1. Introduction

The development of prime editing over the past few years has yielded a form of genomic editing with increased precision [

1] and avoids some of the issues that may arise from the double-stranded breaks inherent to the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing [

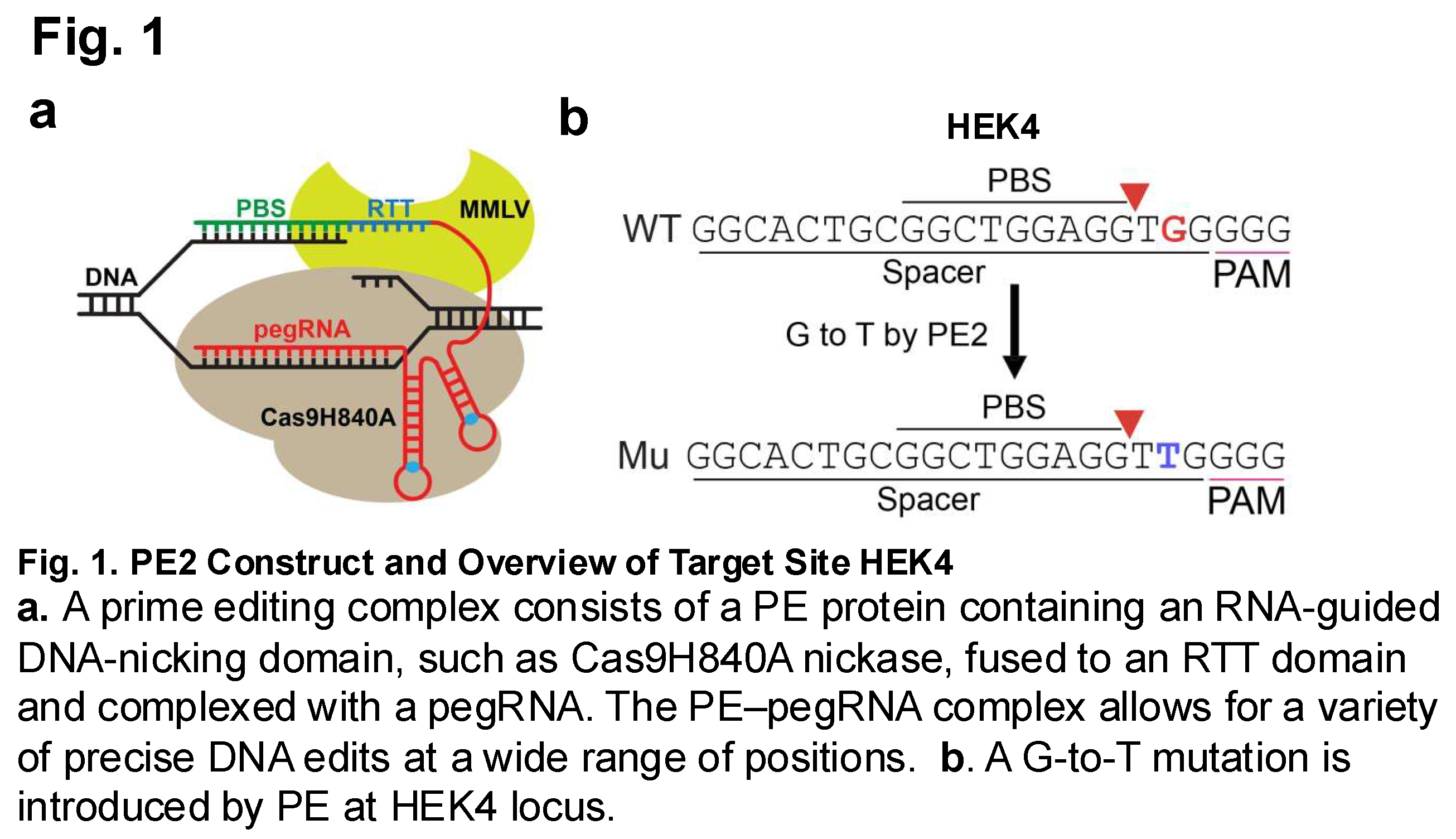

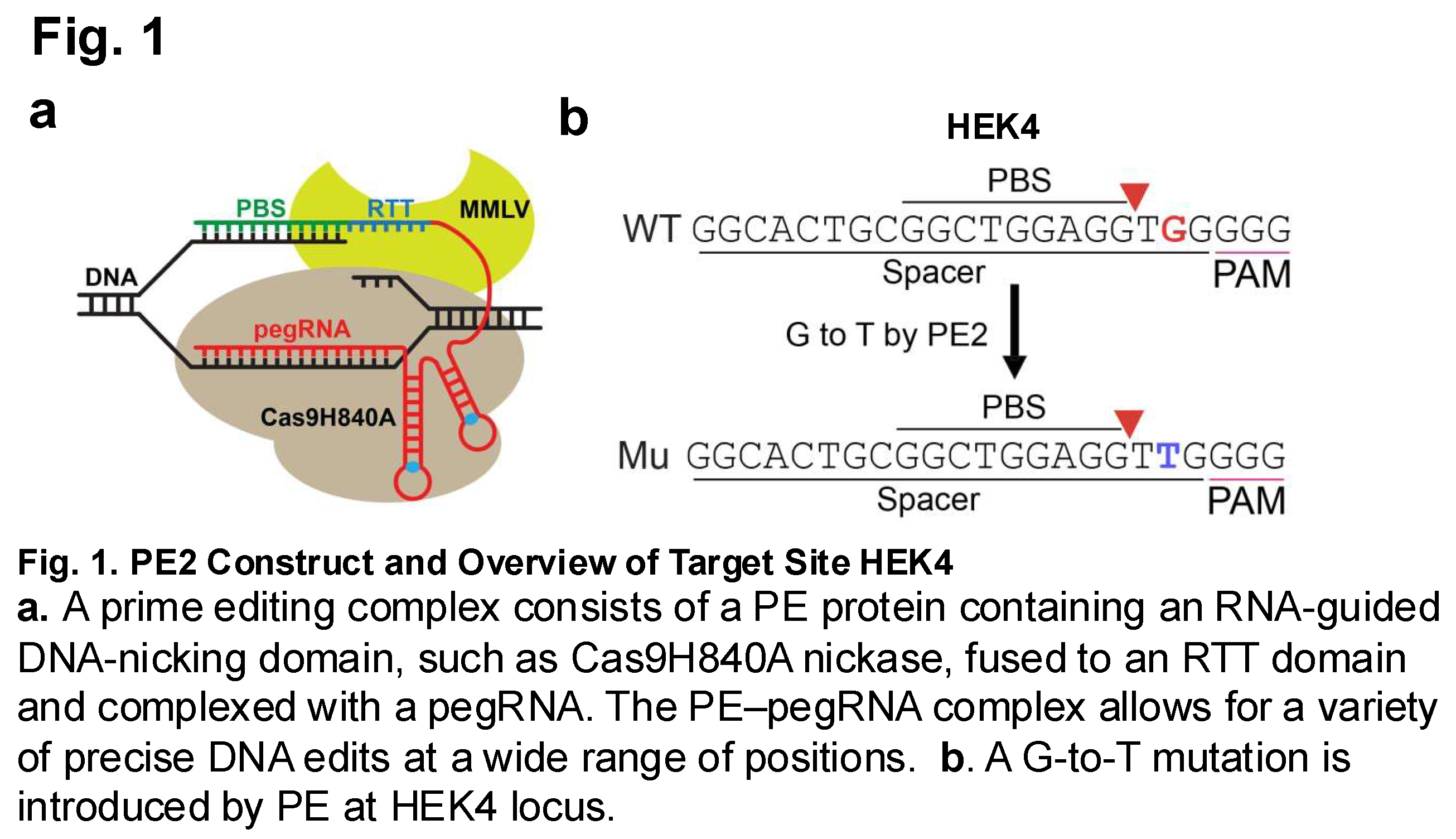

2]. The prime editing system involves the use of a pegRNA (prime-editing guide RNA), reverse transcriptase enzyme, and Cas9 nickase. The pegRNA allows for alignment with PE a target site on a gene of interest. Reverse transcription of an RT template on the pegRNA then results in the synthesis of a sequence of DNA with desired edits [

1,

3,

4]. The resulting single-stranded flap of DNA then has the potential to hybridize with the original DNA strand, and through mismatch repair, the desired edited DNA sequence will be produced [

1]. As a result, prime editing is a new and exciting development in the field of genetic editing that will have the potential to be used in a multitude of various biotechnological and medical applications [

1,

4,

5].

