1. Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) show outstanding performance in various natural language processing (NLP) tasks and possess the ability to generate coherent and fluent text. However, these models have limitations in the form of hallucinations—i.e., generating content not grounded in their pre-trained knowledge or provided context. Such issues can pose serious risks in fields that demand high reliability, including medicine and law. For instance, in a medical context, a model might provide incorrect diagnostic information, while in the legal domain, it might offer inaccurate legal advice, leading to tangible harm.

Existing approaches to mitigating hallucinations can be broadly classified into prompt-based methods and decoding strategies [

1] Prompt-based methods aim to have the model better reflect contextual information by structuring input data or incorporating external resources. Representative examples include Chain of Thought (CoT) [

2], which guides step-by-step reasoning, and Tree of Thought (ToT) [

3], which exploits multi-path inference. However, recent research indicates that these approaches do not directly modify the internal representations of the model, thus hallucinations can persist, particularly in tasks requiring complex reasoning.

To overcome these limitations, research attention has increasingly turned to decoding strategies. Context-Aware Decoding (CAD) [

4] highlights contextual information by leveraging the probability difference of outputs when context is presented versus omitted. However, CAD can overly suppress a model’s pre-trained knowledge, leading to diminished text quality. Another method, Decoding by Contrasting Layers (DoLa) [

5], analyzes differences among transformer layers to accentuate the factual knowledge stored in higher layers. Yet DoLa relies solely on internal model knowledge rather than external sources, and it only operates during the inference phase. Both methods share a common limitation: failing to effectively balance contextual information with pre-trained knowledge.

To address this shortcoming, in this paper we propose Layer-Aware Contextual Decoding (LACD), which emphasizes contextual information while effectively utilizing information within model layers. LACD dynamically adjusts the balance between context and pre-trained knowledge, analyzing token distributions at the layer level so the importance of contextual information is reflected. Furthermore, it considers interactions among layers to seamlessly integrate the model’s internal knowledge with the newly provided context. As a result, the model is less likely to over-rely on its pre-trained knowledge and can more precisely incorporate the newly given context. Ultimately, LACD helps the model clearly represent the provided context while generating text that is more factual and trustworthy.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides an overview of existing approaches to hallucination mitigation and baseline decoding methods, serving as the foundation for our work. In

Section 3, we introduce our proposed LACD framework, illustrating how layer-level token distributions can help balance newly provided context with the model’s internal knowledge.

Section 4 then describes our experimental evaluation, including the datasets, experimental setup, and prompt construction for few-shot examples. Next,

Section 5 presents our empirical findings, comparing LACD’s performance against existing advanced methods Subsequently,

Section 6 discusses broader implications, potential limitations, and future research directions. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes the primary contributions and outlines directions for further investigation.

2. Relative Works

2.1. Hallucination

With the advancement of large language models (LLMs), hallucination has emerged as an important research topic. Hallucination refers to information generated by LLMs without factual basis, including content that either does not exist or contradicts the given context. This phenomenon significantly limits the application of LLMs in domains requiring high reliability, such as summarization, question answering (QA), legal, and medical data processing [

1].

The causes of hallucination are broadly categorized into three types[

6]. First, conflicts between a model’s prior knowledge and the input context can cause hallucination. LLMs have strong prior knowledge learned from vast amounts of web data, making them prone to generating unrealistic responses when encountering conflicting new information. Second, insufficient input context can lead to hallucination. When inadequate information is provided, the model attempts to fill in incomplete data based on learned patterns, potentially resulting in hallucination. Third, limitations in decoding strategies are responsible. Due to the probabilistic nature of autoregressive text generation, LLMs can assign non-negligible probabilities to tokens lacking factual grounding, particularly under ambiguous or conflicting contexts.

Various studies have been conducted to address this issue, notably proposing methods such as CAD and DoLa. These approaches aim to mitigate hallucination by fully utilizing the model’s existing pretrained capabilities, thus reducing hallucination without the need for additional fine-tuning.

2.2. CAD

Another recent approach proposed to address hallucinations caused by conflicts between context and prior knowledge in large language models (LLMs) is Context Aware Decoding (CAD).

CAD employs a decoding strategy that contrasts the probability distributions predicted by the model in "context-provided" and "context-free" states, allowing contextual information to effectively override the model’s prior knowledge. Specifically, it leverages the concept of pointwise mutual information (PMI) to reweight the probability distribution by assigning higher weights to tokens whose probabilities significantly increase when context is provided.

This approach encourages pretrained models to actively incorporate newly provided contexts without additional fine-tuning, effectively mitigating hallucinations in tasks such as summarization and QA. Notably, CAD has shown particular effectiveness in knowledge-conflict scenarios—such as when updated information contradicts outdated knowledge stored in the model—enabling accurate context-based responses.

Empirical evaluations using summarization datasets such as CNN-DM[

7] and XSUM[

8], as well as knowledge conflict tasks like NQ-Swap[

9] and MemoTrap[

10], have demonstrated significant improvements in ROUGE-L, accuracy, and factuality metrics. These results illustrate that CAD effectively reduces hallucinations and enhances factuality simply by strengthening the emphasis on contextual information during decoding, without retraining model parameters.

