses is still under active investigation. However, its importance in both physiological and pathological contexts, including cancer, fibrosis, and wound healing, is well established.

4. Microbial Signaling in Agriculture

4.1. Plant-Microbe Interactions and Rhizosphere Communication

In the agricultural context, microbial signaling plays a central role in facilitating beneficial plant-microbe interactions, particularly in the rhizosphere, the region of soil influenced by plant roots. Rhizobacteria such as Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Streptomyces spp. utilize quorum sensing molecules to regulate colonization, biofilm formation, and secretion of secondary metabolites that enhance plant growth and suppress pathogens (Alori et al., 2017). These microbes communicate with plant roots via signaling compounds such as lipo-chitooligosaccharides (LCOs), N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which influence root architecture and immune responses (Gouda et al., 2018).

4.2. Role of Endophytes and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR)

Endophytic microorganisms, residing within plant tissues without causing harm, significantly contribute to plant fitness by producing plant growth regulators (PGRs) like auxins, gibberellins, and cytokinins (

Table 2). These microbes communicate via signaling molecules that modulate gene expression in host plants, resulting in improved nutrient acquisition and stress tolerance (Lugtenberg et al., 2016). Similarly, PGPRs secrete peptides, siderophores, and small RNAs that mediate interactions with the host and regulate functions such as nitrogen fixation and phosphate solubilization (Bhattacharyya & Jha, 2012).

4.3. Quorum Sensing in Biocontrol and Biofertilizer Development

Quorum sensing molecules also regulate the synthesis of antimicrobial compounds, exopolysaccharides (EPS), and lytic enzymes that are crucial for biocontrol mechanisms. For example, the fungus Trichoderma harzianum utilizes quorum sensing-regulated pathways to produce enzymes that degrade the cell walls of phytopathogens (Contreras-Cornejo et al., 2016). Moreover, certain bacteria employ quorum quenching mechanisms to disrupt the communication of pathogenic microbes, thereby providing indirect protection to plants (Sulochana et al., 2021). Genetic and metabolic engineering approaches are now being applied to enhance the signaling capacity of beneficial microbes used in biofertilizers and biopesticides. Engineered strains are being developed to secrete higher levels of specific signaling molecules that promote plant health and yield under diverse environmental conditions (Bhardwaj et al., 2014).

4.4. Inter-Kingdom Signaling Between Plants and Microbes

Plants are also capable of perceiving microbial signals and responding through the release of signaling molecules such as flavonoids, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid (

Table 3). These molecules help recruit beneficial microbes while activating defense mechanisms against pathogens (Venturi & Keel, 2016). This bidirectional signaling forms the basis of complex symbiotic relationships, such as those seen in legume-rhizobia and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associations (Smith & Smith, 2011). In summary, microbial communication in agriculture enhances nutrient acquisition, disease resistance, and overall crop productivity. Harnessing and manipulating these signaling pathways holds great promise for the development of sustainable and eco-friendly agricultural practices.

5. Synthetic and Genetic Engineering Applications

5.1. Engineered Microbial Products for Agriculture and Medicine

The expanding field of microbial biotechnology has enabled the development of genetically modified microorganisms with enhanced traits for both agricultural and therapeutic applications (

Table 4). These engineered strains are capable of producing biofertilizers, bio-fungicides, and biopesticides that are more effective and sustainable alternatives to chemical inputs (Brindhadevi et al., 2020). For instance, microbes can be modified to secrete higher levels of growth-promoting phytohormones, nitrogen-fixation enzymes, or pathogen-antagonistic compounds, thereby improving plant resilience and productivity under diverse environmental stresses. In the medical field, synthetic biology has facilitated the creation of probiotic strains designed to modulate host physiology. These include bacteria engineered to produce therapeutic peptides, deliver drugs, or interact with host immune cells via engineered signaling pathways (Brindhadevi et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2023).

