1. Introduction

There are several different conditions that can affect the respiratory system- they can include airway diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema or asthma, occupational lung diseases such as asbestosis, autoimmune conditions such as vasculitis, interstitial lung diseases, infections involving bacteria, viruses or fungi and benign or malignant conditions. Whilst several diagnoses can be reached through histories and clinical examinations complimented by tests such as lung function tests or computed tomogram (CT) scans, occasionally a biopsy of a lesion is required. This can be achieved either via bronchoscopy, thoracoscopy or with the use of image guidance (on both pleural-based and parenchymal masses).

Our local population is predominantly Caucasian with a high smoking rate, and we have very high lung cancer prevalence [

1]. We serve a catchment area with a population of approximately 600,000 at Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. Our respiratory service thus has a huge burden of lung cancer and our services are geared to provide the required services. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide and most prevalent cancer worldwide in men [

2]. Incidence is expected to increase with the advent of lung cancer screening programs [

2,

3]. For individualised approaches to care and treatment planning, whether this is curative or palliative, pathological confirmation of the type of lung cancer

via a biopsy is often required. CT guided biopsies (CTGB) for parenchymal masses have high sensitivity and specificity and are thus common practice in the lung cancer diagnostic pathway [

3]. However, as with any procedure, complications occur, with pneumothorax being the commonest, with rates of up to 26% quoted [

4]. Previous meta-analyses have suggested that pneumothorax rates are increased with the use of needles greater than 18 Gauge[G] in diameter, the needle going through a fissure or through a bulla, the biopsy being done with more than 1 puncture and in non-coaxial fashion, with the presence of emphysema around the lesion and biopsying smaller lesions with no pleural contact at greater intrathoracic depths [

4].

Locally, in Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, all acute care is based at a flagship centre, the Northumbria Specialist Emergency Care Hospital and all CTGB are performed there by the radiologists, with post-biopsy management undertaken by the respiratory physicians. Typically, a chest radiograph is performed 4 hours after the CTGB to assess for pneumothorax (earlier if there is clinical concern), and if a pneumothorax is present, the respiratory physicians make the decision to intervene, admit or discharge with adequate safety nets. Fluoroscopy is performed. Image 1 and 2 show a typical CTGB of a lung mass being performed.

Practice around CTGB and subsequent pneumothorax management is very varied and resource dependent [

6]. The current British Thoracic Society guidelines for radiologically guided procedures and pleural disease have highlighted the lack of evidence to guide appropriate management of pneumothorax after CTGB [

7,

8]. It has been acknowledged that there is a need to conduct good quality research in this area to inform future treatment guidelines for standardized, evidence-based patient care. Thus, we sought out to perform a retrospective case note review of local CTGB induced pneumothorax with a view to understanding local practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Project registration

The project was registered as a service evaluation and was granted information governance clearance (C4453/4560) with no formal ethical approval required and waived informed consent.

2.2. Timeline

A list of all lung CTGBs for parenchymal masses from April 2011 to July 2023 was obtained from the radiology department.

2.3. Analysis

Simple demographics, radiographic and spirometric findings, pneumothorax rates, management strategies and outcomes were collected. All results were analysed descriptively and where possible, continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). All analyses were done in Microsoft® Excel, 2024 Edition.

