Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

19 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Ubiquity of Ter Genes in Genome Annotations

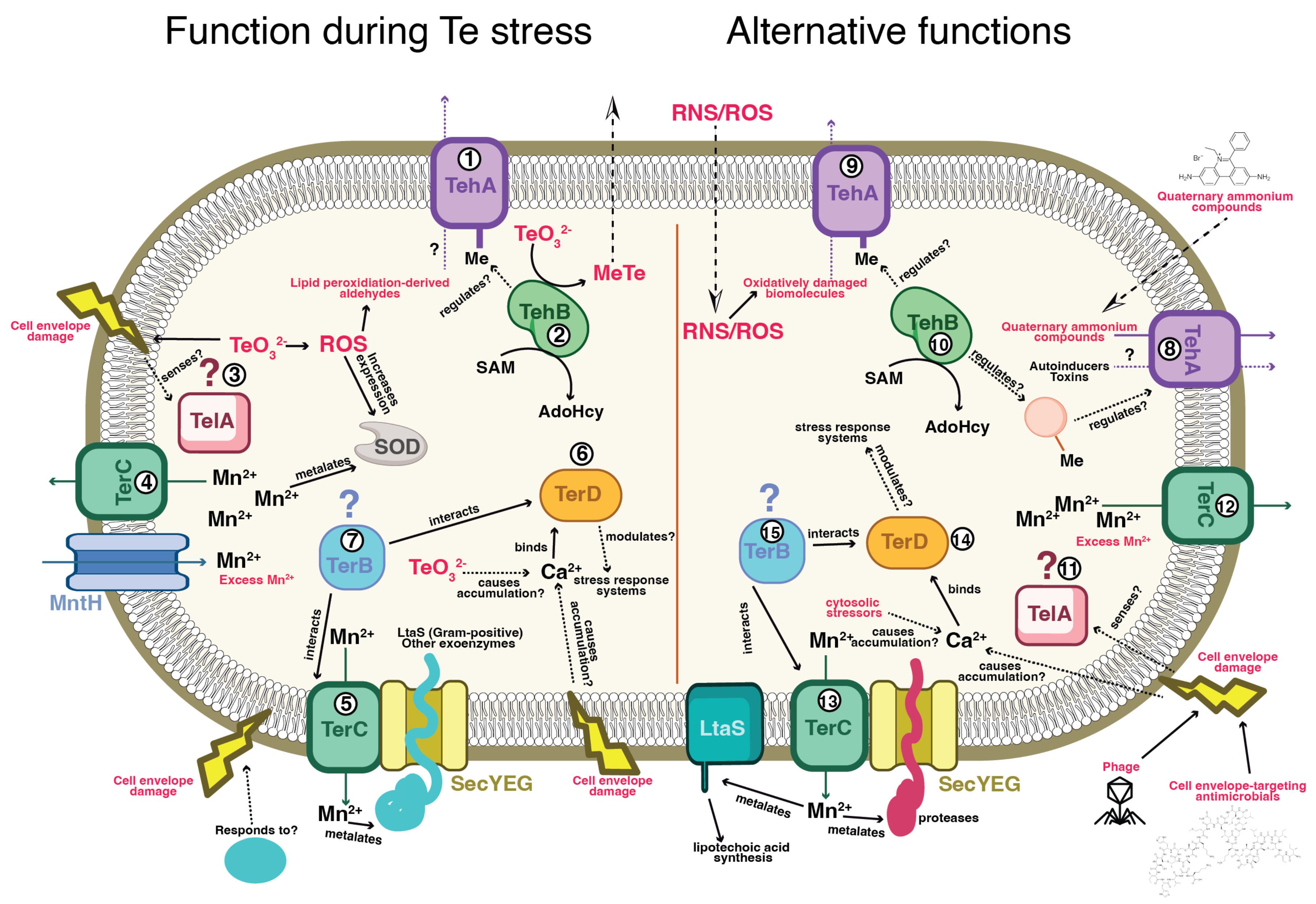

3. Primary Functions of the TER Genes

4. Future Directions

- (i)

- Confirming if TehA has a function in tellurium resistance.

- (ii)

- Determining if and how TehB directly or indirectly regulates the activity of TehA.

- (iii)

- Determining the physiological substrate of TehA. Is it antimicrobial compounds? Or does it export oxidatively damaged biomolecules?

- (iv)

- A mechanism by which TelA confers resistance to membrane-targeting antimicrobials.

- (v)

- Describing the mechanism(s) by which TerD domains participate in calcium signaling. How do cells use calcium as a signal of extracellular stress and how do TerD domains integrate these signals?

- (vi)

- Confirming if the function of TerC in exoenzyme metalation is universal. While this function is conserved between B. subtilis, L. monocytogenes, and B. anthracis, does this hold true beyond the Firmicutes phylum?

- (vii)

- Identifying additional metalloenzyme targets of TerC in B. subtilis and other bacteria.