Despite the increased precision of genome modification technologies, some off-target effects can still be observed [

6]. One such example of off-target effects is that of increased methylation of CpG islands in regions that have undergone CRISPR-Cas9 modification [

7]. CpG islands are DNA rich regions containing rich cytosine-guanine dinucleotides [

8]. They typically reside in gene promoter regions, gene enhancer regions, or within genes themselves. Methylation of these CpG islands serve essential genomic functions in vivo, including regulating gene expression. However, off-target methylation due to editing within these regions can result in unintended gene expression alterations. These alterations can impact the efficiency of the edit and the effectiveness of the altered gene target [

7]. Understanding the consequences of off-target effects in genomic editing technologies such as prime editing minimizes unintended genetic alterations, enhancing safety and precision in future therapeutic and research applications.

This study will seek to examine how genome editing through the use of prime editing systems results in increased CpG island methylation similar to that which was observed through the use of CRISPR-Cas9 mediated editing systems. CRISPR-Cas9 and prime editing systems will be used to induce a guanine (G) to thymine (T) transversion at HEK4 site in HEK293T cells. Once the edit has been induced, various methylation sequencing and analysis will be complete using Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing. Comparing the methylation patterns between the two genome editing technologies, CRISPR-Cas9 and prime editing, will provide the necessary information to determine whether similar off-target methylation is seen between the two.

2. Methods

2.1. Plasmids

To generate pegRNA expression plasmids, gblocks or PCR products including spacer sequences, scaffold sequences and 3′ extension sequences were amplified with indicated primers using Phusion master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which were subsequently cloned into a custom vector (Addgene plasmid no. 122089, BfuAI and EcoRI digested) by the Gibson assembly method (NEB). To generate sgRNA expression plasmids, annealed oligonucleotides were cloned into a BfuAI-digested vector [

6]. All plasmids used for in vitro experiments were purified using a Plasmid Midi kit (Qiagen), including an endotoxin removal step. pCMV-PE2 was a gift from David Liu (Addgene plasmid no. 132775) [

1].

Spacers sequences of pegRNA: GGCACTGCGGCTGGAGGTGG

3’ extension sequences of pegRNA: AGAGTCTCCGCTTTAACCCCAACCTCCAGCC

Sequences of sgRNA: GGCACTGCGGCTGGAGGTGG

HDR template sequence:

5’TACTGCGTGGAGACAGACCACAAGCAGGTAAACAAGCAAATA

TGTAAGTCCCAGGTCAGATAAATTTTAGGAAGTGCTGTTTTCCAGT

GGTTCAATGGTCATCCCAGGGCAGAGGTGGGGAGACCTGCTGAG

GGCGGCTTCTCCCTCAGTCAGTCCATGCCTGCAGGGTCTGGAACC

CAGGTAGCCAGAGACCCGCTGGTCTTCTTTCCCCTCCCCTGCCCT

CCCCTCCCTTCAAGATGGCTGACAAAGGCCGGGCTGGGTGGAAG

GAAGGGAGGAAGGGCGAGGCAGAGGGTCCAAAGCAGGATGAC

AGGCAGGGGCACCGCGGCGCCCCGGTGGCACTGCGGCTGGAGGGT

TGTCCGCTGTCACGACTCTGGGGGTTAAAGCGGAGACTCTGGTG

CTGTGTGACTACAGTGGGGGCCCTGCCCTCTCTGAGCCCCCGCCTC

CAGGCCTGTGTGTGTGTCTCCGTTCGGGTTGAAAGGAGCCCGGGAA

AAAGGCCCCAGAAGGAGTCTGGTTTTGGACGTCTGACCCCACCCC

TCCCGCTTAGGGCTTCTGATCCCCCAGGGTGAT-3’

2.2. HEK293T Cells

HEK293T cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Prime editing genome modification system (consisting of a pegRNA, spCas9, and plasmids) was transfected into the cells through the use of Lipofectamine 3000 reagent system.

2.3. gDNA Isolation

gDNA was isolated from the transfected HEK293T cells through the use of the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit [

9].

2.4. Methylation Sequence

Isolated gDNA samples were analyzed via Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS). The data sequences were aligned and transferred into sequenced reads and analyzed in FASTQ file format. Methylation results were calculated by using the ASCII value of each character. If a test result yielded an error rate value, then the base mass of Illumina HiSeq X-ten was expressed as Qphred.

Samples were then sequenced through the use of an Illumina HiSeq sequencing platform.

2.5. Methylation Analysis

Bismarck software was used to statistically analyze the methylation sites. Methylation sites were detected through the alignment of the C-sites (Table 1-4).

Methylation level was calculated:

Base methylation levels

3. Results

3.1. Methylome Evaluations

The modifications induced within the methylome by the prime editor were evaluated using whole genome bisulfite sequencing. Two edited groups (Cas9 and PE2) and their controls, described in Table 1, were evaluated (Figure 1).

3.2. Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing for a Genome-Wide Evaluation of CpG Methylation Patterns

