2. Mathematical Framework

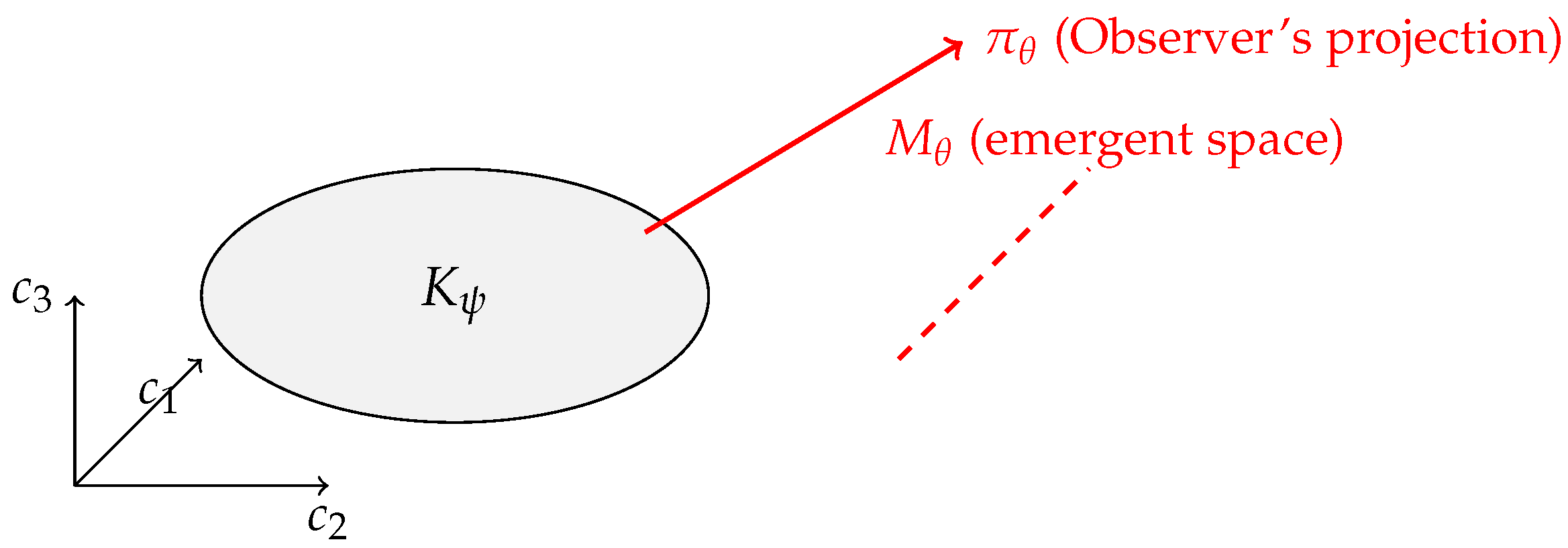

In this section we translate the axioms into a concrete mathematical construction. We define the correlationhedron more formally, describe how an observer’s projection produces an effective spacetime manifold, and derive an emergent metric on that manifold.

To formalize this slicing process, we introduce the notion of an observer projection:

Definition 2.1 (Observer Projection)

. An

observer projection is a smooth map from the full correlation structure

to a lower-dimensional manifold

, representing the effective spacetime experienced by an observer

. Formally,

This map selects the subset of observable correlations accessible to the observer, typically by restricting to a subalgebra

. The image

inherits coordinates corresponding to expectation values of observables in

, and geometric structure is induced via correlation densities on

.

2.1. Correlationhedron Definition and Convexity

Let

be the Hilbert space of a closed quantum system described by the wavefunction

(or a density matrix

for a pure state, generalizable to mixed states). We define the

correlation space as the space of all possible correlation vectors

that can be constructed from expectation values of products of observables on the system. Each

is of the form:

for some choice of

N observable pairs

(these could be, for example, all distinct pairs of a chosen operator basis on

). Not all vectors in

are allowed; only those obeying quantum constraints (linearity, positivity, etc.) correspond to a physical state.

For a specific state

(or

), we define the

correlationhedron:

In words,

is the set of all correlation vectors attainable by the system when it is in the state

(allowing variation over different measurement contexts or decompositions but not over different states) [

18]. By construction, each

arises from a positive semi-definite

(Axiom A2), hence

is a convex set [

19].

This convexity follows directly from the linearity of expectation values in

. For any two states

and

,

so any convex combination of correlation vectors remains in

.

In this paper, for concreteness, we restrict correlation vectors to include all two-point correlators drawn from a chosen operator basis on . Extensions to higher-order and temporal correlations, while straightforward in principle, are deferred to future work.

The term “hedron” highlights that

is a geometric object (indeed, typically a convex polytope or a curved convex body) in the high-dimensional space of correlations. This construction is reminiscent of the

amplituhedron in particle physics [

20], which is a convex geometric object encoding scattering amplitudes. Likewise,

encodes quantum correlation data in a single geometric entity.

can be thought of as living in a high-dimensional space, whose dimensionality is determined by the number of independent correlation components one considers. In practice, symmetries or selection of particular observable sets can reduce this dimensionality. For example, for a system of many qubits, one might consider the set of all two-point correlators (with labeling qubits and Pauli components). The collection of these for all gives a correlation vector. The set of all such vectors physically achievable by a given would form . By Axiom A1, is assumed to capture all relevant correlations of the state.

Concretely, given an observer whose accessible observables are

, the projection map

acts by selecting the subvector

where

indexes the observables available to that observer. Thus

is the restriction of correlation vectors to the observer’s measurement subspace.

