Decades of research in foreign language learning have established two major empirical realities regarding the ultimate outcome of second language acquisition (Bley-Vroman, 1990; 2009). First, there is considerable variation among adult learners: while some attain a very high level of proficiency, others reach only moderate or minimal levels. Second, there is a marked disparity in ultimate attainment between younger and older learners.

1These observed realities are underpinned by complex dynamics involving interactions between external and internal forces (MacWhinney, 2018), giving rise to the evolving language making capacity (Meisel, 2013), the human ability to acquire and sustain language, across the lifespan.

Despite a wealth of past and ongoing explanatory efforts, the field remains fragmented. Perspectives from cognitive, biological, linguistic, and socio-psychological domains remain largely siloed and often conflict with one another. As a result, general understanding has stagnated, and practical insights have been limited. Most importantly, predictive power continues to elude both past and current research.

In recent years, however, an interdisciplinary theory has emerged: Energy-Conservation Theory in Second Language Acquisition (ECT-L2A). At its core, ECT-L2A is a general model of human learning extended to foreign language acquisition. Drawing on Newtonian dynamics and universal laws of energy conservation and angular momentum, it posits parallels between mechanical and cognitive energies and theorizes their dynamic interactions in second language learning.

ECT-L2A integrates previously disparate perspectives on ultimate attainment, offering a unified mathematical framework to account for both dimensions of inter-learner differential attainment outlined above (Han & Bao, 2023; Han, Bao, & Wiita, 2017a, b), along with a set of testable predictions. One such prediction is that ultimate attainment in adult learners will inevitably fall short of native-level proficiency, defined as basic language cognition shared by all native speakers (Hulstijn, 2015). Another is that nativelike proficiency is attainable only when acquisition begins in early childhood, within the critical period (Lenneberg, 1967).

Realizing the full potential of this theory, however, requires further substantiation of its key components. To that end, the present article focuses on one such element: effective potential, which captures the interaction between centrifugal energy (associated with linguistic distance) and potential energy (related to the influence of the target language) in shaping ultimate attainment. Using AI-generated data on linguistic distance – defined as “the extent to which languages differ from each other” (Chiswick & Miller, 2005, p. 1) – provided by ChatGPT-4o, we compute the difficulty level of foreign language learning and quantify its relationship with ultimate attainment. This work represents a crucial step toward establishing both the explanatory scope and predictive power of ECT-L2A.

In the sections that follow, we first introduce ECT-L2A as the theoretical framework. After that, we outline the study’s procedure, present the relevant data generated by ChatGPT, and describe the mathematical equations used to compute foreign language learning difficulty. We conclude with a brief discussion of the theoretical and practical implications of this work.

ENERGY-CONSERVATION THEORY FOR L2A (ECT-L2A)

ECT-L2A is a theoretical model of the divergent states of ultimate attainment in foreign language learning (Han & Bao, 2023; Han, Bao, & Wiita, 2017a, b). Drawing on the laws of energy conservation and angular momentum, it theorizes the dynamic transformation and conservation of internal (learner) and external (environmental) energies, in engineering ultimate attainment. As such, the model incorporates both nature and nurture variables, specifically by positing five parameters: target language environment (input), learner motivation, learner aptitude, linguistic distance between the first language (L1) and the target language (TL), and the developing learner. The theory mathematically demonstrates that the interaction of these parameters results in varying levels of L2 ultimate attainment.

ECT-L2A draws parallels between mechanical energies and human learning energies: kinetic energy corresponds to motivation and aptitude, potential energy to environmental energy, and centrifugal energy to L1-TL deviation energy (Han et al, 2017a). Each of these energies plays a distinct yet dynamic role. As the learner progresses, the dominance of individual energies shifts, while the total energy remains constant.

Mathematically, ECT-L2A is expressed as:

Where:

is the learner’s position in the learning process relative to the TL;

η represents the linguistic distance between the learner’s L1 and the TL;

ρ is the influence factor of the linguistic environment (i.e., TL input);

ϵ is the total energy of the system, which includes both the learner and the TL;

ζ(r) denotes learner motivation energy, a function of the learner position r;

Λ is the learner’s aptitude energy, assumed to be constant;

represents the deviation energy; and

is the environmental energy.

Note that the negative sign on - reflects the attractive force exerted by the TL, representing the energy it provides to the learner during the acquisition process.

The influence factor ρ reflects the attractiveness and popularity of the TL. A practical proxy for ρ can be the number of non-native speakers of the TL worldwide (see

Table 1).

The linguistic distance η represents the deviation between the learner’s L1 and the TL. For adult learners, this deviation can be measured directly as the L1-TL distance (Chiswick & Miller, 2005; Crystal, 1987; Ellis, 1994).

Motivation energy ζ(r) varies over the course of the learning process and tends to diminish as r approaches a critical point r0 , where the learner is blocked by the centrifugal barrier – a point beyond which further progress becomes impossible.

In this formulation, the term (deviation energy) acts as the barrier, and the term (environmental energy) functions as the attractive force, drawing the learner toward the target at r=0.

