Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Framework

2.2. Animal Models and Treatment Protocols

2.3. Behavioral Testing Paradigms

2.3.1. Ataxia and stereotype test

2.3.2. Open-field tests

2.3.3. Rotarod tests

2.4. Data Acquisition and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

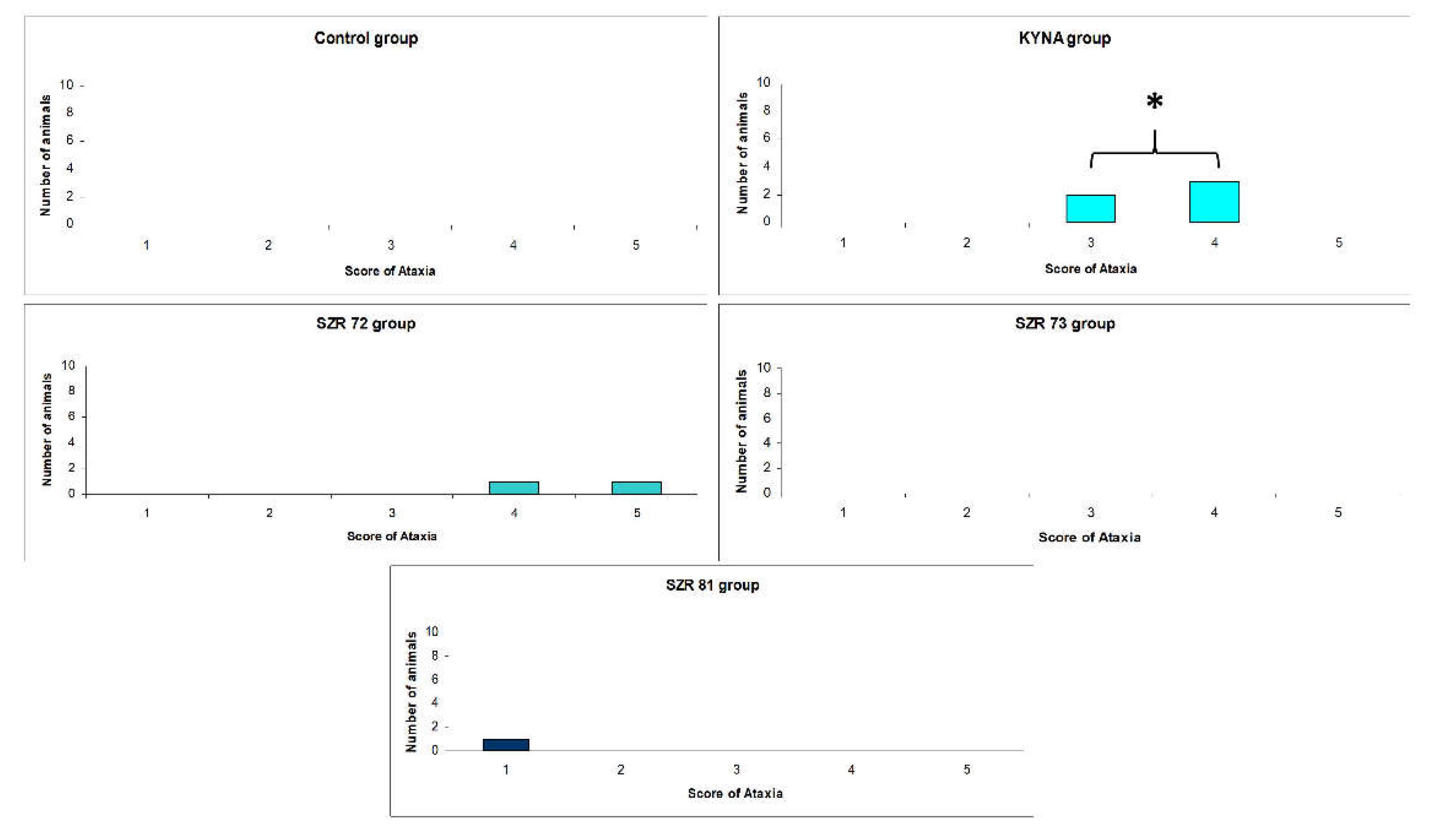

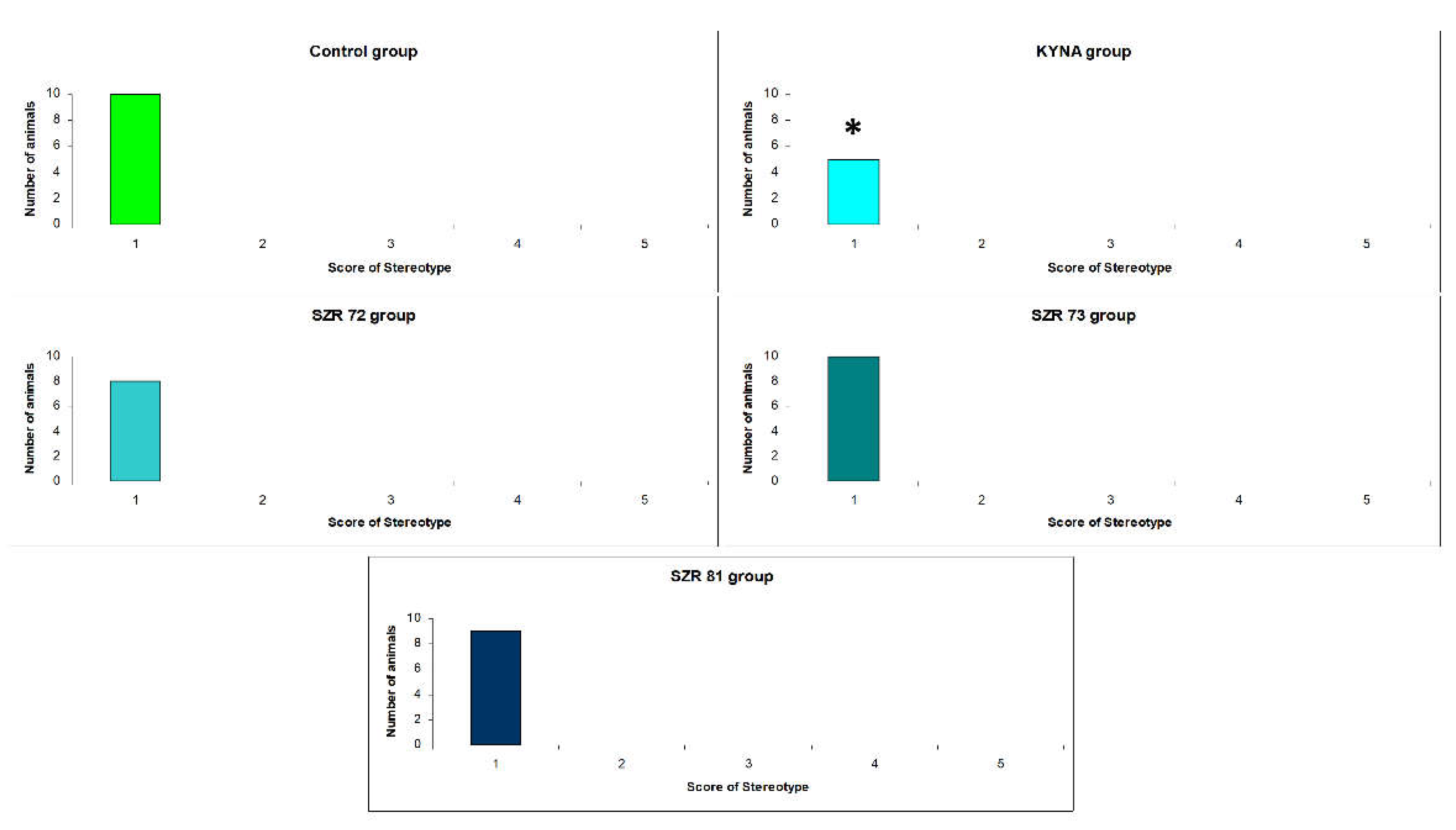

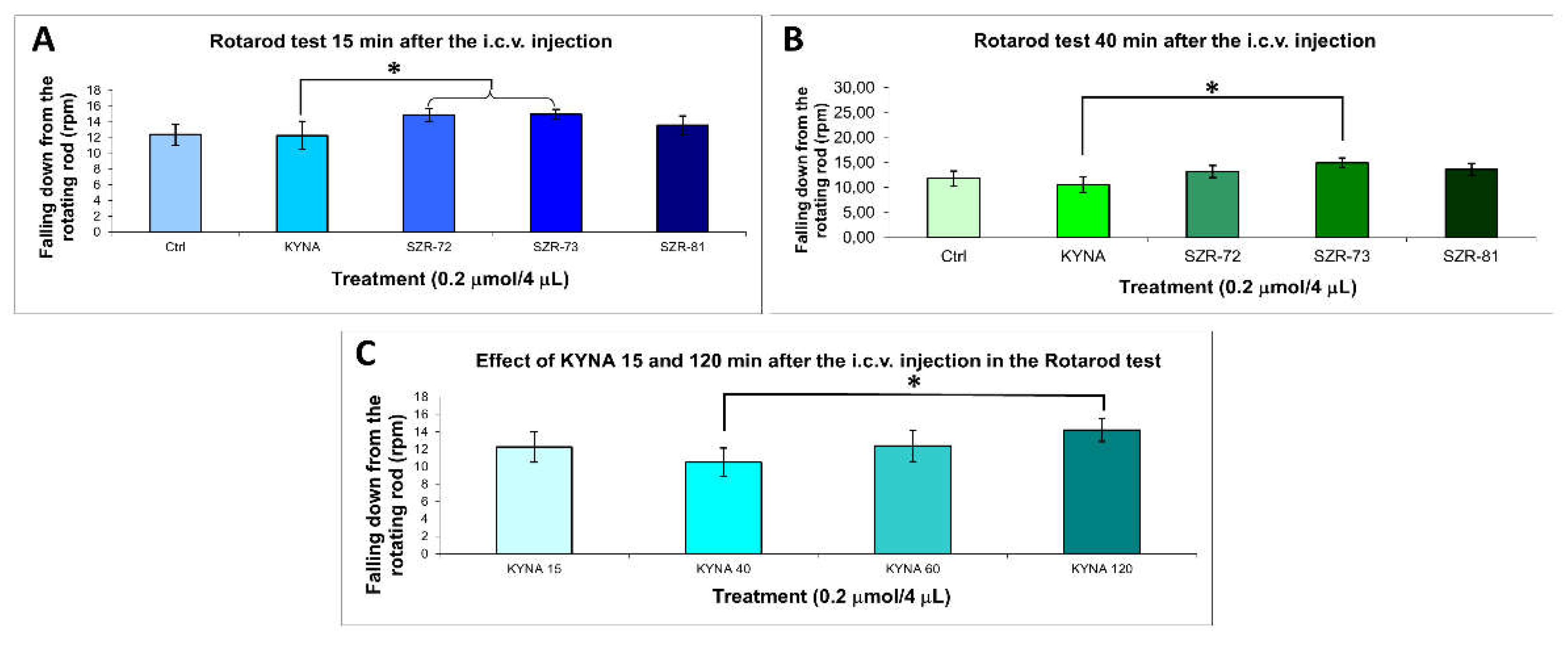

3.1. Acute Motor Effects of KYNA and Analogs

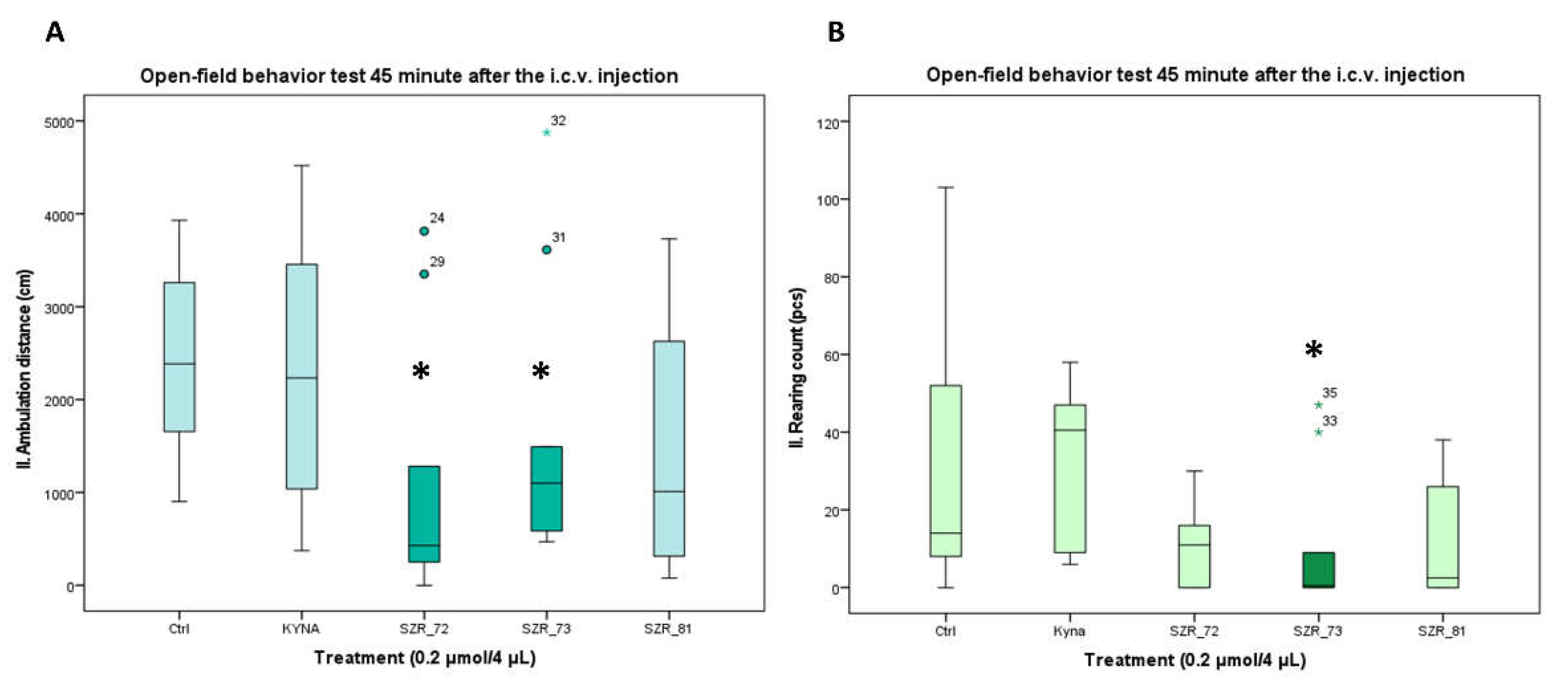

3.2. Open-Field Activity: Delayed Modulation by Analogs

3.3. Summary of Key Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| KYN | kynurenine |

| KYNA | kynurenic acid |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| SCZ | schizophrenia |

References

- Grezenko, H.; Rodoshi, Z.N.; Mimms, C.S.; Ahmed, M.; Sabani, A.; Hlaing, M.S.; Batu, B.J.; Hundesa, M.I.; Ayalew, B.D.; Shehryar, A. From Alzheimer’s Disease to Anxiety, Epilepsy to Schizophrenia: A Comprehensive Dive Into Neuro-Psychiatric Disorders. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holper, L.; Ben-Shachar, D.; Mann, J.J. Multivariate meta-analyses of mitochondrial complex I and IV in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, Alzheimer disease, and Parkinson disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, T.; Lee, H.; Young, A.H.; Aarsland, D.; Thuret, S. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in major depressive disorder and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends in molecular medicine 2020, 26, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borumandnia, N.; Majd, H.A.; Doosti, H.; Olazadeh, K. The trend analysis of neurological disorders as major causes of death and disability according to human development, 1990-2019. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 14348–14354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadeddu, C.; Ianuale, C.; Lindert, J. Public mental health. A systematic review of key issues in public health 2015, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Revolutionizing our understanding of Parkinson’s disease: Dr. Heinz Reichmann’s pioneering research and future research direction. Journal of Neural Transmission 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mubarak, B.; Ahmed Nour, M.; Schumacher-Schuh, A.; Bandres-Ciga, S. Globalizing Research toward Diverse Representation in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Disease. Annals of Neurology 2022, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Li, X.