1. Decomposing All Natural Numbers into Geometric Sequences

1.1. Background and Objective

We express as a collection of rays parameterized by odd cores and powers of two, providing a structural stage for Collatz dynamics.

1.2. Definitions and Goals

We show and the representation is unique.

1.3. Prime Factorization and Classification

Every

decomposes uniquely as

1.4. Exhaustion of Odd Numbers

Any odd k is with , giving .

1.5. Exhaustion of Even Parts

For each odd k, the ray exhausts the even multiples of k.

1.6. Construction of S and Uniqueness

By the above, every

with

. If

then

, forcing

and

since the left side is odd rational and the right is a power of two. Hence

bijectively.

1.7. Remarks from the Collatz Perspective

For odd k, is even and belongs to some ray . This exhibits inter-branch connections. However, the assertion that every number lies on a finite forward path to 1 (global convergence) is a separate issue (coverage) made precise by thm:reduction; it is not implied by the mere classification .

Takeaway of Chapter 1. We obtain a clean, bijective indexing of by odd core and 2-adic height, furnishing a coordinate system on which later structural/affine arguments are staged.

2. The Structure of the Collatz Tree

2.1. Definition (Branches and Trunk)

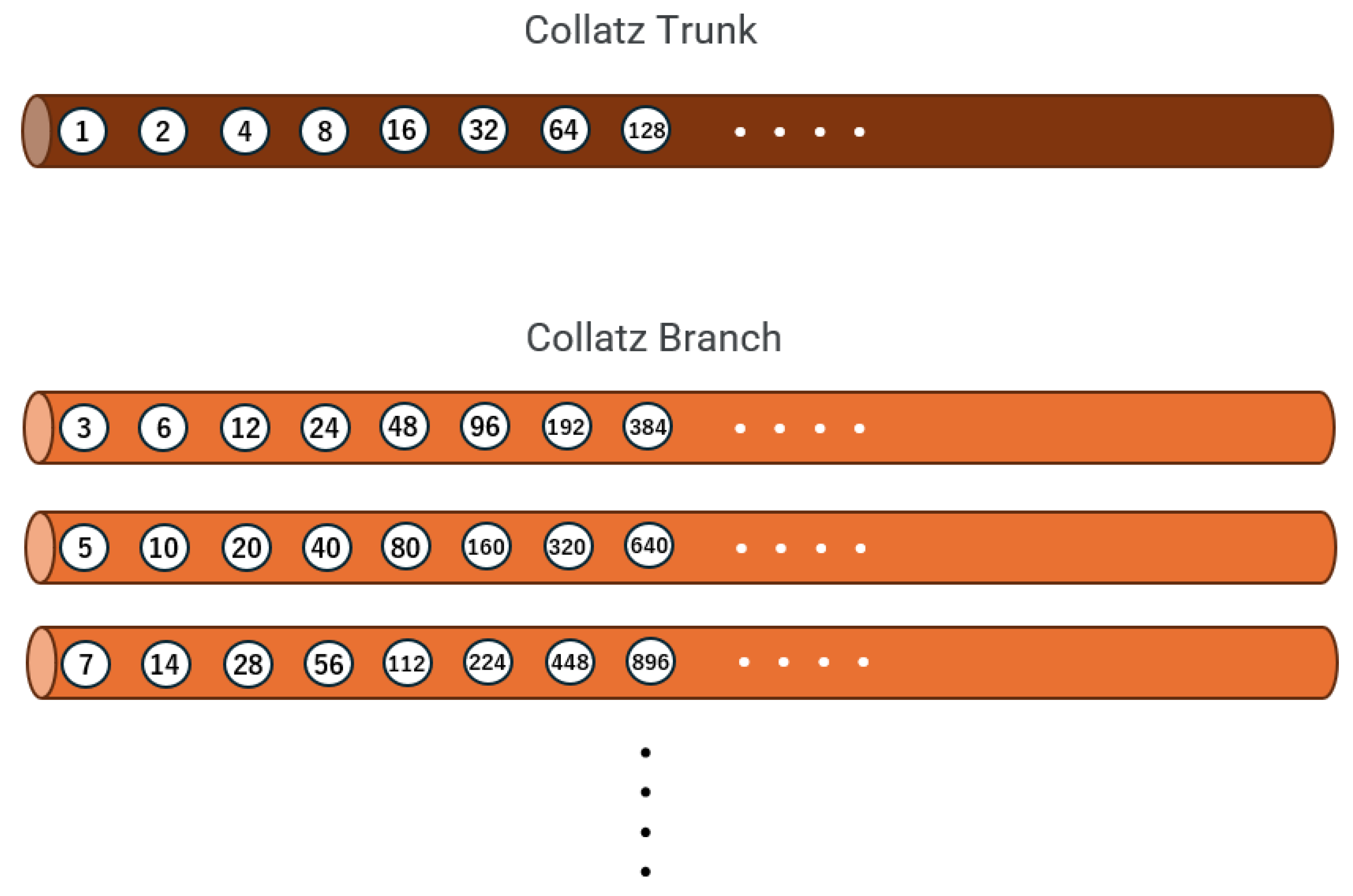

Define the trunk and for each odd the branch . These rays partition disjointly.

