1. Introduction

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) has emerged as a critical tool for non-invasive assessment of myocardial tissue properties. Among the advanced techniques, T1 mapping has shown promise in evaluating both focal and diffuse myocardial fibrosis, diagnosing heart failure and cardiomyopathies, and aiding in risk stratification [

1]. Unlike traditional late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) methods, native T1 mapping and extracellular volume (ECV) mapping can detect pathological changes, including diffuse alterations that are often invisible to T1-weighted imaging, and offer a biomarker for clinical decision-making [

2]. Native T1 mapping, in particular, provides a reliable assessment of myocardial damage, e.g. edema, fibrosis, amyloid deposition, lipid or iron overload, without requiring gadolinium contrast, making it a highly reproducible tool for evaluating conditions such as cardiomyopathies [

3]. Despite its utility, T1 mapping's accuracy is susceptible to various factors, including noise, which can compromise image quality and diagnostic reliability. Not only the mean T1 value but also the histogram analysis of the distribution of T1 value may be useful in assessing the status and progression of the myocardial diseases [

4]; and therefore, the noise reduction for T1 mapping can be important for the accurate and comprehensive evaluation of T1 mapping. Recent advancements in deep learning reconstruction (DLR) have demonstrated the potential to reduce noise and enhance image quality in CMR applications such as late gadolinium enhancement [

5,

6] and cardiac MR angiography [

7], highlighting the opportunity to integrate deep learning-based approaches into T1 mapping for improved diagnostic utility.

The use of DLR technology has begun to be utilized as a method to enhance the image quality of cardiac MRI by improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) [

7,

8]. In recent years, significant progress has been observed in traditional DLR technology, and a novel method known as super-resolution deep learning-based reconstruction (SR-DLR) has emerged. This technique, which combines denoising and high-resolution features, is gaining prominence in the field. Previous studies have demonstrated that SR-DLR significantly improves SNR and CNR in applications such as diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and intracranial MR angiography, while maintaining quantitative accuracy [

9]. Despite these advancements, the application of SR-DLR to myocardial T1 mapping has not yet been investigated.

The purpose of this research is to evaluate the impact of SR-DLR on its ability to reduce noise of T1 mapping in CMR.

2. Materials and Methods

This study comprising patient and phantom study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yokohama City University Hospital (approval number F240700005). Written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective observational study design.

Patient Study Population

In this single-center observational study, we analyzed patients with known or suspected ICM or NICM who had a clinical indication for CMR at Yokohama City University Hospital (Yokohama) between July and December 2023. The study included 36 consecutive patients who underwent CMR as part of their clinical care. The exclusion criteria were severe renal impairment (eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73m2), claustrophobia, and patients with poor image quality for analysis.

CMR Patient Protocol

All MRI images were acquired using a 1.5-T MRI scanner (Vantage Orian, Canon Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) and 32-channel radio frequency (RF) coils (Atlas SPEEDER Body and Atlas SPEEDER Spine). Cine MRI, LGE MRI, and pre- and post-contrast T1 mapping images were obtained from all subjects. Vertical long-axis, horizontal long-axis, and short-axis cine images of the LV were acquired using a steady-state free precession sequence. A total of 0.10 mmol/kg of gadolinium contrast was injected into each patient. Approximately 10–15 min after gadolinium injection, LGE-MRI images were acquired in the same planes as the cine images using an inversion recovery-prepared gradient-echo sequence. Pre-contrast and post-contrast T1 mapping images of the LV myocardium were acquired in short-axis planes at the midventricular level using a modified look-locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) sequence (MOLLI 5 s[3 s]3 s ; repetition time: 4.2 ms ; echo time: 1.6 ms ; flip angle 13° ; field of view 400 × 400 mm ; acquisition matrix 110 × 192).The T1 mappings underwent reconstruction both without and with SR-DLR (PIQE, Canon Medical Systems), utilizing identical scanning data. The PIQE technique has been developed [

9], in which low-SNR, low- resolution images are reconstructed to achieve a high-SNR, high-resolution imaging using deep learning denoising and up-sampling. The parameters for reconstruction without SR-DLR were as follows: matrix 384 × 384, slice thickness 10 mm, reconstructed voxel size 1.04 × 1.04 × 10 mm; and with SR-DLR were as follows: matrix 576 × 576, slice thickness 10 mm, reconstructed voxel size 0.69 × 0.69 × 10 mm.