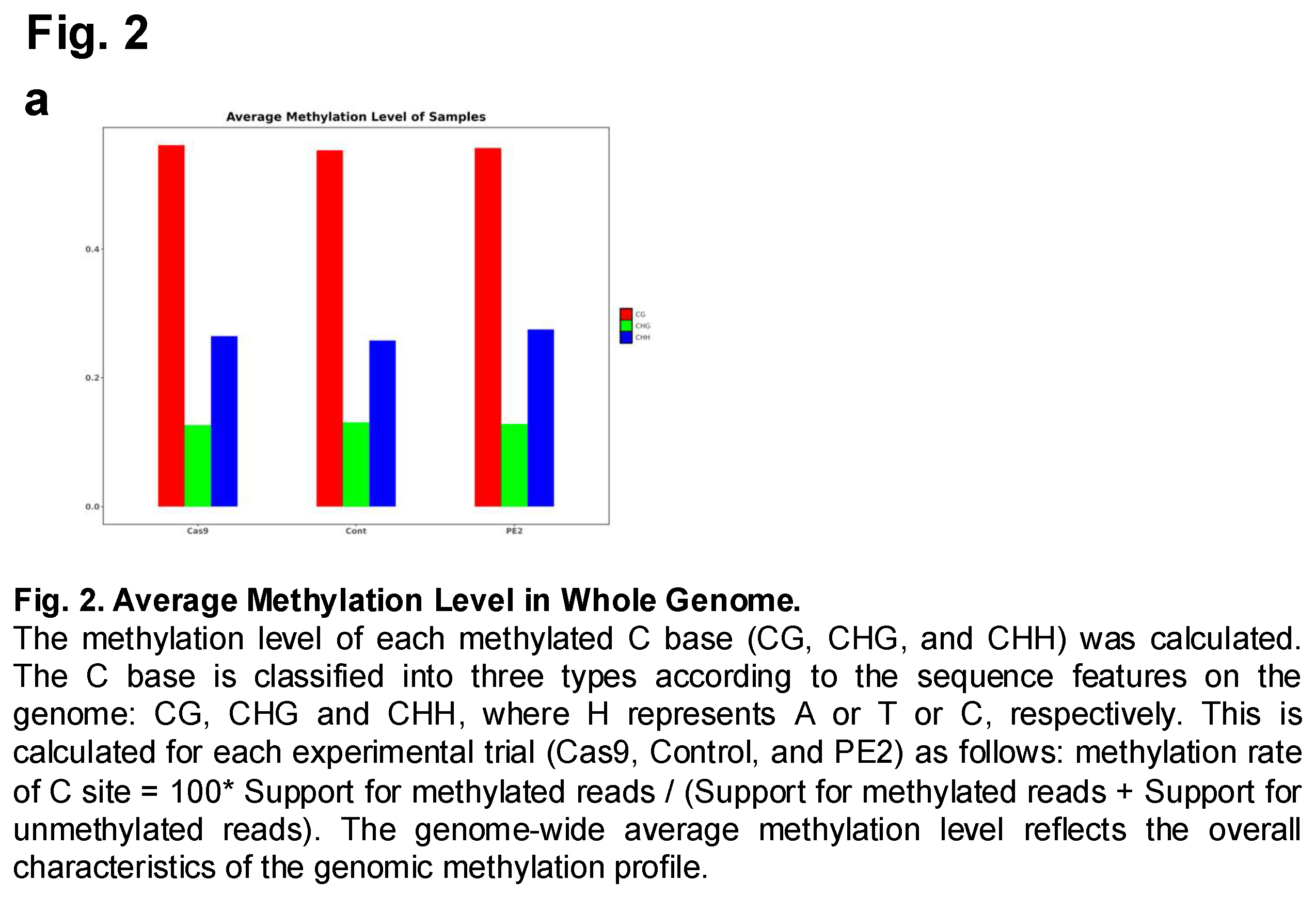

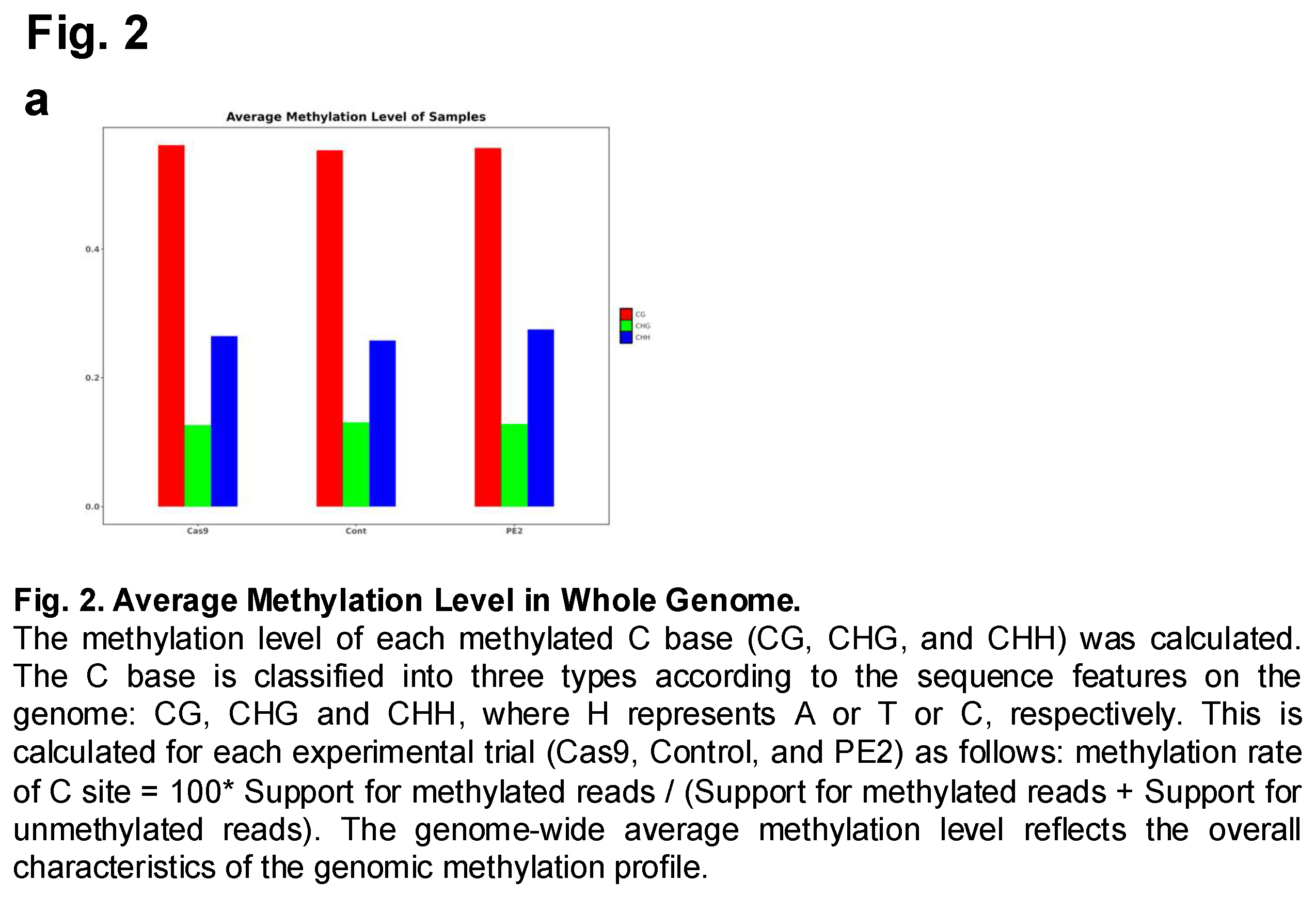

The prime edited gDNA collected from the HEK293T cells were analyzed to assess CpG methylation following prime editing. To accomplish this, an Illumina HiSeq sequencing platform was utilized to generate high-throughput sequencing data from the cell samples that had undergone prime editing. This approach enabled a comprehensive examination of DNA methylation across the genome, allowing for precise quantification of methylation levels at various cytosine sites. The study included three experimental groups: a control group, a Cas9-treated group, and a PE2-treated group. By comparing these groups, researchers aimed to determine whether prime editing or the use of Cas9 had any significant impact on DNA methylation patterns. Following sequencing, the average methylation levels of the three groups were computed and analyzed (Figure 2 and Suppl Figure 1). The focus was placed on three different types of cytosine methylation contexts: CG (CpG sites), CHG, and CHH, where H represents A, T, or C. The results demonstrated that the overall methylation levels across the control, Cas9, and PE2 groups were similar, suggesting that neither prime editing nor the presence of Cas9 led to drastic changes in DNA methylation. However, subtle differences were observed between the groups, indicating that while the methylation patterns remained largely conserved, minor variations existed. These findings suggest that while prime editing does not induce widespread methylation changes, it may still have localized effects on specific genomic regions, warranting further investigation.