-J.; Yang, W.; He, D. Microglial autophagy in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2023, 14, 1065183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Current psychiatry reports 2019, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, S.F.; Giebel, C.; Khan, M.A.; Hashim, M.J. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: Rising global burden and forecasted trends. F1000Research 2021, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poalelungi, A.; Popescu, B.O. ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE–NEUROLOGICAL OR PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER? Romanian Journal of Neurology 2013, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, I.; Gispert, J.D.; Palumbo, E.; Muñoz-Aguirre, M.; Wucher, V.; D'Argenio, V.; Santpere, G.; Navarro, A.; Guigo, R.; Vilor-Tejedor, N. Brain transcriptomic profiling reveals common alterations across neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2022, 20, 4549–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Better, M.A. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19, 1598–1695. [Google Scholar]

- Frankish, H.; Horton, R. Prevention and management of dementia: a priority for public health. The Lancet 2017, 390, 2614–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheslow, L.; Snook, A.E.; Waldman, S.A. Biomarkers for Managing Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Tanaka, M.; Lamas, C.B.; Quesada, K.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Catharin, V.M.C.S.; de Castro, M.V.M.; Junior, E.B. Vascular impairment, muscle atrophy, and cognitive decline: Critical age-related conditions. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez, F.; Yassa, M.A. Neuroimaging biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular neurodegeneration 2019, 14, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Plotkin, A.S. Unbiased approaches to biomarker discovery in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron 2014, 84, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.E.; Espay, A.J. Disease modification in Parkinson's disease: current approaches, challenges, and future considerations. Movement Disorders 2018, 33, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annus, Á.; Tömösi, F.; Rárosi, F.; Fehér, E.; Janáky, T.; Kecskeméti, G.; Toldi, J.; Klivényi, P.; Sztriha, L.; Vécsei, L. Kynurenic acid and kynurenine aminotransferase are potential biomarkers of early neurological improvement after thrombolytic therapy: A pilot study. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2021, 30, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Török, N.; Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Searching for peripheral biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases: the tryptophan-kynurenine metabolic pathway. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizarro-Galleguillos, B.M.; Kunert, L.; Brüggemann, N.; Prasuhn, J. Neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in parkinson’s disease: connecting neuroimaging with pathophysiology. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitz, J. The kynurenine pathway: a finger in every pie. Molecular psychiatry 2020, 25, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lovelace, M.D.; Varney, B.; Sundaram, G.; Lennon, M.J.; Lim, C.K.; Jacobs, K.; Guillemin, G.J.; Brew, B.J. Recent evidence for an expanded role of the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism in neurological diseases. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, I.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, S.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Zengin, G.; Bumbu, A.G.; Andronie-Cioara, F.L.; Nechifor, A.C. The footprint of kynurenine pathway in neurodegeneration: Janus-faced role in Parkinson’s disorder and therapeutic implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 6737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martín-Hernández, D.; Tendilla-Beltrán, H.; Madrigal, J.L.; García-Bueno, B.; Leza, J.C.; Caso, J.R. Chronic mild stress alters kynurenine pathways changing the glutamate neurotransmission in frontal cortex of rats. Molecular Neurobiology 2019, 56, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, M.; Lajkó, N.; Dulka, K.; Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F.; Mihály, A.; Vécsei, L.; Gulya, K. Kynurenic acid and its analog SZR104 exhibit strong antiinflammatory effects and alter the intracellular distribution and methylation patterns of H3 histones in immunochallenged microglia-enriched cultures of newborn rat brains. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidy, N.; Grant, R. Kynurenine pathway metabolism and neuroinflammatory disease. Neural regeneration research 2017, 12, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Redefining roles: A paradigm shift in tryptophan–kynurenine metabolism for innovative clinical applications. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25, 12767. [Google Scholar]