This construction may be viewed as a vast generalization of the classical correlation polytope studied in quantum foundations. In particular, Pitowsky’s Bell-scenario polytope characterizes the set of all joint probability assignments compatible with local hidden–variable models [

21], and the Tsirelson bounds constrain its quantum-mechanical analogue by imposing operator-positivity and commutation relations [

22]. By contrast, the correlationhedron

encompasses

all two-point—and, in principle, higher-order and temporal—correlations arising from a single global state

. Whereas the Bell polytope is carved out by linear constraints on measurement outcomes in a fixed spacelike configuration,

is defined by the full family of operator covariance relations,

and is automatically convex by positive-semidefiniteness of the density operator. Moreover, by allowing

to come from different times—as in temporal correlations à la Leggett–Garg—this framework extends beyond the purely spatial scenarios of Bell tests, yielding a unified geometric object for arbitrary observables and spacetime orderings.

In the following sections, we first explore how an observer’s projection gives rise to an emergent spacetime (

Section 2.2), then formalize the mathematical structure and admissibility conditions of these projections (

Section 2.3), and finally derive how such projections yield a geometric structure (

Section 2.4–2.6).

2.2. Examples and Intuition for Observer Projections

While

represents the totality of correlations in the quantum state, an observer can only access a subset of this information. We model the perspective of a given observer by an

observer projection mapping

which takes the full correlationhedron and produces a lower-dimensional “shadow” of it on an effective manifold

[

12]. Here

is a manifold (with dimension

d typically much smaller than that of

) that the observer interprets as their physical space and time. We furthermore assume

(three spatial coordinates plus one time coordinate). In practice, Axiom A4 (locality emergence) and Axiom A6 (entanglement–time duality) guide the choice of observables so that

can be interpreted as a classical 3+1-dimensional spacetime for the observer. The parameter

denotes the observer’s state (for example,

could encode the observer’s velocity, orientation, choice of measurement basis, or other contextual information).

If the observer’s subalgebra

has a nondegenerate reduced state

and its expectation values vary smoothly with the global state

, then there exists a smooth projection map

whose Jacobian has full rank almost everywhere on

.

In general, will be a many-to-one map (different points in may look identical to a given observer if they cannot be distinguished by that observer’s measurements). A simple example of a projection is to marginalize over (i.e. ignore) certain correlation components. For instance, an observer might be sensitive only to two-point correlations among a subset of particles, and blind to higher-order correlations or correlations involving other distant particles. In that case, could be a linear projection picking out those two-point correlators from the full vector . Another example: if the observer moves at high velocity, their notion of simultaneity changes (relativistic time dilation), which in this framework could correspond to a different slicing through correlation time-orderings in .

Importantly,

should be chosen such that the image

inherits meaningful coordinates interpretable as space and time for the observer. (One might need additional structure to define a metric or geometry on

, but we address that shortly.) There may not be a unique way to choose

— indeed, there are many possible ways to define an observer’s slice[

23]. However, Axiom A3 demands that some consistent projection exists for any valid observer.

Clarification (Examples of ): To build intuition, consider two extreme cases of projections. At one extreme, an “ideal” observer with access to all degrees of freedom would have as the identity on , recovering the full structure (and thus presumably a high-dimensional, highly curved space). At the other extreme, a very limited observer who can only measure one variable might map to a 1D manifold (just the expectation value of that variable), losing most of the structure. Realistic observers lie in between, projecting out some but not all information. The choice of can be dynamic — for instance, an accelerating observer might effectively change their projection over time.

While multiple distinct projections can map to observationally equivalent spacetimes, any physically relevant distinction must be empirically accessible through measurement outcomes.

2.3. Mathematical Structure of Observer Projections

Let be the Hilbert space of the quantum system with global state (or pure state ). Let be the full observable algebra on , and let be the subalgebra accessible to an observer labeled by parameter .

Define the space of two-point correlators:

Define the

correlationhedron for a fixed state

as:

We model an observer’s emergent spacetime

via a projection map:

where

selects a subvector of correlators

for some finite index set

.

Definition (Admissible Projection): A projection is admissible if it satisfies:

1. Positivity Preservation: is positive semidefinite. 2. Smoothness: is at least smooth on , i.e., all derivatives up to second order exist. 3. Full Rank: The Jacobian of has full rank almost everywhere.

Proposition: If is a -smooth density operator and is finite-dimensional with smooth matrix elements, then is admissible.

2.4. Emergent Metrics from Correlation Densities

Given a particular observer’s projected manifold

, we must define how this manifold inherits a notion of distance or metric from

. A natural approach is to introduce a

correlation density on

that captures how densely correlations from

map to different regions of

.

Note that

so one may equivalently write the metric as

See Appendix A.2 for a detailed discussion of this sign convention. By construction, the emergent metric

is positive-definite, thus defining a

Riemannian metric on

. This guarantees all observer-defined distances are real; the conditions for the emergence of a Lorentzian signature (with light-cone structure) will be sketched below. The emergent metric

encodes the curvature of the effective spacetime manifold through variations in the density of correlations. Regions of steep changes in correlation density correspond to higher curvature. Here

is the density induced on

by projecting the natural volume on

through

, so that

equals the volume of its preimage in

.

This coincides with the Fisher information metric on the statistical manifold defined by (see Appendix A.2 for derivation).

Intuitively, if a particular region of corresponds to many distinct points in (i.e., many different underlying correlation configurations look the same to the observer), then in that region is high. Conversely, if very few configurations project to a region, is low.

From

, we can recover the emergent metric tensor

on

((see Eq. (

2)), which is analogous to the Hessian of the negative log density [

24]. Equivalently,

is the Fisher-information metric tensor if we treat

as defining a statistical manifold. This choice ensures several desirable properties:

It is manifestly observer-dependent. Different yield different and thus different metrics. This aligns with the idea that geometry is not absolute but tied to the observer’s slicing of correlations.

It is positive-definite (so long as in the neighborhood, ensuring no singular behavior in the log-density). This means distances computed from are real.

