Submitted:

20 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

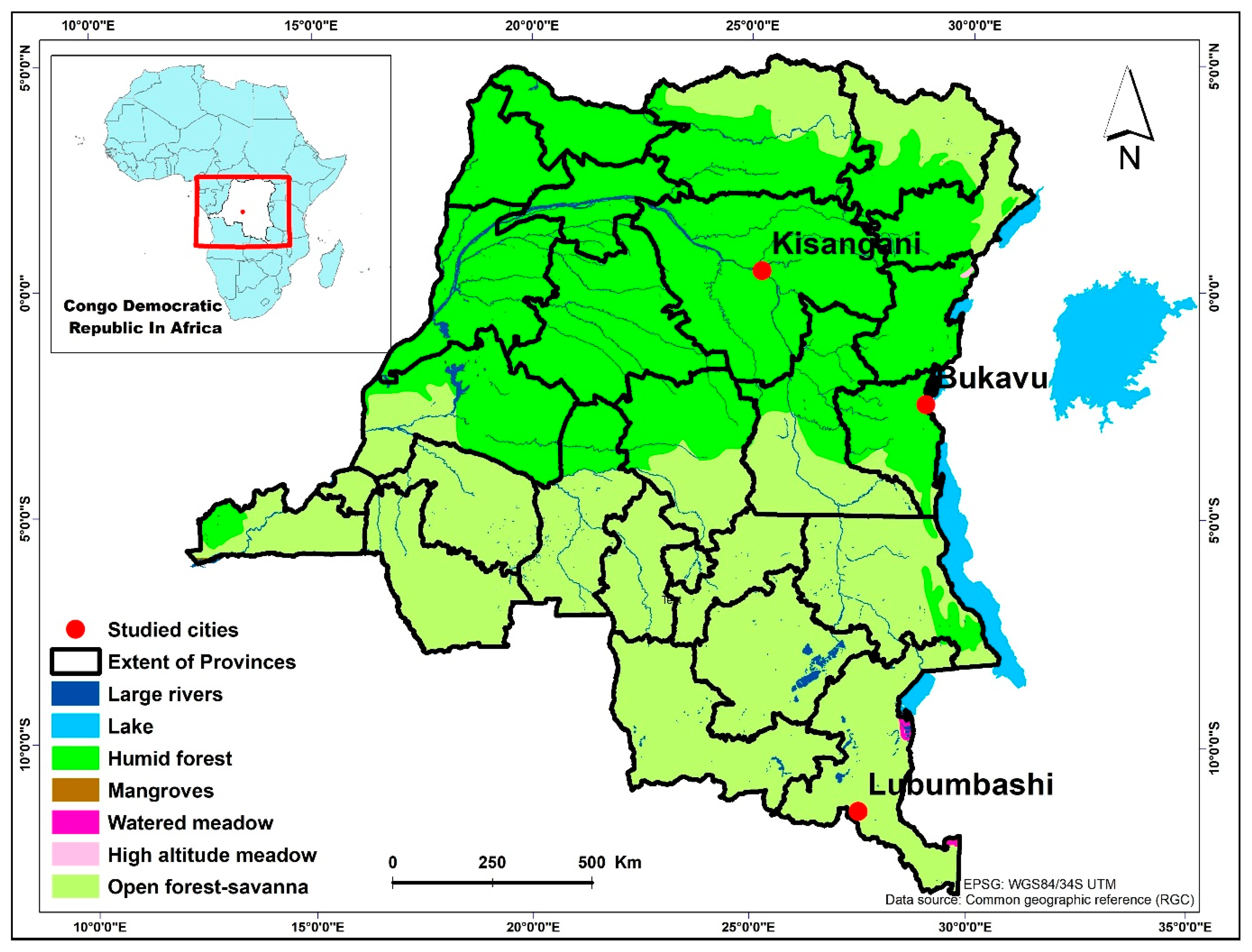

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

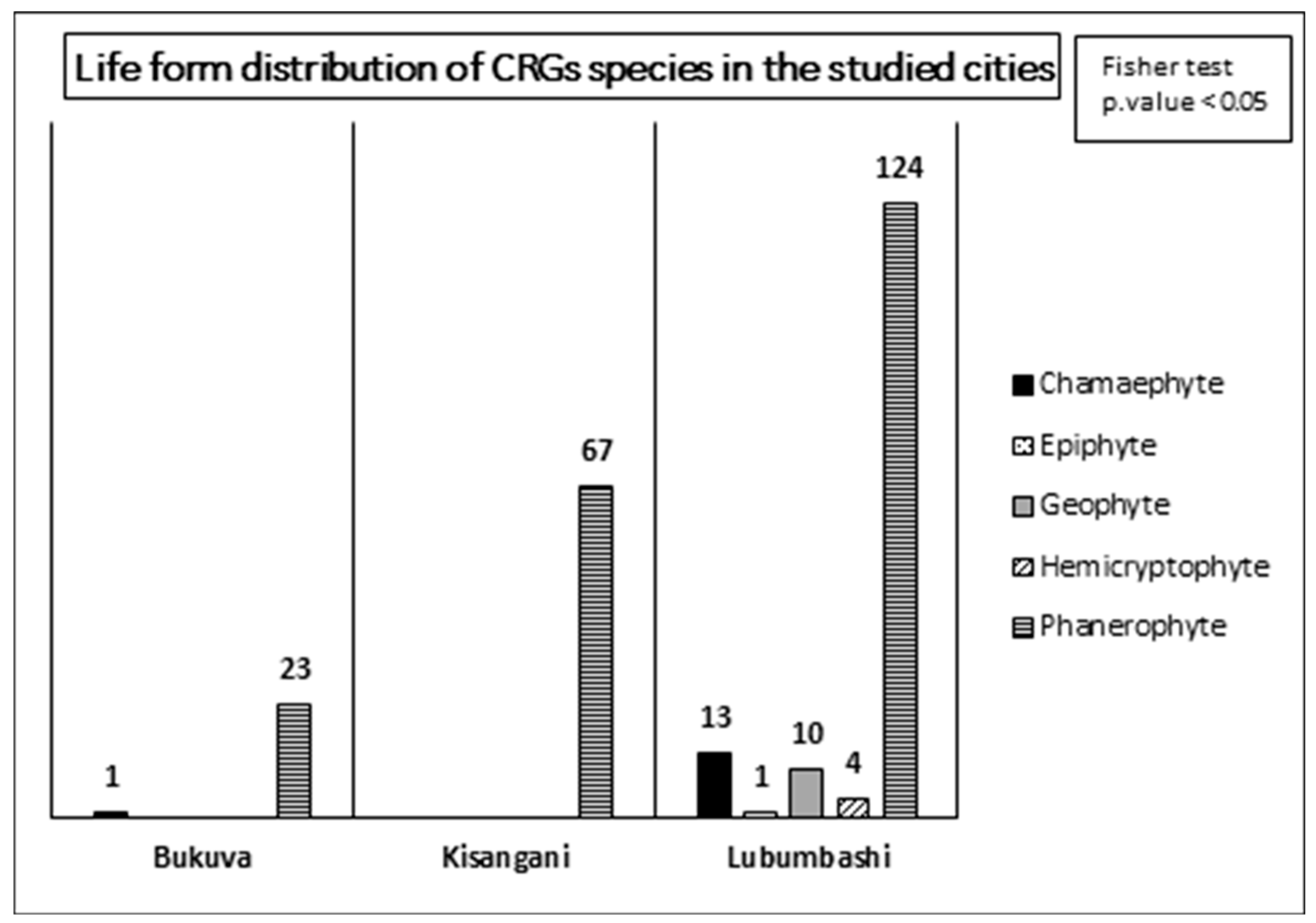

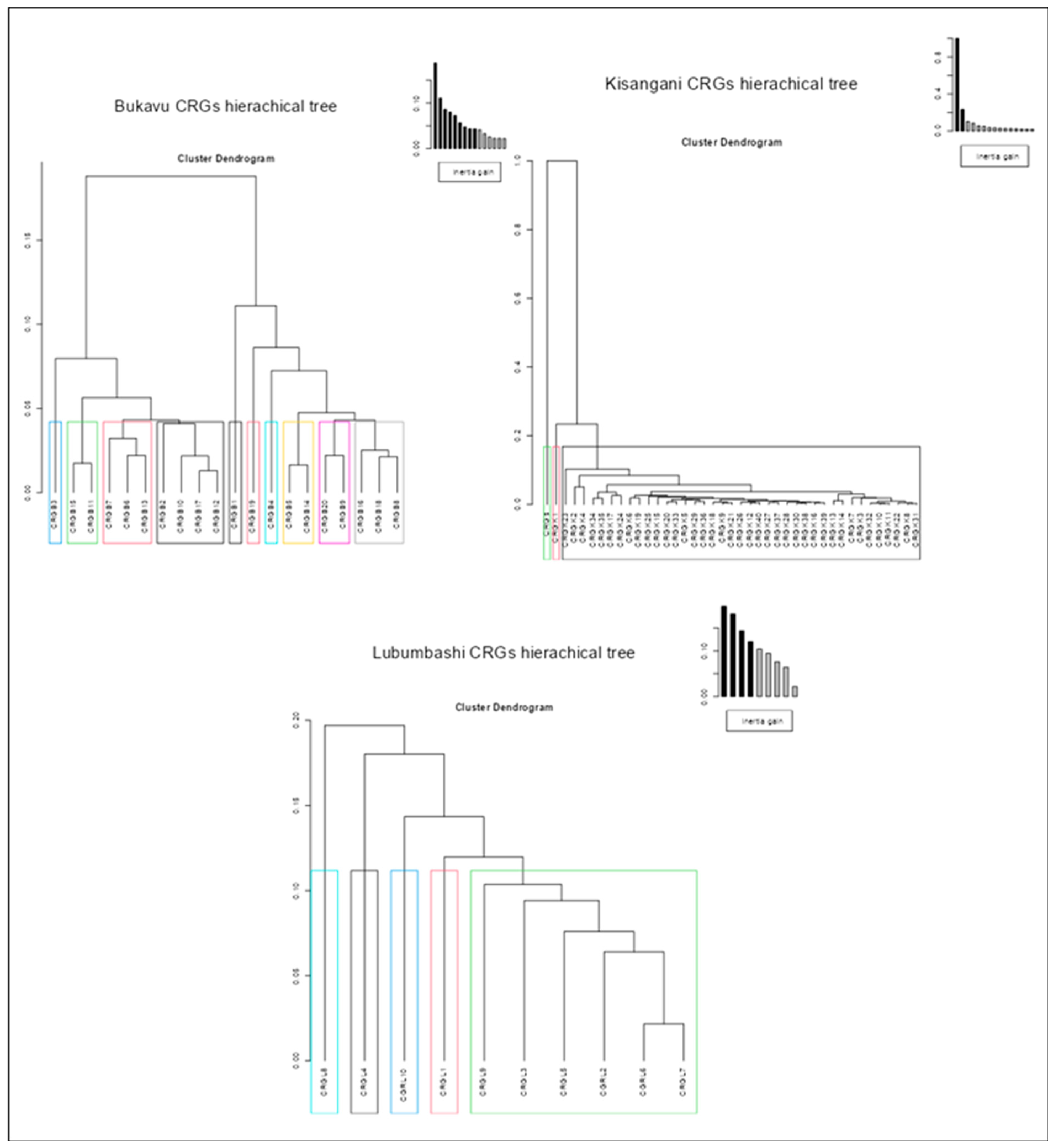

3.1. Quantification of the Plant Composition and Biological Spectrum of Concessions Held by Catholic Religious’ Groups in the Studied Cities and the Effect of Their Areas

