Submitted:

20 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Summary

2. Data Description

2.1. Data Collection and Processing

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Specifications of Each Sample File

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Data Values Fluctuations

3. Methods

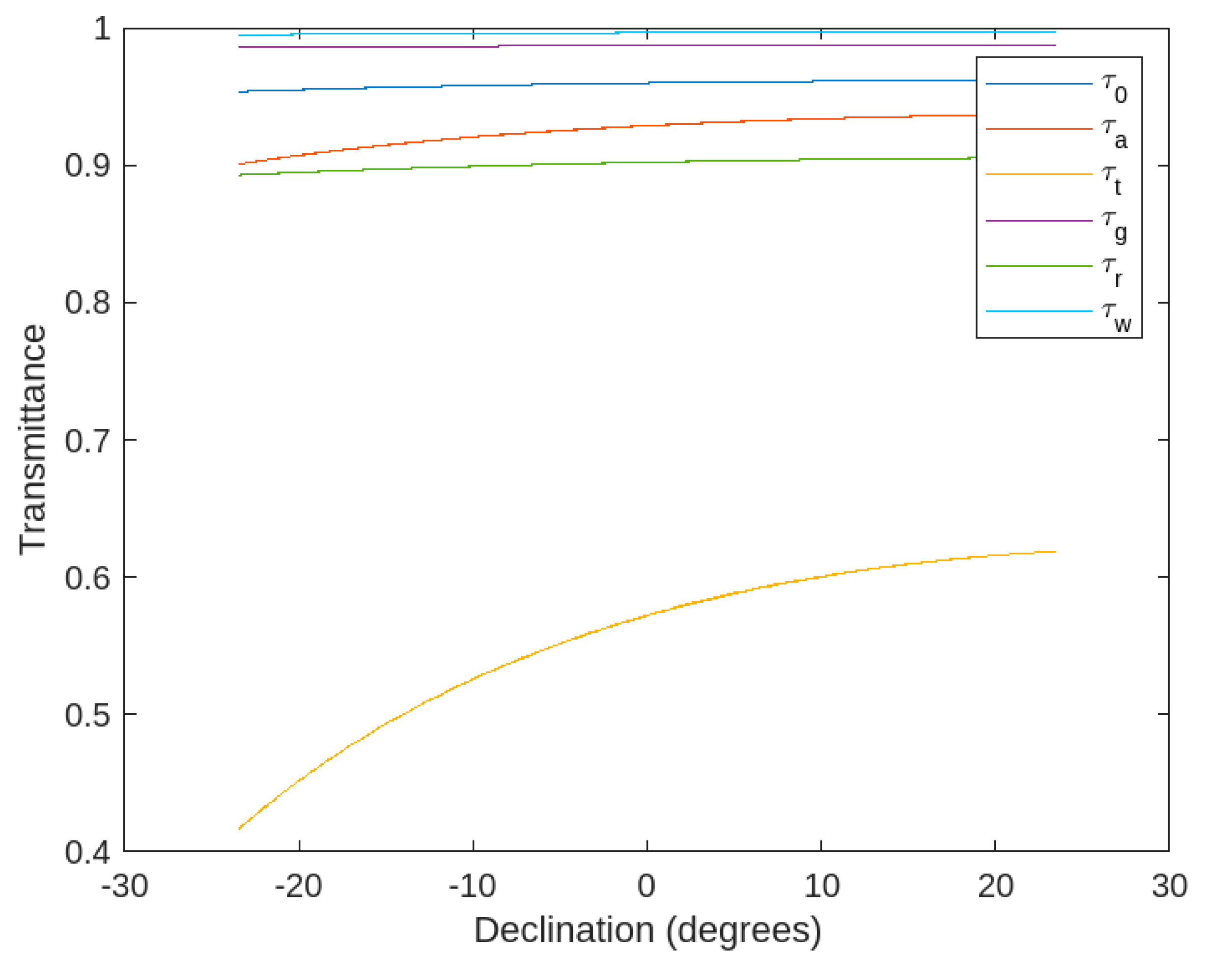

3.1. Clear–Sky Index

3.2. Process for Clustering

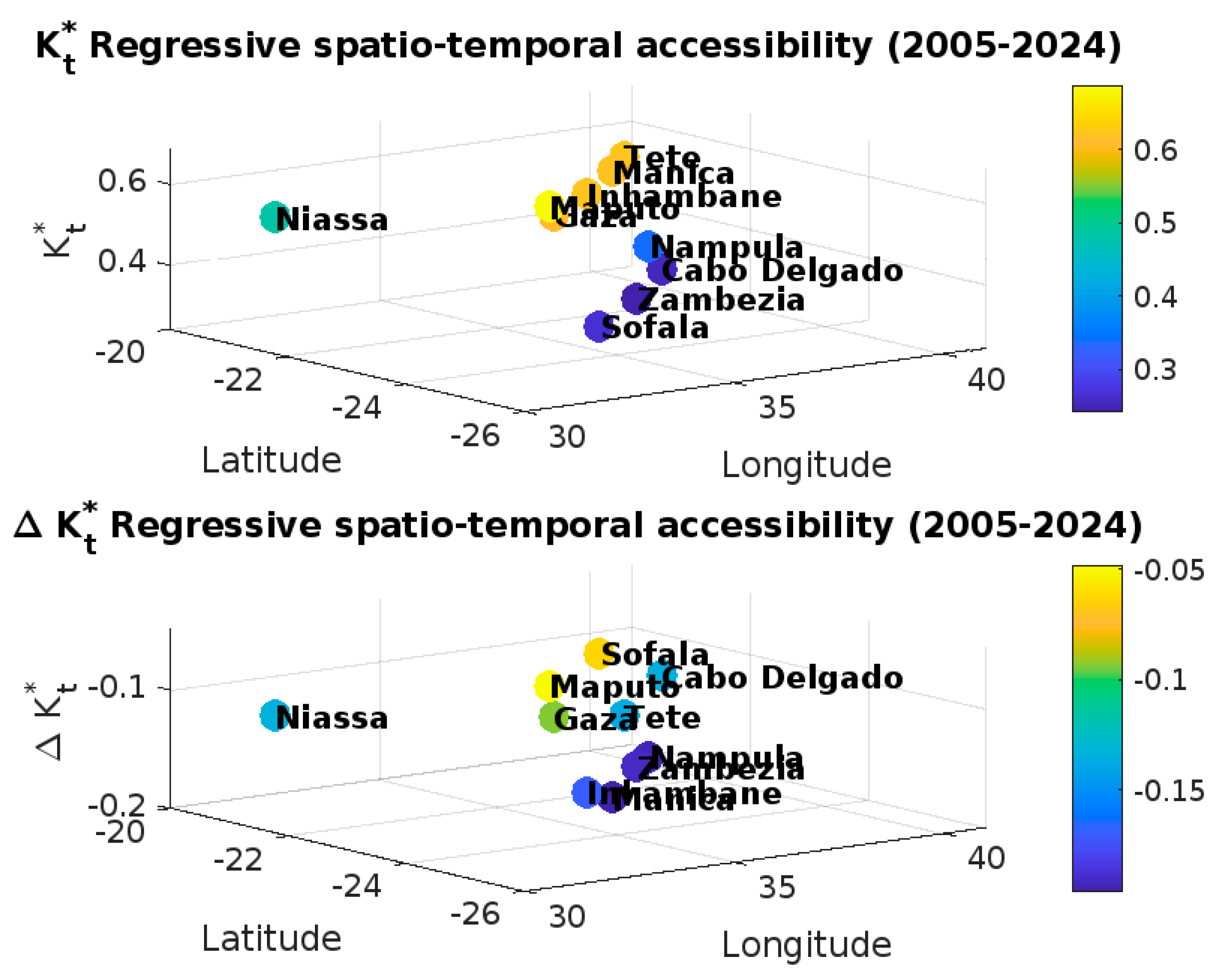

3.3. Regression and Correlation

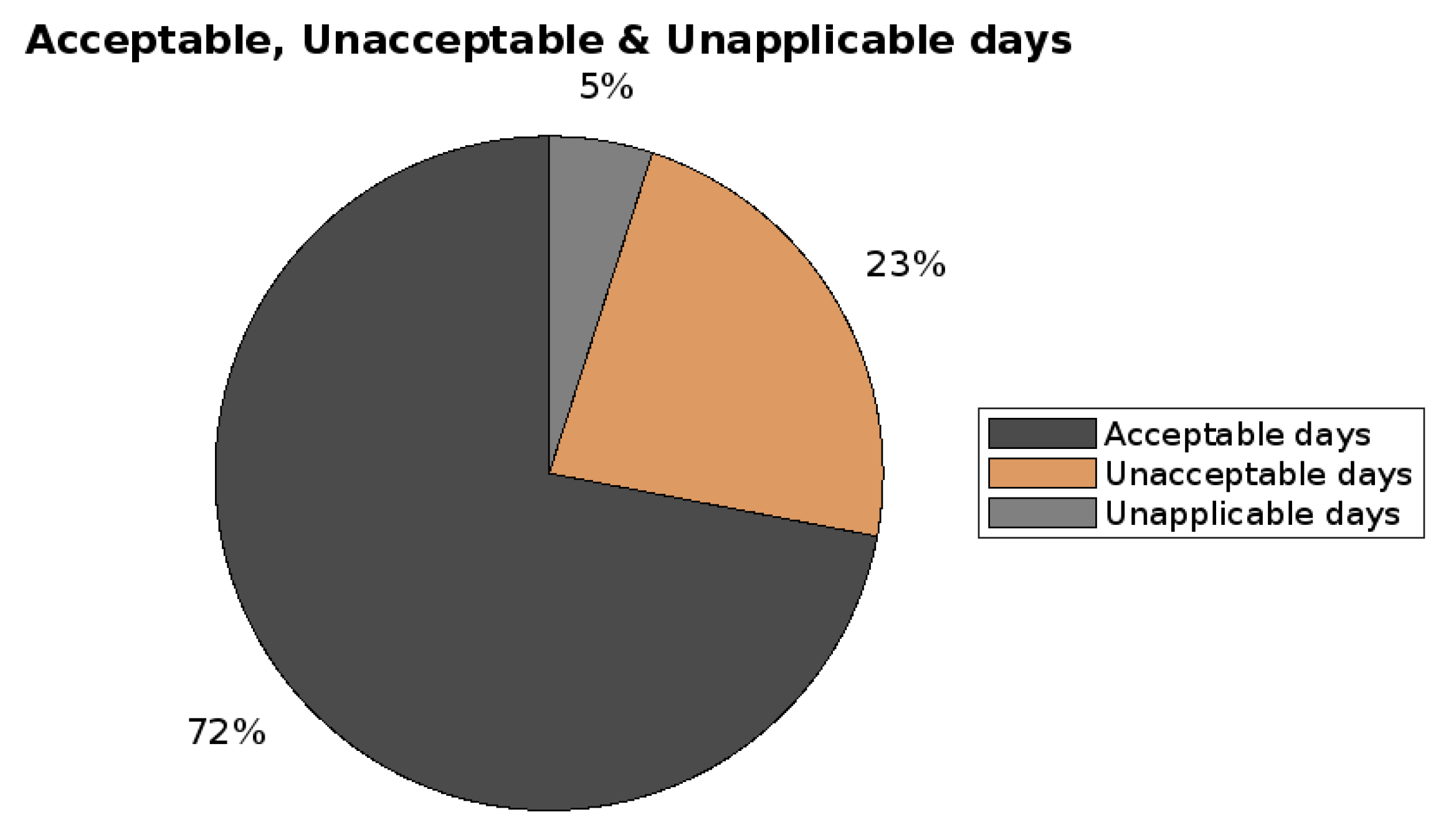

3.4. Validation and Data Curation

3.5. Noise in the Solar Energy and Quality Dataset

4. Usefulness and Applicability of the Solar Energy Dataset

4.2. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| − Clear-sky index; |

| – Clear–sky radiation; |

| – First quartile; |

| – Second quartile; |

| – Third quartile; |

| – Lower whisker; |

| – Upper whisker; |

| Apr – April; |

| Aug – August |

| Be_1 – Barue–1; |

| Be_2 – Barue–2; |

| Cha – Chipera; |

| CR23X – Campbell data logger; |

| CS–OGET – Center of Excellence of Studies in Oil, Gas Engineering and Technology; |