Phantom Configuration and Scan Protocol

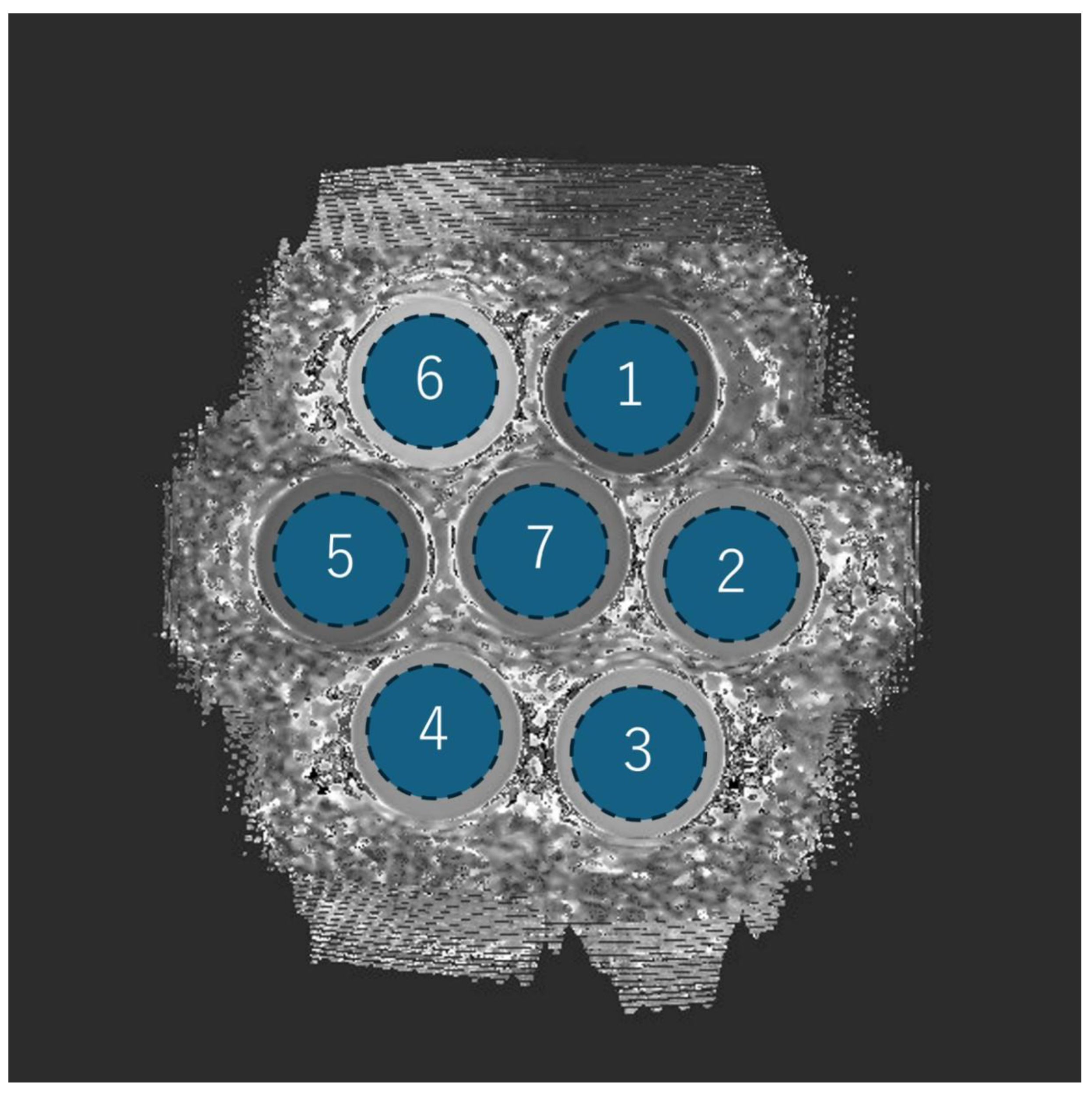

Seven homemade phantoms were made by mixing Gd-DOTA and water and sealing them in polypropylene cylinder-shaped containers (diameter, 6 cm; height, 8 cm), so that the internal solution was at different dilution ratios (

Figure 1). Coronal section imaging produced seven phantom images at a time; two types of T1 mapping images underwent reconstruction both without and with SR-DLR. Thirty imaging sessions were performed. Static phantom scans were performed on the same 1.5T MRI system (Vantage Orian, Canon Medical Systems) equipped with an 8-channel forward array coil with these seven cylinders side by side. Data were collected using the MOLLI method, with an inversion preparation time of 110 ms, emulated heart rate at 60 bpm, and otherwise identical parameters as in the patient study (MOLLI 5 s[3 s]3 s ; repetition time: 4.2 ms ; echo time: 1.6 ms ; flip angle 13° ; field of view 400 × 400 mm ; acquisition matrix 110 × 192). As in the patient study, the parameters for reconstruction without SR-DLR were as follows: matrix 384 × 384, slice thickness 10 mm, reconstructed voxel size 1.04 × 1.04 × 10 mm; and with SR-DLR were as follows: matrix 576 × 576, slice thickness 10 mm, reconstructed voxel size 0.69 × 0.69 × 10 mm.

