Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 91G10

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

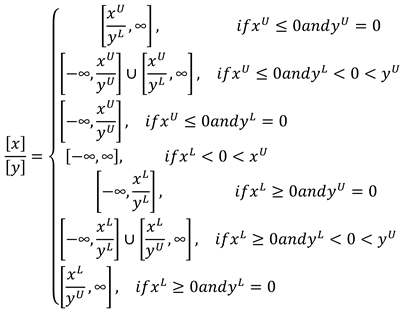

2.1. Interval Analysis Background

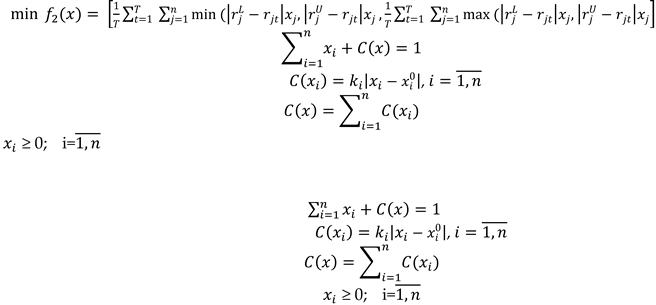

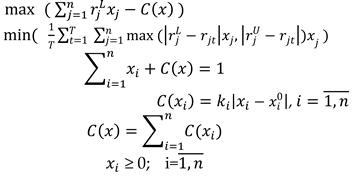

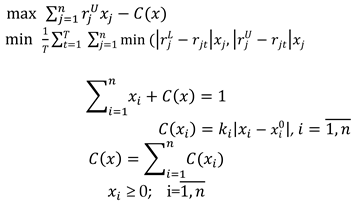

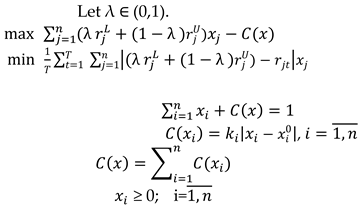

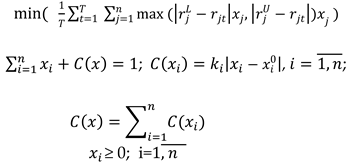

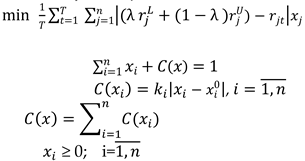

2.2. Model Formulation

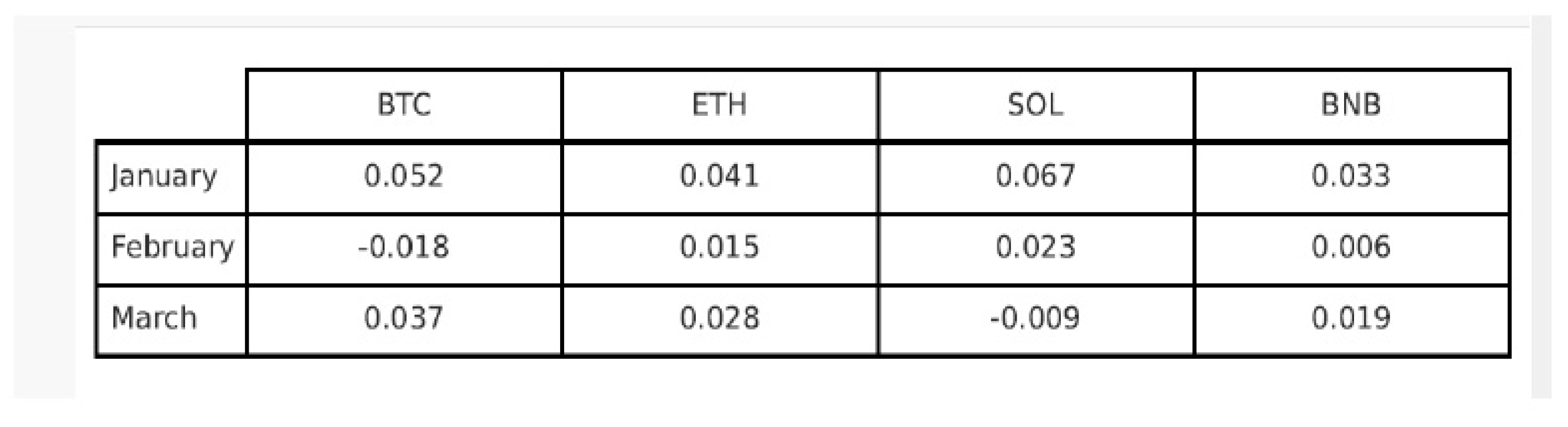

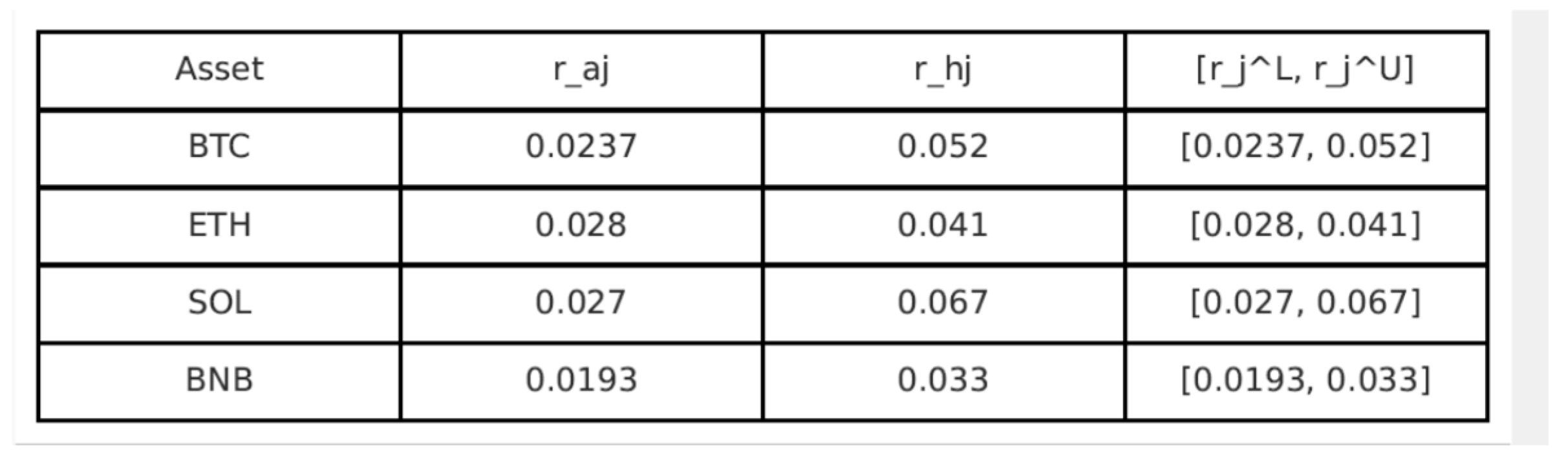

2.3. Case Studies

3. Results and Discussions

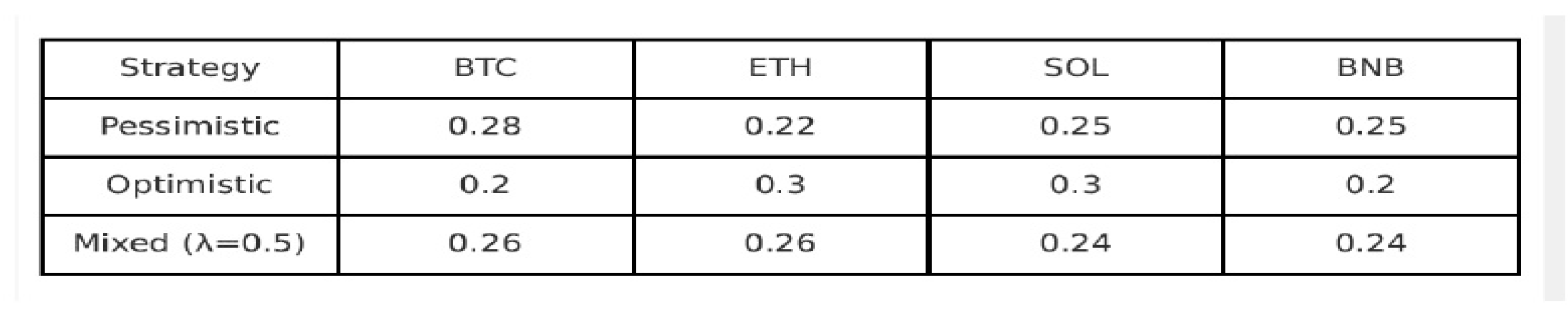

3.1. Portfolio Allocations

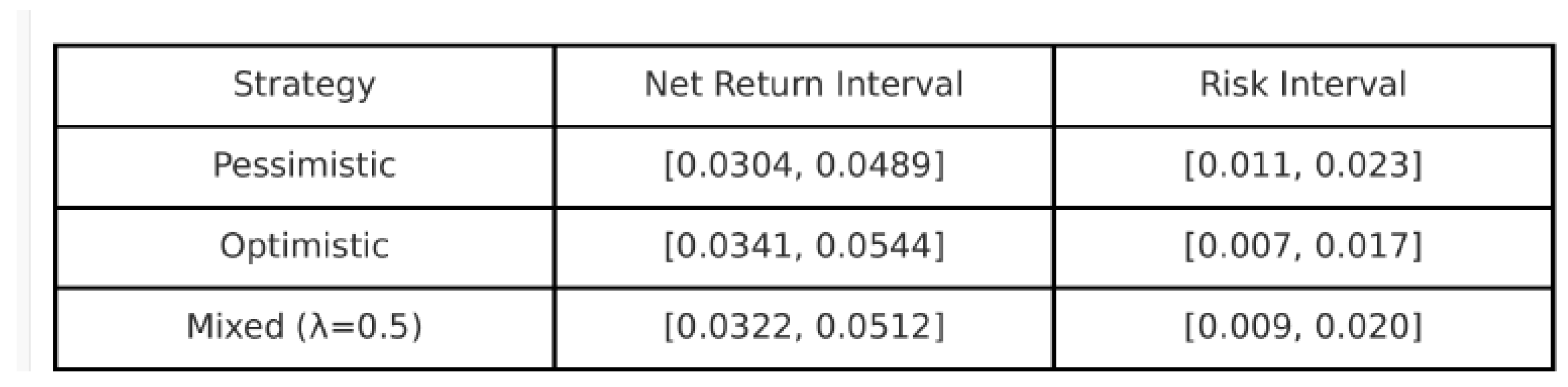

3.2. Net Return and Risk Intervals

3.3. Strategic Insights

4. Conclusions and Future Work

References

- Alefeld, G.; Herzberger, J. (1983). Introduction to Interval Computations. Academic Press, New York. https://www.sciencedirect. 0024. [Google Scholar]

- Allahdadi, M.; Nehi, H.M. Fuzzy linear programming with interval linear programming approach. Advanced Modelling and Optimization 2011, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Artzner, P.; Delbaen, F.; Eber, J.M.; Heath, D. Coherent measures of risk. Mathematical Finance 1999, 9, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.K.; Biswal, M.P.; Chakravartay, D. Multiobjective Two-Stage Stochastic Programming Problems with Interval Discrete Random Variables. Advances in Operations Research, 2012, 279181. https://www.researchgate. 2583. [Google Scholar]

- Birge, J.R.; Louveaux, F. (1997). Introduction to Stochastic Programming. Springer, New York.