It responds to correlation gradients: regions where changes rapidly will have a large curvature (as second derivatives are large), while flat regions of give flat geometry.

A key requirement for to serve as a Riemannian metric is that it be nondegenerate (invertible) everywhere on . This will be true if is smooth and nowhere vanishing on (or more precisely, may approach zero but not be identically zero in a patch, so that is well-behaved). In practice, might be very small or zero in some regions if certain correlation configurations are impossible or extremely unlikely for a given . In those cases, the metric may become singular, signaling an “edge” to the observer’s spacetime (beyond which no points from map). Physically, this could correspond to horizons or singularities from the observer’s perspective, beyond which their measurements cannot probe.

This emergent metric encapsulates how the observer perceives distances in their space in terms of underlying correlation configurations. If is uniform, is zero (flat space) – meaning the observer sees no curvature, as every region of their space corresponds to equally many underlying configurations. If is sharply peaked in one area and shallow in another, will vary across , indicating curvature (the observer might interpret that as a gravitational field or tidal force in their space). In essence, areas of high correlation density act like “mass” – they pull the geometry tight (high curvature), whereas sparse regions act like voids (flat or even effectively negative curvature in a relative sense if we allowed an analogy to negative mass).

2.5. Conditions for Lorentzian Signature

While this emergent metric is initially Riemannian (positive-definite), the structure naturally generalizes to include time-like directions and causal ordering. In particular, a Lorentzian signature may arise by partitioning correlation density into temporal and spatial components. This provides a bridge between statistical curvature and relativistic geometry. To obtain a pseudo-Riemannian metric with one time-like direction, one can split the projection into clock and spatial pieces:

then define:

This yields a

signature (when

and

satisfy differentiability and positivity conditions), consistent with the standard Lorentzian structure of spacetime, while the underlying correlation space

remains positive-definite. The negative sign associated with the temporal derivative reflects the causal distinction between time-like and space-like directions, ensuring that the emergent geometry preserves conventional causal structure. We leave the explicit construction of such a projection to future work.

In practice, identifying and depends on the observer’s clock–system decomposition or symmetry properties of the state, as discussed in relation to Axiom A6 and the Page–Wootters construction. This decomposition presumes that observer-accessible correlations can be naturally partitioned into temporal and spatial sectors, such as when the clock–system factorization is approximately valid or when the state exhibits symmetry under time translations. In principle, regions where the sign of the log-derivative flips could signal transitions between Riemannian and Lorentzian character—an idea reminiscent of signature change in certain quantum cosmological models.

2.6. Curvature and Observers’ Perspectives

How does this formal emergent curvature relate back to known physics? If is indeed to be interpreted as an observer’s spacetime, then variations in should mimic gravitational effects for that observer. In our construction, steep gradients in play the role of energy density in general relativity, curving . For example, if has a pronounced peak (indicating a cluster of correlations concentrated in one region of ), the Hessian will be large there, meaning a strong curvature. An observer might interpret that as a massive object creating gravitational attraction in that region. Conversely, if is nearly flat, is nearly flat.

We emphasize that this metric is emergent and state-dependent. Change the quantum state , and changes, changes, and thus the geometry on changes. This provides a concrete implementation of the idea that spacetime (and its curvature) is not fundamental, but arises from the quantum state’s correlations.

To draw a parallel, consider how in the AdS/CFT correspondence entanglement entropy in the boundary theory relates to the geometry of the bulk spacetime (via the Ryu–Takayanagi formula). In our framework, is a more fine- grained object than entropy – it’s a distribution capturing the full spectrum of correlations, not just the entropy. Yet it plays a somewhat analogous role, dictating the emergent geometry. Where AdS/CFT uses minimal surfaces to probe bulk geometry (with areas corresponding to entropies), here we use correlation densities to directly shape the metric. Importantly, our approach does not assume any pre-existing spacetime such as AdS; it applies to an arbitrary state .

Finally, one might wonder: do all choices of lead to a reasonable geometry? Perhaps not. Some projections might yield a highly singular or otherwise pathological metric. In such cases, the resulting fails to be a well-defined differentiable manifold. This is not unexpected – not every arbitrary slicing of correlations will correspond to a semi-classical spacetime. The hope, however, is that for “natural” choices of observables (the kind an actual physical observer might have access to), will be well-behaved. In the Appendix A.1, we discuss some conditions for the existence and smoothness of and how to handle cases where the emergent metric might become degenerate or singular.

In summary, the emergent metric on provides the observer’s “gravitational field”: it tells them how their space stretches or compresses in different regions as a function of the underlying quantum state’s correlation distribution. Curvature in this space is directly tied to inhomogeneities in – which are, in turn, features of ’s correlation structure. Thus, in our approach, gravity is nothing but the second derivative of the log correlation density: a statement that is reminiscent of, but more general than, entropic gravity proposals.

We will next illustrate these ideas with simple toy models, to see explicitly how entanglement (or lack thereof) in leads to a particular and for an observer.

We now extend the static picture by considering how a time-evolving quantum state induces a trajectory through the correlation space , leading to a time-dependent emergent geometry for the observer.

2.7. State Trajectories and Time-Dependent Correlation Geometry

So far, we have focused on static correlations and emergent geometry from a fixed state. In this section, we explore how time-evolving quantum states induce dynamics on the emergent manifold.

Let the global state

evolve unitarily:

for some Hamiltonian

H. Then

is a time-dependent convex set.

Let

be the time-dependent correlation density on

defined by:

where

is a measure on

and * denotes the pushforward.

Define the emergent metric at time

t by:

Then the emergent Ricci tensor can be written as:

These curvature terms may include mixed partial derivatives or non-Hessian contributions, depending on the underlying geometry of .

We conjecture a dynamical law:

where

is a functional of

and its derivatives, acting as an effective energy-momentum tensor from quantum correlations.