Funding

References

- Missen, O. P.; Ram, R.; Mills, S. J.; Etschmann, B.; Reith, F.; Shuster, J.; Smith, D. J.; Brugger, J. Love Is in the Earth: A Review of Tellurium (Bio)Geochemistry in Surface Environments. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 204, 103150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradi, H.; Troch, P. Ein Verfahren Zum Nachweis Der Diphtheriebazillen. Muench Med Wochenschr 1912, 59, 1652–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, V. The Isolation and Typing of C. Diphtheriæ on Tellurite Blood Agar. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1937, 44, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadik, P. M.; Chapman, P. A.; Siddons, C. A. Use of Tellurite for the Selection of Verocytotoxigenic Escherichia Coli O157. J. Med. Microbiol. 1993, 39, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presentato, A.; Turner, R. J.; Vasquez, C. C.; Yurkov, V.; Zannoni, D. Tellurite-Dependent Blackening of Bacteria Emerges from the Dark Ages. Environ. Chem. 2019, 16, 266–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, A.; Jacoby, G. Plasmid-Determined Resistance to Tellurium Compounds. J. Bacteriol. 1977, 129, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Taylor, D. E. Incidence of Tellurite Resistance Determinants among Plasmids of Different Incompatibility Groups. Plasmid 1994, 32, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D. E. Detection of Tellurite-Resistance Determinants in IncP Plasmids. Microbiology 1985, 131, 3135–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. E.; Summers, A. O. Association of Tellurium Resistance and Bacteriophage Inhibition Conferred by R Plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 1979, 137, 1430–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobling, M. G.; Ritchie, D. A. The Nucleotide Sequence of a Plasmid Determinant for Resistance to Tellurium Anions. Gene 1988, 66, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobling, M. G.; Ritchie, D. A. Genetic and Physical Analysis of Plasmid Genes Expressing Inducible Resistance of Tellurite in Escherichia Coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG 1987, 208, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, K. F.; Colleran, E.; Taylor, D. E. Phage Inhibition, Colicin Resistance, and Tellurite Resistance Are Encoded by a Single Cluster of Genes on the IncHI2 Plasmid R478. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 5016–5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, E. G.; Taylor, D. E. Plasmid-Mediated Resistance to Tellurite: Expressed and Cryptic. Plasmid 1992, 27, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, E. G.; Thomas, C. M.; Ibbotson, J. P.; Taylor, D. E. Transcriptional Analysis, Translational Analysis, and Sequence of the kilA-Tellurite Resistance Region of Plasmid RK2Ter. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. E. Bacterial Tellurite Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 1999, 7, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gara, J. P.; Gomelsky, M.; Kaplan, S. Identification and Molecular Genetic Analysis of Multiple Loci Contributing to High-Level Tellurite Resistance in Rhodobacter Sphaeroides 2.4.1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 4713–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasteen, T. G.; Fuentes, D. E.; Tantaleán, J. C.; Vásquez, C. C. Tellurite: History, Oxidative Stress, and Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, C.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Rensing, C.; Kristiansson, E.; Larsson, D. G. BacMet: Antibacterial Biocide and Metal Resistance Genes Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D737–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, M. Y.; Wolf, Y. I.; Makarova, K. S.; Vera Alvarez, R.; Landsman, D.; Koonin, E. V. COG Database Update: Focus on Microbial Diversity, Model Organisms, and Widespread Pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D274–D281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. E.; Hou, Y.; Turner, R. J.; Weiner, J. H. Location of a Potassium Tellurite Resistance Operon (tehA tehB) within the Terminus of Escherichia Coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 2740–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R. J.; Taylor, D. E.; Weiner, J. H. Expression of Escherichia Coli TehA Gives Resistance to Antiseptics and Disinfectants Similar to That Conferred by Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pumps. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Mingfu; Turner Raymond J. ; Winstone Tara L.; Saetre Andrea; Dyllick-Brenzinger Melanie; Jickling Glen; Tari Leslie W.; Weiner Joel H.; Taylor Diane E. Escherichia Coli TehB RequiresS-Adenosylmethionine as a Cofactor To Mediate Tellurite Resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 6509–6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R. J.; Weiner, J. H.; Taylor, D. E. Neither Reduced Uptake nor Increased Efflux Is Encoded by Tellurite Resistance Determinants Expressed in Escherichia Coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 1995, 41, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitby, P. W.; Seale, T. W.; Morton, D. J.; VanWagoner, T. M.; Stull, T. L. Characterization of the Haemophilus Influenzae tehB Gene and Its Role in Virulence. Microbiology 2010, 156, 1188–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, H. G.; Cameron, A. D.; Iwata, S.; Beis, K. Structure and Mechanism of the Chalcogen-Detoxifying Protein TehB from Escherichia Coli. Biochem. J. 2011, 435, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Hu, L.; Punta, M.; Bruni, R.; Hillerich, B.; Kloss, B.; Rost, B.; Love, J.; Siegelbaum, S. A.; Hendrickson, W. A. Homologue Structure of the SLAC1 Anion Channel for Closing Stomata in Leaves. Nature 2010, 467, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. E.; Walter, E. G.; Sherburne, R.; Bazett-Jones, D. P. Structure and Location of Tellurium Deposited in Escherichia Coli Cells Harbouring Tellurite Resistance Plasmids. J. Ultrastruct. Mol. Struct. Res. 1988, 99, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, J. M.; Kay, W. W. Tellurite Susceptibility and Non-Plasmid-Mediated Resistance in Escherichia Coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1986, 30, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick-Brenzinger, M.; Liu, M.; Winstone, T. L.; Taylor, D. E.; Turner, R. J. The Role of Cysteine Residues in Tellurite Resistance Mediated by the TehAB Determinant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 277, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, L.; Gracheck, S. J.; Miller, P. F. Overexpression of the MarA Positive Regulator Is Sufficient to Confer Multiple Antibiotic Resistance in Escherichia Coli. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 2888–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, A. S.; Levy, S. B. Identification of New Genes Regulated by the marRAB Operon in Escherichia Coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, I. T.; Skurray, R. A.; Tam, R.; Saier Jr, M. H.; Turner, R. J.; Weiner, J. H.; Goldberg, E. B.; Grinius, L. L. The SMR Family: A Novel Family of Multidrug Efflux Proteins Involved with the Efflux of Lipophilic Drugs. Mol. Microbiol. 1996, 19, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Huang, M.; Wei, Y. Diversity of the Reaction Mechanisms of SAM-Dependent Enzymes. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, K. Bacterial Multidrug Efflux Pumps Serve Other Functions. Microbe-Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2008, 3, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piddock, L. J. V. Multidrug-Resistance Efflux Pumps ? Not Just for Resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, D. M.; Kumar, A. Resistance-Nodulation-Division Multidrug Efflux Pumps in Gram-Negative Bacteria: Role in Virulence. Antibiotics 2013, 2, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenmiller, D. M.; Spiro, S. The yjeB (nsrR) Gene of Escherichia Coli Encodes a Nitric Oxide-Sensitive Transcriptional Regulator. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justino, M. C.; Vicente, J. B.; Teixeira, M.; Saraiva, L. M. New Genes Implicated in the Protection of Anaerobically Grown Escherichia Coli against Nitric Oxide*. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 2636–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetar, H.; Gilmour, C.; Klinoski, R.; Daigle, D. M.; Dean, C. R.; Poole, K. mexEF-oprN Multidrug Efflux Operon of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Regulation by the MexT Activator in Response to Nitrosative Stress and Chloramphenicol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Cook, D. N.; Alberti, M.; Pon, N. G.; Nikaido, H.; Hearst, J. E. Genes acrA and acrB Encode a Stress-induced Efflux System of Escherichia Coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 16, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraud, S.; Poole, K. Oxidative Stress Induction of the MexXY Multidrug Efflux Genes and Promotion of Aminoglycoside Resistance Development in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ryu, S.; Jeon, B. Transcriptional Regulation of the CmeABC Multidrug Efflux Pump and the KatA Catalase by CosR in Campylobacter Jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6883–6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, Y.; Sobel, M. L.; Poole, K. Antibiotic Inducibility of the MexXY Multidrug Efflux System of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Involvement of the Antibiotic-Inducible PA5471 Gene Product. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, B.; Wang, Y.; Katzianer, D.; Wang, H.; Wu, H.; Zhong, Z.; Zhu, J. Role of a TehA Homolog in Vibrio Cholerae C6706 Antibiotic Resistance and Intestinal Colonization. Can. J. Microbiol. 2013, 59, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.; Passador, L.; Srikumar, R.; Tsang, E.; Nezezon, J.; Poole, K. Influence of the MexAB-OprM Multidrug Efflux System on Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 5443–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y. Y.; Chua, K. L. The Burkholderia Pseudomallei BpeAB-OprB Efflux Pump: Expression and Impact on Quorum Sensing and Virulence. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 4707–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.-G.; Kang, Y.; Jang, J. Y.; Jog, G. J.; Lim, J. Y.; Kim, S.; Suga, H.; Nagamatsu, T.; Hwang, I. Quorum Sensing and the LysR-Type Transcriptional Activator ToxR Regulate Toxoflavin Biosynthesis and Transport in Burkholderia Glumae. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Gross, D. C. Characterization of a Resistance-Nodulation-Cell Division Transporter System Associated with the Syr-Syp Genomic Island of Pseudomonas Syringae Pv. Syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5056–5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J. M.; Arenas, F. A.; Pradenas, G. A.; Sandoval, J. M.; Vásquez, C. C. Escherichia Coli YqhD Exhibits Aldehyde Reductase Activity and Protects from the Harmful Effect of Lipid Peroxidation-Derived Aldehydes. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 7346–7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradenas, G. A.; Díaz-Vásquez, W. A.; Pérez-Donoso, J. M.; Vásquez, C. C. Monounsaturated Fatty Acids Are Substrates for Aldehyde Generation in Tellurite-Exposed Escherichia Coli. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 563756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refsgaard, H. H. F.; Tsai, L.; Stadtman, E. R. Modifications of Proteins by Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Peroxidation Products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R. J.; Weiner, J. H.; Taylor, D. E. The Tellurite-Resistance Determinants tehAtehB and klaAklaBtelB Have Different Biochemical Requirements. Microbiology 1995, 141, 3133–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D. E. Bacterial Tellurite Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 1999, 7, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R. J.; Weiner, J. H.; Taylor, D. E. In Vivo Complementation and Site-Specific Mutagenesis of the Tellurite Resistance Determinant kilAtelAB from IncP Alpha Plasmid RK2Ter. Microbiol. Read. Engl. 1994, 140 ( Pt 6) Pt 6, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharoff, P.; Saadi, S.; Chang, C. H.; Saltman, L. H.; Figurski, D. H. Structural, Molecular, and Genetic Analysis of the kilA Operon of Broad-Host-Range Plasmid RK2. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 3463–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holčík, M.; Iyer, V. M. Conditionally Lethal Genes Associated with Bacterial Plasmids. Microbiology 1997, 143, 3403–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansegrau, W.; Lanka, E.; Barth, P. T.; Figurski, D. H.; Guiney, D. G.; Haas, D.; Helinski, D. R.; Schwab, H.; Stanisich, V. A.; Thomas, C. M. Complete Nucleotide Sequence of Birmingham IncPα Plasmids: Compilation and Comparative Analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 239, 623–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulein, R.; Dehio, C. The VirB/VirD4 Type IV Secretion System of Bartonella Is Essential for Establishing Intraerythrocytic Infection. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 46, 1053–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, K.; Li, Y. G.; Ogawa-Kishida, N.; Khara, P.; Mamun, A. A. M. A.; Bosserman, R. E.; Christie, P. J. Chimeric Systems Composed of Swapped Tra Subunits between Distantly-Related F Plasmids Reveal Striking Plasticity among Type IV Secretion Machines. PLOS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, S. E.; Ebrahimi, C.; Hollands, A.; Okumura, C. Y.; Aroian, R. V.; Nizet, V.; McGillivray, S. M. Novel Role for the yceGH Tellurite Resistance Genes in the Pathogenesis of Bacillus Anthracis. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, A. W.; Liao, X.; Helmann, J. D. Contributions of the σ, σ and σ Regulons to the Lantibiotic Resistome of Acillus Subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 90, 502–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, E. G.; Thomas, C. M.; Ibbotson, J. P.; Taylor, D. E. Transcriptional Analysis, Translational Analysis, and Sequence of the kilA-Tellurite Resistance Region of Plasmid RK2Ter. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anantharaman, V.; M. Iyer, L.; Aravind, L. Ter-Dependent Stress Response Systems: Novel Pathways Related to Metal Sensing, Production of a Nucleoside-like Metabolite, and DNA-Processing. Mol. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 3142–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T. T.; Panesso, D.; Diaz, L.; Rios, R.; Arias, C. A. 601. TelA and XpaC Are Novel Mediators of Daptomycin Resistance in Enterococcus Faecium. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6 (Supplement_2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkovicova, L.; Smidak, R.; Jung, G.; Turna, J.; Lubec, G.; Aradska, J. Proteomic Analysis of the TerC Interactome: Novel Links to Tellurite Resistance and Pathogenicity. J. Proteomics 2016, 136, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.; Joyce, S.; Hill, C.; Cotter, P. D.; Ross, R. P. TelA Contributes to the Innate Resistance of Listeria Monocytogenes to Nisin and Other Cell Wall-Acting Antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 4658–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.; Joyce, S.; Hill, C.; Cotter, P. D.; Ross, R. P. TelA Contributes to the Innate Resistance of Listeria Monocytogenes to Nisin and Other Cell Wall-Acting Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 4658–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersohn, A.; Brigulla, M.; Haas, S.; Hoheisel, J. D.; Völker, U.; Hecker, M. Global Analysis of the General Stress Response ofBacillus Subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5617–5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Ayala, F.; Bartolini, M.; Grau, R. The Stress-Responsive Alternative Sigma Factor SigB of Bacillus Subtilis and Its Relatives: An Old Friend With New Functions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, R. W.; Rodriguez-Lemoine, V.; Datta, N. R Factors from Serratia Marcescens. Microbiology 1975, 86, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.-R.; Lou, Y.-C.; Seven, A. B.; Rizo, J.; Chen, C. NMR Structure and Calcium-Binding Properties of the Tellurite Resistance Protein TerD from Klebsiella Pneumoniae. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 405, 1188–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Zaretskaya, I.; Raytselis, Y.; Merezhuk, Y.; McGinnis, S.; Madden, T. L. NCBI BLAST: A Better Web Interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36 (suppl_2), W5–W9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdobnov, E. M.; Apweiler, R. InterProScan – an Integration Platform for the Signature-Recognition Methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 847–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, C. A.; Hynes, R. O. Distribution and Evolution of von Willebrand/Integrin A Domains: Widely Dispersed Domains with Roles in Cell Adhesion and Elsewhere. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 3369–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaman, V.; Iyer, L. M.; Aravind, L. Ter-Dependent Stress Response Systems: Novel Pathways Related to Metal Sensing, Production of a Nucleoside-like Metabolite, and DNA-Processing. Mol. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 3142–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K. S.; Wolf, Y. I.; Koonin, E. V. Towards Functional Characterization of Archaeal Genomic Dark Matter. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D. C.; Myers, C. L.; Huttenhower, C.; Hibbs, M. A.; Hayes, A. P.; Paw, J.; Clore, J. J.; Mendoza, R. M.; Luis, B. S.; Nislow, C.; Giaever, G.; Costanzo, M.; Troyanskaya, O. G.; Caudy, A. A. Computationally Driven, Quantitative Experiments Discover Genes Required for Mitochondrial Biogenesis. PLOS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckers, M.; Balleininger, M.; Vukotic, M.; Römpler, K.; Bareth, B.; Juris, L.; Dudek, J. Aim24 Stabilizes Respiratory Chain Supercomplexes and Is Required for Efficient Respiration. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 2985–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T. T.; Panesso, D.; Gao, H.; Roh, J. H.; Munita, J. M.; Reyes, J.; Diaz, L.; Lobos, E. A.; Shamoo, Y.; Mishra, N. N.; Bayer, A. S.; Murray, B. E.; Weinstock, G. M.; Arias, C. A. Whole-Genome Analysis of a Daptomycin-Susceptible Enterococcus Faecium Strain and Its Daptomycin-Resistant Variant Arising during Therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumby, P.; Smith, M. C. M. Genetics of the Phage Growth Limitation (Pgl) System of Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 44, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkovicova, L.; Vavrova, S. M.; Mravec, J.; Grones, J.; Turna, J. Protein–Protein Association and Cellular Localization of Four Essential Gene Products Encoded by Tellurite Resistance-Conferring Cluster “Ter” from Pathogenic Escherichia Coli. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 104, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCorquodale, D. J.; Warner, H. R. Bacteriophage T5 and Related Phages. In The Bacteriophages; Calendar, R., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillor, O.; Kirkup, B. C.; Riley, M. A. Colicins and Microcins: The next Generation Antimicrobials. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hilsenbeck, J. L.; Park, H.; Chen, G.; Youn, B.; Postle, K.; Kang, C. Crystal Structure of the Cytotoxic Bacterial Protein Colicin B at 2.5 Å Resolution. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilsl, H.; Braun, V. Strong Function-Related Homology between the Pore-Forming Colicins K and 5. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 6973–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanssouci, É.; Lerat, S.; Grondin, G.; Shareck, F.; Beaulieu, C. Tdd8: A TerD Domain-Encoding Gene Involved in Streptomyces Coelicolor Differentiation. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2011, 100, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigle, F.; Lerat, S.; Bucca, G.; Sanssouci, É.; Smith, C. P.; Malouin, F.; Beaulieu, C. A terD Domain-Encoding Gene (SCO2368) Is Involved in Calcium Homeostasis and Participates in Calcium Regulation of a DosR-Like Regulon in Streptomyces Coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Hodgson, D. A.; Wentzel, A.; Nieselt, K.; Ellingsen, T. E.; Moore, J.; Morrissey, E. R.; Legaie, R.; Consortium, T. S.; Wohlleben, W.; Rodríguez-García, A.; Martín, J. F.; Burroughs, N. J.; Wellington, E. M. H.; Smith, M. C. M. Metabolic Switches and Adaptations Deduced from the Proteomes of Streptomyces Coelicolor Wild Type and phoP Mutant Grown in Batch Culture *. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, P.; Bourassa, S.; Poirier, G. G.; Beaulieu, C. Identification of Streptomyces Coelicolor Proteins That Are Differentially Expressed in the Presence of Plant Material. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1884–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotna, J.; Vohradsky, J.; Berndt, P.; Gramajo, H.; Langen, H.; Li, X.-M.; Minas, W.; Orsaria, L.; Roeder, D.; Thompson, C. J. Proteomic Studies of Diauxic Lag in the Differentiating Prokaryote Streptomyces Coelicolor Reveal a Regulatory Network of Stress-Induced Proteins and Central Metabolic Enzymes. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffert, Y.; Franz-Wachtel, M.; Fladerer, C.; Nordheim, A.; Reuther, J.; Wohlleben, W.; Mast, Y. Proteomic Analysis of the GlnR-Mediated Response to Nitrogen Limitation in Streptomyces Coelicolor M145. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotna, J.; Vohradsky, J.; Berndt, P.; Gramajo, H.; Langen, H.; Li, X.-M.; Minas, W.; Orsaria, L.; Roeder, D.; Thompson, C. J. Proteomic Studies of Diauxic Lag in the Differentiating Prokaryote Streptomyces Coelicolor Reveal a Regulatory Network of Stress-Induced Proteins and Central Metabolic Enzymes. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manteca, A.; Mäder, U.; Connolly, B. A.; Sanchez, J. A Proteomic Analysis of Programmed Cell Death. PROTEOMICS 2006, 6, 6008–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenconi, E.; Traxler, M. F.; Hoebreck, C.; van Wezel, G. P.; Rigali, S. Production of Prodiginines Is Part of a Programmed Cell Death Process in Streptomyces Coelicolor. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevciková, B.; Benada, O.; Kofronova, O.; Kormanec, J. Stress-Response Sigma Factor σH Is Essential for Morphological Differentiation of Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2). Arch. Microbiol. 2001, 177, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, G. H.; Viollier, P. H.; Tenor, J.; Marri, L.; Buttner, M. J.; Thompson, C. J. A Connection between Stress and Development in the Multicellular Prokaryote Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 40, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-L.; Fan, K.-Q.; Yang, X.; Lin, Z.-X.; Xu, X.-P.; Yang, K.