Quantitative Image Evaluation Methods

In the patient study, to evaluate the image noise before and after the adaptation of SR-DLR, a board-certified radiologist with 10 years of experience (S.S.) placed the regions of interest (ROIs) on T1 mapping in a midcavity short-axis on a medical professional imaging viewer (Ziostation2, version 2.9.7.1; Ziosoft, Tokyo, Japan) and obtained the mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV, SD divided by mean) of T1 value before and after the adaptation of SR-DLR. The sizes of the ROI were 100 mm².

In the phantom experiment, each of the seven phantoms was assigned a number, and the mean, SD (i.e, image noise), and the CV of the T1 values were measured by acquiring ROIs (1957.6 mm²) placed in a circle inside the phantom (

Figure 2).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software SPSS 28.0.1 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All continuous data were tested for normality before analysis using the Shapiro-Wilk test and were expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range (IQR)), as appropriate. The mean values of pre-contrast (native T1 value) and post-contrast mean T1 value and SD before and after the adaptation of SR-DLR were compared using the t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. For the quantitative evaluation, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of mean native T1value and mean post-contrast T1 value after the adaptation of SR-DLR by the two radiologists (S.S. and S.K.) were obtained. ICCs were used to evaluate the agreement between observers and were interpreted as follows: < 0.2 = poor, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = good, and 0.81–1.00 = excellent.

3. Results

Patient Study

The study included 36 consecutive patients referred for CMR at Yokohama City University Hospital between July 2023 and December 2023. The cohort consisted of 19 males and 17 females, with a mean age of 61 ± 17 years (range, 19–81 years). The most common clinical indications for CMR were investigation of the cause of heart failure and suspected ischemic cardiomyopathy. Detailed characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