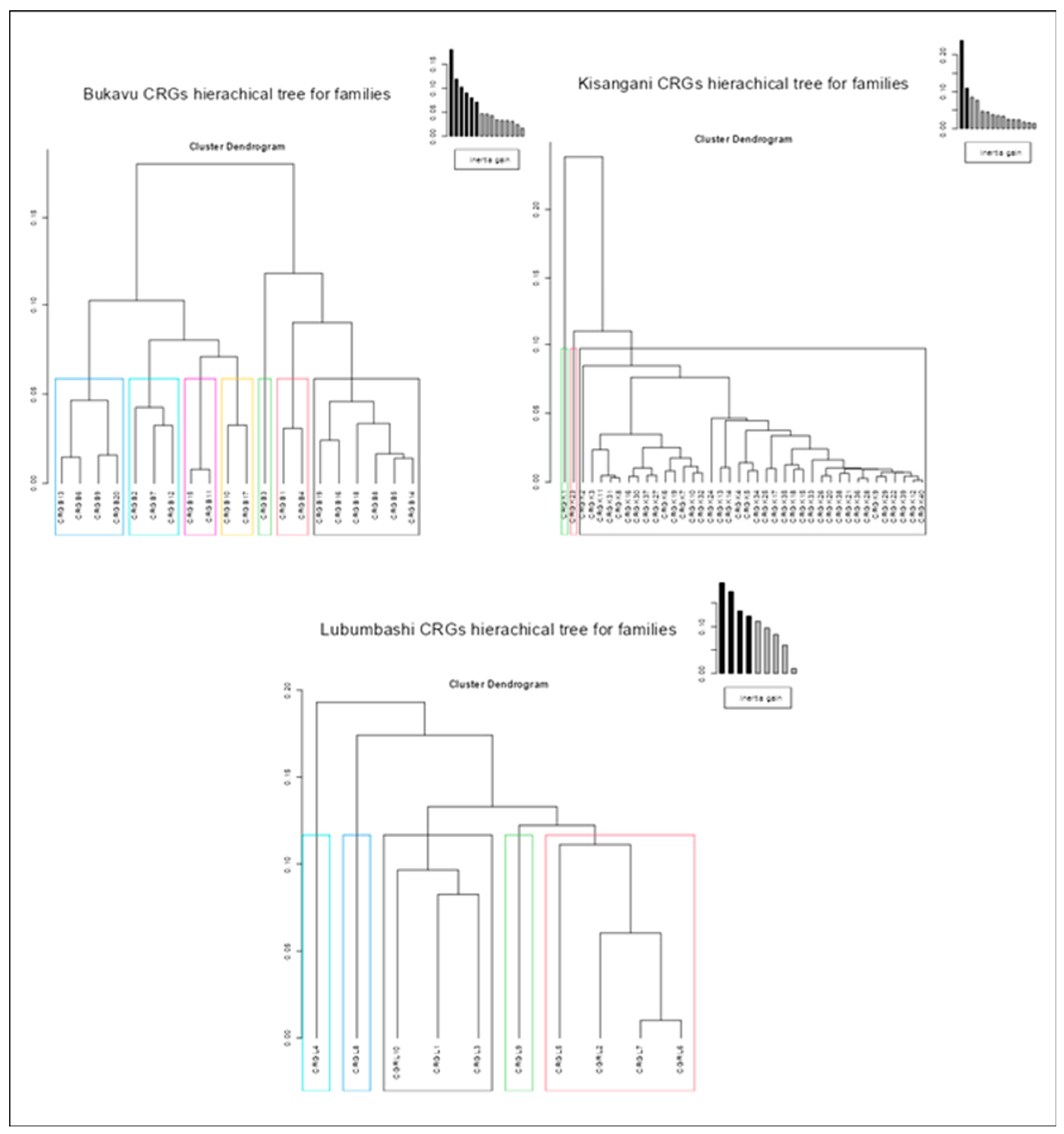

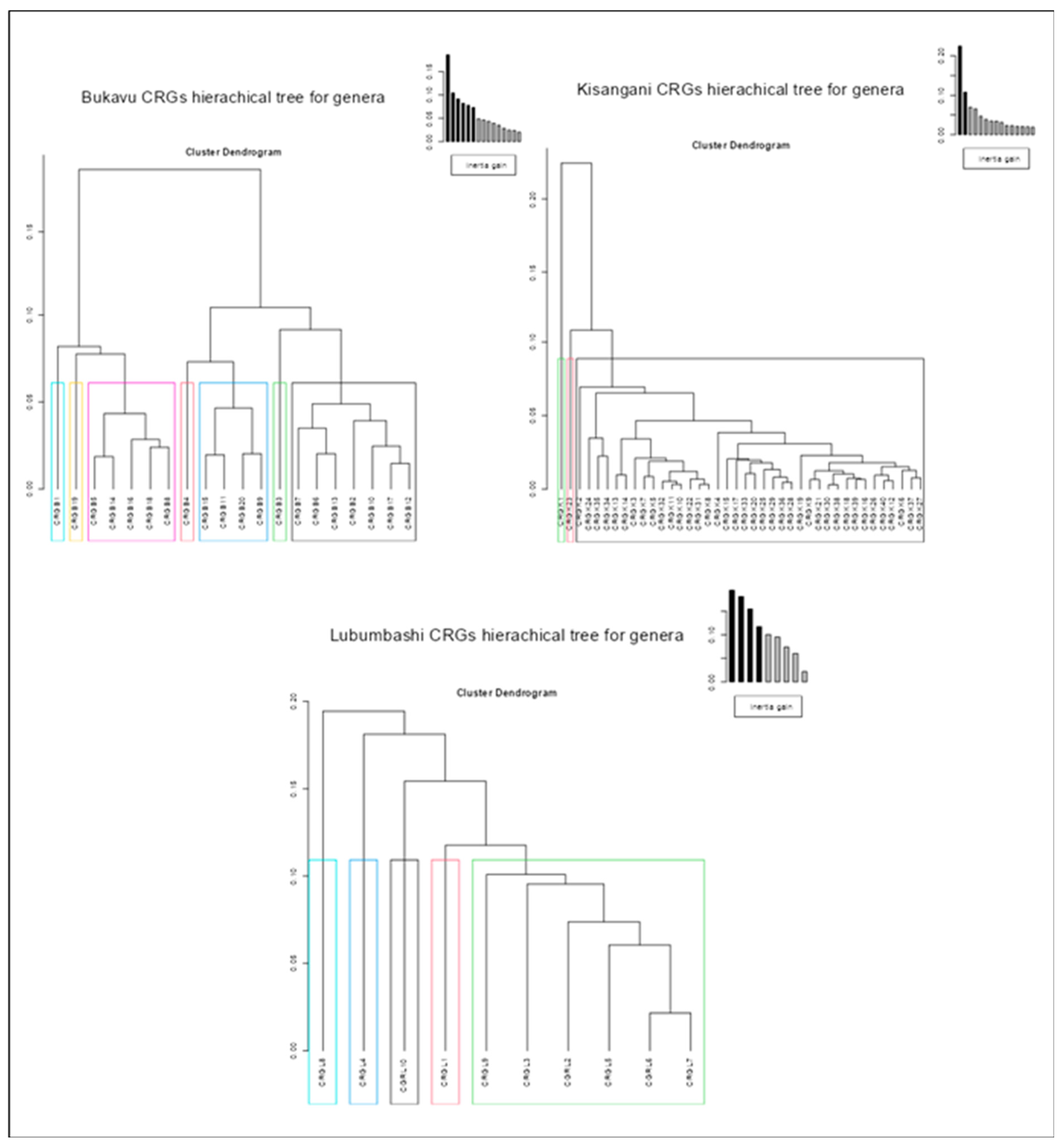

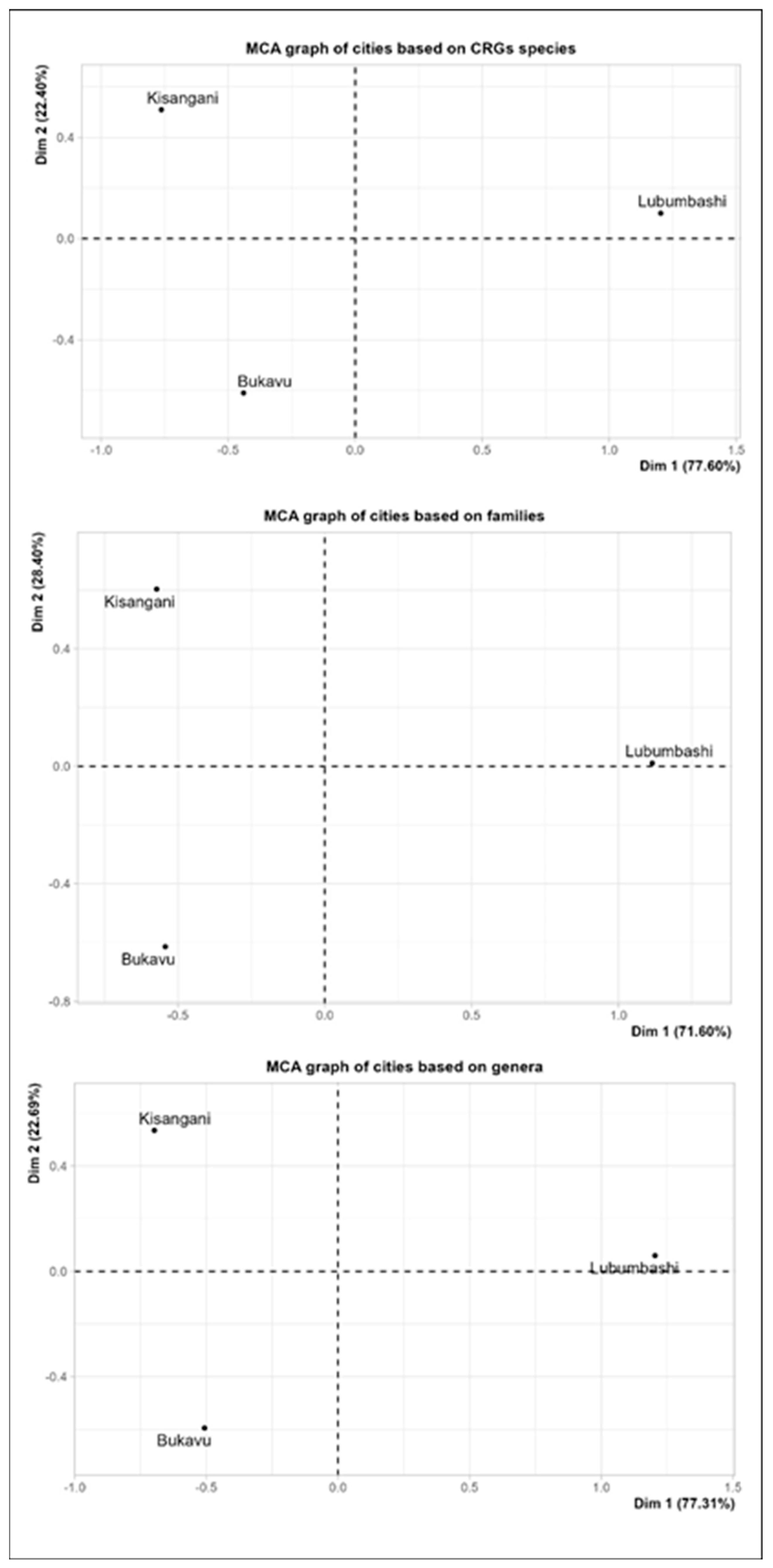

3.2. Comparative Plant Composition Between Concessions Held by Catholic Religious’ Groups and Studied Cities

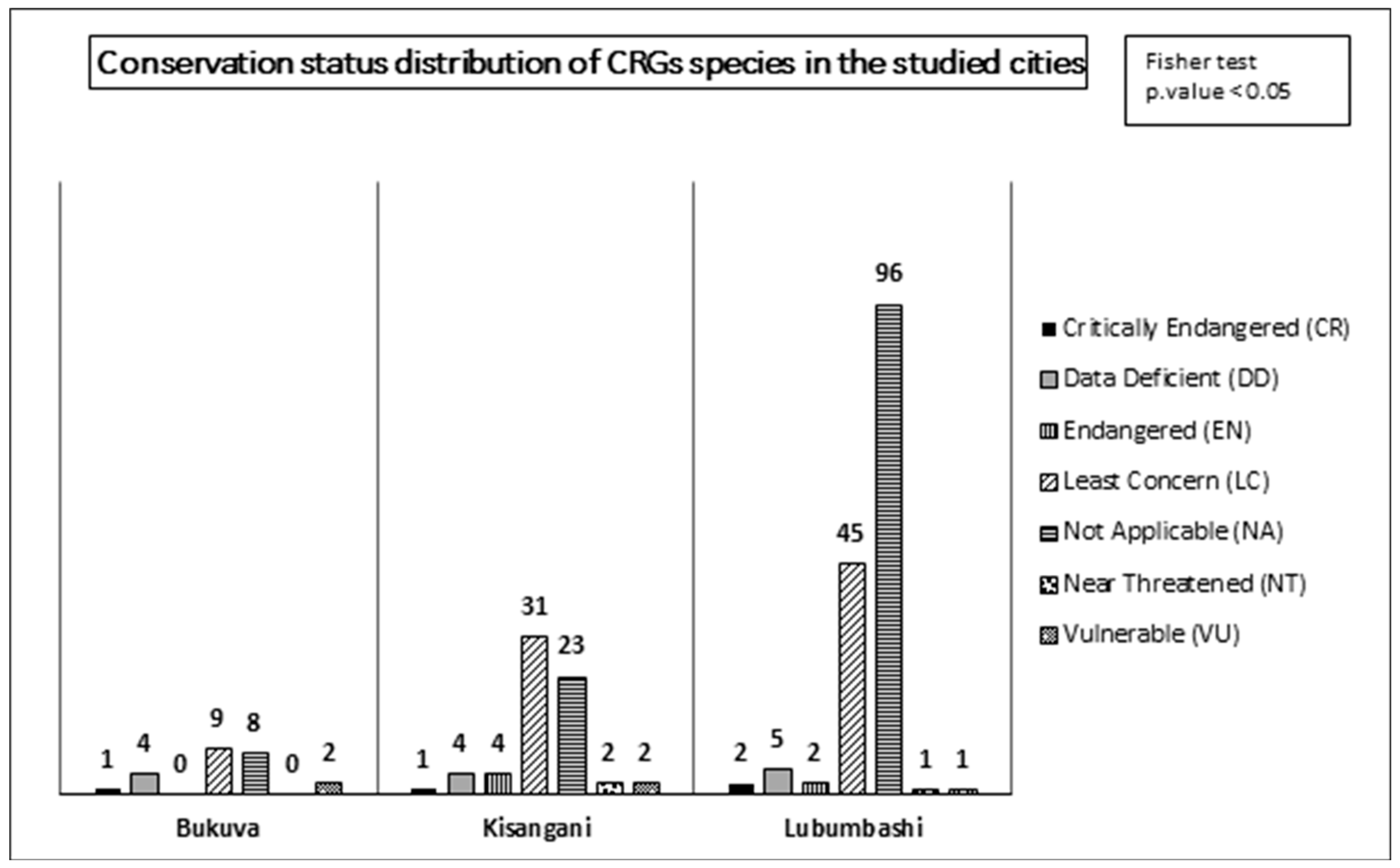

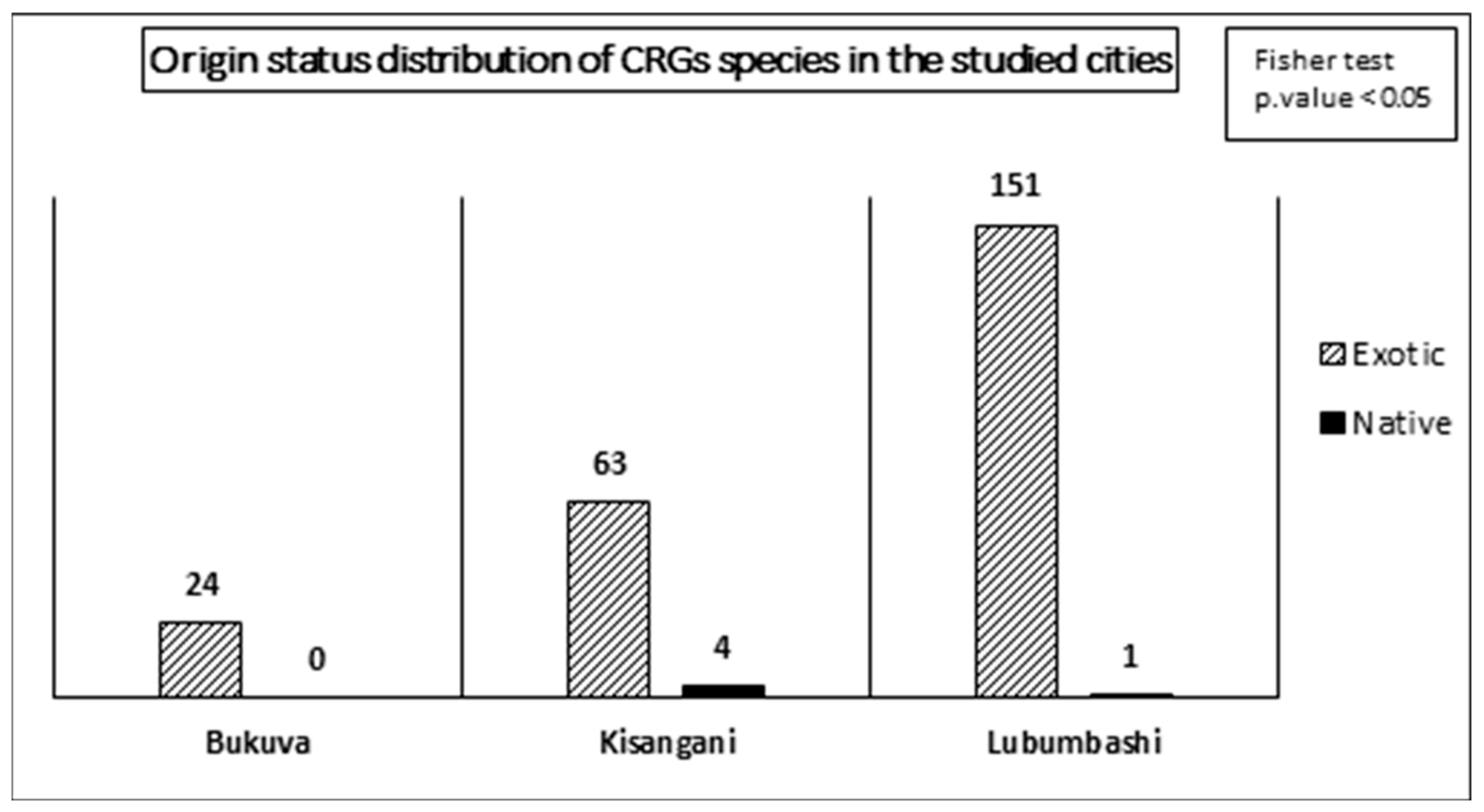

3.3. Distribution of the Vegetation of the CRGs in the Studied Cities According to Their Origin and Conservation Status

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of the Methodological Approach

4.2. The Near Heterogeneity Intra and Inter City in the Plant Composition of CRGs

4.3. The Importance of Phyto-Biodiversity Hosted by CRGs

4.4. Implications for Urban Biodiversity Management and Research Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| N° | Scientific name | Family | Conservation status | Life form | Origin status | Bukavu | Kisangani | Lubumbashi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acacia auriculiformis A.Cunn. ex Benth., 1842 | Fabaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 2 | Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. ex Delile | Fabaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | - |

| 3 | Acalypha wilkesiana Müll.Arg., 1866 | Euphorbiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 4 | Agave americana L. | Asparagaceae | LC | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 5 | Agave attenuata Salm-Dyck, (1834 | Asparagaceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 6 | Aglaonema commutatum Schott, 1856 | Araceae | NA | Hem | Ex | - | - | + |

| 7 | Albizia chinensis (Osbeck) Merr., 1916 | Fabaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 8 | Albizia gummifera (J.F.Gmel.) C.A.Sm., 1930 | Mimosaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 9 | Albizia julibrissin Durazz., 1772 | Fabaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 10 | Alocasia macrorrhizos (L.) G.Don, 1839 | Araceae | NA | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 11 | Aloe arborescens Mill., 1768 | Asphodelaceae | LC | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 12 | Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f., 1768 | Asphodelaceae | NA | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 13 | Alternanthera brasiliana (L.) Kuntze, 1891 | Amaranthaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 14 | Amaranthus hybridus L., 1753 | Amaranthaceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 15 | Annona muricata L., 1753 | Annonaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 16 | Annona senegalensis Pers., 1806 | Annonaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 17 | Anonidium mannii (Oliv.) Engler & Diels , 1901 | Annonaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 18 | Anthocleista schweinfurthii Gilg, 1893 | Loganiaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 19 | Antigonon leptopus Hook. & Arn., 1838 | Polygonaceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 20 | Araucaria cunninghamii Aiton ex D. Don,1837 | Araucariaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 21 | Archontophoenix alexandrae H.Wendl. & Drude, 1875 | Arecaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 22 | Aristaloe aristata Adrian Hardy Haworth, 1825 | Xanthorrhoeaceae | NA | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 23 | Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg, 1941 | Moraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 24 | Artocarpus camansi Blanco, 1837 | Moraceae | NT | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 25 | Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam., 1789 | Moraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 26 | Aspidistra elatior Blume, 1834 | Asparagaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 27 | Asplenium nidus L., 1753 | Aspleniaceae | NA | Hem | Ex | - | - | + |

| 28 | Autranella congolensis (De Wild.) A. Chev. | Sapotaceae | EN | Ph | Na | - | + | - |

| 29 | Averrhoa carambola L., 1753 | Oxalidaceae | DD | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 30 | Bambusa vulgaris Schrad. ex J.C.Wendl., 1810 | Poaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | + | - | + |

| 31 | Bauhinia variegata Carl von Linné, également connu sous le nom de Carl Linnaeus, 1753 | Fabaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 32 | Begonia rex Jules Antoine Adolph Henri Putzeys, 1856 | Begoniaceae | NA | Epi | Ex | - | - | + |

| 33 | Bellucia pentamera Naudin | Melastomataceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 34 | Borassus flabellifer L., 1977 | Arecaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 35 | Bougainvillea glabra Philibert Commerson, 1760 | Nyctaginaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 36 | Breynia disticha J.R.Forst. & G.Forst., 1775 | Euphorbiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 37 | Caladium bicolor (Aiton) Vent., 1801 | Araceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 38 | Callistemon citrinus (Curtis) Skeels, 1913 | Myrtaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 39 | Callistemon viminalis (Sol. ex Gaertn.) G.Don, 1830 | Myrtaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 40 | Cananga odorata Albert Schwenger, 1860 | Annonaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 41 | Canna indica L., 1753 | Cannaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 42 | Carica papaya L., 1753 | Caricaceae | DD | Ph | Ex | + | + | + |

| 43 | Cascabela thevetia (Pers.) K. Schum,1895 | Apocynaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 44 | Casimiroa edulis La Llave & Lex, 1825 | Rutaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 45 | Cassia siamea ( Lam.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby, 1982 | Fabaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 46 | Catharanthus roseus (L.) G.Don, 1837 | Apocynaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 47 | Celosia cristata L., 1753 | Amaranthaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 48 | Cestrum nocturnum L., 1753 | Solanaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 49 | Chamaedorea cataractarum Mart., 1849 | Arecaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 50 | Chamaerops humilis L., 1753 | Arecaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 51 | Chelidonium majus L., 1753 | Papaveraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 52 | Chlorophytum comosum Jacques, 1862 | Asparagaceae | NA | Hem | Ex | - | - | + |

| 53 | Citrus aurantium L., 1753 | Rutaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 54 | Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck, 1765 | Rutaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | + | + | + |

