1. Introduction

Neural networks, particularly large language models, have achieved remarkable performance across diverse tasks. However, they suffer from a critical flaw: hallucination—the generation of confident but false outputs [1]. Recent work attributes this to misaligned training incentives that reward guessing over acknowledging uncertainty [2].

We identify a more fundamental cause: models are architecturally constrained to select from a fixed vocabulary with no explicit mechanism for abstention. Given input tokens, the model must output a probability distribution over all vocabulary tokens. This forced choice creates an inescapable pressure to guess, even when the model has no basis for a correct answer.

Consider the loss function for next-token prediction:

where

y must be some token from vocabulary

. There is no option for “I don’t know” at the architectural level—the model must assign probability mass somewhere, incentivizing confident guessing on the most frequent patterns from training data.

We propose and test a simple solution: add a single ABSTAIN token to the vocabulary, giving models an explicit “opt-out” mechanism. Our insight is corruption augmentation: during training, we randomly corrupt inputs (e.g., by shuffling tokens in the context window) and map these corrupted inputs to the ABSTAIN token. This teaches the model that incoherent or unfamiliar inputs should trigger abstention. We show this strategy:

Reduces hallucinations

Does not cause a catastrophic loss of accuracy on known examples

Exhibits appropriate uncertainty on rare examples

Requires no architectural changes or post-hoc alignment

Generates training data automatically and scalably

Our work demonstrates that the solution to hallucinations is at least partially architectural: giving models the ability to abstain allows them to model uncertainty at the architectural level, can enable them to recognize unfamiliar contexts, domain shifts, and with appropriate training, adversarial attacks.

2. Background and Related Work

Hallucinations—plausible but false outputs—are a pervasive problem in modern neural networks [1]. Recent work has documented hallucinations across multiple domains: neural machine translation [3], image captioning [4], and large language models [5]. Recent work [2] argues that standard training and evaluation procedures reward guessing over acknowledging uncertainty. When evaluated solely on accuracy, models that guess confidently outperform those that abstain, even if the guesses are often wrong. Other work [6] proves that hallucinations may be computationally inevitable for any LLM used as a general problem solver.

The problem of selective prediction—choosing when to abstain—has been studied in classification [7,8]. Recent work applies these ideas to LLMs through post-training methods:

Calibration-based approaches. Some methods [9] use self-consistency to detect uncertainty. Others [10] sample multiple responses and measure agreement. Recent work [11] applies conformal prediction for principled abstention policies.

Training-based approaches. Some approaches [12] train models to abstain via multi-LLM collaboration. Others [13] introduce refusal-aware fine-tuning. Additional work [14] uses reinforcement learning to encourage appropriate refusal.

All existing approaches treat abstention as a behavioral pattern to be learned through post-training, requiring the model to generate natural language refusals (“I don’t know”, “I cannot answer”, etc.). These are multi-token sequences that must be learned as complex patterns.

We treat abstention as an architectural primitive by adding a single vocabulary token. This enables direct optimization during pretraining and provides a principled mechanism for uncertainty at the token-prediction level.

3. Method

3.1. The Abstain Token

We augment the vocabulary with a special

ABSTAIN token:

The model can now predict

ABSTAIN as a single token, providing an explicit “opt-out” from the forced-choice constraint. The standard cross-entropy loss applies unchanged:

3.2. Corruption Augmentation

The key challenge is: what training data should map to ABSTAIN? We cannot manually curate such examples at scale.

Our insight: Corrupt inputs during training and map them to ABSTAIN.

Algorithm: Corruption Augmentation

Input: Training data , corruption probability p

Output: Augmented data

for eachdo

if random() then

// e.g., shuffle, add noise

return

Corruption strategies. For sequence models, corruption can be implemented as:

Token shuffling: Randomly permute tokens in the context window

Token substitution: Replace tokens with random vocabulary items

Noise injection: Add random offsets to token embeddings

Corrupted inputs are semantically incoherent—there is no valid answer to gibberish input. By training on these examples, the model learns: when the input is unfamiliar or incoherent, predict ABSTAIN. Unlike manual curation, corruption augmentation:

Generates training data automatically

Scales to any dataset size

Requires no human annotation

Applies to any domain

Our corruption augmentation can be interpreted as a lightweight adversarial perturbation. By deliberately corrupting the context window—through shuffling or injecting incoherent tokens—we create inputs that are syntactically valid but semantically unanswerable. This is akin to an adversarial attack: the input is perturbed so that the model’s learned statistical regularities no longer apply, yet the model is still forced to generate an output. In such cases, conventional language models can hallucinate confidently. By instead mapping these perturbed contexts to a dedicated ABSTAIN token, we provide the model with an explicit mechanism to acknowledge uncertainty rather than produce spurious predictions.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

We used an LLM to design a controlled experiment to isolate the effect of the ABSTAIN token.