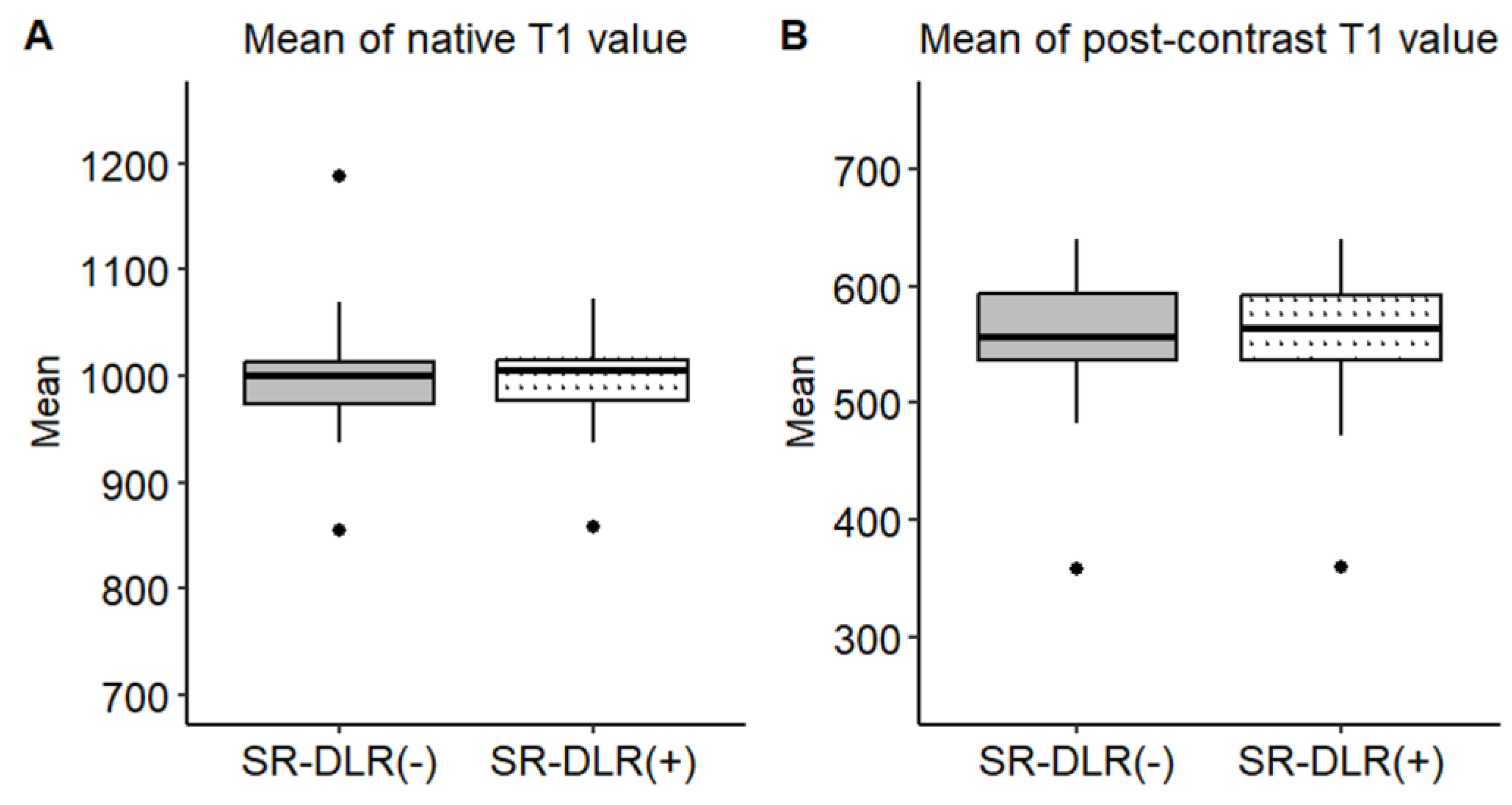

In the patient study, the ICCs for mean native T1 values after the adaptation of SR-DLR were 0.822 (95% CI: 0.605–0.925), while post-contrast mean T1 values had an ICC of 0.955 (95% CI: 0.891–0.982). Both were interpreted as excellent, demonstrating high agreement between observers. For mean native T1 values, the median (IQR) was 1000.2 ms (974.3–1013.6) with SR-DLR and 1004.5 ms (977.2–1015.8) without SR-DLR (p=1.0), showing no statistically significant difference. Post-contrast mean T1 values demonstrated a median (IQR) of 556.4 ms (536.4–592.7) without SR-DLR and 563.8 ms (537.1–591.7) with SR-DLR (p=0.83), also showing no statistically significant difference (

