Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

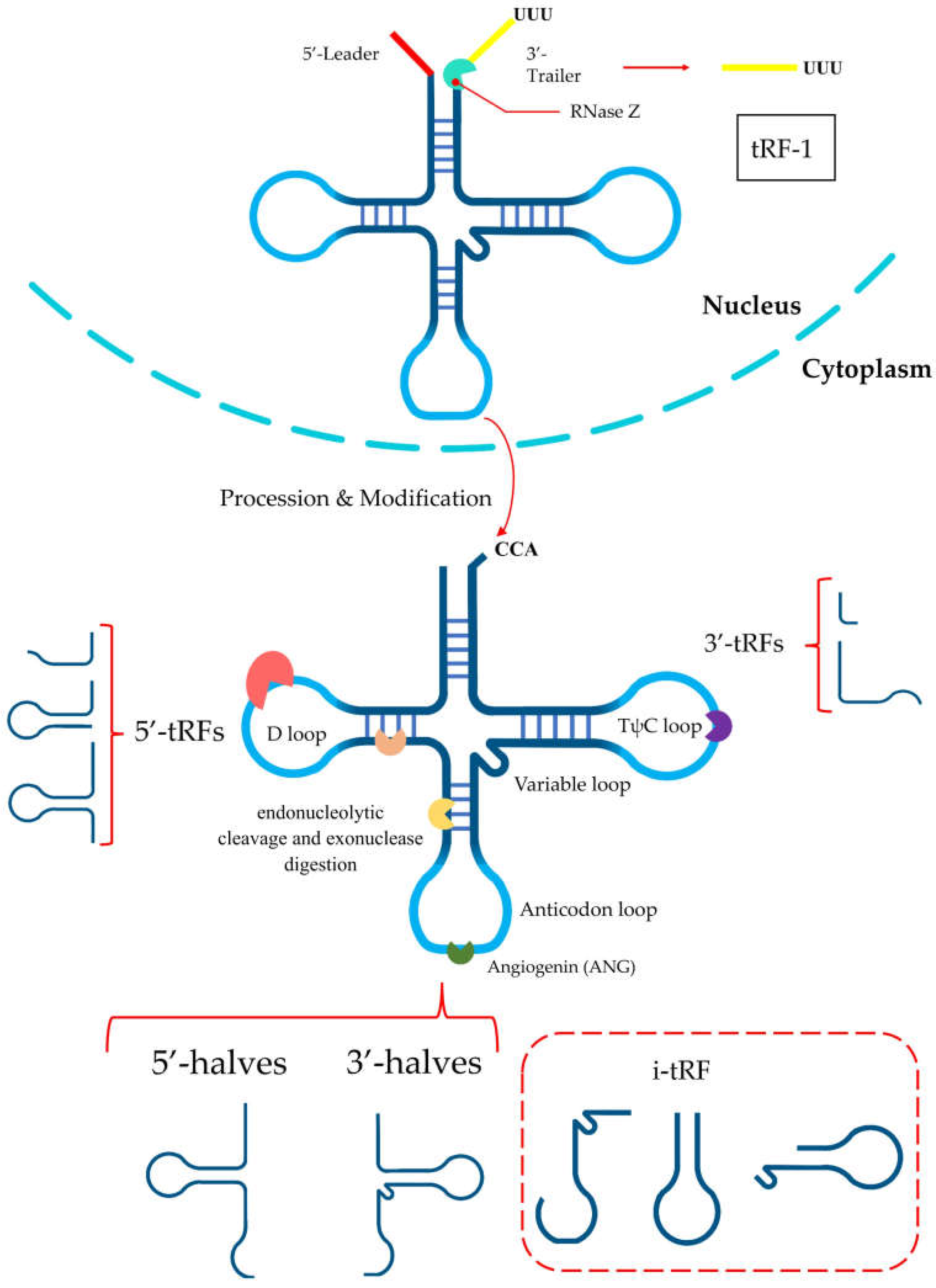

2. Biogenesis and Classification

3. Biological Functions of tRFs

3.1. RNA Silencing

3.2. Translational Regulation

3.3. Epigenetic Regulation

3.4. Reverse-Transcriptional Regulation

3.5. Cellular Apoptosis

4.1. Breast Cancer

4.2. Prostate Cancer

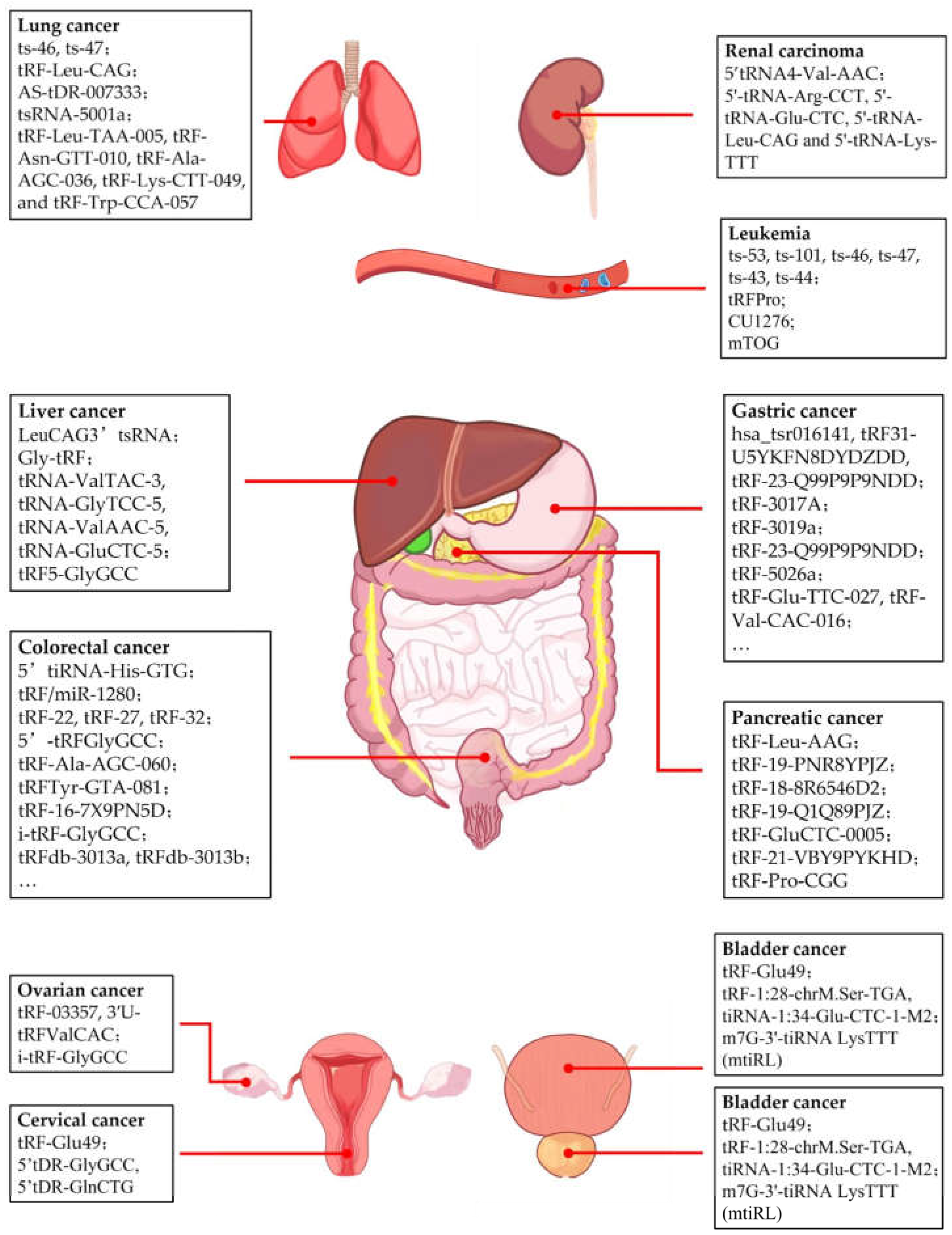

4.3. Pancreatic Cancer

4.4. Liver Cancer

4.5. Gastric Cancer

4.6. Colorectal Cancer

4.7. Leukemia

4.8. Lung Cancer

4.9. Other Cancers

| Cancer type | tRF name | Role | Function | Ref |

| Breast cancer (BC) | tRF-ArgCCT-017, tRF-Gly-CCC-001, tiRNA-Phe-GAA-003 | upregulate in BC plasma samples | potential biomarker of BC | [73] |