- Hilmas, C.; Pereira, E.F.; Alkondon, M.; Rassoulpour, A.; Schwarcz, R.; Albuquerque, E.X. The brain metabolite kynurenic acid inhibits α7 nicotinic receptor activity and increases non-α7 nicotinic receptor expression: physiopathological implications. Journal of Neuroscience 2001, 21, 7463–7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secci, M.E.; Mascia, P.; Sagheddu, C.; Beggiato, S.; Melis, M.; Borelli, A.C.; Tomasini, M.C.; Panlilio, L.V.; Schindler, C.W.; Tanda, G. Astrocytic Mechanisms Involving Kynurenic Acid Control Δ 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol-Induced Increases in Glutamate Release in Brain Reward-Processing Areas. Molecular neurobiology 2019, 56, 3563–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, T.; Behan, W.; Jones, P.; Darlington, L.; Smith, R. The role of kynurenines in the production of neuronal death, and the neuroprotective effect of purines. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2001, 3, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroni, F.; Cozzi, A.; Sili, M.; Mannaioni, G. Kynurenic acid: a metabolite with multiple actions and multiple targets in brain and periphery. Journal of neural transmission 2012, 119, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, M.S.; Fricker, A.-C.; Weil, A.; Kew, J.N. Electrophysiological characterisation of the actions of kynurenic acid at ligand-gated ion channels. Neuropharmacology 2009, 57, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkondon, M.; Pereira, E.F.; Albuquerque, E.X. Endogenous activation of nAChRs and NMDA receptors contributes to the excitability of CA1 stratum radiatum interneurons in rat hippocampal slices: effects of kynurenic acid. Biochemical pharmacology 2011, 82, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratek-Gerej, E.; Ziembowicz, A.; Godlewski, J.; Salinska, E. The mechanism of the neuroprotective effect of kynurenic acid in the experimental model of neonatal hypoxia–ischemia: The link to oxidative stress. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajti, J.; Majlath, Z.; Szok, D.; Csati, A.; Toldi, J.; Fulop, F.; Vecsei, L. Novel kynurenic acid analogues in the treatment of migraine and neurodegenerative disorders: preclinical studies and pharmaceutical design. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2015, 21, 2250–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Leme Boaro, B.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Patočka, J.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Tanaka, M.; Laurindo, L.F. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Neuroinflammation Intervention with Medicinal Plants: A Critical and Narrative Review of the Current Literature. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirthgen, E.; Hoeflich, A.; Rebl, A.; Günther, J. Kynurenic acid: the Janus-faced role of an immunomodulatory tryptophan metabolite and its link to pathological conditions. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 8, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindler, J.; Lim, C.K.; Weickert, C.S.; Boerrigter, D.; Galletly, C.; Liu, D.; Jacobs, K.R.; Balzan, R.; Bruggemann, J.; O’Donnell, M. Dysregulation of kynurenine metabolism is related to proinflammatory cytokines, attention, and prefrontal cortex volume in schizophrenia. Molecular psychiatry 2020, 25, 2860–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.W.; Forrest, C.M.; Darlington, L.G. Kynurenine pathway inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for neuroprotection. The FEBS journal 2012, 279, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, G.; Forrest, C.; Stoy, N.; Christofides, J.; Egerton, M.; Stone, T.; Darlington, L. Tryptophan metabolism and oxidative stress in patients with chronic brain injury. European journal of neurology 2006, 13, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; de Oliveira Zanuso, B.; da Silva, R.M.S.; Gallerani Caglioni, L.; Nunes Junqueira de Moraes, V.B.F.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Dogani Rodrigues, V.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Beluce, M.E. AdipoRon’s Impact on Alzheimer’s Disease—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.K.; Fernandez-Gomez, F.J.; Braidy, N.; Estrada, C.; Costa, C.; Costa, S.; Bessede, A.; Fernandez-Villalba, E.; Zinger, A.; Herrero, M.T. Involvement of the kynurenine pathway in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Progress in Neurobiology 2017, 155, 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sorgdrager, F.J.; Vermeiren, Y.; Van Faassen, M.; Van Der Ley, C.; Nollen, E.A.; Kema, I.P.; De Deyn, P.P. Age-and disease-specific changes of the kynurenine pathway in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry 2019, 151, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Razdan, K.; Bansal, Y.; Kuhad, A. Rollercoaster ride of kynurenines: Steering the wheel towards neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 2018, 22, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapiuk, A.; Urbanska, E.M. Kynurenic acid in neurodegenerative disorders—Unique neuroprotection or double-edged sword? CNS neuroscience & therapeutics 2022, 28, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, Á.; Galla, Z.; Spekker, E.; Szűcs, M.; Martos, D.; Takeda, K.; Ozaki, K.; Inoue, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Toldi, J.; et al. Oxidative and Excitatory Neurotoxic Stresses in CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Kynurenine Aminotransferase Knockout Mice: A Novel Model for Despair-Based Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 25706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, D.; Tuka, B.; Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L.; Telegdy, G. Memory enhancement with kynurenic acid and its mechanisms in neurotransmission. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.; e Cordeiro, T.M.; Suchting, R.; de Dios, C.; Leal, V.A.C.; Soares, J.C.; Dantzer, R.; Teixeira, A.L.; Selvaraj, S. Effect of immune activation on the kynurenine pathway and depression symptoms–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2020, 118, 514–523. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, S.; Schwarz, M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Stärkel, P.; de Timary, P. Alterations of kynurenine pathway in alcohol use disorder and abstinence: a link with gut microbiota, peripheral inflammation and psychological symptoms. Translational Psychiatry 2021, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloc, R.; Urbanska, E.M. Memantine and the Kynurenine Pathway in the Brain: Selective Targeting of Kynurenic Acid in the Rat Cerebral Cortex. Cells 2024, 13, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Patte-Mensah, C.; Taleb, O.; Bourguignon, J.-J.; Schmitt, M.; Bihel, F.; Maitre, M.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.G. The neuroprotector kynurenic acid increases neuronal cell survival through neprilysin induction. Neuropharmacology 2013, 70, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