According to Equation (1), the total learning energy ϵ is the sum of motivation energy ζ(r), aptitude Λ (a constant), deviation energy , and environmental energy . Under the overarching condition that the total energy remains constant throughout the learning process (ϵ = constant), each type of energy plays a distinct role and can transform into another as the learner’s position changes over time.

In sum, throughout the learning process, each component – motivation (an internal factor), deviation (a mix of internal and external factors), and environment (an external factor) – interacts dynamically to maintain the balance of total energy within the system.

This energy system applies to all foreign language learners, with total energy remaining constant for each individual learner. However, total energy varies between learners, resulting in different levels of ultimate attainment (i.e., closer to or further from the TL), denoted by

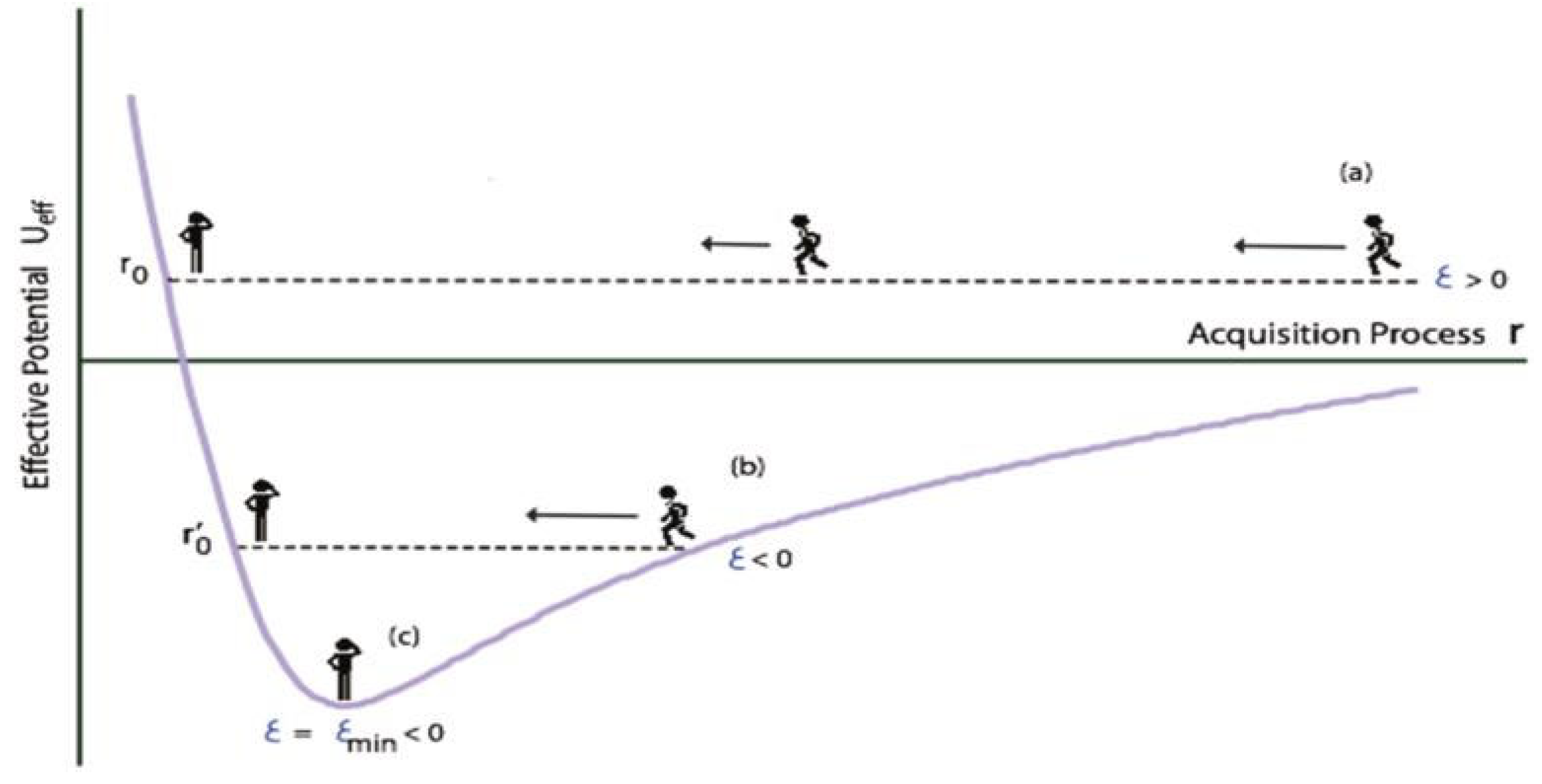

r0. This is illustrated in

Figure 1, where

and

represent the ultimate attainments of learners with different total energy levels (

ϵ>0 or

ϵ<0), and where effective potential energy,

Ueff (

r), is the sum of deviation energy and the potential energy:

Figure 1 below illustrates that individuals’ total energies, indicative of their language making capacities (Meisel, 2013), determine their levels of attainment.