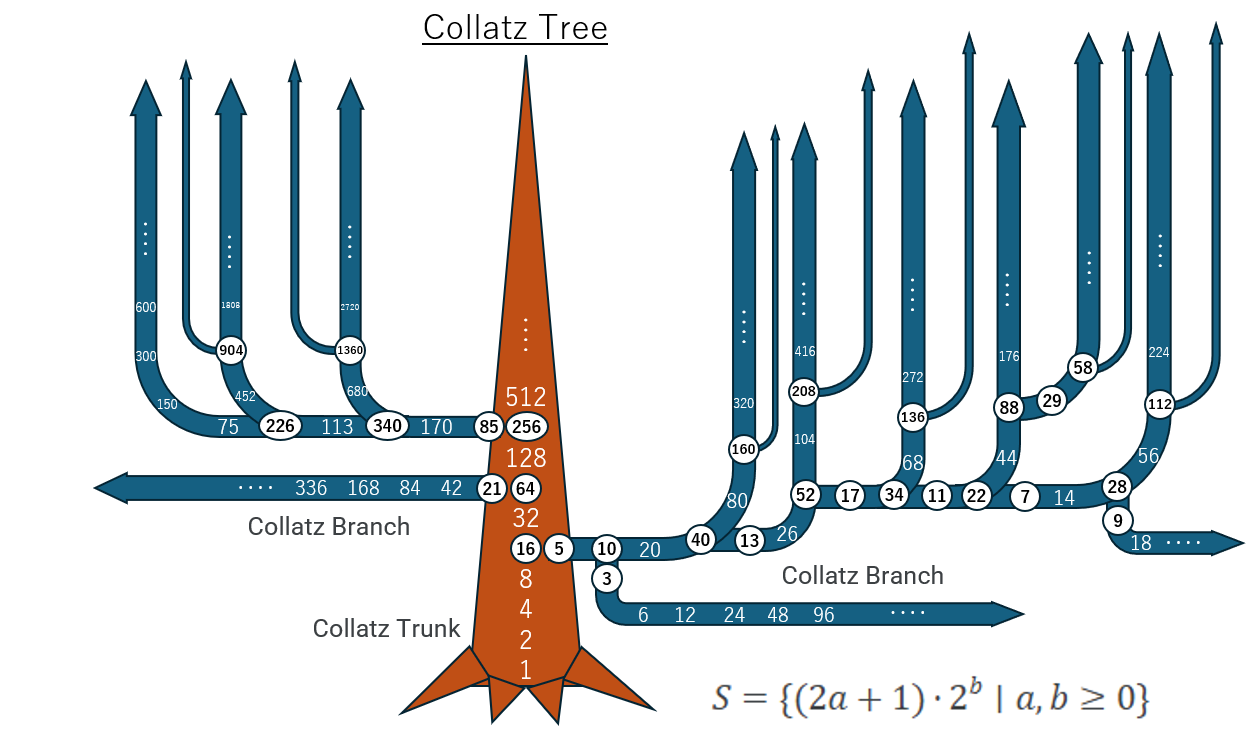

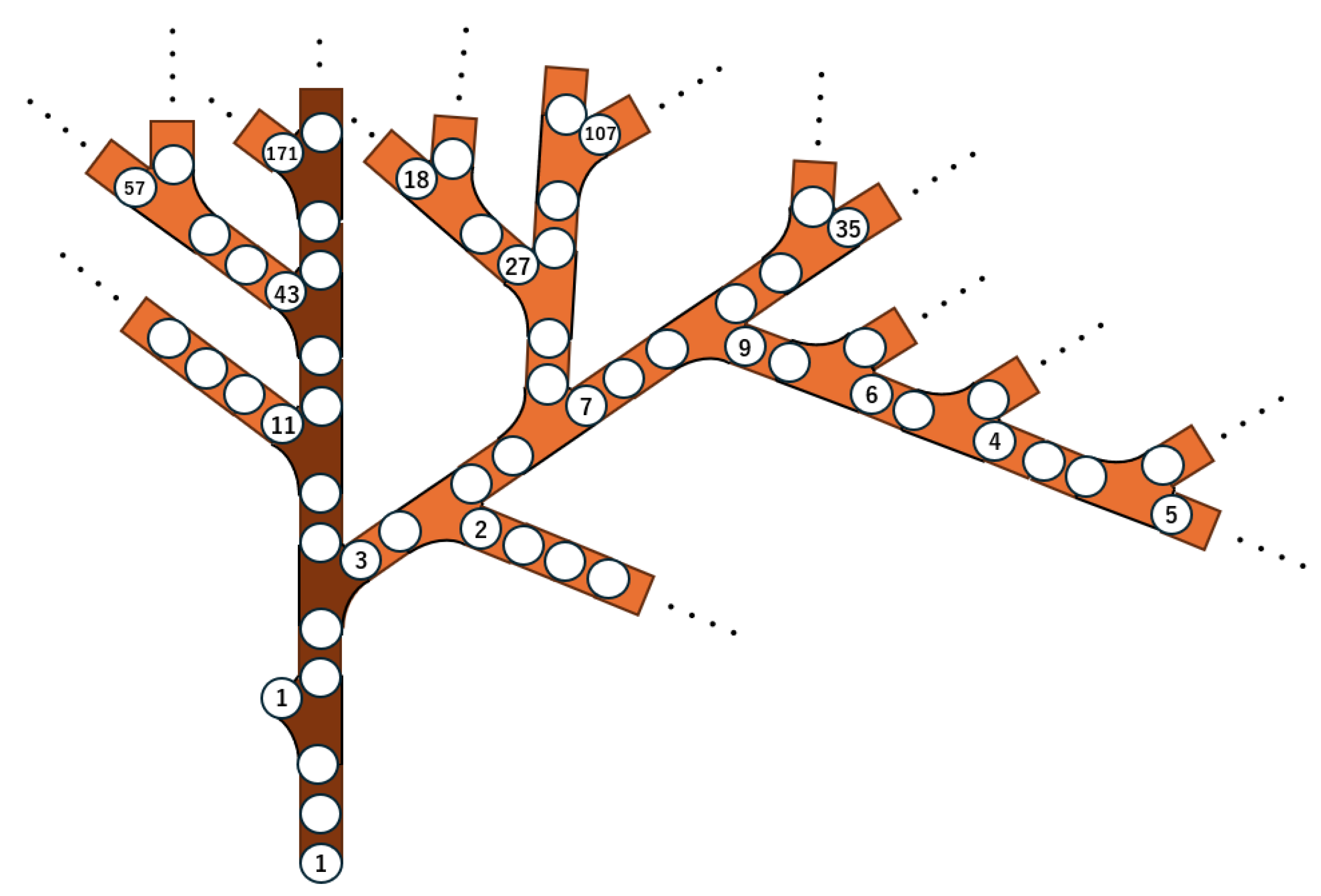

Figure 1.