| tRF-19-W4PU732S | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation and malignance of BC and suppress apoptosis by inhibiting RPL27A | [74] | |

| 5′-SHOT-RNA | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation of BC | [75] | |

| ts-112 | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation of BC | [76] | |

| tRF-33 | oncogenic factor | disrupt mitochondrial homeostasis and promote progression of BC by interacting with IGF1 | [77] | |

| tRFGlu, tRFAsp, tRFGly, tRFTyr | tumor suppressor | inhibit metastasis of BC via YBX1 displacement | [78,79] | |

| 5′-tiRNAVal | tumor suppressor | inhibit the FZD3-mediated Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway in BC | [80] | |

| tRF3E | tumor suppressor | inhibit proliferation of BC through NCL-mediated mechanism | [81] | |

| tDR-000620 | downregulate in TNBC CSCs and serum sample | potential biomarker of TNBC | [82] | |

| tRFLys-CTT-010 | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation of TNBC by regulating glucose metabolism via tRFLys-CTT-010/G6PC axis | [83] | |

| tDR-0009 and tDR-7336 | drug-resistance driver | facilitate doxorubicin resistance in TNBC | [84] | |

| tRF-27 | oncogenic factordrug-resistance driver | facilitate trastuzumab resistance and promote cell proliferation in BC | [86] | |

| 3’tRF-AlaAGC | drug-resistance driver | enhance the Adriamycin sensitivity in BC via NF-κb signaling pathway by silencing 3’tRF-AlaAGC | [87] | |

| Prostate cancer (PCa) | tRF-1001 | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation of PCa | [23] |

| 5′-SHOT-RNA | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation of PCa | [75] | |

| tRF-315 | drug-resistance driver | facilitate cisplatin resistance in PCa | [92] | |

| 5′TOGs | tumor suppressor | inhibit proliferation of PCa | [93] | |

| Pancreatic cancer (PC) | tRF-Leu-AAG | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation, migration, and invasion of PC by downregulating UPF1 | [94] |

| tRF-19-PNR8YPJZ | oncogenic factor | promote migration and invasion of PC via AXIN2 axis | [95] | |

| tRF-18-8R6546D2 | oncogenic factor | promote malignancy of PC by silencing ASCL2 and regulating MYC and CASP3 | [96] | |

| tRF-19-Q1Q89PJZ | tumor suppressor | inhibit proliferation and metastasis of PC by suppressing HK1 | [97] | |

| expression | [97] | |||

| tRF-GluCTC-0005 | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation, migration and invasion of PDAC and liver metastasis | [98,99] | |

| tRF-21-VBY9PYKHD | tumor suppressor | promote proliferation, migration, and invasion of PDCA when downregulated | [70] | |

| tRF-Pro-CGG | downregulate in advanced PC | potential biomarker of PC | [100] | |

| Liver cancer | LeuCAG3’tsRNA | oncogenic factor | increase viability of HCT-116 cell by interacting with RPS28 and RPS15 | [51] |

| Gly-tRF | oncogenic factor | increase LCSC subpopulation proportion and promote EMT in liver cancer | [101,102] | |

| tRNA-ValTAC-3, tRNA-GlyTCC-5, tRNA-ValAAC-5, tRNA-GluCTC-5 | upregulate in liver cancer | potential biomarker of liver cancer | [104] | |

| tRF5-GlyGCC | radiotherapy inhibitor | reduce NK cell cytotoxicity and limit radiotherapeutic efficacy | [109] | |

| Gastric cancer (GC) | hsa_tsr016141, tRF31-U5YKFN8DYDZDD, tRF-23-Q99P9P9NDD | oncogenic factor | upregulation is associated with tumor grade, lymph node metastasis and invasion | [110,111.112] |

| tRF-3017A | oncogenic factor | promote migration and invasion of GC by targeting NELL2 | [9] | |

| tRF-3019a | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation, migration and invasion of GC | [113] | |

| tRF-23-Q99P9P9NDD | oncogenic factor | promote progression of GC by affecting lipid metabolism and ferroptosis via targeting ACADSB | [114] | |

| tRF-33-P4R8YP9LON4VDP, tRF-193L7L73JD | tumor suppressor | inhibit proliferation of GC by disrupting cell cycle | [115,116] | |

| tRF-5026a | tumor suppressor | inhibit progression of GC via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and regulate cell cycle | [117] | |

| tRF-Glu-TTC-027, tRF-Val-CAC-016 | tumor suppressor | inhibit malignance of GC via MAPK pathway | [118,119] | |

| tRF-Tyr | tumor suppressor | inhibit progression of GC via c-Myc/Bcl2/Bax pathway | [120] | |

| tRF-Val | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation and invasion and inhibit cell apoptosis of GC | [121] | |

| Colorectal cancer (CRC) | 5’tiRNA-His-GTG | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation and inhibit cell apoptosis of CRC | [122] |

| tRF/miR-1280 | oncogenic factor | promoting proliferation and metastasis of CRC via Notch | [123] | |

| signal pathway | [123] | |||

| 5’tiRNA-Gly-GCC | drug-resistance driver | facilitate 5-FU resistance in CRC | [124] | |

| tRF-20M0NK5Y93 | tumor suppressor | inhibit metastasis of CRC by suppressing Claudin-1 | [125] | |

| tRF-22, tRF-27, tRF-32 | upregulate in CRC tissue and plasma samples | potential biomarker of CRC | [126] | |

| 5’-tRFGlyGCC | upregulate in CRC plasma samples | potential biomarker of CRC | [127] | |

| tRF-Ala-AGC-060 | upregulate in CRC tissue samples | potential biomarker of CRC | [128] | |

| tRFTyr-GTA-081 | downregulate in CRC tissue samples | potential biomarker of CRC | [128] | |

| tRF-16-7X9PN5D | radiosensitizer | promote proliferation, migration, invasion and radio resistance when downregulated | [129] | |

| 5’-tRF-Leu (CAA) | tumor suppressor | inhibit progression of CRC | [133] | |

| i-tRF-GlyGCC | downregulate in CRC tissue samples | potential biomarker of CRC | [134] | |

| tRFdb-3013a, tRFdb-3013b | downregulate in colon and rectum adenocarcinomas | potential biomarker of CRC | [135] | |

| Leukemia | ts-53, ts-101, ts-46, and ts-47, ts-43, ts-44 | tumor suppressor | promote progression of CLL | [72,136,137] |

| tRFPro | RT primer of HTLV-1 | potential target for preventing ATLL | [138] | |

| CU1276 | tumor suppressor | inhibit proliferation and molecularly modulate DNA damage repair | [139] | |

| mTOG | dysregulation associated with leukemic transformation | potential biomarker for MDS transformation to AML | [140] | |