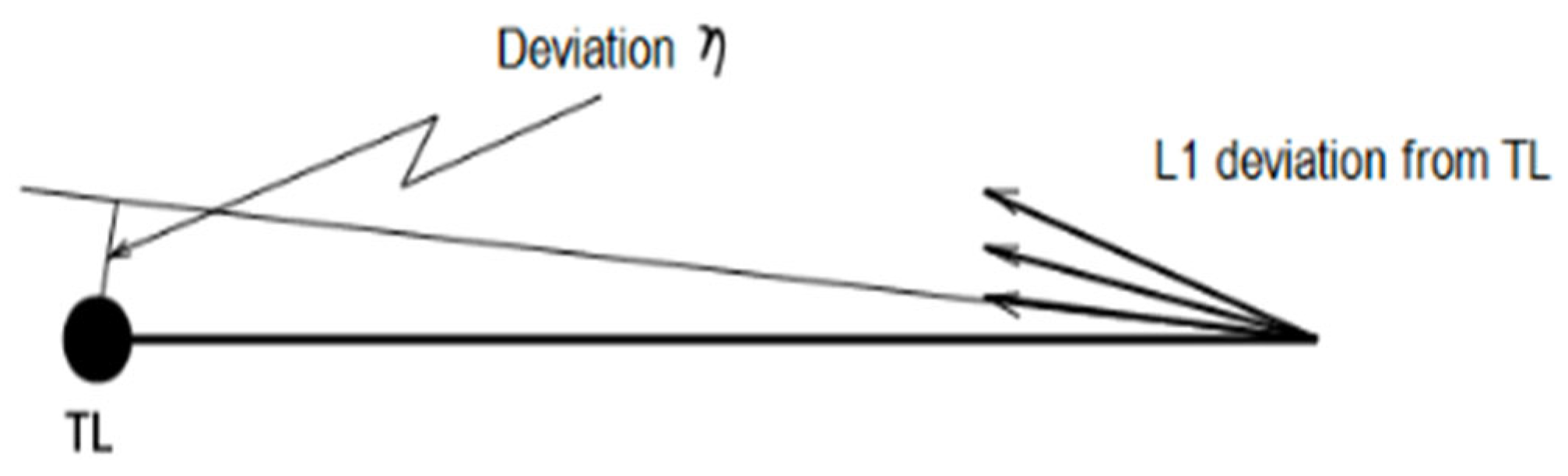

Figure 2 provides a geometric expression of the L1-TL deviation,

η, which is analogous to the angular momentum of an object moving in a central force field (Bao, Hadrava, & Ostgaard, 1994; Bao, Wiita, & Hadrava, 1996). The deviation from the TL (the linguistic distance between L1 and TL) varies with different L1-TL pairings.