Trunk and branches (schematic; reverse orientation when embedded into the inverse graph: edges point to preimages).

Figure 1.

Trunk and branches (schematic; reverse orientation when embedded into the inverse graph: edges point to preimages).

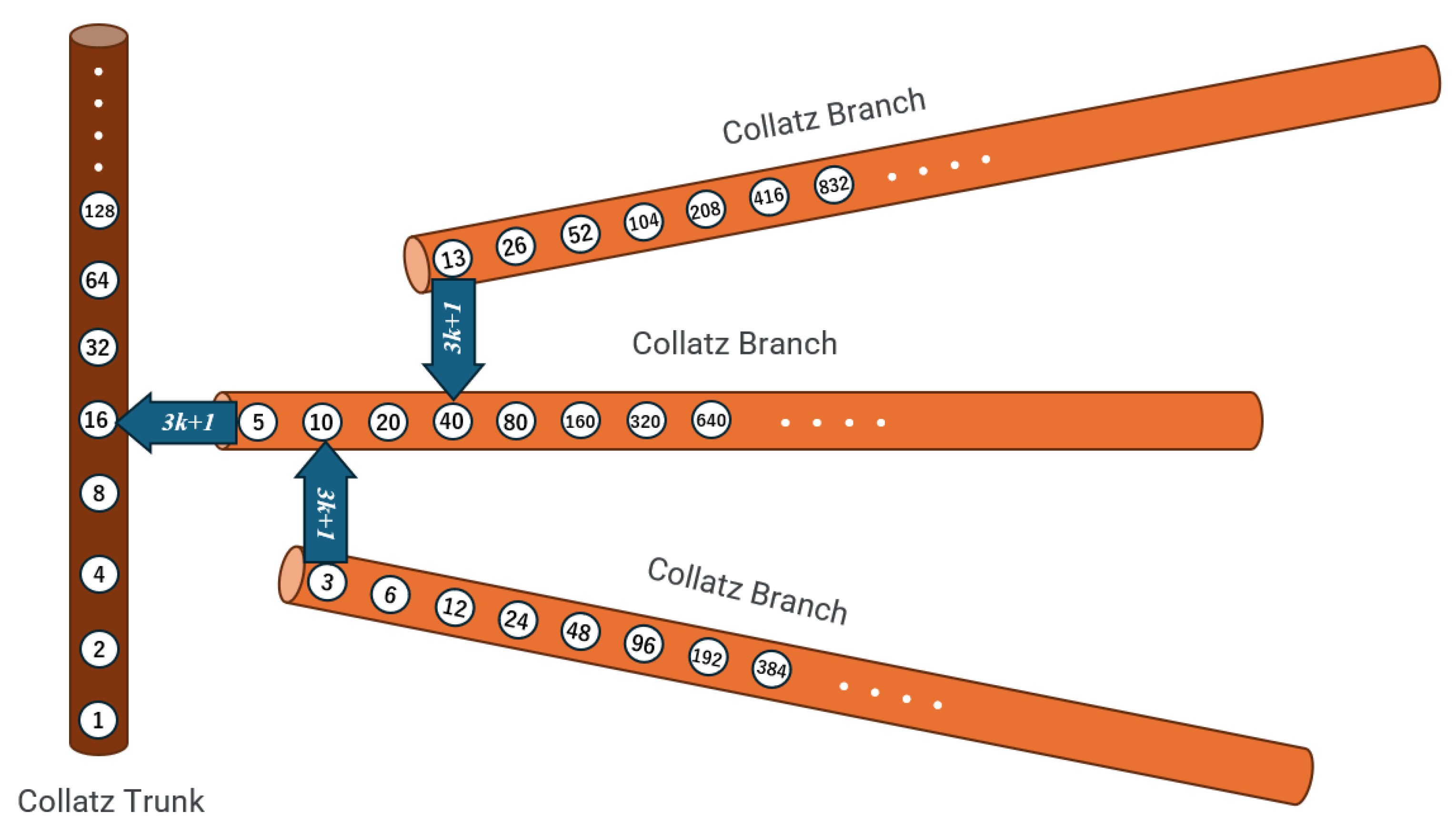

2.2. Branch–Branch Links via

Given odd k, is even and decomposes as , indicating where the branch from k can merge into another branch/trunk in forward dynamics. This shows linkage patterns but does not by itself prove global coverage of the tree by reverse generation.

Figure 2.

Branch connections (schematic; reverse orientation: edges point to preimages).

Figure 2.

Branch connections (schematic; reverse orientation: edges point to preimages).

2.3. Forward vs. Reverse Orientation

Let the standard forward map be

The forward graph (edges ) is a functional digraph (outdegree 1). We do not call it a DAG because it contains the trivial 3-cycle; nontrivial finite cycles are excluded later (sec:affine).

The reverse (preimage) graph rooted at 1, with edges to preimages under f, is a true DAG: levels increase with each application of a reverse step.