| Lung cancer | ts-46, ts-47 | tumor suppressor | inhibit proliferation of lung cancer cell lines when upregulated | [136] |

| tRF-Leu-CAG | oncogenic factorupregulated in NSCLC tissues and cell lines | inhibit proliferation and impede cell cycle of NSCLCpotential biomarker of NSCLC | [141] | |

| AS-tDR-007333 | oncogenic factorupregulated in NSCLC tissues and plasma | promote proliferation and migration of NSCLCpotential biomarker of NSCLC | [142] | |

| tsRNA-5001a | upregulated in lung adenocarcinoma tissues | potential biomarker for poor prognosis | [143] | |

| tRF-Leu-TAA-005, tRF-Asn-GTT-010, tRF-Ala-AGC-036, tRF-Lys-CTT-049, and tRF-Trp-CCA-057 | downregulated in NSCLC tissues | potential biomarker of NSCLC | [145] | |

| ovarian cancer | tRF-03357, 3′U-tRFValCAC | oncogenic factor | promote proliferation, migration and invasion of SK-OV-3 cell | [146,147] |

| i-tRF-GlyGCC | upregulation is associated with advanced FIGO stages | potential biomarker of ovarian cancer | [148] | |

| cervical cancer | tRF-Glu49 | tumor suppressor | inhibit proliferation of cervical carcinoma by regulating FGL1 | [149] |

| 5’tDR-GlyGCC, 5’tDR-GlnCTG | oncogenic factor | promote progression of cervical cancer | [150] | |

| bladder cancer | 5’-tRF-LysCTT | upregulation is associated with poor prognosis | potential biomarker of bladder cancer | [151] |

| tRF-1:28-chrM.Ser-TGA, tiRNA-1:34-Glu-CTC-1-M2 | oncogenic factor | promote malignancy of bladder cancer | [152] | |

| m7G-3’-tiRNA LysTTT (mtiRL) | oncogenic factor | promote malignancy of bladder cancer | [153] | |

| renal carcinoma | 5’tRNA4-Val-AAC | downregulation is associated with advanced stage | potential biomarker of ccRCC | [154] |

| 5’-tRNA-Arg-CCT, 5’-tRNA-Glu-CTC, 5’-tRNA-Leu-CAG and 5’-tRNA-Lys-TTT | downregulated in tumor tissues and serum samples | potential biomarker of ccRCC | [155] |

5. Conclusions and Perspective

References

- Yu M, Lu B, Zhang J, Ding J, Liu P, Lu Y. tRNA-derived RNA fragments in cancer: current status and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2020 Sep 4;13(1):121. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Zhang J, Diao L, Han L. Small non-coding RNAs in human cancer: function, clinical utility, and characterization. Oncogene. 2021 Mar;40(9):1570-1577. [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou E, Jacob LS, Slack FJ. Non-coding RNA networks in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018 Jan;18(1):5-18.

- Cech TR, Steitz JA. The noncoding RNA revolution-trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell. 2014 Mar 27;157(1):77-94. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Anaya J, Mudunuri SB, Dutta A. Meta-analysis of tRNA derived RNA fragments reveals that they are evolutionarily conserved and associate with AGO proteins to recognize specific RNA targets. BMC Biol. 2014 Oct 1;12:78.

- Shen Y, Yu X, Zhu L, Li T, Yan Z, Guo J. Transfer RNA-derived fragments and tRNA halves: biogenesis, biological functions and their roles in diseases. J Mol Med (Berl). 2018 Nov;96(11):1167-1176. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Kuscu C, Dutta A. Biogenesis and Function of Transfer RNA-Related Fragments (tRFs). Trends Biochem Sci. 2016 Aug;41(8):679-689. [CrossRef]

- Pan Y, Ying X, Zhang X, Jiang H, Yan J, Duan S. The role of tRNA-Derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) in pancreatic cancer and acute pancreatitis. Noncoding RNA Res. 2024 Dec 30;11:200-208. [CrossRef]

- Tong L, Zhang W, Qu B, Zhang F, Wu Z, Shi J, Chen X, Song Y, Wang Z. The tRNA-Derived Fragment-3017A Promotes Metastasis by Inhibiting NELL2 in Human Gastric Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021 Feb 16;10:570916. [CrossRef]

- Qiu P, Jiang Q, Song H. Unveiling the hidden world of transfer RNA-derived small RNAs in inflammation. J Inflamm (Lond). 2024 Nov 12;21(1):46. [CrossRef]

- Weng Q, Wang Y, Xie Y, Yu X, Zhang S, Ge J, Li Z, Ye G, Guo J. Extracellular vesicles-associated tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs): biogenesis, biological functions, and their role as potential biomarkers in human diseases. J Mol Med (Berl). 2022 May;100(5):679-695. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Silva MR, Cabrera-Cabrera F, das Neves RF, Souto-Padrón T, de Souza W, Cayota A. Gene expression changes induced by Trypanosoma cruzi shed microvesicles in mammalian host cells: relevance of tRNA-derived halves. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:305239. [CrossRef]

- Deng J, Ptashkin RN, Chen Y, Cheng Z, Liu G, Phan T, Deng X, Zhou J, Lee I, Lee YS, Bao X. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Utilizes a tRNA Fragment to Suppress Antiviral Responses Through a Novel Targeting Mechanism. Mol Ther. 2015 Oct;23(10):1622-9. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Ender C, Meister G, Moore PS, Chang Y, John B. Extensive terminal and asymmetric processing of small RNAs from rRNAs, snoRNAs, snRNAs, and tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Aug;40(14):6787-99. [CrossRef]

- Schaffer AE, Eggens VR, Caglayan AO, Reuter MS, Scott E, Coufal NG, Silhavy JL, Xue Y, Kayserili H, Yasuno K, Rosti RO, Abdellateef M, Caglar C, Kasher PR, Cazemier JL, Weterman MA, Cantagrel V, Cai N, Zweier C, Altunoglu U, Satkin NB, Aktar F, Tuysuz B, Yalcinkaya C, Caksen H, Bilguvar K, Fu XD, Trotta CR, Gabriel S, Reis A, Gunel M, Baas F, Gleeson JG. CLP1 founder mutation links tRNA splicing and maturation to cerebellar development and neurodegeneration. Cell. 2014 Apr 24;157(3):651-63. [CrossRef]

- Tian H, Hu Z, Wang C. The Therapeutic Potential of tRNA-derived Small RNAs in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Aging Dis. 2022 Apr 1;13(2):389-401. [CrossRef]

- Phan HD, Lai LB, Zahurancik WJ, Gopalan V. The many faces of RNA-based RNase P, an RNA-world relic. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021 Dec;46(12):976-991. [CrossRef]

- Maraia RJ, Lamichhane TN. 3’ processing of eukaryotic precursor tRNAs. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011 May-Jun;2(3):362-75.

- Xiong Y, Steitz TA. A story with a good ending: tRNA 3’-end maturation by CCA-adding enzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006 Feb;16(1):12-7. [CrossRef]

- Holley RW, Apgar J, Everett GA, Madison JT, Marquisee M, Merrill SH, et al. STRUCTURE OF A RIBONUCLEIC ACID. Science. 1965 Mar 19;147(3664):1462-5.

