Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results

| (1) Begin Thyroid Disease (1012) | IPTMC ** Incidence | |

| 1. Nodular Goiter | 770 (76.1%) | 67 (8.7%) |

| 2. Hashimoto Thyroiditis (HT) | 101 (10%) | 21 (20.8%) |

| 3. Grave’s | 62 (6.1%) | 11 (17.74%) |

| 4. Adenoma | 79 (7.8%) | 10 (12.7%) |

| Total | 1012 (100%) | 109 (10.8%) *** |

| (2) Thyroid Malignancies (436) | ||

| (1) Papillary (PTC)* | Number 378 (86.7%) | |

| T1 : T1a : < 1 cm ( PTMC)** | 137 (36.2%) | |

| Incidental *** | 109 | |

| Non-Incidental *** | 28 | |

| T1b : > 1 - < 2 cm | 77 (20.4%) | |

| T 2 : > 2 cm - < 4 cm | 110 (29.1%) | |

| T 3 : > 4 cm | 54 (14.3%) | |

| Total | 378 (100%) | |

| (2) Other Malignancies | Number 58 (13.3%) | |

| Follicular Carcinoma | 23 | |

| Hurthle Cell Carcinoma | 8 | |

| Medullary Carcinoma | 12 | |

| Lymphoma | 4 | |

| Anaplastic Carcinoma | 2 | |

| Well Differentiated Tumour of | 8 | |

| Undetermined Malignant potential | ||

| Renal mets | 1 | |

| Total | 58 | |

| All Malignancies | 436 (100%) | |

| Clinical Presentation | Subtype of PTMC | |||||

| 1. Incidental PTMC (IPTMC) associated with | Classic subtype | Infiltrative follicular subtype | Invasive encapsulated FV PTC (all minimally invasive) | FVPTC non-encapsulated circumscribed (all minimally invasive) | Oncocytic subtype | Total Number |

| _ Multinodular Goiter | 38 (56.7%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (7.5%) | 23(34.3%) | 1(1.5%) | 67 (100%) |

| _ Hashimoto | 8 (38%) | 4 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (100%) |

| _ Graves’ | 6 (54.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (36.4%) | 1 (9.1%) | 11 (100%) |

| _ Adenoma | 5 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) | 3 (30%) | 1 (10%) | 10(100%) |

| 1. Total : IPTMC | 57 (52.8%) | 4 (3.7%) | 6 (3.7%) | 39 (35.8%) | 3 (2.8%) | 109 (100%) |

| 2. Non-incidental or Primary (NIPTMC) | 25 (89.3%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 28 (100%) |

| P Value | 0.002 | 0.4801 | 0.1515 | 0.001 | 0.3751 | 0.0001 |

| < 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | < 0.5 | |

| Type | Incidental | Non- Incidental (Primary) | P value | Status p. v | ||

| Number | 109 (79.6) | 28(20.4%) | 0.045- | <0.05 | ||

| Gender | F | 85 (77.9%) | 20 (71.43%) | 0.324 | >0.05 | |

| M | 24 (22.1%) | 8 (28.57%) | ||||

| Age , Y | 1) Average Y | 44.153 + 11.28y | 37.14 + 13.43y | 0.0001 | <0.05 | |

| 2) < 45 Y | 50 (45.9%) | 20(71.43%) | 6.93- | <0.05 | ||

| > 45 Y | 59 (54.1%) | 8(28.57%) | ||||

| < 55 Y | 86 (78.9%) | 27 (96.43%) | ||||

| > 55 Y | 23 (21.1%) | 1 (3.57%) | ||||

| Associated pathology | ||||||

| Multinodular Goiter | 67 (61.5%) | * | 0.0005 | <0.05 | ||

| Hashimoto Thyroiditis | 21(19.3%) | * | 0.0054 | <0.05 | ||

| Adenoma | 10 (9.2%) | * | 0.5513 | > 0.05 | ||

| Grave’s disease | 11(10%) | * | 0.1174 | > 0.05 | ||

| Nationality | ||||||

| Local | 60 (55%) | 16 (57.1%) | 0.35 | >0.05 | ||

| International | 49 (45%) | 12 (42.9%) | ||||

| *FNAC B VI or / and B V | ||||||

| Yes | 48 (44%) | 24(85.71%) | 0.001 | <0.05 | ||

| No | 61 (56%) | 4(14.29%) | ||||

| Aggressive Features | ||||||

| Extrathyroidal Extension | Yes | 8 (7.3%) | 6(21.43%) | 0.0015 | <0.05 | |

| No | 101 (92.6%) | 22(78.57%) | ||||

| Positive Central nodes | Yes | 3 (2.8%) | 6 (21.41%) | 0.0291 | <0.05 | |

| No | 106 (97.2%) | 22 (75%) | ||||

| Positive Lateral Nodes | Yes | 0 ( 0%) | 8(28.6%) | 0.012 | <0.05 | |

| No | 109 (100%) | 20(71.4%) | ||||

| Lymphovascular invasion | Yes | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) | _ | >0.05 | |