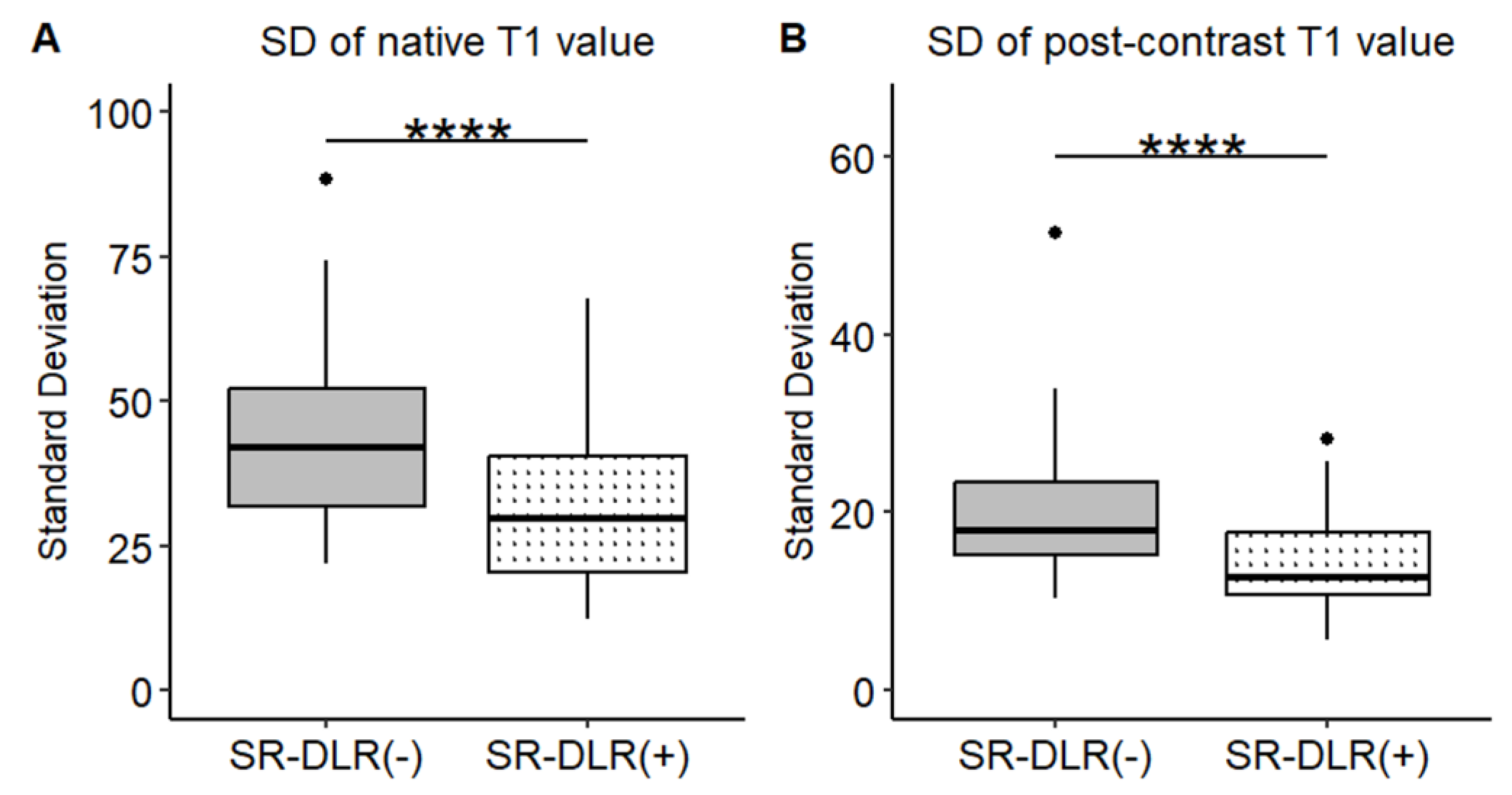

Figure 3). The SD values, however, showed statistically significant differences. For native T1 values, the SD was 42.1 ms (32.0–52.3) without SR-DLR and 29.7 ms (20.4–40.5) with SR-DLR (p=0.001). For post-contrast T1 values, the SD was 17.9 ms (15.3–23.4) without SR-DLR and 12.8 ms (10.8–17.7) with SR-DLR (p<0.001) (

Figure 4). The CV also decreased following SR-DLR application, from 4.4% to 3.3% for native T1 values, and from 3.5% to 2.6% for post-contrast T1 values (

Table 2).