2.3. DoLa

DoLa has been proposed as an approach to mitigate hallucinations by exploiting differences in logit distributions between internal layers of large language models. Unlike traditional Contrastive Decoding, which utilizes differences in probability distributions between two separate models, DoLa compares token distributions derived from intermediate layers (early exit) and the final layer within a single model. Using Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD)[

11], DoLa dynamically identifies the layer with the greatest distributional shift and leverages this difference to prioritize the selection of factual tokens.

This method emphasizes factual knowledge already embedded in the model, thus enhancing factuality and reliability during generation without external knowledge or additional fine-tuning. When applied to large language models such as LLaMA[

12] or GPT-4[

13], DoLa has been reported to effectively produce accurate knowledge-based responses and reduce hallucinations. Evaluations across various benchmarks, including TruthfulQA[

14], FACTOR[

15], StrategyQA[

16], and GSM8K[

17], have shown significant improvements in factual reasoning performance, demonstrating the capability of DoLa to more effectively utilize the model’s internal information without additional computation or training.

3. Methodology

3.1. Background

Large-scale language models consist of an embedding layer,

N Transformer [

18] layers, and an affine layer for final prediction. The input token sequence is first converted into a vector sequence by the embedding layer. As these vectors pass through each Transformer layer, they progressively integrate semantic and contextual information. Let

be the output of the

i-th Transformer layer, and let

be the output of the final (

N-th) layer, which most strongly reflects the model’s learned knowledge. The affine layer then predicts the probability distribution for the next token as follows:

In this formulation, t denotes the current time step for which the token is to be predicted, with prediction based on tokens generated up to time step . The model leverages the previous tokens (i.e., all tokens preceding time step t) to predict the probability distribution for the next token .

The weight matrix projects the hidden vector into the vocabulary dimension. This projection results in a logit vector of dimension , which is subsequently transformed by the softmax function to yield the probability distribution across all possible tokens in the vocabulary.

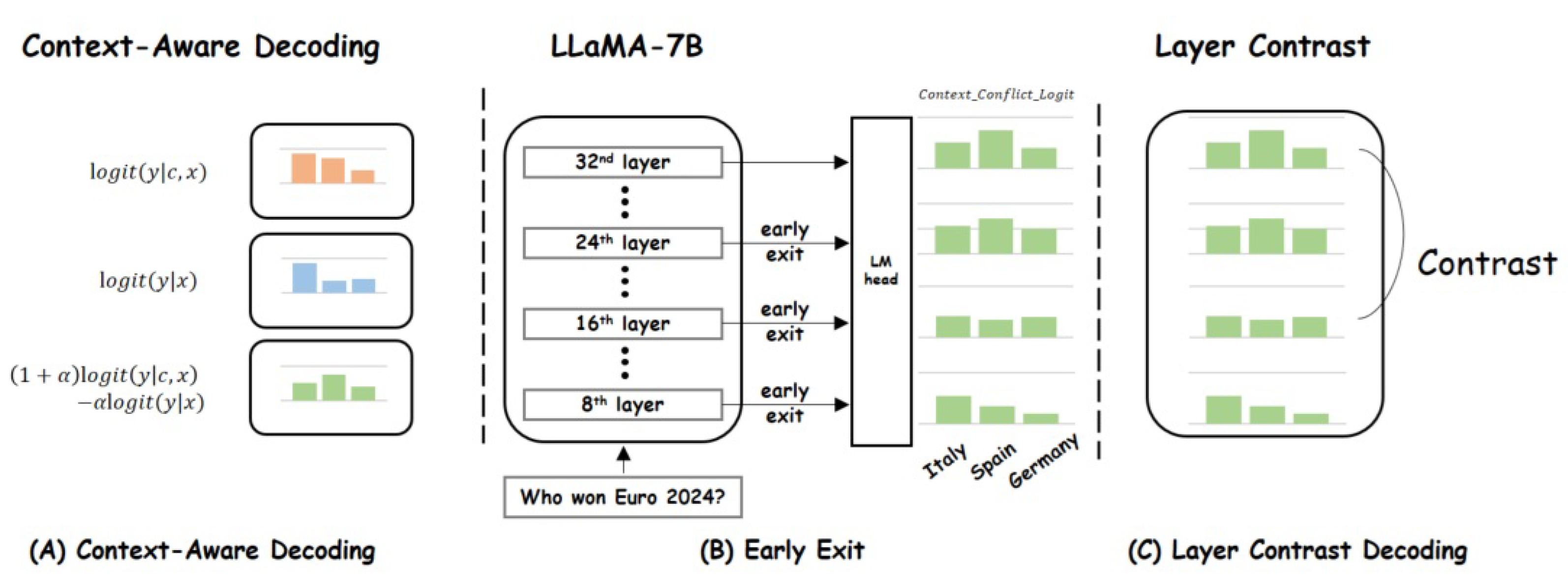

3.2. Contextual Conflicts with Pre-Trained Knowledge

Figure 1A illustrates the Contrast Decoding process for handling potential conflicts between context and pre-trained knowledge. Given a context

c and an input query

x, the language model generates an answer

y. Formally, this can be written as:

However, when provided context c falls outside the scope of the model’s pre-trained data or conflicts with previously learned knowledge, the model may inadequately incorporate c, defaulting excessively to outdated or conflicting pre-trained information. For example, if the question is “Which country most recently won the Euro?” and the context states “Spain won the 2024 UEFA European Championship,” the model might still produce the incorrect answer “Italy,” based on its older learned data.

