Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Yu, S.; McDonald, T.; Jesudason, C.; Stiller, K.; Sullivan, T. Orthopedic inpatients' ability to accurately reproduce partial weight bearing orders. Orthopedics 2014, 37, e10–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aesch, A.V.v.; Häckel, S.; Kämpf, T.; Baur, H.; Bastian, J.D. Audio-Biofeedback Versus the Scale Method for Improving Partial Weight-Bearing Adherence in Healthy Older Adults: A Randomised Trial. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 2024, 50, 2915–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, J.R.; Ackland, T.; Lloyd, D.G.; Wood, D. Accuracy of Partial Weight Bearing After Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2008, 89, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vusse, M.v.d.; Kalmet, P.H.S.; Bastiaenen, C.H.G.; Horn, Y.; Brink, P.R.; Seelen, H.A. Is the AO Guideline for Postoperative Treatment of Tibial Plateau Fractures Still Decisive? A Survey Among Orthopaedic Surgeons and Trauma Surgeons in the Netherlands. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 2017, 137, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, Ø.; Gulliksen, W.; Kwiatkowski, A.D.; Skavø, M.; Isern, H.; Shayestehpour, M.; Steinert, M.; Bye, R.T.; Hellevik, A.I. Implementation and Evaluation of a Vibrotactile Assisted Monitoring and Correction System for Partial Weight-Bearing in Lower Extremities. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abdalbary, S.A. Partial Weight Bearing in Hip Fracture Rehabilitation. Future Science Oa 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Xu, X.; Chai, Z.; Wang, T.; Shen, X.; Sun, T. A Wearable Biofeedback Device for Monitoring Tibial Load During Partial Weight-Bearing Walking. Ieee Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023, 31, 3428–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieshout, R.v.; Stukstette, M.J.; Bie, R.A.d.; Vanwanseele, B.; Pisters, M.F. Biofeedback in Partial Weight Bearing: Validity of 3 Different Devices. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 2016, 46, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hustedt, J.W.; Blizzard, D.J.; Baumgaertner, M.R.; Leslie, M.; Grauer, J.N. Lower-Extremity Weight-Bearing Compliance Is Maintained Over Time After Biofeedback Training. Orthopedics 2012, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, T.; Gervasoni, E.; Arienti, C.; Lazzarini, S.G.; Négrini, S.; Crea, S.; Cattaneo, D.; Carrozza, M.C. Wearable Devices for Biofeedback Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis to Design Application Rules and Estimate the Effectiveness on Balance and Gait Outcomes in Neurological Diseases. Sensors 2021, 21, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hustedt, J.W.; Blizzard, D.J.; Baumgaertner, M.R.; Leslie, M.; Grauer, J.N. Effect of Age on Partial Weight-Bearing Training. Orthopedics 2012, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raaben, M.; Redzwan, S.; Augustine, R.; Blokhuis, T.J. COMplex Fracture Orthopedic Rehabilitation (COMFORT) - Real-Time Visual Biofeedback on Weight Bearing Versus Standard Training Methods in the Treatment of Proximal Femur Fractures in the Elderly: Study Protocol for a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