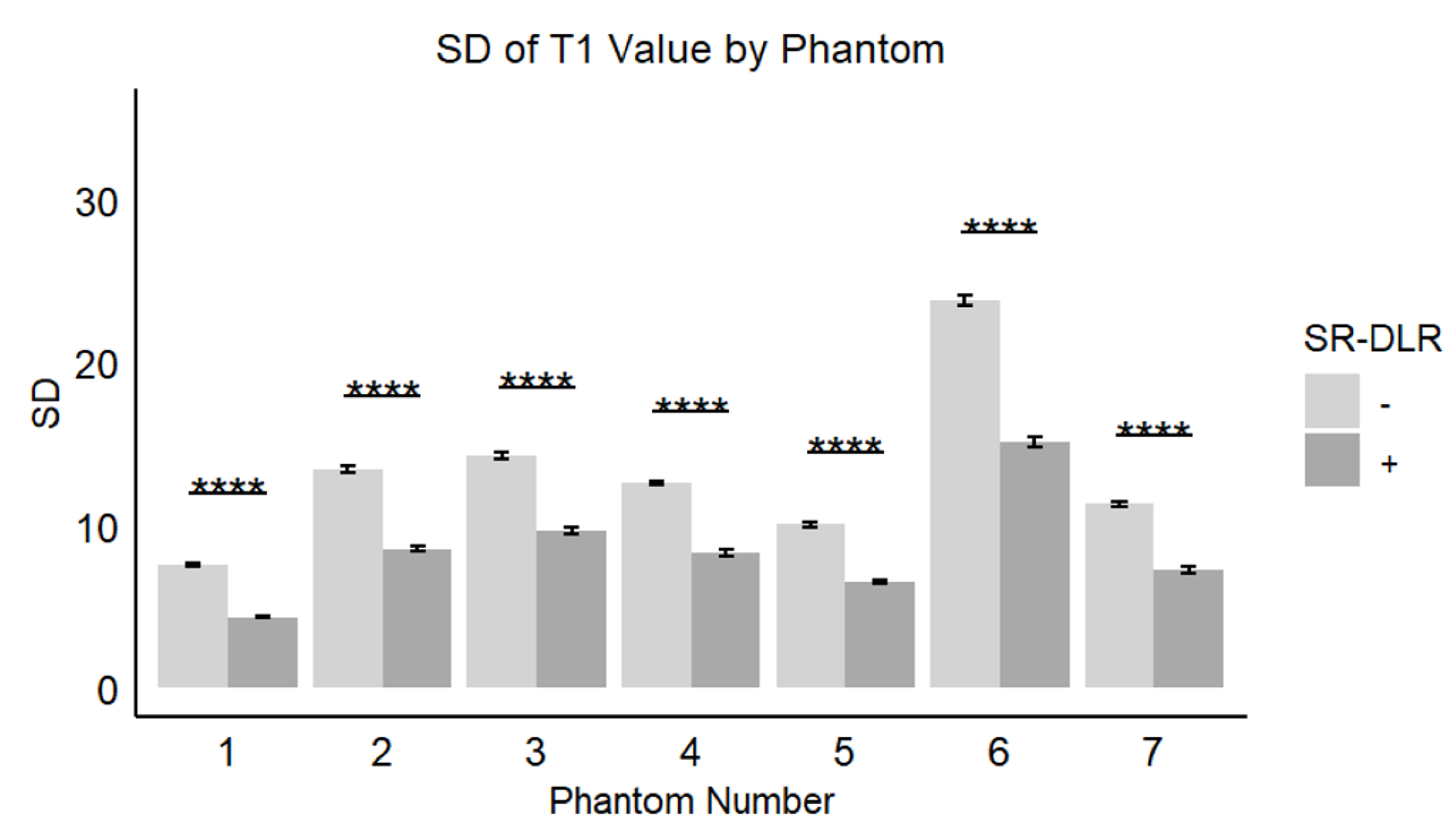

Phantom Study

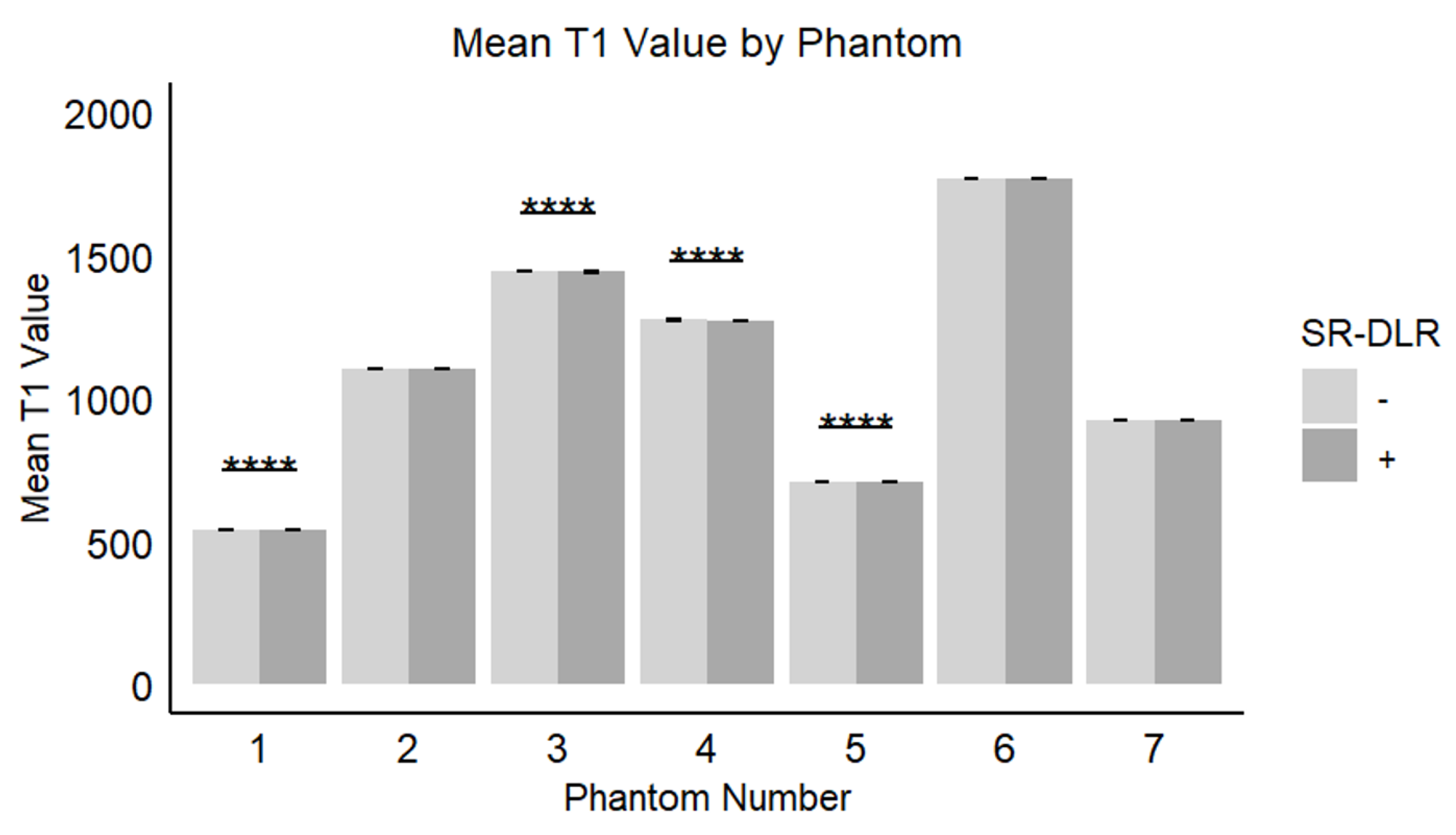

In the phantom study, the mean T1 values, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV) for each phantom with and without SR-DLR are summarized in

Table 3. The results showed that mean T1 values remained nearly identical across all phantoms, regardless of SR-DLR application, indicating that SR-DLR preserved T1 accuracy (

Figure 5). In contrast, SD values were significantly reduced under SR-DLR conditions for all phantoms, suggesting effective noise suppression (

Figure 6). Similarly, CV values were consistently lower with SR-DLR compared to without SR-DLR across all phantoms, further supporting the improvement in measurement consistency.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the effect of SR-DLR on noise reduction and image quality in myocardial T1 mapping. Although SR-DLR did not significantly alter mean native or post-contrast T1 values, it markedly reduced the SD, indicating enhanced image consistency and effective noise suppression. These findings were further supported by the phantom study, in which SR-DLR consistently decreased both SD and coefficient of CV across all phantoms, without affecting mean T1 values. Moreover, the high ICCs observed in patient data demonstrated excellent inter-observer reproducibility with SR-DLR. Taken together, these results suggest that SR-DLR improves the reliability of myocardial T1 mapping by effectively suppressing noise while preserving measurement accuracy.