3. Conceptual Toy Models

To build intuition, we examine a few toy models that illustrate how the abstract machinery of the correlationhedron and observer projections works in simple settings. These examples highlight how locality, curvature, and entanglement– time duality manifest in concrete quantum systems.

3.1. Single-Qubit Temporal Correlations

Our first toy model is a single qubit (two-level quantum system) observed over time. Even though a single qubit has no spatial extent, it can illustrate the entanglement–time duality (A6) in a trivial setting by considering correlations in time.

Consider a qubit initially prepared in state and then measured at two different times (by the same observer). The correlationhedron in this case could be taken as the set of all two-time correlation values for observables at times and . If the qubit’s Hamiltonian is H, its state evolves as . Suppose the observer measures at time and at time . We can talk about a correlation which will depend on the initial state and the time difference . In this simple case, might be one- dimensional (since essentially one parameter controls the correlation).

According to our framework, the observer (here implicitly at rest relative to the qubit) projects onto a 1D manifold which we can identify with the time axis itself.

The correlation density on this time axis could be related to how correlation varies with . For example:

If

is an eigenstate of

, then

so

is uniform (flat emergent time).

If

is a superposition, then

giving a peaked

near

that decays for larger

. The emergent metric

then varies, producing segments of different “length.’’

The main takeaway from the single-qubit example is that even temporal correlations of a single degree of freedom can be seen as defining an emergent time dimension. The entanglement–time duality is trivial here (no entanglement since one qubit, but the role of correlation in time is analogous to entanglement in space for larger systems). This sets the stage for considering space and time on equal footing as two ways of slicing correlation structures.

3.2. Two Qubits: Entangled vs. Separable

A more illuminating toy model is a two-qubit system, which we can use to explicitly demonstrate how entanglement generates curvature in the emergent geometry (A5) and how locality emerges (or fails to) depending on the state.

For our two qubits (call them A and B), consider two extreme initial states:

A separable state, e.g. , which has no entanglement between qubits A and B.

An entangled state, e.g. the Bell state , which possesses maximal entanglement between A and B.

We will examine each case through the lens of our framework, determining on an appropriate and the resulting curvature.

For simplicity, let us define our observer’s projection such that captures an effective one-dimensional “distance” between qubits A and B. Imagine the observer only measures two-qubit correlation functions that have a notion of spatial separation – for instance, they might look at correlators of the form , and we interpret the strength of correlation as an inverse distance.

One way to do this is to define a proxy for distance ℓ via the correlation between spins along a certain basis. Suppose our observer measures both z-z correlations and x-x correlations . Intuitively:

If both z-z and x-x correlations are high (close to +1 or –1), it suggests the qubits are “locked together’’ in all measured orientations – we interpret this as the qubits being effectively at zero separation (a single combined object).

If correlations are low or depend on orientation, the qubits behave more independently – we interpret this as some distance between them.

Let’s quantify an effective separation

ℓ such that

corresponds to maximal correlation in all bases, and larger

ℓ corresponds to weaker or basis-dependent correlations. A brief sketch of the exact push-forward measure is as follows. Define

and set

. Then

where

is the natural volume on

. We then adopt a Gaussian proxy

(see Eq.

4) for intuition.

For the separable state

: -

(since both spins are up in

z). - Since the product state factorizes, one has

as each qubit in

satisfies

. So in one basis the qubits appear perfectly correlated, and in another they are uncorrelated. The observer would conclude that

A and

B are not one single object – there is some “distance” between them that allows them to behave independently in at least one measurement basis.

for the separable state might be relatively broad, reflecting that the two qubits do not share a close locality in the emergent picture.

For the Bell state : - (since half the time both are up, half both are down). - as well (the Bell state is also an eigenstate of with eigenvalue +1). In fact, all corresponding two-qubit correlators in orthogonal bases are +1 for this Bell state. The observer sees A and B perfectly correlated in every way they check. The natural interpretation is that : the qubits are at the same “location’’ in the emergent space (or even considered a single entity). The correlation density would then be sharply peaked at .