- Suzuki T. The expanding world of tRNA modifications and their disease relevance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021 Jun;22(6):375-392. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Mo Y, Ren D, Liu S, Zeng Z, Xiong W. Transfer RNA-derived small RNAs in tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 2023 Feb 16;22(1):32. [CrossRef]

- Lee YS, Shibata Y, Malhotra A, Dutta A. A novel class of small RNAs: tRNA-derived RNA fragments (tRFs). Genes Dev. 2009 Nov 15;23(22):2639-49. [CrossRef]

- Fu BF, Xu CY. Transfer RNA-Derived Small RNAs: Novel Regulators and Biomarkers of Cancers. Front Oncol. 2022 Apr 28;12:843598. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Mudunuri SB, Anaya J, Dutta A. tRFdb: a database for transfer RNA fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 Jan;43(Database issue):D141-5. [CrossRef]

- Tao EW, Cheng WY, Li WL, Yu J, Gao QY. tiRNAs: A novel class of small noncoding RNAs that helps cells respond to stressors and plays roles in cancer progression. J Cell Physiol. 2020 Feb;235(2):683-690. [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Zhu P, Zhang X, Zeng L, Xu B, Zhou P. tRNA-derived fragments: Unveiling new roles and molecular mechanisms in cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 2024 Oct 15;155(8):1347-1360. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y, Yao L, Yu X, Ruan Y, Li Z, Guo J. Action mechanisms and research methods of tRNA-derived small RNAs. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020 Jun 30;5(1):109. [CrossRef]

- Cole C, Sobala A, Lu C, Thatcher SR, Bowman A, Brown JW, Green PJ, Barton GJ, Hutvagner G. Filtering of deep sequencing data reveals the existence of abundant Dicer-dependent small RNAs derived from tRNAs. RNA. 2009 Dec;15(12):2147-60.

- Telonis AG, Loher P, Magee R, Pliatsika V, Londin E, Kirino Y, Rigoutsos I. tRNA Fragments Show Intertwining with mRNAs of Specific Repeat Content and Have Links to Disparities. Cancer Res. 2019 Jun 15;79(12):3034-3049.

- Goodarzi H, Liu X, Nguyen HC, Zhang S, Fish L, Tavazoie SF. Endogenous tRNA-Derived Fragments Suppress Breast Cancer Progression via YBX1 Displacement. Cell. 2015 May 7;161(4):790-802. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki S, Ivanov P, Hu GF, Anderson P. Angiogenin cleaves tRNA and promotes stress-induced translational repression. J Cell Biol. 2009 Apr 6;185(1):35-42. [CrossRef]

- Thompson DM, Parker R. Stressing out over tRNA cleavage. Cell. 2009 Jul 23;138(2):215-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Chen Y, Ren Y, Zhou J, Ren J, Lee I, Bao X. A tRNA-derived RNA Fragment Plays an Important Role in the Mechanism of Arsenite -induced Cellular Responses. Sci Rep. 2018 Nov 15;8(1):16838. [CrossRef]

- Tao EW, Wang HL, Cheng WY, Liu QQ, Chen YX, Gao QY. A specific tRNA half, 5’tiRNA-His-GTG, responds to hypoxia via the HIF1α/ANG axis and promotes colorectal cancer progression by regulating LATS2. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021 Feb 15;40(1):67.

- Su Z, Kuscu C, Malik A, Shibata E, Dutta A. Angiogenin generates specific stress-induced tRNA halves and is not involved in tRF-3-mediated gene silencing. J Biol Chem. 2019 Nov 8;294(45):16930-16941. [CrossRef]

- Blanco S, Dietmann S, Flores JV, Hussain S, Kutter C, Humphreys P, et al. Aberrant methylation of tRNAs links cellular stress to neuro-developmental disorders. EMBO J. 2014 Sep 17;33(18):2020-39. [CrossRef]

- Haussecker D, Huang Y, Lau A, Parameswaran P, Fire AZ, Kay MA. Human tRNA-derived small RNAs in the global regulation of RNA silencing. RNA. 2010 Apr;16(4):673-95. [CrossRef]

- Kim HK, Yeom JH, Kay MA. Transfer RNA-Derived Small RNAs: Another Layer of Gene Regulation and Novel Targets for Disease Therapeutics. Mol Ther. 2020 Nov 4;28(11):2340-2357. [CrossRef]

- Sobala A, Hutvagner G. Transfer RNA-derived fragments: origins, processing, and functions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011 Nov-Dec;2(6):853-62.

- Green JA, Ansari MY, Ball HC, Haqqi TM. tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) regulate post-transcriptional gene expression via AGO-dependent mechanism in IL-1β stimulated chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020 Aug;28(8):1102-1110. [CrossRef]

- Di Fazio A, Schlackow M, Pong SK, Alagia A, Gullerova M. Dicer dependent tRNA derived small RNAs promote nascent RNA silencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Feb 22;50(3):1734-1752. [CrossRef]

- Cho H, Lee W, Kim GW, Lee SH, Moon JS, Kim M, Kim HS, Oh JW. Regulation of La/SSB-dependent viral gene expression by pre-tRNA 3’ trailer-derived tRNA fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 Oct 10;47(18):9888-9901. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011 Aug 19;43(4):613-23. [CrossRef]

- Lyons SM, Gudanis D, Coyne SM, Gdaniec Z, Ivanov P. Identification of functional tetramolecular RNA G-quadruplexes derived from transfer RNAs. Nat Commun. 2017 Oct 24;8(1):1127. Erratum in: Nat Commun. 2017 Dec 5;8(1):2020. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov P, O’Day E, Emara MM, Wagner G, Lieberman J, Anderson P. G-quadruplex structures contribute to the neuroprotective effects of angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Dec 23;111(51):18201-6. [CrossRef]

- Lyons SM, Kharel P, Akiyama Y, Ojha S, Dave D, Tsvetkov V, Merrick W, Ivanov P, Anderson P. eIF4G has intrinsic G-quadruplex binding activity that is required for tiRNA function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020 Jun 19;48(11):6223-6233. [CrossRef]

- Emara MM, Ivanov P, Hickman T, Dawra N, Tisdale S, Kedersha N, Hu GF, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs promote stress-induced stress granule assembly. J Biol Chem. 2010 Apr 2;285(14):10959-68. [CrossRef]

- Guzzi N, Cieśla M, Ngoc PCT, Lang S, Arora S, Dimitriou M, et al. Pseudouridylation of tRNA-Derived Fragments Steers Translational Control in Stem Cells. Cell. 2018 May 17;173(5):1204-1216.e26. [CrossRef]

- Sobala A, Hutvagner G. Small RNAs derived from the 5’ end of tRNA can inhibit protein translation in human cells. RNA Biol. 2013 Apr;10(4):553-63. [CrossRef]

- Kim HK, Fuchs G, Wang S, Wei W, Zhang Y, Park H, Roy-Chaudhuri B, Li P, Xu J, Chu K, Zhang F, Chua MS, So S, Zhang QC, Sarnow P, Kay MA. A transfer-RNA-derived small RNA regulates ribosome biogenesis. Nature. 2017 Dec 7;552(7683):57-62. [CrossRef]

- Henikoff S, Greally JM. Epigenetics, cellular memory and gene regulation. Curr Biol. 2016 Jul 25;26(14):R644-8. [CrossRef]

- Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 2012 Jul 6;150(1):12-27.