| No | 109 (100%) | 27 (96.4%) | _ | |||

| Aggressive Features : Total | Yes | 11 (10.1%) | 21 (75%) | 0.004 | <0.05 | |

| No | 98 (89.9%) | 7 (25%) | ||||

| Total Thyroidectomy | 97(88.1%) | 28(100%) | 0.0303 | <0.05 | ||

| Total Lobectomy | 12(11.9%) | 0(0%) | ||||

| Type | Unifocal | Multifocal (MF) | P - Value |

| 1) Number | 100 (73%) | 37 (27%) | < 0.002 |

| 2) Average maximal tumoral diameter | 0.442 cm | 0.78 cm | 0.0054 |

| 3) Size > 5 mm | 43 (43%) | 29 (78.4%) | < 0.0002 |

| 4) Site Unilobar Right or Left | 97 ( 97%) | Bilobar 27 (73%) | > 0.1367 |

| isthmus | 3 ( 3%) | 0% | |

| 5) Gender | |||

| F | 76 (76%) | 27 (73%) | > 0.7248 |

| M | 24 (24%) | 10 (27%) | |

| 6) Age: | |||

| F | 43.46 + 11.49 | 45.55 + 13.45 | > 0.6323 |

| M | 42.95 + 12.18 | 43.3 + 17.13 | |

| 7) FNA BVI or / BV | 42 ( 42%) | 21 (56.8%) | > 0.1294 |

| 8) Predictors of MF : | |||

| IPTMC | 85 ( 85%) | 24 ( 64.8%) | 0.0915 |

| NIPTMC* | 15 ( 15%) | 13 ( 35.2%) | < 0.0098 |

| Nodular goiter | 52 ( 52%) | 15 ( 40.5%) | > 0.2319 |

| Hashimoto | 14 ( 14%) | 7 ( 18.9%) | > 0.4642 |

| Grave’s | 10 ( 10%) | 1 ( 2.7%) | > 0.1640 |

| Adenoma | 9 ( 9%) | 1 ( 2.7%) | > 0.2048 |

| 8) Aggressive features | |||

| - ETE | ** | ||

| Yes | 8 (8%) | 6 (16.21%) | > 0.2371 |

| NO | 92 (92%) | 31 (83.79%) | |

| Positive Central Nodes | |||

| Yes | 3 (3%) | 5 (13.5%) | > 0.0768 |

| No | 97 (97%) | 32 (86.5%) | |

| Positive Lateral Nodes | |||

| Yes | 3 (3%) | 6 (16.21%) | > 0.0591 |

| No | 97 (97%) | 31 (83.79%) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |||

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.7%) | > 0.5307 |

| No | 0 (0%) | 36 (97.3%) | |

| Aggressive Criteria : total | |||

| Yes | 14 (14%) | 18 (48.6%) | < 0.007 |

| No | 86 (86%) | 19 (51.4%) | |

| Total Thyroidectomy | |||

| Yes | 88 (88%) | 37 (100%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 12 (12%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Pathology | 2013-2017 | 2018-2023 |