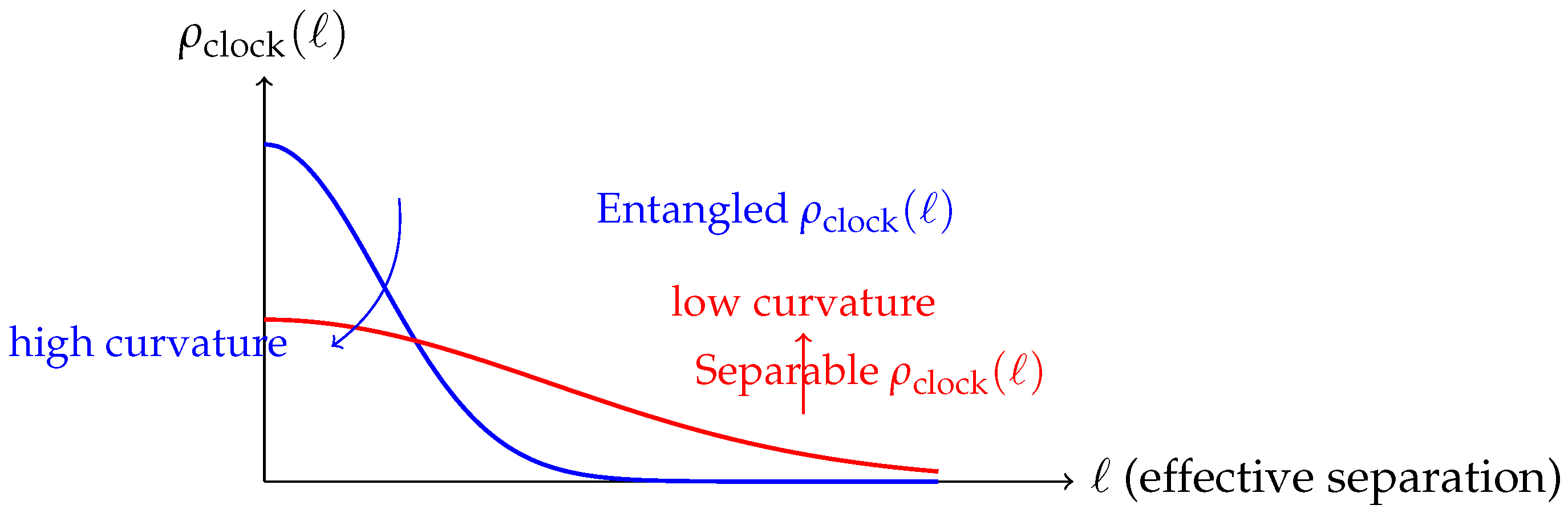

We can illustrate the effective correlation density for the two cases:

A simple ansatz for the correlation density

as a function of the effective separation

ℓ is

Here,

denotes the characteristic correlation length scale. Hence, from Eq. (

2), and using the Gaussian ansatz in Eq. (

4), the emergent metric component becomes

In summary, the two-qubit toy model shows that:

When two systems are entangled, an observer’s emergent space will tend to place them close together with a non-trivial geometry (possibly high curvature or even effectively identifying them as a single point for maximal entanglement).

When two systems are not entangled, it is possible for an observer to find a frame where they appear entirely uncorrelated (far apart, no direct influence), reinforcing the emergent locality.

This provides a concrete demonstration of both locality emergence and curvature-from-correlation using the simplest non-trivial quantum system.

3.3. Observer-Dependent Outlook

Finally, we emphasize the observer-dependent aspect using a slight variation of the two-qubit scenario. Imagine two observers looking at the same two- qubit entangled state , but choosing different measurement contexts:

Observer Alice measures correlations.

Observer Bob measures correlations (mixing bases between qubits).

Alice, as we saw, finds for the Bell state, and also (if she also measured x-x). So in Alice’s chosen basis set, A and B appear tightly bound with maximal correlation in both directions she checks.

Bob, however, measures A in z and B in x. For , what is ? One can compute this: for this state (because the Bell state is symmetric under simultaneous rotations, but if you measure different axes, correlations can cancel out). In fact, on A and on B anticommute on the state in a way that yields zero expectation. So Bob would observe no correlation in his chosen observable pair. To Bob, it might appear that the two qubits are not directly correlated (since whenever A is up or down, B is equally likely to be + or − in x). Thus, Bob’s emergent picture might place the qubits as more distant or even disconnected along the axis he’s examining.

This situation encapsulates the relativity of correlations: The “distance” or “connection” between two subsystems in the emergent space is not absolute, but depends on how the observer probes them. Alice’s projection yields a geometry where A and B are at zero separation (a single coupled system), whereas Bob’s projection —slicing differently—yields a geometry where A and B seem separated (at least in one direction of his space). Neither is wrong; they are simply different lower-dimensional views of the same . Of course, if an observer has access to all possible measurements (full tomography of the two-qubit state), they would reconstruct the full and recognize the state as entangled. But practical observers are limited, which is one reason different reference frames (or observers) can have different “slices” of reality.

To the extent that a shared consensus reality exists, it would emerge when observers compare notes and effectively combine their correlation data. But as long as they are looking at different cross-sections of , their personal geometries can differ — a nod to relational quantum mechanics interpretations where facts are observer-dependent.

From the two-qubit example and this observer-dependent twist, we see how the same quantum state can give rise to different emergent spacetimes for different observers. Entanglement (or the lack thereof) informs curvature, and the choice of measured observables informs the notion of distance and connection. This paves the way for exploring larger systems where these ideas might play out in more complex and rich ways, as we will discuss in the context of holography and other paradigms.

4. Connections to Existing Paradigms

4.1. Relation to AdS/CFT and Holography

One of the strongest pieces of evidence that spacetime geometry and quantum entanglement are closely related comes from the Anti-de Sitter/Conformal Field Theory (AdS/CFT) correspondence

4[

1]. In holographic duality, a

-dimensional gravitational spacetime in AdS is dual to a

d-dimensional quantum field theory on the boundary. Crucially, entanglement entropy in the boundary theory is connected to the area of extremal surfaces in the bulk spacetime via the Ryu–Takayanagi formula[

2]. In other words, entanglement (a quantum information quantity) directly gives rise to a geometric object (an area) in a higher dimension. This has led to slogans like “Entanglement builds geometry’’[

7].

Our correlationhedron framework is in harmony with these ideas. Here, the entire set of correlations

plays a role reminiscent of the AdS bulk, and an observer’s spacetime

is like a slice or patch of that bulk corresponding to a particular “code subspace’’ or perspective. A large entanglement between two parts of the boundary CFT (say two halves of the system) corresponds to those parts being connected in the bulk — potentially even by a wormhole if the entanglement is maximal (as conjectured in ER=EPR[

10,

11]). In our model, a maximally entangled pair of subsystems would appear as a single unified region in an observer’s

, analogous to how two black hole boundaries connected by a wormhole represent one geometry. Van Raamsdonk’s thought experiment[

7], where gradually reducing entanglement causes spacetime to “split’’ into two disconnected pieces, has a direct parallel: in the correlationhedron, if correlations between two sectors shrink, the projection for an observer can make those sectors drift apart in the emergent space (potentially becoming separate spacetimes if entanglement goes to zero).

Another point of contact is the idea of the

entanglement wedge in holography. The entanglement structure of a region of the CFT determines a certain bulk region (its entanglement wedge). In our terms, picking a particular observer (who might correspond to having access to only a region of the full system’s degrees of freedom) will project

onto a certain

that might correspond only to that wedge. While our framework is more general (not relying on a pre-existing spacetime, and not limited to conformal or highly symmetric states), it is encouraging that it reproduces the qualitative dependence of geometry on entanglement seen in AdS/CFT[

7,

10].