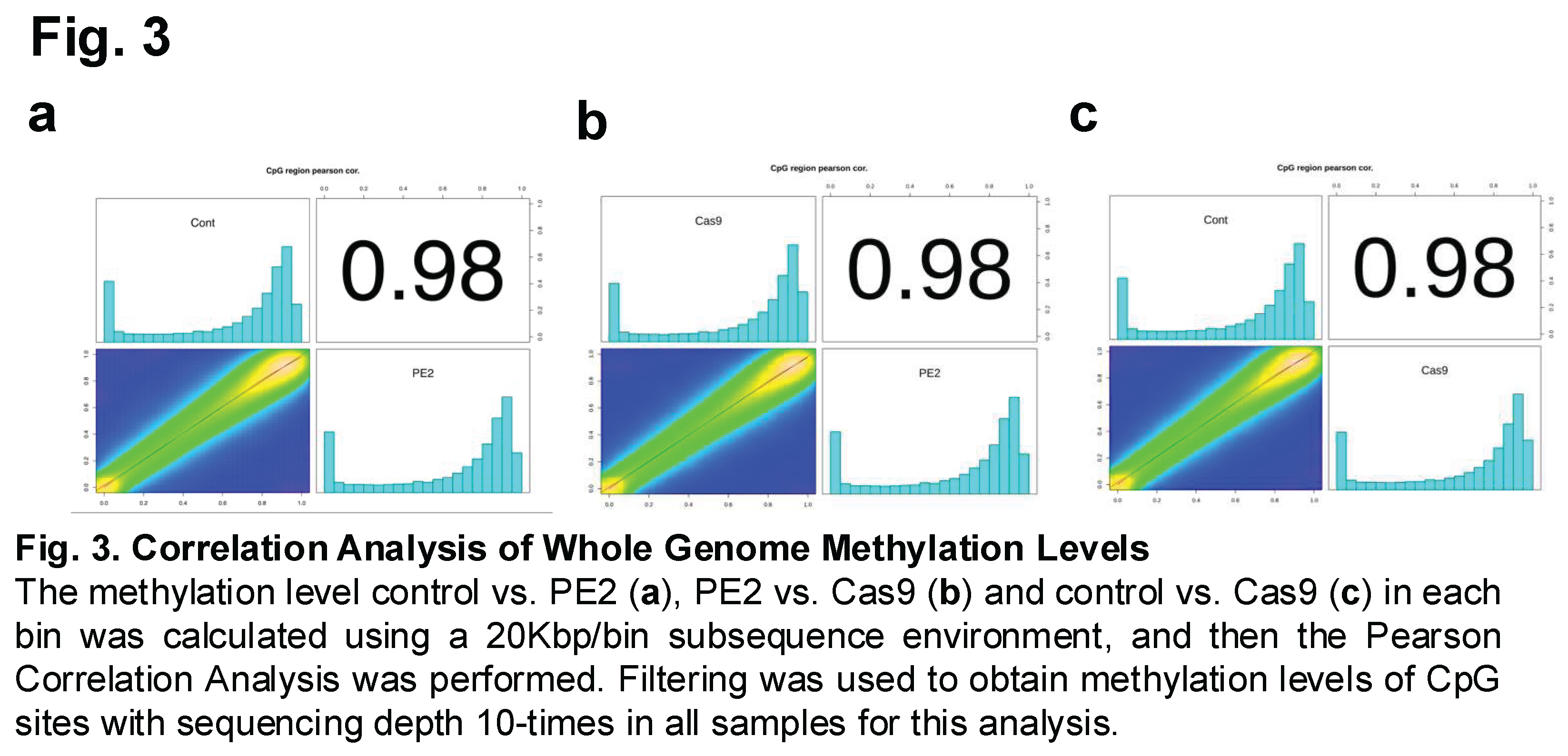

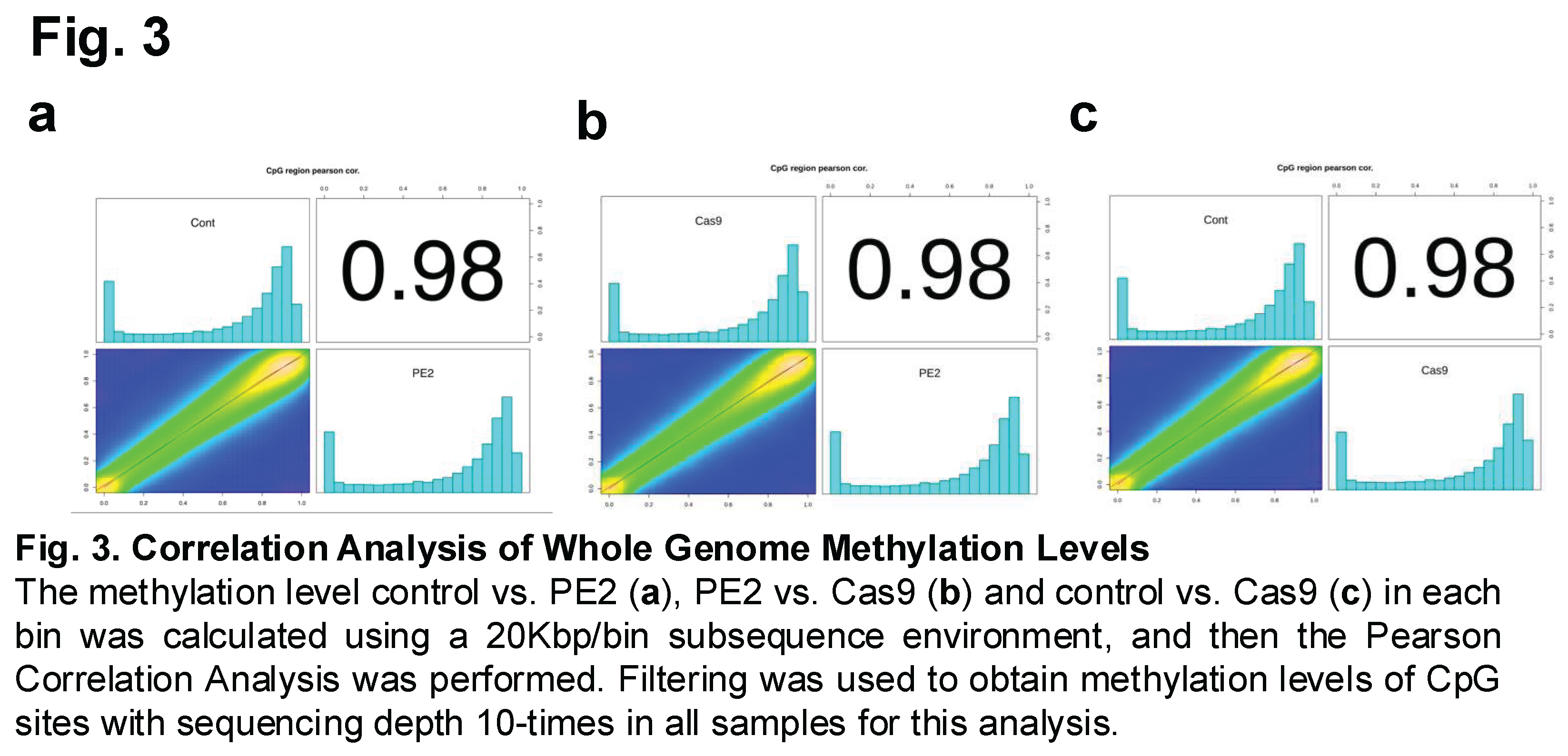

Methylation correlations were then also calculated between the different experimental groups to assess the degree of similarity in DNA methylation patterns following prime editing (Figure 3). This analysis aimed to determine whether the introduction of the PE2 enzyme or the use of Cas9 led to significant deviations in methylation levels compared to the control group. Specifically, Figure 3A compares the control group with the PE2-treated group, Figure 3B examines the correlation between the PE2 and Cas9 groups, and Figure 3C compares the control group with the Cas9-treated group. Correlations of these three comparison groups were found to equal 0.98.