To address this issue, we propose combining the probability distribution that reflects the given context with one that primarily relies on pre-trained knowledge, in a contrastive fashion. In the

i-th layer early exit, the adjusted distribution can be defined as:

where is a hyperparameter that modulates the importance of contextual information by adjusting the ratio between the probabilities with and without c. Through this contrastive adjustment, the approach seeks to reconcile pre-trained knowledge with newly provided context, thereby reducing erroneous predictions and improving overall accuracy and contextual alignment.

3.3. Early Exit Mechanisms for Improved Context Integration

Figure 1B illustrates how the LLaMA-7B model uses an intermediate layer’s hidden vector

to extract the next-token probability distribution in the form of

This approach aims to mitigate the issue of excessive reliance on pre-trained knowledge—which can lead to overlooking newly provided information—by identifying the point at which the newly given question or input has already been sufficiently incorporated within the model’s internal layers. In doing so, it helps control potential hallucinations or biases that may become more pronounced in the final layers.

Subsequently, by performing Contrast Decoding between the probability distributions obtained from the selected intermediate (i-th) layer and the final (N-th) layer, the model verifies whether the tokens, whose probabilities sharply increase in the higher layers, align with the information the model is better understanding while processing the given input. Early Exit is utilized to pinpoint the point at which the model sufficiently integrates the new information.

We want to use the Early Exit mechanism to focus on how the model has utilized the given information and which layers have successfully understood it. So, we conduct the context-conflict across all layers. From there, we perform Contrast Decoding by dynamic Layer selection to choose the most relevant layer that best represents the information the model has integrated.

3.4. Appropriate Layer Selection

Large language models, built on the Transformer architecture, process input information progressively through multiple layers. In this process, the lower layers typically capture relatively general patterns (e.g. syntactic features), while the upper layers focus on more nuanced semantic content (e.g., factual knowledge) [

19]. Using these layer-wise shifts in information, we propose a decoding strategy that highlights the newly provided context. Specifically, by analyzing output probability distributions at selected layers, adjustments are made whenever the model’s pre-trained knowledge neglects or misrepresents the given context.