3. Results

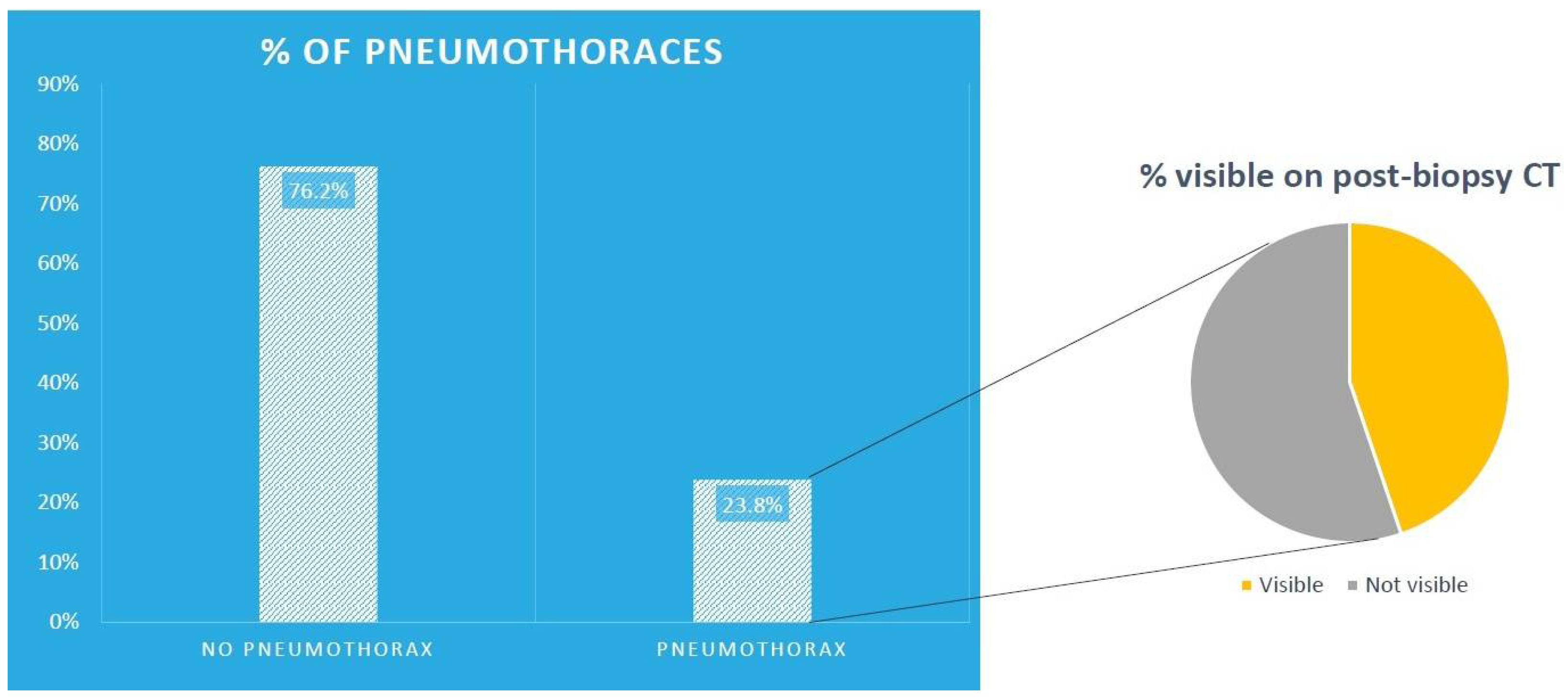

1492 CTGBs were performed during that period. The median age was 72 years (IQR 10.5) and 760 (50.9%) were male patients. There were 355 pneumothoraces (23.8%) overall with 159 (44.8%) of those being visible on the post biopsy CT images, as showed pictorially in

