1. Introduction

Cancer cells, characterized by rapid proliferation, must adapt their metabolism to meet high energy and biosynthetic demands. Beyond simply coping with nutrient scarcity in the tumor microenvironment, metabolic intermediates also function as critical signaling molecules that drive oncogenesis. This metabolic reprogramming represents a promising therapeutic target. Amino acids, as fundamental cellular building blocks, have long been a focus of cancer research. Among these, branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) are particularly intriguing because they are essential and cannot be synthesized by mammalian cells. Over the past decades, studies have documented altered BCAA levels—both within cells and systemically—in cancer compared to normal tissues. These alterations are often accompanied by changes in the expression of key enzymes involved in BCAA catabolism and corresponding shifts in cellular signaling.

This review provides a comprehensive summary of how different cancers modulate BCAA catabolism. We discuss alterations in gene expression along the BCAA metabolic pathway, the resulting changes in metabolite profiles, and the impact on interconnected metabolic pathways. Importantly, we explore potential therapeutic targets within the BCAA catabolism pathway, including currently available inhibitors. This review highlights new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer treatment by elucidating these metabolic changes.

2. BCAA Catabolism

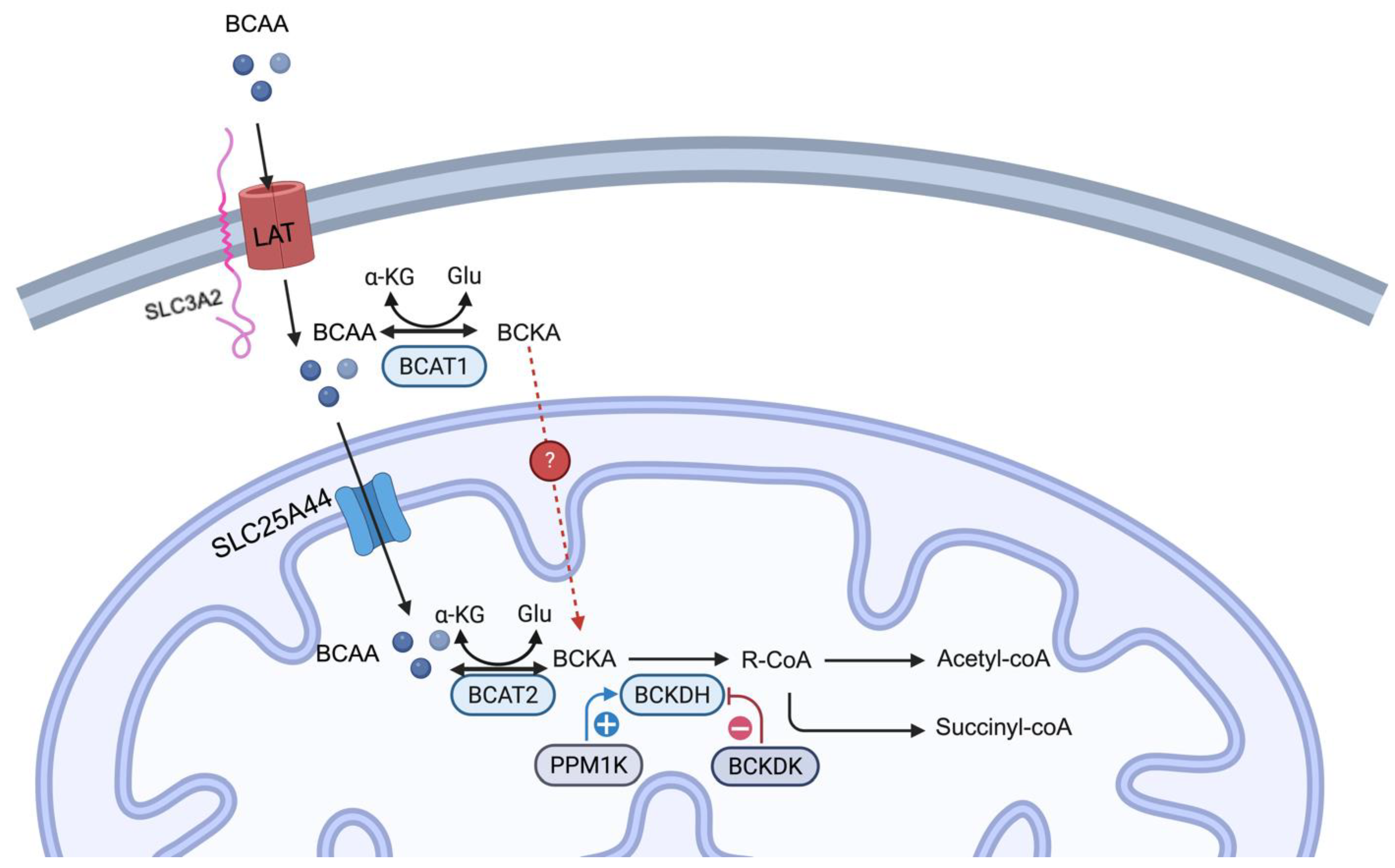

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), leucine, isoleucine, and valine are essential amino acids, and their primary source is the diet. In mammalian cells, BCAA uptake is facilitated by either LAT1 or LAT2 and SLC3A2, ensuring an efficient influx of BCAAs across the plasma membrane (

Figure 1)[

1]. The catabolism of BCAA starts with transamination to their corresponding branched-chain keto acids (BCKA; i.e., isoleucine to α-keto-β-methylvalerate; valine to α-ketoisovalerate; leucine to α-ketoisocaproate). BCAT1 (cytosolic) and BCAT2 (mitochondria) carry out this process in humans and mice. The expression of the BCAT1 is limited to the brain, kidney, and ovarian tissues. Whereas BCAT2 is more ubiquitously expressed except in the liver [

2]. BCAT2 function requires the mitochondrial BCAA transporter SLC25A44, which imports BCAA into the mitochondrial matrix[

3]. During BCAT deamination, the amino group is donated to a-ketoglutarate to form glutamate. Then, these BCKAs were irreversibly decarboxylated in mitochondria by the BCKDH complex. The knowledge gap remains regarding how BCKAs from BCAT1 catalysis in the cytosol are effluxed into the mitochondria. The BCKDH complex is a multi-subunit enzyme complex consisting of E1 (encoded by BCKDHA and BCKDHB genes), E2 (encoded by the DBT gene), and E3 (encoded by the DLD gene) subunits[

4]. The phosphorylation state of the E1 subunits dictates the activity of the BCKDH complex, with dephosphorylation by PPM1K (also known as PP2Cm) and phosphorylation by BCKDK of E1 subunits leading to its activation and deactivation[

5]. Subsequent enzymes in this pathway, including propionyl-CoA carboxylase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, produce the end product of BCAAs, including succinyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA, which can be used in another metabolism pathway as the substrate, such as gluconeogenesis, ketogenesis, and fatty acid synthesis (Ref).