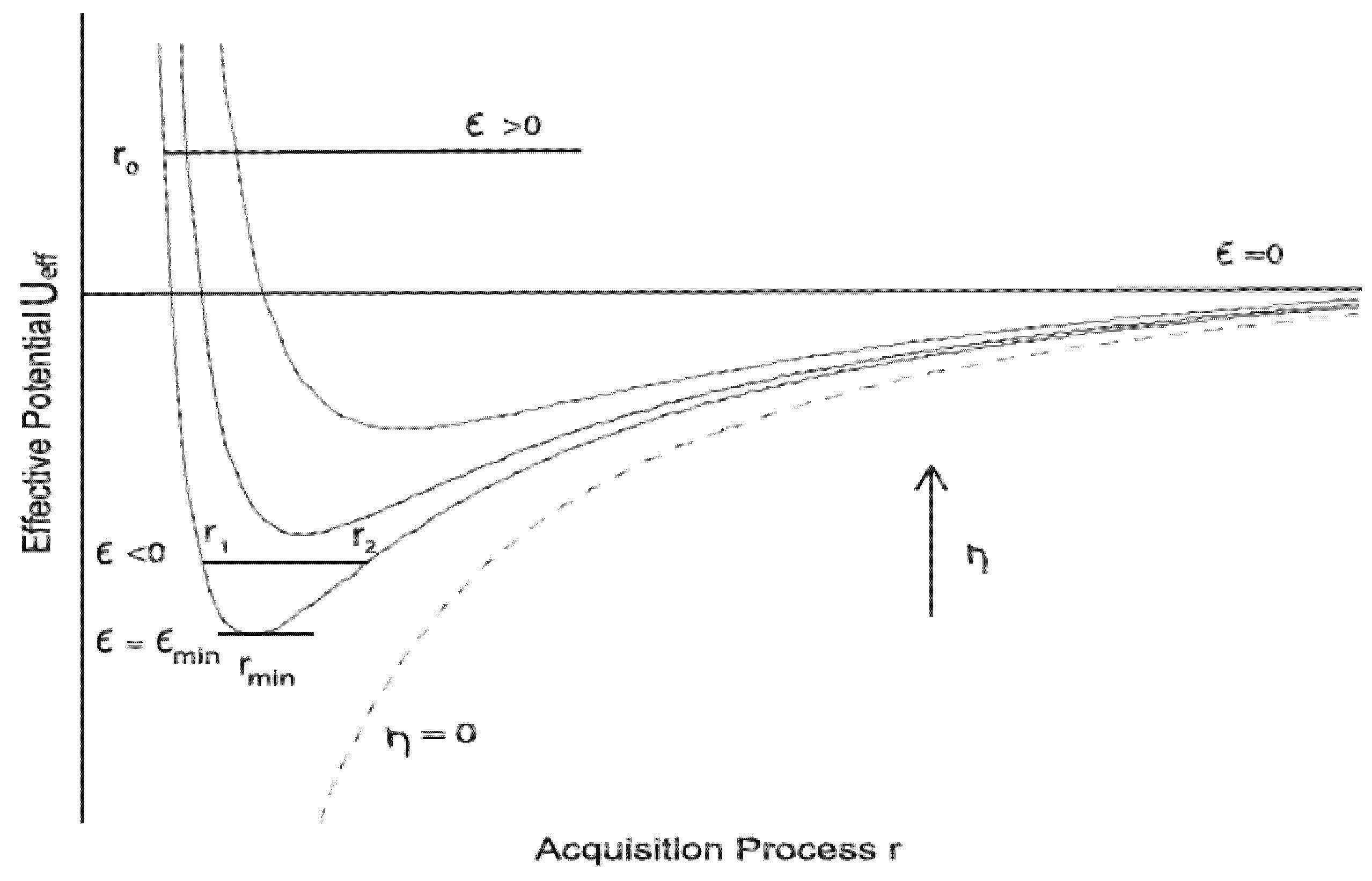

Figure 3 illustrates differential ultimate attainment (indicated by

r0) as a function of the deviation parameter

η. As

η increases, the level of attainment decreases or

r0 increases (see the horizontal axis for

ϵ>0), indicating that the learner ends up further from the target (

r0=0, represented by the vertical axis). The relationship is evidently non-linear.

For adult learners, ECT-L2A predicts, inter alia, that high attainment is possible, but full attainment is not (see Equation 1, as long as η > 0). For young learners, nativelike attainment is possible, but only when the onset of acquisition happens during early childhood (Han & Bao, 2023). The theory further predicts that while motivation and aptitude contribute to a learner’s total energy, their influence is largely limited to the early stages of development. Most profoundly, ECT-L2A posits that the L1-TL deviation is what holds attainment at an asymptote.

Given the centrality of the deviation parameter (linguistic distance) in determining L2 ultimate attainment, we set out to compute its value using the linguistic distance data provided by ChatGPT.

METHOD

To begin, we asked ChatGPT to rank target languages, in order to assess the value of each TL. Specifically, we requested data on which of the world’s top 10 languages (by total number of speakers) have the highest numbers of nonnative speakers. The results (see

Table 1) indicate that English is by far the most widely spoken TL.

Next, we asked ChatGPT to provide data on the linguistic distances between English and the other nine most widely spoken languages.

Using this data, we then mathematically computed two values for the deviation parameter in ECT-L2A (η): (a) an absolute difficulty level (D), which applies universally across languages, and (b) a relative difficulty level (RD), which applies in cases where learners have different native languages but share the same target language.

RESULTS

Table 1 and

Table 2 below present the data provided by ChatGPT.

Table 1 lists the top 10 languages with the highest number of non-native speakers, and

Table 2 provides estimated linguistic distances between English and nine other languages.

2

Table 1 gives three sets of numbers respectively for native speakers, non-native speakers, and total speakers. For the purposes of this study, our focus is solely on the number of nonnative speakers. Non-native speakers are defined as individuals who have acquired a language after early childhood, typically as a second language, rather than as their first.