- Yu T, Huang X, Dou S, Tang X, Luo S, Theurkauf WE, Lu J, Weng Z. A benchmark and an algorithm for detecting germline transposon insertions and measuring de novo transposon insertion frequencies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021 May 7;49(8):e44. [CrossRef]

- Slotkin RK, Martienssen R. Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2007 Apr;8(4):272-85. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe T, Tomizawa S, Mitsuya K, Totoki Y, Yamamoto Y, Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Iida N, Hoki Y, Murphy PJ, Toyoda A, Gotoh K, Hiura H, Arima T, Fujiyama A, Sado T, Shibata T, Nakano T, Lin H, Ichiyanagi K, Soloway PD, Sasaki H. Role for piRNAs and noncoding RNA in de novo DNA methylation of the imprinted mouse Rasgrf1 locus. Science. 2011 May 13;332(6031):848-52. [CrossRef]

- Fields BD, Kennedy S. Chromatin Compaction by Small RNAs and the Nuclear RNAi Machinery in C. elegans. Sci Rep. 2019 Jun 21;9(1):9030. [CrossRef]

- Couvillion MT, Bounova G, Purdom E, Speed TP, Collins K. A Tetrahymena Piwi bound to mature tRNA 3’ fragments activates the exonuclease Xrn2 for RNA processing in the nucleus. Mol Cell. 2012 Nov 30;48(4):509-20. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, He X, Liu C, Liu J, Hu Q, Pan T, Duan X, Liu B, Zhang Y, Chen J, Ma X, Zhang X, Luo H, Zhang H. IL-4 Inhibits the Biogenesis of an Epigenetically Suppressive PIWI-Interacting RNA To Upregulate CD1a Molecules on Monocytes/Dendritic Cells. J Immunol. 2016 Feb 15;196(4):1591-603. [CrossRef]

- Zhang B, Pan Y, Li Z, Hu K. tRNA-derived small RNAs: their role in the mechanisms, biomarkers, and therapeutic strategies of colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 2025 Jan 13;23(1):51. [CrossRef]

- Schorn AJ, Gutbrod MJ, LeBlanc C, Martienssen R. LTR-Retrotransposon Control by tRNA-Derived Small RNAs. Cell. 2017 Jun 29;170(1):61-71.e11. [CrossRef]

- Manivannan AC, Devaraju V, Velmurugan P, Sathiamoorthi T, Sivakumar S, Subbiah SK, Ravi AV. Tumorigenesis and diagnostic practice applied in two oncogenic viruses: Epstein Barr virus and T-cell lymphotropic virus-1-Mini review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Oct;142:111974. [CrossRef]

- Ruggero K, Guffanti A, Corradin A, Sharma VK, De Bellis G, Corti G, Grassi A, Zanovello P, Bronte V, Ciminale V, D’Agostino DM. Small noncoding RNAs in cells transformed by human T-cell leukemia virus type 1: a role for a tRNA fragment as a primer for reverse transcriptase. J Virol. 2014 Apr;88(7):3612-22. [CrossRef]

- Seiki M, Hattori S, Yoshida M. Human adult T-cell leukemia virus: molecular cloning of the provirus DNA and the unique terminal structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Nov;79(22):6899-902. [CrossRef]

- Mei Y, Yong J, Liu H, Shi Y, Meinkoth J, Dreyfuss G, Yang X. tRNA binds to cytochrome c and inhibits caspase activation. Mol Cell. 2010 Mar 12;37(5):668-78. [CrossRef]

- Mei Y, Stonestrom A, Hou YM, Yang X. Apoptotic regulation and tRNA. Protein Cell. 2010 Sep;1(9):795-801. [CrossRef]

- Hou YM, Yang X. Regulation of cell death by transfer RNA. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013 Aug 20;19(6):583-94. [CrossRef]

- Saikia M, Jobava R, Parisien M, Putnam A, Krokowski D, Gao XH, Guan BJ, Yuan Y, Jankowsky E, Feng Z, Hu GF, Pusztai-Carey M, Gorla M, Sepuri NB, Pan T, Hatzoglou M. Angiogenin-cleaved tRNA halves interact with cytochrome c, protecting cells from apoptosis during osmotic stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2014 Jul;34(13):2450-63.

- Lu S, Wei X, Tao L, Dong D, Hu W, Zhang Q, Tao Y, Yu C, Sun D, Cheng H. A novel tRNA-derived fragment tRF-3022b modulates cell apoptosis and M2 macrophage polarization via binding to cytokines in colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2022 Dec 16;15(1):176. [CrossRef]

- Pan L, Huang X, Liu ZX, Ye Y, Li R, Zhang J, Wu G, Bai R, Zhuang L, Wei L, Li M, Zheng Y, Su J, Deng J, Deng S, Zeng L, Zhang S, Wu C, Che X, Wang C, Chen R, Lin D, Zheng J. Inflammatory cytokine-regulated tRNA-derived fragment tRF-21 suppresses pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression. J Clin Invest. 2021 Nov 15;131(22):e148130. [CrossRef]

- [bz]Pekarsky Y, Balatti V, Palamarchuk A, Rizzotto L, Veneziano D, Nigita G, Rassenti LZ, Pass HI, Kipps TJ, Liu CG, Croce CM. Dysregulation of a family of short noncoding RNAs, tsRNAs, in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 May 3;113(18):5071-6. [CrossRef]

- Balatti V, Nigita G, Veneziano D, Drusco A, Stein GS, Messier TL, et al. tsRNA signatures in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Jul 25;114(30):8071-8076.

- Wang J, Ma G, Ge H, Han X, Mao X, Wang X, Veeramootoo JS, Xia T, Liu X, Wang S. Circulating tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) signature for the diagnosis and prognosis of breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021 Jan 5;7(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Liu Z, Zhao W, Zhao X, Tao Y. tRF-19-W4PU732S promotes breast cancer cell malignant activity by targeting inhibition of RPL27A (ribosomal protein-L27A). Bioengineered. 2022 Feb;13(2):2087-2098. [CrossRef]

- Honda S, Loher P, Shigematsu M, Palazzo JP, Suzuki R, Imoto I, Rigoutsos I, Kirino Y. Sex hormone-dependent tRNA halves enhance cell proliferation in breast and prostate cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Jul 21;112(29):E3816-25. [CrossRef]

- Farina NH, Scalia S, Adams CE, Hong D, Fritz AJ, Messier TL, Balatti V, Veneziano D, Lian JB, Croce CM, Stein GS, Stein JL. Identification of tRNA-derived small RNA (tsRNA) responsive to the tumor suppressor, RUNX1, in breast cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2020 Jun;235(6):5318-5327.

- Lou Y, Fu B, Liu L, Song J, Zhu M, Xu C. The tRF-33/IGF1 axis dysregulates mitochondrial homeostasis in HER2-negative breast cancer. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2025 Feb 1;328(2):C627-C638. [CrossRef]

- Jürchott K, Kuban RJ, Krech T, Blüthgen N, Stein U, Walther W, Friese C, Kiełbasa SM, Ungethüm U, Lund P, et al. Identification of Y-box binding protein 1 as a core regulator of MEK/ERK pathway-dependent gene signatures in colorectal cancer cells. PLoS Genet. 2010 Dec 2;6(12):e1001231. [CrossRef]

- Uchiumi T, Fotovati A, Sasaguri T, Shibahara K, Shimada T, Fukuda T, Nakamura T, Izumi H, Tsuzuki T, Kuwano M, Kohno K. YB-1 is important for an early stage embryonic development: neural tube formation and cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2006 Dec 29;281(52):40440-9.

- Mo D, Jiang P, Yang Y, Mao X, Tan X, Tang X, Wei D, Li B, Wang X, Tang L, Yan F. A tRNA fragment, 5’-tiRNAVal, suppresses the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by targeting FZD3 in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019 Aug 10;457:60-73.

- Falconi M, Giangrossi M, Zabaleta ME, Wang J, Gambini V, Tilio M, Bencardino D, Occhipinti S, Belletti B, Laudadio E, Galeazzi R, Marchini C, Amici A. A novel 3’-tRNAGlu-derived fragment acts as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer by targeting nucleolin. FASEB J. 2019 Dec;33(12):13228-13240.