In summary, the correlationhedron approach can be seen as a generalization of holographic ideas beyond AdS backgrounds: any quantum state has a “bulk’’ of correlations, and any observer provides a “boundary’’ description (with one lower dimension) that experiences a geometry. When the state in question happens to be one like those in AdS/CFT (highly entangled, obeying area laws, etc.), should mirror the known bulk geometry. For more general states, defines a perhaps unusual geometry, but the mechanism — entanglement pattern dictating geometry — is analogous.

4.2. Tensor Networks and MERA

Tensor network states, especially MERA

5 and related holographic codes, provide explicit discrete models of emergent geometry from entanglement. A MERA tensor network for a 1D critical system, for example, has a structure that looks like a discrete hyperbolic (AdS) space; distances along the network correspond to length scales in the system, and entanglement between regions corresponds to connections through the network[

3].

Our framework is conceptually aligned: one could imagine constructing the correlationhedron for a state that is represented by a tensor network. Because tensor networks encode which parts of the system are entangled (connected by bonds) and how strongly, would be highly structured — likely consisting of clusters of correlation vectors reflecting the network connectivity. The observer’s projection could act like “looking down the network’’ from the top, seeing an effective geometry. In fact, if one takes the continuum limit of a MERA, one might get a continuous manifold akin to our . The emergent metric we defined via correlation density is analogous to how one might define a continuum metric from a discrete network (where areas with denser tensor connections correspond to more curvature or shorter distances).

An interesting aspect is that in tensor networks, geometry is approximate and state-dependent. Similarly, our emergent geometries depend on and . This means if the quantum state changes (even without dynamics, just considering a different state), the geometry can change — which is expected in a fixed network if you change the entanglement pattern (you might have to change the network or bond strengths). This underscores that spacetime here is not a fixed stage but a state-specific construct, which resonates with the idea of It from qubit and other paradigms where spacetime arises from quantum degrees of freedom.

One can also consider more complex networks like random tensor networks or Quantum Error Correcting Codes (QECC) that have holographic properties. The correlationhedron of such states might naturally be very symmetric and convex, potentially easier to analyze. It would be fascinating to identify the correlationhedron with known polytopes or geometries for solvable cases (for example, the correlationhedron for a stabilizer code state might have facets corresponding to the stabilizer constraints, etc.). This could provide a new geometric understanding of holographic codes, where the code’s properties (like quantum error correction threshold) relate to the shape of .

In short, tensor networks provide concrete examples where entanglement structure → geometry mapping is realized, and our framework aims to provide a more general, analytical handle on that idea via the continuous geometry of . The correlationhedron approach shares the goal of MERA and related work: to make emergent space tangible and computable from entanglement data.

4.3. Relational and Quantum Reference Frame Theories

The notion that different observers may have different “slices’’ of reality has analogues in relational quantum mechanics and quantum reference frame transformations. In Carlo Rovelli’s relational quantum mechanics[

4], the state of a system is always defined relative to another system (observer) and there is no global, observer-independent state of affairs. Likewise, here

is essentially the state of spacetime as seen by observer

. If one changes the observer (perhaps by entangling the original observer with a new system or by switching perspective to another subsystem considered as the reference), one effectively applies a transformation to

.

Recent work on quantum reference frames suggests that one can transform the description of physical situations from one frame to another via certain symmetries (often entangling the original frame with the system) — a procedure that can mix what one observer calls space and another calls time[

25]. This is evocative of Axiom A6: entanglement and time can swap roles depending on the frame. In a sense, switching reference frames in those formulations is akin to choosing a different way to project the underlying invariant quantum state’s correlations into “personal’’ space and time of the new frame.

Additionally, approaches like the Page-Wootters mechanism (which we cited in A6) and the idea of “evolving constants of motion’’ relate to the concept of an emergent time from correlations. In Page-Wootters, a static global state yields a perception of evolution to an internal observer who correlates with a clock. This is exactly an example of how one observer’s (that isolates the clock correlations) yields a time dimension, whereas another slice might not separate time at all.

Our framework can thus be seen as a concrete implementation of a relational idea: there is one quantum reality (the universal wavefunction’s correlation structure), and each observer “cuts’’ it into their space and time. The hope is that by formalizing , we could connect with these relational ideas mathematically and perhaps define how to transform between and (observers’ frames) by an operation on . While we have not delved into the transformation rules between different observers’ projections, the existence of as a containing structure hints at a possibility: a change of observer corresponds to some symmetry or linear transformation on the correlation vector space, which in turn induces a map between the emergent manifolds (could this be akin to a Lorentz transform or a diffeomorphism in the emergent setting? This remains to be fleshed out).

4.4. Experimental Outlook

A fundamental question is whether these ideas of emergent spacetime from quantum correlations can be tested or at least evidenced in laboratory systems. While directly “seeing’’ spacetime emerge is daunting, there are several potential experimental signatures:

Entanglement-Dependent Geometry in Simulators: Quantum simulators (arrays of qubits, cold atoms in optical lattices, etc.) allow preparation of states with tunable entanglement patterns. For example, one can create a family of states ranging from product states to highly entangled states (like cluster states or GHZ states). If our framework is correct, certain geometric properties derived from correlation functions should change in predictable ways. One could attempt to measure an “emergent distance’’ between parts of the simulator by seeing how correlation strength decays with some notion of separation. For instance, in a 1D chain, a highly entangled state (e.g. critical ground state) should have shorter effective distances (or more curved correlation space) between distant sites than a gapped product-like state. Practically, one could measure multi-point correlation functions or mutual information between segments as a function of system parameters. A signature of emergent geometry might be that these data can be fitted to a smooth metric space model for the entangled state but not for a less entangled one.