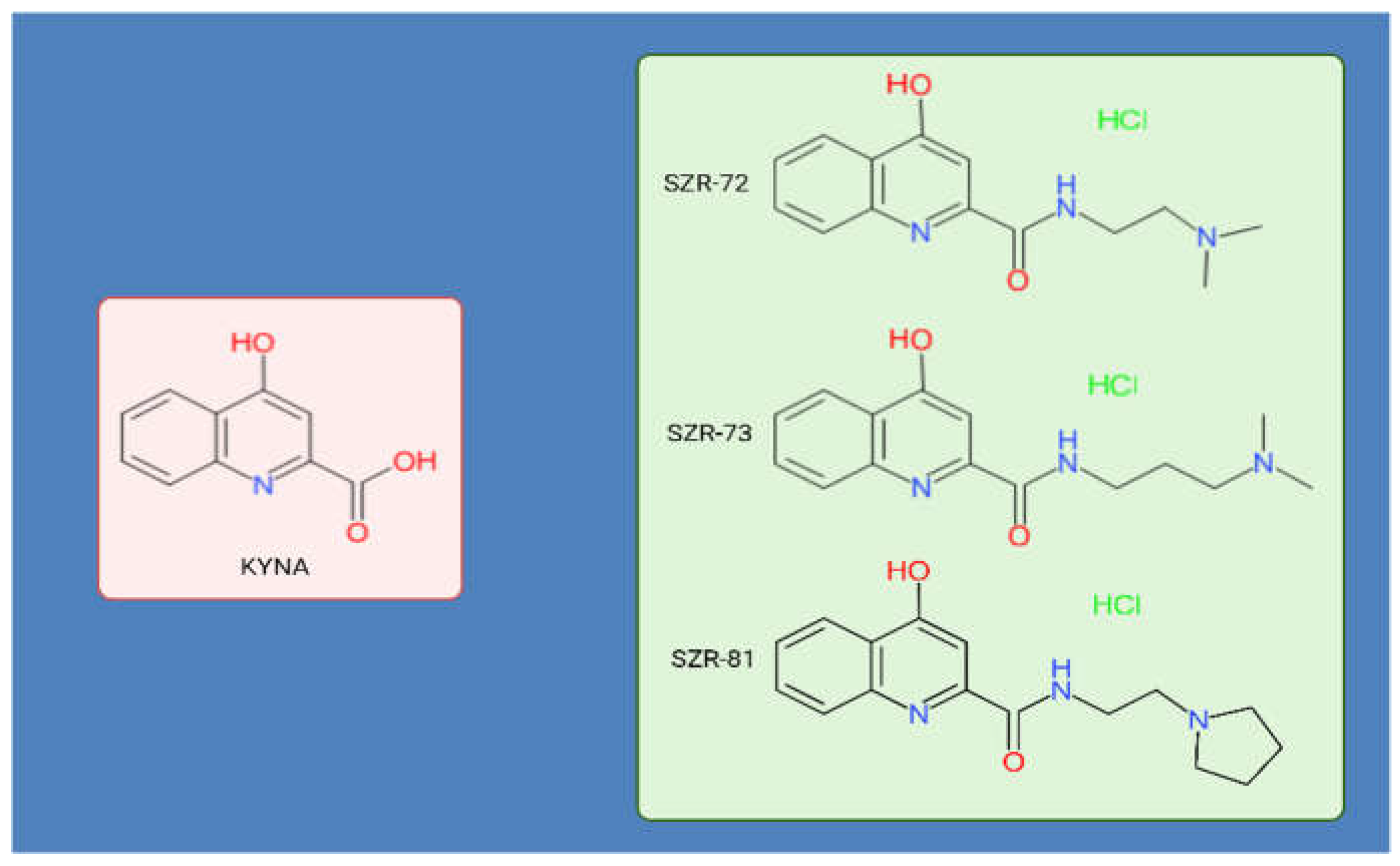

- Lőrinczi, B.; Szatmári, I. KYNA derivatives with modified skeleton; hydroxyquinolines with potential neuroprotective effect. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 11935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, A.C.; Vezzani, A.; French, E.D.; Schwarcz, R. Kynurenic acid blocks neurotoxicity and seizures induced in rats by the related brain metabolite quinolinic acid. Neuroscience letters 1984, 48, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zádori, D.; Nyiri, G.; Szőnyi, A.; Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F.; Toldi, J.; Freund, T.F.; Vécsei, L.; Klivényi, P. Neuroprotective effects of a novel kynurenic acid analogue in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Journal of neural transmission 2011, 118, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phenis, D.; Vunck, S.A.; Valentini, V.; Arias, H.; Schwarcz, R.; Bruno, J.P. Activation of alpha7 nicotinic and NMDA receptors is necessary for performance in a working memory task. Psychopharmacology 2020, 237, 1723–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocivavsek, A.; Elmer, G.I.; Schwarcz, R. Inhibition of kynurenine aminotransferase II attenuates hippocampus-dependent memory deficit in adult rats treated prenatally with kynurenine. Hippocampus 2019, 29, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martos, D.; Lőrinczi, B.; Szatmári, I.; Vécsei, L.; Tanaka, M. The Impact of C-3 Side Chain Modifications on Kynurenic Acid: A Behavioral Analysis of Its Analogs in the Motor Domain. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyihar-Csillik, E.; Mihaly, A.; Krisztin-Peva, B.; Robotka, H.; Szatmari, I.; Fulop, F.; Toldi, J.; Csillik, B.; Vecsei, L. The kynurenate analog SZR-72 prevents the nitroglycerol-induced increase of c-fos immunoreactivity in the rat caudal trigeminal nucleus: comparative studies of the effects of SZR-72 and kynurenic acid. Neurosci Res 2008, 61, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrinczi, B.; Csámpai, A.; Fülöp, F.; Szatmári, I. Synthesis of New C-3 Substituted Kynurenic Acid Derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehér, E.; Szatmári, I.; Dudás, T.; Zalatnai, A.; Farkas, T.; Lőrinczi, B.; Fülöp, F.; Vécsei, L.; Toldi, J. Structural Evaluation and Electrophysiological Effects of Some Kynurenic Acid Analogs. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lőrinczi, B.; Csámpai, A.; Fülöp, F.; Szatmári, I. Synthetic- and DFT modelling studies on regioselective modified Mannich reactions of hydroxy-KYNA derivatives. RSC Adv 2020, 11, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapin, I.P. Convulsant action of intracerebroventricularly administered l-kynurenine sulphate, quinolinic acid and other derivatives of succinic acid, and effects of amino acids: structure-activity relationships. Neuropharmacology 1982, 21, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapin, I.P. Stimulant and convulsive effects of kynurenines injected into brain ventricles in mice. J Neural Transm 1978, 42, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vécsei, L.; Beal, M.F. Intracerebroventricular injection of kynurenic acid, but not kynurenine, induces ataxia and stereotyped behavior in rats. Brain Res Bull 1990, 25, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapin, I.P.; Prakhie, I.B.; Kiseleva, I.P. Excitatory effects of kynurenine and its metabolites, amino acids and convulsants administered into brain ventricles: differences between rats and mice. J Neural Transm 1982, 54, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Jung, J.S.; Moon, Y.S.; Song, D.K. Central or peripheral norepinephrine depletion enhances MK-801-induced plasma corticosterone level in mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2009, 33, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, I.A.; Hansen, A.K.; Sandøe, P. Ethics and refinement in animal research. Science 2007, 317, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinn, R.; Fergusson, D.A.; Stewart, D.J.; Kristof, A.S.; Barron, C.C.; Thebaud, B.; McIntyre, L.; Stacey, D.; Liepmann, M.; Dodelet-Devillers, A.; et al. Surrogate Humane Endpoints in Small Animal Models of Acute Lung Injury: A Modified Delphi Consensus Study of Researchers and Laboratory Animal Veterinarians. Crit Care Med 2021, 49, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingarelli, B.; Coopersmith, C.M.; Drechsler, S.; Efron, P.; Marshall, J.C.; Moldawer, L.; Wiersinga, W.J.; Xiao, X.; Osuchowski, M.F.; Thiemermann, C. Part I: Minimum Quality Threshold in Preclinical Sepsis Studies (MQTiPSS) for Study Design and Humane Modeling Endpoints. Shock 2019, 51, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemzek, J.A.; Xiao, H.Y.; Minard, A.E.; Bolgos, G.L.; Remick, D.G. Humane endpoints in shock research. Shock 2004, 21, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfert, E.D.; Godson, D.L. Humane endpoints for infectious disease animal models. Ilar j 2000, 41, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Banneke, S.; Lips, J.; Kuffner, M.T.C.; Hoffmann, C.J.; Dirnagl, U.; Endres, M.; Harms, C.; Emmrich, J.V. Refining humane endpoints in mouse models of disease by systematic review and machine learning-based endpoint definition. Altex 2019, 36, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, R.D.; Fessler, R.G.; Meltzer, H.Y. Behavioral rating scales for assessing phencyclidine-induced locomotor activity, stereotyped behavior and ataxia in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 1979, 59, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, P.C. D-serine antagonized phencyclidine- and MK-801-induced stereotyped behavior and ataxia. Neuropharmacology 1990, 29, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, S.; Adams, P.M. Acute and chronic phencyclidine effects on locomotor activity, stereotypy and ataxia in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 1981, 73, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanii, Y.; Nishikawa, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Takahashi, K. Stereoselective antagonism by enantiomers of alanine and serine of phencyclidine-induced hyperactivity, stereotypy and ataxia in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1994, 269, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraeuter, A.K.; Guest, P.C.; Sarnyai, Z. The Open Field Test for Measuring Locomotor Activity and Anxiety-Like Behavior. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1916, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, J.A.; McCoy, E.S.; Lee, D.F.; Zylka, M.J. The open field assay is influenced by room temperature and by drugs that affect core body temperature. F1000Res 2023, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibenhener, M.L.; Wooten, M.C. Use of the Open Field Maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice. J Vis Exp 2015, e52434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, J.H.; Sloan, D.C.; Hauger, J.A.; Muntean, B.S. Customizable Open-Source Rotating Rod (Rotarod) Enables Robust Low-Cost Assessment of Motor Performance in Mice. eNeuro 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiotsuki, H.; Yoshimi, K.; Shimo, Y.; Funayama, M.; Takamatsu, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Takahashi, R.; Kitazawa, S.; Hattori, N. A rotarod test for evaluation of motor skill learning. J Neurosci Methods 2010, 189, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, R.M. Measuring motor coordination in mice. J Vis Exp 2013, e2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.J.; Roberts, D.J. The quantiative measurement of motor inco-ordination in naive mice using an acelerating rotarod. J Pharm Pharmacol 1968, 20, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmon, K.J.; Vyas, M.; Woodley, E.; Thompson, P.; Walia, J.S. Battery of Behavioral Tests Assessing General Locomotion, Muscular Strength, and Coordination in Mice. J Vis Exp 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustay, N.R.; Wahlsten, D.; Crabbe, J.C. Influence of task parameters on rotarod performance and sensitivity to ethanol in mice. Behav Brain Res 2003, 141, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J.; Niibori, Y.; P, W.F.; J, P.L. Rotarod training in mice is associated with changes in brain structure observable with multimodal MRI. Neuroimage 2015, 107, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spink, A.J.; Tegelenbosch, R.A.; Buma, M.O.; Noldus, L.P. The EthoVision video tracking system--a tool for behavioral phenotyping of transgenic mice. Physiol Behav 2001, 73, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman, O.; von Ziegler, L.; Schläppi, C.; Akyol, F.; Privitera, M.; Slominski, D.; Grimm, C.; Thieren, L.; Zerbi, V.; Grewe, B.; et al. Deep learning-based behavioral analysis reaches human accuracy and is capable of outperforming commercial solutions. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 1942–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noldus, L.P.; Spink, A.J.; Tegelenbosch, R.A. EthoVision: a versatile video tracking system for automation of behavioral experiments. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2001, 33, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieco, F.; Bernstein, B.J.; Biemans, B.; Bikovski, L.; Burnett, C.J.; Cushman, J.D.; van Dam, E.A.; Fry, S.A.; Richmond-Hacham, B.; Homberg, J.R.; et al. Measuring Behavior in the Home Cage: Study Design, Applications, Challenges, and Perspectives. Front Behav Neurosci 2021, 15, 735387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.M.; Grieco, F.; Tegelenbosch, R.A.; Kyzar, E.J.; Nguyen, M.; Kaluyeva, A.; Song, C.; Noldus, L.P.; Kalueff, A.V. A novel 3D method of locomotor analysis in adult zebrafish: Implications for automated detection of CNS drug-evoked phenotypes. J Neurosci Methods 2015, 255, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recommendations for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development. Stroke 1999, 30, 2752–2758. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, V.C.; Kimmelman, J.; Fergusson, D.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hackam, D.G. Threats to validity in the design and conduct of preclinical efficacy studies: a systematic review of guidelines for in vivo animal experiments. PLoS Med 2013, 10, e1001489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Cheloha, R.W.; Watanabe, T.; Gardella, T.J.; Gellman, S.H. Receptor selectivity from minimal backbone modification of a polypeptide agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 12383–12388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrhein, F.; Lippe, J.; Mazik, M. Carbohydrate receptors combining both a macrocyclic building block and flexible side arms as recognition units: binding properties of compounds with CH(2)OH groups as side arms. Org Biomol Chem 2016, 14, 10648–10659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournie-Zaluski, M.C.; Gacel, G.; Maigret, B.; Premilat, S.; Roques, B.P. Structural requirements for specific recognition of mu or delta opiate receptors. Mol Pharmacol 1981, 20, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiss, C.J.; Allore, H.G.; Beck, A.P. Established patterns of animal study design undermine translation of disease-modifying therapies for Parkinson's disease. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M.; Fadda, P.; Klephan, K.J.; Hull, C.; Teismann, P.; Platt, B.; Riedel, G. Neurochemical, histological, and behavioral profiling of the acute, sub-acute, and chronic MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem 2023, 164, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, F.L.; Hebron, M.L.; Wilmarth, B.; Torres-Yaghi, Y.; Lawler, A.; Mundel, E.E.; Yusuf, N.; Starr, N.J.; Arellano, J.; Howard, H.H.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a single dose Nilotinib in individuals with Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2019, 7, e00470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, T.W. Does kynurenic acid act on nicotinic receptors? An assessment of the evidence. J Neurochem 2020, 152, 627–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeson, P.D.; Baker, R.; Carling, R.W.; Curtis, N.R.; Moore, K.W.; Williams, B.J.; Foster, A.C.; Donald, A.E.; Kemp, J.A.; Marshall, G.R. Kynurenic acid derivatives. Structure-activity relationships for excitatory amino acid antagonism and identification of potent and selective antagonists at the glycine site on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J Med Chem 1991, 34, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.D.; Song, Z. Kynurenic Acid Acts as a Signaling Molecule Regulating Energy Expenditure and Is Closely Associated With Metabolic Diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 847611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.C.; Kemp, J.A.; Leeson, P.D.; Grimwood, S.; Donald, A.E.; Marshall, G.R.; Priestley, T.; Smith, J.D.; Carling, R.W. Kynurenic acid analogues with improved affinity and selectivity for the glycine site on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor from rat brain. Mol Pharmacol 1992, 41, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.W. Development and therapeutic potential of kynurenic acid and kynurenine derivatives for neuroprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2000, 21, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Feng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ban, S.; Song, H. Diversity-Oriented Biosynthesis Yields l-Kynurenine Derivative-Based Neurological Drug Candidate Collection. ACS Synth Biol 2023, 12, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, K.; Lőrinczi, B.; Fazakas, C.; Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F.; Kmetykó, N.; Berkecz, R.; Ilisz, I.; Krizbai, I.A.; Wilhelm, I.; et al. SZR-104, a Novel Kynurenic Acid Analogue with High Permeability through the Blood-Brain Barrier. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deora, G.S.; Kantham, S.; Chan, S.; Dighe, S.N.; Veliyath, S.K.; McColl, G.; Parat, M.O.; McGeary, R.P.; Ross, B.P. Multifunctional Analogs of Kynurenic Acid for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease: Synthesis, Pharmacology, and Molecular Modeling Studies. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017, 8, 2667–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mándi, Y.; Endrész, V.; Mosolygó, T.; Burián, K.; Lantos, I.; Fülöp, F.; Szatmári, I.; Lőrinczi, B.; Balog, A.; Vécsei, L. The Opposite Effects of Kynurenic Acid and Different Kynurenic Acid Analogs on Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) Production and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Stimulated Gene-6 (TSG-6) Expression. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, V.; Remzső, G.; Körmöczi, T.; Berkecz, R.; Tóth-Szűki, V.; Pénzes, A.; Vécsei, L.; Domoki, F. The Kynurenic Acid Analog SZR72 Enhances Neuronal Activity after Asphyxia but Is Not Neuroprotective in a Translational Model of Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrallah, H.A.; Earley, W.; Cutler, A.J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, K.; Laszlovszky, I.; Németh, G.; Durgam, S. The safety and tolerability of cariprazine in long-term treatment of schizophrenia: a post hoc pooled analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzenschlager, R.; Poewe, W.; Rascol, O.; Trenkwalder, C.; Deuschl, G.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Henriksen, T.; van Laar, T.; Lockhart, D.; Staines, H.; et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of apomorphine infusion in Parkinson's disease patients with persistent motor fluctuations: Results of the open-label phase of the TOLEDO study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2021, 83, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauriello, J.; Claxton, A.; Du, Y.; Weiden, P.J. Beyond 52-Week Long-Term Safety: Long-Term Outcomes of Aripiprazole Lauroxil for Patients With Schizophrenia Continuing in an Extension Study. J Clin Psychiatry 2020, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Han, Y.; Wei, Z.; Li, J. Binding Affinity and Mechanisms of Potential Antidepressants Targeting Human NMDA Receptors. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacilieri, M.; Varano, F.; Deflorian, F.; Marini, M.; Catarzi, D.; Colotta, V.; Filacchioni, G.; Galli, A.; Costagli, C.; Kaseda, C.; et al. Tandem 3D-QSARs approach as a valuable tool to predict binding affinity data: design of new Gly/NMDA receptor antagonists as a key study. J Chem Inf Model 2007, 47, 1913–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.K.; Liu, Y.L.; Chen, Y.I.; Huang, P.J.; Tsou, P.H.; Chen, C.T.; Lee, H.H.; Wang, Y.N.; Hsu, J.L.; Lee, J.F.; et al. Digital Receptor Occupancy Assay in Quantifying On- and Off-Target Binding Affinities of Therapeutic Antibodies. ACS Sens 2020, 5, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, V.S.; Gonçalves, A.M.; Nascimento-Júnior, N.M. Pharmacophore Mapping Combined with dbCICA Reveal New Structural Features for the Development of Novel Ligands Targeting α4β2 and α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.T.; Chen, S.; Schetz, J.A. An unambiguous assay for the cloned human sigma1 receptor reveals high affinity interactions with dopamine D4 receptor selective compounds and a distinct structure-affinity relationship for butyrophenones. Eur J Pharmacol 2008, 578, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgese, M.G.; Bove, M.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Schiavone, S.; Colia, A.L.; Dimonte, S.; Mhillaj, E.; Sikora, V.; Tucci, P.; Ghelardini, C.; et al. Precision Medicine in Alzheimer's Disease: Investigating Comorbid Common Biological Substrates in the Rat Model of Amyloid Beta-Induced Toxicity. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 799561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Li, Y.; Ye, G.; Zhou, L.; Bian, X.; Liu, J. Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model for Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson's Disease With REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 703158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Han, J.; Zhao, L.; Wu, C.; Wu, P.; Huang, Z.; Hao, X.; Ji, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhu, M. Experimental Models of Cognitive Impairment for Use in Parkinson's Disease Research: The Distance Between Reality and Ideal. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 745438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, T.N.; Greene, J.G.; Miller, G.W. Behavioral phenotyping of mouse models of Parkinson's disease. Behav Brain Res 2010, 211, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaira, T.; Subramani, C.; Barman, T.K. ADME, Pharmacokinetic Scaling, Pharmacodynamic and Prediction of Human Dose and Regimen of Novel Antiviral Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, K.M. Novel Technologies Enable Mechanistic Understanding and Modeling of Drug Exposure and Response. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020, 107, 1045–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumaier, F.; Zlatopolskiy, B.D.; Neumaier, B. Drug Penetration into the Central Nervous System: Pharmacokinetic Concepts and In Vitro Model Systems. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obach, R.S.; Baxter, J.G.; Liston, T.E.; Silber, B.M.; Jones, B.C.; MacIntyre, F.; Rance, D.J.; Wastall, P. The prediction of human pharmacokinetic parameters from preclinical and in vitro metabolism data. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997, 283, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Beyond the boundaries: Transitioning from categorical to dimensional paradigms in mental health diagnostics. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2024, 33, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, Y.C.; Mendes, N.M.; Pereira de Lima, E.; Chehadi, A.C.; Lamas, C.B.; Haber, J.F.; dos Santos Bueno, M.; Araújo, A.C.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Detregiachi, C.R.P. Curcumin: A golden approach to healthy aging: A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Pirmohamed, M.; Comabella, M. Pharmacogenomics in neurology: current state and future steps. Ann Neurol 2011, 70, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radonjić, N.V.; Hess, J.L.; Rovira, P.; Andreassen, O.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Ching, C.R.K.; Franke, B.; Hoogman, M.; Jahanshad, N.; McDonald, C.; et al. Structural brain imaging studies offer clues about the effects of the shared genetic etiology among neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 2101–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Glessner, J.T.; Li, J.; Qi, X.; Hou, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, X.; March, M.E.; Yang, L.; Mentch, F.D.; et al. Integrative analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies novel loci associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrode, N.; Ho, S.M.; Yamamuro, K.; Dobbyn, A.; Huckins, L.; Matos, M.R.; Cheng, E.; Deans, P.J.M.; Flaherty, E.; Barretto, N.; et al. Synergistic effects of common schizophrenia risk variants. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Luo, J.; Chen, X.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, T. Brain-targeted delivery shuttled by black phosphorus nanostructure to treat Parkinson's disease. Biomaterials 2020, 260, 120339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Li, M.; Gao, Y.; Yin, L.; Guan, Y. Brain-targeted gene delivery of ZnO quantum dots nanoplatform for the treatment of Parkinson disease. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 429, 132210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sela, M.; Poley, M.; Mora-Raimundo, P.; Kagan, S.; Avital, A.; Kaduri, M.; Chen, G.; Adir, O.; Rozencweig, A.; Weiss, Y. Brain-targeted liposomes loaded with monoclonal antibodies reduce alpha-synuclein aggregation and improve behavioral symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Advanced Materials 2023, 35, 2304654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, T.M.; Tarini, D.; Dheen, S.T.; Bay, B.H.; Srinivasan, D.K. Nanoparticle-based technology approaches to the management of neurological disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hammarlund-Udenaes, M. Perspectives on nanodelivery to the brain: Prerequisites for successful brain treatment. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2020, 17, 4029–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A.M.; de Groot, M.W.; Wijnolts, F.M.; Kasteel, E.E.; Hondebrink, L.; Westerink, R. Is the time right for in vitro neurotoxicity testing using human iPSC-derived neurons? ALTEX-Alternatives to animal experimentation 2016, 33, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirenko, O.; Parham, F.; Dea, S.; Sodhi, N.; Biesmans, S.; Mora-Castilla, S.; Ryan, K.; Behl, M.; Chandy, G.; Crittenden, C. Functional and mechanistic neurotoxicity profiling using human iPSC-derived neural 3D cultures. Toxicological Sciences 2019, 167, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A.M.; Wijnolts, F.M.; de Groot, A.; Westerink, R.H. Human iPSC-derived neuronal models for in vitro neurotoxicity assessment. Neurotoxicology 2018, 67, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, G.; Phillips, N.; Carromeu, C.; Guicherit, O.; White, A.; Johnson, M.; Zanella, F.; Anson, B.; Lovenberg, T.; Bonaventure, P. Screening for modulators of neural network activity in 3D human iPSC-derived cortical spheroids. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0240991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paola, M.; Pischiutta, F.; Comolli, D.; Mariani, A.; Kelk, J.; Lisi, I.; Cerovic, M.; Fumagalli, S.; Forloni, G.; Zanier, E.R. Neural cortical organoids from self-assembling human iPSC as a model to investigate neurotoxicity in brain ischemia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2023, 43, 680–693. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M. From Serendipity to Precision: Integrating AI, Multi-Omics, and Human-Specific Models for Personalized Neuropsychiatric Care. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behavior | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Ataxia | Awkward and jerky movements | 1 |