5.2. Signal Interference and Quorum Sensing Inhibition

One promising strategy in microbial engineering is quorum sensing interference, also known as quorum quenching. This involves disrupting microbial communication by degrading or inhibiting the production and detection of autoinducers (Pan et al., 2023). Quorum sensing inhibitors can be small molecules, enzymes, or structural analogs that block signal-receptor binding or degrade AHLs and peptides, thus preventing the expression of virulence genes and biofilm formation (Wang et al., 2020). Quorum quenching has proven effective in reducing infections caused by pathogenic bacteria and mitigating biofilm-associated problems in medical and industrial contexts. Additionally, engineered microbes capable of producing quorum sensing, which can be deployed as biocontrol agents in agriculture to protect crops from microbial pathogens (Wu & Luo, 2021).

5.3. CRISPR and Synthetic Biology for Signal Modulation

The use of CRISPR-Cas systems and other genome editing tools has revolutionized microbial synthetic biology. These technologies allow for precise editing of microbial genomes to optimize signal production, modify metabolic pathways, and insert novel biosynthetic circuits (Cui et al., 2020). For example, bacteria can be engineered to detect specific environmental or physiological signals and respond by producing targeted therapeutic or agricultural compounds. Synthetic circuits can also be designed to mimic natural signaling cascades, enabling microbes to perform complex tasks such as environmental sensing, biosensing, and targeted gene regulation. These approaches enhance the ability of engineered microorganisms to communicate with host cells, modulate their behavior, or convert non-functional cells into functional ones under defined conditions (Tang et al., 2022). Together, these synthetic and genetic engineering strategies highlight the growing potential of manipulating microbial signaling for diverse applications, offering precise and programmable solutions for human health, agriculture, and environmental sustainability.

6. Inter-Kingdom Communication

6.1. Microbial Response to Host Hormones

One of the most intriguing aspects of microbial signaling is the ability of bacteria to perceive and respond to host-derived molecules, particularly hormones. Host hormones such as epinephrine and norepinephrine can influence bacterial behavior through sensor systems like QseC/QseB, which detect these signals and modulate gene expression accordingly (Pan et al., 2023). This cross-kingdom communication plays a critical role in bacterial colonization, virulence, and biofilm formation, especially in host environments such as the gut. Studies have shown that Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica can alter their motility, iron acquisition, and toxin production in response to host hormonal cues. These adaptive behaviors demonstrate the profound influence of host signals on microbial physiology (Wang et al., 2020).

6.2. Host Immune Sensing and Microbial Adaptation

Microorganisms are not passive participants in host environments. They actively sense immune system activity and adjust their gene expression to either evade detection or modulate host responses (Wu & Luo, 2021). For instance, certain pathogens can downregulate surface antigens to avoid immune recognition or upregulate stress response genes to withstand antimicrobial peptides and oxidative bursts. This dynamic interaction often determines the outcome of infection, whether a pathogen establishes disease or is cleared by host defenses. Understanding these molecular dialogues can inform the design of new antimicrobial strategies that target bacterial communication rather than growth, thereby reducing selective pressure for resistance (Cui et al., 2020).

6.3. Stress-Induced Microbial Virulence

Psychological and physiological stress in hosts has been shown to exacerbate microbial virulence. Stress hormones can disrupt gut microbiota composition and compromise barrier function, creating conditions favorable for pathogenic invasion. Through quorum sensing and other signaling pathways, bacteria can detect changes in the host environment and upregulate virulence genes accordingly (Pan et al., 2023). This stress-induced modulation of microbial behavior is particularly relevant in chronic diseases, post-operative infections, and immune-compromised individuals. Targeting the signaling interfaces between microbes and host stress pathways may offer novel therapeutic interventions that bolster host resilience and mitigate pathogen aggression. In summary, inter-kingdom communication between microbes and their hosts is a finely tuned process with significant implications for health and disease. By decoding these signaling networks, scientists can develop tools to modulate microbial behavior, improve host outcomes, and advance precision microbiome-based therapies.