2.4. Tree Language

When drawing a reverse BFS tree rooted at 1, each node is assigned a unique parent by construction (though a number may have up to two preimages as graph children). Connectivity of every node to 1 in the forward sense is equivalent to coverage of the reverse tree, which is equivalent to the Collatz convergence; see Theorem 4.

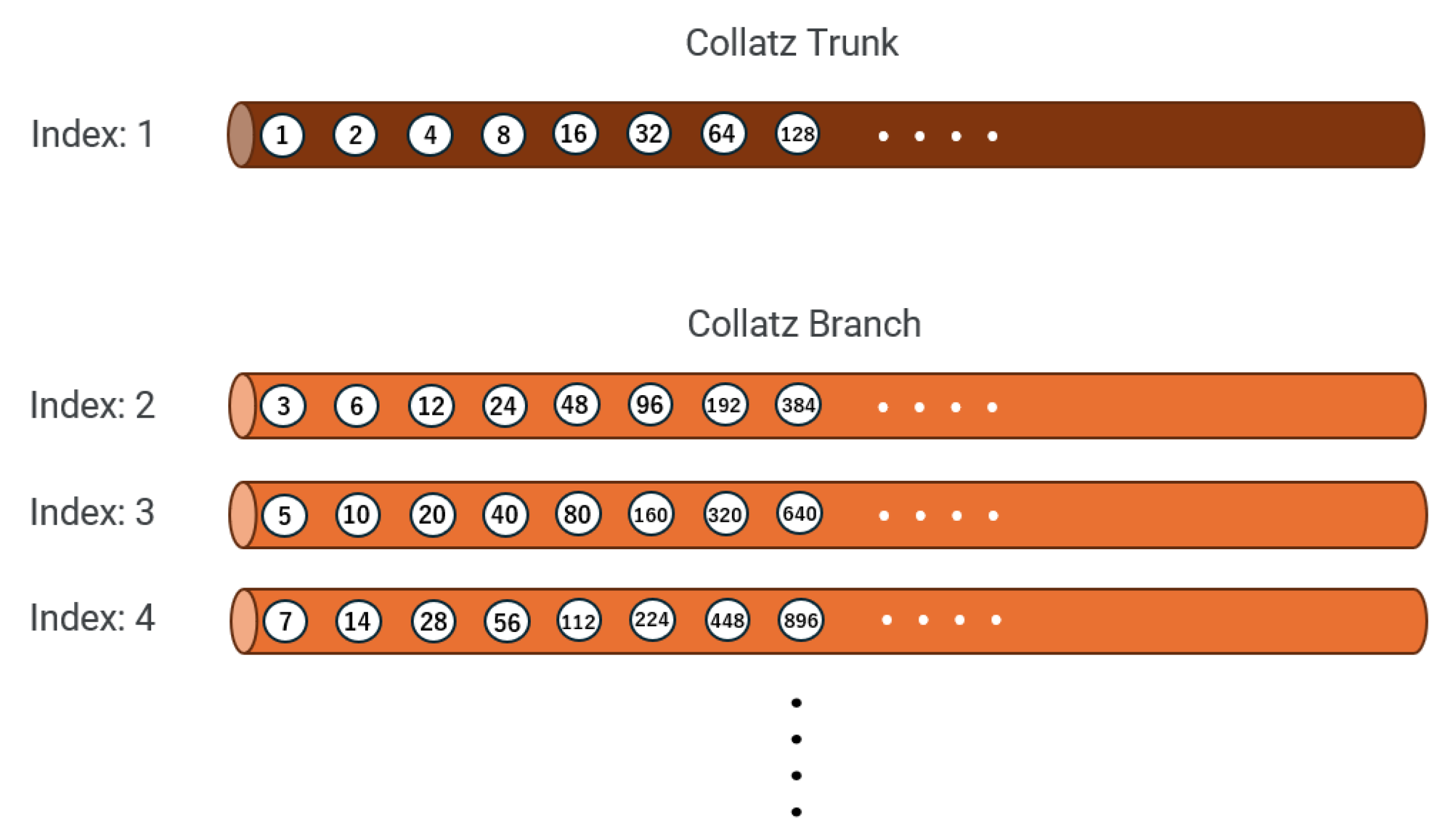

3. Trunk–Branch Indexing of the Natural Numbers

Definition 1 (Odd core, 2-adic valuation). For , write uniquely where is odd and is the exponent of 2 in n.

Definition 2 (Trunk and branches). The trunk is . For any odd , Then is a disjoint partition of .

Definition 3 (Indices).

Order the odd numbers as . Assign the branch index , so that and , , etc. Define the height . Set

Theorem 1 (Complete classification). The map is a bijection from onto .

Proof. Uniqueness of and is immediate; disjointness/exhaustiveness of rays follows. □

Figure 3.

Trunk–branch indexing (schematic; reverse orientation in the inverse graph).

Figure 3.

Trunk–branch indexing (schematic; reverse orientation in the inverse graph).

Figure 4.

Indexed reverse tree (schematic; edges point to preimages).

Figure 4.

Indexed reverse tree (schematic; edges point to preimages).

Table: Trunk–Branch Indexing (sample)

| Odd k

|

Index |

Next Index (rule) |

parity-based trend |

transition factor |

| 1 |

1 |

– |

– |

– |

| 3 |

2 |

3 |

increase |

|

| 5 |

3 |

1 |

decrease |

|

| 7 |

4 |

6 |

increase |

|

| 9 |

5 |

4 |

decrease |

|

| 11 |

6 |

9 |

increase |

|

| 13 |

7 |

3 |

decrease |

|

| 15 |

8 |

12 |

increase |

|

| 17 |

9 |

7 |

decrease |

|

| 19 |

10 |

15 |

increase |

|

4. Affine Word Method: Absence of Nontrivial Finite Cycles

We encode even/odd steps as affine maps and use finite-word compositions to prove absence of nontrivial finite cycles.