- Feng W, Li Y, Chu J, Li J, Zhang Y, Ding X, Fu Z, Li W, Huang X, Yin Y. Identification of tRNA-derived small noncoding RNAs as potential biomarkers for prediction of recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2018 Oct;7(10):5130-5144. [CrossRef]

- Zhu P, Lu J, Zhi X, Zhou Y, Wang X, Wang C, Gao Y, Zhang X, Yu J, Sun Y, Zhou P. tRNA-derived fragment tRFLys-CTT-010 promotes triple-negative breast cancer progression by regulating glucose metabolism via G6PC. Carcinogenesis. 2021 Oct 5;42(9):1196-1207. Erratum in: Carcinogenesis. 2022 Sep 19;43(8):813. [CrossRef]

- Cui Y, Huang Y, Wu X, Zheng M, Xia Y, Fu Z, Ge H, Wang S, Xie H. Hypoxia-induced tRNA-derived fragments, novel regulatory factor for doxorubicin resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2019 Jun;234(6):8740-8751.

- Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000 Apr;6(4):443-6. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Liu Y, Gong J, Yang F, Sun C, Yan X, Duan N, Hua Y, Zeng T, Fu Z, Liang Y, Li W, Huang X, Tang J, Yin Y. tRF-27 competitively Binds to G3BPs and Activates MTORC1 to Enhance HER2 Positive Breast Cancer Trastuzumab Tolerance. Int J Biol Sci. 2024 Jul 15;20(10):3923-3941. [CrossRef]

- Mo D, Tang X, Ma Y, Chen D, Xu W, Jiang N, Zheng J, Yan F. tRNA-derived fragment 3’tRF-AlaAGC modulates cell chemoresistance and M2 macrophage polarization via binding to TRADD in breast cancer. J Transl Med. 2024 Jul 30;22(1):706.

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011 Mar-Apr;61(2):69-90. [CrossRef]

- Martens-Uzunova ES, Jalava SE, Dits NF, van Leenders GJ, Møller S, Trapman J, Bangma CH, Litman T, Visakorpi T, Jenster G. Diagnostic and prognostic signatures from the small non-coding RNA transcriptome in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2012 Feb 23;31(8):978-91. [CrossRef]

- Olvedy M, Scaravilli M, Hoogstrate Y, Visakorpi T, Jenster G, Martens-Uzunova ES. A comprehensive repertoire of tRNA-derived fragments in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016 Apr 26;7(17):24766-77. [CrossRef]

- Magee RG, Telonis AG, Loher P, Londin E, Rigoutsos I. Profiles of miRNA Isoforms and tRNA Fragments in Prostate Cancer. Sci Rep. 2018 Mar 28;8(1):5314. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Lee M, Song G, Lim W. tRNALys-Derived Fragment Alleviates Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis in Prostate Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Jan 4;13(1):55. [CrossRef]

- García-Vílchez R, Añazco-Guenkova AM, Dietmann S, López J, Morón-Calvente V, D’Ambrosi S, Nombela P, Zamacola K, Mendizabal I, García-Longarte S, Zabala-Letona A, Astobiza I, Fernández S, Paniagua A, Miguel-López B, Marchand V, Alonso-López D, Merkel A, García-Tuñón I, Ugalde-Olano A, Loizaga-Iriarte A, Lacasa-Viscasillas I, Unda M, Azkargorta M, Elortza F, Bárcena L, Gonzalez-Lopez M, Aransay AM, Di Domenico T, Sánchez-Martín MA, De Las Rivas J, Guil S, Motorin Y, Helm M, Pandolfi PP, Carracedo A, Blanco S. METTL1 promotes tumorigenesis through tRNA-derived fragment biogenesis in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023 Jul 29;22(1):119. [CrossRef]

- Sui S, Wang Z, Cui X, Jin L, Zhu C. The biological behavior of tRNA-derived fragment tRF-Leu-AAG in pancreatic cancer cells. Bioengineered. 2022 Apr;13(4):10617-10628. [CrossRef]

- Cao W, Dai S, Ruan W, Long T, Zeng Z, Lei S. Pancreatic stellate cell-derived exosomal tRF-19-PNR8YPJZ promotes proliferation and mobility of pancreatic cancer through AXIN2. J Cell Mol Med. 2023 Sep;27(17):2533-2546. [CrossRef]

- Lan S, Liu S, Wang K, Chen W, Zheng D, Zhuang Y, Zhang S. tRNA-derived RNA fragment, tRF-18-8R6546D2, promotes pancreatic adenocarcinoma progression by directly targeting ASCL2. Gene. 2024 Nov 15;927:148739. [CrossRef]

- Cao W, Zeng Z, Lei S. 5’-tRF-19-Q1Q89PJZ Suppresses the Proliferation and Metastasis of Pancreatic Cancer Cells via Regulating Hexokinase 1-Mediated Glycolysis. Biomolecules. 2023 Oct 12;13(10):1513. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Liu X, Jiang S, Zhou X, Yao L, Di Y, Jiang Y, Gu J, Mao Y, Li J, Jin C, Yang P, Fu D. WD repeat-containing protein 1 maintains β-Catenin activity to promote pancreatic cancer aggressiveness. Br J Cancer. 2020 Sep;123(6):1012-1023. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Peng W, Wang R, Bai S, Cao M, Xiong S, Li Y, Yang Y, Liang J, Liu L, Yazdani HO, Zhao Y, Cheng B. Exosome-derived tRNA fragments tRF-GluCTC-0005 promotes pancreatic cancer liver metastasis by activating hepatic stellate cells. Cell Death Dis. 2024 Jan 30;15(1):102. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Jin L, Gao Y, Gao P, Ma L, Zhu B, Yin X, Sui S, Chen S, Jiang Z, Zhu C. Low expression of tRF-Pro-CGG predicts poor prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021 May;35(5):e23742. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Hu J, Liu L, Yan M, Zhang Q, Song X, Lin Y, Zhu D, Wei Y, Fu Z, Hu L, Chen Y, Li X. Gly-tRF enhances LCSC-like properties and promotes HCC cells migration by targeting NDFIP2. Cancer Cell Int. 2021 Sep 18;21(1):502. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Wu C, Wang J, Zhang L, Sun Z, Chen S, Ding Y, Wang W. Transfer RNA-derived fragment 5’tRF-Gly promotes the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by direct targeting of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1. Cancer Sci. 2022 Oct;113(10):3476-3488. [CrossRef]

- Zuo Y, Chen S, Yan L, Hu L, Bowler S, Zitello E, Huang G, Deng Y. Development of a tRNA-derived small RNA diagnostic and prognostic signature in liver cancer. Genes Dis. 2021 Jan 28;9(2):393-400. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Li J, Gong Y, Wu Q, Tan S, Sun D, Xu X, Zuo Y, Zhao Y, Wei YQ, Wei XW, Peng Y. Exosomal tRNA-derived small RNA as a promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Mol Cancer. 2019 Apr 2;18(1):74. [CrossRef]

- Herrera FG, Ronet C, Ochoa de Olza M, Barras D, Crespo I, Andreatta M, Corria-Osorio J, Spill A, Benedetti F, Genolet R, Orcurto A, Imbimbo M, Ghisoni E, Navarro Rodrigo B, Berthold DR, Sarivalasis A, Zaman K, Duran R, Dromain C, Prior J, Schaefer N, Bourhis J, Dimopoulou G, Tsourti Z, Messemaker M, Smith T, Warren SE, Foukas P, Rusakiewicz S, Pittet MJ, Zimmermann S, Sempoux C, Dafni U, Harari A, Kandalaft LE, Carmona SJ, Dangaj Laniti D, Irving M, Coukos G. Low-Dose Radiotherapy Reverses Tumor Immune Desertification and Resistance to Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2022 Jan;12(1):108-133. [CrossRef]

- Weiss T, Schneider H, Silginer M, Steinle A, Pruschy M, Polić B, Weller M, Roth P. NKG2D-Dependent Antitumor Effects of Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy against Glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Feb 15;24(4):882-895.