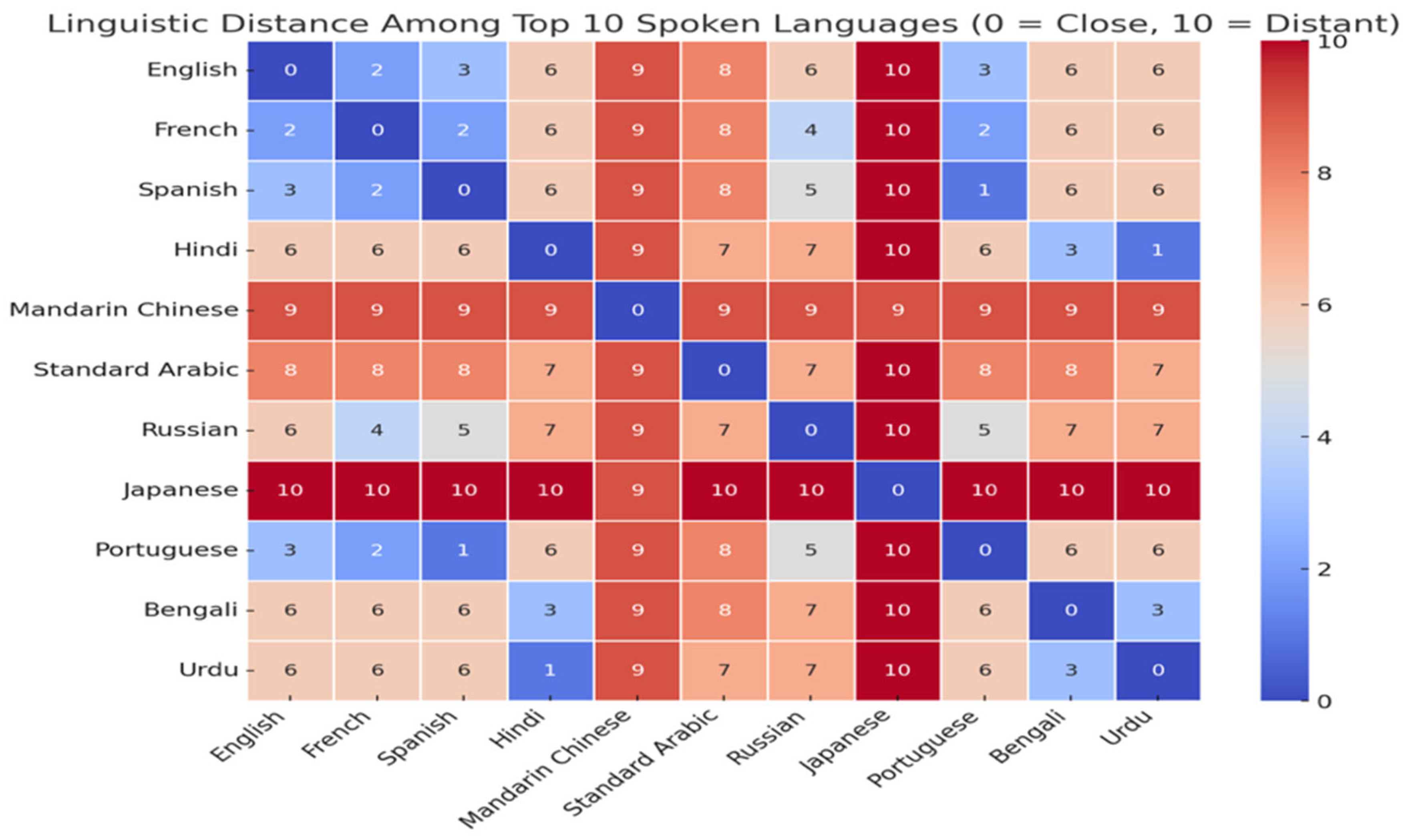

Table 2 shows that the closest to English are French, Spanish, and Portuguese, all belonging to the Indo-European family, while the moderately related languages are Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, and Russian, which are also part of the Indo-European family but in its more distant branches. The highly distant languages are Arabic, Mandarin Chinese and Japanese, which belong to different language families, with different structures and scripts. A visual display is given in

Figure 4 (produced by ChatGPT).

Figure 4 displays a heatmap visualizing the linguistic distances among the top 10 spoken languages. The scale ranges from 0 (closely related) to 10 (completely unrelated). Darker shades indicate greater linguistic differences, while lighter shades show closer relationships. The lower the score, the closer the language is to English in terms of vocabulary, grammar, and overall structure.

Using the data elicited from ChatGPT, we set out to quantify language learning difficulty through linguistic distance.

As discussed earlier, in ECT-L2A (see equation 1), linguistic distance, denoted by

η, plays a central role in engineering various levels of ultimate attainment.

Figure 3 illustrates that the greater the value of

η, the larger the value of

r0, which indicates how close a learner can approach the TL. This proximity, in turn, reflects the difficulty level (

D) of the TL for that learner. Mathematically, this relationship is expressed as:

Since

r0 represents the minimum distance a learner can reach in relation to TL, it also indicates the difficulty level,

DL, of TL. The smaller the

r0, the lower the

DL. Assuming

, equation (3) simplifies to:

Equation (4) shows that the difficulty level of TL is not only related to its linguistic distance from the learner’s native language (represented by

), but also inversely proportional to the influence factor or accessibility of TL (represented by

. For example, if the TL is globally popular or widely available, such as English (see

Table 1), it becomes easier to learn, which aligns with common sense.