Curvature from Entanglement Distribution: Engineering states with varying degrees of entanglement and observing how an information-theoretic notion of curvature changes. For example, define an operational proxy for curvature: take three subsystems and measure correlation-based distances . If correlations embed into a geometric plane, distances will satisfy triangle inequalities etc., but if there’s curvature, one might detect a discrepancy (similar to how in general relativity one could detect curvature via geodesic deviation). By creating states where subsystem B is entangled differently with A and C, one might see an emergent triangle inequality violation that indicates curvature. This is speculative, but one could imagine plotting an “entanglement triangle’’ and measuring angles via correlations.

Tomography of the Correlationhedron: With small systems (few qubits), full state tomography is possible. One could reconstruct the full set of correlation vectors for a given state. While exponentially hard in general, for say 3 or 4 qubits this is doable. Then one can analyze the geometry of : for example, find if it indeed forms a convex polytope in certain coordinates. One could attempt to directly apply the emergent metric formula. Although with so few qubits, speaking of “smooth geometry’’ is a stretch, one might discretely see that a maximally entangled 4-qubit state (like a 4-qubit GHZ or cluster) has a that is more “curved’’ (maybe more tetrahedron- like) than a product state whose might be more hyper-rectangular in shape.

Quantum Gravity Analogues: There are proposals to test if gravity itself might arise from quantum entanglement by observing entanglement- induced forces between masses. For instance, if two micro-mass particles become entangled through gravitational interaction (as in proposed experiments by Bose

et al. [

26] and Marletto–Vedral[

27]), it would indicate that gravity (spacetime geometry) can transmit quantum information. In our context, observing gravitationally mediated entanglement would support the idea that spacetime geometry (the gravitational field) is fundamentally linked to quantum correlations. While these experiments are extremely challenging, a positive result would strongly bolster frameworks like ours where geometry is not fundamental but emergent from quantum phenomena. In essence, it would show that when we “entangle” spacetime (via masses that cause curvature), it responds quantum mechanically, aligning with the notion that spacetime is made of the same stuff as quantum correlations.

Tests of Entanglement–Time Duality: One could test the interchangeability of entanglement and time in a quantum clock setup. Prepare an entangled state between a clock qubit and a system qubit (à la Page-Wootters). Verify that the system’s dynamics (from the clock’s perspective) slow down or speed up as the entanglement between clock and system is varied. This would be like showing experimentally that what looks like a faster flow of time can be achieved by reducing entanglement and vice versa. Some recent experiments with entangled clocks and systems (or using an ancilla as a reference) could be interpreted in this light.

In practice, demonstrating an “emergent geometry’’ is subtle—it’s not as direct as photographing spacetime. But even observing patterns consistent with these ideas (for example, mutual information patterns that match what you’d expect if the system’s states were laid out on a curved space) would be intriguing. If a quantum simulator can realize states that correspond to, say, a 2D curved space, one might measure correlation functions that match those of a quantum field on a curved space, which would be evidence that the entanglement structure is geometric.

Overall, while direct experimental confirmation of spacetime emergence is far on the horizon, incremental evidence can be gathered by studying highly entangled quantum systems in the lab and checking for consistency with geometric descriptions. The rapid progress in quantum simulation and quantum information experiments makes us optimistic that at least some aspects of this correspondence can be tested in controlled systems in the future.

While experimental validation remains challenging, the framework presented here opens several promising theoretical avenues for further development.

4.5. Future Directions

Several key developments remain:

Observer transformations: Construct explicit maps between different observer manifolds , and recover standard relativistic transformations in regimes where classical spacetime emerges. This could further clarify the relational nature of geometry and lead to a generalized notion of observer-dependent diffeomorphisms.

Lorentzian signature and causality:Section 2.5 outlines how a Lorentzian signature can emerge by partitioning correlation density into temporal and spatial components. Future work will explore concrete models of such projections, and how causal relations between events may arise from correlation patterns in

and be preserved across observers.

Emergent dynamics and metric flow:Section 2.7 introduces how time-evolving quantum states

induce trajectories on the emergent manifold, leading to a time-dependent geometry via

. A key direction for future research is to formulate dynamical laws linking these metric flows to underlying unitary evolution—potentially yielding analogues of Einstein’s equations from quantum-informational principles.

Emergent field equations: derive how Einstein-like field equations might emerge from the correlation structure. One approach would be to identify how correlation density gradients relate to energy-momentum distributions, potentially yielding equations of the form:

where

would be an effective energy-momentum tensor derived from correlation dynamics. The precise form of

remains to be derived, and its structure may depend on the nature of the observer slicing, time-dependence of the state, and additional assumptions. This would complete the analogy with general relativity, showing how correlation patterns not only determine geometry but also govern its evolution according to physical principles.

We view this paper as establishing the conceptual groundwork upon which these questions can be systematically addressed in subsequent investigations.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

We have presented a framework in which spacetime is an emergent construct, arising from the rich structure of quantum correlations in a global wavefunction. By introducing the correlationhedron and a set of axioms, we showed how classical concepts — locality, dimensionality, curvature, and even the flow of time — can be interpreted as approximate, observer-dependent properties of an underlying quantum-correlation geometry.

In this revised formulation, we have clarified how the correlationhedron is defined as a convex set of correlation vectors obeying quantum constraints (Axiom A1 and A2), and how an observer’s choice (reference frame or measurement context) picks out a slice

that functions as that observer’s spacetime (A3). We expanded on how locality emerges from clustering of correlations (A4) with concrete examples, and on the intriguing duality between entanglement and time (A6) that suggests observers may trade one for the other in their description of reality. A quantitative toy example with two qubits illustrated how an entangled state yields a strongly curved emergent metric, whereas a separable state yields a flat one, capturing the idea that entanglement creates the “close-knit” fabric of spacetime. We also included schematic figures to visualize these concepts: the shape of

together with the action of observer projections (

Figure 1), and the relationship between entanglement distribution and induced curvature (

Figure 2) .