- Chinneck, J.W.; Ramadan, K. Linear programming with interval coefficients. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2000, 51, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, S.Y. An interval semi-absolute deviation model for portfolio selection. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2006, 4223, 766–775. [Google Scholar]

- Guu, S.-M.; Mehlawat, M.; Kumar, S. A Multiobjective Optimization Framework for Optimal Selection of Supplier Portfolio. Optimization, 2014, 63, 1491–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Lin, M. (1987). Group Decision Making under Multiple Criteria: Methods and Applications. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. (1981). Multiple Attribute Decision Making. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York.

- Ishibuchi, H.; Tanaka, H. Multiobjective programming in optimization of the interval objective function. European Journal of Operational Research 1990, 48, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, Y. (2011). Optimization method interval portfolio selection based on satisfaction index of interval inequality relation. http://arxiv/papers/1207/1207.1932.

- Kall, P.; Wallace, S.W. (1994). Stochastic Programming. John Wiley and Sons.

- Kambo, N.S. (1997). Mathematical Programming Techniques. Affiliated East-West Press, New York.

- Markowitz, H. Portfolio selection. Journal of Finance 1952, 7, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.E. Interval Analysis. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1966.

- Moore, R.E. Methods and Application of Interval Analysis. SIAM, Philadelphia, 1979.