-Q. CabC, an EF-Hand Calcium-Binding Protein, Is Involved in Ca2+-Mediated Regulation of Spore Germination and Aerial Hypha Formation in Streptomyces Coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 4061–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapham, D. E. Calcium Signaling. Cell 2007, 131, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carafoli, E. Intracellular Calcium Homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1987, 56, 395–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, D. C.; Guragain, M.; Patrauchan, M. Calcium Binding Proteins and Calcium Signaling in Prokaryotes. Cell Calcium 2015, 57, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstad, S.; Futsaether, C. M.; Johnsson, A. Porphyrin Sensitization and Intracellular Calcium Changes in the Prokaryote Propionibacterium Acnes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1997, 40, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthén, M.; Lundgren, T. Intracellular Ca2+ Mobilization and Kinase Activity during Acylated Homoserine Lactone-Dependent Quorum Sensing in Serratia Liquefaciens *. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 6468–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrecilla, I.; Leganés, F.; Bonilla, I.; Fernández-Piñas, F. Use of Recombinant Aequorin to Study Calcium Homeostasis and Monitor Calcium Transients in Response to Heat and Cold Shock in Cyanobacteria1. Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, N. J.; Knight, M. R.; Trewavas, A. J.; Campbell, A. K. Free Calcium Transients in Chemotactic and Non-Chemotactic Strains of Escherichia Coli Determined by Using Recombinant Aequorin. Biochem. J. 1995, 306, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A. K.; Naseem, R.; Wann, K.; Holland, I. B.; Matthews, S. B. Fermentation Product Butane 2,3-Diol Induces Ca2+ Transients in E. Coli through Activation of Lanthanum-Sensitive Ca2+ Channels. Cell Calcium 2007, 41, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A. K.; Naseem, R.; Holland, I. B.; Matthews, S. B.; Wann, K. T. Methylglyoxal and Other Carbohydrate Metabolites Induce Lanthanum-Sensitive Ca2+ Transients and Inhibit Growth in E. Coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 468, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbaud, M.-L.; Guiseppi, A.; Denizot, F.; Haiech, J.; Kilhoffer, M.-C. Calcium Signalling in Bacillus Subtilis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res. 1998, 1448, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.; Wang, C. Calcium Signaling Mechanisms Across Kingdoms. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 37, 311–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, P.; Francisco, R.; Morais, P. V. Potential of Tellurite Resistance in Heterotrophic Bacteria from Mining Environments. iScience 2022, 25, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Lin, S.; Liang, R. Characterization of the Tellurite-Resistance Properties and Identification of the Core Function Genes for Tellurite Resistance in Pseudomonas Citronellolis SJTE-3. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.-K.; Lou, Y.-C.; Chen, C. NMR Solution Structure of KP-TerB, a Tellurite-Resistance Protein from Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Protein Sci. 2008, 17, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Center for Structural Genomics (JCSG). Crystal Structure of Tellurite Resistance Protein of COG3793 (ZP_0010 9916.1) from Nostoc Punctiforme PCC 73102 at 1.85 A Resolution, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P.; Bursać, D.; Law, Y. C.; Cyr, D.; Lithgow, T. The J-protein Family: Modulating Protein Assembly, Disassembly and Translocation. EMBO Rep. 2004, 5, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacinska, A.; van der Laan, M.; Mehnert, C. S.; Guiard, B.; Mick, D. U.; Hutu, D. P.; Truscott, K. N.; Wiedemann, N.; Meisinger, C.; Pfanner, N.; Rehling, P. Distinct Forms of Mitochondrial TOM-TIM Supercomplexes Define Signal-Dependent States of Preprotein Sorting. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dym, O.; Eisenberg, D. Sequence-Structure Analysis of FAD-Containing Proteins. Protein Sci. 2001, 10, 1712–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marbois, B.; Gin, P.; Gulmezian, M.; Clarke, C. F. The Yeast Coq4 Polypeptide Organizes a Mitochondrial Protein Complex Essential for Coenzyme Q Biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2009, 1791, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.-L.; Chauvaux, S.; Dessein, R.; Laurans, C.; Frangeul, L.; Lacroix, C.; Schiavo, A.; Dillies, M.-A.; Foulon, J.; Coppée, J.-Y.; Médigue, C.; Carniel, E.; Simonet, M.; Marceau, M. Growth of Yersinia Pseudotuberculosis in Human Plasma: Impacts on Virulence and Metabolic Gene Expression. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, E.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Kölbl, D.; Chaturvedi, P.; Nakagawa, K.; Yamagishi, A.; Weckwerth, W.; Milojevic, T. Proteometabolomic Response of Deinococcus Radiodurans Exposed to UVC and Vacuum Conditions: Initial Studies Prior to the Tanpopo Space Mission. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Lu, H.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, B.; Wang, L.; Hua, Y. Cyclic AMP Receptor Protein Acts as a Transcription Regulator in Response to Stresses in Deinococcus Radiodurans. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appukuttan, D.; Seo, H. S.; Jeong, S.; Im, S.; Joe, M.; Song, D.; Choi, J.; Lim, S. Expression and Mutational Analysis of DinB-Like Protein DR0053 in Deinococcus Radiodurans. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, B.; Apte, S. K. Gamma Radiation-Induced Proteome of Deinococcus Radiodurans Primarily Targets DNA Repair and Oxidative Stress Alleviation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 2012, 11, M111.011734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Earl, A. M.; Howell, H. A.; Park, M.-J.; Eisen, J. A.; Peterson, S. N.; Battista, J. R. Analysis of Deinococcus Radiodurans’s Transcriptional Response to Ionizing Radiation and Desiccation Reveals Novel Proteins That Contribute to Extreme Radioresistance. Genetics 2004, 168, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormutakova, R.; Klucar, L.; Turna, J. DNA Sequence Analysis of the Tellurite-Resistance Determinant from Clinical Strain of Escherichia Coli and Identification of Essential Genes.