- Donlon NE, Power R, Hayes C, Reynolds JV, Lysaght J. Radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and the tumour microenvironment: Turning an immunosuppressive milieu into a therapeutic opportunity. Cancer Lett. 2021 Apr 1;502:84-96. [CrossRef]

- Ji J, Ding K, Cheng B, Zhang X, Luo T, Huang B, Yu H, Chen Y, Xu X, Lin H, Zhou J, Wang T, Jin M, Liu A, Yan D, Liu F, Wang C, Chen J, Yan F, Wang L, Zhang J, Yan S, Wang J, Li X, Chen G. Radiotherapy-Induced Astrocyte Senescence Promotes an Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in Glioblastoma to Facilitate Tumor Regrowth. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024 Apr;11(15):e2304609. [CrossRef]

- Gong Y, Zeng F, Zhang F, Liu X, Li Z, Chen W, Liu H, Li X, Cheng Y, Zhang J, Feng Y, Wu T, Zhou W, Zhang T. Radiotherapy plus a self-gelation powder encapsulating tRF5-GlyGCC inhibitor potentiates natural kill cell immunity to prevent hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. J Nanobiotechnology. 2025 Feb 10;23(1):100. [CrossRef]

- Gu X, Ma S, Liang B, Ju S. Serum hsa_tsr016141 as a Kind of tRNA-Derived Fragments Is a Novel Biomarker in Gastric Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021 May 13;11:679366. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Gu X, Qin X, Huang Y, Ju S. Evaluation of serum tRF-23-Q99P9P9NDD as a potential biomarker for the clinical diagnosis of gastric cancer. Mol Med. 2022 Jun 11;28(1):63. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Zhang H, Gu X, Qin S, Zheng M, Shi X, Peng C, Ju S. Elucidating the Role of Serum tRF-31-U5YKFN8DYDZDD as a Novel Diagnostic Biomarker in Gastric Cancer (GC). Front Oncol. 2021 Aug 23;11:723753. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Shi J, Wu Z, Gao P, Zhang W, Qu B, Wang X, Song Y, Wang Z. A 3’-tRNA-derived fragment enhances cell proliferation, migration and invasion in gastric cancer by targeting FBXO47. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2020 Sep 15;690:108467.

- Zhang Y, Gu X, Li Y, Li X, Huang Y, Ju S. Transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-23-Q99P9P9NDD promotes progression of gastric cancer by targeting ACADSB. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2024 May 15;25(5):438-450. [CrossRef]

- Shen Y, Yu X, Ruan Y, Li Z, Xie Y, Yan Z, Guo J. Global profile of tRNA-derived small RNAs in gastric cancer patient plasma and identification of tRF-33-P4R8YP9LON4VDP as a new tumor suppressor. Int J Med Sci. 2021 Feb 4;18(7):1570-1579. [CrossRef]

- Shen Y, Xie Y, Yu X, Zhang S, Wen Q, Ye G, Guo J. Clinical diagnostic values of transfer RNA-derived fragment tRF-19-3L7L73JD and its effects on the growth of gastric cancer cells. J Cancer. 2021 Apr 2;12(11):3230-3238. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Li Z, Yu X, Ruan Y, Shen Y, Shao Y, Zhang X, Ye G, Guo J. The tRNA-derived fragment 5026a inhibits the proliferation of gastric cancer cells by regulating the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021 Jul 22;12(1):418. [CrossRef]

- Xu W, Zhou B, Wang J, Tang L, Hu Q, Wang J, Chen H, Zheng J, Yan F, Chen H. tRNA-Derived Fragment tRF-Glu-TTC-027 Regulates the Progression of Gastric Carcinoma via MAPK Signaling Pathway. Front Oncol. 2021 Aug 23;11:733763. [CrossRef]

- Xu W, Zheng J, Wang X, Zhou B, Chen H, Li G, Yan F. tRF-Val-CAC-016 modulates the transduction of CACNA1d-mediated MAPK signaling pathways to suppress the proliferation of gastric carcinoma. Cell Commun Signal. 2022 May 19;20(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Cui H, Liu Z, Peng L, Liu L, Xie X, Zhang Y, Gao Z, Zhang C, Yu X, Hu Y, Liu J, Shang L, Li L. A novel 5’tRNA-derived fragment tRF-Tyr inhibits tumor progression by targeting hnRNPD in gastric cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 2025 Feb 14;23(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Cui H, Li H, Wu H, Du F, Xie X, Zeng S, Zhang Z, Dong K, Shang L, Jing C, Li L. A novel 3’tRNA-derived fragment tRF-Val promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis by targeting EEF1A1 in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022 May 18;13(5):471. [CrossRef]

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 May-Jun;74(3):229-263.

- Huang B, Yang H, Cheng X, Wang D, Fu S, Shen W, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Xue Z, Li Y, Da Y, Yang Q, Li Z, Liu L, Qiao L, Kong Y, Yao Z, Zhao P, Li M, Zhang R. tRF/miR-1280 Suppresses Stem Cell-like Cells and Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017 Jun 15;77(12):3194-3206. [CrossRef]

- Xu R, Du A, Deng X, Du W, Zhang K, Li J, Lu Y, Wei X, Yang Q, Tang H. tsRNA-GlyGCC promotes colorectal cancer progression and 5-FU resistance by regulating SPIB. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024 Aug 17;43(1):230.

- Primeaux M, Liu X, Gowrikumar S, Fatima I, Fisher KW, Bastola D, Vecchio AJ, Singh AB, Dhawan P. Claudin-1 interacts with EPHA2 to promote cancer stemness and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2023 Nov 28;579:216479. [CrossRef]

- Ye C, Cheng F, Huang L, Wang K, Zhong L, Lu Y, Ouyang M. New plasma diagnostic markers for colorectal cancer: transporter fragments of glutamate tRNA origin. J Cancer. 2024 Jan 12;15(5):1299-1313. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Yang X, Jiang G, Zhang H, Ge L, Chen F, Li J, Liu H, Wang H. 5’-tRF-GlyGCC: a tRNA-derived small RNA as a novel biomarker for colorectal cancer diagnosis. Genome Med. 2021 Feb 9;13(1):20.

- Dang Y, Dai L, Xu J, Zhou W, Xu Y, Ji G. tRNA-derived fragments are promising biomarkers for screening of early colorectal cancer. MedComm (2020). 2023 May 3;4(3):e227. [CrossRef]

- Huang T, Chen C, Du J, Zheng Z, Ye S, Fang S, Liu K. A tRF-5a fragment that regulates radiation resistance of colorectal cancer cells by targeting MKNK1. J Cell Mol Med. 2023 Dec;27(24):4021-4033. [CrossRef]

- Neamtu AA, Maghiar TA, Alaya A, Olah NK, Turcus V, Pelea D, Totolici BD, Neamtu C, Maghiar AM, Mathe E. A Comprehensive View on the Quercetin Impact on Colorectal Cancer. Molecules. 2022 Mar 14;27(6):1873. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Song J, Park S, Ham J, Park W, Park H, An G, Hong T, Kim HS, Song G, Lim W. Targeting Thymidylate Synthase and tRNA-Derived Non-Coding RNAs Improves Therapeutic Sensitivity in Colorectal Cancer. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Oct 31;11(11):2158. [CrossRef]

- Wong CC, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023 Jul;20(7):429-452. [CrossRef]

- Cao KY, Pan Y, Yan TM, Tao P, Xiao Y, Jiang ZH. Antitumor Activities of tRNA-Derived Fragments and tRNA Halves from Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli Strains on Colorectal Cancer and Their Structure-Activity Relationship. mSystems. 2022 Apr 26;7(2):e0016422. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou S, Katsaraki K, Vassiliu P, Danias N, Michalopoulos N, Tzikos G, Sideris DC, Arkadopoulos N. High Intratumoral i-tRF-GlyGCC Expression Predicts Short-Term Relapse and Poor Overall Survival of Colorectal Cancer Patients, Independent of the TNM Stage. Biomedicines. 2023 Jul 8;11(7):1945.