- Nobibon, F.T.; Guo, R. Foundation and formulation of stochastic interval programming. PGD Thesis, African Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cape Town, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ogryczak, W. Multiple criteria optimization and decisions under risk. Control and Cybernetics 2002, 31(4), 975–1003. https://www.researchgate. 2690. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszczynski, A.; Shapiro, A. (2003). Stochastic Programming. Elsevier, Vol. 10.

- Sayin, S.; Kouvelis, P. The multiobjective discrete optimization problem: A weighted min-max two-stage optimization approach and a bicriteria algorithm. Management Science 2005, 51, 1572–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şerban, F.; Ştefănescu, M.V.; Dedu, S. The Relationship Profitability–Risk for an Optimal Portfolio Building with Two Risky Assets and a Risk-Free Asset. Int. J. Med. Eng. Inform. 2011, 5, 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Sheraz, M.; Dedu, S.; Preda, V. Volatility dynamics of non-linear volatile time series and analysis of information flow: Evidence from cryptocurrency data. Entropy 2022, 24, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, A.; Dentcheva, D.; Ruszczynski, A. Lectures on Stochastic Programming: Modeling and Theory. MOS-SIAM Series on Optimization 2009, 9, 1–436. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, A.; Dedu, S. Quantitative techniques for financial risk assessment: a comparative approach using different risk measures and estimation methods. Procedia Economics and Finance 2014, 8, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).