- Toptchieva, A.; Sisson, G.; Bryden, L. J.; Taylor, D. E.; Hoffman, P. S. An Inducible Tellurite-Resistance Operon in Proteus Mirabilis. Microbiology 2003, 149, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeinert, R.; Martinez, E.; Schmitz, J.; Senn, K.; Usman, B.; Anantharaman, V.; Aravind, L.; Waters, L. S. Structure–Function Analysis of Manganese Exporter Proteins across Bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 5715–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsu, B. V.; Saier, M. H. The LysE Superfamily of Transport Proteins Involved in Cell Physiology and Pathogenesis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambach, M.; Sandoval, M.; Updegrove, T. B.; Anantharaman, V.; Aravind, L.; Waters, L. S.; Storz, G. The Ubiquitous yybP-ykoY Riboswitch Is a Manganese-Responsive Regulatory Element. Mol. Cell 2015, 57, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, R. J.; Hall, K. S.; Slonczewski, J. L. Alkaline Induction of a Novel Gene Locus, Alx, in Escherichia Coli. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 2184–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Mishanina, T. V. A Riboswitch-Controlled TerC Family Transporter Alx Tunes Intracellular Manganese Concentration in Escherichia Coli at Alkaline pH. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e00168–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjem, A.; Varghese, S.; Imlay, J. A. Manganese Import Is a Key Element of the OxyR Response to Hydrogen Peroxide in Escherichia Coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 72, 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, J. D.; Culotta, V. C. Battles with Iron: Manganese in Oxidative Stress Protection *. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 13541–13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imlay, J. A. The Mismetallation of Enzymes during Oxidative Stress *. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 28121–28128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. E.; Imlay, J. A. The Alternative Aerobic Ribonucleotide Reductase of Escherichia Coli, NrdEF, Is a Manganese-Dependent Enzyme That Enables Cell Replication during Periods of Iron Starvation. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 80, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breckau, D.; Mahlitz, E.; Sauerwald, A.; Layer, G.; Jahn, D. Oxygen-Dependent Coproporphyrinogen III Oxidase (HemF) from Escherichia Coli Is Stimulated by Manganese *. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 46625–46631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J. E.; Waters, L. S.; Storz, G.; Imlay, J. A. The Escherichia Coli Small Protein MntS and Exporter MntP Optimize the Intracellular Concentration of Manganese. PLOS Genet. 2015, 11, e1004977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Qinyuan; Guo Fang; Huang Li; Wang Mengying; Shi Chunfeng; Zhang Shutong; Yao Yizhou; Wang Mingshu; Zhu Dekang; Jia Renyong; Chen Shun; Zhao Xinxin; Yang Qiao; Wu Ying; Zhang Shaqiu; Tian Bin; Huang Juan; Ou Xumin; Gao Qun; Sun Di; Zhang Ling; Yu Yanling; He Yu; Wu Zhen; Götz Friedrich; Cheng Anchun; Liu Mafeng. Functional Characterization of a TerC Family Protein of Riemerella Anatipestifer in Manganese Detoxification and Virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 90, e01350–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo Fang; Wang Mengying; Huang Mi; Jiang Yin; Gao Qun; Zhu Dekang; Wang Mingshu; Jia Renyong; Chen Shun; Zhao Xinxin; Yang Qiao; Wu Ying; Zhang Shaqiu; Huang Juan; Tian Bin; Ou Xumin; Mao Sai; Sun Di; Cheng Anchun; Liu Mafeng. Manganese Efflux Achieved by MetA and MetB Affects Oxidative Stress Resistance and Iron Homeostasis in Riemerella Anatipestifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e01835–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunenwald, C. M.; Choby, J. E.; Juttukonda, L. J.; Beavers, W. N.; Weiss, A.; Torres, V. J.; Skaar, E. P. Manganese Detoxification by MntE Is Critical for Resistance to Oxidative Stress and Virulence of Staphylococcus Aureus. MBio 2019, 10, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Sachla, A. J.; Helmann, J. D. TerC Proteins Function during Protein Secretion to Metalate Exoenzymes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Shin, J.; Pinochet-Barros, A.; Su, T. T.; Helmann, J. D. Bacillus Subtilis MntR Coordinates the Transcriptional Regulation of Manganese Uptake and Efflux Systems. Mol. Microbiol. 2017, 103, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Helmann, J. D. Metalation of Extracytoplasmic Proteins and Bacterial Cell Envelope Homeostasis. Annual Review of Microbiology, 2024, 78, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunenwald, C. M.; Choby, J. E.; Juttukonda, L. J.; Beavers, W. N.; Weiss, A.; Torres, V. J.; Skaar, E. P. Manganese Detoxification by MntE Is Critical for Resistance to Oxidative Stress and Virulence of Staphylococcus Aureus. mBio 2019, 10, 10.1128–mbio.02915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Vásquez, W. A.; Abarca-Lagunas, M. J.; Arenas, F. A.; Pinto, C. A.; Cornejo, F. A.; Wansapura, P. T.; Appuhamillage, G. A.; Chasteen, T. G.; Vásquez, C. C. Tellurite Reduction by Escherichia Coli NDH-II Dehydrogenase Results in Superoxide Production in Membranes of Toxicant-Exposed Cells. BioMetals 2014, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, J. L.; Boyanov, M. I.; Kemner, K. M.; Yee, N. The Role of Cysteine in Tellurate Reduction and Toxicity. BioMetals 2021, 34, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsetti, F.; Tremaroli, V.; Michelacci, F.; Borghese, R.; Winterstein, C.; Daldal, F.; Zannoni, D. Tellurite Effects on Rhodobacter Capsulatus Cell Viability and Superoxide Dismutase Activity under Oxidative Stress Conditions. Res. Microbiol. 2005, 156, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacenza, E.; Campora, S.; Carfì Pavia, F.; Chillura Martino, D. F.; Laudicina, V. A.; Alduina, R.; Turner, R. J.; Zannoni, D.; Presentato, A. Tolerance, Adaptation, and Cell Response Elicited by Micromonospora Sp. Facing Tellurite Toxicity: A Biological and Physical-Chemical Characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinand Paruthiyil; Azul Pinochet-Barros; Xiaojuan Huang; John D. Helmann; Tina M. Henkin. Bacillus Subtilis TerC Family Proteins Help Prevent Manganese Intoxication. J. Bacteriol. 2020, 202, e00624–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-M. A.; Chu, K.; Palaniappan, K.; Ratner, A.; Huang, J.; Huntemann, M.; Hajek, P.; Ritter, S. J.; Webb, C.; Wu, D.; Varghese, N. J.; Reddy, T. B. K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ovchinnikova, G.; Nolan, M.; Seshadri, R.; Roux, S.; Visel, A.; Woyke, T.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E. A.; Kyrpides, N. C.; Ivanova, N. N. The IMG/M Data Management and Analysis System v.7: Content Updates and New Features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D723–D732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; O’Neill, K. R.; Haft, D. H.; DiCuccio, M.; Chetvernin, V.; Badretdin, A.; Coulouris, G.