| 55 | Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merrill, 1917 | Rutaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | + | + | - |

| 56 | Citrus reticulata Blanco, 1837 | Rutaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 57 | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck, 1765 | Rutaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | + | + | - |

| 58 | Clerodendrum thomsoniae Balf., 1862 | Lamiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 59 | Clivia miniata William J. Burchell en 1815 | Amaryllidaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 60 | Cocos nucifera L., 1753 | Arecaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 61 | Codiaeum variegatum (L.) Rumph. ex A.Juss., 1824 | Euphorbiaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 62 | Coffea arabica L., 1753 | Rubiaceae | EN | Ph | Ex | - | + | + |

| 63 | Cola acuminata (P.Beauv.) Schott & Endl., 1832 | Malvaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 64 | Coleus amboinicus Lour., 1790 | Lamiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 65 | Coleus scutellarioides (L.) Benth., 1830 | Lamiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 66 | Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott, 1832 | Araceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 67 | Cordyline fruticosa (L.) A.Chev., 1919 | Asparagaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 68 | Cornus drummondii C.A.Mey., 1845 | Cornaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 69 | Cupaniopsis anacardioides (A.Rich.) Radlk., 1879 | Sapindaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 70 | Cuphea hyssopifolia Kunth, 1823 | Lythraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 71 | Cupressus macrocarpa Hartw., 1847 | Cyperaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 72 | Cycas revoluta Carl Peter Thunberg, 1782 | Cycadaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 73 | Cyperus alternifolius Carl von Linné, 1767 | Cyperaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 74 | Cyperus esculentus L., 1753 | Cyperaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 75 | Cyperus papyrus Linné, 1753 | Cyperaceae | NA | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 76 | Dacryodes edulis [G.Don] H.J.Lam, 1832 | Burseraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 77 | Dianella ensifolia (L.) Redouté, 1802 | Asphodelaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 78 | Dieffenbachia seguine (Jacq.) Schott, 1829 | Araceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 79 | Dillenia indica (L.), 1753 | Dilleniaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 80 | Dodonaea viscosa Jacq., 1760 | Sapindaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 81 | Dracaena fragrans (L.) Ker Gawl., 1808 | Asparagaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 82 | Dracaena reflexa Lam., 1786 | Asparagaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 83 | Duranta erecta L., 1753 | Verbenaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 84 | Dypsis lutescens (H.Wendl.) Beentje & J.Dransf., 1995 | Arecaceae | NT | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 85 | Elaeis guineensis Jacq., 1763 | Arecaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | + | + |

| 86 | Entandrophragma candollei Harms, 1896 | Meliaceae | VU | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 87 | Epipremnum aureum (Linden & André) Bunting, 1964 | Araceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 88 | Erythrina abyssinica Lam. ex DC., 1825 | Fabaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 89 | Eucalyptus globulus Labill., 1800 | Myrtaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 90 | Eucharis amazonica Linden ex Planch., 1857 | Liliaceae | NA | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 91 | Euphorbia cotinifolia L., 1753 | Euphorbiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 92 | Euphorbia resinifera O.Berg, 1863 | Euphorbiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 93 | Euphorbia royleana E. Ursch et J. D. Léandri, 1954 | Euphorbiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 94 | Ficus benjamina L., 1767 | Moraceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 95 | Ficus mucuso Welw. ex Ficalho, 1884 | Moraceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 96 | Ficus vallis-choudae Delile, 1843 | Marantaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 97 | Fragaria vesca L., 1753 | Rosaceae | LC | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 98 | Goeppertia makoyana (É.Morren) Borchs. & S.Suárez, 2012 | Marantaceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 99 | Goeppertia zebrina (Sims) Nees, 1831 | Marantaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 100 | Graptophyllum balansae Heine, 1976 | Acanthaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 101 | Grevillea robusta A.Cunn. ex R.Br., 1830 | Proteaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | + | - |

| 102 | Harungana madagascariensis Lam. ex Poir., 1804 | Hypericaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 103 | Hemerocallis fulva (L.) L., 1762 | Asphodelaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 104 | Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A.Juss.) Mull.Arg., 1865 | Euphorbiaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 105 | Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L., 1753 | Malvaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 106 | Hibiscus tiliaceus L., 1753 | Malvaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 107 | Hydrocotyle verticillata Thunb., 1798 | Araliaceae | LC | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 108 | Hymenocallis littoralis (Jacq.) Salisb., 1812 | Amaryllidaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 109 | Hyophorbe lagenicaulis (L.H.Bailey) H.E.Moore, 1976 | Arecaceae | CR | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 110 | Ipomoea indica (Burm.) Merr., 1917 | Convolvulaceae | DD | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 111 | Iresine diffusa Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd., 1806 | Amaranthaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 112 | Iris pseudacorus L., 1753 | Iridaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 113 | Jacaranda mimosifolia D.Don, 1822 | Bignoniaceae | VU | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 114 | Kalanchoe daigremontiana Raym.-Hamet & H.Perrier, 1914 | Crassulaceae | EN | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 115 | Lagerstroemia indica L., 1759 | Lythraceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 116 | Lannea discolor (Sond.) Engl., | Anacardiaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 117 | Lantana camara L., 1753 s.s. | Verbenaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 118 | Lavandula angustifolia Mill., 1768 | Lamiaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 119 | Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) De Wit, 1961 | Fabaceae | CR | Ph | Ex | + | + | + |

| 120 | Leucanthemum maximum (Ramond) DC., 1837 | Asteraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 121 | Ligustrum sinense Lour., 1790 | Oleaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 122 | Liriope muscari (Decne.) L.H.Bailey, 1929 | Asparagaceae | NA | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 123 | Livistona chinensis (Jacq.) R.Br. ex Mart., 1838 | Arecaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 124 | Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh., 1803 | Rosaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 125 | Malvaviscus arboreus Cav., 1787 | Malvaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 126 | Mangifera indica L., 1753 | Anacardiaceae | DD | Ph | Ex | + | + | + |

| 127 | Manihot esculenta Crantz, 1766 | Euphorbiaceae | DD | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 128 | Markhamia lutea (Benth.) K. Schum. | Bignoniaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 129 | Melissa officinalis L., 1753 | Lamiaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 130 | Milicia excelsa (Welw.) C.C.Berg, 1982 | Moraceae | NT | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 131 | Millettia laurentii De Wild | Fabaceae | EN | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 132 | Millettia novo-guineensis Kaneh. & Hatus. | Fabaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 133 | Monstera deliciosa, Liebn., 1849 | Araceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 134 | Moringa oleifera Lam. | Moringaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | + | - |

| 135 | Morus alba L., 1753 | Moraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 136 | Musa acuminata Colla, 1820 | Musaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | + |

| 137 | Musa basjoo Siebold ex Iinuma, 1830 | Musaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 138 | Musanga cecropioides R. Br. ex Tedlie, 1819 | Urticaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 139 | Myrianthus arboreus P. Beauv., 1804-1805 | Cecropiaceae | LC | Ph | Na | - | + | - |

| 140 | Nephrolepis cordifolia (L.) C.Presl, 1836 | Nephrolepidaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 141 | Nephrolepis exaltata (L.) Schott, 1834 | Nephrolepidaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 142 | Nerium oleander L., 1753 | Apocynaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 143 | Newbouldia laevis (P. Beauv.) Seem. | Bignoniaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 144 | Olea europaea L., 1753 | Oleaceae | DD | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 145 | Oxalis griffithii Edgew. & Hook.f. | Oxalidaceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 146 | Passiflora edulis Sims, 1818 | Passifloraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 147 | Peltandra virginica (Linnaeus) Schott & Endlicher | Araceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 148 | Peperomia obtusifolia (L.) A.Dietr., 1831 | Piperaceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 149 | Persea americana Mill., 1768 | Lauraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | + | + | + |

| 150 | Persicaria microcephala Seikei Zusetsu, 1804 | Polygonaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 151 | Petersianthus macrocarpus (P. Beauv.) Liben | Lecythidaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 152 | Petunia sp Wijsman, 1990 | Solanaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 153 | Phoenix canariensis Chabaud, 1882 | Arecaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 154 | Phyllostachys viridiglaucescens (Carrière) Rivière & C.Rivière, 1878 | Poaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 155 | Pinellia pedatisecta Schott | Araceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 156 | Pinus patula Schltdl. & Cham., 1831 | Pinaceae | VU | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 157 | Pittosporum tobira (Murray) W. T. Aiton | Pittosporaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 158 | Plumeria rubra L., 1753 | Apocynaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | + |

| 159 | Polyscias scutellaria (Burm.f.) Fosberg, 1948 | Araliaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 160 | Prunus caroliniana (Mill.) Aiton | Rosaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 161 | Prunus domestica L., 1753 | Rosaceae | DD | Ph | Ex | + | + | - |

| 162 | Pseudospondias microcarpa (A. Rich.) Engl., 1883 | Anacardiaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 163 | Psidium guajava L., 1753 | Myrtaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | + | + |

| 164 | Pteris vittata L., 1753 | Pteridaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 165 | Pycnanthus angolensis (Welw.) Warb. Notizbl. Königl. Bot. Gart, 1895 | Myristicaceae | LC | Ph | Na | - | + | - |

| 166 | Ravenala madagascariensis Sonn., 1782 | Strelitziaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | - |

| 167 | Ribes aureum Pursh, 1813 | Grossulariaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 168 | Ricinodendron heudelotii (Baill.) Pierre ex Heckel, 1898 | Euphorbiaceae | LC | Ph | Na | - | - | + |

| 169 | Rosa multiflora Thunb., 1784 | Rosaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 170 | Rosa chinensis Jacq., 1768 | Rosaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 171 | Roystonea regia (Kunth) O.F.Cook, 1900 | Arecaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 172 | Rudbeckia laciniata L., 1753 | Asteraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 173 | Ruellia simplex C.Wright, 1870 | Acanthaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 174 | Sabal palmetto (Walter) Lodd. ex Schult. & Schult.f., 1830 | Arecaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 175 | Saccharum officinarum L., 1753 | Poaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 176 | Saintpaulia ionantha Rubra, 1896 | Gesneriaceae | VU | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 177 | Salix alba L., 1753 | Salicaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 178 | Sambucus canadensis L., 1753 | Adoxaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 179 | Sanchezia speciosa Leonard, 1926 | Acanthaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 180 | Sansevieria trifasciata Prain 1903 | Asparagaceae | NA | Ge | Ex | - | - | + |

| 181 | Schefflera arboricola (Hayata) Merr. | Araliaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 182 | Senna occidentalis (L.) Link, 1829 | Fabaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 183 | Senna siamea (Lam.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby, 1982 | Fabaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | - | - |

| 184 | Spathiphyllum wallisii Regel, 1877 | Araceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 185 | Spathodea campanulata P.Beauv., 1805 | Bignoniaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 186 | Sphagneticola trilobata (L.) Pruski, 1996 | Asteraceae | NA | Ch | Ex | + | - | - |

| 187 | Spondias dulcis Parkinson, 1773 | Anacardiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 188 | Spondias mombin L., 1753 | Anacardiaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 189 | Strelitzia reginae Banks, 1788 | Strelitziaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 190 | Syagrus romanzoffiana (Cham.) Glassman, 1968 | Arecaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 191 | Symphyotrichum novi-belgii (L.) G.L.Nesom, 1995 | Asteraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 192 | Symphyotrichum salignum (Willd.) G.L.Nesom, 1995 | Asteraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 193 | Syngonium podophyllum Schott, 1851 | Araceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 194 | Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels, 1912 | Lamiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 195 | Syzygium jambos (L.) Alston, 1931 | Lamiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 196 | Syzygium manii (King) N. P. Balakrishnan | Lamiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 197 | Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., 1819 | Apocynaceae | NA | Hem | Ex | - | - | + |