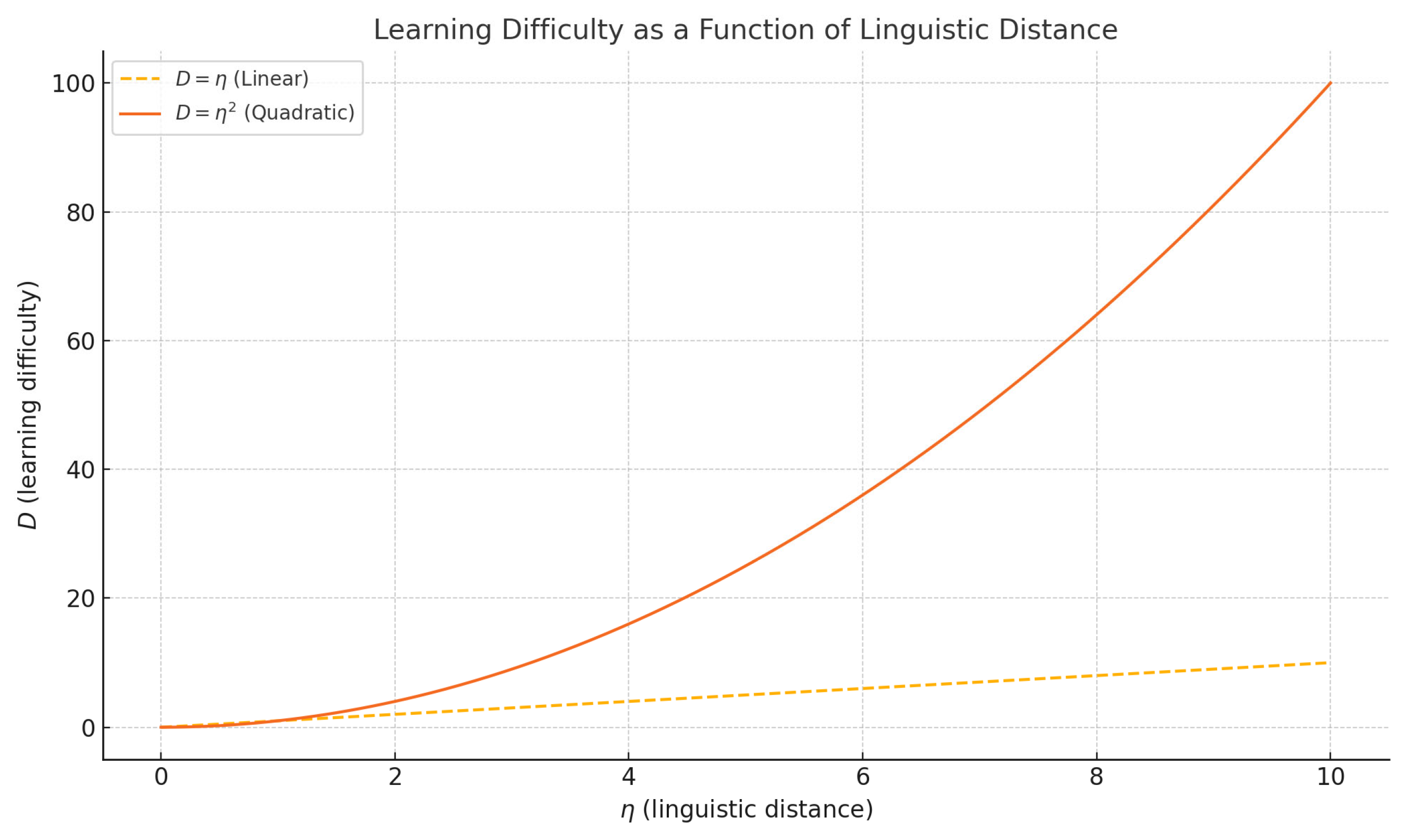

In foreign language learning research, it has long been assumed that the greater the distance between a learner’s L1and the TL, the more difficult the learning process (Corder, 1981; Crystal, 1987; Ellis, 1994; Lado, 1957; Weinreich, 1953). However, equation (4) quantifies this relationship and reveals that

it is quadratic, not linear. This is illustrated in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 shows the relationship between linguistic distance (

) and learning difficulty (

). The dashed line represents the linear relationship (

D=

) and the solid line represents the quadratic relationship (

D=

).

Further, extending the concept of learning difficulty to specific scenarios, such as foreign language learners of different L1 backgrounds learning the same language (TL), a relative difficulty (

RD) value can be computed:

Equation (5) yields a divergence value between two L1s (

L1a and

L1b) with respect to the same TL. For example, to compare the difficulty of learning English for Japanese and French speakers, the relative difficulty ratio,

, is given by:

Substituting from equation (4), we get:

Here, and represent the linguistic distances from Japanese and French, respectively, to the TL (English). Note that is independent of , and should always be If >1, it indicates that English is more difficult for Japanese speakers than for French speakers. The magnitude of reflects the scale of divergence between the two L1s.