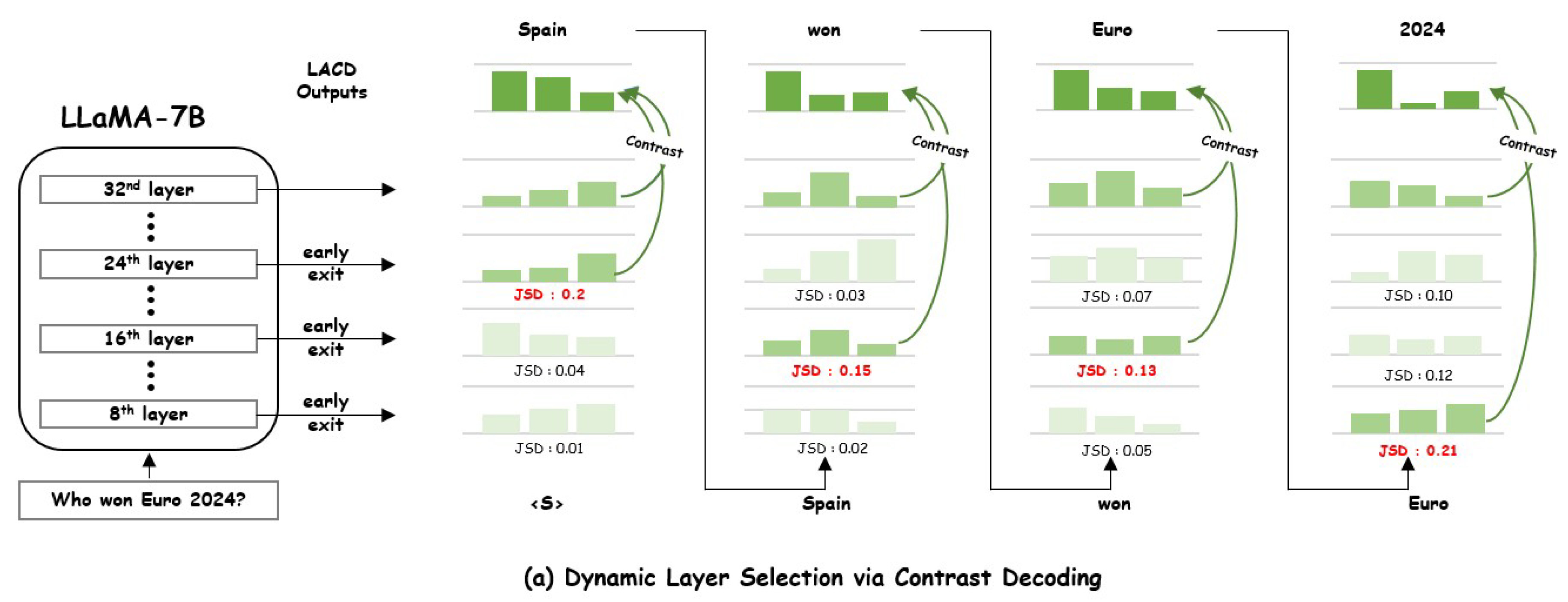

3.4.1. Dynamic Layer Selection

As illustrated in

Figure 2, Transformer-based language models produce their final output at the top-most layer, where semantic and pre-trained knowledge are synthesized to generate a response. By contrast, the lower layers contain comparatively simpler syntactic features or initial predictions and are therefore likely to be less influenced by newly provided context. To exploit this property, we compare the probability distributions of these lower layers with that of the final layer, then

dynamically select the intermediate layer whose distribution differs the most. Specifically, if a token has a low probability in a lower layer but a high probability in the final layer, it likely reflects a strong influence from newly provided context. By identifying such tokens—through comparison with the final layer—and leveraging them, we can generate more reliable outputs.

3.4.2. Comparison via JSD

To compare the output probability distributions of each candidate layer with that of the final layer, we employ the Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD). JSD is a symmetric measure of the difference between two probability distributions, defined as:

where

M is the average of the two distributions:

and

is the Kullback–Leibler Divergence [

11], a non-symmetric measure of distributional difference. In our framework, the

selected layer is the one whose distribution

P exhibits the highest JSD relative to the final-layer distribution

Q, indicating that context information has begun to be effectively integrated.

3.4.3. Contrast Decoding Between the Final Layer and the Selected Layer

Figure 2 also depicts how Contrast Decoding is applied between the final (

N-th) layer and the selected layer identified in the previous step. Specifically,

where

denotes the adjusted distribution from the final layer and

the adjusted distribution from the selected (intermediate) layer. By partially compensating the final layer’s distribution with

times the selected-layer distribution, this approach suppresses tokens overly influenced by pre-trained knowledge and preserves the newly incorporated context captured earlier. Finally, the next token is selected via

By choosing the intermediate layer that best reflects newly provided information and contrasting it with the final layer, the model more thoroughly retains contextual cues, mitigating hallucinations or biases that could arise from excessive reliance on pre-trained knowledge.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

In this paper, we evaluate our proposed method on three QA datasets: the distractor set of the HotPotQA [

20] validation dataset, SQuAD [

21]. HotPotQA is a large-scale question-answering (QA) dataset based on Wikipedia paragraphs, specifically designed to require multi-hop reasoning. We use the

distractor set to assess our model’s ability to handle complex contextual information and multi-step inference. The Stanford Question Answering Dataset (SQuAD) is a widely-used QA benchmark consisting of questions and answers derived from Wikipedia paragraphs, making it suitable for evaluating reading comprehension and single-paragraph answer extraction.

4.2. Experimental Setup

As our baseline model, we employ huggyllama/llama-7b, which has been pre-trained on a broad range of text data encompassing dialogue and question-answering tasks. Instead of conducting additional fine-tuning, we modify only the decoding process to observe changes in performance. For our experiments, we set the to 0.31 for HotPotQA and 0.7 for SQuAD, based on heuristic selection. We also use the 16th layer as the start layer and set the to 0.5. For evaluation metrics, we measure Exact Match (EM) and F1 scores, providing a comprehensive assessment of both the accuracy and overall quality of the answers generated by the model. All experiments were conducted on a system equipped with two NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs.

4.3. Prompt Construction and Few-Shot Examples

In our research, we perform the question-answering task using only few-shot prompts, without applying any additional fine-tuning to the pre-trained model. To this end, we prepare six question–answer examples in a demo-text format in advance. Sample questions (e.g., ’Is Mars called the Red Planet?’) mainly involve relatively simple general knowledge, while the corresponding answers (for example, ’yes’ or ’Mount Everest’) are clearly defined to guide the model effectively.

In

Table 1, we provide a concrete example of how prompts are constructed and how a few-shot setup can be presented. In particular, when contextual information is needed, it can be included in the format “Supporting information: ...” to encourage the model to leverage that additional context. Conversely, the “no-context” setting simply connects the preprepared few-shot examples with the question in a straightforward QA format; in this case, the model relies solely on its pre-trained knowledge and the demonstration examples to infer an answer. By preparing these two variations, we can compare the model’s output depending on whether additional context is provided or not.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Main Results

Table 2 presents the performance of various models on three QA datasets: HotPotQA, TriviaQA, and SQuAD, evaluated by Exact Match (EM) and F1 scores. Without contextual information, the baseline model performs poorly (e.g., 2.23% EM and 4.33% F1 on HotPotQA), indicating the limitations of relying solely on pre-trained knowledge. Incorporating additional context significantly enhances accuracy, with the baseline (w. context) reaching 38.84% EM and 52.91% F1 on HotPotQA.