7. Conclusions

Microbial communication via signaling molecules such as autoinducers, peptides, and secondary metabolites plays a fundamental role in regulating microbial behavior and shaping host-microbe interactions. These signaling mechanisms, particularly quorum sensing, coordinate a wide range of microbial activities including biofilm formation, virulence regulation, and mutualistic symbiosis with host organisms. Through finely tuned communication systems, microbes can influence host immune responses, cellular microenvironments, and even inter-kingdom molecular interactions. In agriculture, these microbial signals are critical for promoting plant growth, enhancing stress tolerance, and defending against pathogens through the activity of beneficial endophytes, PGPR, and engineered biocontrol agents. Similarly, in biotechnology and medicine, microbial signaling pathways have been harnessed to create genetically engineered microbes capable of therapeutic delivery, metabolic modulation, and quorum sensing interference. Advanced tools such as CRISPR and synthetic biology now enable researchers to design microbial strains with enhanced communication capabilities, offering targeted solutions for improving health, productivity, and environmental sustainability. Furthermore, the evolutionary conservation of signaling mechanisms across domains suggests potential for expanding our understanding of cellular communication beyond microbial systems. Future research should focus on unraveling the complexities of microbial signaling in natural and engineered environments, including its role in disease, immunity, and regenerative processes. By manipulating microbial communication systems, we can develop innovative strategies for transforming non-functional or damaged cells into functional units, opening new frontiers in therapeutic and agricultural applications. Understanding and leveraging microbial signaling is not only a cornerstone of microbiology but also a key to advancing next-generation solutions in health, agriculture, and environmental biotechnology.

Authors Contributions

A.A.M. comprehended and planned the study, carried out the analysis, wrote the manuscript; and prepared the graphs and illustrations; S.K. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript and wrote the manuscript; A.A.M. supervised the whole work, and all authors approved the final manuscript

Code availability

There was no code available.

Funding

There was no fund available.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article does not include any studies by any of the authors that used human or animal participants. All authors are conscious and accept responsibility for the manuscript. No part of the manuscript content has been published or accepted for publication elsewhere.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author Abdullah Al Mamun is responsible for all data and materials.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the department of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering for supporting this research

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abebe, G.M. Oral biofilm and its impact on oral health, psychological and social interaction. Int. J. Oral Dent. Health 2021, 7, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- AlMusawi, S.; Ahmed, M.; Nateri, A.S. Understanding cell-cell communication and signaling in the colorectal cancer microenvironment. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan, B.; Dhaulaniya, A.S.; Varma, D.A.; Sodhi, K.K.; Kumar, M.; Tiwari, M.; Singh, D.K. Microbial biofilm ecology, in silico study of quorum sensing receptor-ligand interactions and biofilm mediated bioremediation. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 203, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brindhadevi, K.; LewisOscar, F.; Mylonakis, E.; Shanmugam, S.; Verma, T.N.; Pugazhendhi, A. Biofilm and Quorum sensing mediated pathogenicity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Process. Biochem. 2020, 96, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilli, A.; Bassler, B.L. Bacterial Small-Molecule Signaling Pathways. Science 2006, 311, 1113–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamkhi, I.; El Omari, N.; Benali, T.; Bouyahya, A. Quorum sensing and plant-bacteria interaction: role of quorum sensing in the rhizobacterial community colonization in the rhizosphere. In Quorum Sensing: Microbial Rules of Life; ACS Publications: 2020; pp. 139–153.