- Tan L, Wu X, Tang Z, Chen H, Cao W, Wen C, Zou G, Zou H. The tsRNAs (tRFdb-3013a/b) serve as novel biomarkers for colon adenocarcinomas. Aging (Albany NY). 2024 Mar 6;16(5):4299-4326. [CrossRef]

- Balatti V, Rizzotto L, Miller C, Palamarchuk A, Fadda P, Pandolfo R, Rassenti LZ, Hertlein E, Ruppert AS, Lozanski A, Lozanski G, Kipps TJ, Byrd JC, Croce CM, Pekarsky Y. TCL1 targeting miR-3676 is codeleted with tumor protein p53 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Feb 17;112(7):2169-74. [CrossRef]

- Veneziano D, Tomasello L, Balatti V, Palamarchuk A, Rassenti LZ, Kipps TJ, Pekarsky Y, Croce CM. Dysregulation of different classes of tRNA fragments in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Nov 26;116(48):24252-24258. [CrossRef]

- Syu YC, Hatterschide J, Budding CR, Tang Y, Musier-Forsyth K. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 uses a specific tRNAPro isodecoder to prime reverse transcription. RNA. 2024 Jul 16;30(8):967-976. [CrossRef]

- Maute RL, Schneider C, Sumazin P, Holmes A, Califano A, Basso K, Dalla-Favera R. tRNA-derived microRNA modulates proliferation and the DNA damage response and is down-regulated in B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jan 22;110(4):1404-9. [CrossRef]

- Guzzi N, Muthukumar S, Cieśla M, Todisco G, Ngoc PCT, Madej M, Munita R, Fazio S, Ekström S, Mortera-Blanco T, Jansson M, Nannya Y, Cazzola M, Ogawa S, Malcovati L, Hellström-Lindberg E, Dimitriou M, Bellodi C. Pseudouridine-modified tRNA fragments repress aberrant protein synthesis and predict leukaemic progression in myelodysplastic syndrome. Nat Cell Biol. 2022 Mar;24(3):299-306. [CrossRef]

- Shao Y, Sun Q, Liu X, Wang P, Wu R, Ma Z. tRF-Leu-CAG promotes cell proliferation and cell cycle in non-small cell lung cancer. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2017 Nov;90(5):730-738.

- Yang W, Gao K, Qian Y, Huang Y, Xiang Q, Chen C, Chen Q, Wang Y, Fang F, He Q, Chen S, Xiong J, Chen Y, Xie N, Zheng D, Zhai R. A novel tRNA-derived fragment AS-tDR-007333 promotes the malignancy of NSCLC via the HSPB1/MED29 and ELK4/MED29 axes. J Hematol Oncol. 2022 May 7;15(1):53.

- Hu F, Niu Y, Mao X, Cui J, Wu X, Simone CB 2nd, Kang HS, Qin W, Jiang L. tsRNA-5001a promotes proliferation of lung adenocarcinoma cells and is associated with postoperative recurrence in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021 Oct;10(10):3957-3972.

- Gu W, Shi J, Liu H, Zhang X, Zhou JJ, Li M, Zhou D, Li R, Lv J, Wen G, Zhu S, Qi T, Li W, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhu H, Zhou C, Knox KS, Wang T, Chen Q, Qian Z, Zhou T. Peripheral blood non-canonical small non-coding RNAs as novel biomarkers in lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020 Nov 12;19(1):159. [CrossRef]

- Zheng B, Song X, Wang L, Zhang Y, Tang Y, Wang S, Li L, Wu Y, Song X, Xie L. Plasma exosomal tRNA-derived fragments as diagnostic biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2022 Oct 31;12:1037523. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Li F, Wang J, He W, Li Y, Li H, Wei Z, Cao Y. tRNA-derived fragment tRF-03357 promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019 Aug 16;12:6371-6383. [CrossRef]

- Panoutsopoulou K, Magkou P, Dreyer T, Dorn J, Obermayr E, Mahner S, van Gorp T, Braicu I, Magdolen V, Zeillinger R, Avgeris M, Scorilas A. tRNA-derived small RNA 3’U-tRFValCAC promotes tumour migration and early progression in ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2023 Feb;180:134-145. [CrossRef]

- Panoutsopoulou K, Dreyer T, Dorn J, Obermayr E, Mahner S, Gorp TV, Braicu I, Zeillinger R, Magdolen V, Avgeris M, Scorilas A. tRNAGlyGCC-Derived Internal Fragment (i-tRF-GlyGCC) in Ovarian Cancer Treatment Outcome and Progression. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Dec 22;14(1):24.

- Wang Y, Xia W, Shen F, Zhou J, Gu Y, Chen Y. tRNA-derived fragment tRF-Glu49 inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion in cervical cancer by targeting FGL1. Oncol Lett. 2022 Aug 9;24(4):334.

- Chen Z, Qi M, Shen B, Luo G, Wu Y, Li J, Lu Z, Zheng Z, Dai Q, Wang H. Transfer RNA demethylase ALKBH3 promotes cancer progression via induction of tRNA-derived small RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 Mar 18;47(5):2533-2545. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou MA, Avgeris M, Levis P, Papasotiriou EC, Kotronopoulos G, Stravodimos K, Scorilas A. tRNA-Derived Fragments (tRFs) in Bladder Cancer: Increased 5’-tRF-LysCTT Results in Disease Early Progression and Patients’ Poor Treatment Outcome. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Dec 6;12(12):3661. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Chen J, Bai M, Liu T, Zhan S, Li J, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Wu L, Zhao Z, Liu S, Chen X, Fang F, Guo H, Sun Y, Yang R. Plasma tsRNA Signatures Serve as a Novel Biomarker for Bladder Cancer. Cancer Sci. 2025 Feb 13. [CrossRef]

- Ying X, Hu W, Huang Y, Lv Y, Ji D, Chen C, Yang B, Zhang C, Liang Y, Zhang H, Liu M, Yuan G, Wu W, Ji W. A Novel tsRNA, m7G-3’ tiRNA LysTTT, Promotes Bladder Cancer Malignancy Via Regulating ANXA2 Phosphorylation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024 Aug;11(31):e2400115.

- Nientiedt M, Deng M, Schmidt D, Perner S, Müller SC, Ellinger J. Identification of aberrant tRNA-halves expression patterns in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2016 Nov 24;6:37158. [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Tolkach Y, Schmidt D, Kristiansen G, Müller SC, Ellinger J. 5’-tRNA Halves are Dysregulated in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Urol. 2018 Feb;199(2):378-383. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Mo Y, Ren D, Liu S, Zeng Z, Xiong W. Transfer RNA-derived small RNAs in tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 2023 Feb 16;22(1):32. [CrossRef]

- Lee YS, Shibata Y, Malhotra A, Dutta A. A novel class of small RNAs: tRNA-derived RNA fragments (tRFs). Genes Dev. 2009 Nov 15;23(22):2639-49. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).