Meanwhile, DoLa [2023] and CAD [2024] offer further improvements over the context-based baseline, demonstrating that fine-tuning the interplay between context and internal knowledge helps mitigate hallucinations. Both methods exceed 55% F1 on HotPotQA, reflecting their success in effectively leveraging context.

Our proposed method, LACD, achieves the highest scores across both datasets. On HotPotQA, LACD reaches 41.01% EM and 56.84% F1, outperforming the baseline by approximately 2.17% in EM and 3.93% in F1. On SQuAD, the improvement is even more substantial, with LACD achieving 31.62% EM and 48.60% F1, compared to the baseline’s 15.61% EM and 25.31% F1. These results highlight the effectiveness of LACD in integrating pre-trained knowledge with additional contextual cues across different QA tasks.

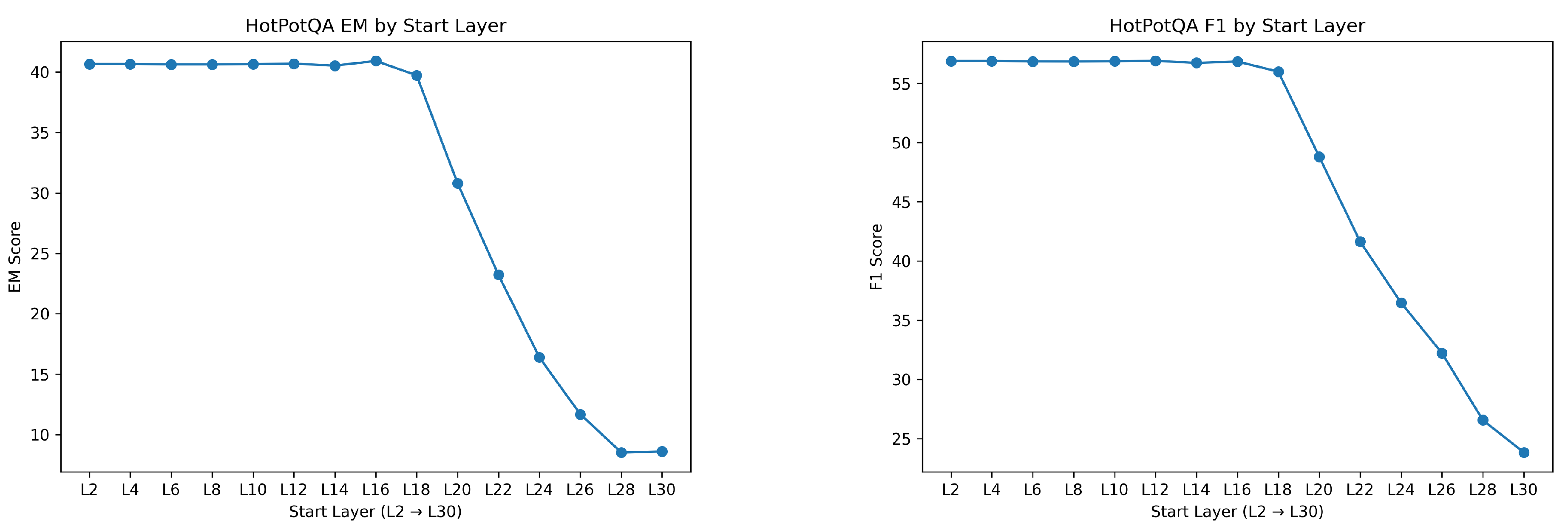

5.2. Experimental Results for Start Layer Selection

We introduce a start layer parameter to reduce the computational overhead of comparing all layers in the model. Specifically, instead of evaluating contrastive decoding at every layer, the model begins from a chosen start layer and only compares layers above that threshold. By varying this start layer from L2 to L30, we observe how performance shifts as the model leverages earlier vs. later layers.

Figure 3 illustrates the EM and F1 scores on HotPotQA for different start layers. The scores remain relatively stable until around the 18

th layer, after which a noticeable drop occurs. This trend is consistent with our prior observations that earlier layers capture vital contextual information and are thus pivotal for accurate question answering. Once the model begins contrastive decoding from too deep a layer (e.g., L20 or beyond), it effectively bypasses some of the crucial context alignment happening in earlier layers. Consequently, it relies on representations that are already more task- or semantics-focused, rather than continuing to refine the overarching contextual cues.

These findings align with our hypothesis that later Transformer layers, though informative semantically, do not necessarily reintroduce essential context for multi-hop QA. By starting at deeper layers, the model risks omitting the context-building steps, leading to a decrease in both EM and F1. In practical terms, setting the start layer too high reduces the effectiveness of contrastive decoding, suggesting an optimal trade-off between computation and performance around the mid-to-lower layers.

5.3. Experimental Results of the Contrast-Decoding Layer

In this experiment, we examine the effect of varying the contrast-decoding coefficient

on the performance of the LACD approach. The results for HotPotQA EM and HotPotQA F1 are summarized in

Table 3.