Task. Single-token prediction: given input token , predict output token . This is the atomic unit of next-token prediction in language models.

Dataset. Synthetic facts with controlled frequency:

Common (20 pairs, seen 100×): High-frequency knowledge

Rare (20 pairs, seen 1×): Singleton examples

Unseen (20 pairs, seen 0×): Never in training (hallucination test)

Model. Simple feedforward network: embedding layer → hidden layer (64 units) → output layer. Input vocabulary size 100, output vocabulary size 100 (baseline) or 101 (with ABSTAIN).

Training. Adam optimizer (lr=0.01), 50 epochs, batch size 1.

Corruption parameters. Probability (20% of examples corrupted), corruption via random token offset.

We also performed ablation studies where we varied the corruption probability

. Ablation studies were also repeated with different random seeds and by changing the numbers of common and rare pairs (increasing them both to 50).

Our evaluation metrics were:

Accuracy: Fraction of correct predictions (excluding abstentions)

Hallucination rate: Fraction of confident (prob ) but incorrect predictions

Abstention rate: Fraction of predictions that are ABSTAIN

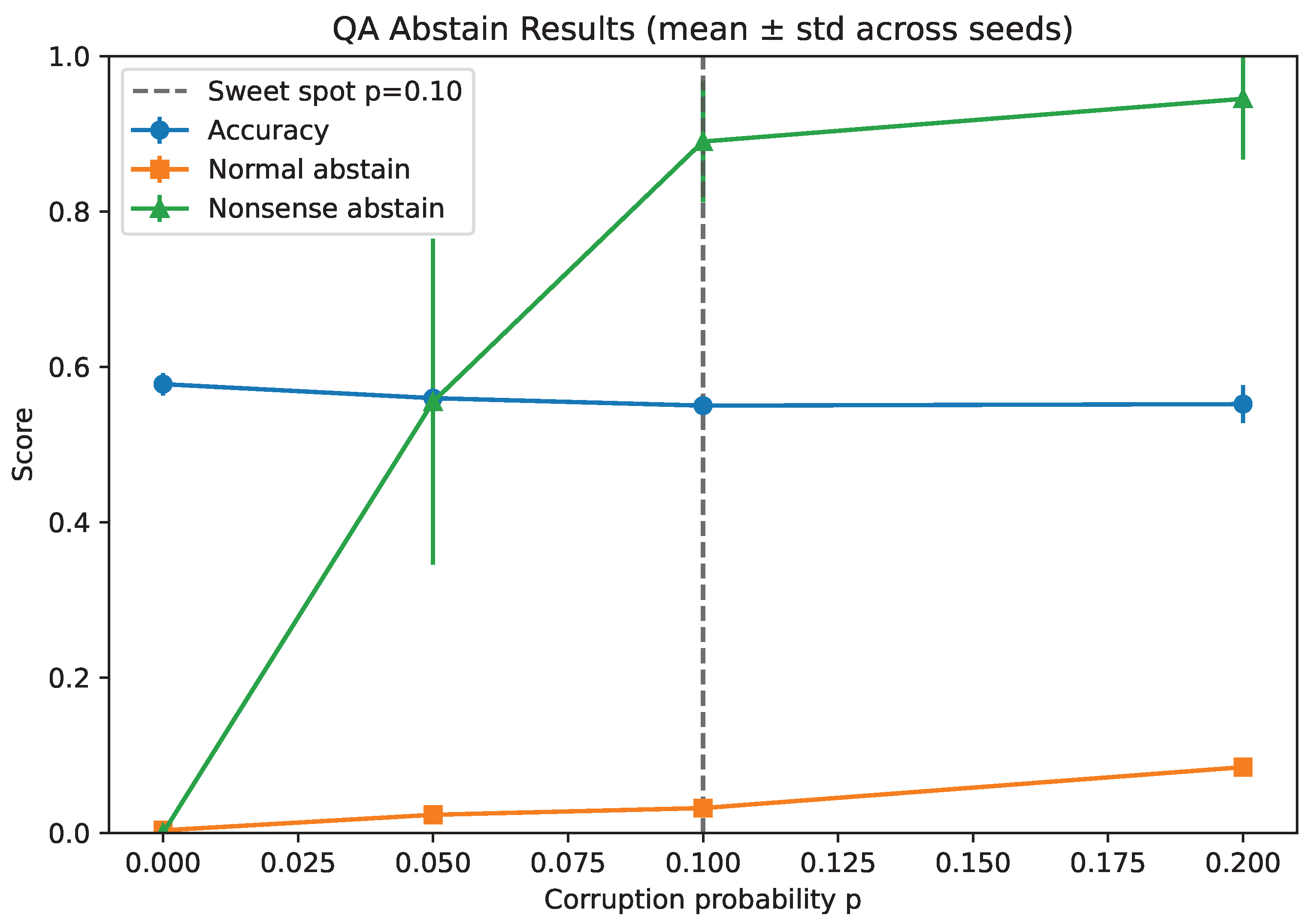

To test whether our method generalizes beyond the simple feedforward network setting, we applied the ABSTAIN token to a real large language model fine-tuned for question answering. We augmented the tokenizer of a distilled BERT model trained on the SQuAD v1.1 with the ABSTAIN token and retrained with corruption augmentation. For each corruption probability , a fraction p of training contexts were corrupted and mapped to the abstain token. Models were trained with three random seeds for robustness. We measured:

Accuracy on held-out SQuAD validation questions

Abstention rate on held-out SQuAD questions

Abstention rate on nonsense questions

4.2. Results

Table 1 shows our results with the simple feed-forward network. Introduction of the

ABSTAIN token with corruption augmentation eliminated hallucinations. Our key findings were:

Hallucinations eliminated. On unseen data, the hallucination rate dropped from 95% to 0% with the model abstaining rather than hallucinating.

Perfect performance maintained on common data. Accuracy remained 100% with 0% abstention on frequently-seen examples. The model confidently answered when it knew.

Appropriate uncertainty on rare data. For singletons (seen once), the model abstained 45% of the time. When it did answer (55%), it was always correct, demonstrating calibrated uncertainty.

-

Perfect calibration. The model exhibited ideal behavior:

High frequency → confident correct answers

Low frequency → selective abstention

No frequency → always abstain

Table 2 shows the results of our ablation studies. Higher corruption rates increased abstention on rare examples but did not affect common examples.

The results of ablation studies with different random seeds and by changing the numbers of common and rare pairs were consistent with the earlier investigations.

In our experiments with LLMs, baseline models (without corruption) achieved an accuracy of ∼0.58 but