| 198 | Tagetes erecta L., 1753 | Asteraceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 199 | Tectona grandis L.f., 1782 | Lamiaceae | EN | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 200 | Terminalia catappa L., 1767 | Combretaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | + | + | + |

| 201 | Terminalia ivorensis A.Chev., 1909 | Combretaceae | VU | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 202 | Terminalia superba Engl. & Diels, 1899 | Combretaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 203 | Theobroma cacao L., 1753 | Malvaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 204 | Thyrsacanthus tubaeformis (Bertol.) Nees, 1847 | Acanthaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 205 | Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A.Gray, 1883 | Asteraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 206 | Tradescantia fluminensis Vell., 1829 | Commelinaceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 207 | Tradescantia pallida (Rose) D.R.Hunt, 1976 | Commelinaceae | NA | Ch | Ex | - | - | + |

| 208 | Tradescantia zebrina hort. ex Bosse, 1849 | Commelinaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 209 | Treculia africana Decne. ex Trécul | Moraceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 210 | Uapaca esculenta A. Chev. ex Aubrév. & Leandri | Phyllanthaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 211 | Umbellularia californica (Hook. & Arn.) Nutt., 1842 | Lauraceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 212 | Vachellia karroo (Hayne) Banfi & Galasso | Fabaceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 213 | Vernonia amygdalina Delile | Asteraceae | NA | Ph | Na | - | + | - |

| 214 | Vitex trifolia L., 1753 | Lamiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | + | - |

| 215 | Volkameria inermis L., 1753 | Lamiaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 216 | Yucca gigantea Lem., 1859 | Asparagaceae | DD | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 217 | Zamioculcas zamiifolia (Lodd.) Engl., 1905 | Araceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 218 | Zantedeschia aethiopica (L.) Spreng., 1826 | Araceae | LC | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 219 | Zephyranthes longifolia Hemsl. | Amaryllidaceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

| 220 | Zinnia elegans Jacq., 1792 | Asteraceae | NA | Ph | Ex | - | - | + |

References

- Bogaert, J.; Vranken, I.; André, M. Anthropogenic Effects in Landscapes: Historical Context and Spatial Pattern. In Biocultural Landscapes; Hong, S.-K., Bogaert, J., Min, Q., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2014; pp. 89–112 ISBN 978-94-017-8940-0.

- Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.-D.N.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Kaleba, S.C.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of Southeastern Katanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11, 850. [CrossRef]

- Andre, M.; Mahy, G.; Lejeune, P.; Bogaert, J. Vers Une Synthèse de La Conception et Une Définition Des Zones Dans Le Gradient Urbain-Rural. Biotechnologie Agronomie Société Environnement 2014, 18.

- Gutu Sakketa, T. Urbanisation and Rural Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Pathways and Impacts. Research in Globalization 2023, 6, 100133. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Rubio, M.; Bates, P.J.J.; Aung, T.; Hlaing, N.M.; Oo, S.S.L.; Htun, Y.K.Z.; Mar, S.M.O.; Myint, A.; Wai, T.L.L.; Mo, P.M.; et al. Bird Diversity along an Urban to Rural Gradient in Large Tropical Cities Peaks in Mid-Level Urbanization. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16098. [CrossRef]

- World Urbanization Prospects The 2018 Revision.

- Damon, J. Peuplement, migrations, urbanisation:Où va la population mondiale ? Population & Avenir 2016, 728, 4–7. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Qiao, W.; Liu, J. Dynamic Feedback Analysis of Influencing Factors of Existing Building Energy-Saving Renovation Market Based on System Dynamics in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 273. [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Biloso, A.; I., V.; Andre, M. Peri-Urban Dynamics: Landscape Ecology Perspectives. In; 2015; pp. 63–73 ISBN 978-2-87016-136-4.

- Huang, H.; Zhuo, L.; Li, Z.; Ji, X.; Wu, P. Effects of Multidimensional Urbanisation on Water Footprint Self-Sufficiency of Staple Crops in China. Journal of Hydrology 2023, 618, 129275. [CrossRef]

- Power, A.L.; Tennant, R.K.; Jones, R.T.; Tang, Y.; Du, J.; Worsley, A.T.; Love, J. Monitoring Impacts of Urbanisation and Industrialisation on Air Quality in the Anthropocene Using Urban Pond Sediments. Front. Earth Sci. 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Kalumba Mwanke, A.; Yamba, A.M.; Nkuku Khonde, C.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Tree Diversity and Structure on Green Space of Urban and Peri-Urban Zones: The Case of Lubumbashi City in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 41, 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, I.; Osumanu, I. How Urbanisation Shapes Availability of Provisioning Ecosystem Services in Peri-Urban Ghana. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 2023, 15, 282–298. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, R.; Kabisch, N. Parks Under Stress: Air Temperature Regulation of Urban Green Spaces Under Conditions of Drought and Summer Heat. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 849965. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, S.; He, S.; Qi, W.; Bao, C.; Ma, H.; Fan, Y.; et al. Global Impacts of Future Urban Expansion on Terrestrial Vertebrate Diversity. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1628. [CrossRef]

- Threlfall, C.; Mata, L.; Mackie, J.; Hahs, A.; Stork, N.; Williams, N.; Livesley, S. Increasing Biodiversity in Urban Green Spaces through Simple Vegetation Interventions. Journal of Applied Ecology 2017, 54. [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.J. L’avenir de La Foresterie Urbaine Dans Les Pays En Développement : Un Document de Réflexion. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/t1680f/t1680f00.htm (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Aram, F.; Higueras Garcia, E.; Solgi, E.; Mansournia, S. Urban Green Space Cooling Effect in Cities. Heliyon 2019, 5, 1339. [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough.’ Landscape and Urban Planning 2014, 125, 234–244. [CrossRef]

- Kothencz, G.; Kolcsár, R.; Cabrera-Barona, P.; Szilassi, P. Urban Green Space Perception and Its Contribution to Well-Being. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 766. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.C.; Fluehr, J.M.; McKeon, T.; Branas, C.C. Urban Green Space and Its Impact on Human Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15, 445. [CrossRef]

- Yilma, G.; Derero, A. Carbon Stock and Woody Species Diversity Patterns in Church Forests along Church Age Gradient in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Urban Ecosystems 2020, 23. [CrossRef]

- Neal, S.; Bennett, K.; Jones, H.; Cochrane, A.; Mohan, G. Multiculture and Public Parks: Researching Super-Diversity and Attachment in Public Green Space. Population, Space and Place 2015, 21, 463–475. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Sun, F.; Che, Y. Public Green Spaces and Human Wellbeing: Mapping the Spatial Inequity and Mismatching Status of Public Green Space in the Central City of Shanghai. Urban forestry & urban greening 2017, 27, 59–68. [CrossRef]

- You, H. Characterizing the Inequalities in Urban Public Green Space Provision in Shenzhen, China. Habitat International 2016, 56, 176–180. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Ma, X. Evaluation of the Accessible Urban Public Green Space at the Community-Scale with the Consideration of Temporal Accessibility and Quality. Ecological Indicators 2021, 131, 108231. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; li, Z.; Webster, C. Estimating the Mediate Effect of Privately Green Space on the Relationship between Urban Public Green Space and Property Value: Evidence from Shanghai, China. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 439–447. [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Bird, N.; Hallingberg, B.; Phillips, R.; Williams, D. The Role of Perceived Public and Private Green Space in Subjective Health and Wellbeing during and after the First Peak of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Landscape and Urban Planning 2021, 211, 104092. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, H.I.; Eckberg, E.; Widenberg, M.; Alkan Olsson, J. Gardens’ Contribution to People and Urban Green Space. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 63, 127198. [CrossRef]

- Hutt-Taylor, K. Assessing Urban Tree Taxonomic Diversity, Composition and Structure across Public and Private Green Space Types: A Community-Based Tree Inventory. masters, Concordia University, 2021.

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.U.; Kalonda, B.K.; Mukenza, M.M.; Mleci, J.Y.; Kalenga, A.M.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Exploring Floristic Diversity, Propagation Patterns and Plant Functions in Domestic Gardens Across Urban Planning Gradient in Lubumbashi, DR Congo. 2024.

- Lubbe, C.S.; Siebert, S.J.; Cilliers, S.S. Floristic Analysis of Domestic Gardens in the Tlokwe City Municipality, South Africa. Bothalia 2011, 41, 351–361. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kofahi, S.D.; Al-Kafawin, A.M.; Al-Gharaibeh, M.M. Investigating Domestic Gardens Landscape Plant Diversity, Implications for Valuable Plant Species Conservation. Environ Dev Sustain 2023, 26, 21259–21279. [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Kalumba Mwanke, A.; Yamba, A.M.; Nkuku Khonde, C.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Tree Diversity and Structure on Green Space of Urban and Peri-Urban Zones: The Case of Lubumbashi City in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 41, 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Mpibwe Kalenga, A.; Yona Mleci, J.; N’Tambwe Nghonda, D.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Assessment of Street Tree Diversity, Structure and Protection in Planned and Unplanned Neighborhoods of Lubumbashi City (DR Congo). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3830. [CrossRef]

- Musanganya, D. La matrice intellectuelle du catholicisme social face à l’Etat faible au Congo ( RDC) entre 1990 et 2018. phdthesis, Université Paris-Est, 2023.