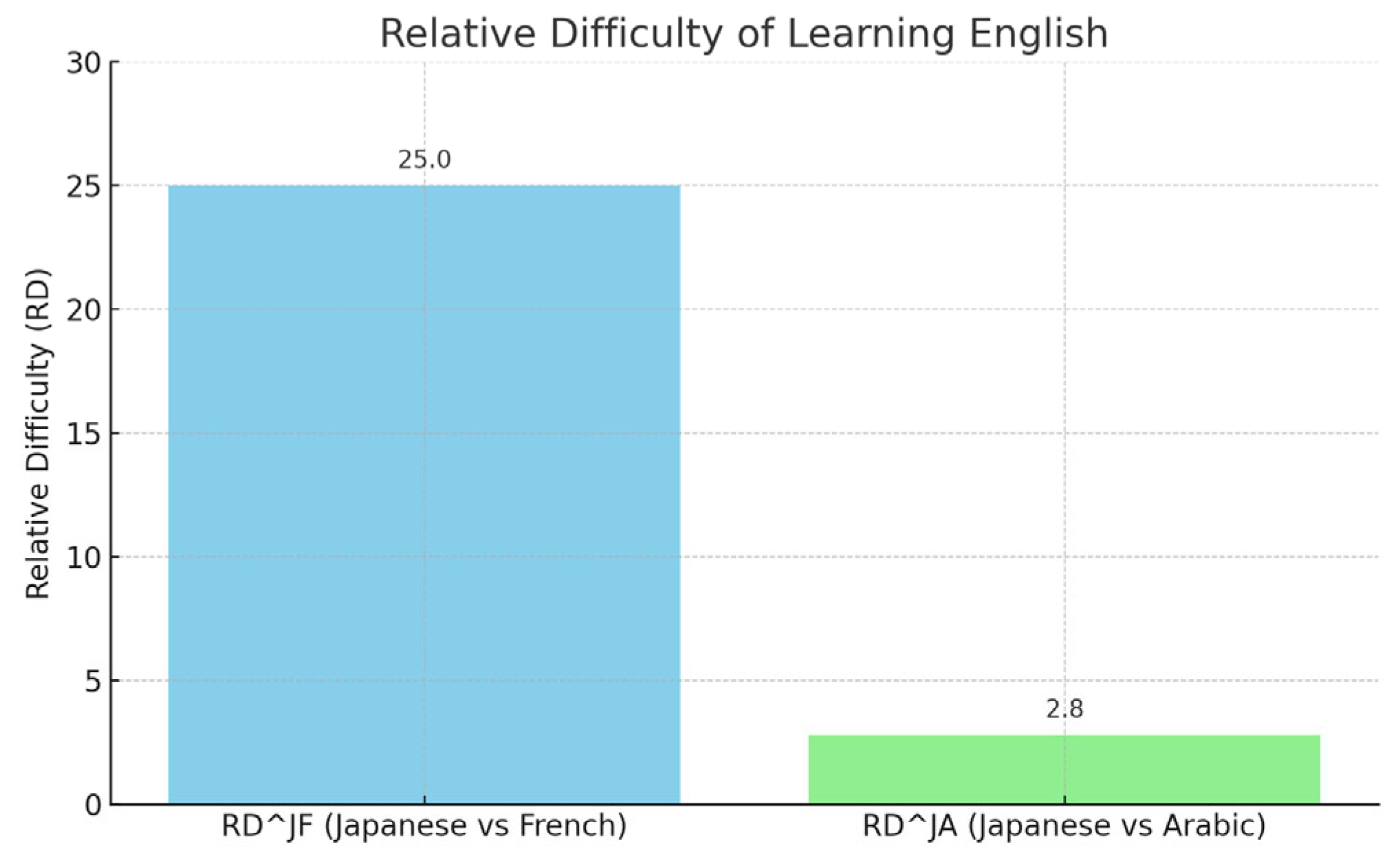

Below are two illustrative examples using data provided by ChatGPT (see

Table 2), comparing Japanese with French and Arabic learners of English:

-

Japanese vs. French

-

Japanese vs. Arabic

Thus, while both French and Arabic speakers find English easier to learn than Japanese speakers, the divergence between French and Japanese speakers (

=25) is much greater than that between Arabic and Japanese speakers (

=2.8), as illustrated in

Figure 6.

Figure 6 illustrates that English is much more difficult for Japanese speakers compared to French or Arabic speakers, with the gap significantly larger between Japanese and French. Conversely, it is much easier for French speakers learning English to reach a higher level of ultimate attainment than for Japanese speakers and to a lesser extent Arabic speakers.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

ECT-L2A, among other things, embodies and advances systems thinking, guided and enriched by insights from physics, mathematics, and applied linguistics. This interdisciplinary theory conceptualizes foreign language attainment as a dynamic process involving the interaction of multiple energy components that catalyze both interim and ultimate states of learning. Within this framework, linguistic distance functions as a key force, exerting its influence at a specific stage in the learning trajectory. Both the timing of its maximal impact and its functional role, that is, holding progress at an asymptote, are explicitly defined.

As a mathematic model, ECT-L2A enables quantifiable comparisons of foreign language attainment. As illustrated in this article, the integration of AI-generated data renders such comparisons more tangible and precise than ever before.

Theoretically, the human-AI alliance holds significant potential to expand both the explanatory scope and predictive power of ECT-L2A. The present study exemplifies this potential. Fundamentally, the model can be applied to explain and predict foreign language attainment for any pairing of L1 and TL, at both the group and individual levels.

In the work presented above, we focused on demonstrating how human-AI collaboration can be used to quantify the impact of the L1-TL deviation parameter on language learning difficulty. For the sake of clarity and illustration, we confined our scenario to English as the TL. However, the model’s applicability is far broader. Using data provided by ChatGPT, such as those shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, and

Figure 4, and applying ECT-L2A equations (4) and (5), we can compute the difficulty level for any L1-TL pair (e.g., L1Hindi, TL Spanish). Moreover, this approach enables assessment of differential difficulty levels across multiple L1s converging on the same TL. The potential for application is both vast and transformative.

A key conclusion drawn in this article is that the relationship between linguistic distance and ultimate attainment is quadratic, not linear, as surface-level linguistic distance data might suggest (Chiswick & Miller, 2005). This insight is profound. Among its implications is the understanding that learners from different L1 backgrounds require varying levels of effort and time to attain proficiency in a given TL. This, in turn, has practical consequences for decisions related to resource allocation, learner support, and the time commitment necessary to achieve language learning goals.