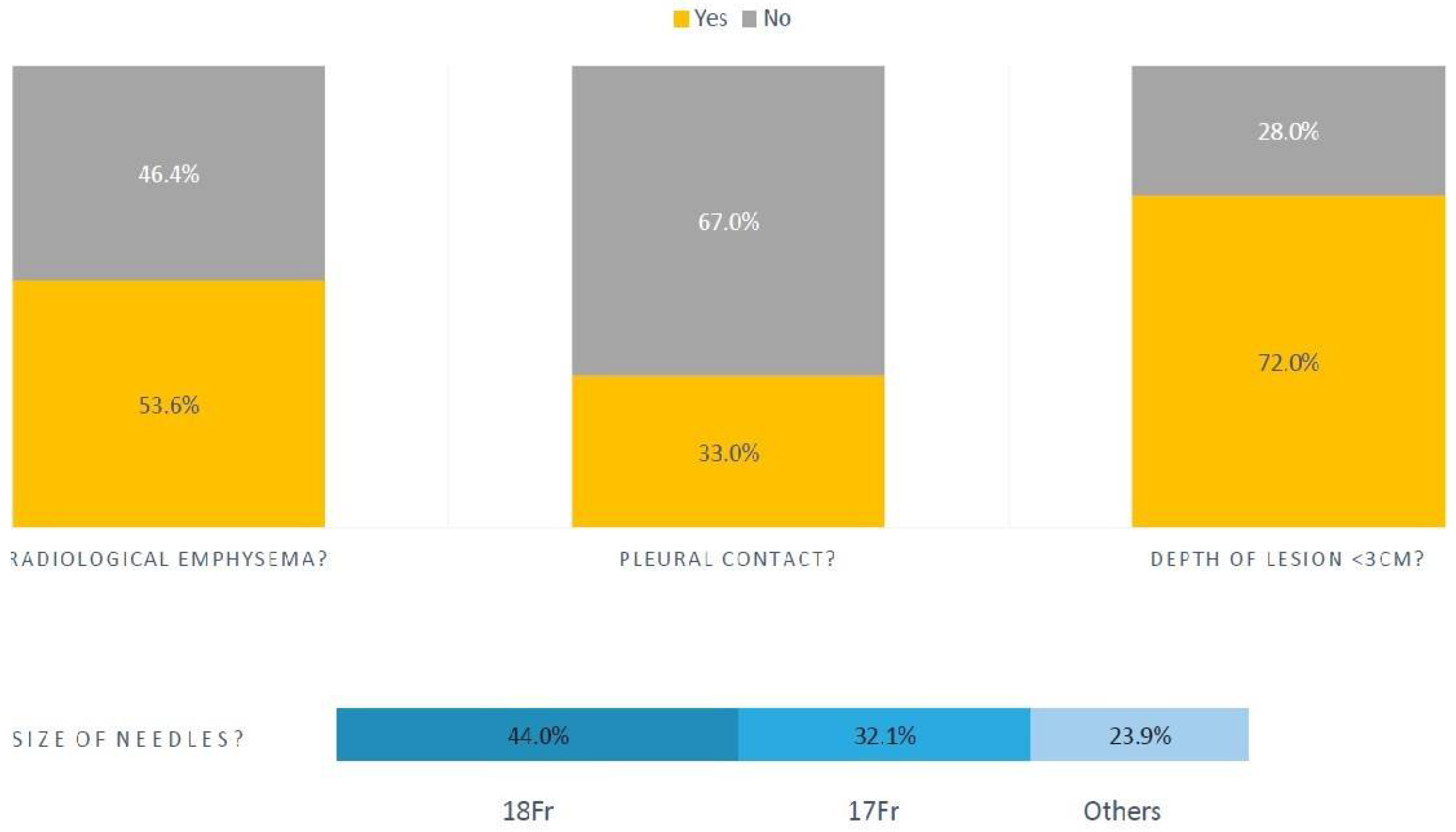

Figure 1. The mean number of pleural passes was 1.8 (range 1-4). Of the patients with pneumothoraces, 190 (53.6%) had radiological emphysema and median forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 1.97 litres (L) (IQR 1.04).

3.1 Pneumothoraces associated with CTGB

Of those with pneumothoraces, 234 (67%) of the lesions biopsied had no pleural contact, and 255 (72%) of those lesions were less than 3cm deep. The median size of lesion biopsied was 26 mm (IQR 24). In this same group, most biopsies were done with 18 French (Fr) gauge (44%) and 17Fr (32.1%) tru-cut needles, as shown pictorially in

Figure 2.

Of the 355 pneumothoraces, 315 (89%) pneumothoraces were managed conservatively. Of the 159 (44.8%) visible on the post biopsy CT images, 101 (63.5%) were asymptomatic. 143 (90%) had a chest radiograph between 2 to 4 hours later. 17 (12%) of those had a slight increase in the size of the pneumothorax, but no increase in symptoms. We do not measure the size of the pneumothoraces locally, instead using a symptom-based approach which we will discuss later. 333 (94%) of the patients had appropriate oxygenation levels for their respective ranges (locally 88-92% for those at risk of type 2 respiratory failure or with lung disease, and 90-95% for those without pre-existing lung disease, which is a slight adaptation from 94-98%) [

9]. The rest had transient hypoxemias (lowest value 85%), lasting less than 24 hours, which all resolved and were attributed to hypoventilation due to pain, in turn related to the biopsy procedure. Pain was treated with either paracetamol, codeine or liquid morphine.