- André, G.; Poncelet, M. Héritage Colonial et Appropriation Du Pouvoir d’éduquer. Approche Socio-Historique Du Champ de l’éducation Primaire En RDC. Cahiers de la recherche sur léducation et les savoirs 2013, 2, 271.

- Kasangana, A.C. L’église catholique et le Congo « belge » : approche historico-juridique des relations institutionnelles (1885-1960). phdthesis, Université Paris-Saclay, 2022.

- G, H.; B, T.; F, Y.; I, Y. Diversité et Connaissance Ethnobotanique Des Espèces Végétales de La Forêt Sacrée de Badjamè et Zones Connexes Au Sud-Ouest Du Benin. Revue Scientifique et Technique Forêt et Environnement du Bassin du Congo 2016, 7, 28–36. [CrossRef]

- Kaczyńska, M. The Church Garden as an Element Improving the Quality of City Life – A Case Study in Warsaw. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2020, 54, 126765. [CrossRef]

- Statistics of the Catholic Church in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in South Sudan as of 31 December 2021 (from the Central Office for Church Statistics) Available online: https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2023/01/24/230124d.html (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Savard, J.-P.L.; Clergeau, P.; Mennechez, G. Biodiversity Concepts and Urban Ecosystems. Landscape and Urban Planning 2000, 48, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Les Jardins Comme Moyens d’existence Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/y5112f/y5112f00.htm (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Tremblay, M.-H.; Simard, M. Les effets de proximité dans l’appropriation collective d’un grand parc paysager à saguenay. vertigo 2011, 11.

- Gueymard, S. Facteurs environnementaux de proximité et choix résidentiels. Développement durable et territoires. Économie, géographie, politique, droit, sociologie 2006. [CrossRef]

- Sakhraoui, N.; Metallaoui, S.; Chefrour, A.; Hadef, A. La flore exotique potentiellement envahissante d’Algérie : première description des espèces cultivées en pépinières et dans les jardins. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2019. [CrossRef]

- PopulationData.net Available online: https://www.populationdata.net/pays/republique-democratique-du-congo/aires-urbaines (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- L’insalubrité Publique et La Santé Environnementale Dans Le District Sanitaire de Bukavu - ISDR BUKAVUISDR BUKAVU Available online: https://isdrbukavu.ac.cd/produit/linsalubrite-publique-et-la-sante-environnementale-dans-le-district-sanitaire-de-bukavu/ (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- United Nations Conférence des Nations Unies sur le logement et le développement urbain durable : Habitat III | Nations Unies Available online: https://www.un.org/fr/conferences/habitat/quito2016 (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Vwima Ngezirabona, S.; Mastaki, J.-L.; Lebailly, P. Le rôle du commerce frontalier des produits alimentaires avec le Rwanda dans l’approvisionnement des ménages de la ville de Bukavu (province du Sud-Kivu). In Brot, Jean (Ed.) Les Cahiers de l’Association Tiers-Monde n° 28-2013 : XXVIIIes Journées sur le Développement “Mobilités internationales, déséquilibres et développement : vers un développement durable et une mondialisation décarbonée ?” 2013.

- Balasha, A.M.; Murhula, B.B.; Munahua, D.M. Yard Farming in the City of Lubumbashi: Resident Perceptions of Home Gardens in Their Community. Journal of City and Development 2019, 1, 46–53.

- Sêdami, A.B.; Naéssé, A.V.; Julien, D.; Firmin, A.D. Practice of Home Gardens (HG) in the Suburban Area between Cotonou and Ouidah in Southern Benin. 2016.

- Raunkiaer, C. The Life Forms Of Plants And Statistical Plant Geography; The Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1934;

- IUCN Guidelines for Species Conservation Planning : Version 1.0; 2017; ISBN 978-2-8317-1877-4.

- RStudio Team RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/. (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Logan, M. Biostatistical Design and Analysis Using R: A Practical Guide; 1st ed.; Wiley, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4051-9008-4.

- Pauline Vaissie, Astrid Monge, Francois Husson Factoshiny: Perform Factorial Analysis from “FactoMineR” with a Shiny Application 2015, 2.6.

- Subba, L.; Pala, N.; Shukla, G.; Chakravarty, S. Inventory of Flora in Home Gardens of Sub-Humid Tropical Landscapes, West Bengal, India. 2016, 17, 47–54.

- Regassa, R. Useful Plant Species Diversity in Homegardens and Its Contribution to Household Food Security in Hawassa City, Ethiopia. African Journal of Plant Science 2016, 10, 211–233. [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Andrade, L.H.C.; Caballero, J. Structure and Floristics of Homegardens in Northeastern Brazil. Journal of Arid Environments 2005, 62, 491–506. [CrossRef]

- Samus, A.; Freeman, C.; Dickinson, K.; van Heezik, Y. An Examination of the Factors Influencing Engagement in Gardening Practices That Support Biodiversity Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Biological Conservation 2023, 286, 110252. [CrossRef]

- Lemessa, D.; Legesse, A. Non-Crop and Crop Plant Diversity and Determinants in Homegardens of Abay Chomen District, Western Ethiopia. Biodiversity International Journal 2018, 2. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Webb, E.L. Can Homegardens Conserve Biodiversity in Bangladesh? Biotropica 2008, 40, 95–103. [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Gerstner, K.; Kreft, H. Environmental Heterogeneity as a Universal Driver of Species Richness across Taxa, Biomes and Spatial Scales. Ecol Lett 2014, 17, 866–880. [CrossRef]

- Idohou, R.; Fandohan, A.; Salako, V.; Kassa, B.; Gbedomon, R.; Yédomonhan, H.; Glele Kakaï, R.L.; Assogbadjo, A. Biodiversity Conservation in Home Gardens: Traditional Knowledge, Use Patterns and Implications for Management. International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management 2014, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lepczyk, C.; Aronson, M.; Evans, K.; Goddard, M.; Lerman, S.; MacIvor, J.S. Biodiversity in the City: Fundamental Questions for Understanding the Ecology of Urban Green Spaces for Biodiversity Conservation. BioScience 2017, 67. [CrossRef]

- Souto, T.; Ticktin, T. Understanding Interrelationships Among Predictors (Age, Gender, and Origin) of Local Ecological Knowledge1. Economic Botany 2012, 66. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.M.; Nair, P.K.R. The Enigma of Tropical Homegardens. Agroforestry Systems 2004, 61, 135–152. [CrossRef]

- Joscha, B.; Veith, M.; Hochkirch, A. Biodiversity in Cities Needs Space: A Meta-Analysis of Factors Determining Intra-Urban Biodiversity Variation. Ecology Letters 2015, 18. [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, S.M.; Chiarucci, A.; Fox, G.A.; Helmus, M.R.; McGlinn, D.J.; Willig, M.R. The Underpinnings of the Relationship of Species Richness with Space and Time. Ecological Monographs 2011, 81, 195–213. [CrossRef]

- Niklas, K.J. Life Forms, Plants. In Encyclopedia of Ecology; Jørgensen, S.E., Fath, B.D., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2008; pp. 2160–2167 ISBN 978-0-08-045405-4.

- Nguinambaye, M.; Nana, R.; Mbayngone, E.; Djinet, A.; Badiel, B.; Tamini, Z. Distribution et Usages Des Ampelocissus Dans La Zone de Donia Au Sud Du Tchad. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2015, 9, 186. [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Malaisse, F.; Yona, J.M.; Mwamba, T.M.; Bogaert, J. Diversity, Use and Management of Household-Located Fruit Trees in Two Rapidly Developing Towns in Southeastern D.R. Congo. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 63, 127220. [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumari, J.; Prabha vasu, S.; Rubi, J.; Raj, T.L.; Rayan, S. Floristic Diversity Assessment of Home Garden in Palayamkottai Region of Tirunelveli District, Tamil Nadu a Means of Sustainable Biodiversity Conservation. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development 2019, 3, 1484–1491. [CrossRef]

| City | Old Name | Location | Number of Municipalities | Area (km2) | Population Size in 2024 (Inhabitants) | Altitude | Climate Type | Annual Rainfall (mm/year) | Mean Annual Temperature (°C) | Dominant Soil | Characteristic Plant Formation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bukavu | Costermansville | 2°30’55’’ south latitude and 28°50’42’’ east longitude | 3 municipalities: Kadutu, Ibanda and Bagira | 60 | 1 012 053 | Mean: 1.654 m Min: 1.422 m Maxi: 2.190 m |

Tropical mountain climate (BWh) Dry season: mid-May to mid-September Rainy season: mid-September to mid-May |

1500-2200 | 20,5 | Andosols (Volcanic, clayey, permeable soil belonging to the red clay soil group) |

Mountain forest |

| Kisangani | Stanleyville | 0°31’ north latitude, 25°11’ east longitude | 6 municipalities: Makiso, Tshopo, Mangobo, Kabondo Kisangani and Lubunga | 1910 | 1 602 144 | Mean: 415 m Min: 378 m Maxi: 503 m |

Hot, humid equatorial climate (Af) Two rainy seasons: September to November and March to May Long dry season: January Short dry season: July to August |

1500 - 2000 | 25 | Ferrasols (Mostly sandy-clay soils) |

Dense rainforest |

| Lubumbashi | Elisabethville | 27°48’61’’1 East longitude, 11° 61’55 3’’ South latitude | 7 municipalities: Lubumbashi, Kenya, Kampemba, Katuba, Kamalondo, Ruashi and Annexe |