Mutations in multiple catalytic enzymes in BCAA catabolism cause genetic disease. For example, a mutation in genes of the BCKDH complex leads to maple syrup urine disease, which is characterized by the inability to metabolize BCKAs. The mutation in propionyl-CoA carboxylase and methymalonyl-CoA mutase results in propionic or methylmalonic aciduria, respectively. Deficiency in Vitamin B12 also causes methylmalonic aciduria due to its requirement for the conversion of methylmalonic acid to succinyl-CoA. Thus, in healthy human beings, these metabolic processes maintain BCAA homeostasis[

6].

3. Reprogramming BCAA Metabolism in Cancer

Mutations in the BCAA catabolism genes could lead to genetic disorders; recent studies have identified that cancer cells require more carbon and nitrogen sources to meet proliferation, biosynthesis, and energy needs. Multiple cancers reprogrammed BCAA catabolism to adapt to these needs. This includes modulation of the gene expression change, transition efficiency, enzyme stability, and enzyme-substrate preferences. In this section, we summarize the aspects of BCAA catabolism in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC), Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), breast cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), leukemia, Glioblastoma, and other cell types in the tumor microenvironment.

3.1. PDAC

In PDAC, the intracellular BCAA levels are controlled by the BCAA transporter and are one of the essential aspects of determining BCAA catabolism in PDAC pathogenesis. Multiple studies have observed an elevated BCAA intake with an increased expression of BCAA transporters[

7,

8]. Without increased expression of BCAA transporter, BCAA catabolism likely does not play a role in the PDAC pathogenesis[

9].

BCAT2 is the first enzyme in the BCAA catabolism pathway; its mRNA and protein are overexpressed in PDAC [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Ablation or inhibition of BCAT2 reduces PDAC cell proliferation [

10]. Recent studies also explored the BCAT2 protein stability in PDAC. Li et al. identified that USP1 deubiquitylates BCAT2 at K229 under high BCAAs levels, and Lei et al. discovered that acetylation at K44 leads to BCAT2 degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway under BCAA deprivation conditions [

10,

11]. This evidence puts BCAT2 under the spotlight in PDAC pathogenesis. In BCAA catabolism, BCAT performs the reversible step that converts BCAAs to BCKAs. Manipulation of subsequent steps of enzyme expression levels, especially the step that commits BCKAs to BCAA catabolism (e.g., BCKDH complex), and understanding their roles in the pathogenesis of PDAC is paramount. Knocking down BCKDHA, a subunit of the BCKDH complex, in PDAC cells also substantially reduces proliferation, suggesting the importance of committing to BCAA catabolism in PDAC pathogenesis [

7]. Similarly, Zhu et al. showed that BCKAs, produced by cancer-associated fibroblasts from BCAAs in the PDAC environment, are the preferred substrate for PDAC cells [

12]. These studies suggest that the BCAAs and the oxidation of BCAAs are also important to PDAC progression.

3.2. HCC

The exploration of the role of BCAA in HCC started in the early 2000s. In these studies, authors have shown that BCAA supplementation benefits HCC patients or rodents receiving radiofrequency ablation [

13,

14,

15]. In vitro studies have also demonstrated that BCAA supplementation leads to multiple mechanisms that mediate autophagy and apoptosis [

16,

17]. However, results from recent studies say otherwise. Clinical studies revealed that BCAA supplementation elevates serum albumin levels and supports remaining liver function [

18]. Furthermore, with a more comprehensive meta-analysis, two studies using multiple cohorts’ data from currently available literature showed no HCC prevention effect from BCAA supplementation [

19,

20]. These studies have not focused on the effect of BCAA catabolism itself on HCC pathogenesis. In preclinical studies, the results are not homogeneous. Kim et al. showed that LAT1 is the most significantly increased amino acid transporter in HCC [

21]. Genetic ablation of LAT1 leads to decreased liver cancer growth and diminished mTORC1 signaling [

21]. The study from Ericksen et al. showed significant overexpression of BCAT1 and BCAT2 in HCC tumors compared to the normal tissue. However, other enzymes in BCAA catabolism are either downregulated or have reduced activity (e.g., BCKDH), which leads to the accumulation of BCAA and mTORC1 activation. Interestingly, reducing BCAA supplementation and increasing BCAA catabolism are associated with better outcomes in this study [

22]. Conversely, BCAA catabolism is active and correlated with increased tumorigenesis through PPM1K-mediated phosphorylation of BCKDH under glutamine starvation [

23].

From the current literature, no conclusive agreement can be reached, possibly due to the complex etiology that leads to the distinct metabolism of HCC. Consequently, it impacts BCAA catabolism in a context-dependent manner. Further studies with more stringent categorization in clinical studies and different models of HCC in mimicking different etiologies of HCC would facilitate deciphering context-dependent BCAA catabolism in HCC.