with no significant abstention, even on nonsense questions (

Table 3). With

ABSTAIN training, and a corruption probability

, the model while having a 2.8% reduced accuracy abstained on ∼89% of nonsense questions representing a potential “sweet spot” between correctness and refusal (

Figure 1).

These results demonstrated that our method scaled to real QA tasks: the model preserved accuracy on genuine questions while abstaining on nonsense. Unlike the baseline, which always guessed, the abstain-augmented model knew when it did not know.

5. Discussion

The success of our approach reveals a fundamental insight: hallucinations are not primarily a training dynamics problem or an optimization problem—they are primarily an architectural constraint problem.

Standard models must choose from the vocabulary. The loss function offers no mechanism to express uncertainty. By adding ABSTAIN to the vocabulary, we give models an architectural primitive for uncertainty, enabling them to opt out when appropriate.

Corruption augmentation solves the data generation problem elegantly. The model learns: “coherent, familiar input → answer confidently; incoherent, unfamiliar input → abstain.” This pattern generalizes naturally to test-time uncertainty.

From another perspective, corruption augmentation can be viewed as a form of adversarial training. The perturbations we introduce resemble adversarial attacks in that they destabilize the model’s input space, producing contexts where no truthful answer exists. Standard language models respond to such perturbations with hallucinations, since they lack a mechanism to signal uncertainty. Our approach reframes this dynamic: we treat adversarially perturbed contexts not as opportunities for misprediction, but as signals to abstain, thereby converting adversarial vulnerability into calibrated refusal.

5.1. Comparison to Existing Approaches

Existing abstention methods work at the behavioral level, teaching models to generate multi-token refusals (“I don’t know”) through RLHF or fine-tuning. This has several limitations:

Multi-token sequences must be learned as complex patterns

Post-training required after pretraining completes

Expensive alignment with human feedback

Fragile to prompt variations

Our approach works at the architectural level:

Single token directly optimized in loss

During pretraining (or any training phase)

Automatic data generation via corruption

Robust architectural primitive

5.2. From Toy Models to LLMs

Our toy experiments demonstrated the principle in a fully controlled setting, helping eliminate hallucinations by adding a single abstention token. The question answering experiments confirm that the same principle scales to real LLMs. With only minor retraining, a distilled BERT model relatively preserved baseline accuracy on SQuAD while learning to abstain on incoherent inputs. At , the model achieved nearly 89% abstention on nonsense questions with no catastrophic loss of normal accuracy, highlighting the practical utility of our method for real-world applications.