3.3. Differentially Methylated Regions

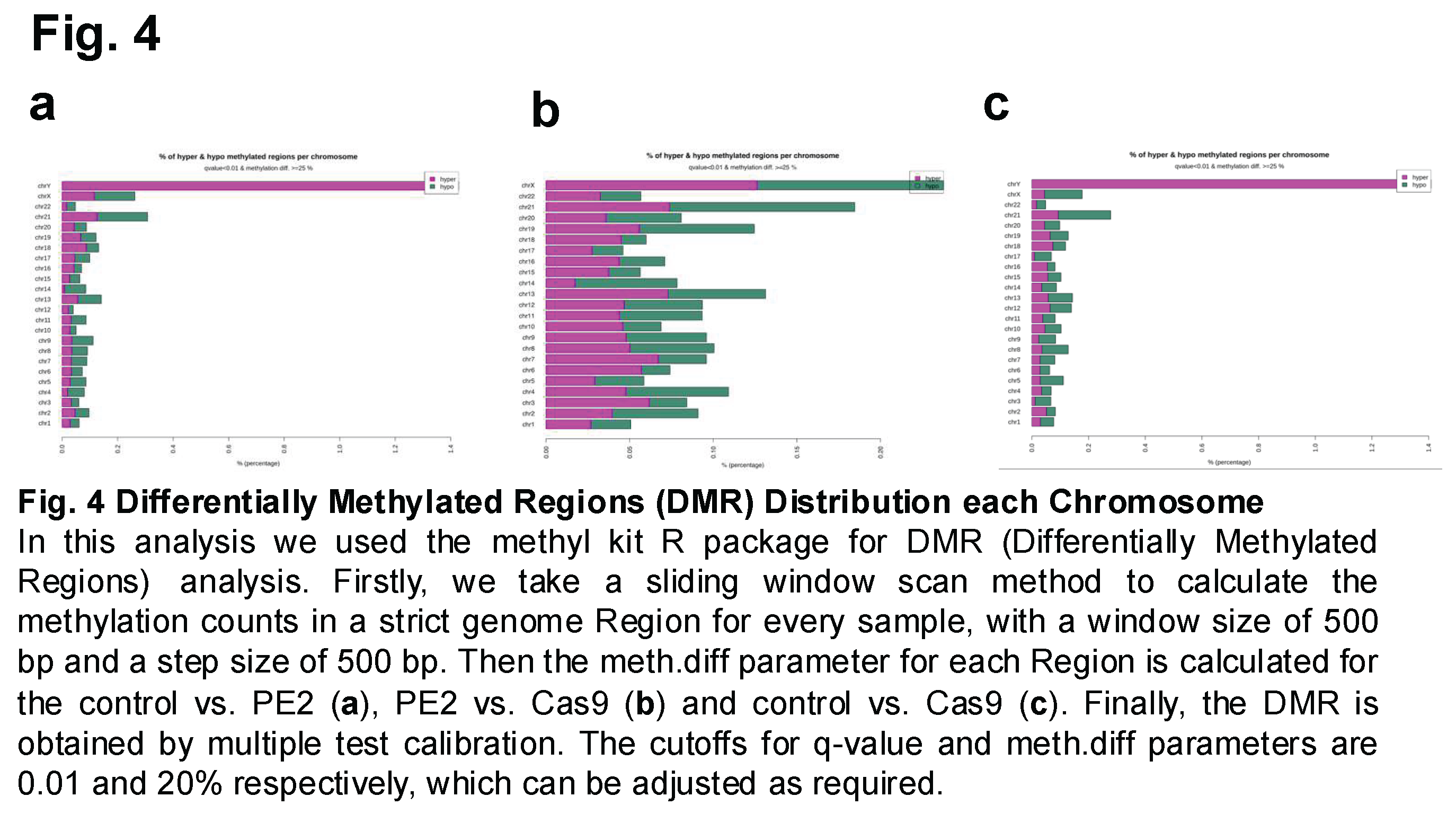

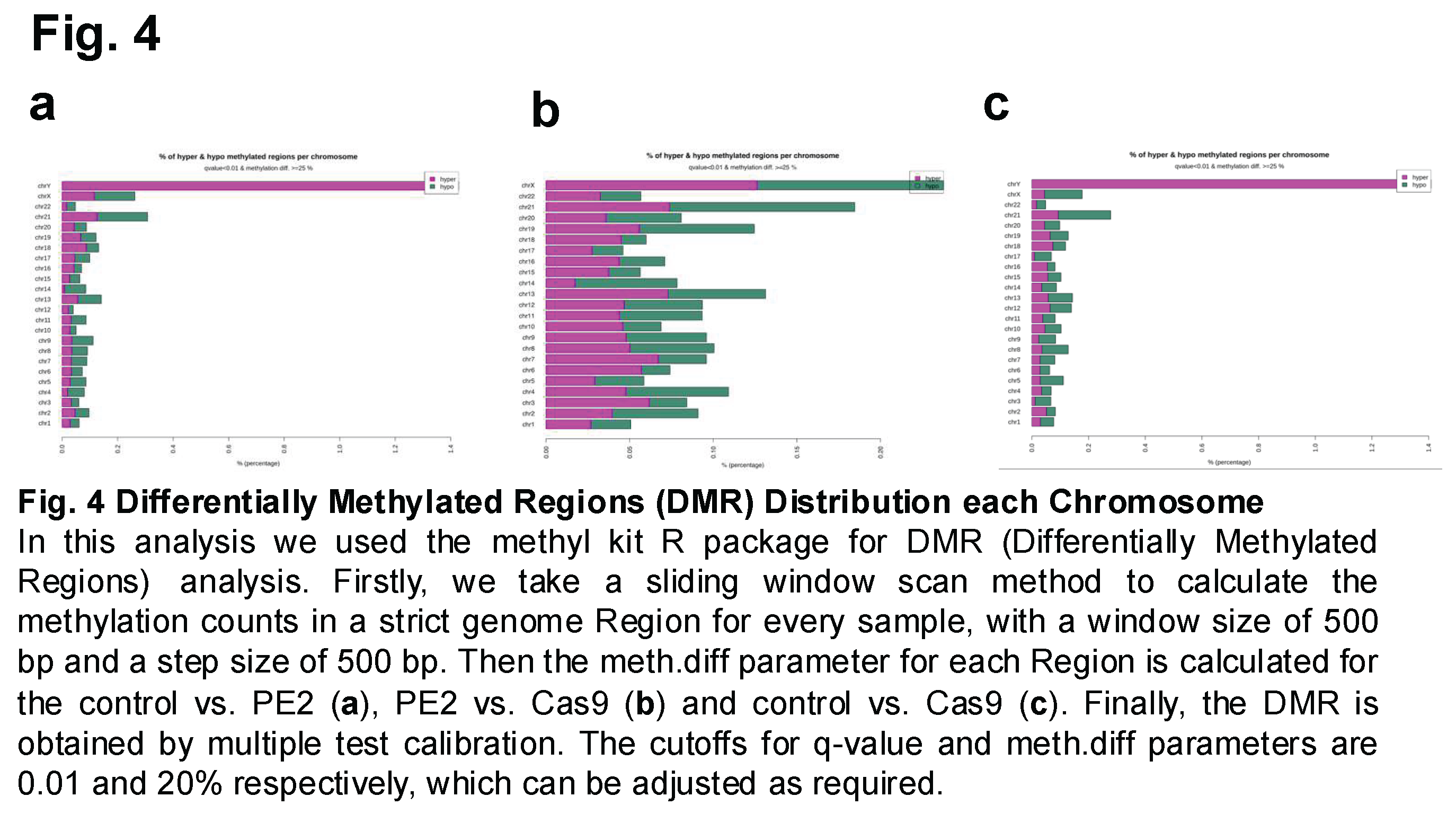

Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) were then analyzed and compared between the three experimental groups to assess whether prime editing or Cas9 treatment induced significant changes in DNA methylation at specific genomic loci. This analysis aimed to identify regions of the genome where methylation levels differed significantly between the groups, potentially revealing localized epigenetic alterations associated with the editing process. Figure 4A represents the comparison between the control group and the PE2-treated group, Figure 4B compares the PE2-treated group with the Cas9-treated group, and Figure 4C illustrates the differences between the control group and the Cas9-treated group. The results indicated that while the overall methylation patterns remained highly correlated across the groups, variations in the percentage of hypomethylated and hypermethylated regions were observed across different chromosomes. The extent of these methylation changes varied depending on the comparison, with certain chromosomes exhibiting a higher proportion of differentially methylated sites than others (Figure 4).