The importance of linguistic distance and its relationship to foreign language proficiency has long been a topic of intense interest among economists, particularly in relation to migration patterns, migrant success in destination countries, and international trade (see, e.g., Chiswick & Miller, 2005; Isphording & Sebastian, 2011), as well as among applied linguists concerned with the human capacity for language across the lifespan and the efficacy of instruction (see, e.g., Crystal, 1987; Ellis, 1994; Lado, 1957; Jaekel, Ritter & Jaekel, 2023; Schepens, et al., 2016, 2022). Behavioral studies using participants’ language proficiency scores and linguistic distance scores have consistently demonstrated an instrumental relationship between the two. For example, Chiswick and Miller (2005) observed that “when other determinants of English language proficiency are the same, the greater the measure of linguistic distance, the poorer is the respondent’s English language proficiency” (p. 1).

However, existing studies are notably constrained by a non-systems perspective. While often acknowledging that language acquisition is a complex process involving social, cognitive, psychological, and economic factors, they tend to isolate linguistic distance rather than examine it in conjunction with the broader set of interacting variables. This has led to a narrow, reductionist, and non-dynamic understanding of both language attainment and the role played by linguistic distance. The persistence of this limitation is evident in the fact that, despite numerous studies over several decades, our overall understanding has not significantly advanced. Analyses based solely on statistical correlations between linguistic distance and language proficiency scores tend to reveal a monotonic, linear relationship – a pattern that oversimplifies the complex nature of foreign language acquisition.

With ECT-L2A mathematically demonstrating a quadratic relationship between foreign language learners’ ultimate attainment and linguistic distance, and, more importantly, offering a holistic, systems-level perspective on inter-learner differential attainment, new avenues open up for both economists and applied linguists to pursue empirical investigations beyond linear modals. Such studies are likely to yield findings with greater scientific rigor and ecological validity.

References

- Bley-Vroman, R. (1990). The logical problem of second language learning. Linguistic Analysis, 20(1-2), 3-49.

- Bley-Vroman, R. (2009). The evolving context of the fundamental difference hypothesis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 31(Special Issue 02), 175-198. [CrossRef]

- Bao G, Hadrava P, Ostgaard E. (1994). Multiple images and light curves of an emitting source on a relativistic eccentric orbit around a black hole. Astrophysics J. 425, 63–71.

- Bao G, Wiita P, Hadrava P. Energy-dependent polarization variability as a black hole signature. Phys Rev Lett (1996) 77:12–5.

- Chiswick, B., & Miller, P. (2005). Linguistic distance: A quantitative measure of the distance between English and other languages Journal of Multicultural and Multilingual Development, 26, 1-11.

- Corder, S.P. (1981). Error analysis and interlanguage. Oxford University Press.

- Crystal, D. (1987). The Cambridge encyclopedia of language: Cambridge University Press.

- Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

- Han, Z-H., Bao, G, & Wiita, P. (2017a). Energy conservation: A theory of L2 ultimate attainment. International Review of Applied Linguistics (IRAL), 50(2), 133-164.

- Han, Z-H., Bao, G., & Wiita, P. (2017b). Energy conservation in SLA: The simplicity of a complex adaptive system. In L. Ortega & Z-H. Han (Eds.), Complexity theory and language development. In celebration of Diane Larsen-Freeman (pp. 210-231). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Han, Z-H. & Bao, G. (2023), Critical period in second language acquisition: The age-attainment geometry. Frontiers in Physics, 11:1142584. [CrossRef]

- Hulstijn, J. H. (2015). Language proficiency in native and non-native speakers: Theory and research. John Benjamins.

- Isphording, I., & Sebastian, O. (2011). Linguistic distance and the language fluency of immigrants. Ruhr Economic Papers, 274.

- Jaekel, N., Ritter, M., & Jaekel, J. (2023). Associations of students’ linguistic distance to the language of instruction and classroom composition with English reading and writing skills Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 1287-1309.

- Lado, R. (1957). Linguistics across cultures: Applied linguistics for language teachers. University of Michigan.

- Lenneberg, E. (1967). Biological foundations of language. Wiley.

- MacWhinney, B. (2018). A unified model of first and second language learning. In M. Hickmann, E. Veneziano, & H. Jisa (Eds.), Sources of variation in first language acquisition: Language, contexts, and learners (pp. 288-310). John Benjamins.

- Meisel, J. (2013). Sensitive phases in successive language acquisition: The critical period hypothesis revisited. In C. Boeckx & K. Grohmann (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of biolinguistics (pp. 69-85). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schepens, J., van der Slik, F., & van Hout, R. (2016). L1 and L2 distance effects in learning L3 Dutch. Language Learning 66, 224-256.

- Schepens, J., Roeland, W., van Hout, F., & van der Slik, F. (2022). Linguistic dissimilarity increases age-related decline in adult language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Van der Slik, F. (2010). Acquisition of Dutch as a second language Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 32, 401-432.

- Weinreich, U. (1953). Languages in contact (Vol. 1). Publication of the Linguistic Circle of New York.

| 1 |

The critical period phenomenon continues to rank among the 125 major scientific questions yet to be resolved. |

| 2 |

Economists and applied linguists have long struggled to develop quantitative measures of linguistic distance (Crystal, 1987; McCloskey, 1998; Van der Slik, 2010). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).