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M. K.; Durkin, A. S.; Gonzales, N. R.; Gwadz, M.; Lanczycki, C. J.; Song, J. S.; Thanki, N.; Wang, J.; Yamashita, R. A.; Yang, M.; Zheng, C.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Thibaud-Nissen, F. RefSeq: Expanding the Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline Reach with Protein Family Model Curation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1020–D1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprenant, K. A.; Bloom, N.; Fang, J.; Lushington, G. The Major Vault Protein Is Related to the Toxic Anion Resistance Protein(TelA) Family. J. Exp. Biol. 2007, 210, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Zeng, W.; Xiao, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Kong, W.; Zou, J.; Liu, T.; Yin, H. Dissecting the Metal Resistance Genes Contributed by Virome from Mining-Affected Metal Contaminated Soils. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, J. L.; Lui, L. M.; Nielsen, T. N.; Poole, F. L., II; Smith, H. J.; Walker, K. F.; Hazen, T. C.; Fields, M. W.; Arkin, A. P.; Adams, M. W. W. Mixed Waste Contamination Selects for a Mobile Genetic Element Population Enriched in Multiple Heavy Metal Resistance Genes. ISME Commun. 2024, ycae064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C. J.; Bornemann, T. L. V.; Figueroa-Gonzalez, P. A.; Esser, S. P.; Moraru, C.; Soares, A. R.; Hinzke, T.; Trautwein-Schult, A.; Maaß, S.; Becher, D.; Starke, J.; Plewka, J.; Rothe, L.; Probst, A. J. Time-Series Metaproteogenomics of a High-CO2 Aquifer Reveals Active Viruses with Fluctuating Abundances and Broad Host Ranges. microLife 2024, 5, uqae011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decewicz, P.; Dziewit, L.; Golec, P.; Kozlowska, P.; Bartosik, D.; Radlinska, M. Characterization of the Virome of Paracoccus Spp. (Alphaproteobacteria) by Combined in Silico and in Vivo Approaches. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Peng, D.; Fu, C.; Luo, X.; Guo, S.; Li, L.; Yin, H. Pan-Metagenome Reveals the Abiotic Stress Resistome of Cigar Tobacco Phyllosphere Microbiome. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labonté, J. M.; Pachiadaki, M.; Fergusson, E.; McNichol, J.; Grosche, A.; Gulmann, L. K.; Vetriani, C.; Sievert, S. M.; Stepanauskas, R. Single Cell Genomics-Based Analysis of Gene Content and Expression of Prophages in a Diffuse-Flow Deep-Sea Hydrothermal System. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazinas, P.; Smith, C.; Suhaimi, A.; Hobman, J. L.; Dodd, C. E. R.; Millard, A. D. Draft Genome Sequence of the Bacteriophage vB_Eco_slurp01. Genome Announc. 2016, 4, 10.1128–genomea.01111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada Bonilla, B.; Costa, A. R.; Van Den Berg, D. F.; Van Rossum, T.; Hagedoorn, S.; Walinga, H.; Xiao, M.; Song, W.; Haas, P.-J.; Nobrega, F. L. Genomic Characterization of Four Novel Bacteriophages Infecting the Clinical Pathogen Klebsiella Pneumoniae. DNA Res. 2021, 28, dsab013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahlff, J.; Esser, S. P.; Plewka, J.; Heinrichs, M. E.; Soares, A.; Scarchilli, C.; Grigioni, P.; Wex, H.; Giebel, H.-A.; Probst, A. J. Marine Viruses Disperse Bidirectionally along the Natural Water Cycle. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, N.; Hamada-Zhu, S.; Suzuki, H. Prophages and Plasmids Can Display Opposite Trends in the Types of Accessory Genes They Carry. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 290, 20231088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, M. J.; Czyż, D. M. Phage against the Machine: The SIE-Ence of Superinfection Exclusion. Viruses 2024, 16, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy-Denomy, J.; Qian, J.; Westra, E. R.; Buckling, A.; Guttman, D. S.; Davidson, A. R.; Maxwell, K. L. Prophages Mediate Defense against Phage Infection through Diverse Mechanisms. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2854–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick-Brenzinger, M.; Liu, M.; Winstone, T. L.; Taylor, D. E.; Turner, R. J. The Role of Cysteine Residues in Tellurite Resistance Mediated by the TehAB Determinant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 277, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasteen, T. G.; Bentley, R. Biomethylation of Selenium and Tellurium: Microorganisms and Plants. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piacenza, E.; Campora, S.; Carfì Pavia, F.; Chillura Martino, D. F.; Laudicina, V. A.; Alduina, R.; Turner, R. J.; Zannoni, D.; Presentato, A. Tolerance, Adaptation, and Cell Response Elicited by Micromonospora Sp. Facing Tellurite Toxicity: A Biological and Physical-Chemical Characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Quiroz, R. C.; Loyola, D. E.; Muñoz-Villagrán, C. M.; Quatrini, R.; Vásquez, C. C.; Pérez-Donoso, J. M. DNA, Cell Wall and General Oxidative Damage Underlie the Tellurite/Cefotaxime Synergistic Effect in Escherichia Coli. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e79499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J. M.; Calderón, I. L.; Arenas, F. A.; Fuentes, D. E.; Pradenas, G. A.; Fuentes, E. L.; Sandoval, J. M.; Castro, M. E.; Elías, A. O.; Vásquez, C. C. Bacterial Toxicity of Potassium Tellurite: Unveiling an Ancient Enigma. PloS One 2007, 2, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkovicova, L.; Smidak, R.; Jung, G.; Turna, J.; Lubec, G.; Aradska, J. Proteomic Analysis of the TerC Interactome: Novel Links to Tellurite Resistance and Pathogenicity. J. Proteomics 2016, 136, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D. E.; Ruebush, S. S.; Brantley, S. L.; Hartshorne, R. S.; Clarke, T. A.; Richardson, D. J.; Tien, M. Characterization of Protein-Protein Interactions Involved in Iron Reduction by Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5797–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R. J.; Taylor, D. E.; Weiner, J. H. Expression of Escherichia Coli TehA Gives Resistance to Antiseptics and Disinfectants Similar to That Conferred by Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pumps. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genome Hits: “protein name” (% total) | Genome Hits: “protein name” + “tellurite”/“tellurium” (% total) | |

|---|---|---|

| ter gene products | ||

| TerZ | 10,506 (7.6%) | 10,347 (7.5%) |

| TerA | 11,237 (8.2%) | 11,221 (8.2%) |

| TerB | 19,633 (14.3%) | 17,809 (12.9%) |

| TerC | 112,963 (82.1%) | 91,432 (66.5%) |

| TerD | 19,266 (14.0%) | 17,415 (12.7%) |

| TerE | 45 (0.03%) | 28 (0.02%) |

| TerF | 1,895 (1.4%) | 7 (0.005%) |

| teh gene products | ||

| TehA | 11,682 (8.5%) | 11,679 (8.5%) |

| TehB | 2,495 (1.8%) | 2,493 (1.8%) |

| tel gene products | ||

| TelA | 557 (0.4%) | 11 (0.008%) |

| TelB | No hits | No hits |

| trg gene products | ||

| TrgA | 8 (0.006%) | 5 (0.004%) |

| TrgB | 11 (0.008%) | 8 (0.006%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).