| NIPTMC | 17 (60.7%) | 11 (30.3%) |

| IPTMC | 50 (45.9%) | 59 (54.6%) |

|

Multinodular Goiter TT TL |

23 7 |

36 1 |

|

Hashimoto’s TT TL |

6 2 |

12 1 |

|

Adenoma TT TL |

5 1 |

4 0 |

|

Thyrotoxicosis TT TL |

6 0 |

5 0 |

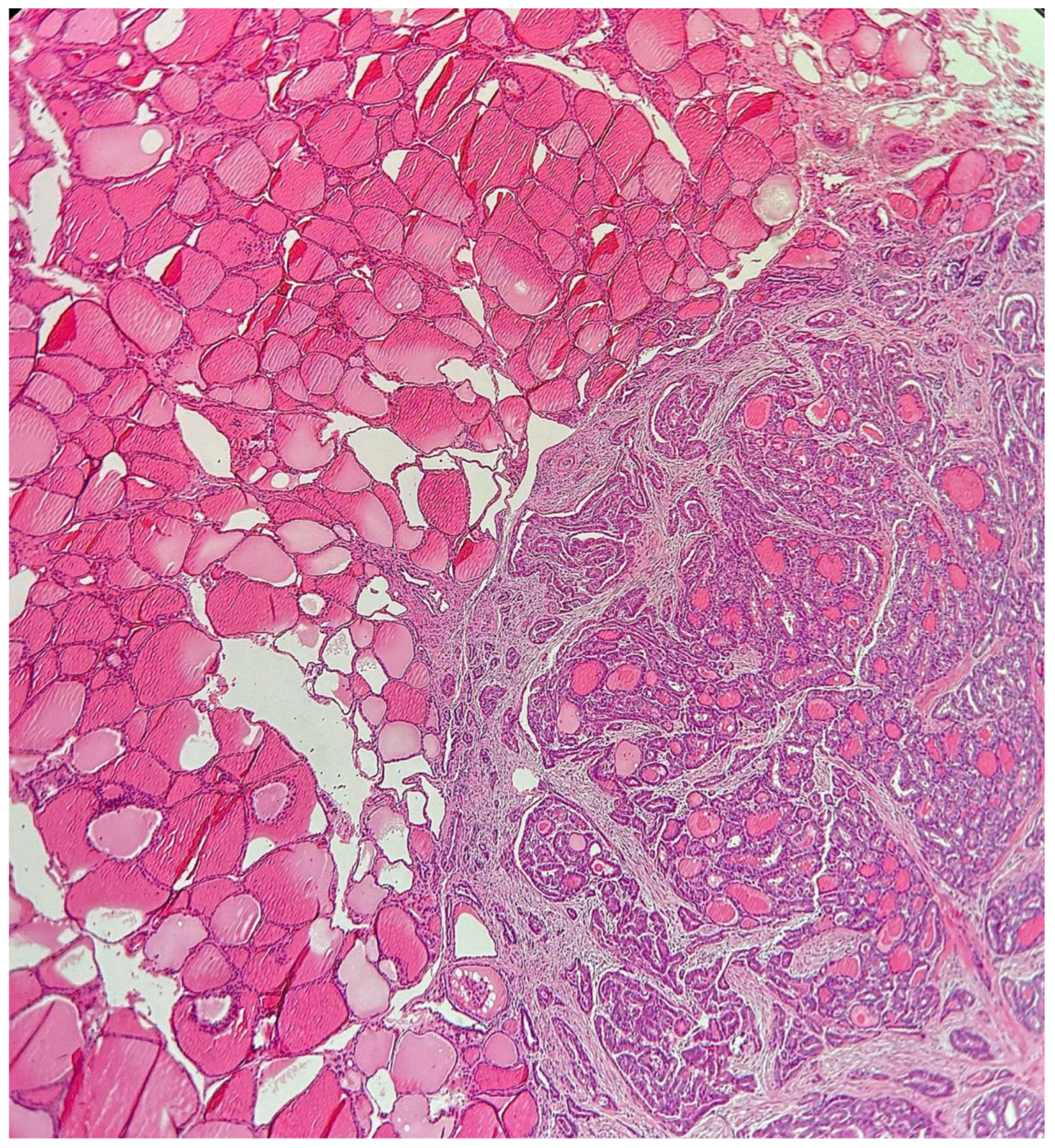

Discussion

- High-Risk PTMCs: PTMCs with high-risk features such as ETE, lymph node metastasis, aggressive histologic subtype, and proximity to the trachea or recurrent laryngeal nerve require aggressive surgical management [49], including total thyroidectomy, lymph node dissection for clinical or US-positive nodes, and radioactive iodine ablation.

- Benign Thyroid Disease: Patients with presumed benign thyroid disease are referred for surgery based on specific indications related to the thyroid pathology. Total thyroidectomy is often required for associated conditions like MNG, toxic nodular goiter, Graves’ disease, and Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT). PTMC diagnosis in these cases is typically made postoperatively through pathological examination of thyroidectomy specimens.

- Low-Risk PTMCs: For preoperatively diagnosed low-risk PTMCs, including unifocal intrathyroidal tumors with clinically negative nodes, management remains controversial. Decisions are made through a physician-patient shared decision-making process, considering patient preferences, beliefs, comorbidities, and available resources [45,50,51]. A5 or TL are viable options.