3.2. Pleural interventions in patients with pneumothorax

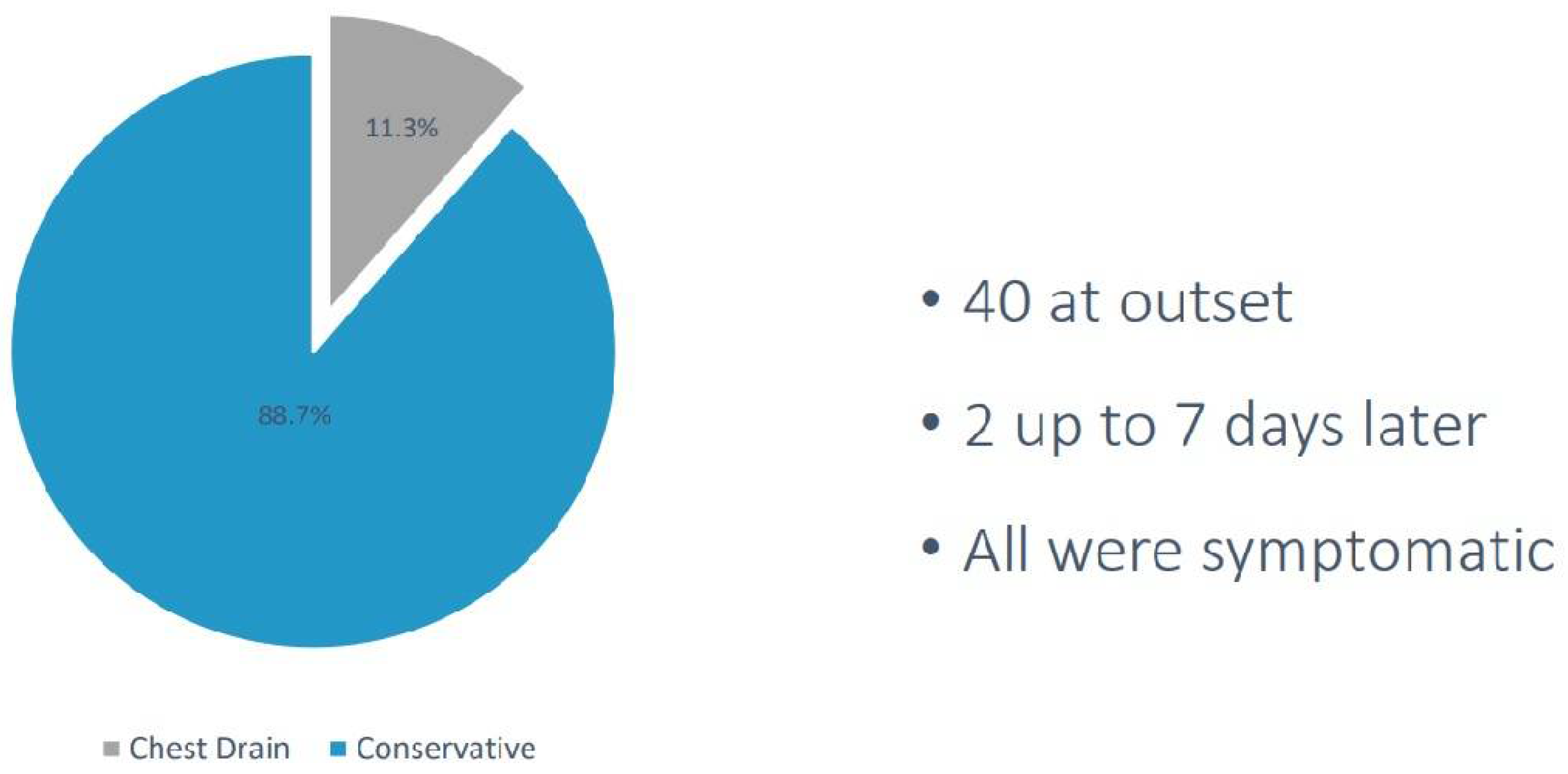

42 out of 355 patients (12%) had a pleural intervention (41 small bore, 12Fr intercostal chest drains were inserted and 1 one Rocket® Pleural Vent), as shown in

Figure 3. 40 had documented symptoms of increased breathlessness at the onset of pneumothorax either in the CT suite or developed them thereafter. 35 pneumothoraces resolved with small bore drainage, 7 required large bore drain insertion (20Fr in 2 and 24Fr in 5), and 2 required surgical cardiothoracic intervention.

Of note, there was a single case of mortality following CTGB within the dataset. A male who had no pneumothorax visible on post-biopsy CT images, nor on his 4-hour post-biopsy chest radiograph, developed progressive breathlessness a few hours later, and subsequently collapsed and had a cardiac arrest.

Despite paramedic-assisted resuscitation, he unfortunately died of a tension pneumothorax, which was proven on post-mortem - the death was attributed to a delayed presentation of a CTGB induced pneumothorax. His pre-biopsy FEV1 was 2.1 L (110% predicted), the lesion biopsied was 2 cm deep, and 2 passes were performed with an 18Fr needle. No fissures were crossed and there was only minor radiological emphysema around the lesion.