| CSV – Comma-Separated Values; |

| Dec – December; |

| DNI – Direct Normal Irradiance; |

| ePPI – Electronic Patient-Reported Performance Indicators; |

| Eq – Equation; |

| Feb – February; |

| FUNAE – National Energy Fund; |

| GHI – Global horizontal irradiance; |

| Id. or ID – Identification; |

| INAM – Mozambique National Institute of Meteorology; |

| IQR – interquartile; |

| kt*_C_A – Clear-sky index on clear sky acceptable days; |

| kt*_C_NA – Clear-sky index on clear sky unacceptable days; |

| kt*_Cy_A – Clear-sky index on cloudy sky acceptable days; |

| kt*_Cy_NA – Clear-sky index on cloudy sky acceptable days; |

| kt*_I_A – Clear-sky index on intermediate sky acceptable days; |

| kt*_I_NA – Clear-sky index on intermediate sky acceptable days; |

| VOS – Visualization of Similarities; |

| Δkt*_C_A – Clear-sky index increments on clear sky acceptable days; |

| Δkt*_C_NA – Clear-sky index increments on clear sky unacceptable days; |

| Δkt*_Cy_A – Clear-sky index increments on cloudy sky acceptable days; |

| Δkt*_Cy_NA – Clear-sky index increments on cloudy sky acceptable days; |