| Stumbling or awkward posture | 2 | |

| Falling | 3 | |

| Inability to move beyond a small area or support weight on the stomach or haunches | 4 | |

| Inability to move, except for twitching movements | 5 | |

| Stereotype | Sniffing, grooming, and rearing, reciprocal forepaw treading or undirected head movement | 1 |

| Backward walking, head weaving, circling behavior | 2 | |

| Continuous head weaving, circling, or backward walking | 3 | |

| Dyskinetic extensions or flexion of the limbs | 4 | |

| Head, and neck or weaving greater than four | 5 | |

| Compounds | Ataxia score (# of animals) |

Stereotype score (# of animals) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 45 min | 15 min | 45 min | |

| Control | 0(10) | 0(10) | 1(10) | 1(10) |

| KYNA | 3(2), 4(3)1 | 0(10) | 1(5)1 | 1(10) |

| SZR-72 | 4(1), 5(1) | 0(10) | 1(8) | 1(10) |

| SZR-73 | 0(10) | 0(10) | 1(10) | 1(10) |

| SZR-81 | 1(1) | 0(10) | 1(9) | 1(10) |

| Compounds | Ambulation distance | Rearing count | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 45 min | 15 min | 45 min | |

| Control | 3372.3 ± 441.925 (10) | 2423.3 ± 328.405 (10) | 38.6 ± 11.197 (10) | 28.4 ± 10.341 (10) |

| KYNA | 3085.6 ± 505.334 (10) | 2278.6 ± 439.742 (10) | 35.0 ± 9.084 (10) | 32.8 ± 6.622 (10) |

| SZR-72 | 1699.7 ± 612.203 (10) | 1081.7 ± 435.542 (10) 1,2 | 18.7 ± 6.762 (10) | 10.2 ± 3.133 (10) |

| SZR-73 | 2224.9 ± 544.970 (10) | 1600.6 ± 462.407 (10) 1 | 11.5 ± 5.807 (10) | 9.8 ± 5.707 (10) 1,2 |

| SZR-81 | 1794.0 ± 499.207 (10) | 1397.7 ± 389.917 (10) | 23.5 ± 9.653 (10) | 12.1 ± 4.836 (10) |

| Compounds | Latency to fall (RPM) | |

|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 40 min | |

| Control | 70.143 ± 15.322 (7) | 40,777 ± 15.412 (7) |

| KYNA | 58.590 ± 20.559 (10) | 50.444 ± 15.952 (10) |

| SZR-72 | 76.840 ± 11.729 (10)1 | 51.448 ± 16.269 (10) |

| SZR-73 | 77.600 ± 9.279 (10)1 | 45.284 ± 14.320 (10)1 |

| SZR-81 | 64.420 ± 13.238 (10) | 51.581 ± 16.311 (10) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).