From the table, we observe that yields the best performance in terms of Exact Match (EM). Specifically, at , the EM score reaches 41.01, and the F1 score is 56.84. Notably, the EM score at this value of is the highest among all the values tested.

For , the EM score is slightly lower at 40.99, but the F1 score still improves to 56.81. Conversely, increasing to 0.60 results in a slight decrease in EM score to 40.96, though the F1 score peaks at 56.85.

At the extreme values of , both 0.30 and 0.70, we notice a slight degradation in performance. Specifically, the EM scores drop to 40.95 and 40.94, respectively, while F1 scores remain stable but do not surpass the performance observed at .

These findings suggest that provides the optimal balance between the final and intermediate layers, leading to the best performance in terms of both EM and F1 scores. When is too large or too small, the model struggles to effectively combine pre-trained knowledge with newly provided context, resulting in suboptimal performance.

5.4. Ablation Study

Layer selection strategy. To investigate the effectiveness of our proposed dynamic layer selection strategy, we conducted an ablation study comparing our Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) based approach against static layer selection at different depths of the model.

Table 4 presents the results of this comparison on the HotPotQA dataset.

The results clearly demonstrate that our dynamic layer selection strategy outperforms all static layer configurations. When examining static layer selection, we observe an interesting pattern: performance initially improves slightly from layer 12 (40.70% EM, 56.66% F1) to layer 16 (40.73% EM, 56.62% F1), suggesting that middle layers contain rich semantic representations useful for question answering. However, performance degrades dramatically as we move to deeper layers, with layer 20 showing significant F1 score degradation (37.70%), and layers 24 and 28 exhibiting catastrophic performance drops (23.98% and 17.21% F1, respectively).

This performance pattern confirms our hypothesis that different layers capture different aspects of knowledge and context representation. Shallow to middle layers tend to preserve more general semantic information while deeper layers may specialize in more abstract or task-specific features that, when used exclusively, can lead to over-specialization and reduced performance on complex QA tasks.

Our JSD-based dynamic layer selection approach, which achieves 41.01% EM and 56.84% F1, successfully addresses this limitation by adaptively choosing the most appropriate layer representations based on the specific input query and context. The dynamic selection enables the model to leverage the most relevant knowledge representation for each instance, effectively combining the strengths of different layers and avoiding the limitations of any single fixed layer.

The superiority of our approach becomes particularly evident when comparing against deeper layers (20, 24, and 28), where static selection performance drops precipitously. This suggests that our method effectively mitigates the potential negative impacts of less suitable layer representations while capitalizing on the most informative ones, resulting in more robust QA performance across diverse query types.