3.3. Breast Cancer

The association between circulation/tissue BCAA levels and breast cancer risk is not established [

24,

25]. Multiple studies examining BCAA catabolism have reached similar results, such as breast cancer having high BCAA catabolism at the reversible step controlled by BCAT [

26,

27,

28]. BCAT1 overexpression is one of the common understandings in the literature [

26,

28,

29]. Inhibiting BCAT1 by Eupalinolide B or the anti-cancer drug doxycycline reduces intracellular BCAAs or BCKAs levels, respectively [

26,

29]. Sadly, direct evidence using labeled BCAA to trace the fate of BCAAs in breast cancer is lacking. However, diminished BCAA catabolism genes were observed [

26]. With the inhibition of BCAT1 and doxycycline usage, the growth of breast cancer cells is retarded [

26,

29]. To be noted, BCKDK has been associated with cancer risks and theoretically negatively regulates BCAA catabolism [

26,

30,

31]. First, BCKDK is negatively associated with a low recurrence-free survival rate [

31], and genetic ablation or inhibiting BCKDK increases paclitaxel effects and increases cell death in breast cancer cells [

26,

30]. The BCKDK effect on BCAA catabolism has been explored less, with no metabolomic data available. From this evidence, though direct evidence is still needed to measure the BCAA catabolism metabolites, breast cancer cells likely have a decreased BCAA catabolism after the committing step.

3.4. NSCLC

Clinical and preclinical data have shown increased intracellular BCAAs levels in NSCLC [

9,

32,

33,

34]. This observation results from an adaptive change in BCAAs catabolism in NSCLC, including increased LAT1, BCAT1, and BCAT2 [

9,

33,

35]. Importantly, brain metastasis NSCLC BCAT1 expression is negatively associated with survival rate [

33]. A discrepancy exists regarding BCAAs levels when knocking down BCAT1 in NSCLC or brain metastasized NSCLC cells, with Zhang et al. showing no change and Mao et al. showing an increase in BCAAs levels [

33,

35]. This may be explained by the malignancy level associated with BCAT1 expression [

33]. Like breast cancer, the increased BCKDK and reduced BCKDHA further retain the BCAAs in the NSCLC cells [

32,

34]. Genetic deletion of BCKDK increases apoptosis and reduces proliferation [

32,

34]. Interestingly, the citrate decrease in NSCLC cells due to BCKDK increased ATP-citrate lyase activity (conversion of citrate to acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate), which leads to the question of whether increased BCKDK also increases reamination of BCKAs by reamination of oxaloacetate to aspartate; nevertheless, the data is not available[

32]. To answer this question, further studies are necessary.

3.5. Leukemia

It is widely accepted that intracellular BCAAs are increased in leukemia [

36,

37,

38]. However, conflicting results exist regarding the flow of BCAAs. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells of Ezh2

−/− NRas

G12D mice, the overexpression of BCAT1 is responsible for converting BCKAs back to BCAAs [

39]. Kikushige et al. showed that AML cells commit BCAAs to irreversible steps of BCAA catabolism and channel the final products to the TCA cycle[

38]. Nevertheless, the literature agrees that BCAT1 is overexpressed in AML cells [

36,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Studies have shown multiple ways in which leukemia cells maintain abnormal elevation of BCAT1 expression to meet their needs. Kikushige et al. demonstrated that the PRC2, an important epigenetic regulator for AML stemness, is responsible for the aberrant BCAT1 expression and reprogrammed BCAA catabolism [

38]. Loss of EZH2 in PRC2 complex, also driving BCAT1 overexpression [

39]. Meanwhile, N

6-methyladenosine METTL16 and MSI2 can stabilize BCAT1 mRNA to maintain BCAT1 translation in AML cells [

43,

44]. Notably, BCAT1 expression has been associated with the outcome of leukemia [

41,

44]. Studies have shown that knockdown or inhibition of BCAT1 leads to reduced survival and proliferation [

40,

42,

45,

46]. Limited studies have explored the expression of other enzymes and their activity in BCAA catabolism in leukemia. Liu et al. have demonstrated that PPM1K is critical for BCAA catabolism [

37]. However, no metabolites after the commitment step of BCAA catabolism have been quantified in this study [

37]. Studies are still needed to clarify whether the intracellular BCAAs, the catabolism of BCAAs, or both are required for leukemia progression.

3.6. Glioblastoma

Most literature shows increased BCAA catabolism in glioblastoma [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Multiple studies focus on the reversible step that BCAT controls due to BCAT1 overexpression [

48,

51,

52]. For example, HIF1a/2a is important to maintain BCAT1 expression [

51]in hypoxic conditions. Deletion of both HIF1a/2a decreases BCAT1 expression [

51]. Studies have demonstrated that ⍺-ketoglutarate, an important metabolite, can modulate DNA methylation, and its level regulates BCAT1 expression [

47,

48]. Intriguingly, BCKDK, originally the kinase that phosphorylates BCKDH to reduce its activity, has been shown to prevent BCAT1 protein degradation by phosphorylation on its S5, S9, and T312 sites [

53]. Like all the other cancers, deletion, inhibition, or increased degradation of BCAT1 increases apoptosis and decreases proliferation [

47,

48,

51,

52,

53]. Less research has been conducted on the latter step of the BCAA catabolism in glioblastoma. Suh et al. observed increased radio label isotope incorporation into lactate and glutamate in glioblastoma from rats perfused with U-

13C leucine, suggesting commitment of BCAAs into later irreversible steps [

49]. Indirect evidence that knocking down the leucine oxidation gene HMGCL leads to cell death [

54] suggests that the oxidation of BCKAs is also responsible for glioblastoma pathogenesis. BCKDK, resembling other cancers, is associated with glioblastoma progression. Knocking it out leads to a reduction in the proliferation of glioblastoma [

55]. However, increased BCKDK leads to less BCKAs oxidation, which conflicts with the increased isotope integration in glioblastoma. Further studies are needed to clarify BCKAs oxidation levels in glioblastoma.

3.7. Other Cancers

Though literature is less abundant, BCAA catabolism plays a role in gastric cancer and melanoma tumorigenesis. In gastric cancer, mutation of BCAT1

E61A was identified in gastric cancer patients; this mutation leads to significantly elevated catalytic activity from BCAAs to BCKAs, while the BCKAs to BCAAs catalyzing ability remains similar, suggesting increased BCAA catabolism[

56]. Such increased BCAA catabolism eventually leads to elevated tumor genesis[

56]. In melanoma, BCAT2 and BCKDHA are found to be overexpressed. Inhibition or suppression of the expression of BCAT2 or BCKDHA reduces colony formation, proliferation, and increases apoptosis[

57,

58].