The connections drawn to AdS/CFT, tensor networks, and relational quantum theories situate this work in a broader context. Notably, the common theme is that information constructs reality: whether it be the entanglement entropy dictating minimal surfaces in AdS[

2], tensor network entanglement patterns encoding a holographic metric[

3], or the relational viewpoint that state is observer-dependent[

4], all resonate with the idea that spacetime might be an effective description arising from deeper quantum structure[

11]. Our framework contributes to this discourse by providing a set of principles and a scaffold to potentially unify these ideas and apply them to arbitrary quantum states (not just highly symmetric ones).

However, many open questions and limitations remain. Most significantly, this framework in its current form is largely

kinematic. We have not derived the dynamical laws of emergent spacetime — there is no equivalent yet of Einstein’s equations or a mechanism for how

back-reacts on

when

changes. In a fully realized theory, we would want to see how unitary evolution of the quantum state (or changes in entanglement due to, say, subsystem interactions) translates to dynamics in

(perhaps emergent gravitational or cosmological behavior). Addressing this will likely require additional axioms or input, possibly relating changes in

to energy- momentum constraints. For now, we can only speculate on the qualitative form of such emergent dynamics. If

evolves in time (due to unitary dynamics or interactions), then

itself deforms in correlation space, and consequently an observer’s

and metric

on

will change with time. Intuitively, increasing entanglement in certain degrees of freedom should concentrate

in the corresponding region of

, deepening the curvature there (akin to how added mass-energy curves spacetime in general relativity), whereas a significant loss of entanglement would flatten out those regions or even cause the emergent spacetime to split into disjoint parts (consistent with the idea that extreme disentanglement can disconnect space[

7]). One could envision an equation governing

in terms of

or other state parameters—analogous in spirit to Einstein’s field equations, but emerging from quantum dynamics rather than imposed as fundamental. While these ideas are admittedly speculative, they provide a glimpse of how a dynamical theory might be incorporated into our correlation-centric framework.

Another limitation is the issue of

causality. If each observer has their own emergent time ordering (A6) from their slice of correlations, how do we ensure that different observers’ causal structures are compatible or agree where they overlap? We have an implicit assumption that when observers share information, there is a consistent translation between their spacetimes. This touches on the quantum reference frame transformations discussed in

Section 4.3. A future extension of this work should formalize how to move between

and

— in the best case, recovering something analogous to Lorentz transformations or general coordinate transformations between emergent spacetimes. Until then, the framework has an observer-relativity that, while conceptually aligned with relational quantum mechanics, needs a dictionary to compare with our usual notion of a single objective spacetime that all observers inhabit.

The

topology of emergent space is another subtle point (addressed briefly in Appendix A.3): depending on how

is sliced,

could have exotic topology (even discontinuous or fragmented). Not all such topologies may make physical sense. We might need additional constraints to exclude unphysical emergent worlds or to explain why we experience a connected, smooth 3+1 dimensional world and not, say, two disconnected 2+1 worlds. It is tantalizing to think that quantum constraints (like monogamy of entanglement or constraints from quantum error correction) might naturally enforce a reasonable topology for

in realistic scenarios[

23][

3], but this remains speculative.

Despite these challenges, the possible payoffs are high. If successful, this line of research could provide a new lens on the quantum gravity problem: rather than quantizing geometry, it “geometrizes” quantum mechanics. It suggests that the mysteries of gravity and spacetime might be resolved not by tweaking general relativity or quantum field theory in isolation, but by understanding the information-theoretic substrate that underlies both. This framework is still in a preliminary form, but it aligns with a number of emerging threads in theoretical physics that hint we are on the right track – that spacetime and gravity are emergent from the quantum world’s fabric of correlations[

14].

An intriguing implication of this framework is that gravitational effects typically attributed to dark matter could, in part, arise from the geometric imprint of entanglement. When two systems are strongly entangled, the induced correlation density — and thus the emergent curvature — is not necessarily localized on the systems themselves, but can be distributed across the region connecting them. If both entangled partners lie within the observer’s projection, this curvature appears as a spatial bridge or concentration between them, contributing normally to the perceived mass distribution. However, if one partner lies outside the observer’s accessible sector of , the associated curvature becomes delocalized: the observable system appears to curve space more weakly than expected, with the “missing” curvature effectively distributed into inaccessible regions. From the observer’s perspective, this manifests as a gravitational anomaly — curvature without corresponding visible matter — mimicking the presence of dark matter. In this view, then, certain dark matter effects might be reinterpreted as geometric artifacts of entanglement with degrees of freedom that are hidden, decohered, or beyond observational reach.

In closing, we reiterate the essential vision: spacetime is not fundamental, but an evolving mosaic pieced together by observers from the correlations within an all-encompassing quantum state.

This paper establishes the conceptual and mathematical foundations for this perspective, deliberately focusing on the static, structural aspects of the framework. The development of dynamics, explicit calculation methods for realistic systems, and refined connections to existing quantum gravity approaches represent natural extensions that we intend to address in forthcoming work. The correlationhedron framework introduced here should be viewed as a starting point for a broader research program rather than a fully realized theory.

What appears continuous and geometric is, at its core, an abstraction of quantum information links. By studying those links directly (the correlationhedron ) and understanding how different perspectives give rise to different slices of reality, we take steps toward a theory that does not just unify physics at a formal level, but conceptually explains why the world has the appearance it does to us, and how that appearance might change under extreme quantum conditions. Future work will aim to further develop the mathematical apparatus (e.g. to handle dynamical evolution and multiple observers rigorously) and to explore toy models (like quantum simulators or tabletop experiments) that could provide hints of these correlation-built spacetimes in action.