Definition of the three-way map T.

Define

by

Elementary steps.

(For odd

n, choose

if

, and

if

.)

Words and composition.

For any finite word

W over

, the composition is affine:

Writing

,

,

, we have

and the denominator of

divides

(each

contributes

, each

contributes

;

E does not increase the power-of-two denominator).

Lemma 1 (No for nonempty words). If W is nonempty then cannot hold.

Lemma 2 (Odd numerator for

).

so the numerator is odd (even minus odd).

Lemma 3 (If

, a periodic solution cannot be integral).

Since , we have . By lem:oddnum-en, . Hence

and the odd denominator cannot cancel . Thus x is not an integer.

Lemma 4 (If , contraction; the only integer fixed point is 1). When , , so any integer periodic point must be a fixed point. Solving and yields as the only integer fixed point.

Theorem 2 (Loop-freeness for T). Under the three-way rule above, the map T admits no finite cycle other than the trivial 1-cycle.

Proof. By lem:a1-en, consider . If , Lemma 3 rules out integer . If , lem:mzero-en leaves only as a fixed point. □

Interpretation. If an even step E appears at least once, a factor remains in the numerator of and cannot be canceled by the odd denominator, so no integer fixed point arises. If E never appears, the composition is a contraction and the only integer fixed point is 1. This algebraic loop-elimination aligns with the inverse-generation intuition.

5. Bridge to the Accelerated Collatz Map

Let the standard accelerated map on odd integers be

We show: If A had a nontrivial finite cycle, then T would have one as well.

Coefficient matching.

If one tour of the A-cycle multiplies by , take on the T-side a word with and so that .

Constant congruence by adjacent swaps.

For adjacent swaps (), the normalized constant changes by where and u is an odd unit modulo D. Using the order of 3 modulo prime powers of D and CRT, one can realize any residue class mod D.

Realizability (intermediate consistency).

Parity and constraints at each step reduce to a finite system of linear congruences for the initial value x. The same swap operations adjust by controlled powers of two, allowing a simultaneous solution by CRT.

Theorem 3 (Bridge, complete version). If the accelerated map A has a nontrivial finite cycle, then the map T has a nontrivial finite cycle.

Corollary 1 (No nontrivial finite cycle for A). Combining thm:loopfreeT-en with thm:bridge-en, the accelerated Collatz map A has no nontrivial finite cycle.

6. Reduction to Convergence

A functional digraph with outdegree 1 decomposes into a directed cycle with an in-tree (basin). By cor:acc-en, the only allowed cycle is 1. Thus global convergence splits into two independent pillars: (i) cycle-freeness (proved here) and (ii) coverage.

Theorem 4 (Reduction to convergence). For the accelerated map A, the following are equivalent:

Proof. Each connected component of a functional digraph is a directed cycle with an in-tree. Since only the 1-cycle is permitted (cor:acc-en), global convergence holds iff every node is in the basin of 1, i.e. iff the inverse tree covers . □

7. Related Work

The affine-composition viewpoint with coefficient is classical in studies of cycles and their lengths (in our three-way encoding, ). Our novelty is to integrate (i) the trunk–branch indexing and inverse-tree structure, with (ii) a complete loop-elimination for the three-way map T, and (iii) a bridge transporting hypothetical cycles of A into T, thereby isolating cycle-freeness as a stand-alone pillar and reducing full convergence to coverage.