4. Metabolism of BCAAs in Various Cell Types within the Tumor Microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment comprises multiple cell types, including immune cells, fibroblasts, and others [

59]. These cells will also respond to elevated branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) within tumor tissue, thereby influencing cancer progression. The PDAC cells can take advantage of the BCKAs, the preferred substrate for PDAC cells, metabolized by cancer-associated fibroblasts, and fuel PDAC cell proliferation[

12]. The reprogrammed BCAA catabolism in the cancer cells can also affect the tumor microenvironment’s immunity. As previously mentioned, BCAA levels are increased in NSCLC, and T cells can take advantage of these elevated BCAA levels and increase the CD8

+ population, leading to higher anti-tumor immunity [

60]. Macrophages in glioblastoma can uptake the BCKAs from their environment and subsequently re-aminate to BCAAs, suppressing the phagocytosis of the macrophages [

50].

Overall, most research regarding reprogrammed BCAA catabolism in cancer focuses on the first steps of the BCAA catabolism. As this is a reversible reaction, it is still unclear whether the forward reaction (e.g., BCAAs to BCKAs), reverse reaction (e.g., BCKAs to BCAAs), the metabolic intermediates (e.g., α-ketoglutarate and glutamate), and signaling induced by these intermediates, or all of them, are necessary for different cancer progression. Also, overexpression of different isoforms of BCAT likely results in different metabolic fates of BCAAs owing to their difference in subcellular localization, with BCAT1 overexpression associated with BCAAs accumulation, subsequently activating mTOR, and BCAT2 overexpression catabolizing BCAAs and channeling into other pathways. This situation is further complicated by the fuel preference difference between cancer types and, under certain nutrient deprivations, such as a lack of certain metabolites affected by BCAA catabolism in specific situations. Nevertheless, literature agrees upon BCAT expression and reduces BCAT activity or expression retard cancer progression. The latter, irreversible steps are less explored, with HCC, breast cancer, and NSCLC likely having less BCKAs oxidation and PDAC having increased BCKAs oxidation, likely due to overexpression of different isoforms of BCAT in different cancers. Questions remain, such as whether there is a channel for BCKAs to import into mitochondria. If yes, what is the expression pattern in different cancers? BCKDK, due to its positive association with multiple cancers, its increased expression likely leads to decreased BCKAs oxidation, which has been suggested in NSCLC. However, evidence supports that BCKDK can affect other enzyme functions to modulate BCAA metabolism.

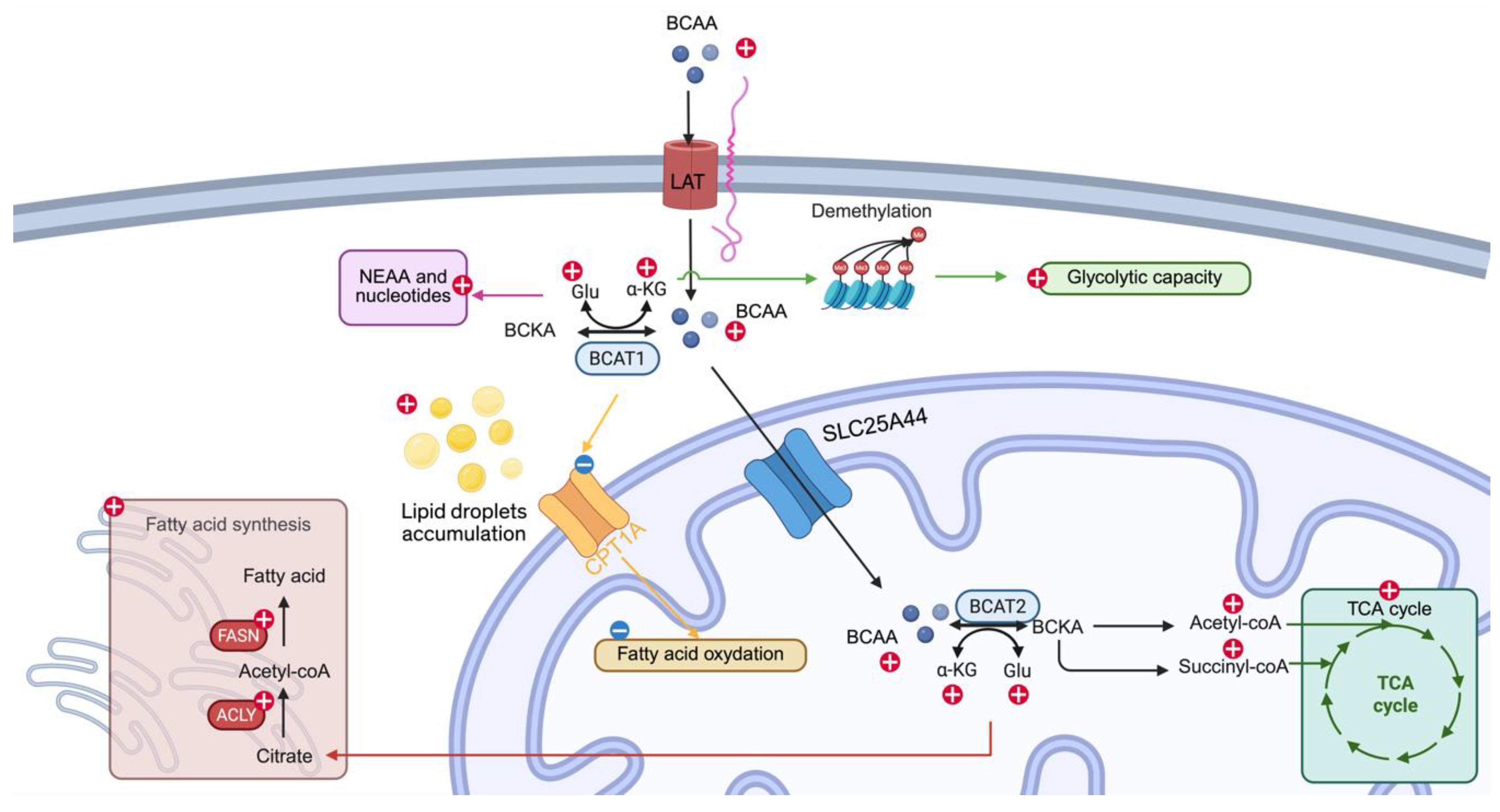

5. Impact of Altered Branched-Chain Amino Acid Catabolism on Additional Metabolic Pathways

In the previous section, a summary of the aberrant expression of the BCAT or BCKDK gene leads to the reprogrammed BCAA catabolism, as intermediates of BCAA catabolism can be used by other metabolic pathways (

Figure 2). Literature has provided evidence that BCAA catabolism affects another metabolic pathway. In this section, we summarize these and discuss this evidence.