| Δkt*_I_A – Clear-sky–index increments on intermediate sky acceptable days; |

| Δkt*_I_NA – Clear-sky index increments on intermediate sky acceptable days. |

References

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1980.

- M. Iqbal, An introduction to solar radiation. Toronto ; New York: Academic Press, 1983.

- F. V. Mucomole, C. A. S. Silva, and L. L. Magaia, “Regressive and Spatio-Temporal Accessibility of Variability in Solar Energy on a Short Scale Measurement in the Southern and Mid Region of Mozambique,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 11, p. 2613, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Wenham, M. A. Green, M. E. Watt, R. Corkish, and A. Sproul, Eds., Applied Photovoltaics, 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. V. Mucomole, C. A. S. Silva, and L. L. Magaia, “Modeling Parametric Forecasts of Solar Energy over Time in the Mid-North Area of Mozambique,” Energies, vol. 18, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. V. Mucomole, C. A. S. Silva, and L. L. Magaia, “Experimental Parametric Forecast of Solar Energy over Time: Sample Data Descriptor,” Data, vol. 10, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hassan et al., “Evaluation of energy extraction of PV systems affected by environmental factors under real outdoor conditions,” Theor. Appl. Climatol., vol. 150, no. 1–2, pp. 715–729, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. A. J. Neggers, H. J. J. Jonker, and A. P. Siebesma, “Size Statistics of Cumulus Cloud Populations in Large-Eddy Simulations,” J. Atmospheric Sci., vol. 60, no. 8, pp. 1060–1074, Apr. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. J. R. Perez and V. M. Fthenakis, “On the spatial decorrelation of stochastic solar resource variability at long timescales,” Sol. Energy, vol. 117, pp. 46–58, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. E. Hoff and R. Perez, “Quantifying PV power Output Variability,” Sol. Energy, vol. 84, no. 10, pp. 1782–1793, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Lohmann, “Irradiance Variability Quantification and Small-Scale Averaging in Space and Time: A Short Review,” 2018.