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

Calibrating abstention rates. Our method appears to help eliminate hallucinations but may be conservative on rare data (45% abstention on singletons). Future work should explore:

Adaptive corruption rates based on data frequency

Multiple abstention tokens (“probably don’t know” vs “definitely don’t know”)

Confidence-weighted abstention during inference

Scaling to real LLMs. While our controlled experiment demonstrates the principle, deploying this on large language models requires:

Efficient corruption strategies for long contexts

Integration with existing tokenization schemes

Evaluation on real-world hallucination benchmarks

Corruption strategies. We used simple token offset corruption. More sophisticated strategies could include:

Context-aware shuffling that preserves some local structure

Adversarial corruption that maximally confuses the model

Curriculum learning: start with heavy corruption, gradually reduce

6. Conclusion

We demonstrate that hallucinations in neural networks stem from a fundamental architectural constraint: models must always select from a fixed vocabulary with no mechanism for abstention. Adding a single ABSTAIN token to the vocabulary, combined with corruption augmentation for automatic data generation, helped eliminate hallucinations with appropriate behaviour on known or rare examples.

Our approach is simple, scalable, and requires no architectural changes beyond adding one token. The key insight is that corruption augmentation automatically generates training data that teaches models when to abstain.

This work suggests a broader principle: rather than treating undesirable behaviors as training dynamics problems to be fixed post-hoc, we should consider whether architectural primitives can address them directly. Just as attention mechanisms solved sequence modeling, a single abstention token may be all we need to reduce hallucinations.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

An LLM was used in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Ziwei Ji, Nayeon Lee, Rita Frieske, Tiezheng Yu, Dan Su, Yan Xu, Etsuko Ishii, Yejin Bang, Andrea Madotto, and Pascale Fung. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–38.

- Adam Tauman Kalai, Ofir Nachum, Santosh S. Vempala, and Edwin Zhang. Why language models hallucinate. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.04664, 2025; arXiv:2509.04664.

- Vikas Raunak and Matt Post. The curious case of hallucinations in neural machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.06683, 2021; arXiv:2104.06683.

- Anna Rohrbach, Lisa Anne Hendricks, Kaylee Burns, Trevor Darrell, and Kate Saenko. Object hallucination in image captioning. EMNLP, 2018.

- OpenAI. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023; arXiv:2303.08774.

- Ziwei Xu, Sanjay Jain, and Mohan Kankanhalli. Hallucination is inevitable: An innate limitation of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.11817, 2024; arXiv:2401.11817.

- Chi-Keung Chow. On optimum recognition error and reject tradeoff. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1970, 16, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Yonatan Geifman and Ran El-Yaniv. Selective classification for deep neural networks. NeurIPS, 2017.

- Lorenz Kuhn, Yarin Gal, and Sebastian Farquhar. Semantic uncertainty: Linguistic invariances for uncertainty estimation in natural language generation. ICLR, 2023.

- Potsawee Manakul, Adian Liusie, and Mark JF Gales. SelfCheckGPT: Zero-resource black-box hallucination detection for generative large language models. EMNLP, 2023.

- Songhua Lin, Aditi Raghunathan, Percy Liang. Mitigating LLM hallucinations via conformal abstention. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01563, 2024; arXiv:2405.01563.

- Shangbin Feng, Weijia Shi, Yike Wang, Wenxuan Ding, Vidhisha Balachandran, Yulia Tsvetkov. Don’t hallucinate, abstain: Identifying LLM knowledge gaps via multi-LLM collaboration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.00367, 2024; arXiv:2402.00367.

- Yiming Zhang, Jianglue Wang, Qinying Chen, Zhihan Wang, Jiang Bian, and David Wipf. R-tuning: Teaching large language models to refuse unknown questions. arXiv preprint, 2024.

- Saurav Kadavath, Tom Conerly, Amanda Askell, Tom Henighan, Dawn Drain, Ethan Perez, Nicholas Schiefer, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Nova DasSarma, Eli Tran-Johnson, et al. Language models (mostly) know what they know. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.05221, 2022; arXiv:2207.05221.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).