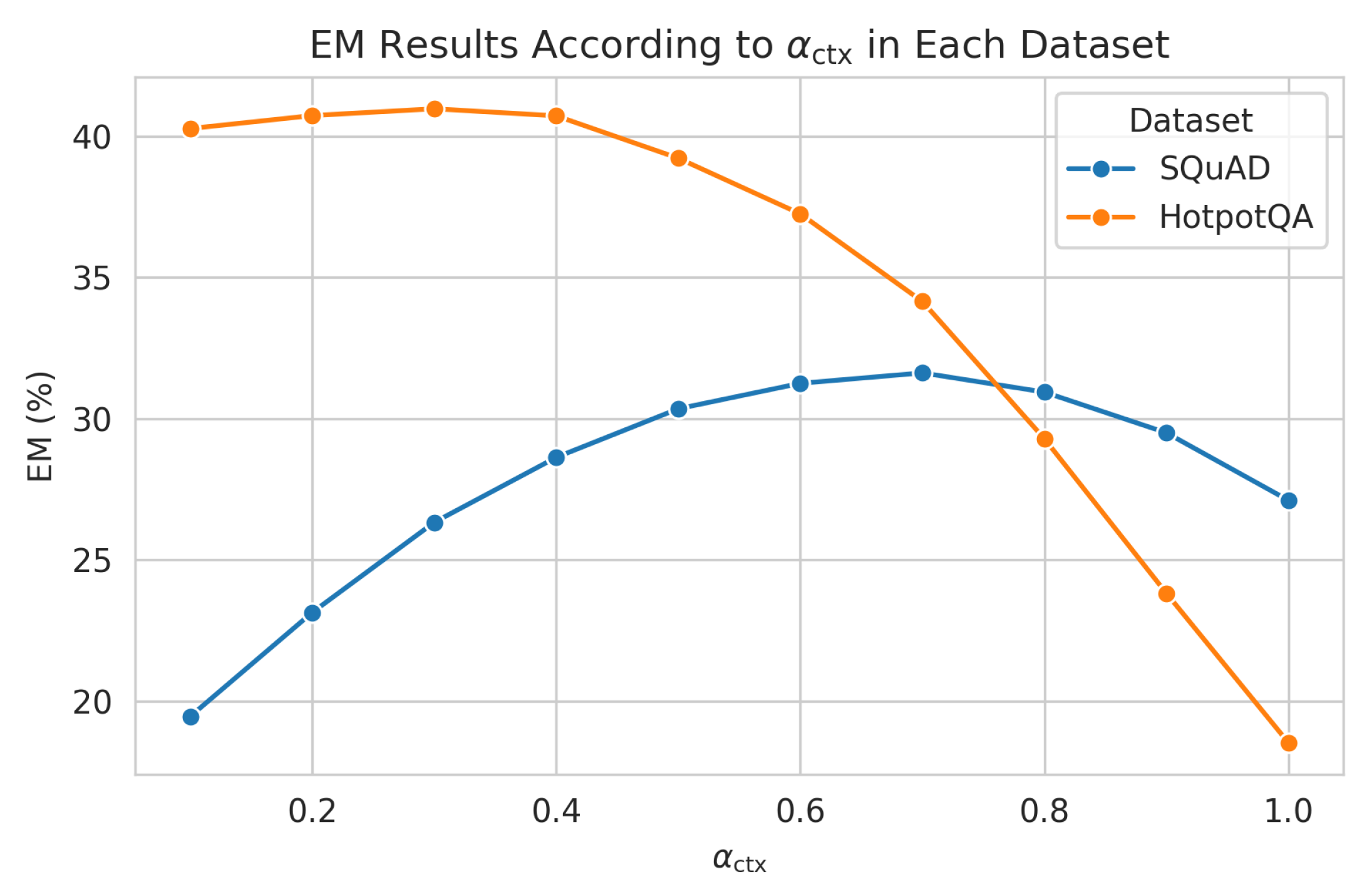

Figure 4.

Model performance across various settings in HotPotQA and SQuAD. Although a higher benefits SQuAD by leveraging concise context, a moderate or lower is more suitable for the broader context in HotPotQA.

Figure 4.

Model performance across various settings in HotPotQA and SQuAD. Although a higher benefits SQuAD by leveraging concise context, a moderate or lower is more suitable for the broader context in HotPotQA.

Effect of the Parameter on HotPotQA and SQuAD. We examined how the context weighting parameter affects model performance in each dataset. Our analysis showed that tuning leads to different outcomes: in one dataset, a higher tended to be more beneficial, whereas in the other dataset, a moderate or lower setting resulted in better overall performance. This finding suggests that each dataset’s unique characteristics require distinct parameter configurations, underscoring the importance of carefully calibrating for optimal results.

6. Discussion

Our experimental results demonstrate that incorporating contextual information and carefully adjusting decoding strategies can effectively reduce hallucinations, while improving both factual correctness and linguistic quality. The substantial performance gap between the “no-context” and “with-context” baselines on HotPotQA and SQuAD highlights the importance of newly provided context. This finding corroborates previous studies on knowledge conflicts and contextual deficits in large language models [

9,

10], reinforcing our working hypothesis that an LLM’s strong reliance on pre-trained knowledge must be suitably balanced with new context to prevent outdated or conflicting information from undermining generated responses.

Dynamic layer selection. Our experiments confirm that our JSD-based dynamic layer selection strategy significantly outperforms static selection approaches. The dramatic performance degradation with static selection at deeper layers (e.g., layers 20, 24, and 28) suggests that different layers capture distinct aspects of knowledge representation. As shown in our ablation study, shallow to middle layers (12–16) contain rich semantic representations beneficial for question answering, whereas exclusive reliance on deeper layers can lead to over-specialization and reduced performance. The start layer experiment further indicates that performance remains stable until around layer 18, after which scores drop noticeably. This pattern supports the conclusion that earlier layers capture crucial contextual information necessary for accurate responses, and omitting these layers in decoding diminishes the model’s overall effectiveness.

Contrast-decoding coefficients. The analysis of the contrast-decoding coefficient reveals that moderate values (around 0.5) generally achieve stronger EM and F1, implying that a balanced weighting of final-layer and lower-layer distributions is optimal. Excessively large may override newly provided context, while overly small risks neglecting valuable higher-level semantic knowledge embedded in later layers. Our observed performance peak at thus supports the notion that an appropriate “middle ground” is required to integrate context effectively without forfeiting essential pre-trained information.

Comparison with related approaches. Both CAD and DoLa, which mitigate hallucinations by leveraging pre-trained capabilities [

4,

5], showed modest gains over the context-inclusive baseline. By contrast, our proposed LACD framework demonstrated a more pronounced improvement, indicating that fine-grained control over how context is integrated—and how internal knowledge is adjusted—can further boost response accuracy. On HotPotQA, LACD reached 41.01% EM and 56.84% F1, surpassing both the baseline and other methods. On SQuAD, LACD achieved 31.62% EM and 48.60% F1, substantially higher than CAD’s 30.12% EM and 45.29% F1. These results underscore the value of explicitly modeling the interplay between new contextual cues and learned representations, rather than relying solely on end-to-end pre-trained or fine-tuned strategies.