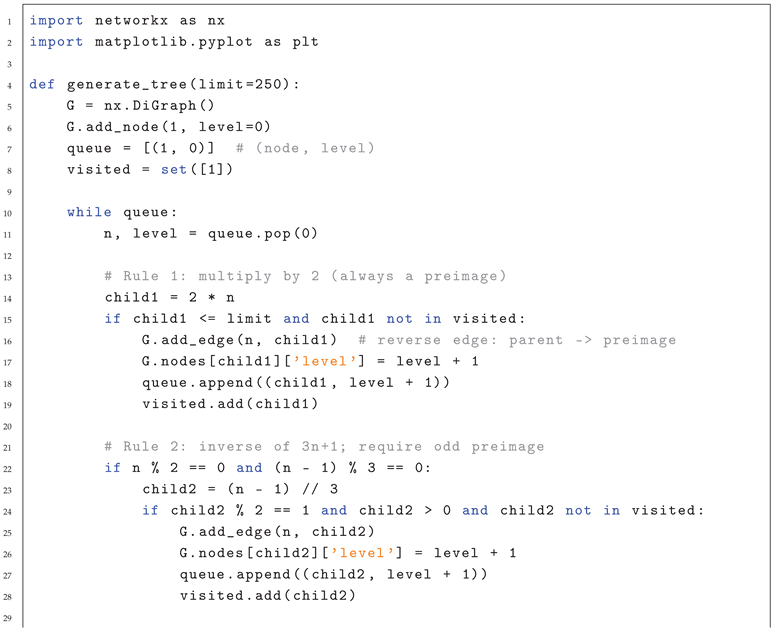

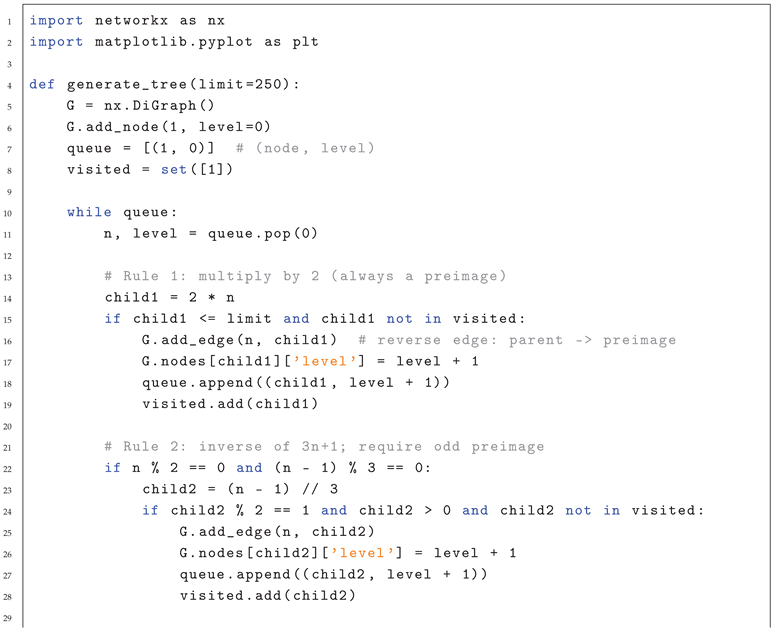

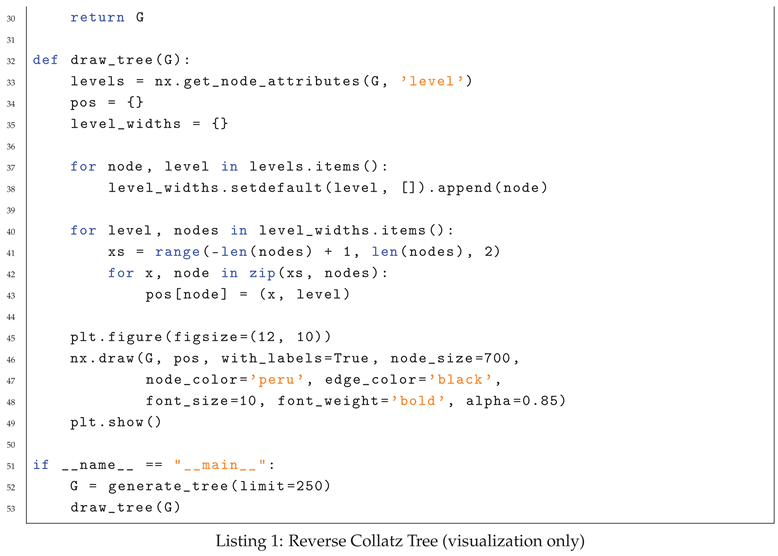

Appendix A. Python Code for Reverse Collatz Tree Visualization

This script visualizes structure up to a finite cutoff and isnota proof of coverage.

The following script

visualizes the reverse graph from 1 up to a finite cutoff

limit.