747 | 2 096 961 | Mean: 1259 m Mini: 1167 m Maxi: 1411 m |

CW6 climate Rainy season: November Dry season: May to September to March Transition months: April and October |

1200 | 20 | Ferrasols (Ferralitic soils mostly represented by young and red soils) |

miombo forest |

| CRG’s code | CRG’s name | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|

| Lubumbashi | ||

| CRGL1 | Convent of Saint Paul Parish | 0.11 |

| CRGL2 | Theological Institute - Chaplains of Work | 0.32 |

| CRGL3 | Tabora University Cultural Center | 0.17 |

| CRGL4 | Theologicum | 1.25 |

| CRGL5 | Provincial House of the Franciscans | 0.2 |

| CRGL6 | Tertiary Capuchin Sisters - Nazareth Homes | 0.15 |

| CRGL7 | Scholasticate - Chaplains of Work | 0.15 |

| CRGL8 | Laura House | 8.32 |

| CRGL9 | Carmelite Sisters | 0.58 |

| CRGL10 | Mercedarian Missionaries | 0.19 |

| Bukavu | ||

| CRGB1 | Bukavu Amani Center | 0.51 |

| CRGB2 | Kasongo Procuracy | 6.59 |

| CRGB3 | The Corniche | 0.24 |

| CRGB4 | Xaverian Sisters | 5.07 |

| CRGB5 | Missionaries of Africa | 0.41 |

| CRGB6 | Cirezi High School | 0.52 |

| CRGB7 | Cathedral of Our Lady of Bukavu | 1.05 |

| CRGB8 | Solidarity | 2.89 |

| CRGB9 | Saint Joseph Sisters | 1.09 |

| CRGB10 | Father Vavassori Health Center | 3.85 |

| CRGB11 | Saint John the Baptist Parish – Cahi | 2.37 |

| CRGB12 | Antonella School | 0.97 |

| CRGB13 | Holy Family Parish of Bagira | 0.06 |

| CRGB14 | Nyakavogo High School | 5.13 |

| CRGB15 | Nyakavogo Primary School | 2.15 |

| CRGB16 | Catholic University of Bukavu Bugaboo | 1.29 |

| CRGB17 | Saint Francis Xavier Parish - Kadutu | 0.65 |

| CRGB18 | Fundi Maendeleo Technical Institute | 14.38 |

| CRGB19 | Wima High School | 19.71 |

| CRGB20 | General Economat | 5.64 |

| Kisangani | ||

| CRGK1 | Kisangani Little Seminary of Mandombe | 3 |

| CRGK2 | Saint Peter Parish | 3 |

| CRGK3 | Saint Albert Chapel | 2 |

| CRGK4 | Saint Martha Parish | 8 |

| CRGK5 | Cathedral of Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary | 8 |

| CRGK6 | Father Dehonus Scholasticate | 8 |

| CRGK7 | Simama Center | 3 |

| CRGK8 | Servant Sisters of Jesus | 10 |

| CRGK9 | Sisters of the Holy Family Mediatrix | 1 |

| CRGK10 | Augustinian Sisters | 1 |

| CRGK11 | Pastoral House of the Sacred Heart | 10 |

| CRGK12 | Convent of the Priests of Mont Fortaint | 3 |

| CRGK13 | Bel Vedere | 25 |

| CRGK14 | Saint Gabriel Parish | 4 |

| CRGK15 | Convent of the Priests of the Sacred Heart | 2 |

| CRGK16 | Sisters of Jesus Educator Station Kis-Bondo | 2 |

| CRGK17 | Canonical Sisters | 3 |

| CRGK18 | Sisters Novitiate Holy Family | 3 |

| CRGK19 | Saint Camille Parish | 0.4 |

| CRGK20 | Josephites of Kinzambi | 0.49 |

| CRGK21 | Sisters Holy Family Artisan | 0.15 |

| CRGK22 | Marist Brothers | 2 |

| CRGK23 | Formation House Scholasticate | 2 |

| CRGK24 | Saint Augustine Major Seminary | 1 |

| CRGK25 | Saint Lawrence Parish | 4 |

| CRGK26 | Deo Soli/Scholasticate | 0.25 |

| CRGK27 | Daughters of Wisdom | 0.08 |

| CRGK28 | Sisters Immaculate Conception | 7 |

| CRGK29 | Sisters Saint Joseph House | 0.32 |

| CRGK30 | Saint John Parish | 2.5 |

| CRGK31 | Blessed Isidore Bakanja Parish | 0.49 |

| CRGK32 | Blessed Anuarité Parish | 2 |

| CRGK33 | Deo Soli/Scholasticate 7th Plateau | 0.25 |

| CRGK34 | Comboni House | 0.49 |

| CRGK35 | Technical High School Mapendano | 7 |

| CRGK36 | The Moinnaux | 4 |

| CRGK37 | Mary Queen of Peace | 49 |

| CRGK38 | Christ the King Parish | 4 |

| CRGK39 | Saint Ignatius Parish | 3 |

| CRGK40 | Saint Joseph Artisan Parish | 20 |

| Cities | Specific Richness | Number of Families | Number of Genera | Area (ha) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | |

| Bukavu (n = 20) | 9.2a | 4.7 | 24 | 6.9a | 3.0 | 15 | 8.7a | 4.5 | 22 | 3.7a | 5.0 | 74.6 |

| Kisangani (n = 40) | 12.1a | 8.3 | 72 | 9.2a | 5.1 | 36 | 11.5a | 7.3 | 56 | 5.2a | 8.7 | 209.4 |

| Lubumbashi (n =10) | 24.1b | 10.8 | 152 | 17.9b | 7.5 | 60 | 23.7b | 10.6 | 137 | 1.1b | 2.5 | 11.4 |

| Cities | Taxa | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Family | Relative Dominance | |

| Bukavu (Rs = 24) | Bignoniaceae | 12.5% |

| Fabaceae | 12.5% | |

| Rutaceae | 12.5% | |

| Anacardiaceae | 8.3% | |

| Myrtaceae | 8.3% | |

| Rosaceae | 8.3% | |

| All others* | 4.2% | |

| Kisangani (Rs = 67) | Fabaceae | 15.3% |

| Moraceae | 9.7% | |

| Anacardiaceae | 5.6% | |

| Myrtaceae | 5.6% | |

| Rutaceae | 5.6% | |

| Lubumbashi (Rs = 152) | Araceae | 8.6% |

| Arecaceae | 7.2% | |

| Asparagaceae | 6.6% | |

| Genus | Dominance relative | |

| Bukavu (Rs = 24) | Citrus | 12.5% |

| All others* | 4.2% | |

| Kisangani (Rs = 67) | Acacia | 5.6% |

| Citrus | 5.6% | |

| Albizia | 4.2% | |

| Ficus | 4.2% | |

| Terminalia | 4.2% | |

| Lubumbashi (Rs = 152) | Cyperus | 2.0% |

| Euphorbia | 2.0% | |

| Tradescantia | 2.0% | |

| All others* | 1.3% |

| Cities | Taxa | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Species | Relative Frequence | |

| Bukavu (n =20) | Pinus patula Schltdl. & Cham., 1831 | 75.0% |

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill., 1800 | 70.0% | |

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck, 1765 | 65.0% | |

| Psidium guajava L., 1753 | 65.0% | |

| Mangifera indica L., 1753 | 60.0% | |

| Markhamia lutea (Benth.) K. Schum. | 60.0% | |

| Persea americana Mill., 1768 | 60.0% | |

| Kisangani (n =40) | Persea americana Mill., 1768 | 82.5% |

| Elaeis guineensis Jacq., 1763 | 75.0% | |

| Mangifera indica L., 1753 | 67.5% | |

| Lubumbashi (n=10) | Cordyline fruticosa (L.) A.Chev., 1919 | 80.0% |

| Musa acuminata Colla, 1820 | 60.0% | |

| Acalypha wilkesiana Müll.Arg., 1866 | 50.0% | |

| Carica papaya L., 1753 | 50.0% | |

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck, 1765 | 50.0% | |

| Codiaeum variegatum (L.) Rumph. ex A.Juss., 1824 | 50.0% | |

| Families | Relative Frequence | |

| Bukavu (n=20) | Myrtaceae | 90.0% |

| Anacardiaceae | 75.0% | |

| Bignoniaceae | 75.0% | |

| Pinaceae | 75.0% | |

| Rutaceae | 65.0% | |

| Kisangani (n =40) | Arecaceae | 85.0% |

| Lauraceae | 82.5% | |

| Fabaceae | 77.5% | |

| Lubumbashi | Asparagaceae | 100.0% |

| Arecaceae | 90.0% | |

| Euphorbiaceae | 90.0% | |

| Lamiaceae | 80.0% | |

| Genera | Relative Frequence | |

| Bukavu (n=20) | Pinus | 68.2% |

| Eucalyptus | 63.6% | |

| Citrus | 59.1% | |

| Psidium | 59.1% | |

| Kisangani (n =40) | Persea | 82.5% |

| Elaeis | 75.0% | |

| Mangirefa | 67.5% | |

| Lubumbashi (n=10) | Cordyline | 80.0% |

| Citrus | 60.0% | |

| Musa | 60.0% | |

| Acalypha | 50.0% | |

| Carica | 50,0% | |

| Codiaeum | 50,0% | |

| Dracaena | 50,0% | |

| Tradescantia | 50,0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).