Reducing variability in T1 measurements offers several clinically important advantages. First, it enhances diagnostic consistency by improving measurement reproducibility across patients and imaging sessions. This is particularly critical for monitoring disease progression and evaluating treatment response in conditions such as myocardial fibrosis—a hallmark of heart failure and other cardiomyopathies [

10]. T1 mapping has been shown to predict clinical outcomes in patients with myocardial fibrosis, where higher levels of fibrosis are associated with worse prognosis [

11]. By reducing measurement variability, SR-DLR may improve the precision of fibrosis quantification, thereby contributing to more accurate risk stratification and prognostication. Furthermore, from a clinical implementation perspective, the establishment of institutional reference values typically requires sex- and age-adjusted ranges derived from at least 50 healthy subjects to detect subtle biological changes (e.g., diffuse myocardial fibrosis). However, this approach is often impractical. Improving reproducibility through SR-DLR could reduce the required sample size, thus facilitating clinical application and validation [

12].

Second, the enhanced reproducibility provided by SR-DLR increases the reliability of T1 mapping as a tool for clinical decision-making. T1 mapping and ECV measurements are increasingly being used to guide therapeutic strategies, such as assessing the efficacy of interventions in cardiac amyloidosis and non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (NIDCM) [

13,

14]. In particular, T1 mapping is highly useful in cardiac amyloidosis, and it is known to have high diagnostic performance because significant interstitial expansion due to amyloid deposition results in a marked elevation of native T1 and ECV [

15]. A diagnostic tree that omits invasive myocardial biopsy has also been proposed, and the use of SR-DLR is expected to further increase its value [

16]. In addition, it has been reported that MRI-ECV is useful for monitoring the effects of drug therapy such as tafamidis [

17,

18]. Otherwise, T1 mapping is known to be very useful in Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD), where it has high diagnostic potential because lipid deposition reduces native T1 [

19,

20]. In addition, it has been reported to be useful in monitoring drug therapies such as enzyme replacement therapy for AFD [

21,

22]. The ability of SR-DLR to produce consistent measurements across imaging sessions may also help refine diagnostic algorithms and optimize treatment plans for a range of cardiovascular diseases. Also, the reduce image noise on T1 mapping by SR-DLR might provide accurate T1 value distribution, leading to an appropriate assessment of pseudo-normalization in AFD [

4].

Furthermore, reduced variability in T1 measurements benefits research by improving the precision of statistical analyses. High variability in data can obscure meaningful trends and reduce the power to detect significant effects. By minimizing this variability, SR-DLR enables clearer interpretation of results and enhances the reproducibility of findings in clinical trials and observational studies. For example, T1 mapping has been used to track changes in fibrosis in response to treatments such as chemotherapy in cardiac amyloidosis and catheter ablation in NIDCM [

14,

23]. The ability to reliably measure small changes in T1 values with SR-DLR could facilitate the discovery of new therapeutic targets and improve the evaluation of treatment efficacy.

Several limitations of this study should also be acknowledged. This study was conducted at a single center with a relatively small sample size, and further validation in larger, multi-center cohorts is necessary to confirm the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, while SR-DLR demonstrated strong performance in reducing noise, its impact on the detection of focal fibrosis and other subtle myocardial changes warrants further investigation.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

The integration of SR-DLR into myocardial T1 mapping workflows offers significant potential to enhance consistency, reliability, and utility of T1 measurements. By addressing key limitations associated with noise and variability, SR-DLR represents an important step forward in advancing the diagnostic and prognostic capabilities of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S Kato; methodology, S Kato; software, T Hirano, T Kato and S Kato; validation, T Hirano, T Kato and S Kato; formal analysis, S Sawamura.; investigation, S Sawamura, N Yasuda, T Iwahashi; resources, T Hirano, T Kato; data curation, S Sawamura and S Kato; writing—original draft preparation, S Sawamura and S Kato; writing—review and editing, S Kato and D Utsunomiya; visualization, S Sawamura, N Yasuda and T Iwahashi; supervision, D Utsunomiya; project administration, S Kato. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University Hospital (approval ID: F240700005, 6 August 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective observational study design, and the study was conducted using an opt-out method by publicly disclosing information about the research.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

D Utsunomiya reports that he has received research grants from Canon Medical Systems paid to the Department of Diagnostic Radiology at Yokohama City University Graduate School of Medicine. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFD |

Anderson-Fabry disease |

| CMR |

cardiac magnetic resonance imaging |

| CNR |

contrast-to-noise ratio |

| CV |

coefficient of variation |

| DCM |

dilated cardiomyopathy |

| DLR |

deep learning-based reconstruction |

| DWI |

diffusion-weighted imaging |

| ECV |

extracellular volume |

| ICC |

Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| IQR |

interquartile range |

| LGE |

late gadolinium enhancement |

| MOLLI |

modified Look-Locker inversion recovery |

| NIDCM |

non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy |

| RF |

radio frequency |

| ROI |

region of interest |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| SNR |

signal-to-noise ratios |

| SR-DLR |

super-resolution deep learning-based reconstruction |

| WHCMRA |

whole-heart coronary magnetic resonance angiography |

References

- Haaf P, Garg P, Messroghli DR, Broadbent DA, Greenwood JP, Plein S. Cardiac T1 Mapping and Extracellular Volume (ECV) in clinical practice: a comprehensive review. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016, 18, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron D, Vassiliou VS, Higgins DM, Gatehouse PD. Towards accurate and precise T (1) and extracellular volume mapping in the myocardium: a guide to current pitfalls and their solutions. MAGMA. 2018, 31, 143–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamori S, Dohi K, Ishida M, et al. Native T1 Mapping and Extracellular Volume Mapping for the Assessment of Diffuse Myocardial Fibrosis in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018, 11, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda S, Kidoh M, Morita K, Takashio S, Tsujita K. Histogram features of Fabry disease with pseudonormalization in native T1 mapping. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021, 22, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Wang F, Wang Z, Zhang W, Xie L, Wang L. Evaluation of late gadolinium enhancement cardiac MRI using deep learning reconstruction. Acta Radiol. 2023, 64, 2714–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Liu WV, Yan Y, et al. Evaluation of deep learning-based reconstruction late gadolinium enhancement images for identifying patients with clinically unrecognized myocardial infarction. BMC Med Imaging. 2024, 24, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Kariyasu T, Machida H, Takahashi S, Fukushima K, Yoshioka T, Yokoyama K. Denoising using deep-learning-based reconstruction for whole-heart coronary MRA with sub-millimeter isotropic resolution at 3 T: a volunteer study. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2022, 28, 470–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velde N, Hassing HC, Bakker BJ, et al. Improvement of late gadolinium enhancement image quality using a deep learning-based reconstruction algorithm and its influence on myocardial scar quantification. Eur Radiol. 2021, 31, 3846–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo K, Nakaura T, Morita K, et al. Feasibility study of super-resolution deep learning-based reconstruction using k-space data in brain diffusion-weighted images. Neuroradiology. 2023, 65, 1619–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer RA, De Keulenaer G, Bauersachs J, et al. Towards better definition, quantification and treatment of fibrosis in heart failure. A scientific roadmap by the Committee of Translational Research of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2019, 21, 272–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piek A, De Boer RA, Silljé HHW. The fibrosis-cell death axis in heart failure. Heart Failure Reviews. 2016, 21, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messroghli DR, Moon JC, Ferreira VM, et al. Clinical recommendations for cardiovascular magnetic resonance mapping of T1, T2, T2* and extracellular volume: A consensus statement by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) endorsed by the European Association for Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI). J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017, 19, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Naharro A, Patel R, Kotecha T, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in light-chain amyloidosis to guide treatment. European Heart Journal. 2022, 43, 4722–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma M, Kato S, Sekii R, et al. Extracellular volume fraction by T1 mapping predicts improvement of left ventricular ejection fraction after catheter ablation in patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation. The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2021, 37, 2535–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan JA, Kerwin MJ, Salerno M. Native T1 Mapping, Extracellular Volume Mapping, and Late Gadolinium Enhancement in Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020, 13, 1299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2023, 44, 3503–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, et al. Tafamidis Treatment for Patients with Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 1007–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato S, Azuma M, Horita N, Utsunomiya D. Monitoring the Efficacy of Tafamidis in ATTR Cardiac Amyloidosis by MRI-ECV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tomography. 2024, 10, 1303–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsiglione A, Gambardella M, Green R, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance native T1 mapping in Anderson-Fabry disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2022, 24, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsiglione A, De Giorgi M, Ascione R, et al. Advanced CMR Techniques in Anderson-Fabry Disease: State of the Art. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023; 13(15).

- Nordin S, Kozor R, Vijapurapu R, et al. Myocardial Storage, Inflammation, and Cardiac Phenotype in Fabry Disease After One Year of Enzyme Replacement Therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019, 12, e009430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averbuch T, White JA, Fine NM. Anderson-Fabry disease cardiomyopathy: an update on epidemiology, diagnostic approach, management and monitoring strategies. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023, 10, 1152568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou A, Patel RK, Martinez-Naharro A, et al. Tracking Treatment Response in Cardiac Light-Chain Amyloidosis With Native T1 Mapping. JAMA Cardiology. 2023, 8, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).