5.1. Glucose Metabolism

From the current literature, most studies have agreed that increased BCAA catabolism in different cancers will increase either glycolysis or mitochondrial respiration; in some cancers, it leads to both [

8,

26,

28,

32,

35,

37,

38,

43,

52,

55]. In glioblastoma, Lu et al. demonstrated that mitochondrial potential is disrupted by BCAT1 inhibitor, leading to reduced reduction of oxidative phosphorylation measured by metabolomics [

52]. Knocking down BCKDK also reaches a similar result, significantly reducing multiple TCA and glycolysis intermediates[

55]. In leukemia, knocking down PPM1K, essential for reprogrammed BCAA catabolism, leads to significantly reduced glycolytic and oxidative phosphorylation capacity [

37]. Han et al. also showed that BCAA catabolism contributes to the increased TCA cycle metabolites and oxidative phosphorylation [

38,

43]. Knocking down N

6-methyladenosine (m

6A) METTL16, required for increased BCAA catabolism, leads to significantly reduced enrichment of isotope in citrate and malate[

12,

43]. In breast cancer, though there is a lack of direct evidence that BCAA catabolism contributes to the TCA cycle metabolites. Inhibiting the key enzymes BCAT1 and BCKDK reduces basal and maximum respiration and ATP production [

26,

28,

29]. Gene expression analysis showed increased BCAA catabolism leads to increased mitochondrial biogenesis genes [

28]. In NSCLC, proteomics of TKI-resistant cells reveals the enrichment of glycolytic pathway proteins[

35]. TKI-resistant cells and BCKDK overexpression cells[

32,

35]also increase the maximum glycolytic capacity. However, a discrepancy exists between the basal glycolytic levels[

32,

35]. In PDAC, increased maximum glycolytic capacity, basal and maximum phosphorylation have been observed in BCAT2 overexpression cells[

8]. BCAA catabolism metabolites integration into the TCA cycle by isotope tracing is also observed[

8,

12,

43].

The mechanism of glucose metabolism modification by reprogrammed BCAA catabolism is less explored, with most studies demonstrating this with observation. One of the mechanisms for glycolytic-related change is increased ⍺ketoglutarate by BCAA catabolism, which consequently leads to demethylation and increases glycolytic activity. For oxidative phosphorylation, it is likely due to the direct contribution of metabolites from BCAA catabolism to the TCA cycle [

12,

43]. Further studies are required to understand the link between glucose metabolism and BCAA catabolism.

5.2. Nonessential Amino Acid and Nucleotide Synthesis

Nonessential amino acid and nucleotide synthesis are building blocks for cancer proliferation, and reprogrammed BCAA catabolism leads to a significant increase in the production of glutamate, subsequently other nonessential amino acids and nucleotides, the byproduct of transamination of BCAAs [

8,

9,

23,

43]. The BCAT2 overexpression in PDAC and METTL16-induced elevated BCAA catabolism in leukemia cells leads to N

15 isotope from BCAAs integrated into the nonessential amino acids and nucleotides, suggesting BCAAs’ contribution to the nonessential amino acid and nucleotide synthesis[

8,

43]. A similar result was observed in HCC cells with glutamate starvation, but no difference was observed between normal and glucose starvation conditions [

23]. This effect also holds in the in vivo NSCLC model, where radio N

15-labeled BCAAs contribute to the NSCLC tissue’s nonessential amino acid and nucleotide production[

9]. Similarly, the inhibition of BCAT transaminase activity by glioma IDH1

R132H mutation produced (R)- 2-Hydroxyglutarate leads glioma cells to shift their glutamate reliance from BCAA catabolism to glutamate synthesis from glutamine by isotope tracing[

61].

5.3. Fatty Acid Synthesis and Metabolism

BCAA catabolism is also important for fat biosynthesis. However, the results from the current literature are not homogeneous due to the scarcity of literature. BCAA starvation leads to the cellular accumulation of lipid droplets due to the failure to import fatty acids into the mitochondria in PDAC [

62]. In HCC, the decreased fatty acid oxidation, especially the downregulated CPT1A expression, leads to reduced acetyl-CoA production, which modifies the epigenetic landscape by reduced acetylation, subsequently leading to increased BCAA metabolism[

63]. Nevertheless, another study by Lee et al. demonstrated that knockdown of BCKDHA inhibits fatty acid biosynthesis. Interestingly, CPT1A is also downregulated in benzene-induced leukemia[

64]. In melanoma, increased BCAA catabolism leads to higher expression of FASN and ACLY genes, suggesting higher de novo lipogenesis[

57,

58]. This observation suggested a new notion of the interplay of BCAA catabolism and fatty acid oxidation.

Current literature indicates that aberrant branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) catabolism enhances the production of nonessential amino acids and nucleotides due to increased glutamate generation from BCAAs. The resultant elevated glucose metabolism varies across different types of cancer. Existing research supports the notion that epigenetic modulation through fluctuations in α-ketoglutarate levels leads to cancer cell dependency on glycolysis. The metabolites produced from BCAA catabolism likely contribute to changes in oxidative phosphorylation. Additionally, fatty acid synthesis and oxidation influenced by BCAA catabolism appear context-dependent and warrant further investigation.

6. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting BCAA Metabolism

Previously, we discussed how BCAT and BCKDK expression in multiple cancers modulates BCAA catabolism, favoring cancer growth by reprogramming other metabolic pathways. Metabolites and genes from BCAA catabolism also promote proliferation and survival. Research aims to find compounds to control these enzymes and limit the pro-survival effects. This section reviews current preclinical and clinical compounds or molecules.

6.1. BCAT Inhibitors

Till today, multiple BCAT1 inhibitors have been developed. However, the most commonly used is Gabapentin. Gabapentin, a leucine structural analog, is an inhibitor for BCAT1 and does not affect BCAT2. Its original function is to serve as a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) analog to manage pain. At the millimolar range, it inhibits BCAT1 and does not affect BCAT2, allowing its usage in BCAT1 to increase cancer. Gabapentin first shows its efficacy in preclinical models. It inhibits glioblastoma colony formation and cell proliferation in vitro [

65]. In NSCLC, Gabapentin can reduce proliferation in BCAT1 overexpression TKI-resistant cells [

58]. What is more intriguing is that the combined treatment of Gabapentin and TKI (e.g., ASK120067 and osimertinib) decreased the BCAT1 protein level, presenting potential BCAT1 inhibition by GABA analog [

58]. Other GABA analogs that can overcome TKI resistance in NSCLC are being developed[

66]. Excitingly, there is a current clinical trial (e.g., NCT05664464) ongoing using a combination of Gabapentin with a compound to inhibit glutamate secretion and receptor activation in conjunction with radiotherapy to explore the effectiveness of BCAT1 inhibition in Glioblastoma patients[

67]. Other compounds received less attention; nevertheless, they also showed exceptional preclinical results. Candesartan, an FDA-approved compound that was repurposed for the BCAT1

E61A mutation, was reported by Qian et al. In that paper, they proved the direct binding of Candesartan with BCAT1

E61A, with a reduction of gastric tumor proliferation both in vivo and in vitro[

56]. Eupalinolide B is a compound from

Eupatorium lindleyanum that inhibits BCAT1. Both In vitro and xenograft models shows that Eupalinolide B can retard the proliferation of triple-negative breast cancer[

29]. IDH1

R132H mutation in glioma leads to overproduction of (R)- 2-Hydroxyglutarate, which, though not specifically, inhibits BCAT1 activity, leading to increased dependency on glutaminase[

61]. Compared to the BCAT1, the BCAT2 inhibitor received less attention. Also, the application of BCAT2 inhibitors in cancer research is considerably less than that of BCAT1. BCAT-IN-2 was first identified in a high-throughput screening in 2015; its effectiveness is proven by the retention of BCAAs in serum[

68]. Later, it has been used in multiple studies to reverse the metabolic dysfunction associated with fatty liver disease[

69,

70]. Telmisartan, a repurposed BCAT2 inhibitor, shows promising results in metabolic disease[

71,

72]. However, their efficacy in cancer prevention is lacking. A recent study in melanoma shows that BCAT-IN-2 leads to fewer colony-forming in vitro and reduces aberrant FASN and ACLY expression[

58].

6.2. BCKDK Inhibitors

BCKDK, the kinase that inhibits BCKDH activity, has received attention in cancer research. Modulation of BCKDK expression shows promising results in preclinical studies. In 2023, a series of angiotensin II receptor blocker-like molecules were structurally identified as possible BCKDK inhibitors [

73]. BT2 and Valsartan show BCKDK inhibition in biochemical assays[

73]. Later, BT2 increases the sensitivity of anti-cancer drugs in preclinical breast and ovarian cancer models [

26,

30]. However, recent studies on T-cell immunity reveal that enhanced BCAA metabolism boosts the T-cell anti-cancer capability by increasing the population of CD8

+ T-cells[

60]. Similarly, BCKDK can enhance CAR-T cell therapy efficacy[

74], suggesting that more comprehensive studies on BCKDK inhibition regarding cancer and cancer immunity are necessary.

6.3. Other Potential Therapeutic Targets

In multiple BCAT1 overexpressed cancers, the retention of intracellular BCAAs and reduction of downstream enzyme expression concomitantly exist in several studies. This leads to whether blocking the import of BCAAs or metabolizing these excess BCAAs by increasing the activity of the BCKDH complex will slow cancer progression. However, at the current stage, blocking BCAAs influx is unrealistic as it also transports other amino acids in other cell types, especially immune cells, leaving the only choice to metabolize these BCAAs. Before it can be targeted, a couple of questions need to be answered. First, can BCKAs channels transport BCAT1-converted BCKAs into mitochondria for their subsequent metabolism? Second, can BCAT2 overexpression lead to irreversible increased BCAA catabolism? Third, is channeling BCAAs to mitochondria enough, or does it still require an increase in downstream enzymatic activity? Further research is needed to answer these questions.

7. Concluding Remarks

BCAA catabolism is upregulated in various cancers due to increased activity of BCAT and BCKDK, achieved through higher transcription, mRNA stability, and protein stability. Different cancer types show variations in BCAA catabolism based on BCAT isoforms, which influence reamination or oxidation of BCAA. Other enzymes involved in this process require further study. BCAA catabolism impacts glucose, nucleic acid, amino acid, and fatty acid pathways through metabolic intermediates or epigenetic/transcriptional changes. The exact mechanisms need further elucidation. BCAT and BCKDK are promising targets for cancer therapy, but effective inhibitors and clinical research are needed for practical application.

Funding Statement

MWK is funded by DOD-CDMRP grants CA230221 and CA191042.

Conflict of interest statement

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

Not applicable.