4. Discussion

Our retrospective analysis shows that pneumothoraces due to CTGB are common and can be expected in 25% of all patients undergoing CTGB. Pneumothoraces are commoner when biopsying smaller lesions with no pleural contact and with surrounding radiological emphysema. Most of the biopsies associated with pneumothorax were on lesions less than 3cm deep and most were done with smaller calibre needles, perhaps suggesting that surrounding radiological emphysema is more contributory. FEV1 does not seem to have a bearing on the risk of pneumothorax for CTGB.

The main message to get across is that the vast majority of pneumothoraces can be observed and managed conservatively. We have previously presented data showing even large pneumothoraces secondary to CTGB can be safely observed [

10]. This concept has been strengthened by large trials in primary pneumothoraces and extrapolated to the CTGB population [

11,

12,

13]. Self-sealing of the lung from a CTGB insult is thought to be due to the recoil properties and collapsibility of the lung which allows quick close of any alveolar-pleural connection. We have experimented with ambulatory devices, as emergent data has suggested that they are safe in CTGB pneumothoraces, but the risk of big air leaks in patients with underlying lung diseaseled us to abandon this practice [

11,

12,

13].

Our study has some significant limitations - we do not have a control group of those patients without pneumothorax to compare, so as a single arm retrospective study, the generalisability of the results is questionable, and we did not attempt any statistical inferences. We also did not look at other complications of CTGB, overall diagnostic sensitivity, nor co-axial or core needle techniques.. The single case of mortality within the dataset was not felt to have been preventable. We also did not look at the type of lesion being biopsied (ground glass or solid or subsolid) to see if that had any bearing on pneumothorax occurrence.

Practice around the United Kingdom (UK) is very varied [

6]. Tavare et al surveyed UK practice in 2017. 30.1% (72/239) of survey respondents did not require pre-biopsy lung function testing. 55.9% of radiologists did 1 or 2 passes, and 40.8% 3 or 4 passes. 64% used the so-called chest drain prevention techniques – with 43.9% using needle aspiration. Other methods can include the roll-over technique, saline injection into the biopsy track, and the use of hydrogel plugs or blood patches. We did not look at these techniques within this study. The timing of post-biopsy chest radiographs also varied, with23% performed at 1 hour, 24.7% at 2 hours and 22.6% at 4 hours. There is also a lack of standardization amongst centres, and thoracic surgery is often required for those lesions where CTGB is non-diagnostic, although exact figures are lacking. We also did not look for previous smoking habit (as this was very poorly documented) or other respiratory co-morbidities, and this is another limitation of our study.

We are currently participating in the Pneumothorax after Lung Biopsy: Understanding the Management Basis (PLUMB) study which is being run in the United Kingdom and is collecting all of the data we have not (Ethics Reference 24/NI/0111 and Integrated Research Application System Project Identification 331451) [

15].

Delayed pneumothorax has also been described in the literature, at a population-based estimate of less than 1% [

14], which is what we saw in our single case of mortality in this dataset.

Another point should be made regarding our oxygen parameters. We agree that target saturations should be 88-92% in all patients with COPD and other conditions at heightened risk of oxygen toxicity. In patients receiving oxygen in the study by Echevarria et al, the lowest mortality was in those with sats 88-92%, including the cohort with normocapnia [

9]. There was an adverse dose response of oxygen therapy at higher saturations, and the relationship was stronger, not weaker, after adjusting for baseline risk. Local expert opinion has settled with a range of 90-95%, as the upper threshold lies between 94% and 96%, which are the two upper values suggested.

As formal randomised controlled trials on how to prevent complications such as pneumothorax are not available, the evidence stems from meta-analyses and retrospective reviews. Nakamura et al suggest a host of factors to reduce pneumothorax rates such as using small gauge needles, trying not to biopsy central or deep lesions with surrounding radiological emphysema, and not doing multiple pleural passes for example [

16]. Heerink et al similarly analyzed 32 articles and 8,133 procedures, finding that larger needles caused more complications, alongside traversing a large amount of parenchyma and biopsying smaller lesion sizes [

17]. Moad et al reported similar findings but also that the FEV1 did not a bearing on pneumothorax occurrence [

18].