- Combarnous, Y.; Nguyen, T.M.D. Cell communications among microorganisms, plants, and animals: origin, evolution, and interplays. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, H.S. Molecularly Imprinted Polymers and Surface Imprinted Polymers Based Electrochemical Biosensor for Infectious Diseases. Sensors 2020, 20, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, C.J.; Lemmon, C.A. Fibronectin: Molecular Structure, Fibrillar Structure and Mechanochemical Signaling. Cells 2021, 10, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davares, A.K.L.; Arsene, M.M.J.; Viktorovna, P.I.; Vyacheslavovna, Y.N.; Vladimirovna, Z.A.; Aleksandrovna, V.E.; Nikolayevich, S.A.; Nadezhda, S.; Anatolievna, G.O.; Nikolaevna, S.I.; et al. Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors from Probiotics as a Strategy to Combat Bacterial Cell-to-Cell Communication Involved in Food Spoilage and Food Safety. Fermentation 2022, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.G.; Parsek, M.R.; Pearson, J.P.; Iglewski, B.H.; Costerton, J.W.; Greenberg, E.P. The Involvement of Cell-to-Cell Signals in the Development of a Bacterial Biofilm. Science 1998, 280, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMali, K.A.; Sun, X.; Bui, G.A. Force Transmission at Cell–Cell and Cell–Matrix Adhesions. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 7706–7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duddy, O.P.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum sensing across bacterial and viral domains. PLOS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufort, C.C.; Paszek, M.J.; Weaver, V.M. Balancing forces: Architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvevoll, E.O.; James, D.; Toppe, J.; Gamarro, E.G.; Jensen, I.-J. Food Safety Risks Posed by Heavy Metals and Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) related to Consumption of Sea Cucumbers. Foods 2022, 11, 3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.M.; Dane, M.A.; Smith, R.L.; Devlin, K.L.; McLean, I.C.; Derrick, D.S.; Mills, C.E.; Subramanian, K.; London, A.B.; Torre, D.; et al. A multi-omic analysis of MCF10A cells provides a resource for integrative assessment of ligand-mediated molecular and phenotypic responses. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groult, B.; Bredin, P.; Lazar, C.S. Ecological processes differ in community assembly of Archaea, Bacteria and Eukaryotes in a biogeographical survey of groundwater habitats in the Quebec region (Canada). Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 5898–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmund, K.S.; Koksch, B. Self-Assembling Peptides as Extracellular Matrix Mimics to Influence Stem Cell's Fate. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Liu, Y.; Luo, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, T. Stable and rapid partial nitrification achieved by boron stimulating autoinducer-2 mediated quorum sensing at room & low temperature. Chemosphere 2022, 304, 135327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wan, D.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, S.; Lin, S.; Qiao, Y. Extracellular matrix and its therapeutic potential for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Ma, L.; Li, H.; Liu, R.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y. Insights into Adaptive Mechanisms of Extreme Acidophiles Based on Quorum Sensing/Quenching-Related Proteins. mSystems 2022, 7, e0149121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.T.; Sperandio, V. Inter-kingdom signalling: communication between bacteria and their hosts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, O.-J. , & Back, K. (2022). Functional Characterization of Arylalkylamine N-Acetyltransferase, a Pivotal Gene in Antioxidant Melatonin Biosynthesis from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Antioxidants, 11(8), 1531.

- Im, G.-I. Biomaterials in orthopaedics: the past and future with immune modulation. Biomater. Res. 2020, 24, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T.; Patel, S.J.; Van Lehn, R.C. Molecular simulations of lipid membrane partitioning and translocation by bacterial quorum sensing modulators. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0246187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.E.; Peters, D.M. Pathogenesis of glaucoma: Extracellular matrix dysfunction in the trabecular meshwork-A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 50, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F. (2022). Identification and Characterization of Arabidopsis Toxicos en Levadura 12: A Gene Involved in Chitin-Elicitor-Triggered Immunity and Salt Tolerance. The University of Alabama.

- Legant, W.R.; Chen, C.S.; Vogel, V. Force-induced fibronectin assembly and matrix remodeling in a 3D microtissue model of tissue morphogenesis. Integr. Biol. 2012, 4, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, C.A.; Chen, C.S.; Romer, L.H. Cell Traction Forces Direct Fibronectin Matrix Assembly. Biophys. J. 2009, 96, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Takai, K.; Weaver, V.M.; Werb, Z. Extracellular Matrix Degradation and Remodeling in Development and Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a005058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. E. , Hu, P., & Barker, T. H. (2020). Feeling things out: bidirectional signaling of the cell–ECM interface, implications in the mechanobiology of cell spreading, migration, proliferation, and differentiation. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 9(8), 1901445.