- A. W. Aryaputera, D. Yang, L. Zhao, and W. M. Walsh, “Very short-term irradiance forecasting at unobserved locations using spatio-temporal kriging,” Sol. Energy, vol. 122, pp. 1266–1278, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Yu, H. Liu, J. Wu, and W.-M. Lin, “Investigating impacts of urban morphology on spatio-temporal variations of solar radiation with airborne LIDAR data and a solar flux model: a case study of downtown Houston,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 30, no. 17, pp. 4359–4385, Aug. 2009. [CrossRef]

- F. V. Mucomole, C. A. S. Silva, and L. L. Magaia, “Parametric Forecast of Solar Energy over Time by Applying Machine Learning Techniques: Systematic Review,” Energies, vol. 18, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Trindade and L. C. Cordeiro, “Synthesis of Solar Photovoltaic Systems: Optimal Sizing Comparison,” in Software Verification, vol. 12549, M. Christakis, N. Polikarpova, P. S. Duggirala, and P. Schrammel, Eds., in Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 12549. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 87–105. [CrossRef]

- A. Takilalte, S. Harrouni, M. R. Yaiche, and L. Mora-López, “New approach to estimate 5-min global solar irradiation data on tilted planes from horizontal measurement,” Renew. Energy, vol. 145, pp. 2477–2488, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. U. Obiwulu, N. Erusiafe, M. A. Olopade, and S. C. Nwokolo, “Modeling and estimation of the optimal tilt angle, maximum incident solar radiation, and global radiation index of the photovoltaic system,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 6, p. e09598, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Van Haaren, M. Morjaria, and V. Fthenakis, “Empirical assessment of short-term variability from utility-scale solar PV plants: Assessment of variability from utility-scale solar PV plants,” Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl., vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 548–559, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Koudouris, P. Dimitriadis, T. Iliopoulou, N. Mamassis, and D. Koutsoyiannis, “A stochastic model for the hourly solar radiation process for application in renewable resources management,” Adv. Geosci., vol. 45, pp. 139–145, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- FUNAE—National Energy Fund of Mozambique, Data on the solar radiation component extracted from the energy atlas. Available online: https://funae.co.mz/ (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- INAM—Mozambique’s National Institute of Meteorology, Weather and Solar Data. Available online: https://www.inam.gov.mz/index.php/pt/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- “JRC Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS) - European Commission.” Accessed: Apr. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/#MR.

- AERONET—Aerosol Robotic Network, Site Information Page, 2019. Available online: https://aeronet.gsfc.nasa.gov/new_web/webtool_aod_v3.html (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- “NOAA AVHRR derived aerosol optical depth over land - Hauser - 2005 - Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres - Wiley Online Library.” Accessed: Sep. 04, 2024. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- “Meteonorm Version 8 - Meteonorm (de).” Accessed: Apr. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://meteonorm.com/meteonorm-version-8.

- D. Kumar, “Hyper-temporal variability analysis of solar insolation with respect to local seasons,” Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ., vol. 15, p. 100241, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Perez et al., “Spatial and Temporal Variability of Solar Energy,” Found. Trends® Renew. Energy, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–44, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Verbois et al., “Improvement of satellite-derived surface solar irradiance estimations using spatio-temporal extrapolation with statistical learning,” Sol. Energy, vol. 258, pp. 175–193, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Amjad, S. Mirza, D. Raza, F. Sarwar, and S. Kausar, “A Statistical Modeling for spatial-temporal variability analysis of solar energy with respect to the climate in the Punjab Region,” vol. 7, p. 10, Mar. 2023.