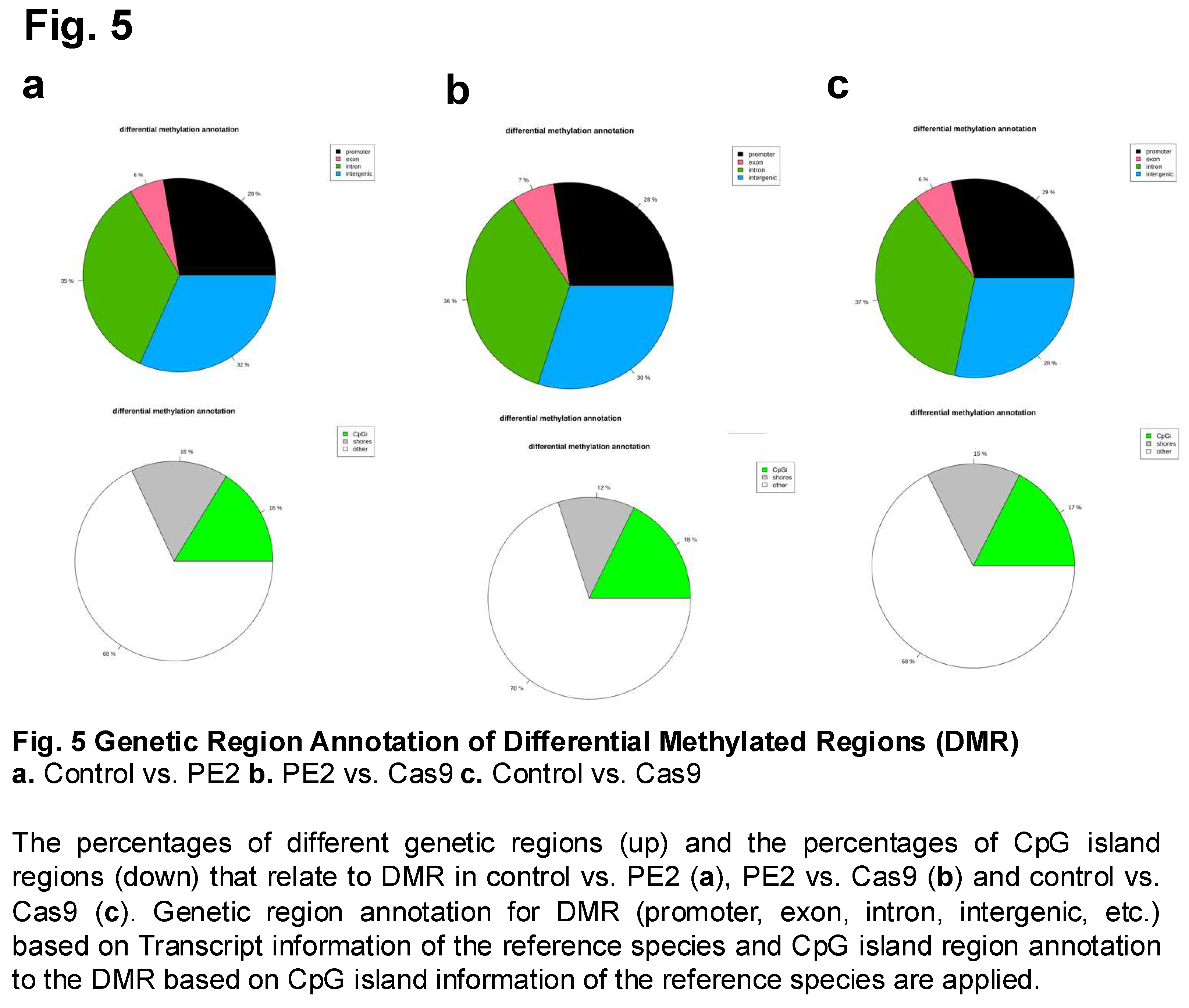

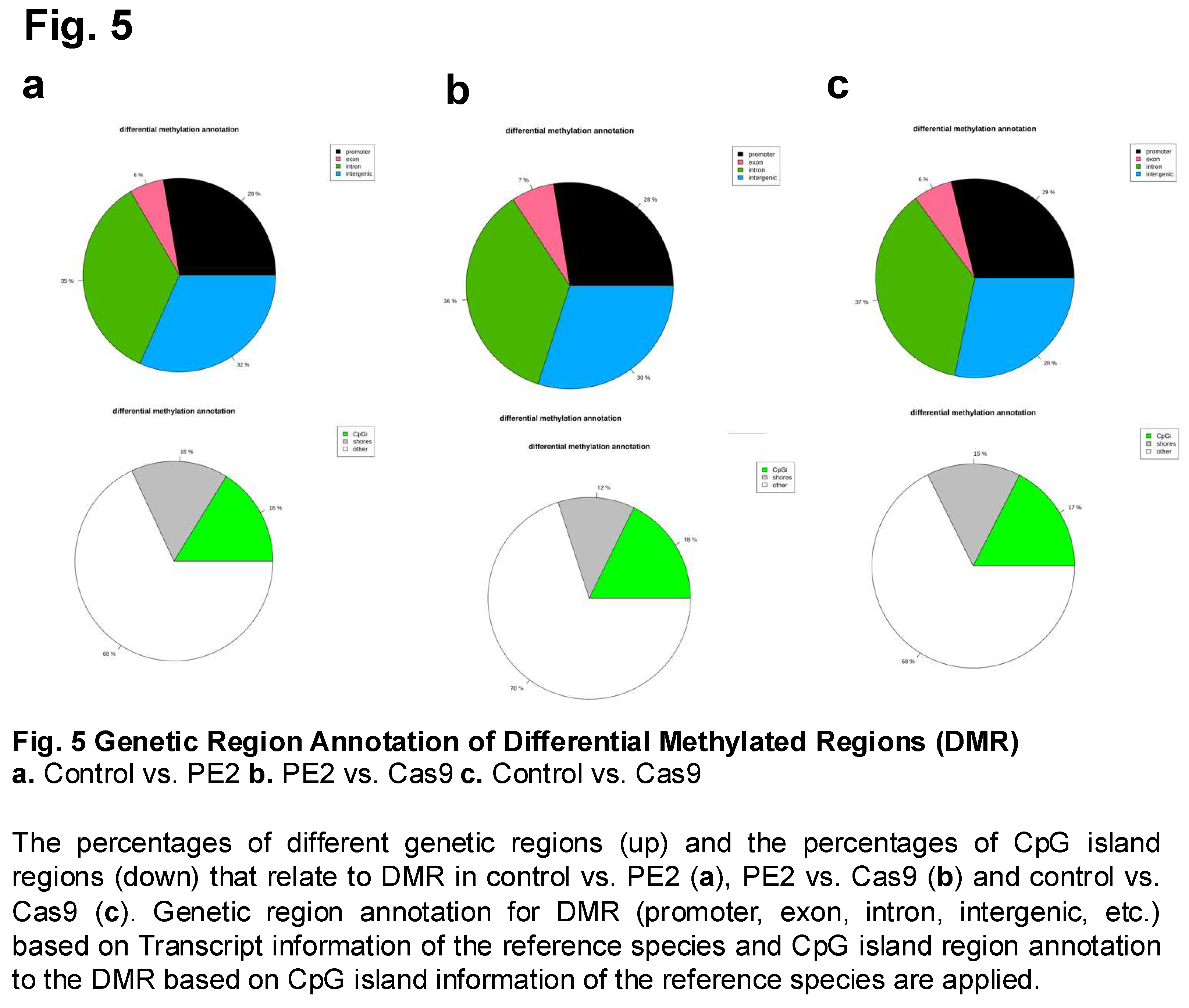

Differential methylation was further examined across various genomic regions to determine whether prime editing or Cas9 treatment influenced methylation patterns in specific functional elements of the genome. This analysis involved comparing methylation differences in promoter regions, exons, introns, and intergenic regions among the three experimental groups: control, PE2, and Cas9 (Figure 5). Since DNA methylation in these regions can have distinct regulatory effects—such as influencing gene expression in promoters or affecting splicing in exons—this comparison provided insights into potential functional consequences of prime editing on the epigenome. Additionally, the methylation levels of CpG islands (CpGi), CpG shores, and other genomic locations were analyzed to assess whether prime editing affected methylation at these regulatory hotspots. CpG islands, which are frequently located near gene promoters, play a crucial role in transcriptional regulation, and changes in their methylation status can significantly impact gene activity. Shores, the regions flanking CpG islands, have also been implicated in gene regulation and epigenetic reprogramming. Notably, the comparison between PE2 and Cas9 (Figure 5B) revealed an increase in methylation levels specifically within exon regions, a trend that was not as pronounced in the control vs. PE2 or control vs. Cas9 comparisons. This finding suggests that prime editing using PE2 may lead to localized epigenetic modifications in coding regions, potentially affecting gene expression or alternative splicing. Furthermore, it was observed that among the three comparisons, the PE2 vs. Cas9 group exhibited the highest percentage of CpG island methylation, reaching 0.18% (Figure 5B).

3.4. Molecular Function

Molecular function enrichment analysis was conducted to compare the different treatment groups and identify potential functional pathways affected by prime editing or Cas9 treatment. This analysis aimed to determine whether specific biological processes or molecular functions were significantly enriched in response to genome editing. Two widely used bioinformatics tools were employed: Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. GO analysis focuses on categorizing genes based on their associated biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components, while KEGG analysis provides insights into metabolic and signaling pathways that may be influenced by genetic modifications.