- Nealson, K.H.; Platt, T.; Hastings, J.W. Cellular Control of the Synthesis and Activity of the Bacterial Luminescent System. J. Bacteriol. 1970, 104, 313–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhou, J.; Tang, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S. Bacterial Communication Coordinated Behaviors of Whole Communities to Cope with Environmental Changes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 4253–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, D.; Mandal, S. Non-rhizobia are the alternative sustainable solution for growth and development of the nonlegume plants. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2022, 39, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrad, E.; Khalighfard, S.; Amiriani, T.; Khori, V.; Alizadeh, A.M. Molecular mechanisms underlying the action of carcinogens in gastric cancer with a glimpse into targeted therapy. Cell. Oncol. 2022, 45, 1073–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosset, S.L.; Oakley, C.A.; Ferrier-Pagès, C.; Suggett, D.J.; Weis, V.M.; Davy, S.K. The Molecular Language of the Cnidarian–Dinoflagellate Symbiosis. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Chane, A.; Jung, M.; Lee, Y. Recent Advances in Understanding the Roles of Pectin as an Active Participant in Plant Signaling Networks. Plants 2021, 10, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Nakahata, M.; Linke, P.; Kaufmann, S. Stimuli-responsive hydrogels as a model of the dynamic cellular microenvironment. Polym. J. 2020, 52, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Liao, S.; Qu, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, S.; Cai, Z.; Fan, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, S.; Li, L. Evaluating Bacterial Pathogenesis Using a Model of Human Airway Organoids Infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0240822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Upadhyay, A.; Liao, C.; Merkler, D.J.; Han, Q. Evolutionary genomics analysis reveals gene expansion and functional diversity of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferases in the Culicinae subfamily of mosquitoes. Insect Sci. 2022, 30, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.J.; Hart, I.R.; Speight, P.M.; Marshall, J.F. Binding of TGF-β1 latency-associated peptide (LAP) to αvβ6 integrin modulates behaviour of squamous carcinoma cells. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 87, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, J.; Bundy, K.; Roach, C.; Douglas, H.; Ventura, V.; Segars, M.F.; Schwartz, O.; Simpson, C.L. Mechanisms of the Osteogenic Switch of Smooth Muscle Cells in Vascular Calcification: WNT Signaling, BMPs, Mechanotransduction, and EndMT. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdi, J.K.; Pethe, P. Biomaterials Regulate Mechanosensors YAP/TAZ in Stem Cell Growth and Differentiation. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 18, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, L. Manipulation of Stem Cells Fates: The Master and Multifaceted Roles of Biophysical Cues of Biomaterials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Payne, G.F.; Bentley, W.E. Quorum Sensing Communication: Molecularly Connecting Cells, Their Neighbors, and Even Devices. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2020, 11, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, C.; Ma, K.; Kong, M.; Jiang, N.; Pan, J. Microbial diversity of archaeological ruins of Liangzhu City and its correlation with environmental factors. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2022, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Grenier, D.; Yi, L. Regulatory Mechanisms of the LuxS/AI-2 System and Bacterial Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.-H.; Qi, S.-S.; Dai, Z.-C.; Du, D.-L. Effect of nitrogen-fixing bacteria on resource investment of the root system in an invasive clonal plant under low nutritional environment. Flora 2022, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmann, C.L.; Wang, N.R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Haney, C.H. Origins of symbiosis: shared mechanisms underlying microbial pathogenesis, commensalism and mutualism of plants and animals. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S. Cell Wall Signaling in Plant Development and Defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 323–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.P.; Ramachandra, S.S. Quorum Sensing and Quorum Quenching with a Focus on Cariogenic and Periodontopathic Oral Biofilms. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Luo, Y. Bacterial Quorum-Sensing Systems and Their Role in Intestinal Bacteria-Host Crosstalk. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Sun, Y.; Liao, L.; Su, X. Response of mesenchymal stem cells to surface topography of scaffolds and the underlying mechanisms. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 2550–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Lee, H.; Luo, L.; Kyriakides, T.R. Extracellular matrix-derived biomaterials in engineering cell function. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 42, 107421–107421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, A. Recent advances in the chemistry and chemical biology of quorum-sensing pheromones and microbial hormones. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry 2016, 47, 331–355. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zhu, X.; Pan, J. Regulatory Mechanisms and Promising Applications of Quorum Sensing-Inhibiting Agents in Control of Bacterial Biofilm Formation. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 589640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).