Limitations and future directions. Although our experiments offer promising insights, they are limited to QA tasks focusing on HotPotQA and SQuAD. Future work could investigate the proposed methods across broader domains such as summarization or specialized fields like biomedicine, where hallucination risks have particularly significant implications. Another direction is to study how dynamic layer selection and contrast decoding can be extended to different model architectures (e.g., encoder–decoder or mixture-of-experts). Additionally, exploring automated ways to adapt or the start layer per query—based on uncertainty estimates or user feedback—might yield an even more robust and adaptive system.

Overall, our findings reinforce that hallucinations are best mitigated through balanced approaches that merge newly provided contextual cues with a model’s extensive but occasionally outdated or conflicting pre-trained knowledge. By employing selective layer usage and finely tuned contrast decoding, one can attain more reliable, context-appropriate generation in large language models.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed LACD, which integrates dynamic layer selection and contrast decoding to mitigate hallucinations in large language models. Our experiments reveal that excluding context severely degrades performance (e.g., EM dropping to around 2.22%), whereas incorporating additional information and selectively balancing pre-trained knowledge with newly provided context results in substantial gains in both accuracy and output quality.

Through variations in the contrast-decoding coefficient and adjustments to the starting layer, we demonstrated that strategically balancing focus between lower-layer and final-layer representations effectively mitigates hallucinated content and enhances exact-match (EM) performance.

In future work, we plan to extend this approach to broader tasks such as summarization, domain-specific applications (e.g., medical or legal contexts), and multi-hop reasoning, further validating its generality and robustness. Additionally, an automated mechanism to adapt and the start layer on a per-query basis—potentially guided by user feedback or uncertainty estimates—could offer more flexible, context-sensitive generation in real-world scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y. and G.K.; methodology, S.Y.; software, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, G.K; visualization, S.Y; supervision, G.K. and S.K.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (No. 2022R1A2C1005316) and in part by Gachon University research fund of 2024 (GCU-202400460001).

Data Availability Statement

References

- Tonmoy, S.; Zaman, S.; Jain, V.; Rani, A.; Rawte, V.; Chadha, A.; Das, A. A comprehensive survey of hallucination mitigation techniques in large language models. arXiv preprint 2024, 6. arXiv:2401.01313.

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837.

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 11809–11822.

- Shi, W.; Han, X.; Lewis, M.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Yih, W.t. Trusting your evidence: Hallucinate less with context-aware decoding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 2: Short Papers), 2024, pp. 783–791.

- Chuang, Y.S.; Xie, Y.; Luo, H.; Kim, Y.; Glass, J.; He, P. Dola: Decoding by contrasting layers improves factuality in large language models. arXiv preprint 2023. arXiv:2309.03883.

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B.; et al. A survey on hallucination in large language models: Principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 2025, 43, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Nallapati, R.; Zhou, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Xiang, B.; et al. Abstractive text summarization using sequence-to-sequence rnns and beyond. arXiv preprint 2016. arXiv:1602.06023.

- Narayan, S.; Cohen, S.B.; Lapata, M. Don’t give me the details, just the summary! topic-aware convolutional neural networks for extreme summarization. arXiv preprint 2018. arXiv:1808.08745.

- Longpre, S.; Perisetla, K.; Chen, A.; Ramesh, N.; DuBois, C.; Singh, S. Entity-based knowledge conflicts in question answering. arXiv preprint 2021. arXiv:2109.05052.

- Liu, A.; Liu, J. The MemoTrap Dataset. https://github.com/inverse-scaling/prize/blob/main/data-release/README.md, 2023.

- Lin, J. Divergence measures based on the Shannon entropy. IEEE Transactions on Information theory 1991, 37, 145–151. [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint 2023. arXiv:2302.13971.

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint 2023. arXiv:2303.08774.

- Lin, S.; Hilton, J.; Evans, O. Truthfulqa: Measuring how models mimic human falsehoods. arXiv preprint 2021. arXiv:2109.07958.

- Gao, L.; Biderman, S.; Black, S.; Golding, L.; Hoppe, T.; Foster, C.; Phang, J.; He, H.; Thite, A.; Nabeshima, N.; et al. The pile: An 800gb dataset of diverse text for language modeling. arXiv preprint 2020. arXiv:2101.00027.

- Geva, M.; Khashabi, D.; Segal, E.; Khot, T.; Roth, D.; Berant, J. Did aristotle use a laptop? a question answering benchmark with implicit reasoning strategies. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2021, 9, 346–361. [CrossRef]

- Cobbe, K.; Kosaraju, V.; Bavarian, M.; Chen, M.; Jun, H.; Kaiser, L.; Plappert, M.; Tworek, J.; Hilton, J.; Nakano, R.; et al. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint 2021. arXiv:2110.14168.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Tenney, I.; Das, D.; Pavlick, E. BERT rediscovers the classical NLP pipeline. arXiv preprint 2019. arXiv:1905.05950.

- Yang, Z.; Qi, P.; Zhang, S.; Bengio, Y.; Cohen, W.W.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Manning, C.D. HotpotQA: A dataset for diverse, explainable multi-hop question answering. arXiv preprint 2018. arXiv:1809.09600.

- Rajpurkar, P.; Zhang, J.; Lopyrev, K.; Liang, P. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv preprint 2016. arXiv:1606.05250.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).