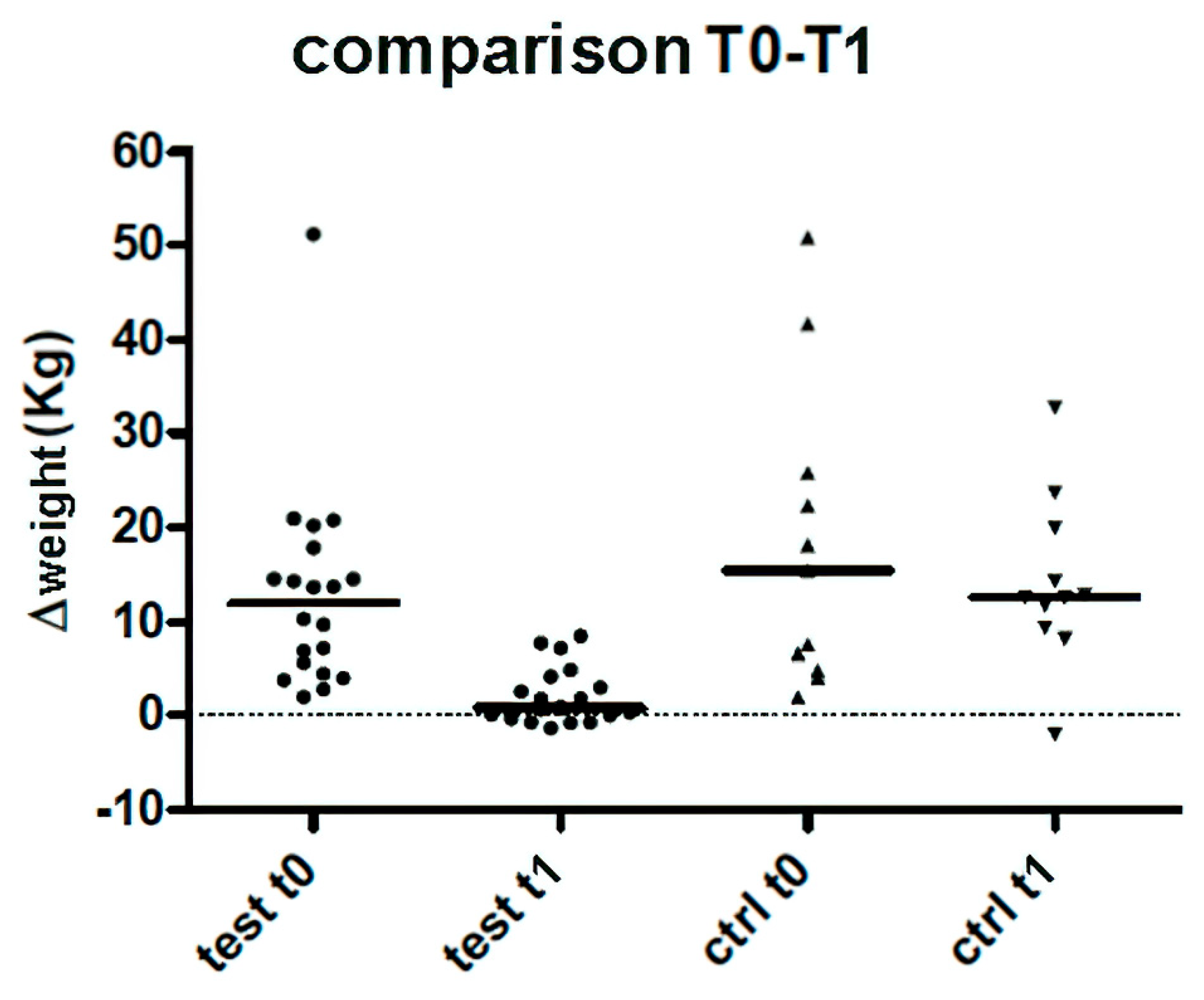

| TEST GROUP | Weight (Kg) | Δ loaded weight T0 | Δloaded weight T0 | Δ loaded weight T1 | NRS T0 | NRS T1 | 6MWT T0 | 6MWT T1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 78 | 12,9 | 5,6 | 2 | 4,2 | 1,6 | 35,4 | 206,2 |

| Median | 78,5 | 12 | 5 | 0,8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 220,8 |

| St. Dev. | 16,8 | 10,9 | 8,5 | 3 | 2,5 | 1,4 | 66,1 | 90,2 |

| CONTROL GROUP | Weight (Kg) | Δ loaded weight | Δ loaded weight T1 | NRS T0 | NRS T1 | 6MWT T0 | 6MWT T1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 69,9 | 16,3 | 12,8 | 4,2 | 2 | 45,9 | 181,1 |

| Median | 61 | 15,4 | 12,6 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 219 |

| St. Dev. | 14,2 | 14,7 | 8,4 | 1,7 | 1,9 | 74,4 | 92,3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).