- Wilson P. and Tanaka O. K., Statistics, Basic Concepts —Wilson Pereira/Oswaldo K. Tanaka, 2018. Available online: https://www.estantevirtual.com.br/livros/wilson-pereira-oswaldo-k-tanaka/estatistica-conceitos-basicos/189548989 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- F. V. Mucomole, C. A. S. Silva, and L. L. Magaia, “Temporal Variability of Solar Energy Availability in the Conditions of the Southern Region of Mozambique,” Am. J. Energy Nat. Resour., vol. 2, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. V. Mucomole, C. S. A. Silva, and L. L. Magaia, “Quantifying the Variability of Solar Energy Fluctuations at High–Frequencies through Short-Scale Measurements in the East–Channel of Mozambique Conditions,” Am. J. Energy Nat. Resour., vol. 3, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Marcos, L. Marroyo, E. Lorenzo, D. Alvira, and E. Izco, “Power output fluctuations in large scale pv plants: One year observations with one second resolution and a derived analytic model: Power Output Fluctuations in Large Scale PV plants,” Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 218–227, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Eduardo Mondlane University—Undergraduate, Postgraduate, Extension and Innovation (Department of Physics). Available online: https://uem.mz/index.php/en/home-english/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

| Files | Content | Interval | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| “daily_GHI_Chomba(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Nanhupo-1(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Nanhupo-2(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Nipepe-1(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Nipepe-2(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Chipera(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Nhamadzi(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Barue-1(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Barue-2(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Lugela-1(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Lugela-2(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Pembe(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Ndindiza(2005-2024)”, “daily_GHI_Massangena(2005-2024)” and “daily_GHI_Maputo–1(2005-2024)” | GHI measurements at the stations | 1, 10 minutes, and 1 hour | Input |

| “Chipera_A(2005-2024)”, “Nhamadzi_A(2005-2024)”, “Barue–1_A(2005-2024)” and “Barue–2_A(2005-2024)” |

data for acceptable days measured | 1, 10 minutes, and 1-hour | Output and input |

| “_accepted_unaccepted_unapplicable start with: “Barue_1_2005_2011”, “Barue_1_2012_2018” and “Barue_1_2014” they refer to the classification at the Barue_1 station in the years 2005 to 2024; by “Barue_2_2005_2011, “Barue_2_2012_2018” and “Barue_2_2019_2024” | acceptable, unacceptable and not applicable | 1 hour, and 1-hours | Output |

| Month | Acceptable Days | Unacceptable Days | Unapplicable Days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nr. | Id. | Nr. | Id. | Nr. | Id. | |

| January | 11 | 1, 17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31 | 20 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 27, 29 | 0 | None |

| February | 17 | 1, 3, 4, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, | 11 | 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 22 | 0 | None |

| March | 24 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 29, 30 | 7 | 10, 11, 16, 26, 27, 28, 31 | 0 | None |

| April | 25 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 | 4 | 11, 12, 5, 24, 25 | 0 | None |

| May | 28 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 | 3 | 18, 19, 20 | 0 | None |

| June | 22 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 22, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 | 8 | 10, 11, 12, 16, 18, 21, 23, 24 | 0 | None |

| July | 25 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31 | 5 | 6, 11, 18, 19, 30 | 0 | None |

| August | 15 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 | 16 | 1, 2, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, m29, 30, 31 | 0 | None |

| September | 14 | 4, 5,6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 | 15 | 1, 2, 3, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 29, 30 | 0 | None |

| October | 21 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 20, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31 | 8 | 1, 7, 14, 15, 17, 19, 23, 24 | 2 | 18, 28 |

| November | 19 | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 | 11 | 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 19, 22, 23, 24 | 0 | None |

| December | 15 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 13, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 | 16 | 6, 7, 8, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 29, 30, 31 | 0 | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).