References

- Zhang, Z. Y., Monleon, D., Verhamme, P. & Staessen, J. A. Branched-Chain Amino Acids as Critical Switches in Health and Disease. Hypertension 72, 1012-1022 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Nong, X. et al. The mechanism of branched-chain amino acid transferases in different diseases: Research progress and future prospects. Front Oncol 12, 988290 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Yoneshiro, T. et al. Metabolic flexibility via mitochondrial BCAA carrier SLC25A44 is required for optimal fever. Elife 10 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Du, C., Liu, W. J., Yang, J., Zhao, S. S. & Liu, H. X. The Role of Branched-Chain Amino Acids and Branched-Chain alpha-Keto Acid Dehydrogenase Kinase in Metabolic Disorders. Front Nutr 9, 932670 (2022). [CrossRef]

- White, P. J. et al. The BCKDH Kinase and Phosphatase Integrate BCAA and Lipid Metabolism via Regulation of ATP-Citrate Lyase. Cell Metab 27, 1281-1293 e1287 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Sivanand, S. & Vander Heiden, M. G. Emerging Roles for Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism in Cancer. Cancer Cell 37, 147-156 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H. et al. Branched-chain amino acids sustain pancreatic cancer growth by regulating lipid metabolism. Exp Mol Med 51, 1-11 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Li, J. T. et al. BCAT2-mediated BCAA catabolism is critical for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Cell Biol 22, 167-174 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mayers, J. R. et al. Tissue of origin dictates branched-chain amino acid metabolism in mutant Kras-driven cancers. Science 353, 1161-1165 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Li, J. T. et al. Diet high in branched-chain amino acid promotes PDAC development by USP1-mediated BCAT2 stabilization. Natl Sci Rev 9, nwab212 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lei, M. Z. et al. Acetylation promotes BCAT2 degradation to suppress BCAA catabolism and pancreatic cancer growth. Signal Transduct Target Ther 5, 70 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. et al. Tumour-reprogrammed stromal BCAT1 fuels branched-chain ketoacid dependency in stromal-rich PDAC tumours. Nat Metab 2, 775-792 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yoshiji, H. et al. Attenuation of insulin-resistance-based hepatocarcinogenesis and angiogenesis by combined treatment with branched-chain amino acids and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in obese diabetic rats. J Gastroenterol 45, 443-450 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, J. et al. Dietary supplementation with branched-chain amino acids suppresses diethylnitrosamine-induced liver tumorigenesis in obese and diabetic C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. Cancer Sci 101, 460-467 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Muto, Y. et al. Overweight and obesity increase the risk for liver cancer in patients with liver cirrhosis and long-term oral supplementation with branched-chain amino acid granules inhibits liver carcinogenesis in heavier patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res 35, 204-214 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, A., Nishiyama, M. & Ishizaki, S. Branched-chain amino acids prevent insulin-induced hepatic tumor cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis through mTORC1 and mTORC2-dependent mechanisms. J Cell Physiol 227, 2097-2105 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Wubetu, G. Y. et al. Branched chain amino acid suppressed insulin-initiated proliferation of human cancer cells through induction of autophagy. Anticancer Res 34, 4789-4796 (2014).

- Lee, I. J. et al. Effect of Oral Supplementation with Branched-chain Amino Acid (BCAA) during Radiotherapy in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Double-Blind Randomized Study. Cancer Res Treat 43, 24-31 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y., Wang, Y., Xu, H. & Yi, F. Network meta-analysis of adjuvant treatments for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. BMC Gastroenterol 23, 320 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sideris, G. A., Tsaramanidis, S., Vyllioti, A. T. & Njuguna, N. The Role of Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation in Combination with Locoregional Treatments for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel) 15 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y. et al. Genetic Ablation of LAT1 Inhibits Growth of Liver Cancer Cells and Downregulates mTORC1 Signaling. Int J Mol Sci 24 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ericksen, R. E. et al. Loss of BCAA Catabolism during Carcinogenesis Enhances mTORC1 Activity and Promotes Tumor Development and Progression. Cell Metab 29, 1151-1165 e1156 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Yang, D. et al. Branched-chain amino acid catabolism breaks glutamine addiction to sustain hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Cell Rep 41, 111691 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Tobias, D. K. et al. Dietary Intake of Branched Chain Amino Acids and Breast Cancer Risk in the NHS and NHS II Prospective Cohorts. JNCI Cancer Spectr 5 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Tabesh, M., Teymoori, F., Ahmadirad, H., Mirmiran, P. & Rahideh, S. T. Dietary Branched Chain Amino Acids Association with Cancer and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutr Cancer 76, 160-174 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D. et al. Inhibiting BCKDK in triple negative breast cancer suppresses protein translation, impairs mitochondrial function, and potentiates doxorubicin cytotoxicity. Cell Death Discov 7, 241 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Abdul Kader, S. et al. Defining the landscape of metabolic dysregulations in cancer metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 39, 345-362 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. & Han, J. Branched-chain amino acid transaminase 1 (BCAT1) promotes the growth of breast cancer cells through improving mTOR-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 486, 224-231 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. et al. Small-molecule targeting BCAT1-mediated BCAA metabolism inhibits the activation of SHOC2-RAS-ERK to induce apoptosis of Triple-negative breast cancer cells. J Adv Res (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S. L. et al. Inhibition of branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase kinase augments the sensitivity of ovarian and breast cancer cells to paclitaxel. Br J Cancer 128, 896-906 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chi, R. et al. Elevated BCAA Suppresses the Development and Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Front Oncol 12, 887257 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. et al. BCKDK alters the metabolism of non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 10, 4459-4476 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Mao, L. et al. Branch Chain Amino Acid Metabolism Promotes Brain Metastasis of NSCLC through EMT Occurrence by Regulating ALKBH5 activity. Int J Biol Sci 20, 3285-3301 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Xue, M. et al. Loss of BCAA catabolism enhances Rab1A-mTORC1 signaling activity and promotes tumor proliferation in NSCLC. Transl Oncol 34, 101696 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. et al. Branched-chain amino acid transaminase 1 confers EGFR-TKI resistance through epigenetic glycolytic activation. Signal Transduct Target Ther 9, 216 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. W. et al. GPRC5C drives branched-chain amino acid metabolism in leukemogenesis. Blood Adv 7, 7525-7538 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. et al. PPM1K Regulates Hematopoiesis and Leukemogenesis through CDC20-Mediated Ubiquitination of MEIS1 and p21. Cell Rep 23, 1461-1475 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kikushige, Y. et al. Human acute leukemia uses branched-chain amino acid catabolism to maintain stemness through regulating PRC2 function. Blood Adv 7, 3592-3603 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z. et al. Loss of EZH2 Reprograms BCAA Metabolism to Drive Leukemic Transformation. Cancer Discov 9, 1228-1247 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Tosello, V. et al. BCAT1 is a NOTCH1 target and sustains the oncogenic function of NOTCH1. Haematologica 110, 350-367 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. et al. High expression of BCAT1 sensitizes AML cells to PARP inhibitor by suppressing DNA damage response. J Mol Med (Berl) 102, 415-433 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Raffel, S. et al. BCAT1 restricts alphaKG levels in AML stem cells leading to IDHmut-like DNA hypermethylation. Nature 551, 384-388 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Han, L. et al. METTL16 drives leukemogenesis and leukemia stem cell self-renewal by reprogramming BCAA metabolism. Cell Stem Cell 30, 52-68 e13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Hattori, A. et al. Cancer progression by reprogrammed BCAA metabolism in myeloid leukaemia. Nature 545, 500-504 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Tosello, V., Rompietti, C., Papathanassiu, A. E., Arrigoni, G. & Piovan, E. BCAT1 Associates with DNA Repair Proteins KU70 and KU80 and Contributes to Regulate DNA Repair in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-ALL). Int J Mol Sci 25 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. et al. BCAT1 contributes to the development of TKI-resistant CML. Cell Oncol (Dordr) (2024). [CrossRef]