Conclusions

Disclosure

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| PTC: Papillary thyroid carcinoma | FNA: Fine needle aspiration |

| PTMC: Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma | US: Ultrasonography |

| IPTMC: Incidental PTMC | ETE: Extra-thyroidal extension |

| NIPTMC: Non-incidental PTMC | US-FNAC: ultrasound-guided FNAC |

| AS: Active surveillance | ATA: American Thyroid Association |

| TL: Total lobectomy | WHO: World Health Organization |

| TT: Total thyroidectomy | HT: Hashimoto’s thyroiditis |

| FNAC: Fine needle aspiration cytology | MNG: Multinodular goiter |

References

- Nimri O, Arqoub K, Jemal A. Jordan Cancer Registry. Amman, Jordan : Ministry of Health (MOH), 2015.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics 2020 CA cancer. J Elin 2020, 70, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira, A Nition IJ, Simo R. Papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid gland: current controversies and management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019, 27, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanova DI, Bose A, Ullmann TM, et al. Does the ATA Risk Stratification Apply to Patients with Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma? World J Surg 2020, 44, 452–460.

- Sosa JA, Hanna JW, Robinson KA, Lanman RB. Does the ATA Risk Stratification Apply to Patients with Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma? Surgery 2013, 154, 1420–1426, discussion 1426-7. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, BR. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: What is new and what has changed? Cancer 2017, 123, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair CF, Baek JH, Hands KE, et al. General Principles for the Safe Performance, Training, and Adoption of Ablation Techniques for Benign Thyroid Nodules: An American Thyroid Association Statement. Thyroid 2023, 33, 1150–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi A, Ito Y, Oda H. Insights into the Management of Papillary Microcarcinoma of the Thyroid. Thyroid 2018, 28, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebe K, Date M, Yamamoto Y. Mass screening for thyroid cancer with ultrasonography [in Japanese]. Karkinos 1994, 7, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bondeson L, Ljungberg O. Occult thyroid carcinoma at autopsy in Malmö, Sweden. Cancer. 1981, 47, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, Rosai J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs WHO Classification of Tumours, 4th Edition, Volume 10. IARC Publications, 2017. ISBN-13: 978-92-832-4493-6.

- Jung CK, Bychkov A, Kakudo K. Update from the 2022 World Health Organization Classification of Thyroid Tumors: A Standardized Diagnostic Approach. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2022, 37, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee CI, Kutlu O, Khan ZF, Picado O, Lew JI. Margin Positivity and Survival in Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: A National Cancer Database Analysis. J Am Coll Surg 2021, 233, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park YJ, Kim YA, Lee YJ, et al. Papillary microcarcinoma in comparison with larger papillary thyroid carcinoma in BRAF(V600E) mutation, clinicopathological features, and immunohistochemical findings. Head Neck 2010, 32, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Blanco J, Reddy V, Al-Khudari S, Tajudeen B, Gattuso P. Clinicopathological features of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma with a diameter less than or equal to 5 mm. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019, 40, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott MS, Gao K, Gupta R, Chua EL, Gargya A, Clark J. Management of incidental and non-incidental papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. J Laryngol Otol, 2013; 127, Suppl. 2, S17–S23.

- Kaliszewski K, Wojtczak B, Strutyńska-Karpińska M, Łukieńczuk T, Forkasiewicz Z, Domosławski P. Incidental and non-incidental thyroid microcarcinoma. Oncol Lett 2016, 12, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna H, Al-Maqbili T, Carter B, et al. Differences in the recurrence and mortality outcomes rates of incidental and nonincidental papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 329 person-years of follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 99, 2834–2843. [Google Scholar]

- Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid 2009, 19, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The 2017 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid 2017, 27, 1341–1346.

- Kaliszewski K, Zubkiewicz-Kucharska A, Kiełb P, Maksymowicz J, Krawczyk A, Krawiec O. Comparison of the prevalence of incidental and non-incidental papillary thyroid microcarcinoma during 2008-2016: a single-center experience. World J Surg Oncol 2018, 16, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi CP, Bellantone R, De Crea C, et al. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: extrathyroidal extension, lymph node metastases, and risk factors for recurrence in a high prevalence of goiter area. World J Surg 2010, 34, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante C, Attard M, Torlontano M, et al. Identification and optimal postsurgical follow-up of patients with very low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010, 95, 4882–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miccoli P, Minuto MN, Galleri D, et al. Incidental thyroid carcinoma in a large series of consecutive patients operated on for benign thyroid disease. ANZ J Surg 2006, 76, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carlos J, Ernaga A, Irigaray A. Incidentally discovered papillary thyroid microcarcinoma in patients undergoing thyroid surgery for benign disease. Endocrine 2022, 77, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slijepcevic N, Zivaljevic V, Marinkovic J, Sipetic S, Diklic A, Paunovic I. Retrospective evaluation of the incidental finding of 403 papillary thyroid microcarcinomas in 2466 patients undergoing thyroid surgery for presumed benign thyroid disease. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 330. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JJ, Chen X, Schneider DF, et al. Cancer after thyroidectomy: a multi-institutional experience with 1,523 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2013, 216, 571–577, discussion 577-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bircan HY, Koc B, Akarsu C, et al. Is Hashimoto’s thyroiditis a prognostic factor for thyroid papillary microcarcinoma? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014, 18, 1910–1915.