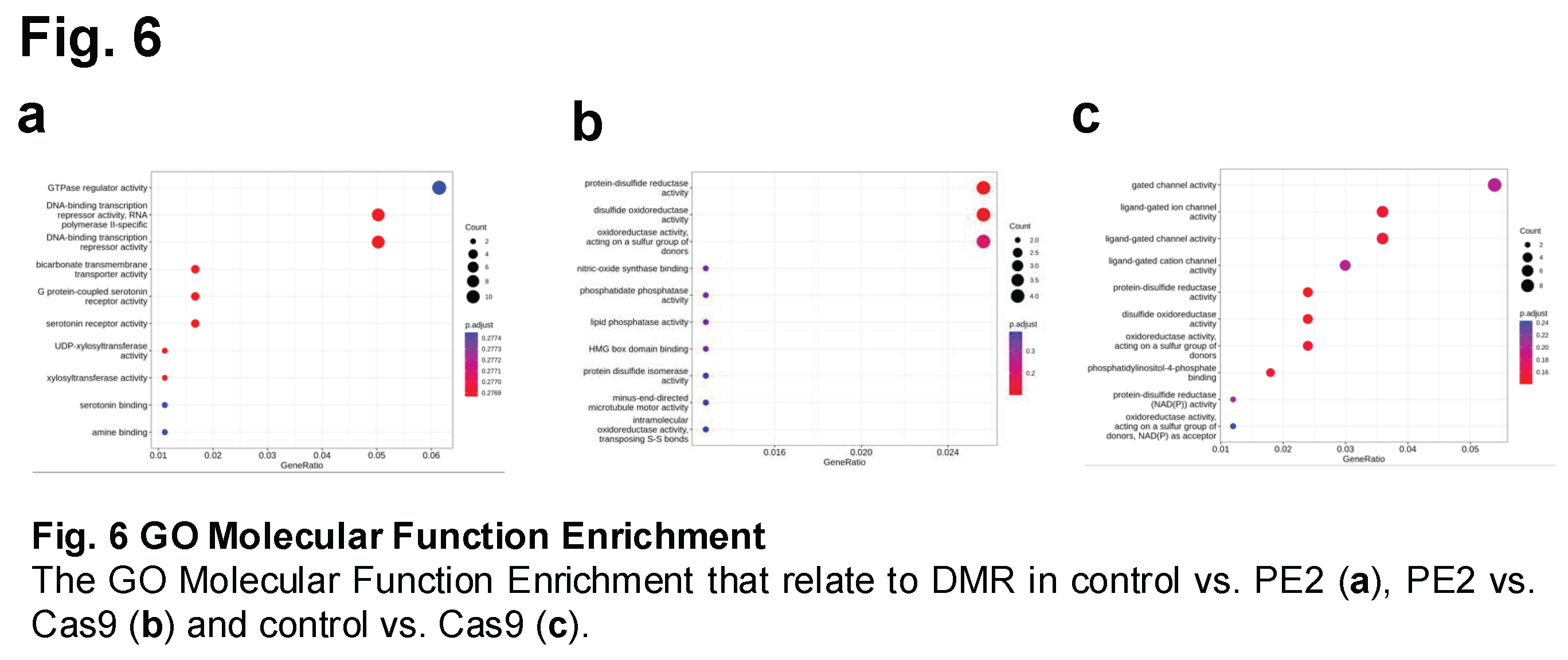

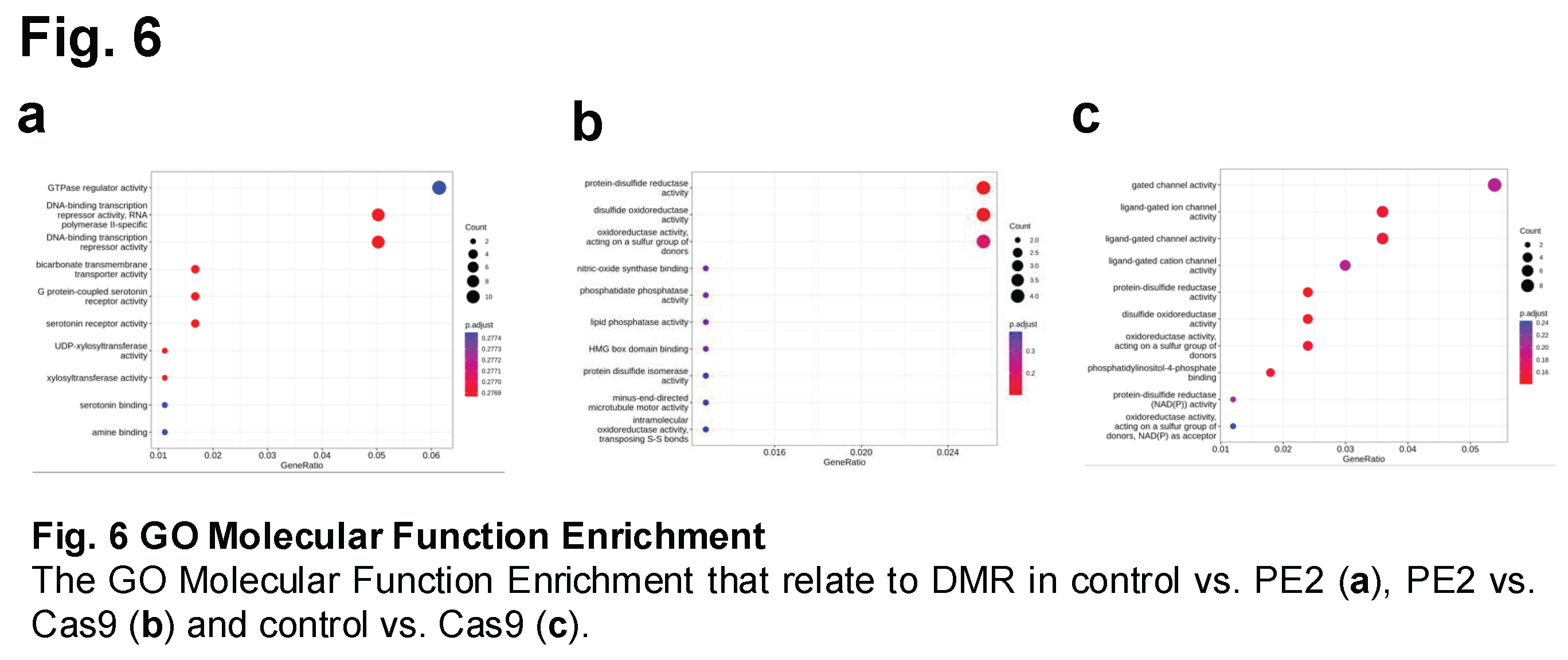

Using Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, molecular function enrichment was assessed by calculating gene ratio enrichment for different functional categories. In the control vs. PE2 comparison, the highest level of enrichment was observed in GTPase regulator activity, with a gene ratio greater than 0.06, suggesting that genes involved in this regulatory pathway were differentially affected by prime editing (Figure 6A and Suppl Figure 2, 3). Following this, the next most enriched functional categories were DNA-binding transcription repressor activity and RNA polymerase II-specific DNA-binding transcription repressor activity, both of which exhibited gene ratios greater than 0.05. In the PE2 vs. Cas9 comparison, enriched molecular functions were identified in protein-disulfide reductase activity and disulfide oxidoreductase activity, with gene ratios exceeding 0.024 (Figure 6B). For the control vs. Cas9 comparison, significant enrichment was observed in functions related to gated channel activity, with a gene ratio greater than 0.05. Specifically, ligand-gated ion channel activity and ligand-gated channel activity were enriched, both exceeding a gene ratio of 0.035 (Figure 6C).