- Tonjes, M. et al. BCAT1 promotes cell proliferation through amino acid catabolism in gliomas carrying wild-type IDH1. Nat Med 19, 901-908 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. et al. Nuclear Translocation of LDHA Promotes the Catabolism of BCAAs to Sustain GBM Cell Proliferation through the TxN Antioxidant Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 24 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Suh, E. H. et al. In vivo assessment of increased oxidation of branched-chain amino acids in glioblastoma. Sci Rep 9, 340 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. S. et al. Branched-chain ketoacids secreted by glioblastoma cells via MCT1 modulate macrophage phenotype. EMBO Rep 18, 2172-2185 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. et al. Regulation of branched-chain amino acid metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor in glioblastoma. Cell Mol Life Sci 78, 195-206 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z. et al. Targeted inhibition of branched-chain amino acid metabolism drives apoptosis of glioblastoma by facilitating ubiquitin degradation of Mfn2 and oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1870, 167220 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. et al. Cross-talk between BCKDK-mediated phosphorylation and STUB1-dependent ubiquitination degradation of BCAT1 promotes GBM progression. Cancer Lett 591, 216849 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. et al. Metabolic modulation of histone acetylation mediated by HMGCL activates the FOXM1/beta-catenin pathway in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 26, 653-669 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zou, L. et al. FYN-mediated phosphorylation of BCKDK at Y151 promotes GBM proliferation by increasing the oncogenic metabolite N-acetyl-L-alanine. Heliyon 10, e33663 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Qian, L. et al. Enhanced BCAT1 activity and BCAA metabolism promotes RhoC activity in cancer progression. Nat Metab 5, 1159-1173 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. et al. BCKDHA contributes to melanoma progression by promoting the expressions of lipogenic enzymes FASN and ACLY. Exp Dermatol 32, 1633-1643 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. et al. BCAT2 promotes melanoma progression by activating lipogenesis via the epigenetic regulation of FASN and ACLY expressions. Cell Mol Life Sci 80, 315 (2023). [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K. E. & Joyce, J. A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 41, 374-403 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yao, C. C. et al. Accumulation of branched-chain amino acids reprograms glucose metabolism in CD8(+) T cells with enhanced effector function and anti-tumor response. Cell Rep 42, 112186 (2023). [CrossRef]

- McBrayer, S. K. et al. Transaminase Inhibition by 2-Hydroxyglutarate Impairs Glutamate Biosynthesis and Redox Homeostasis in Glioma. Cell 175, 101-116 e125 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Gotvaldova, K. et al. BCAA metabolism in pancreatic cancer affects lipid balance by regulating fatty acid import into mitochondria. Cancer Metab 12, 10 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. et al. CPT1A loss disrupts BCAA metabolism to confer therapeutic vulnerability in TP53-mutated liver cancer. Cancer Lett 595, 217006 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. et al. Targeting IGF2BP1 alleviated benzene hematotoxicity by reprogramming BCAA metabolism and fatty acid oxidation. Chem Biol Interact 398, 111107 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Fala, M. et al. The role of branched-chain aminotransferase 1 in driving glioblastoma cell proliferation and invasion varies with tumor subtype. Neurooncol Adv 5, vdad120 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. et al. Design, Synthesis and Biological Activity Study of gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Derivatives Containing Bridged Bicyclic Skeletons as BCAT1 Inhibitors. Molecules 30 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Mastall, M. et al. A phase Ib/II randomized, open-label drug repurposing trial of glutamate signaling inhibitors in combination with chemoradiotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: the GLUGLIO trial protocol. BMC Cancer 24, 82 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, S. M. et al. The Discovery of in Vivo Active Mitochondrial Branched-Chain Aminotransferase (BCATm) Inhibitors by Hybridizing Fragment and HTS Hits. J Med Chem 58, 7140-7163 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, S., Ho, M. Y., Ng, K. K. & Cheng, K. K. Branched-chain amino acid metabolism: Pathophysiological mechanism and therapeutic intervention in metabolic diseases. Obes Rev 26, e13856 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z. et al. BCATc inhibitor 2 ameliorated mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in oleic acid-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease model. Front Pharmacol 13, 1025551 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Burrage, L. C., Nagamani, S. C., Campeau, P. M. & Lee, B. H. Branched-chain amino acid metabolism: from rare Mendelian diseases to more common disorders. Hum Mol Genet 23, R1-8 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Abdualkader, A. M., Karwi, Q. G., Lopaschuk, G. D. & Al Batran, R. The role of branched-chain amino acids and their downstream metabolites in mediating insulin resistance. J Pharm Pharm Sci 27, 13040 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. et al. Structural studies identify angiotensin II receptor blocker-like compounds as branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase inhibitors. J Biol Chem 299, 102959 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. et al. BCKDK modification enhances the anticancer efficacy of CAR-T cells by reprogramming branched chain amino acid metabolism. Mol Ther 32, 3128-3144 (2024). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).