- Graceffa G, Patrone R, Vieni S, et al. Association between Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and papillary thyroid carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 305 patients. BMC Endocr Disord, 2019 May. 29;19(Suppl 1):26.

- Anderson L, Middleton WD, Teefey SA, et al. Hashimoto thyroiditis: Part 2, sonographic analysis of benign and malignant nodules in patients with diffuse Hashimoto thyroiditis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010, 195, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paparodis R, Imam S, Todorova-Koteva K, Staii A, Jaume JC. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis pathology and risk for thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2014, 24, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qurayshi Z, Nilubol N, Tufano RP, Kandil E. Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma in the US. J Am Coll Surg 2020, 230, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghossein R, Ganly I, Biagini A, Robenshtok E, Rivera M, Tuttle RM. Prognostic factors in papillary microcarcinoma with emphasis on histologic subtyping: a clinicopathologic study of 148 cases. Thyroid. Thyroid 2104, 24, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez JM, Nilo F, Martínez MT, et al. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: characteristics at presentation, and evaluation of clinical and histological features associated with a worse prognosis in a Latin American cohort. Arch Endocrinol Metab 2018, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Gong Y, Yan S, Chen H, Qin S, Gong R. Association between TERT promoter mutations and clinical behaviors in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 2020, 67, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing M, Liu R, Liu X, et al. BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations cooperatively identify the most aggressive papillary thyroid cancer with highest recurrence. J Clin Oncol 2014, 32, 2718–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Bishop J, Zhu G, Zhang T, Ladenson PW, Xing M. Mortality Risk Stratification by Combining BRAF V600E and TERT Promoter Mutations in Papillary Thyroid Cancer: Genetic Duet of BRAF and TERT Promoter Mutations in Thyroid Cancer Mortality. JAMA Oncol 2017, 3, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo M, da Rocha AG, Vinagre J, et al. TERT promoter mutations are a major indicator of poor outcome in differentiated thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99, E754–E765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel KN, Yip L, Lubitz CC, et al. The American Association of Endocrine Surgeons Guidelines for the Definitive Surgical Management of Thyroid Disease in Adults. Ann Surg 2020, 271, e21–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So YK, Kim MW, Son YI. Multifocality and bilaterality of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 8, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbasan O, Ilgın C, Gogas Yavuz D. Does total tumour diameter, multifocality, number of tumour foci, or laterality predict lymph node metastasis or recurrence in differentiated thyroid cancer? Endokrynol Pol 2023, 74, 153–167.

- Varshney R, Pakdaman MN, Sands N, et al. Lymph node metastasis in thyroid papillary microcarcinoma: a study of 170 patients. J Laryngol Otol 2014, 128, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirikoc A, Tam AA, Ince N, et al. Papillary thyroid microcarcinomas that metastasize to lymph nodes. Am J Otolaryngol 2021, 42, 103023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park KW, Han AY, Kim CM, Wang MB, Nguyen CT. Is lobectomy sufficient for multifocal papillary thyroid microcarcinoma? Am J Otolaryngol 2023, 44, 103881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duclos A, Peix JL, Colin C, et al. Influence of experience on performance of individual surgeons in thyroid surgery: prospective cross sectional multicentre study. BMJ 2012, 344, d8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito JP, Hay ID. Management of Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2019, 48, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir AY, Alzubaidi AN, Bashir MA, et al. he Optimal Parathyroid Hormone Cut-Off Threshold for Early and Safe Management of Hypocalcemia After Total Thyroidectomy. Endocr Pract 2021, 27, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu XM, Wan Y, Sippel RS, Chen H. Should all papillary thyroid microcarcinomas be aggressively treated? An analysis of 18,445 cases. Ann Surg 2011, 254, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir AY, Zaheri MM, Obed A, et al. Patients’ preferences impact on decision-making for clinical solitary thyroid nodule in a global healthcare setting: a clinical study. Series Endo Diab Met 2021, 3, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koot A, Soares P, Robenshtok E, et al. Position paper from the Endocrine Task Force of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) on the management and shared decision making in patients with low-risk micro papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2023, 179, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).