5. Conclusions

Until there are adequately powered randomised controlled trials looking at the various aspects of CTGB and ultimately pneumothorax management with patient centred outcomes at their core, regular analyses of large volume centres are important. Whilst the data is often incomplete and laden with limitations, they can inform local practice as we have done here. The widespread variation in practice also calls for a standardised approach which can only succeed with radiology and respiratory societies working together collaboratively and on an international level.

Author Contributions

Jebelle Sutanto1, Grace Musell1, Daniel Mitchell1, Wei Ong1, Avinash Aujayeb1 all wrote the article, and revised the manuscript for content. All agree to the final version. All the authors performed data collection, Avinash Aujayeb performed the data analysis.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this.

Institutional Review Board Statement

(C4453/4560) Northumbria Healthcare Foundation Trust.

Informed Consent Statement

As this was a retrospective review, there was no required for informed consent from the participants.

Data Availability Statement

Some of the data will be available with reasonable requests.

Conflicts of Interest

Avinash Aujayeb is part of the Editorial team for Journal of respiration, but was not involved in peer reviewer selection. None of the other authors have anything to declare.

References

- Rate of newly diagnosed cases of lung cancer per 100,000 population in England in 2020, by region and gender. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/312896/lung-cancer-cases-rate-england-region-gender/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Lung cancer. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer#:~:text=GLOBOCAN%202020%20estimates%20of%20cancer,deaths%20(18%25)%20in%202020 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Hardavella, G.; Chorostowska-Wynimko, J.; Blum, T.G. Lung cancer: An update on the multidisciplinary approach from screening to palliative care. Breathe (Sheff). 2024, 20, 240117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.R.; Chan, M.V.; Habib, A.R.; Lui, I.; Ridley, L. Pneumothorax rates in CT-Guided lung biopsies: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors. Br J Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northumbria Specialist Emergency Care Hospital. 2024. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Northumbria_Specialist_Emergency_Care_Hospital&action=history (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Tavare, A.N.; Hare, S.S.; Miller, F.N.A.; Hammond, C.J.; Edey, A.; Devaraj, A. A survey of UK percutaneous lung biopsy practice: Current practices in the era of early detection, oncogenetic profiling, and targeted treatments. Clin Radiol. 2018, 73, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manhire, A.; Charig, M.; Clelland, C.; Gleeson, F.; Miller, R.; Moss, H.; et al. Guidelines for radiologically guided lung biopsy. Thorax 2003, 58, 920-36.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.E.; Rahman, N.M.; Maskell, N.A.; Bibby, A.C.; Blyth, K.G.; Corcoran, J.P.; et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echevarria, C.; Steer, J.; Wason, J.; Bourke, S. Oxygen therapy and inpatient mortality in COPD exacerbation. Emerg Med J. 2021, 38, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avinash Aujayeb Parag Narkhede Pneumothorax rates after CT guided biopsy: Experience from a high volume cancer centre. European Respiratory Journal 2021, 58 (suppl 65), PA3784. [CrossRef]

- Chopra, A.; Judson, M.A.; Rahman, N.M.; Doelken, P. The lung is not a balloon: The self-sealing property of the lung. Lancet Respir Med. 2024, 12, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, M.; Babu, S.; Wallis, A.; Asciak, R. Promising role for pleural vent in pneumothorax following CT-guided biopsy of lung lesions. Br J Radiol. 2022, 95, 20210965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.P.; Keenan, E.; Bintcliffe, O.; et al. Ambulatory management of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax: A randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2021, 57, 2003375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pua, B.; Tang, E.; Bhat, A.; et al. Delayed pneumothorax after percutaneous lung biopsy in the state of California. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2016, 27, S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PLUMB (Pneumothorax after lung biopsy: Understanding the management basis). Available online: https://www.inspirerespiratory.co.uk/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Nakamura, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Inoue, C.; Matsusue, E.; Fujii, S. Computed Tomography-guided Lung Biopsy: A Review of Techniques for Reducing the Incidence of Complications. Interv Radiol (Higashimatsuyama) 2021, 6, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerink, W.J.; de Bock, G.H.; de Jonge, G.J.; Groen, H.J.; Vliegenthart, R.; Oudkerk, M. Complication rates of CT-guided transthoracic lung biopsy: Meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2017, 27, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moad, M.; Narkhede, P.; Jackson, K.; Aujayeb, A. A note on pneumothorax post-CT-guided biopsy. Br J Radiol. 2021, 94, 20201010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).