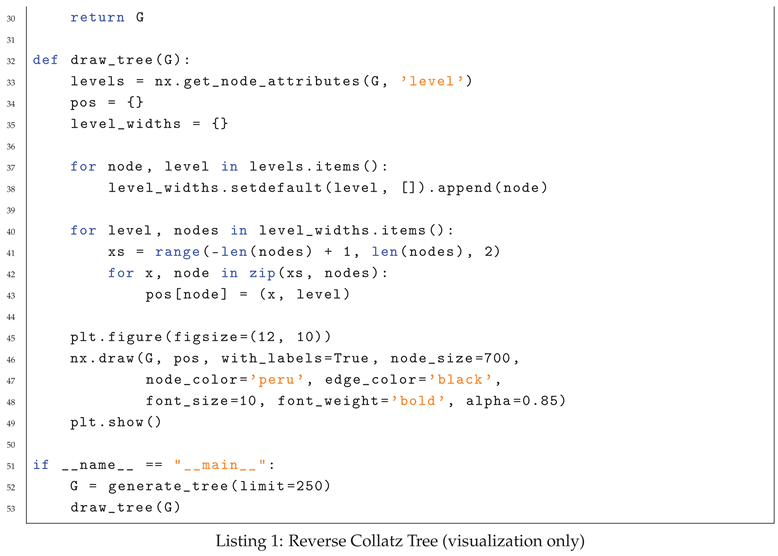

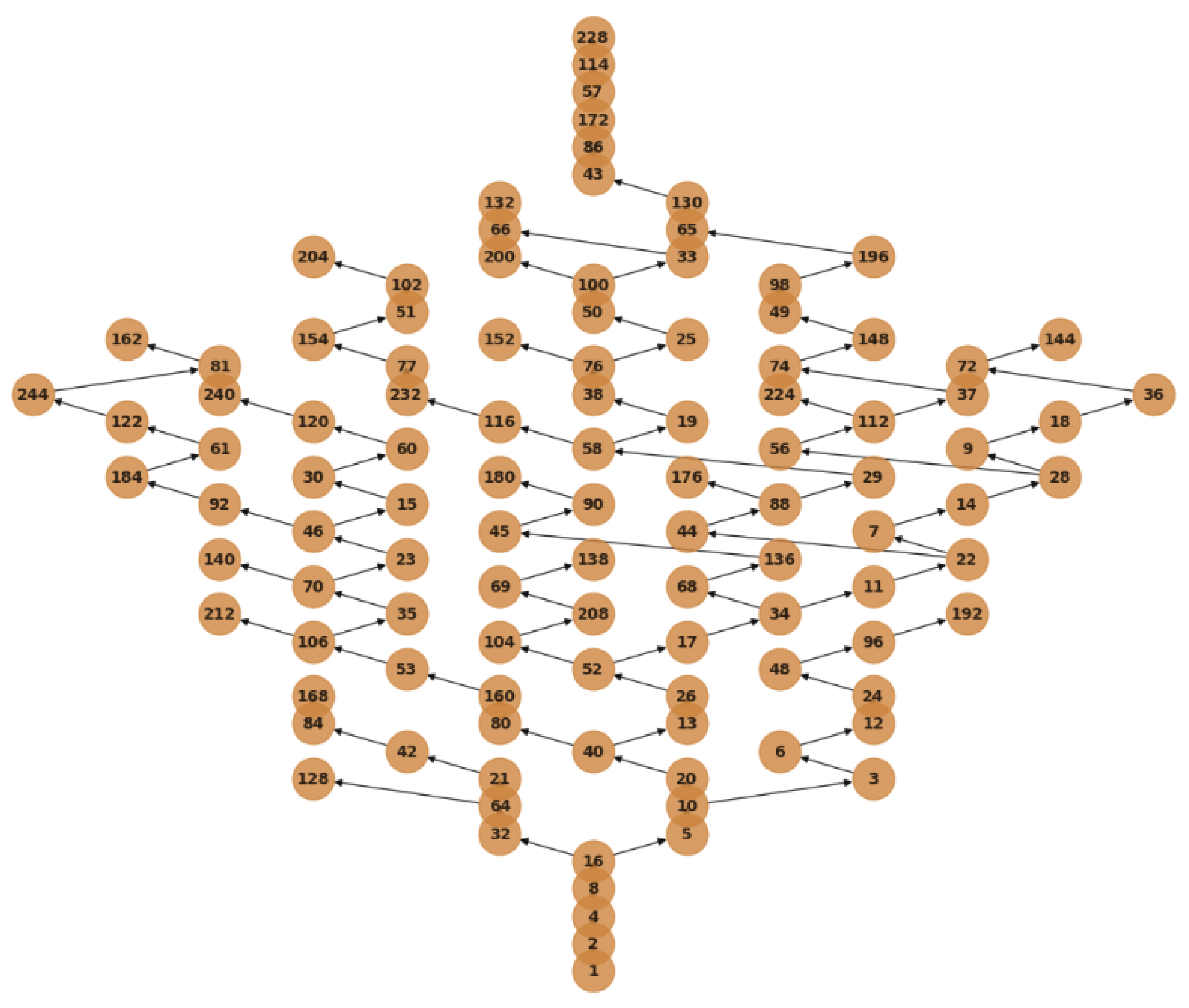

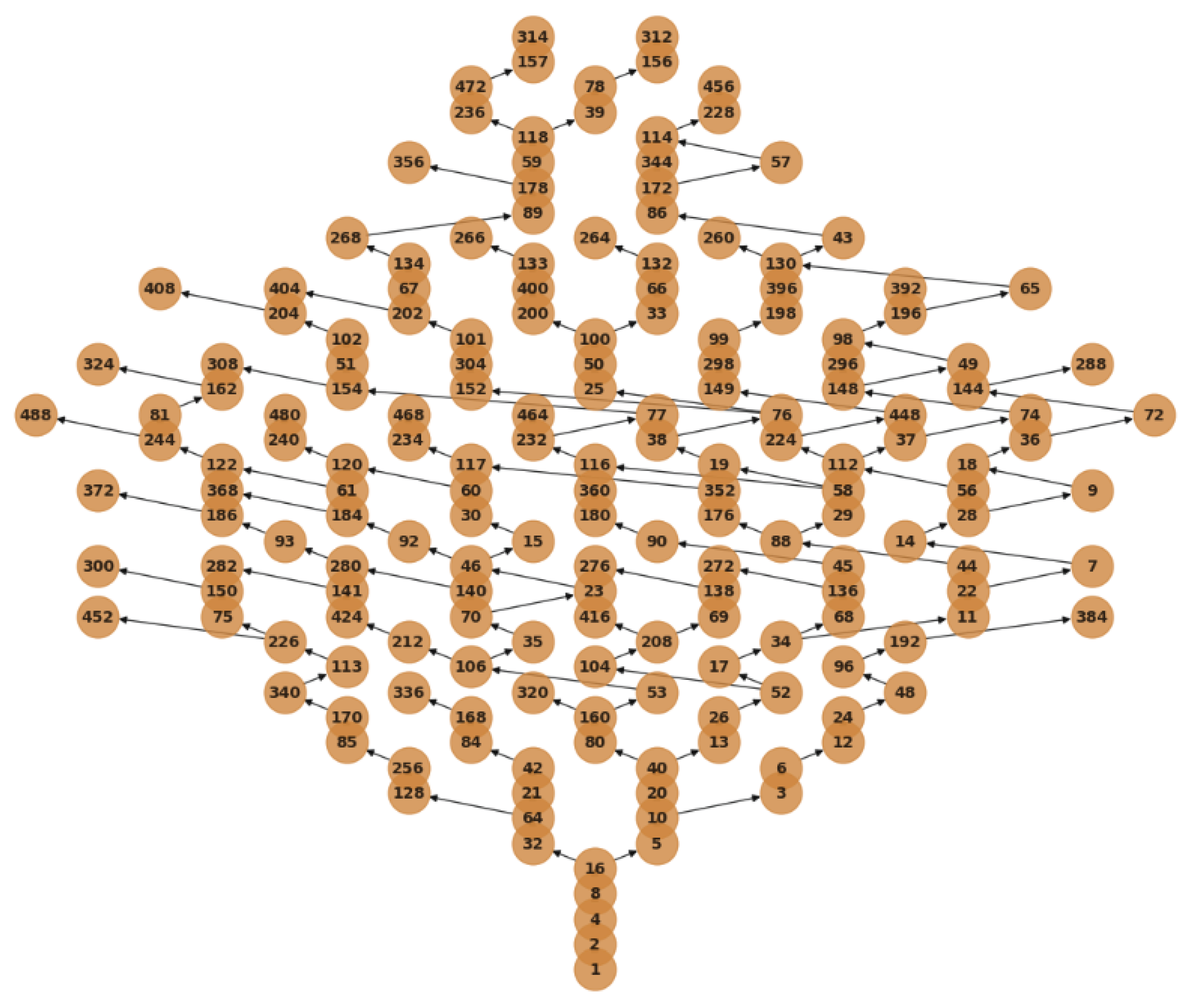

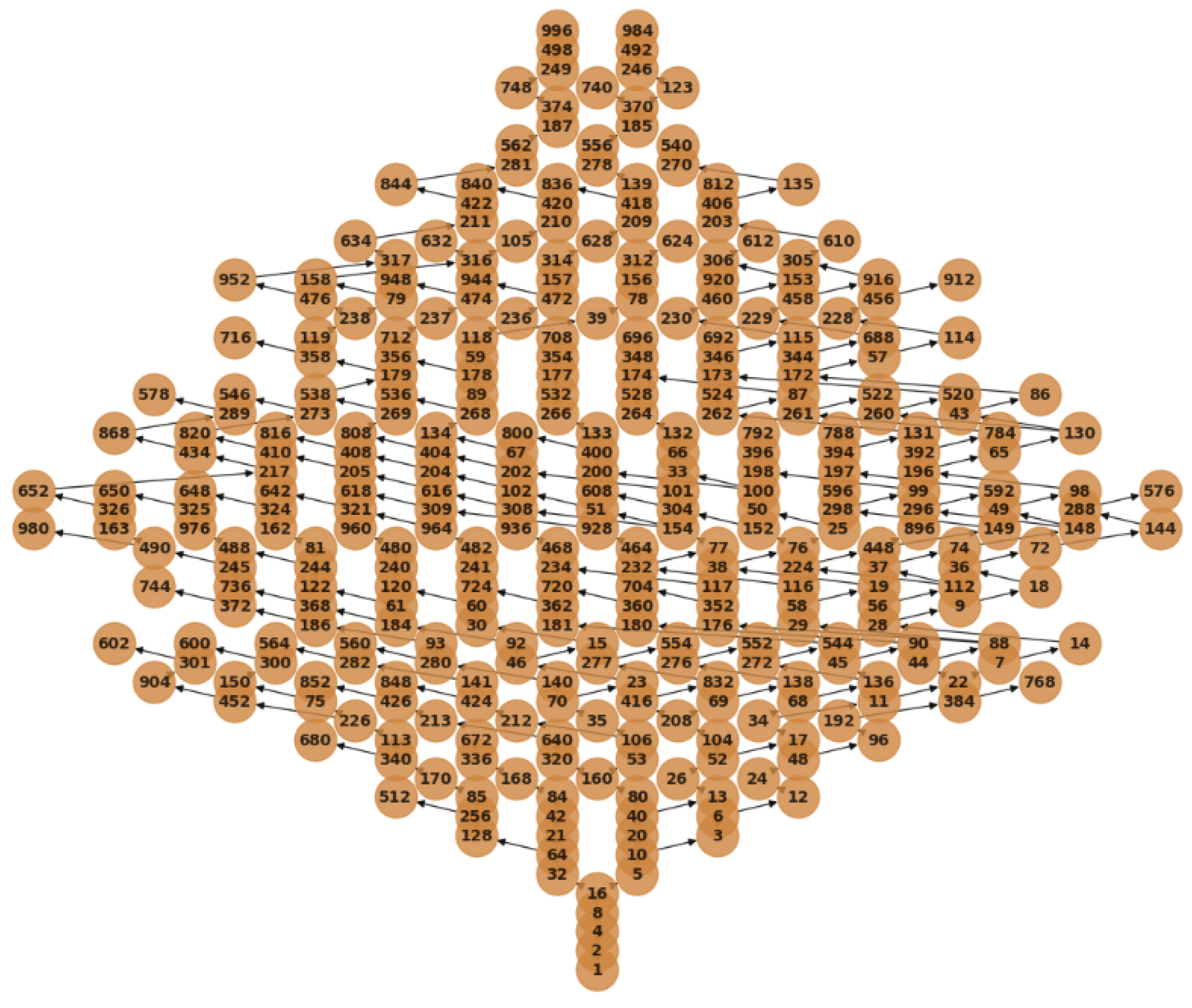

Appendix B. Python-Generated Tree Visualizations (Illustrative Only)

Note. These are finite-cutoff visualizations generated programmatically. They aid intuition but are not proofs of coverage.

Figure A5.

Indexed reverse tree (schematic; edges point to preimages).

Figure A5.

Indexed reverse tree (schematic; edges point to preimages).

Figure A6.

Indexed reverse tree (schematic; edges point to preimages).

Figure A6.

Indexed reverse tree (schematic; edges point to preimages).

Figure A7.

Indexed reverse tree (schematic; edges point to preimages).

Figure A7.

Indexed reverse tree (schematic; edges point to preimages).

Data Availability Statement

Figures can be regenerated using the Python in the Appendix (for visualization; not a proof of coverage).

References

- Lagarias, J.C. The 3x+1 Problem and Its Generalizations. The American Mathematical Monthly 1985, 92, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terras, R. A stopping time problem on the positive integers. Acta Arithmetica 1976, 30, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia contributors, Collatz conjecture, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collatz_conjecture, accessed 2025-03-26.

- Petro Kosobutskyy, The Collatz problem (a·q±1,a=1,3,5,…) from the point of view of transformations of Jacobsthal numbers, arXiv preprint. arXiv:2306.14635, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).