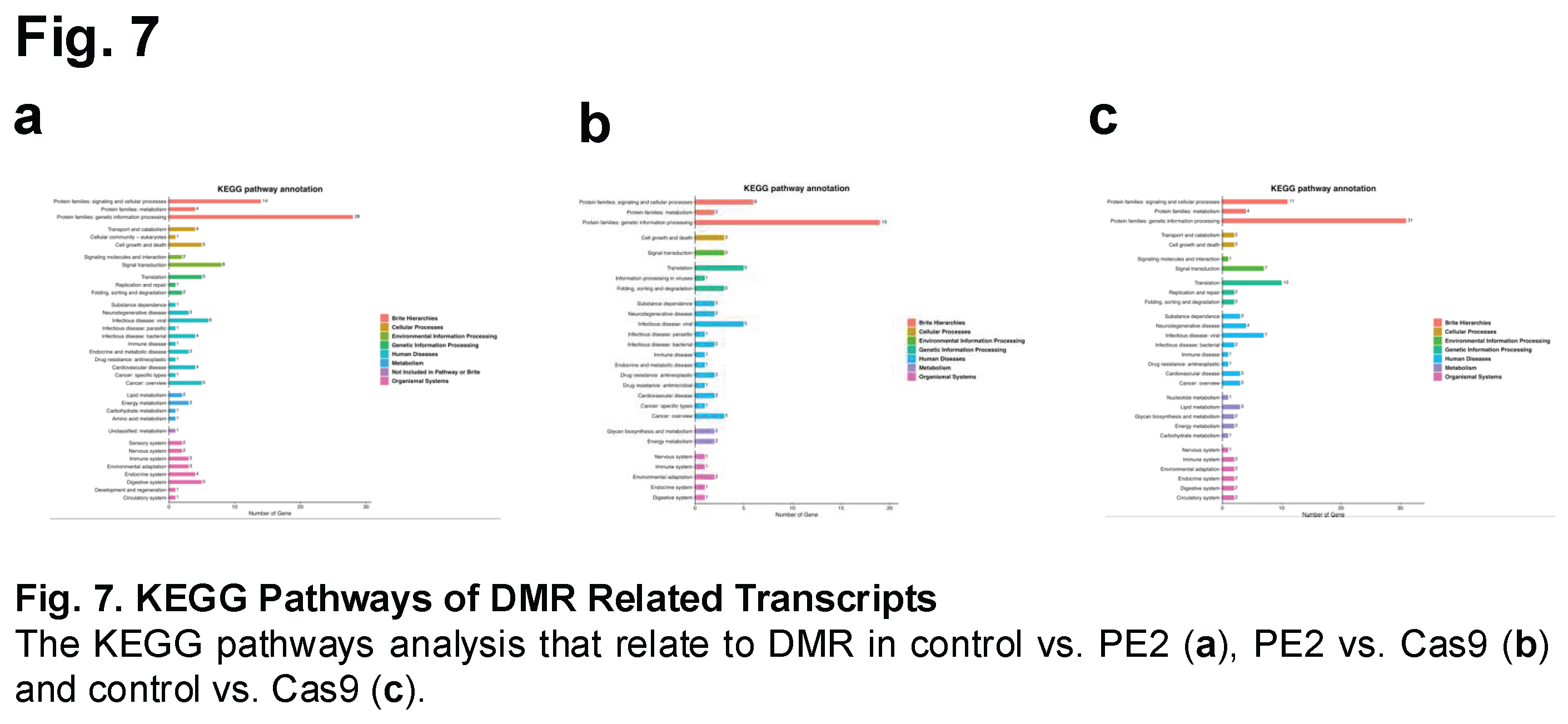

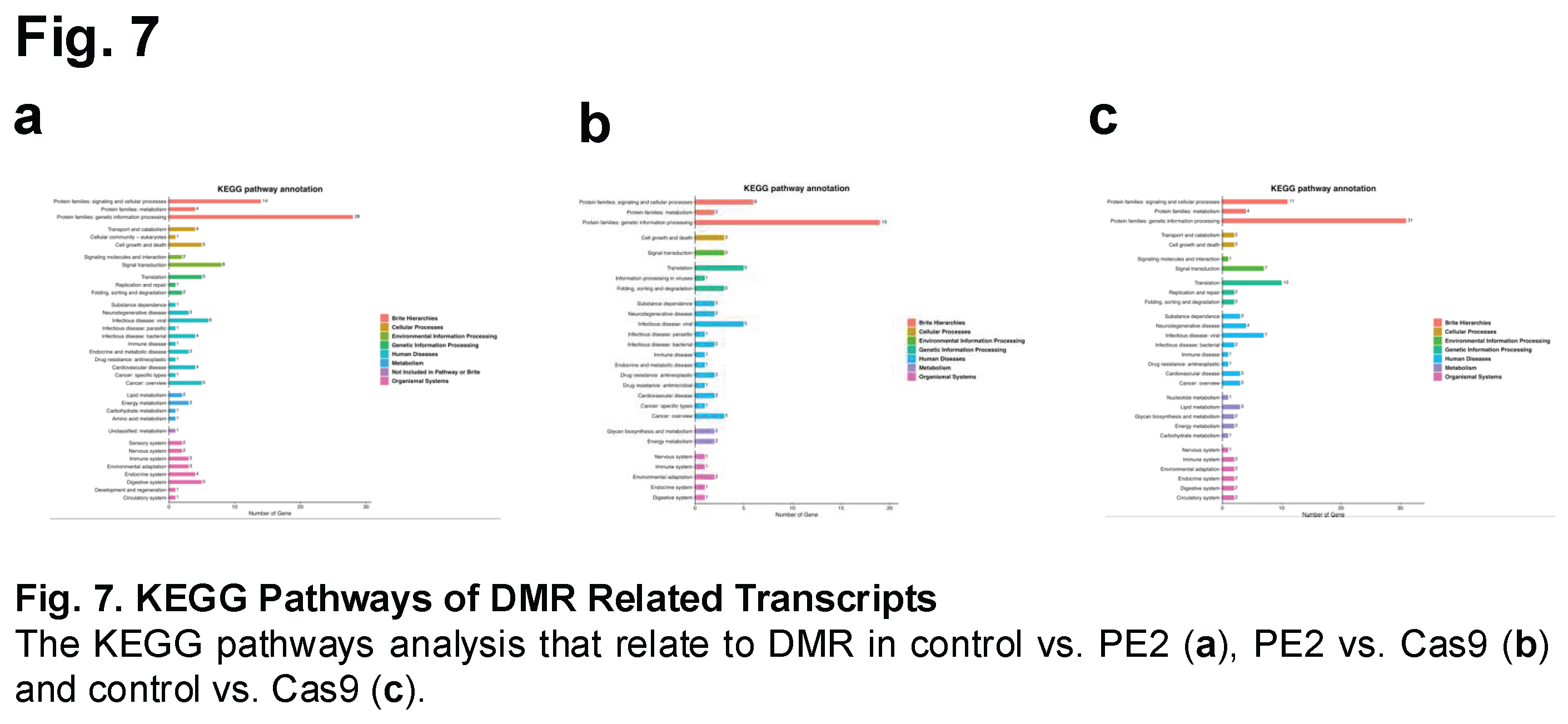

Using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, gene enrichment was assessed across multiple biological processes, including signaling pathways, cellular processes, and genetic information processing (Figure 7 and Suppl Figure 4). The analysis revealed an increased number of genes associated with these pathways across all three experimental groups.

4. Discussion

Prime editing offers a cutting-edge advancement in the field of genome editing, offering a novel approach that enhances the precision and specificity of genetic modifications [

1]. However, unlike traditional CRISPR-Cas9 systems that rely on the introduction of double-stranded breaks, prime editing utilizes a more refined mechanism that enables for target insertion, deletion, and base substitutions without the need for such breaks, thus reducing the risk of unwanted mutations [

10,

11,

12]. This increased accuracy has positioned prime editing as a promising tool for a wide range of applications in biomedical technologies, therapeutic development, and medical research.

Despite its many advantages, prime editing is not without its drawbacks. One area of concern, as with other gene editing platforms, is the potential for off-target effects. These unintended alterations can manifest in various ways, including changes to DNA methylation patterns (which can influence gene expression and genomic stability). In this study, we showed that potential epigenetic consequences of prime editing by examining methylation changes in CpG islands around prime edited sites within HEK293T cells.

Our findings revealed notable differences in methylation patterns between cells that underwent prime editing methods compared to those modified using traditional CRISPR-Cas9 methods. Differences included both alterations to the quantity and distribution of methylated regions. Changes also included the identification of Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) depending on the gene editing system that was employed (prime editing vs. CRISPR-Cas9). Further studies are required to determine the effect of those local epigenetic changes.

Importantly, methylation variation was noted in exonic regions. Since exons play a critical role in protein coding, changes in their methylation status can have profound implications on gene expression and function. This further emphasizes methylation differences that occur when comparing prime editing to traditional CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing methods.

Overall, prime editing represents a powerful and promising tool in the realm of gene editing. However, despite its advantages, it is important that researchers be aware of the unintended epigenetic consequences (particularly off-site methylation effects) that may arise following its use. Similar to observations made with the use of traditional CRISPR-CAS9 editing, prime editing results in the introduction of methylation changes (especially in CpG island regions). These changes have the potential to impact gene expression which can have implications on the efficiency of prime editing systems and the use of prime editing in medical and biotechnological contexts. Ultimately, although prime editing holds great promise for the fields of biotechnology and medicine, more research is needed to further quantify the methylation changes incurred as a result of its use.

Author Contributions

R.J.S.C., I.J.W., P.W., and S.-Q.L. performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript with co-authors. S.-Q.L. and C.J.S. supervised the study and wrote the manuscript with all co-authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Illumina sequencing datasets are available under request. The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Backbone plasmids used for pegRNA and sgRNA cloning are available from Addgene. Source data are provided with this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- Anzalone, A.V., Randolph, P.B., Davis, J.R., Sousa, A.A., Koblan, L.W., Levy, J.M., Chen, P.J., Wilson, C., Newby, G.A., Raguram, A., and Liu, D.R. (2019). Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149-157. [CrossRef]

- Doman, J.L., Raguram, A., Newby, G.A., and Liu, D.R. (2020). Evaluation and minimization of Cas9-independent off-target DNA editing by cytosine base editors. Nat Biotechnol 38, 620-628. [CrossRef]

- Doman, J.L., Pandey, S., Neugebauer, M.E., An, M., Davis, J.R., Randolph, P.B., McElroy, A., Gao, X.D., Raguram, A., Richter, M.F., et al. (2023). Phage-assisted evolution and protein engineering yield compact, efficient prime editors. Cell 186, 3983-4002 e3926. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J., Oyler-Castrillo, P., Ravisankar, P., Ward, C.C., Levesque, S., Jing, Y., Simpson, D., Zhao, A., Li, H., Yan, W., et al. (2024). Improving prime editing with an endogenous small RNA-binding protein. Nature 628, 639-647. [CrossRef]

- Cirincione, A., Simpson, D., Yan, W., McNulty, R., Ravisankar, P., Solley, S.C., Yan, J., Lim, F., Farley, E.K., Singh, M., and Adamson, B. (2024). A benchmarked, high-efficiency prime editing platform for multiplexed dropout screening. Nat Methods. [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.Q., Liu, P., Ponnienselvan, K., Suresh, S., Chen, Z., Kramme, C., Chatterjee, P., Zhu, L.J., Sontheimer, E.J., Xue, W., and Wolfe, S.A. (2023). Genome-wide profiling of prime editor off-target sites in vitro and in vivo using PE-tag. Nat Methods 20, 898-907. [CrossRef]

- Farris, M.H., Texter, P.A., Mora, A.A., Wiles, M.V., Mac Garrigle, E.F., Klaus, S.A., and Rosfjord, K. (2020). Detection of CRISPR-mediated genome modifications through altered methylation patterns of CpG islands. BMC Genomics 21, 856. [CrossRef]

- Gardiner-Garden, M., and Frommer, M. (1987). CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol 196, 261-282. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Liang, S.Q., Zheng, C., Mintzer, E., Zhao, Y.G., Ponnienselvan, K., Mir, A., Sontheimer, E.J., Gao, G., Flotte, T.R., et al. (2021). Improved prime editors enable pathogenic allele correction and cancer modelling in adult mice. Nat Commun 12, 2121. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.H., Miller, S.M., Geurts, M.H., Tang, W., Chen, L., Sun, N., Zeina, C.M., Gao, X., Rees, H.A., Lin, Z., and Liu, D.R. (2018). Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 556, 57-63. [CrossRef]

- Casini, A., Olivieri, M., Petris, G., Montagna, C., Reginato, G., Maule, G., Lorenzin, F., Prandi, D., Romanel, A., Demichelis, F., et al. (2018). A highly specific SpCas9 variant is identified by in vivo screening in yeast. Nat Biotechnol 36, 265-271. [CrossRef]

- Slaymaker, I.M., Gao, L., Zetsche, B., Scott, D.A., Yan, W.X., and Zhang, F. (2016). Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 351, 84-88. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).